Impact of Modular Construction Methods on the UK Residential Market

Info: 6594 words (26 pages) Dissertation

Published: 17th Nov 2021

Tagged: ConstructionHousing

Introduction

Background

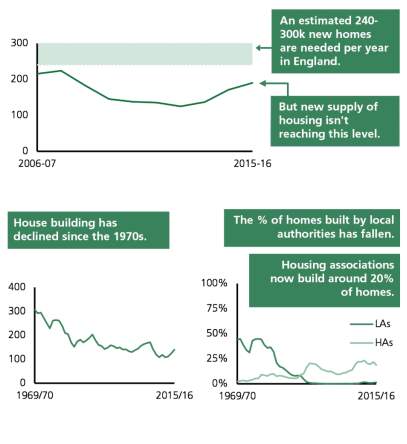

It is quite that UK Construction sector has failed to deliver the number of homes that is required. The 2015 Government’s Housing White Paper, Fixing our broken housing market was published in February 2017. The paper makes bold remarks that the housing market is one of the greatest barriers to progress in Britain today (Department for Communities and Local Government, 2017). In their house of commons briefing paper (Wilson, et al., 2017) Show that house building has declined since the 19070s as well as the % of homes being delivered by local authorities as well as underperformance to reach the 240,000 to 300,000 new homes that are required in England per year (see Figure 1)

The white paper outlines the Government’s package of reform to increase housing supply and halt the decline in housing affordability.” The Paper identifies the threefold problem of “not enough local authorities planning for the homes they need; housebuilding that is simply too slow; and a construction industry that is too reliant on a small number of big players.” The White Paper focuses on four main areas in order to resovle these;

- Building the right homes in the right places.

- Building them faster.

- Widening the range of builders and construction methods.

- ‘Helping people now’ including investing in new affordable housing and preventing homelessness.

Along with the announcement of the refocusing of funds and the review of regulations which can negatively affect the speed of which homes are built the paper outlines the Government’s plans to ‘encourage modern methods of construction in house building’ as well as ‘promote modular and factory built homes’ (Department for Communities and Local Government, 2017, pp. 16,14) Government intends to utilise offsite technologies and build around 100,000 modular homes across Britain by 2020

The Government’s plan to support such methods of construction have been suggested in the past by UK government reports, including the Egan Report “Rethinking Construction” (1998), produced by the Construction Task Force, discussed the need for performance improvements in the UK construction industry. (Egan, 1998) identified supply chain partnerships, standardisation and off-site production (OSP) as having roles in improving construction processes. The sentiments regarding OSP have also been supported more recently by Industry advisors and experts such as ( (Soetanto, et al., 2006) (Harty, et al., 2006) (Pan, et al., 2006)) who see offsite as one of the key issues of the future. Offsite prefabrication is a process which incorporates prefabrication and pre-assembly. The process involves the design and manufacture of units or modules, usually remote from the work site, and their installation to form the permanent works at the work site. (Gibb, 1999)

The UK construction sector is no stranger to the manufacturing methods of offsite prefabrication. Following the 2nd world war the construction industry was struggling to keep up with demand and there was an evident lack of materials and skilled labour in the economy. prefabricated houses were a major part of the delivery plan to address this housing shortage and Housing (Temporary Accommodation) Act 1944 outlined plans to construct 300,000 homes within 10 years within a budget of £150 million. These were however only ever supposed to be a temporary fix and therefore where made to a low standard both technically and architecturally. Such context helps to explain why there has been limited use of MMC despite its well known benefits (Goodier & Gibb, 2007) as well as the negative percptions that have been drawn from other inadequate performances 1960s-70s social housing and 1980s ‘scares’ about timber-frame construction (Craig et al., 2000; Cook, 2005).

Research Aims and objectives

Aim

Assess the level of impact that modular construction methods will have on the UK residential market.

In order to achieve such an aim, the following objectives must be explored:

- Determine the key factors negatively impacting the UK residential market.

- Establish if there is a demand for housing within London and the South East of England

- Determine the key factors that determine whether developers choose to develop in the traditional way or by using pre-fabricated modules.

- Analyse the likelihood that the rise in modular construction will have a positive effect on the housing market within London and the South East of England

Structure of Dissertation

Chapter 1 provides a brief summary of background understanding on the research subject, which is to decide whether prefabrication can become the future of sustainable housing in the UK and helps to formulate the aims and objectives of this research.

Chapter 2 reviews relevant literature regarding Modern Methods of constructions and the UK residential market in relation to each research objectives. The findings provide the basis for further investigations in this research by highlighting the inconsistencies in the existing literature and identifying gaps in current knowledge as well as being the foundation on which discussion of prefabrication within the UK’s residential housing sector is based.

Literature review

Identifications off different types of MMC

Methods of Construction (MMC) is the term used by the UK Government to describe a number of innovations in housebuilding, most of which are offsite technologies, moving work from the construction site to the factory (Gibb, 1999) such innovations can be further defined as Sub-assemblies and components, Panellised construction, Hybrid, Sub-assemblies and components, Volumetric modular construction (Kempton & Syms, 2009) further definitions and examples of such terms have been provided by (Gibb & Isack, 2003) below

- component manufacture and subassembly, e.g. factory manufactured components such as bricks, tiles door furniture and windows;

- non-volumetric pre-assembly, e.g. structural frames, cladding, wall panels, bridge deck units, M&E services, units do not create usable space;

- volumetric pre-assembly, e.g. plant rooms, toilet pods, units create usable space; and

- modular building, e.g. pre- assembled units which form the structure of the building and create usable space.

Drivers and barriers for use of MMC

Methodology

Closed-ended online questionnaire survey

Limits Closed-ended online questionnaire survey

Homogeneous selective sampling

Limits of homogeneous selective sampling

A limitation of homogeneous sampling is that the research findings cannot be generalised for the entire sector, since the sample is not representative of the sector (Saunders et al., 2012). The respondents were however chosen specifically as they recognize some of the companies in in their field and therefore such findings can provide a essential into the views and perceptions of some of the sector’s most influential contributors

Data Analysis

It is clear that the housing market is underperforming – under supply of houses MMC – volumetric continues to be quoted across government and industry as a potential catalyst in meeting these challenges.

But if it is so important, why does data show that the offsite market only contributes 7% to UK construction GDP

Wells [1979] identifies advantages that include: (1) acquiring a single responsible source, (2) testing, (3) training operators, (4) controlling the schedule, and (5) reducing cost.

MMC is the fabrication of house parts off-site in a factory with panels and modules being the two main products (CIEF 2003)

Pre- assembled volumetric modular buildings are defined as including off-site manufactured fully assembled 3-dimensional units, or modules, which are either used as ‘standalone’ units or are combined, by linking on- site, to form a complex of units, or alternatively to form a modular building, consisting of several linked and stacked units or modules with appropriate cladding features. Volumetric modules may be stacked several storeys high dependent upon module construction and the need for additional structural elements, etc.

However, the focus of this section of the report is only on volumetric modules used for constructing permanent and long-term temporary buildings (15 years). Excluded from our definition are: accommodation units typically used at construction sites, hire units, refurbished/second hand modules, garage batteries, portable toilets, anti-vandal units, jackleg cabins, agricultural buildings, plant & pump rooms.

How the Government are backing their solution

Government interest in offsite manufacturing also appears to be increasing. In 2015, the Department for Business Innovation and Skills awarded a £22.1m grant to a consortium led by Laing O’Rourke to develop advanced methods for the manufacture of homes, buildings and infrastructure. It is part of the four-year, £104m Advanced Shows that there is and underperformance of the housing sector to produce … (Chris & Gibb, 2005) Cite this as well as pressure by Government and industry to improve the performance of the UK construction industry, particularly its efficiency, quality, value and safety as an explanation for the recent interest in offsite in the UK.

For this study, offsite is defined as the manufacture and pre-assembly of components, elements or modules before installation into their final location (Chris & Gibb, 2005)

Analysis of MMC vs traditional construction

Addressing traditional construction skills shortages

in addressing traditional construction skills shortages (61% (Pan, et al., 2006)

Lesser drivers

Reducing health and safety risks, sustainability issues, government promotion, complying with building regulations, restricted site specifics were also highlighted, but less frequently (less than 15%).

Time and Quality drivers

The biggest advantage of offsite compared with traditional construction is thought to be the decreased construction time on site.

The biggest advantage of offsite compared with traditional construction is thought to be the decreased construction time on site, together with increased quality, a more consistent product and reduced snagging and defects Gibb and Isack (2003), Goodier and Gibb (2004), Venables et al. (2004) and Parry et al. (2003)

A 2011 study by McGraw Hill Construction conducted among architects, engineers, contractors, and building owners supports the arguments that speed to completion, quality, and safety can be increased with modular construction, while overall costs, material waste, and the impact on the environment can be reduced (Harvey, et al., 2011)

This was stated by about 90% of respondents, including clients, designers and contractors (Table 4). Unsurprisingly, this factor is of particular benefit to contractors, with 69% ranking this as their number 1 advantage.

Increased quality also ranked highly by all respondents. A more consistent product and reduced snagging and defects were also seen as advantages by the majority of respondents, although more so by the clients/designers than by contractors. Of the remaining possible advantages, a higher percentage of the client and designer respondents selected each of the possible advantages compared with the contractors who responded. This probably reflects the higher proportion of clients and designers compared with contractors who said that they were aware of the potential advantages of offsite.

ensuring time and cost certainty (54%) (Pan, et al., 2006)

On site time

minimising on-site duration (43%) (Pan, et al., 2006)

Quality

achieving high quality (50%) (Pan, et al., 2006)

Cost

The cost factors have been studies in much detail

The belief that using offsite is more expensive when compared with traditional construction has been put forward by …… Goodier and Gibb (2004) and is often seen as one of the biggest barriers effecting the uptake of such methods

In their study in which they aimed they determine Barriers and opportunities for offsite in the UK (Chris & Gibb, 2005) surveyed 75 UK construction organisations, including clients, designers, contractors and offsite suppliers and manufacturers, their evidence agreed with the belief that using offsite is more expensive when compared with traditional construction is clearly the main barrier to the increased use of offsite in the UK, but also found that a large proportion of the respondents also thought that two of the advantages of using offsite were both a reduced initial cost and a reduced whole life cost.

In a study comparing the costs and benefits of the two main prefabricated homes category: panelised and modular (Lopez & Froese, 2016) showed that the modular construction method is marginally more cost effective than the panelised construction claiming increased quality control. They showed that this was the case due to the reduced number of workers and site hours that must be accounted for once the modules are delivered as the modules are delivered nearer to final completion and require less task to be carried out on site.

Gibb and Isack (2003) were able to show that although off site prefabrication can offer direct cost benefit, the main benefits are from indirect cost savings and non-cost value-adding items found through asking interviewees to rank a list of key benefits, noting both the importance of the benefit and the likelihood of realising the benefit in terms of non-direct cost and Direct cost benefits that (Pan, et al., 2006) aimed to investigate UK housebuilders’ views on the use of offsite Modern Methods of Construction (offsite-MMC) through the use of interviews and a survey of the 100 housebuilders by unit completion.

Results suggest that the traditional drivers of time, cost, quality and productivity are still driving the industry in deciding whether to use offsite technologies. Nearly two thirds of the firms believed that there needs to be an increase in the take-up of such technologies. However, current barriers relate to a perceived higher capital cost, complex interfacing, long lead-in time and delayed planning process.

The study also gives insight into the views held by such companies with, a significant number of these top housebuilders not being satisfied with the performance of offsite-MMC, both within their own organisations (31%) and in the overall industry (47%).

of which 82% satisfied / very satisfied with their own, in-house, traditional construction methods as wells as 59% satisfied / very satisfied with the performance of the overall industry in traditional building (Pan, et al., 2006) also found that their respondents believed there would be more growth in the uptake of off-site techniques being used to produce Kitchen and bathroom modules but did not generally see great potential for complete modular buildings.

Barriers against the use of offsite-MMC

Respondents were asked to choose three most significant barriers from a list derived from previous research. Figure 3 shows the frequency of responses expressed as a percentage of the sample. The significant barriers against the use of offsite-MMC in the industry were considered to be higher capital cost (68%), difficult to achieve economies of scale (43%), complex interfacing between systems (29%), unable to freeze the design early on (29%) and the nature of the UK planning system (25%) (Figure 3). The risk averse culture, attitudinal barriers, fragmented industry structure, manufacturing capacity were suggested, but by a lower percentage of housebuilders (less than 15%). The concerns of mortgage lenders and insurers with non-traditional buildings were also raised by a few respondents.

Recommendations for increasing the take-up of offsite-MMC in the industry

The responses revealed that the slow process of obtaining planning permission and changing building regulations are inhibiting the use of offsite-MMC. It was claimed that many of the potential benefits from the use of offsite-MMC were not realised due to the delayed planning process. Planning needs to be more flexible and changing building regulations must be acknowledged. A significant number of respondents suggested that the government should subsidise the use of offsite-MMC to make them cost effective.

Increasing demand for off site

Nearly three quarters of the suppliers surveyed thought that take-up of offsite by industry was increasing in their sector, and only one respondent thought that it definitely was not. This agrees with other reports, which predict growth of 9.7% per annum (by value) by 2010 [4]. (Chris & Gibb, 2005)

Housing Crisis

Cost and affordability

The cost and affordability factor of housing is key and must be considered in order to explain the housing crisis. Cost is an issue for both purchasing private accommodation and renting, with house prices now rising to be six times more than the average income (Helena Bengtsson, 2015)

This gap in income and house prices has been attributed as the result of the markets lack of response to the growing demand (Griffith, 2011) (Barker, 2004) this is however a generalisation of economics and a closer look reveals that house prices have consistently risen over the previous decades with the exception of a few occasions such as during the time of the banking crisis (English Housing Survey , 2015) whilst the sum of wages has not seen the same growth (Shapely, 2010). This is most prevalent in London where average house price (£300,000) is 12.2 times more the average salary (£24,600) this is a large jump from 1995 when the average house price in London was £83,000 which was 4.4 times higher than the average income of £19,000 (Helena Bengtsson, 2015). (Shelter, n.d.) have also stated that had wages had risen at similar rates to house prices over the years that the average wage would be £29,000 higher than they currently are.

These gaps between income and house prices have made it harder for people to purchase property and can explain the rise in the private rented sector (Beckett, 2014), which saw an increase with the number of rented accommodations doubling between 2003 and 2015 to 898,000 (Morley, 2016). This unachievable price of purchasing a home has had particular impact on become a deterrent for young people and first-time buyers with the private rented sector seeing an increase of people aged 25-34 from 24% 2005-2006 to 46% by 2015-2016. As well as a decrease in the number of this age group buying with a mortgage from 53% to 35% (Department for Communities and Local Government, 2017) over the same period. The effects of these figures have been highlighted by (Shapely, 2010) and (Pettinger, 2011) and suggest that the renting can lead to fear of increasing rents and eviction, these fears can lead to a feeling of less financial security and reduce consumer spending which then have negative effects on the wider economy.

Regulatory process

Planning consent

There is a commonly held belief that the housing crisis is negatively affected by the regulatory process that is in place and the belief that such process leads to reduction in supplies and increases in cost with Tom Castella stating that it is “still far too slow, bureaucratic and expensive” (Castella, 2015). (Hilber & Vermeulen, 2012) were able to show the effects that stringent regulatory constraints have on houses prices. According to their baseline estimate, house prices in England would have risen by about 100 percent less, in real terms, from 1974 to 2008 (from £79k to £147k instead of to £2260 if all regulatory constraints were removed which is 35 percent lower (£147k instead of £226k) in 2008 absent of regulatory constraints. They were also able to show that if the south east which planning regulations are notoriously some of the strictest across the country (Michael White, 2003) had regulatory restrictiveness more similar to that of the North East, house prices in the South East would have been roughly 25 percent lower in 2008.

Credence to Castella’s claim has also been provided by (Malpezzi & Mayo, 1997) showing that “countries with more stringent regulatory environments have less elastic supply of housing”, through their study of regulations on market prices that compared the U.S, Thailand and Korea. More recently (Ball, et al., 2009) showed that by (Malpezzi & Mayo, 1997) views apply to the UK and claimed the planning system “may be a major barrier to improving housing supply elasticities” following an in depth look in to permissions within 11 local authorities surrounding London over a single annual term. In another study carried out by (Ball, 2009) he comments on the current structure of the planning system and places the responsibility of the opportunity cots that are forgone in order to respond to “false” applications that developers have been found to put forward to gain better understanding of the planner’s and general public’s actual wants and requirements to increase their chances of success when re-applying on the stringent nature of the planning process suggesting that a more relaxed view could lead to savings in such areas.

Green Belt

The current regulations also serve in restricting the amount of land which is available to be built on. Shelter has shown the effect of this and highlight the cost of land now attributes to 70% of the cost of a new build which is a 25% increase since 1950 (Wiles, 2013). Such regulation is that off the green belt (the zone of land surrounding a city where building development is severely restricted (Amati & Yokohari, 2006)) introduced in 1955, when the government set out policy asking for local authorities to consider protecting any land acquired around their towns and cities “by the formal designation of clearly-defined green belts”.

The metropolitan green belt (surrounding London) is extremely vast with Greater London holding 35,257 hectares whilst another 75,000 hectares being located within the M25 (Wiles, 2014) and has been criticised for its role in the housing crisis for its action of forbidding development and is linked to a chronic shortage of housing in the South–East, one of the areas with the highest demand for housing in the UK as well as one of Europe’s most economically buoyant areas (Barker, 2004). The presence of this greenbelt has and the increasing land prices associated have also lead to the formation of the ‘commuter belt’ that rings London, going out beyond the South-East region into Northamptonshire, Wiltshire, Norfolk, Cambridgeshire and Hampshire (Titheridge, 2006), where developers and residents have built and live but still commute back to the city for work, which as well as the stress, boredom and social isolation (Roxby, 2014) associated with these longer commutes theirs is also the negative effect on the carbon emissions.

There have been numerous calls for the reformations of the green belt as well as development on this land such as those made by Kate Barker and the Adam smith institute. In 2006 Kate Barker a member of Monetary Policy Committee was commissioned by the government to conduct an independent Review of Land Use and Planning. In her review Barker called on local and regional authorities to conduct an extensive review of green belt boundaries and encouraged the government to change its planning policies to allow more homes to be built on green field sites citing that the land shortage is not allowing sufficient quantities of new homes to be built to meet the demand (Barker, 2006). Adam Smith Institute cite factors such as the increased pollution caused by the longer commutes associated with the commuter belt and have also shown that that freeing up 3.7% of London’s green belt could free up enough land to build 1 million homes within walking distance of a train station. (Papworth, 2015).

Recently the Government has made it clear both in their manifesto and the recently published white paper Fixing our broken housing market that they are committed to protecting the green belt and state they want to ‘retain a high bar to ensure the Green Belt remains protected’ And making it clear that ‘authorities should amend Green Belt boundaries only when they can demonstrate that they have examined fully all other reasonable options (Department for Communities and Local Government, 2017, p. 28). This position shows that they are not ruling out developing on green belt land but will however look to other options first, as is also shown in the white paper through their prioritisation of brownfield development. Minister Gavin Barwell recently confirmed the introduction of Brown field register that requires Local authorities across the country produce and maintain up-to-date, publicly available registers of brownfield sites available for housing locally in order to allow housebuilder to easily identify suitable brownfield site quickly in order to unlock land for thousands of new homes. This announcement also came with the promise that the home builders fund will be used to support these developments with a further £1.2 billion provided to unlock at least 30,000 Starter Homes on brownfield land (Department for Communities and Local Government, 2017). Minister Gavin Barwell recently confirmed the introduction of a Brown field register that requires Local authorities across the country produce and maintain up-to-date, publicly available registers of brownfield sites available for housing locally in order to allow housebuilder to easily identify suitable brownfield site quickly in order to unlock land for thousands of new homes. This announcement also came with the promise that the £3 billion home builders fund will be used to support these developments as well as a further £1.2 billion provided to unlock at least 30,000 Starter Homes on brownfield land (Department for Communities and Local Government, 2017).

These are not however new methods and have been suggested in the past with (Barker, 2004) who suggesting “derelict and contaminated land” should be brought back into use as a way of freeing up more land for developments as well as increasing the effectives of which land is used by building in greater densities. Lord Rogers of Riverside also showed support of these views when he expressed his disapproval for David Rudlin suggestion for to Britain ‘take a confident bite out of the greenbelt’ through the introduction of 40 new garden cities on the greenbelt Rogers called it ‘a ridiculous idea’ and instead suggested developments to be stitched into existing cities using derelict sites. Rodgers put forward areas such as Croydon making reference to the available space and existing transport and infrastructure already in place as well as the added carbon emissions that would result in constructing in the green belt due to increased commutes. The justifications given by Lord Rogers are similar to the propositions but forward by (Papworth, 2015) who both stress building close to existing infrastructure but, differ in that they offer more support to the views provided by (Barker, 2004) and ideas of brownfield development.

The effectiveness of these proposals is yet to be seen but there have been suggestions by (Bramley, 1993) and (Pryce, 1999) that developers do not favour building upon brownfield land suggesting that the new quotas in the UK to encourage development on brownfield sites actually works to reduce the responsiveness of the building trade. There have also been fears expressed by ministers that developers will still favour the more profitable greenbelt land due to the increases costs attributed to site clearance and preparation of brownfield sites (Swinford, 2016) (Morris, 2016). Land Use Change statistics give merit to these fears, the stats show that area of land changing to residential that had previously developed on has continued to decline over the years with only 28% of in 2015 – 2016 which is a decrease from previous years with 36% in 2014-15 and 41% in 2013–14. There was also an increase over the course of 2015 – 2016 in the amount of vacant land that hadn’t previously been developed on converting into residential use to 34% compared with 26% in 2014 – 2015 (Department for Communities and Local Government, 2017) (Department for Communities and Local Government, 2016).

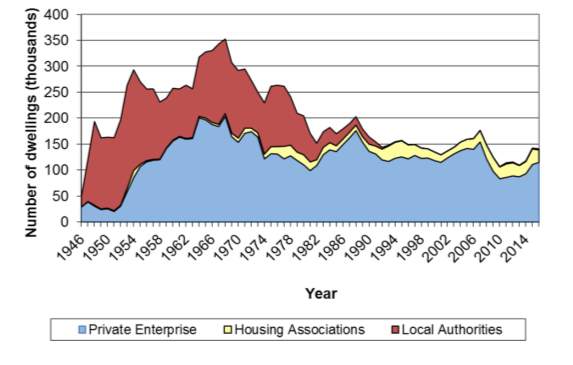

Local Authority Construction

Throughout the early half of the 19th century local authorities were the primary delivery of homes until 1951 when the conservative government began to hand responsibility of house building to the private sector leading them begin dominating the market through to current day. 1980 saw the local authorities becoming housing ‘enablers’ working with housing associations rather than direct ‘providers’ (Department for Communities and Local Government, 2017) as well as the introduction of the “Right to Buy” scheme, which gave councils tenants the right to buy their property form the council at a discounted rate if they meet certain criteria. Since its introduction the scheme has led to the council losing 1,918,323 of their dwelling to the private sector as of 20 October 2016. (Department for Communities and Local Government, 2016)

Social housing

The NHF agrees that its members’ building ambitions are thwarted by unnecessary restrictions. There are rules over how they set their rents, how properties are let and how housing stock is valued for lending purposes. These all reduce housing associations’ ability to borrow money for housebuilding, says Rachel Fisher, head of policy at the NHF.

And then there’s money. The 2010 Spending Review reduced the DCLG’s annual housing spending – which supports social housing – by about 60% to £4.5bn for the four years starting 2011-12, compared with £8.4bn over the previous three years.

This is at a time when an estimated 1.7 million people are on the social housing waiting register in England. A DCLG spokeswoman says the government has provided over 200,000 affordable homes since 2010. It will deliver 275,000 more affordable homes between 2015 and 2020, leading to the fastest rate of affordable housebuilding for two decades, she adds.

Until the 1950s, local authorities built more homes each year than the private sector (see figure

By 1957, private enterprise was constructing more houses each year than any other sector, and has remained this way ever since (see figure 1).

Glynn and Kate state that local authority can’t do enough by themselves

Kate Henderson, of the Town and Country Planning association, who believes the private sector is incapable of delivering on its own (Henry & Henderson, 2017)

Figure 2; Permanent new build dwellings completed, by tenure (Department for Communities and Local Government, 2017)

Works Cited

Amati, M. & Yokohari, M., 2006. Temporal changes and local variations in the functions of London’s green belt. Landscape and Urban Planning, 75(1-2), pp. 125-142.

Ball, M., 2009. Planning Delay and the Responsiveness of English Housing Supply. pp. 349-362.

Ball, M., Allmendinger, P. & Hughes, C., 2009. Housing supply and planning delay in the South of England. Journal of European Real Estate Research, pp. 151-169.

Barker, K., 2004. Review of Housing Supply, London: ODPM Literature.

Barker, K., 2006. Barker Review of Land Use Planning: final report – recommendations, Norwich: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office..

Beckett, D., 2014. Trends in the United Kingdom Housing, London: Office for National Statistics.

Bramley, G., 1993. The Impact on Housebuilding and House Prices. Land-Use Planning and the Housing Market in Britain, 25(7), pp. 1021-1051.

Castella, T. D., 2015. Why can’t the UK build 240,000 houses a year?, London: BBC News Magazine.

Department for Communities and Local Government, 2016. Land use change statistics 2014 to 2015, London: Department for Communities and Local Government.

Department for Communities and Local Government, 2017. English Housing Survey 2015 to 2016: headline report, London : Department for Communities and Local Government.

Department for Communities and Local Government, 2017. Fixing our broken housing market, London: Uk Government.

Department for Communities and Local Government, 2017. Land Use Change Statistics in England: 2015-16, London: Department for Communities and Local Government.

Department for Communities and Local Government, 2017. New measures to unlock brownfield land for thousands of homes. [Online]

Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/news/new-measures-to-unlock-brownfield-land-for-thousands-of-homes [Accessed 7 11 2017].

English Housing Survey , 2015. Further analysis of the 2013-14 EHS data, London: Department for Communities and Local Government.

Griffith, T. D. a. M., 2011. Forever blowing bubbles? Housing’s role in the economy, London: IPPR.

Helena Bengtsson, K. L., 2015. The widening gulf between salaries and house prices. [Online] Available at: http://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2015/sep/02/housing-market-gulf-salaries-house-prices

Hilber, C. A. L. & Vermeulen, W., 2012. The impact of supply constraints on house prices in England, s.l.: Royal Economic Society.

Malpezzi, S. & Mayo, S., 1997. Housing and Urban Development Indicators: A good idea whose time has returned. Real Estate Economics , 25(1), pp. 1-11.

Michael White, P. A., 2003. Land-use Planning and the Housing Market. A Comparative Review of the UK and the USA, pp. 953-972.

Morley, K., 2016. The Telegraph. [Online]

Available at: http://www.telegraph.co.uk/personal-banking/mortgages/generation-rent-dominates-london-property-market-for-the-first-t/ [Accessed 8 11 2017].

Morris, N., 2016. Developers could force councils to release profitable ‘greenfield sites’ by delaying ‘brownfield’ construction. [Online]

Available at: http://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/home-news/developers-could-force-councils-to-release-profitable-greenfield-sites-by-delaying-brownfield-a6962741.html [Accessed 10 11 2017].

Papworth, T., 2015. The green noose – An analysis of Green Belts and proposals for reform, UK: ASI (Research) Ltd.

Pettinger, T., 2011. How Housing Market Affects the Economy. [Online]

Available at: http://www.uk-houseprices.co.uk/blog/house-prices/how-housing-market-affects-the-economy/

Pryce, G. B. J., 1999. Assessing, perceiving and insuring credit risk. Doctoral Thesis in Economics Scottish Doctoral Programme in Economics.

Roxby, P., 2014. How does commuting affect wellbeing?, London: BBC.

Shapely, P., 2010. The housing crisis: what can we learn from history?. [Online]

Available at: http://www.historyextra.com/feature/housing-crisis-what-can-history-teach-us

Shelter, n.d. What is the housing crisis. [Online] Available at: http://england.shelter.org.uk/campaigns_/why_we_campaign/the_housing_crisis/what_is_the_housing_crisis

Swinford, S., 2016. Developers ‘sitting on brownfield land so they can build on green fields’. [Online] Available at: http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2016/03/31/developers-sitting-on-brownfield-land-so-they-can-build-on-green/ [Accessed 10 11 2017].

Titheridge, H., 2006. Changing travel to work patterns in South East England. Journal of Transport Geography, 14(1), pp. 60-75.

Wiles, C., 2013. https://www.insidehousing.co.uk/news/news/its-land-stupid-36557. [Online] [Accessed 7 11 2017].

Wiles, C., 2014. Six reasons why we should build on the green belt. [Online]

Available at: http://www.theguardian.com/housing-network/2014/may/21/six-reasons-to-build-on-green-belt

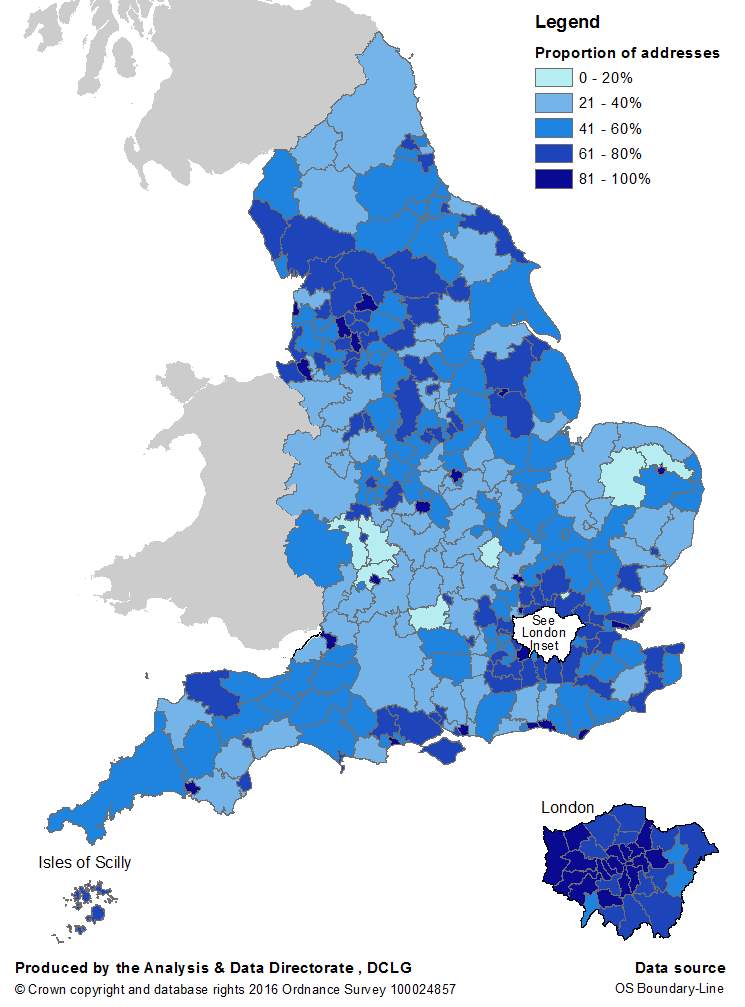

Figure 3

There was wide variation in the proportion of new residential addresses created on previously de- veloped land between local authorities in England. The lowest proportion, averaged over three years, was 15 per cent (Vale of White Horse District and Wychavon District) of all new addresses created and the highest was 100 per cent (City of London). More details are shown in

Regarding planning, the Greenbelt is a planning designation to prevent development on land that serves four purposes (ie restricting coalescence of settlements, natural beauty etc) –

define what it is and how its used –

it’s a political tool, introduced by central government and dealt with by local planning authorities who have the power to release Greenbelt land, or permit, in rare cases, development. Within the planning system, in certain areas it can often be perceived that the Green Belt is used a political tool to restrict the amount of development a district has to deliver; perhaps say in a affluent town where an influx of affordable housing may not be welcomed by local residents. Thus planning consultants, object to conclusions drawn by local planning authorities within the local plan making process, often ensuring that development can be brought forward on appropriate sites and ultimately helping Local authorities meet their housing targets (Objectively Assessed Housing Needs).

Regulatory process

lack of land

- Locked up land and interventions to release

Land banking – See Labour’s proposals to introduce CPO (Compulsory Purchase Orders) on land to ensure land is brought forward for development (Proposed policy intervention)

- Help to buy

Government intervention to ensure continuing demand in the housing market, allowing young people to ‘get on the property ladder’ whilst also ensuring that demand continues to outweigh supply, thus resulting in a persistent increase in houseprices.

Cost and affordability

- Growth of price

- Renting Up

- Mortgages down

Cite This Work

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing stye below:

Related Services

View allRelated Content

All TagsContent relating to: "Housing"

Housing is a term used for houses and other forms of living spaces that are constructed for the purpose of providing homes to people. Housing can be assigned to vulnerable people and families, to help to improve or maintain their well-being.

Related Articles

DMCA / Removal Request

If you are the original writer of this dissertation and no longer wish to have your work published on the UKDiss.com website then please: