Developmental Evaluation and Human-Centred Design as Strategy for Building Evaluation Capacity

Info: 10407 words (42 pages) Dissertation

Published: 26th Oct 2021

Exploring the role of developmental evaluation & human-centered design as strategies for building evaluation capacity, organizational learning & evaluative thinking: theory, outcomes, and directions for future research.

The emphasis on accountability to public and private donors has normalized compliance and performance measurement in nonprofits. Evaluation is viewed as a tool to ensure oversight over their activities and resources, rather than a means to support organizational learning (Carman, 2010; Wing, 2004; Hall, 2004). Yet, the sector has always been called upon to respond to complex social challenges. For instance, the field of human services has seen a recent push for what is described as 2-generational/whole family programming – a departure from the prior focus on a single intervention to remediate a single problem/cause (Miller et al, 2017; Chase-Landsdale & Brooks-Gunn, 2014). Many nonprofits are at the forefront of this work, both locally and globally. However, in delivering holistic services, nonprofits often have to blend and braid services from different providers to meet the needs of their clientele—an area where innovation and adaptation gain salience. It requires social service providers (and by extension their donors/funders) to be nimble in all aspects of program design, implementation, and evaluation.

Traditional evaluation approaches that rely on discerning linear cause-effect relationships are not necessarily well suited for programs that address complex social problems and that require collaborative approaches to problem-solving (Patton 2010; Innes & Booher, 2010; Sandfort 2018). What is needed instead are evaluation approaches that acknowledge the complexity of causes, context, and systems, that bolster program staff and organizations’ capacity to learn and use data iteratively and ultimately channel efforts toward innovation and adaptation (Patton, 2006). Newer approaches like developmental evaluation and tools like human-centered design hold promise in this area (Patton, 2010; Hargreaves, 2010; Patton, McKegg & Wehipeihana, 2016; Gamble, 2008; Bason, 2017).

While these less traditional forms of evaluation and newer approaches to design are gaining traction, there is limited knowledge around the mechanisms through which they operate, their origins, practice, as well as outcomes. In order to consider their use and applicability, an inquiry into their philosophical underpinnings, practice principles and outcomes in necessary. The literature presented in this paper is guided by the following overarching research question for the study:

To what extent does the use of developmental evaluation and human-centered design as methods for program design and evaluation contribute to –

- Building evaluative thinking among nonprofit program staff and leadership?

- Building capacity to use data for future program design and adaptation?

- Innovation in program development?

The purpose of this paper is to begin articulating a conceptual framework that maps the relationship between developmental evaluation and human centered design methods, the mechanisms they activate, and their relationship with outcomes such as evaluation capacity, evaluative thinking and organizational learning.

Organization of this paper

This paper is organized into four sections. The first two sections will describe and define terms commonly used in the nonprofit evaluation space and articulate the limitations of conventional accountability and evaluation methods. The third section will discuss the philosophical origins, practice and outcomes of DE and HCD methods. The final section summarizes literature around the outcomes of evaluation capacity, organizational learning and evaluative thinking and presents an initial conceptual framework that maps the relationship between the methods, their mechanisms and outcomes.

Origins and landscape of evaluation and accountability in nonprofits

Like the pervasiveness of accountability in public and private sectors (either through financial audits or performance management), nonprofits (both in the US and globally) are subject to a multitude of accountability demands from both public and private funders/donors. Ebrahim (2005) notes the contribution of the organizational ecology literature in providing some insight into the reasons for this accountability: “The organizational ecology literature has suggested that accountability provides a sense of stability in organizational relations by maintaining the commitments of members and clients” (p. 59).

Before examining the tools/mechanisms using which accountability is enforced (evaluation being one of them), it might be pertinent to define accountability in the context of nonprofits.

Accountability is commonly defined as the “means by which individuals and organizations report to the recognized authority (or authorities) and are held responsible for their actions” (Edwards & Hulme, 1996, p. 967) or as the “process of holding actors responsible for action” (Fox & Brown, 1998, p.12). Scholars discuss the different types of accountability faced by nonprofits—accountability to donors/funders termed as “upwards accountability”; and accountability to clients/those that receive services (as well as staff) termed as “downwards accountability (Edwards & Hulme, 1996). Ebrahim (2005) argues that the current systems of accountability that drive the work on nonprofits suggests a “myopia” of stakeholders, learning as well as social change. He notes that “accountability mechanisms that emphasize rule-following operational behavior run the risk or promoting NGO activities that are so focused on short term outputs and efficiency criteria that they lose sight of long range goals concerning social development and change” (p. 61).

Program evaluation is one way to enforce accountability (others bring financial or legal audits) but one that is being increasingly utilized by funders, donors and nonprofits themselves to measure progress or uncover programmatic flaws and areas of improvement. However, for a long time, nonprofits, funders and donors have played into the hands of this “myopia” conducting evaluations solely for the purpose of measuring program outcomes or impact or for reasons of compliance (Fine, Thayer & Coghlan, 2000; Hoefer, 2000). Such forms of accountability (and evaluation) are often operationalized along a continuum of activities ranging from performance measurement to what is commonly described as “formative” and “summative” evaluations (where summative evaluations are often the end point of this continuum).

Performance measurement is the label typically given to “the many efforts undertaken within governments and in the nonprofit sector to meet the new demand for documentation of results” (Wholey & Hatry, 1992 as quoted in Newcomer, 1997). The movement and resources behind performance measurement has grown exponentially in the United States since the passing of the Government Performance and Results Act of 1993 which encouraged government and nonprofit agencies to measure “results” of their programs.

Formative evaluation is typically focused on “program/product improvement by in-house staff” where the findings are fed into an “improvement focused-process”; summative evaluations are implemented for the purpose of “determining the merit, worth, or value of evaluand in a way that leads to a final judgment” (Russ-eft & Preskill, 2009).

While all of these systems provide information that is useful for program staff, funders and donors, accountability more generally (and evaluation its dominant sibling) often generates a wave of anxiety and nervousness among nonprofit agencies. Riddell (1999) lends clarity to some of these concerns: he notes that the skepticism of (global) nonprofits surrounding evaluation has to do with the idea that NGO staff see themselves as doers that “ gain more legitimacy by helping the poor than by conducting time-consuming and costly evaluations” (Riddell, 1999 as quoted in Ebrahim, 2005). Another concern has to do with emphasis of existing evaluation systems to reward outcomes or “success” thus pushing nonprofits to utilize best practices or proven interventions instead of crafting innovative (and often risky) responses to the problems at hand (Riddell, 1999 as quoted in Ebrahim, 2005).

It is also important here to say something about the elevated status given to outcome assessments and what is commonly thought of as the gold standard impact evaluation(s). For instance, Khagram and Thomas (2010) note that the Coalition for Evidence Policy (a nonprofit working to improve government effectiveness) has advocated for gold standard randomized control trials so much so that a Government Accountability Report recommended that case studies “were only recommended for complex interventions when other designs were not available”. Impact evaluations rest on the ability to assign causality to outcomes yet discerning a singular cause-effect relationship is elusive in many cases. There is also growing attention among evaluation scholars and practitioners to the limitations of impact measurement and why impact measurement while valuable, might not be the best option to measure a program’s success in all situations. For instance, Gugerty and Karlan (2018) argue that a program may not be ready for a gold standard randomized-control trial and might instead benefit from program improvement techniques such as a formative evaluation. Many other scholars support this view and argue for the re-examination of impact measurement as the true north when it comes to evaluating a program’s success (Scriven, 2008; Cook, 2007). Another conversation that has taken shape recently is around causality–there is growing acknowledgment among scholars and practitioners that a range of methods/approaches can test a causal claim. As such, evaluators must be perceptive of the context of the evaluation, literate in multiple ways of thinking about causality and familiar with a range of design/methods to assess causal claims (Gates & Dyson, 2016). In fact, Khagram and Thomas (2010) advocate for the adoption of a “platinum standard” which would “[recognize] the validity of a wide array of methods and epistemologies for assessing performance”.

Current social problems and limitations of traditional conceptualization of evaluation

“I think the next century will the century of complexity.”

- Stephen Hawking, 2000

As the quote suggests, today, the world no longer operates in linear patterns (and in fact it never did). Think about how the economic crisis in a small country like Greece can send a wave of anxiety globally or how at times well laid out strategic plans fail to enable any organizational change. Our thinking (as well as ways to measure change/process) assume a linear, additive model which privilege predictability and control. There is a tendency to assume a linear worldview where the input is proportional to the output and that if one understands the parts of a system, we understand the whole and can thus, predict outcomes.

Scholars argue that many existing model in economics, management, and physics were built on such Newtonian science principles in which the dominant metaphor is the “machine” (Zimmerman, Lindberg & Plsek, 2009). If you understand the parts and its mechanism, you can predict and control the output. Social problems rarely align with this Newtonian perspective. Think about a nonprofit working to build financial capability among its clients/customers through the use of a financial product—the outcomes of this intervention are multifaceted and it would be wrong to assume that the customer’s improved “financial capability” in years can be accurately and fully mapped to this specific intervention. Think about a collaboration of public leaders/organizations who have joined hands to address racial disparities in the state’s hiring practices. Is it possible to converge on one policy outcome to measure change or progress or to predict how the system will react to these collaborative efforts? A complexity frame offers some explanation.

Zimmerman, Lindberg and Plsek (2009) offer the idea that “complexity is a metaphor”—it implies living, dynamic systems as opposed to a machine. The emphasis is on understanding relationships and emergence rather than the elements of the system (Colander & Kupers, 2014; Meadows, 2008). Scholars note a number of properties shared by complex systems (Colander & Kupers, 2019; Zimmerman, Lindberg & Plsek, 2009; Byrne & Callaghan, 2013):

- Complex systems exhibit “fractal” patterns. A fractal system is one where the “higher dimensions of a system have the same structure as the lower dimension of a system” (Colander & Kupers, 2014). For instance, in a tree the branching appears at all levels. The evolution of such fractal systems is governed by simple rules from the lowest to the highest order essentially emphasizing the idea that what appears to be complex (tree) is a nested structure made up of numerous simple structures (branches).

- Another feature that distinguishes simple systems from complex is the concept of “basins of attraction” as opposed to equilibrium (Colander & Kupers, 2014; Zimmerman, Lindberg & Plsek, 2009). The foundational idea of linear systems is “equilibrium”; complex systems have “basins of attraction” in that there is no one possible/desirable outcome and the fundamental task/purpose of change in a complex system is to move the system from a less favorable basin of attraction to a more favorable one.

- In complex systems, the size of the outcome may not be correlated to the size of the input. A large push to the system may not move it at all and a small push may create a palpable effect (often termed the “butterfly effect”).

- Complex systems tend to self-organize which gives rise to emergence/unpredictability.

If many complex social systems share these properties, the current conceptualization of evaluation and accountability mechanisms is problematic. First, program and changes in outcomes can no longer be treated with finality; second, one must do away with the temptation of assigning singular causality to an outcome or set of outcomes; third, complexity does not imply “beyond reach”—instead, understanding simple patterns on a granular scale can provide insight into patterns that govern the larger system. This revelation, however, is not new. As Colander and Kupers (2014) point out:

“Scientists have always realized that the reductionist approach, which involves assuming away many of the interconnections to make a problem tractable for solving, was at best a useful approximation. They used it as a pragmatic approach” (p. 47).

Another (related) critique of the conventional systems of evaluation and accountability has to do with the Western origins of the underlying philosophy of positivism or empiricism and one which positions the researcher as the expert. In a seminal work titled Decolonizing Methodologies, Smith (2012) notes: “From an indigenous perspective, Western research is more than research that is just located in the positivist tradition. It is research which brings to bear, on any study of indigenous peoples, cultural orientations, a set of values, a different conceptualization of things such as time, space and subjectivity, different and competing theories of knowledge, highly specialized forms of language and structures of power” (p. 44). More simply put, the machine metaphor privileges a certain epistemology rooted in the Western context.

This skepticism around reductionist ways to assess causality has been accompanied by a growing demand and emphasis for using complexity approaches in evaluation (Byrne & Callaghan, 2013). Yet, dominance of methods like RCTs often preclude their use even in contexts where these approaches might be relevant. Evaluation approaches that acknowledge complexity of causes, context, and systems is also limited by funders’ perceived need for simple boiler plate evaluations that provide yes/no answers (Hall, 2004). While these at times might adequately serve the purposes of accountability, the growing interest in less traditional forms of evaluation requires more investigation into their theory and practice as they hold promise for an alternative way of looking at causality/program impact, bolstering organizational learning and innovation, and operationalizing complexity and a systems approach to program design, implementation, and evaluation.

Overview of developmental evaluation and human-centered design

Developmental evaluation (DE) is a form of program evaluation that informs and supports innovation and program development (Hargreaves, 2010; Patton, 2010; Patton, McKegg, & Wehipeihana, 2016). It anticipates and addresses change in complex social systems and is currently being used in a number of fields in which nonprofits play important roles, from agriculture to human services, international development to arts, and education to health (Patton, McKegg, & Wehipeihana 2016; Dozois, Langlois & Cohen, 2010; Lam & Shulha, 2012).

Human-centered design (HCD) is an approach that attends specifically to the user-experiences throughout the design process and generally involves a cycle of

1) exploring the problem space

2) generating alternative scenarios (or prototyping) and

3) implementing new practices (including rapid testing of alternatives) (Bason 2017).

The origins of user-centered design can be traced to developments in the field of human computer interaction and other areas like joint application design and participatory design movements in Europe which surfaced the need to use ethnographic research methods to understand users and the context in which they operate (Dunne in Cooper, Junginger and Lockwood, 2011).

The term “user” in user-centered is attributed to Norman’s (2013) seminal work Design of Everyday Things. Norman talks about human-centered design as a philosophy that undergirds all types of design-industrial, interactive and service design. In that, Norman shows that the principles of usability lie in the “user’s mental models, their understanding of how things operate based on their experience, learning or the usage situation” (Norman as quoted in Cooper, Junginger and Lockwood, 2011). He also compels designers to develop a deep understanding of the users’ emotional states; he argues that designed objects that “feel/look better, work better”.

Although design is often focused upon initiation and evaluation on assessment after the fact, human-centered design and developmental evaluation share a number of commonalities and their interplay has potential to generate favorable outcomes for programs and organizations. Both support rapid cycle learning among program staff and leadership to bolster learning and innovative program development (Patton, 2010; Norman, 2013; Brown, 2009). For instance, in applying these methods, program staff and evaluators/human-centered design practitioners work as equal partners to craft or adapt an intervention or program. In doing so, evaluators benefit from a holistic understanding of the program context held by program staff whereas, this continuous engagement brings program staff closer to the methods evaluators use (in the context of DE).

Norman (2013) further notes that “designers resist the temptation to immediately jump to a solution for the stated problem” and instead spend time developing a robust understanding of the issue at hand. This practice of holding off from an immediate solution to a problem is at the crux of both DE and HCD. In DE, the evaluator recognizes that the solutions are far beyond the technical expertise of the evaluator and/or the program staff nor can it be gleaned from existing research alone; instead, it requires using an iterative cycle of designing, piloting, and testing to fully understand the problem and craft a solution that can be incrementally improved over time (often in collaboration with others).

An area where DE and HCD seem to be different (at least in some sense) is in the methods they employ to carry out the iterative phases– human centered design relies on what Norman calls“applied ethnography” (think of a light touch ethnography). Design doesn’t necessarily privilege the more systematic qualitative or quantitative research methods (e.g. surveys, interviews, focus groups) that evaluation upholds; it relies on observations of target populations to inform product or service development. While both follow the idea of rapid assessment, DE requires the evaluator to be adept at blending the right research methods to rapidly test solutions and/or explore the program space (what Patton describes as “bricolage”). This isn’t to say that one is better than the other; design likely has more application and relevance in the initial stages of program design and development when there is less pressure on program staff and leadership to demonstrate program outcomes. DE, on the other hand, allows program staff and evaluators to capture emerging outcomes and the findings can be used in preliminary progress reports to donors or funders. Design has limited applicability in this area (nor is it its focus).

Table 1: Similarities and differences between DE and HCD processes

|

Developmental evaluation |

Human-centered design |

|

|

Differences |

||

|

Definition |

Form of evaluation used to support innovation and program development |

Technique that emphasizes product/service creation through a “user-centered” lens/input. |

|

Methods |

Bricolage of research methods including surveys, focus groups, interviews, observations |

Applied ethnography |

|

Application* |

Supports program design and development through systematic collection of data around problem(s) and/or viability of solutions (may be used to deepen the human-centered design process or used as a primary tool for program development when HCD has not been engaged). |

Primary tool for program design |

|

Similarities |

||

|

Theoretical underpinnings |

|

|

|

Practice principles |

|

|

|

Outcomes |

|

|

|

* When applied in tandem, they should (in principle) strengthen the process and produce more desirable outcomes. |

||

Theoretical/philosophical underpinnings of human centered design and developmental evaluation

Scholars who have pioneered the idea of developmental evaluation and human-centered recognize that the origins of tools like DE and HCD can be traced to alternative philosophies of science like pragmatism or relativism. This section explores these roots:

Pragmatism and “evolutionary learning”

Both DE and HCD can be seen as having links to pragmatism and pragmatic thinking — a philosophy popularized by scholars such as John Dewey, Charles Pierce, and William James. The origin of the word pragmatism can be traced to the Greek word “action” (Van de Ven, 2007). Ansell (2011) notes, “pragmatism places greater value on the open ended process of refining values and knowledge than on specifying timeless principles of what is right, just, or efficient” (p. 8). In taking this approach to pragmatism, his views can be seen as aligning with the more relativist pragmatic scholars like William James and Richard Rorty (Van de Ven, 2007). He discusses the idea of “evolutionary learning” that emphasizes the importance of experimentation and defines three defining conditions for evolutionary learning to occur: problem driven perspective, reflexivity, and deliberation. He argues that a problem solving perspective drives evolutionary learning by “subjecting received knowledge, principles and values to continuous revision”. Finally, he suggests that evolutionary learning occurs when the three conditions operate in a recursive cycle—one informed and reinforced by the other (for instance, a problem driven perspective leads to reflection which in turn leads to deliberation which in turn might shape understanding of the problem).

Another idea that links pragmatism and the concepts of human-centered design and developmental evaluation and one explicated by Ansell (2011) is that pragmatism extends beyond the traditional/positivist conceptualization of experimentation to a “provisional, probative, creative and jointly constructed idea of social experimentation” where the results of an inquiry process are regarded as “fallible” and its role is to continue to shape our understanding of the problem. Through embracing unpredictability and emergence and emphasizing an iterative process to program design or development, DE and HCD align with this idea.

Collaboration, “communities of inquiry”, and pluralism

Another related idea that has its roots in relativism and can be linked to DE and HCD is that of “communities of inquiry” which follows the same cycle as described in the context of evolutionary learning – problem formulation, reflection, and deliberation (Innes & Booher, 2010). Innes and Booher (2010) note, “unlike the positivists, who depend on abstract analytic categories and logical deductive arguments, in a community of inquiry, participants bring their experience, their theories and their praxis. They seek out facts, place them in context, try out actions, and jointly assess the results”. Van de Ven (2007) describes this as “triangulating on a complex problem” where engagement of diverse perspectives helps uncover assumptions, expands the understanding of reality, as well as surfaces common themes. It is through such means that DE and HCD can be said to create new (and deeper) understanding of problem as well as its solutions. Innes and Booher (2010) also evoke Bohm’s contribution around dialogue. The authors argue that what ensues from dialogue is an “exposing of frames” that each participant holds to create new and shared meaning. ”. In describing “learning processes” that facilitate evaluative inquiry, Preskill and Torres (1999) also underscore the importance of dialogue as a way to “inquire, share meanings, understand complex issues and uncover assumptions”. Finally, Innes and Booher (2010) allude to the idea of “bricolage” where participants leverage prior experience and tools to circumvent an impasse (Levi-Strauss as quoted in Innes and Booher, 2010). In DE and HCD, the developmental evaluator and/or HCD practitioner is said to guide the inquiry process through such bricolage – he/she leverages existing research tools and methods to support learning and program development rather than sticking to pre-established plans, designs or methods (Patton, 2011).

The DIAD theory (Innes & Booher, 2010) – diversity, interdependence, and authentic dialogue—is a useful framework to think about successful collaborative processes (including “dialogue”). In articulating this theory, Innes & Booher (2010) describe what they call the conditions for “collaborative rationality”– diversity and interdependence of interests among participants and authentic face to face engagement. While it is ideal to strive for this, HCD and DE processes do not provide any specific articulation of these conditions as being necessary to operationalize the methods. This is not to say they are unnecessary; however, whether the specific characteristics of engagement/dialogue must exist for DE and HCD to be successful remains an area to be explored.

Another way scholars lend support to methods like HCD and DE is through the idea of collaborative design (Ansell &Torfing, 2016). They note three generative conditions that explain the link between collaboration and innovation:

- Synergy of resources, ideas and interests among stakeholders and/or participants

- Learning which generates new insights and shared meaning

- Commitment to a particular innovation

Both HCD and DE facilitate such processes –they build synergy of ideas and resources among stakeholders and a commitment to innovation while creating opportunities for learning among participating members (Paton, 2011; Norman, 2013).

The similarities in purpose and process calls for the articulation of common practice principles that undergird DE and HCD and that can be accessible to both evaluators and human-centered design practitioners. The purpose of articulating these practice principles is in some way to make the implicit, explicit and demystify what can be rather nebulous concepts of DE and HCD.

Common practice principles governing developmental evaluation and human-centered design

Drawing on prior work in policy and program implementation and complexity science, Sandfort (2018) and Sandfort and Sarode (2018) articulate these practice principles. At the core of the principles is the commitment to engaging in an understanding of the larger systems within which the program operates as well as attention to the target group experiences that are central to the design/evaluation work (Sandfort and Moulton, 2015). Next, descriptive artifacts (e.g. newsletter, reports, personas) are used both to build a common understanding of the problem as well as to generate solutions. Solutions undergo rapid testing by evaluators and/human-centered design practitioners to facilitate learning and dialogue among program staff and leadership. Finally, the most viable solutions are allowed to take shape in the form of prototypes or pilots. While neither DE/HCD scholars have specified an end point for this iterative process, Norman (2013) prescribes a “repeat until satisfied” approach. And while this point of satisfaction might be less elusive in certain situations of product/service design, programs that address complex social issues (e.g. unemployment, housing, education, health) often operate in a dynamic environment making it difficult for managers to achieves this state of “satisfaction” in program design/development –this is why programs and services need to be open to some form of DE/HCD approaches throughout their life cycle.

Outcomes of DE and HCD approaches

While a lot has been said about the need for cross-boundary methods such as human-centered design and DE and their relevance to address complex social problems, few scholars have traced the individual and organizational level outcomes that result from these processes. This brings up the need to both explicitly articulate what results can achieved from using these processes as well as how the mechanisms that guide them further these outcomes. In doing so, I will supplement literature that addresses outcomes around dialogue and collaboration with that around evaluation capacity and evaluative thinking (the reason being HCD and DE align closely with strategies that have been discussed in the organizational learning and evaluation capacity building literatures).

The DIAD theory (discussed above) articulates the results of “authentic dialogue” as reciprocity, learning, relationships and creativity (Innes & Booher, 2010). Further, Meyer (in Cooper, Lockwood & Junginger, 2011) discusses design’s intrinsic benefits or outcomes for an organization as:

- Engagement: with the organization and its purpose among organizational members

- Ethos: knowing what the organization stands for

- Collaboration: working together to solve problems

- Vision: developing a shared and unified concept of where their goals will lead

- Coherence and alignment: among organizational strategies and action through continuous questioning of purpose

- Accountability: by ensuring that customers’ problems are addressed

- Learning and reflection: which in turn “deepens investment in and dedication to work”

More specifically, the outcomes resulting from DE and HCD can be seen as falling under three broad categories (some of the other outcomes discussed above have been identified as mechanisms through which other outcomes like learning are activated. See Figure 2). The section below will take a closer look at these concepts and explore their links with DE and HCD:

- Individual and organizational learning (OL)

- Evaluative thinking

- Evaluation capacity

Individual and organizational learning: In the discussion around the outcomes of dialogue and collaborative processes, learning (among organizational members) surfaces as a constant theme. Argyris and Schon (1978) explicate the link individual learning and organizational learning. They note, “organizational learning occurs when, individuals, acing from their images and maps, detect a match or mismatch of outcome to expectation which confirms or disconfirms organizational theory in use…but in order for organizational learning to occur learning agents’ discoveries, inventions and evaluations must be embedded in organizational memory” (p. 19) essentially arguing for the idea that while individual learning is central to organizational learning, organizational learning per se does not occur unless such learning is encoded in organizational memory and the organization’s “theory-in-use” as a whole evolves. Fiol and Lyles (1985) also share this distinction between individual and organizational learning. Argyris & Schon (1978) between what they call organization’s “theory in action” (what is reflected in organization’s documents such as job descriptions, mission and vision statements, etc.) and the “theory in use” which may be tacit but often drives most of the organization’s work and actions.

Further, the definitions of terms that are commonly employed in OL are salient in the context of this paper:

Single and double loop learning

Single loop learning can been interpreted as a linear process of error detection and error correction wherein “organizational members detect an error and make adjustments to correct it in order to improve performance, but do not question underlying program norms when formulating the response” (Shea & Taylor, 2017). On the contrary, in double loop learning the discrepancies between the organizations “espoused theory of action” and “theories in use” gives rise to the potential of altering organizational norms and principles to ensure alignment with the changing nature of and the environment in which program activities occur (Argyris & Schon, 1978). Error detection and correction mediated through DE and HCD approaches has the potential to foster both single and double loop learning and address problems that are both peripheral to an organization (e.g. product improvement) as well as ones that are more fundamental to its theory of action.

Meta and deutero learning

Meta- and deutero-learning are two additional concepts/terms that appear in the OL literature. Visser (2007) describes meta-learning as a conscious and intentional process and one that enhances chances for organizational/program effectiveness. Deutero learning, on the other hand, is subconscious and may not always result in improved performance. This difference can be illustrated as follows:

“Meta-learning is characterized by cognitive, conscious, and explicit “steering and organizing” that involves reflecting on processes through which single-loop and double-loop learning happen. In contrast, deutero-learning is an unintentional, subconscious form of learning that takes place indirectly through social conditioning, as the result of casual conversations, in- formal interactions, and observations.” (Visser, 2007 as quoted in Shea & Taylor, 2017)

Through activating collaborative processes and including program staff in program design and evaluation, DE and HCD can be seen as facilitating such intentional learning.

Five building blocks of organizational learning

Garvin (1993) describes the five building blocks of organizational learning as 1) Systematic problem solving 2) Experimentation 3) Learning from past experience 4) Learning from others and 5) Transfer of knowledge.

The five building blocks (specifically systematic problem solving and experimentation) reinforce the idea and importance of conscious and intentional processes for bolstering OL (an idea described as meta-learning earlier). For instance, in learning from past experiences, Basten and Haamann (2017) note “learning should occur as a result of careful planning rather than chance”. The idea of learning from others (e.g. customers) also aligns well with DE and HCD processes that place user experiences at the center of learning and feedback (Bason, 2017; Patton, 2011). In describing the mechanisms for transferring knowledge, scholars note that while training is a viable mechanism, it is important for organizations to provide opportunities to apply this learning—an area addressed by DE and HCD methods.

Finally, in describing the connection between developmental evaluation and organizational learning, Shea and Taylor (2017) note “[t]o catalyze OL, DE activates critical reflective practice by applying evaluation logic to formulate probing questions about whether the program is performing as expected and core program assumptions in light of program-relevant data” and subsequently allowing organizational staff to be better equipped to use data to inform programming.

Scholars argue that while organizational learning has received much attention in the past, little practical guidance on how to implement strategies that bolster organizational learning has resulted in organizations struggling with operationalizing the concept (Garvin et al, 2008; Taylor et al, 2010; Vera & Crossan, 2004; Preskill and Torres, 1999). Further, emergent and complex programs (like 2-Gen programming) present additional challenges for organizational learning as detection and error correction is made difficult by the lack of clear theories of actions or mental images among program staff (Moore & Cady, 2016). Shea & Taylor (2017) note that “[an] over-exuberance of innovation” in these contexts can lead to incorrect application of single and double loop learning where problems that could potentially be resolved with simple error correction may be seen as requiring restructuring of organizational norms and principles.

Buckley et al (2015) argue that while “[evaluative] skills and attitudes can only exist at the individual level [and] in order for an organization to adopt an evaluation culture, a critical mass of the individuals who make up that organization must possess them”. Again, the focus of methods like DE and HCD to engage all levels of organizational members in program development and evaluation (instead of making evaluation the sole responsibility of an evaluator or the leadership) holds promise for building this “critical mass” within an organization that can ultimately translate into organizational learning.

Evaluation capacity and evaluation capacity-building: Evaluation capacity building (ECB) is defined as “an intentional process to increase individual motivation, knowledge, and skills, and to enhance a group or organization’s ability to conduct or use evaluation” (Labin et al, 2012). The claims of developmental evaluation and human-centered design as strategies for bolstering staff and organizations’ capacity to learn can be seen as falling under the umbrella of evaluation capacity building (Preskill & Boyle, 2008; Bourgeois & Cousins, 2013; King & Volkov, 2005). More specifically, they align closely with the idea of “purposeful socialization” as one of the strategies for evaluation-capacity building (King & Volkov, 2005; Preskill & Boyle, 2008). However, what differentiates DE and HCD from formal evaluation capacity-building initiatives (at least to some extent) is not how much evaluation knowledge staff gather or whether or not they become skilled evaluators themselves; it’s their ability to foster a quest for inquiry that is salient. In that sense, DE and HCD can be seen as contributing to Preskill and Boyle’s (2008) idea of “organizational learning capacity”. And if done well, this has the potential to create a favorable environment for future formal ECB initiatives.

Here the distinction between “evaluation capacity” and “evaluation capacity building” is important – one is an outcome and the other is a process. Bourgeois, Whynot and Theriault (2015) define evaluation capacity as the “the competencies and structures required to conduct high quality evaluation studies (capacity to do) as well as the organization’s ability to integrate evaluation findings into its decision-making processes (capacity to use)”. This definition lends clarity to two things (in the context of this study)—

- First, it signals a departure from the earliest conceptualization of evaluation capacity by Milstein & Cotton (2000) as the “ability to conduct an effective evaluation” by conceptualizing evaluation capacity as both the ability to do and use evaluation.

- Second, it elevates (in some sense) the use of evaluation to the same level as that of the ability to “do” evaluations. This is important because a majority of ECB strategies (for instance training, professional development, internships) seem to reinforce the idea that ECB is about “ teaching and learning strategies to help individuals, groups, and organizations, learn about what constitutes effective, useful, and professional evaluation practice” (Preskill & Boyle, 2008).

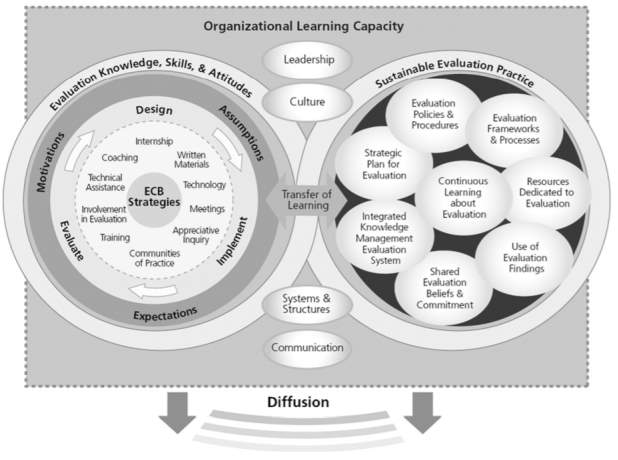

Preskill and Boyle’s (2008) “multi-disciplinary model of ECB” and the “integrative evaluation capacity building model” put forward by Labin and colleagues (2012) are some of the principal ECB frameworks. While Preskill and Boyle (2008) focus attention on evaluation skills, knowledge and attitudes, sustainable evaluation practice, and organizational context, Labin and colleagues (2012) identify ECB outcomes and the link between key ECB strategies, processes, and ECB outcomes.

Figure 1: Preskill & Boyle’s Multi-disciplinary Model of Evaluation Capacity Building

Other scholars (Cousins et al, 2014; Cousins, Goh, Clark and Lee, 2004) take this a step further and make the distinction between direct and indirect ECB strategies categorizing methods such as training (both formal and informal) into direct ECB strategies “that are designed specifically to foster growth in evaluation knowledge and skills” while separating activities where “participants learn by doing” into indirect ECB strategies. They argue that “the central construct in indirect ECB is process use” which is enabled through direct experience or close proximity to evaluation or evaluative processes (Cousins et al, 2014). Developmental evaluation and human-centered design can been seen as facilitating such “process use” through bringing organizational members and program staff in close proximity to evaluative processes (Patton 2011; Cousins, Whitmore & Shulha 2013). In fact, one of the origin theories of evaluation capacity building is said to be Patton’s idea of “process use” itself (King, 2017).

Evaluative thinking: A number of scholars have pointed to “evaluative thinking” as an outcome of evaluation capacity-building initiatives (Baker and Bruner, 2012; Bennet and Jessani, 2011; Davidson, Howe and Scriven, 2004). Scholars have also used multiple definitions to define the term, including describing evaluative thinking as “reflective practice” or the process of “questioning, reflecting, learning and modifying” (Baker & Bruner, 2012; Bennett & Jessani, 2011; Vo et al, 2018; Buckley, Archibald, Hargraves, & Trochim, 2011).

In tracing the historical roots of evaluative thinking, Patton (2018) evokes the Freirean pedagogy and the democratic evaluation model. He notes: “The democratic evaluator must make the methods and techniques of evaluation, and critical thinking, accessible to general citizenry”. He also explicates the interconnection between his own work around the idea of process use and its links to evaluative thinking: “Process use is distinct from use of the substantive findings in an evaluation report. It’s equivalent to the difference between learning how to learn versus learning substantive knowledge about something” (Patton, 2008, p. 152).

Buckley et al (2015) note that building evaluative thinking is not the prerogative of formal evaluation or ECB efforts (although it is a critical component of it). More importantly, they provide guiding principles for promoting evaluative thinking among members of an organization and allude to the importance of leveraging incremental, naturally occurring opportunities to build evaluative thinking. This allows us to draw connections to DE and HCD as viable strategies for promoting evaluative thinking.

Articulating a conceptual model

The goal of the literature discussed above is to provide an introduction to concepts and constructs closely interlinked with methods such as developmental evaluation and human-centered design and take the first step toward developing a conceptual framework that maps the relationship between these methods and the concepts of organizational learning, evaluative thinking, and evaluation capacity-building. Figure 2 presents an initial visualization of this conceptual framework and explores how methods like DE and HCD activate evaluative thinking, organizational learning, and innovation.

The conceptual model begins by mapping the origins of DE and HCD around an epistemology grounded in relativistic pragmatism where knowledge about truth is derived from consequences for practice /action (Rorty as quoted in Van de Ven, 2007) and methods that embrace pluralism are key. Ontologically, it takes a complexity stance dismissing a linear and predictable worldview and instead privileging emergence and uncertainty. Leveraging its pluralistic epistemology, it operationalizes “collaborative inquiry” through diversity of perspectives and interdependence of interests facilitated through a process of dialogue. In doing so, it aligns with indirect strategies for evaluation capacity building. The resultant individual and organizational outcomes are individual and organizational learning, evaluation capacity and evaluative thinking and innovation where:

- Evaluative thinking is characterized by “reflective practice” or the process of “questioning, reflecting, learning and modifying” (Baker & Bruner, 2012; Bennett & Jessani, 2011; Vo et al, 2018; Buckley, Archibald, Hargraves, & Trochim, 2011).

- Organizational learning is “the process of improving actions through better knowledge and understanding” (Fiol & Lyles, p. 803).

- Innovation a new idea or initiative that works in a particular setting (Mulgan & Albury, 2003).

The articulation of this conceptual framework is merely the beginning and more work remains to be done to understand fully the mechanisms through DE and HCD activate these and other outcomes.

Figure 2: An initial conceptual framework mapping the philosophical roots, operational strategy and potential outcomes of DE and HCD processes

Outcomes

Cross-boundary strategies

Epistemology: Relativistic pragmatism

Concluding Remarks

The literature summarized in this paper is a first step in exploring the philosophical roots, the practice principles and the outcomes of methods like developmental evaluation and human centered design. Both the articulation of specific outcomes and the mechanisms through which these outcomes are achieved is still work in progress. Additionally, there is also lack of an evidence base that investigates the links between these methods and their outcomes. For instance, questions like “to what extent do all DE and HCD processes involve a successful collaborative inquiry process (where diversity of perspectives, interdependence of interests and dialogue play a vital role)? How do variations influence the outcomes that result?” merit additional exploration. Another set of questions that merits additional exploration has to do with whether these links to outcomes (around organizational learning, evaluative thinking and innovation) actually exist in practice.

For instance, “to what extent does the use of developmental evaluation and human-centered design as methods actually contribute to building evaluative thinking among nonprofit program staff and leadership, building capacity to use data for future program design or adaptation and/or innovation in program development?”

Further, this literature only makes an initial introduction to the underlying processes by which “dialogue” (and collaborative inquiry more generally) enable outcomes like organizational learning or evaluative thinking. These links must be further investigated. This paper provides a first step in that direction.

References

Ansell, C. K., (2013). Pragmatist democracy: Evolutionary learning as public philosophy.

Argyris, C. (1999). On Organizational Learning (2 edition). Oxford ; Malden, Mass: Wiley-Blackwell.

Argyris, C., & Schön, D. A. (1997). Organizational learning: A theory of action perspective.

Baker, A., Bruner, B., Sabo, K., & Cook, A. M. (2006). Evaluation capacity & evaluative thinking in organizations. Bruner Foundation. Retrieved from http://www.evaluativethinking.org/docs/EvalCap_EvalThink. pdf

Bardach, E., & Lesser, C. (1996). Accountability in Human Services Collaboratives-For What? and To Whom? In J-PART (Vol. 6). Retrieved from https://academic.oup.com/jpart/article-abstract/6/2/197/1018836

Bason, C. (2017). Leading Public Design: Discovering Human-Centered Governance. Bristol, United Kingdom: Policy Press.

Basten, D., & Haamann, T. (2018). Approaches for Organizational Learning: A Literature Review. SAGE Open, 8(3). http://doi.org/10.1177/2158244018794224

Bennett, G., & Jessani, N. (Eds.). (2011). The knowledge translation toolkit: bridging the know-do gap: A resource for researchers. New Delhi, India: Sage.

Bourgeois, I., & Cousins, J. B. (2013). Understanding Dimensions of Organizational Evaluation Capacity. American Journal of Evaluation, 34(3), 299–319.

Bourgeois, I., Whynot, J., & Thériault, É. (2015). Application of an organizational evaluation capacity self-assessment instrument to different organizations: Similarities and lessons learned. Evaluation and Program Planning, 50, 47–55.

Buckley, J., Archibald, T., Hargraves, M., & Trochim, W. M. (2011). Defining and Teaching Evaluative Thinking: Insights From Research on Critical Thinking. However, American Journal of Evaluation, 36(3), 375–388.

Carman, J. G. (2010). The accountability movement: What’s wrong with this theory of change? Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 39(2), 256–274.

Chiva R., Ghauri P., & Alegre J. (2014). Organizational learning, innovation and internationalization: A complex system model. British Journal of Management, 25, 687-705.

Colander, D. C., & Kupers, R. (2016). Complexity and the art of public policy: solving societys problems from the bottom up. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Cooper, R., Junginger, S., & Lockwood, T. (Eds.). (2013). The handbook of design management. A&C Black.

Cousins, J. B., Goh, S. C., Elliott, C. J., & Bourgeois, I. (2014). Framing the Capacity to Do and Use Evaluation. New Directions for Evaluation, 2014(141), 7–23.

Cousins, J. B., Whitmore, E., & Shulha, L. (2013). Arguments for a Common Set of Principles for Collaborative Inquiry in Evaluation. American Journal of Evaluation, 34(1), 7–22.

Davidson, E. J., Howe, M., & Scriven, M. (2004). Evaluative thinking for grantees. In M. Braverman, N. Constantine, & J. K. Slater (Eds.), Foundations and evaluation: Contexts and practices for effective philanthropy (pp. 259–280). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Dozois, E., Blanchet-cohen, N., & Mcconnell, T. J. W. (2010). DE 201: A Practitioner’s Guide to Developmental Evaluation.

Ebrahim, A. (2005). Accountability Myopia Accountability Myopia: Losing Sight of Organizational Learning. https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764004269430

Ebrahim, A. (n.d.). Accountability In Practice: Mechanisms for NGOs. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0305-750X(03)00014-7

Edwards, M., & Hulme, D. (1996). Too close for comfort? The impact of official aid on nongovernmental organizations. In World Development (Vol. 24). https://doi.org/10.1016/0305-750X(96)00019-8

Fine, A. H., Thayer, C. E., & Coghlan, A. (2000). Program evaluation practice in the nonprofit sector. Nonprofit Management and Leadership, 10(3), 331–339. https://doi.org/10.1002/nml.10309

Gamble, J. A. A., & Mcconnell, T. J. W. (2008). A Developmental Evaluation Primer

Garvin, D. A. (1993). Building a learning organization. Harvard Business Review, 71, 78-91.

Hall, P.D. (2004). A Historical Perspective on Evaluation in Foundation. In M. Braverman, N. Constantine, & J. K. Slater (Eds.), Foundations and evaluation: Contexts and practices for effective philanthropy (pp. 27-50). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Hargreaves, M. B. (2010). Evaluating System Change: A Planning Guide. Princeton, New Jersey.

Hoefer, R. (2000). Accountability in action?: Program evaluation in nonprofit human service agencies. Nonprofit Management and Leadership, 11(2), 167–177. https://doi.org/10.1002/nml.11203

Innes, J. E., & Booher, D. E. (2010). Planning with complexity: An introduction to collaborative rationality for public policy. Routledge.

Innes, J. E., & Booher, D. E. (2018). Planning with complexity: An introduction to collaborative rationality for public policy. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge

Khagram, S., & Thomas, C. W. (2010). Toward a Platinum Standard for Evidence-Based Assessment by 2020. In Source: Public Administration Review (Vol. 70).

King, J. A. (2007). Developing Evaluation Capacity through Process Use. New Directions for Evaluation.

King, J. A. (n.d.). Transformative Evaluation Capacity Building. Retrieved from https://www.cehd.umn.edu/OLPD/MESI/spring/2017/King-Transformative.pdf

King, J. A., & Volkov, B. (2005). A framework for building evaluation capacity based on the experiences of three organizations. CURA Reporter, 10-16.

Labin, S. N., Duffy, J. L., Meyers, D. C., Wandersman, A., & Lesesne, C. A. (2012). A Research Synthesis of the Evaluation Capacity Building Literature. American Journal of Evaluation, 33(3), 307–338.

Lam, C. Y., & Shulha, L. M. (2015). Insights on Using Developmental Evaluation for Innovating: A Case Study on the Cocreation of an Innovative Program.

Lindsay Chase-Lansdale, P., & Brooks-Gunn, J. (2014). Two-¬-Generation Programs in the Twenty-¬-First Century. Two-Generation Programs in the Twenty-First Century (Vol. 24). Retrieved from www.futureofchildren.org

Meadows, D. (2015). Thinking in systems: a primer. White River Junction, VT: Chelsea Green Publishing.

Milstein, B., & Cotton, D. (2000). Defining concepts for the presidential strand on building evaluation capacity. Paper presented at the 2000 meeting of the American Evaluation Association, Honolulu, Hawaii.

Mulgan, G., & Albury, D. (2003). Innovation in the Public Sector.

Newcomer, K. E. (1997). Using performance measurement to improve programs. New Directions for Evaluation, 1997(75), 5–14. https://doi.org/10.1002/ev.1076

Norman, D. (2013). The design of everyday things: Revised and expanded edition. Constellation.

Patton, M. Q. (2008). Utilization-focused evaluation (4th ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Patton, M. Q. (2011). Developmental Evaluation: Applying Complexity Concepts to Enhance Innovation and Use. New York: The Guilford Press.

Patton, M. Q. (2018). A Historical Perspective on the Evolution of Evaluative Thinking. New Directions for Evaluation, 2018(158), 11–28. http://doi.org/10.1002/ev.20325

Patton, M. Q., McKegg, K., & Wehipeihana, N. (Eds.). (2016). Developmental Evaluation Exemplars: Principles in Practice. New York: Guilford Press.

Patton, M. Q. (2006). Evaluation for the way we work. Nonprofit Quarterly, 28-33.

Preskill, H. S., & Torres, R. T. (1999). Evaluative inquiry for learning in organizations. Thousand Oaks, Calif: Sage Publications.

Preskill, H., & Boyle, S. (2008). A multidisciplinary model of evaluation capacity building. American Journal of Evaluation, 29(4), 443–459. http://doi.org/10.1177/1098214008324182

Salamon, L. M. (2012). The Resilient Sector. The State of Nonprofit America. Retrieved from https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/thestateofnonprofitamerica2ndedition_chapter.pdf

Sama-Miller, E., Ross, C., Eckrich Sommer, T., Baumgartner, S., Roberts, L., & Chase-Lansdale, P.L. (2017). Exploration of Integrated Approaches to Supporting Child Development and Improving Family Economic Security. OPRE Report # 2017-84. Washington, DC: Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation, Administration for Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services

Sandfort, J. R. (2018). Theoretical foundations and design principles to improve policy and program implementation. Handbook of American Public Administration, 475.

Sandfort, J., & Moulton, S. (2015). Effective implementation in practice: Integrating public policy and management. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Shea, J., & Taylor, T. (2018). Using developmental evaluation as a system of organizational learning: An example from San Francisco.

Smith, L. T. (2012). Decolonizing Methodologies: research and indigenous peoples. New York: ZED BOOKS LTD.

Torfing, j., & Ansell, C. (2014). Collaboration and design: new tools for public innovation. In Public innovation through collaboration and design (pp. 19-36). Routledge.

Van de Ven, A. (2013). Engaged scholarship a guide for organizational and social research. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Visser, M. (2004). Deutero-Learning in Organizations: A Review and a Reformulation.

Vo, A. T., Schreiber, J. S., & Martin, A. (2018). Toward a Conceptual Understanding of Evaluative Thinking. New Directions for Evaluation, 2018(158), 29–47.

Zimmerman, B., Lindberg, C., & Plsek, P. (2009). A Complexity Science Primer: What is Complexity Science and Why Should I Learn About It?

Cite This Work

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing stye below:

Related Services

View allDMCA / Removal Request

If you are the original writer of this dissertation and no longer wish to have your work published on the UKDiss.com website then please: