Effectiveness of e-Learning Programme for Leadership Skills

Info: 10251 words (41 pages) Dissertation

Published: 24th Nov 2021

Tagged: LeadershipLearning

1 Abstract

Despite huge growth in online learning offerings in the area of management development, leadership soft-skills development continues to take place predominantly in face-to-face learning environments. There is much bias against online leadership development, in higher education institutions, companies and business school accreditation bodies alike, not least because it is believed that soft-skills training requires face-to-face contact. Recent pedagogical and technological developments in e-learning are allowing for new and effective ways for leadership skills to be taught online, but to date, relatively few studies have measured the effectiveness of e-learning in leadership soft-skills in corporate contexts. The majority of e-learning research studies hard-skills training programs in secondary and tertiary education, and effectiveness is measured mainly terms of reactions or knowledge acquisition, rather than behaviour change – a crucial measure of effectiveness in organisational settings. This study therefore tests whether learning leadership skills online leads to positive behaviour change, and if so, what aspects of the programme design and delivery predict the learning transfer. The results point to an improvement in leadership behaviours pre- and post-programme, which correlates strongly with the extent to which participants applied their learnings in the workplace during the programme. This in turn correlated most strongly with participants’ perceived utility of the ‘active learning’ design, the programme content and structure, and the coach feedback and support. Results like this contribute to combat the bias against online learning for soft-skills, and to the development of effective online offerings in this domain.

2 Introduction

2.1 General Introduction

A recent empirical research report by the Chartered Management Institute (Scott-Jackson et al, 2015) showed that the vast majority of respondents – 80% of 1184 companies surveyed – prefer face-to-face (FTF) over e-learning (EL) courses for leadership-skills development. This bias against EL solutions for executive development also exists amongst management educators and accreditation bodies: accreditation and rankings institutions continue to use criteria which favour face-to-face instruction for EMBA rankings, and EL appears to be synonymous with lower quality (Redpath, 2012). A lack of awareness of the research, coupled with an insufficient number of people who have experienced EL in this domain may explain why negative perceptions remain (Redpath, 2012).

Research has repeatedly demonstrated that EL can be as good as, or, in some cases, better than FTF for achievement of learning objectives (Macgregor and Turner, 2009, Tang and Byrne, 2007), demonstrating that the two modes are very similar in effectiveness and are thus interchangeable (Bernard et al, 2004, Picolli, Ahmad and Ives, 2001; Abraham, 2002). Shachar and Neumann’s (2010) comparative meta-analysis with data from over 20’000 students in academic settings shows that, in 70% of cases, EL students’ academic performance was better than that of their classroom-based counterparts.

However, the majority of research to date explores technical or hard-skills training programmes, rather than soft-skills development. This may be because the bulk of research on the success of EL has focused on academic education, and less on executive development in workplace settings (Derouin, Fritzsche and Salas, 2005); the two contexts differ fundamentally in terms of learning outcomes and, as a result, the way in which effectiveness is measured.

Research into the effectiveness EL has evolved from focusing on technology as the enabler of new way of delivering content on-line, to comparing satisfaction and perceptions of the quality of EL with face-to-face classroom-learning (FTF) (Ladyshewsky and Taplin, 2014, Tang and Byrne, 2007). Academics are more recently turning their attention to the effectiveness of EL pedagogy in its own right. Pedagogical frameworks and approaches to EL began to emerge in 1990s. The research of pioneers such as Arbaugh and Adams in the area of executive leadership development is relatively recent around the turn of the millennium. The lack of awareness of the recent research that has been conducted in the domain of leadership soft-skills, coupled with a low number of people who have experienced EL may explain why negative perceptions remain (Redpath, 2012). The CMI research paper (Scott-Jackson et al, 2015) found that respondents felt that their organisations do not make good use of digital solutions in this area, suggesting that there may be a lack of viable e-learning solutions for soft-skills.

In terms of identifying what makes EL work, the definitions and measures for evaluating the success of EL programmes appear inconsistent and multifarious in the research. Literature reviews and meta-studies show that the pervasive definition of success for EL is satisfaction with the program or achievement of objectives (Shachar and Newman, 2010, Arbaugh et al, 2009). Very few studies investigate transfer of learning, crucial in executive development contexts. Further, the vast majority of effectiveness studies rely solely on self-reporting, known for being affected by many biases and distortions (Ford and Weissbein, 1997).

Added to this is the breadth and inconsistency of criteria chosen to measure the design and delivery factors of EL programmes, (Macgregor and Turner, 2009). Even when studies measure similar criteria, the operationalisation of those criteria differ widely, making it very difficult to compare studies and generate a common understanding of what makes EL work – let alone soft-skills EL – and ultimately, develop sound approaches to EL in the realm of executive development.

2.2 Statement of Purpose

Based on the need to counter the skepticism of the ability to learn leadership skills online, the dearth of testing of soft-skills EL programs, and the few examples linking effectiveness to pedagogical aspects in the field of executive education, the primary purpose of this research, therefore, is to assess whether a leadership soft-skills EL programme, designed in line with recent pedagogical theory, available to the public, can lead to a measurable improvement in observable leadership behaviours. The testing involves measuring training transfer, through multi-rater feedback as well as self-reports, rather than stopping at measuring satisfaction with the programme and self-reported behaviours. The second purpose of this research is to test the EL pedagogies of the programme (based on theory and research to date), and determine what key pedagogical dimensions of the EL programme contribute to this behaviour change, if any.

2.3 Definitions

E-learning is “the use of internet technologies to deliver a broad array of solutions that enhance knowledge and performance”, and is “networked; is delivered to the learner via a computer using conventional Internet technologies; and focuses on the broadest view of learning” (Rosenberg, 2001, in Macgregor and Turner, 2009, p.157).

Soft skills are defined by the Oxford Dictionaries online as: “Personal attributes that enable someone to interact effectively and harmoniously with other people” (https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/soft_skills), specifically, they are “a combination of intrapersonal skills (self-awareness, stress management, effective problem solving), interpersonal skills (communication, motivation and conflict management) and people management (empowerment, delegation, leadership and management)” (Whetten et al, 2000, cited in Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development, 2010, p.14).

3 Literature Review

3.1 Soft-Skills EL: A New Approach

The negative bias may be due to the perceived inadequacy of early EL design. Researchers are starting to turn their attention from technological and quality questions around EL to what pedagogical strategies can make EL effective (Baker, 2010). Morgan and Adams (2009) emphasise the need to put pedagogy before technology and to be very clear about the differences in pedagogical requirements between soft-skills and hard/technical-skills EL. They state that, in the realm of leadership development in particular, there are concerns around the quality of learning experiences and the failure to integrate theory with practice. The level of EL effectiveness is indeed a factor of pedagogical design, rather than of the technology deployed for delivery (Arbaugh and Benbunan-Fich, 2006).

A decade ago, Adams and Morgan (2007) made the distinction between “first and “second-generation e-learning” (p.162), describing principles which need to considered when designing different types of EL programmes. First-generation EL is best suited to hard-skills learning, and is technology-driven, linear-sequential and evaluation-based, engaging the learner primarily through visual means. Second-generation EL, on the other hand, is best suited for soft-skills development, and is pedagogy-driven, self-organised, self-assessment and reflection-based, and engages the learner primarily through ideas. These second-generation EL design-principles emerged from Adams’ and Morgan’s NewMindsets action-learning research project (2007).

Results of Arbaugh and Benbunan-Fich’s 2006 study shows that MBA “students reported significantly higher scores for perceived learning and delivery medium satisfaction on courses where objectivist teaching approaches were supported by the use of collaborative learning techniques” (p.435), concluding that online courses should be designed based on the ‘collaborative learning model’. Constructivists emphasize applying authentic tasks in a meaningful context rather than abstract instruction out of context, whereas objectivism’s assumption is that there is a single objective reality and that the goal of learning is to understand and assimilate that learning and is most appropriate for factual, technical or procedural knowledge (Liaw, 2001, in Arbaugh and Benbunan-Fich, 2006, p.436).

Furthermore, given EL typically takes place over longer time spans than FTF in the realm of executive education, it arguably provides the participant with more time to reflect on, apply and experience the learning in the workplace as soon as the knowledge is acquired, to obtain feedback and reflect and sense-make with peers, thereby create an ongoing action-learning loop for the duration of the programme which FTF instruction cannot, supporting the constructivist approach. Ladyshewsky and Taplin noted in their comparative study (2014) on EL leadership development training that performance scores amongst the fully EL participants was higher than those who attended the blended or F2F version of the programme, attributing this result to the fact that the EL design required participants to process the content, and “use this information to construct intelligent and responsive comments in the online discussion forums” (p.285), whereas in the classroom, the focus is on the instructor to deliver the concepts.

In 1996, Chickering and Ehrmann adapted the Seven Principles of Good Practice (Chickering and Gamson, 1987), a well-known constructivist pedagogical model for undergraduate education, to the EL environment, and stated that the technology in the EL context should be applied in a way that supports these principles (Chickering and Ehrmann, 1996) (see appendix).

Twenty years later, Arbaugh and Hornik (2006) tested these principles in online MBA programmes. They found that five principles correlated with perceived learning and satisfaction, concluding that they could be applied to EL contexts: ‘student-faculty contact’, ‘student reciprocity and collaboration’, ‘feedback’, ‘time on tasks’ and ‘high expectations’. The ‘active learning’ and ‘respect diverse talents’ principles did not correlate at all with perceived learning and satisfaction. The ‘active learning’ principle emphasizes the importance of using learning methods which encourage the participant to relate the materials to their own lives (Chickering and Ehrmann, 1996). In this study, ‘active learning’ was operationalised by the number of non-exam evaluations in the MBA programme – a questionable interpretation of this principle. This is one example of the criteria challenge existing in the research.

Subsequent research has supported these pedagogical principles. Macgregor and Turner’s literature review (2009) highlighted that peer interaction was a critical factor to include in the design of EL. Group learning involves interacting with peers, which in turn results in more learning because of specific mechanisms which affect cognitive processes, such as conflict resolution, internalization of explanations and “self-explanation effects” (Arbaugh and Benbunan-Fich, 2006, pp.436-437). Student-faculty contact, and the quality of their interaction, has also been show to impact perceived learning (Young, 2006, Arbaugh, 2010). Adams (2010a) strongly supports the ‘active learning’ principle to develop soft-skills and improve job-performance, stipulating that there are four different levels at which EL could be implemented, from EL as a “background resource” (level 1), through EL as part of a blended approach (level 2), to linking the EL with the participants’ learning objectives (level 3) and finally, to designing and delivering EL “tightly coupled with action learning projects” (p.51). Aside from Adams and Morgan’s work (2007, 2009), there do not appear to be many examples of EL soft-skills research in the literature.

Research has shown that further pedagogical factors need to be taken into account when designing, and measuring the effectiveness of learning. Kraiger, Ford and Salas (1993) identified three types of training input which can impact training transfer, notably ‘training design’, which includes the “job relevance of the content, the sequencing of the training material and the incorporation of learning principles” (pp.22-23). Wu (2016) applied a similar model for assessing the impact of professional EL, incorporating perceived quality and utility of design, finding that these items correlated highly with outcome behaviours. The two other elements the define are ‘trainee characteristics’ and ‘transfer climate’, which are also considered by Adams (2010b) to be important aspects to consider in the realm of EL soft-skills programmes.

Learning platform design was also found to influence the outcome of the EL experience (Picolli, Ahmad and Ives, 2001 and Lang and Costello, 2009). The platform design dimensions add to Chickering and Ehrmann’s seven principles (1987) by taking into account the unique environment in which the EL is happening, and should therefore be included in evaluating EL training.

Thus, there is a growing body of research into how EL in general, but also specifically in the realm of leadership soft-skills, ought to be delivered for best results – but, due to this newness, awareness and application are still modest.

3.2 Defining effectiveness: Reactions v. Learning Transfer

When evaluating executive development EL, and soft-skills in particular, we need to be clear first, about how effectiveness is being defined in the first place, and second, how the EL design and delivery factors are subsequently operationalised and measured, i.e. whether the criteria being used to evaluate the EL experience have face and internal validity – and indeed, are linked to the research conducted, and described above, for example. However, perhaps due to the complexity of the topic, the research into the effectiveness of EL appears to lack a consistent approach, to defining effectiveness and the criteria against which to measure it.

The question of how learning effectiveness is measured remains a contentious and tricky one. Organisations’ learning and development departments remain under pressure to demonstrate behaviour change and return on investment as a result of training efforts: Alliger, Tannenbaum, Bennett, Traver and Shotland (1997) stipulate that it is application to the job that, in most cases, defines training success for organisations. Nevertheless, most of the training evaluations performed by organisations focus on trainee reactions to the training rather than attempting to establish whether learning occurred and job performance improved (Goldstein and Ford, 2002). Despite the need to measure impact, it is most often participants’ reactions which influence the decision to continue delivering a training programme in an organisation (Goldstein and Ford, 2002, Morgan and Casper, 2000).

In their meta-analysis of training criteria, Alliger et al (1997) showed that affective reactions, or ‘liking’ of the training, the measure most widely used in organisations, barely correlated with transfer of learning. The transfer of learning can be defined by Kirkpatrick’s level 3 of evaluation, i.e. the degree to which “participants apply what they learned during the training when they are back on the job” (Kirkpatrick and Kirkpatrick, 2014). Utility reactions, or perceived usefulness of the training, correlated somewhat more (R=0.18) with transfer of learning (Alliger et al, 1997, p.349). Altogether then, it would appear that the decisions of organisations measuring training impact are based on largely irrelevant data (Morgan and Casper, 2000).

Several literature reviews show that evaluative research of EL has also tended to focus on Kirkpatrick’s (1996) levels one and two of training evaluation, i.e. student satisfaction and learning outcomes (Derouin et al, 2005, Shachar and Newman, 2010, Arbaugh et al, 2009). Macgregor and Turner (2009) explored research conducted to assess EL effectiveness, and, amongst the studies they cite, little mention is made of how the effectiveness of either the FTF or EL is defined and measured. Ford and Weissbein (1997) highlighted that without being specific on the dimensions of transfer, it is difficult to identify why design factors do or do not affect transfer (p.31).

Since this review, further studies evaluating the effectiveness of EL have been conducted, but again, focus on evaluating the quality of a programme without defining effectiveness, and rarely alluding to training transfer or behaviour change after the training. Evaluation of the training remains at Kirkpatrick’s (1996) level one and two, and relies on self-evaluation (Barnett and Mattox, 2010). Take the example of Arbaugh’s 2014 analysis of 48 studies of online MBAs, which measured outcomes such as course grades, perceived learning (self-reported) and satisfaction with the delivery medium, or Picolli et al’s (2001) effectiveness study measuring performance on the programme and satisfaction. According to results from Alliger et al’s (1997) research, these criteria cannot be said to significantly influence effective learning transfer.

Goldstein and Ford (2002) make a very clear recommendation in terms of the evaluation process, but which few studies appear to respect: instructional analysts should be seeking to establish whether job performance has improved, and to answer the following questions: “does an examination of the various criteria indicate that a change has occurred?” and “can the changes be attributed to the instructional program?” (p.141).

Research at Kirkpatrick’s (1996) evaluation levels three and four is sparse, no doubt due to the difficulty of measuring soft-skills behavior change and results in the organization. Derouin et al (2005) highlight that few studies have attempted to assess the effectiveness of online learning at the behaviour change level. They mention four studies/experiments, of which a large-scale survey conducted by Skillsoft (2004), which found that 87% of participants of online learning courses reported using their skills and knowledge (including soft-skills) back at the workplace, giving concrete examples of how the EL had affected their work.

A further example of where effectiveness has been measured at level 3 is Morgan and Adams (2009) action research project, in which they compared the results of a pre- and post-programme multi-rater survey to assess the change in participants’ skill-level after attending an in-company management development programme, and calculated the programme’s return on investment.

3.2.1 Self-Reports v. Multi-Rater Surveys

Although self-reports can be a reasonable way to measure learning transfer, Ford and Weissbein purport that one’s perception of transfer may be affected by “social desirability, cognitive dissonance and memory distortions” (1997, p.30), and encourage the use of multiple criterion measures to develop a richer picture of training transfer. The use of a post-programme multi-rater survey can be said to be more reliable that self-reporting alone.

Further, according to Alliger et al (1997), learning transfer ought to be measured sometime after the training, and be a measurable aspect of job-performance. The issue with measuring and comparing pre- and post-event criteria is that the results can be misleading, or in certain cases, difficult to understand and interpret, particularly when the person collecting the data is an outside consultant and is unaware of the processes occurring within the organization during and after training (Kraiger, Ford and Salas, 1993).

3.3 The Criterion Challenge

Responses to Goldstein and Ford’s (2002) second question, i.e. what design criteria lead to effectiveness of EL, remains very variable in terms of design, scope and magnitude (Shachar and Neumann, 2010). Defining and measuring the relevant design and delivery aspects of the EL experience remains a challenge, yet is critical for those responsible for learning and development, particularly given the ‘newness’ of the EL in executive development.

Adam’s (2010b) action research showed that taking a learner-centred approach to EL provided a positive behaviour change (self-assessed), however, there is no mention of whether that improvement was linked to the pedagogy itself, or indeed which pedagogical aspects it related to. Ladyshewsky and Taplin’s comparative study (2014) the effectiveness of a post-graduate, masters-level leadership development course, comparing FTF, blended and EL, did not attempt to find relationships between learning outcomes and the pedagogical aspects of the program.

The picture is further complicated with the breadth of criteria which affect the EL experience, satisfaction and outcomes. Macgregor and Turner (2009) highlight in their review the vast number of variables influencing effectiveness of EL, stating that few researchers factor these variables into their research. Examples include the participants’ level of comfort and ability with EL technology, the level of learner–control (the ability of the learner to learn at his/her own pace) (Macgregor and Turner, 2009), the learner’s work-place context and the levels of interaction between the student and the content (Zhang, 2005). Macgregor and Turner (2009) state that no valid e-learning effectiveness research has been conducted, as no study has yet tried to control for all the effectiveness variables found to date. Reliably measuring effectiveness and relating that to pedagogical design components of the programme remains complex.

4 Research Questions

The research questions are:

- Can learning transfer be demonstrated for a soft-skills leadership programme delivered in an EL environment?

- If so, which programme design and delivery dimensions predict the learning transfer?

The majority of studies have focused on measuring EL success at levels one and two of Kirkpatrick’s (1996) model, and rely on self-reported behaviours, generally falling short of measuring learning transfer in terms of behaviour change and application to the job, crucial in this context. Thus, for this research, effectiveness is defined at level 3 of Kirkpatrick’s (1996) model: learning transfer (on-the-job application and behavior change), and is measured by:

- Observable leadership behaviour change, using multi-rater feedback tool,

- The extent to which participants applied their learnings at work.

Although the application of learnings occurs during the training, it happens in the workplace, rather than in a classroom-setting, therefore can be said to correspond to Kirkpatrick’s (1996) level 3 ‘behaviour’, i.e. any behavioural change happening as a result of the training, rather than level 2 ‘learning’ (Alliger et al, 1997, p.345).

The second question explores the relationship between the programme effectiveness and participants’ reactions to the design and delivery criteria of the programme. In this research, the criteria have been chosen and measured based on theory and models to date, on which the design and delivery of the programme is based.

5 Research Method

5.1 Programme Description

This study is based on three runs of a leadership soft-skills online programme lasting eight weeks, targeted at executives, at a Swiss international business school.

Each week of the programme corresponds to a leadership soft-skills topic: self-awareness and state-management, leading individuals, leading teams, managing conflict, coaching skills and resilience. The programme design is based on pedagogical best practice and constructivist and collaborative pedagogy for EL soft-skills, encouraging implementing “authentic tasks in meaningful contexts” and “collaborative construction of knowledge with peers” (Arbaugh and Benbunan-Fich, 2006, p.438, Adams, 2010).

The programme is delivered on an open EdX platform. A learning manager oversees each run of the programme and manages the team of coaches. The programme is primarily asynchronous: faculty delivers content though a series of short videos each week, supplemented with readings. Participants complete approximately three assignments each week, individually, in pairs or in groups of three, in their own time, within a deadline. The coach interacts every week with up to 20 participants, providing individual feedback through two live conversations, in video and written format. The process for interacting with participants is the standardised, so the experience is the same for each participant. Details on the components of this programme are included in the appendix.

5.2 Research Instruments

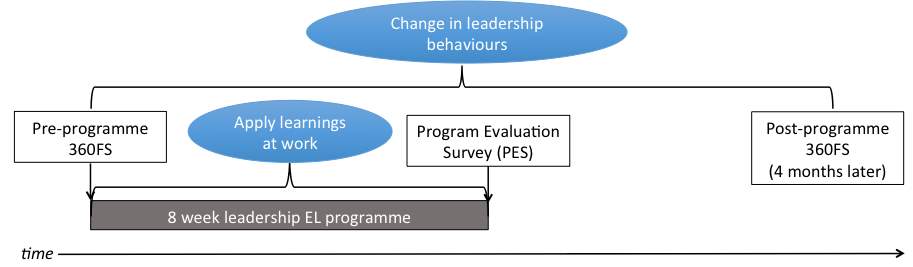

To measure the learning transfer and the pedagogical aspects of the programme, three sets of data were collected for each student, using the following instruments:

- A multi-rater feedback survey (360FS), completed before the programme started. Participants were required to obtain feedback from their manager, direct reports and peers/other colleagues on their leadership behaviours in the six topic domains of the programme. Respondents rate the participant’s behaviours on a five-point Likert scale (1: never, to 5: always).

- A programme evaluation survey (PES): on completion, participants were asked to rate their satisfaction with design and delivery dimensions of the programme, the extent to which they have applied their learnings in the workplace during the programme, and the extent to which they would recommend the programme to a friend, on a 5-point Likert scale (1: not at all, to 5: very much).

- A post-programme 360FS, identical to the pre-programme 360FS, administered four months after the end of the programme. The post-programme 360FS was offered to all participants, but remained optional.

5.2.1 Design and Validity of the 360FS

A multi-rater feedback tool was used, rather than a self-evaluation, as one’s perception of one’s own behaviour change may be affected by “social desirability”, “distortions of memory” and “cognitive dissonance” (Ford and Weissbein, 1997, p.30), hence the need to use behaviour-based multiple criteria, to obtain a more objective picture of the transfer of training.

The 360FS questions correspond to the theme and objectives of each unit of the programme, as recommended by Goldstein & Ford (2002). The internal consistency of each construct was tested and confirmed, with results showing high Cronbach’s Alpha for each leadership domain as follows: secure base leadership characteristics (nine questions): 0.807; leading others (five questions): 0.747; leading teams (five questions): 0.872; managing conflict (five questions): 0.828; leader as a coach (four questions): 0.901; resilience (four questions): 0.722. See appendix for the full questionnaire.

5.2.2 Design and validity of the Programme Evaluation Survey (PES)

The PES measures the dimensions on which the programme design and delivery was based. Thus, five of Chickering and Gamson’s (1987) principles found by Arbaugh and Hornick (2006) to be relevant for executive education are measured. These are supplemented by measures of programme content and learning platform, which, as previously discussed, have been found to influence the outcome of the EL experience (Kraiger et al, 1993; Piccoli et al, 2001; Lang and Costello, 2009; Rodrigues and Armellini, 2013). Thus, the dimensions measured were:

Coach Support and Feedback

Online tutoring is recognised as a critical success factor in EL-acceptance amongst learners (McPherson and Nunes, 2004), with explanatory feedback being a crucial element (Arbaugh, 2010). Promptness of feedback after assignment submission has also been found to be important to learners (Young, 2006).

Research has shown that instructor presence and interaction with students are important factors for success of EL (Arbaugh, 2010; Young, 2006; Blignault and Trollip, 2003; Baker, 2010). In this programme, as faculty is not present in person, we consider the ‘faculty’ to be the coaches, who interact with participants individually throughout the eight-week programme. Hence, I have combined Chickering and Gamson’s (1987) ‘student-faculty contact’ and ‘feedback’ principles, and labelled the new dimension ‘coach support and feedback’.

Student Reciprocity and Cooperation

Chickering and Gamson (1987) emphasise that participants should interact, collaborate, share and respond to each other, leading to a deeper understanding of the content. Again, studies have shown that students are more satisfied with online learning programs when the level of interaction with others is high (Blignault and Trollip, 2003). Participants on this programme interacted with each other in part in portal discussion forums.

Active Learning

This principle (Chickering and Gamson, 1987) emphasizes the importance of using methods enabling the participant to relate the material to their own lives, rather than rely solely on passive methods of learning. Adam’s Four Level Model for integrating work and e-learning (2010a) develops this principle further, describing level four of the model as closely tieing EL with action-learning projects. Although Arbaugh and Hornick (2006) did not find that this dimension correlated with satisfaction, their operationalisation of this dimension is not applicable in this context, so it has been included.

Time on Tasks

The amount of time spent on tasks in EL has been shown to affect the performance of participants (Wu, 2016), and participants were asked to estimate how much time they spent each week on the programme.

High Expectations

According to Chickering and Gamson (1987), setting high expectations for participants encourages them to put more effort into their learning. Applicants, and their organisations, are informed that certification, and therefore, alumni status with the school, is granted only on completion of all programme assignments. This principle has been operationalised by asking participants to rate the importance of obtaining certification and alumni status.

Programme Content and Structure

Morgan and Adams (2009) and Kraiger et al (1993) identified the relevance and usefulness of training content to influence learning effectiveness. Participants’ interaction with EL content has been found to affect outcome behaviours and perceived learning (Wu, 2016, Rodriguez and Armellini, 2013). Thus this dimension was included in the PES.

Satisfaction with the learning environment/platform

Research shows that if students are not satisfied with their EL experience, “they could opt out of the online courses or transfer to another institution” (Arbaugh and Benbunan-Fich, 2006, p.444). On the other hand, whilst Arbaugh (2014) later found that the experience with the learning platform predicted satisfaction, it did not predict learning outcomes. Given the mixed evidence, this dimension was included in the research.

Chickering and Gamson’s (1987) principle ‘Respect Diverse Talents and Ways of Learning’ was not included in the PES. Arbaugh and Hornik (2006) operationalised this dimension with measures reflecting the variety of learning tools, techniques and formats on the program, and found no correlation with perceived student learning. This principle suggests that the programme design should incorporate a range of learning experiences, (case studies, group work and individual work), items measured in the ‘active learning’ dimension. For these reasons, this principle was not separately measured in the evaluation.

The PES dimensions and the questions operationalising them are summarised in the table below: questions were inspired by Ehrmann and Zuniga’s Flashlight Project (1997), adjusted to reflect the context of the executive education sector. Following Alliger et al’s (1997) findings, the questions are worded to measure ‘utility’.

| Dimensions | Survey Questions: |

| Coach support and feedback

4 items Cronbach’s alpha=0.822 |

|

| Student reciprocity & cooperation

1 item |

|

| Active learning

5 items Cronbach’s alpha=0.715 |

|

| Time on tasks

1 item |

|

| High expectations

2 items Cronbach’s alpha=0.911 |

|

| Programme content & structure

5 items Cronbach’s alpha=0.715 |

|

| Learning platform

2 items Cronbach’s alpha=0.864 |

|

Participants were also asked to rate:

- The extent to which they applied the learning at work, and to list three things they are doing differently at work as a result of attending the programme.

- the likelihood that they would recommend the programme to a friend; this measures ‘overall satisfaction’.

The table below illustrates over time when the instruments were administered and the time frames for the ‘behaviour change’ and ‘application of learning’ measures:

Conger and Toegel (2002) advise against aggregating multi-rater information as this can create inaccuracies or hide valuable information in specific respondent groups. Such an approach is also relevant for the purposes of evaluating behaviours before and after the programme. Thus, the test results were split to reveal the ratings from participants’ direct reports and managers.

In the ‘manager’ rater-group, the overall increase in leadership behaviour ratings was .18, slightly lower than the overall mean increase of 0.19. The greatest, and statistically significant, pre-post programme means increases in this rater-group were in the areas of ‘managing conflicts’ (0.32) and ‘leading teams’ (0.21). Mean differences in the areas of ‘leading others’, ‘leader as a coach’ and ‘resilience’ were not statistically significant.

The ‘direct reports’ group results showed that the largest statistically significant (p<.01 pre-post-programme means differences were in the areas of others at teams and as a coach overall increase leadership behaviour ratings was slightly higher than mean results for conflicts not statistically significant.>

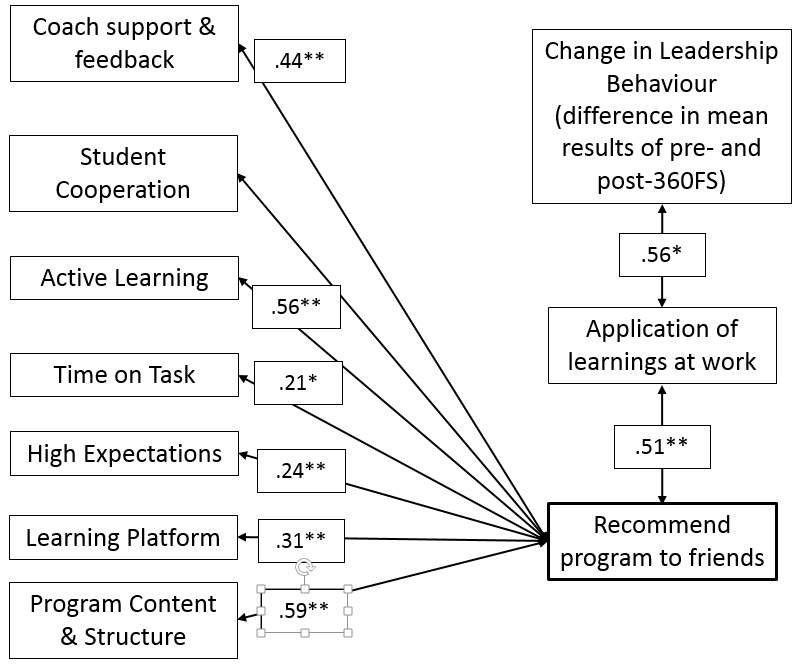

The extent to which participants applied their learning at work yielded a mean rating of 4.14 on a Likert scale of one (not at all) to five (very much). There was a strong and statistically significant correlation (.56) between the ‘change in leadership behaviour’ and ‘applied learnings at work’. They are both related to Kirkpatrick’s (1996) level 3 of learning effectiveness (‘behaviour’), but take place over different time spans and are measured differently: one is self-reported, and proximal in time to the programme, the other is multi-rated and distal in time to the programme.

6.2 Research Question 2

6.3 Overall Satisfaction with the Programme

The correlation matrix showed the following relationships between overall satisfaction, measured by the extent to which participants would recommend the programme to friends, and the remaining dimensions in the PES:

Legend:

**p

The pattern of relationships is similar to those found between ‘applied learnings at work’ and the seven dimensions, and generally stronger. The strongest (over 0.5) correlations are with the ‘programme content & structure’ (0.59), consistent with Rodrigues and Armeilli’s (2013) research in a corporate setting, which showed that learners valued their interaction with content the most. The next largest correlations are with Active Learning (0.56) and, notably, with ‘applied learnings at work’ (0.51).

Moderate correlations appeared with ‘coach support and feedback’ (.45). Lower correlations appeared with ‘time on task’ and ‘high expectations’. There was a significant relationship between general satisfaction and the learning platform (.31), which is in consistent with Arbaugh’s (2014) findings. There was no correlation with either ‘student cooperation’ or the ‘change in leadership behaviour’. The lack of relationship between overall satisfaction and change in behaviours supports findings in the literature that satisfaction measures do not predict behaviour change (Alliger et al, 1997).

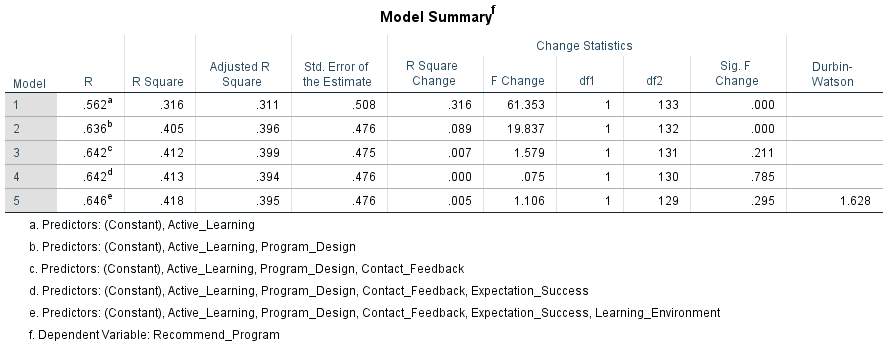

A hierarchical multiple regression analysis was conducted to ascertain what proportion of the variance in ‘recommend programme to friends’ was due to the independent variables program content, active leaning, coach support and feedback, high expectations and learning platform. See Table 2 for full details on each regression model. There was linearity as assessed by partial regression plots and a plot of studentized residuals, as assessed by a Durbin-Watson statistic of 1.628. There was no evidence of multicollinearity, as assessed by tolerance values greater than 0.1. The second model for ‘active learning’ and ‘programme content and structure’ statistically significantly predicted ‘applying learnings at work’, R2=.405, adjusted R2=.396, a strong size effect according to Cohen (1988), F (1, 132) =19.837, p

Table 2: Hierarchical Regression Analsyses of Overall Satisfaction

7 Analysis and Discussion

7.1 Leadership soft-skills can be learned online

The first research question was whether learning transfer, in terms of application at work and behaviour change, could be demonstrated for a soft-skills leadership programme delivered entirely on-line. The results show a statistically significant and moderate improvement in the leadership skills of participants pre- and post-programme, as measured by a multi-rater survey, evidence that leadership soft-skills can be effectively learned in an entirely EL environment, hopefully serving to contribute against the negative bias towards online executive development. Defining and measuring effectiveness in terms of learning transfer, rather than reaction to the training, skills and knowledge acquisition or assessment of quality, and using data not only from self-reports but from multi-rater surveys – a method rarely used in practice or research despite ‘learning transfer’ being paramount for organisations to demonstrate – further contributes to the literature.

Results showed that this improvement in leadership behaviours had a strong relationship with the other measure of learning transfer: the degree to which the participant applied his/her learnings at work during the programme. Whilst this result may seem obvious, it is an important finding for EL: as a mode of training delivery, EL is unique in that content is delivered over a longer time-period than classic F2F training, synchronously with work, providing participants with the opportunity to try new behaviours at work, which these results show is linked with observable behaviour change four months post-programme.

7.2 ‘Active learning’ and ‘program content and structure’ predict learning transfer

The lack of statistically significant correlations between the ‘change in leadership behaviours’ and the PES dimensions might due to ‘change leadership behaviours’ being distal to the programme. There were, however, several significant relationships between ‘applied learnings at work’ and the PES dimensions, and the results of hierarchical multiple regression analysis suggest that the key EL design dimensions which predict the extent to which participants apply their learnings at work are ‘active learning’ and ‘programme content and structure’. ‘Active learning’ measures the usefulness of the individual, buddy and group assignments, and reflection journals, which are designed specifically to give participants opportunities to reflect and apply the concepts and models to their work context throughout the programme. Higher levels of interaction with the content have been shown to allow for greater learner flexibility and control over their learning experience, making learners more likely to engage with the content at a deeper level (Macgregor and Turner, 2009, p.160). The results show the importance of designing the programme to provide participants with structures for reflection and application, encouraging them to transfer the learnings to the workplace, and ultimately, change their behaviours.

The relationships found in this program between ‘active learning’, ‘application of learnings at work’ and ‘change in leadership behaviours’ provide quantitative support for Adam’s (2010a) Four Level Model for soft-skills EL. She provides an in-company example of how designing a leadership soft-skills EL program at ‘level four’ of her model, designed to integrate action-learning projects in the workplace, gave participants the opportunity to apply the learnings to their workplace situations; subsequently behaviours of participants beyond the EL program changed, creating a significant ROI for the company.

‘Programme content and structure’, i.e. the usefulness of the content and structure for the participants’ learning and professional development, was the other predictor of learning transfer. This result is consistent with several studies: Kraiger et al (1993) found that training design (i.e. the job-relevance of the content and the sequencing of the training material, measures included the PES) impacted learning effectiveness, Wu (2016) found a relationship between the quality of EL content design and outcome behaviours of participants in a corporate setting, and Zhang’s (2005) research showed that students who experienced high levels of interaction with content also reported greater satisfaction and improved their learning performance.

The effect size of the correlations, and the regression analyses results suggest that resources ought to be directed primarily towards the quality, relevance and flow of the content, and the programme assignments.

7.3 Dimension not predicting learning transfer

Although ‘coach support and feedback’ correlated with ‘application of learnings at work’, and with overall programme satisfaction, it did not emerge as a predictor variable for either. This finding was surprising, given that feedback is a crucial component of and supports the “learning accountability loops” which “enable tight integration of work and learning” (Adams, 2010a), and that student-faculty interaction has been highlighted by a number of studies as a critical factor in supporting participants’ learning (Morgan and Adams, 2009, MacPherson and Nunes, 2004). Arbaugh et al’s (2009) study of 46 MBA programmes showed that “immediacy behaviours” (p.1234) accounted for 6% of the variance in perceived learning – using no less than 22 questions to measure instructor immediacy and teaching presence.

The result in this study is, however, consistent with Rodrigues and Armellini’s (2013) research that showed no relationship between online interactions – whether between the learner and the faculty or amongst learners – and the effectiveness of the programme – participants valued their interaction with the content above all else. Wise, Chang, Duffy and Del Valle (2004) also showed that tutors’ social presence affected perceptions of the instructor, but not perceived learning. This finding is worth exploring further, and perhaps linking the perceived value of support and feedback with learner characteristics – self-efficacy and internal locus of control, for example – given that employing qualified and trained coaches to support participants throughout their eight-week EL journey is a considerable variable cost for the school.

The fact that ‘student cooperation’ did not correlate with application of learnings or with general satisfaction was also unexpected, although again, is consistent with Rodriguez and Armellini’s research (2013). Given that ‘active learning’ predicted application of learnings, one interpretation is that the cooperation happening for the buddy and group assignments is sufficient to enhance learning transfer, rendering further interaction superfluous. Benbunan-Fich, Hilz and Turoff (2003) showed that participation in online group-work specifically results in superior performance than in face-to-face grou-work, because of the ability for participants to clarify, explain and give feedback, mechanisms that positively affect cognition. Thus, practitioners need to be attentive to the structures they choose to encourage student collaboration and reciprocity. Moderating participant discussion forums is a time-consuming activity for learning managers, and this study suggests it may not be necessary to encourage transfer of learning.

‘Learning platform’ correlated moderately with overall satisfaction, and to a far lesser degree with application of learnings. This result partly echoes Arbaugh’s (2014) finding that the experience with the learning platform predicted satisfaction, but not learning outcomes – although again, learning transfer was not being measured. Satisfaction with the learning platform may be a hygiene factor, serving to prevent satisfaction from dropping, rather than to increase it, and warrants further research.

7.4 Overall Satisfaction

The overall satisfaction ratings (‘recommend programme to friends’) are a critical measure for the school, as they correlate highly with ‘net promoter scores’ measured six months after a programme. The strong correlation between overall satisfaction and ‘applied learning at work’ might suggest that the more a participant is able to apply his/her learnings at work during the programme, the more likely s/he is to recommend the programme to a friend on completing the programme (as these variables measure phenomena happening at different times).

It is encouraging to see that the correlations and hierarchical regression analyses results for overall satisfaction are congruent with the results for application of learnings. Thus, focusing on the ‘action learning’ and ‘program content and structure’ benefits the participants and their organisations, and the school itself, in terms of attracting more business.

7.5 Other Factors Affecting Learning Transfer

The multiple regression analyses show that, in this study, a large proportion of the variance in learning transfer is not accounted for. Part of the variance in the change in leadership behaviour might be attributed to, amongst other things, events occurring aside from the programme, or what Goldstein and Ford referred to as ‘history’ (2002). This study focused on the pedagogical design and delivery aspects affecting learning transfer, two further factors defined by Kraiger et al (1993) are learner characteristics (ability, skill, motivation and personality), and learner context (climate, social support, constraints and opportunities use learned behaviours).

In terms of learner characteristics, Colquitt, LePine and Noe’s (2000) meta-analysis showed that participants’ internal locus of control related to higher motivation, which correlated positively with training transfer. Research since then supports these findings (Wang, Shannon and Ross, 2013, Wu, 2016).

In terms of learner context, studies have shown that transfer of learning is also function of how conducive the participant’s work environment is to applying new skills (Tracey, Tannenbaum and Kavenagh, 1995). Ford et al (1997) stipulated that the extent to which a trainee is provided with or actively obtains work experiences for which s/he was trained, is affected by both trainee characteristics and supervisory support.

8 Limitations

8.1 The Multi-rater survey

The author opted for pre-post testing using a 360FS to avoid self-rater bias. However, Goldstein and Ford (2002) highlight various threats to internal and external validity of pre- and post-testing to consider, which, in this study of an open-enrolment programme, include:

- The events between the pre-test and post-test aside from the training, which could influence results, were not controlled for here. Future research using pre-post testing could include questions in the post-test about the experiences and training events in the life of the participant between the end of the programme and the post-test.

- The leniency of raters, i.e. higher or lower leniency in rating between pre-test and post-test as a result in changes in the rater, for example, could affect post-test scores. Participants’ raters in the pre-test were not always the same as in the post-test, but insisting on identical raters for pre- and post-tests would not have been pragmatic in this context.

Goldstein and Ford (2002) also recommend conducting three tests: pre-programme, one at the end of the programme and one sometime after the programme (although they do not specify how long after) – which, for an open-enrolment program, was not practicable.

8.2 Sample size

The sample size of this study was modest due to the low response-rate for the post-test, and whilst statistically significant results were found, larger samples would be required to get a fuller picture of the relationships between the variables, and the reader is asked to exercise caution when extending these results to other EL soft-skills or executive development programmes.

8.3 The Criterion challenge

Whilst specific models from the literature have been used to help define the criteria chosen to measure variables in this study, the absence of a framework of criteria to measuring EL effectiveness makes it challenging. A further challenge resides in operationalising the criteria (drafting questions). Anecdotal feedback from participants indicated that raters who had a lesser command of English found the questions in the 360FS challenging to understand. As a result, misinterpretations may have occurred. The survey would need to be translated, and/or the wording simplified.

9 Recommendations for further Research

9.1 Re-thinking multi-rater feedback

The mean differences in the 360FS ratings for each area of leadership were not statistically significant for each rater-group. Results for the manager rater-group were statistically significant in three only areas: ‘secure-base leadership characteristics’, ‘conflict management’ and ‘leading teams’. Results for the direct-reports group were statistically significant for ‘leading others’, ‘leading teams’ and ‘leader as a coach’. These differences raise the question of what behaviours managers and direct reports are in the best position to provide feedback on. A recommendation would be to tailor the 360FS to each rater-group, making the survey shorter for raters and possibly a higher response-rate and providing more valid information, making pre-post testing easier to for participants to complete and researchers to conduct.

Paul Leone (2014) recommends doing away with pre- and post-tests altogether, given they are cumbersome and face many validity threats, and relying on a multi-rater post-test to measure the level of ‘improvement’ of the participant.

9.2 Learner Characteristics and Context

As described above, a number of factors that have shown to affect learning transfer have not been measured in this study, notably learner characteristics and learner context. Learner characteristics include levels of familiarity with technology, anxiety, self-efficacy, motivation to complete the programme and personality. Diagnostic questions could be asked in a pre-programme survey, and could provide data to adapt/tailor the learning experience for the participant. Paul Leone (2014) suggests a series questions to assess how conducive the participant’s work context is for applying learnings; these could be asked during the programme, to raise awareness of potential challenges for the participant, and provide important information for the coach.

Given the very high completion rate of this programme (94% over all runs to date), and given that EL interventions tends to be stretched over longer periods of time than F2F programs, it would be worth exploring what precisely motivates participants to maintain their pace during and to complete the programme.

9.3 Coaching Support and Feedback

With the advent of more freely available information and training online (notably MOOCS), and increased competition in the EL market, pressure on pricing of EL is mounting. Student-coach support and feedback is time-consuming and the largest variable cost of this EL programme. Studies show that the presence of programme tutors to be a motivating factor for them to complete the programme, and certain activities help to enhance perceived learning (Arbaugh, 2010, Baker, 2010), investigate the skills required of tutors (McPherson and Nunes, 2008), or specify actions to take to enahnce the student experience (Jones, 2012). Future research could therefore delve deeper into the types of interactions participants have with their coach, to find out exactly how much interaction is necessary, and what types of interaction and support promote learning transfer.

10 Conclusion

This research seeks to supplement the literature of EL by exploring the effectiveness of leadership soft-skills EL targeted at middle to senior managers. The results show that, based on a multi-rater feedback questionnaire run before the programme start and four months after the end of the programme, there was an improvement in the leadership behaviours of the participants, which correlated highly with the extent to which they applied their learnings at work during the eight week programme itself. The latter in turn correlated with a number of dimensions of the design and delivery of the programme, showing that certain basic pedagogical design principles remain at the heart of effective learning transfer and behaviour change. Program design and structure and active learning most strongly support application of the learning at work, which in turn influences leadership behaviour-change. Coach suport and feedback and student cooperation correlated with but did not predict application of learnings and overall staisfaction. The level of student cooperation happening in the context of the buddy and group assignments may be sufficient, and further interaction via, say, the discussion forums may be superfluous for learning transfer. The dimension which correlated most strongly with transfer of learning: program content and structure, not included in Chickering and Gamson’s 1987 principles, must be taken into account for future research into the effectiveness of EL programs.

Cite This Work

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing stye below:

Related Services

View allRelated Content

All TagsContent relating to: "Learning"

Learning is the process of acquiring knowledge through being taught, independent studying and experiences. Different people learn in different ways, with techniques suited to each individual learning style.

Related Articles

DMCA / Removal Request

If you are the original writer of this dissertation and no longer wish to have your work published on the UKDiss.com website then please: