Differentiation in the Computing Classroom

Info: 9250 words (37 pages) Dissertation

Published: 28th Jan 2022

Abstract

If you ask the question, what is differentiation? The answers can be likened to how long is a piece of string. The term conjures up a variety of ideas. The new Computer Science GCSE is a rigorous qualification that provides challenge and stretch to students, to really allow them to succeed and become the countries next wave of professionals. This aside the government have found that it isn’t currently being taught to a consistently high standard. With many non-specialist teachers in computing and mixed ability classes, it is more important than ever that effective differentiation strategies are developed to ensure positive outcomes for each student.

This study explores the government, my placement school and teacher’s stance on differentiation, to reveal that teachers perceive the importance of differentiation, but that there is some confusion about how to implement it successfully. Student responses show that the current provision is only going part way to meeting the needs of all. After teachers analysed student responses they agreed to trial new strategies to meet the needs of their students. Therefore, this study proposes more CPD and more trialling and evaluation to ensure the governments ethos of ‘excellence for everyone’ is achieved (DfE, 2016).

Contents

Click to expand Contents

Introduction

Review of Literature

History of differentiation

Contemporary stance on differentiation

Government stance on differentiation

Models of differentiation and current ideas

Barriers to differentiation

Conclusion of literature review

Methodology

Research Methods

Interviews

Questionnaires

Observations and reflections

How will the results be analysed

Presentation and Analysis of Findings

What do teachers think about differentiation

Is the current differentiation provision working?

Objectives and outcomes

Differentiating content, process and product

Groupings

How can differentiation be improved?

Conclusion and Implications for Practice

References

Appendices

1 Teachers opinion on differentiation questionnaire graph

2 Teachers opinion group interview

3 Teachers strategy questionnaire graph

4 Student opinion questionnaire graph

5 Student reflection bar charts

6 Teacher observations

7 Hard copies of questionnaires

7 Hard copy of interview

Introduction

The government labelled the old ICT qualification ‘harmful’ and ‘boring’ and insisted on a ‘high-quality computing qualification’ to equip pupils to use ‘computational thinking and creativity to understand and change the world (DfE, 2013). AQA’s chief examiner Paul Varey explains students will now ‘need to demonstrate practical skills to pass’ it is no longer about “just knowing things, you have to do” (Guardian, 2015). In support of this Rob Leeman a computer science specialist from the OCR examination board, agrees that the qualification is more ‘rigorous and more challenging, with a bigger emphasis on problem solving’ (Crest, 2016). If the government’s goal of producing students with excellent computing skills is to be realised, then differentiation within the computing classroom is more important than ever before. The DfE requires all teachers to ‘Adapt teaching to respond to the strengths and needs of all pupils’ as set out in the teacher standards (DfE, 2011), and Although the House of Commons Science and Technology committee (2016) has credited the government for revamping the qualification to an excellent level, they have noted that ‘there is still some way to go for it to become truly embedded in all schools, let alone delivered to a consistently high standard’.

The purpose of this study is to explore what differentiation means, ascertain what teachers think about differentiation in the computer science classroom, find out if teachers know what the current government policy is on inclusion in the classroom and ascertain how teachers approach differentiation to cater for individuals. Additionally, this study aims to find out what students find helpful and if differentiation is working. Furthermore, this study aims to highlight what could be done further to ensure lessons stretch, challenge and support learning for each child to reach their full potential.

Literature review

Classroom practice has moved a long way from the ‘I teach you learn model’. Relatively new subjects such as computing, lend themselves to a more active style of teaching which ‘engages students in the learning process’ and requires students ‘to do meaningful learning activities and think about what they are doing’ (Bonwell & Eison,1991). Teachers no longer assume that just because they have taught a concept that all students in the class have learnt what was intended (O’Brien et.al, 2001).

History of differentiation

Differentiation in the classroom as we know it today was shaped and influenced by the views and findings of many educational psychologists. A review of the literature suggests that students are more likely to achieve their full potential when teaching is ‘responsive to their individual readiness levels (Vygotsky, 1978), ‘motivating’ and ‘enjoyable’ (Csikszentmihalyi, 1990), matches their learning modality in the shape of ‘thinking style’ (Bloom, 1956, de Bono, & Sternberg, 2003) or the way in which children make sense of information by their type of ‘intelligence’ (Gardner 1983). Additionally, Maslow’s hierarchy proposes that ‘Students need to feel emotionally and physically safe and accepted within the classroom to progress’ (McLeod, 2007). Furthermore, teachers need to ensure that every lesson begins at the student’s current level of understanding to build on their current knowledge and support them to reach their full potential. Vygotsky (1978) calls this distance between current knowledge and potential knowledge the zone of proximal development. Despite the age of these theories many of them are still applicable in the computing classroom.

Contemporary stance on differentiation

There are many proposed definitions to differentiation in the classroom. Differentiation can be described as ‘a set of strategies that will help teachers meet each child where they are when they enter class and move them forward as far as possible on their educational path. (Levy, 2008). These strategies are based on a student’s ‘ability, interest, and learning profile’. Teachers need to gather information on a student’s ‘readiness’, ‘interests’, and ‘learning preferences’ and apply this information to the ‘learning environment’, the method of ‘instruction’, and ‘type of as assessment’ for individual potential to be achieved (Tomlinson, 2003).

Government stance on differentiation

The government have interpreted the up to date literature on differentiation to produce the following National Curriculum statement: That ‘Teachers should set high expectations for every pupil. They should plan stretching work for pupils whose attainment is significantly above the expected standard’ and ‘have an even greater obligation to plan lessons for pupils who have low levels of prior attainment or come from disadvantaged backgrounds’ (DfE, 2013). The current ethos is that of ‘Educational Excellence Everywhere’, where ‘every child has access to high quality provision, achieving to the best of his or her ability regardless of location, prior attainment and background’. The government makes it clear that ‘outcomes matter more than methods, and that there is rarely one standardised solution, that will work in every classroom’ (DfE, 2016).

Models of differentiation and current ideas

Many models of differentiation have been developed, there is no prescribed way to differentiate and it ultimately depends upon the needs of individual students. Tomlinson (2003) identifies three elements of the curriculum that can be differentiated; content ‘what students need to learn’, process ‘the way in which content is taught’ and product which entails how students ‘demonstrate understanding’. Additionally, the environment of the classroom should be considered. Heacox (2002) believes a ‘supportive classroom environment is vital’ to ‘success in differentiating’. The computing environment often involves feeling safe to ‘make mistakes’ which involves encouraging a growth mindset (Dweck, 2007), without worrying about ‘suffering negative consequences’ (Brookfield, 1995).

Dweck’s growth mindset is based on the belief that individuals ‘can develop their intelligence over time’ (Dweck, 2007). This philosophy is often seen in Chinese classrooms where teachers believe that students are capable of learning anything provided that the presentation is correct. This idea is known as mastery and is based on the premise that ‘understanding is the result of high intention, sincere effort and intelligent execution, and that difficulty is pleasurable’ (The Guardian, 2015). Recent research on mastery supports the pedagogical practice of keeping the class working together on the same topic, whilst at the same time addressing the need for all pupils to master the curriculum and for some to gain greater depth of proficiency and understanding. Challenge is provided by going deeper rather than accelerating into new content (NCTEM, 2015).

Some teachers fear that differentiated instruction is unfair because of its allowance for different treatment for different students (Connor, Morrison, & Katch, 2004). Mastery tries to avoid this by having high expectations of all, with discreet support and rich extension and is designed to be carried out regardless of the ability of the group. (NCTEM, 2015).

Furthermore, grouping of students is an important differentiation strategy that raises much debate. Cohen et al (2004) found the children’s levels of enthusiasm and motivation increased when working in mixed ability groups. By removing the groupings in non-core lessons the children could learn from each other and teach one another simultaneously. In contrast Paton (2012) argued that using mixed ability grouping in any area of the curriculum will have a negative impact on the higher achievers as lessons are not tailored to suit their needs and progress will not be made. The mastery approach to variation of abilities within a school is approached by a ‘rising tide’ principle (Guardian, 2015). The mastery approach is based on whole class interactive teaching so that all students can ‘master concepts’ before moving forward ‘allowing no pupil to be left behind’. If a struggling student is identified then early intervention is carried out allowing the student to catch up for the next lesson. (NCTEM, 2015). This is especially relevant to computing as new skills are built on the foundation of prior knowledge. This area of differentiation is currently being carried out in mathematics classrooms but many of the principles could be applied to computer science as the new qualification has a significant amount of mathematical content, especially at key stage 4 (OCR, 2015).

Potential barriers to differentiation

Tomlinson discovered several barriers to success; ‘fear of faddism’, ‘lack of time’ and lack of ‘skill’ and ‘knowledge’ of differentiation (Tomlinson, 2003). Time is a recurrent theme throughout the literature. Corley worries that a significant amount of time and effort is required to ‘organise questions; and to design appropriate activities for each learner.’ Furthermore, students need to adapt to a new environment where the teacher shifts from being the ‘dispenser of knowledge to a facilitator of learning’ (Corley, 2005). This is especially apparent in a grammar school such as my placement school where teaching is traditionally didactic.

Conclusion to literature review

This literature review set out to explain differentiation, past, present and potential future. Whilst reviewing the literature it is clear that teachers are aware of differentiation but local and national policies don’t prescribe how to explicitly carry out strategies. There is a wealth of theory to refer to, however it can be contradictory in places. The purpose of this study is to find out how computer science teachers really feel about differentiation, ascertain if the current provisions are working and establish what more can be done.

Methodology

Research methods

The rationale for the methodology is to collect valid and reliable data to answer the key questions raised by the literature review. The methodology will provide an overview of the research approaches, the intended analysis of the results, selection of participants and potential limitations of the research (University of Southern California, 2017). The approach to this study is action based with the intention of improving teachers practice. The method involves a collection of quantitative and qualitative data collected via interviews, questionnaires and observations of key lessons.

Interview

Information will be gathered from a group interview with members of the computing team. The team is made up of one computer science specialist and four non-computer science specialists. The group of 5 teachers range in age and experience of both length of service and types of school. One of the staff members have master teacher status. The entire department was invited to the study to provide the broadest possible selection of participants.

Structured interviews ‘allow answers to be compared as they all ask the same questions, allowing easy analysis’. When ‘compared to questionnaires interviews provide greater depth’ (Research Gate, 2014).

Disadvantages include ‘time constraints when compared to questionnaires’ and ‘set questions disallowing other lines of enquiry, which may make it harder to obtain true data on people’s real opinions.’ Additionally, interviews may also be ‘prone to bias’ as the respondents may fear being judged and give the answer they believe are the most acceptable. Furthermore, the analysis of an interview can be very ‘time consuming as qualitative data is more difficult to transcribe and sift through’ (University of Portsmouth, 2010).

Questionnaires

On completion of the interview staff will be given a short questionnaire. These techniques combined aim to provide a cross section of viewpoints on what teachers think about differentiation in the classroom and a selection of commonly used strategies. Results will be analysed by the investigator by presenting them in bar charts to clearly illustrate the view of computing teachers.

Based on this primary analysis a second questionnaire will be designed to ascertain students preferred learning method, from the list provided by the staff investigation. The purpose of this is to find out if the current provision of differentiation is working. Questionnaires will be handed to all students in the GCSE, AS and A level classes, clarifying that the survey is conducted voluntarily and anonymously. A total of 24 in year 10, 7 in year 12 and 4 in year 13 will be asked, giving a sample size of 35. The chosen sample represents key stage 4 and 5 computing students. Key stage 3 students were omitted from this study as they are not currently studying computing.

Questionnaire responses are collected in a ‘standardised way’ so this tool is ‘more objective’. Results can be collected quickly and from a large group. However, as they are ‘standardised’ it may not be possible to ‘explain any points in the questions that participants might misinterpret’. Additionally, open-ended questions can generate large amounts of data that can take a long time to process and analyse. For this reason, I have chosen multiple-choice questionnaires. Furthermore, students may not ‘be willing to answer the questions’ due to a ‘lack of benefit’ or from fear of being ‘penalised’ for their real opinion (Evaluation cookbook, 1999).

Observations and reflections

Select lessons will be observed to find out how valid the teacher responses are to the initial interview and questionnaire. Further key observations will be carried out involving teachers trialling new strategies in response to the student questionnaires. Finally, students will be provided with a reflection plenary to ascertain their thoughts and feelings on the trialled strategies.

Observations can provide additional information that other evaluations do not offer. Interactions between the teacher and class gives light to the effectiveness of teaching methods. There is still however the disadvantage of bias that could invalidate the results just as with interviews stated above. The reliability of observations as an evaluative method may be influenced by the presence of the observer as both the teacher and the students may behave differently than in a non-observed situation resulting in distorted data (revise sociology, 2016).

How the results will be analysed

Once the data is collected the results will be analysed and interpreted. All data will be numbered and sequenced for easy reference. Common themes and opposing opinions will be highlighted from the interview. The data from the questionnaires will be turned into bar charts and legends will be added to make visualisation easier, so that the main findings can be verbalised. The student’s reflections will be converted into pie charts to show a traffic lighting of their responses (How to write guide, 2017).

Results and Analysis

Teachers opinions on differentiation

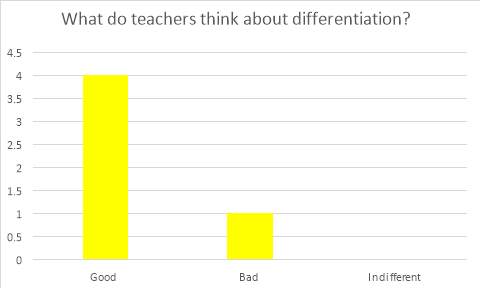

Four out of five teachers surveyed believed that differentiation was useful to help students achieve their potential(AP). It was difficult to find any positive data that correlated to this in the literature, however barriers to differentiation such as the ‘time needed to assess learners needs, interests, and readiness levels’ (Corley, 2005) were mentioned regularly. Although the teachers were positive about differentiation they didn’t all agree on the style of differentiation used(AP). This may be due to differing ideas of what the purpose of differentiation is, as there is no ‘one size fits all approach to differentiation’ (Anstee, 2014).

Teacher A mentioned Personalised learning (AP), a Labour initiative from the early 2000’s described as ‘individual learning styles, motivations, and needs’ (Milliband, 2004). Teacher C confused this with individualised learning where the teacher had a plan for every student within the class (AP). Differentiation differs as ‘it offers several avenues to learning, it does not assume a separate level for each learner’ (Tomlinson, 2001). Teacher D agreed with personalised learning where the content should be varied according to ability (differentiation by task). Teacher E disagreed, explaining they prefer to provide the same open ended task and differentiate by outcome providing support and extension where required (AP).

Within the small department there were several opinions on approaches to differentiation, all recognised from the literature, showing the huge breadth of approaches differentiation has. The whole group commented on how they concentrated on differentiation for observation lessons, more than every day lessons, due to time constraints (AP). This mirrors what Corley (2005) found in the literature above.

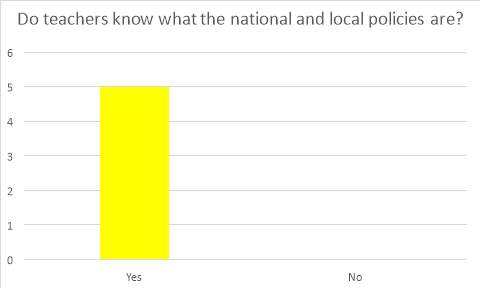

All teaching staff surveyed believed they knew what local and national policies are, however when questioned their elaborations were varied and sometimes contradictory which may affect the validity of this data(AP). Teacher A&C deliberated about personalised and individualised learning. Teacher E pointed out that neither of these were current policy. Individualised learning, ‘where pupils sit alone at a computer’, ‘often reinforced low aspirations’ and has not been a government policy for many years, (Milliband, 2004). Teacher E discussed how personalised learning didn’t work as they believed that you couldn’t personalise a lesson for each student and expect them to obtain their target (AP).

In support of this stance a secondary head commented on an Ofsted finding about lack of progress by students within his school. He stated that ‘exorable pressure of the curriculum’ and expectations of ‘league tables’ demand that ‘mainstream teachers drive forward in a way that may not be conducive to good inclusive practice’ (University of Cambridge, 2012). Teacher D stated that the outcome of differentiation was more important than the method (AP). They quoted the school policy of ensuring each student was seen as an individual, their curriculum personalised and lessons adapted according to individual need (KGGS, 2017) (AP).

All teachers agreed with teacher D’s interpretation. Despite deliberation among the department about the policies, they all affirmed that resulting success matters, in line with the government’s current policy ‘that outcomes matter more than methods, and that there is rarely one, standardised solution that will work in every classroom for the government to impose’(DfE, 2016). The government aren’t computing experts and therefore they leave differentiation choices to subject specialists.

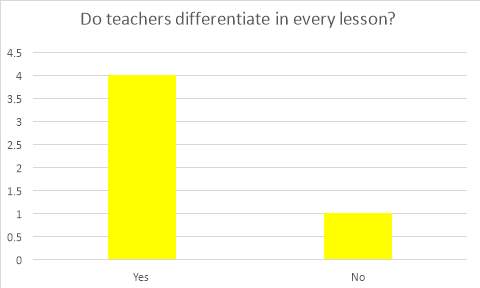

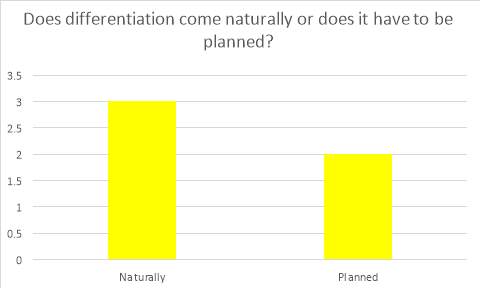

Is the current differentiation provision working?

Four out of five teachers stated that they differentiated in every lesson and three out of five stated that it came naturally and didn’t require planning (AP?&?). This is supported by observations carried out by the investigator who observed the use of a writing frame, allowing a student to use a fiddle toy to help with their concentration and deploying a TA to support a student with a statement(APobs). These are all examples of different routes to achieve the same goal, the improvement of outcomes. This is in line with governments proposal to allow teachers and leaders to use their own’ creativity, innovation, professional expertise and up-to-date evidence to drive up standards’ (Dfe, 2016).

Objectives and outcomes

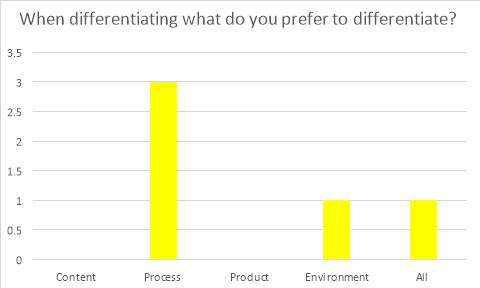

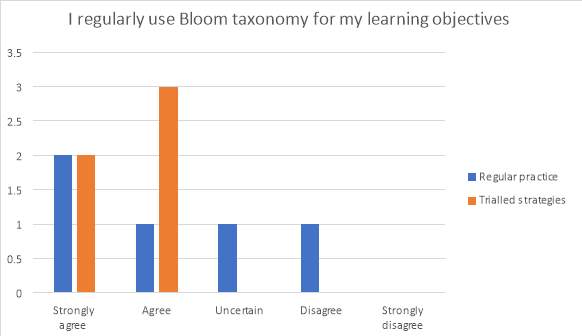

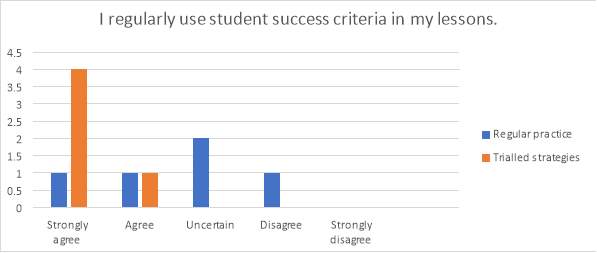

Within my placement school each department is allowed autonomy in line with the above policy. From observations, it can be confirmed that the government’s stance is proving to be somewhat effective as differentiation is occurring within the computing department (AP). The analysis of the questionnaires supports this by showing three out of five teachers prefer to differentiate the process of learning at the beginning of the study, three out of five regularly used blooms taxonomy and two out of five success criteria so ‘that the pupils know not only what they are intended to learn but also how they will demonstrate their achievement’ (DCSF, 2009) (AP). Teacher D was observed using writing frames, linked to a success criteria. The frame included Bruner’s idea of scaffolding as a form of sensitive interaction between teacher and student (TeachThought, 2017) (AP).

This allowed students to acquire new skills in their zone of proximal development by identifying where their current knowledge was and working towards the next criteria with the support of the teacher (Vygotsky, 1978). This demonstrates that some teachers within the department had excellent pedagogical knowledge suited to teaching computing, in line with the governments above statement about professional expertise and that they were applying up-to-date research (APobs).

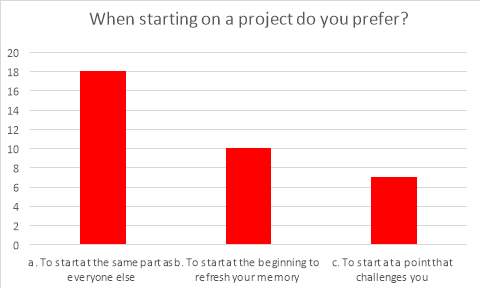

The student responses didn’t correlate with the teachers. When questioned 51% of students are used to starting at the same point as a class, typically the first learning objective (AP). Only 20% of students stated they like to start at a point that challenges them (AP). In contrast to the initial findings this is showing that the current use of learning objectives isn’t encouraging students to start at a point that challenges them. Measurable objectives are essential to the ‘ambitious new approach to teaching and learning computing’ (OCR, 2016) and this highlights a possible target for improvement.

On collection of the second teacher questionnaire all teachers are trialling the use of Blooms learning objectives and success criteria(AP). Although students weren’t asked specifically about this in their reflection the majority did state that they enjoyed the new style of lesson (AP).

Differentiating content, process and product

Four out of five teachers stated that they present lessons in a variety of ways with three out of five preferring to differentiate the process as mentioned above (AP ?&?). Three out of five teachers strongly agreed and two out of five agreed that they use tiered tasks (AP ?&?), additionally two out of five strongly agreed that they regularly use open ended tasks and two out of five agreed (AP). These occurrences are somewhat backed up by observations. During an observation of teacher B the investigator witnessed the use of a tiered task using a programming hierarchy based on blooms taxonomy(AP).

The skills required ranged from basic such as copying to coding and debugging. It was only when students were fully confident and able at the lower skills that they were able to apply creativity to create programming solutions. This strategy is supported by the literature as the tool ‘encourages higher-order thoughts in students by building up from lower-level cognitive skills’ (UCF Faculty Center for Teaching and Learning, 2017). Teacher D countered this by explaining curriculum time constraints prevented the regular use of such tasks, this is in line with the literature mentioned earlier (AP) (Corely, 2004).

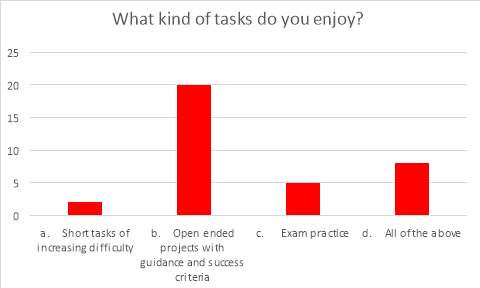

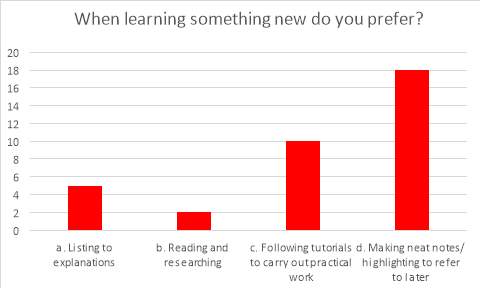

On questioning students confirmed they prefer open ended tasks with 57% stating it was a learning strategy they enjoyed(AP). Students confirmed they enjoy a variety of approaches to learning as when questioned 51% prefer making revision notes, 29% tutorials 14% listening to explanations to aide their practical work with only 6% preferring to read and research (AP). This is in line with the research as, mixed activities help with student engagement which is important as ‘Engagement in the classroom leads to achievement and contributes to students’ social and cognitive development (Finn, 1993).

On collection of the second teacher questionnaire all teachers are trialling a variety of strategies in their computing lessons(AP). This was confirmed as most students indicated the new lessons were presented in a different way(AP), in a way they wouldn’t have chosen for themselves and out of their comfort zone(AP). The majority of students would not have chosen to learn in this way or would not identify this process as a learning strength(AP).

This aside the majority of students engaged with and enjoyed this lesson (AP). There are mixed opinions in the literature to support and refute these findings. On one hand ‘responding to learning styles; and teaching to the student’s zone of proximal development’ provides ‘the foundation of differentiation’ and is based on ‘solid’ and ‘validated’ research (Allan & Tomlinson, 2000; Ellis & Worthington, 1994; Vygotsky, 1978). Further support is provided by Baumgartner, Lipowski, and Rush (2003) who found that a ‘students’ choice of learning tasks’ helped improve their ‘decoding, phonemic, and comprehension skills’.

However, Riener and Willingham (2010), classify differentiation by learning styles as a ‘myth’; They contend that there is ‘no credible evidence that learning styles exist’ and that ‘real harm may be done’ by ‘implementing instructional methods that we know do not work’. They acknowledge that ‘learners have preferences’ but when put to the test empirically under controlled conditions, these preferences have no effect in terms of the amount of material learned or the pace of learning’.

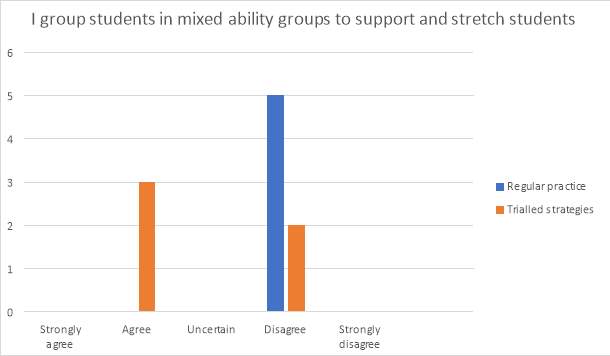

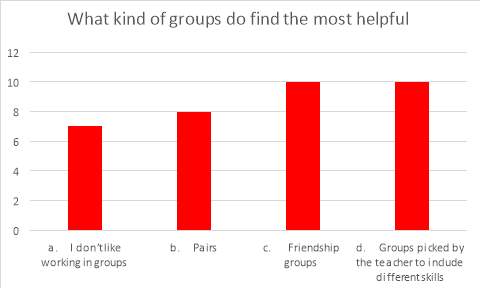

Groupings

None of teachers agreed with regularly grouping students in mixed ability groups (AP). The rationale for this was not due to disadvantaging the most able as was mentioned by Paton (2012) in the literature review. Teacher A’s rationale was based on the fact that Computer Science is an option subject and uptake is usually only one or two classes then the students are already of mixed ability(AP). The students’ opinions don’t correlate that of the teachers as 29% prefer it when teachers put them into mixed skilled groups (AP), 29% prefer to work in friendship groups 23% enjoy working in pairs, and only 20% don’t like working in groups. Baumgartner, Lipowski, and Rush (2003) found that ‘flexible grouping’ as preferred in the above findings may improve ‘student attitudes’.

Slavin (1987) found that ‘flexible within class grouping’ created ‘substantial achievement gains for able learners and nontrivial gains for average and struggling learners when instruction is tailored to students’ readiness levels. In support Tieso (2005) found that ‘creating purposeful flexible grouping, may significantly improve students’ mathematics achievement, especially for gifted students’. This especially relevant due to the amount of mathematics in the new Computing qualifications (OCR, 2015).

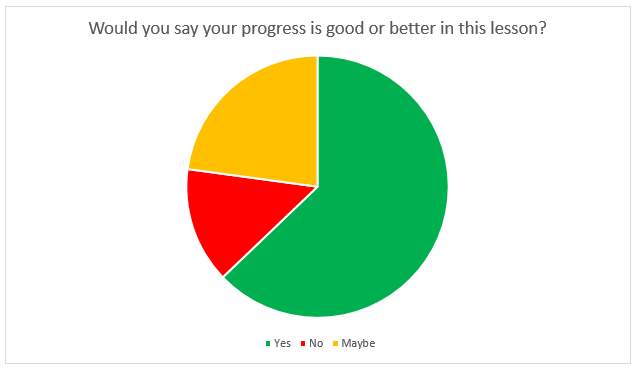

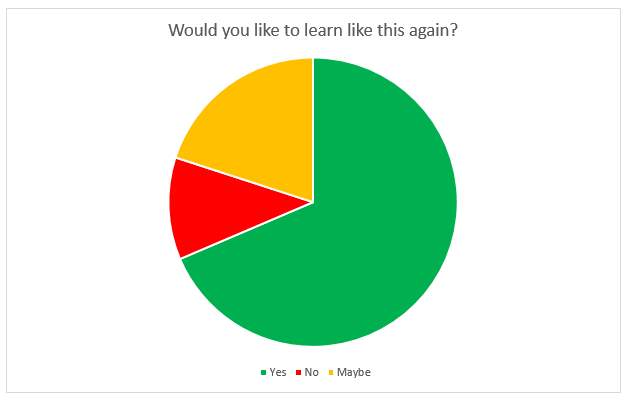

On collection of the second teacher questionnaire three out of five agreed to trial mixed ability groupings(AP). On reflection, most students believed they made good or better progress during the new groupings within lessons and would like to learn like this again(AP). Kulik & Kulik (1992) and Slavin (1987) noted that grouping practices alone will have small to moderate effects on achievement if they are not complemented with appropriate differentiation.

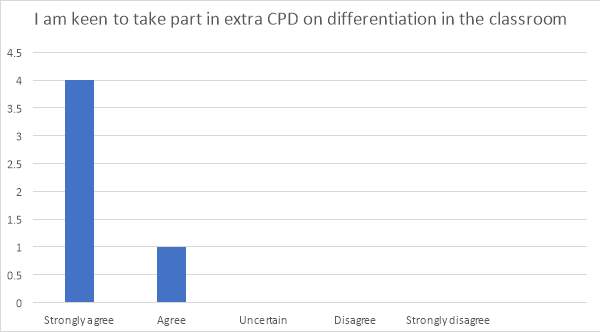

How can differentiation be improved

All teachers were keen to invest time in CPD with four out of five teachers strongly agreeing and one out of five agreeing (AP). The research shows that ‘In the UK the quality and nature of continuing training available is very uneven’ (OECD, 2017) and ‘schools in England may spend as little as 0.5% of their budgets on CPD’, according to the Teacher Development Trust (2010). In contrast, ‘in the world’s best school systems like Ontario, Canada, over 10% of school budgets and teacher time is spent on CPD learning’. Further research shows that ‘barely 1% of CPD training is improving classroom practice effectively in English schools’ (Teachers Development Trust, 2010). For CPD to be effective schools need to ensure the provision is specifically aimed at differentiation in computing.

This study has highlighted how students feel but not why. Further studies to ascertain why they opted for certain options or providing them with the opportunity to provide answers away from the unstructured questionnaire may provide greater insight.

Teachers in the computing department have already started to trial new strategies within their classrooms. Further trials with evaluation and reflection on their own lessons, from observers, from students, and analysing data could help establish consistent good practice.

Conclusion

Analysis of the data aimed to answer the key questions raised by the literature review. The study partly addressed the questions raised but that there are some improvements that would make this study more valid and reliable.

The teachers in this study believe that differentiation is a positive necessity to ensure all students meet their potential. There was some confusion about what the government and school expects in terms of strategies. There appeared to be a lack of confidence in how to apply differentiation. All teachers believed that further CPD would benefit them and their students.

From analysing the student questionnaire on what helped them to learn. It is apparent that the existing provision is only going part way to ensure each student reaches their potential. Once teachers had analysed these questionnaires for themselves they were able to identify what they could do to improve their differentiation provision. When the students were questioned a second time it was clear that the provision was improving as there was a majority positive response to each of the questions asked.

The government are keen to allow schools to be autonomous when implementing their own differentiation policies. Although some evidence of the raising of standards using ‘creativity, innovation and professional expertise’ was observed, the current picture was not consistent. The government are keen to avoid ‘the situation where, over the next five years, the strong get stronger and the weak fall even further behind’. The study recommends bespoke computing subject knowledge and differentiation training to improve confidence.

References

Allan, S. D., & Tomlinson, C. A. (2000). Leadership for differentiating schools and classrooms. Alexandria, VA: ASCD

Anstee, P., 2014. Differentiation Pocketbook. Management Pocketbooks

Baumgartner, T., Lipowski, M. B., & Rush, C. (2003). Increasing reading achievement of primary and middle school students through differentiated instruction (Master’s research). Available from Education Resources Information Center

Bonwell, C. and Eison, J., 1991. Active learning: Creating excitement in the classroom AEHE-ERIC higher education report No. 1.

Brookfield, S. D. (1995). Becoming a critically reflective teacher. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Cohen, L., Manion, L. and Morrison, K., 2004. A guide to teaching practice. Psychology Press

Connor, C.M., Morrison, F.J. and Katch, L.E., 2004. Beyond the reading wars: Exploring the effect of child-instruction interactions on growth in early reading. Scientific studies of reading, 8(4), pp.305-336.

Corley, M. (2005). Differentiated instruction: Adjusting to the needs of all learners. Focus on Basics: Connecting Research and Practice, 7(C), 13-16.

Crest. 2016. GCSE Reform: A New Dawn of Computer Science. [ONLINE] Available at: https://www.crest-approved.org/wp-content/uploads/CREST-GCSE-Reform-June-2016.pdf. [Accessed 14 May 2017].

Csikszentmihaly, M. (1990) Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience. New York: Harper & Row

Department for Children Schools Families. 2009. Personalised Learning – A Practical Guide. [ONLINE] Available at: https://www.essex.gov.uk/Business-Partners/Partners/Schools/One-to-one-tuition/Documents/Personalised%20Learning%20a%20practical%20guide.pdf. [Accessed 20 May 2017].

Department for education, 2011. Teachers’ standards – GOV.UK. [ONLINE] Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/teachers-standards. [Accessed 14 May 2017].

Department for education, 2013.National curriculum in England: computing programmes of study – GOV.UK. [ONLINE] Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/nationalcurriculum-in-england-computing-programmes-of-study/national-curriculum-in-england-computing-programmes-of-study. [Accessed 14 May 2017].

Department for education, 2013. National curriculum in England: mathematics programmes of study – GOV.UK. [ONLINE] Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/national-curriculumin-england-mathematics-programmes-of-study. [Accessed 14 May 2017].

Department for education, 2016. Educational excellence everywhere – GOV.UK. [ONLINE] Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/educational-excellence-everywhere. [Accessed 14 May 2017].

Dweck, C. S. (2008). The perils and promises of praise. Educational Leadership, 65, 34-39.

Ellis, E. S., & Worthington, L. A. (1994). Research synthesis on effective teaching principles and the design of quality tools for educators. University of Oregon, National Center to Improve the Tools of Educators.

Evaluation cookbook, (1999). Questionnaires: advantages and disadvantages. [ONLINE] Available at: http://www.icbl.hw.ac.uk/ltdi/cookbook/info_questionnaires/. [Accessed 14 May 2017]

Finn, J.D., 1993. School Engagement & Students at Risk.

Gardner, H. (1993). Frames of the mind: The theory of multiple intelligences. New York:  Basic Books

Basic Books

Heacox, D. (2002). Differentiating instruction in the regular classroom: How to reach and

teach all learners. Minneapolis, MN: Free Spirit Publishing.

Herzberg, F. (1959). The motivation to work NY: John Wiley.

House of Commons Science and Technology Committee, 2016. Digital skills crisis. [ONLINE] Available at: https://www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201617/cmselect/cmsctech/270/270.pdf. [Accessed 14 May 2017].

How to Write Guide: A Strategy for Writing Up Research Results. 2017. [ONLINE] Available at: http://abacus.bates.edu/~ganderso/biology/resources/writing/HTWstrategy.html. [Accessed 21 May 2017].

Kesteven & Grantham Girls’ School . [ONLINE] Available at: http://www.kestevengrantham.lincs.sch.uk/policies/. [Accessed 20 May 2017].

Kulik, C-L. C., & Kulik, J. A. (1982). Effects of ability grouping on secondary school students: A meta-analysis of evaluation findings. american Educational research Journal, 19, 414–428.

Maslow, A. (1962). Toward a Psychology of Being. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold.

Miliband, D. (2004) Personalised Learning: Building a New Relationship with Schools North of England Education Conference, Belfast. London: Department for Education and Skills.http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20130401151715/http://www.education.gov.uk/publications/eOrderingDownload/personalised-learning.pdf

National Centre for Excellence in Teaching Mathematics. 2015. Teaching for Mastery. [ONLINE] Available at: https://www.ncetm.org.uk/public/files/23305594/Mastery_Assessment_Y1_Low_Res.pdf. [Accessed 14 May 2017].

O’Brien, T. and Guiney, D., 2001. Differentiation in teaching and learning: Principles and practice. London: Continuum.

OCR. 2015. Computer Science. [ONLINE] Available at: http://www.ocr.org.uk/Images/225975-specification-accredited-gcse-computer-science-j276.pdf. [Accessed 21 May 2017].

OCR. 2016.Computing specification.[ONLINE] Available at: http://www.ocr.org.uk/Images/72936-specification.pdf. [Accessed 26 May 2017].

OECD Library. 2017. Initial Teacher Education and Continuing Training Policies in a Comparative Perspective – Papers. [ONLINE] Available at: http://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/education/initial-teacher-education-and-continuing-training-policies-in-a-comparative-perspective_5kmbphh7s47h-en. [Accessed 23 May 2017].

Paton G (2012) Ofsted: Mixed-Ability Classes ‘a curse’ on Bright Pupils. Available at http://www.telegraph.co.uk/education/educationnews/9553764/Ofsted-mixed-ability-classes-a-curse-on-brightpupils.html [Accessed 8th May2015].

ReviseSociology. 2016. Participant Observation in Social Research | ReviseSociology. [ONLINE] Available at: https://revisesociology.com/2016/03/31/participant-observation-strengths-limitations/. [Accessed 14 May 2017].

Riener, C., & Willingham, D. (2010). The myth of learning styles. Change: The Magazine of Higher Learning, 42(5)

Research Gate. 2014. Interviewing as a Data Collection Method: A Critical Review. [ONLINE] Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Hamza_Alshenqeeti/publication/269869369_Interviewing_as_a_Data_Collection_Method_A_Critical_Review/links/55d6ea6508aed6a199a4fd34/Interviewing-as-a-Data-Collection-Method-A-Critical-Review.pdf. [Accessed 14 May 2017].

Research Guides at University of Southern California. (2017) The Methodology – Organising Your Social Sciences Research Paper – Research Guides at University of Southern California. [ONLINE] Available at: http://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide/methodology. [Accessed 14 May 2017].

Sternberg, R. , & Williams, W. (2002). Educational psychology. Boston, MA: Allyn and Bacon.

TeachThought. 2017. Jerome Bruner On The Scaffolding Of Learning. [ONLINE] Available at: http://www.teachthought.com/learning/learning-theories-jerome-bruner-scaffolding-learning/. [Accessed 21 May 2017].

The Guardian, 2015. Gove determined to reform GCSEs from 2015 after baccalaureate retreat | Politics | The Guardian. [ONLINE] Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/education/2013/feb/07/gove-gcse-reforms-from-2015. [Accessed 14 May 2017]

Teacher Development Trust. 2010. What makes effective CPD? – Teacher Development Trust. [ONLINE] Available at: http://tdtrust.org/what-makes-effective-cpd-2. [Accessed 23 May 2017].

The Guardian. 2015. Differentiation is out. Mastery is the new classroom buzzword | Teacher Network | The Guardian. [ONLINE] Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/teacher-network/2015/oct/01/mastery-differentiation-new-classroom-buzzword. [Accessed 21 May 2017].

Tieso, C. (2005). The effects of grouping practices and curricular adjustments on achievement. Journal for the Education of the Gifted, 29(1), 60–89.

Tomlinson, C.A., 2001. How to diferentiate instruction in mixed-ability classrooms. ASCD.

Tomlinson, C. A. & Eidson, C. C. (2003). Diferentiation in practice: U resource guide for differentiating curriculum. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

UCF Faculty Center for Teaching and Learning. 2017. Bloom’s Taxonomy – UCF Faculty Center for Teaching and Learning. [ONLINE] Available at: http://www.fctl.ucf.edu/teachingandlearningresources/coursedesign/bloomstaxonomy/. [Accessed 21 May 2017].

University of Cambridge Faculty of Education. 2012. The Cost of Inclusion. [ONLINE] Available at: https://www.educ.cam.ac.uk/people/staff/galton/Costs_of_Inclusion_Final.pdf. [Accessed 20 May 2017].

University of Portsmouth, 2010. Advantages and Disadvantages of Different Types of Interview Structure. [ONLINE] Available at: http://compass.port.ac.uk/UoP/file/d8a7aedc-be56-461b 85e8ae38ccf49670/1/Interviews_IMSLRN.zip/page_03.htm. [Accessed 14 May 2017].

Vygotsky, L. (1978). Mind in Society The Development of Higher Psychological Processes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard

Walpole, S. , & McKenna, M. G. (2007). Differentiated reading instruction: Strategies for primary grades. NewYork: The Guilford Press.

Appendix

1a)

1b)

1c)

1d)

1e)

2)

3a)

The initial response to this question was mixed with 2/5 teachers strongly agreeing that they use Blooms taxonomy for their learning objectives. After reviewing the student questionnaires (below) all teachers appear to be trialling the above strategies with 3/5 agreeing.

3b)

The initial response to this question was mixed with 2/5 being uncertain whether they use success criteria in their lessons.

This highlights another possible target for improvement and after reviewing the student questionnaires it appears that all of the department are trialling this approach with 4/5 strongly agreeing to trial the approach.

3c)

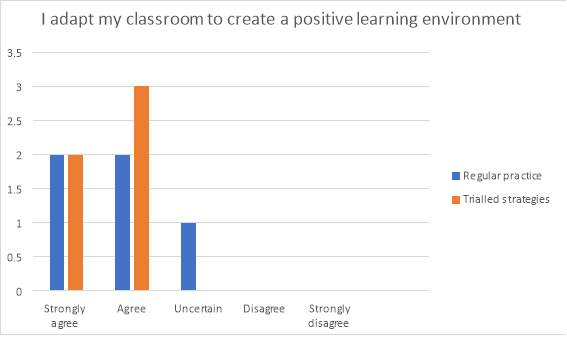

The initial response to this question was unanimous. On collection of the second set of questionnaires, after teachers had reviewed the student questionnaires (below) it appears that use of this approach was increasing with 3/5 teachers agreeing to trial this approach.

3d)

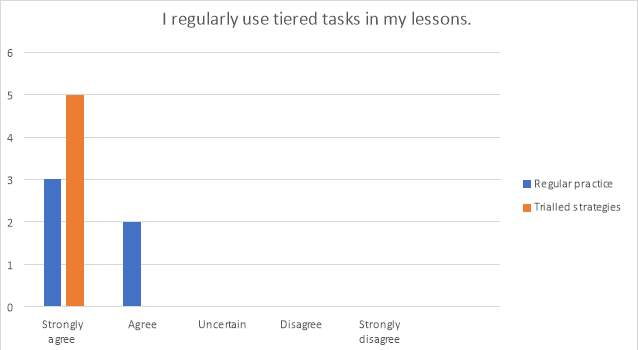

The initial response was positive to this strategy with 3/5 teachers strongly agreeing that they use tiered tasks in their lessons. On collection of the second set of questionnaires after teachers had reviewed the student questionnaires it appears 5/5 teachers strongly agreed to use open ended tasks.

3e)

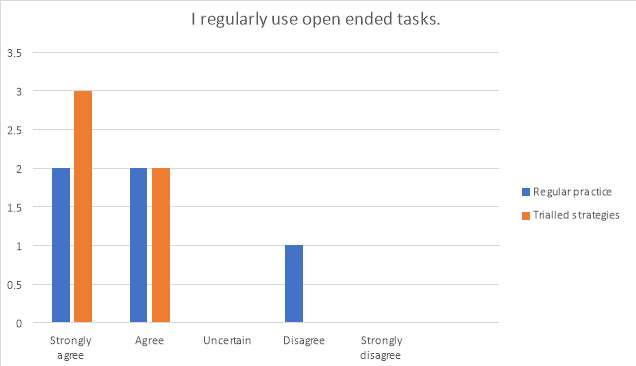

This question provided a mixed response. With 4/5 teacher strongly agreeing or agreeing that they regularly use open ended tasks. Upon receipt of the second set of questionnaires the uptake of open ended tasks appears to have improved with 3/5 strongly agreeing to it.

This question provided a mixed response. With 4/5 teacher strongly agreeing or agreeing that they regularly use open ended tasks. Upon receipt of the second set of questionnaires the uptake of open ended tasks appears to have improved with 3/5 strongly agreeing to it.

3f)

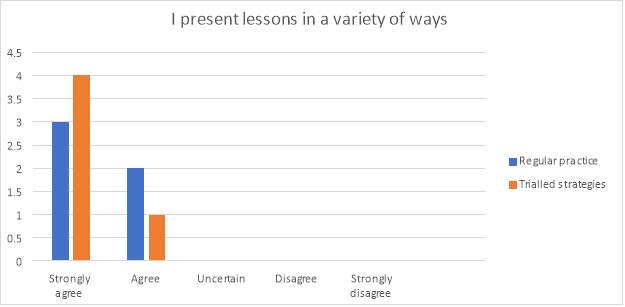

The original response to this question was strong with 3/5 teachers strongly agreeing that they present their lessons in a variety of ways. After receipt of the second set of questionnaires the uptake of this strategy appears to be even stronger with 4/5 teachers strongly agreeing.

The original response to this question was strong with 3/5 teachers strongly agreeing that they present their lessons in a variety of ways. After receipt of the second set of questionnaires the uptake of this strategy appears to be even stronger with 4/5 teachers strongly agreeing.

3g)

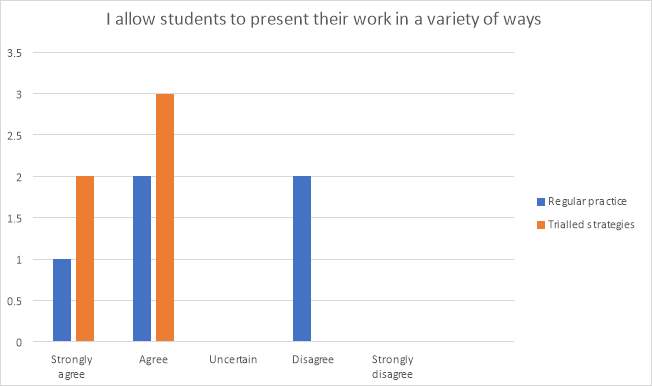

The initial response to this question was mixed with 2/5 agreeing and 2/5 disagreeing that they allow students to present their work in a variety of ways. Upon collection of the second set of questionnaires it appears all teachers are trialling this strategy with 3/5 teachers agreeing.

3h)

The initial response to this question was mixed with 4/5 teachers strongly agreeing or agreeing that they adapt their classroom to provide a positive learning environment. On collection of the second set of questionnaires all teachers appear to be trialling this strategy with 3/5 teachers agreeing.

2i)

All teachers were keen to invest time in CPD with 4/5 teachers strongly agreeing. This show that the staff care and want to be more knowledgeable about differentiation for the good of their students.

4a)

Although this question doesn’t ask specifically about learning objectives it shows that students are used to starting at the same point as a class, typically the first learning objective. Some teachers indicated that they are using learning objectives of increased difficulty using Bloom taxonomy. This response by students supports this as 7 students stated they like to start at a point that challenges them although the majority like to start at the same point as everyone else.

4b)

The majority of students highlighted that they prefer open ended project tasks that are tiered using a success criteria. Some teachers highlighted that they are already using success criteria and open ended tasks and this is supported by the above.

4c)

The majority of students indicated that they feel they learn more if they work in a group of either friends of a mixed ability group picked by the teacher. This was highlighted even though the teachers unanimously stated that they do not put students into mixed ability groups.

4d)

The response to this question is mixed showing that students enjoy the lessons when teachers allow them to approach a task in different ways. This supports the teachers questionnaire where some teachers stated they like to use a variety of ways to get students engaged. This aside the majority of student prefer to learn by being lectured and making and highlighting notes. I believe this is a grammer school trend (source) due to……

4e)

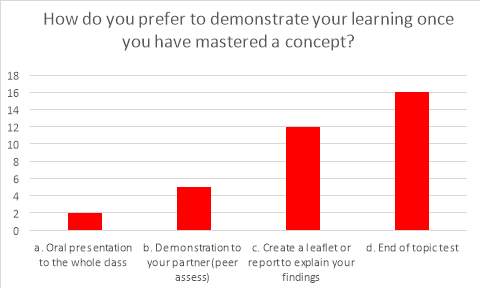

The response to this question was also mixed showing that students like the fact that some teachers allow them to show their learning in a variety of ways as stated in the teaching questionnaire. This aside the majority of students preferred to show their progress in an end of topic test showing the current culture of testing ?? (source)

4f)

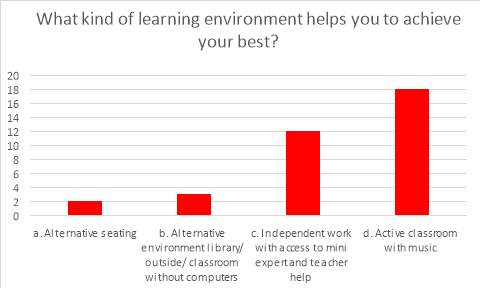

Some teachers indicated that they like to provide alternative environments within one classroom. The above showed that students appreciate this and enjoy a variety of environments with the majority enjoying an active classroom with music.

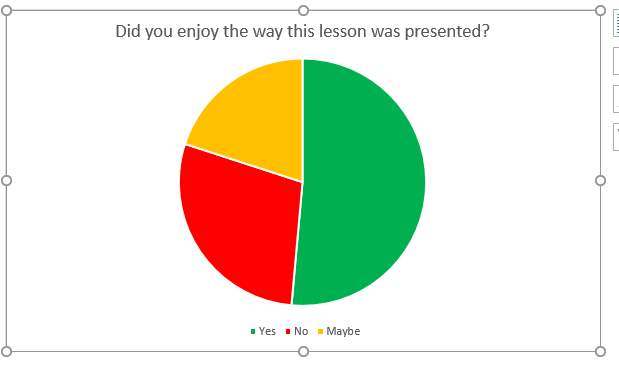

5a)

The majority of the students enjoyed the lessons where teachers were trialling new strategies. In hindsight, I believe I should have also conducted this survey before the change to allow me to compare my results to a baseline.

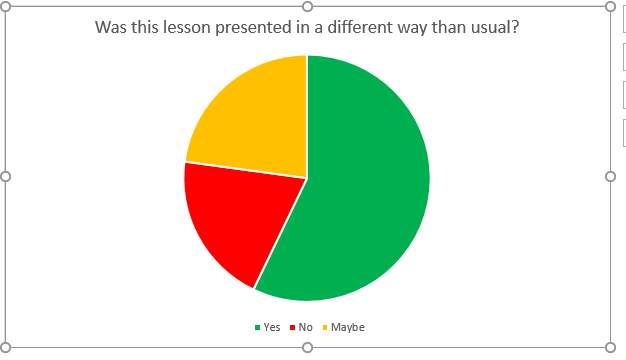

5b)

The majority of the students indicate that the lesson was presented in a different way than usual. This supports the teachers’ responses that they are trialling new strategies and that the proportion on no and maybe supports that some teachers were already carrying out a variety of differentiation before this study.

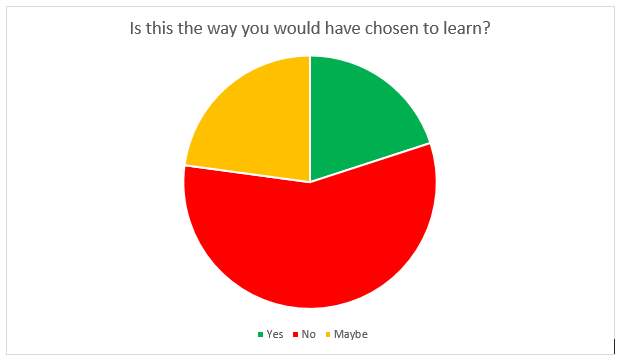

5c)

The majority of students would not have chosen to learn in this way or would not identify this process as a learning strength. This aside the majority of students engaged with and enjoyed this lesson (as shown above) This finding is supported by the theory that preferred learning styles are a myth (source) as the students enjoyed learning in a way that was not their usual choice.

5d)

The majority of students stated that this was out of their comfort zone, supporting the teachers’ statements that they vary the way the present the lesson and also how they ask students to present their learning. Carol Dweck theorised that having high expectations of students creates a growth mindset …. (source).

5e)

5f)

The large majority of students would like to learn like this again, this shows that a variation in strategies keeps the students engaged. However not all students agreed further research needs to be carried out to find out why some students would not like to learn like this again so that the teacher can ensure they are differentiating for all.

Cite This Work

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing stye below:

Related Services

View allRelated Content

All TagsContent relating to: "Computing"

Computing is a term that describes the use of computers to process information. Key aspects of Computing are hardware, software, and processing through algorithms.

Related Articles

DMCA / Removal Request

If you are the original writer of this dissertation and no longer wish to have your work published on the UKDiss.com website then please: