Midwife Experiences of Maternity Care for Asylum Seekers

Info: 10937 words (44 pages) Dissertation

Published: 22nd Feb 2022

ABSTRACT

Purpose: The purpose of this dissertation is to investigate midwives’ experiences of providing maternity care to women seeking asylum. This dissertation concentrates on the experiences and view of midwives and women to determine areas requiring development and improvement.

Method: A systematic literature review of databases British Nursing Index, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature, PubMed, MEDLINE, Cochrane Library. Inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied to narrow the search results. Five Key papers were identified and critiqued using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme.

Findings: Midwives felt unprepared to support these women in a culturally appropriate holistic way. Training, advice and support was lacking and that which was received was often outdated and inconsistent, resulting in many women accessing care later in pregnancy, sometimes not until the point of delivery

Conclusions: Women seeking asylum during pregnancy need to be able to access holistic care and support earlier in their pregnancy to improve outcomes. The barriers faced by these women are contributing to traumatic negative experiences leaving them feeling unsupported, ignored, traumatised. Midwives need to be able to access up to date information about rights, entitlements, communication methods and other support to provides holistic care to these already vulnerable women.

Contents

Chapter 1: Introduction……………………………………………………… Page 5

Chapter 2: Methodology……………………………………………………. Page 7

Chapter 3: Critical Review…………………………………………………. Page 10

3.1 Barriers to communication…………………………………………… Page 10

3.2 Barriers to the access of maternity care…………………………… Page 15

Chapter 4: Service Improvement………………………………………… Page 19

4.1 Aim………………………………………………………………………. Page 20

4.2 Measures………………………………………………………………… Page 20

4.3 Ideas……………………………………………………………………… Page 21

4.4 Plan, Study, Do, Act cycle……………………………………………. Page 22

4.5 Conclusion……………………………………………………………… Page 23

Reference list………………………………………………………………… Page 24

Appendix 1 …………………………………………………………………. Page 32

Appendix 2 ………………………………………………………………… Page 33

Appendix 3 ………………………………………………………………… Page 34

Introduction

The refugee council (1951) define a refugee as “a person who owing to a well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion, is outside the country of his nationality and is unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to avail himself of the protection of that country; or who, not having a nationality and being outside the country of his former habitual residence as a result of such events, is unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to return to it.”

Pregnant women seeking asylum in the United Kingdom have been recognised as a group of vulnerable women, as identified in the confidential enquiry into maternal and child health (CEMACH, 2011). They often face complex social factors, Poor maternal health and undiagnosed medical and mental health conditions and additional need in pregnancy (NICE, 2010), Much of this relates to suffering from the physical and psychological effects of fleeing from persecution and traumatic circumstances.

All women seeking or granted asylum in the UK are entitled to receive free maternity care. However, there are many barriers preventing this disadvantaged group from accessing and participating with maternity services. These include, communication (RCOG, 2010), knowledge of the NHS and entitlements (Department of Health, Social Services and Public Safety of Northern Ireland, 2004), dispersal by the United Kingdom border agency (UKBA) (Feldman, 2013), and cultural differences and discrimination (Tobin, Murphy-Lawless and Beck, 2013)

Simultaneously midwives providing care are also face challenges such as the complexity of the asylum system and legislation, Lack of training in cultural awareness, poor communication skills, insufficient time and access to interpreters. Midwives describe the care they provide as Substandard and unsatisfactory.

In (2010) the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) implemented guidelines which aimed to improve maternity services for women with complex social factors. Woman centred care holistic approach was promoted. However, seven years later asylum seeking women’s needs are not being met. Poor antenatal care and communication difficulties are impacting on their experiences. The (2010) nice guidelines recommended training for midwives to improve their understanding of asylum seekers specific needs and how to meet them. However, the 2015 government spending review cut the Department of Health budget for non frontline services including medical by 1.5 billion. The evidence suggests there are inadequacies in care. This dissertation aims to review and critique the most current research and will conclude with a recommendation for achievable and sustainable service improvement.

Methodology

This chapter aims to look at the approach used to complete a thorough systematic critical literature review. Rees (2011, p77) states “A review of the literature is the systematic and critical examination of a defined selection of published literature on a particular topic or issue”. Research is a means of assessing and evaluating what we do as midwives, and in order to complete this, midwives are required to be able to appraise and synthesise the research available and evaluate evidence about the effectiveness of their practice and healthcare interventions (NMC, 2008)

The approach used to achieve a systematic review was to identify a topic of interest and understand the issues surrounding it. Before a search of databases was performed I began by looking into the availability and experiences of access to maternity care for pregnant women seeking asylum in the UK. Through this initial search I found some organisations and secondary sources of information. Among these were UK border Agency, Asylum Aid, Maternity Action, UK Government Asylum Support, City of Sanctuary and the Royal College of Obstetrician and Gynaecologists (RCOG). These sources assisted my wider reading and understanding around the topic. They enabled me to look at the policies and guidelines which provide instruction to those caring for women seeking asylum in pregnancy from border agencies to health care practitioners and have allowed me to assess the care being provided and delivered.

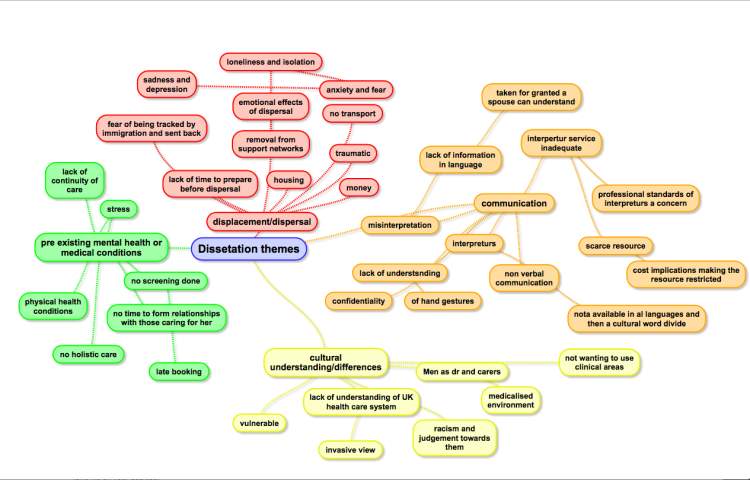

A mind map was produced to to allow exploration of the topic and clarify the issues and my personal understanding at this point. (Appendix 1) The next step was to perform an online search of The University of the West of England (UWE) library using the phrase ‘asylum seekers experiences of accessing maternity care’ this returned 869 results. Refining the search to peer reviewed and full online text reduced the results to 179. By further restricting the filters to the last 5 years and peer reviewed returned 82 results.

To help to identify further appropriate research papers a literature search strategy table was produced (Appendix 2) using synonyms this identified key search terms to be used in database searches. Databases relevant to the question and health and social care were searched including OVID maternity and infant care a key information resource used by maternity health care professionals and student midwives worldwide to support their research, BNI, PubMed, Psycinfo, science direct, CINAL and The Cochrane Library all of which are recommended by the RCM (2014)

The following Key terms were used interchangeably to investigate the objectives of the literature review; ethnic minorities, Asylum seeker, refugee, experiences, barriers, obstacles, feelings, maternity, care, access, antenatal, postnatal, labour, pregnancy and birth. Boolean operators (AND, OR) were used to define logical relationships between the search terms and refine the process (Bettany-Saltikov, 2012).Truncation* was used to search for all alternatives to words which are closely related, this ensured a through search of multiple forms of the key words (Rees, 2011) The search also included the process of back chaining through a reference lists of relevant articles to search for other relevant primary sources (Rees, 2015) Saturation was reached once no new articles were found (Polit et al, 2001).

Exclusion and inclusion criteria was also included in the literature search strategy table. Inclusion criteria included primary research which explored women’s experiences of access to maternity care in the UK whilst seeking asylum. This focused on qualitative research focusing on interviews, questionnaires and surveys. Inclusion also included Research which has been published and peer reviewed. Studies were excluded if they explored aspects other than women’s experiences to accessing maternity care during the asylum process or if they were not written in English. Exclusion also applied if they were from countries without a comparable demographic to the UK and Papers older than 10 years to ensure the evidence presented is the most up to date and related to practice (Moule and Goodman, 2014)

Five qualitative primary research studies were selected for critical analysis of the contents using the Rees framework for critiquing qualitative research tool (Appendix 3) (Rees, 2011) three themes stood out throughout the critical analysis of the papers. These are

- Communication

- Lack of cultural understanding

These will be explored in more detail in the next chapter.

Chapter 3 – Critical review

In 2010 the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) published guidelines for antenatal care of women with complex social factors. The guideline acknowledges asylum seekers and refugees as one of the most vulnerable groups as identified in the Confidential Enquiry into Maternal and Child Health (CEMACH, 2011) report. The NICE (2010) guideline recommends asylum seekers and refugees should be provided with an interpreter (a link worker or advocate, not a family member) who can communicate in the woman’s preferred language.

This chapter will evaluate and synthesise the evidence of the two themes identified from the available evidence. ‘Barriers to communication’ and ‘Barriers to access of health care’. The themes will concentrate on how midwives can improve maternity care experiences for asylum seekers in the United Kingdom (UK).

3.1 Barriers to Communication

For those seeking asylum in the UK communication is one of the most challenging barriers (RCOG, 2010). Effective communication between midwives and women is essential, allowing the midwife to provide an individualised care plan, build a relationship and to provide healthcare promotion and education. According to Ameh and Broek (2008), good communication is the key to assisting midwives in improving maternity care and the lives of pregnant asylum seekers in the UK. Lyons (2008) suggests communication issues are the most common difficulty faced by midwives when caring for ethnic minority women. These women are not able to provide a full medical history, which results in inappropriate clinical decision-making and increased morbidity/mortality as recognised by the Mothers and Babies Reducing Risks through Audits and Confidential Enquiries (MBBRACE) 2015 report.

This theme will look at the barriers asylum seekers face when communicating with health professionals. Three studies were identified which all looked at the impact of communication and the barriers faced when communicating with health professionals whilst accessing maternity care. Philmore (2014), Feldman (2013) and Tobin and Lawless (2014).

Philmore (2014) undertook a qualitative mixed methods study which aimed to explore the reason new migrants do not access antenatal care. Non probability purposive sampling was used, this enabled the researchers to select women who had recently moved to the UK and utilised maternity services. A semi structured questionnaire was completed via interviews. When designing a questionnaire, the researcher should ensure that they are “valid, reliable and unambiguous (Zohrabi, 2013). This was achieved through co designing the questionnaire with maternity professionals and migrant women. The study does not state if the maternity professionals involved in the design of the questionnaire are specialists within this area of maternity care, this would impact on the validity and reliability of the study.

82 questionnaires were completed respondents were identified through children’s centres and community groups, using a snowballing approach existing study participants recruit further participants from their acquaintances (Rees, 2012). This method would omit women from the sample who are isolated or who choose not to attend groups. The scale of coverage shows this method is more likely than other approaches to obtain data, based on a representative sample, therefore being transferable to a population. However, the data produced is likely to lack depth. The responses were themed using a systematic thematic analysis, enabling the researchers to move their analysis from a broad reading of the data towards discovering patterns and developing themes (Braun and Clarke, 2006).Thirteen women were then identified with different characteristics from the larger group. These women were asked to participate in, in depth interviews, the narratives provided data which matched and clarified the themes identified through the questionnaire.

Triangulation of the results was achieved through 18 in-depth interviews with maternity professionals, via email or telephone. This enabled the researchers to look at different perspectives and explore specific experiences. Rees (2011) states Triangulation permits the researcher consolidate and confirm the findings of the data collection, increasing the credibility and validity of the research. Polit and Beck, (2008) suggest ‘telephone interviews are a convenient method of collecting data if the interview is short, specific and not too personal. Nonetheless telephone interviews can be subject to interruption’s and loss of continuity, they also rely upon the midwife’s memory recall and small pieces of information which form the whole picture can be missed. The lack of visual cues via phone interviews results in a loss of context and compromises building rapport, probing and interpretation (Novick, 2008).

Ethical approval was given prior to the research study and Informed consent was achieved by discussing the nature and purpose of the study. Participants were given the opportunity to ask questions but the study does not specify if the participants were given the right to withdraw, how the information was anonymised, or how the data was secured. (Wood and Ross-Kerr, 2006) This would have would have strengthened the credibility of the study.

Philmore (2014)findingshighlighted a lack of inadequate interpreting and the use of family as interpreters.Philmore acknowledged women were failing to access maternity services because of their limited ability to communicate with midwives. They felt unsupported and vulnerable as access to language translation services was often poor and when available was associated with many issues which deterred its use. Interpreter services such as ‘Language Line’ and the ‘Big Word’ are frequently required but the services appear to be limited or unreliable in many areas, resulting in difficulty in accessing them. (Gerrish et al 2004; MacFarlane et al 2009; Hadziabdic et al 2010). Family were frequently used as interpreters, excluding women from conversations about their own care.

Feldman (2013)aimed to explore the experiences of asylum seeking women dispersed during pregnancy and the impact on their maternity care. The qualitative research used semi structured in-depth interviews. Semi structured interviews combine standard questions asked to all participants with the opportunity for the interviewer to explore the topic further, allowing for a richer in-depth data through spontaneity of both parties (Rees, 2011). The sample consisted of 20 women who had been dispersed or held in accommodation centres by the United Kingdom Border Agency (UKBA). Women were invited to participate through local refugee support organisations ensuring the sample was representative of the population required. Interpreters were provided to enable women with limited or no English to participate in the research when they may otherwise be excluded. Squires (2009) suggests Interpreters personal experiences can influence the way they translate and interpret the responses they receive. Some medical terminology can be difficult to translate into other languages, making it difficult to convey the meaning from one language to another. Therefore, the interpreter is not unbiased and this needs to be taken into account when analysis occurs (Temple, 2002).

Feldman (2013) study echoed Philmore (2014) who also interviewed midwives as part of the study. Interviews conducted via telephone, aimed to explore the midwifes’ experiences of caring for asylum seekers and refugees. The reliability of the interviews would be subject to similar themes as discussed previously leaving the validity of the results questionable. The reliability of study by Feldman (2013)could also be questioned as structured interviews are easy to replicate and quantify ensuring the results being reliable. However, there is no room for spontaneity from the participant and the data collected may not be as rich (Rees, 2011).

Feldman (2013)concluded failure to use interpreters added further stress, anxiety and burden on women. Therefore, maternity services are failing to meet the complex, health and social needs of these women. The NICE(2010) guidelines Pregnancy and complex social factors set out what healthcare professionals as individuals and antenatal services as a whole, can do to address these needs and improve pregnancy outcomes. The report highlights the extreme level of misunderstandings which, woman may face. The use of interpreters is crucial to supporting women and helping prevent their experiences from becoming traumatic and preventing future mental health problems

Tobin and Lawless (2014)undertook a qualitative study which aimed to explore midwives’ experiences of providing maternity care to women seeking asylum. A purposive sample of 10 midwives was selected. Purposive sampling can be used to produce maximum variation within a sample (Rees, 2011). This captures a range of perspectives allowing the researcher to identify common themes which are evident across the sample. It can provide bias results but the method aims to achieve the opposite by ensuring it provides the researcher with a detailed understanding of the person’s experiences. (Rees, 2011).

The sample of midwives in the study was small and therefore the findings could not be generalised. The findings do however provide an understanding of women’s needs which must to be met to improve the care midwives provide to this vulnerable population.The data was analysed using content analysis which reviews the narrative and identifies themes. This provided the researcher with an ecological validity as the participants are talking about their experiences and feelings, but this can be time consuming (Sutton and Austin, 2015). The researchers field notes and journals, offer an audit of decision making and allow the researcher to be conscious of their own bias, reactions and emotions to the data. Clinical supervision was used throughout and transcripts were examined by another researcher to confirm the findings. This ensures validity to the researcher.

Tobin and Lawless (2014) findings highlighted Language barriers as major cause for concern. Lack of access to professional interpreters caused a variety of problems. A reliance on family to interpret was emphasised as a problematic for both the midwives and the women. NICE (2010) recommend health professionals should be aware of the potential ethical and legal implications of their use. The use of family or friends as interpreters carries its own advantages, they are free, readily available and accessible and are familiar with the patient and their medical history (Phelan and Parkman, 1995). However, the woman’s confidentiality is compromised and this can leave her feeling vulnerable, embarrassed and uncomfortable. It can also have negative effects on relationships through misunderstandings, misinterpretation and the information can be adapted to suit the woman’s partner or family and support their agenda. This can impact upon the treatment and increase risks (Gerrish et al, 2004). Reliability to translate information correctly can occur, resulting in misconceptions of the information due to language barriers or dialect. This study was small and therefore cannot be generalised to the Larger population but could be transferable to another setting to allow findings to inform future provision of maternity care to asylum seekers (Polit and Hungler, 1997)

Philmore 2014; Feldman, 2013; Tobin and Lawless, 2014; studies all acknowledged communication as a barrier to asylum seekers and refugees accessing maternity care. Each study indicated the reoccurring vulnerability women felt due to the lack of accessible interpreters. This is confirmed by Ali and Burchett (2004) in their small scale qualitative research study investigating Muslim women’s experience of maternity services. Health professionals who participated in the focus groups identified communication as the most important barrier to providing effective maternity care. Philmore 2014; Feldman, 2013; Tobin and Lawless, 2014 similarly explored the experiences of midwives within their studies and all of these suggested that midwives are not always using interpreter services when communicating with asylum seekers and refugees, this was often due to the poor service, appropriateness of the service and lack of time and cost. Philmore and Feldman both used telephone interviews as a mean of obtaining data. therefore, compared to Tobin and Lawless (2014) the validity of their studies could be questioned, as the possibility of interruptions would be high consequently effecting the midwives recall of memory. The validity of all three studies would therefore be dependant upon the researcher and how they respond to the participants through their voice tones, emotion and body language (Anderson, 2010). Philmore (2014) used triangulation to combine interviews and questionnaire data, this addresses the issue of internal validity. Producing similar findings from different methods provides validation and assurance (Rees, 2011). The finding of all three studies do provide an insight into the communication barriers faced by asylum seekers and refugees accessing maternity care, it also gives food for thought about how these services need to be improved.

3.2 Barriers to the access of Maternity care

Asylum seekers and refugees face many complex social factors and additional need in pregnancy (NICE, 2010). These include difficulty accessing care and registering with health professionals, cultural differences, dispersal in pregnancy, discrimination and awareness of entitlements.

Tobin, Murphy-Lawless and Beck (2013) was a qualitative narrative analysis study using in-depth unstructured interviews. Unstructured interviews are particularly relevant in midwifery studies as they allow the participant voice to be heard and to gain an understanding of their perspective (Holloway and Wheeler, 2010) The aim of the study was to gain an insight into women’s experiences of childbirth in Ireland while in the process of seeking asylum. A purposive sample of 22 women was used these permitted researchers to select women who had experienced pregnancy and childbirth in the asylum process (Rees, 2011). Purposive sampling can be difficult to assess if the researcher has biased ideas about the participants (Bryman, 2012).The researcher must therefore rationalise how and why they have selected the participants (Burns, 2009). Ethical approval was obtained and participants were informed of the voluntary nature of participation and their right to withdraw at any time during the study. This ensures the safe guarding of vulnerable participants. The Nursing and Midwifery code (2015) stresses the importance of non maleficence and ensuring participants wellbeing during data collection. The Participants were reassured taking part in the study would in no way influence their application for asylum. Confidentiality was assured at every stage of the process, however there is no information about how the data was stored to protect the autonomy of the participants and ensure others did not have access to the data (Wood, and Ross-Kerr, 2006).

In-depth interviews took place in a variety of locations, this was decided by the participants. Allowing the participants to choose their environment ensures they feel comfortable, therefore allowing for richer data. Ensuring the reliability and validity of the study (Taylor et al., 2015). Interpreters were provided if required this echoed the study by Feldman (2013) which discusses the use of interpreters to allow all women to participate but talks about the way in which interpreters can influence the information in the way they translate and interpret the information. Therefore, effecting the validity and reliability of the study. Participants were engaged in the study over a period of three years and trustworthiness was assured through relationship building over this time period. Transcripts were returned to the participants for the purpose of editing or clarifying information. However, this can result in bias if the participant chooses to remove any valuable data effecting the reliability and validity of the study (Hagen, Dobrow and Chafe, 2009). Similar to the study by Feldman (2013) the researchers field notes and and journals, provided an audit of decision making and allowed the researcher to be aware of their own bias, reactions and emotions to the data. The transcripts were also examined by a second researcher experienced in analytical methods to confirm the findings and ensure validity of the data.

Tobin, Murphy-Lawless and Beck (2013) findings highlighted the medical model of care in the UK as a barrier to asylum seekers and refugees accessing care in the UK. Women felt increased sense of fear, isolation and vulnerability. Women seeking asylum or refugee status are often not familiar with the westernised midwifery model of care and often come from cultures where there is a belief that medical care or intervention is only required when there is a problem and normally in their country care would only be accessed in labour (National collaborating centre for women’s and children’s health, 2010). It is important asylum seeking and refugee women are given information on how to access care and understand how care is organised and what to expect. NICE (2010) pregnancy and complex social factors guidelines offer advice and guidance to midwives on how to address these issues and improve pregnancy outcomes in this vulnerable group.

Tobin and Murphy-Lawless (2014) conducted unstructured in-depth interviews. The aim of the study was to explore Irish midwife’s experiences of providing maternity care to women seeking asylum. A purposive sample of ten midwives was drawn from two clinical sites. The purposive sample allowed the researcher to ensure the participants had experience of providing care to women in the asylum process, ensuring that the research returns relevant information and avoids wasting time, taking samples that have nothing to do with the topic (Rees, 2012).

Unstructured interviews were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim. Unstructured interviews allow the participant to express the important aspects of their experiences and elaborate on these, increasing the validity (McLeod, 2014). However, this requires skill from the researcher knowing when to probe, it also generates a lot of data to be analysed and coded, thus being time consuming and costly (Rees, 2012). All participants were informed about the voluntary nature of participation in the study. Assurance of confidentiality was given, ensuring the researcher does not allow unauthorised people access to the data (Burns and Grove, 2009). Informed consent was obtained from participants and ethical approval was granted through a local ethical committee. This ensures ethical principle are adhered to and and participants are protected from harm. Data was analysed using content analysis to identify prominent themes.

Tobin and Murphy-lawless (2014) Concluded the concept of cultural care as an emerging strong theme. Four midwives had received varying levels of training; some had received no training at all. The women had come from culturally diverse backgrounds but had been viewed as having the same needs and requirements. This led to feelings of ignorance and stigmatisation. The study further highlighted the need for improved education in cultural competency, an understanding of the asylum process and how to help and care for women who experience pre and post migratory stress. Horvat, Horey, Romios, Kis-Rigo (2014) suggest embedding cultural competence in healthcare systems enables systems to provide appropriate care to patients with diverse values, beliefs, and behaviours, including meeting patients’ social, cultural and linguistic needs.

Both studies recognised cultural customs and beliefs and the western medicalised model of care as a barrier to accessing maternity care. Asylum seekers and refugees are known to experience some of the worst maternal health outcomes in the UK (The Marmot Review, 2010; Henderson et el., 2013) Reducing health inequalities has long been at the forefront of public health policy in many countries including the United Kingdom (Department of Health, 2012). Both studies attempted to prove midwives endeavoured to provide women centred individualised care, through sensitively responding to the women’s needs. They found this challenging due to their cultural education, beliefs and understanding. However, conflicting expectations could adversely affect the relationship where cultural and religious practices are not understood or met (Aquino, Edge and Smith, 2014). Tobin and Murphy-Lawless (2014) further recommends an evaluation of the cultural competency education programme and training in Ireland.

Four papers critiqued within the literature review have highlighted two themes which could enhance access to maternity care for asylum seekers and refugee in the UK. Philmore (2014), Feldman (2013), Tobin and Lawless (2014) and Tobin, Murphy-Lawless and Beck (2013) all highlighted the need for cultural competency awareness, information, education and training for midwives. Therefore, this theme will be taken forward to chapter 4 to develop a Service Improvement Plan.

Chapter 4: Service Improvement plan

The five studies reviewed in chapter three highlighted the difference or lack of cultural training midwives had experienced even when working with women seeking asylum in pregnancy. Understanding the processes of asylum, women’s entitlements, cultural and linguistic barriers and support given by the midwives were all highlighted as inconsistent therefore preventing and discouraging these women from accessing maternity care. Midwives are the first point of contact, it is therefore vital they are able to provide culturally competent care free from feeling discriminated against, stigmatised and disregarded

It is vital to understand the barriers being faced by midwives and women and use this knowledge to adapt an approach relevant to the problem and implement change through a service improvement plan. It is important to set realistic goals and objectives and define how these will be achieved. Changes made must be measured to ensure they impact upon the service in a positive way (Batalden et al., 2007). Langley et el (2009) ‘Service Improvement (SI) model will guide this process. Langley’s model is divided into two sections. ‘Thinking’ part comes first and consists of three fundamental questions which are essential to guide the process. Then comes the ‘doing part’ this consists of the Plan, Do, Study, Act (PDSA) cycle which helps to make the changes which need to be addressed and implemented.

Stage 1 – Thinking

Initially we need to consider what are we trying to accomplish? The studies in chapter three highlighted women seeking asylum whist pregnant are disadvantage in comparison to other groups in pregnancy, Aspects including; communication difficulties, cultural difference, financial and complex social barriers and dispersal. (Feldman,2013) The research suggests this vulnerable group would benefit from cultural competency awareness, information, education and training for midwives to enable them to enhanced access to maternity care and improve their experiences.

4.1 Aim

The aim of this service improvement plan is to provide midwives with the skills and knowledge they need to support pregnant asylum seekers and refugees to access and receive woman centred individualised maternity care. To achieve this SMART (Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Realistic and time bound) objectives have been set;

- To create an information book (electronic and hard copy) for midwives which will set out information about the process of seeking asylum, rights, entitlements, support, contact telephone numbers and complex factors to consider and cater for when caring for refugees or women seeking asylum during pregnancy.

- The book will be distributed to all Bristol National Health Service (NHS) trusts for further dissemination to the trust dependencies.

- To be reviewed and audited using Langley (2009) PDSA cycle, every 6-12 months through questionnaires’, focus groups and and annual seminar.

4.2 Measure

To assess if the Service Improvement is successful measurement of change must occur before, during and after the task. This will provide a baseline to measure improvement against and ascertain if change is happening and if the change is making an improvement. (NHS Improvement, 2012). To achieve this current services will need to be reviewed and a baseline measures set out. Baseline measures will include;

- Number of refugees or asylum seekers midwives across Bristol trusts which midwives care for.

- Number of midwives across Bristol trusts who have knowledge (if any) of the process of seeking asylum, support services, entitlements and rights or complex social factors of the women.

- Measure the local mortality and morbidity rates for this group of women.

Post measures;

- Number of refugee or asylum seekers, midwives across Bristol trusts care for. (has this improved, are women finding access to care better)

- Have refugees or asylum seekers experiences of maternity care improved?

- Has the knowledge and understanding of midwives, about how to care for this group of vulnerable women improved?

- Has the local mortality and morbidity rates of this group improved?

To establish if the services midwives give to refugees and asylum seekers have improved their care reduced judgements, discrimination, anxiety and improved the midwife woman relationship will involve women giving feedback about their care. This could be achieved through a questionnaire similar to the current NHS initiative ‘Friends and family test (2012). This would involve all women receiving assessment questionnaires to complete via email or post. A disadvantage of this method would be the low response rate (Nakash et al., 2006) a questionnaire about the care and support they have received to gauge if they have benefited from the services. A questionnaire would need to be available in many different languages, dialect and wording would need to be considered so this may become a costly method of gaining feedback. Women centred small focus groups with an interpreter may prove to be a better option they have proved particularly good at those who are disadvantaged (The Health Foundation, 2013). This would allow for the women to comment of the services and their experiences and to help develop future improvement plans. However, these may not prove as efficient as individual interviews which would be timely and expensive (The Health Foundation, 2013)

4.3 Ideas

The idea for the change is to improve the care, experiences and outcomes of refugees and asylum seekers through improved knowledge understand and training of the midwives caring for them. During the first year the book should be disseminated across Bristol trusts and their dependencies. This can be done electronically and via hard copy. A contact email for ownership of the document will be available for midwives using the document to communicate any known amendments or improvements they are aware of; this will provide version control of the service improvement being used.

4.4 Plan, Do, Study, Act (PDSA) cycle

Plan; Online documents are often seen as good tools to implement changes in practice. The NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement (2008) states to implement new changes in service delivery, it is important that pilot studies are undertaken. The document will provide a resources which can be easily updated, accessible and used over and over. When planning the Service Improvement, factors which will influence its success such as; professional’s awareness of the document, the format and layout of the document, the motivation of midwives to use the document, must be considered. Trust should promote the up coming document via the intranet and trust newsletters. Managers in trust dependency areas should deliver training on the book and discuss the use of it operation with their staff.

DO; When designing the document Trusts taking ownership must consider the use of focus groups, this should include specialists in the area of asylum, support services, midwives, and women who have received maternity care whilst in the asylum process. Thus ensuring the information within the book is up to date, relevant and useful. The document when finalised should be circulated around the focus group members for the purpose of editing and clarifying information and to ensure agreement on the final document. Inviting midwives to the participation of the design of the document will inspire them to feel ownership which will encourage the use of the document. This will improve the success of the implementation plan. Circulation of book should be done electronically and via hard copy allowing for easy and repeated use.

Study; six to twelve months after implementation of the document the focus group will need to come together to review it. This period of time will allow for the implementation of the document, its information and processes to be embedded into practice areas. After this time period analysis will occur. Staff involved in using the document will be invited to participate in the evaluation via questionnaires. Questionnaire’s are useful for evaluation of service improvement. The analysis of the questionnaire data would then be taken forward to an After Action Review (AAR) a tool used to facilitate assessments. The design focus group would come back together using the AAR tool to discuss the document, reflect upon how it has changed practice, evaluate the document, looking at how effective the document has been and if the document has led to positive changes making improvements in the service. (Cronin and Andrews, 2009).

Act; the next step is to continue to review the document on a regular basis to enable changes in practice and policy to be amended. The NHS institute for innovation and improvement (2008) states multiple cycles of the PDSA cycle are required to highlight adaptions which are profound after the first cycle. Providing further training to staff may be required, but this would be costly to the trust in terms of money and time.

4.5 Conclusion

In conclusion the experiences of pregnant women seeking asylum in the UK are poor. Midwives receive very little formal training in caring for this vulnerable group. Training is costly in money terms and time to NHS trusts. Midwives endeavour to provided women centred individualised care but find this challenging due to their lack of awareness of NHS entitlements, cultural training, personal beliefs and understanding. These experiences cause avoidance in interaction with maternity services resulting in poor outcomes and higher rates of morbidity and mortality. This service improvement plan was designed to meet the needs of midwives providing maternity care to pregnant women seeking asylum and also to improve the experiences of this vulnerable group of women. By considering the needs of the women and the Midwives caring for them holistically this document will improve the quality of the service provided and better equip the midwives to manage the service in an appropriate way.

References

Ali, N., Burchett, H., (2004). Experiences of Maternity Services: Muslim Women’s Perspectives. London: The Maternity Alliance.

Ameh, C. A. and van den Broek, N. (2008) Clinical governance- Increased risk of maternal death among ethic minority women in the UK. [online] Available from: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/store/10.1576/toag.10.3.177.27421/asset/toag.10.3.177.27421.pdf;jsessionid=2452CDA304E4E4CE9876CDB1CF31DF54.f02t02?v=1&t=izr46e7r&s=5ca94725e5acc2234f0050ed593aeb50d502d99f [accessed on 1 March 2017]

Anderson, C., (2010) Presenting and Evaluating Qualitative Research [online] Available from; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2987281/ [Accessed on 5 March 2017].

Aquino M.R.J.V., Edge, D., Smith, D.M. 2014. Pregnancy as an ideal time for intervention to address the complex needs of black and minority ethnic women: Views of British midwives. [Online] Available from; http://www.sciencedirect.com.ezproxy.uwe.ac.uk/science/article/pii/S0266613814002617 [Accessed on 1 April 2017]

Batalden, P. B., (2007) What is “quality improvement” and how can it transform healthcare? Quality & Safety in Health Care [Online] Available from; http://dd6lh4cz5h.search.serialssolutions.com/?ctx_ver=Z39.88-2004&ctx_enc=info%3Aofi%2Fenc%3AUTF-8&rfr_id=info%3Asid%2Fsummon.serialssolutions.com&rft_val_fmt=info%3Aofi%2Ffmt%3Akev%3Amtx%3Ajournal&rft.genre=article&rft.atitle=What+is+%22quality+improvement%22+and+how+can+it+transform+healthcare%3F&rft.jtitle=Quality+%26+Safety+in+Health+Care&rft.au=Paul+B+Batalden&rft.au=Frank+Davidoff&rft.date=2007-02-01&rft.pub=BMJ+Publishing+Group+LTD&rft.issn=1475-3898&rft.eissn=1475-3901&rft.volume=16&rft.issue=1&rft.spage=2&rft_id=info:doi/10.1136%2Fqshc.2006.022046&rft.externalDocID=4011420741¶mdict=en-UK [Accessed online 4th April 2017].

Bettany-Saltikov, J. (2012). How to do a systematic literature review in nursing: a step-by-step guide. Maidenhead: Open University Press.

Braun, V., Clarke, V. (2006) Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology 3 (2): 93.

Briscoe, L., Lavender, T., (2009) Exploring Maternity Care for Asylum Seekers. [online] Available from; http://www.magonlinelibrary.com/doi/citedby/10.12968/bjom.2009.17.1.37649 [Accessed on 28 March 2009

Bryman, A. (2012) Social Research Methods. 4th ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Burns, N., Grove, S.K. (2009) The practice of Nursing Research. Appraisal, Synthesis and Generation of Evidence. 6th ed. USA: Saunders Elsevier Ltd

Centre for Maternal and Child Enquires (CMACE) (2011), Saving Mothers’ Lives: Reviewing maternal deaths to make motherhood safer: 2006–2008.BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology, 118 pp. 1–203.

Cronin, G., Andrews, S. (2009) After Action Review: A model for learning. Emergency Nurse. 17 (3), pp 32-35. [Online] Available from; http://dd6lh4cz5h.search.serialssolutions.com/?ctx_ver=Z39.88-2004&ctx_enc=info%3Aofi%2Fenc%3AUTF-8&rfr_id=info%3Asid%2Fsummon.serialssolutions.com&rft_val_fmt=info%3Aofi%2Ffmt%3Akev%3Amtx%3Ajournal&rft.genre=article&rft.atitle=After+action+reviews%3A+a+new+model+for+learning&rft.jtitle=Emergency+nurse+%3A+the+journal+of+the+RCN+Accident+and+Emergency+Nursing+Association&rft.au=Cronin%2C+Gerard&rft.au=Andrews%2C+Steven&rft.date=2009-06-01&rft.issn=1354-5752&rft.eissn=2047-8984&rft.volume=17&rft.issue=3&rft.spage=32&rft_id=info%3Apmid%2F19552332&rft.externalDocID=19552332¶mdict=en-UK [Accessed 4th April 2017]

Department of Health, (2012). Health Profile. [Online]. Available from; http://www.apho.org.uk/resource/view.aspx?RID=117023 [accessed on 31 March 2017]

Feldman R (2012) When maternity doesn’t matter: Dispersing pregnant women seeking asylum. Available from:www.refugeecouncil.org.uk/assets/0002/6402/When_Maternity_Doesn_t_Matter_-_Ref_Council__Maternity_Action_report_Feb2013.pdf [Accessed 4 April 2017]

Gaudion, P., Allotey, P., (2008) Maternity care for asylum seekers and refugees in Hillingdon, [online] available from: http://www.thepolyannaproject.org.uk/documents/Needs_assessment_in_Hillingdon.pdf [Accessed on 2.3.2017

Gerrish, K, Chau, R, Sobowale, A, Birks, E, (2004) Bridging the language barrier: the use of interpreters in primary care nursing. Health Social Care Community 12(5): 407–13

Gov UK. (2015) Spending Review and Autumn Statement 2015. Available from; https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/spending-review-and-autumn-statement-2015-documents/spending-review-and-autumn-statement-2015 [Accessed on 4 April 2017]

Hadziabdic, E., Albin, B., Heikkila, K., Hjelm, K. (2010) Healthcare staff ’s perceptions of using interpreters. Primary Health Care Research & Development 11(3): 260–70

Hagens, V., Dobrow, M. J., & Chafe, R. (2009). Interviewee transcript review: assessing the impact on qualitative research. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 9, 47. doi:10.1186/1471-2288-9-47

Henderson, J., Gao, H., Renshaw, M. 2013. Experiencing maternity care: the care received and perceptions of women from different ethnic groups BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth. 2013 Vol 13, PP. 196.

Holloway, I., Wheeler, S., 2010. Quantitave research for nurses. Third edition. Wiley- Blackwell, Chichester

Horvat, L., Dell, H., Romios, P., Kis-Rigo, J. (2014). Cochrane database of systematic reviews: Cultural competence education for health professionals. [online] Available from;

Langley, G. J. (2009) The improvement guide: A practical approach to enhancing organizational performance [online] Available from; https://www.dawsonera.com/abstract/9780470430880 [Accessed on 4th April 2017]

Lyons SM, O’Keeffe FM, Clarke AT, Staines A. (2008) Cultural diversity in the Dublin maternity services: the experience of maternity service providers when caring for ethnic minority women. Ethnic Health. 2008; 13:261–276. [PubMed]

McLeod, S., (2014) Simple Psychology: Questionnaires. [online] Available from; https://www.simplypsychology.org/questionnaires.html [Accessed on 1 April 2017]

MAMTA (2017) CHILD & MATERNAL HEALTH PROGRAMME FOR BME WOMEN IN COVENTRY [Online] Available from; http://www.fwt.org.uk/www.fwt.org.uk [Accessed on 3 March 2017].

Moule, P., Goodman, M. (2014) Nursing Research: An Introduction. London: SAGE Publications Ltd.

MacFarlane A, Dzebisova Z, Karapish D, Kovacevic B, Ogbebor F, Okonkwo E (2009) Arranging and negotiating the use of informal interpreters in general practice consultations: Experiences of refugees and asylum seekers in the west of Ireland. Soc Sci Med 69(2): 210–4. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.04.022

Nakash, R., Hutton, J., Jorstad-Stein, E., Gates, S. and Lamb, S. (2006) Maximising Response to Postal Questionnaires – A systematic Review of Randomised Trials in Health Research. BMC Medical Research Methodology [online]. 6 (5). [Accessed 04 April 2016].

National Collaborating Centre for Women’s Health (2010). Pregnancy and complex social factors. [online] Available from;

http://www.ncc-wch.org.uk/guidelines/guidelines-programme/guidelines-programme-published/pregnant-women-complex-social-factors/ [Accessed on 1 April 2017]

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2010a) Pregnancy and Complex Social Factors: A model for service provision for pregnant women with complex social factors. Nice Clinical Guideline 110. www.nice.org.uk/cg110 [Accessed on 4 April 2017]

NHS Improvement (2012) First Steps towards Quality Improvement: A Simple Guide to Improving Services. Available From: http://www.nhsiq.nhs.uk/media/2591385/siguide.pdf [Accessed 03 April 2016].

NHS (2012) Friends and family Test: Implementation [Online} Available from; https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/213047/NHS-Friends-and-Family-Test-Implementation-Guidance-v2.pdf [Accessed on 6 April 2017

NHS institute for innovation and Improvement (2008) Quality and Service improvement tools: Plan, Study, Do, Act (PDSA). [Online] Available from: http://www.institute.nhs.uk/quality_and_service_improvement_tools/quality_and_serv [Accessed on 4th April 2017]

Nursing and Midwifery Council (2008) The Code for nurses and midwives. [online]. Available from: https://www.nmc.org.uk/standards/code/ [Accessed on 3 March 2017]

Nursing and Midwifery Council (2015) The Code. [online] Available from: https://www.nmc.org.uk/globalassets/sitedocuments/nmc-publications/nmc-code.pdf [Accessed 30 March 2017]

Novick. G, (2008) Is There a Bias Against Telephone Interviews in Qualitative Research? [Online] Available from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3238794/ [Accessed on 2 March 2017]

Office of National Statistics (2016) Asylum Seekers and Pregnancy. [Online] Available from; https://www.ons.gov.uk/aboutus/transparencyandgovernance/freedomofinformationfoi/asylumseekersandpregnancy, [Accessed on 1 March 2107]

Phelan, M., Parkman, S., (1995) How to work with an interpreter. BMJ; 311: 7004, 555-557

Philmore, J. (2015). Migrant maternity in an era of superdiversity: New migrants’ access to, and experience of, antenatal care in the West Midlands, UK. Social Science and Medicine 2016; Vol 148, PP 152-159.

Polit, D. F. and Beck, C. T. (2010) Essentials of Nursing Research. Seventh Edition: Appraising Evidence for Nursing Practice. London: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins

Polit, D.F., Hungler, P., (1997). Essential of Nursing Research Methods, Appraisals and Utilization (fourth edition) Lippincott: Philadelphia.

Rees, C. (2012) Introduction to Research for Midwives. Third Edition. London: Churchill Livingstone Elsevier

Reeves, S., Kuper, A., Hodges, B., (2008) Qualitative research methodologies: ethnography [online] available from; http://www.bmj.com/content/337/bmj.a1020 [accessed on 2.3.2017]

Squires, A., Methodological Challenges in Cross-Language Qualitative Research: A Research Review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2009, Vol 46, PP 227–287.

Sutton, J., Austin, Z., (2015) Qualitative Research: Data Collection, Analysis, and Management. [Online] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4485510/ [Accessed on 29 March 2017].

Temple, B., (2002) Crossed wires: Interpreters, Translators, and Bilingual Workers in Cross-Language Research. Qual Health Res. 2002; 12:844–854. doi: 10.1177/104973230201200610

Taylor, S.J., Bogdan, R. and DeVault, M.L. (2015) Introduction to Qualitative Research Methods: a guidebook and resource. 4th ed. New Jersey: John Wiley and Sons

The Health Foundation (2013) Measuring Patient experience. Available from; http://www.health.org.uk/sites/health/files/MeasuringPatientExperience.pdf [Accessed on 4th April 2017]

The Marmot Review. 2010. Fair Society. Healthy Lives. [online] Available from;

http://www.instituteofhealthequity.org/projects/fair-society-healthy-lives-the-marmot-review/fair-society-healthy-lives-full-report [Accessed on 1 April 2017]

The Refugee Council (2017) The Truth about Asylum. Available from: http://www.refugeecouncil.org.uk/policy_research/the_truth_about_asylum/the_facts_about_asylum [Accessed on 4th April 2017]

The Royal College of Midwives (2014) Databases [online] Available from;

https://www.rcm.org.uk/learning-and-career/learning-and-research/databases [Accessed on 3 March 2017]

The Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecology (2010) Pregnancy and complex social factors: A model for service provision for pregnant women with complex social factors. [Online] London: Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecology. Available from: http://www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/live/13167/50861/50861.pdf [Accessed on 4 April 2017].

The Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecology (2010) Pregnancy and complex social factors: A model for service provision for pregnant women with complex social factors. [Online]. Available from: http://www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/live/13167/50861/50861.pdf [Accessed on 1 March 2017].

Tobin, C., Murphy-Lawless, J., Beck, CT. (2013) Childbirth in exile: asylum seeking women’s experience of childbirth in Ireland. Volume 30, Issue 7, July 2014, Pages 831–838 Available from: http://www.sciencedirect.com.ezproxy.uwe.ac.uk/science/article/pii/S0266613813002179 [Accessed on 4 April 2017]

Tobin CL, Murphy-Lawless J. Irish midwives’ experiences of providing maternity care to non-Irish women seeking asylum. International Journal of Women’s Health. 2014;6:159-169.

Wood, M., Ross-Kerr, J., (2006). Basic steps in planning nursing research: from question to proposal. Sixth ED, Jones and Bartlett, Sudbury.

Zohrabi (2013). Mixed Method Research: Instruments, Validity, Reliability and Reporting Findings [online] Available from; http://www.academypublication.com/issues/past/tpls/vol03/02/06.pdf [Accessed on 5 March 2013]

Appendices

Appendix 1

Planning Mind Map.

Appendix 2

| Maternity | Experiences | Ethnic minorities |

| Midwife | Views | Asylum Seekers |

| Obstetric | Improvements | Refugees |

| Childbirth | Barriers | Non English speaking women |

| Birth | Obstacles | Migrants |

| Pregnant | Opinions | |

| Antenatal/ Postnatal | Feelings | |

| Post-partum | Judgements | |

| Labour | ||

| Labor | ||

| Childbearing |

Ovid Maternity and Infant Care, MEDLINE, The Cochrane Library and ASSIA:

CINAHL Plus- I searched the four first words in each category as it only allowed twelve in the advanced search function.

PsycInfo- originally same words as those searched in CINHAL but because no relevant research appeared, only ‘maternity’, ‘experiences’, ‘asylum seekers’ and refugees were used.

Appendix 3

| Authors | Three Dr’s all have PHD and are all associated with university lecturing in the nursing, midwifery and sociology field. Published in BMJ 2014, relevant to topic of interest. |

| Focus | Looking at the connection, communication and cultural understanding and how this impacts on the women’s health |

| Background | Poorly organised maternity services complicated by lack of training and cultural awareness have proved to have a detrimental effect on already vulnerable traumatised group of women. Implications for practice need to focus on how care providers can meet the needs of these women. |

| Aim | To gain an insight into women’s experiences of childbirth in Ireland while in the process of seeking asylum. |

| Methodology/approach | Qualitative in-depth unstructured interviews |

| Method of data analysis and presentation | Data was analysed using the Burkes dramatistic pentad to identify narrative agents |

| Tool of data collection | Women were invited to participate through attending information sessions and workshops held within their accommodation centres. |

| Sample | Purposive sample of 22 women who had experienced pregnancy and childbirth while seeking asylum or refuge in Ireland |

| Ethical considerations | Ethical approval was sought and gained emphasis was placed on voluntary participation due to the nature of the the study and interviewers were provided with an interpreter if required. |

| Main findings | The study found 3 main findings lack of connection, communication and cultural understanding was evident in all 22 participants. Communication and connection were barriers to adequate care this further impacted on the health and wellbeing of the women. Women were entirely reliant on interpreters and this proved to be a scares resource with restricted accessibility. The medicalised environment heightened the women’s sense of isolation, fear and vulnerability. Lack of cultural understanding and insight into the women had a detrimental effect on their mental health |

| Conclusions and recommendations | Poor organised care for asylum seeking women has thus far had a detrimental effect upon connection, communication and cultural awareness. Community based services with staff who have Training in cultural competency, access to interpreters and leaflets in various languages during the antenatal period will improve the access and services for this group. |

| Overall strengths and limitations |

Research is dependant on the skills of the researcher The volume of data and transcribing is time consuming Not always as well understood and quantitave research and not always as well accepted |

Cite This Work

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing stye below:

Related Services

View allRelated Content

All TagsContent relating to: "Midwifery"

Midwifery is a health profession concerned with the care of mothers and all stages of pregnancy, childbirth, and early postnatal period. Those that practice midwifery are called midwives.

Related Articles

DMCA / Removal Request

If you are the original writer of this dissertation and no longer wish to have your work published on the UKDiss.com website then please: