Overcoming the Liability of Newness: Entrepreneurial Actions in the Chinese Food & Beverage Sector

Info: 18767 words (75 pages) Dissertation

Published: 10th Jan 2022

Tagged: International BusinessFood and NutritionEntrepreneur

ABSTRACT

Chinese food habits are currently experiencing rapid changes. The increased buying power of the consumers has led to the adoption of a new lifestyle which affects also their diet – both in quantity and quality. This trend affects consumption growth rates which become remarkably high for meat, dairy products, fish, oil, pasta, confectionery and convenience food. Such context, along with relatively recent global trade agreements has remarkably increased the interest of firms to enter this sector. Furthermore, the introduction of new distribution channels is deeply changing the purchasing system: hypermarkets, supermarkets, convenience stores, corner shops, and e-commerce are spreading in the country, granting a bigger and more diversified marketing platform for food enterprises. Given the considerable business opportunity existing in the Chinese market, an increasing number of entrepreneurs have entered the market. However, for many of them it still represents a challenge from many points of view. The continuously updating legal and food safety system, the different business culture approach, the policy framework as well as the changing dynamics of its economy, make it complicated for international businesses to be quickly successful in the Chinese market.

In such scenario, it emerges the necessity to face the so called phenomenon of the Liability of Newness. Thus, the objective of this study is to identify, through a quantitative analysis, the factors that have influenced the performance of enterprises operating in this sectors.

From the analysis it results that the firm’s size, the experience of the firm in the Chinese market are significantly correlated to its performance, with a positive effect. On the other hand, ….

ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS

ASEAN: Association of Southeast Asian Nations

F&B: Food & Beverage

GDP: Gross Domestic Product

IBM SPSS: IBM Statistical Package for the Social Science

IJV: International Join Venture

JV: Join Venture

MNE: Multi-National Enterprise

OECD: Organization for Economic Co-operation Development

RBV: Resource Based View

SIC: Standard Industrial Classification

SME: Small and Medium Enterprise

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Click to expand Contents

Dedication

Claims of Originality

Claims of Thesis Authorization

ABSTRACT

LIST OF TABLES

LIST OF FIGURES

1. CHAPTER 1 - INTRODUCTION

1.1 Background of the study

1.2 Objective of the study

1.3 Motivation of the study

1.4 Structure of the dissertation

Chapter 2 - Literature review

2.1 Data collection and methodology

2.2 Measures of firm performances

2.3 Determinants of firm performance

2.4 Research question

Chapter 3 - THE CHINESE FOOD SECTOR

3.1 Economic background

3.2 Grocery Retailers and Food Service

3.3 Market Overview

3.4 Demand for EU F&B in China

3.7 Opportunities for European firms: Niche Market

Chapter 4 - THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

4.1 Resource Based Theory

4.2 The contingency paradigm

4.3 Hypothesis

Chapter 5 - EMPIRICAL MODELS AND RESULTS

5.1 Econometric Model Specification

5.2 Data

5.3 Model Parameters

5.3 Estimation results

5.4 Discussion

Chapter 6 - SUMMARY LIMITATION AND RECOMMENDATIONS

6.1 Summary

6.2 Limitation of the study

6.3 Recommendations

Bibliography

LIST OF TABLES

Table 1. Overview of the most commonly cited literature on the topic of website usability and user’s interaction.

LIST OF FIGURES

Figure 1. Per Capita Major Food Consumption Urban Household

Figure 2. China’s Imported Food Trade Value 2005-2014 (in USD 100 million)

Figure 3. Country/Region of Origin of Import of F&B products in 2014 (in USD 100 million)

CHAPTER 1 - INTRODUCTION

1.1 Background of the study

The liability of newness is a concept described for the first time by Stinchcombe in 1965. According to him, the risk of failing of a firm is really high at the beginning of its life and decreases over time. Many researchers have agreed with this theory: Kor and Misangyi (2008), Politis (2008), and Sine et al (2006), among others. From this theory, other currents of thought have been developed, sometimes contrasting, such as the liability of adolescence (Fichman & Levinthal, 1991). However, from the literature review, it appears that the academic community has broadly accepted this first theory which has been further developed and applied by other researchers. This conclusion indeed has been reached also when the theory was applied to different sectors.

Although, the liability of newness has been often applied to new emerging industries, it is worthwhile to consider it also in mature industries when they witness substantial changes in a certain stage of their development (Abatecola et Al., 2012).

China is currently experiencing rapid changes in terms of food consumption. The increased buying power of the consumers has led to the adoption of a new lifestyle which affects also their diet – both in quantity and quality. This trend affects consumption growth rates which become remarkably high for meat, dairy products, fish, oil, pasta, confectionery and convenience food. Such context has caused an explosion in the import of food products, involving an increasingly diversified range of offer. In addition, the introduction of new distribution channels is deeply changing the purchasing system: hypermarkets, supermarkets, convenience stores, corner shops, and e-commerce are spreading in the country, granting competitive prices and improved sanitary conditions. Despite the considerable achievements, China could still make significant progressions, helping companies in sizing such opportunity. In line with this mission, this study aims at studying the factors that could help entrepreneurs to overcome the liability of newness in the Chinese food and beverage sector.

As highlighted in the research paper presented by Zhang and White (2016), where they analysed the liability of newness in the solar photovoltaic sector, entrepreneurs have often a key role in introducing new organizational forms which can build legitimacy and capabilities to overcome significant liabilities of newness. When in a specific sector it appears to be a liabilities of newness, two stream of research can be employed to study the phenomena: on an entrepreneurship level or/and at the institutional level (Überbacher, 2014). In this study, the attention will be focused on the entrepreneurship side. However, also a policy perspective will be employed, in order to give a stronger significance to the research. In fact, in countries where politics has a considerable influence in the economic system, it is almost necessary to include such element in the business research. Thus, the aim is to frame the question of what actions are required to overcome the liability of newness, intended as the entrepreneur’s ability to discover and exploit opportunities, as proposed by Venkataraman (1997). Studies concerning the liability of newness normally focus on new industries, however the challenge of surviving in the market is even greater in established or mature industries with established institutional “rules” compared to new and emerging industries in which the institutional environment is still in flux (David et al, 2013). For this reason, it is fundamental for business operating in these sector, such as the Food and Beverage one to have theoretical support and insights when the management sets the corporate strategy.

1.2 Objective of the study

More specifically, this study intends to empirically test the factors that influence the performance of enterprises in the Chinese food and beverage sector. Given the rapid change this sector is experiencing, it is important to understand which companies have been abler to seize the market, so that the other entrepreneurs can acquire knowledge of the market and build from these insights effective business strategies. Nevertheless, China has experienced a strong development that could be soon replicated by other countries in Asia; ASEAN for instance. Therefore, the results of this research could be soon applied to other emerging economies with similar dynamics.

The results of this research could be of interest to three main groups: managers, public-policy makers, and researchers. For the first group, firm’s performance is important because it ensures the its survival and growth (Samiee and Walters, 1990). For public-policy makers, developing long term plans to boost enterprises’ performance is a strategic action that supports the development of the country and support its growth (Sousa et al., 2008). For researchers these results could be useful to develop new models and theories.

1.3 Motivation of the study

The motivations behind this study are multiple and of different nature. Generally speaking, the Chinese market is a relatively new case of economic development which has no precedent in history. This and its particular social, political, and legal environment make it complicated for foreigners and local entrepreneurs to access the different economic sectors and be successful in them. Within all the industries, the food and beverage is one of those which is considerably complex and rapidly changing. As stated by The Economist (2015), China has undertaken a series of reforms aimed at reaching food self-production, in order to be less dependent from unpredictable world markets. However, this policy not only has caused inefficiencies in the sector, but also does not match the actual needs of modern Chinese consumers.

Indeed, the rapid change in taste and need in quality have open a big room of opportunities for foreign companies, which cannot be still fulfilled by Chinese producers. However, exporting or starting a food chain in this country can be particularly challenging for firms, that need to set a logistic system and follow a strict food safety regulation which is constantly rising in complexity, with the aim of fulfil the safety standards required by consumers in the country.

For this reason, this study has decided to focus on this strategic sector. Even though the food & beverage market is growing, more firms are entering the market. For SMEs it can be difficult to compete with the power of multinational food companies on mass-market foodstuff which becomes increasingly price-driven. However, also MNEs with extensive experience in the market have recently suffered big losses in China (New York Times, 2017), underlying the need to explore this market from a strategic perspective. From an academic point of view, this paper aims at filling different call for papers which have been identified in the topic of the liability of newness.

Although many researchers are continuing to confirm the validity of this theory, not so many have studied the determinants of the firm success or have demonstrated them. An example of these calls: “despite lively research commitment, an up-to-date systematization of the theoretical and empirical findings on this topic is missing” (Cafferata et. Al, 2009; pg 3). Moreover, Abatecola et Al. (2012) made a call for papers that focus on non-US firms given the large amount of studies produced in the American region, that fails to explain the phenomenon in a global scale. In addition, having reviewed many studies on the liability of newness in the literature review, to the best of my knowledge none of the studies has focus on the food sector in the China, leaving room for this research paper. Thus, this paper aims at contributing to fill this research gap through a systematic empirical study.

1.4 Structure of the dissertation

The present study is structured in six chapters:

In the chapter one, the introduction, the general background, the objective, the motivation and the structure of the research are explained to the reader.

Chapter two presents an in-depth review of the literature, as well as the methodology and the research questions.

In chapter three, the economic background of the Chinese food sector and its structure are extensively discussed. In addition, in this chapter the Chinese business environment is also presented, with the main elements which distinguishes it from the other markets.

Subsequently, in chapter four the theoretical framework is presented and discussed.

Chapter five focuses on the data analysis, with a first part where the econometric models results are presented and lately discussed.

In chapter six, a summary of the study has been inserted, after which conclusions, limitations and recommendations are presented to the reader.

Chapter 2 - Literature review

In the following chapter, the literature reviewed for this research will be presented. The chapter is divided into three main sections. The first one is dedicated to the brief explanation of the methodology and how the data has been collected. The second section exposes the determinants and measures that researchers have identified in previous studies in relation with the firm performance. In the third section, the determinants identified in the literature review are discussed. In the final part the research question is presented to the reader.

2.1 Data collection and methodology

The data used in this study is the annual industrial survey data which has been withdrawn from the Chinese National Bureau of Statistics (NBS). This database includes financial information for industrial firms with annual sales of at least 5 million RMB (roughly U.S. $680,000, according to the official 2007 exchange rate) from 1998 to 2007. The annual number of observations ranged around from 160,000 to 330,000 belonging to a total of 550,000 firms (codebook in appendix). By law, all firms in China are required to participate in the NBS survey. Several recent studies use the annual industrial firms’ database (Brandt, Van Biesebroeck, and Zhang, 2011; Chang and Xu, 2008; Hsieh and Klenow, 2009; Park, Li, and Tse, 2006; Zhang, Li, Li, and Zhou, 2010).

While this database has an advantage in creating a panel with its unique firm identifier, it has a limitation in that it contains only firms with 5 million RMB or more in sales.

The chosen dataset covers a period of time which is considerably interesting to analyse from a strategic point of view. In particular, it covers a period of time that corresponds to the emerging stage of the market, when there was still a lot of uncertainty and new ventures had relatively low experience and information to set the ventures’ strategy.

After 2008, the Chinese food market has radically changed also from a consumer point of view. The greater and greater influence from western countries has had an effect on the taste and food preferences. As consequence, a “standardization of the taste” has interested the market and China has become since then even more attracting for international businesses. Indeed, as the scope of this research is also to study the strategic behaviour of firms in emerging economies, the considered period might be satisfactory in this purpose.

In the research, the above mentioned data are treated with quantitative methods. In particular, the variable identified in the literature review will be analyse through a multiple linear regression model. In doing so, the significance of the correlation between the dependent and the independent variables will be tested as well as its weight.

Although in a first attempt, this study aimed at taking into consideration longitudinal data, for different reasons, it has been decided to analyse only one year of the available data, namely 2007.

Indeed, observing the same units over time leads to several advantages over cross-sectional data or even pooled cross-sectional data. The main benefit is that having multiple observations on the same units allows to control certain unobserved characteristics of individuals, firms, and so on. The use of more than one observation can facilitate causal inference in situations where inferring causality would be very difficult if only a single cross section were available (Brady, 2009). A second advantage of panel data is that it allows to study the importance of lags in behaviour or the result of decision making. This information can be significant since many economic policies can be expected to have an impact only after some time has passed (Saunders, 2011).

Having recognized the validity of longitudinal studies, this paper decided to focus on a one-year analysis because of problems related to the data and the analysis methodology. As highlighted by Chang and Xu (2008), in the dataset there are many cases in which the same firms with exactly the same names and the same addresses had different firm identifiers in different years because significant changes in ownership, such as joint ventures and mergers and acquisitions, occurred. In their case, they developed a detailed software algorithm to assess whether firms’ demographic information matched with the same firms’ observations across years. In addition, for each year, 11-19 % of the sample firms exited the database, and 11-22 % of the firms that appeared in the database were new. Given the complexity of the analysis, the study has focused on a cross sectional econometric analysis.

In order to assess the significance and effects of the independent variables, the software IBM SPSS STATISTICS have been employed. SPSS stands for Statistical Package for the Social Science. The software contains a great variety of statistical techniques that can be applied on the same dataset. Given its broad usability, SPSS is used in many different field of the social sciences and also in the research area of other sciences.

2.2 Measures of firm performances

Measurement of performance can offer significant and invaluable information to allow management’s monitoring of performance, improve motivation, report progress, pinpoint problems and communication (Waggoner, Neely & Kennerley, 1999). Accordingly, it is to the firm’s best interest to evaluate its performance. Moreover, performance measurement is critical in performance management. Through the measurement, professionals can create simplified numerical concepts from complex reality for its easy communication and action (Lebas, 1995). The simplification of this complex reality is conducted through the measurement of the prerequisites of successful management. On a similar note, Bititci et al. (1997) contended that performance measurement is at the core of the performance management process and it is of significance to the effective and efficient workings of performance management.

Although enterprises can be evaluated from different points of view, as stated by Al-Matari et al. (2014), the most common indicators of firm performance are financial measures. Among them: the level of Return on Assets (ROA), Return on Equity (ROE), Earnings Per Share (EPS), Divided Yield (DY), Price-Earnings Ratio (PE), Return on Sales (ROS), Expense to Assets (ETA), Cash to Assets (CTA), Sales to Assets (STS), Expenses to Sale (ETS), Abnormal returns; annual stock return, (RET), Operating Cash Flow (OCF). Most of these proposed measures have been utilized by studies regarding governance.

2.3 Determinants of firm performance

Several studies have been developed in the theme of the liability of newness. However, not many have focused on the determinants of the firm’s success in the market. From a revision of the literature review, the following are the variables that have been selected as more pertinent to the Chinese market.

Firm size

A concept closely related to the liability of newness is the liability of smallness. Several scholars (Hannan and Freeman, 1984; Freeman, Carroll and Hannan, 1983; Sutton, 1997) have stated that the mortality rate decreases with increased size. Thus, the liability of smallness suggests that size matters, and states that bigger is better. In other words, the theory of the liability of smallness suggests that expectations of success favour large firms over small ones and, on average, small firms have a higher likelihood of failure. The liability of smallness emerges from the concept that small firms do not perform as well as large firms and have higher failure rates due to problems of attracting, recruiting and retaining highly skilled workers, raising capital, and because of higher administrative costs (Aldrich and Auster, 1986). Also, legitimacy problems with external stakeholders (Baum and Oliver, 1992; Baum, 1996; Baum and Oliver, 1996).

In addition, bigger firms can also develop more easily economies of scale, guaranteeing them lower costs and better performance (Bonaccorsi, 1992). Moreover, large firms have greater access to market power (Bain, 1956) and less dependability on external resources (Baum and Oliver, 1996), than small firms. Agarwal et al. (2002) argue that the liability of smallness varies in accordance with the stage of the Industrial Loan Company. They propose that it is less of a liability during the mature stage of an industry than during the growth stage. Indeed, during the mature stage all firms regardless of size face higher mortality rates. However, during the growth stage there is an unequivocal growth imperative, since the basis of competition puts small firms directly against their larger counterparts (Mellahi and Wilkinson, 2004)

It is recognized that the size of the firm deeply affects also its strategy and therefore its success in the market. However, there is the so called OE scholars who believe that the population and industry matters more than the firm’s strategy. In fact, they argue that since the environments change faster than organizations, the performance of the firm is more influenced by the environment where they operates than the firm’s strategic choice. However, as highlighted by Mellahi et Wood (2003) the main weaknesses of these scholars is that they ignore an important part of the business system. Indeed, by putting all the emphasis on external factors, little attention has been put with the question of why is it that firms in the same industry facing the same industry-level challenges succeed while other fail (Flamholtz and Aksehirli, 2000).

This variable is generally measured through the number of employees, the level of sales or the volume of firm assets. In such context, taking into consideration the rational introduced by Agarwal (2002) it is logic to believe that size does matters in the Chinese food and beverage sector. Although as an industry, the food one is normally recognized as mature, the deep changes registered both from consumer and regulation side, would make it consider as growing industry.

Firm’s entity type

China represents one of the most appealing markets in the globe nowadays, ranking first in terms of market dimension in many sectors, including the food one. Although many firms have attempted doing business in the country, many of them have failed in their entry-market strategy. For Western businesses, the Chinese market results very unique and challenging from different points of view. An aspect which is very different from the Western world is the importance of the network, or guanxi in Chinese. As stated by Davies et Al. (1995), there is an underlying structure of four factors describing the its benefits, which may be explained as procurement, information, bureaucracy, and transaction-smoothing. However, as a foreign firm building guanxi in Mainland China could represent a real obstacle that can compromise the whole business experience in the country.

In particular, the lengthy negotiation process, bureaucratic delays, the difficulty of identifying the real decision-maker in Chinese business dealings Lu (1998) make it almost a must to find a local partner that could help the business in dealing with these issues Child and Yan (2003). Therefore, the creation of an international joint venture (IJV) offers offer foreign firms a strategic means to gain access to China’s domestic market, acquire legitimacy, reduce costs, gain power compared to their competitor and learn about the Chinese environment (Osland and Cavusgil, 1996). Having said this, the challenge it is also to find the appropriate partner that could fit the business in forming an (IJV). From the study conducted by Luo (1997) it emerges that both strategy and organization of the local partner influence the performance of the IJV. For example, among strategic traits, absorptive capacity, product relatedness, and market power are favourable to IJVs’ market and financial outcomes.

Although many researches have argued about the importance and benefits of having a local partner, many entrepreneurs have had problems in dealing with their Chinese counterparts.

Some of the problems that might occur are mostly related to technology transfer and illegal technology acquisition by the Chinese partners. This is a risk that is undertaken by food companies too that might share secret receipts, techniques that can be copied. However, firms in this sector can face also other types of problems. For instance, on March 29th 2017, the news agency Reuters has stated that the IJV created by Dutch dairy Royal Friesland Campina and the Chinese Huishan Dairy was in crisis after that the Chinese partner suffered a $4 billion loss in shares in a single day. After this event, the IJV remained operational, but went under close monitoring under the Dutch firm, which insisted in serving its Chinese customers. Huishan Dairy justified the loss stating that it had missed loan repayments and lost contact with a key executive in charge of its finances and cash (Reuters, 2017).

Having said this, given the difficult legal and operational Chinese system, it is believed that a Chinese partner would still benefit a food enterprise in approaching this market.

Belonging to a cluster

China’s rapid economic development and growth in industrial output has increased the influx of foreign capital into the country (Wang and Mei, 2009). Foreign businesses have seen opportunities both from the supply and demand side in the country, starting both production sites and sales operations in China.

This process has had implications in the industrial structure of the country. Indeed, it has had as consequence the development of industrial districts. Historically, this type of industrial organizations has enable firms to cluster and to exploit dynamic competitive advantages deriving from the existence of external economies and collective action (Schmitz, 1999), but also to provide better working conditions and wage levels for labour. Empirical studies about Italian industrial districts show that Italian industrial districts often offer a good standard of living for workers, with higher wages and employment levels, and higher rates of wage growth.

Territorial Governance and Cohesion

Having the world’s largest population and fourth largest territory, China’s size renders it difficult to govern. In order to overcome this problem, the Communist Party has created a managing system where the Central Government delegates important powers to Local Governments. As a result, China’s leaders constantly worry over the task of keeping an intricate balance between implementing in accordance with local conditions versus promoting national goals (Chung, 2016). With the attempt to rule directly throughout the country, during the years the Central Government has greatly decreased the number of provinces, which passed from 53 in 1949 to the today’s 31. The Central Government has also the duty of distributing financial resources to the different provinces. For effective local governance, the central government needs a wide range of tools to be well informed about local performance and to better facilitate central-local communication. However, this tools have shown some weaknesses during their utilization. For instance, it was widely publicized in 2012 that the sum of the provinces’ GDP surpassed China’s total GDP by a margin of 11percent (Kao, 2013).

Historically, China has had some commercial centres which have boosted the local economy, distinguishing it from the other provinces which were less accessible to foreign exchanges. An example is Shanghai, where trade with the Western world started longer before than in other provinces. The same phenomenon has been registered largely in all the East cost of the country. However, this different allocation of resources has caused a lot of economic inequality within provinces, leaving the Central and Western provinces in less favourable conditions compared to the Eastern ones. For instance, In 1998. the export as a ratio of GDP was 29.0%. 3.5%. and 4.2% in the eastern, central and western regions, respectively. This shows that the eastern coastal area enjoyed a much higher benefit from exporting than the other regions (Lin and Chen, 2004).

In order to overcome this problem, the Central Government in 1999 has officially launched Western Development Strategy (Tian, 2004) with the objective to balance the country development and avoid potential discontents from the “marginal population”.

The western region targeted by the Western Development Strategy consists of 12 provinces, municipalities and autonomous regions including Shaanxi, Gansu, Inner Mongolia. Qinghai. Ningxia. Xingjiang. Sichuan. Chongqing (designated as a centrally administrated municipality in March 1997). Yunnan. Guizbou, Guangxi and Tibet.’ The region covers an area of 6.850.000 square kilometers, roughly 71.4% of the nation’s land area and has a population of 355 million. This region is home to most of China’s around 100 million ethnic minorities (Tian, 2004).

Within this area, the Central Government has identified some so called “nodes” that should function as main engine to boost the economic development: Shannix, Sichuan. Chongqing municipality. Yunnan, and Xingjiang.

In this areas, the Central Government has activated a series of economic reforms that are supposed to attract foreign investments. The effects are already visible at a multinational level. Indeed, the city of Chengdu for example hosts the majority of the overseas Top 500 Fortune firms which arrived in China (GoChengdu, 2017). Therefore, the aim of this study is also to understand how the different policies and strategic decisions made taken these into considerations have affected the businesses’ performance.

Not many researches have linked the effect of policies into business. This is very important in the food industry, where there are a lot of regulations and the government has a heavy power in the economic system.

GDP

Although many researchers have focused on the success determinants of IJV, few have analysed the implications of macroeconomics variables on the strategic decisions taken by foreign managers. In particular, China is now leaving a stage of economy called “transitional” which implies different dynamics compared to the previous stage of centrally planned economy; this new interface affects also the survival of IJV in the country (Steensma and Lyles, 2000).

After opening its door to the external world, in the last two decades China has lived a period of great economic expansion, driven by the manufacturing sector and export (WEF, 2015). However, during the period analysed in this study the country GDP has registered both increasing and decreasing trends and from a strategic point of view it is interesting to understand which of these trends has been more favourable to IJVs. Generally speaking, the rising in GDP would benefit and attract foreign firms in approaching a market, as it has been studied by Julian (2005). However, little evidence has been found that identifies which of the trends (rising or decreasing) has actually benefited firms the most.

Experience in the Chinese Market

When entering an emerging economy, business managers have to face a very important strategy dilemma: should the firm be an early mover and be a pioneer in exploring potential market opportunities before competitors enter these markets, or should it be a late entrant and wait until the uncertainties in the regions are resolved by earlier entrants? (Isobe et al., 2000). The principles of internationalization theory suggest that the knowledge acquired through experience from business activities in a specific overseas market is the primary means of reducing foreign market uncertainty (Katsikeas and Morgan, 1994). Therefore, if this concept is applied also to emerging economies, it would more convenient for foreign firm to enter the market in an early stage. This assumption has also been demonstrated by

Isobe et al. (2000) where they showed in their study that he timing of entry had a significant and positive direct impact on performance of Japanese firms in the Chinese market.

Same findings were brought by Luo (1998) that stated that early entrants outperform late movers in terms of local market expansion and asset turnover. On the other hand, he added that late movers were superior to early entrants with regard to risk reduction and accounting return during the initial period of international expansion.

With reference to Chinese food market, it can be assumed that early entrants gain competitive advantage when entering the market in the early stage of its development. In doing so the firm can acquire a deeper knowledge about the local consumers that can allow it to better satisfy local customers.

2.4 Research question

Having conducted the literature review, the research question proposed in this study is: what factors and how they influence the performance of firms in the Chinese food & beverage sector?

Chapter 3 - THE CHINESE FOOD SECTOR

3.1 Economic background

The Chinese Economy is a singular example of economic development that has discomposed the old global economic system. Before the development of the BRICS, the world economy was mostly dominated by the Western economies, US and Europe, and Japan in the oriental world. This scenario has started to change in 1978, with the introduction of structural reforms that resulted in the opening of its economy to the world, when China has accomplished what has been defined by many researchers “The Chinese economic miracle” (Ray, 2002).

The elements that have contributed to the economic miracle have mostly been the rapid growth of inputs, such as capital and labour, and a successful transition from state-socialist controlled economy to a market economy (Eberhard, 2013). As a result, China has consistently been the most rapidly growing economy on earth, sustaining an average annual growth rate of 10% from 1978 to 2005 (Li and Naughton, 2007). Moreover, China is the most populous country in the world, with about 1,364 billion inhabitants in 2014 (World Bank, 2015) and this element added to its rapid growth, made it possible to China to become the second biggest world economy, just after USA. Its increasing weight in the global economy has been also remarked by the IMF, which has recently lift the Chinese Yuan to Elite Lending-Reserve Currency Status (Wall Street Journal, 2015).

Having said this, this trend has certainly changed in the past years. Since recording its last double-digit growth (10.4%) in 2010, the Chinese economy growth has effectively decelerated by 30% in five years. Most of the slowdown occurred in 2011 and 2012 when reported growth was 9.3% and 7.7%, respectively, leaving China’s GDP growth slows to 6.9 % (WEF, 2015).

This decline in Chinese growth will certainly have a noticeable effect on the rest of Asia, mostly due to the size of the country and its close ties with neighbours, as well as their direct investment abroad. However, the impact will be greater in some countries than in others. For some, it represents even a chance. Since one of the causes of what is happening in China is the increasing of wages, countries like Bangladesh and Myanmar are working to increase its share of the world market sectors that used to be dominated by the Chinese industry.

China’s growth performance is almost certain to deteriorate because of the overhang of its real estate bubble, massive manufacturing overcapacity, and the lack of new growth engines, leaving devastating consequences like the devaluation of the Yuan, stock market collapse, falling property prices, doubts about the reliability of the published data and uncertainties about the rebalancing process the authorities have launched.

A Chinese slowdown has a big impact on the global economy, in particular on commodity- producing economies because China extensively consumes raw material like aluminium, nickel and copper. However, Chinese consumption has been registering healthy growth in recent years: it grew 10.9% in 2014 (WEF, 2015).

The importance of China in the global economy is evident also in terms of raw materials (commodities) it imports, produces and consumes. Focusing the attention on the imports, the data shows that China at the moment is the world’s largest importer of commodities (The Economist, 2015; Roache, 2012). As a consequence, all the decisions made by the Chinese Government have a great effect on the global market.

This effect is particularly intense in the global food market. From 1978, China introduced a set of reforms aimed at achieving self-sufficiency in food production, which was achieved in 2002. However, after this year, China restarted to import increasingly food and in 2012 it became the largest importer of food, ahead of US. This leader position covered by China in the food market, put the country at the centre of the attention when researchers want to analyse the actual and the future state of the market.

3.2 Grocery Retailers and Food Service

Although this study does not intend to analyse the food service and grocery retailers, it is important to briefly describe the recent trends they have registered. As the final components of the food chain, these two systems have a great influence in the success of food producers and distributors.

The Chinese grocery retailers experienced slower value growth in 2014 (5%) than in 2013, mainly due to rising store rental which caused negative growth of outlet number; Shanghai is one of the areas that most suffered of such real estate booming pricing. On the other hand, rocketing sales from internet retailing channel also limited sales from grocery retailers in China. More varieties of products are selling from internet retailing not limited to foods but also consumer appliances, apparel etc are attracting more consumers to purchase online, which dampened growth of grocery retailers.

The Chinese foodservice sector is the largest in the world, with 7.3 million outlets and sales valued at US$510.8 billion in 2013. The industry has seen impressive gains over the past five years, registering a compound annual growth rate of 12.2% since the US$322.6 billion recorded in 2009. This was a result of steady demand due to the accelerated pace of life and rising household income. An increasing number of domestic consumers chose to dine out or enjoy delivered or takeaway meals instead of cooking at home.

Future growth is expected to remain a strong but decelerated 7.6% to 2018, as consumers rein in their spending and the industry works to overcome increasing operating costs as well as the fallout of food safety scares.

In addition, Western-style consumer foodservice, such as fast food, cafés/bars and 100% home delivery/takeaway, has become more popular due to the ever-faster modern lifestyles and the rising acceptance of western dining culture. In Particular, as shown in table 1, the Western Style Restaurant category is the one that has experienced the greatest growth.

3.3 Market Overview

China continues to be the world’s largest consumer market for food and beverage (F&B) products, having surpassed the US in 2011. So the Chinese market becomes increasingly interesting for foreign brands, especially as Chinese consumer shifts towards a more Western behaviour. Despite a growing local competition and a fragmented distribution infrastructure, selling products in China will likely grow further and it becomes a good opportunity for European SMEs. In the first quarter of 2015, F&B exports from Spain to China has grown of 48% compared to the year before. In 2014, the import of dairy products (milk powder not included) from France has grown by 11% (EUSMES, 2015). Growth of imported F&B products is driven by rising disposable incomes, water scarcity issues, limited arable land, improving logistics systems, urbanisation, growing taste for foreign foodstuffs, as well as growing concerns for food safety. In particular, opportunities for European SMEs in this sector exist for the following products: dairy, wine, pasta, pasta sauces, olive oil, tomato products, beer, chocolate and high-end confectionery, breakfast cereal, pre-packaged biscuits and snacks, coffee and meats, as well as baby food/infant formula.

3.3.1 Market Trends

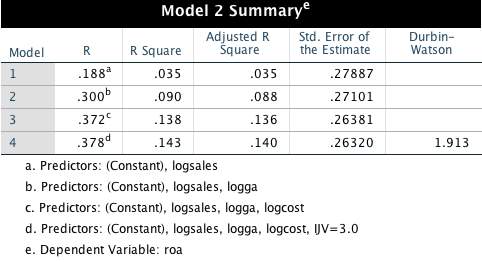

China is the second-fastest growing F&B market in Asia, with an average annual growth rate of 30% between 2009 and 2014. The Chinese food service sector is the largest worldwide with EUR 440 billion turnover in 2014 and 7.3 million outlets (China Internet Watch, 2015). Vegetables and grains are the most consumed F&B products in China, with Chinese citizens consuming over 100kg of fresh vegetables and around 80kg of grains, respectively, per household in 2012. Notwithstanding their significance, the consumption of these two F&B categories has declined since 1990. In contrast, as is it possible to see in the following graph, poultry and meat products (poultry, pork, beef and mutton), aquatic products, milk and fresh fruit grew in popularity between 1990 and 2012, albeit at a modest rate (Chinese National Bureau of Statistics, 2014)

Figure 5.1 Per Capita Major Food Consumption Urban Household

As for foreign business, quantities of China’s F&B imports have increased greatly. Widely confirmed, the recent rise in household available income and scandals over food safety have been key drivers that have boosted rapid growth in China’s F&B import market.

Food safety scandals include the 2008 tainted milk scandal, the 2013 discovery of 15,000 dead farm animals in the Huangpu River and, more recently, scandals in fast food chains (EUSME, 2015). These incidents have substantially undermined Chinese consumers’ trust and confidence in domestic food standards and production processes. Consumers’ purchasing decisions are deeply influenced by food safety.

3.3.2 Market Growth Drivers

The actual basket and quantities of imported food in China have been mostly shaped by the different policies that the Chinese Government has introduced over the last decades. In 1978, China embarked on a policy of achieving self-sufficiency in food. As the country’s economic reform program began to take hold and productivity in its agricultural sector increased, China managed to achieve this goal by the end of the last century. In fact, China surprised many observers when it became a net exporter of agricultural products in 2002 (Swinnen, 2010), its first year as a member of the WTO.

However, a lot has changed since then. In 2012, WTO stated that China had surpassed the United States to become the world’s largest importer of agricultural products. Despite a rural population of 500 million farmers, China has been unable to meet the country’s growing demand for grains, soy beans and other commodities.

China’s mix of imports also reflects policy decisions to prioritize self-sufficiency in cereal grains and to promote feed imports. During the mid-1990s, officials cut tariffs and waived value- added tax on imports of soybean meal, DDGS, and other grain-milling by products to address deficiencies in feed raw materials (Trostle, 2010). Furthermore, during the years before and after WTO accession, the rate on soybeans was also lowered to 3 % and rations were eliminated on imports of vegetable oil and soybeans. China, however, retained stricter control over the imports of cereal grains. In its WTO accession, China agreed to tariff rate quotas (TRQs) for rice, corn, and wheat that allow restricted quantities of each commodity to rush into the Chinese market at low tariffs. Market analysts report that Chinese importers turned to DDGS, barley, and sorghum as alternatives to corn because there is no import quota for these commodities (Jewison and Gale, 2012).

China’s domestic support has also focused on grains, including direct payments based on area planted in grain; support prices for rice, wheat and corn; and transfer payments to major grain- producing counties (Gale et al., 2013). Price supports were introduced for soybeans, rapeseed, and cotton, but persistently higher returns for grains resulted in land shifting to grain. China’s Minister of Agriculture argued that Government policies produced 10 consecutive growths in grain production during 2003-13 (Han, 2014).

3.3.3 Determinant Factors of the Growing Demand for Food

There are several factors that have contributed in shaping the trend registered in the Chinese food and beverage sector. The first one is the process of urbanization that from 1978 have interested approximately 260 million farmers that have moved from to rural areas to the cities. This process has remarkably impacted the Chinese economy in two ways. On one hand, it has taken away a large amount of labour force from the agriculture sector, causing a relative loss in production, although the productivity has increased at the same time, thanks to the technological development. On the other hand, it has increased the demand for food in the cities, which are generally completely dependent from the rural areas for food products.

The rising in income and wages that has interested China is another main factor. The income per capita has passed from about $1000 in 2002 to $5000 in 2012, and this event has affected the Chinese household dietary habits (World Bank, 2015).

At the same time, rapid developments in transportation (including major rail improvements and road arteries) are expanding the economic potential of second- and third-tier cities. In terms of F&B, infrastructure improvements are speeding up distribution times, efficiency and costs, thereby stimulating local economies by raising consumer demand for higher value products. Cold-chain infrastructure remains poor, greatly affecting distribution of frozen foods. With a population of over 1.3 billion, China has emerged as the world’s largest consumer market for F&B, surpassing the United States. By 2018, the Association of Food Industries predicts that China will be the world’s largest consumer of imported food. According to Euromonitor International (2015), the Chinese food service sector is now the largest in the world, with a EUR 440 billion turnover in 2014 and 7.3 million outlets. China has an increasing demand for protein, dairy and meat products, including chicken and offal.

3.3.4 Imported Food and Beverages

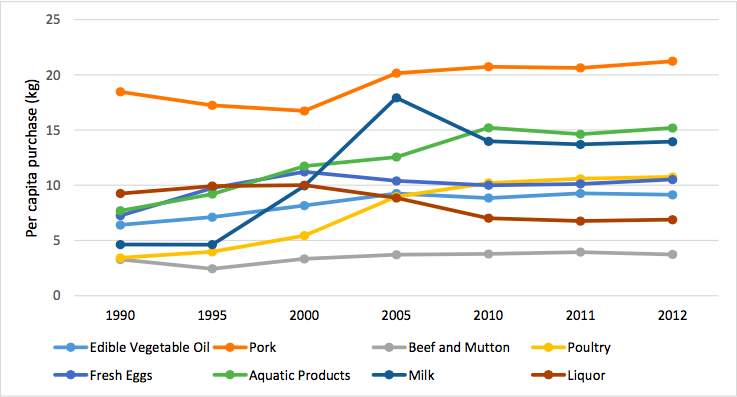

China’s import quantity of Food and Beverage products has remarkably increased. According to statistics from the General Administration of Quality Supervision, Inspection and Quarantine (AQSIQ; 中华人民共和国国家质 量监督检验检疫总局), 35.141 million tonnes (USD 48 billions) of import food was controlled in China, representing year-on-year growth of 3.3% (value) and 7.3% in terms of amount. As shown in the chart below, in 2005 the value of imported food trade reached over EUR 8.7 billion (USD 10 billion) and it is expected to quadruple by 2014 reaching a record value up to EUR 42.0 billion (USD 48 billion).

Chart 2:

Figure 5.2 China’s Imported Food Trade Value 2005-2014 (in USD 100 million)

Figure 5.2 China’s Imported Food Trade Value 2005-2014 (in USD 100 million)

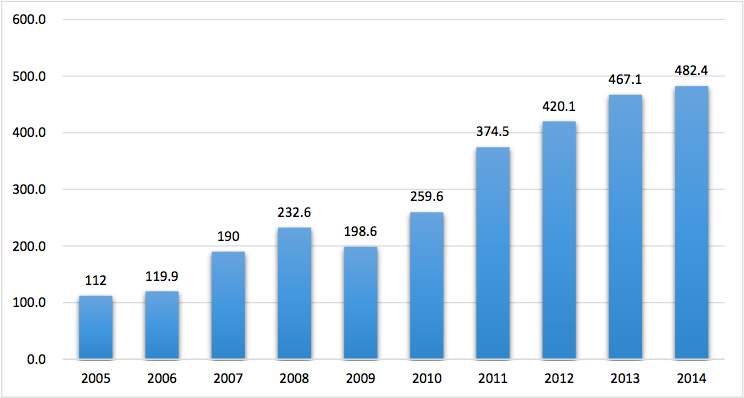

In recent years, China has increasingly outsourced its food from abroad. In 2014, China’s imported food products came from 192 different countries and regions. According to (XXXX), in 2014 the top 10 importing sources in terms of import value were:

- The European Union

- The Association of South-East Asian Nations (ASEAN)

- New Zealand

- United States

- Australia

- Brazil

- Canada

- Russia

- Argentina

- South Korea

These areas accounted for over 82% of China’s imported food trade. The EU was the largest importer, with F&B imports to China worth EUR 8.2 billion (USD 9.4 billion).

Figure 3.3 China’s Imported Food Trade Value 2005-2014 (in USD 100 million)

More specifically, in 2014, the first 5 European countries that exported to China (beverages, prepared foodstuffs, spirits, tobacco, and vinegar – Hs codes 16 to 24) were France, The Netherlands, Germany, Ireland, and Italy. The total amount was € 1,237 million, € 756 million, € 441 million, € 316 million and € 298 million, respectively (China MOFCOM).

3.3.5 Import Drivers

Along with the previously mentioned expendable income increase for Chinese households, in the F&B sector there are other key growth factors including the following categories:

One relevant scandal in China remains the one concerned with food safety; bad events such as the ‘cooking oil scandal’ (where ‘gutter waste’ was sold as ‘cooking oil’) are still fresh in consumers’ memories. In 2015, bacteria responsible of botulism in 38 tonnes of whey, which is used to obtain baby mixture, was discovered by Fonterra (New Zealand’s largest dairy products producer). New Zealand’s dairy exports go to china for almost one-fifth of them. As claimed by local Chinese authorities, the scandal affected in China about 420 tonnes of baby milk.

Previous scandals concerning with locally produced milk powder brands allowed foreign companies to acquire market share. Foreign producers control about 80 % of the milk powder market in the largest cities of China.

These scandals have affected confidence and trust in food production standards and processes. According to Reuters, on April 25th 2015, The Standing Committee of China’s National People’s Congress, China’s top legislative body voted to reform its food safety law to include more rigid punishments for those that violate the standards for milk formulas destined to infants. Consumers of imported food in China are generally upper- or middle-income locals and expatriates. These consumers can afford higher prices for food and are willing to do so due to the increasing concerns about food safety and health. In such context, imported Western-style good have a recognized reputation for being high quality and for being nutritious and safe.

A 2012 survey found that 41% of Chinese people were deeply concerned about food safety, compared to just 12% four years earlier. A 2014 survey of 4,258 Chinese people from 59 cities showed that 47.8% of participants were unsatisfied with food safety; a similar poll in 2012 showed only 18.8% dissatisfaction (EUSMES, 2015)

These food incidents have had a considerable impact on consumers’ purchasing decisions. In the same Pew survey, more than 70% of consumers admitted that they would consider to avoid buying a brand if it were involved in an incident. Having said this, not only domestic companies have come under fire from regulators over safety concerns. Indeed, regulators often attack foreign firms with short time of advice.

The retail market value for China’s full-service restaurants (excluding fast food restaurants) reached EUR 265 billion (CNY 1,865 billion) in 2014; Mintel predicts that by 2019, the retail market value will reach EUR 390 billion (CNY 2,724 billion). Despite marked growth, competition among players remains strong, and the choice of cuisine remains limited.

In China, imported F&B products are generally consumed in cafés, bars, hotels and restaurants in urban settings, and Chinese consumers, when they dine out, are more often choosing ‘Western food’. Many Western-style restaurants that were originally chosen by expatriates now have mostly Chinese people as client, and generic Western-style groups of restaurants are widespread. In this new scenery many family celebrations and social occasions take place in Western restaurants, increasing traffic in these venues.

One of Chinese online retailer is Taobao13, a market leader in the e-commerce sector, which brings the daily routine of shopping online up to 65 % of Chinese Consumers. Only in 2014, Taobao’s total sales reached €170 billion, with Tmall achieving € 73 billion in annual sales the same year. According to the annual financial report compiled by the Alibaba Group, year-on-year sales in the e-commerce sector reached 394% in 2014. Taobao, Tmall, JD15 and Yihaodian were the largest F&B importers to China in 2014 – 2015 (LEK, 2016).

Online shopping in China is not only a platform from which buy things that consumers want or need but it is also about sharing information, keeping up with trends and communicating. Chinese people are the world’s spread community of consumers of online products, with one in seven consumers buying online every day.

The growth of interests in e-commerce is not necessarily bad for brick-and-mortar stores since consumers seek more than just ‘products’ when they shop; instead, they expect and want a more often personalised and integrated experience.

Imported food and beverages remain a status symbol in China, perceived as having higher value than Chinese goods. These products are often used for display purposes rather than for consumption. As a result, branding and packaging are extremely important.

Gift giving remains an important custom in the Chinese culture, despite recent spending cuts imposed for government officials. Wine industry sales are dominated by gift-giving purchases. Such wines are usually presented individually in elegant wooden boxes and are often accompanied by complementary gifts, such as a pair of appropriate wine glasses.

3.3.6 Chinese Consumers Preferences

In China, improved standards of living change significantly food consumption patterns. Lots of consumers are revealed to an always bigger diversity of consumer products, both when travelling abroad and locally. Chinese consumers are increasingly critic, and many of the following qualities are more often sought when making purchases:

- Confidence in food safety and ingredients’ integrity

- High quality

- Excellent nutritional value

- Better lifestyle through a variety of food and beverages

- Modern packaging

- Freshness

- Convenience

Confidence in ingredients’ integrity, food safety, and high quality products are the key reasons purchased by Chinese consumers for imported F&B products. As a result, many mainland consumers choose pollution-free, safe and quality food items. Furthermore, with increased spending power a higher request for F&B products imported from overseas is shown by consumers. These reasons far outweigh other factors, such as better nutritional value, better lifestyle through more variety, modern packaging, freshness and convenience.

3.4 Demand for EU F&B in China

“China’s potential as a food-importing country is vast, and it will continue to grow as the Chinese middle-income market becomes larger. There are more people who want to try more different foods,” said Brendan Jennings, general manager of China International Exhibition Ltd (EUSMES, 2015) organiser of food and wine events in Asia. Lands of China are limited in arability, only 11% compared to 17% in Ireland, 24% in Italy and 25% in Spain.

China has also to face with a crisis of water scarcity; therefore, an issue in north China, with deficiency relating to the economic development of the country.

Although a lot of steps are taken by the government to redirect water from areas of rich water resources to northern China, this require lots of time and massive engineering. Water pollution is also another key concern in North China and shortages have increased in correlation with the country’s economic development. China host 1.3 billion people; the country is obliged to import F&B products because of its inability to produce enough to feed its population. The expansion of the middle class dues to the growing of China’s market for imported food products. The following statistics show that the size of China’s beverage market and packaged food rised from EUR 127 billion in 2008 to EUR 224 billion in 2012. It is expected that China’s F&B import market will increase more than 15% annually, and its projected valued by 2018 will be EUR 66 billion.25

In the first quarter of 2015, F&B exports from Spain to China rose 48% and were worth over EUR 160 million; olive oil exports from Spain to China increased by 53% in the same period. In 2014, Spanish wine and food exports to China were worth EUR 500 million, a year-on-year increase of 18%. Exports of pork from Spain to China continued to grow in 2014 and, in the first quarter of 2015, exports increased by 53% year-on-year.

Exports of agricultural goods from Germany to China reached over EUR 900 million in 2013, a year- on-year increase of 37%. In 2014, nearly half of all beer imported to China came from Germany.

In 2014, French dairy products exports to China (milk powder not included) grew by 11% to over EUR 215 million (EUSMES, 2015)

3.5 Retail Channels

The following section outlines popular retail channels that have registered a considerable development in China. The retail system benefits from a strong technical development and application, as well as a consumer base which is flexible and responsive to renewals in the market.

Hotel and Restaurant Industry Wholesalers

An important channel for imported foods is hold by the high-end hotel and restaurant industry. Metro, which selects small- and medium-sized restaurants, has from any key international retailer the widest choice of imported products. In 2012, about 10% of its total sales revenue came from imported products. According to Walmart’s website in May 2015, the value of its import sales saw a year-on-year increase of 200% from 2014.

Retailers and wholesalers pay close attention to provide chain development, and a prominent discussion topic is about cold management. Packaged foods are mainly targeted by Yihaodian; in 2014, news reports revealed that the major challenge is the cold fresh delivery, and Yihaodian expects that the recent addition of fresh fruit delivery services, which is launched in Shanghai (still on a trial basis), will increase sales revenues. After the trial, cold delivery services (transporting fresh foods) by Yihaodian will expand to northern and southern China.

Online Shopping

From January to March 2015, China’s national online retail sales totalled EUR 110 billion – an increase of 41.3% year-on-year – of which online retail sales of goods, specifically, reached EUR 90 billion, accounting for 8.9% of China’s total retail sales of consumer goods. Of China’s total online retail sales, e-sales of food increased by 51.0% in 2014 (EUSMES, 2015). Chinese diversity growth of distribution channels (including e-sales) helps to erase geographical barriers from the development of China’s imported industry of F&B. Due to infrastructure and transportation issues, big cities such as Shanghai and Beijing are historically one of the most consumers of China’s imported products of F&B. This situation is changing, however: Many middle- and small-sized cities significantly distant from the coast are now much more connected providing lots of chances for imported food sellers.

Since 2012, individual consumers add e-commerce to their daily shopping routine. China’s development of e-commerce continues rapidly and is predicted to amount almost 18% of total retail sales in 2018, up from 8% in 2013.

Taobao, Tmall and Yihaodian are the principal players within the e-commerce market. Moreover, other platforms are being developed, including those specialising in products. For instance, organic high-quality food is sold by TooFarm.

Hypermarkets

International hypermarkets such as Carrefour and Metro are important sales centers for imported food products in China. Given their long experience in the Chinese market, these international retailers are familiar with imported products and have superior management and organisational skills.

International hypermarket retailers generally have high awareness of imported brands and products, and they can recognise the importance of offering new products to the market. In the past, however, hypermarkets in China have preferred distributors and don’t like working with unfamiliar companies unless they manage large numbers of products, strong market support and other incentives.

Another way to attract foreign residents in specific areas consists in speciality supermarkets boutiques. In these stores, 50-80% is approximately the proportion on shelves of imported products. Some specialty products and high-end entered first the Chinese market through these specific types of outlets and then move on to larger venues such as hypermarkets. Import/distribution operations are also included in these companies and they can assist exporters with issues such as product registration and labelling. The teams of import/distribution can source products immediately from foreign suppliers.

Supermarkets

Local players dominate the supermarket sector, which is consequently fragmented; companies can be non-existent in one region and successful in another. China Resources Vanguard, Beijing Hualian Group Lianhua (BHG), Yonghui and Park’n’shop are some of most well known supermarkets in China. Imported food is relatively rare in most community supermarkets. Their consumer base of price-sensitive working- class shoppers are less inclined to try new products than are customers who frequent upscale speciality supermarkets, hypermarkets and boutiques.

Standard products which are already widely available and do well in this sector are imported products such as pasta, pasta sauces, dairy products, spreads and jams. Most of the imported food stores are controlled by local companies and rely on wholesale markets and local manufacturers or distributors. Very rarely they buy or import directly from importers.

Convenience Stores

The penetration of imported foods among convenience store chains has lead to be relatively low. However, this is gradually changing, and now it is quite easy to find imported alcoholic beverages – including, beer, wine and whisky – on sale in convenience stores. Well-known convenience stores including Family Mart,7-Eleven and Lawson; the opening of new stores has been speeded up by these chains due to expand their market share in China. Local giant retail groups, such as Hualian and CR Vanguard, have established sales networks through much more available stores. Moreover, convenience stores start to have been used by large online retailers – Tencent, Alibaba, JD.com and Amazon.cn –as part of their marketing strategy. These stores are becoming progressively important distribution channels, not only in first-tier cities but also in cities in inland areas.

Convenience stores typically require small or single-serve packaging and regular restocking due to limited shelf and storage space. However, foreign players in this sector (such as 7-Eleven and Family-Mart) are introducing a progressive variety of imported food products in their retail outlets.

Total sales revenues for convenience stores reached EUR 387 million in 2012. However, in a survey of 25 cities in 2013, convenience store sales had grown 19.5%, higher than that of other traditional brick-and-mortar outlets. In 2012, 64.7% of convenience stores’ revenue was generated from selling food, 34.6% from non-food items and less than 1% was derived from other value-added services (LEK, 2016).

In a report covering the development of China’s convenience stores (2013-2014) published by the China Chain Store & Franchise Association (CCFA; 中国连锁经营协会), 64.7% of convenience stores’ revenue was from selling food, with fast food accounting for 7.0%. Non-food items totalled 34.5%, and 0.8% came from value-added services (EUSMES, 2015).

Smaller, privately owned convenience stores often carry imported packaged snacks, wine and confectionery. These stores tend to have better integrated distribution systems and are more likely to see the value of high-margin imports.

3.6 Barriers to Entry

3.6.1 Legal and Regulatory Barriers

The Chinese F&B market is convincing due to the market’s size, but many opportunities still remain difficult to exploit for European SMEs. Various reasons influence this event, including high entry obstacles related to the regulatory and legal environment, the characteristics of the operating environment and the market for both exports and investments entering China. Due to recent food safety scandals in the market, China has put new regulations in place regarding particular kind of industries, such as dairy.

Since joining the World Trade Organisation (WTO) in 2001, Chinese tariffs has been reduced on a wide quantity of imported products, but phytosanitary and sanitary restrictions (and, to some extent, labelling) continue to restrict access to the market.

Administration of regulations is often random, creating quite often confusion for exporters.

New Food Safety Law

The new Food Safety Law regulates: Trading and production of food and food additives

Packing materials, detergents, vessels and disinfectants for food and equipment useful in food production Food additives and food-related products used by food traders and producers

Safety management of food, food-related products and food additives All imported food products, subject to the national food safety standards in China.

Standards & Certifications

When entering China there are high market-entry costs – both concerning fees involved in mandatory certification and the resources required. Labelling, product registration and product expiry dates are surprisingly high concerns in this area. To enter the Chinese retail market, a hygiene certificate from the local government where the product will be sold food has to be received by products. There are also problems about inconsistencies in the explanation of regulations among officials at various entry locations and whether they loosely or more strictly apply fines/penalties. Regulations change with some frequency and without warning. Accommodating and adjusting these regulations can be time-consuming and expensive.

Registration of Food & Drinks Exporters

Since October 1st 2012, beverage and food exporters to China have been required to register through AQSIQ. They can achieve registration also through import companies. Both options can be accessed through http://ire.eciq.cn. In this website is included guidance in both Chinese and English, enabling foreign suppliers to register themselves. It is important to note that information about Chinese importers must be filled out in Chinese before passing the process of registration; therefore, companies are advised to work strictly close with their importers or agents to complete this process. AQSIQ recently formulated and announced the “imported food poor records management implementation details” which are effective as of 1st July 2014.

3.6.2. Market Barriers

Distribution

The F&B market remains somewhat decentralised in China and is characterised by competition and free growth. There are few large distributors that are dedicated to imported beverages and food. Since there are few importers or distributors with more than 1,000 imported food and beverage products, the varieties of products are limited.

Most Chinese distributors in this market do not put a lot of emphasis on brand development and instead tend to be primarily interested in wholesaling. They tend to be conservative in introducing new products. They are largely interested in products that are already available in the market but are sold through sub-distributors or “grey” (unofficial) channels. Exporters with a limited product range need to simultaneously work both ends of the supply chain, identifying retailers interested in the product and distributors who can work with the retailers.

Due to domestic food scandals and growing disposable income, a key driver in stimulating the boom of the imported Food & Beverage industry is the remarkable growth in online shopping. Since 2012, the e-commerce market has expanded dramatically; as a result the closure of several retail stores due to the consisting growing preference of consumers purchasing online.

According to Ebrun, a portal for e-commerce news in China, companies should be aware of the following topics when considering e-commerce channels as a distribution way in China:

E-consumption habits are different from Traditional consumption habits, especially for snack foods.

3.7 Opportunities for European firms: Niche Market

Given the high quality standards that firms in the European Union are asked to follow, their productions represent a unique mix of qualities that greatly match with the increasing needs recently required by Chinese consumers.

An example of product that have been largely supplied by European compemnies was milk.

Indeed, in 2014 China imported 296,321 tonnes of milk, registering a year-on-year increase of 55.9%. Milk imported to China is typically ultra-heat treated (UHT) milk, and sales channels have expanded to second- and third-tier cities. Imports are expected to increase further in 2015.

In 2014, China consumed 54 billion litres of beer, of which over 335 million litres were imported, registering a year-on- year increase of 85.4%.

From 2012 to 2014 the import of beer increased by 426%. It is expected that the demand for imported beer will continuously improve during the period 2015- 2018.

China’s importation, production and consumption of wine, in 2014, gain 383 million litres, 1.6 billion litres and 1.58 billion litres.

The demand for wine in China is estimated to grow increasingly up by 10% annually in the coming years. Market penetration of products will spread from inland areas to coastal areas.

Chapter 4 - THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

In the previous section of the study, the major determinants of the firm performance have been discussed to give the reader a general idea of what the literature has produced so far on the theme of liability of newness and firm performance. The aim of this chapter is to develop a theoretical framework that can support the statistical interaction between dependent and independent variable. The classification of the factors influencing the firm performance are generally divided into internal and external determinants.

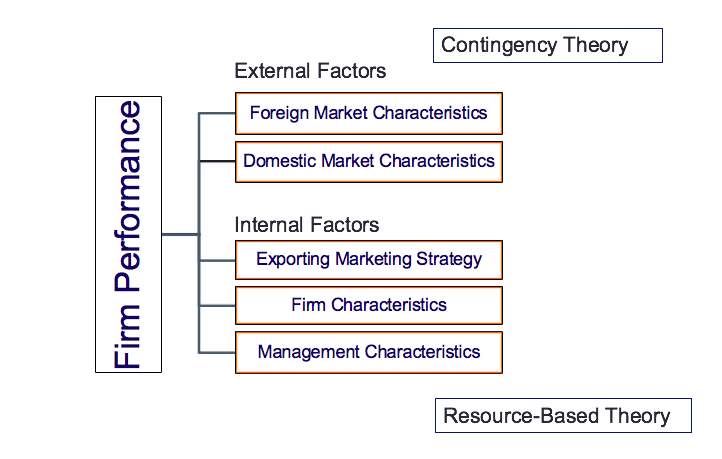

Following the findings provided many researchers, including Zou and Stan (1998) and Sousa et al. (2008), the theoretical framework used in this research combines two different paradigms that explain the two groups of variables. In particular, the resource-based view (RBV) is used to explain the internal factors influencing the performance, whilst the contingency theory supports the influence of external factors in the firm performance.

The relationship between the liability stream of research and the resource based view of the firm has been defined robust by many researchers (Abetacoal et al., 2012; Aspelund et al., 2005), however they maintained that the exploring of this relationship needs appropriate consolidation in the future. The Contingency theory has been employed to capture all those determinants that the resourced based paradigm cannot include. For example, the GDP and the variables related to the economic policies and legal system cannot be satisfactory explained uniquely by this theory. This aspect is particularly important in sectors like the food and beverage one where regulation and food standards play a remarkably big role in the firm strategy and consequent actions.

In the following part, the two theories will be discussed more in detail.

4.1 Resource Based Theory

Generally speaking, the resource-based theory states that the sustained competitive advantages developed by a firm are a consequence of the unique set of resources of the firm (Barney, 1991; Conner and Prahalad, 1996). Penrose (1959) first provided the basis for this theory defining a firm as “a collection of physical and human resources” (P.9), and highlighting the heterogeneity of these resources among firms. A resource can be defined as anything that can be thought as a strength or a weakness (Wernerfelt, 1984) and researchers have classified them in different ways in their studies, leaving a quite high degree of unclearness. For example, Chatterjee and Wernerfelt (1991) classified them in three main categories: physical, intangible and financial resources. Also Dhanaraj and Beamish (2003), referring to the export strategy, divided the resources in three groups: managerial or organizational resources, entrepreneurial resources, and technological resources.

The RBV implies also the knowledge-based view that states that privately held knowledge, competencies or capabilities are a basic source of advantage in the case of competition. From this concept, the RBV addresses performance differences between firms using asymmetries in knowledge (Conner and Prahalad, 1996). In other words, the RBV addresses how superior performance can be achieved relative to other firms in the same market and states that superior performance results from acquiring and exploiting unique resources of the firm (Dhanaraj and Beamish, 2003); decisions that are consequences of the set of knowledge and competencies held by the firm.

Linking the theory to this study, the RBV sustains that the performance of a firm is based on firm’s level activities and characteristics such as competences, experience and size (Sousa et al., 2008).

4.2 The contingency paradigm

In contrast with the RBV, the contingency theory asserts that the environment has also an impact on the export strategy and performance, and this gives a theoretically support to the external factors identified in the literature review. The contingency theory is defined as a mid-range theory because it conceptually falls between two ‘extreme’ theories. The first one maintains that universal principles of organization and management exist and the other one defends that each organization is unique, thus each situation must be analysed separately (Robertson and Chetty, 2000). Between these two theories, the contingency approach emphasizes the importance of the situational influences on the management of organizations, denying the existence of a best way to manage (Zeithaml et al., 1988) and the impossibility of strategy standardization.

Applying this concept to firm performance, according to Robertson and Chetty (2000), the firm success depends on the context in which the firm operates. Therefore, the firm activity depends on the level of ‘fit’ between the entry-market strategy adopted by the firm and the external environment.

Thus, in this study it is proposed a theoretical framework that combines the two theories, which are graphically represented in Fig. 3.1. In particular, the resource based view theoretically support the correlation between internal factors and the firm performance, whilst contingency theory provides the theoretical base for the relationship between external factors and the firm performance.

Figure 4.1 Theoretical Framework

4.3 Hypothesis

Having extensively analysed the literature review, the peculiarities of the Chinese food sector, and the theoretical framework, in this section the hypothesis will be formulated. In the table the supporting literature review is also presented.

Table 4.1 Hypothesis

| Hypothesis | Literature |

|

H1. Firm size will have a significant and positive effect on firm performance |

Hannan and Freeman (1984); Freeman, Carroll and Hannan (1983); Baum and Oliver (1996); Sutton (1997); Agarwal (2002) |

|

H2. Firm entity type: establishing a JV with a Chinese partner will positively effect on firm performance

|

Lu, Y. (1998); Child, J., & Yan, Y. (2003) |

|

H3. Territorial governance |

Tian (2004) |

|

H4. Firm experience in the Food Market is significantly positively correlated to firm performance |

Katsikeas and Morgan (1994) |

|

H5. Entering the market in an early stage positively influences firm performance |

Isobe et al. (2000) |

Chapter 5 - EMPIRICAL MODELS AND RESULTS

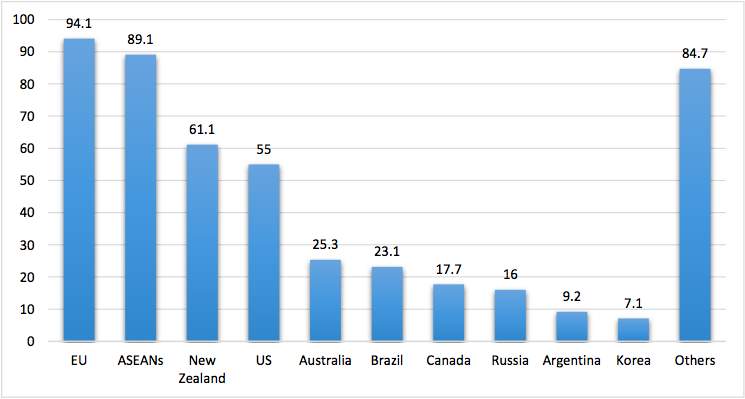

In the following chapter the data analysis part of the study is presented along with the produced results. In order to assess the effect of the determinants identified in the literature review, statistical analysis will develop in the following chapter.

The dependent variable Y will measure the performance of firms in the Chinese food market, and the independent variables will include determinants that will potentially have an effect on the dependent variable.

5.1 Econometric Model Specification

In the present study a Multiple Linear Regression Model has been adopted to assess the factors influencing the firm performance. A reduced version of the model can be specified as follows:

(1)

yi= β0 +β1xi + μi

where:

yi

= dependent variable for firm performance

β0

= intercept

β1

= vector of the coefficient estimates

μi

= error term.

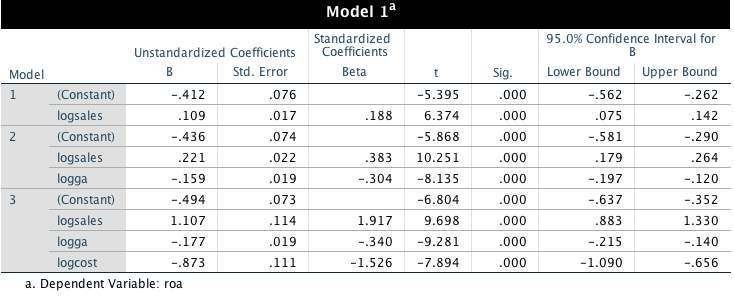

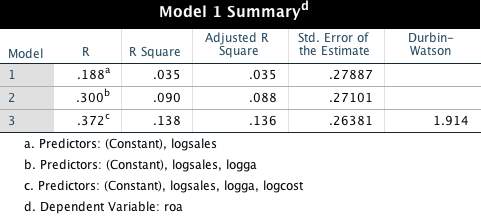

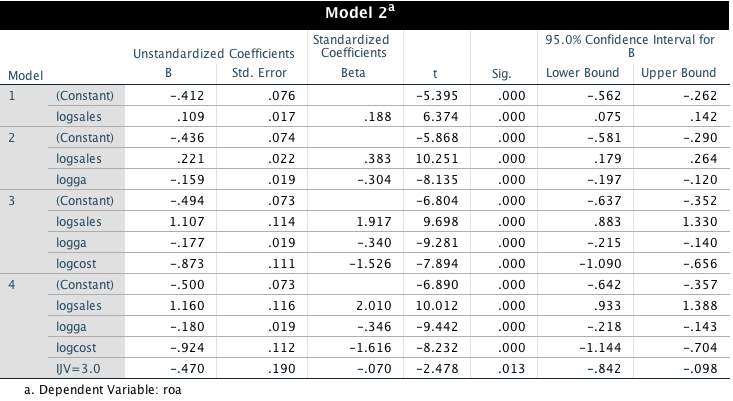

In this kind of analysis, if the probability of the test statistic or one more extreme having occurred by chance alone is very low (usually p

Furthermore, the coefficient of determination, or regression coefficient, enables you to assess the strength of relationship between a numerical dependent variable and one or more numerical independent variables.

The coefficient of determination (represented by R squared) can take on any value between 0 and +1. It measures the proportion of the variation in a dependent variable (roa) that can be explained statistically by the independent variable (firm size, logcost, etc).

The R2 is one of the measures taken into consideration when assessing the goodness of the model. If 50 per cent of the variation can be explained, the coefficient of determination will be 0.5, and if none of the variation can be explained, the coefficient will be 0. In cases like this study, cross-sectional, R2 is expected to be lower compared to regression on longitudinal data.

5.2 Data