Follies and the History of the Garden

Info: 16776 words (67 pages) Dissertation

Published: 16th Dec 2019

Tagged: ArchitectureArts

POLITICS & PALLADIANISM – Follies and the history of architecture

SEX & SECRECY – Follies and the history of art and literature

NATURE & NURTURE – Follies and the history of the garden

Bibliography: Secondary Sources

Illustrations

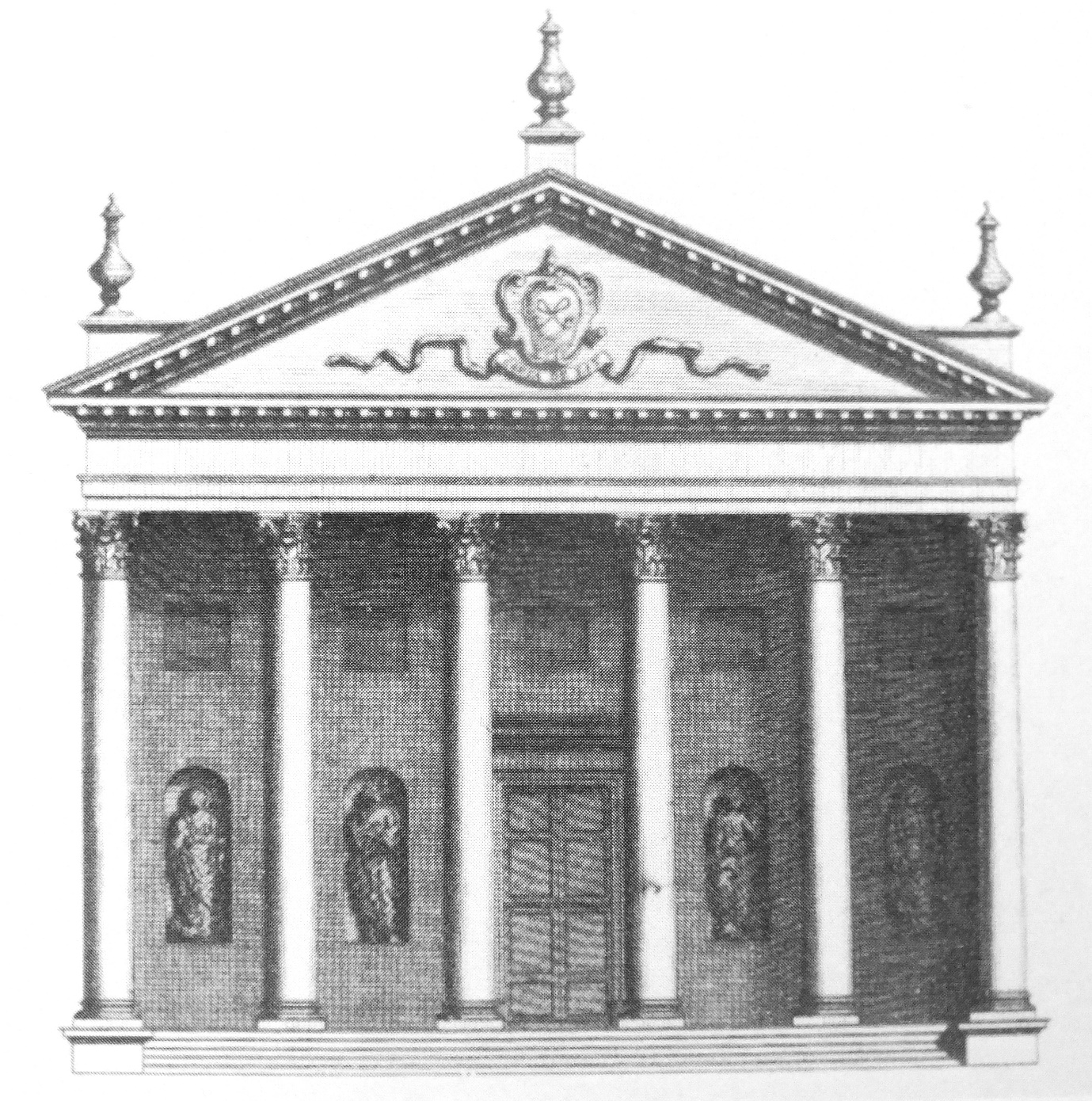

Fig. 1. Garden Room, 1724, Hall Barn, Beaconsfield. Source: Colen Campbell, Vitruvius Britannicus, Vol. III. (1725), C3, PL. 49.

Fig. 2. Vanbrugh’s garden temple (c.1717) at Eastbury, Dorset. Source: Colen Campbell, Vitruvius Britannicus, Vol. III. (1725), C3, PL. 18.

Fig. 3. Gunnersbury Park, Middlesex. Source: Colen Campbell, Vitruvius Britannicus, Vol. I. (1725), C1, PL. 18.

Fig. 4. Temples of British Worthies. Source: Trevor Rickard, Geograph.org, 22 September 2010 [accessed 17 April 2017].

Fig. 5. Temple of Ancient Virtue, Stowe. Source: National Trust.

Fig. 6. Temple and Parlour of Venus, West Wycombe, c.1740s. Source: Robbob Tun, Panoramio, 18 August 2013 [accessed 17 April 2017].

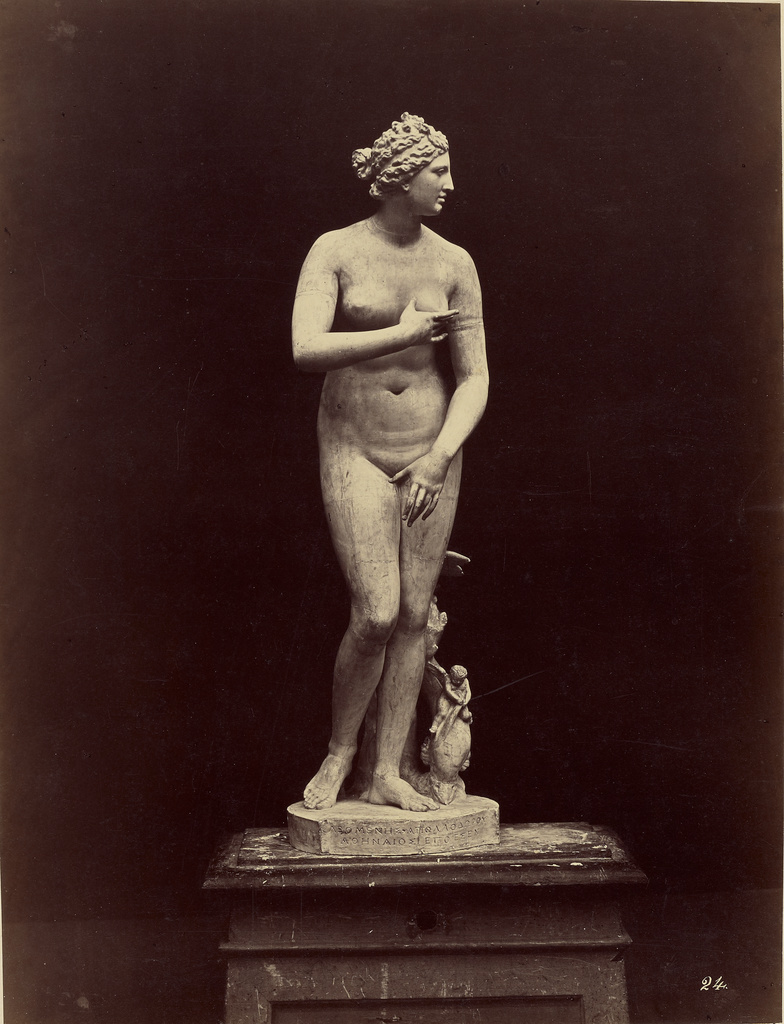

Fig. 7. Venus de’ Medici. Fratelli Alinari (photographer ), 1856 – 1872, Albumen silver print, 33 x 25.2 cm. J. Paul Getty Museum, 84.XM.508.2.

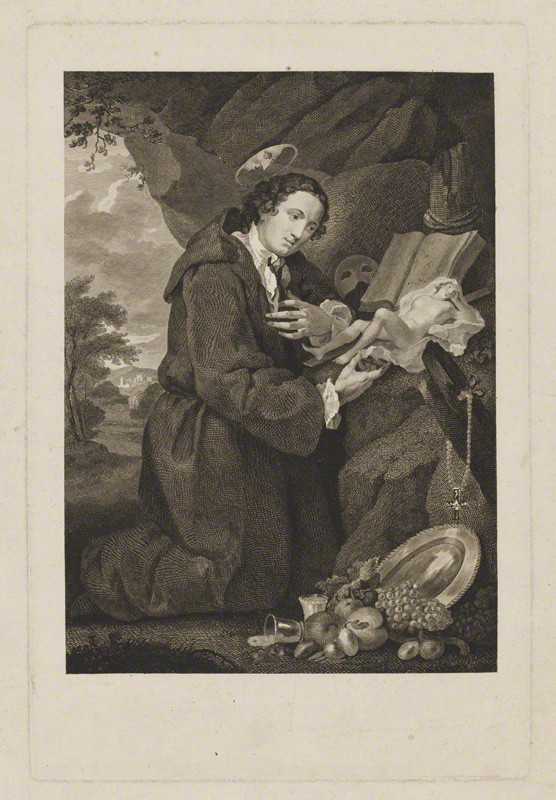

Fig. 8. Sir Francis Dashwood Worshipping Venus, William Platt, after William Hogarth, Late C18. Engraving, paper, 378 millimetres x 253 millimetres. British Museum, 1858,0417.476.

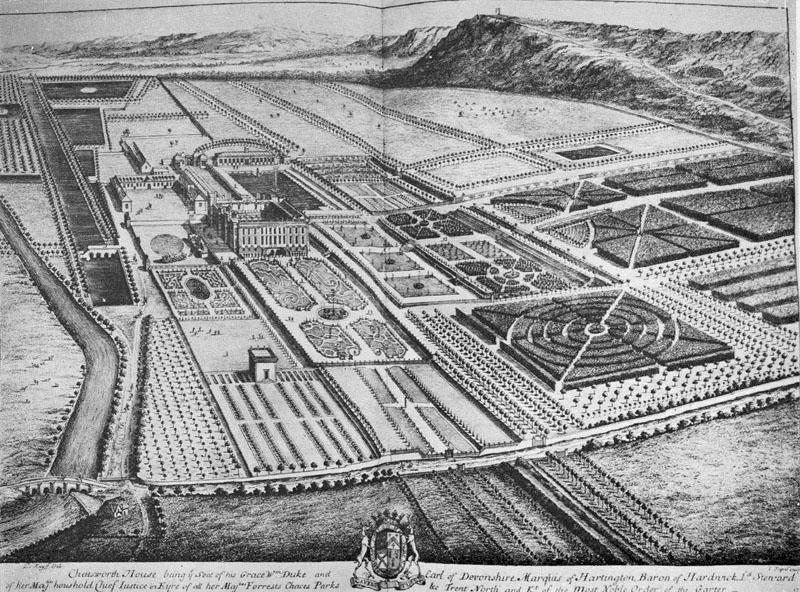

Fig. 10. Chatsworth, 1699.

Introduction

The breaking up of the vast estates of the eighteenth-century peerage has left architectural remnants scattered across the British Isles. Among these relics are temples, arches, columns, grottoes, and sham ruins, and many are now genuine ruins. Belonging to the gardens of the past, today these curious structures are known collectively as ‘follies’. The term implies these buildings have lost not only their environment but also their meaning, it suggests they are ‘useless, whimsical or inconsequential’.[1] ‘Folly’ is not the contemporary term used for them, in the eighteenth century they were collectively known as ‘eye-catchers’, but the great number built suggests that they were much more than mere optical fancies. In a brief introduction to George Mott’s picture book, Follies and Pleasure Pavilions, Gervase Jackson-Stops provides a dazzling glimpse into the extraordinary depth and purpose of these buildings, that stimulated the inquiry behind this dissertation. It is easily found that these buildings served practical purposes as resting and vantage points and shelter from the weather, but what is more interesting is that many appear to have been imbued with hidden meanings that reflected the thoughts, pastimes, and ideologies of the people who built them. Objects do not exist in a vacuum but form part of a greater cultural and social context and the historical drive is to find out what that is, how it came to be and to pass and who was behind it. This dissertation, therefore, seeks to resolve these problems and answer why follies were so popular in the eighteenth century and what they have to tell us about the culture in which they were created.

Literature Review

There is no seminal scholarship on follies and garden architecture, although there is a broad catalogue of peer-reviewed articles, mostly under the genres of garden and landscape history and some architectural history. However, these usually focus on one or two specific collections of buildings by location or by architect, limiting their scope for historical analysis. Ownership of garden architecture history appears to be one major reason for the paucity of scholarship, as Diana Balmori explains in Architecture, Landscape, and the Intermediate Structure, ‘because studies have tended to focus on either architecture or landscape and not on their interrelation ‘.[2] Architectural historians, such as Giles Worsley who compares the works of John Vanbrugh, William Kent and Nicholas Hawksmoor in Sir John Vanbrugh and Landscape Architecture, tend to ignore garden buildings in favour of main residences or focus on the architects rather than the patron.[3] Discussion tends to focus on aesthetics and materials without exploring why they were built and what they represented. Where debate does shift to the commissioners of garden architecture, the interest is often political and military motivations of architecture, keeping it very much in the public, masculine sphere rather than the domestic. This is due in part to the theory of architectural historian, Christopher Hussey, who proposed in the 1950s that neo-Palladianism was a Whig aesthetic and Baroque was the preferred style for Tories.[4] Whig political expression is a key theme for Stowe’s current archivist, Michael Bevington, who concurs, and Carole Fry who uses the garden architecture of Dawley, Wilbury House, Stourhead and Tottenham Park to challenge Hussey’s assertion.[5]

Garden historians tend to be more challenging about the physical presence of garden buildings if only to find out why there are so many manmade objects interrupting their verdant milieus. This is the undertone to John Phibbs’ essay The Structure of the Eighteenth-Century Garden, in which he expresses a Brownian desire to do away with distracting structures from circular walks.[6] Generally, garden history tends to focus on the wider image of the landscape, in terms of nature, beauty and the picturesque, reducing follies to symbiotic elements of a mis-en-scene that limits their contribution to its meaning. This is the problem that Balmori is addressing, arguing that garden buildings that mimicked nature, such as grottoes and hermitages, were a mediatory effort to bridge the chasm between manmade architecture and the natural environment. Gwyn Headley & Wim Meulenkamp, who are perhaps the foremost authority on British follies, having documented and visited almost every surviving one, are also the most reluctant to engage in any scholarly debate. Instead, they prefer to stimulate it with their gazetteers and Follies Fellowship society which produces enthusiast-led journals and magazines to promote the preservation of follies.

To better understand the genres and its historians, this dissertation adopts a different genre in each chapter through which to analyse garden architecture while keeping follies as the core object from which to explore their context. As architecture and garden sculptures are a fine art, a third approach will be to analyse follies in relation to the genre of art history. To support this methodology, additional historiographies are included to give a background to the wider social, political and cultural contexts being applied. David Coffin’s visual cultural analysis of the popular garden goddess in Venus in the Eighteenth-Century English Garden focuses specifically on follies and garden sculpture. The historiographies of sexual freedom and sexual literature by Faramerz Dabhoiwala and Jolene Zigarovich, respectively, are not directly linked to follies but provide a relevant background to the emergence of erotic material culture.[7] One final point is that since ‘folly’ is not a contemporary term for garden buildings, its use will be limited except to express true eccentricity, such as Francis Dashwood’s creations at West Wycombe. Instead, ‘architecture’, ‘buildings’, ‘structures’ and ‘eye-catchers’ will be used to discuss all varieties of folly collectively.

Methodology

Most case studies of garden buildings and their related historical documents have been drawn from the key theory and secondary sources through which they are being analysed, with a preference for locations within travelling distance of the author. Several of the follies discussed here are extant, especially at Stowe and West Wycombe, so it has been possible to use the buildings themselves as evidence and to visit although seasonal opening hours have restricted access at West Wycombe. There are caveats to the use of extant buildings, for instance, the buildings at Stowe have been moved several times since their initial construction which has obscured some of the original intentions of the design. At Stowe, sightlines connecting follies are important and sometimes the breaking of the sightlines is deliberate, such as moving Queen Caroline’s column when Viscount Cobham fell out with the Royals, but at other times it was not intentional. This has required careful referencing and chronological tracking to maintain an accurate impression. At West Wycombe, Venus’ Parlour and the gothic façade to the caves were destroyed, therefore it is important to note that the appearance today is an approximation and not entirely accurate of the original structures. Further loss of context occurs as gardens and estates are broken up and sold off or slip into decay. Often follies are ruined beyond recognition or salvation, in other instances, such as Stowe they are gradually undergoing conservation and restoration using original records. In most cases, with extant follies, it must always be borne in mind that they may have undergone undocumented remodelling or preservation by subsequent owners.

There is are many architectural plans, sketches, and connected documents in reprints of publications, such as Colen Campbell’s Britannicus Vitruvius, and in museums and private collections.[8] Some of these are available online, others are less accessible due to location or access restrictions, but fortunately, with so many specialised studies of follies, many of these artifacts have been reproduced in secondary sources. Also often lacking is an extant building to go with the plans and vice versa, some plans were never executed or were used at a different estate by their architects. Some follies have no discernible records that can be found to identify them. These issues has not proven to be a difficult barrier with the case studies examined here, as sufficient descriptions exist as to give a good impression of the structure, for example, Pope’s comprehensive writings on his, now demolished, grotto at Twickenham and William Gilpin’s extremely detailed descriptions of the painted interiors of the temples at Stowe.[9] Travelogs, letters, diaries, poetry and other individual writings which were published during the eighteenth century, have been accessed through digitalised collections at archive.org and Eighteenth Century Collections Online and in printed anthologies, which has removed a number of access issues. The limitations here are often in the content themselves, offering differing degrees of description, opinion, and comprehension depending on the cultural exposure of the writer. Furthermore, they are a snapshot in time, usually offering little background or detail of change.

Chapters

This dissertation takes a thematic approach to investigate the ideologies that might be expressed by garden architecture and each theme is then attached to a genre of history through which it may be analysed. Chapter One examines garden buildings through the lens of architectural history and analyses the debate on whether Palladianism is Whig architecture, using Stowe as a prominent example. In Chapter Two, Georgian attitudes to sex and their historical portrayal in art and literature is the topical focus for the case studies of West Wycombe and the popularity of Venus as a garden statue. Finally, Chapter Three looks at ornamental garden buildings as elements of garden history and how designers negotiated the problem of a manmade fixture in a natural environment. Primarily the discussion revolves around the grottoes and hermitages and more broadly brings into the discourse religion and the Georgian pursuit of pleasure.

Jackson-Stops remarks follies ‘have a magic, even in decay, that never fails to enchant’. [10] In fact, they have received so little scholarly attention in comparison to gardens and architecture, that we have ceased to comprehend them. This dissertation seeks to decode some of the mystery around follies while at the same amplifying their charm and unique contribution to material culture by better understanding their original purpose and intent. By examining them through different historical genres, it hopes to find an inter-disciplinary solution to the study of follies that bridges the current genre divide and offers a discourse to suit every historical purpose. Ultimately it seeks to prove that eighteenth-century follies were not foolish fancies but pearls of wisdom that have become lost in the landscape.

POLITICS & PALLADIANISM – Follies and the history of architecture

Around thy Building, Gibbs, a sacred Band / Of Princes, Patriots, Bards, and Sages stand:

Men, who by Merit purchas’d lasting Praise, / Worthy each British Poet’s noblest Lays:

Or bold in Arms for Liberty they stood, / And greatly perish’d for their Country’s Good:

Or nobly warm’d with more than mortal Fire, / Equal’d to Rome and Greece the British Lyre:

Or Human Life by useful Arts refin’d, / Acknowledg’d Benefactors of Mankind.[11]

This chapter examines how far architecture in garden buildings, and more generally, can be regarded as political propaganda and whether political allegiances were responsible for the dissemination of a particular style. It begins with a political and architectural survey of the eighteenth century, focusing on the rise of neoclassicism which influenced the design of a considerable number of garden structures. Carole Fry’s counterargument to Christopher Hussey’s popular theory that Whigs adopted neo-Palladianism while Tories preferred Baroque is expanded to consider whether neo-Palladian was a political or secular style.[12] Alternative reasons for adoption of an architectural style are offered, especially in relation to the influence of taste, friends, family and regional differences. Fry’s argument, for example, is based on the garden architecture at the estates of Wilbury, Stourhead and Tottenham Park, which were all connected by marriage and at Dawley which belonged to a Jacobite exile. It concludes with an examination of Stowe, arguably the most famous example of political garden architecture in England.

For the last sixty years, it has been mooted that the design of architecture in the eighteenth century, including the architect-designed buildings found in gardens, was influenced by political allegiances.[13] The right to vote in the eighteenth century was based upon ownership of property and wealth, presenting an opportunity for the nobility and wealthy mercantile ranks to subvert architecture for political and ideological causes. State political propaganda was already visible in public buildings, such as the Tory-sponsored Baroque, St. Pauls Cathedral and Greenwich Hospital which significantly redrew London’s landscape. For domestic architecture, each noble family had a country seat requiring a stately residence and many acquired townhouses and villas as the development of cities accelerated during the century. The impressive Prodigy Houses, built to host the Royal Court, declined as royal tours of the country no longer inspired the housebuilding of noble families. The Hanoverian Georges, the latest foreigners on the throne after Dutch, William III, rarely left London so the nobility went to them, contributing to a building boom of fashionable townhouses in the capital. With increasing wealth from overseas commerce and no longer spending great sums on Prodigy Houses, the next generation of estate-owners had the freedom to pursue architectural innovations, enabling new trends in architecture for which garden buildings became a means for stylistic experimentation.

The new architectural trend that became associated with these changes was neo-Palladianism, a style driven by scientific rules, optical balance and symmetrical beauty. Neoclassical architecture had been popular for garden buildings in the Tudor era before the infiltration of French Baroque on architecture.[14] At that time, neoclassicism was flourishing under Italian architects, such as the purist Andrea Palladio (1508-1580) and mannerists Leon Battista Alberti (1401-1472) and Sebastiano Serlio (1475-1554). Translations of their treatises inspired garden architecture in the eighteenth century, for example, the Pantheon at Stourhead was taken from a design in Serlio’s Tutte l’Opere d’Architettura et Prospetiva (1537-1575).[15] In turn, the Renaissance architects took their inspiration from Marcus Vitruvius Pollio (80BC-15AD), an architect of Rome whose Ten Books on Architecture was a manifesto for urban planning and architectural ideals. Vitruvius’ work was translated into English in 1726 by architect Giacomo Leoni (1686-1746) although Vitruvian-based designs were already being adopted via Leoni’s 1715 translation of Palladio’s Four Books of Architecture.[16]

Between 1715-1725, Colen Campbell (1676-1729) published three volumes of his pattern book Vitruvius Britannicus, which featured both neo-Palladian and Baroque designs. It mostly contained plans and elevations for domestic residences, rural villas, formal gardens and garden buildings, although the latter were usually slightly scaled down versions of main residences. The Garden Room (1724) at Hall Barn, Beaconsfield, (fig. 1) for instance, is a substantial structure that appears to be a detached extension of the main residence rather than an occasional, garden building.[17] Similarly, Vanbrugh’s garden temple (c.1717) at Eastbury, Dorset, (fig. 2) appears to have been lifted off the front of the house design for Gunnersbury Park, Middlesex (fig. 3).[18] This implies that whatever was driving stylistic changes in architecture was also applicable to garden structures. Neo-Palladianism and ornamental garden architecture appear to have peaked around the same period in the 1720s to 1730s under pioneers Vanbrugh (1664-1726), William Kent (1685-1748), Nicholas Hawksmoor (1661-1736) and Richard Boyle, 3rd Earl of Burlington (1694-1753). However, as Giles Worsley points out, some garden buildings, such as Kent’s Temple of Ancient Virtue (1734) at Stowe, were definitively Palladian, while others were of the experimental mannerist style, such as his Temple of Venus (1731) and Temple of British Worthies (1734) suggesting garden architecture was an opportunity to creatively bend the rules.[19]

Neo-Palladian principals of proportion and harmony have been applied to social and nationalist ideologies of the period as well as to architecture, Neo-Palladianism was well-suited to the immediate concerns of the noble elite who were being challenged by the swelling bourgeoisie, causing a redistribution of wealth down the social chain, and witnessing the increasing size and political might of a riotous poor underclass. Each Jacobite attempt on sovereignty, supported by exiled and malcontent nobles and politicians, underlined the vulnerability of the ruling class. Neoclassicism became the material representation of peace and harmony and the family garden was the perfect setting for contemplation, with temples and shrines becoming de rigueur. Another threat to family stability arose in the succession of George I (1715-1727) who had a low priority to the throne, ranking 58th in line after his mother, niece of Charles I. His election undermined the tradition of primogeniture in England which was the key protection for landed gentry to keep their estates intact and expanding through marriage rather than broken up through inheritance. Additionally, clauses prevented George from leaving England without Parliament’s permission or electing foreigners to high office, prompted by the behaviour of William III. This enforced anglicising of the ruling family and government coincided with new developments in architecture and landscaping revealing a desire to produce a quintessentially English style to rival previous French and Dutch influences. The long Hanoverian reign saw the decline of Baroque architecture and formal French and Dutch knot gardens which were usurped by neoclassical buildings in natural, landscape settings. These solid, timeless, extendable buildings and enormous oak and lime planted parks spoke of harmonious longevity and lineage which was supported entirely by the virtue of primogeniture.

In the 1950s, Christopher Hussey proposed his revolutionary theory that neo-Palladianism was a political movement, controlled by the elite circle of Lord Burlington, to differentiate the liberal Whigs from the Baroque-building Tories.[20] The concept was an appealing way to connect neoclassical architecture and philosophy with emerging modern politics and enlightenment. As Carole Fry observes,

Augustan Rome was considered to be the golden age of enlightenment from which to extract the principles of true and harmonious living. It was seen, in effect, as informing the ideal way of life. This philosophy pervaded all contemporary thought.[21]

Liberal politicians aspired to the democratic individualism of Plato and saw the Greek Senate as the ideal political state, a reaction to the ancien régime which had been successfully overturned in England following the Glorious Revolution of 1688. Metaphorically, the architectural orders, which provide structural support to the apex through the columns, represented the balance of power under the new constitution, its democratic, parliamentary representatives were the pillars of strength upon which the kingdom was now shouldered. While this might be the imagery that Whig history is keen to portray, it is merely a façade to the most riotous century in modern British history. The plebeian base on which this new order was constructed was disenfranchised and angry and numerous public riots broke out throughout the century, despite the passing of the Riot Act in 1714. Jacobite support endured over half a century and several rebellions were suppressed before the Hanoverian supremacy was secured. The Royals were no less tempestuous with strong antipathy between each generation ruining domestic and political relations. The rifts overflowed into the public sphere, where discontented politicians and ambitious social-climbers took full political advantage. Garden monuments were erected to show allegiance, such as the columns of George, Prince of Wales (George II) and his wife Caroline, at Stowe. An early example of neo-Palladianism in a domestic house, Wilbury, Wiltshire, built around 1710 by William Benson, appears to be political flattery rather than allegiance. Prior to George I’s arrival in England, neo-Palladianism was becoming popular in Hanover and Fry suggests that British visitors brought the architectural ideas to Britain in anticipation of the prince’s succession.[22] George was the son of the autocratic Elector, Ernest Augustus (1629-1698), who styled his court at Herrenhausen after Versailles and for whom Benson designed a water fountain.[23] Unlike his father, George ‘shared the prevalent Teutonic dislike and distrust of France as a nation’ and avoided the Baroque connotations.[24] The extreme antipathy between George I and Tory politicians may explain why some Tories rejected neo-Palladianism while Whigs quickly adopted it.

The connection between Whigs and neo-Palladianism assumes an allegorical association with Rome and metaphorical connotations of liberty, but it is more obvious why they rejected Baroque. The ostentatious French inspired style had connotations of absolutism and papism through its extensive use at by the autocratic, Catholic regimes at Versailles and Dresden. English and French relations were always fragile but had worsened since the Glorious Revolution, when William III attempted to use England as a pawn in Holland’s battle against France. The French court protected the family of James II and his exiled courtiers, continuing to recognise James’ sovereignty and initially supporting Jacobite incursions into England. In the colonies, France was a political thorn, weakening the British position in North America through the Seven Years War (1756-63), interfering in the American Revolution (1765-1783) and threatening the stability of the Caribbean plantations through the Haitian Revolution (1791-1804). The erection of neo-Palladian buildings, especially in the newly independent, United States of America, was the eighteenth-century equivalent of putting up a ‘Keep Calm and Carry On’ poster, a patriotic dependency on the emerging nationalist identity of stoic perseverance in the face of chaos. When France was at its most threatening, during its Revolution and Napoleon Empire, Britain intensified its neoclassical calm into every aspect of life including art, dress and interior design. Neoclassicism became a national style, imbuing manifold values besides liberal thinking, including anti-Catholicism, Francophobia, and growing patriotism, long after the Burlington set’s reign.

Fry challenges Hussey’s theory by arguing that neo-Palladianism was never dominated by Whig allegiances. As evidence, Fry estimates forty per cent of designs built from Vitruvius Britannicus were for Tory and Jacobite families and yet more subscribers were politically apathetic or of wavering allegiance.[25] Although there are Baroque designs in Colen’s volumes, they account for a much smaller percentage. This suggests that independent of politics or whether one intended to build a neoclassical structure or not, it was deemed necessary to be abreast of the trend and in possession of the literature. Howard Colvin reflects that ‘More Palladian buildings were no doubt built by Whigs than by Tories or Jacobites, but that was due to the accident of political ascendancy rather than to any ideological commitment to the style ‘.[26] Colvin identifies the pioneers of neo-Palladianism as the Tory, Henry Aldrich (1647-1710) and Jacobite, James Smith (1645-1731) and highlights that Campbell dedicated Vitruvius Britannicus to both Tories and Whigs.[27] Fry suggests the sycophant, William Benson, was an earlier activist than popularly credited Whig, Lord Burlington.[28] One of the issues raised by revisionist history is that less is known about political allegiances of prominent nobles than previously thought, since being a Tory or Jacobite, or even a sympathiser, became a slur on reputation as the century progressed. Research by Colvin and Ben Lennon suggests that Lord Burlington may have been a covert Jacobite, supported by his close friendship to the Jacobite descendant and Tory, Lord Bruce (1682-1747), through marriage.[29] The evidence could also be interpreted as liberal sympathy rather than proactive support, Burlington’s political career was ostensibly Whig.[30] The former Tory leader and Jacobite peer, 1st Viscount Bolingbroke (1678-1751) was a keen aficionado of neoclassicism and, inspired by Pliny the Younger. On returning from exile in 1723, Bolingbroke extensively redeveloped Dawley into a neo-Palladian villa and temple-riddled pleasure grounds, although at this point he was also seeking favour with George I.[31] The Cobham family at Stowe were staunch Whigs, and although the garden architecture is predominantly neoclassical, there is wide blend of styles, and its first architect, Vanbrugh, was best known for his Baroque work.

As a litmus test for political allegiance, a survey of extant garden buildings in Scotland, suggest neoclassicism fails to inspire the same ardour as in England, except in the anglicised, bureaucratic regions of Strathclyde (Glasgow) and Lothian (Edinburgh).[32] Elsewhere, sixteenth century castellated and Baroque architecture remained predominant and after the mid-century, squat, sturdy buildings with Gothic elements became extremely popular. Although this could be associated with Scottish political leanings as a stronghold for Jacobinism (Gwyn Headley’s gazetteer identifies at least two Jacobite motivated follies) it is more likely to relate to traditional taste and the harsh weather that Scottish garden buildings had to endure.[33] The few neoclassical temples that survive are of the Doric order, the shortest and sturdiest of the columns, with domed roofs which would prevent snow gathering. Domes were popular in England too, following Vanbrugh’s rotunda at Stowe (1721), but Ionic and Corinthian orders were the most common, though it is possible other orders existed in Scotland but were lost to the climate. Gothic Revival, which shares similarities with Baroque, was a complementary transition from existing styles and unlikely as political protest, since the first main residence built in the ne0-Gothic style, Inveraray Castle, Strathclyde, was constructed in 1745, the same year as the last, unsuccessful Jacobite rebellion in Scotland. It was slightly behind Gothic Revival’s emergence in England where it became popular from the late 1730s for light-hearted, novelty garden buildings and later fantasy houses such as Strawberry Hill (1749-1776) and Fonthill Abbey (1796-1813).

Although the argument for political architecture in England is strong, as the Scottish survey suggests, there are many practical reasons for adopting neoclassical styles. For example, the clean lines and rectangular structure were simpler to build and extend with symmetrical wings and did not require the extreme skills in stone-craft that Baroque and Rococo demand, saving on costs. On the other hand, in the provinces of England, building styles were slower to be updated and dictated by local craftsman skills, available building materials, and old-fashioned conservatism.[34] However, in these areas, neoclassical garden structures were an opportunity to participate in the trend without the cost or inconvenience of renovation to the main house. Family allegiances were probably as strong, if not more so, than political ones and more strongly responsible for transmitting garden architectural designs. Considering Fry’s observations that ‘[t]he subscribers [of Vitruvius Britannicus] were almost all from the upper echelons’ of society’ and ‘Connections within and between aristocratic eighteenth-century families, wealthy merchants and politicians included life-long friendships, marriages and, to a certain extent, political allegiances’,[35] it is highly likely that ideas were disseminated through patronage, marriages, and friendships. While these may have been created along political lines, other reasons for the familial influence on domestic design included family identity, inheritances and money-lending, and even placating meddlesome in-laws, as appears to be the case in the landscaping of Stourhead and Tottenham Park.[36]

Stowe is one of the earliest and most famous of the new style of Arcadian landscape that accompanied neoclassicism and while it has been argued to be strongly political, it is also a tribute to deep friendships and the arts. The garden buildings strongly demonstrate the philosophical and patriot Whig ideology of Viscount Cobham and to a lesser degree, his successor and nephew Earl Temple, but also reflects the ideologies of its architect, William Kent, and contributor, Alexander Pope. The Elysian Fields, the final resting place of the good in Greek mythology, was influenced by Alexander Pope and Joseph Addison,[37] and Cobham’s nephew, Gilbert West, in an ode to Stowe, suggests the scheme was a poetic tribute to classical art, writing ‘The same presiding Muse alike inspires / The Planter’s Spirit and the Poet’s Fires’.[38] West’s poem implies the grounds were split into thematic areas of philosophy, love, friendship, military and politics and frequently shared with friends. Cobham’s Temple of British Worthies, (fig. 4) is stocked with busts of philosophers, scientists and poets that he identifies with as evidenced by his own toga’d bust within the collection. It is connected to the Temple of Ancient Virtue (fig. 5) by line of sight, drawing a direct correlation and offset to the ruined Temple of Modern Virtue, denigrating the state of current public morality by contrast to the robust temples. Clearly, the garden structures at Stowe were intended to inspire visitors, as Cobham built an inn in 1717 for the purpose and in 1748, Gilpin published a fictional dialogue between two friends touring the grounds and discussing the buildings.[39] The poetic epistle to Lord Cobham from his friend, Congreve, suggests that far from political zealotry, the architectural landscaping of Stowe was a retreat from belligerent politics,

Or dost thou give the Winds afar to blow

Each vexing Thought and Heart-devouring Woe,

And fix thy Mind alone on rural Scenes,

[…]

Or dost Thou, weary grown, these Works neglect,

No Temples, Statues, Obelisks erect,

But seek the morning Breeze from fragrant Meads,

Or shun the Noontide Ray in wholesome Shades,

Or slowly walk alone the mazy Wood,

To meditate on all that’s wise and good?[40]

As the case studies examined have shown, architecture is political but is not as clear cut as being an identifying trait of a specific political ideology Fry, Colvin and Lennon successfully argue that neoclassical styles were used by estates owners of opposing political views or none. On the other hand, garden architecture may relate to a different set of ideologies such as familial harmony, education, travel, philosophical ideals or friendship. Furthermore, the evidence suggests that architecture was also influenced by regional differences as simple as the climate and skill availability as well as through the more complex relations of families and friends. The rise of neoclassicism seems to be due to a convergence of favourable circumstances, the rise of Whig politics, the exaltation of Augustan culture, the decline of Baroque due to its absolutist and Catholic connotations, and a new flood of wealth, creating a middling social rank with ample funds to build. For new wealth, inheritances and peerages, neoclassicism was the perfect statement of hope for a long and successful lineage and became increasingly patriotic as it began to be regarded as the English style. That many of these houses are still standing today is a testimony, however many have lost their garden architecture, which weakens its connection to lineage and suggests it was intended to be personal and current. Domestic architecture became a powerful tool of expression in the eighteenth century, but follies could make a more direct, individual statement as they did not have to keep up appearances, survive time or cost as much to build as houses. Ultimately neoclassicism was a secular national style that dominated all building works in England for the next century, as the prominent fashion for townhouses, rural villas, garden architecture and public buildings. But, although the serene temples and whitewashed, neoclassical façades may have suggested peace and harmony, this was far from the reality of the politically turbulent eighteenth century.

SEX & SECRECY – Follies and the history of art and literature

I must own, the noble Lord’s garden gave me no stronger idea of his virtue and patriotism, than the situation of [his] new-built church did of his piety […] I believe this is the first church which has ever been built for a prospect.[41]

This chapter examines garden architecture in relation to sex and secret fraternities. It briefly examines the debate over whether the development of liberty and privacy enabled greater sexual freedom, especially in the arts, and focuses on the speculation of sexual and satanic practices at West Wycombe’s underground folly. This was a series of caves created by Sir Francis Dashwood, 11th Baron le Despencer (1708-1781) and used for the meetings and intimate parties of the Order of St. Francis, a society of politicians and public figures. More commonly known today as the Hellfire Club, it was created around 1755 by Dashwood, at Medmenham Abbey, Maidenhead. Its participants dressed and performed mock ceremonies as monks and nuns and were ‘required to take an oath of secrecy, which, […] is frequently dispensed with’.[42] The chapter goes on to discuss other ways in which garden structures expressed erotic predilections, leading into an analysis of the interpretation of Venus, as a principal garden figure and goddess of carnal love, in contemporary accounts.

In the age of Enlightenment, Britain was increasingly seeking political freedom and individualism.[43] An area in which liberty was expanding throughout the eighteenth century was sexual freedom, the privacy to conduct extra-marital sexual liaisons without persecution by state or church. Jolene Zigarovich explains that ‘In eighteenth-century culture, burgeoning individualism, alongside Lockean liberalism, resulted in a segregation of political and domestic domains’.[44] While homosexual and extra-marital sex remained illegal, Faramerz Dabhoiwala argues that ‘the modern ideal of personal sexual freedom was born here’ with increasing permissiveness between 1660 and 1800 demonstrated through changes in attitude and behaviour.[45] Dabhoiwala counters the earlier popular arguments of Robert Shoemaker and Tim Hitchcock who disputed ideas of increasing tolerance and expression, at least for women and citizens of lower wealth and status, which she believes stems from Foucault’s argument of sexuality as a mechanism of power.[46] Zigarovich offers a third angle, suggesting that although ‘the Georgians appear to have been remarkably open in terms of sexual indulgence‘,[47] sex remained a titillating secret, stating Foucault’s belief that ‘until Freud, the discourse on sex […] never ceased to hide the thing they were speaking about ‘.[48] The dual standard that any man could openly have lovers while reputable women could not, on the surface supports Foucault’s theory of gender power bias, but on the other hand, suggests a subversion of sex by women both for pleasure and to gain surreptitious power over men. Nocturnal Revels (1779). an anthology of soft pornographic tales collated by Dashwood’s society, approves the acceptability of mistresses that arose under the Hanoverians, stating ‘The Women now had the leading power at St. James’s; a Great Man’s Mistress was more courted than the Prime Minister’ but likewise laments, ‘The treachery, perfidy, and stratagems of what are stiled Lady Abbesses’.[49] This view is the extreme end of the liberal spectrum for its time but does support an argument for women’s empowerment through sex, although it also shows that patriarchal society still sought to control women’s sexuality.

In terms of visual and material culture, the most compelling evidence for licentious permissiveness in the eighteenth century is the ubiquitous distribution of satirical caricatures, in which lewd imagery was prominent. In literature, some work fell to the censorship of the Lord Chamberlain, for example, John Cleland’s epistolary novel, Fanny Hill (1748-1749) whose protagonist not only uses sex to gain advantages but dares to enjoy it. However, others escaped, such as the sadistic, explicit Gothic novels Clarissa (1748) and The Monk (1796) in which male characters exercise sexual power over women whose loss of innocence is their ultimate demise.[50] Dashwood’s female guests at his underground masquerades, appear to relate to Fanny rather than Clarissa, invited for their ‘cheerful lively disposition’.[51] In 1763, Fanny Murray, mistress to John Montagu, Earl Sandwich (1718-1792) was the subject of a dedication in the obscene ‘Essay on Woman’, circulated by the infamous rake and liberal MP, John Wilkes (1725-1797). Both men were members of Dashwood’s club, falling out over the affair. Prior to West Wycombe caves, the Order met at Medmenham Abbey, which Dashwood deliberately ruined for fantastical effect, adding statues of Venus and Priapus, an unnaturally well-endowed Greek fertility god, which gave the society’s purpose a very explicit interpretation. Medmenham went from abbey to folly, becoming a space for frivolity and fornication, The phrase ‘faycequevoudras’ and pun, ‘Peni TentononPeni Tenti’ were inscribed into its garden sculptures and its library filled with erotic literature.[52]

The abbey and underground meetings of this secret society involved intimate parties centered on witty exchange, wine, food, and women and was perhaps one of the worst kept secrets of the century with members publicly writing about it. Nocturnal Revels, playing down the ribaldry, makes the unlikely claim ‘The ladies, in the intervals of their repasts, may make select parties among themselves, […] or alone, with reading, musick, tambour-work, &c ‘. implying it was little more than an informal dinner party among friends of the type found in decent houses.[53] Additionally, women were ‘not compelled to make any vows of celibacy […] considering themselves as the lawful wives of the brethren, during their stay within the monastic walls; every Monk being religiously scrupulous not to infringe upon the nuptial alliance of any other brother’. Although generally assumed to be prostitutes, the wording of Nocturnal Revels, suggests this was a private space in which men roleplayed marital bliss with their mistresses. Regardless of its cosy, domestic proclamations, the underground folly at West Wycombe was the protective setting for discreet debauchery.

Dashwood unashamedly embraced all aspects of Roman culture, from its highs of classical architecture and literature to its basest level of Bacchanalian banquets, wine, and orgies. His libertine preferences and satirical statements were expressed through garden architecture and fine art. William Hogarth, who illustrated scenes of debauchery in his series A Rakes Progress (1732-33) was also a member of the society. Hogarth was commissioned to create satirical paintings of Dashwood posing as a monk and the Pope, demonstrating a strong dislike of Catholicism. The Order was rumoured to be satanic, however this may be an assumption based on the publicised pranks of John Wilkes who on one occasion lowered a sweep through the banqueting hall chimney, ‘to the terror of the tipsy symposiasts, who believed that the Prince of Darkness had come for them at last’ and on another occasion released a baboon into the caves, dressed as the devil.[54] But far from being a diabolical rogue, Dashwood was a liberal and interested in social welfare, putting forward a poor-relief bill 1747 to provide employment for rural labourers inspired by his tunnelling of the caves, ostensibly to provide limestone for road building. Reflective of Dashwood’s character, his society was protective of its female members, conscious of their social vulnerability if identified. Women who became pregnant they were provided for and the ‘offspring […] stiled the Sons and Daughters of St. Francis’, looked after by the members ‘.[55]

West Wycombe’s caves thrived on the excitement of secrecy and illicit sex, but in the privacy of his residential gardens, Dashwood was more explicit in his erotic architectural allegories. The Temple of Venus (c.1740s), standing upon a grassy mount, is a very clear parody of the virtuous portrayal of Venus at nearby Stowe. However, it was not the temple that was of interest to the contemporary eye, but the Parlour of Venus (fig. 6) below, which subverted the piety of the temple and reminded the viewer of the true nature of the goddess. On each side, a wall gently inclines upwards to the mount where the temple stands immediately above an ovate opening, unabashedly mimicking a woman’s open legs and pudenda. In keeping with Dashwood’s adoration of women, Venus’ Parlour was a shrine to females and sex and to alleviate any doubt, Wilkes elucidated ‘the entrance to it is the same entrance by which we all come into the world, and the door is what some idle wits have called the door of life’.[56]

David Coffin in Venus in the Eighteenth-Century Garden suggests that Venus, as the goddess of gardens, was the most popular figure during the eighteenth century for country gardens. In particular, he states the century saw a quick refinement from previously generic representations of Venus to casts of the Venus de’ Medici (fig. 7), with the exception of a crouching Venus for grottoes.[57] The choice of the Medici statue tangibly links garden display to power and flattery, however, it also indicates the wealth of a patron as Coffin’s sources suggest casts were custom ordered from Florence and Rome.[58] It appears that to possess Venus, one required wealth, good foreign connections and a country estate in which to display her. At Stowe, a gilded Venus de’ Medici was the first statue to be erected and stood in a direct visual line with a statute of Caroline, Princess of Wales, drawing. This positioning, like the facing Temples of British Worthies and Ancient Virtue, is deliberate but Lord Cobham’s purpose is ambiguous.[59] The princess is on a par with the goddess, but is it admiration, a secret yearning or a reminder of her submissive role as consort and child-bearer to the king? If it was a deliberate pairing, the chaste, wise, strategist Minerva would have been a more flattering comparison for the highly educated, politically engaged, matrimonially faithful, princess.

Samuel Garth’s ‘Claremont’ (1715), also compares Caroline to Venus and simultaneously reduces her public role to that of breeder of future kings,

Like him, shall his Augustus shine in arms,

Though captive to his Caroline’s charms.

Ages with future heroes she shall bless;

And Venus once more found an Alban race.[60]

It therefore, seems likely that Cobham’s precise positioning is a chastisement to Caroline, that her role is not to interfere with court politics.

Even if Vanbrugh’s Venus was intended to be virtuous, her nakedness was her downfall, when observed in profile, the positioning of her restored hands did nothing to preserve her modesty.[61] Kent’s Venus at Stowe shows a more lascivious side, a crouching figure caught in the gaze of visiting voyeurs as she is about to enter a grotto pool. Venuses were certainly popular among male perambulators of the garden for more than her classical resonance, although her status as a goddess and sculpture condoned her pornographic connotations. The historian Edward Gibbon lustily describes the Medici Venus as

the most voluptuous sensation that my eye has ever experienced. The most soft, the most elegant contours, a soft and full roundness, the softness of flesh imparted to marble and the firmness one still desires in this flesh expressed without hardness,[62]

and Mrs. A. B. Jameson, remarks on the daily habit of the poet, Samuel Rogers, sat gazing at his Venus.[63]Not only was Venus beautiful and gloriously naked, but as a statue she was silent and undemanding, the ideal woman. Wives were expected to be virtuous, but Venus was willing as Thomas Jefferson’s declared of the Venus at Hagley Park, Worcestershire, in 1785, who was ‘turned half round as if inviting you with her into the recess’.[64] At Florence, in 1772, Sir Philip Francis took the suggestion even further debating ‘in his travel diary about whether he would prefer carnal relations with the Venus de’ Medici or Titian’s Venus’.[65] When Wilkes fell in lust with an Italian courtesan he wrote, ‘She was of a perfect Grecian figure ‘, and ‘cast in the mould of the Florentine Venus, excepting that she was rather taller ‘.[66] Venus de’ Medici was so idealised as the figure of femininity that her image was used in medical and science textbooks for further study, and reputedly the first drawn image of a female figure to have pubic hair, something her statue lacked.[67]

The domestic popularity and fetishisation of Venus are almost certainly due to her association with sexual love and perceived attainability, compared to the huntress Diana is who is turned into a laurel tree to prevent seduction and warrior-like Minerva, both of whom display distinctly masculine attributes to the eighteenth-century mind. Venus was also associated with lares, wine, brides, female coming-of-age rituals, and prostitutes, in short, she was the idealised sexualisation of women and Venus was a contemporary euphemism for female sexual partners.[68] Dashwood made her the patron deity of his Order, an infatuation that was portrayed in several images, showing Dashwood dressed as a monk, worshiping Venus and usually clasping a chalice. In William Platt’s version (fig. 8), Dashwood’s devilish claws are grasping at the recumbent Venus, surrounded by objects that are representative of the cave orgies, Bacchanalian fruits and wine, masks, and robes, a bible and rosary, making a pagan mockery of popery. Venus may indeed have been the most popular of garden goddesses in the eighteenth century, but it seems less to do with her being the goddess of gardens and more to do with her ‘lady garden’.

Zigarovich observes that ‘Characteristic of the Enlightenment, the Georgians appear to have been remarkably open in terms of sexual indulgence’ and their garden statues and Dashwood’s follies both under and above ground appear to support this idea.[69] The curves of the landscape, naked statues, and phallic columns barely concealed sexual undertones and offered opportunities for lewd inferences and stimulating sexual desire, made permissive by their superficial innocence. Dashwood’s subversive use of religion and classicism illustrates how selectively Roman and Greek ideology had been adopted and reinterpreted by the Georgians, who idolised the virtuous aspects of philosophy, democracy, and patriarchy while ignoring the underbelly of wine and sexual freedom that Dashwood and his comrades exploited. Considering their highly public positions, it appears that most Georgians were indeed willing to turn a blind eye to extra-marital relations, or even participate, supporting the theory of privacy and separation of sexual control from the state and church. Although acceptable for the male members of the Order who were not concerned about public knowledge of their pastimes, it highlights that even among the most liberal-minded people in England, there was still a dual standard for women who had to protect their identity within private spaces, to avoid scorn and shame publicly. The cruel irony is that the unabashedly naked Venus, was publicly revered in all her sexual connotations, while women could only achieve respect by being the opposite, or at least appearing to be, in public. Meanwhile, reputable men found little shame in admitting the effect of an attractive statue on the libido and even at virtuous Stowe, there was a naughty Venus waiting for them in the grotto.

NATURE & NURTURE – Follies and the history of the garden

While stately temples numberless arise, / Temples devote to heathen deities:

On which is spar’d no cost, no grace, no art, / (Such their importance) genius could impart;

… In Christian lands gods Pagan to prefer! / Christian! Is this in Taste or character?

Our country God eclips’s by foreign! Hence / To boast patriot virtue vain pretense.[70]

Chapter Three discusses the pursuit of pleasure in relation to a godly, and fashionable, desire to return to nature. It considers Diana Balmori’s argument that garden architecture is a mediation between main edifices and natural landscapes using the grottoes and hermitages as examples. It looks at how garden structures negotiated the changes from formal gardens to picturesque landscapes and the trend was disseminated along the way. It also looks at the relationships between garden architecture and religion, consumerism, and pastimes.

During the eighteenth century, there was a diametric shift in the grounds of country houses from precisely maintained terraces of enclosed gardens to sprawling parklands of seemingly untamed nature. While neatly clipped box yews, topiary and knot gardens were inspired by France, Holland, and Italy, the new landscape styled itself as English and, suiting the liberal mood of enlightenment, the garden was encouraged to be as natural and free as possible, though still within limits to prevent it becoming wild. Metaphorically, Under Whig ideology, the garden was the populace and the gardener was the state. Formal gardens dictated the form of an object, restrained its development and enforced its cohesion to the whims of power. As Alexander Pope expressed in 1713 when criticising the use of topiary instead of sculpture, ‘[we are] better pleas’d to have our Trees in the most awkward Figures of Men and Animals, than in the most regular of their own’.[71] The liberal landscape offered an unfettered opportunity for growth and organic elements could take their natural form. It was the horticultural equivalent to a Bill of Rights, offering the opportunity to fulfill natural potential compared to old state or feudal control which could restrict the rank and role of every person. However, the concept of a natural, liberated landscape is, like many aspects of Georgian self-promotion, something of a fallacy. While there was a definitive step away from clipped and controlled topiary, even sprawling nature was subject to the careful controls of man with many elements being artfully created to appear natural while satisfying the needs of its consumers.

Garden architecture had a variable relationship with the landscape movement of the eighteenth century. Several of the birdseye garden plans in Vitruvius Britannicus show buildings set within formal gardens and an engraving of Chatsworth from 1699 (fig. 9) shows temples, towers, fountains, statues of Flora and river gods and a musical water cascade set among European-style formal gardens, elements of which remained as late as 1760.[72] Over time, formal garden features were levelled and turned into long lawns and pasture, separated not by walls and parterres but by hahas, creating the illusion one infinite, uninterrupted landscape and proudly combining the leisurely element of the estate with it working farm elements that supported the house with food and income. Garden architecture still found a place among the circular walks that became popular or nestled into the wilder elements of the deep country estates such as Hackfall, Yorkshire which was mostly forest and glades. However, this harmonious relationship was broken by the prominence of Capability Brown, whose reputation was to sweep everything manmade from the landscape, including villages and farms, and hand it over entirely to nature.[73] Earlier landscapes were supposedly economic, not requiring the large staff and plant and accessories of the formal gardens, however the Brownian landscape posed a difficulty as Mr. Baynard discovered ‘the ground which formerly payed him one hundred and fifty pounds a year, now cost him two hundred pounds a year to keep it in tolerable’. Furthermore, Brown was keen to keep buildings off the landscape and screened necessary structures, such as stables and kitchen gardens wherever possible.[74]

Diana Balmori argues that rule-based neoclassical architecture and informal landscapes were paradoxical and necessitated ‘an architectural entity such as hermitage, grotto, or artificial ruin set into the landscape in order to articulate the relationship between art and nature’. Caves may have had sinister connotations at West Wycombe, but they were not an unusual form of eighteenth-century folly. They were often linked to a grotto, underwater shrine, spring or hermitage and several, such as Kent’s ‘Dido’s Cave’ at Esher, Surrey, oddly included a neoclassical portico. These mediatory ‘quasi-architectural, quasi-landscape’ structures were designed around elements of nature, for example, sham ruins expressed nature and time as the cause of decay, the moss and shell-grottoes, often housing fresh springs, and the roughly hewn hermitage which brought man closer to God.[75] Balmori’s argument contrasts with Fry who regards Palladianism and landscaping as cohesive and complimentary. Fry suggests formal, highly stylised, geometric gardens are suited to Baroque and earlier piles, but the aesthetically pleasing beauty and symmetry of the neoclassical complemented the natural charm of the landscape creating a serene and harmonious relationship.[76] It was also in keeping with the practice of the ancient Greeks who built favoured building temples in the countryside groves rather than cities where ‘The solitude of these shady retreats naturally tended to inspire the worshipper with awe and reverence ‘.[77] In his Epistle to Burlington (1731), Alexander Pope also identifies the proper setting for Palladian architecture to be the landscape, citing Stowe as a perfect example, however, Balmori interprets this as a phenomenon, based up Pope’s use of natural artifacts to disguise the fact his grotto and caves were manmade.[78]

The grotto was not an original solution to bridging architecture and nature as Balmori acknowledges by quoting Ovid’s Metamorphoses, ‘a well- shaded grotto, wrought by no artist’s hand. But Nature by her own cunning had imitated art, for she had shaped a native arch of the living rock and soft turf ‘.[79] Balmori’s modern mediation was, in fact, another form of classicism, which may explain the incongruity of elegant stone temples alongside irregular, moss- and shell-grottoes and caves. More relevantly to the eighteenth century, it is a form that complements devout Protestantism unlike the neoclassical shrines celebrating pagan gods, although Dashwood’s caves were clearly the antipathy of devoutness. Grottoes also symbolised the eighteenth-century evolution of collecting from the Renaissance cabinets of curiosity to taxonomy and the applied study of natural sciences. The juxtaposition of natural and manmade garden structures formed an outdoor wunderkammer and lost none of the wonder in bringing together naturalia and artificialiaand even relics kept within hermitages.[80] Grottoes were designed to emulate natural cave systems such as Wookey Hole, Somerset and where they lacked sufficient natural features such as ore and stalactites, these were acquired from natural sources, as demonstrated by the grottoes of the Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire (1757-1806) at Chatsworth and Pope at Twickenham. The ore veins installed at Chatsworth were so precious, the Duchess’s son employed night watchmen to guard the grotto.[81] In addition, artificial materials like looking-glass were added to enhance the natural elements, Henrietta Knight, Lady Luxborough noted using ‘looking-glass among [the moss] to reflect at a distance, will have a good effect from the Hall-door’.[82]

The motivation for striving to replicate nature as close as possible seems to be rooted in seemingly opposing Georgian principles, an expression of Protestant piety through the glorification of Gods work through nature rather than rituals like Catholics, and the individualist, pursuit of pleasure. J.H. Plumb explains that these aims were not so disparate ‘Men and women felt that happiness was to be found on earth as well as in heaven, that the works of a bountiful creator were to be enjoyed, not shunned’.[83] Just as Balmori finds architecture and nature aesthetically jarring, it was also religious problematic. Mimicking the Greek practice of temples in their garden groves, from which to contemplate the work of God went against the biblical injunction ‘Thou shalt not plant thee a grove of any trees near unto the altar of the LORD thy God.’[84] Neoclassicism was inextricably a form pf paganism, which was less of problem to the atheistic Order of St. Francis, but was it was raising commentary over the possible decline of Protestantism under the foreign and pagan influences of the ancient civilisations. The hermitage, which Florence Clarke D’hardemare describes as ‘reminiscent of fifteenth-century religious paintings of saints in well-composed rocky landscapes ‘,[85] was an alternative means of expressing a closeness to God and for contemplation and learning, although Queen Caroline’s hermitage at Kew was stocked with busts and books on science and philosophy and a salaried hermit to inhabit it, somewhat spoiling the religious effect.[86]

Female intervention in garden architecture appears to be particularly pleasure driven, even Caroline’s hermitage emulating Stowe’s Temple of British Worthies. Lady Luxborough’s intense landscaping and building at Barrells, served to while away her exile by her husband and rejuvenate both the neglected estate and wife.[87] At Cobham, Kent, a dainty gothic miniature dairy imitating an Italianate chapel to suit the medieval residence, was created by James Wyatt for Elizabeth Brownlow, Countess of Darnley. Dairies were popularised by Marie Antoinette’s Petite Trianon at Versailles (1762-1768) and featured at other estates such as Endsleigh, Dorset, for the Duchess of Bedford. Evocative of the hermitage, both dairies looked out across the picturesque grounds and released the faux-dairymaids from their consumerist desires while role-playing the simple life of self-sufficiency, something their gender and rank otherwise denied them. Another garden-related craft regarded as female was shell-work and moss and shell grottoes were often regarded to be feminine spaces.[88] The grotto was classically related to nymphs and Venus and often featured a naked ‘crouching venus’ caught in the act of bathing, which made them attractive spaces to men too.

The amount of work invested in the development of garden landscapes and buildings concurs with Plumb’s view that most Georgians did not see their landscapes and temples as moral decline, stating ‘Happiness was deepest when linked with self-improvement, either through the social arts or through the enjoyment of nature in all its manifestations’.[89] To the Georgian mind, they were improving the landscape, as well as themselves, to be most virtuous it could be and using garden architecture to express self-improvement through studying the classics or doing the Grand Tour. At Dawley, Lord Bolingbroke took his expression of classical knowledge to the extremes, building a temple over a spring and adding river gods and nymphs. Springs were sacred to the Muses who were popular patrons of arts, music, and sciences in the Georgian era, featuring in garden architecture, interior designs and decorative arts.[90] The ancients especially celebrated the divinity of nature and their gods were personifications of its elements, and Georgian gardens equally filled up with statues such as Flora, Ceres, Bacchus and Venus who all represented fertility and joy, bringing the promise of happy longevity to the family estate. The Georgian pursuit of happiness became embroiled within consumerism and Plumb observes,

happiness became less private, less a state of the soul, a personal relationship with God, than something visible to one’s neighbours. The pursuit of happiness was entangled in social emulation; it, therefore, became competitive; and competition requires money and time as well as desire ‘.[91]

Garden architecture became as much about consumerism and capitalism, as it did about simplicity and returning to nature.

In the century regarded to have given birth to mass consumerism, ornamental garden architecture was also constructed because it was needed for a purpose and other people had it. Stowe is among the earliest examples of the Georgian vogue for garden architecture, so it is perceivable by influential on later gardens. Emulation is not always a form of flattery, it can also be an egotistical display of doing something better or a parody as demonstrated at West Wycombe.[92] The poet, William Shenstone of The Leasowes, complained bitterly about Lyttleton’s development at neighbouring Hagley Park because he believed it was exploiting his ideas, not Stowe’s, which Lyttelton ‘could realise more readily because of his wealth’.[93] Landscape architects were shared among the peerage across England and became the catalysts for dissemination of style, although some, like Lancelot ‘Capability’ Brown, offered a restricted canon of capabilities and particular aesthetic preference.[94] Architects and landscape designers became professions as opposed to gentlemen dabblers giving them authority over the landscape. Studying architecture, even as an amateur, remained important to appear erudite as conveyed by Henry Hoare II at Stourhead, Wiltshire who used his garden architecture to express ‘that knowledge which distinguishes only the gentleman from the vulgar’.[95] Tourist guides also contributed to the dispersion of ideas in England and abroad, Benton Seeley produced guides to country estates between 1744 and 1827 and Gilpin’s Observations series on the picturesque, published between 1768 and 1809, helped popularise the ‘English Tour’ of country seats.[96]

In reflecting on the prominence of neoclassicism in garden architecture, which was styled on harmonious principals and originated from the glades of Greece, it is hard to concur fully with Balmori that an intermediate structure was required. This problem has exacerbated the fact that few elements in the landscape, from grottoes to trees were truly ever natural and always subject to some form of human control. This provides a political allusion to the changing attitudes in managing the country and managing the country garden over the century. Garden architecture popularity declines with the arrival of the Brownian landscape but there was also an undeniable passion for experiencing nature and the simpler way of life in which garden architecture played an important role. The juxtaposition of architecture and organic gardens implies that it may have been regarded as a sort of curiosity cabinet and encouraged outdoor studies of natural sciences, horticulture, and architecture. Women too found their niche, in which to contribute to the creation of the landscape, in an otherwise male-dominated world of landscapes and architecture which became a highly regarded profession instead of amateur pursuit by the end of the century.

CONCLUSION

‘all gardens and houses wear a tiresome resemblance’[97]

This dissertation has been successful in identifying a variety of reasons why follies were so popular in the eighteenth century and what they expressed about the culture of the eighteenth century. It has demonstrated that garden architecture has been used to imply political ideology, satirical humour and to be closer to nature and God, although at times they were simply following the trend. The architectural style and the type of folly were secular and adaptable to whatever message was required of them, supporting Carole Fry and Howard Colvin’s arguments that neoclassical architecture could be political, but it was not tied to any one party. Political application revealed that neoclassical structures could be interpreted metaphorically, demonstrating the idealisation of a golden era of democracy. Other times, it was the materials used that revealed the intent of the builder, as in the grottoes and hermitages that sought to replicate nature as close as possible. These appeared to be the Georgian antidote to an overload of neoclassical architecture in gardens, which began to be criticised for placing pagan deities above British Protestantism. Moreover, they were for experiencing the delights of God’s nature and creating an outdoor wunderkammer to inspire study and contemplation. Diana Balmori’s argument that follies are mediatory creations was less convincing considering that few follies attempted to mimic nature and those that did were heavily influenced by human intervention.

Follies are unique in architectural history because they can be created as temporary statements of beliefs that are easily lost to time. Overwhelmingly they demonstrated that Georgian architects were most adept at creating the perfect façade to disguise their imperfect society. In terms of garden history, on their own and as part of the wider landscape, they successfully revealed attitudes to nature and the evolution of the garden in the eighteenth century. As art, they provide a rich scope of visual material in structure ands related culture. The study of Venus demonstrated the extent to which the goddess was pervasive in the arts and vernacular for her allusions to women and to sex, who paled by her comparison. Drawing on different genres of history has created an enriched and fascinating history to follies and drawn out a wealth of hidden information that deserves a seminal text of its own.

Appendix: Illustrations

![C:UsersBlytheAppDataLocalMicrosoftWindowsINetCacheContent.Wordvitruvius-britannicus-c1720-architectural-print.-hall-barn-near-beacons-field-[2]-75621-p.jpg](https://images.ukdissertations.com/15/0012766.001.jpg)

Fig. 1. Garden Room, 1724, Hall Barn, Beaconsfield. Source: Colen Campbell, Vitruvius Britannicus, Vol. III. (1725), C3, PL. 49.

Fig. 2. Vanbrugh’s garden temple (c.1717) at Eastbury, Dorset. Source: Colen Campbell, Vitruvius Britannicus, Vol. III. (1725), C3, PL. 18.

![C:UsersBlytheAppDataLocalMicrosoftWindowsINetCacheContent.Wordvitruvius-britannicus-c1720-architectural-print.-gunnersbury-house-london-75519-p[ekm]270x202[ekm].jpg](https://images.ukdissertations.com/15/0012766.003.jpg)

Fig. 3. Gunnersbury Park, Middlesex. Source: Colen Campbell, Vitruvius Britannicus, Vol. I. (1725), C1, PL. 18.

Fig. 4. Temples of British Worthies. Source: Trevor Rickard, Geograph.org, 22 September 2010 [accessed 17 April 2017].

Fig. 5. Temple of Ancient Virtue, Stowe. Source: National Trust.

Fig. 6. Temple and Parlour of Venus, West Wycombe, c.1740s. Source: Robbob Tun, Panoramio, 18 August 2013 [accessed 17 April 2017].

Fig. 7. Venus de’ Medici. Fratelli Alinari (photographer ), 1856 – 1872, Albumen silver print, 33 x 25.2 cm. J. Paul Getty Museum, 84.XM.508.2.

Fig. 8. Sir Francis Dashwood Worshipping Venus, William Platt, after William Hogarth, Late C18. Engraving, paper, 378 millimetres x 253 millimetres. British Museum, 1858,0417.476.

Fig. 10. Chatsworth, 1699. Kip and Knyff. Source: Devonshire, Duchess of, The Garden at Chatworth (London: Frances Lincoln, 1999)

Bibliography: Primary Sources

Books

‘A Monk of the Order of St. Francis’, Nocturnal Revels (London, 1779)

Alberti, Leon Battista, The Ten Books of Architecture, Giacomo Leoni, transl. (London, 1726)

A Descriptive Catalogue of Coade’s Artificial Stone Manufactory (1784)

Burnaby, William, transl., The Satyricon of Petronius Arbiter (London: Aeterna, 2010)

Campbell, Colen, Vitruvius Britannicus: The Classic of Eighteenth-Century British Architecture(New York: Dover, [1715] 2007)

Cleland, John, Memoirs of a Woman of Pleasure (1749)

Congreve, William, ‘Of Improving the Present Time’ (1728)

The Gentleman’s Magazine, XII (March 1743)

Garth, Samuel, ‘Claremont’ (1715)

Gilpin, William, A Dialogue upon the Gardens of the Right Honourable the Lord Viscount Cobham at Stow in Buckinghamshire (1748)

—, Observations of … ([series] 1768-1809)

Grose, Francis, The Antiquities of England and Wales, Volume I, (London: S. Hooper, [Second Edition] 1783)

Luxborough, Henrietta Knight, Letters Written by the Late Right Honourable Lady Luxborough to William Shenstone Esq (London: J. Dodsley, 1775)

Lewis, Matthew, The Monk, (Waterford, 1796)

Locke, John, Two Treatises of Government (1689)

Palladio, Andrea, The Architecture of Palladio in Four Books, Giacomo Leoni, ed. (London, 1715)

Pope, Alexander, An Epistle to the Right Honourable Richard Earl of Burlington, Occasion’d by his Publishing Palladio’s Designs of the Baths, Arches, Theatres, &c. of Ancient Rome (1731)

Richardson, Samuel, Clarissa, or the History of a Young Lady (London, 1748)

West, Gilbert, ‘Stowe, The Gardens of the Right Honourable Richard Viscount Cobham’ (1732)

Wilkes, John, ‘Curious Description of West Wycombe Church, &c.,’ The New Foundling Hospital for Wit (London, 1786), pp. 75-80

—-, The North Briton XLVI, Numbers Complete, Volume IV (London, 1772)

Buildings

Alexander Pope’s Grotto, Twickenham (demolished, remnant)

Caroline’s Hermitage, Hampton Court Garden (demolished)

Cobham Dairy, Kent, The Landmark Trust (extant, under renovation)

Dashwood Mausoleum, West Wycombe Hill, privately owned (extant, missing elements)

Dawley House, Harlington, private (mostly demolished)

Duchess of Devonshire’s Grotto, Chatsworth (extant)

Endsleigh Dairy, Dorset, The Landmark Trust (extant, holiday let)

Glenfinnan Tower, Argyllshire, Glenfinnan Monument & Visitor Centre (extant)

Golden Globe and Church of St. Lawrence, West Wycombe Hill, privately owned (extant)

Greenwich Hospital, now Royal Navy College (extant)

Gunnersbury Park, Ealing Council, some private (mostly extant)

Hall Barn, Beaconsfield, privately owned (some extant)

Hackfall, Yorkshire, Hackfall Trust (some extant, some ruined)

St. Pauls Cathedral, St Paul’s Cathedral Enterprises (extant)

Stourhead, Wiltshire, National Trust (extant)

Stowe Gardens, National Trust (some structures extant)

Temple of Venus, Parlour of Venus, West Wycombe, National Trust/privately owned (demolished and rebuilt)

Tottenham Park and Savernake Forest, private (extant)

Traquair House, Peeblesshire, Traquair House Trust (extant)

West Wycombe Caves, West Wycombe, privately owned (extant, reduced)

Wilbury House, Wiltshire, private (grounds demolished, house extant)

Bibliography: Secondary Sources

Books

Barnard, Toby and Jane Clark, eds., Lord Burlington: Architecture, Art and Life (London: Hambledon Press, 1995)

Barton Stuart, Monumental Follies: An Exposition on the Eccentric Edifices of Britain Worthing: Lyle, 1972)

Belk, Russell W., Collecting in a Consumer Society (Abingdon: Routledge, 1995)

Berens, E. M., The Myths and Legends of Ancient Greece and Rome (London: Blackie & Son, 1880)

Bernhardt, Peter, Gods and Goddesses in the Garden: Greco-Roman Mythology and the Scientific Names of Plants (New Jersey: Rutgers, 2008)

Bevington, Michael, Stowe: The People and the Place (London: Scala Publishers, 2011)

Bleackley, Horace, Life of John Wilkes (London: John Lane, 1917)

Bonnard, G. A., ed., Gibbon’s Journey from Geneva to Rome (London: Thomas Nelson, 1961),

Brown, Jane, The Pursuit of Paradise: A Social History of Gardens and Gardening (London: HarperCollins, 2000)

Calder, Martin, ed., Experiencing the Garden in the Eighteenth Century (Bern: Peter Lang, 2006)

Cruikshank, Dan, Adventures in Architecture (London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2008)

—, A Guide to the Georgian Buildings of British & Ireland (London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1985)

Dashwood, Sir Francis, Bt., The Dashwood Mausoleum (n.d.)

—, West Wycombe Caves (n.d.)

Denvir, Bernard, The Eighteenth Century: Art, Design and Society, 1689-1789

Devonshire, Duchess of, The Garden at Chatworth (London: Frances Lincoln, 1999)

Dickinson, H. T., ed., Politics and Literature in the Eighteenth Century (London: J. M. Dent & Sons, 1974)

Foucault, Michel, The History of Sexuality: An Introduction, transl. Robert Hurley (London, 1979)

Girouard, Mark, Life in the English Country House (Harmondsworth, Middlesex: Penguin, [1978] 1980)

Hammond, Paul, ed., Selected Prose of Alexander Pope, (Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1987)

Harris, John, The Palladian Revival: Lord Burlington, His Villa and Garden at Chiswick (New Haven: Yale UP, 1995)

Headley, Gwyn and Wim Meulenkamp, Follies, Grottoes and Garden Buildings (London: Aurum Press, 1999)

Hitchcock, Tim, English Sexualities, 1700-1800 (Basingstoke: Palgrave, 1997)

Hopkins, Andrew, Italian Architecture from Michelangelo to Borromini (London: Thames & Hudson, 2002)

Hussey, Christopher, English Country Houses: Early Georgian, 1715-1760 (Country Life, 1955)

Jackson-Stops, Gervase and James Pipkin, The Country House Garden: A Grand Tour (London: Pavilion, 1987)

Llewellyn, Roddy, Elegance & Eccentricity: The Ornamental & Architectural Features of Historic British Gardens (London: Ward Lock, 1989)

MacIntosh, Christopher, Gardens of the Gods: Myth, Magic and Meaning in Horticulture: Myth, Magic and Meaning (London: I.B. Tauris & Co, 2005)

Marshall, Dorothy, Eighteenth Century England (London: Longman, 1962)

Milne, Norman C., Libertines and Harlots: From 1600–1836, (Northampton: Paragon Publishing, 2014)

Mowl, Timothy, William Kent: Architect, Designer, Opportunist (London: Pimlico, 2006)

Plumb, J.H, Georgian Delights (London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1980)

Quenell, Peter, Caroline of England: An Augustan Portrait (London: Collins, 1939)

Ridgeway, Christopher and Robert Williams, eds.. Sir John Vanbrugh and Landscape Architecture in Baroque England (Stroud: Sutton Publishing, 2000)

Shoemaker, Robert B., Gender in English Society, 1650-1850 (London: Routledge, 1998)

Tavernor, Robert, Palladio and Palladianism (London: Thames & Hudson, 1991)

Van der Kiste, John, King George II and Queen Caroline (History Press, 2013) Kindle ebook

Vickery, Amanda, Behind Closed Doors (New Haven: Yale UP, 2009)

Wroth, Warwick, The London Pleasure Gardens of the Eighteenth Century (Connecticut: Archon Books, [1896] 1979)

Zigarovich, Jolene, ed., Sex and Death in Eighteenth-Century Literature (Abingdon: Routledge, 2013)

Chapters in Edited Books

Frith, Wendy, ‘Sexuality and Politics in the Gardens at West Wycombe and Medmenham Abbey’, Bourgeois and Aristocratic Cultural Encounters in Garden Art, 1550–1850 (Washington: Dumbarton Oaks, 2002), pp. 286-309

Jackson-Stops, Gervase, ‘Introduction,’ in Follies and Pleasure Pavilions, by George Mott, (London: Pavilion Books, 1989), pp. 8-25

Journals & Chapters

Adshead, David, ‘The Design and Building of the Gothic Folly at Wimpole, Cambridgeshire’, The Burlington Magazine, 140:1139 (1998), pp. 76-84

Balmori, Diana, ‘Architecture, Landscape, and the Intermediate Structure’, Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians, 50:1 (1991), pp.38-56

Bending, Stephen, ‘Re-Reading the Eighteenth-Century English Landscape Garden’, Huntington Library Quarterly, 55:3 (1992), pp. 379-399

Clark, Jan, ‘An Amateur Artist’s Sketching Tour of Late Eighteenth-Century English Gardens’ Garden History, 41:2 (2013), pp. 209-223

Clarke, George, ‘The Moving Temples of Stowe: Aesthetics of Change in an English Landscape over Four Generations’, Huntington Library Quarterly, 55:3 (1992), pp. 501-509

Coffin, David R., ‘Venus in the Eighteenth-Century English Garden’, Garden History, 28:2 (2000), pp. 173-193

Colton, Judith, ‘Merlin’s Cave and Queen Caroline: Garden Art as Political Propaganda’, Eighteenth-Century Studies, 10:1 (1976), pp. 1-20

Cox, Oliver, ‘A Mistaken Iconography? Eighteenth-Century Visitor Accounts of Stourhead’, Garden History, 40:1 (2012), pp. 98-116

Cosgrove, Denis, ‘Prospect, Perspective and the Evolution of the Landscape Idea’, Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 10:1 (1985), pp. 45-62

Dabhoiwala, Faramerz, ‘Lust and Liberty’, Past & Present, 207 (2010), pp. 89-179

D’hardemare, Florence Clarke, ‘The Follies of a King-Duke’, Garden History, 37:1 (2009), pp. 56-67