A Study of Analog Devices Organizational Approach for Project Management

Info: 11228 words (45 pages) Dissertation

Published: 10th Dec 2019

Management Consultancy Report Project

A study of Analog Devices organizational approach and structure with regard to project management.

Contents

Section I: Industry & Organisational Drivers of Project Management

PMBOK Knowledge Areas an Analog Perspective

Section II: Alignment with Strategy

Project/Programme alignment with Strategy

Portfolio Selection Recommendations

Section III – Project Lifecycle

Explaining the Analog Project Life cycle and Recommendations

Section IV: Organisational Structure

Suggested Appropriate Structure

Section V: Project and Organisational Maturity

Section VI: People and Competency Development

Assignment of Project/Programme Managers

Section VII: Stakeholder Analysis

Stakeholder Management Strategy

Table of Figures

Figure 1: Analog Device International Limerick

Figure 2: Principles of Shingo

Figure 3: MBOK Knowledge Areas

Figure 4: ADI PM Driving Factors October 2017

Figure 5: Cross Site Structure

Figure 6: Sample Project Statistics October 2017

Figure 7: ADI Typical Project lifecycle

Figure 8: PMI Project Life Cycle

Figure 9: Typical Project Organisation Chart

Figure 10: Organisational Structure for Projects

Figure 11: Fully Projectized Structure

Figure 12: Strong Matrix Organizational Structure

Figure 14: P3M3 Self-assessment Answers

Figure 15: Project Management Maturity Levels

Figure 16: P3M3 Maturity Curve

Figure 17: Leadership Profiles for Organisational Change Projects

Figure 18: ADI Learning Development Statement

Figure 19: Project Management eTraining

Figure 21: Senior Management Stakeholder Register

Figure 22: Stakeholder Commitment Map

Introduction

Figure 1: Analog Device International Limerick

Analog Devices (NASDAQ: ADI) is an American multinational semiconductor organisation. They are a world leader in the design, manufacture and marketing of a broad portfolio of high performance analog, mixed-signal, and digital signal processing (DSP) integrated circuits (ICs) used in virtually all types of electronic equipment. Market leaders in all areas of the electronic spectrum including Healthcare, Automotive, Consumer and industrial they were originally founded in Massachusetts in 1965 and currently employ over 15,000 employees worldwide. The company established an initial manufacturing presence in Limerick in 1977 and currently employs over 1200 people at both its Limerick and Cork facilities. Project implementation would be common throughout the organization with the following operations currently performed at the Limerick site:

- Research & Development

- Sales & Marketing

- Distribution

- Manufacturing

- Treasury

Section I: Industry & Organisational Drivers of Project Management

This section of the report looks at Organisational Project drivers predominantly at the Limerick site and more specifically within the manufacturing department, As with any large scale organisation there are always a multitude of projects at the various stages of implementation at any one time. The scope of these projects would range from Multi-Million dollar infrastructure upgrades to routine day-day continuous improvement projects. A project proposal could be made from any employee within the organisation and this is encouraged through the various CI (Continuous Improvement) councils that feature representatives from across the assorted functional groups.

The one specific area that is having a major effect in terms of project drivers currently is the company’s decision in 2016 to align itself to the Shingo Model™ of Enterprise Excellence across all sites worldwide. The mission of The Shingo Prize for Operational Excellence is to create excellence in organizations through the application of universally accepted principles of operational excellence, alignment of management systems and the wise application of improvement techniques across the entire organizational enterprise. This is supported by teaching correct principles and new paradigms that accelerate the flow of value, align and empower people and transform organizational culture. (Shingo Institute, 2013) . Figure 2 below shows the 4 core principles of Shingo and where they sit within the pyramid structure.

Figure 2: Principles of Shingo

PMBOK Knowledge Areas an Analog Perspective

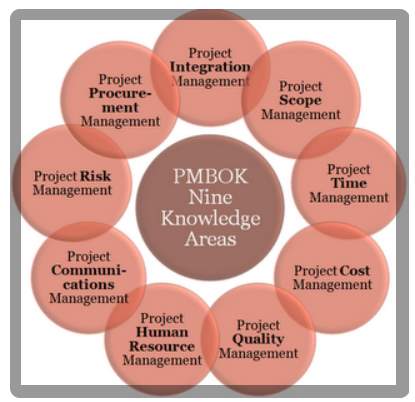

The current PMBOK Guide lists 10 knowledge areas that define the project management discipline. However this report is based on the 4th Edition which lists nine and these are shown in figure 3 (Project Management Institute, 2008).

Figure 3: MBOK Knowledge Areas (solutionsiq, 2017)

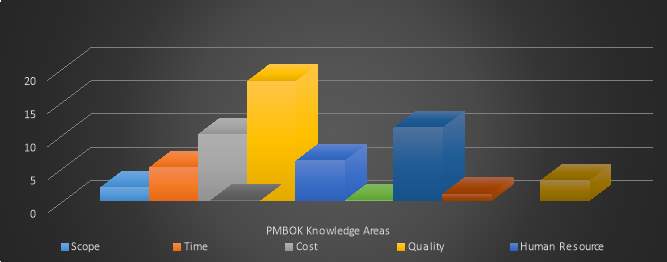

To try and understand the Analog driving factors for projects through the lens of the 9 PMBOK, 55 employees involved in the project management discipline were requested to participate in a survey asking what they consider to be the primary driving factor affecting their management of projects currently and these results are summarised in figure 4.

Figure 4: ADI PM Driving Factors October 2017

The above data shows that the major influencers within the manufacturing organisation are Quality, Risk and Cost. These three account for over 70% of overall manager responses. Analysing the remaining factors gives a complete priority list of:

- Quality

- Risk

- Cost

- Human Resource Management

- Scope

- Communications

- Time

- Integration

- Procurement

- Other than listed

Quality was not unexpected as the major influencing factor affecting the management of projects and this result would have been expected prior to commencing. It was surprising to find quality so low down in terms of relative importance versus the other knowledge areas in a number of research papers including Ofer Zwikael’s paper (Zwikael, 2009)but as an industry that is heavily regulated both internally by a dedicated QA department and externally by customers this aspect would be the predominant driving force behind any project that is decided upon within the organisation.

The Second Identified knowledge area was risk, in an international manufacturing facility risk typically would have a multitude of facets to it. Financial, Reputational, Quality, effect on manufacturing output. Chapter 11 of the PMBOK guide discusses these risks in detail(Project Management Institute, 2013)but it is always one of the key considerations behind projects within the organisation because the damage can be very hard to repair. Particularly with projects related to the core manufacturing environment risk is a major concern.

The final of the main three driving factors is cost. Typically at any one time there will only be a limited amount of both financial and personal resources available and a large part of any decision to authorise a project is the draw on these. Except in exceptional circumstances this will always be a major consideration. Not only the initial cost but also the potential for overrun.

In summary as would be expected most of the knowledge factors have an influence on Project policy within the organisation but to varying degrees. The results above pertain predominantly to manufacturing where Quality/Risk & Cost are the major influencing factors and this is as would have been expected due to the nature of the environment. The product manufactured is high cost and high value and the market for this is very competitive so reputation and performance is critical. HR management is a growing influencing factor due to corporate policy of inclusion and also the influence of Shingo alignment. One final thing to note was that there was a wide variation in influencing factors depending on which department was managing the project, For example the IS department placed a greater emphasis on Scope & Communication while the Facilities manager placed importance on Procurement & Cost.

The 9 knowledge areas form part of the Project Management Institute Body of Knowledge (PMBOK) that while far from perfect do offer a number of benefits including:

- Attempts to put a best practice structure around project management.

- The formation of some form of minimum standards and principles.

- A global framework which will allow for easier integration of teams from different countries/backgrounds.

There are however limitations to the PMBOK and some scholars including(Crawford and Pollack 2007) have researched whether projects by their nature are fundamentally unique and not suitable for standardization. (Morris et al. 2006) further argue that there is a lack of balance between academic research and the PMBOKs which have been primarily driven by the organization and practitioners themselves who have a vested interest in the discipline. Other limitations in the PMBOK include (Songer, 2016):

- Outputs for processes described but little guidance on contents provided.

- No guidance on Project Management team responsibilities.

- No guidance on tailoring – how exactly to proceed and step by step approach.

- Not enough details on the contents of plan and how they should be developed at varying levels of details by whom.

Section II: Alignment with Strategy

Project/Programme alignment with Strategy

As discussed in section 1 worldwide corporate strategy has been aligned to the Shingo model from a top overview level. How this vision is interpreted varies depending on the affected department but it is a framework within which the entire organisation is aligned. Current corporate manufacturing strategy is focused primarily on 3 areas:

- Better productivity and returns for shareholders and customers.

- Improvements and efficiency from recent corporate acquisitions and internal mergers.

- Support research and development for next generation projects “Create the future”.

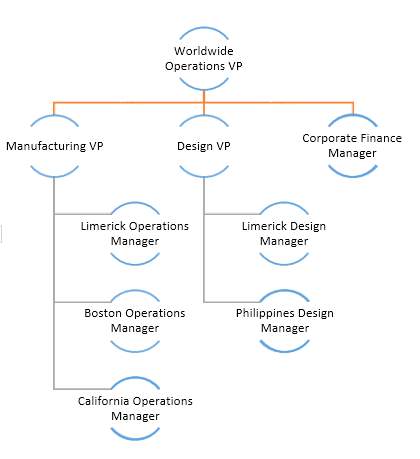

With regard to strategy alignment all manufacturing sites worldwide are now closer aligned resulting in a greater visibility across all areas. Analog have begun a program of consolidation at VP operational level over the previous 12 months and it is this responsibility over multiple sites that has had the greatest influence in aligning the entire projects portfolio to strategy. All areas of the organisations are being controlled by a smaller pool of people thus reducing the regional variances in programmes/portfolios that would have previously existed. A typical example of this restructuring is shown below.

Figure 5: Cross Site Structure

Portfolio selection processes

Typical of any organization on this scale at any one time there would be many multiples of projects and programmes in various stages of completion. A brief investigation on the week this report was being researched (October 2017) showed over 220 individual projects in operation and this was just a limited sample of a particular management group of 15 individuals. (Figure 6). A critical task within the organisation is to manage the daily operations plus support these ongoing project teams which form part of various programmes and ultimately portfolios.

| Area | Projects in Operation |

| Research & Development | 46 |

| Continuous Improvement | 38 |

| Manufacturing | 31 |

| Engineering | 24 |

| Financial | 18 |

| Customer Related | 17 |

| Information Technology | 11 |

| Other | 35 |

Figure 6: Sample Project Statistics October 2017

Major programmes and portfolios due to the scale and finance involved form part of the overall corporate operations plan. This would be part of an integrated framework strategic in nature driven and controlled from a very high level involving consideration for corporate direction, customer and shareholder expectations. The overall portfolio selection process in place is based on industry best practice similar to a number of techniques including the PMI Standard for Portfolio Management which contains nine portfolio management processes (Ross & Shaltry 2006)

- Identification

- Categorization

- Evaluation

- Selection

- Prioritization

- Portfolio Balancing

- Authorization

- Portfolio Reporting and Review

- Strategic Change

Minor projects however typically do not form part of the overall portfolio management process. These are usually locally driven by the Functional manager without any structured form of overall management either programme or portfolio. There is often no co-ordination between projects and the same resources are being asked to support multiple assignments with choices being decided by perceived priority. There are also further tendencies to abandon or deprioritise projects and programmes in preference of the current “flavour of the month”.

Portfolio Selection Recommendations

So why do Analog need a project portfolio? (Archer et al 1999) define project portfolios as “a group of projects that are carried out under the sponsorship and/or management of a particular organization” It further elaborates that “These projects must compete for scarce resources available from the sponsor since there are usually not enough resources available to carry out every proposed project”. (Martinsuo & Lechtonen 2007) consider a project portfolio as “A group of projects that share and compete for the same resources and are carried out under the sponsorship of an organization. The common points mentioned here are the emphasis on managing resources. The organization has limited resources in terms of financing and staffing therefore excessive duplication and a lack of coherent direction causes issues across the entire project spectrum.

High level large scale projects are well embedded within the overall business portfolio however this does not extend throughout the entire organisation encompassing all areas and that is the recommendation this report would make. The main issues are with functional departmental projects which are typically reliant on a limited pool of common resources including administration and technical staff. There are a number of potential solutions to this. A defined Portfolio selection model such as the (Caballero et. al 2012) who examines the different methodologies used in project selection emphasizing mathematical programming and optimization techniques and suggests the development of a decision support system to reduce the mathematical programming for the end user. Alternatively (Blichfeldt and Eskerod 2008) in their paper offer an Integrated Framework for project portfolio selection which separates the selection processes into distinct stages. These are just two of many potential portfolio selection models. Backed by research including (Blichfeldt and Eskerod 2008) who argue that PPM (Project Portfolio Management) needs to encompass all projects it can be seen that Analog should develop a structured portfolio selection model which encompasses all areas and levels of the organization.

Section III – Project Lifecycle

Section III – Project Lifecycle

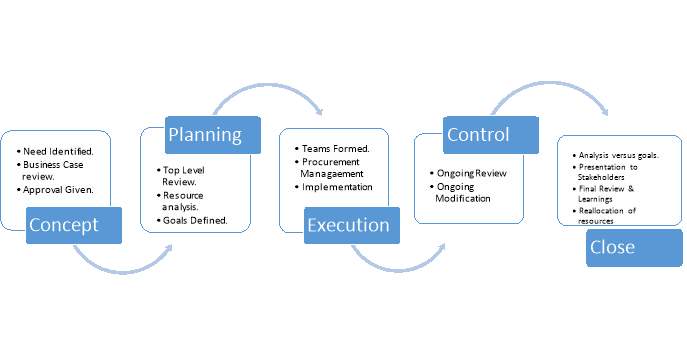

Figure 7: ADI Typical Project lifecycle

Project lifecycle within the organisation would follow a common pattern of 5 phases each containing a number of individual steps. Phase 1 is the project concept. Typically a project is proposed for one of three reasons.

- To rectify or enhance a current deficiency.

- To add additional capacity.

- To align to current business models.

The project proposer makes a recommendation and this would be reviewed first by the relevant department manager who would then make a business case review. The analysis would take in a number of factors including Cost/Risk/Potential benefits, Resources required etc. Once approval is given the project would then move to stage 2 which is the planning phase.

The planning phase takes place in the form of a number of meetings to lay out the project metrics and expectations. Initially a top level team of the affected area managers would assemble to review the scope of the project, this would typically be led by the department manager or vice president of operations who is requesting the project. At this phase a project manager/supervisor would be assigned and potential resource requirements considered. The initial project analysis would be undertaken and the various expected outcomes defined along with potential costs identified and the predicted timelines.

Phase 3 is the execution phase. This is where the project team begins its initial workings, Additional resources are added if required along with the procurement step of establishing relationships with all external contractors and suppliers that are involved. Phases 3 & 4 are inter-related. During execution there would be regular Weekly/Bi-Weekly meetings to control the direction and progress of the project. The control phase also involves the removal of any barriers or impediments. Regular communication and consultation takes place between all the relevant stakeholders throughout this phase.

Phase 5 project close. As part of the regular control the project would continuously be analysed. Once the team are satisfied that all achievable goals have been met there is a top level review with the manager sponsoring the project. At his point the entire project results are examined (Costs/schedule/goals/resources/outcomes if possible) and if changes are need then the team resumes the execution phase. If the stakeholders are satisfied then the project is deemed closed. A final analysis takes place to discuss all the project learnings. In a lot of cases the project team would be involved in the project in tandem with their core job so they would just resume normal operations. For larger projects where certain people may have been entirely dedicated to the project they are reallocated. This phase is typically brief with employees commonly resuming their functional roles while the project close phase is still in operation.

Explaining the Analog Project Life cycle and Recommendations

The current lifecycle within the organisation is predominantly driven by history and experience. This would not be surprising for a company that is in operation for 50 years with a clearly defined structure network. Comparing the current model to the Project Management Institutes life cycle in figure 8 it can be seen that conceptually they are very similar.

Figure 8: PMI Project Life Cycle (solutionsiq, 2017)

Analysis of Analog shows a life cycle that is tried and tested, there are however both limitations and benefits to this. The main benefit is familiarity where teams can integrate and function in the minimal amount of time thus reducing efficiency losses early in the project. This familiarity however has a disadvantage in that people tend to act conservatively and innovation is not always encouraged. Internal restrictions to project management life cycle include delays in the planning and concept phase. Execution is generally swift as results are demanded but major changes are difficult without delaying the entire project. Control is also one area that is tightly monitored. Costing itself is probably the biggest delay, Budgets are allocated on a quarterly or even annual basis and missing the approvals window for funding will result in a delay of up to 3 months until the next approvals cycle.

In terms of recommendations there are some suggestions this report makes. Firstly one area which could potentially deliver efficiencies is the greater use of Agile innovation methods for certain classifications of projects within the organization. This would be commonly used for software development but there is a growing body of research showing the benefits of applying this to main stream industry (Hass 2007). The Analog approach to project management is a typical structured, comprehensively analysed model. This has benefits as discussed previously but can be very rigid and inflexible resulting in changes during project lifecycle being difficult and slow. Agile however is divided into a series of sprints of shorter span, Because of this agile is more open to changes in the specification and there is less time spent on upfront planning. Since Agile is split into sections each is designed to deliver a small amount of work changes can be made and prioritized easily throughout the lifecycle.

A second recommendation would be a more thorough post project completion analysis. In situations even where there have been learnings these are not always acted upon. Similarly because of the separate structures involved learnings are rarely shared. The solution to this would be similar to the findings in section II where it was recommended that there needs to be a better overall strategy for project implementation encompassing all areas of the organisation rather than the current ad-hoc approach. One way this could be achieved would be through the creation of a project management office. A project management office (PMO) is an organizational entity established to manage a specific project or a related series of projects, usually headed by a project or program manager. Christine Xiaoyi Dai investigates the potential benefits and argues that results and project performance are enhanced by the use of a PMO (Dai 2004). Jerry Julian also found that PMO leaders facilitate cross-project improvement by embedding accumulated knowledge from past project experiences into project management routines that are utilized across multiple projects (Julian 2008).

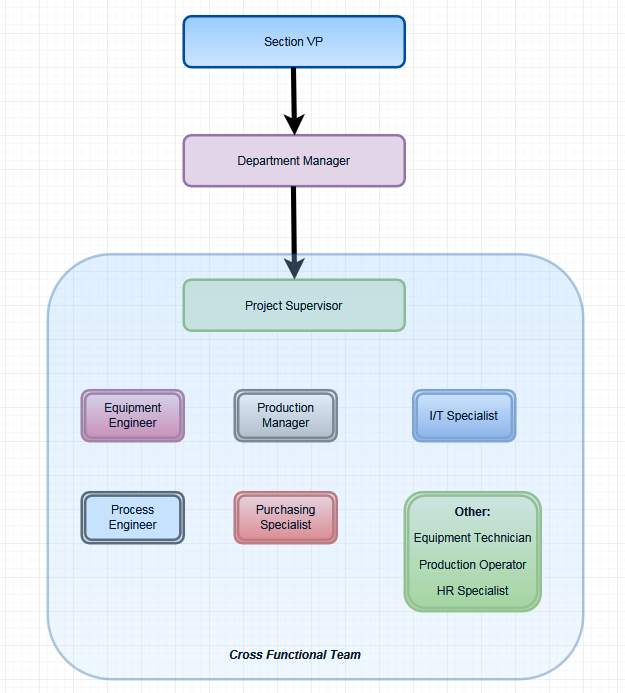

Section IV: Organisational Structure

Analog Devices would have an archetypical management structure similar to a lot of organisations that have originated in the United States. Each core section be it Development/ Manufacturing/ Finance would have a Vice President (VP) in charge of operations. Reporting to them would be the relevant Department Managers. Figure 9 below gives a common supervisory structure for a typical project that would be in operation.

Figure 9: Typical Project Organisation Chart

Project teams would be comprised of members from across the various organisational departments. Historically major Projects & Programmes would have been driven and overseen by the relevant Department manager. This is now evolving to a much broader spectrum of influence but in practice it was still ultimately the will of the senior manager involved that has the main guiding effect on the management of a project from a strategic viewpoint. IE a ‘centralist’ ‘authoritarian’ approach to PM. This approach is similar to findings made in a number of studies including (Williams, 1997).

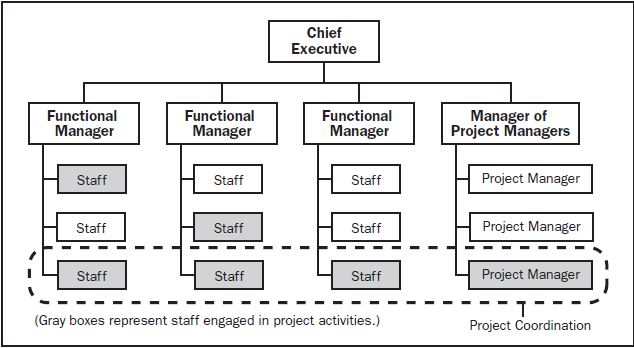

The Analog organisation configuration is loosely based along the lines of a balanced matrix approach as presented in figure 10. With this structure the project manager does not have full authority over the project, he/she mainly defines what needs to be accomplished while it is still ultimately the functional managers who have the final say on how this gets implemented and what personal are assigned to fill these needs. Control and power is shared between both sets of managers and effective outcomes will depend largely on how these relationships function as individual team members still report to their own specific functional manager and merely perform project tasks under co-ordination from the Project Manager. For larger scale projects a team member may be 100% committed to the project but ultimately they are still accountable to their own department.

Figure 10: Organisational Structure for Projects (Firebrandtraining, n.d.)

The advantages and disadvantaged of this matrix approach are explained in detail by Jack Meredith in “Project Management: a managerial approach” and these are listed below(Mantel, 1995)

Advantages include:

- The project is the point of emphasis. One individual, the PM, takes responsibility and ownership for managing the project.

- Because the project organization is overlaid on the functional divisions the project has potential access to the entire reservoir of knowledge in all functional departments

- There is less concern among team members about what happens when the project is completed than is typical of the pure project organization where they may be surplus to requirement once the project is complete.

- Where there are several projects simultaneously under way, matrix organization allows a better companywide balance of resources.

There are however disadvantages:

- Because power is shared between multiple managers when doubt exists about who is in charge or this relationship breaks down, the work of the project suffers.

- Where multiple projects are in operation and resources shared movement of these resources between projects may foster political infighting among the several PMs.

- Matrix structure contradicts a standard management principle of unity of command because project workers have at least two managers, their functional heads and the PM.

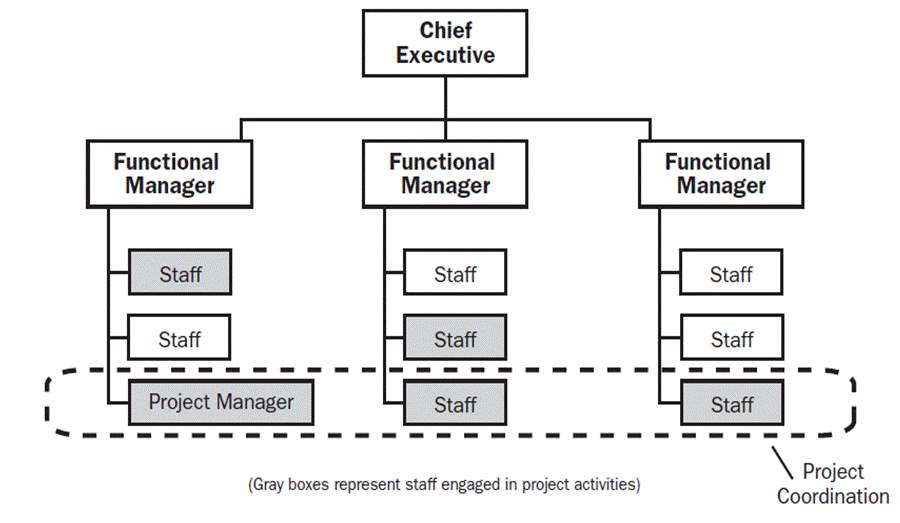

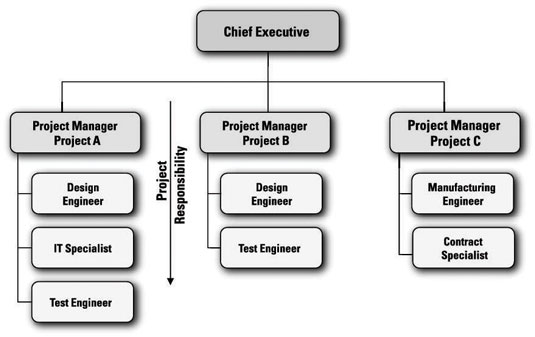

Suggested Appropriate Structure

Due to the multi-dimensional nature of the organisation there is no ‘Ideal’ model for project management structure. Analysing a number of projects that are currently in operation it could be argued that all 3 major organisational structures are used at different times or a hybrid variation of these.

- Functional Structure

- Project/Fully Projectized Structure

- Matrix Structure

Many project management practitioners would argue in favour of one or another of the organizational structures being more conductive to positive project outcomes and there is numerous research available supporting the case for choosing a particular form. There is also a number of researchers including Kerzner, H. (2017) who would state that every organizational structure comes with both advantages and disadvantages but it is possible to implement project management effectively in any organizational structure if the culture is cooperative.

For a large multi-national like Analog it is very difficult to implement a project structure that is different from the current organisation setup. This difficulty occurs for a number of reasons:

- Resistance of current managers and influencing groups.

- Cost of setting up separate autonomous groups.

- Better use of sharing resources.

- Employment security for personnel.

Analysing the research provided in the literature by Brian Hobbs & Pierre Menard (Hobbs and Menard 1993) and applying it to this organisation would give a theoretical ideal model of the Fully Projectized Structure. With this model the project is formed as a temporary unit independent from the main organisation, there are Pro’s and Con’s which will be listed below

Figure 11: Fully Projectized Structure (Portney, n/a)

Advantages:

- Project Manager has full control over the Project Resources

- Conflicts and Priority issues are minimized

- Good team integration

- Results orientated

- Fast Decision Making

There are disadvantages including additional cost and duplication of resources but for a company of this size the benefits exceed the limitations particularly for a project of critical importance. As a large organisation the company has both the personal and financial resources to commit to this type of structure.

The above would be a preferred recommendation but organizational structure has to fit within the larger social context of the organization including its culture, values, and operating philosophy; stakeholder expectations, socioeconomic, and business context; behavioural norms, power, and informal influence processes, and so on. (Morris and Pinto 2007). Taking this into account the modified recommendation would be a form of Projectized structure but with input from the various Functional managers. There is no hard and fast rule but having the resources to draw on their knowledge and expertise will be of benefit as long as the project Manager is able to control the priorities and competing interests. This is all part of the “Management of Projects” which is a core ability of every Project Manager. This setup would be similar to the Strong Matrix below but the project staff would still report to the project manager.

Figure 12: Strong Matrix Organizational Structure

Section V: Project and Organisational Maturity

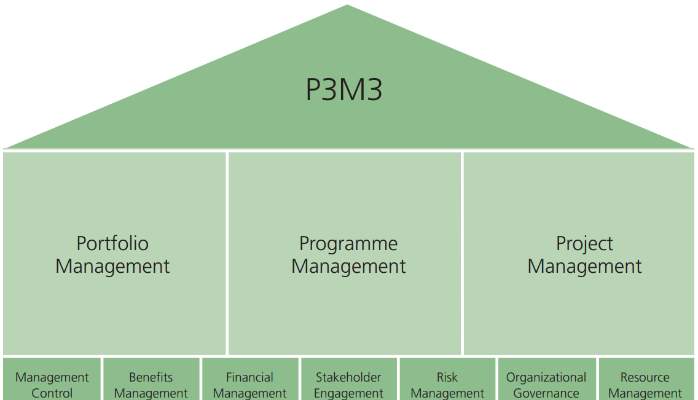

The Portfolio, Programme and Project Management Maturity Model P3M3® that is being used in this section to assess Analog Devices Project maturity is an Overarching capability maturity model containing three sub-models: (DHS, 2014)

- Portfolio Management Maturity Model (PfM3)

- Programme Management Maturity Model (PgM3)

- Project Management Maturity Model (PjM3).

The P3M3® uses a five-level maturity scoring system which the organisation will be graded on:

- Level 1 – awareness of process

- Level 2 – repeatable process

- Level 3 – defined process

- Level 4 – managed process

- Level 5 – optimized process

The organisation is then assessed using 7 Process Perspectives:

- Management Control

- Benefits Management

- Financial Management

- Stakeholder Engagement

- Risk Management

- Organizational Governance

- Resource Management

Figure 13: P3M3 Structure (Axelos, 2014)

Using P3M3® to baseline Analog’s Project performance makes it possible to identify areas where Project capability can be effectively increased. There are also a number of additional benefits including:

- Identifying areas for improvement by gaining a better understanding of strengths and weaknesses within the company.

- Providing a structure for continual improvement and progression.

- Focuses on the organisations overall maturity and not just specific initiatives.

- Can be used to justify investment in Project/Programme & Portfolio management.

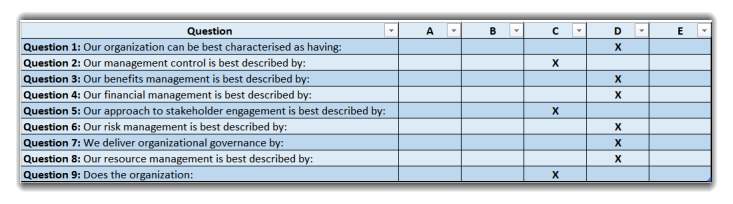

This P3M3 assessment was based at the project level and took the form of a self-assessment questionnaire containing seven questions, one for each of the process perspectives. There were also two additional questions. The first relating to this researchers opinion on the overall maturity of the organization and the final question which provides a cross check on the structural components. The resulting answer from each question is listed in the following table.

Figure 14: P3M3 Self-assessment Answers

Analysis of questions 2-8 gives the organisations position within the 7 process perspectives with regard to project maturity. Question 2: Management Control. This evaluated the internal management structure for evidence of leadership, direction, scope and what internal structures are in place for supporting these. Answer C here indicates an organisation that has a centralised approach that is applied across all projects by capable employees.

Question 3: Benefits Management. This is the process of ensuring that outcomes have been clearly defined and measureable through a structured approach. The resulting answer D indicates a benefits management program that is embedded with a focus on project outputs contributing to business performance.

Question 4: Financial Management. Answer D here shows a project organisation with a good control of financial functions. Project budgets are controlled and cost versus performance is monitored effectively.

Question 5: Stakeholder Engagement. The evaluated response C shows an organisation with a constant and central managed approach to stakeholder management. These stakeholders both internally and externally are identified and involved throughout the process.

Question 6: Risk Management. This would be considered one of the core areas of the organisation. Due to the nature of the business Risk would always be considered a key focus. Answer D again shows that the Risk management aspect of Projects is working effectively. It is embedded and its value can be demonstrated.

Question 7: Organizational Governance: This is concerned with how projects are aligned to the strategic direction of the organization. In this question the company again scored highly showing a Project Management program that is transparent, embedded and clearly aligned with overall business governance.

Question 8: Resource Management. This penultimate question assessed the management of all types of resources that are required for project delivery. Again similar to the majority of questions Answer D shows a resource management capability that is dealt with effectively and at the strategic level of the organisation.

Overall the organisation scored highly at levels C-D in all questions. Management Control and Stakeholder Engagement were slightly lower that the remaining processes but this can be explained by the wide variation and quantity of projects in operation within the organisation.

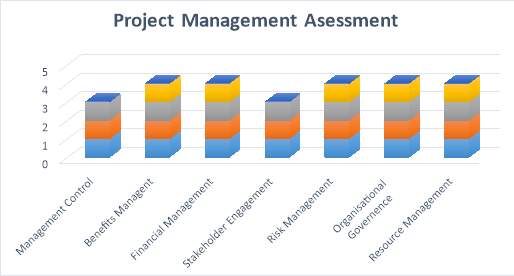

The results to these questions are now transposed in the following graph to give an overall Maturity level for Project Management.

Figure 15: Project Management Maturity Levels

In summary Analog Devices shows a level 3 Project Management maturity overall which indicates an organisation that has its project processes defined and confirmed as a part of standard business process. Analysing the 7 individual process further it can be seen that there is variation amongst them with the majority achieving level 4 maturity. However the Level-3 results for Management Control and Stakeholder Engagement bring the overall level down.

One point to note. According to the P3M3® Self-Assessment guide (ogc.gov.uk, 2014) It should be noted that self-assessment has a tendency to result in some optimism bias and that although it will have indicative values of process capability and the overall organizational maturity in relation to portfolio, and/or programme and/or project management these results need to be considered and further analysis may be required.

The above results would be considered positive for a manufacturing industry of this scale. Previous research has suggested that 90% of organisations only operate at level 1 & 2 (Project Smart, n/a).

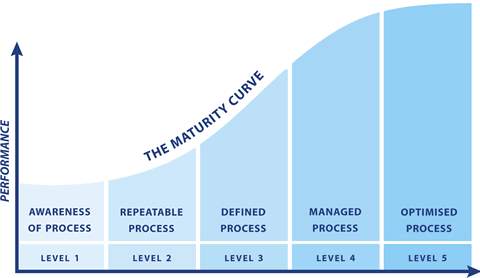

Figure 16: P3M3 Maturity Curve (IXL Consulting, 2017)

In order to progress further on the maturity curve there are a number of steps Analog will need to take.

- Evaluate where the organisation is today as seen by this report.

- Discuss where the organisation wants to get to and if the return is worth the investments.

- Plan how it will get there and what needs to be addressed.

- Have a process to evaluate when the changes are implemented.

As an Organisation Analog would strive to reach the higher levels of Maturity and in most aspects this is being achieved. Most top level managers internally if asked would claim that they are or should be positioned higher on the maturity curve figure 16 but the current report indicates otherwise. Continuous improvement is already embedded within the ethos so the foundations are currently in place and it is a matter of addressing the outstanding issues. In terms of the process requirements to progress further the obvious ones are to address the shortcomings at Stakeholder Engagement and Management Control. Both of these need further review and a detailed analysis of the required techniques and increased focus that will be required to align with the remaining processes.

Section VI: People and Competency Development

With the growth in popularity of Project Management there is also a growing recognition about the importance of managerial competence and subsequently to this the relationship between project success and project manager competency fit. This was discussed in a number of papers including (Malach‐Pines et al. 2009) which focused on the personality of the project manager relative to project success and previously by researchers including (Mumford et al., 2000) who found that leaders with certain characteristics are more likely to succeed in certain organisations. I.e. personality characteristics affect outcomes. (Clarke, N. 2010) subsequently found that emotional intelligence has been suggested to be particularly important in projects due to the nature of this form of work organization

All of this adds up to a picture of project success being influenced by the attributes and characteristics of the manager in charge. Many research papers have attempted to put structures around the definition of project management competence. For example (Partington et al. 2005) used an interpretive approach known as phenomenography to study the management of 15 strategic programmes spread over seven industry sectors. Their findings resulted in a recommendation of a framework of 17 key attributes of programme management work, each conceived at four levels in a hierarchy of competence.

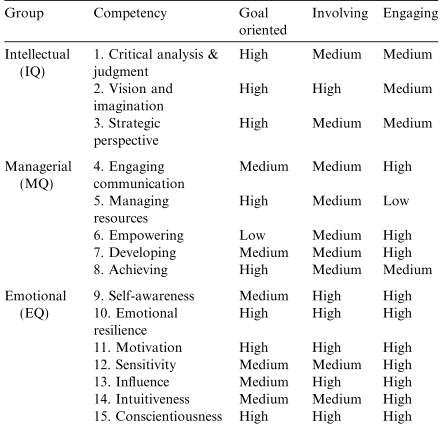

(Dulewicz & Higgs 2003) offered a leadership model that listed 15 leadership competencies and three styles of leadership which were then analysed by (Müller and Turner 2010) who compared these profiles of successful project managers in a number of different types of projects.

Figure 17: Leadership Profiles for Organisational Change Projects

Relating this research to Analog Devices the organisation in question it can be assumed that because of the project mix involved in an organisation of this size all of these attributes will be required at various stages. The company places a big emphasis on upskilling and education. All employees are actively encouraged in tandem with their relevant manager to identify and pursue areas of education that they feel are beneficial to their current or even future roles. Figure 18 below gives the company statement of intent as listed in every employee’s online portal.

Figure 18: ADI Learning Development Statement

These education opportunities could take many forms including:

- External University education in any relevant discipline such as this MSc in Project Management.

- eCourses offered both internally and externally from recognised educators such as Stanford University.

- Internal Classroom education.

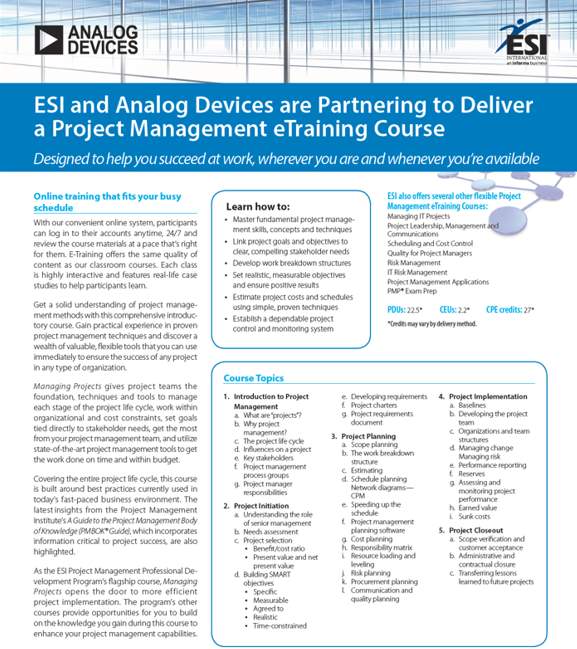

All of these courses will be supported and facilitated by the company if approved. This support would typically involve monetary payment of course fees and time off work for classroom sessions. The major Project Management Competency program that Analog Devices currently offer is a new eTraining course which covers all the fundamental project management areas. This is a generic offering designed to cover as many areas as possible and there are currently 40 employees undertaking this.

Figure 19: Project Management eTraining

Further to the designed Project Management education a number of the core competencies listed earlier may also be improved by other courses which are continuously offered internally such as:

- Management Skills Level 1-3

- Presentation Skills

- Handling Change

- Coach for Excellence

- Conflict Handling

With regard to recommendations the company already has a number of excellent structures:

- Multitude of courses offered

- Support for employees wishing to get involved

- Internal structures to allow employees identify and partake in courses they feel are relevant to their development

The only change this report would recommend would be to increase the publicity and awareness around Project Management and its relevance to all groups. This could be further enhanced by the offering of a deeper level of Project Management training and education which encompasses as many relevant employees as possible.

Assignment of Project/Programme Managers

Assigning a Project Manager should be considered a key strategic decision within the organisation particularly as the managers competencies have been shown to positively affect the outcome of a project. (Turner, J. R. & Müller, R. 2005) reviewed the literature on project success factors and found that it has largely ignored the impact of the project manager, and his or her leadership style and competence, on project success.(Crawford 2005)found that the competence of project managers is clearly a vital factor but is difficult to quantify and that the majority of research into this is based on project management practitioners rather than independent researchers.

Project managers within Analog Devices are typically assigned by the Area manager who has requested the project. In certain large scale situations the project manager may be specifically hired but these occurrences are against the normal default of internal appointment. In a lot of cases they are part time assigned to the project with a continuing responsibility also to their current functional manager and this in itself causes some concern. The other big issue is that the evaluation of project manager capability is not currently structured within the organisation. Selection for projects is based on either managerial preference or availability of a resource. This would typically involve a competent employee with the relevant departmental experience who may or may not have a Project Management background.

In summary the current system is effective for small scale projects however there should be greater consideration given to recognising Project Management competencies and how these may be structurally evaluated. Thought should also be given to appointing managers from outside of the functional group to encourage new ideas and fresh thinking. The current model lends itself to conservatism and a tendency to structure the project based on the will of the senior manager involved rather than best practice.

Section VII: Stakeholder Analysis

In any major internal project one key function of the project team is stakeholder management.

The classic definition of a stakeholder is “any group or individual who is affected by or can affect the achievement of an organization’s objectives” (Freeman 1984). Stakeholder management has been shown to be critical to the success of a project and this certainly is an area that does need consideration in an organisation of this scale. A typical stakeholder analysis involves identification of stakeholders, their needs and levels of influence within the organization and on the project itself. Strategies then need to be developed and plans made to manage stakeholders throughout the project life-cycle. (Turner 2007 P.619)

The first step in the stakeholder analysis was to identify. Within the organisation the stakeholders will vary depending on the scale and scope of the project however for this report it is the senior management team within the manufacturing operations group that are being considered. For that there are 5 people to consider.

- VP of Operations

- Director of Manufacturing

- Functional Engineering Manager 1

- Functional Engineering Manager 2

- Functional Engineering Manager 3

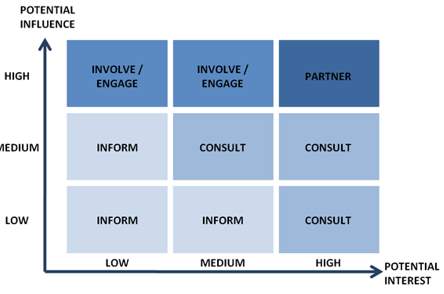

These five employees form the core operations management team for the Limerick manufacturing department and ultimately are responsible for company direction and alignment to corporate strategy within the site. Now that they have been identified Step 2 involved determining their potential interest and influence level. For this section of the report a stakeholder map was used similar to figure 20 below to determine the required level of engagement with each of the management team.

Figure 20: Stakeholder Map (Innovation for Social Change, 2014)

As all of the identified stakeholders are members of the senior management team it can automatically be assumed that their Potential influence is rated ‘High’ on the map. The next section involved determining their likely reaction to a Project/Programme improvement initiative based on this report. This data is then added to a more detailed stakeholder register which will form the basis of a unique plan to successfully engage each of them. There are many variations of a stakeholder register but for this report it is a variation of the listed one in (Turner 2007)that will be used.

| Manager | Core Responsibility | Objectives | Potential Interest | Support | Influence |

| Operations VP | Overall Site Direction | Better overall control and visibility of programmes in operation. | M | M | H |

| Manufacturing Director | Co-Ordination of all functional groups. | Generate efficiencies and better use of resources. | H | H | H |

| Engineering Manager 1 | R&D Engineering | Better Co-Ordination of Projects. | H | H | H |

| Engineering Manager 2 | Manufacturing Output | Minimum Disruption to daily operations. | L | L | H |

| Engineering Manager 3 | Finance | Potential Cost savings. | H | H | H |

Figure 21: Senior Management Stakeholder Register

As can be seen there is a wide variation in support and interest levels across the group. Each member will have their own interest in the project either succeeding or failing but it is the responsibility of the project manager to effectively manage the expectations and support within the organization.

Stakeholder Management Strategy

This following section details the individual strategy for each stakeholder. This strategy will be determined based on their current standing within the stakeholder map and where the project would ideally need them to be located for maximum success potential. Research suggests a number of options when it comes to stakeholder management. The suggestions in this report are based primarily on the research of McElroy and Mills(Turner 2007)

Figure 22: Stakeholder Commitment Map

Employee 1. Operations VP

Current Commitment: Passive Support.

Desired Commitment: Passive Support or Above.

Plan: Active engagement and consultation. Do not overload with the minor details but keep informed through Monthly status update information sessions.

Comments: Currently open to all forms of suggestion that will improve overall site performance and alignment to current business strategy. Not tolerant to long drawn out processes so will expect visible results within a relatively short period of time.

Employee 2. Manufacturing Director

Current Commitment: Active Support

Desired Commitment: Same

Plan: Keep involved and informed at all stages. Consult for opinion on overall direction.

Comments: Wants project to succeed and will ensure the involvement of the functional departments. Seniority means her positivity will ensure remaining managers remain engaged.

Employee 3. Engineering Manager 1

Current Commitment: Passive Support

Desired Commitment: Passive Support

Plan: Active engagement and communication.

Comments: The manager with potentially the most to benefit. Currently has a number of project teams reporting to him and is constantly struggling to resource the increasing project base. Enthusiastically interested and has the standing to influence some of the less positive voices within the department.

Employee 4. Engineering Manager 2

Current Commitment: Passive Opposition

Desired Commitment: Same or Passive Support

Plan: Keep involved in all aspects of the project with frequent communication. Work to increase their understanding of the project benefits and potential successful outcomes.

Comments: A key Stakeholder and the primary resistance to the project. This manager’s main concern is a drain or realignment of resources having an effect on core manufacturing output. Typically he is slow to change or modify work structures so this needs to be allowed for.

Employee 5. Engineering Manager 3

Current Commitment: Passive Support

Desired Commitment: Active Support

Plan: Need to lower commitment level. Keep involved and informed but control influence at a strategic level.

Comments: Manager is over enthusiastic to this type of project but has a vested interest to steer it in one direction, namely a purely cost saving perspective. Need to maintain their support and keep them involved but as part of a larger team to ensure no undue influence.

In summary all five potential stakeholders from the senior management team will need to be individually planned for as there are differing needs and expectations. The initial expected support for the improvement project will vary from Passive Opposition to Active Support and this will need to be factored into the overall plan particularly as all members of the team are high influencing members of the organisation. The critical factor is ensuring that all 5 managers are effectively communicated and consulted with and this will be done through a number of channels:

- Formal group status update meetings.

- Regular e-Mail communication.

- Informal one-to-one discussions.

Employee 2 is the critical identified Stakeholder. As managing director they have influence over the remaining management team so correct perception and involvement here will make things a lot smoother. Engineering Manager 2 is the primary opposition to the project and it is unlikely that will change in a major way. However the intended action plan is to educate and highlight the potential benefits plus give consideration to what they consider important objectives.

The final point to note is that these changes with regard to how projects are managed onsite may ultimately form part of a larger initiative with regard to projects/programmes. Therefor ensuring these key stakeholders are managed correctly at this phase is critical in terms of obstruction that may potentially occur at a future junction. As suggested by (D’Herbemont & Cesar 1998) even if they don’t look like allies at first the important factor is to manage the respective factions and allow flexibility and a willingness to change on all sides through co-ordinated action and not fall into the trap of labelling managers as for or against something

Executive Summary

In summary this report was based on the Analog Devices Limerick Manufacturing departments organization and management from a projects dimension. Overall analysis shows a mature organization at the project level with a P3M3 level 3 assessment. Investigation of these findings also showed a willingness and solid foundation to potentially progress to an even higher level with the implementation of a select number of recommendations. Strategy alignment is presently controlled by the closer amalgamation of the worldwide manufacturing sites through combined senior management responsibility. However the portfolio and project selection process is still fractured with wide variations between differing groups with regard to implementation and this is something that is against best practice teachings.

Current organizational drivers are heavily influenced by alignment to the Shingo model for enterprise excellence which promotes alignment of management systems and the wise application of improvement techniques across the entire organizational enterprise. This corporate drive for improvement should help to support a number of the findings in this report most importantly a consideration of what type of management structure best supports project development and implementation most efficiently. With regard to project drivers the critical factors currently are Quality, Risk and Cost which would be common within the industry. However there needs to be greater awareness and understanding of the benefits of the other knowledge areas which are not currently considered as important.

Throughout the senior management team in Limerick there is underlying support and backing for a program of change and this is something that should be implemented. People and competency development is very well engrained in corporate culture and this is to be commended. There are numerous avenues for personnel employee development and upskilling which should be encouraged particularly with regard to structured PM learning. Project Lifecycle is similar to a lot of other common structures such as the PMI and it is efficient however greater emphasis needs to be given to learnings post project completion and a better sharing of learnings across the group.

Bibliography

Shingo Institute, 2013. The Shingo Model for Operational Excellence. In: s.l.:s.n., p. 1.

Project Management Institute, 2008. A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK Guide). 4th ed. Pennsylvania: PMI.

Zwikael, O., 2009. The Relative Importance of the PMBOK Guide’s Nine Knowledge Areas Suring Project Planning. Project Management Journal, pp. 94-101.

Project Management Institute, 2013. A guide to the project management body of knowledge (PMBOK¬ guide). In: s.l.:Project Management Institute, p. Chapter 11.

Crawford, L., Pollack, J. (2007) ‘How Generic Are Project Management Knowledge and Practice?’, Project Management Journal, 38(1), 87–97.

Morris, P.W.G., Crawford, L., Hodgson, D., Shepherd, M.M., Thomas, J. (2006) ‘Exploring the role of formal bodies of knowledge in defining a profession – The case of project management’, International Journal of Project Management, 24(8),710

Songer, A., 2016. PRINCE2 AND PMBOK: What they are and what they are not. [Online]

Available at: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/prince2-pmbok-what-austin-v-songer- [Accessed 26 October 2017].

Ross, D. W. & Shaltry, P. E. (2006). The new PMI standard for portfolio management. Paper presented at PMI® Global Congress 2006—EMEA, Madrid, Spain. Newtown Square, PA: Project Management Institute.

Archer, N.P. and Ghasemzadeh, F. (1999) An Integrated Framework for Project Portfolio Selection. International Journal of Project Management, 17, 207-216.

Martinsuo, M., Lehtonen, P.I., 2007. Role of single-project management in achieving portfolio management efficiency. International Journal of Project Management 25 (1), 56–65.

Caballero, H. C., Chopra, S., & Schmidt, E. K. (2012). Project portfolio selection using mathematical programming and optimization methods. Paper presented at PMI® Global Congress 2012—North America, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada. Newtown Square, PA: Project Management Institute.

Blichfeldt, B.S., Eskerod, P. (2008) ‘Project portfolio management – There’s more to it than what management enacts’, International Journal of Project Management, 26(4), 357–365.

solutionsiq, 2017. solutionsiq. [Online] Avalable at: https://www.pinterest.ie/pin/464996730246345711/ [Accessed 10 October 2017].

Hass, Kathleen (2007). ‘The blending of Traditional and Agile Project Management’. PM World Today IX(V)

Dai, & Wells. (2004). An exploration of project management office features and their relationship to project performance. International Journal of Project Management, 22(7), 523-532.

Julian, J. (2008). How project management office leaders facilitate cross‐project learning and continuous improvement. Project Management Journal, 39(3), 43-58.

Williams, T., 1997. Empowerment versus Risk Management ?. Internation Journal of Project Management, p. 15.

Firebrandtraining, n.d. Organisational Structure for Projects. [Online]

Available at: http://www.firebrandtraining.co.uk/learn/pmp/course-material/organisation-structures

[Accessed 2017 October 21].

Mantel, J. R. M. &. S. J., 1995. Project Management: a mmanagerial approach. Third ed. New York: Wiley. P.199

Kerzner, H. (2017) Project Management Organizational Structures, in Project Management Case Studies, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, NJ, USA. doi: 10.1002/9781119389040.ch4

Hobbs, B. & Menard, P. (1993). Organizational choices for project management. In P.C. Dinsmore (Ed), The AMA handbook of project management. New York: AMACON

Portney, S. E., n/a. 3 Structures For Project Administration. [Online]

Available at: http://www.dummies.com/careers/project-management/3-structures-for-project-administration/

[Accessed 25 October 2017].

Morris, P.W.G., Pinto, J.K. (2007) The Wiley Guide to Project Program & Portfolio Managment, John Wiley & Sons, Inc. p.Xi

DHS, 2014. P3 Assessment Report. [Online]

Available at: https://www.humanservices.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/p3m3-assessment-report.pdf

[Accessed 25 October 2017].

Axelos, 2014. What is P3M3®?. [Online] Available at: https://www.axelos.com/best-practice-solutions/p3m3/what-is-p3m3 [Accessed 23 October 2017].

ogc.gov.uk, 2014. P3M3 Self Assessment. [Online]

Available at: http://www.strategies-for-managing-change.com/support-files/maturity-model-self-assessment.pdf

[Accessed 26 October 2017].

Project Smart, n/a. Improving performance using maturity models. [Online]

Available at: https://www.projectsmart.co.uk/portfolio-programme-and-project-management-maturity-model.php

[Accessed 27 October 2017].

IXL Consulting, 2017. Maturity Models. [Online] Available at: http://www.ilxconsulting.com/au/maturity-models/

[Accessed 24 October 2017].

Malach‐Pines, A., Dvir, D., Sadeh, A. (2009) ‘Project manager‐project (PM‐P) fit and project success’, International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 29(3), 268–291, available: http://www.emeraldinsight.com/doi/10.1108/01443570910938998. [Accessed 29 October 2017].

Mumford, A., Zaccaro, S.J., Johnson, J.F., Diana, M., Gilbert, J.A., Threlfall, K.V., 2000. Patterns of leader characteristics: implications for performance and development. Leadership Quarterly 11 (1), 115–133.

Clarke, N. (2010). Emotional intelligence and its relationship to transformational leadership and key project manager competences. Project Management Journal, 41(2), 5–20

Partington, D., Pellegrinelli, S., Young, M. (2005) ‘Attributes and levels of programme management competence: An interpretive study’, International Journal of Project Management, 23(2), 87–95.

Dulewicz, V., Higgs, M., 2003. Design of a new instrument to assess leadership dimensions & styles. In: Henley Working Paper HWP 0311. Henley Management College, Henley-On-Thames, UK

Müller, R., Turner, R. (2010) ‘Leadership competency profiles of successful project managers’, International Journal of Project Management, 28(5), 437–448.

Turner, J. R. & Müller, R. (2005). The project manager’s leadership style as a success factor on projects: a literature review. Project Management Journal, 36(2), 49–61.

Crawford, L. (2005) ‘Senior management perceptions of project management competence’, International Journal of Project Management, 23(1), 7–16.

Freeman, R. E. 1984. Strategic management: A stakeholder approach. Boston: Pitman. Freeman, P.4

Innovation for Social Change, 2014. Do You Know your Stakeholders?. [Online]

Available at: http://innovationforsocialchange.org/stakeholder-analysis [Accessed 27 October 2017].

Turner, R. (2007) Gower Handbook of Project Management 4th Edition, Gower Handbook of Project Management. P.619,756,771-773

D’Herbemont, O. and Cesar, B. (1998) Managing Sensitive Pro-jects. A Lateral Approach, Macmillan, Basingstoke. P.211-213

Cite This Work

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing stye below:

Related Services

View allRelated Content

All TagsContent relating to: "Project Management"

Project Management involves leading and directing a team towards a common goal, ensuring that all aspects of a project are completed successfully and efficiently. Project Management can include the use of various processes and techniques, using knowledge and experience to guide the team towards the end goal.

Related Articles

DMCA / Removal Request

If you are the original writer of this dissertation and no longer wish to have your work published on the UKDiss.com website then please: