Investigation into Infant Feeding Practices in Community Healthcare Organisation

Info: 12057 words (48 pages) Dissertation

Published: 10th Dec 2019

Tagged: ChildcareCommunity HealthFamily

Title

A qualitative & quantitative investigation into infant feeding practices in Community Healthcare Organisation 1: The rates of various methods of infant feeding, BF, F feeding, a combination of both, and the influencers on mothers’ intentions in the prenatal stage and the actual method of feeding in the post-natal stage.

Contents

5.2 The number of participants at the prenatal questionnaire on each site

5.2.1 The age profile of participants across all three sites at post-natal stage

5.2 Age profile of Letterkenny Participants

5.2.1 Age profile of Cavan /Monagahan Participants at post-natal phase

5.4.1 Method of feeding, asked at post-natal questionnaire retrospectively.

5.4.2 Method of feeding at time of questionnaire

7 Qualitative Data Analysis Results

7.4.2 Results Prenatal Questionnaire

7.4.3 Qualitative Quotes from each category

7.4.4 Results from intention to feed question

The results from the pre-natal questionnaire on the question about intention to feed showed that

(73%) intended to breastfeed/use a combination or had not decided.

7.4.5 Results from Constraints and facilitators on intended methods of infant feeding

7.4.6 Qualitative analysis from Telephone interviews

Figure 0‑1

Table of Figures

Figure: 3.2 Global Data Bank , 2016

Figure 3.3 National Perinatal Reporting System (Healthcare Pricing System ,2017)

Figure 3.4 Duration of BF in Ireland.

Figure 3.5 Map of Community Healthcare Organisation 1 (HPO,2015)

1 Chapter 1 Abstract

A qualitative & quantitative investigation into infant feeding practices in Community Healthcare Organisation 1: The rates of various methods of infant feeding, BF, F feeding, a combination of both, and the influencers on mothers’ intentions in the prenatal stage and the actual method of feeding in the post-natal stage.

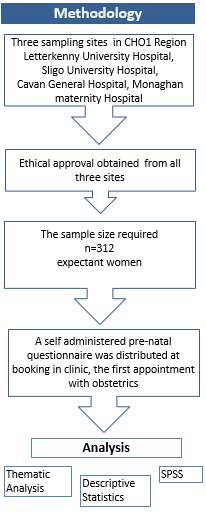

Rationale: The Institute of Public Health in Ireland produced a recent report ‘BF on the island of Ireland ‘as a resource on the state of infant feeding in Ireland and it details the various methods of measuring rates of breastfeeding . Breastfeeding (BF), rates in Ireland remain the lowest in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD,2009). The Community Healthcare Organisation 1 (CHO1), Sligo University Hospital, Letterkenny University Hospital and Cavan and Monaghan general hospitals are in an area with low rates of BF (Perinatal Statistics Report, 2015). This study looks at the intended methods of feeding of expectant women (n=312) using a prenatal questionnaire and the actual method of feeding using a post-natal questionnaire in the CH01 area. The influencers, thoughts opinions and attitudes are captured in both questionnaires and in interviews undertaken at six months.

Methods: Ethical clearance was obtained from the 3 hospitals. Data was collected by a self-administered pre-natal questionnaire with open/closed questions and distributed to consenting women at the first appointment with obstetrics, and after the safe birth of their baby, a post- natal questionnaire was distributed by midwives on the maternity ward to consenting participants. Subsequently interviews took place when the babies were approximately six months, and the qualitative data analysed. Results: Pre-natal Quantitative: n=293 valid, 146 (49.8%) intend to breastfeed, 81 (27.6%) intend to use formula, 35 (11.9%) to use a mixture and 31(10.7%) undecided. Qualitative: four themes influencers emerged Lived Experience, Motivation, Knowledge, and Environment and social influences. Post-natal Quantitative n= 91 valid, 50 (54%) BF, 35 (38%) F feed 3 (3%) use a combination of F and BF and 13 (14%) were undecided. Qualitative data: the sphere of influence, or themes that arose from the 6-month interviews were lived experience, motivation, knowledge, environment and social support

2 Chapter 2 Introduction

2.1 Infant Feeding and Public Health:

Nutrition is a crucial, universally accepted element of children’s lives as stated in the Convention on the Rights of the Child. ‘Children have the right to adequate nutrition and access to safe and nutritious food, and both are essential for fulfilling their right to the highest attainable standard of health’ (WHO, 2013). Nutrition especially infant nutrition and infant feeding has now been recognised globally has a very important component and determinant of health and wellbeing.

In 2015, 193 world leaders agreed on sustainable development goals, a seventeen-point plan that include SDG3 (Sustainable Development Goal 3): ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages and SDG 2(Sustainable Development Goal 2) end hunger, achieve food security and improved nutrition, and promote sustainable agriculture. (UNICEF, 2015). Ensuring optimal nutrition and infant feeding across the globe fits in with both these goals.

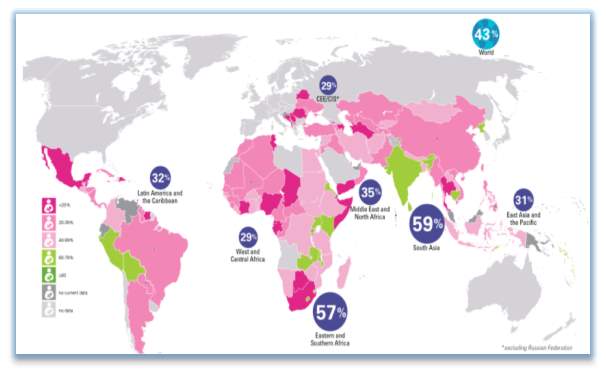

BF is the preventive intervention with the single largest impact on child survival. (Jones et Al, 2003) and yet overall rate of exclusive BF globally for infants under six months of age is 40%. (UNICEF, 2017)

In 2012 the world health assembly resolution 65.6 endorsed a Comprehensive implementation plan on maternal, infant and young child nutrition specifying six global targets for 2025, one of which is to increase the rate of BF in the first 6 months up to at least 50%. (WHO,2017). BF is a natural infant feeding method specifically adapted for optimal growth, development and health.

2.2 Definitions of terms

- Exclusive BF, (BF) no supplemental feeding or drinks including water and or antibiotics. (WHO,2002)

- Predominant infant feeding: mainly fed either breast milk or F(F), (WHO,2002)

- Mixed or combination: feeding a mixture of F and BF since birth.

- F: any F feeding (Breast Milk Substitute) (Formula, F from now on)

Throughout this research it has been important to distinguish a variety of methods of measuring infant feeding

- BF initiation. (WHO,2017)

- Any BF. (WHO,2017)

- BF on discharge. (WHO,2017)

2.3 Infant feeding methods

Mothers decide on how they would like to feed their baby. The options are BF, F or a combination of both BF and F. Many mothers make this decision before they have their baby. Decisions around infant feeding are influenced by social cultural and health factors. For some mothers BF is not possible (this research will explore some of these reasons) and a breast milk substitute (F) or a combination of BF and F is chosen. It is important therefore to ensure that F are of optimum quality and mimic the mother’s milk to ensure it is suited to the individual baby’s needs at the various times during growth. F feeds are powdered milk incorporating additives especially formulated and regulated by the Standard for Infant F and Fs updated in 2007. (WHO, 1987)

2.4 Recommendations

Exclusive BF is recommended by the World Health Organisation (WHO) and United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) within the first hour of life and for up to 6 months of age, with continued BF along with appropriate complementary foods up to two years of age or beyond (WHO, 2016).

The Department of Health currently recommends that infants are exclusively breastfed for the first 6 months of life, after which, nutritionally suitable complementary foods should be introduced to meet the growing nutritional needs of the infant. BF, in conjunction with nutritious solids, should ideally continue until the infant is two years or over (Food Safety Authority of Ireland, 2012).

2.5 The Aims and objectives of this research

Despite the evidence of the importance of BF, BF initiation and duration rates in Ireland remain far below other countries. (OECD, 2009). The CHO 1(Community Healthcare Organization 1 includes Sligo, Leitrim, Monaghan Cavan, Donegal), region of Ireland has been identified as an area with particularly low rates of BF, Letterkenny University Hospital (33.8%) and Sligo University Hospital (33.4%) (The Economic and Social Research Institute, 2012) which are markedly lower than the national average initiation rates of 56% (Department of Children and Youth Affairs, 2014). Research identifying the main influencers on women’s choice of infant feeding and examining the geographical and cultural settings will assist the development of appropriate and effective interventions.

This research aims to identify the rates of the various types of infant feeding in each hospital in the CHO1 area and an analysis of the main influencers on mothers’ choices of infant feeding from the pre-natal questionnaire and the influences on actual practices of infant feeding will be examined in the qualitative data from the post- natal questionnaire collected. The literature review aims to review the literature on rates of BF and the literature available on influencers such as barriers or constraints on mothers’ choice of infant feeding.

3 Chapter 3 Literature review on infant feeding

3.1 Introduction

The purpose of this literature review is to investigate infant feeding intentions, experiences and practices of expectant women in the Community Healthcare area 1. To review the current situation regarding BF (BF) research both quantitatively, and qualitatively and consider this research internationally nationally and locally, ally. Exploring the factors associated with intention to breastfeed can help inform health care decision-makers to plan and evaluate appropriate interventions to improve BF initiation and duration in Ireland and in the CHO1 area.

3.2 Search Strategy

A systematic approach was undertaken to the search strategy which included searching the following databases PubMed, Midars, Cinall, Cochrane, Irish Studies and Grey Literature such as the Medical Times the Irish times etc. Mendeley and Google scholar were utilized to update me on daily basis on new studies as they were published. The words BF AND Ireland/ Infant Feeding AND Ireland/ Survey of Infant Feeding/ Benefits AND Infant Feeding, BF rates and human milk, F, breast milk substitutes were used to locate relevant studies. The words barriers AND breastfeed, BF constraints AND BF facilitators AND BF AND influencers and BF/ infant feeding were also used to locate relevant literature for the literature review. This subject has been widely researched but this research focuses on the area CH01 (Community Healthcare Organisation 1) and will contribute to the infant feeding research both nationally and internationally.

3.3 Benefits of BF

The research from UNICEF and the World Health Organisation is indisputable, BF saves lives. Over 820 000 children’s lives could be saved every year among children under 5 years, if all children 0–23 months were optimally breastfed (UNICEF,2016).

There were roughly 140 million births globally in 2015 only 45% were put to the breast within the first hour this leaves 77 million infants not benefiting from appropriate breast-feeding practices (UNICEF, 2016).

.

3.3.1 Benefit’s for communities

There has been extensive international research outlining the benefits of BF across the global community and the effect increasing BF (BF) will have on the health of nations. Research commissioned by UNICEF U.K established that investing in supports and services to increase and sustain BF makes a significant contribution to reducing health inequalities which is an important indicator to future health of nations and has several benefits both for infants and mothers (Renfrew et al, 2012). Strategies that increase the number of mothers who breastfeed exclusively for about 6 months could be of great economic benefit to communities by improving the health and well-being of both infants and Mothers. By increasing IQ, reducing the incidence of health issues in mothers and children should reduce the economic burden on the healthcare system in the longer term. By lowering the rates of obesity, of breast cancer and in the longer-term diabetes can have a long-term effect on the health of the nation and a better quality of life for communities.

3.3.2 Benefit’s for infants

There is evidence that BF reduces the infants risk of ear infections (Ip, et al, 2007), reduces the risk of diahorrea, (Quigley et al, 2007) respiratory tract infections (Chantry et al, 2006) allergic rhinitis (Duijts, et al 2010) BF also lowers the risk of infant sudden death syndrome mentality (Ip et al, 2007) and increasing IQ reducing the risk of obesity (Metzger et al, 2010).

In 2013 the World Health Organisation produced an update to the two recent systematic reviews (2007) on BF data showing the long-term health effects of BF on children. (Binns et al ,2016) the short-term effects in health from BF. (WHO, 2007). The long-term benefits conclude that there is strong evidence of a causal effect of BF on IQ, and that BF may provide some protection against overweight or obesity in later life (Horta et al. 2006), (Cope and Allison ,2009), (Owen et al. 2005). BF improves IQ, school attendance, and is associated with higher income in adult life (Victoria et al, 2005).

The short-term benefits, include principally the reduction of morbidity and mortality due to infectious diseases in childhood. (WHO,2013). The health benefits of BF are enhanced with a longer duration and intensity of BF (Chantry et al 2006)

BF could prevent many hospital admissions due to diahorea and lower respiratory tract infections (Quigley et al, 2007). Exclusive BF in the first six months of an infant’s life can decrease morbidity from gastro intestinal and allergic diseases it has been recommended that in the first six months of life, every child should be exclusively breastfed and be partially breastfed until the age of two. (Kramer et al ,2012). Infants who are exclusively breastfed for six months experience less morbidity from gastrointestinal infection than those who are partially breastfed for three or four months (Kramer et Al,2012).

3.3.3 Benefit’s for Mothers

BF benefits mothers by reducing risks of breast and ovarian cancer, and BF >12 months was associated with reduced risk of breast and ovarian carcinoma by 26% and 37%, respectively (American Institute of Cancer Research, 2008) .BF was also associated with 32% lower risk of type 2 diabetes (Chowdhury, et al 2015). Steube ,2005 found that women who breastfed for one year or more were less likely to develop Type 2 diabetes than women who did not brestfeed. (Stuebe, 2005). Women who did not breastfed were four times more likely to develop osteoporosis than women who had breastfed (Blaauw 1994). Virden 1988 found that, women had better emotional health at one month postpartum, indicating less anxiety than women who had bottle fed their infants.

3.4 Global Burden of Disease

The global Burdon of disease 2015 study found total deaths by non-communicable diseases increased by 14.1% to 39.8 million (39.2 to 40.5), million in 2015 (GBD,2015). Recent evidence, from high income countries, suggests that incidence of non-communicable diseases may be influenced by exposures occurring during gestation or in the first years of life. (Barouki et al,2012). Non-communicable diseases include several types of cancer, ischemic heart disease, cirrhosis, Alzheimer’s disease and other dementia. Early diets, including the type of milk received, is one of the key exposures that may influence the development of adult diseases (Piwoz & Huffman 2015). World health organisation research from 2012 and a draft in 2017 has shown that of all deaths among persons under the age of 70 commonly referred to as premature deaths, an estimated 52% die from non-communicable diseases (WHO,2017). Over three quarters of premature deaths were caused by cardiovascular disease, cancer, diabetes and chronic respiratory disease (GBD,2015). Babies who are not breastfed have an increased risk of morbidity and mortality from respiratory tract infections, atopic dermatitis, childhood asthma, type II diabetes, obesity and sudden infant death syndrome (Horta et al, 2007).

By increasing BF rates and duration could the incidence and long-term impact of non-communicable diseases globally be reduced thereby reducing health inequalities?

3.5 Rates of BF (BF) analysis

There is confusion and uncertainty over monitoring rates of BF internationally nationally and in Ireland. Measurements include ‘any BF’, ‘BF initiation rates’ and ‘exclusive rates’ and are all used in various studies making it difficult to compare and accurately measure rates internationally and locally. The WHO recommendations for feeding was set out in 2003 this sets limitation for the measurement of rates of infant feeding historically. (WHO,2013)

3.5.1 International and Global rates of Infant feeding

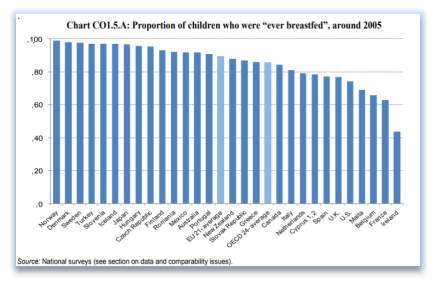

In 1991 the World Health Organisation set up the global data bank on Infant and young child feeding to monitor and review activities. It is based on household surveys and shows comparison between countries and regions. The Global Data bank on infant feeding shows that Ireland had the lowest rate of BF in the EU 2005. (OECD, 2005).

Source: National Survey (see sections on data and compatibility issues

Figure 3.1Rates of BF Proportion of Children who were ‘ever breastfed’around 2005

The most recent Global data bank on infant feeding of 2016 has no figures for Ireland. (OECD, 2016). The 2016 The Global BF Scorecard, which evaluated 194 nations, found that only 40 per cent of children younger than six months are breastfed exclusively and only 23 countries that have achieved exclusive BF rates above 60 per cent have exclusive BF rates above 60 per cent. 24(WHO, 2017). This measurement tool for infant feeding is not consistent across all global nations as it uses local information which has not been standardised.

3.2 Figure Global Data Bank, 2016

Figure 3.2 UNICEF Global data base 2016 Grey areas shows data from before 2004 in Grey. -5 months of age exclusive breastfed, 2015

In 2017 the World Health Organisation developed the global BF scorecard which tracks countries progress for BF policies and programs up to 2030 and attempts to improve the methods by standardizing reporting. This scorecard tracks funding/international code of marketing breast /maternity protection in the work place/baby friendly hospital initiative/BF counselling and training/community support programs/monitoring systems (WHO,2017).

Recent international research collaboration between Australia Irish and Swedish research shows widely differing figures for rates of exclusive BF and any BF (Hauck et al, 2016). Comparisons of ‘ever breastfed rates’ are promising for selected developed countries such as Sweden (98 %)and Australia (96 %), although for others rates are not as favourable (Ireland 46 %)(Hauck et al, 2016).

3.42 Ireland rates of Infant Feeding

Up to now it has been difficult to collect information on BF rates in Ireland. There are several tools used to monitor infant feeding rates in Ireland these include the following.

National BF data is captured from hospitals at point of discharge by maternity wards the methods measured are ‘exclusive BF’ or ‘any BF’ includes combination on discharge and is reported in the Perinatal reporting system (NPRS), which is produced annually by the Health Pricing Office.

National BF prevalence data is collected by the public health nurses at 72 hours and reported by the HSE the measurements in this case ‘exclusive BF’ i.e. only fed breastmilk and ‘partial breastfed’, is some breastmilk and some artificial feed or other milk or other foods. The growing up in Ireland 2015 report uses maternal retrospective self-reporting to measure ‘exclusive BF’ and ‘complimentary feeding’ (combination BF and F).

In 2008 a report commissioned by the HSE a ‘’National Infant Feeding Survey ‘’ analysed the methods of feeding of mothers across all health services areas of Ireland this Irish national data shows 55 % of women reported any BF at discharge and that by six months post birth less than 7 % were exclusively BF. (Begley et al, 2008). This Infant feeding survey of 2008 measured ‘BF initiation’ and ‘infant feeding at 48 hours’ and use the terms ‘exclusive’, ‘combination’ and ‘expressed breastmilk’.

The most recent data for infant feeding rates in Ireland is the perinatal statistics report of 2015 this showed that 48% of babies were exclusively BF in 2015 this represents an increase of 1% in five years since 2011. (HPO,2015)

Figure 3.3 Most recent BF rates in Ireland

Most recent BF rates in Ireland

Figure 3.3 National Perinatal Reporting System (Healthcare Pricing System ,2017)

There was an increase of 3% new-born exclusively BF between 2006 and 2011 from 44% to 47%. There has been better increases in the rates in any BF from 49% in 2006 to 55% in 2011 to 58% of babies in 2015 (HPO,2015).

Irish mothers had the lowest rates of BF when compared to mothers in the EU 15 (excluding Ireland and the UK) who reported the highest rate of BF at 79.3 per cent. (HPO,2015). A recent study from Nolan in Ireland shows a significant difference in Irish and non-Irish mothers rates of BF, non-Irish mothers had a rate of BF at 84.2% and Irish mothers showing 46.1% in 2010 her conclusions mention attitudinal and cultural differences (Nolan et al.2015).

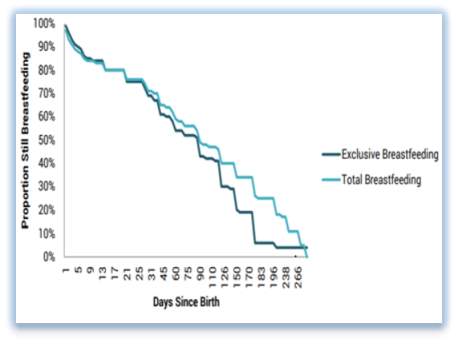

Figure 3.4 Graph showing the decreasing rates of BF over time

Figure :3.4 (McCrory and Layte, 2014) Duration of BF in Ireland.

The 2008 Infant feeding survey showed that half the babies that were ever breastfed were still BF at three months and one in four babies ever breastfed at six months (Begley et al ,2008).Data from the Growing Up in Ireland study showed that among mothers of nine- year old’s who had “ever” breastfed, only 23.2 per cent breastfed for at least 26 weeks (the WHO recommended length) (McCrory and Layte, 2014)

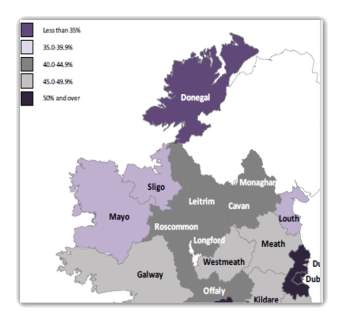

3.5.2 Rates of Infant feeding in the Community Healthcare Organisation 1

The rates of BF in the CHO1 region are markedly lower than the national average initiation rates of 56%(Department of Children and Youth Affairs, 2014). The rates for BF in the CHO1 area BF rates in Donegal were less than 35% Sligo 35-39% Leitrim Monaghan and Cavan 40-44.9% (HPO,2015). These rates are markedly lower than the national average initiation rates of 56%, Kilkenny had the highest rate of BF at 57.6 per cent, and Cork and Waterford reporting rates at 57.5 per cent and 55.8 per cent respectively (HPO,2015).

Map showing the Community Healthcare Organisation 1

Figure 3.5 Map of Community Healthcare Organisation 1 (HPO,2015)

BF was most common among mothers in ‘higher professional’ (65.6 per cent) and ‘skilled manual workers’ (63.5 per cent) socio-economic groups. (HPO,2015) F feeding was most common among ‘unemployed’ mothers with a rate of 63.6 per cent, and mothers whose socio-economic group was recorded as ‘home duties’ 50.7 per cent. (HPO,2017).

3.5.3 Targets and Progress

In 2015 the HSE target was that 56% of babies would receive some breastmilk at the PHN visit at 72 hours and that 38% would receive breastmilk at 3 months.

56% of women breastfed their child to some extent, however, only 6% were exclusively BF at 6 months postpartum as per recommendations (Department of Children and Youth Affairs, 2014). The target is to improve BF duration rates by 2% per year between 2016 and 2021 for both exclusive and non-exclusive BF. (Health Service Executive, 2017). The Health Service Executive has also set a target for 38% of all babies to be breastfed at three months of age, increasing by 2% per year 45(Health Service Executive, 2017).

3.6 Qualitative Research:

In a study Daly et al data was pooled from five Nutrition Monitoring Survey Series which included information on BF from 4,802 Western Australian adults the four themes that evolved from the research for benefits were (it’s natural, good nutrition, good for the baby, and convenience), barriers (BF problems, poor community acceptability, having to go back to work, and inconvenience) and for enablers (BF education, community support, family support and not having to work). (Daly et Al,2014). This data was collected via telephone interviews over a period of 7 years. Being female (males and females were included in this research) rating BF as important, believing that babies should be breastfed for a period and education accounted for most of the statistically significant associations. (Daly et al, 2014).

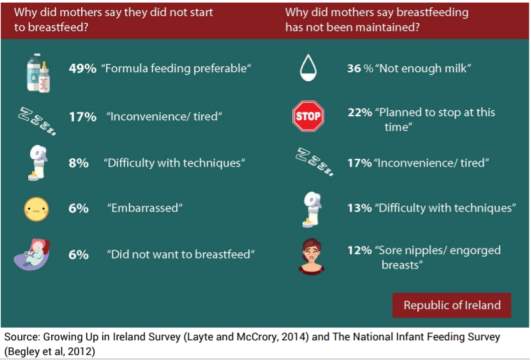

There has been some research on attitudes perceptions and experiences on BF in Ireland. The Growing up in Ireland survey reported that 48.8% preferred F and 17.2% reported inconvenience and fatigue ,8.2% reported BF technique for choosing not to breastfeed. (Growing up in Ireland Survey, Layte and Mc Crory, 2014). This survey also found younger women were also more likely to report social stigma and embarrassment as reasons to us F.

Research by Prof Begley et Al, the national Infant feeding survey was commissioned by the HSE to address the deficit in data that currently applies, on infant feeding in Ireland to determine the rate and duration of BF, the factors influencing women to breastfeed and the reasons given by women for stopping BF (Begley et al, 2008). Mothers were asked about their feeling about duration of their BF experience, if they fed the way they intended and the influencers on what or who influenced them to stop /continue BF. The National Infant Feeding survey of 2008 reported reasons for stopping as busy lifestyle /other children 25%, perceived lack of milk/hungry baby 20.3%, lack of facilities /uncomfortable feeding in public (17.2% retuning to work, lack of support. Wanted partner to share feeding (Begley et al 2008). When asked about continuing BF 73.3% of mothers said their own experience had helped them to continue BF 31.4% said support from partner and 22.3% said health professionals had helped them.

Earlier research conducted in the Mid-West of Ireland revealed that less than 10% of general practitioners had formal training in relation to BF (Finneran & Murphy 2004).

There were similar findings in a recent study from key stakeholders on BF in Donegal the barriers included perception of acceptability of breast feeding within their community (e.g. partner, grandparents, friends, and wider community) ,lack of positive role models ,concern about returning to work, perception that breast feeding is the exception rather than the norm, lack of accurate information about BF and the supports available to women ,concerns about the impact of BF on their lifestyle. sleep, independence, use of alcohol, freedom, (perception that they need to be confined to spaces that are BF), and returning to work (Fullerton ,2016).

BF is an emotive issue and recent research by (Thomson et al, 2015) examines how BF and non-BF mothers experience judgment and condemnation in dealings with health professionals and in community settings, this may lead to feelings of failure, inadequacy and isolation (Thomson et al, 2015).

Strategies and supports are needed to address the personal, cultural, ideological and structural constraints to the various methods of infant feeding. key themes illustrate how shame is experienced and internalised through ‘exposure of women’s bodies and infant feeding methods’, ‘undermining and insufficient support’ and ‘perceptions of inadequate mothering’ as guilt and blame are frequently reported by non-BF mothers, and fear and humiliation are experienced by BF mothers when feeding in a public context (Thomson et al, 2015).

Figure 3.6 Source: Growing up in Ireland Survey (Layte and McCrory,2014) National Infant Feeding Survey (Begley et al,2012)

In the most recent growing up in Ireland 49% of those who did not want to breastfeed said they would prefer to use F, and for those that stopped BF said milk supply was an issue. (HP0,2015)

3.7 Infant F/breast milk substitute: development and regulation.

Infant feeding practice trends have changed historically in various ways across the globe. In the preindustrial age the likelihood of survival was linked to BF or its substitution (wet nurse). After the industrial revolution, women who had always breastfed went to work in factories and the BF tradition declined, encouraging the search for alternative infant nutrition. Initially the mortality rates were high with these first attempts of breast milk substitution, (diluted, flour based powdered milk). This was most likely due to do with poor hygiene in the manufacturing processes. Mothers who choose not to breastfeed have many options from Breast Milk Substitute products (F). Much research has been done to improve these breast milk substitute products and to enhance and change them for the changing needs of the infant’s growth and development.

3.8 Strategies and Policies

The Global strategy for infant and young child feeding is shaped on past and continuing achievements – the Baby-friendly Hospital Initiative (1991), the International Code of Marketing of Breast-milk Substitutes (1981), the Innocenti Declaration on the Protection, Promotion and Support of BF (1990)– and in the context of national policies and programs on nutrition and child health, and consistent with the World Declaration and Plan of Action for Nutrition. (World Health Organization, 2003).

One of the updated Global Strategy for infant and young child feeding main priorities is to develop, implement, monitor and evaluate a comprehensive policy on infant and young child feeding, this includes ensuring that processed complementary foods are marketed for use at an appropriate age, and that they are safe, culturally acceptable, affordable and nutritionally adequate, in accordance with relevant Codex Alimentarius standards (World Health Organization, 2003). The International Code of Marketing of Breast Milk Substitutes aims to stop the aggressive and inappropriate sale of breast milk substitute but ensure that the best available nutritional alternative breast milk substitute is available (WHO,2017).

3.8.1 The situation in Ireland

The 2017 UNICEF Report Card 14 ranked 41 high and middle-income countries in the EU and OECD. According to the study, Ireland scored 31st on nutrition due to our “unusually low BF rate”. The Lancet BF Series 2016 study estimates that the failure to properly support BF costs the Irish State €800 million annually (UNICEF, 2014).

Irish legislation is based on the EU Directive and only includes part of the International Code and resolutions. It restricts the marketing of milks and foods for healthy babies under six months of age, but Irish legislation allows marketing to health workers and it allows marketing of F for infants under one year.

The most recent strategy is BF a healthy Ireland (HSE ,2017) a national action plan guiding the development of policies, practices and research on BF in Ireland. A target of increasing exclusive and any BF duration by 2% per year up to 2021. This research follows on from the review and evaluation of BF in Ireland -A Five-year Strategic Action Plan (Mc Avoy,2014). The department of health produced its first national maternity strategy 2016-2026 recognises the important role of maternity and health services in support for infant feeding and especially BF (HSE,2016). Irelands national policy framework for children and young people ‘Better Outcomes, Brighter Future (Department of Children and Youth Affairs 2014) and the national obesity policy and action plan A Healthy Weight for Ireland 2016 also acknowledges the importance of BF, for health in Ireland.

Many mothers choose a combination of BF and F (combination) there is also the trend for follow on milk for older infants could this influence health in to the future? Despite regulations banning advertising and promotion of breastmilk substitutes and of free samples of hospitals and clinics why are BF rates in some countries not increasing (IBFAN, 2015)? In Ireland Infant feeding F or breastmilk substitutes are marketed to consumers via mass media, tv advertising at prime times, print promotions and indirectly via incentives, free supplies to mothers and through the promotion to health workers and health facilities retailers and policy makers. Internet marketing via company web sites and social media is on the rise with breast feeding /F breast milk substitute companies showing up high on search engines when people are searching BF information.

Mc Fadden et al ,2017 and Sutten et al ,2016 research concludes that there is consistent evidence that support programs, education, having trained personnel, and ongoing scheduled visits with targeted support for BF has potential to improve BF rates. Research by Balagun et al found that BF rates are improved after professional led BF education and peer support interventions increase BF initiation (Balagun et al 2)

3.9 Research on Influencers

The Australian 2005-2007 Infant Feeding Practices Study II, used prenatal questionnaires for 1457 mothers to measure prenatal exclusive BF intention, this study used 6 baby friendly hospital practices, BF within 1 hour of birth, giving only breast milk, rooming in, BF on demand, no pacifiers, and information on BF support (Perrine et al, 2012). The results showed more that 85% intended to exclusive breastfeed for 3 months or more months but only 32.4% of mothers achieved their intended exclusive BF duration (Perrine ,2012) but two thirds of mothers who intended to breastfeed did not meet their intended duration and in hospital F supplementation was associated with almost double the risk of not fully BF days 30-60 and three times risk of giving up BF by 60 days.

Chantry et al 2012 examined the influence of supplementation of F for mothers intending to exclusively breastfeed showed the most prevalent reasons mothers cited for in-hospital F supplementation were: perceived insufficient milk supply (18%), signs of inadequate intake (16%), and poor latch or BF (14%) (Chantry et al, 2012). Moore and Bergman looked at how skin to skin contact influenced duration of BF and found women who had skin to skin contact with their babies were still BF at one to four months after giving birth (Moore et al ,2016). Mothers who had skin to skin contact breast fed their infants longer, too, on average over 60 days longer (Moore et al, 2016).

3.10 Intentions

A large study with over 10,000 participants population-based study in Avon in the UK confirms the strength of the relationship between maternal prenatal intention to breastfeed and both BF initiation and duration. Maternal intention was a stronger predictor than the standard demographic factors combined (Donath et al, 2003).

Blyth et al 2004, Al Bai et al, 2010 and Kronbur et al 2004, examined the effect of intention to breastfeed on exclusive BF outcomes and found positive correlations between the mother’s intended and actual duration of exclusive BF but none of these studies looked at intentions antenatally. Increased self-efficacy was predictive of increased duration of exclusive BF and shows how important the early weeks are critical for the development of self-efficacy and this research (Jager et al, 2012).

BF efficacy is one of the variables related to exclusive BF (Dennis ,2003). Using self-efficacy theory, it is possible to predict whether (a) a mother chooses to breastfeed (b) how much effort will be expanded (c) the thought patterns self-enhancing or self-defeating(d) how she will react to BF difficulties (Dennis ,2003). Increased self-efficacy was predictive of increased duration of exclusive BF and shows how important the early weeks are critical for the development of self-efficacy (Jager et al ,2012).

A woman’s exclusive BF intentions can strongly predict the intensity and duration of her exclusive BF duration (Jagar et al 2012)BF literature has shown that the timing of the infant feeding decision may be predictive of feeding outcomes and that making the decision to exclusively breastfeed before or during pregnancy is associated with a longer duration of exclusive BF than if the decision was made after birth (Scott et al., 2001; O’Brien and Fallon, 2005).

Intention to feed was compared across 1200 women in Syrian 77.2% and Jordan 76.2% intended to breastfeed. In both countries, women with a more positive attitude to BF, women with previous BF experience and women with supportive partners were more likely to intend to breastfeed (Al-Akour et al,2010). BF intention is a significant predictor of infant feeding method Tarrant et al recently reported that BF intention is a significant predictor of BF initiation and any BF at six weeks among Irish women (Tarrant et al .2010). Factors associated with the intention to breastfeed include maternal age, mother’s education level, family household income, number of children, mother’s knowledge about the benefits of BF, previous BF experience, attitude towards BF and the mother’s social support network (Tarrant et al, 2010).

It is interesting to note that evaluation of the baby friendly Hospital initiative by Perez-Escamilla et al 2016 shows there is a dose-response relationship between the number of BFHI steps women are exposed to and the likelihood of improved BF outcomes (early BF initiation, exclusive BF (EBF) at hospital discharge, any BF and EBF duration). Community support (step 10) appears to be essential for sustaining BF impacts of BFHI in the longer term (Perez-Escamilla, et al, 2016).

3.10.1 Positive Support

Women who reported active/positive support from their partners scored higher on the BSES (p < 0.019) than those reporting ambivalent/negative partner support when we controlled for previous BF experience and age of infant. (Manion et al, 2013). A large study with over 10,000 participants population-based study confirms the strength of the relationship between maternal prenatal intention to breastfeed and both BF initiation and duration (Donath et al, 2003). Maternal intention was a stronger predictor than the standard demographic factors combined (Donath et al, 2003).

4 Chapter 4 Method

4.1 Background

This research study was undertaken to find out what factors might influence a mother’s decision on how she planned to feed her baby when it was born and how she fed her baby after her baby was born. This research included all mothers’ opinions regardless of what method of feeding they planned to use to feed their baby. All women’s decisions and views on their chosen infant feeding method were equally important for this study.

The question has two parts:

• Measure the rate of intention to breastfeed (pre-natal questionnaire ,1st stage) and compare to actual rate of feeding post- natal (post-natal questionnaire). Compare hospitals in Community Healthcare Organisation 1.

• Look at why Mothers choose to feed in a certain way in the West of Ireland the CHO1 area and look at facilitators and barriers to infant feeding methods by examining qualitative data collected.

Figure 3.7 Methodology

The information gaps this research should answer are: What were the rates of intentions to breastfeed, F feed, combination or undecided at pre-natal stage across all sites? What were the rates of intention to feed in each hospital? How did participants feed and did this measure up to intention? What were the main correlations found at the post-natal stage. What influences participants to choose methods of infant feeding, how participants feel about methods of feeding? Collect qualitative data on participant’s environment, thoughts feelings, practicalities knowledge and influences can all help to understand participant realm of influence.

4.2 Methodological Approach

There has been considerable thought, debate and knowledge invested over a period of two years and five team meeting to assess and monitor the process the scope and the methodology undertaken in this research. The expertise includes nutrition, health promotion, lactation consultant, public health experts and home economics experts. Over the course of the team meetings the team designed and developed a research strategy a systematic, theoretical analysis of the methods that could be applied to answer the research questions.

It was decided to measure the quantitative data by asking direct questions on intention to feed in the prenatal questionnaire and on how the baby was fed after the baby was born in the post-natal questionnaire. Basic descriptive statistics was used to look at rates of BF in the CHO1 area and the individual hospitals and with further analysis of the quantitative data it was possible to measure mothers’ intentions and compare to mothers’ actual action after the baby was born.

Qualitative data was also collected on these questionnaires by asking open ended questions and analysing data from focus groups and interviews. Qualitative data was analysed using inductive theory allowing themes to emerge demonstrating the key influencers, the main constraints, the barriers, and the facilitators of the various methods of infant feeding. Using mixed methods of analysis, undertaking both qualitative and quantitative data allowed the research team to get a more comprehensive snap shot of Mothers practices and decision-making processes in the CHO1 area.

4.3 Methods used to collect data

The information will be gathered by the following methods

- Pre-Natal feeding Questionnaire (booking in clinic)

- Post- Natal feeding Questionnaire (at discharge)

- Text /call or email at roughly 72 hours (Researcher)

- Text/call or email at 3 months (Researcher)

- Text call or email at 6 months (Researcher)

- Organise Focus Groups (Researcher)

4.4 Ethical considerations

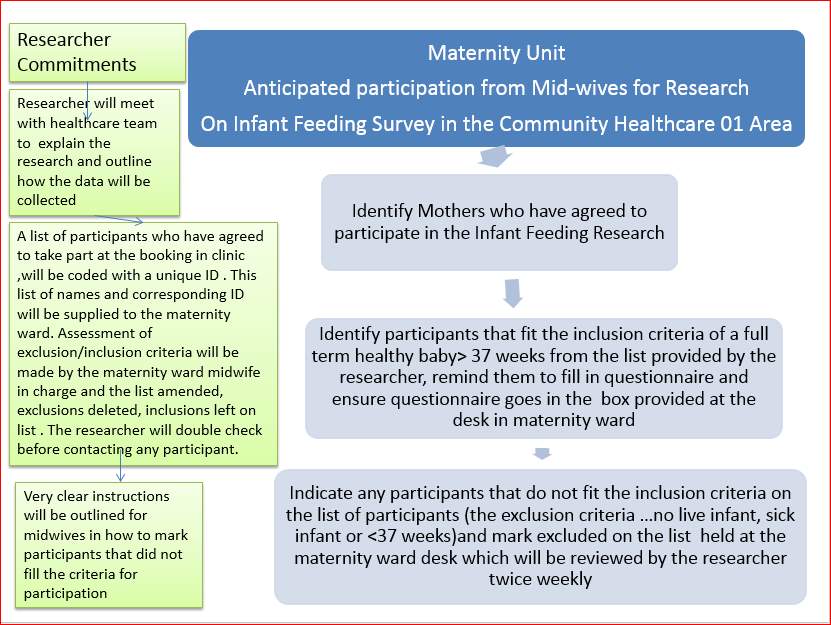

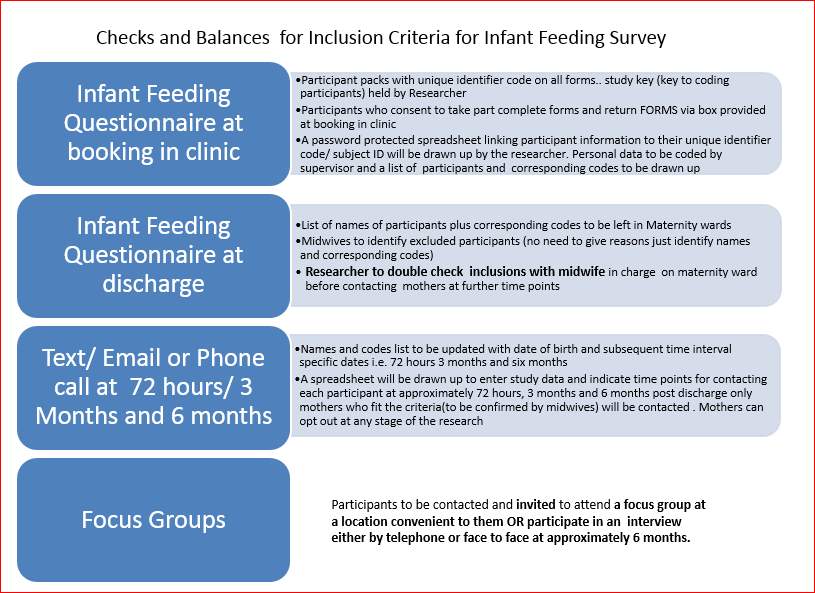

It was important that all women contacted by the researcher fitted the inclusion criteria, a term infant, a live healthy baby and that the mother, had consented to be contacted. More importantly we needed to ensure that women would not be contacted if they fitted the exclusion criteria. To do this a series of checks and balances were put in place, extra clarification was required to ensure no women would be contacted if they had recently had a still birth, a baby under 37 weeks, or that they themselves do not want to take any further part in the study.

4.4.1 Ethics Process

To pursue this research, it was important to comply with all Ethics responsibility. A standard application form for the ethical review of health-related research studies, which are notclinical trials of medicinal products for human use as defined in S.I. 190/2004 was filled in for each hospital.

Figure 4.1 Timeline for Ethics Application submission and acceptance.

| Ethics Research Form | Date completed and submitted | Date Accepted |

| Sligo Ethics Committee | 9/3/2016 | 11/7/2017 |

| Donegal Ethics Committee | 14/4/2016 | 3/6/2017 |

| Cavin/Monaghan committee | 14/4/2016 | 4/7/2017-8/7/2017 |

It is important to note that extra information was required for Cavan Monahan and extra specific forms on participant’s consent forms.

The Ethics application form requires details of the names, qualifications of researchers, the details of times, locations, of research the inclusions, and exclusion criteria, numbers required and description of research and detailed information on how the information is collected. The application was reviewed by our research team. At Post-natal stage the researcher checked with the Public Health Nurses Alert System or contacted the Hospital maternity ward head of department to ensure there had been no deaths of babies to participants on our list. This ensured that a woman whose baby had died or had been ill was not be contacted. This was done on a weekly basis and was documented timed.

However,

4.5 Data Collection

A mixed method using quantitative from questionnaire pre-natal and post-natal and qualitative data from open ended questions and from interviews was used to give an analysis of the situation with infant feeding in the Community Healthcare Organsisation1.

4.5.1 Quantitative data

The quantitative data was measured by asking direct questions on intention to feed in the prenatal questionnaire and on how the baby was fed after the baby was born in the post-natal questionnaire. Basic descriptive statistics were used to look at rates of BF in the CHO1 area and the individual hospitals and with further analysis of the quantitative data it was possible to measure mothers’ intentions and compare to mothers’ actual action after the baby was born.

Figure 4.2 Method of Data collection from Hospitals maternity wards

Figure 0‑1 Data collection methodology

4.6 Participants

Participants for this infant feeding research were expectant woman recruited at the booking in clinic, (their first contact with obstetrics) in each hospital. The participants were offered detailed information about the research. Each participant had the opportunity to read the information and had the opportunity to decide to take part. Ultimately all participants were self-selecting agreeing to answer a short pre-natal questionnaire. Participants will be identified at the booking in clinic which is the first contact the woman has with the hospital since the start of her pregnancy. The midwife in charge will ensure potential participants are offered an opportunity to take part but are ultimately self-selecting. The participant must be over 18 pregnant and willing to participate by signing the consent form.

Figure 4,3 Checks and Balances for Inclusion Criteria

4.6.1 Calculation for number of Participant’s

The number of people required to show significant results was calculated using the following information and the rate of attrition was calculated at each stage in the second table below.

Figure 4.4 Estimated proportions of infants BF and not

BF in the CH01 area and power calculation of sample size

| Area | No of Births (1) | Number BF birth (p=0.56 from literature GUI study) (2) | Proportion of participants not BF (p=0.44) (2) | |

| Sligo | 828(1) | 463.68 | 364.32 | |

| Leitrim/West Cavan | 444(1) | 248.64 | 195.36 | |

| Donegal | 2087(1) | 1168.72 | 918.28 | |

| Cavan | 1028(1) | 575.68 | 452.32 | |

| Monaghan | 867(1) | 485.52 | 381.48 | |

| Total | 5254(1) | 2942.24 | 2311.76 | |

|

Based on previous literature, the proportion of women exclusively BF at time point zero is 0.56 (p). Therefore, the proportion using other methods is 0.44 (1-p). (3) F, 0 |

||||

| t Critical one-tail | 1.659782273 | |||

| P(T<=t) two-tail | 0 | |||

| t Critical two-tail | 1.983264145 | |||

| tStat < – t Critical or tStat > t Critical = reject null | ||||

| Reject Null hypothesis, this means that age is a factor that affects the prenatal intention | ||||

5.1.5 Further Statistical Analysis

Statistics comparing Age, Education Level and Prenatal Intention. In a correlative experiment, the exact relationship between two variables is measured. This shows out how often a change occurs in both variables in terms of a specific percentage.

In this study, the variables are set to with a Confidence Level of 95%. There is a weak positive relationship between the Maternal Age and the Prenatal Intention of the mother, r (101) = 0.34, p < 0.0005. Variables of Age and Prenatal Intention are correlated in a weak uphill positive correlation (0.34)

H 0 = Null Hypothesis means that Age has no effect on the Prenatal Intention of the mothers.

H 1 = Null Hypothesis means that Age influences the Prenatal Intention of the mothers.

Result Explained: Multiple R value is equal to Pearson’s Co-Efficient Correlation (r) value so both must be the same. The alpha (α) is equal to 0.05 this means that this value

is expressed as a proportion. The confidence level is set at 95%, so the alpha is equal to 0.05. The P-Value is less than the Alpha value; 2.38E-10 < 0.05, therefore we can

reject the Null Hypothesis and accept the Alternative Hypothesis.

5.2 Post -Natal Results

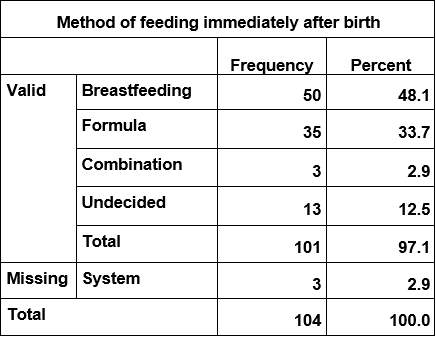

Participants were asked retrospectively how they fed their baby immediately after birth of their baby

5.2.1 Method of feeding, asked at post-natal questionnaire retrospectively.

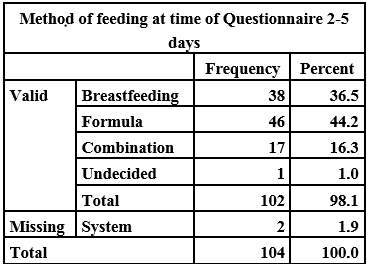

Participants were asked how they fed their baby at the time of the questionnaire which could have been any time from birth to 3- 5 days and a few were posted back and could have been a week after the baby was born.

5.2.2 Method of feeding at time of questionnaire

5.3 Results: Comparison of the prenatal intention to feed at booking in clinic with the actual method of feeding immediately after the baby is born.

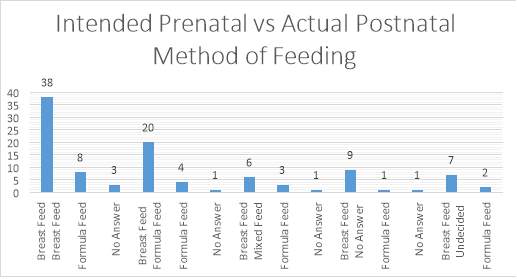

Figure Showing intention to feed with actual method of feeding

5.3.1 Results: The intended method of feeding taken from the pre-natal questionnaire for each of the participants in the second phase of the research was compared to the actual method of feeding immediately after the baby was born. N=104 6 did not answer the question.

Of the 46 participants who intended to breastfeed 38 breastfed almost 83%

Of the women who intended to F feed 83% went on to breastfeed immediately after the baby was born.

Of the 20 participants who either did not answer or were unsure 16 went on to breastfeed

Pre-natal Results on intention to feed at time of booking in clinic

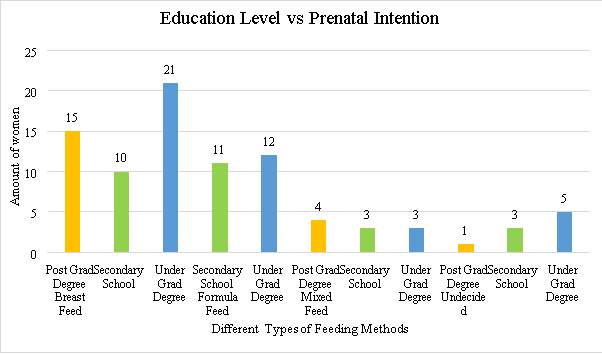

The results from the data supplied by participants on their level of education versus their intention to feed is shown below this is for participants of the second phase only.

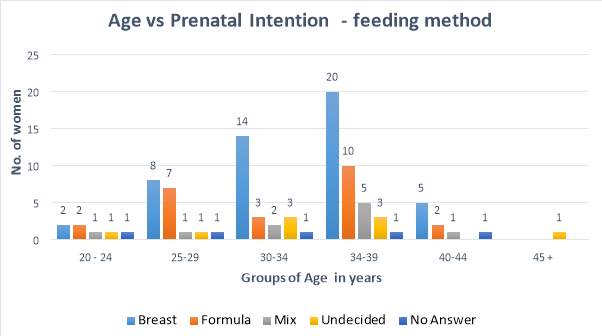

5.4 The data for age of participant and choice of method of infant feeding showed the following results

This graph shows the number of participants in each age group across all sites in the post-natal phase of the study.

t

6 Qualitative Data Analysis Results

6.1 Introduction

This report gives an overview of the qualitative analysis from 312 pre-natal questionnaires and an analysis of the 12 interviews that were conducted with participants as part of the infant feeding research project in the Community Health care organisation 1.

6.2 Aim of Research

The aim of the qualitative interview analysis is to illustrate and complement the results of the statistical analyses. To find out about the individual influencers, experiences thoughts, understandings attitudes and ways they identify the various aspects of infant feeding. Data were analysed from all four of the open questions the data were coded both for the pre-natal questionnaire and a second set of coding for the telephone interviews.

6.3 Methodology

The rationale behind the qualitative component of the study was to provide more in-depth and more contextualised insights into how people perceive infant feeding at the prenatal stage and when after their baby is born at roughly six months stage looking at the outcomes and what has happened to change participants intentions and to explore the influencers around method of feeding.

The textual data was explored inductively using content analysis by examining, re-examining, to generate categories and eventually combining these into themes. This data analysis is looking to find out about a participants’ interpretation of infant feeding at prenatal stage and at 6-10 months. It may also find out how they come to have that point of view, how they relate to others, how they have coped and are coping with the issues around infant feeding. It will also explore participant’s lived experience and history and how they identify and see themselves and others at this time about infant feeding.

6.4 Research Design

The research strategy included qualitative from interviews to complement data by rich and unstandardized data aiming for a richer more accurate picture of the participants. The data from the pre-natal questionnaire and the interviews were treated separately.

6.4.1 Prenatal Questionnaire

Participants were asked four open ended questions if the participant answered the data was transcribed coded, recoded re-examined and analysed inductively to arrive at the following themes.

6.4.2 Results Prenatal Questionnaire

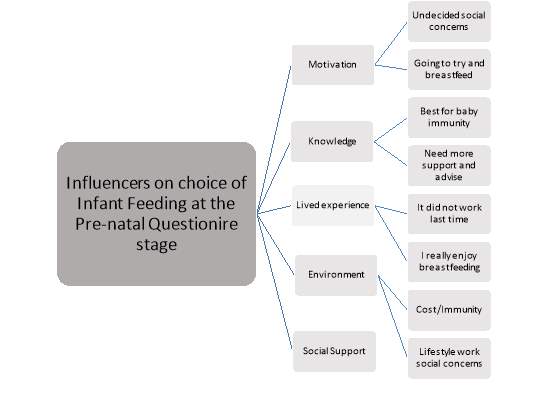

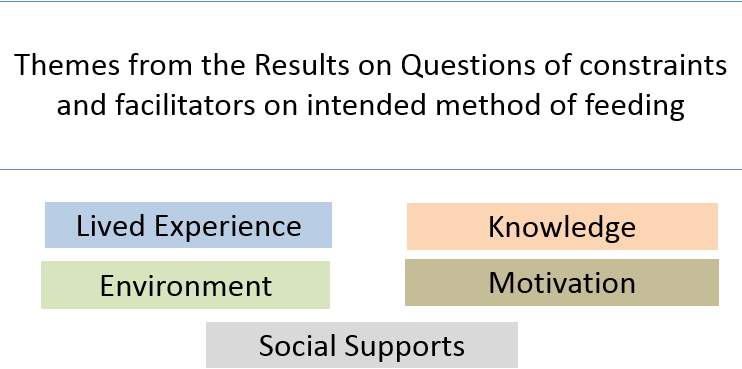

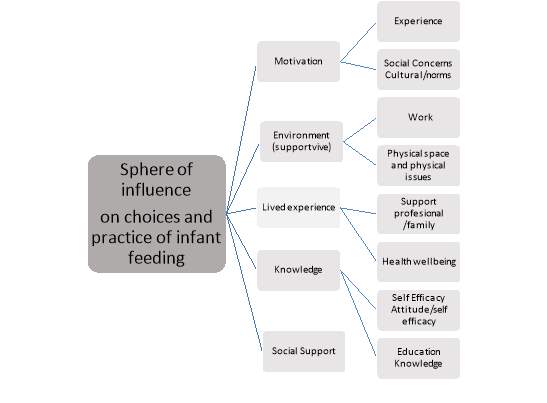

Five themes emerged after rigorous examination of the codes secondary coding leading on to the overall theme of the sphere of influence over the choice on methods of infant feeding.

Visual of the themes that emerged from the open questions on

the prenatal questionnaire.

The qualitative data emerged after the analysis of the four open ended questionnaires from the pre-natal questions.

The Theory is that the five themes of social support, environment, the lived experience, knowledge and motivation are all factors in the phenomena that is infant feeding.

Experience, social support, motivation, knowledge and the environment all play a role in influencing mothers intention to feed their babies in a certain away.

If the experience has been good feeding in a certain way the participants were more likely to feed in that way. If a mother tried BF they usually tried it the second time for longer. Environment and social support also influence decisions the culture or social norm. Having other children and being busy were reasons to breastfeed and to F feed.

6.4.3

Qualitative Quotes from each category

Quotes from participants illustrating some reasons why participants chose to feed their baby in a certain way.

The researcher coded all the answers and reanalysed to find relationships between codes to develop themes through induction.

Figure

6.4.4 Results from intention to feed question

The results from the pre-natal questionnaire on the question about intention to feed showed that

(73%) intended to breastfeed/use a combination or had not decided.

- 77 said it was best for baby

- 42 cited health benefits

- 37 said convenience,

- 29 bonding,

- and 20 because its natural.

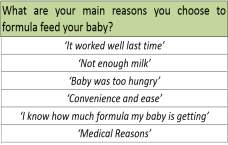

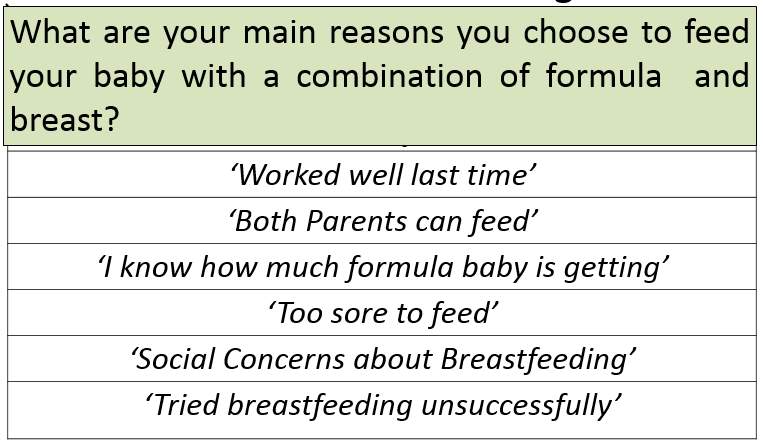

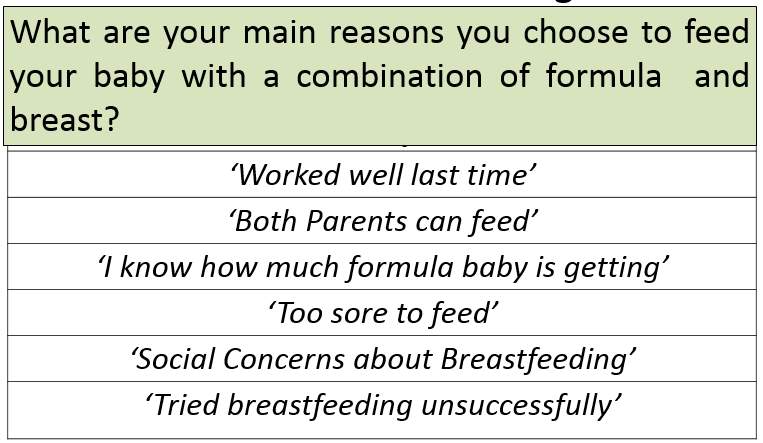

(27%) had decided to F feed.

- 16 found it too difficult or sore last time

- 15 wanted partner involved in feeds

- 8 because it worked well last time

- 9 cited medical or physical reasons and 8 mentioned social concerns.

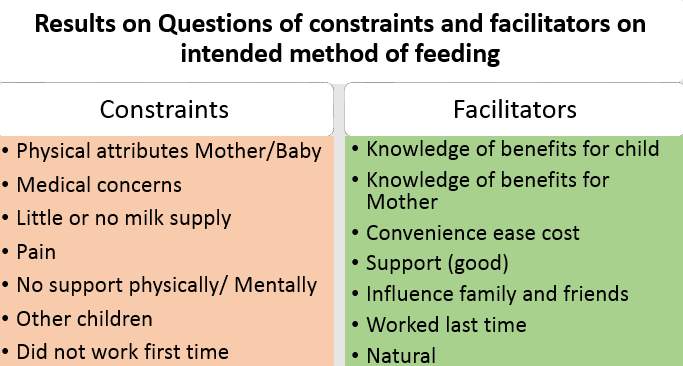

6.4.5 Results from Constraints and facilitators on intended methods of infant feeding

6.4.6  Qualitative analysis from Telephone interviews

Qualitative analysis from Telephone interviews

Introduction

To answer these questions, twelve interviews were set up to analyse what participants reported about their experience of infant feeding at between three and ten months after the safe birth of their baby.

| Three combination feeders three breast feeders and three F feeders were phoned from each site and invited to take part in an interview. |

| Seven were still BF and the others had either moved to F or combination and many had started to introduce solid foods. |

Telephone interviews took place at the beginning of August right through to early September all the data was transcribed y an outside company VOS.ie. The data was analysed using induction technique allowing the themes to emerge from the coded data.

| The following questions were asked. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| BF: many of the women knew about the benefits of BF mentioning best for baby, health benefits of immunity, natural nutrition, babies never sick, uneducated convenience

Initial open coding was performed on the transcripts then links were identified, and further analysis led to eventual themes emerging. The theory |

The phenomena of infant feeding decisions can be further analysed by using the following visual data.

Thematic analysis using induction after coding and recoding and analysing the data

Many factors were found to affect participants decision making around the actual feeding method. If the participant did not have confidence or were not supported to be confident in their action BF did not continue for as long as intended regret was mentioned.

Human issues either biological or psychology often had an influence on method of feeding perceived lack of milk supply, babies unable to latch, physical health issues with babies or mothers all played a part in a mother discontinuing BF or a reason to F feed.

Social and cultural issues was mentioned as playing a part in people’s actual method of feeding, the stigma around BF was mentioned as a reason given why people did not breastfeed.

Confidence in BF was an issue for many participants. Lack of support in hospitals was mentioned and good support from lactation consultants was also mentioned as a support through crises management and problem solving.

Lack of knowledge and education of women was perceived as a major factor on method of feeding with many people saying more information needs to be available for young women. Reasons for not BF were social lives drinking, parties lack of support from partner, and going back to work were all mentioned as reasons to F feed.

Many mothers did breastfeed initially.

Some of the Questions and answers..

- How do you intend to feed the baby that you are currently expecting? Formula/ breastfeed /a combination undecided please explain in the space provided

S30 ‘undecided open to both don’t want to commit to either. However, pressure coming from family and partner’

LK114 ‘undecided it was very uncomfortable and frustrating i never thought the baby was getting enough feed’

C130’ undecided I have just had my 1st session with the midwife today so I have yet to consider feeding options’

C166‘ my first child began to cluster feed on the second night of birth my nipples became cracked and bled. I found it very sore and uncomfortable. I don’t particularly like my nipples being touched i found them extremely sensitive. It took a long time for my milk to through. xxx was a very happy baby. She lost a lot of weight when breast feeding so I will definitely be open to bottle or breast’

C59 (formula) ‘both parents can be involved in feeding process’

C153 ‘I believe breastmilk and colostrum is very important for my baby’s growth and immune system. I think it is what nature intended. It forms a great bond between mother and baby and least importantly it can be convenient and inexpensive’

C159 bf ‘I love breastfeeding because it Is so good for you and the baby. I always breastfed before and I go straight from breastfeeding to the cup. My kids never used a bottle before’

7 Discussion

Each site was different

This research showed similar results to other research undertaken finding the age did influence mothers intended method of feeding and their actual method of feeding, showing older mothers tended to breastfeed more than younger mothers. That mothers who were better educated also were more inclined to breast feed.

Cite This Work

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing stye below:

Related Services

View allRelated Content

All TagsContent relating to: "Family"

Dissertations on many aspects of family matters including those related to parent-child communication and relationships, religion, family stressors and more.

Related Articles

DMCA / Removal Request

If you are the original writer of this dissertation and no longer wish to have your work published on the UKDiss.com website then please: