Economic Effects of Heavy Metal Mining Industry in Cornwall

Info: 15170 words (61 pages) Dissertation

Published: 13th Dec 2019

Tagged: Economics

Is the return of heavy metal mining in Cornwall a sustainable option for supporting renewed economic growth?

Cover image: (Heraldry of the World)

Abstract

Cornwall has a rich industrial history – with fishing, agriculture and mining acting as the mainstays of the Cornish economy. Such industries, particularly the mining industry, proved pivotal for economic and infrastructural development within the region, whilst acting as one of the region’s largest employers well into the 20th century. Whilst the mining industry has arguably been replaced by the tourism industry as an economic pillar, contemporary debate continues as to the return of the industry. The question explored by this dissertation will examine the sustainability of this debate, drawing attention to economic and social factors, as well as the potential environmental consequences of mining activities. Whilst it can be argued that mining activities will promote social sustainability – through promoting skill sets and employability to an economically deprived region, the global commodities industry, emerging tourism industry and localised prevailing environmental issues remain as barriers to mining in Cornwall. By analysing mining case studies from within the United Kingdom, and examining global issues of environmental degradation, this dissertation argues that mining can represent a sustainable option for promoting economic growth within Cornwall – providing that environmental, social, and economic issues are correctly managed.

Contents

Introduction

- The Economic history of Cornwall

-

- A brief history of Cornish industry

- Cornwall in the modern era

- The UK mining resurgence

- Case Studies: The resurgence of heavy metal mining in the UK

-

- Projects within Cornwall

-

- Seabed Exploration

- The South Crofty Project

-

- Hemerdon Mine, Devon

- Curraghinalt, County Tyrone

- The sustainability of renewed mining projects for Cornwall

-

- The social sustainability of renewed mining activities,

- The economic sustainability of renewed mining activities,

- The environmental sustainability of renewed mining activities,

Conclusion

Bibliography

Introduction

The county of Cornwall has a distinguished mining heritage. Since the cessation of heavy metal mining in 1998, local residents and mining firms have actively campaigned for the return of mining activities, for its clear social and economic benefits for the region. Indeed, as a result of the loss of the industry, unemployment rates have risen, whilst local support industries have lost a crucial skilled labour market.

The return of mining activities to the region faces numerous sustainability challenges. Economically, mining requires high commodity rates for ventures to become viable. Cornwall is advantageous in that it houses numerous commodities, many of which are in demand through the increase in smart technology, and the need for developing green energies. Global commodity process however, continue to hinder renewed mining operations in Devon, and remain as a barrier for the success of Cornish operations.

Whilst mining operations are socially accepted within Cornwall, environmental concerns remain paramount – and therefore mining companies must adequately plan management strategies. In order to explore environmental concerns, social stability and economic barriers, a number of mining case studies from across the UK have been examined. National case studies, as well as international case studies relating to environmental degradation will allow the social, economic and environmental sustainability of mining projects to be examined, and enable the drawing conclusions as to whether a renewed industry would allow economic growth within Cornwall.

Chapter 1: Cornwall’s Economic History

A brief history of Cornish Industry

Contemporary debate over the return of heavy metal mining in Cornwall must be understood in the context of its role in Cornish history, and its role in the formation of a strong Cornish culture and local identity. Writers such as French (1999) recognise that mining history within Cornwall has endured for over four thousand years with heavy metal mining ceasing in 1998, with the closure of Europe’s last working tin mine – South Crofty. Strong fishing and mining communities led to the creation of strong regional trade routes between Ireland and Wales, whilst resulting in wider European trade routes (Champion, 2001), notably due to the Pilchard fishing industry – which at its height exported over nine hundred million fish annually (Clegg, 2005). Mining, fishing, and agricultural industries became cemented to the core of the Cornish economy, whilst Cornwall’s political significance grew, with the county having 44 MPs by 1832 – due to the importance of the mining industry for the Crown (British Archaeology).

Engineers such as Richard Trevithick pioneered steam technology (Jenkin, 1934) – put into use in the Great County Adit (a mining drainage system), a project which employed more steam engines then were utilised by the entirety of continental Europe and America combined (Cornish Mining World Heritage), further highlighting the global economic importance of the Cornish mining industry.

Several factors led to failures in both industries. The fishing industry suffered a decline from overfishing, and a reliance on the pilchard. Mining industries failed for varying factors, particularly Cornish emigration – ten thousand miners emigrated in the first half of 1875 alone. This largely began during the American independence movement (Rowe, J. 2004), and arose as a consequence of industrialisation within Cornwall, causing unemployment.

Furthermore, global price fluctuations and ease of access increased global competition. Whilst ore reserves were far from exhausted, the abundance of minerals in colonial territories such as Malaya (Roddy, R. 1995) allowed heightened production, and a step above the limited scope of mining offered in Cornwall – many mines could only hope to produce under 2,000 tons of tin or copper in their lifetimes (Gamble, B. 2011a). Whilst tin ore was smelted within Cornwall, processed tin products and copper ores were transported to areas such as Swansea, Liverpool, Birmingham and Bristol for industrial applications (Gamble, B. 2011b). This fundamentally affected the industrialisation and long term economic welfare of Cornwall (Exeter University, 1996).

The history of mining within Cornwall remains of critical relevance to the region today – forming a strong social connection to the mining industry in Cornwall. Mining heritage has defined a rich cultural history for Cornwall, a factor which supports the region’s growing tourism industry through heritage projects and museums. However, most important for Cornwall is the loss of employment opportunities offered by the mining industry. The subsequent loss and decline of these industries has led to increased unemployment within the region, particularly in traditional mining areas such as Camborne and Redruth – which have seen little economic development, despite large scale EU funding. Local communities are therefore largely supportive of the return of mining activities.

Cornwall in the modern era

To understand the potential impacts of renewed heavy metal mining within Cornwall, it is clear that there numerous considerations with regards to such a project. For example, environmental concerns are now paramount – largely as such activities take place in areas of outstanding natural beauty. Cornwall’s mining history has gained World Heritage Site status – awarded to Cornwall in 2006 (Wheeler, 2014, 22-32), and renewed mining operations pose a direct threat to such status (Kings, 2014). The awarding of this status has aided a growing tourist industry, which has become of critical importance to the Cornish economy – Cllr Andrew Wallis notes the contribution of tourism to the Cornish economy: £1.8bn during 2011, and the sustainment 25% of the county’s employment (Wallis, A. 2011). This may act as a barrier for the development of sustainable mining projects across the region.

Recent economic data published by Eurostat highlights that Cornwall is now the second poorest region within the UK (Inequality Briefing) – being heavily reliant on EU funding, the continuality of which has been jeopardised by the decision taken by the United Kingdom to leave the European Union. Renewed operations are supported by local MPs, due to Cornwall’s need for a diversified job market, and infrastructural development. Cornwall Council further supports the promotion of renewed industrialisation and mineral safeguarding, through planning permission and the granting of mining licenses (Cornwall Council, 2012).

The UK mining resurgence

Whilst the economic prospects of Cornwall are paramount to this study, examining case studies in both the UK and overseas will enable the drawing of comparisons between Cornwall and successful mining ventures. Examples of renewed mining interest include investment in both Northern Ireland and Devon for the production of heavy metals. Cornwall however continues to face a number of economic, social and political challenges – and proposed renewed mining activities directly threaten a developing tourism industry. It is therefore clear that the issue must be sustainably considered to secure a viable future for the industry in the region.

Chapter 2: Case Studies – The resurgence of heavy metal mining within the United Kingdom

Cornwall has historically been the mainstay of British metal mining – and the proposed return of heavy metal mining, which has been actively discussed since the late 1990s remains the main focus of this report. However, a number of other areas across the country have developed proposed mining industries for development within the 21st Century. Mining projects have been successfully implemented in the county of Devon, whilst the mining of gold has been proposed in County Tyrone, of Northern Ireland. This chapter will examine proposed projects in Cornwall, Devon and Tyrone to enable of the drawing of similarities and appropriate conclusions regarding the sustainability of mining ventures.

Case Study 1 – Projects within Cornwall

Global commodity prices have historically dictated the viability of mining projects, particularly in Cornwall. The International Tin Council (ITC) artificially maintained the market price of tin from both Cornwall and Malaysia until 1985, when owing to the failures of the ITC, the price of tin collapsed (Roddy, R. 1995). The build-up of strategic stockpiles of tin by the United States kept commodity prices low, as the global commodities market became flooded with the sale of surplus minerals (Baldwin, W.L. 1983). Cotemporally, large scale deposits of tin were located in Brazil in 1985 (Paxton, J. 1987), increasing the global availability of commodities and thus aiding the depreciation in the value of tin.

Notable individuals such as Professor Frances Wall, head of Camborne School of Mines (CSM) note that economic factors remain as one of the main barriers for Cornish mining, stating that, ‘The tin mines only closed down because the price of tin went down, not because there was no tin left in the ground’ (Morris, J. 2013). Whilst highlighting that Cornwall remains mineral rich, Frances Wall notes that economic uncertainty within a context of unstable mineral prices within a global commodities industry remains as one of the main barriers for investment.

In the modern era, China has emerged as the global hegemon behind the commodities market – and surging house prices and easily accessible credit within China has aided increases in commodity prices (Sanderson, H. 2016). Materials such as tin, copper and lithium are further in demand due to the growing technologies industry – minerals which are still held in reserve within Cornwall. Therefore, this chapter will first examine the two most detailed mining proposals within Cornwall: Marine Mineral recovery and the South Crofty project.

Project One – Seabed Exploration

In recent years, proposals by locally based firms have emerged to recover discarded minerals from the seabed of Cornwall’s northern coastline (BBC, 2016a) – an area historically polluted by heavy metal rich mine effluent. Whilst similar projects have occurred on land, notably in the tailings of mines such as Wheal Jane, this project marks a distinct diversification from traditional mining and recovery practises. Plans for the recovery of tin and other heavy metals from the seabed have been put in place by Marine Minerals LTD (MML), based in Falmouth, Cornwall (Matthews, C. 2014). Such proposals would create at least 100 direct jobs (Morris. J, 2013), and secure investment worth £15 million to the Cornish economy (BBC News, 17/02/2013).

MML aims to extract approximately 2 million tonnes of sand from the seabed per year for ten years, seeing the extraction of 1,000 tonnes of tin per annum (Morris. J, 2013a) – whilst returning 95 percent of extracted sand to the seabed (Gray. L, 2012). Whilst it is clear that such proposals may have economic benefits and lead to the diversification of employment opportunities in an increasingly competitive job market, locally based environmental groups are against such proposals. Andy Cummings, director of Surfers Against Sewage (SAS) opposes such plans, as ‘Disturbing and removing significant amounts of sediment has the potential to devastate the fragile and complex environments that support surfing, tourism and fishing’ (Morris, S. 2013b).

The surfing industry, coupled with the growing tourism industry has become of major economic importance for Cornwall in the 21st century. Socially, at least 1,607 Cornish jobs are reliant on surfing, whilst the industry itself contributes at least £154m annually to the local economy (Mills, B. 2013). Plans to recover minerals from the seabed could therefore threaten water quality, and remove sediments crucial for the formation of waves – factors which the surfing industry is reliant on. Whilst MMLs plans show investment from local companies, creating a small number of diversified jobs, concerns from SAS show that this industry may have far reaching consequences for Cornish economic development.

Project Two – The South Crofty Project

The South Crofty mine located near the economically deprived areas of Camborne and Redruth is arguably one of the region’s most long lived (Buckley, J.A, 1-10), and has sustained Cornish employment, skill sets and support industries throughout its lifetime.

Strongbow Resources, registered in Vancouver, Canada (Bloomberg, online), acquired 100 percent interest in the South Crofty mine and 26 former mines within the region – totalling 150km of mineral rights (Wilson, J. 18/03/2016). This formed part of a deal worth £1.4m (BBC News, 18/03/2016b), with a further investment of at least £77m in renewing mining infrastructure (Barton, L. 2016b). Whilst not operating working mine sites, Strongbow Resources currently operates five mine exploration sites in Canada, the US and UK.

Stringent testing shows that the mine holds a guaranteed resource limit of 2.5 million tonnes of tin, with potential for up to 24 million tonnes (Strongbow Minerals, 2017), aiding the economic sustainability of the proposals. Strongbow is not the first company to invest into the project – previous investment from Celeste failed, due to the inability to secure funding on the part of the mines owners – Western Mines United (BBC News, 2013). Whilst South Crofty has struggled to gain investment, plans have significantly advanced under Strongbow Resources.

Support from local authorities & industry

As with Devon County Council, Cornwall Council has been imperative in supporting renewed industrialisation plans within Cornwall, whilst recognising environmental and social sustainability. Mining is recognised as part of the wider economic plan for the Cornish economy for the period of 2016-2020 (Cornwall Council: Business Plan, 2016).

This has been seen through the granting of planning permission for surface mining infrastructure, and the extension of underground workings (BBC News, 2011a). Whilst permission was granted in 2011 for the Celeste Mining corporation (Celeste, 2013) – former Canadian investors into the project, such permission remains in place. Critically, Cornwall Council granted a mining permit to the workings during 2013 – valid for 53 years, securing external investment to the mine site.

Whilst local companies such as MML have developed mining plans independently, Strongbow began working with local mining businesses in 2017. This includes a business dealing for a 25 percent stake with the start-up company Cornish Lithium (Smith, G. 2017). Cornish Lithium hopes to drill for lithium, a mineral utilised in battery technology –in demand due to the growth in demand for electric cars. Global demand has therefore increased exponentially; in 2016, demand for the mineral was greater than supply (Yeomans, J. 2017). CRU data highlights that lithium of sufficient quality to be used in batteries has risen from approximately £5,700 a tonne in 2015 to £15,950 a tonne (Morris. S, 2017), with the lithium industry expected to be worth £56bn by 2020 (Barton, L, 2017). Such projects aim to reduce the carbon footprint of the industry – Cornish Lithium has secured geothermal energy rights as a direct result of mining processes.

Renewed industrialisation is supported by local Ministers of Parliament, such as George Eustice, MP for Camborne, Redruth and Hayle – traditional industrialised areas. With regards to the Cornish Lithium project, George Eustice notes the economic importance such an industry for the UK, stating, ‘If the team at Cornish Lithium is successful in developing this opportunity, the UK may not have to rely on imports of this vital mineral in future’ (Yeomans, J, 2017).

Social & Environmental impacts

Whilst mining proposals by MML directly affect the regions tourist industry, both Camborne and Redruth are not recognised as tourist areas, having seen heavy industrialisation. Mining projects in this area would therefore greatly benefit local communities – offering a wider scope of job opportunities to an economically deprived area. Whilst the mine sites have access to both road and rail links, they are set in increasingly urbanised areas – Camborne and Redruth area houses 55,400 individuals (Cornwall Council, 2011). As such, these individuals may experience both visual and noise pollution. The issue of low frequency noise is recognised by the World Health Organisation as a global concern, and has been effecting rural residents near the Drakelands tin-tungsten project – located near Plymouth, Devon. Whilst mining may be socially beneficial in terms of employment opportunities, it is clear industrialisation may cause social disruption.

Cornish mines have historically faced the encroachment of water – due to many mines being below sea level. Waste mine water will be disposed of through drainage adits into the Red River, having been treated by a two part water-treatment facility – a permanent facility which will treat 10,000m³ per day, whilst a temporary plant will treat up to 15,000m³ per day (Strongbow Minerals, 2017). Trials of water treatment practices have commenced, and are expected to be completed by February 2017 (Strongbow Minerals, 2017) to ensure that discharge meet Environment Agency (EA) standards.

Cornwall has suffered environmental damage to water courses due to historic environmental damage. In 1992, 50 million cubic meters of acidic metal laden water was released from the abandoned Wheal Jane mine (Younger. P.L, 2002). Surrounding water courses, such as the Carnon River and Falmouth Bay suffered both physical and visual pollution (Bowden, G.G et al, 1998), due to inadequate environmental management schemes following the closure of the mine set in 1991. The event severely impacted local aquatic biodiversity, public health, and impacted the developing tourist industry of the region. Economically, environmental management programmes since the disaster have cost over £20m (Younger, P.L, 2002), highlighting the long term environmental impacts of the mining industry. However, Wolf Minerals operating in Devon shown that active mining operations can adequately deal with environmental issues – particularly with regards to water usage. The Environment Agency stated that it was ‘satisfied that the treatment, retention, collection and re-use of water arrangements within the activities represent a BAT (best available technique) for water utilisation within the installation’ (Environment Agency, 15/07/2014).

Conclusions

A number of projects are taking place within Cornwall. Whilst some projects follow traditional mining paths, Cornish companies are committed to utilising new technologies – including the mining of lithium and recovery of minerals from Cornwall’s Northern seabed. Cornwall’s community and Council support the return of mining for the region – allowing for the creation and sustainment of 300 jobs, and large numbers of support jobs in the county and wider area. Traditional mining is planned to take place in urban areas – a historical legacy of mining, and as such, issues surround both visual and noise pollution, threatening social sustainability. Further threatening sustainability in the region are plans to extract waste minerals from the seabed, threatening developing industries and the environment.

Case Study 2 – Hemerdon Mine, Devon.

The Hemerdon mining project situated near Plymouth, Devon, highlights the return of a metal mining industry in the UK. Wolf Minerals, registered in Perth, Australia, gained full rights to the project in 2007 (Wolf Minerals, 2013). Such a project overcomes sustainable issues, whilst recognising the need to be an active, global producer of minerals – and the needs of local communities. To this end, Wolf Minerals have been increasingly supportive in engaging with communities on both social and environmental issues, whilst building on such concerns to create an increasingly sustainable project. This section of the report will examine the steps taken by Wolf Minerals in detail, in order to better understand sustainable issues within successful projects.

Wolf Minerals has invested £123 million in the building and planning of mining operations (Wilson, J.2015). As with proposals for South Crofty, the mine centres around the production of tin and predominantly tungsten, with the aim of producing up to 5,000 tonnes of tungsten concentrate per year (Clarke, R. 2015). The Hemerdon mine houses a known resource limit of 26.7 million tonnes, the third largest known deposit in the world (Wolf Minerals, 2014). Such a scale of mining contributes 3.5 percent of the global supply of tungsten (Wilson, J. 2015), whilst providing 20 percent of the Western supply of the metal (Vergnault, O. 2015). China however, remains the global leader in the production of tungsten, accounting for approximately 80 percent of global supply – moving from a net exporter to a net importer of the mineral (Ormonde Mining, 2017), largely to protect its own reserves. Global demand for tungsten is increasing for its usages in the technological and agricultural industries, as well as industrial manufacturing. As such, it has been designated as one of fourteen critical minerals by the European Union (European Commission, 2014).

As with both Cornwall and County Tyrone, Devon has seen rapid de-industrialisation, particularly due to the loss of traditional industries. The Hemerdon project has therefore seen increased interest from local job markets. Wilson (2015) notes that over 900 individuals applied for 40 operator vacancies during 2015, highlighting increasingly competitive job markets. The mine employs 200 individuals, with an average annual wage of £36,000 – compared to the average wage in Plymouth of £25,000 (Telford, W. 2016). Whilst relying on a skilled workforce, notably environmental protection officers, local support industries have been utilised – such as Holman-Wilfley, based in Redruth, Cornwall. The use of local support industries further secures wider regional employment, sustaining crucial skill sets and local opportunities.

Devon County Council, similarly to Cornwall Council, has been imperative in supporting the project. In the final quarter of 2016, county planners voted to extend the operating mining licence from 2021 to 2036, whilst allowing the on-site processing plant to operate seven days a week (Ford, A. 2017). Mining plans support Devon County Councils wider economic vision – the sustainment of skilled employment, increasing of wage brackets and the creation of a productive economy – through supporting investment into the region (Strategy for Growth, 2013).

As with proposed mining projects in Northern Ireland, the Hemerdon mine is situated on the Dartmoor national park, a designated area of outstanding natural beauty – raising environmental concerns. One notable feature of the project is the use of open-cast mining in order to access minerals, a process casing a larger scale of environmental degradation. This differs from Cornish and Irish proposals, which would utilise underground mining operations – whilst returning tailings underground. Planning documents show that at least 100 million tonnes of waste rock will be generated (Devon County Minerals, 2004), during the projected 20 year life of the mine. The waste rock generated by mining activities will be retained on site, landscaped and forested. These areas will encompass underground membrane lining, to prevent toxins such as arsenic leaching into the water table (Plymouth University, 2016).

However, the project has had negative impacts, including both visual and noise pollution. The Drakelands Mine community action group ‘Drakelands Noise’ notes the increasing presence of low frequency noise (LFN) emanating from mine processing facilities (Drakelands Noise, 2016). Such issues have increased, due to planning permission granted during 2016 for processing plants to run 24 hours a day. For the WHO, ‘The evidence on low frequency noise is sufficiently strong to warrant immediate concern’ (World Health Organisation 1999). LFN can cause both sleep disturbances and general anxiety – leading to physical stress symptoms such as headaches and raised blood pressure (Drakelands Noise, 2016). It is possible that such issues are in breach of both Devon County Councils planning constraints and the environmental permit from the Environment Agency.

Russel Clarke MD notes the wider environmental obligations of the company, stating in 2014 that, ‘We’ve spent over £300,000 on environment monitoring studies. We’ve created bat habitats, and built £12,000 worth of eel passes to let them get under the haul road. We’ve also planted 40,000 trees’. (Western Morning News, 2014). Documentation obtained from Wolf Minerals confirms the planting of at least 40,000 trees, with up to 1 million being planted over the course of the mines lifetime (Wolf Minerals, 2014). Further planning is in place for the site post closure, allowing public access for walking, marine and other leisure activities (Wolf Minerals, 2015), whilst landscaping works will take place to mitigate visual pollution from mine tailings.

Yet, the economic sustainability of the project remains questionable. Whilst the project has secured customers in Europe, Asia and the United States, Wolf Minerals made a loss of AUS$24million in the latter half of 2015 (Telford, W. 2016) – largely due to falling commodity prices and low production rates. Such losses have resulted in lower share price and increased loans of up to £30m (Quoted Data, 2016). These factors directly threaten the economic and therefore social sustainability of the project, as commodity prices dictate the success of mining opportunities.

Conclusions

The Hemerdon mining project remains an example of renewed mining ventures within the UK. The project has helped to secure social sustainability – both within Devon and the wider South Western region through the use of support industries. Both visual and noise pollution concerns remain paramount, particularly for local residents. Whilst such concerns are being met appropriately, such concerns may act as a barrier to the return of mining within Cornwall – due to a largely urban setting. Wider environmental mitigation factors are planned for, with the planting of trees and planning for the site post closure. Yet, whilst the project is a major producer of tungsten and tin, with secured markets, economic sustainability continues to dictate the success of projects.

Case Study 3: Curraghinalt, County Tyrone, Northern Ireland.

To better understand the potential success of mining projects in Cornwall, it is crucial to examine wider UK case studies. Northern Ireland has a very similar, post industrialised economy to Cornwall. Eurostat data published in 2014 showed that Northern Ireland (NI) was the eighth poorest region in Europe, whilst Cornwall remained the second poorest region (Inequality Briefing, 2014). As with Cornwall, County Tyrone has seen renewed mining interest – particularly in the Omagh area, due to high concentrations of gold deposits. Whilst mineral exploration began in the mid 1980s, Tyrone does not have a unique mining heritage, and as such, plans have seen levels of opposition from local residents. Such plans have advanced under Canadian registered Dalradian Resources (Reuters) – investment and mineral exploration in NI is Dalradians only active project, differing form Canadian based companies operating in Cornwall, which currently operate five active mineral projects.

Social Sustainability

The commencing of such a project raises issues relating to both social and economic security. As with Cornwall, job creation is crucial to the local economy of Tyrone – Dalradian plans to create up to 429 jobs when the project is in full production (Dalradian, Economy and Jobs, Online). As a whole, this offers wider initial job creation than renewed mining in Cornwall, which currently aims to produce a combined total of 375 jobs. Trained, underground mine workers are expected to earn approximately £40,000 per year – higher than the average wage earnt at the Drakelands project. As such, an estimated £21 million will be generated in wages, along with annual payments totalling approximately £18 million through income tax, corporate tax, and national insurance contributions for the UK government (Dalradian, 2016).

Dalradian has further invested in community investment. This includes: £3.5 million in the immediate local area, £16 million in County Tyrone and £27 million across NI (Dalradian, Economy and Jobs, Online) – as well as a further £220,000 in community based projects, such as community, healthcare, and the environmental projects. The creation of a skilled workforce in the local area enables the diversification of employability opportunities, and enables the development of a unique skill set in what is arguably an expanding industry.

Whilst renewed industrialisation creates increased social security, the concerns of local residents remain paramount to the sustainability of such a project. NIs infrastructure minister, Chris Hazzard confirmed that planning applications would require a public enquiry (Preston, A. 2017), due to the prevailing concerns of local residents of potential environmental degradation. As with proposed mining projects in Devon and Cornwall, the proposed mine site is situated in a designated area of outstanding natural beauty, which unlike Cornwall, has a limited mining history – and therefore mining operations have struggled to gain support from local residents in the immediate area (Dalradian, 2016).

Economic Sustainability

It is clear that Dalradian is committed to the Curraghinalt project. Upon contacting Dalradian for an interview, Peter McKenna, Community Relations Manager for Dalradian stated that the company aims to complete both its feasibility study and EIA (environmental impact assessment) within early 2017. Indeed, since 2009 the company has invested £40m in infrastructural improvements and feasibility schemes (Wilson, J. 2015). Feasibility studies carried out during the 2015-2016 period show that the mine, situated on the Curraghinalt gold deposit, demonstrates high levels of economic profitability. The mine has a potential yield of 3 million ounces (Wilson, J. 2016), and high reserve grades of ore put such a deposit in the top 10 percent of gold mines worldwide (Dalradian, 12/12/2016, 1-3), allowing for economic opportunities to enhance project longevity. Indeed, mining operations are predicted to yield up to 130,000 ounces of gold per year, increasing to up to 150,000 ounces – giving the project a minimum service life of up to 10 years (Dalradian, 2016).

Gold prices are relatively stable when compared to resources such as tin and tungsten – currently gold is worth approximately $1,250 per ounce (JMbullion, 2017). Yet it must be noted that countries such as South Africa remain as the fifth largest producer in the world, producing up to 170 tonnes during 2011 (US Geological Survey, 2013). Mining infrastructure is therefore embedded into the local economy and developed – South Africa houses the deepest mines in the world (Brindaveni, N. 2006). As such, high levels of initial investment are needed within County Tyrone to create modern mining infrastructure.

Environmental Sustainability

The project has however faced numerous environmental questions. Operations as with Cornwall will occur underground, lowering visual pollution – however adequate processing plants and tailings storage areas will be required (Dalradian, infographic, 2016) Mining processes require the use of cyanide, utilised in the separation of ore. Dalradian note that the “use of cyanide which is the industry standard method for gold extraction worldwide, including in EU countries such as Finland” (Young, C. 06/02/2016). Whilst cyanide has further industrial uses, it can cause large scale environmental damage upon entering waterways. Such events have occurred historically – the 2000 Baia Mare cyanide spill in Romania, caused by the Australian-Romanian mining company Aurul saw widespread pollution, after the spillage of 100,000 cubic meters of contaminated water (Batha, E. 2000). As a result, the drinking water of 2.5 million Hungarians was polluted, whilst up to 80 percent of aquatic life on stretches of the Tisza river were killed (Batha, E. 2000).

This has been a global issue with regards to mining project, indeed, Cornwall suffered from the effects of cadmium leaching into the environment as part of the Wheal Jane disaster. Dalraidian has therefore instigated environmental protection schemes worth £1m to protect local rivers, and recycling and testing utilised water supplies (Dalradian, infographic, 2016). Dalradian has therefore signed the International Cyanide Management Code (ICMC), which ensures inspections beyond what is required by law (Dalradian, infographic, 2016). The ICMC is a global voluntary organisation, committed to setting global industrial standards for cyanide management – such as protecting workers, the environment and ensuring the substance is correctly transported and utilised (ICMC, 2015). Engagement with both the DoE and NIEA has occurred, to install 2000 meters of fencing in order to prevent the silting of rivers and animal trespassing, and to ensure environmental standards meet legal requirements

As such, the concentration of cyanide levels will be below EU limits at the end of the mining process, whilst materials that have come into contact with cyanide will be detoxified and returned underground (Dalradian, online). However, it is clear that issues surrounding the use of cyanide remain as a barrier for community relations, and critically effect the environmental sustainability of the project.

Conclusions

The Curraghinalt gold project represents increasingly sustainable mining venture within the United Kingdom. Though differing in scope from Cornish operations – through the mining of Gold, Tyrone faces both environmental and social challenges. Dalradian has been increasingly supportive of local communities and has noted its obligations to the environment, beginning the process of environmental management before the commencement of mining operations. Whilst environmental damage through the use of cyanide remains a viable risk, socially, the mine will offer high paid, highly skilled work to an economically deprived area of Northern Ireland. Stable gold prices and a guaranteed service life of 10 years increases the economic sustainability of the project, however established global gold producers and high start up costs may impact on the economic viability of the project.

Chapter 3: The Three Pillars of Sustainability

This chapter will examine the sustainability of mining proposals within Cornwall, utilising case studies identified in the previous chapter, to allow for the drawing of academic conclusions. The Brundtland Report, published by the United Nations World Commission on Environment and Development defines sustainability as, ‘the ability to make development sustainable to ensure that it meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs’ (WCED, 1987). Sustainability is split into three areas: social, environmental and economic factors (Boons, F. et al 2011), which will be examined in this chapter. A renewed mining industry will undoubtedly have social and economic benefits for the region, such as increasing employability opportunities and attracting investment to the region. Yet, the mining industry may introduce a number of consequences, including negative impacts to both the tourist and surfing industries, and environmental threats to water courses and aquatic biodiversity.

The social sustainability of renewed mining activities

Whilst proposals to begin mining heavy metals in Cornwall have both environmental and political implications, it is important to note the social sustainability of such projects. Due to the loss of traditional industries such as mining and to a lesser extent fishing, Cornwall has seen economic deprivation, a loss of crucial skill sets and large scale unemployment. Whilst unemployment rates have halved in the region – partly due to the emerging tourism industry, it is clear that job creation remains low, and positions highly competitive. It is for this reason that many individuals within Cornwall support the return of mining activities, due to the need for a diversified job market – particularly in economically deprived areas.

With the UKs decision to leave the European Union, the future of funding for social projects across the region is now under pressure – particularly investment from external companies, looking to the region for natural resources. Furthermore, whilst such investment is welcome for the stagnating job market, it clearly threatens Cornwall’s unique World Heritage Site status and may negatively impact the county’s tourism industry – its largest employer. This aspect of the report will examine the social sustainability of renewed mining operations in Cornwall.

Job Creation and Sustainability

The creation of jobs is of critical importance for both the economic and social development of Cornwall. Strongbow plans to create at least 275 jobs for the Cornish economy (Barton, L, 2016), whilst MML aims to create 100 jobs (Morris, J. 2013). Whilst limited in job creation, such projects are needed as Cornwall has a small job market. Cornwall Council data shows that in November 2016, 2,039 jobs were available in Cornwall and the Isles of Scilly (Willis. P, Cornwall Council, 2016). Registered unemployment in Cornwall has fallen in recent years, to approximately 4,330 in April 2016, whilst the county’s unemployment rate stands at 3.9 percent – lower than the national average of 5.1 percent (Cornishman, 18/05/2016). However, a large number of individuals – 52,266 (Willis, P. 2016) – are self-employed, and therefore potentially living beneath national wage standards.

Historically, mining acted as one of the region’s main employers. At its height, the mining industry employed over 25 percent of Cornish males (Robinson, M. 2017), whilst sustaining the employment of at least 55,000 females as bal maidens (female mine labourers) between 1720 and 1921 (Mayers, L. 2008). Whilst such figures declined due to increased industrialisation, price fluctuations and workers rights, the role of support industries grew. A dependence on support industries led to the employment of over 3,000 workers Carter, 2001).

For mining projects to be a social success in Cornwall, job creation must be examined. It is envisaged that mining operations at South Crofty will create 110 jobs during the construction phase – an increase of 95 compared to the current levels of employment (Pirate FM, 2017). Whilst such figures may appear low for a population as large as Cornwall’s, it is crucial to note that renewed mining operations will directly benefit support industries, both locally and nationally. Furthermore, the longevity of proposed mining operations secures such jobs for at least ten years, whilst providing skill sets transferable to a range of career paths. It must be recognised that the mining industry itself houses a diverse range of employability roles, from relatively skilled underground work to management roles requiring further education at degree level. Skills required by the modern mining industry include technological knowledge, the maintenance of mining equipment, and management, training and health and safety roles (Iminco, 2014). Active mining projects in Devon, notably the Hemerdon Mine, and proposed mining activities in County Tyrone offer higher average rates of pay when compared to other local industries. This highlights the strong skill sets required by the industry, and offers local populations increased rates of pay in regions where the average cost of living is increasing. Whilst skill sets are present in Cornwall due to the county’s historical association with the mining industry, Strongbow will provide skills development packages where necessary in order to maximise the employment of local residents at the project (Strongbow Exploration News, 2017). This highlights a recognition of the need to create guaranteed employment, whilst developing the skill sets of local communities.

In the context of the Brundtland Report, the ten years of guaranteed mining operations proposed by Strongbow Exploration represents minimal sustainability in terms of employment. Whilst offering relatively short term employment opportunities, it must be noted that the mining industry relies on finite resources -in this case heavy metals such as tin. When tin stocks are depleted, the mining industry will be unable to sustain employment and generate income. Yet, the skill sets developed by the mining industry, particularly mechanical and management roles are crucial, as such skills can be transferred to established and sustainable localised and national industries.

As well as offering direct jobs, Joff Bullen, a notable mining expert explained that, ‘Jobs aren’t just created for the people working in the industry. It’s predicted that for every job created in mining, in turn four more are created in other business areas that support the miners’ (Matthews, C. 2014). This is particularly true when examining industries such as Holman, which still acts as a regional exporter for mining equipment. The creation of jobs in associated industries would allow for the broadening of employment opportunities, and diversify employability skills through apprenticeship packages and educational placements – a factor recognised as crucial for local development by both Strongbow and Dalradian Resources.

The role of both the county council and town councils have been imperative in supporting mining projects. In February 2017, Callington town council backed plans to begin exploratory drilling at the Kelly Bray site, forming part of the proposed Redmoor mine site (Okehampton Times, 2017). Whilst the project, led by New Age Exploration (NEA) is in its early stages, the company has a 15-year exploration lease, with the option of two 25-year mining leases (NEA, 2016). More widely, Cornwall Council has been imperative in supporting renewed mining operations. Material released by Strongbow Minerals in 2017 confirmed that Cornwall Council had permitted an active mining licence to the South Crofty mine valid until 2071, ratifying their rational for investment.

Mineral planning policy was added to the local development plan for Cornwall in 2009, as Cornwall Council recognised the need to ‘Support metal extraction in response to market demand, including working within the AONB (Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty) and WHS’ (Cornwall Council, 2013). In 2011, Cornwall Council granted planning permission for the extension of underground workings and the construction of surface buildings. The council also supported plans to redevelop the mine site utilising EU funding as part of the Camborne-Pool-Redruth (CPR) regeneration scheme – one of 19 urban regeneration schemes across the UK, bringing £250m in investment to the local area (BBC News, 2011b). Under such planning, former mining areas would have been redeveloped to create retail outlets, affordable housing, and green areas – whilst land would have been allocated for the construction of a modern mine site (Cornwall Council, 2010). Such plans have now stalled due to the loss of grants, and the passing of work to the Cornwall Development Company (BBC News, 2011b). However, renewed mining operations will need to regenerate mining infrastructure – including processing and water treatment plants as agreed with Cornwall Council in 2011 (Strongbow Exploration, 2017).

Yet the work completed by the CPR regeneration scheme highlights the social challenges facing the area. Designed to rejuvenate economically deprived areas, CPR successfully promoted social sustainability through improving infrastructure, and developing community projects such as Heartlands – a community based heritage project. It is clear that Cornwall requires a diverse job market to promote employability opportunities within the region. This has been recognised by both Cornwall Council, and local urban regeneration schemes – which have both supported the notion of a renewed mining industry within the region. The creation of mining jobs, whilst relatively small in scale, will support employment in related support industries and supply chains, securing wider regional and UK employment. Wider UK based plans to begin mining processes in County Tyrone, and the successful plans to begin mining in Devon highlight the scope in the industry, and the positive impacts that limited industrialisation can have for social development.

EU Funding

With the loss of industry and subsequent investment, and an increasingly competitive job market, Cornwall has become reliant on funding from the European Union (EU) – a provider £1bn in funding matched by private investors, leading to £2.5bn in investment packages for the county (Morris, S. 26/06/2016b). Further EU funding for the 2014-2020 period is made up of two main funding streams: the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF), worth €437,472,735, and the European Social Fund (ESF), worth €166,234,129 (Cornwall Council, 2017a). Recent economic data published by Eurostat however, highlights that Cornwall is now the second poorest region within the UK (Inequality Briefing), and the future of such funding is now under pressure due to the decision taken by the UK to leave the European Union.

Cornwall Council utilises much of its EU funding for sustainability projects (Cornwall Council, 2017b). The council envisages Cornwall becoming a green exemplar region – through the extensive use of solar farms. Indeed, Cornwall Council has approved over 50 solar farms covering 1,600 acres of land (Morris, J, 2012) – the first of which was constructed at Wheal Jane, a former mine site. Such projects provide skilled work to the area – approximately 2,000 people are employed in the solar energy business in the South West, contributing £1bn to the local economy (Morris, J, 2012).

The emergence of renewable energy projects marks an increasingly sustainable future for Cornwall. The Green Cornwall Programme aims to support the growth of the renewables industry, allowing it to provide 15 percent of Cornwall’s power by 2020 – an increase of 13 percent from 2009 (Cornwall Council, 01/07/2013). Geothermal energy, offered partly as a result of mining operations will make up part of this provision. The emergence of a low carbon economy within Cornwall is further expected to expand on the 2,000 jobs already directly related to the solar industry, allowing for the creation of up to 10,000 green energy related jobs (Cornwall Council, 01/07/2013). This highlights a significant increase in the provision of jobs offered by a proposed renewed mining industry, and offers increased sustainable benefits, particularly for the longevity of employment and offering renewable energy for Cornwall.

European Union funding has been imperative in aiding local regeneration projects in Cornwall. Much of this funding has been geared towards the Camborne-Pool-Redruth regeneration scheme, renewing former industrial mine sites for public and commercial use. Heritage projects such as the Heartlands centre, have seen funding through £22.5m in Lottery grants, and financing through Cornwall Council through EU funds (Heartlands, Online). Whilst such projects have created green spaces and visually improved wasteland areas, core problems such as job creation have not been effectively met. Indeed, the out of work benefit payment within the Camborne-Redruth area is 17 percent, higher than the rate of Cornwall as a whole, which stands at 12 percent, whilst unemployment stood at 23 percent (Cornwall Council, January 2012).

As such, there is a social desire for the reworking of mines in the area, in order to improve social aspects and boost the local economy. Strongbow Exploration notes that the ‘development of the mine should form a fundamental part of the existing plans to re-generate the Camborne, Pool and Redruth area, by providing much needed, well-paid, permanent jobs as well as enhancing the visual impact of the mine site following decades of neglect and under-investment’ (Strongbow Exploration News, 2017). Cornwall Council recognises that the safeguarding of metalliferous resources in the area is crucial for potential future usage (Cornwall Council, January 2012).

The Role of Tourism

It remains clear through examining case studies, that renewed mining in Cornwall will directly impact the tourism industry – approximately 1m people visit the region each year. This is particularly true in the case of Marine Minerals, whose plans threaten the regions surfing industry – of both regional and national importance. The tourism industry predominantly offers low paid, unskilled, part time and temporary employment to students and mothers looking to contribute to household incomes – due to flexibility with schooling hours. Traditionally, tourism was seen as a seasonal industry, offering high employment rates in the summer months, and increasingly high unemployment rates during winter periods. Whilst this is still the case, such differences have narrowed due to increased visitor numbers to Cornwall. In the first quarter of 2015, there was a 15 percent increase of spending by foreign visitors to the South West (Economist, 2016), due to the increasing number of attractions – such as the Eden Project and Tate art gallery.

Mining history has directly shaped the Cornish tourist industry, particularly through the granting of World Heritage Site (WHS) status in 2006 (Wheeler, 2014, 22-32). Indeed, UNESCO (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Educational Organisation) called prospective mining operations to be halted during 2012 (BBC News, 2012) at the South Crofty project, due to fears of damaging listed structures. Mining operations have impacted WHS globally; Australian based Zambezi Resources threatens the Zambezi national park of Zambia – a category two protected area, which boarders the Mana Pools of Zimbabwe, a registered WHS (Kings, S. 2014). The mining history remains as a strong Cornish identity and culture, and the awarding of such status, coupled with the opening of related museums adds additional depth and scope to the tourist industry.

Indeed, the widespread knowledge and media usage of this culture has greatly aided Cornwall. The BBCs Poldark drama series, partially set on Cornwall’s historic tin coast is responsible for a 50,000 visitor increase to the Levant mine (BBC News, 16/02/2017) – one of Cornwall’s many mining museums. As part of one tourism survey, half of the respondents noted that they had watched the series, with one fifth confirming that the series had prompted their visit (Morris, S. 2016b). Furthermore, websites such as VisitCornwall and accommodation website Stay in Cornwall have seen a 20 percent increase in web traffic since the airing of the drama (Cuskelly, C. 2016).

Toni Carver, editor of the local paper the St Ives Times and Echo notes that whilst tourism has had positive impacts, ‘the downside is that by selling our souls to tourism we’ve encouraged over-development. In the current economic climate, with locally unaffordable, very high property values, the traditional Cornish communities, shops and business not related to tourism are failing fast’ (Morris, S. 2016b).

The South Crofty project within Cornwall lies in a largely urban area, located away from areas frequented by tourists. Whilst the aim to renew mining at South Crofty will predominantly effect environmental sustainability, projects to recover tin from the seabed of Cornwall will directly affect tourism. Cornwall’s surfing industry is nationally recognised, and sustains approximately 1,600 jobs in Cornwall – which may be directly effected through Marine Minerals plans to extract sediment from coastal areas.

Conclusions

Whilst Cornwall has falling unemployment rates, the county is in need of a skilled job market – offering sustainable wage payments to a region ranked as the second poorest in Europe. Nearly 400 direct jobs will be created as a result of renewed mining operations, with scope for more in related support industries. This may offer short term employment, as the industry fundamentally relies on a finite resource which once exhausted, will cause the industry to decline. There is widespread support for the return of the industry – from both Cornwall Council and town councils, regional development groups and the populace. Yet, whilst the mining industry may have a positive role to play in the social development of Cornwall, it must be noted that the industry historically failed due to economic barriers which acted as the causation of localised employment and emigration from Cornwall.

A renewed mining industry may have negative impacts for developing aspects of the modern Cornish economy. Non-traditional approaches to mining – such as plans put forward by MML may affect Cornwall’s tourist and surfing industry, arguably a new economic pillar within the region. Whilst it is apparent that it is commercially and to an extent socially viable for such projects to progress, mining companies such as MML must respect the diversity of the Cornish economy.

The economic sustainability of renewed mining activities

The return of heavy metal mining to Cornwall has been discussed through local Cornish media since the closure of the regions last working Tin mines; Geevor Mine in 1992, followed by South Crofty, in 1998 (Crace, J, 2008). Whilst previous Cornish mining produced a variety of metals, the mining of tin remains the focus of renewed operations in the region. Historically, many mines operated on a relatively small scale – as privately run operations, although it is estimated that Dolcoath mine produced minerals worth £10m between 1790 and 1920 (Cornwall Focus). Mines such as South Crofty, formed through the amalgamation of smaller operations, produced over 800,000 tonnes of copper and 250,000 tonnes of tin between 1845 and 1913 – a fifth of Cornwall’s recorded copper output and a third of the county’s tin production at the time (Exeter University, 1996). In its lifetime, South Crofty would produce over 400,000 tonnes of tin (Strongbow Minerals, 2017) – continuing to act as the region’s main producer of tin.

Whilst tin remains a finite resource – limiting the longevity of mining operations, the economic sustainability of mining projects can be identified as the main barrier for investment into the region (Buckley, J.A, 1982). Whilst market competition and initial investment remain as barriers, it is crucial to note that mining proposals are coming to fruition in other areas of the United Kingdom.

The China Clay Industry

It must be noted that whilst the production of heavy metals in Cornwall has ceased, the Cornish mining legacy continues in the production of China Clay – notably utilised in the production paper (Murray, H. 2016, 31-33) porcelain products, and in the cosmetic industry. This has seen investment from the French based mining company IMERYS, securing employment and providing economic benefits to the Cornish economy. China Clay, alongside traditional metal mining became one of Cornwall’s main exports, having first been discovered at Tregonning Hill in 1746 (Selleck, A.D. 1978). An estimated one hundred and twenty million tonnes of China Clay has been extracted, with reserves expected to last in excess of one hundred years (Cornwall-Calling) – securing a viable future for mining activities, a commitment ratified through the opening of renewed mine workings by IMERYS during 2012 (BBC News, 2012).

Whilst the industry has declined – due to a shift in production to Brazil due to lower production costs, it is notable that its prevalence maintains approximately two thousand jobs (Cornwall Guide) for the county. Furthermore, the industry is credited with contributing £130m annually to the UK economy – with Cornwall providing 88 percent of this, making China Clay the second most valuable mineral export of Cornwall (Cornwall Council, Technical Paper, 7-9).

The Wider World

To further understand the sustainable considerations behind such projects, the wider world must be examined. Upon examining the production rates for tin, it is apparent that China remains as the dominant world producer, producing 125,000 tonnes of the mineral in 2014, whilst Indonesia produced 84,000 tonnes, and Peru produced 23,700 tonnes (Anderson, C.S, 2015). The Hemerdon project situated in Devon primarily produces tungsten, yet produces tin as a by-product- producing approximately 750 tonnes in 2016 (Quoted Data, 2017), highlighting the limited scope of renewed operations. Whilst projects in Cornwall hope to produce up to 2,000 tonnes annually (Matthews, C. 2014), they cannot fully compete in the global commodities industry. Furthermore, Anderson notes the growth of the recycling of metals, with tin recycling rates within the US increasing to 14,000 tonnes in 2014, thus lowering the demand for newly mined metals (Anderson, C.S, 2015).

Cornwall will be largely reliant on Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) in order to rejuvenate its mining industry. Brexit is likely to have a negative impact on FDI into the UK; empirical analysis showsthat FDI is likely to fall by up to 22 percent, damaging UK productivity and lowering real incomes by up to 3.4 percent (Dhingra, S. et al, 2016). This process may be particularly damaging for Cornwall, which has been heavily reliant on EU funding for the rejuvenation of areas economically damaged by the loss of mining and related support industries. For both Cornwall and the UK as a whole, investment will come from Australian and Canadian based mining exploration companies. As these companies will operate within the UK, British taxation laws apply. This includes corporation tax and VAT, as well as national insurance and PAYE contributions from employees (Deloitte, 2015). The South Crofty project is anticipated to generate annual corporation tax payments totalling £38.5m, based on a tin price of $10/lb.

Overseas companies operating within the UK are subject to law and overseas company regulations based upon the area of investment – Northern Ireland, Wales and England share the same regulations for overseas investment, whilst Scottish laws differ (UK Government, 2009). This is crucial for this study, as it highlights that the case studies previously identified are subject to the same laws and regulations. As such, sustainable development principles such as environmental protection schemes, increased employment rights and the development of work based apprenticeship schemes are protected (UK Government, 2009), allowing the continued sustainable development of Cornwall. Furthermore, works undertaken by foreign based companies such as Strongbow Resources will be scrutinised by the EA and Cornwall Council, both of whom are committed to the sustainable development of the region, and hold the power to remove mining and water licences if regulations are broken.

Historically, mining projects within the UK suffered from limited scope. Minerals within Cornwall are formed in lodes – narrow fissures in rock in which ore can be found. Cornish metal mining therefore predominantly took place in underground tunnels – similar to modern proposals by both Dalradian and Strongbow. Whilst mineral deposits at Hemerdon allow for open cast mining, investors such as Wolf Minerals have struggled to profit from such operations, making a net loss during 2015, and requiring increasing loans (Ford, A. 2016) to allow for the continuation of activity. The export market of the UK commodities industry is pinned to Chinese growth, and therefore its manufacturing output. Whilst Chinese growth slowed during 2016, commodity prices have increased due to increasing Chinese imports of minerals – to preserve mineral reserves.

In February 2017, strong trade data from China led to increased metal prices – allowing the FTSE 100 index to climb 25.62 points. Indeed, the shares of mining corporations dominated this rise, with companies such as Rio Tinto rising 5.6 percent (BBC News, Business, 2017). Whilst projects based in the UK can reach the demand for home markets (Wolf Minerals, 2014), it remains clear that the production rates of increasingly industrialised countries limit the capabilities of export markets. This is due in part to entrenched mining infrastructure, ease of access, and limited health and safety and environmental mitigation policies.

The Economic Sustainability of Heavy Metal Mining

The return of heavy metal mining in Cornwall has been considered by a wide body of mining co-operations since operations ceased. Plans currently consist of renewed operations at South Crofty, Redmoor and the proposed dredging of seabed environments. Such projects total in excess of £120 million in direct investment into Cornwall. High start-up costs and initial investment may act as a barrier to renewed mining activities – Strongbow plans to contribute up to £77m in infrastructural improvements and environmental protection schemes (Barton, L, 2016), whilst noting that the sinking of modern mine shafts would cost up to $40,000 per meter (Strongbow Exploration, 2017).

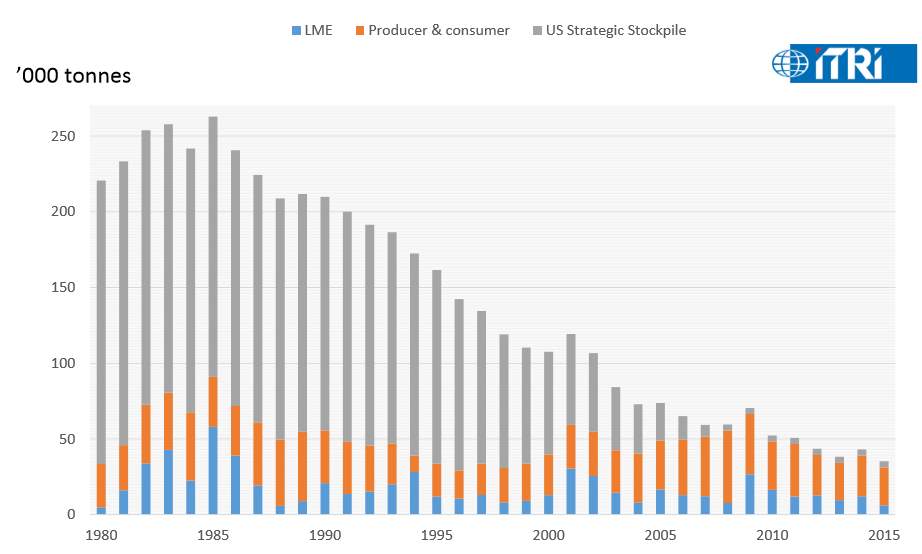

The tin crash of the late 20th century and the mineral exploration of colonial territories signalled the end of UK metal mining. Cornwall however, houses known ore reserves, and increased demand for metals due to the growth in the technologies industry, and declining US strategic stockpiles has aided the increase in commodity prices (Barton, L. 2016a) – as demonstrated in the following graph (Strongbow Exploration, 2017). During the latter half of the 20th century, US tin stockpiles acted as a barrier to heavy metal mining within Cornwall, aiding the decline of the industry.

George Eustice MP, who holds his constituency in Camborne and Redruth and remains as the UKs Minister of State at the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs supports the return of mining in the region. Economic development remains at the core of commitments to the area, however, he recognises that global commodities prices historically acted as a barrier to the industry. In 2011, regarding mining plans he wrote:

‘Can they buck that trend now? The first thing to say is that these plans are for a modern, state of the art mine that would be unlike anything that has gone before. It would be the most modern mine in the UK today. They would not just be mining for tin, but also Zinc, Copper and other trace elements simultaneously. The most important and sought after of these trace elements is Indium – a crucial in the production of modern touch screen technology. Most of the world’s supply of Indium is controlled by China. That would change if South Crofty re-opened.’ (George Eustice, 2011).

Known resource limits in Devon and County Tyrone highlight guaranteed mine lifetime of up to ten years, with potential further expansion remaining a viable future option. Though extensively mined for at least 300 years, the projected service life of South Crofty is estimated to be ten years, depending on global markets (Barton, L, 2016a) – although there is potential to extend beyond this due to in-mine exploration. Furthermore, a renewed mining may extend to the nearby mines of Dolcoath and Carn Brea, both of which remain open to redevelopment activities and would therefore share the same underground and surface infrastructure (Strongbow Resources News, 2017).

The above map highlights the underground boundary of mining operations, and the location of the mine (Strongbow Exploration, 2017).

Further supporting the notion of the longevity of operations is the factor that Cornwall houses a diverse range of minerals, including lithium. Lithium holds uses in green technology, particularly in li-eon batteries – utilised in the growing electric car market. Indeed, Goldman Sachs predicts the sale of up to 20.5m electric cars between now and 2025 (Bleischwitz, R. 2017). Economically, the industry faces challenges – Bleischwitz argues that automotive companies may continue to promote traditional car models, whilst consumers may lack confidence in such technology. However, Cornwall houses Europe’s only known lithium resource, creating a valuable and viable industrial prospect for the region.

The global demand for minerals is due in part to the growth of the technologies industry. Strongbow data highlights that during 2014, 43.5 percent of the worlds tin was used in electronic solders, whilst 14.7 percent was utilised in the production of products such as tinplate- due to its anti-oxidising properties (Strongbow Exploration, 2017). Tin concentrate is currently worth approximately $15,000 – $20,000 per tonne, and data from the International Technological Research Institute (ITRI) suggests that tin prices are projected to increase to $30,000 in 2025, due to the weekly supply of the mineral decreasing from 15,000 tonnes to 5,000 tonnes (Strongbow Exploration, 2017). Global demand for tin is predicted to reach 30,000 tonnes per week in 2020, with current mining operations predicted to provide approximately 5,000 of that figure (Strongbow Exploration, 2017) – highlighting market opportunities for renewed Cornish operations.

The graph below demonstrates the increase in tin prices during 2016 (Strongbow, 2017).

Both South Crofty and Redmoor are recognised as being among the top five tin deposits by grade (metallic content of ore) in the world (Proactive Investors, 2017) – thus increasing the economic viability of renewed mining.

Mine Closure

Mining companies have an obligation to invest in planning for the maintenance and upkeep of mine sites post closure. Closure works are progressively carried out during the lifetime of the mine, whilst adhering to a five year aftercare programme in compliance with the mineral Planning Authority (Barry, J. et al, 2017). Such a programme is designed to allow for mine workings to be made safe, and environmental management schemes such as water treatment works to be maintained. Both underground and surface closure requirements stipulate that notice from mining companies, in this case Strongbow Resources, must be given at least two year prior to the cessation of mining activities. This is to allow for the adequate planning of land reclamation to remove contaminated materials and build biodiversity through the phased reclamation of land. Such work would be carried out by Strongbow Resources, utilising closure funding accrued over the life of the mine on a cost per tonne processed basis (Barry, J. et al. 2017).

Whilst securing investment from Strongbow into the site post-closure, no mention is made of how water treatment works will be funded in the long term, or how employees will be supported by the company. Whilst renewed employment within a rejuvenated mining industry within Cornwall will generate increased tax and national insurance contributions, whilst developing transferable workplace skills – in the form of mechanical, managerial and technological areas, mining cannot guarantee sustainable employment opportunities for Cornwall.

Conclusions

Whilst global price fluctuations dictate commodity prices, it is clear that metal prices are rapidly increasing. This is in part due to the growth in the technologies industry, which utilises tin in the manufacturing of electronics. Whilst large known mineral reserves facilitate the return of a mining industry to Cornwall and the increased longevity of operations, it must be noted that the finite nature of the resource limits the future scope and the development of the industry. This factor critically undermines the economic and social sustainability of Cornwall, and limits the role that the mining industry will play in the future of Cornish economic development. Furthermore, the limited role of Strongbow post closure highlights the unstable nature of the industry in guaranteeing job sustainability, thus affecting the social and economic viability of mining for Cornish economic development.

The environmental sustainability of renewed mining activities

Understanding the environmental impacts of proposed plans remains imperative for drawing conclusions over the sustainability of mining projects. Historically, mining ventures within Cornwall did little to mitigate environmental impacts, leading to localised pollution. As such, waterways remain polluted with heavy metals such as arsenic, whilst areas of the coastline have yet to recover vegetation cover due to mineral processing activities. Mining companies must adequately deal with mine waste, listed as ‘Mineral working deposit’ in the Town and Country Planning Act 1990. It is defined as ‘any deposit of material remaining after minerals have been extracted from land or otherwise deriving from the carrying out of operations for the winning and working of minerals, in on or under the land’ (British Geological Survey). Mining companies must comply with stringent environmental guidelines, working with organisations such as the Environment Agency (EA). This has been particularly successful in both County Tyrone and Devon – leading to the granting of permissions for the return of mining at the latter. Whilst traditional mining proposals have noted the environmental impact, it is clear that more must be done. This essay will examine how environmental sustainability may act as a barrier to renewed industrialisation.

The potential impacts of mining on developing industries

Within Cornwall, environmental sustainability remains as one of the main barriers to the return of a viable mining industry to the region. One of the most controversial mining plans for Cornwall is the proposed mining of seabed environments on the county’s northern coastline. Seabed sediment in this region is considered to be rich in minerals due to poor historical recovery rates of metals – which saw sediment deposited into local rivers and streams. Whilst severely impacting the social sustainability of the surfing industry, environmental impacts must also be examined. Individuals such as Andy Cummings, campaign director of Surfers Against Sewage (SAS), argue that ‘Disturbing and removing significant amounts of sediment has the potential to devastate the fragile and complex environments that support surfing, tourism and fishing’. SAS further notes that disturbing sediment close to river mouths could reactivate pathogens associated to sewage and heavy metals (Morris, S. 2013). Therefore, regional biodiversity in the area may be effected, putting organisms such as seals, sharks, dolphins and crustaceans at risk (Iivonen-Gray, K. 2013).

The surfing industry is of critical importance to the wider UK economy. SAS has identified that the surfing population within the UK numbers 500,000 – directly contributing up to £1.8bn annually, increasing to up to £4.95bn when indirect and induced economic effects are accounted for (Mills, B. 2013). The surfing industry of Cornwall is the largest of its kind within the UK. Data from SAS suggests that the surfing industry within Cornwall sustains 1607 jobs, as well as contributing £154m to the Cornish economy – an increase of £90m from 2004 (Morris, S. 2013b). Whilst highlighting the economic development of the industry within Cornwall, this figure does not account for annual festivals such as Boardmasters, which contributes a further £17m annually (Mills, B. 2013). Therefore, plans proposed by MML may have far reaching sustainable impacts – threatening environmental sustainability, social security, and the economic development of the region.

Indeed, MMLs sustainability policy recognises the potential impact that mining activities may have on aquatic environments. Technology utilised in the mining process will be engineered to mitigate against environmental degradation, whilst removing heavy metal toxins from the environment may prove positive for biodiversity (MML, Sustainability Policy). Furthermore, whilst MMLs operations will doubtless effect the contours of sediment within the area –one of SAS’ prime concerns, it must be noted that the movement of sand is a naturally occurring process – affected by the tides, currents and storm conditions (Akiyama, Y. et al, 1999). Whilst Marine Minerals’ sustainability policy recognises the need for a low carbon footprint – utilising technology such as Skype for conferences, it is clear that concerns have been raised over the environmental sustainability of the project itself. This is largely due to the unproven methods surrounding the project, which, though undergoing trials, has yet to see full scale production. Both the environmental and social risks may greatly outweigh the benefits of the project – leading to environmental issues, and disruption to Cornish industries dependent on the aquatic environment. Therefore such projects may prove unsustainable for Cornish economic development.

The issue of mine water pollution

It can be argued however, that renewed mining will improve environmental prospects in the region. Currently, waste water containing toxic metals from the South Crofty mine is discharged into the Red River (named as such due to its historical association with pollution) – eventually meeting the sea at Gwithian Bay, one of Cornwall’s tourist hotspots (Pirate FM, 2017). Water pollution has effected Cornwall before; the 1992 Wheal Jane disaster saw the release of approximately 50 million litres of acidic, metal laden water into the environment – including highly toxic metals such as arsenic and cadmium (Younger, P.L, 2002). Whilst socially, the disaster severely impacted the regions emerging tourism industry, environmentally, the disaster instigated the county wide recognition of the need to treat waste mine water. This resulted in a long term plan utilising a passive reed bed storage system to treat waste water (Hamilton, Q.U.I, et al, 1999), a system which has now been replaced by a modern treatment plant. Further examples of successfully implemented water treatment systems within the UK include the Clydach Brook of Wales – historically effected by the coal mining industry (Environment Agency, 2008).

The legacy of heavy metal mining has had environmental impacts across the globe. The Britannia Mine, located in British Columbia, Canada has seen similar impacts to Cornwall with regard to water pollution. Surface run-off and mine drainage led to the significant pollution of local water courses – approximately 450 kilogrammes of Copper ore was deposited daily, directly impacting the Salmon industry (Ministry of Forests, 2001). As with former mining operations within the UK, this has required significant measures to rectify heavy metal pollution – including water treatment plants and land reclamation (Mills, C. 2006).

This is a widespread issue within Cornwall, research has shown that at least 600 private water supplies contain levels of arsenic above guide lines set by the World Health Organisation (BBC News, 2016c). Drinking water containing arsenic over an extended period of time may have similar effects to passive smoking. Indeed, following the Wheal Jane disaster, arsenic concentrations increased dramatically, severely effecting public and environmental health (Hunt, L.E, 1994). Such issues are not limited to Cornwall, proposed gold mining operations in Tyrone require the use of cyanide, which can be environmentally detrimental upon entering water courses.

Toxins leaching into the environment from both mine tailings pose significant risks to local environments. Both biodiversity in river corridors and the numbers and diversity of invertebrates may be severely impacted by heavy metal mining (Flachier, A. et al, 2001). Whilst low pH conditions may damage the gills of fish, acidic conditions in aquatic environments may increase both the solubility and toxicity of metals such as copper, lead, zinc and cadmium (EA, 2008) – which were historically mined to some extent within Cornwall (Cornwall Council, 2013). Whilst water treatment, provided by Strongbow may aid the improvement of biodiversity in Cornwall’s Red River, aquatic diversity may not be fully restored (Buyer, J.S, et al, 2002).