Influence of Tim Burton's Filmmaking Style on Horror/Fantasy Films

Info: 12987 words (52 pages) Dissertation

Published: 6th Sep 2021

Tagged: Film Studies

German Expressionism and the ‘Burtonesque’ style of filmmaking: An examination of contemporary productions of the horror/fantasy genre in cinema

ABSTRACT

This dissertation addresses the question of whether director Tim Burton’s unique, and gothic filmmaking style has influenced the production of horror/fantasy films, within the Hollywood production system. The research reviews the characteristics of German Expressionism in cinema and its influences on future directors, using a qualitative approach, and examines the influences of Burton’s work on the sample films. The sample films are analysed with the method of semiotic analysis, which enables the researcher to interpret the signs detected in the films’ texts in relation to Burton’s filmmaking style. The results conclude that German Expressionism has been the starting point for the genesis of the horror/fantasy genre in cinema and that Burton’s aesthetics have influenced the development of this genre in contemporary filmmaking.

Contents

CHAPTER 1: Introduction

1.1 About the inspiration

1.2 About the research

CHAPTER 2: Literature Review

2.1 Expressionism and the ‘Burtonesque’ style

CHAPTER 3: Methodology

3.1 Research design

3.2 Semiotic Analysis

3.3 Samples

CHAPTER 4: Analysis and Discussion

4.1 About this chapter

4.2 Pan’s Labyrinth

4.3 The Addams Family

CHAPTER 5: Limitations and Conclusions

5.1 Limitations

References

Appendix

Figures

CHAPTER 1: Introduction

“No matter what anybody tells you, words and ideas can change the world.”

Dead Poets Society, 1989

1.1 About the inspiration

The art of storytelling, has a unique power of inspiring and motivating people. As a Media and Communications student, I have been taught about film history and analysis, from which a specific movement caught my attention. German expressionism; with its eerie and avant-garde elements, and its relation to the socio-political events of the country. While researching more about it, I found some similarities between the movement’s characteristics and Tim Burton’s films. While fairytales are often striped of their dark elements, Burton manages to illustrate those aspects in ways that can be enjoyed by both children and adults. Hence, as a fan of anything that challenges the mainstream, I was immediately intrigued to combine my love for cinema, history and Tim Burton with my dissertation project.

1.2 About the research

While reviewing several research on the historical development of Expressionism in Germany, its application in the medium of cinema, and its characteristics, this paper will develop a case study to identify the influences of expressionism in Burton’s work. Additionally, it will utilise a qualitative approach to examine whether his filmmaking style has extensively influenced the ways in which films, of the same genre, are being produced within the Hollywood production system.

In other words, this paper aims to find out about:

- the historical development of Expressionism in German cinema.

- German Expressionism’s characteristics (specifically in film).

- how Tim Burton’s style has been influenced

- how his style has influenced the production films in the same genre

Accordingly, examining how Burton’s style has influenced other productions can facilitate to better situate his filmmaking style as one of a contemporary auteur’s, which extensively challenges the Hollywood mainstream filmmaking style, while working within it.

CHAPTER 2: Literature Review

Expressionism is a term that has been used to characterise several things, from art to theatre. Its actual definition though, has been difficult to coin, as its historical development is subject for debate amongst film historians. This piece, will be discussing Expressionism’s development and application, specifically to the medium of cinema, while reviewing the relevant literature focused on the movement. The review, intends to formulate a logical delineation of how the movement was developed in Germany, and how its applications in film relate to the research’s objective.

2.1 Expressionism

It is difficult to ascertain the genesis of Expressionism, since the term has been used long before the movement was developed. Critic Peter Gay notes that Frühlings Erwachen (1891) is one of the first theatre plays to include expressionist ideas (2001). Early nineteenth century, was a very complicated time for Germany, as well as the rest of the world, and eventually led to World War I. As a war fueled by unclear motives and attempts for maintaining power by all European countries, it is easy to imagine the harsh and dark reality of people’s lives. Revolutionary works from people like Picasso, Einstein or Freud were overshadowed by the catastrophes of war; which surprisingly, proved to be ideal for the development of Expressionism. As part of Modernism, Expressionism came to challenge the literal portrayal of the world and proposed new ways of portraying emotions and mental states (Sokel, 1959). The movement became of particular importance in Germany, where the ground was ideal for its flourishment, especially after the country’s humiliation with the results of the Treaty of Versailles in 1919 (Wexman, 2002)

Firstly, utilised by painters in artist groups such as Die Brücke and Der blaue Reiter, it soon expanded to poetry and literature, mostly published in avant-garde periodicals, like Die Aktion or Der Stum (Sokel, 1959). The post-war society was in desperate need for escapism, and since foreign films had been banned from the country in 1916 (Thompson & Bordwell, 2009), theatre plays were of extreme demand.

All the death and destruction seen throughout Europe in that period led most people to seek socio-political change (Clarke, 2002). Expressionist artists tried to portray those feelings through bold, bright tones in their paintings, as well as exaggerated performances in their plays with one goal; to move as far away from the objectively perceived reality as possible (Weisstein, 1981). Gay notes that painters took the simple colours and the distortion of the human figure far beyond the norm (2001), while focusing on their subjectivity and psychological state. The most ingenious expressionists in his opinion, were the playwrights, whose works were breaking all the rules. In his opinion, those plays were made as loud cries for help, with a direct demand for change and information (2001).

2.2 Expressionism and German Cinema

Expressionist theatre therefore, combined with the expressionist painting styles have been the set-in stones which later influenced the German Expressionist filmmakers. Through all the chaos and imbalance, film advanced the sophistication of theatre, making German cinema of the 1920s one of the most revolutionary and successful cinema industries in the world (Dejonge, 1978).

In his book ‘The UFA Story: A History of Germany’s Greatest Film Company, 1918-1945’.Kreimeier Klaus provides a thorough discussion on Ufa’s development, success, and eventual bankruptcy during The Great Depression. The company, which was founded in 1917, experienced a golden age from the 1920s to the 1940s, thanks to its successful productions of expressionist films (Kreimeier, 1998). By the time the Nazis rose to power though, it went under Josef Goebbels’s control, who viewed expressionism as ‘the programmatic deformation of reality’ (Braun, 1996, p.273) causing many directors to leave Germany and continue their careers elsewhere, mostly in Hollywood (Clarke, 2002).

With the expressionist artistic body leaving Germany, the movement gradually came to an end. Even though it was short-lived, it has a greater significance which ultimately reflects the German culture during those fast-paced, moments of history. It was more than just a unique style of creating art. It was a comprehensive movement that ‘extended into more areas of human intellectual endeavor’ fighting to implement change in all aspects of society (Boorman, 1986).

Ian Roberts (2008) argues that German cinema was the medium through which Expressionism was manifested in to the world. Indeed, film historians acknowledge that the starting point of German Expressionism in film began with the release of Robert Wiene’s ‘The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari’ in 1920. Utilising built-in set designs inspired from expressionist paintings, as well as extraordinary performances and lighting, the film immediately captured the audiences’ attention.

After Caligari was released and enjoyed by many, other German filmmakers were inspired by its dark themes and the new potentials for expression it introduced.

2.3 Approaches to German Expressionism in Weimar Germany

For anyone interested in studying this movement, the main sources of information about it are the works of two critics who lived during that period. Kracauer Siegfried’s ‘From Caligari to Hitler’ (1947) and Eisner Lotte’s ‘The Haunted Screen’ (1952). Both texts have become essential in the study of German Expressionism for their unique approaches on the films produced at the time. Each critic provides their own critical evaluation on the films’ relations to society, culture, and politics, to make the German landscape of the nineteenth century more comprehensible to foreign audiences.

As Kracauer stated, there were notable gaps in people’s comprehension of German history, from the Great War to Hitler’s ultimate rise to (1947), and he argued that films carry signs of hidden truths that could be reflective of a nation’s mentality. He divided his study into four sections, beginning with the appearance of Caligari and ending with the period before Hitler’s rise to power (1930-1933). He asserted that the films of each period reiterate themes which reflect the country’s socio-political realities and their relations with people’s psychological states.

Even though his study is considered a landmark for the study of Weimar Germany, Roberts (2008) argues that it has neglected some major films of the movement, while providing unnecessary attention to others, in Kracauer’s attempt to better prove his point; that German cinema was a symptom of German dysphoria for the aftermaths of war.

Similarly, Thomas Elsaesser, even though he acknowledges the importance of Kracauer’s work argues that, along with Eisner’s work, they become a ‘Moebius strip’, a shape of thought which feeds upon itself, taking what it explores as given (2002).

Eisner’s study attempted ‘to throw light on some of the intellectual, artistic, and technical developments which the German cinema underwent during [those] momentous years’ (1952, p.8). She displayed a thorough knowledge of German drama and literature and located the expressionist artistic influences in the films of directors such as Fritz Lang or F.W. Murnau. When commenting on Eisner’s work, Telotte (2005), states that she viewed German Expressionism as a reflection of German romanticism, which had its focus on magical and mystical themes, and that those themes could be translated as a rejection of rules and a deliberate refusal to reflect reality.

Her book examines in detail the principal films of the period and discusses the tremendous influence of theatre on them, especially the plays of Max Reinhardt. Eisner divided the principal films into two categories based on their concept. One category for the highly ‘romantic’ films and another for the ‘modern’ ones. She argued that most films produced up to 1924 were influenced by romantic literature such as the works of Edgar Allan Poe and Brian Stoker and experimented with dark motifs (e.g. the Doppelganger or the mad genius motifs) to bring eerie and fantastical pictures to life. Additionally, she mentioned the shift from the romantic to the modern category, which articulated themes related to social injustice, and industrialisation.

2.4 German Expressionism, films and Caligari

Rudolf Kurtz, a leading participant of the expressionist movement, defined expressionism long before Eisner and Kracauer and described it, not as a genre, but as a manifestation of the time’s crisis in art and as a general state of mind (Kurtz et al., 2016). In his point of view, the movement was not a style of filmmaking, but a matter of applied expressionist techniques. This view is also supported by Barlow, who suggests that Caligari is the purest example of expressionism in film that even influenced a unique style called ‘Caligarism’. The films which were influenced or created in a similar spirit as Caligari, belong in the style of Caligarism, while all the others simply utilise expressionist techniques (1982).

While both Kracauer and Eisner’s studies employ different approaches on the examination of Weimar Germany, they both put significant emphasis on Caligari’s importance in defining German Expressionism in cinema. They both argue, that for a film to be considered expressionist, it needs to include certain motifs, which were evidenced, for the first time, in Caligari. In Robert’s (2008) view, the utilisation of violent contrasts and love for shadows and hard light made the elements of madness, duplicity, and disturbing psychological depths become the recurring motifs in any film that was expressionistic.

2.5 Motifs and aesthetics

Still being part of the Silent Era of cinema, expressionist filmmakers had to heavily rely on symbolism and artistic imagery to tell their stories. Focusing on their subjectivity, they tried to express their feelings using distortion and paranoia, usually depicted in their extreme stylisation of sets, which were built-in and painted to resemble expressionist paintings (Guynn, 2011). As Telotte (2005) states, the narrative themes of films -with Caligari as their main influence- were expressed through fantasy and dream-like sequences, a state of madness and irrational thought, as well as a sense of not being certain of what is real and what is not. As for the thematical elements of the films, directors not only used the expressionist sets to express their subjectivity, but also experimented with distortions of space, exaggerated or choreographed acting, and heavy use of shadows and chiaroscuro lighting, that emphasised the sets’ oblique lines, the actors’ makeup and the contrasts between light and dark areas (Kracauer, 1947; Eisner, 1952; Telotte, 2005; Guynn, 2011).

These dark themes of insanity, death, and fatality that translated prevalently into Caligari’s mise-en-scéne and narrative, became notable within the movement, as it countered the principle of realism and portrayed Germany’s inner realities. It was extremely important that the films paid attention to the artistic background, since all the elements of the film had to intertwine with each other, each of them playing an equal part in the communication of meaning (Benyahia et.al. 2009).

Discussions about expressionist film, in every occasion, begin with Caligari, not for popularising cinematic expressionism, but also because its story attacked the ‘absolute authority’, which had brought the horrors of the Great War on people (Kracauer, 1947). The portrayal of the manipulated Cesare, who commits murders when hypnotised by the Dr. Caligari, symbolises the individual who is forced to fight, and potentially kill or be killed, for a cause they did not have the power to question (Telotte, 2005). Another reason is, Caligari’s adoption of the style of expressionist stage plays. For the first time, film actors literally made themselves ‘part of the decoration’ (Roberts, 2008, p.24) to enhance the viewer’s confusion.

According to Barlow (1982) expressionism in Caligari was not a technique but ‘part of the film’s vision’ (p.101) that served to introduce the boundaries between reality and dream, sanity and insanity, as well as an individual’s – and extensively a nation’s- descent into chaos and madness.

As argued by Paul Coates, ‘the film image is an alienated reflection – an imitation of life perilously similar to the original’ (1985, p.120). The Doppelgänger motif has been evidenced in all arts and was particularly popularised during its utilisation in the expressionist films (Barlow, 1982). Many films, including Caligari, dealt formally and thematically with this concept, through themes like split personas, immortality, whore/Madonna complexes, or visual motifs such as chiaroscuro lighting, mirrors or character deterioration (Scheunemann, 2003). This motif introduced a gothic sense of reality, and the sense of losing something as familiar as one’s reflection (Barlow, 1982).

2.6 End of movement and ‘expressionist heritage’

The same way Caligari symbolises the launch of cinematic expressionism, Fritz Lang’s Metropolis (1927) is thought of by many film historians as the last film of the movement since it was the last film with expressionist elements to be produced by Ufa (Kracauer, 1947; Coates, 1991). The film uses dream sequences, visions, proportionless buildings and expressionist mise-en scéne in general. According to Barlow, Metropolis is ‘the most representative [film] of the themes of expressionism’, while ‘Caligari is the finest example of expressionist style’ (1982, p.122).

This style was later transferred, with the emigration of many expressionist filmmakers, to other countries. (Eisner, 1947). Wexman (2002), argues that the Germanic influence was evidenced for decades on American filmmaking style’s use of lighting, camera movement and aesthetics. Specifically, she discusses how the horror and film noir genres were using expressionistic techniques, from lighting, makeup, and special effects to ideas of dark, ‘distorted psyches’ in their narratives (p.59).

Film studios, like Universal Pictures, began a successful series of productions of gothic, horror films which relied on the expressionist element of grotesque and macabre (Barlow, 1982, Wexman, 2002). Soon, the German filmmakers’ participation in the American productions led to the development of what is now known as the ‘film noir’ genre where the shadows and lighting styles of German expressionism were utilised to refine the dark atmospheres of the films, whereas city life and realism replaced the fantastical and supernatural elements, to better accommodate the American and Hollywood trends (Spicer, 2002).

2.7 Relation to auteur theory

Barlow characterised these influences as the ‘expressionist heritage’ (1982, p.169) and they have been the fertile ground for the flourishment of the imaginings of famous auteurs. The origins of auteurism can be traced back during the French New Wave movement when Francois Truffaut published his views on the theory at the Cahiers du Cinema in 1954. He argued that auteurs can transform their films into expressions of their personalities (Caughie, 2013). The theory basically looks at the director of a film as its author (Gerstner & Staiger, 2003). Also, the film is viewed as the auteur’s artistic vision, with recurring, themes recognizable by the viewer (Grant, 2008).

Modern cinema still borrows elements from German Expressionism, even though the term has always been difficult to fully define or trace historically, due to its short period of life and its application to so many other filmmaking styles. As Barlow (1982) states, the term ‘expressionistic’ can be validly applied ‘wherever distortion occurs as part of an ambience of anxiety and internal conflict’ (p.205).

2.8 Expressionism and the ‘Burtonesque’ style

According to R.S. Furness (1973), an expressionist artist seems to respond to a ‘need to point beyond’, to wish to overtake reality and suggest that the world’s meaning ‘might lie beyond its purely external appearance’ (p.20).

With an oeuvre of more than thirteen films, he is a director that is often discussed and debated as far as his style, influences and artistic ideas are concerned (McMahon 2014). Born and raised in Burbank, California, Burton has always been part of the suburbanised Hollywood area, where he spent most of his time growing up. His love for the arts came at a young age, when his vivid imagination motivated him to start drawing and eventually enrolling at the California Institute of the Arts. By 1979, Disney recognised his talent and hired him to work as an animator, even though his style did not exactly blend with the Disney concept. Despite that though, his career has been developed within the regular Hollywood system of filmmaking. His unique imaginings and his persistence on the portrayal of his style though, have made him a divergent in the industry. Paul Woods, trying to define Burton’s style, states that his films have a ‘gothic-infantile aesthetic’, and ‘a macabre cartoonishness’ that make his work surrealistic and expressionistic (2002, p.5).

From a young age, pop culture fascinated Burton, and he was especially inspired by horror, science-fiction, animation, and children’s literature (especially Dr. Seuss), (Salisbury et.al. 2006), and he continues to transfer the ideas from his childhood into his body of work as an adult. The same feeling of being a misunderstood outsider, which he experienced during his childhood, is evidenced in the portrayal of his characters, who are usually unique individuals, operating in their own ways within societies of conformity and duality (Salisbury et.al, 2006).

His unique protagonists, his gothic narratives and portrayals of the expressionistic otherness, are described as the ‘Burtonesque’ style (Magliozzi & He, 2009). Within his films exist juxtapositions of ordinary and fantastical worlds, which emphasise the duality and contradiction which he, as a director, also embodies. He is celebrated for his successes by many, but he is also criticised by others; he is part of the Hollywood system, but he manages to maintain a respectful distance from it.

Aurélien Ferenczi (2010) finds that there is a consistency of funny, dark and scary elements in Burton’s films, which all lead back to their owner. On a visual level, his characters tend to appear distorted in size, while on a psychological level, his films touch on elements of fear or adolescent constrains and pressures by society. The characters’ inner troubles are reflected through their exaggerated features, all under the usual gothic influence.

Thus, in a way, Burton’s iconic gothic style, soaked with expressionist elements, has developed into his personal filmmaking style; that gives him a unique mark of authenticity within the film industry (Weinstock, 2013).

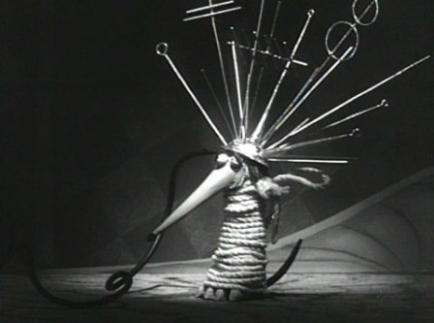

During his years working at Disney, Burton was given the freedom to produce and release his first film, a short stop-motion animation called ‘Vincent’ (1982). The story is about a young boy named Vincent Malloy, who is obsessed with the work of Edgar Allan Poe and Vincent Price. In just six minutes, the film takes the viewer through a summary of the Burtonesque style. As the narrative moves along the two realities of Vincent’s life; his normal life as a young boy and his imagined reality of torment, Burton invites the audience to not only sense the film on a rational level, but mostly on an emotional one. The extreme contrasts of black and white, as well as the utilisation of chiaroscuro lighting make the expressionistic aesthetic of his style more profound (see figures 1 & 2).

Just like the rejections of authority in the expressionist films of the twentieth century, Burton portrays young Vincent not only rejecting the reality his mother bestows upon him, but also the way society recognises the ways people should behave in specific age bunches.

There are similarities between Vincent and Caligari, such as the portrayal of madness and illusions, the simultaneous existence of two distinct realities, or the mise-en-scéne of ‘disproportionate’ and ‘elongated’ forms (Weinstock, 2013, p.5). Vincent’s reality is understood by the viewer when the environment shifts, and defies logic; existing and operating in certain ways as to express the character’s emotions and state of mind (Magliozzi & He, 2009). (see figure 3)

For example, in a scene where Vincent is sent to his room by his mother, he begins to feel trapped and tormented in his bedroom/prison. His mother comes in the room and tells him that his torment is only in his head and he should go out to have some real fun. In that moment, he ultimately rejects his mother’s reality, viewing it as a mere distraction from his imagined world. He begins to feel the walls moving closer to him, while the background appears distorted and macabre. Skeleton hands reach for him through the cracked walls and he eventually falls to the floor believing himself to be dead. Apart from the references to Poe’s work, Vincent makes use of what Caligari first introduced. The indistinguishable nature of anything in the mise-en-scéne, to achieve the portrayal of madness and psychosis of the individual, who has lost control of their surroundings. To add to this comparison, Burton himself has described Vincent as a meeting of Caligari and Ray Harryhausen (an animator who Burton has been a fan of for years), although, as he stated, the film was also inspired by the work of Dr. Seuss (Smith & Matthews, 2007).

In short, the same way the thematic and narrative visuals of Caligari were influenced by the arts of its era, so were contemporary art, literature and filmmaking influenced by Caligari. Its expressionistic imagery entered contemporary culture through the years and has been recycled and revised in works of others, including Dr. Seuss (Packer, 2012). Therefore, whether his expressionism was intentional or not, Burton’s influence from the works of Poe, Dr. Seuss, or Gothic art, traces back to the origins of the elements of expressionism, which all of them had experimented on.

In one of his most personal films, the expressionist and gothic elements of the Burtonesque style are evidenced once again. Made in 1990, Edward Scissorhands deals with a plethora of motifs, relating to German Expressionism (Weishaar, 2012). The film is about a young man, created by an inventor who dies before finishing his creation, leaving Edward incomplete; with scissors, instead of hands. This film is Burton’s effective reimagining of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (1818), where he added his own elements for the portrayal of the monster. Edward is innocent, and simply wishes to fit in and be loved for who he is. He does not hurt anyone (intentionally), but his Gothic appearance and sharp fingers cause him to be feared and misunderstood.

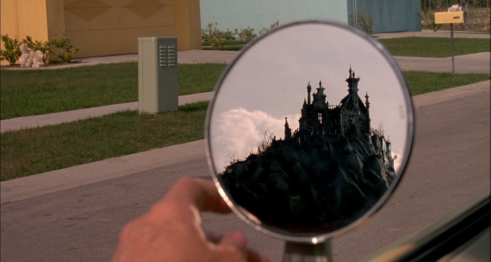

The location of the film, once again, portrays the duality in Burton’s universes, with a town painted in sweet pastel colours, and inhabitants who are seemingly normal and cheerful (Odell, 2001). (see figure 4). Contrary to this, Edward lives in a dark, Gothic castle on a hill – a significant expressionist theme evident in many Burton films– with broken windows and pillars, as well as a dark aura which makes it stand out in the background of the suburban neighbourhood. (see figure 5).

Possibly the most expressionistic element in this film is this aesthetic of contrast in location (town/castle), characters (nosy neighbors/innocent Edward), proportions (massive castle/tiny human subjects), as well as the extreme camera angles and dramatic use of light and shadow throughout the film.

Elements of Caligari are also directly reflected in the film, in the sense that Edward, similarly to Cesare, represents a ‘created’ human (Edward literally and Cesare metaphorically). The difference lies within Burton’s affection for outsiders, who he tends to portray as the ‘good guys’ of a story. In his castle, there is not a monster but a gentle creature who does not harm the townspeople. Instead, they are the ones who eventually become his antagonists, proving that they never truly accepted him (Salisbury et.al, 2006). (see figures 6,7,8,9).

Vincent and Edward Scissorhands have both been significant for Burton’s career and acknowledgment as a unique auteur. His sanitisation of expressionism, towards the development of a cultural interchange of the gothic nature of his influences and the mainstream, has been unprecedented in contemporary filmmaking.

Therefore, to enrich the existing literature, this dissertation will utilise a qualitative analysis to examine the ways in which the Burtonesque style has influenced other contemporary filmmakers in their work and how that may have helped re-define the ways films of the horror/fantasy genre are made.

CHAPTER 3: Methodology

3.1 Research design

This is a study which explores the historical development of German Expressionism, and its influence on Tim Burton’s work. The hypothesis of this study is that the Burtonesque filmmaking style has influenced other directors’ work, redefining the creation of contemporary horror/fantasy films. Therefore, a qualitative research is undertaken, utilising a semiotics analysis. The rationale for the selection of this methodology is to allow an inclusive, visual elaboration and identification of the Burtonesque influence on the sample films, by examining the films’ text and cinematography.

3.2 Semiotic Analysis

The comprehensive aim of semiotics is to study the production and understanding of signs as they manifest themselves in human and non-human spheres (Chandler, 2007). In semiotics analysis, the smallest units of meaning are called signs and people decode those signs to understand their surroundings.

Ferdinand de Saussure and Charles Sanders Peirce developed their science of semiology and science of semiotics, respectively, around the same time in the early twentieth century. According to Saussure the sign is formed from the relationship between the signifier and the signified (1959). (see figure 10).

Contrary to Saussure’s dyadic model, Peirce divided the sign into three parts: the representament (the form which the sign takes, like the signifier), the object (something which the sign refers to beyond itself, like the signified), and the interpretant (the sense made of the first sign). (Peirce and Hoopes, 1991)

The first semiotician to apply the semiotics theory directly to media was Roland Barthes in 1957 (Cobley 2001). According to him, the image has two layers: one for what and one for how it is represented. Thus, he suggests that, when applying the semiotics method to the analysis of media texts, the sign forms as a combination of the signifier and the signified, based on the signifier’s cultural upbringing (Barthes, 1972). According to some analysts, Peirce’s triadic categorisation, from which Barthes’s study draws, is fully employed in media studies which have their focus on semiotics analysis of domains such as advertising, films, video clips, or images (Wollen, 1969; Bruhn Jensen, 2002).

The relationships between the signifier and signified can be conceived either as semiotics of denotation or connotation (Metz, 2007), where denotation refers to the literal meaning encoded to the signifier and connotation refers to the socio-cultural and personal associations of the decoder with the sign. In terms of the specific approach, this research will focus on the identification and analysis of signs identified in the sample films.

3.3 Samples

For the sampling of this study, there needs to be a consideration of logic and legitimacy regarding the study’s objective (identifying and examining Burtonesque signs in later films of the same genre that were produced in Hollywood).

Therefore, in terms of legitimacy, the first stage of selection resulted in films that were produced within the Hollywood film industry. The films also needed to be produced after 1989, which is the release year of Burton’s first production Vincent, since the objective is to show the influences from his work. Additionally, in terms of logic, the films had to be within the fantasy and/or horror genre, similarly to Burton’s aesthetic.

In the second stage of selection, the samples needed to be narrowed down to two films, which would be the representatives for this study. Therefore, based on the selection processes, the final film samples are The Addams Family (Barry Sonnenfeld, 1991), and El Laberinto del Fauno (Pan’s Labyrinth) (Guillermo del Toro, 2006).

Even though there will be some differences in film context the categories in which the analysis will be focused on in each film will be: (1) Plot/Narrative; (2) Characters (psyche, behaviour, costumes, makeup); (3) Cinematography (lighting, shots); (4) Relations to Burtonesque (gothic element, ‘otherness’, rejection of authority, paranoia/madness, duality).

CHAPTER 4: Analysis and Discussion

4.1 About this chapter

This chapter will provide the analysis of the sample films from the four selected categories and their relation to the Burtonesque style.

4.2 Pan’s Labyrinth

4.2.1 Plot/Narrative

Directed by Guillermo Del Toro and released by Warner Bros in 2006, Pan’s Labyrinth is situated in 1944, during the Spanish Civil War. The film begins with a black screen accompanied by the faint sound of a person struggling to breath. As the blackness dissolves, a young girl (who is soon revealed to be Ofelia) appears lying on the ground with a river of blood disappearing from her nose in a reverse shot. This implies that the story the viewers are about to witness is a flashback or a memory. As the camera dives into Ofelia’s eyes, the voice of a narrator begins to unravel the tale of a young Princess who disappears from her Kingdom, but is destined to someday be reborn and return. After the narration, the scene cuts to a car bearing the Fascist symbol, in which young Ofelia and her sick, pregnant mother are travelling to the countryside, to stay with Ofelia’s step-father, Captain Vidal. Using a lot of symbolism, the film explores Ofelia’s story as she grows up between the hostile environment of war and the magical world of fairytales, in which she turns to escape from the harsh reality. What is clear from this opening sequence is the extraordinary fluidity between the two worlds; between fantasy and reality. (see figure 11).

As soon as the car arrives to the house they will be staying at, Ofelia meets Captain Vidal, who appears to be strict and cold, not hesitating to snatch the girl’s hand when she tries to greet him with the wrong one. Soon after that, she follows a stick insect, which she identifies as a fairy, into the forest where she discovers an ancient labyrinth. In that labyrinth, she encounters a mysterious Faun, a creature of the forest, who tells her that she is the lost princess Moanna of the Underworld Realm, and that she needs to complete three difficult tasks to prove herself and return to her kingdom. (see figure 12,13).

The first task requires her to crawl in the roots of an old tree and kill the evil frog who devours it from the inside, and collect a key from its belly. Things seem to be going well for Ofelia, as she is initially successful with the tasks, until the events in her life with her cruel step-father and sick mother turn for the worst. For the second task, she must visit a dining room with a table full of delicious food and fruit, and a scary ‘Pale Man’ sitting still at its head. She is instructed not to eat or drink anything from the table and simply collect a dagger from a locked box with her key. While she is in the room though, she cannot resist some grapes from the table, resulting in the Pale Man to wake up from his slumber and attempt to eat her. She manages to escape at the last minute.

After her mother dies while giving birth to her half-brother, Ofelia is left all alone under the ‘care’ of Captain Vidal, whose murderous behavior and cruelty scare her even more. Her final task, requires her to take her newborn half-brother and sacrifice him to the full moon, so that she can return to her kingdom; a requirement she ultimately chooses to refuse, resulting in her death. As she draws her last breath inside the labyrinth, her surroundings dissolve and she appears before her royal parents, who welcome her in their magical realm. At this point the audience is let to believe that everything magical in the film has been a product of Ofelia’s imagination, but as the movie ends the interplay of the real and the fantastic are left unclear, and up to the audience’s interpretation.

There are several gaps in the story’s narrative, mainly as far as the fantastical and real worlds are concerned. For example, in a scene, the Faun gives Ofelia a mandrake to place under her mother’s bed to keep her and the baby safe. In a moment of fury, Captain Vidal discovers the root and get furious at his wife for letting Ofelia believe in magic, causing the submissive Carmen (Ofelia’s mother) to throw the mandrake in the fireplace and immediately fall to the floor as if the death of the plant resulted in her getting more sick. Also, in another scene, Ofelia is in the bathroom reading a book, in which a bloody stain begins to form on the pages moments before her mother screams for her, while her white nightdress becomes red from almost having a miscarriage. Moments like these confuse the audience even more as to how vivid Ofelia’s imagination is and whether her magical encounters are real.

4.2.2 Characters

The character whose eyes are the portals through which the audience learns the story is 10-year-old Ofelia, whose vivid imagination seems to merge with the reality she lives in. She appears to be laconic and rarely expresses her true feelings or thoughts to the adults around her. Even though she loves her mother very much, she feels a distance between them after her mother remarried, since her focus ever since then is to please the Captain. As the story progresses the viewer realises that most of the time Ofelia is alone, with no one to talk to so she finds escape in her imagination. The fact that every magical encounter in the film is seen from her perspective, causes the audience to view everything on a denotative level which confuses them as to whether it is real or imagined. Ofelia appears to not be afraid to face the tasks given to her and she bravely faces the dangers of the giant toad or the Pale Man. When the time comes though, she chooses to save her innocent brother and give up her throne. On a connotative view, she can be described as the young, heroic outsider who struggles against living within an evil, adult world of war and murder, and escapes into a magical realm of eternal life, which gives the story a coming-of-age element. (see figure 14)

The Faun, appears to Ofelia as a type of mentor who is supposed to guide her through her journey. His looks, his voice and the way he moves suggest that he has been around for a very long time and that he is wise. His appearance is a juxtaposition of a dark, eerie and kind nature and even though hesitant at first, Ofelia chooses to trust him and follow his instructions, until the moment he asks her to sacrifice her brother. (see figure 15)

Contrary to Ofelia’s innocence and heroism, Captain Vidal appears as an impersonation of everything that is evil. He is shown beating a man to death in front of his father, right before he kills him as well, because they were -falsely- accused of being rebels. He appears as the ideal military man, with shiny boots, tidy clothes and slicked-back hair, to retain the respect and fear of the people he orders. His marriage to Carmen is mainly a way for him to have an heir, instructing his wife’s doctor to save the child if he must choose. Eventually, he kills the doctor himself, for not following one of his orders, resulting in his wife having to give birth in the hands of an inexperienced paramedic, who cannot save her life. On a denotative level, his actions suggest a cold-hearted military man, who will stop at nothing in his quest for power and immortality through his son. On a connotative level, the film portrays, through symbolisms, his existence as something much more than that. The monsters which Ofelia faces for her tasks, can be interpreted as Vidal’s (and extensively, the Fascist regime’s) monstrous qualities. As the giant frog devours the tree of life from its inside, Vidal devours his wife’s life with his decision to save the baby, and just like the Pale Man, he devours his people’s liberties, by providing only one food card for each family, while he dines luxuriously at the head of the table. (see figure 16)

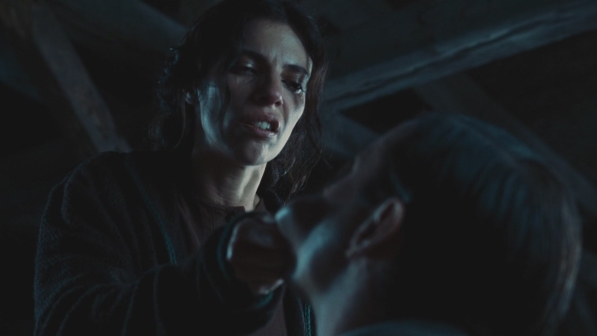

One of Vidal’s caretakers is Mercedes, a kind woman who appears to be the only person Ofelia trusts, besides her mother and her fantastical friends. Mercedes has a brother who fights with the guerillas in the mountain who she secretly helps by providing medicine, delivering letters and information that she overhears from the Captain. Consequently, she lives in a constant battle with herself, for having to obey the man she hates, as well as in constant fear for her brother’s and her own life if she gets exposed. When that eventually happens, she is held hostage by the Captain, who bloats about torturing her and how easy it will be since she is ‘just a woman’. To his ignorance, she has a knife hidden in her clothes, with which she stabs him, deforms his face and escapes. Mercedes represents the underestimated people, whose strength and resistance to the authoritative powers is more than the obnoxious Vidal, or the Fascist regime, can imagine. (see figure 17)

4.2.3 Cinematography

The significance of lighting and camera movement in the film is extreme, since it helps to create the feeling of darkness and isolation of the characters, as well as to portray the two worlds (real and fantastical) as they are viewed by Ofelia. To create bridges between the two worlds, the director uses horizontal and vertical wipes to establish the parallel narratives, but also to bring them together. Utilising the technique of the masked cut, he manages a fluidity in the film’s texture, while the camera goes behind a tree, or follows an insect from a shot of the real world to a shot of the fantastical one.

Apart from camera movements, the use of light is also very detailed and focused on portraying the two realities. In Ofelia’s fantasy world, the colours appear to be warmer, in shades of gold and crimson, while the real world is mainly painted in cold shades of black, blue and green. Most of the film is shot in low-key lighting, which enhances the contrast between light and dark, creating an eerie atmosphere of deep, dark shadows. The combination of colours and lights also serves to put emphasis on the last scene of the film, where Ofelia ‘returns’ to her realm, which is portrayed with warm and oversaturated golden hues, to enhance its magical elements. Additionally, there are scenes shot from weird angles, which make certain characters seem larger, and thus superior than the others, as well as many close-ups of the characters’ faces. A notable scene is when Mercedes attacks Captain Vidal and appears to finally be the larger person, who takes control of the situation. (see figures 18,19,20,21)

4.2.4 Relations to the Burtonesque style

After analysing the signs and symbols of the film, many similarities with the Burtonesque style can be evidenced. The film has similar aesthetically detailed fantastical locations and characters, as well as familiar tones of eeriness in terms of narrative and cinematography to Burton’s work. The narration in Pan’s Labyrinth resembles the narration in Vincent, while the portrayal of the events through the eyes of an innocent child, follows Burton’s portrayal of young or innocent adult characters who act in their own ways within society. Just like in Burton’s works, Guillermo Del Toro utilises the technique of the flashback for the narration of the story, which focuses on the juxtaposition between two sides of a dual world. The rejection of authority, another Burtonesque aesthetic, is used in the film, expressed through Ofelia’s rejection of everything her step-father would like to hear, as well as through Mercedes, who actively rejects and fights Vidal (the representation of the authoritative regime).

Ofelia is portrayed to have a different type of aura around her in relation to her surroundings, giving her an essence of an outsider, an element which Burton deeply likes to explore and portray in his films. The eerie elements of fantasy and horror work together to portray not only the character’s psyche and questionable mentality, but also the socio-political happenings of the corrupt society of the time. Influenced by Burton, Del Toro creates a dark fairy-tale which appeals to both kids and adults, in which his utilisation of low-key lighting and heavy contrasts of light and dark resemble Burton’s gothic aesthetic, resulting in an open to interpretation ending, accompanied with a timeless historical reference.

4.3 The Addams Family

4.3.1 Narrative/Plot

Different from the others, The Addams Family is the only film in this study which features comedy and dark humour, with casual references or implicit confessions to deviant sexual acts, torture and all varieties of murder as some of its characteristics. Directed by Barry Sonnenfeld and distributed by Paramount Pictures in 1991, the story follows the eccentric Addams’s as they welcome Fester Addams to their home; Gomez Addams’s (family’s patriarch) long-lost brother. What they do not know, is that Fester, who has teamed up with his mother and the Addams’s lawyer, is a fake who wants to get close to the family and steal their fortune. The family lives in a big mansion on a hilltop, (see figure 22) whose inside resembles a gothic castle just like the ones children read about in fairy-tales or comics. There is a big family graveyard in the back of the mansion, where the family’s ancestors are buried, with sculptures, depicting the ways they died, in front of each grave. The mansion is decorated with dead flowers and spider-webs, while the family’s everyday menu is inspired by ‘Gray’s Anatomy’. After a series of unfortunate events, resulting from Fester’s arrival at the house, including the family being evicted, the truth is revealed and everyone finds out that Fester is indeed Gomez’s brother. His ‘mother’ had simply found him with amnesia and decided to brainwash and use him to earn money.

In the Addams’s house the rules are suspended and adjusted based on the family’s wishes. If they desire to have a ball, the ballroom simply transforms to their command and music plays for them to dance to. On a first viewing they are simply a weird, gothic family in a huge mansion, but when looking deeper into their symbolism, their estate and their behaviours represents any individual’s hidden desires.

The film begins with a group of people, happily singing Christmas carols outside the Addams’s house, while the camera leads us with a one-shot to the roof of the house, where the family is ready to empty a giant pot of hot liquid on them. With the utilisation of humour, the film portrays the adventures of the Addams’s, as a family which functions in their own, eccentric and gothic ways within a society of mainstream normalcy.

Although the narrative of the film is quite straightforward and easy to follow, the characters often discuss about events of their past, which provide useful information about their psyche and personalities. For example, in a scene where Morticia and Gomez are sitting on a sofa in their cemetery, they discuss their first meeting that happened during a funeral, which Morticia remembers as her first. There are also several gaps in the narrative in terms of logic and physics. It is not clear whether the Addams’s are alive, dead, immortal or simply a family of eccentrics. They have a Frankenstein-inspired butler, a Thing for a pet/helper, and one of their hobbies is a game called ‘Wake the dead’, where they dig out their ancestors’ graves and shout for them to wake up and spend time with them. The children explore new ways of killing each other daily but they are always walking around without even a minor injury. Their traditions and what they consider to be normal and romantic appear – through surreal humour – to be completely different from the mainstream conventions of such elements. The existence of these characters therefore, can be translated as a manifestation of Gothic, horror cartoons, whose nature and abilities are not to be analysed further, and the focus of the viewer should be maintained on their adventures.

4.3.2 Characters

The Addams Family is consisted of Gomez and Morticia Addams, parents of Wednesday and Pugsley Addams; Grandmamma; Lurch – their butler/housekeeper/nanny -, and Thing, a disembodied hand that helps in the house. All family members have eccentric personalities and looks, and appear as completely different from their social circle, even though they do not seem to care at all.

Gomez Addams, is a joyful, enthusiastic man, who wears expensive suits and extravagant outfits, while always smoking a cigar. He likes to throw knives and juggle, as well as play with his trains – which are not as innocent as they sound. Apart from his childish and energetic aura, he is deeply in love with and devoted to his wife and his family is very dear to him. When he is led to believe that his brother is back, he gets over-excited and tries to spend as much time with him as possible, revealing secret passwords and locations in the house to him. (see figure 23)

The matriarch of the family, Morticia Addams (see figure 24) is portrayed as a strong woman, whose looks and interests resemble the traditional interpretation of a witch. She is tall, extremely pale, with a very slim waist and long black hair. She wears heavy contoured makeup and has long red nails. She usually wears long, black, gothic, mermaid dresses and heels. She seems to enjoy ballroom dancing, and cutting the buds out of roses and decorating the stems in vases. She dotes on her children and tries to teach them good manners (in the Addams Family logic)

The siblings Wednesday and Pugsley Addams (see figure 25) are seen to have adopted their parents’ ideals and style, since Wednesday is pale and dressed in long, black dresses, while wearing her hair in two long braids, and Pugsley usually wears striped t-shirts and shorts. One of their favourite hobbies is trying to kill each other using several methods, such as electrocution or knives, activities which their parents not only encourage but also enjoy.

The children’s uncle, Fester Addams is probably the most symbolic character in the film. (see figure 26). Portrayed brilliantly by Christopher Lloyd, Fester is a big, bald man with a pale face and dark eyes, visibly different from his ‘mother’s’ normal appearance, making it hard to believe they are indeed related. He is believed to have been lost in the Bermuda Triangle, an experience which caused him to suffer from amnesia. When Abigail Craven found him, and told him that she was his mother he became incredibly attached to her. The two share a complicated relationship, as Abigail appears to psychologically manipulate Fester for her own profit, using guilt as her main weapon. After Fester spends more time in the Addams’s mansion though, he begins to feel at home and enjoys his time with the family, eventually losing track of his mother’s plan to steal their fortune. By the end of the film, he realises that Abigail does not really care for him and chooses to help Gomez and Morticia take back their home. He opens a book from the Addams’s library, titled as ‘Hurricane Irene’ that literally causes a hurricane in the room and sends Abigail and Tully (the lawyer) in the family graveyard. The hurricane also causes a lightning to strike Fester, who finally gets his memories back. Extensively, Fester can be viewed as the representation of the naïve and helpless individual who is manipulated by a strong authority, without realising it, and his act of rebellion is an expression of rejection of authority.

4.3.3 Cinematography

The film’s eerie and gothic aesthetic is mainly attributed to its detailed sets, props, costumes and makeup, as well as the characters’ behaviours. The use of lighting and camera movements though, are also significant in the enhancement of those aesthetics. There are often close-up shots of the characters’ faces, appearing from unusual angles, to emphasise their exaggerated performances and their contoured facial features. Additionally, there are many instances in which tracking-shots follow Thing around the house transitioning through the different scenes, for the narrative to have a fluidity of movement, as well as showing the viewer details of the mansion. Props, such as a bear-skin rug that moves and opens its mouth, are observed before returning to the main character’s doings, to provide a fantastical feeling of moving throughout the space and viewing everything from a different perspective, that a person would not normally have.

In terms of lighting, the film is mostly shot in low-key and harsh lighting (see figures 27,28) to create the eerie, gothic elements of the genre, as well as enhance the character’s heavy makeup. The hard lights cast dark shadows which contrast the character’s pale faces making them appear scarily imposing and grand, resembling members of royalty when they stand next to the ‘normal’ characters, within the mainstream, suburbanised society they live in.

4.3.4 Relations to the Burtonesque style

Even though this film has some differences in terms of genre with most of Burton’s work, there are many instances where influence from the Burtonesque style can be identified. The most significant influence is the portrayal of the Gothic style and architecture, which Burton famously brought on contemporary cinema. Their gothic, exaggerated makeup, eccentric personalities and the sense of madness they seem to emit to their social circle, are direct similarities to Burton’s creepy ‘outsider’ characters. Everything about them, from their style, to their house and favourite activities is an expression of Gothic art and culture. They appear to be dark and scary at first, but as their story unravels they become loveable because of their strong family bond and insistence on being true to their nature, no matter how much the outside world changes. With this notion, a sense of duality can also be identified in The Addams Family, as their enormous, Gothic castle stands tall on the top of a hill, in the middle of a seemingly normal town. Their coexistence with every day people, who find them weird and scary, can be translated as the coexistence of two worlds, the ‘magical’, dark world of the Addams’s and the real world. The fact that only certain people, specifically those who embrace the Addams’s views on life, can enter that magical world is a direct link to Burton’s dual worlds, in which only the misunderstood, outcast characters can enter.

Another similarity, is the eagerness in which the laws of nature are defied in the film, which resembles many aspects of Burton’s work, including Vincent’s thoughts about experimenting on his dog, turning him into a zombie, as well as Edward Scissorhands’s existence as a creation, that can experience human feelings. Additionally, Burton’s favourite motif of the rejection of authority is once again evidenced through Fester’s character development.

In terms of cinematography, the similarities are mainly limited to the use of low-key lighting for the effects of the horror genre and the dark atmosphere, which could be influenced by Burton’s style, or simply be part of the director’s view on how horror films should be lighted.

CHAPTER 5: Limitations and Conclusions

5.1 Limitations

Although this study has reached its aims, there have been some unavoidable limitations which should be pointed out. Because of the time and word limit, the research was conducted only on the small sample of two films that meet the requirements for the study. Also, since semiotic analysis depends heavily on the relationship between signifier and signified, the analysis is conducted from the author’s perspective. Therefore, to extend the results for the Hollywood production style in general, a bigger sample should have been involved. And for a less personalised result, the utilisation of a mixed methodology (semiotics, shot- by- shot and genre analysis) would be more beneficial.

5.2 Conclusion

This examination has utilised a qualitative approach to discuss the influences of German Expressionism in the development of Tim Burton’s filmmaking style (‘Burtonesque’), as well as this style’s influence on other director’s works in the same genre, within the Hollywood film industry. The historical delineation of the German Expressionist movement serves to better situate the reader on its significance as the ancestor of the horror/fantasy genre. Its relation to Tim Burton’s work introduces the marriage of the movement’s original characteristics with the director’s unique imaginings in the contemporary film industry. A brief case study on two of Burton’s films helps to better introduce his style and influence from expressionism to readers not familiar with his work.

As it is suggested by the limitations of this study, the size of the sample analysed is not enough to generalise a refinement in the Hollywood production system. However, it does show that while working within the system, Burton’s stigma is evident on how contemporary horror/fantasy films that challenge the mainstream portrayals of the genre, are created. This study’s importance therefore, lies with its placement as a strong starting point in identifying similar changes within the Hollywood system. Further studies are suggested.

References

Barlow, J. (1982). German expressionist film. 1st ed. Boston: Twayne.

Barthes, R. (1972). Mythologies. 1st Ed. New York: Hill and Wang.

Benyahia, S., Gaffney, F. and White, J. (2009). A2 film studies: the essential introduction. 2nd ed. Routledge.

Boorman, H. (1986). Rethinking the Expressionist Era; Wilhelmine Cultural Debates and Prussian Elements in German Expressionism. Oxford Art Journal, 9(2), pp.3-15.

Bordwell, D. and Thompson, K. (2009). Film History: An Introduction. 1st Ed. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Braun, E. (1996). Expressionism as fascist aesthetic. Journal of Contemporary History, 31(2), pp.273-292.

Bruhn Jensen, K. (2002). A Handbook of Media and Communication Research Qualitative and quantitative methodologies. 1st ed. London and New York: Routledge.

Burton, T., Salisbury, M. and Depp, J. (2006). Burton on Burton. 1st ed. London: Faber and Faber.

Caughie, J. (2013). Theories of authorship. 1st ed. Routledge.

Chandler, D. (2007). Semiotics. 1st ed. Routledge.

Clarke, J. (2002). Neo-Idealism, Expressionism, and the Writing of Art History. Art Institute of Chicago Museum Studies, 28(1), p.24.

Coates, P. (1985). The story of the lost reflection. New Left Review, 143, pp.120-128.

Coates, P. (1991). The Gorgon’s gaze. 1st ed. Cambridge [U.K.]: Cambridge University Press.

Cobley, P. (2001). The Routledge companion to semiotics and linguistics. 1st ed. London: Routledge.

De Saussure, F. (1959). Course in general linguistics. Literary theory: An anthology, 1st ed. pp.59-71.

Dead Poets Society. (1989). [film] Directed by P. Weir.

Dejonge, A. (1978). The Weimer Chronicle. 1st ed. Plume.

Edward Scissorhands. (1990). [film] Directed by T. Burton.

Eisner, L. (1952). The Haunted Screen: Expressionism in the German Cinema and the Influence of Max Reinhardt. 1st ed. France: Le Terrain Vague.

Elsaesser, T. (2002). Weimar Cinema and After: Germany’s Historical Imaginary. 1st ed. Psychology Press.

Ferenczi, A. (2010). Masters of cinema. 1st ed. Paris: Cahiers du Cinema Sari.

Furness, R. (1973). Expressionism. 1st ed. London: Methuen.

Gay, P. (2001). Weimar culture. 2nd Ed. New York: W.W. Norton.

Gerstner, D. and Staiger, J. (2003). Authorship and film. 1st ed. Routledge.

Grant, C. (2008). Auteur Machines? Film and Television after DVD. 1st Ed.

Guynn, W. (2011). The Routledge companion to film history. 1st ed. London: Routledge Taylor & Francis Group.

He, J. (n.d.). Curator’s Essay, Inhabiting Tim Burton’s Universe. 1st Ed.

Hoberman, J. (1999). Heads or Tails. [Online] Village Voice. Available at: http://www.villagevoice.com/film/heads-or-tails-6420402 [Accessed 1 May 2017].

Kracauer, S. (1947). From Caligari to Hitler. 1st ed. Princeton: Princeton U.P.

Kreimeier, K. (1998). The Ufa-Story: A History of Germany’s Greatest Film Company 1918-1945, 23rd ed. Univ of California Press.

Kurtz, R., Kiening, C., Beil, U. and Benthien, B. (2016). Expressionism and film. 1st Ed.

Magliozzi, R. and He, J. (2009). Tim Burton. 1st Ed. New York: [Museum of Modern Art [MoMA].

McMahon, J. (2014). The philosophy of Tim Burton. 1st ed. Lexington, Ky.: Univ. Press of Kentucky.

Metropolis. (1927). [film] Directed by F. Lang.

Metz, C. and Taylor, M. (2007). Film language. 1st ed. Chicago, Ill: Univ. of Chicago Press.

Odell, C. and Le Blanc, M. (2001). Tim Burton. 1st ed. Harpenden: Pocket Essentials.

Packer, S. (2012). Cinema’s Sinister Psychiatrists: From Caligari to Hannibal. 1st ed. McFarland & Company Incorporated.

Pan’s Labyrinth. (2006). [film] Directed by G. Del Torro.

Peirce, C. and Hoopes, J. (1991). Peirce on signs. 1st ed. Chapel Hill, NC: Univ. of North Carolina Press.

Roberts, I. (2008). German expressionist cinema: the world of light and shadow. 1st ed. Columbia University Press.

Scheunemann, D. (2003). Expressionist film. 1st ed. Rochester, N.Y: Camden House.

Smith, J. and Matthews, J. (2007). Tim Burton. 1st ed. London: Virgin Books.

Sokel, W. (1959). The writer in extremis; expressionism in twentieth- century German literature. 1st ed. Stanford, Calif: Stanford University Press.

Spicer, A. (2002). Film noir. 1st ed. Harlow, England: Longman.

The Addams Family. (1991). [film] Directed by B. Sonnenfeld.

The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari. (1920). [film] Directed by R. Weine.

Truffaut, F. (1954). A certain tendency of the French cinema. Cahiers du Cinema.

Vincent. (1989). [film] Directed by T. Burton.

Weinstock, J. (2013). Mainstream Outsider: Burton Adapts Burton. The Works of Tim Burton, pp.1-29.

Weishaar, S. (2012). Masters of the grotesque. 1st ed. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland and Company.

Weisstein, U. (1981). German Literary Expressionism: An Anatomy. The German Quarterly, 54(3), p.262.

Wexman, V. (2002). A history of film. 6th ed. Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

Wollen, P. (1969). Signs and Meaning in the Cinema. 1st ed. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Woods, P. (2002). Tim Burton: A Child’s Garden of Nightmares. 1st ed. London: Plexus.

Appendix

Figures

Figure 1 Chiaroscuro lighting in Vincent (source: http://4.bp.blogspot.com/_yZ25ZxZBhDw/SPJF-sLpeMI/AAAAAAAACiA/ab6V3XEITkM/s320/vincent+6.jpg) accessed on 30/04/2017

Figure 2 Chiaroscuro lighting in Vincent (source: https://s-media-cache-ak0.pinimg.com/736x/e5/7f/3f/e57f3fa7a23e4220ad8c909c0c313348.jpg) accessed on 30/4/2017

Figure 3 Vincent Malloy imagines being Vincent Price (source: https://vincentmall0y.files.wordpress.com/2011/12/pg81.jpg) accessed on 30/04/2017

Figure 4 Neighbourhood in Edward Schissorhands (source: https://filmgrab.files.wordpress.com/2012/10/0614.jpg?w=1500&h=) accessed on 31/04/2017

Figure 5 View of Edward’s castle on the hill (source: https://filmgrab.files.wordpress.com/2012/10/1114.jpg?w=1500&h=) accessed on 31/04/2017

Figure 6 Castle and city set in The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (source: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/en/e/e2/The_Cabinet_of_Dr_Caligari_Holstenwall.png) accessed on 31/04/2017

Figure 7 Contrast of Edward’s castle with the town (source: https://filmgrab.files.wordpress.com/2012/10/1214.jpg?w=1500&h=) accessed on 31/04/2017

Figure 8 Cesare in Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (https://filmgrab.files.wordpress.com/2014/09/1620.jpg) accessed on 31/04/2017

Figure 9 Edward Scissorhands (https://filmgrab.files.wordpress.com/2012/10/2014.jpg?w=1500&h=) accessed on 31/04/2017

Figure 10 Saussurean model of signs (source: http://visual-memory.co.uk/daniel/Documents/S4B/Images/sausdiag.gif) accessed on 25/04/2017

Figure 11 Ofelia follows the ‘fairy’ to the labyrinth (source: https://filmgrab.files.wordpress.com/2015/05/0420.jpg?w=1500&h=) accessed on 02/05/2017

Figure 12 Ofelia meets the Faun (source: https://filmgrab.files.wordpress.com/2015/05/1720.jpg?w=1500&h=) accessed on 02/05/2017

Figure 13 ‘Ofelia’ (source: https://filmgrab.files.wordpress.com/2015/05/6018.jpg?w=1500&h=) accessed on 02/05/2017

Figure 14 The Faun (source: https://filmgrab.files.wordpress.com/2015/05/1620.jpg?w=1500&h=1) accessed on 02/05/2017

Figure 15 Captain Vidal (source: https://filmgrab.files.wordpress.com/2015/05/1020.jpg?w=1500&h=) accessed on 02/05/2017

Figure 16 Mercedes and her brother Pedro reade to face Captain Vidal (source: https://filmgrab.files.wordpress.com/2015/05/5618.jpg?w=1500&h=) accessed on 02/05/2017

Figure 18 Cold hues of blue (source: https://lh4.googleusercontent.com/-OPF8SX-FrPY/TYI0SSm4zuI/AAAAAAAABSg/5nV-pMLxZbI/s1600/Pan-s-Labyrinth-Screencaps-movies-1749289-1024-576.jpg) accessed on 02/05/2017

Figure 19 HIgh contrast (source: https://filmgrab.files.wordpress.com/2015/05/2320.jpg?w=1500&h=) accessed on 02/05/2017

Figure 20 Low-key lighting (source: https://filmgrab.files.wordpress.com/2015/05/3120.jpg?w=1500&h=) accessed on 02/05/2017

Figure 21 Mercedes attacking Captain Vidal – shot from low angle (source: http://3.bp.blogspot.com/-Whs0eGKE6i0/UVEAKpKm9SI/AAAAAAAAC8M/ih4AzC712AE/s1600/Mercedes+Fish+Hooking.jpg.jpg) accessed on 02/05/2017

Figure 22 The Addams Family gothic castle/mansion (source: https://freeformapps.blob.core.windows.net/freeform/13nightsofhalloween/2016/273/e0d61d3e-588e-469c-b98b-566b41f003c9.jpg) accessed on 02/05/2017

Figure 23 Gomez Addams playing golf (source: https://images.moviepilot.com/images/c_limit,q_auto:good,w_600/ursa0iiyvwf6ew5bezoq/it-s-an-addams-remembering-the-great-life-tragic-death-of-raul-julia.jpg) accessed on 02/05/2017

Figure 24 Morticia Addams (source: https://s-media-cache-ak0.pinimg.com/736x/c6/14/fe/c614fee350ac80cde6c5ee9e43893c6b.jpg) accessed on 02/05/2017

Figure 25 Wednesday and Pugsley Addams (source: https://s-media-cache-ak0.pinimg.com/originals/e6/84/cc/e684cc177570ea8e15d92cb7b19fa979.jpg) accessed on 02/05/2017

Figure 26 Fester Addams (source: https://s-media-cache-ak0.pinimg.com/736x/cb/fc/39/cbfc392a0cb0e43f0afa394dd3386c13.jpg) accessed on 02/05/2017

Figure 27 Low-key lighting (source: https://www.google.com/url?sa=i&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=images&cd=&cad=rja&uact=8&ved=0ahUKEwj9–uJ9eXTAhVBDxoKHTUfC44QjRwIBw&url=http%3A%2F%2Fthe-bats-pyjamas.blogspot.com%2F&psig=AFQjCNEuAMsOukZ2O-RBVbHOqF9qSM141A&ust=1494525926840319) accessed on 02/05/2017

Figure 28 Harsh lighting (source: https://nb5it.com/images/karl-david-djerf-04.jpg) accessed on 02/05/2017

Cite This Work

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing stye below:

Related Services

View allRelated Content

All TagsContent relating to: "Film Studies"

Film Studies is a field of study that consists of analysing and discussing film, as well as exploring the world of film production. Film Studies allows you to develop a greater understanding of film production and how film relates to culture and history.

Related Articles

DMCA / Removal Request

If you are the original writer of this dissertation and no longer wish to have your work published on the UKDiss.com website then please: