Reconstructing Hong Kong: The Influence of Location and Cinematic Space in the Films of Wong Kar-wai

Info: 10126 words (41 pages) Dissertation

Published: 20th Jan 2022

Tagged: Film Studies

Abstract

For years’ artists have been creating work that represents their cities and their homes, there is something distinctly personal about the relationship between the artist and their city, and how they represent that feeling to the rest of the world. My dissertation will be investigating this idea through the medium of cinema, specifically through Chinese director Wong Kar-Wai and his visual representation of Hong Kong.

My aim is to detail the relationship between the director and his city cinematically, while focusing on the idea that most important aspect of Kar-Wai’s films is infact its location. Wong constructs the feeling that Hong Kong’s tendrils of influence looms over the cinematic urban landscape, blocking our views and forcing interactions between characters. Wong almost personifies the city of Hong Kong, as if the background and foreground of the claustrophobic settings are another character in the screen, forcing the viewer to focus on every aspect of the scene. In essense, my intention is to showcase the identity of Hong Kong throughout different periods of time, discussing shifts in cultural identity and how Hong Kong’s history influences it’s present and future and how all these ideas are portrayed in the cinema of Wong Kar-Wai.

Figure 1 – Screenshot from 2046 (Kar-Wai, 2004)

“That era has passed.

He remembers those vanished years.

Nothing that belonged to it exists any more.

As though looking through a dusty window pane,

The past is something he could see, but not touch.

And everything he sees is blurred and indistinct.”

(In the Mood for Love, Wong Kar-Wai, 2000)

Table of Contents

Introduction

A History of Hong Kong and its Cinema

1839 – 1860

1909-1930

1930’s

1940’s

1950’s

1960’s

1970’s

1980’s

1990’s

Present to 2047

Chapter 2 – The Significance of Location

Memoirs of Shanghai

Hong Kong in Globalised Motion

Chapter 3 – Hong Kong Stranded in Time

Layers of Time

Conclusion

Bibliography

Filmography

Introduction

“I believe that geographical accessibility is a deciding factor for human relationships. We don’t really choose our friends, people who are around us become our friends”

– (Kar-Wai, 1997)

It has been said about film that a significant portion of cinematography is about the location, and that the location of a scene plays an equally important role to the story as the characters in the frame. But what happens when the spatial intimacies of location and cinematic space on screen become the driving force in the narrative of the character’s life? This notion is one I wish to explore over the course of this dissertation, my aim will be to examine the numerous ways in which Chinese film director Wong Kar-Wai uses the location of Hong Kong repeatedly through out his body of work, attempting to unravel the relationship between a director and his city cinematically.

Through detailed analysis of specifically selected Wong Kar-Wai films, I will be exploring a reflection of his personal Hong Kong that he shares with us vividly on the screen and how he reconstructs and appropriates the city in order to potray different periods throughout it’s history. Focusing on the idea that most important aspect of his films is infact its location and time within the claustraphobic enviroment; blocking our views and forcing interactions between characters.

In order to do this, I will be seperating my thesis into distinctive chapters, each discussing a different aspect of Wong Kar-Wai’s productions and apply critical theories that I believe individually contribute to the aesthetics and feel of his fictional Hong Kong. To aid in the exploration of my thesis, I have selected four films from Wong’s oeuvre to run along side my discussion of these theories; In the Mood for Love (2000) and 2046 (2004) which are both set in 1960’s Hong Kong, and Chunking Express (1994) and Fallen Angels (1995) which are both set in the 1990’s.

I believe these films best illustrate a perspective of Hong Kong through the eyes of two different generations in Hong Kong’s history and will provide the best insight into Hong Kong’s complicated history and uncertain future, as well as understanding why Wong chose to convey these specific vingettes of the city.

In the first chapter I will observe and discuss the history of Hong Kong and its social and political landscape, detailing significant dates in history that lead up to its current post-colonial status. Parallel to this time line I will consider the development of Hong Kong’s cinema examining the important directors at the time and how they visualised the location of Hong Kong, as well as the cultural climate of the time and how they created the conditions to allow the New Wave cinema to formulate, which birthed directors such as Wong Kar-Wai.

In the second chapter, I will illustrate the importance of the cinematic space of Hong Kong in Wong Kar-Wai films. I will study how he uses cinematic space and repeated locations where his characters interact. I will be claiming that location is the most essential aspect of his films and that the narrative structure of his films revolve around the urban jungle of Hong Kong. To convey this point, I will select scenes from my chosen film list to use as examples of how he represents localism and the cultural identity Hong Kong through different generations in the 1960’s and the 1990’s and how they differ.

And in my final chapter I will be contemplating the concept of time in Kar-Wai’s films, discussing his use of fragmented and unlingering time. The bulk of this chapter will consist of the exploration into the concept of memory, how his characters seem to be trapped in a state of memory and what that means as a cultural representation for the population of Hong Kong. As well as discussing Ackbar Abbas’s theory of ‘Deja Disparu’ and how Wong Kar-Wai rebels against this notion by portraying Hong Kong in constant motion, no past, no future just an occupation of the in-between state.

A History of Hong Kong and its Cinema

When writing about Polynesia, Jeffery Geiger said that first you need “to fully understand our own cultural imaginings of Polynesia, we need to look carefully at where those texts came from… thus this book starts by looking backwards” (Geiger, 2007, pg.13.) This extract perfectly sums up the reason for choosing to include a timeline of Hong Kong’s cultural and cinematic history as my first chapter. Simply because I believe to fully understand the way in which Wong Kar-Wai uses Hong Kong in his films, you must first understand how Hong Kong’s complicated past influences its present. As well as how its cinematic history allowed directors such as Wong to flourish and create films that expresses his personal views towards his city in a unique way. Hopefully, by the end of this chapter you will be able to visualise a clear portrait of what Hong Kong was, is and could be, to be able to effectively draw comparisons and contextually analyse the locations we see on screen.

1839 – 1860

To start off the timeline I believe it would be best to begin with the most influential change in Hong Kong’s history, in 1842 when China cedes the island of Hong Kong to Britain as a result of the First Opium War between 1839-1842. This war between the United Kingdom and the Qing Dynasty of China occured as a result of the strict trading rules imposed by China. This meant that European demands for Chinese goods such as silk and tea became a problem for the ever expanding British. Following the surrender of the Chinese and the signing of the ‘Treaty of Nanking’, Britain managed to negotiated an island just off the coast of mainland China, to create a trading post that would be allowed to function under British rule and more importantly British trading laws so that it could trade freely with selected parts of China.

Unfortunately, this was not the end of the opium wars. After the first war had concluded, British and Chinese relations were obviously still delicate. The British desired a more bountiful agreement than they had already received, they wanted to open full scale trading in the mainland of China and expand their overseas markets. This prerequisite for expansion caused the second of the Opium Wars, starting in 1856. After witnessing the first victory against China, the French had decided they wanted to open trade routes into China as well, therefore they created an alliance with the British against the common enemy. This led to several battles in mainland China, eventually concluding in 1860 with the ‘Treaty of Tianjin’ which granted more ports, inland access to traders and a 99-year lease (concluding in 1997) on several islands including Hong Kong, which caused an exodus of Chinese migrants from the mainland to settle in the new British ruled colony.

The Opium Wars left China in an extremely weak position and ushered in an era of humiliation for its population after signing several treaties that were deemed unfair and immoral. This became commonly known as the first of ‘The Unequeal Treaties’ which the Chinese still hold resentment towards the west for.

1909-1930

The year 1909 marked the date of the official start of Hong Kong cinema, beginning with the first locally directed production, a short silent film titled Stealing a Roast Duck (1909, Shao-Bo) by Chinese director Liang Shao-Bo. While this techinically marked the first official film created within the city, it has been long disputed that the cinema timeline should begin with Hong Kong’s first ever full length feature, Rouge (1925, Pak-Hoi) directed by Lai Pak-Hoi. Interestingly enough Lai Pak-Hoi started his career as an actor and was involved in the previously mentioned Stealing a Roast Duck. These first few early pioneers really opened the doors for Hong Kong’s cinema and created a pathway for future productions to be created, as well as garnering an audience who want to see more locally produced films. These pictures set in motion the means to build up Hong Kong’s film industry into what is is today.

1930’s

The 1930’s brought a huge change to cinema on a global scale, the invention of sound brought ‘talkies’ to the big screen in Hollywood. The rest of the world followed suit, including Hong Kong and Shanghai who had been receiving productions from the West and wanted to impliment this new technology into their own films. This came with some political complications, the problem being that China has several different spoken dialects across the country, the two main languages being Cantonese and Mandarin. At this time the Chinese Nationalist Party were pushing Mandarin as the official spoken languge of China, even going as far as to ban the genre of Wuxi productions, a popular Cantonese medium of entertainment.

The most widely spoken language in Hong Kong at the time was Cantonese, meaning that naturally Cantonese productions were more popular in that region. Naturally this led to the first talkie Cantonese talkie created in Hong Kong (although actually produced in Shanghai), an adaption of an opera directed by Tang Xiodan, Platinum Dragon (1934, Xiodan). Subsequent to the huge success of this film on its release in Hong Kong, the director, Tang Xiodan decided that ‘this film proved that the future for his studio lay in Hong Kong, and over the next two years he shifted his base of operations from Shanghai to the British territory’ (1988, Fonoroff)

1940’s

Following almost a decade of succesful film productions, Japan invaded Hong Kong in December of 1941, succeeding the start of the Second World War. The invasion began on December 8th with a battle lasting 18 days, concluding when the heavily outnumbered British and Indian soldiers surrendered the island to the Imperial Japanese. Japan occupied Hong Kong for 3 years and 8 months until their eventual surrender at the end of the war. During this time many residents of Hong Kong fled to mainland China due to food shortages, causing the population to drop from around 1.6 million to only 650,000. Film making during this time had almost completely halted, apart from some efforts to create colaborotive propaganda films with the Japanese, but they were met with too much confrontation. Instead the Japanese forces destroyed the majority of existing Hong Kong cinema, incredible amounts of film stock were melted down for the silver nitrate within them for military use. It has been said that only four of an estimated 500 films survived.

By the mid 1940’s Britain had re-established its government within Hong Kong following the Japanese surrender, many of the residents who fled during Japan’s occupational period flooded back into Hong Kong. Followed a few years later by residents from the mainland escaping the Chinese civil war between the Nationalists and the Communists who were attempting to restore singular control to China (these two parties had been fighting since 1927, but the Sino-Japanese War forced a hiatus from 1937 until 1946 when the battle continued). This huge influx of residents meant that Hong Kong’s film industry was not only able to return to regular film production but able to thrive and make drastic changes to its infastructure, reviving the industry with new talent from the mainland.

In 1949, the Chinese Communist party came out victorious in the civil war, meaning that China had now become a communist state. The new government saw Chinese productions as an extremely important tool for proaganda, meaning that all pre-communist Chinese, Hong Kong and Hollywood productions were banned. Instead they focused their efforts into movies surrounding the average working man. The first example of this is in Bridge (1949, Bin) in which factory workers are building a bridge over a river so that communist forces can cross, the workers are lacking morale but one man inspires his fellow workers to complete the project for the communist war effort. This film set a standard for the themes that would dictate China’s new communist socialist cinema.

1950’s

Due to these new restrictions on China’s cinema, the more lenient Hong Kong became a hub of film production as a result of its British colonialism, producing films in both Cantonese and Mandarin, although Cantonese films were still percieved as second class as apposed to Mandarin spoken productions due to the difference in quality. In spite of this, throughout the 50’s Cantonese film production flourished, with a regular output of up to 200 productions a year. Unlike Mandarin productions, which were usually opera’s and martial arts films, Cantonese films explored different methods of film making and produced high quality literary adaptations such as, New Dream of the Red Chamber (1951, Wancang). A modern day adaptation of what is considered one of China’s greatest classical writings under the same name, written by Cao Xeuqin in the 18th century in the middle of the Qing Dynasty.

Thanks to the mass migration of refugees and talent into Hong Kong, by the mid 1950’s it’s population had reached more than 2 million, becoming one of the most densely populated areas in the world. With this huge amount of growth in a short amount of time, Hong Kong set out to transform its territory from a British trading outpost, to a hub of industrial manufacturing. Unfortunately, due to the smaller size of Hong Kong a large number of the residents were still without housing. This caused an emergency housing program which set in place plans for several highrise buildings with large numbers of housing in a small amount of space, renovating Hong Kong into how we percieve it today, a towering concrete jungle.

One of the buildings built during this time was the Chunking Mansions, a 17 story building that houses more than 5000 people. This building would go on to feature heavily in some of Wong Kar-Wai’s productions such as Chunking Express (1994) and Fallen Angels (1995).

1960’s

By the 1960’s Hong Kong’s manufacturing industry had grown significantly and found great success, transitioning into Hong Kong’s biggest financial income. Large amounts of it’s population were being hired as the workforce, creating a production golden era in the territory. This period is widely considered the biggest turning point in Hong Kong’s economy.

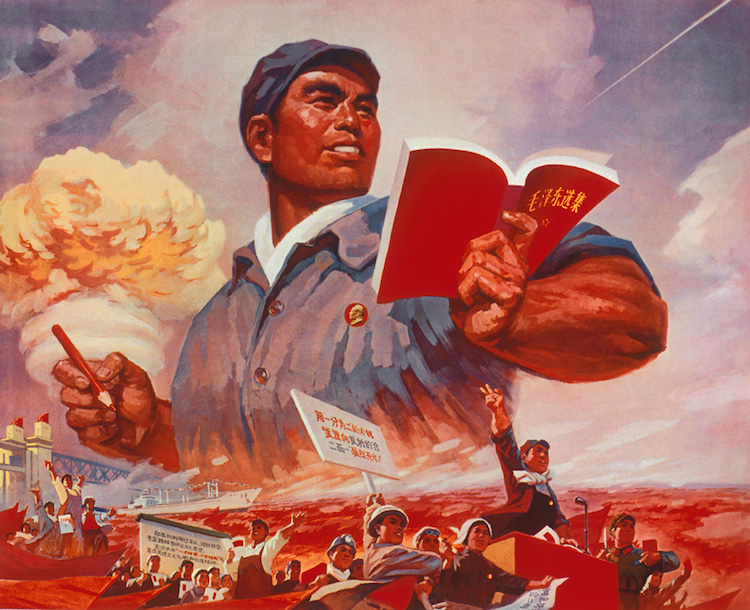

While Hong Kong were enjoying the benefits of economic success, over in mainland China the communist party, led by Chairman Mao, had begun what they called ‘The Cultural Revolution’ in 1966. The revolution took place as a result of Mao struggling to retain communist power in China, he believed his power was slipping away because of captalist influences across China, as well as what he aptly named the ‘Four Olds’; Old culture, Old customs, Old habits and Old beliefs. He thought that these four olds were counter revolutionary and set out a plan to destroy any reminence of ancient chinese culture and art, even going as far as to close all the schools and universities in favour of a new educational system, a collection of quotes from General Mao in his Little Red Book, meant to inspire the revolution (Fig 2.)

Figure 2: Workers wearing a Mao badge and holding open a copy of the Little Red Book (1971, Revolutionary Committee of Tianjin)

After closing the schools, Mao recruited the youth of China to the Red Guard. It was the Red Guards primary objective to destroy the four olds in any way possible, publically humiliating, beating and in some cases, murdering anyone who looked well educated or of the bourgeois tendency. Over this period of time the Red Guard would turn in anyone who they believed to be harbouring capitalist beliefs or old ideals, including parents, teachers, doctors and political figures. This propelled China into social chaos. As a consequence of the unrest in the community, once again many residents relocated to Hong Kong, including Wong Kar-Wai, whose parents relocated from Shanghai to Hong Kong when he was just 5 years old during the late 60s.

The cultural revolultion eventually came to a close in 1976, coenciding with the death of Chairman Mao. With over 1 million people killed and even more imprisoned and humiliated, the reminence of the revolution remained in China for years after Mao’s death, creating long term consequences for its people and lead to the majority of the population losing faith in its government.

1970’s

The invention of television in the late 60’s completely changed the nature of the film industry in Hong Kong, with the growth in Cantonese television programmes, the Cantonese film industry struggled to stay relevant, the amount of Cantonese films produced in Hong Kong slowly decreased each year with Mandarin productions becoming more popular with the rise of imported Japanese Samurai films[1]. Eventually Cantonese cinema saw a revival of its industry with a demand for more realistic films about life in Hong Kong following the release of the extremely succesful Cantonese film The House of 72 Tenants (1973, Yuen) which was the biggest box office success of 1973 in Hong Kong, even surpassing Bruce Lee’s Enter the Dragon (1973, Clouse). This was a turning point in Hong Kong’s cinema, switching large film productions from the traditionally spoken Mandarin to the locally spoken Cantonese.

1980’s

By the 1980’s many different countries were finding that they couldn’t keep up with the onslaught of Hollywood productions, with Hollywood films being seen around the world, local productions couldn’t get the traction they needed to make their own cinema popular. All apart from Hong Kong who were able to thrive under what film critics would dub a new wave of cinema, with a group of around thirty filmmakers returning to Hong Kong with overseas western education, the most notable members of the first new wave were Allen Fong, Tsui Hark, Ann Hui, Alex Cheung, Yim Ho and Patrick Tam.

“This group of young people, like an irresistible force, stirred up a colossal wave when the film industry was at low tide and opened up new vistas”

- (2008, Chuek pg.9.)

The experimental nature of these films openened new doors for productions in Hong Kong, not just following the trends of popular themes such as violence and sex but films with unique ideas interesting themes about Hong Kong’s identity and imagery with abnormal recognisable styles that Hong Kong cinema hadn’t seen up until this point.

As this New Wave began to garner the attention of international audiences, a second wave of directors were brought to the forefront of Hong Kong cinema, one of the most important being Wong Kar-Wai. Although the second surge of the New Wave movement is just as prolific and important as the first, it could not have taken place if it had not been for the achievements of the first wave. Even in the case of Wong Kar-Wai who worked as an assistant director and scriptwriter for Patrick Tam, one of the original breakout directors from the first New Wave. Since his first film, As Tears Go By (1998, Kar-Wai), Wong has firmly established his precense across the film industry, not only in Eastern Cinemas but all over the globe, being one of the first directors to convey the localism of Hong Kong on a global scale. Later on in my thesis I shall go into more detail about how and why Wong Kar-Wai was so influential to Hong Kong cinema and how he changed the way audiences percieve his city.

As the 99-year lease of Hong Kong to Britain drew closer and closer to its return to China in 1997, the two countries began discussing the future of Hong Kong in 1984 and how it will deal with the intergration back into China. This deal obviously comes with various different problems for Hong Kong culturally, having lived under a capitalist system for around 156 years to return to a communist country will inherintely involve some complications. The two parties combatted this problem by signing a joint declaration on the conditions that Hong Kong will return to Chinese rule under the ‘One Country, Two Systems’ formula. This means that Hong Kong will become part of one single communist-led country but will still be able to retain it’s capatalist economic system and somewhat democratic political system for 50 years after the handover in 1997, coming to a head in 2047 when it will live under a fully communist government.

1990’s

In July of 1997, social anxiety for the future of Hong Kong was at an all time high as the inevitible handover of the colony to mainland China occurred. The One Country, Two Sytems rule was put into place and Hong Kong intergrated back into China. China appointed Shanghai-born shipping tycoon Tung Chee-hwa who had no previous political experience to govern the island. The population of Hong Kong were in a state of apprehension, while not inherintely defiant towards the changes, they were by no means compliant either. According to a survey conducted by the University of Hong Kong, only 3.1% of Hong Kong’s youth identify themselves as Chinese, while 93.7% identify themselves as Hong Kongers[2]. These figures indicate that the average resident does not possess a cultural identity to a singular country, but define themselves locally, caught between British and Chinese influences, this concept is best summed up by an extract from Mengyang Cui, who states:

“As a consequence of being colonized, people in Hong Kong are residents, but not citizens. Therefore, they do not possess ‘citizen conciousnesses’. The majority of Hong Kong people are Chinese, but due to its paticular history as a former British colony, the hybrid culture of West and East gives Hong Kong unique cultural characteristics” (Cui, 2007, pg. 13)

These ‘unique cultural characterists’ are present in all walks of Hong Kong life, even in the language used, although as previously mentioned it is a mainly Cantonese province, the English language is used day to day in Hong Kong life, from direction signs being written in both English and Chinese to English words being dropped in regular conversations. It is clear to see that Hong Kong is caught on the fence inbetween these two drastically different cultures, so it comes as no surprise that Hong Kongers are worried about the future of their home. Especially returning back to a government that in the past has been so inheritely against capitalistic ways, which became evident within Hong Kong’s film industry which struggled under the stricter censorship implimented by mainland government.

Present to 2047

Hong Kong in present day has stabilized both economically and culturally after the expected initial blow caused by the handover, although social tensions still remain about future post-handover life, the ‘One Country, Two Systems’ policy is still working remarkably well, recently reaching it’s 20th anniversary. But as the 50-year deadline creeps closer to 2047, concerns about the complete conversion to communism grow. These concerns have been voiced through many different mediums of culture, especially film. Wong Kar-Wai released a film appropriatley titled 2046 (Kar-Wai, 2004), in this film Wong expresses his distrust for the ‘fifty-year system’ in a synthetic Hong Kong setting as well as nostaligically revisiting the golden era of 1960’s Hong Kong, using these two apposing dates of a rose-tinted nostalgic past and a science fiction future, Wong comments on the present, “The trials of the present are projected onto the future. Both times are fiction. 2046 is a spectacular act of self-interrigation. Why can’t it be like it was before?” (Lee, 2005 pg.5.)

Having visited Hong Kong’s problematic history, we can now move on to the coming chapters with sufficient context to be able to fully understand the political and cultural climate of Hong Kong. Subsequently this will make it easier to explore Wong Kar-Wai’s personal vision of Hong Kong and why his locations are such an essential part of his films.

Chapter 2 – The Significance of Location

“Space is the only reliable constant in Wong’s movies, all else is contingent and variable”

- (Xie, 2004, pg.10)

The subject of cinematic space has been studied extensively since the beginning of cinema, how does one choose to show an audience a space? What do they allow their audience to see? Does this location then become a space of fiction or a realistic perception of location caught in time? To answer these questions, we first must understand more about the concept of space in routine life, as described by philosopher Henri Lefebvre in in his book The Production of Space. Lefebevre attempts to unravel exactly how space is constructed in an urban enviroment. Lefebvre states that the concept of urban space is broken down into three separate parts. He describes these concepts not as you would describe an inanimate entity or an object, but as a living breathing organism that not only exerts its own influence, but also interacts with other spaces surrounding it.

The first of the three concepts he describes is spatial practice, the idea of ‘percieved space’ in urban landscapes, the spaces you interact with during your daily routine: “the routes and networks which link up the places set aside for work, ‘private’ life and leasure” (Lefebvre, 1974, pg.38) The next of the three is representations of space, this portion is what he describes as the concieved space. A conceptualized area of planning, building and creating. Almost refering to this space as a non-physical plain that bridges the gap between idea and production. Representations of space can take on physical form through things such as maps, architectural plans and models. Finally, the third and also most important concept for our thesis, representational Space. Lefebvre desribes this space as one that is passively experienced, “space lived through it’s associated images and symbols… space which the imagination seeks to change and appropriate” (1974, pg.39.) It is this space that you see most commonly used in cinematic recreations of urban enviroments, paticularly with Wong Kar-Wai who is constantly appropriating the physical space of Hong Kong within his films. By creating his own fictional city, Wong creates landscapes that not only create intimate scenes based on real world locations through the filter of representational space, but also bring the background of Hong Kong to the foreground, almost as if his locations are another character in the scene emitting its influence over his characters.

These are the themes I wish to discuss further in this chapter. By examining Wong Kar-Wai’s use of location throughout his oeuvre, and the different way he employs these locations, it will allow us to answer the previously mentioned questions, how does Wong choose what to show us in his films and what is he allowing us to see? To achieve this, I will be closely examining a small selection of his films, choosing certain scenes and locations from each that will illustrate his intentions.

Memoirs of Shanghai

Arguably, In the Mood for Love (2000) is Wong’s magnum opus, the melancholy drenched 1960’s period piece about the Shanghainese community in Hong Kong says more about his choice of location than any other Wong Kar-Wai film. The plot of the film is deliberately shallow at a first glance, a man and a woman, Chow Mo-wan and Si Li-zhen, move into the same aparement building, slowly they come to realise that their respective partners are having an affair, in retaliation they reconcile within each other, forming their own romance as they mourn their own lost relationships. From the very first shot, the viewer is crammed into a claustrophobic Hong Kong apartment shared by several different people. Already Wong’s cinematographer Christopher Doyle is restricting the audience’s views. The camera lingers through the tight hallways, never seemingly getting into the midst of the action, never quite letting the audience see what they want to see, as if the viewer has become lulled into a sense of passive spectatorship, a fly on the wall (Fig. 3.)

Figure 3 – Screenshot from In the Mood For Love (Kar-Wai, 2000)

“For what is being stimulated here, beyond the spectator’s own sexual desire, is his or her desire to see, always to see more, an impossible desire linked to the couple’s impossible desire for each other.” (Brunette, 2005)

Boiled down to its simplest form, the majority of the film shows the relationship betweeen two distinctive spaces, respectively owned by Mr. Chow and Mrs. Chan. So much of what the characters do and see is a direct result of the space that surrounds them, which is the exact feeling Wong attempts to create. When discussing the use of space in Wong Kar-Wai films, cinematographer Christopher Doyle states that “I think the films we have been trying to make try to give you a sense of space, a sense of… why this story happens is because it happens here” (Doyle, 2006). One example of this would be the recurring location of the noodle bar, it is here that we see the relationship truly begin form between the characters. Towards the beginning of the film Wong has already introduced this location to the audience several times, Su and Chow are both seen coming back and forth from the noodle bar, often passing each other on the stairwell to their building with polite but reserved acknowledgement of eachother. The pay off comes when both characters happen to be at the noodle bar at the same time, they both try to leave but heavy rainfall forces them back inside, forcing an interaction.

This scene in particular is a perfect example of the background of Hong Kong exerting its influence on the characters in the scene. Wong brings the background of a scene to the foreground, as if the real narrative of the story is hidden within these locations. In Wong Kar-Wai films the location becomes the story, rather than just a setting where the stories take place. So much so that when he begins the process of creating a film, prior to any other part of the process he chooses locations where the story will happen. The rest is inspired by how the location makes him feel, “Wong see’s the space as a protagonist, not just a setting, which initially triggers a film then determines how it is to be made” (Wang, 2015, pg. 7.)

Although In the Mood for Love is set in Hong Kong, rarely in the film do you ever get to see what one would expect from a Hong Kong production. Rather than a bustling city at the height of its industrial transition, you see a different side, the locations are almost always claustrophobic interior shots, and if not, the exterior shots show a darker side of Hong Kong in it’s back alleys and side streets. Wong does this to simulate the city of Shanghai within Hong Kong. He accomplishes this to portray the experience of Shanghainese diasporic communties living in Hong Kong, an experience that he himself went through in 1963 after migrating with his parents. Like so many Chinese migrants in the 1960’s, Wong and his parents left China after the rise of Mao’s Cultural Revolution, a long with an estimated 1.5 million people who fled to Hong Kong from Shanghai. Due to the large numbers of Shanghai locals within the city they formed small closed communities and never really interacted with the capatalist culture of the locals, “Hong Kong was a continuation of 1930’s and 1940’s Shanghai… the Shanghai community sojourned in Hong Kong, but did not participate in the local cantonese culture, partially due to language barriers” (Wang, 2015, pg.8.) Using Lefebvre’s theory of representational space, you can see that Wong warps and appropriates the present Hong Kong to recreate a past Shanghai. Although, this memory of a past Shanghai is not one that Wong Kar-Wai could of experienced, it is a nostalgic view of pre-communist Shanghai that he inherited from his parent’s generation. By mixing these two reminiscences, the nostalgia of a golden period in Shanghai and Wong’s childhood experiences in 1960’s Hong Kong, he creates a fictional city scape frozen in time, therefore Hong Kong in this film is not presented as itself, it is a transnational time-space mirrororing 1930’s Shanghai, as well as 1960’s and present day Hong Kong.

Hong Kong in Globalised Motion

The next set of films I will be examining are Chungking Express (Kar-Wai, 1994) and Fallen Angels (Kar-Wai, 1995). Both of these films are set within 1990’s Hong Kong, and occupy themselves with portraying the younger generation of the city, as apposed to the periodic setting previously discussed. Respectively each of these films work as a companion piece to one another, both of the films show two different stories over the course of their corresponding duration, the stories intertwine and reflect two sides of the same coin, “I always think these two films should be seen together as a double bill… Chungking Express and Fallen Angels together are the bright and dark of Hong Kong. I see the films as inter-reversible” (Kar-Wai, 1998.) The two films work together to create two different versions of Hong Kong, Fallen Angels portrays a seedy nocturnal city that is occupied by criminals acting outside of societal bounds, while Chungking Express shows the viewer a colourful and multicultural cityscape, concerning itself with the globalization of Hong Kong and a fear of losing familiar space and local identity. I will examine these two films individually while also comparing them against eachother in order to understand how Wong Kar-Wai wants us to see these two opposing sides of his fictional Hong Kong.

Many scholars have attempted to decipher Chungking Express, some say the film is merely a love story and shouldn’t be read into any further than that, some say it is a commentary on the 1997 handover, others including myself see Chungking Express as a film about capturing a singular point in time, attempting to preserve local identity in the wake of a rapidly globalizing city. In his book, Hong Kong: Culture and the Politics of Disappearance (1998), Ackbar Abbas states the the biggest threat to Hong Kong cinema is how to keep up the pace with a subject that is always on the verge of disappearing. Through the lens of this theory, this film then becomes a direct response to Ackbar’s concept, if the locality of Hong Kong is truly at risk of disappearing to make way for a globalized culture, then Chungking Express is Wong deliberitaly rebeling against this notion by capturing a glimpse of Hong Kong in constant motion, no past, no future, only an occupation of a reconstructed version of 1990’s Hong Kong space-time.

Throughout Chungking Express there are several different locations that demonstrate Wong’s poetic portrayal of urban spaces, and more importantly, how he chooses to portray Hong Kong as a global city. The film’s English translated title breaks down the two locations that the audience see’s most regularaly, the Chungking Mansions and the Midnight Express. The repeated use of the Chungking Mansions is no accident, the highrise housing block was built in the 1960’s to accommodate for the influx of migrants flooding into Hong Kong at that time, as time marched on to the 1990’s, it was used to accomadate tourists and guest workers from all over the world. The Chungking Mansions in itself is the perfect example of globalization within Hong Kong, “A global ethnography could have been written from within Chungking Mansions alone… Chungking Mansions’ linkages extend throughout the world, just as the world as a whole is in Chungking Mansions” (Matthews, 2011, pg.20.) In Chungking Express, we see a multitude of different characters lingering around the apartment blocks, Asians, Indians, Caucasians and one of the main protagonists, Cop #223 who speaks several different dialects over the course of the film. The multicultural nature of the Chungking Mansions manifests a metephor for the city of Hong Kong itself, an overpopulated bustling cocktail of different cultures.

Midnight Express on the other hand leaves the frantic hyper-active setting of the Chungking Mansions and allows the audience and the character’s time to quietly contemplate (Fig.4.) Everytime we visit this location over the course of the film, the same song is playing on the radio, “The Mama’s and Papa’s – California Dreamin”, in which the lyrics are:

“I’ve been for a walk

On a winter’s day

I’d be safe and warm

If I was in L.A.” (1965)

Figure 4 – Screenshot from Chungking Express (1994)

From this extract we can see that through this song in itself is another example of the globalisation of Hong Kong; an American song repeatedly playing in a take-away in Hong Kong, singing about a longing for Los Angeles. To delve deeper into the lyrics of the song, perhaps the line ‘I’ve been for a walk, on a winter’s day’ represents the cold reality of Hong Kong returning to China in 1997 and losing the localist culture in favour for a modernised global city. Later in the chorus when the song says ‘I’d be safe and warm, If I was in L.A’ could represent a longing to return to Hong Kong before that time, a desperate hint nostalgia through rose-tinted glasses that states everything would be okay if we could just go back.

If Chungking Express shows a vibrant, frantic and global Hong Kong, then Fallen Angels shows the polar opposite. A dystopian, nocturnal version of the same city ruled by the criminal underworld that threatens to overthrow the light version seen in Chungking Express. The globalization of Hong Kong has resulted in an influx of modern technology, making it easier to move through the urban spaces. In most of Wong’s previous films, the characters are usually on foot, slowly walking from space to space, In Fallen Angels we see the characters moving through the city mechanically at speeds never seen before, trains, buses and motorcycles are seen and regularly used during this film to transition from space to space. Technological advancements are seen in other areas also, “The ubiquitious presence of communication technologies, such as televisions, pagers, fax machines and camcorders in Fallen Angels, also indicate that the city is characterized by a rapid flow of information” (Li, 2012, pg.158.) This new found flow of information seen with the rise of communication technologies decreases the gap in between urban spaces even more, creating the setting for this specific reconstructed version of Hong Kong as that of a post-modern cityscape.

Despite the advent of new ways to communicate, physical communication between characters are at an all time low in this film, the first part of the film follows a male assasin and his partner, a young woman. In the very first scene of the film we see the two partners in a room together, a light source from the dimly lit room immuminates the characters, washing out their features as they refuse to make eye contact with one another (Fig. 5.) The audience hear an internal monologue from the assasin, ‘We’ve been business partners for 155 weeks now. We’re sitting next to eachother for the first time today.’ This is the last time you see the two characters interacting in the same room until the very end of the film.In this opening scene the audience can see a clear mood and tone set for the film, a theme of modern isolation washes over the viewer as we transition from space to space through the sea of fallen angels.

Figure 5 – Screenshot from Fallen Angels (1995)

As with all Wong Kar-Wai films, the themes of repeated locations are evident throughout the film, and although there are many examples to choose from within Fallen Angels, I will discuss a location used both in this film and in Chungking Express to tie together the binding theme that connect the two, Mcdonalds. The gleaming beacon of the golden arches, manifesting all things westernized, looms over the city of Hong Kong, Wong uses it as a place where protagonists in both films go to eat. By doing this he offers a western viewer a glimpse of recognition in an otherwise unreconisable setting, but to a Hong Konger, Mcdonald’s represents the invasion of a staple american symbolism. Representing once Hong Kong becoming a global city as well as how western culture has embedded itself into the local culture. Together, Chungking Express and Fallen Angels work together to create one coherent view of Wong Kar-Wai’s reconstructed Hong Kong. Although completely different in their tones the consistent narrative of rapid globalisation and attempting to preserve disapearing local culture in the wake of the 1990’s become evident, the films themselves then arent about the character in the film at all, they become two films about one fictional Hong Kong. Everything else is secondary to location.

Chapter 3 – Hong Kong Stranded in Time

Wong Kar-Wai seems to have a perversion for time, his films centralise around the feelings of loss, attempts to recapture the past and missed opportunities for love, experienced through a looking glass of nostalgia that is attatched and embedded in space. One can see instances of this throughout his oeuvre, for example in Chunking Express where one of the character’s states; “At the high point of our intimacy, we were just 0.01cm from each other. I knew nothing about her.” (Kar-Wai, 1994) an exact measurement of how close he came to love, or within In the Mood for Love (2000) where the old lovers just miss eachother in the hallway of their old apartment after years apart. In this final chapter I will be discussing the relationship between time and space cinematically in the films of Wong Kar-Wai, specifically in 2046 (2004). 2046 is perhaps Wong’s most symbolic film, in essence the film conveys varying commentaries on people’s unique emotional reactions to change over time and recapturing a lost sensation, a feeling that has evaporated into time and memory.

From the outset of 2046, Wong hurls the viewer into his futuristic sci-fi city scape, while this space is not explicity Hong Kong, it represents many things about the climate of the city. Wong refers to this futuristic space as ‘2046’, a place where people go in order to recover lost memories. The film then departs from this ultramodern premise to return to a more familiar setting, picking up from Chow Mo-Wan’s life where the viewer left off from in In the Mood for Love during the 1960’s. The number 2046 instead represents a room number in a hotel in Hong Kong where Chow lives, where he finds himself conducting in several different affairs with women. For the rest of this chapter I will be examining these two locations, both together and seperately in order to explore the argument that time, memory and nostalgia are the primary elements of Wong’s films which not only connect characters and spaces, but also the various version’s of Hong Kong that he evokes.

Layers of Time

The human memory is fickle, rememberance can be influnced or triggered by several different things. Physical entities such as people, places and objects can prompt and render physical spaces in our mind that we recognize but can’t revisit fully, which is what we know as déjà vu, Wong Kar-Wai takes these memories and manifests them in the more concrete medium of cinema.

“We often return to physical sites to relive something- the house where we once lived, the kindergarten we attended, the city of our birth. What happens when these sites no longer exist, or when they are transformed beyond recognition?” (Lee, 2008, Pg. 125.) The films of Wong Kar-Wai evoke an incomplete version of memory, a fragmented déjà vu that is experienced through a prism of nostalgia devoted to a space. This concept has been explored by Ackbar Abbas who coined the term Déjà Disparu, which he defines as “the feeling that what is new and unique about the situation is always already gone, and we are left holding a handful of cliché, or a cluster of memories of what has never been” (Abbas, 1998), this theory explores the idea that Hong Kong cinema has cultivated a cultural space of dissapearance, the dissapearance of identity aswell as physical space, he argues that the main task of Hong Kong cinema is to “find means of outflanking, or simply keeping pace with, a subject always on the point of disappearing–in other words, its tasks is to construct images out of clichés.” (1998, pg. 26).

If this much is true, Wong Kar-Wai responds to this idea by creating a layered ficticious history to service his films, establishing a zone out side the realms of time and space, “He uses cliches to present a memory so real as to be taken for granted, so recognized that it must be true” (Nakama, 2009, pg. 16). We can see this specifically with the number 2046 which pops up regularly in Wong’s films, in the film ‘2046’ the number has several different connotations, in the 1960’s narrative the number represents a hotel room which Cho-Mo Wan tries to rent out, this is a reference to the same room number seen within In the Mood for Love, this specific representation of the number is an attempt to recapture and relive the old memories of the lost love seen in that picture. Wong takes this idea a step further in 2046 by introducing a fleeting romance with a woman who has both the same name and looks extemely similar to his love affair as seen In the Mood for Love.

The second representation of the number 2046 appears in the futuristic landscape as a train, which the audience learn is created from a novel written by Chow Mo-Wan in the 1960’s portion of the film. Here the number becomes a place, or a destination. In a monologue introducing the setting, Tak (a Japanese version of Chow in his novel) explains ‘Everyone who goes to 2046 has the same intention, they want to recapture lost memories’ (2004). In this film time literally becomes a place. Although this backdrop of 2046 is in the future, it is seen through a prism of the past, throught the audiences time here you see fragments of Chow’s own memory leaking into this fictional future. Once Tak boards the train towards 2046 he is completely alone, the only company he has are andriods to help him on his journey, the andriods resemble many of Chow’s failed romances, including Faye Wong from Chunking Express (Fig. 5.) The androids represent Chow’s delayed emotional reaction to his previous failed romantic endevours, the androids inherit human emotional reactions via extremely delayed reactions, as one character explains “If you affect them and they want to cry,

it won’t be until tomorrow when the tears start to flow” (2004).

Figure 5 – Screenshot from 2046 (2004)

This concept of memory plastered onto the canvas of the future applies to Ackbar Abbas’ theory of ‘déjà disaparu’, the disapearence of his past romances are being recycled into the future and Tak is being forced to relive these experiences on his journey to 2046, a space stranded in time, between memory and future, “we repeat the past in order to destroy the present” (Colebrook, 2006, pg.81).

The final and most obvious use of the number 2046 is within a commentary about the future of Hong Kong as it presses forward, toward it’s intergration into mainland China. 2046 references the last year of the 50-year deadline imposed by China after promising no change to Hong Kong’s political and economic systems, ending in 2047. Once again, the future of Hong Kong is experienced through the past, seen though the viewpoint of Chow-Mo Wan’s life in the 1960’s. Chow-Mo Wan’s various sexual experiences portrayed in 2046 are seen by him as no more than ‘time-fillers’, even going as far as to purchase an amount time from one of his partners. The commodification of time gives a significant amount of value to an otherwise unaquirable item, “Wong’s characters rarely love the person with whom they are partnered, to the degree that payment serves as a substitute for love. To that end, love is not the thing of greatest value in relationships, but rather time is.” (Nakama, 2009, pg.7). One can see clearly that by making time a precarious and purchasable entity, Wong is suggesting that Hong Kong is a space living on borrowed time and the futile act of attempting to buy more time becomes useless.

By employing the notion that time is volitile, the spacial intimacies of his locations become more and more important, an extreme close up of a seemingly unimportant object then becomes a window into a fragmented memory, an act of remembemberance. Desperately trying to remember every last detail of what Hong Kong used to be and imprinting it onto the present and future. Wong makes his audience feel the vulnerability of Hong Kong, stranded between what was and what could be. By showing the pain of Chow Mo-Wan trying to recapture memories in the present moment, Wong allows us a glimpse into the pain he feels for the location of Hong Kong.

The intertextuality of Wong’s films becomes quite confusing at times, lines become crossed and audiences find themselves feeling as though they have seen signifiers before, a sense of Déjà vu. Small aspects begin to overlap and the concept of time and space becomes skewed and it becomes difficult to understand what is real and what is memory, “details multiply and replicate themselves; some are conspicous, others are blurred, but all have shifted slightly from their signifying frame works” (Abbas, 1997, pg. 57). This results in an effect of doubling and tripling reccuring items, fragments of memories become overlapped and folded on top of each other over and over again until they become undistinguishable, or some intergrated into the frame work of Wong Kar-Wai’s Hong Kong that they are unrecognisable. When taking the key concept of time into consideration when discussing the cinematic space of Wong, Hong Kong is “a mobile state of rupture where images, space, time, characters and narrative fold in upon eachother, weaving a skein of images that threaten to slip from our gaze” (Tong, 2003, pg.54.)

Conclusion

Over the course of this dissertation, my aim has been to illustrate and examine the ways in which Wong Kar-Wai has represented many different variations of Hong Kong and discuss why his reflections on his city are so essential to his film making style. In terms of space we can conclude using Lefebvre’s theory of representational space that Wong has not only consistently re-appropriated the location of Hong Kong in his own personal vision, but the location itself exerts its own influence on the characters in the screen. Wong Kar-Wai’s use of location manifests the idea that space is the defining factor in relationships, the proximity of you to another, Wong Kar-Wai’s most prominent feature is being able to find spacial intimacies that blossom out of Hong Kong’s influence.

In addition, within my first chapter we begin to see a clear trend of Hong Kong’s troubled past influencing both the present of future portrayals of the city in Wong’s vision. Within the struggle for cultural identity Wong manages captures the spirit of localism while still maintaining a globalist status, much like the way Hong Kong straddles between Eastern and Western influences. As a result of this instability within local Hong Kong, one can see that Wong’s characters are trapped in a state of rememberance, a longing for a time that has already past and wishing things could go back to the way they used to be such as in Chunking Express or In the Mood for Love. This influence from such an unstable space and a constant emphasis on what could have been establishes a clear disconnect with conventional time and memory, which I go on to explore in my third chapter.

Wong Kar-Wai’s relationship with time, memory and loss which I discuss in my third chapter works in unison with the rest of the theories discussed in this dissertation. By identifying and analysing such themes within Wong Kar-Wai’s 2046 using theories such as Ackbar Abbas’s ‘Déjà Disparu’ which discusses the disapearance of the signifing spaces within Hong Kong. Wong tackles this by creating a fragmented version of time in his films, layering details on top of themselves again and again to create a falsified history to accompany the stories he is trying to tell about the intimacies of Hong Kong.

By adding all of these different elements together, you can begin to see a clear image of how Wong Kar-Wai creates his films. By mixing together a cocophony of space, time and memory Wong is able to create a uniquely layered and appropriated version of Hong Kong that he moulds to fit each individual story and narrative. While all the versions of Hong Kong are not dissimilar, they all tell their own individual stories in each reimagining. Which is the point that I believe is the most pivotal part of Wong Kar-Wai films, while the locations change and morph depending on the context of the story, the influence of the space of Hong Kong never changes and is the primary function of Wong’s films. The concept that the image of Hong Kong itself burns in the back of each scene and the space looms over characters, exerting its influence and creating a space for Wong’s meloncholic love stories.

Bibliography

ABBAS, Ackbar 1997. “The Erotics of Disappointment.” Wong Kar Wai. Ed. Jean-Marc Lalanne, David Martinez and Ackbar Abbas. Paris: Dis Voir

BERRY, CHRIS. 2008. Chinese films in focus II. Basingstoke, Hampshire [England]: Palgrave Macmillan.

BRUNETTE, PETER. 2005. Wong Kar-wai. Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

COLEBROOK, CLAIRE. 2006. Deleuze: A Guide for the Perplexed. Continuum International Publishing Group Ltd.

CUI, MENGYANG. 2007. Hong Kong Cinema and the 1997 Return of the Colony to Mainland China: The Tensions and the Consequences.

DOYLE, CHRISTOPHER. BBC CULTURE SHOW. 2006. [TV].

FONOROFF, P. (1988). A brief history of Hong Kong cinema.

GEIGER, JEFFERY. 2007. Facing the Pacific, Polynesia and US Imperial Imagination.

KAR-WAI, WONG. 1998. Interviewed by Han Ong. BOMB MAGAZINE. 1998.

LEE, CHRISTINA. 2008. Violating time. New York: Continuum.

LEE, NATHAN. 2005. Elusive Objects of Desire: 2047.

LEFEBVRE, HENRI. 1974. The Production of Space.

NAKAMA, JULIE. 2009. Time after Time: Exploring Temporality and Identity in Wong Kar‐wai’s Days of Being Wild, In the Mood for Love, and 2046.

TONG CHEUK, PAK. 2008. Hong Kong New Wave Cinema.

WANG, YIMAN. 2015. Serial, Sequelae, and Postcolonial Nostalgia.

XIE, XIAO. 2004. Chris Doyle: 2046 Tortures In the Mood for Love; Wong Kar-Wai Tortures Me.

Filmography

BIN, WANG. 1949. Bridge

CLOUSE, ROBERT. 1973. Enter the Dragon

KAR-WAI, WONG. 1988. As Tears go by

KAR-WAI, WONG. 1994. Chungking Express

KAR-WAI, WONG. 2000. In the Mood for Love

KAR-WAI, WONG. 1995. Fallen Angels

KAR-WAI, WONG. 2004. 2046

PAK-HOI, LAI. 1925. Rouge

SHAO-BO, LIANG. 1909. Stealing a Roast Duck

WANCANG, BU. 1951. Dream of the Red Chamber

XIODAN, TANG. 1934. Platinum Dragon

YUEN, CHOR. 1973. The House of 72 Tenants

[1] Of the 118 films released in 1970, 70% are in Mandarin and only 30% in Cantonese. By 1971, the percentage in Cantonese dropped to 1% and by 1972 to zero. (Sourced from: http://variety.com/2009/film/global/hong-kong-cinema-timeline-1118003687/)

[2] Sourced from – http://fingfx.thomsonreuters.com/gfx/rngs/HONGKONG-POLL/010020KY1EB/index.html

Cite This Work

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing stye below:

Related Services

View allRelated Content

All TagsContent relating to: "Film Studies"

Film Studies is a field of study that consists of analysing and discussing film, as well as exploring the world of film production. Film Studies allows you to develop a greater understanding of film production and how film relates to culture and history.

Related Articles

DMCA / Removal Request

If you are the original writer of this dissertation and no longer wish to have your work published on the UKDiss.com website then please: