Dissertation on School Code of Behaviour & Enrolment Numbers

Info: 8151 words (33 pages) Dissertation

Published: 23rd Nov 2021

Tagged: EducationLeadership

Leading an Innovation at the level of the School: Seeking Insights into Sustainable Leadership

Introduction

Given the requirements set out in the Irish context by the Education Act 1998, Education Welfare Act 2000 and within the framework of the NEWB 2008, this paper will aim to critique and provide an insight into leaderships role in supporting the formulation of a new Code of Behaviour policy in response to falling enrolment numbers in the primary setting.

This new Code of Behaviour policy aimed to foster positive practices and habits among its students while keeping to the fore the legal imperative that emphasises for schools the need to ensure that their documents are robust enough to stand up to any challenge on grounds of discrimination under any of the areas covered by the equality legislation.

The paper will begin by providing a background context at an international, national and local level through which one can understand how the formation of such a policy came about. The paper will then document through the case study of Pine Valley N.S. why this process of change needed to occur. The paper will then illustrate lessons learned. With regard to these lessons learned, the paper will attempt to cast a lens upon aspects of sustainable leadership that are evident in the formulation of a Code of Behaviour policy but that are transferable to leading innovations of change to a varying degree in other areas of a schools being.

Sustainable leadership can only occur if every person in the school community has meaningful involvement with and a sense of belonging to the school. At the heart of every school are the students. Their wellbeing across all areas of school life is paramount and is contained within a schools Code of Behaviour policy.

The NEWB (2008) states that a code of behaviour helps the school community to promote the school ethos, relationships, policies, procedures and practices that encourage good behaviour and prevent unacceptable behaviour. The code of behaviour helps teachers, other members of staff, students and parents to work together for a happy, effective and safe school. The code expresses the vision, mission and values of the school and its Patron. It translates the expectations of staff, parents and students into practical arrangements that will help to ensure continuity of instruction to all students (p.2, 2008).

Section 1: Literature review: analytical lens

In the following section a pertinent overview will be given, relating to behaviour plans and policies published in the 2000’s at the macro (international), meso (national) level and micro (local) level, highlighting the most salient literature. This section will draw upon select and relevant literature from Australia and the US, accentuating a parallel with the Irish context with regard to a focus on implementing a behaviour management framework from which schools can work from. It will then narrow the focus by situating educational policy in the meso Irish context (relevant to behaviour), providing a backdrop to the framework and formulation of code of behaviour policies within Irish schools. In the final section, the micro (local) level will be explored, providing an insight on which to ground the ensuing case study.

1.1) Macro-level

At the macro-level, in Australia, Bill Rogers (2005) published Behaviour Management: a whole school approach, focusing on the 4 R’s, rights, rules, responsibilities and routines and an aid to help leaders set up a behaviour management plan and express it in a policy. He highlighted important aspects such as establishing and maintaining internal and external communication systems, fostering a sense of community, taking the lead in setting aims and standards, encouraging collective responsibility and supporting staff (p. 14). Many of his insights are now contained within the recently published Student Behaviour in Public Schools Procedures (2016) documenting a whole school plan to support positive student behaviour that includes: a school code of conduct stating the behaviours that students are required to learn and maintain at the school, the roles and responsibilities of staff in implementing whole school behaviour support, teaching and classroom management strategies that support positive student behaviour including the management of the school environment to promote positive student behaviour, the school’s strategy for communicating to parents on students’ behaviour and the school’s strategy for deciding on the application of disciplinary measures (p. 3).

Also in the US, Carolyn M. Evertson and Carol S. Weinstein (2006) published a Handbook of Classroom Management: Research, Practice, and Contemporary Issues in which a chapter authored by Timothy J. Landrum and James M. Kauffman focused on behavioural approaches to classroom management. In this the authors focus on both the positive and negative reinforcement of behaviours and how these impact students’ behaviour (p. 48-49). Following on from this the National Center for Educational Evaluation published Reducing Behavior Problems in the Elementary School Classroom: A Practice Guide (2008). The purpose of this practice guide is to help school staff promote positive student behaviour and reduce challenging behaviours in U.S. elementary schools.

1.2) Meso-Level

When the Education Act (1998) was passed, it provided what Coolahan (2003) described as a legislative framework for change. In setting out the functions of a school, the Education Act (1998) required schools to: ‘promote the moral, spiritual, social and personal development of students and provide health education for them, in consultation with their parents, having regard to the characteristic spirit of the school’ (Education Act 1998, Section 9d). In Ireland, this acknowledgement that the function of a school is to cater for more than just the academic learning of students was emphasised further with the publication of the Education Welfare Act (2000). Within this educational welfare is alluded to, specifically section 23 clearly outlining for a school what needs to be contained within a code of behaviour policy, that being;

(a) the standards of behaviour that shall be observed by each student attending the school;

(b) the measures that may be taken when a student fails or refuses to observe those standards;

(c) the procedures to be followed before a student may be suspended or expelled from the school concerned;

(d) the grounds for removing a suspension imposed in relation to a student; and

(e) the procedures to be followed relating to notification of a child’s absence from school.

However, what is not elaborated on at this point in time were the specifics, that being, what standards individual schools themselves set for their students and what measures individual schools may take when a student fails to adhere to those standards. What are the procedures to be followed before a student may be suspended, the grounds for suspension and the procedures to be followed relating to a students’ absence from school.

At the meso-level, in early 2005, the then Minister for Education Mary Hannifin commissioned a task force, chaired by Maeve Martin to carry out a comprehensive review on student behaviour in secondary schools. This led in 2006 to the publication of School Matters: The Report of the Task Force on Student Behaviour in Second Level Schools. This publication required an in-depth exploration of the issues relating to student disruption in second level schools, and evidence-based strategies for combating it. Chapter 10 of this publication, highlights and puts forward recommendations for areas for targeting increased positive behavioural outcomes. These include but are not limited to a whole school approach for behaviour management, parental involvement, empowerment of students and teacher education.

At the same time, the INTO (2005) published Towards Positive Behaviour in primary Schools. In this it states ‘A code of behaviour should seek to develop pupils’ self-esteem and to promote positive behaviour’ (p. 12). It also calls for clarity in answering practically the question of how schools can enact the 2000 Education Welfare Act, ‘it is vital that a set of up-to-date guidelines in relation to the compilation and implementation of codes of behaviour be drawn up to assist schools. Among the issues to be addressed are the principles and rationale underpinning the code, the expectations of pupils, teachers and parents, suggestions with regard to school rules, guidance with regard to the use and nature of rewards, a graded set of legally enforceable sanctions and advice on the procedures to be followed in the event of suspensions and /or expulsions (P. 9).

In 2008, the National Educational Welfare Board (NEWB) in response, published guidelines for schools in developing a code of behaviour which sought to address the questions posed by schools following the Education Welfare Act of 2000. Mirroring School Matters (2006) recommendations and coinciding with other international literature published at the time, these NEWB (2008) guidelines for reviewing and auditing the code of behaviour highlighted the need for a whole school approach in devising a code of behaviour policy. It referenced the importance of parents having meaningful ways of contributing to the policy, giving them ownership, providing them with an insight to what teachers need and a collaboration between home and school, allowing a reinforcement of expected behaviour. It referenced students being involved in the process and being more supportive and understanding of a code that they have helped develop. It also referenced the important role of the teacher in bringing to this work their professional expertise in understanding the links between behaviour and learning (p. 16)

All of the above allowed scope for the development of a code of behaviour catering for the individualistic nature of schools and its community of teachers, parents and students. The NEWB also set out basic principles, fundamental to which is the priority on promoting good behaviour. The tone and good behaviour emphasis of the code should be on setting high expectations and affirming good behaviour (p. 22). The code is informed by the principle of fairness. It and equity respects the principles of natural justice, and ensures a consistent approach to behaviour on the part of all school personnel (p.23).

1.3) Micro Level

At the micro level, the aspects of context in relation to situational, external and professional as purported to in Clarke, S., & O’Donoghue, T. (2017, cited in Braun et al., 2011) will be alluded to in order to ground the consequent case study.

Situated context

A chief contributing factor to the difficulty in auditing the code of behaviour policy is the discrepancy between a school system that is largely rooted in past traditions and practices, and dynamic societal changes whose influences are at variance with much that schools cherish and nurture. Schools that continue to espouse traditionally esteemed values and structures can find themselves at odds within a society, which has in some instances, jettisoned older values and structures. This phenomenon translates into a clash of cultures which is often fought out in the frontline of the school system. (Martin, 2006 pg. 24). It is within this context that Pine Valley N.S. is situated.

Due to falling enrolment numbers, the Board of Management (BOM) took the decision to change the schools status from all boys to co-educational in 2010. This did not have the desired effect and in 2013 wrote a letter to all teachers explaining that they have taken the decision to review the code of behaviour under the direction of the new principal due to past and current behavioural issues which were prevalent throughout the school.

External contexts

Leading on from Pine Valley N.S.’s situational context, was the realisation that the schools current code of behaviour policy is no longer fit for purpose. School management under external pressures following a Whole School Evaluation (WSE) in 2012, were required in particular to refer to the NEWB (2008) guidelines around suspensions, taking particular note of any ‘unwanted outcomes from suspension, such as an increased sense of alienation from school that could lead to a cycle of behavioural and academic problems (P. 71) and record keeping of behaviour and any sanction imposed (P. 77).

Professional contexts

The NEWB (2008) guidelines recognise the importance of the leadership of Boards of Management and Principals and place a welcome emphasis on the value of engaging everyone in the school community, and especially the students themselves. At Pine Valley major concern was expressed by teachers at the extent to which policy change was required with reference to the schools code of behaviour. Conway (2010) and Cooper and Jacobs (2011) cited in (Shevlin, M., Winter, E., & Flynn, P., 2013) summarise the professional context in Pine Valley succinctly by describing a strong sense of frustration about managing very challenging behaviour on a day-to-day basis and its negative effects on the learning environment. Children will not learn well when discipline is undermined, teachers are despondent and the atmosphere is unpredictable and threatening (P. 1130).

What appears to be the case is, where there is good leadership, quality teacher input, supportive parental involvement, caring relationships and effective structures in place (Martin, 2006) breaches of discipline are containable and amenable to correction.

It is through this lens that the following case study on Pine Valley NS will be documented and critiqued. What practical examples can be given to show how good leadership impacts overall on a school environment and how quality teacher input into policy can bring about change? How can supportive parental involvement impact positively in a school setting? What impact do caring relationships have in striving towards a common goal? What are the effective structures in place that facilitate good student behaviour? It is through these questions that the following case study be examined.

Section 2: A case study of an innovation: identifying leadership lessons

This section will firstly provide an account of the organisational context in which the new code of behaviour was implemented. Thereafter, described will be the goals, visions and values in how the policy was planned and by whom. Documented next will be the responsibility and decision making process of the policy in determining how the policy was supported, rolled out and the extent to which teachers took ownership. This section will then reflect and evaluate to what degree this policy has been sustained and embedded into practice. The final section will interrogate the lessons learned.

2.1) Organisational Structures

Pine Valley NS is a primary school with an enrolment of 285 students. The school is managed by one principal, who has been leading the school for five years. There is one, newly appointed deputy principal and one AP1 and AP2 post holders, also new to their roles. The former principal was in charge for over twenty years and retired in 2009. This led to a period of much change in the management of the school, as there was then four principals in four years.

In 2009, upon the retirement of the long standing principal, the newly appointed principal early on identified issues with the current code of behaviour policy in the school as documented in the November and December minutes of the staff meetings. The principal deemed the policy not fit for purpose and began researching issues pertinent to the current policy, particularly in relation to suspension protocols and wording the policy in more positive terms.

At the same time, the BOM in 2010, in response to falling enrolment numbers that had been experienced over the past number of years, decided to alter the schools status from an all-boys school to co-educational. The principal attempted to enact change in policy over the course of the school year, however, the BOM, teaching staff and the deputy principal (in position for 30 years) felt that the policy did not require alteration at this time and focus should be given to embedding the new co-educational status of the school. This principal resigned after 18 months in role. The following two appointments to principal were hired from within, the deputy acting up for six months and the other spending one academic year in the role before leaving for another school. There was no advancement made with regard to policy change during this time and enrolment numbers continued to fall. In 2012, a WSE took place, highlighting a systemic failure with regard to the processes around suspensions and behavioural and academic issues. At the end of the 2011/2012 academic year, the BOM wrote to the whole school community detailing a review of the current code of behaviour policy would take place in the new academic year under the guidance of a new principal.

The current principal took on the role in 2013 and is in leadership since.

2.2) Goals, Visions and Values

At the September BOM meeting it was decided that alongside the principal being given the role of overseeing the formulation and establishment of the schools new code of behaviour policy, the BOM would also conduct their own review on the schools vision and mission statement. It was decided that the timeframe around all of this was to be a three year period. Year one was outlined as ‘research’, year two outlined as ‘drafting’ and year three outlined as ‘implementation’.

The principal at the September ISM and staff meetings put as main points on the agenda; professional code of conduct for teachers, school vision and the formulation of a new code of behaviour policy. Teachers’ feedback at the initial meeting is that discipline and clear outlines regarding indiscipline are key to any new vision and policy. Senior class teachers also discuss the need for formal class rules and consistency with these rules across all class levels. Principal minutes that external advice will be sought regarding teachers concerns around discipline approaches.

At the same meeting, junior class teachers highlight the possibility of reward systems as being beneficial. Principal minutes that junior class teachers will take ownership in researching whole school reward systems and reporting back to staff at upcoming meetings.

At the November BOM meeting, it is decided that the establishment of a discipline board to meet the needs of parents of students who had repeated deviations from the code of behaviour may be required. This board would contain a BOM representative, the principal and a teacher representative and was to be brought to staff at their November meetingfor feedback.

At the December staff meeting, staff re-iterate concerns around clear procedures around discipline, documenting misbehaviour and parental expectations. ISM team devise a questionnaire for parents regarding discipline and seek further external supports with regard to discipline and documentation.

Questionnaire sent to the Parents Association in January for them to distribute to the wider parent body. Feedback was sought in relation to what they felt should be communicated in the code of behaviour policy. This feedback was then brought to a joint meeting of the BOM and PA in March. Parents feedback centred around clear communication in the disciplinary steps around misbehaviour so that issues could be tackled at an early stage that pre-empted suspensions being administered. BOM and PA decision taken to explore restorative practices research.

In May, the principal holds open nights over the course of a week where the restorative practices approach is detailed to parents. At the May staff meeting, two practicing teachers from another school in the county provide training on restorative practice to school staff. Staff meeting time is also devoted to allow staff to give feedback on presentation this presentation.

It is clear from the above documentation of the case study that the process was planned overall by the BOM, facilitated and guided by the principal and ISM team, and driven by key insights and initiatives expressed by teachers and parents.

2.3) Responsibility and Decision making

Following teachers concerns around discipline, external support was sought from Max Cannon, a retired teacher in Dublin who is the pioneer of ‘a discipline for learning programme’. This programme (see Appendix 1) is centred on a six step approach to documenting misbehaviour. Steps 1 and 2 are dealt with at a class level and steps 3-6 are accompanied by a standardised letter. Max came to the school with a practicing teacher to train staff in on utilising the programme on a practical level. This six step approach provided a framework through which teachers were guided in devising a uniform set of class rules.

Following on from teacher concerns around discipline documentation, the principal organises a staff meeting with the Special Educational Needs Officer (SENO) where supports are put in place around dealing with students displaying behavioural needs. National Educational Psychological Service (NEPS) hold a meeting with staff and detail the process of the continuum of support and members of DCU behavioural experts’ team are also present at a staff meeting. All of above supports guided teachers in the formation of individual behaviour plans for specific students.

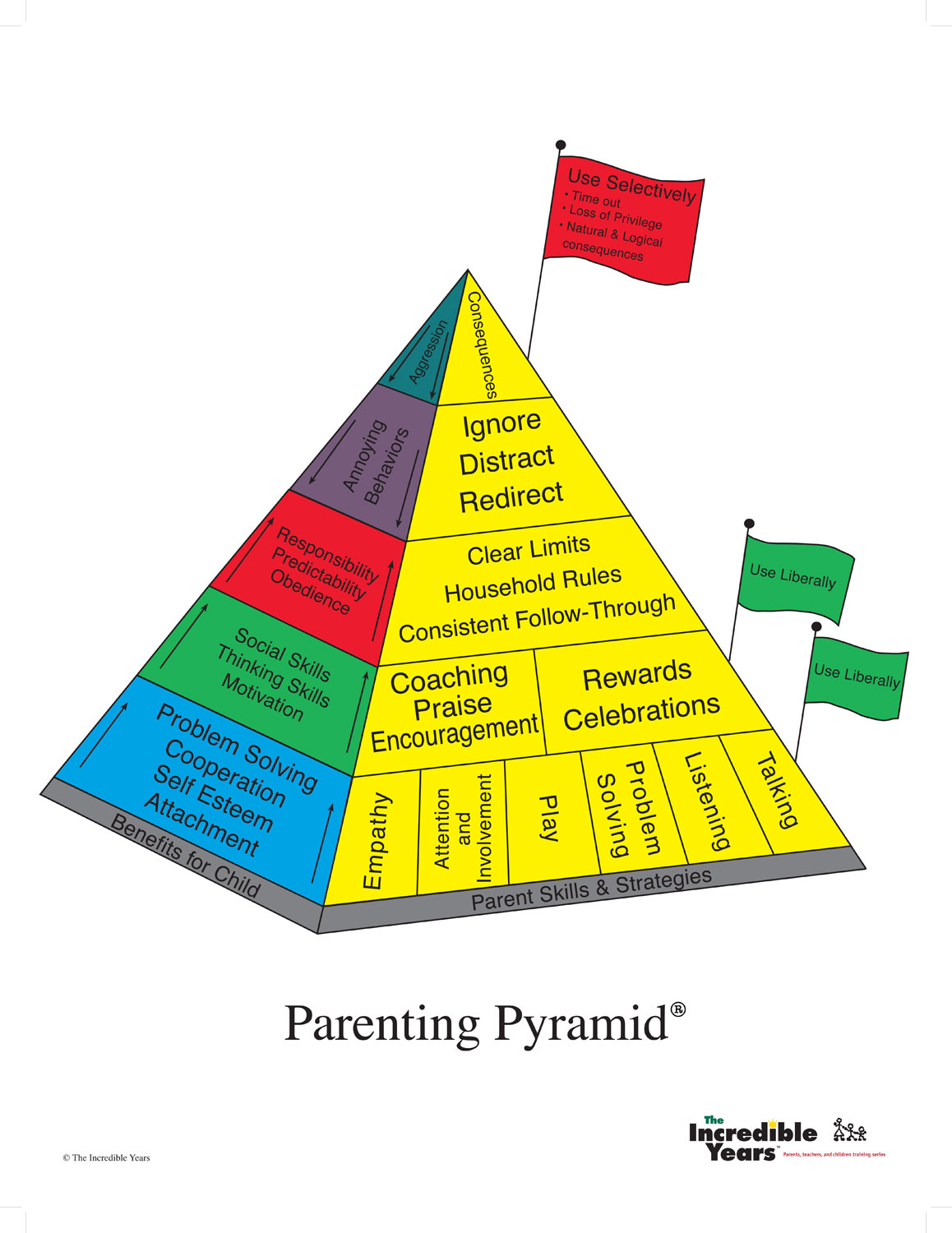

Junior teachers devised an Olympic Games model for a whole school reward system. During the school year students go for bronze, silver and gold awards. Each pupil has a stamp booklet. Stamps can be earned daily. When the booklet is complete you get a medal and move onto the next booklet. The challenge is to complete all booklets in a school year and receive a gold medal. The medals received are recorded on the end of year school reports. They also implemented the incredible years programme (see Appendix 2).

Catherine McMorrow, a practitioner of the restorative practice, along with members of a staff utilising the restorative process facilitate a workshop with staff with regard to best practice. CEART traveller support centre also provided suggestions with how best to implement supports for the travelling community student body and teachers suggested a homework club be established for traveller children. Teachers also suggest the formulation of a student council, as an area for hearing student feedback to school life.

It is clear from the above that the principal facilitated in allowing experts in their individual areas ‘champion’ supports for teachers and students. From this, teachers took ownership in devising whole school reward systems, implementing the incredible years programme, providing clarity around class rules, supports for students in the form of restorative practices, individual behaviour plans and homework clubs and supports around communicating (6 step system) and documenting misbehaviour.

2.4) Reflection and evaluation

It is clear from the above, that steps taken in the ‘research’ and ‘drafting’ stages of the code of behaviour policy has led to sustained and embedded practices being established. These are as follows:

- All teachers have displayed class rules for the principal to see and are visible for children in the same position in all rooms. Clear expectations across the school.

- There are clear steps to follow with regard to sanctions (6 step system). Steps 1-2 are for teachers to handle under class management. Individual letters to be sent home for steps 3-7.

- There is a whole school reward system from juniors to sixth class.

- The incredible years 5 step pyramid is established at both school and encouraged at home.

- There is a written record of misbehaviours.

- Parents are informed every step of the way.

- School termly newsletter with an update from a member of the disciplinary board noting overall and general improvements in behaviour.

- Homework club established and run by teachers for students from the travelling community.

- Individual behaviour plans established for specific students.

- Restorative practices in place for those students to successfully reintegrate into the classroom following suspensions.

- Close and frequent informal and formal conversations between teachers and leaders were present in the school around behaviour. Always on staff, ISM and BOM agendas.

- Establishment of a student council, giving students a voice.

2.5) Attitudes

There was a consensus among teachers at the beginning of the process that auditing the code of behaviour and altering practice would prove difficult due to the historical behavioural problems which were prevalent throughout the school. Many teachers expressed scepticism initially regarding formulating and agreeing a new policy. The principal described colleagues as being opposed to change. The principal also explained that it was not easy to instruct senior teachers to alter their teaching methodologies and approaches around behaviour management.

For this reason, the principal sought out external supports in specific areas to provide best practice workshops for teachers so as not to create a divide between principal and teachers. Over the course of the ‘research’ and ‘drafting’ stages, the principal noted a significant shift in the attitudes, as teachers were given ownership of the process, given necessary supports in best practice, were trusted to implement change and given time to collaborate with each other. This emphasises what Fullan (2015) alludes to when saying that reforms frequently fail to take hold or at best get “adopted” superficially without altering behaviours and beliefs (cited in Stoll & Kools, 2017).

2.6) Lessons Learned

The lessons learned from this case study fall broadly in line with the seven dimensions put forward by Stoll and Kools (2017).

Shared vision centred on students:

This process involved staff, students, parents and other stakeholders. Giving staff the opportunity at staff and ISM meetings and time to communicate their concerns throughout the process allowed the principal to narrow the focus onto key issues. Giving staff ownership in devising whole school reward systems centred on creating positive relations with students was an important development in the process. Facilitating parental involvement through the PA in the form of questionnaires, joint meetings and open nights helped create a school-home link. This shared vision helped shape the organisation, giving a sense of direction to the change and innovation efforts, and served as a motivating force for sustained action in achieving goals (Stoll & Kools, 2017).

Trust (continuous learning opportunities):

Staff were fully engaged in identifying aims and priorities for their professional learning in line with school goals and student needs (Stoll & Kools, 2017). This was evident with a number of teachers collectively engaging in professional development courses specifically around the implementation of the incredible years programme. The trust and time given by the principal in facilitating this professional development was a significant factor in ‘ensuring professional learning is sustainably embedded in daily practice (ibid, p. 8). Trust was also evident from the staff, in being open to new initiatives from the BOM in the form of the disciplinary board, trust in the parents with regard to restorative practice approaches and trust in the principal in overseeing the whole review of the code of behaviour.

Collaboration among staff:

Being listed on all BOM, ISM and staff meeting agendas meant there was a sharing of ideas communicated prior to implementing them into practice and also during and after, allowing a critical reflection into what aspects of the ideas were successful and what needed to be adapted. This was evident in the staff coming to an agreement on a common set of class rules adopted by the whole school. Collaboration lead to deeper learning and improvement as it created greater interdependence, collective commitment, shared responsibility, and a review and critique (Stoll & Kools, 2017).

Responsibility (culture of inquiry, innovation and exploration):

Staff were clear in what the new code of behaviour policy set out to achieve. Problems with the previous policy were well understood, staff were clear about how they can contribute to issues, were allowed select and focus on specific areas and provide innovations which were appropriate (Halbert and Kaser, 2013 cited in Stoll & Kools, 2017). This was evident in the establishment of a homework club for students from the travelling community and the formulation of a student council.

Accountability for embedding systems for collecting and exchanging knowledge and learning:

There needs to be an appreciation that sustaining and embedding all the proposed changes was a difficult process. The principal was steadfast in ensuring what Stoll & Kools (2017) called for, that being ‘collective responsibility and internal accountability among professionals’ (p. 10). It was of fundamental importance that principal ensured accountability, in that staff members were clear in the protocols surrounding the NEWB (2008) guidelines in formulating a code of behaviour policy, particularly in relation to suspensions, given the WSE highlighted this as an area of concern.

External support through whole school involvement:

In the form of experts in specific areas of discipline, documentation, restorative practice were key to providing staff with best practice solutions to problems. There was also transparency at every stage of the process which allowed a development of trust in external supports throughout the school community as everyone was striving to achieve the common goal. Connection with community, partners and networks enriched the schools capacity to serve its students, as it built and maintained the professional capital (Hargreaves and Fullan, 2012, cited in Stoll & Kools, 2017) it needed.

Modelling and growing learning leadership:

It is clear from documenting the process of the formation of a new code of behaviour policy that the principal was able to establish a learning culture in the school. They promoted and facilitated organisational learning through shaping the work and marshalling administrative structures (Stoll & Kools 2017), in order to support professional dialogue, collaboration and knowledge exchange. They helped create a safe and trusting environment in which staff became empowered and the whole school could participated in.

Section 3: Discussion: Learning about the leadership of change

This section will take the lessons identified above in formulating a new code of behaviour policy, and using the same headings, situate them more broadly, indicating aspects of leading change with strong reference to School Self Evaluation (SSE) and Looking At Our Schools (LAOS).

Shared vision centred on students:

From documentation of the process it can be seen that this shared vision came from an instructional leadership base. This however, was not the traditionalist top down, hierarchical form of instructional leadership. This was more of a modern instructional leadership as alluded to by Robinson, Lloyd, & Rowe (2008) when describing principals and their designees (Heck, 1992; Heck, Larsen, & Marcoulides, 1990; Heck, Marcoulides, & Lang, 1991), those in positions of responsibility (Heck, 2000; Heck & Marcoulides, 1996), and shared instructional leadership (Marks & Printy, 2003). This type of shared instructional leadership is distinguished by emphasis on and success in establishing a safe and supportive environment through clear and consistently enforced social expectations and discipline codes (Heck et al., 1991, cited in Robinson, Lloyd, & Rowe 2008). The formulation of a new code of behaviour policy was the beginning of the creation of a base for students through which they could then use as a platform to achieve academically and develop a focus on learning. The establishment of a student council for the first time highlighted a L.A.O.S. target, student voice being a catalyst for change, with an active role in decision-making and policy development (Department of Education and Skills, 2016).

Trust (continuous learning opportunities):

Li, Hallinger, Kennedy, & Walker (2017) argue that principal leadership impacts teacher professional learning by building a climate of trust, communication and collaboration at school. Leadership must realise that trust has been given to schools to identify areas through S.S.E. which need further development (Department of Education and Skills, 2016) and to select standards to target change. Trust was instilled in this case study to teachers from leaders in helping to identify areas around behaviour which could be improved upon and in supporting them in implementing effective change. This is emphasised in L.A.O.S. (Department of Education and Skills, 2016) through the acknowledgement that “all teachers play a leadership role within the school” (p. 7). This, if exercised across multiple areas of the school, can lead to a highly effective learning environment in which teachers feel empowered and trusted in taking risks in enacting change.

Collaboration among staff:

Collaboration is needed to provide a structure for peer-reflection within the school around the analysis and use of data, be it the code of behaviour policy in this case study. Also required and described in L.A.O.S. (Department of Education and Skills, 2016) are “communities of practice between teachers and leaders in different schools, generating discussion and analysis of teaching and learning and leadership within the school community” (p. 10). These collaborative practices are highlighted in S.S.E. (Department of Education and Skills, 2016) as collaborative practices among the teaching staff. The principal and teachers in Pine Valley N.S. collaborated to ensure that there was uniformity across school wide rules, expectations, reward systems and communication of sanctions.

Responsibility (culture of inquiry, innovation and exploration):

Sundli (2009) states that “the strongest element of control in the mentoring of teachers was the discourse of the practising school, where norms (in this case behaviour) were taken for granted, norms about what counts and what does not and the ability to function first and foremost under the conditions of the school’s discourse, its culture and its norms for action” (p. 208). One of the principals most challenging tasks in this case study was to change the norms. They did so by utilising external experts in specific areas who had the relevant and necessary data, knowledge and experience to back up their approaches to behaviour. S.S.E and L.A.O.S. highlights leaders having a responsibility in devising approaches as to how data will be monitored and evaluated, how progress will be determined and how, and by whom will it be reported to, to ensure the quality of student learning is the main driver. The principal in taking responsibility in devising an approach to a new code of behaviour policy, set in motion teacher innovation and exploration with regard to how progress will be determined and how its reported (newsletter and school reports).

Accountability for embedding systems for collecting and exchanging knowledge and learning:

Hall and Kavanagh (2002) allude to this point when describing the traditionalist nature of the previous code of behaviour policy within the school, that which signals parental involvement based on “the possibility that their experience of discussing their children’s progress with teachers hinges around misbehaviour, and teacher comments and judgements that are not grounded in evidence that they, the parents, have access to” (p. 272). Through implementation of the six step approach to behaviour and restorative practice open nights, parents are communicated to every step of the way. This is in line with L.A.O.S. (Department of Education and Skills, 2016) suggests which is establishing and communicating very clearly the procedures for dealing with conflict and follow them as necessary through the implementation of a system promoting professional responsibility and accountability as set out by the NEWB (2008) guidelines.

External support through whole school involvement:

There was a strong emphasis in this case study in harvesting the expertise of outside agencies. NEPS, SENO, CEART, DCU behavioural experts, discipline for learning programme experts and restorative practitioners were all involved in providing a framework and guidance around implementing this new policy. These measures correspond well to what is advised and put forward in literature with L.A.O.S (Department of Education and Skills, 2016) emphasising “engaging purposefully with the national bodies that support the development of effective management and leadership practices” (p. 29). Hargreaves and Braun (2013) propose that “assistance from outside experts and from other schools would develop teacher’s professional capital in utilising other skills to diagnose student learning needs” (p. 24). McAleavy (2015) in his research also alludes to a move towards evidence-based practice, sometimes called the ‘what works’ approach, on the grounds that research can provide teachers with proven methods that are likely ‘to work’. Teachers were more willing in Pine Valley N.S. to get on board with new measures when they were shown to work positively, acting as an effective system in improving professional capacity and providing support and guidance from external consultants (Anrig, 2015).

Modelling and growing learning leadership:

Distributed leadership as in teacher leadership has reported positive impact on school improvement and change due to greater involvement of teachers in decision making (Harris and Muijs, 2005; Murphy, 2005). It has also been noticed that distributed leadership empowers teachers and contributes to school improvement through this empowerment and through the spreading of good practices and initiatives by teachers (Muijs and Harris, 2006 cited in Liljenberg, 2015). L.A.O.S (Department of Education and Skills, 2016) cements this emphasising the empowerment of teachers to take on leadership roles and to lead learning, through the effective use of distributed leadership models. The principal should encourage teamwork in all aspects of school life, creating and motivating staff teams and working groups to lead developments in key areas, thus building leadership capacity. The principal in Pine Valley N.S. through formulation of a new code of behaviour policy has begun growing learning leadership in their school through the distribution of leadership but also the distribution of power.

Conclusion

This paper from the outset posed the questions to what degree good leadership, quality teacher input, supportive parental involvement, caring relationships and effective structures put in place impact on behaviour policy. It is fair to say that these not only have an impact on behaviour policy, but they are fundamental in leading any innovation in schools. Sustainable leadership in schools to be effective, needs to be proactive rather than reactive in style. It is also not individual leaders who make for success, but rather the leaders who establish a critical mass of leadership in developing the collective capacities of whole schools (Fullan, 2010). It is only when the collective capacities of schools are nurtured and developed can real change occur.

References

Anrig, G. (2015). How We Know Collaboration Works. Educational Leadership, 72(5), 30–35.

Clarke, S., & O’Donoghue, T. (2017). Educational Leadership and Context: A Rendering of an Inseparable Relationship. British Journal of Educational Studies, 65(2), 167–182. https://doi.org/10.1080/00071005.2016.1199772

Coolahan, J. 2003. Attracting, Developing and Retaining Effective Teachers: Country Background Report for Ireland, National University of Ireland, Maynooth, April 2003.

Department of Education and Skills (2016). Looking At Our Schools 2016: A Quality

Framework for Primary Schools. Published by The Inspectorate, Department of Education and Skills, Marlborough Street, Dublin 1, D01 RC96.

Department of Education and Skills (2016). School Self Evaluation Guidelines 2016-2020:

Primary. Published by The Inspectorate, Department of Education and Skills, Marlborough Street, Dublin 1, D01 RC96.

Department of Education: Government of Western Australia (2016) Student behaviour in public schools procedures.

Education Act 1998. Act number 51 of 1998. Dublin: Stationery Office.

Education (Miscellaneous Provisions) Act 2007. Dublin: Stationery Office.

Education (Welfare) Act, 2000. Dublin: Stationery Office.

Epstein, M., Atkins, M., Cullinan, D., Kutash, K., and Weaver, R. (2008). Reducing Behavior Problems in the Elementary School Classroom: A Practice Guide (NCEE #2008-012). Washington, DC: National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance, Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education. Retrieved from http:// ies.ed.gov/ncee/wwc/publications/practiceguides

Evertson, C. M., & Weinstein, C. S. (Eds.). (2006). Handbook of classroom management: research, practice, and contemporary issues. Mahwah, N.J: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates

Fullan, M. (2010). The Awesome Power of the Principal. Principal, 10–15.

Hall, K., & Kavanagh, V. (2002). Primary Assessment in the Republic of Ireland: Conflict and Consensus. Educational Management & Administration, 30(3), 261–274. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263211X020303002

Hargreaves, A. & Braun, H. (2013). Data-Driven Improvement and Accountability. Boulder,

CO: National Education Policy Center. Retrieved October 13, 2018, from http://nepc.colorado.edu/publication/data-driven-improvement-accountability/.

Irish National Teachers’ Organisation (2004). Managing Challenging Behaviour. 35 Parnell Square, Dublin 1

Irish National Teachers’ Organisation (2005). Towards Positive Behaviour in Primary Schools. 35 Parnell Square, Dublin 1

Ireland, & National Educational Welfare Board. (2008). Developing a code of behaviour: guidelines for schools. Dublin: National Educational Welfare Board.

Leithwood, K., Seashore Louis, K., Anderson, S. & Wahlstrom, K. (2004) How leadership influences student learning. New York: Wallace Foundation.

Li, L., Hallinger, P., Kennedy, K. J., & Walker, A. (2017). Mediating effects of trust, communication, and collaboration on teacher professional learning in Hong Kong primary schools. International Journal of Leadership in Education, 20(6), 697–716. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603124.2016.1139188

Liljenberg, M. (2015). Distributing leadership to establish developing and learning school organisations in the Swedish context. Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 43(1), 152–170. https://doi.org/10.1177/1741143213513187

Martin, M. (2006) School Matters: The Report of the Task Force on Student Behaviour in Second Level Schools. Department of Education and Science, Ireland.

McAleavy, T., Education Development Trust (United Kingdom), & researchED. (2015). Teaching as a Research-Engaged Profession: Problems and Possibilities. Education Development Trust. Highbridge House, 16-18 Duke Street, Reading Berkshire, England RG1 4RU, United Kingdom.

Robinson, V. M. J., Lloyd, C. A., & Rowe, K. J. (2008). The Impact of Leadership on Student Outcomes: An Analysis of the Differential Effects of Leadership Types. Educational Administration Quarterly, 44(5), 635–674. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013161X08321509

Rogers, B. (2005). Behaviour management: a whole-school approach. London: Paul Chapman.

Shevlin, M., Winter, E., & Flynn, P. (2013). Developing inclusive practice: teacher perceptions of opportunities and constraints in the Republic of Ireland. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 17(10), 1119–1133. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2012.742143

Stoll, L., & Kools, M. (2017). The school as a learning organisation: a review revisiting and extending a timely concept. Journal of Professional Capital and Community, 2(1), 2–17. https://doi.org/10.1108/JPCC-09-2016-0022

Literature review section:

The literature search aimed to locate ‘code of behaviour’, ‘enrolment’ and its ‘impact on school development’ at an international level. This provided limited results as there is not much documented literature on how code of behaviour initiatives impact positively on increasing enrolment numbers in a school context.

Literature review

Appendix 1: Six Steps

If a student is misbehaving, a teacher will draw his/her attention to this and ask him/her to correct his/her conduct. If he/she fails to do so, they go on a step.

There are six steps and these are:

Step 1:

Low level intervention. Teacher says step 1 and keeps teaching (I’m onto you signal). Every student starts each day afresh; the following day the student comes in and begins at zero.

Step 2:

More discreet intervention. Student puts name on sheet and the nature of the step is recorded. Teacher takes a few minutes when student is calm to discuss the behaviour in question.

Step 3:

‘Time Out Table’ and ‘Consequence Sheet’

Student to complete consequence sheet at separate table in the class.

Consequence sheet to be signed by parents (content of work sheet at the discretion of the teacher). Every pupil starts each day afresh.

Step 4:

Moved to ‘Time Out Table’ in another class for half an hour and given work to do. Consequence sheet to be signed by parents. Parent meeting called.

Step 5:

Child sent to principals’ office. Letter to parents informing them of this.

Step 6:

Send for parents. Pupil sent home for the rest of the day. The parents have to visit the school to meet with the discipline board.

Appendix 2: Incredible years pyramid

Cite This Work

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing stye below:

Related Services

View allRelated Content

All TagsContent relating to: "Leadership"

Leadership can be defined as an individual or group of people influencing others to work towards a common goal. A good leader will be motivational and supportive, getting the best out of others when trying to achieve their objectives.

Related Articles

DMCA / Removal Request

If you are the original writer of this dissertation and no longer wish to have your work published on the UKDiss.com website then please: