Interdisciplinary Project-based Learning

Info: 10467 words (42 pages) Dissertation

Published: 16th Dec 2019

Tagged: Learning

CHAPTER II

LITERATURE REVIEW

The literature review is divided into four sections. Each section substantiates the need to study the process of project-based learning between interdisciplinary communities and social learning systems to ensure a sustainable framework for on-going curriculum collaboration.

First a brief history of experiential learning is outlined, including the methods of transition and the impact that each of the contributing theories have had not only on the United States, but also the world. A discussion of project-based learning, specifically the importance of interdisciplinary collaboration, who has formulated a project-based learning curriculum model, what the plan entails, and how that information is to be disseminated to those providing higher education services follows. An examination of why collaboration and communication is important to the implementation of the project-based learning plan is next. Lastly, the theoretical construct of project-based learning, and how it may be used to improve sharing of information associated with interdisciplinary collaboration, is reviewed.

Educators, university administrators, and politicians all influence current post-secondary education policy and practice. Higher education entities like Quest University, have taken a bold, innovative, and project-based approach to invest its student constituents simultaneously in both learning and preparation for future success. Post-secondary educators have reported they believe project-based learning (PBL) improves student engagement (Verma, Dickerson & McKinney, 2011). Effective learning is linked to opportunities to “explore, inquire, solve problems, and think critically” (Asghar, Ellington, Rice, Johnson, & Prime, 2012).

Project-Based Learning (PBL)

An instructional approach known as Project-Based Learning (PBL) was described in its earliest form by Kilpatrick (1921), as the Project Method and has since been elaborated upon by researchers including Blumenfeld, Soloway, Marx, Krajcik, Guzdial, & Palinscar (1991). PBL, as defined by Harada, Kirio and Yamamoto (2008) is an “approach to teaching and learning that brings curriculum in line with the way the world really works” (p. 19). PBL is a student-driven approach to learning systematically guided under a teacher’s facilitation during the process. “Learners pursue knowledge by asking questions that have piqued their natural curiosity. The genesis of a project is an inquiry. Student choice is a key element of this approach” (Bell, 2010, p. 39).

This method of teaching involves a group of students collaboratively working together to formulate a question, research/discover, design, and create projects to implement by reflecting upon their acquired knowledge of real-world issues and solving practical problems (Bell, 2010). Thereby, PBL nurtures collaboration and communication skills, yet honors students’ individual learning styles or preferences. Thus, rather than expecting students to learn all of the same information, individual differences are expected with PBL. Bell, 2010 points out PBL is not a supplementary activity to support learning – it is the basis of the curriculum. Bell (2010) cites the outcome of PBL is “greater understanding of a topic, deeper learning, higher-level reading, and increased motivation to learn” (p.39).

In a PBL model, teachers become less didactic and more constructivist; a common thread is they too become active learners alongside students. This approach allows teachers to diversify their role by modeling and demonstrating without relinquishing control of the learning situation; provide choices within limits; and establishes clear expectations via a well-articulated rubric — all of which, nurture opportunities for student creativity (Lundeberg, Coballes-Vega, Standiford, Langer, & Dibble, 1997). If given room to create, students synthesize and engage freely with concepts established within the scope of the project. Teachers interviewed by Rogers, Cross, Gresalfi, Trauth-Nare, and Buck (2011) using PBL methods “acknowledged a mindset shift in their role from a teacher to a facilitator or coach” (p. 903). Early research findings continue to reflect congruency and alignment, spanning over the past two decades across disciplines in both PK-12 and post-secondary education.

Savery as cited in Walker (2015), indicates project-based learning is similar to problem-based learning in that the learning activities are organized around achieving a shared goal (project). PBL is value-added in that it allows students to flourish by motivating utilization of a multitude of approaches to learning via differentiation. Thus, PBL further promotes use of social strategies (e.g. productive communication, learning respect for others, negotiation, planning, organizational skills, and teamwork), building a strong foundation for students’ future success interacting as active participants in a global economy.

Educators often ask about the difference between project-based learning and problem-based learning. Problem-based learning can be seen as a subtype of project-based learning, in which students work through a series of steps to generate a solution to a problem. Problem-based learning often occurs over a less extended period of time than other forms of project-based learning and is more likely to include simulations rather than a truly real-world context (Duke, 2016).

In part because it often addresses real-world opportunities and problems, project-based learning is typically interdisciplinary as delineated by Duke (2016). First, the skills entailed in project-based learning are consistent with the so called “21st-century skills” – creativity, critical thinking, and collaboration, among other skills – that are in demand for work and citizenship. Second, research is increasingly showing project-based approaches improve students’ knowledge and skills – fostering an enduring curiosity. Third, project-based approaches are more engaging than many traditional kinds of instruction. Teachers organize the PBL process around open-ended driving questions, thereby connecting content to real-life phenomena. As such, PBL enriches content relevancy by facilitating career exploration, technology use, student engagement, and community connections (The Buck Institute for Education, 2017).

Historical Relevance of Experiential Learning to Project-Based Learning

This section discusses the emergence of experiential learning in American public schools, and then describes existing research on PBL in order to present a common definition for this study’s purpose. Considering Dewey’s view that democracy is inherently about involvement in associated life, education for him is focused on increasing participation in conversation and action with others to find shared interests and solve common problems. As Dewey (1916) explains,

Knowledge is a mode of participation, valuable in the degree in which it is effective. As a result, education is not about the idle gathering of knowledge, but about discovery and action through an experimental method of inquiry about the world (p. 393).

The kind of dialogue Dewey finds educative is that which is committed to shared inquiry and discovery and which builds knowledge. This inquiry is aimed at constantly evaluating and reconstructing society in ways that work for all citizens; as such, it is inherently productive and directed toward achieving common conclusions.

With the onset of the Progressive Movement, early education reformer John Dewey (1938) made pragmatism a comprehensive system of thought and his methods concentrated largely on the scientific, experimental tools for clarification of ideas about social issues and morale conduct. Dewey (1938) called for a shift in teaching pedagogy: in a move from traditional to progressive approaches, he stressed the importance of experiential education within our public schools over rote memorization and mere acquisition of knowledge and facts. William Heard Kilpatrick followed in Dewey’s footsteps at Teachers College at Columbia University (Pulliam & Van Paten, 2013). Kilpatrick was the first to describe the pedagogical method now referred to as PBL. As a colleague, he echoed Dewey’s educational theory and sentiments that learning experiences must be meaningful and relevant to students. Kilpatrick believed “education and life, knowing and doing, are continuous … the purpose of education is for students to participate in and make meaning of the content” (Beyer, 1997, p.9). These influential scholars introduced pedagogical methods in the early to mid-20th-century American public schools and paved the path for PBL to foster creativity and divergent thinking within our schools.

Experiential learning provides fertile conditions for supporting both student learning and outcomes. When students are engaged in meaningful learning experiences they personally find relevant; there is an enhanced likelihood of heightened motivation to learn. Providing situations for practice and feedback is also known to motivate students (both individually and in a group or project-based setting). Experiential learning meets these criteria (Ambrose, Bridges, DiPietro, Lovett & Norman, 2010).

Through experiential learning, students are confronted with unfamiliar situations and tasks in a real-world context. To successfully complete these tasks, students need to figure out what it is they know, what it is they don’t know, and how best to learn it. This requires students to leverage their capacity to: consider their prior learning and add depth through reflective practices; transfer their previous knowledge to new contexts; master new concepts, principles, and skills; and possess the ability to articulate how they developed this skill-set (Linn, Howard, & Miller, 2004). Collectively, this process creates students who thrive in a self-directed mindset, to ultimately become life-long learners.

Professional schools move beyond this vantage point, as the purpose of their programs is to help students understand what to do in concrete practice and foster regularity in application. Proponents of experiential learning continue to cite the importance of ‘learning in context’. Experiential learning acknowledges people think and learn differently in different social contexts. Thereby given unpredictable situations, students draw on their capacity to formulate and solve problems in different ways by improvising upon best practices in order to create new learning (Linn, et al., 2004).

Factors Impacting Alignment of Project-Based Learning

Amidst the increased focus on standardization and assessment of specific core subject knowledge within our public schools, forces affecting education in the twenty-first century include population diversity, globalization, technology, and religious and spiritual variables. In addition, social changes, political forces, economic pressures, plus beliefs and values continue to develop in our country (Pulliam & Van Patten, 2013). All of which, are bound to influence educational policy and practice (Barbour, Barbour, & Scully, 2008). Although on-going research supports why schools and educators should be using experiential and student-driven approaches to teaching, current education policies do not make this an easily attainable reality for educators. The stakes are ever heightened, and as educators, we ethically have an obligation to be accountable to appropriately prepare students for a future living in a competitive environment that is in constant flux.

Other world-renowned education experts share the problem that the current system of education was designed, conceived, and structured for a different age. In a speech given by Sir Ken Robinson in 2008 he shares “we have a system of education that is modeled on the interests of industrialism and in the image of it”. Vivid examples he provided in the RSAnimate (2010) Changing Education Paradigms video include those of schools being organized along the concept of factory lines – ringing bells, separate facilities, specialized into separate subjects; educating children by batches by putting them through the system by age group. Robinson (2010) summarizes, “If you’re interested in a model of learning, you don’t start from this production line mentality”. His philosophy is we should change the paradigm in education from conformity and standardized testing and curricula to one going in the opposite direction of ‘divergent thinking’.

This researcher would conceptually agree great learning happens in groups through collaboration, as it is the ‘stuff of growth’. To expand upon Robinson’s viewpoint – human capacity allows for multiple answers, not just one; there are endless possible answers to one question and several different ways to interpret a question. If we tend to minimize the essential capacity for creativity in those we are responsible for teaching/leading, we will lose out on original ideas that have value.

Given this information, PBL is a teaching pedagogy providing promise because it is collaborative and student-driven, based on real-world problems, and it fosters divergent and creative thinking. Markham (2011) echoes these ideas when writing of the need for education to reflect the changes of our world. Markham (2011) suggests lecture and direct-instructional methods will soon be outdated as we find more efficient and effective ways of providing our students with meaningful educational experiences.

As educators, we must utilize models to educate students to better fit the age we live in today – an increasingly complex, global world. In 2012, Joel Rose wrote an article for The Atlantic as a call to action in response to the technological era we now live in. This educational entrepreneur from New York City declared,

It’s time to unhinge ourselves from many of the assumptions that undergird how we deliver instruction and begin to design new models that are better able to leverage talent, time, and technology to best meet the unique needs of each student (2012, p. 4).

It is by means of effectively incorporating PBL strategies in the classroom, students, educators and school districts can all benefit.

Liu, Wivagg, Geurtz, Lee, and Chang (2012) suggest school leadership must support PBL implementation through development of a shared vision, coordination of professional development activities, critical evaluation of grading and assessment, and promotion of a “learning-by-doing” approach to pedagogy. These authors concluded to effectively implement and strategize successful outcomes — teachers, administrators, instructional materials, and technology must all be appropriately aligned.

Concerns with Project-Based Learning

Nonetheless, some teachers may find PBL challenging to implement as they struggle to transform their entrenched beliefs. Harris (2015) found teachers perceived the following issues to be most challenging when implementing project-based learning initiatives: time, meeting state accountability requirements, addressing the standards, implementing the project within the school’s schedule and designing the project-based experience itself. His findings also suggest professional development may help alleviate some of the perceived challenges teachers face when implementing project-based learning.

Equally, Robinson’s ethnographic study (2012) posits, despite the pressures of adopting policy, through strong collegial relationships and collaboration, teachers can find ways to reshape requirements in order to meet them in their own way (p. 244). Thus, the literature suggests even though teachers may perceive outside challenges exist when implementing project-based learning, opportunities are available and accessible to successfully adapt practice in order to meet both state requirements and implement project-based learning. Likewise, Riveros, Newton & Burgess (2012), write of the benefits of professional learning communities [when given the right cultural climate and communication – a situated account] can improve teacher agency and increase student learning (p. 205).

Foundational Blocks of Project-Based Interdisciplinary Collaboration

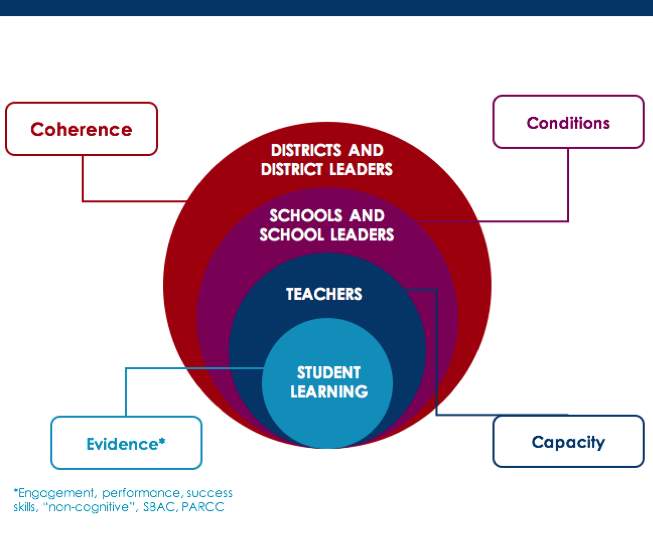

The Chief Program Officer for the Buck Institute for Education (BIE), Brandon L. Wiley, delves further into why it takes a system for high quality PBL to be successful. Wiley (2017) stresses a system as provided by BIE includes the foundational blocks of coherence, culture, capacity building, and continuous improvement:

Increasingly, it’s become clear that beyond teacher capacity and preparation, leadership—both at the school and district level—plays a pivotal role in the successful implementation and long-term sustainability of PBL. Leaders need to understand how PBL can be a transformative approach to teaching and learning, while helping to create the conditions and structures necessary to facilitate and sustain the effort. In other words, when leaders understand the power of PBL, they will set a vision that supports this pedagogy and work hard to create time for teachers to collaborate, reflect, collaboratively assess student work, and iterate over time. In systems where these key conditions are not strategically designed and implemented, successful implementation is less likely (Wiley, 2017).

The Buck Institute of Education (BIE) recommends practicing with an “ecosystem” model around schools to ensure support of the practices and structures necessary for high quality PBL. This model is diagramed below in Figure 1. to illustrate the pivotal role required not only for successful implementation, but long-term sustainability of PBL (Wiley, 2017):

Figure 1. The Buck Institute of Education (BIE) “Ecosystem” Model

Best results occur when everyone in a school-community is on board with making a significant change in the teaching methods at a school, as PBL represents a shift in thinking about what and how students should learn (The Buck Institute of Education, 2017).

The Role of Communication & Curriculum in Successful PBL Implementation

Why study project-based learning and its effect on higher education organizations? Significant research as well as an extensive review of traditional experiential theory literature suggests interdisciplinary collaboration and curriculum are related, in addition to communication. For an organization to maximize its potential, it is necessary for those within the organization to fully understand what is expected of them and why what they do is relevant to the success of the organization (Hargie & Tourish, 2004; Neher, 1997; Pace & Faules, 1989). Pace and Faules (1989) suggest:

- There are universal elements that make an organization ideal.

- These universal elements can be discovered and used to change an organization.

- These elements and the way they are used “cause” or at least produce outcomes.

- Organizations that function well have the right mix and use of the elements.

- These elements are related to desired organizational outcomes.

- Communication is one of the elements of organizations. (p. 2)

The effect of communication on the organizational climate, and ultimately, its effect on

the overall success of an organization, is often given less attention than other functions such as finance. This is counter-intuitive, as “the success of any organization if most dependent on the human element; the competency, motivation, commitment, level of skill, and experience of each individual is what determines the success of the whole” (Schneider & Kalbfleisch, 2007, p. 21). With a shift to a more collaborative environment has come an increasing need for interdisciplinary initiatives in higher education. Mitchell (2015), also reminds us great collaboration starts from the basic rules of elementary school; our organizations simply need to understand how to play nicely in the sandbox with others.

Macfadyen and Dawson (2012) speak to an intriguing recommendation that “research

must also delve into the socio-technical sphere [emphasis added] to ensure that learning

analytics data are presented to those involved in strategic institutional planning in ways that have

the power to motivate organization adoption and cultural change” (p. 161). Fritz and Whitmer,

(2017) go further to explain a methodology for realizing the full potential of learning analytics to

become transformative by:

Showing people how they can do better in a positive way, without embarrassing them, might encourage them to take those next steps forward. With the right stories touching people’s hearts about the value of learning analytics and solid data supporting that message, both heart and head can agree to face the possible discomfort of change in pursuit of excellence (Fritz & Whitmer, 2017, ¶ 32).

In this way, faculty members can continue stimulating campus conversations about new possibilities in teaching and new ways to improve learning.

The Move to Massive Open Online Course (MOOC) Models

In addition, the higher education environment within which project-based learning takes place has become increasingly complex in anticipation of financial downturns and the move to Massive Open Online Course (MOOC) models. A massive open online course (MOOC) is a model for delivering learning content online to any person who wants to take a course, with no limit on attendance. For example, Duke faculty members have invested heavily in the university’s exploration of MOOCs, with 30 instructors from 28 departments developing 31 MOOCs on Coursera (Manturuk & Ruiz-Esparza, 2015). The on-campus impacts have gone far beyond the exploration of flipped classes. Faculty members are:

- leveraging MOOC resources for much-needed supplemental learning and review opportunities for on-campus students;

- improving materials and activities in their classes (which in turn provided students greater flexibility in learning content);

- crafting better assessments to measure student learning; and

- experimenting with new pedagogies to increase engagement and learning (¶ 24).

Manturuk and Ruiz-Esparza (2015), highlight the impact Duke University’s MOOCs initiative has had “in reaching global audiences, increasing access to educational resources, and spurring on the development of new educational technologies and business models” (¶ 8).

Daphne Koller’s TEDTalk “What We’re Learning from On-line Education” (June 2012) talks about key issues of availability, affordability, and opportunity that on-line education can now deliver. What makes the platform she co-founded with Andrew Ng, Coursera, different is that it delivers free education courses ‘at scale’ globally. Components in design allow for personalized learning and retrieval of material to practice, which has been proven to improve learning. In this platform, every single student has to engage with the material. Teachers are able to provide students with feedback and are utilizing technology to auto-grade. This ability to interact is essential with distance learning.

At the time this platform was released, technology wasn’t able to auto-grade critical thinking type assignments as required in the humanities. The solution to this was to have peer grading available for open-ended work. When students self-grade assignments critically (when incentivized properly) these results are even better correlated with teacher grades, according to Koller (2012). Thereby, grading in scale is a useful learning strategy, as students actually learn from the experience. This platform was the largest peer grading pipeline ever devised and a global community formed with shared intellectual endeavors. Student collaboration with students helping each other occurred – they self-assembled into small study groups without intervention.

Koller (2012) describes the tremendous opportunities that exist by means of using this type of framework to deliver education:

- Capability exists to give an unprecedented look into understanding human learning;

- Data collected is unique – every click, every homework submission, every forum post can be mined;

- One can turn from hypothesis mode into a data-driven mode;

- This data can be utilized to answer fundamental questions and to separate what are good learning strategies that are effective versus ones that are not;

- Within the context of particular courses; they can ask what are the misconceptions that are more common, and how do we help students fix them?

- This platform provides a new window into human learning;

- Personalization is one of the biggest opportunities this type of platform provides the potential to solve. This personalized trajectory in curriculum to provide personalized feedback allows teachers to ignite minds with ‘active learning’ in the classroom.

- Teachers will have the ability to spend less time lecturing content ‘at them’ and spend more time igniting students’ creativity, imagination and their problem-solving skills by actually ‘talking with them’.

Koller (2012) discusses ‘mastery of learning’ and how we can use technology to push mastery of learning from the left-side of the curve to the right-side. “Imagine if we could teach 98% of our students to be above-average.” Platforms such as this allow educators to spend time where it matters. Koller closes presentation by asking, “If we could offer a top-quality education around the world to everyone for free, what would this do?

- Universal access to education would establish education as a fundamental human right;

- Would enable life-long learning;

- This would enable a wave of innovation, making the world a better place for all of us!”

Salman Khan in CBS News 60 Minutes (Schrier, 2012, March 11) interview, “Khan Academy: The Future of Education” also focuses on how new tools allow for less lecturing and more interaction with students. His software platform has been piloted in math classrooms in San Francisco and also allows more time for students to receive 1:1 help from the teacher. By means of ‘flipping the classroom’ students essentially do their homework (problem set modules to enhance understanding) at school and the night before class they learn concepts (doing their schoolwork at home by watching videos).

Platforms such as the Khan Academy allow students to work at their own pace to have mastery of concepts before moving on and the teacher is utilized as more of a tool, facilitating in role of coach/mentor. In this model, teachers have access to real-time dashboards with ability to monitor each students’ progress (either individually or as a whole class section). The key here, is if the teachers are trained properly, they are able to use their time more effectively. It encourages smaller groups of students to engage in projects with peers or problem-based learning. Student peers interact to humanize the classroom with a ‘learning experience’ and value-added time from the teacher.

This technology allows researchers to better understand what paths to learning are most effective. The technology encourages students to fail and experiment, but with the expectation of mastery. As a non-profit entity, the Khan Academy is able to focus on delivering its core mission – a free education to anyone, anywhere.

Coursera and The Khan Academy are just two great examples of differentiated learning in action. There is also profound social value delivered as this interactive content will never grow old – each platform focuses on core foundational concepts students need to learn and master before they are able to move forward academically to the next core step. Other Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs) such as Udacity, and edX are experiencing steady growth (Gray, 2017). Recently a U.S. bill was introduced that would enable public universities in California to award credit for classes taken online with approval from the American Council on Education (Heussner, 2013).

During the widespread development of open access online course materials in the last two decades, advances have been made in understanding the impact of instructional design on quantitative outcomes (Network World, 2014). Much less is known about the experiences of learners that affect their engagement with the course content. Through a case study employing text analysis of interview transcripts, Shapiro, et al., 2017 revealed the authentic voices of participants and gained a deeper understanding of motivations for and barriers to course engagements experienced by students participating in Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs):

Thirty-six participants in the courses were interviewed, and these students varied in age, experience with the subject matter, and worldwide geographical location. An examination of student statements related to motivations revealed that knowledge, work, convenience, and personal interest were the most frequently coded nodes (more generally referred to as “codes”). On the other hand, lack of time was the most prevalently coded barrier for students. Other barriers and challenges cited by the interviewed learners included previous bad classroom experiences with the subject matter, inadequate background, and lack of resources such as money, infrastructure, and internet access. When demographic data was added to the sentiment analysis, students who have already earned bachelor’s degrees were found to be more positive about the courses than students with either more or less formal education, and this was a highly statistically significant result. In general, students from America were more critical than students from Africa and Asia, and the sentiments of female participants’ comments were generally less positive than those of male participants. Most of the interviewee statements were neutral in attitude; sentiment analysis of the interview transcripts revealed that 80 percent of the statements were found to be positive rather than negative, and this is important because an overall positive climate is known to correlate with higher academic achievement in traditional education settings (Shapiro, et al., 2017).

Five state teachers of the year – representing Montana, Indiana, Nebraska, Colorado, and the Department of Defense Education Activity school system – spent three full days in Finland in July 2017, where they visited the University of Helsinki and the Finnish National Board of Education. They attended several workshops and panel discussions on developments in the Finnish education system, including phenomenon-based learning, which prioritizes interdisciplinary, student-centered projects (Will, 2017). Lessons learned from last year’s cohort of teachers who traveled to Finland include:

- Finnish schools are doing a lot of the same things U.S. schools are. The major difference is that teachers are held in higher regard.

- Teacher preparation programs are rigorous and selective in Finland, and there’s only about a ten percent acceptance rate. Because of that, teachers are not evaluated through standardized test scores.

- Teachers in Finland have the autonomy to decide what and how to teach in their own classrooms.

- A student-centered culture. “It seems to be a cultural expectation of students to do well in school. The two things I kept hearing from the Finnish people were the responsibilities of a citizen … to one, take care of your body, and two, take care of your learning. Education is a lifelong event, and it does not only happen in school, and it does not end when schooling ends” (Nelson in Will, 2017).

- Last year, Finland introduced a new national curriculum. In addition to the phenomenon-based learning element – meaning students are required to design and implement one interdisciplinary project each year – the curriculum is skills-based.

- There are seven skills the curriculum is based on, including cultural competence, multiliteracy, entrepreneurship, and “thinking and learning to learn”. Instead of being expected to cover certain content, teachers are expected to weave those skills into their lessons. It’s not “content versus skills, but content with skills” (Elo in Will, 2017).

- Lessons for the U.S. classroom include being inspired by the focus on sustainability in Finland’s curriculum; and taking a research-based practice, implementing it on a small scale, and then scaling it up (Will, 2017).

The Need for Project-Based Interdisciplinary Collaboration

The need for project-based interdisciplinary collaboration locally is evidenced by a message from the Governor for the State of North Dakota, Doug Burgum, to the North Dakota University System Office (N.D.U.S.), he reiterates “Nearly all of the world’s information is available for free online, and technology is changing every job, every organization and every industry. Given these powerful forces, we have the opportunity to reimagine education to help our students succeed in a 21st century economy” (Burgum, 2017, p. 2). Building on SB2186, the new “education innovation bill”, along with leadership at the North Dakota Department of Public Instruction, the Governor’s expectation is to empower parents, teachers and administrators to build an educational experience that promotes project-based learning, job shadowing, internships, flexible scheduling, and similar innovative practices, based on each district’s unique needs and circumstances.

By embracing ongoing collaboration and partnership between K-12, higher education and industry, career paths for a variety of industries and educational interests can be created, with the outcome of students being well prepared for the jobs of the future in the 21st century and beyond. In efforts to transform education, our educational institutions have an opportunity to embrace technology and the changes it is driving across industries to complete in a global economy (Burgum, 2017).

In addition, PBL encourages more rigorous learning because it requires students to take an active role in understanding concepts and content, which foster an enduring curiosity and hunger for knowledge. Since students are allowed the opportunity to apply classroom content to real-life scenarios, PBL also facilitates career exploration, technology use, student engagement, communication connections, and content relevancy (Buck Institute for Education (BIE), 2017).

Other partnerships strategies for real-world projects include Edutopia. Iowa BIG, an innovative high school in Cedar Rapids, Iowa, has replaced the traditional curriculum with an emphasis on passion, projects, and community. Making the interdisciplinary model work requires partnerships with businesses, nonprofits, and government agencies working in tandem toward a common vision (Boss, 2017).

Quest University Model

(Intent is to Focus Research on Undergraduate Higher Education Model)

Quest University Canada is Canada’s first independent, not-for-profit, secular university. Quest offers only one degree, a Bachelor of Arts and Sciences, and focuses entirely on excellence in undergraduate education. Unlike conventional universities where students take several classes simultaneously in a semester, at Quest students focus on single “block” courses that run three hours a day, every day, for 3-1/2 weeks. Maximum class size is 20 students. Students chose from more than 300 courses with a student to faculty ratio of 14:1. Quest University opened with a 73-student inaugural class on September 3, 2007. Current enrollment numbers equate to 700 students. All Quest faculty, known as Tutors, offer interdisciplinary, seminar-style courses which are discussion based. Living in a community is an integral part of the Quest experience. As such, students live on campus for all four years of their undergraduate degree.

The block plan created by Quest University allows students with flexibility to both focus and explore. Students continue course discussions and activities from one day to the next without interruptions, allowing for deep and meaningful learning. The block plan ensures students can participate in course activities fully without competing interests. With two 16-week semesters consisting of four blocks each, and two further blocks in the summer, students can create a course schedule that works for them. Students choose which months they wish to be on campus, and which months they wish to travel, work, or pursue other learning opportunities.

Each student is required to take between one and four experiential blocks as part of his or her academic program. These blocks are designed to meet each student’s academic and career interests and can include varied experiences. Each experiential learning block must be approved and supervised by the student’s faculty advisor or, as appropriate, another Quest tutor. Normally, experiential learning blocks are completed as part of a student’s individual Concentration Program and must contribute to the achievement of the learning outcomes agreed upon for the Concentration developed by the student and approved by the faculty advisor. Experiential learning blocks are treated in the same way as regular classroom-based blocks. They are an integral part of the formal curriculum, and they are based upon specific learning outcomes. They are supervised, involve assignments, and result in the awarding of grades. (Retrieved July 22, 2017 from https://questu.ca/academics/experiential-learning/.)

Quest’s vision of an innovative and independent liberal arts university in Canada emphasizes high-quality liberal arts and sciences teaching in a collegial setting without traditional departments. Quest operates on a block (one course at a time) teaching system, and the teaching schedule is typically six blocks per academic year. Quest has neither faculty ranks nor tenure; all full-time faculty members are offered renewable contracts and hold equal rank. They are strongly committed to principles of academic freedom. While they offer moral, intellectual, and some financial support for the research interests of their faculty members, their web site included the statement “if you are interested primarily in a traditional academic career focused on research, please do not apply for this position”. All qualified candidates are encouraged to apply; however, Canadian citizens and permanent residents are given priority.

Quest University fosters autonomy and creativity. More than 70% of Quest students study abroad with established partners via International Exchange opportunities. A Learning Commons promotes Quest’s interdisciplinary approach with a collaborative learning space to ensure students develop their quantitative reasoning and rhetorical processes. Fellowship Program recipients take the lead on intellectually substantive projects requiring creative and original thought, are invited to speak at the Quest Scholarship Conference, with the best student presentations providing a 30-minute talk on their summer research at the Public Library open to all members of the Squamish community.

Inquiry-based education in a personalized, interdisciplinary setting provides exceptional opportunities for those who choose their own path. Quest’s innovative curriculum, intentionally designed campus, and vital community practices encourage interactions between ideas and between people who love to learn. The intentional design allows for students and faculty alike to thrive in a uniquely designed learning environment. At Quest, they empower each other to take risks and continually improve. The ability to experiment and learn from failure in a safe space builds competence and confidence, allowing students to master crucial intellectual skills in pursuit of academic excellence. Quest celebrates their interdependent connections across campus and the globe. Close, collaborative relationships evolve among their diverse learning communities that change how they think, feel, and engage the world together (Quest University Canada, 2017).

Quest University Learning Outcomes

The Quest curriculum is informed by the following four general purposes:

• Personal and Intellectual Development

• Social and Civic Engagement

• Preparation for Further Learning

• Employability

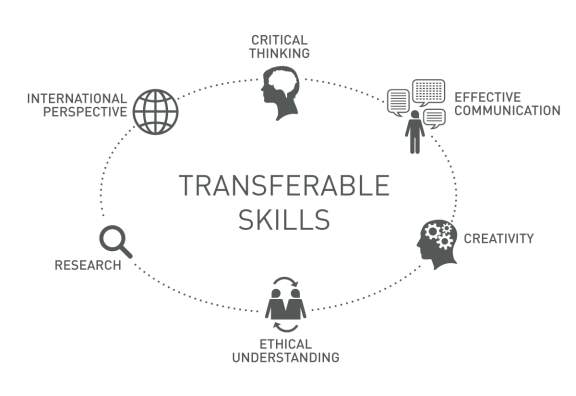

By encouraging the personal and intellectual development of its students, Quest University Canada aims to prepare them for the challenges of the 21st century. They hope to educate engaged, creative and thoughtful leaders and foster skills leading to rewarding careers or advanced studies upon graduation. To that end, they have designed the curriculum with the following learning outcomes in mind: critical thinking, effective communication, creativity, ethical understanding, research, and an international perspective. The six learning outcomes are all transferable skills, with a diagram included for reference (Figure 2.) These deliverable outcomes serve as benchmarks by which to measure student success, inform their own self-assessment, and guide their efforts to continually improve the Quest program of study.

Figure 2. Retrieved July 22, 2017 from https://questu.ca/academics/quest-learning-outcomes/

Gray (2013) first highlighted Quest University’s untraditional approach to education in The Blog with The HuffingtonPost.com, Inc. Most recently, the board of governor’s of the university issued a statement confirming Peter Englert “is no longer the president and vice-chancellor” of Quest University (Griffin, 2017). The statement published in the Vancouver Sun also indicates the board created a finance and audit committee, and has appointed an interim president to maintain leadership and stability of the university while they undertake a search for a new president.

Emerging Assessment

Evidence that coherence exists in a PBL system according to Wiley (2017) includes: clearly articulated student outcomes, often in the form of a Graduate Profile. District vision and mission includes or supports PBL as a key component of the instructional model when communication and messaging cultivates a shared vision and purpose of PBL to their teachers, students, families and community members. Additionally, according to Wiley (2017), policies and expectations (e.g., grading policies, curriculum pacing, etc.) enable and support implementation of PBL. From a public relations perspective, visuals or resources that call out district goals and priorities, with a connection to how PBL aligns to that vision can alleviate parent concerns. Moreover, allocating time to ensure collaboration, iteration, and reflection related to PBL heightens potential of successful integration across the system. Sustainability is seen when a shared belief exists that PBL is for all students, not just some students (Wiley, 2017). Additional artifacts of evidence per the Buck Institute of Education (BIE) as expanded upon by Wiley (2017) are supportive culture, capacity building, and a cycle of continuous improvement (Appendix A).

Quest University consistently ranks at or near the top of Canadian and United States universities in all four measures of educational excellence in the National Survey of Student Engagement (NSSE) which is published annually. NSSE developed ten student Engagement Indicators (EIs) that are categorized in four general themes: academic challenge, learning with peers, experiences with faculty, and campus environment. NSSEs ten Engagement Indicators include: higher-order learning, reflective and integrative learning, learning strategies, quantitative reasoning, learning with peers, discussions with diverse others, experiences with faculty, effective teaching practices, quality of interactions, and supportive environments. Overall, NSSE assesses effective teaching practices and student engagement in educationally purposeful activities. Purposeful institutional priorities and practices lead to student success in college. Institutions that align their resources to foster engagement potentially experience higher levels of quality – the marriage of purposeful engagement and institutional quality (Kuh, 2001).

Nearly all of the global rankings of universities claim they assess institutions across all the institutional core missions, including teaching. An interesting development in assessing excellence in teaching is currently under way in the United Kingdom (UK) as reported by Mohamedbhai (2016). In 2015, the UK government announced the creation of a new Teaching Excellence Framework (TEF) to be implemented in 2017/18 with the objective of recognizing and rewarding excellent teaching and learning. The purpose of the TEF is ‘to rebalance the relationship between teaching and research in universities and put teaching at the heart of the system’. Initially, the three metrics that will be used and for which data are readily available are graduate employment, student retention and student satisfaction, the latter being determined from a national student survey. However, doubts have been expressed as to whether these are the most appropriate criteria for assessing the standards of teaching in institutions. As an incentive for participation, the government has announced those institutions which have excelled in teaching would be rewarded with the right to increase their annual undergraduate tuition fees, currently capped at £9,000, to be aligned with inflation.

Research Questions

In this study, I explored the existing research on the inquiry and student-based pedagogical approach of PBL and then inquired specifically into one alternative university’s experience with its early phase implementation of PBL. Two essential questions guided my research: What are faculty and administrators’ experiences with implementing a project-based learning curriculum in their university at the undergraduate level? What are students’ experiences of participating in a project-based learning curriculum in said university? The goal was to learn from one alternative university’s early-stage implementation of PBL so that this type of pedagogical approach to curriculum can be effectively replicated in other universities and undergraduate classrooms, potentially in higher education institutions in the State of North Dakota.

Additional research questions that have potential to drive this study are:

Do universities plan to continue providing its faculty the expansive opportunities provided by PBL and other potentially innovative tools and ideas?

Does support exist within the structure for on-going professional development to build a culture of PBL?

Does the process by which Interdisciplinary Project Based Learning is implemented impact success of initiatives?

Is there a requirement for certain base knowledge before PBL can be an effective model?

Are our schools equipped to prepare students for this reality upon graduation – to be creative, work collaboratively, and use their resources to be successful in our fast-paced economy?

. . . as MEASURED BY . . .

References

Ambrose, S.A., Bridges, M.W., DiPietro, M., Lovett, M.C., & Norman, M.K. (2010). How learning works: 7 research-based principles for smart teaching. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Asghar, A., Ellington, R., Rice, E., Johnson, F., & Prime, G. (2012). Supporting STEM education in secondary science contexts. Interdisciplinary Journal of Problem-based Learning, 6(2).

Bell, S. (2010, January 1). Project-based learning for the 21st century: Skills for the future. Clearing House: A Journal of Educational Strategies, Issues and Ideas, 83(2), 39-43.

Blumenfeld, P.C., Soloway, E., Marx, R.W., Krajcik, J.S., Guzdial, M., & Palinscar, A. (1991). Motivating Project-Based Learning: Sustaining the doing, supporting the learning. Educational Psychologist, 26(3/4), 369-398. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00461520.1991.9653139

Boss, Suzi (2017, July 12). Partnership strategies for real-world projects: Students gain by taking on interdisciplinary projects with nonprofits, businesses, and government agencies. [Edutopia blog post]. George Lucas Educational Foundation. Retrieved on August 5, 2017 from https://www.edutopia.org/blog/partnership-strategies-real-world-projects-suzie-boss

Buck Institute for Education (BIE). (2017). What is Project-Based Learning (PBL)? Retrieved August 5, 2017 from http://www.bie.org/about/what_pbl

Burgum, Governor Doug (2017, July 31). A Message from the Governor – Creating the Future Together, 3. [E-Mail to the North Dakota University System (N.D.U.S.) Office] Bismarck, North Dakota, United States of America: State of North Dakota.

Dewey, J. (1916). Democracy and education: an introduction to the philosophy of education. New York: Macmillan, p. 393.

Dewey, J. (1938). Experience and education. New York, NY: Touchstone.

Duke, N (2016, Fall). Project-Based Instruction: A great match for informational texts.

American Educator, A Quarterly Journal of Educational Research & Ideas, 40(3), 4-11.

Free data science courses from John Hopkins, Duke, Stanford; Coursera offers massive open online courses, or MOOCs, for budding data scientists. (2014). Network World, Network World, March 26, 2014.

Fritz, J., & Whitmer, J. (2017). Moving the heart and head: Implications for learning analytics research. EDUCAUSE Review, (Online). Retrieved August 1, 2017 from http://er.educause.edu/articles/2017/7/moving-the-heart-and-head-implications-for-learning-analytics-research

Gray, J.F. (2013, March 20). Quest University’s Untraditional Approach to Education. [The Blog] The HuffingtonPost.com., Inc. Updated May 19, 2013. Retrieved July 20, 2017 from http://www.huffingtonpost.ca/john-f-gray/quest-university-education-squamish_b_2893170.html

Griffin, K. (2017, May 9). President of Quest University in Squamish no longer at private college. Vancouver Sun. Retrieved August 15, 2017 from http://vancouversun.com/news/local-news/president-of-quest-university-in-squamish-no-longer-at-private-college

Harada, V.H., Kirio, C., & Yamamoto, S. (2008, March 1). Project-based learning: Rigor and relevance in high schools. Library Media Connection, 26(6), 14-20.

Harris, M.J. (2015). The Challenges of Implementing Project-based Learning in Middle

Schools. (Doctoral dissertation, University of Pittsburgh).

High-Impact Practices. National Survey of Student Engagement. (2015). Bloomington, IN. Indiana University Center for Postsecondary Research. Retrieved August 15, 2017 from http://nsse.indiana.edu/html/engagement_indicators.cfm

Heussner, K.M. (2013, March 13). Online education could get big boost from Calif. bill backing web classes for credit. Gigaom. Retrieved August 15, 2017 from https://gigaom.com/2013/03/13/online-education-could-get-big-boost-from-calif-bill-backing-web-classes-for-credit/

Kilpatrick, W.H. (1921). Dangers and difficulties of the project method and how to overcome them: Introductory statement. Definition of terms. Teachers College Record, 22(4), 283-287.

Koller, D. (2012). What we’re learning from on-line education. [Video podcast], TEDTalks (June, 2012). Retrieved July 14, 2017 from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=U6FvJ6jMGHU&list=PLNeB8YmowQg-24-ITdPs65xd6bfUPAuij7&index=36

Kuh, G.D. (2001). Assessing what really matters to student learning: Inside the National Survey of Student Engagement. Change, 33(3), 10-17, 66.

Linn, P.L., Howard, A., and Miller, E. (Eds). (2004). The handbook for research in cooperative education and internships. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Lundeberg, M., Coballes-Vega, C., Standiford, S., Langer, L., & Dibble, K. (1997, January 1). We think they’re learning: Beliefs, practices, and reflections of two teachers using project-based learning. Journal of Computing in Childhood Education, 8(1), 59-81.

Macfadyen, L. P., & Dawson, S. (2012). Numbers are not enough. Why e-learning analytics failed to inform an institutional strategic plan. Educational Technology & Society, 15(3), 149-163. Retrieved August 1, 2017 from http://www.ifets.info/journals/15_3/11.pdf

Manturuk, K., & Ruiz-Esparza, Q. (2015, August 3). On-campus impacts of MOOCs at Duke University. EDUCAUSE Review, (Online). Retrieved August 1, 2017 from http://er.educause.edu/articles/2015/8/on-campus-impact-of-moocs-at-duke-university

Margie, O., & Tourish, D. (2004). Handbook of Communication Audits for Organizations (p.3.). New York, New York: Rutledge.

Markum, T. (2011, December). Project Based Learning: A bridge just far enough. Teacher Librarian, 39(2), 38-42.

Mitchell, J. (2015, December 7). Playing nicely in the sandbox – three tips for collaboration. [Hilborn: Charity eNews]. Retrieved August 5, 2017 from https://charityinfo.ca/articles/playing-nicely-in-the-sandbox-three-tips-for-collaboration

Mohamedbhai, G. (2016, September 18). Assessment of teaching in determing institutional excellence. [Inside Higher Ed – The World View blog]. Retrieved August 15, 2017 from https://www.insidehighered.com/blogs/world-view/assessment-teaching-determining-institutional-excellence?width=775&height=500&iframe=true

Neher, W., (1997). Organizational Communication: Challenges of change, diversity, and continuity. (p.85). Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

Pace, W., & Faules, D. (1989). Organizational communication. (p. 2). New Jersey: Prentice Hall.

Pulliam, J.D., & Van Patten, J.J. (2013). The history and social foundations of American education. 10th Edition. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education, Inc.

Quest University Canada (2017). Retrieved July 22, 2017 from https://questu.ca/

Riveros, A., Newton, P., & Burgess, D. (2012). A situated account of teacher agency and learning: critical reflections on professional learning communities. Canadian Journal of Education, 35(1), p. 205. Retrieved August 15, 2017 from files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ968812.pdf

Robinson, S. (2012). Constructing teacher agency in response to the constraints of education policy: adoption and adaptation. Curriculum Journal, 23(2), p. 244. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09585176.2012.678702

Robinson, S.K. RSAnimate. Changing Education Paradigms. (2010) [Google videos]

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zDZFcDGpL4U&index=26&list=PLNcB8 YmowQg24-1TdPs65xd6bfUPAuij7 Retrieved May 24, 2017. RSAnimate Video is taken and adapted from a speech given at the RSA on June 16, 2008.

Rose, J. (2012, May 9). How to break free of our 19th century factory-model education system. The Atlantic. Retreived August 6, 2017 from http://www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2012/05/how-to-break-free-of-our-19th-century-factory-model-education-system/256881/

Savery, J. R. (2015). Overview of Problem-Based Learning: Definitions and Distinctions (Preface). In H. L.-S. Andrew Walker (Ed.), Essential readings in problem-based learning: exploring and extending the legacy of Howard S. Barrows, (pp. 1-384). West Lafayette, Indiana, United States of America: Purdue University Press. Retrieved August 5, 2017 from http://www.worldcat.org/title/essential-readings-in-problem-based learning/oclc/870287072

Schneider, S. A., & Kalbfleisch, P. J. (2007). Communication and pandemic preparedness in rural critical access hospitals (Doctoral dissertation, University of North Dakota, T2007S3596). ODIN ALEPH Dissertations & Theses database. Document Identifier: OCLC (OCoLC) 639625576, pp. 1-78.

Schrier, C.D. (Producer). Gupta, S (Correspondent). (2012, March 11). Khan Academy: The future of education? [Television series episode “Teacher to the World” script]. In Danowski, M. (Ed.), CBS News, 60 Minutes. Retrieved July 14, 2017 from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zxJgPHM5NYI&list=PLNeB8YmowQg24-ITdPs65xd6bfUPAuij7&index=7

Wiley, B.L. (2017, June 28). It takes a system for high quality PBL. [Buck Institute for Education (BIE) blog post]. Retrieved August 5, 2017 from http://www.bie.org/blog/it_takes_a_system_for_high_quality_pbl

Will, M. (2017, August 4). Some top U.S. educators went to Finland. Their big takeaway: empower teachers. [Teaching Now – Education Week blog post]. Retrieved August 10, 2017 from http://blogs.edweek.org/teachers/teaching_now/2017/08/teachers_finland.html?cmp=eml-contshr-shr-desk

Appendix A

Emerging Assessment

Evidence that coherence exists in a PBL system according to Wiley (2017) includes:

Evidence of a supportive culture can take many different forms, including:

- Clearly shared beliefs and norms, which are actively referred to and used during meetings

- Shared decision-making structures, which are leveraged to guide PBL implementation

- Regularly scheduled time for collaboration across the system, and structures and policies that support and promote high quality PBL

- Recognition that celebrates success with PBL

- Structures focused on teacher and student agency, voice and choice

Evidence of this capacity building may include:

- Development of site-based leadership teams to ensure a distributed leadership

- Master calendar and teacher schedules that allow for job-embedded professional development and collaboration

- School-based or district-wide instructional coaching support,

- Alignment of teacher evaluation systems to the Gold Standard PBL Project Design and Teaching Practices

- Performance assessment and grading practices that align to PBL

- Families and community members actively involved in supporting project

- Consistent approach to sourcing and selecting teachers and staff who will be able to facilitate and support PBL instruction; hiring pipeline (leaders and teachers) preference PBL experience and commitment

- Leadership development opportunities are targeted and ongoing

Further evidence of continuous improvement per the Buck Institute of Education (BIE) may include:

- Periodic and planned self-assessments or reflections for the adults in the system

- Systematic use of protocols to reflect on, monitor, evaluate, and share evidence of implementation of high quality PBL

- Structures that support reflection and sharing, such as walkthrough or other means to gather school-wide information about the quality of PBL instruction

- Leaders are networked to create a community of practice to learn with and from

- Differentiated professional development that cultivates teachers’ and leaders’ strengths and ongoing understanding of PBL

Cite This Work

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing stye below:

Related Services

View allRelated Content

All TagsContent relating to: "Learning"

Learning is the process of acquiring knowledge through being taught, independent studying and experiences. Different people learn in different ways, with techniques suited to each individual learning style.

Related Articles

DMCA / Removal Request

If you are the original writer of this dissertation and no longer wish to have your work published on the UKDiss.com website then please: