Evaluation for Peer Support Programme for Disabled Persons

Info: 19761 words (79 pages) Dissertation

Published: 16th Dec 2019

ABSTRACT

Purpose

The peer support programme as run by Helderberg Association for Persons with Disabilities (HAPD) uses people who have disabilities to support people with disabilities (PWD) in their own community. The purpose of this formative evaluation was to explore the roles and responsibilities of peer supporters and the needs in the community. This evaluation would help HAPD explore which areas of the peer support programme could be improved.

The evaluation explored the relationship between meetable and unmeetable needs and the types of disabilities and the needs identified of the PWD. Exploring these relationships would allow HAPD to understand which needs they are more likely to meet and which areas they could improve their support in.

Problem

In South Africa, community-based rehabilitation has been evaluated but there are no evaluations that focus on the roles and responsibilities of peer supporters and the relationship between the needs that are met.

HAPD employs and assists in the training of a local PWD to support people within their own community. Peer supporters’ roles and responsibilities need to be well defined to meet the needs in the community. The needs in the community are met by providing emotional support, information, and referring cases to other service providers in the community.

The evaluation explores the types of disabilities identified, the needs of the PWD in the community, as well as the number of needs met. This information would allow HAPD to have a clearer picture of the variety of home visitations the peer supporter could face and would need to provide support in.

Methods

The evaluation used a descriptive research design and qualitative methods to evaluate the peer support programme implemented in a one-year implementation cycle. The evaluation proceeded by collecting and analysing programme documents, interviewing the chief operating officer, and facilitating a focus group.

The evaluator explored the relationships between the types of disabilities and their needs that were identified in home visitations. The disability categories were: physical, sensory, intellectual, and psychiatric disabilities. The needs categories were Health & Wellness or Education & Employment or Transport & Housing or Family & Social needs.

Results

There were 608 home visitations used in the analysis, where 22% of the home visitations had no need identified and 78% had a physical disability. There was a significant relationship between having a meetable need and the type of need category identified but no relationship between disability categories. Education, employment, health and wellness needs were more likely to be met than any other need. Needs related to transport, housing, social issues and family issues were not as likely to be met.

Conclusion

The formative evaluation of HAPD has provided information on good practice in defining roles and responsibilities, training in counselling topics, and training on specific needs in the community. The importance creating a referral network was highlighted as it provides tangible and valuable information on the resources and services available in the community. It has also highlighted some areas of improvement regarding the record keeping of training material, improvement of data collection, follow-up of home visitations, and clearer categorising of needs and disabilities in the client management tool.

HAPD has well defined roles and responsibilities which empower the peer supporters to do home visitations; the peer supporters are also empowered to become agents of change within the community.

INTRODUCTION

The Helderberg Association for Persons with Disabilities (HAPD) runs a peer support programme in the Western Cape province of South Africa. This peer support programme is committed to address the needs of people with disabilities (PWD), by building communities from the inside out. HAPD uses PWD from the community to be peer supporters and train them to support their disabled peers and assist them with their needs.

It is estimated that at least 10% of the world’s population lives with a disability, with a large part of PWD living in the developing word. It is also estimated that most PWD live in the developing world as well as them being the biggest minority worldwide. PWD remain marginalised, struggle with health conditions, are in poverty, have poor access to basic services and struggle to find employment (WHO, 2011).

In South Africa it is reported that 10% of the population has a disability and that most of these individuals live in resource poor communities and remain poor and degraded (Stats SA, 2010). The Western Cape province of South Africa contributes to 14% of the welfare grants related to disability. The Helderberg and Stellenbosch area alone has over 3600 PWDs receiving grants (Department of Social Development, 2016).

People with disabilities have fewer opportunities to socialise, are discriminated against, and face stigmas associated with having a disability. It is difficult to mobilise communities to recognise PWD as valued members of a community and that PWD can positively contribute to the community (WHO, 2010f).

To address the global need for support for PWD, Community-Based Rehabilitation (CBR) was initiated by the World Health Organisation (WHO) following the Declaration of Alma-Ata in 1978 (WHO, 2010d). CBR is a core strategy for the improvement in the quality of services for PWD. CBR places equal emphasis on inclusion, equality and socio-economic development as well as rehabilitation of all people with disabilities (CREATE, 2015).

In 1994 the International Labour Organisation (ILO), United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO) and World Health Organisation (WHO) produced a “Joint Position Paper on CBR” in order to promote a common approach to the development of CBR programmes. This paper describes CBR as a strategy within community development for the rehabilitation, equalisation of opportunities, and social inclusion of all adults and children with disabilities (ILO, UNESCO, & WHO, 2004). In 2010 the CBR guidelines were developed in response to this paper in order to provide guidelines for CBR managers and other stakeholders on how to develop and strengthen CBR programmes (WHO, 2010d). These guidelines are still used in the implementation of CBR programmes across the world and in South Africa.

Over the last 30 years the South African Department of Social Development (DSD) has implemented a number of CBR programmes over the whole country (CREATE, 2015). The DSD funds numerous projects in South Africa to support PWD in poorer communities and have integrated different CBR components and elements in programmes across the country. The details relevant to the evaluation of HAPD are discussed in the section below.

Community-Based Rehabilitation Guidelines. The overall objectives of the guidelines as provided in the CBR Guidelines: Introductory Booklet (WHO, 2010d)are to:

- Provide guidance on how to develop and strengthen CBR programmes.

- Promote a strategy for community-based inclusive development.

- Support stakeholders to meet the basic needs and enhance the quality of life of PWD.

- To encourage stakeholders to facilitate the empowerment of PWD.

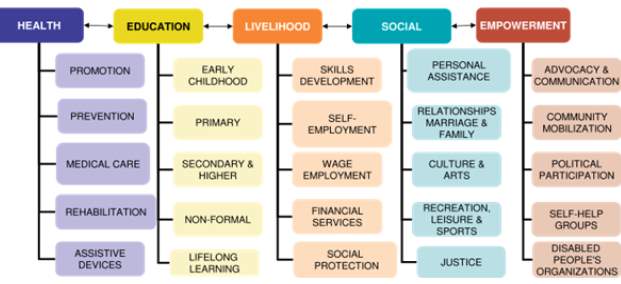

A CBR matrix was developed to provide a visual representation and a common framework for CBR programmes. The CBR matrix explained in the guidelines include activities for each component (WHO, 2010d). Individual programmes in every country determine the components that they would focus on. The matrix as seen in figure 1 consists of five components which includes five elements below the component.

Figure 1. CBR Matrix. (CREATE, 2015)

The first four components relate to the multi-sectoral approach of CBR, this includes the health, education, livelihood, and social component. The health component focuses on the health potential of PWD, and their family is recognised and empowered to enhance their existing levels of health (WHO, 2010c).

The education component focuses on providing assistance in accessing education and lifelong learning, giving PWD a sense of dignity and effective participation in society (WHO, 2010a). The livelihood component focuses on supporting PWD to gain access to a livelihood, have access to social protection measures and the ability to earn enough income to support their families and communities (WHO, 2010e). The social component focuses on the active inclusion of PWD in the social life of the community and the family. PWD should have the opportunity to participate in social activities as it has a strong impact on a person’s self-esteem and quality of life (WHO, 2010f).

The final component relates to the empowerment component of PWD, their families, and the communities. The empowerment component brings together all other components and is fundamental goal for improving the quality of life and the human rights for PWD (WHO, 2010f). This component focuses on the ability of PWD and their family members to make their own decisions and take responsibility for changing their lives and influencing their communities.

The peer support programme of HAPD integrates components and elements of the CBR matrix to support PWD in the communities they serve, the following section describes the HAPD peer support programme.

HAPD Programme Description

In South Africa, the Western Cape Association for Persons with Disabilities (WCAPD) has used peer supporters, also known as community-based facilitators, in their provincial CBR programmes (WCAPD, 2015). The WCAPD also use peer supporters who are PWD in their branches across the province, including HAPD.

Helderberg Association for Persons with Disabilities has officially been running as a non-profit organisation since 2003 and the peer support programme evaluated has been implemented by HAPD from 2015. The peer support programme’s main goal is to provide support to PWD that was not previously available in rural communities of Helderberg. The Helderberg communities include Macassar, Kayamandi, Franschhoek, and Cloetesville.

The training of peer supporters is one of the important focus areas of the peer support programme with the WCAPD providing the CBR training and the HAPD providing the other elements of the training. The peer supporters are trained to do home visitations where they provide support to PWD. At every home visitation the peer supporter identifies the disabilities and needs of PWD within the community. This detailed information is then captured to create an up to date record of the disabilities in the community.

Every home visitation and the details related to the visitation were written on paper-based client management tool. The data gained from all the home visitations is collected monthly transferred to Microsoft Excel and shared with the chief operating officer (COO) and reported to WCAPD. This information allows the HAPD to understand the context of the community they serve as well as focus the training of the peer supporters to the relevant needs and the disabilities of the community.

The home visitations also provide the opportunity for peer supporters to provide the PWD with emotional support and information regarding their needs. For example, a PWD might be recently diagnosed and would not know where to find crutches, or they might need help in making their home more accessible. Another PWD might not know that they are able to receive a social grant or would not know where to apply. Another PWD would like to find employment and does not know where to receive training or registers as a job seeker. The peer supporters would arrange follow-up visitation with the PWD depending on the need identified and the urgency of the needs or problems.

Table 1 represents the categories of needs identified, and details of which component of the CBR Matrix the needs would be classified in. The details of the needs are listed in the client management tool.

Table 1

Category of needs and details

| Need Category | Details of Needs | CBR Component & Element(s) |

| Health and wellness | Needs related to assistive devices, needs for exercise, general health problems and dealing with new disability | Health: assistive devices & rehabilitation

Social: Recreation |

| Housing and transport | Problems with accessibility to home, information on transport resources, access to clinics, and transport issues to attend clinics | Health: assistive devices

Empowerment: community mobilisation |

| Education and employment | Include needs related to wanting to get a job or be trained, or ability to work. | Education: non-formal & lifelong learning |

| Social and family issues | Applying for social welfare grants, family troubles, and drug addiction of self or family members. Included boredom, crime, and need for food parcels. | Social: Relationships & Justice |

The peer support programme evaluated includes the home visitations from March 2016 to April 2017. The programme consisted of four peer supporters who work part time, three males and one female. They were required to work a maximum of 60 hours a month and were reimbursed for travelling and phone expenses. The COO was the peer support facilitator during this year and coordinated the training of peer supporters and coordinated all activities related to the peer support programme. The COO was assisted by a part-time administrator to type up the home visitations information and other admin related duties.

The operational costs of HAPD have been funded by the DSD, the Lotto, trust funds, local municipality funding and private donors. Fundraising efforts have also included some social enterprise activities such as workshops on disability for people in the corporate sector focussing on raising awareness of disability in the sector. HAPD serves as a branch of WCAPD and receives funding from WCAPD to pay peer supporter salaries.

Programme activities. The programme activities include the training of Peer Supporters, feedback on home visitation and assisting in referrals to other service providers if needed. HAPD employs, trains, and develops the skills of PWD to become peer supporters. An important element in the peer support programme theory for HAPD is the use of peer supporters that have a disability. The selection criteria of peer supporters are based on the following criteria:

- Be a person with a disability

- Live in the community they are working in

- They have the time and energy to reach out to and serve PWD

- Ability to read and write English

- The peer supporter must have the potential to, with training, fulfil the roles expected

- Very good communication and relationship skills

- Passion and compassion to support others

- Non-judgemental, trustworthy, is a role model, respect confidentiality of PWD, and a natural leader.

HAPD coordinates two full day face to face meetings a month; with the first meeting being a training session. The second meeting was the monthly meeting to discuss any important home visitations or ask for help in the referral to other service providers. This time was also used to complete the home visitation records. The peer supporters could discuss the cases with each other to reflect and learn from each other.

One aspect of the training was based on components of CBR and other topics arranged by the COO, WCAPD was responsible for training on CBR topics. All the CBR components were covered in training for the year, but there was only one session on every component and its elements. The COO organised training on other topics to develop a better understanding of disability, other services of NGO’s, and to aid in the development of skills needed to be a peer supporter. These skills would include time management skills, understanding one self, how to work in groups, and communication skills. The COO invited Non-profit Organisations (NGO) or other service delivery organisations to do training in the areas of need that have been identified.

The aim of the CBR training for the peer supporters fits into the education component of the CBR guidelines. Although it was not formal training it can lead to the fulfilment of the potential of the peer supporters, improve a sense of dignity and self -worth. This training also builds capacity for home visitation and therefor leads to effective participation in society and their empowerment (WHO, 2010a, 2010b). The CBR training of peer supporters also fits into the empowerment component. The peer supporters are given the opportunity to communicate issues in public forums and discuss the needs of PWD. The training drives the advocacy and the communication component by allowing the peer supporters to advocate for others and participate in community (WHO, 2010b).

Target population. There are two sets of beneficiaries of the HAPD program. They include the peer supporters who are the primary beneficiaries of this programme. The skills development and capacity building of the peer supporter are an important element of the programme.

The PWD in the community are the secondary beneficiaries of the peer support programme and are the target beneficiaries. HAPD focuses on supporting adults of any age with any disability in the poorest, previously dis-advantaged areas of Helderberg. These areas are selected as they have the highest concentration of welfare grants; according to STATS SA, (2010).

HAPD is the only public benefit organisation that supports adults with disabilities in the area. Although children with disabilities needs are also captured as part of the needs analysis, they are immediately referred to existing organisations that focus on supporting children with disabilities.

Peer supporter activities. After the first month of training, the peer supporters start doing home visitations. However, the peer supporters will continue to receive training throughout the year. The peer supporter finds the PWD in the community by using snowball sampling. As they live in the area they work, they will know other PWD in their community, and with each visitation they ask for names of others PWD they might know. The peer supporters also ask at the local clinic if there could be any PWD recently admitted or sent home after rehabilitation. By using snowball sampling or being referred by the clinic the peer supporter can arrange the first home visitation.

The home visitations include sharing a personal experience of the peer supporter, listening to the PWD, giving emotional support, and providing information about the network of HAPD. This session also serves as raising awareness of the PWD of the resources available to PWD. In this home visitation, the peer supporter would ask open-ended questions about the life of the PWD and document the needs. Another focus lies in connecting the PWD in the community with other NGO’s, municipal services, networks and service providers that are available. After the visitation the peer supporter fills out the client management tool, which would include details of the beneficiary: name, age, gender, disability, address, and then a narrative paragraph is written about the need identified.

The peer supporter will most likely share health and disability-related information at the first visitation and will do a possible follow up visitation. Follow up visits are arranged by the peer supporter as they have time available and depending on the urgency of the needs identified. However, it is not clear how the follow up visitations are confirmed or selected.

The other main activity of the peer supporter programme includes raising awareness in their community. The peer supporters act as and advocates for PWD by contacting and visiting clinics, schools, training centres, work places and other organisations to promote accessibility and inclusion (ILO et al., 2004). Although awareness raising is an important activity it was not part of this evaluation.

The following section will explore the evaluations on CBR and the common recommendations made to support best practice for CBR programmes. This literature review is used as the background to the programme theory of HAPD.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Disability Models

Programmes designed to address the needs of PWD very much depend on the programmes understanding of disability and how they go about including PWD in the programme. In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, development in science helped to create an understanding that disability has a biological or a medical basis and is associated with different health conditions. Disability was seen as a medical problem and the original medical model of support to PWD focused on the cure and the provision of medical care by professionals. As disability was better understood, a social context was added, and disability became defined as a societal problem rather than an individual medical problem. The social model of disability shifted attention away from the individual but the social barriers created by the environment and others (WHO, 2010d).

The social model highlights the relationship between PWD and the society that excludes PWD from being able to participate as able-bodies people do. The social model finds it crucial to address how people, groups, and organisations construct meaning about disability.

Danforth (2001) suggests the social model is preferred to the earlier medical model, where the disability was seen as a condition or problem and providing the person with medical support would solve the problems that PWD face. The ILO, UNESCO and WHO (2004) suggest that the social model of disability has increased awareness that environmental barriers to participation has a major contribution to the cause of disability.

As depicted by the cartoon in figure 1, the medical and social models can oppose each other. The medical model suggests by providing prosthetics that PWD would be able to find their way up the stairs. The social model suggests that the environment creates the barrier and by providing better access the PWD would be able to go where they need to be (Miller, 2014). Programmes develop their activities around the model they follow, and this determines how PWD are supported.

Figure 2. Social Model vs Medical model (Miller, 2014)

Exploring the minority group model as described by Danforth (2001) and the definition of disability from the International Classification of Functioning Disability and Health (ICF), they both consider the biological, psychological, and social elements that contribute to disability (Madden et al., 2014). This suggests that the activities and participation of both the individual and the society should be addressed in disability support programmes.

HAPD integrates the social model in the peer support programme, acknowledging that using peer supporters that have a disability allows the opportunity for PWD to challenge the community norms. HAPD aims to support the PWD and their needs, but also realises that the common attitudes, beliefs, and structures of society put PWD at a social and economic disadvantage. HAPD raises awareness within communities by using PWD peer supporters, allowing the peer supporters to become change agents in their own community. This approach of working with PWD and using their disability as an advantage, allows the peer supporters to be more effective in supporting PWD. It affords PWD the chance to be positive examples in the community (Davidson et al., 2005; WHO, 2010c). This approach allows the peer supporters to be empowered in how they interact with their environment.

Rule, Lorenzo, and Wolmarans (2006) suggest that the ownership of CBR programmes need to be directed by PWD, where PWD become more than just the service recipient but a service provider. The peer supporter becomes a change agent.

Peer Supporters

CBR guidelines use the term CBR facilitators or CBR workers, which are defined as the people who work at community level, they are seen as a central part of disability programmes (Rule et al., 2006; WHO, 2010b). The WCAPD and HAPD refer to a CBR facilitator as a peer supporter. Peer supporters will mostly be used in the following description of their role and CBR facilitators will be used referring to research that includes that specific wording.

An impact evaluation of CBR programs, which included a baseline follow-up and an audit of record, in Palestine mentioned that it was the contribution of the work of CBR facilitators at individual and family level that brought about the direct and unique impact in the community (Eide, 2006).

A qualitative research design which used participatory methods in exploring the impact of CBR programs focusing CBR facilitators found that is the unique element of seeing PWD at their home brought about a special connection. PWD were CBR facilitators who were local, available and approachable (Chappell & Johannsmeier, 2009).

Peers who are PWD and understand the context of being a PWD, they also understand the community and the culture they work in. Of the trained CBR facilitators in South Africa, just over a quarter of them are PWD or family members of PWD (Rule, 2006).

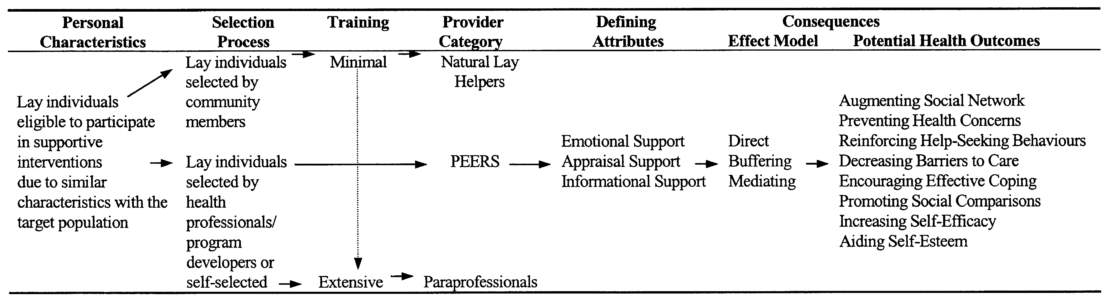

A concept analysis of peer support for the nursing profession analysed by Dennis (2003), suggest peer supporters can emerge from lay individuals who are eligible to support others and can be selected by the community to be lay helpers. If lay individuals are chosen by health programmes and trained, they can develop into peers or into paraprofessionals in time. Figure 3 represents the development of lay workers into peers and then paraprofessionals as suggested by Dennis (2003).

Figure 3 Conceptual distinctions of peer support by Dennis (2003).

Dennis (2003) also provides a definition of peer support and suggests it is the provision of assistance and encouragement by an individual considered equal. Although noted as a rudimentary interpretation the paper further elaborates on the use of peer supporters in health literature and defines common attributes of peer support that stretch across all settings. The distinct attributes that repeatedly emerge that correspond to the peer support programme include: emotional support and informational support.

Emotional support. Peers who are PWD can provide emotional support as they understand and have experienced first-hand the barriers and challenges PWD face. It could range from having limited access to public and health services, knowledge of disability rights and limited understanding and knowledge of their own disability (CREATE, 2015). Peer supporters might be limited to supporting someone with a different disability than their own, but they can still understand the difficulty in becoming a PWD.

Boothroyd and Fisher (2010) explored the Peers for Progress Programme which found that emotional and social support is a key function of peer support. It is also an important element in measuring and evaluating the effect that peer support offers. Peers encourage the use of skills in dealing with stress, they also create opportunities and are available to talk about negative emotions. When the peer supporter shares their own experience of their situations and success, the peer supporter can help the PWD understand their problems and situation better (Davidson et al., 2005). An two phase outcome evaluation of peer support for women with breast cancer highlighted that the women receiving support felt less anxious after a visit, especially if the peer supporter had similar problems (Dunn, Steginga, Occhipinti, & Wilson, 1999).

When PWD are emotionally supported it allows the PWD to make sense of their environment (Davidson et al., 2005) and in turn empowers PWD to see the different opportunities that are available. The emotional support of PWD can lead to their empowerment which is a core cross-cutting theme for enabling PWD to access all opportunities (ILO et al., 2004; WHO, 2010b). CBR facilitators address a major need regarding the psychological needs of PWD (Chappell & Johannsmeier, 2009)

Information support. A crucial contribution that peers supporters can make, includes providing information about disability and information on the services available in and outside the community (ILO et al., 2004). Rule et al. (2006) explores the challenges of CBR within South Africa and suggest that CBR programmes need to have formal links with the Departments of Education, Social Services, Health, Labour and Housing to be successful.

The ability to develop a network of service providers and build awareness in the community is one of the foundation outcomes and principles of CBR (WHO, 2010). Peers supporters can link people to clinical care; they can become a liaison to other health services and can empower the PWD to seek quality care (Boothroyd & Fisher 2010). Peer supporters can also link PWD to many other service providers and this referral network that they build is a critical element to the development of the community that PWD live in (Rule et al., 2006).

A thematic qualitative analysis of 37 CBR evaluations by Kuipers, Wirz, & Hartley (2008) found that a critical element linked to informational support is the referral network. A referral network requires active collaboration across organisations, government departments, and international NGO’s to enhance the networks available (Kuipers, Wirz, & Hartley, 2008). The on-going process of building and maintaining networks and relationships is crucial to the work of a peer supporter.

Peer supporters initially provide information to PWD about the service HAPD provide and from there the peer supporter becomes an important information source of support to the PWD. The peer supporter becomes the link between the support to the PWD and the resources they need in the community. CBR projects cannot work in isolation, if there is no network and collaboration it will not succeed (ILO et al., 2004).

Boyce and Ballantyne (2000) argue that disability, rehabilitation and evaluation depend on information and that CBR programmes should focus on gathering and disseminating information. They also suggest that evaluating the referral network of CBR programs is one of the stepping stones to explore if the CBR programmes focus on empowerment of the PWD in the community. An article by Lightfoot (2004) which examined the strengths and weaknesses of CBR for social workers suggest that the referral network is essential to keeping projects sustainable.

The roles and responsibilities of peer supporters should be well defined and include the emotional and informational support they provide. The roles and responsibilities should also be supplemented by training.

Roles and responsibilities of the Peer Supporter

Chappell and Johannsmeier (2009) evaluated the impact of CBR facilitators delivering CBR programmes by using qualitative methods and found that there was a lack of clarity in the roles of CBR facilitators. Although this impact evaluation used participants from across the country with different disabilities, it did not explore the programme documents.

CBR programmes face challenges in bringing all stakeholders to the table and defining roles and responsibilities as the need for support to PWD is so large. Many health professionals don’t understand the role of CBR facilitators and could not use them due to not having a clear understanding of their roles (Chappell & Johannsmeier, 2009). Major weaknesses found in the evaluation of CBR programmes globally, are management-related. The thematic qualitative analysis of disability and development programmes by Kuipers et al. (2008) provide that the weaknesses in CBR programmes include lack of policy frameworks, implementation strategies, organisational, administrative, and personal management structures. If the management of the organisation is not well run the roles and responsibilities will not be well defined.

Although CBR programmes do provide quality care and services to PWD (Chappell & Johannsmeier, 2009; Davidson et al., 2005; Dennis, 2003), the roles and responsibilities of peer supporters require a complex interconnected support system where the implementing agent needs to take considerable time in defining their roles and responsibilities.

The roles and responsibilities of peer supporters need to be tailored to individuals, community contexts and PWD need to be part of this process. (Madden et al., 2014). The process of describing the roles and responsibilities can be influenced by many elements, such as the community and the training of the peer supporters. If peer supporters are from the community in which they work, they add a unique and positive aspect to community development (Boothroyd & Fisher, 2010). On the other hand if the CRB facilitators, peer supporters, are local it can add some strain to the scope of support they provide, and they can be asked to do more than the roles requires or they might not do what is expected (Chappell & Johannsmeier, 2009). The roles and responsibilities need to be well defined to allow peer supporters to manage the support they provide.

An important element that influences the implementing of CBR programmes consistently is the training the peer supporters receive. The following section explores other evaluations of CBR programmes and the findings regarding training.

Peer Support Training

A systematic review of CBR in Southern Africa found that training is a common activity in CBR programmes as well as educating the community on disability (M’Kumbuzi & Myezwa, 2016). HAPD coordinates training of the peer supporters every month and sees training as one of the important aspects of providing substantial and relevant support to PWD. The training that peer supporters receive can have a major influence on their performance and their ability to provide support. (Ravesloot et al., 2007).

Kuipers et al. (2008) found in the thematic qualitative analysis of CBR evaluation reports that a major theme that emerged consistently was the content of training. The article states that training CBR workers on types of disability and adaptations of environments have been major recommendations to CBR projects. Programmes need to integrate these themes in the training schedule.

Rule et al. (2003) explores the challenges of implementing CBR projects and suggest there is a need to develop accredited training for CBR facilitators. Accredited training will allow peer supporters to become registered and employed as professionals. Rule et al. (2003) further says that the training for CBR workers in higher education institutions mainly focus on rehabilitation with less consideration of equal opportunities and social integration. CBR programmes like HAPD provides opportunities for PWD to learn and be empowered by the training.

Evaluations in CBR have highlighted the importance of CBR curricula to be enhanced and understood by all staff and stakeholders, at all levels. CBR training is fundamentally based on training within the community for the community. A strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats analysis of CBR evaluations by Sharma (2007) found that the training of CBR workers was a common suggestion as an opportunity to improve CBR programmes. The training of peer supporters should be empowering, (Rule, 2013) equipping them with the knowledge and skills to be a support PWD with various needs.

Programme Theory

A programme theory helps the programme staff and other stakeholders to understand what the programme has achieved, but also which variables contributed to the programme effect (Donaldson & Lipsey, 2014; Rossi, Lipsey, & Freeman, 2004). A programme theory can assist programme managers and evaluators to design evaluation tools to measure the performance of programmes. As programmes do not stand alone but within its context (Donaldson & Lipsey, 2014), the programme theory can identify important moderators and mediator of change.

A programme theory as defined by Chen (2006) was created for the peer support programme of HAPD to assist in the design of the formative evaluation. A programme theory allows the evaluator to create questions based on the theory of the programme, or elements within the program.

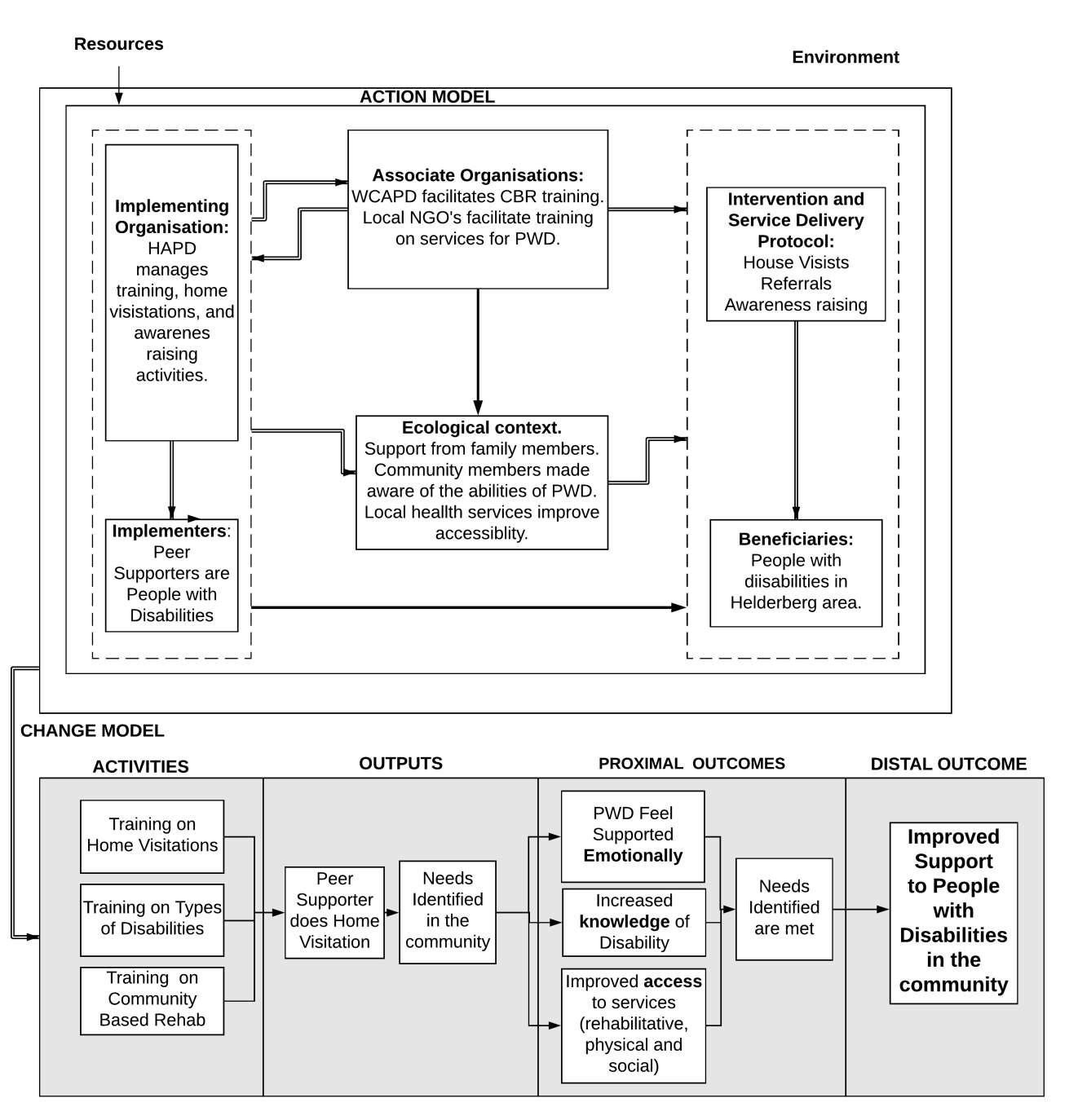

The programme theory is represented in Figure 3, representing the action model and a change model. The action model block represents a systematic plan for arranging staff, resources, setting, and support organisation to reach its target population and provide the intervention service. The six components include: the implementing organisation, implementers, associate organisations, ecological context, the service delivery protocol, and the beneficiaries, all of which influence each other in the implementation of the programme (Chen, 2006). The blocks were populated by using the HAPD programme description.

The change model represents the underlying causal processes of the HAPD programme. It includes the programme activities as the determinants and the mechanism which drive the programme to reach the long-term/distal outcome. If the peer supporters are trained on types of disabilities, CBR, and how to do home visitations the peers supporters will be able to do home visitations. As the peer supporters do home visitations they will be able to identify the needs in the community. After the needs are identified the peer supporters can emotionally support PWD, share information on their needs, and connect PWD to other resources in the community. If the peer supporters meet the needs of PWD in the community, they will be improving the support available to PWD.

Figure 4. Theory of Impact Model of HAPD.

HAPD has a plausible programme theory as trains PWD to be the peer supporters and empowers PWD to become change agents in the community, HAPD also does not work in isolation and networks with other organisations to improve the scope of support to PWD.

It can be assumed that the programme theory of HAPD will lead to an increased support for people with disabilities if all the components are implemented as designed. If the programme theory is plausible the next level within the hierarchy of evaluation is exploring the implementation/process of the programme (Rossi et al., 2004). After evaluating the implementation/process of the program the outcomes of the programme can be evaluated. The following section elaborates on the background of choosing the evaluation questions for the formative evaluation of HAPD (Rossi et al., 2004).

Evaluation Design

The evaluator was working as an administrator at HAPD from February 2017 to April 2017 and from May to November 2017 as the fundraiser. The evaluator had built a rapport with the peer supporters before the evaluation and was familiar with the programme. As the opportunity became available to do an evaluation with any organisation that has implemented programme for more than a year, the evaluator asked permission from the course convener to evaluate HAPD.

The COO agreed to do a formative evaluation to explore the areas where the peer support programme could improve, especially as HAPD would be integrating the peer support programme into their new community development programme for the future. A formative evaluation allows the evaluator to make recommendations regarding the implementation of the peer support programme (Rossi et al., 2004; Wholey, Hatry, & Newcomer, 2010). The formative evaluation for HAPD included a process evaluation and an evaluation of the proximal outcome.

The process evaluation was used to explore whether the peer supporters’ roles and responsibilities were well defined and how it compares to the needs identified of PWD in the community. If their roles and responsibilities are clearly defined they are more likely to support a PWD. These roles and responsibilities should reflect the needs of PWD in the community. If the roles and responsibilities were not well defined the peer supporters would not be able to support the PWD well (CREATE, 2015; European Commission, 2004; M’Kumbuzi & Myezwa, 2016).

Understanding the roles and responsibilities of peer supporters well could help transfer some of the responsibility of specialised services needed to relevant professionals in the community (Price & Kuipers, 2000). The roles and responsibilities should also consider the physical barriers related to access to the community that peer supporters face being a PWD themselves. If these barriers are not addressed they will not be able to fulfil their role as a peer supporter (WHO, 2011).

The peer support programme at HAPD had only been implemented for a year and a distal outcome evaluation would not be possible as it would require more baseline information and more years of implementation (Rossi et al., 2004). This proximal outcome evaluation explored the needs and the types of disabilities of PWD in the community, and which of these characteristics made it more likely to have a meetable need. This information would help HAPD understand who they mostly support, and which characteristics are associated with meetable needs. The details of classifying need as meetable needs are discussed in the methodology.

Process Evaluation Questions

- Question 1.

- Are the roles and responsibilities of peer supporters well defined by HAPD?

- Do peer supporters fulfil their roles and responsibilities as expected by HAPD?

- Do the roles and responsibilities reflect the need of the PWD in the community?

- Are the roles and responsibilities relevant considering that peer supporters are people with disabilities?

- Question 2

- How many home visitations have the peer supporters done in the communities they serve?

- How many client needs were identified by peer supporters?

Proximal Outcome Evaluation Questions

- Was the programme better able to meet the needs of certain types of disabilities or needs categories?

METHODOLOGY

Design

This evaluation used a descriptive design to evaluate the peer support programme the descriptive design allowed the evaluator to explore the characteristics of the PWD in the client management tool. The categories created in the client management tool allowed the evaluator to calculate the frequencies of disability categories, needs identified and the needs that were met.

Qualitative methods were used to explore the roles and responsibilities of the PWD. The qualitative methods used to explore the roles and responsibilities included: interviews, a focus group and the analysis of documents (Ritchie, J. Lewis, 2003). As there were no previous evaluations or research on the peer support topic in this context and it was not structured around a hypothesis or experiment a descriptive design was preferred. It was not possible to create a control group due to time restrictions, resources available, and the nature of the evaluation did not require control groups to be created.

A descriptive design might only reflect the unique sample of peer supporters and the PWD visited at HAPD, but it could bring understanding to the complex nature of being a peer supporter. The results of this research could be helpful to other organisations that work for and with PWD in South Africa.

Descriptive and inferential statistics was used to compile tables related to evaluation questions, exploring demographic details of PWD, and calculating odds ratios to determine the likelihood of needs met over others.

Data Providers

The data providers consisted of two sets of participants: the chief operating officer (COO) of HAPD and four peer supporters. Information gathered from each data provider was used to answer or supplement all evaluation questions.

The COO was able to provide resources and was available for an interview and ad hoc questions when reviewing documents. The four peer supporters (three males and one female) working at HAPD were able to provide qualitative information regarding their roles and responsibility as a peer supporter, their training, and their experience as PWD being peer supporters.

Primary Data Collection Materials

Interview with COO. The semi-structured questions for the interview included the following themes: the roles and responsibilities of peer supporters and the training provided by WCAPD and HAPD. Please see Appendix A for the questions. The discussion and answers to the interview questions were written down as the interview progressed and analysed after the interview to identify categories and drawn into themes. These themes were derived inductively as there were no themes or categories developed before the interview.

Focus group discussion with peer supporters. There was one focus group which explored the roles and responsibilities of peer supporters and the experience of being a peer supporter with a disability. Please see Appendix B for the questions.

Focus groups with all four peer supporters present were preferred over individual interviews as the evaluator was interested in the experience of the peer supporters’ attitudes, feelings, experiences and reactions as a peer supporter group. As there were only 4 participants it allowed the evaluator to explore themes in-depth with the peer supporters at the monthly meetings (Freitas, Oliveira, Jenkins, & Popjoy, 1998).

It was also easier logistically to see the peer supporters on the days they were scheduled to attend training. The peer supporters face some challenges to move beyond their community unless they come to the HAPD premises for training or meetings; another benefit is that the transport costs of the peer supporters are covered for these training days.

As the evaluator was familiar with the peer supporters as they were relaxed when the focus group started. The evaluator explained the purpose of the evaluation and reminded the peer supporters that their answer would be confidential, and that no names would be shared with the COO or any other party. They were also given time to read and sign the consent forms.

The evaluator asked the questions one by one. The answers were written on a flip chart and the evaluator asked the peer supporter if they agreed with the words written down. The evaluator was able to determine the degree of consensus on a topic in a focus group and explore themes that could support the data collected from other parts of the study (Bernard, 2006). The peer supporters expressed their opinions and experience with each other in the focus group and the evaluator allowed for themes that arose from the questions to be explored. The focus group was an hour and half long.

The information written on the flip chart were analysed to identify categories and in turn themes to understand the roles and responsibilities, no categories or themes were chosen before the focus group (Bernard, 2006). The themes were compared to the themes found in the interview with the COO to answer the evaluation questions.

Secondary Data Materials

All the secondary data materials were analysed using the thematic analysis approach (Ritchie, J. Lewis, 2003). The data was organised, generated into themes, coded, tested to explore emergent understanding, seeking alternative understanding, and writing-up of the data according to the evaluation questions.

Home visitation data set. The organisation provided the evaluator with an excel summary of the home visitations which composed of a set of longitudinal data set of 765 data entries of home visitations seen by 4 peer supporters over a period of one year of the implementation cycle, 1 April 2016 to 31 March 2017.

Each peer supporter collected the following information of every home visitation and wrote it on a client management tool which contained.

- Name, date, gender, contact details, address, race, length of visit and disability.

- A narrative explanation of the needs identified, or the problems discussed.

- Space was provided on the client manage tool to indicate the follow-up process, but this was rarely completed.

Incomplete information of home visitations was not considered for analysis.

Training resources. A MS Word document which had a table with training topics was available it included dates, topics, and duration of training, please see Appendix F.

Programme documents. HAPD had programme document available regarding the roles and responsibilities which included a bullet point list of activities. HAPD also provided the evaluator with an activity description from WCAPD which included time frames and details for all the activities for a peer support programme. The evaluator compared the bullet point list and the activity description and created a table to explore the differences and similarities in the roles and responsibilities. Please see Appendix D and E for these documents.

Procedure

Ethics. Ethical clearance was requested and granted by the University of Cape Town Department of Commerce. The programme signed a consent form for the use of its data. Peer supporters provided informed consent before they participated in the focus group. They were free to withdraw from the research at any time. Please see Appendix C for the peer supporter consent forms.

None of the peer supporters has an auditory or visual impairment. None of the peer supporters in the focus group had an intellectual disability thus the evaluator did not need to consider parental or consent from a guardian (National Disability Authority, 2009).

The client management tool has already been typed up in excel format by HAPD, and the programme documents were requested by the evaluator and provided by HAPD. The identity of all beneficiaries would be protected as all information provided by the programme was kept confidential on a password protected computer.

Data Analysis

As this is a descriptive research design to evaluate the peer support programme, qualitative and quantitative methods were used to describe and analyse the data.

Answering evaluation question 1. 1. a. Are the roles and responsibilities of peer supporters well defined by HAPD? The activity descriptions from WCAPD and the list of roles and responsibilities from HAPD were analysed and compared and used as the reference to determine what was defined as roles and responsibilities. Comparing the lists of the roles and responsibilities to each other and using the focus group the evaluator could explore if there are any gaps and if the roles and responsibilities are well defined.

b. Do peer supporters fulfil their roles and responsibilities as expected by HAPD?To determine if the peer supporters fulfilled their roles and responsibilities the interview with the COO, programme documents and the focus group was used to explore the question.

c. Do the roles and responsibilities reflect the need of the PWD in the community? The client management tool was used to calculate the percentage of needs and the physical disabilities types of the PWD in the community. The physical disabilities categories were categorised in more detail as it provided information on the vast amount of disabilities that were identified.

There were over 15 different types or names for disabilities in the client management tool, as this was too many categories to use they were condensed to make it easier to analyse. Table 2 represents the disability categories created and the details mentioned in the client management tool, the disabilities were categorised by the most common disabilities identified (WHO, 2011).

Table 2

Categories of Disabilities

| Disability Category | Details in Client management tool |

| Physical Disability. | Mobility Impairment, Stroke, Amputation, Cerebral Palsy, Polio, Head Injuries or Anything Related |

| Sensory Disability | Vision or Hearing Loss or Anything Related |

| Intellectual Disability | Intellectual Impairment 0r Anything Related |

| Peer psychiatric Disability | Mental Health Problems or Anything Related |

The percentages and frequencies of the disability categories and needs were compared to the roles and responsibilities to determine if it reflected the need of the PWD.

d. Are the roles and responsibilities relevant considering that peer supporters are people with disabilities? The focus groups with the peer supporters explored the roles and responsibilities as experienced by peer supporters and their own experience of being a PWD. Please see Appendix B for the focus group discussion questions.

Answering evaluation question 2 and 3. 2. a. How many home visitations have the peer supporters done in the communities they serve? The client management tool was available in a MS Excel dataset and transferred to IBM SSPS 24 statistical software. Initially, there were 765 entries for home visitations, after cleaning the data 608 home visitations were available for analysis. Entries that had no physical documents, no dates and no names were not considered.

The list of 765 was reduced to 608, this list of 608 visitations was a combination of new clients and re-visitations, the frequencies and totals were calculated for each. 48% were new visitations, i.e. new clients, and these entries were used in the description of age, sex and race.

2. b. How many client needs were identified by peer supporters? The needs are represented by the needs identified in the community. After the data was transferred to SPSS 24 the categories of disabilities and needs were created and coded to nominal values of 1, 2, 3, and 4 for each category. This allowed the qualitative data to be represented in nominal categories to be analysed (Field, 2013). The entries and column headings were double checked to make sure that entries were labeled and it was entered correctly. Please see table 1 for the need categories.

3. Was the programme better able to meet the needs of certain types of disabilities or needs categories? Meetable needs would indicate the peer supporters could support the PWD with information and/or be able to alleviate the need within their scope of work and training. An unmeetable need is a need that could not be addressed as it would fall outside the scope of work or training of the peer supporter. Table 4 provides details on meetable or unmeetable in different need categories.

Table 3

Categories on Needs and Classification of Meetable or Unmeetable Needs

| Need Category | Meetable Need | Unmeetable Need |

| Health & Wellness | PWD need assistive devices.

Information on bedsores. Need for exercise |

Need daily personal assistance.

Other health problems regarding organs Medication related |

| Education & Employment | Would like to find work.

Want information on skills development |

Struggling to find alternative schools for children. |

| Transport & Housing | Need information of transport provided by clinics.

Information regarding accessible government homes |

Request transport

House infrastructure problems |

| Social & Family Issues | Assistance with grant application | Family members using drugs.

Family issues Divorce Safety |

Needs were categorized as meetable or unmeetable by using the peer supporters experience and the evaluators understanding of the program, the totals of these categories were tabulated and cross-tabulated with disability and need categories. The crosstabulation and Chi-square test of independence was run on SPSS 24 to determine whether the (un)meetable needs were statistically independent or if they were associated with the different need or disability categories (Michael, 2001). The odds of having needs met were also calculated to explore the relationships between the needs and disability categories.

RESULTS

Process Evaluation Question 1

1.a. Are the roles and responsibilities of peer supporters well defined?

The HAPD roles and responsibilities added bullet points for each activity and this allowed the evaluator to identify each activity, but as it was only one word per activity, it created some difficulty to understand the complete role of the peer supporters. It was also difficult to determine the priorities between each activity or the sequence of implementation of different activities.

The WCAPD activity description of the roles and responsibilities included clearer details on each activity and gave specific information around time allocations for activities. Table 4 list the main activities for HAPD and WCAPD and the notes provide comments on details that differ or are similar.

Table 4

WCAPD and HAPD Main Activity list

| Activity Name | Notes | |

| WCAPD | HAPD | |

| Home Visitations | Support Adults with Disabilities & Their Families | HAPD lists steps about home visitations

WCAPD adds details of minimum and maximum times for home visitation. |

| Group Sessions | – | HAPD lists the details of group sessions as part of the home visitation sessions.

WCAPD provides details on how to organise a session for PWD only, separate from the sessions from awareness raising sessions. |

| Awareness Activities | Awareness-Raising & Advocacy | WCAPD specifies this activity amongst local or broader public. Time-frames for awareness raising activities included time limitations. |

| Branch Related Tasks | – | Not mentioned in HAPD list.

This includes supporting the branch in any tasks, could be part of skills development for peer supporter. |

| – | Networking | HAPD lists details regarding the exact tasks to link to new service providers.

WCAPD described the Networking activity as Awareness raising for the PEER SUPPORTER. |

| Mentoring/ Training | – | Training was not listed as activity in HAPD. WCAPD defined mentoring as monthly meetings, individual consultations, and training. |

| Admin | Administration | HAPD & WCAPD has similar descriptions.

WCAPD adds details of the maximum hour to claim for admin and supports PWD with more flexible admin hours if they might have difficulty with writing. |

| Other activities | – | Other activities not listed in HAPD list.

WCAPD includes all other activities/meetings/ events related to disability but indicated that the coordinator should monitor it. |

| – | Accountability & Reporting | HAPD list other skills needed to be a peer supporter related to accountability and reporting. |

Although the list of HAPD does not read as easily as the WCAPD list, the WCAPD adds the descriptions of the activities to make the roles and responsibilities easier to understand. There was still not exact clarity on the priorities of each activity, but the roles and responsibilities of a peer supporter could be understood from these lists.

Using both lists the roles and responsibilities can be suggested to be well defined from an administrative and programme implementation perspective but there were other aspects of the roles and responsibilities stated by all the peer supporters in the focus group that indicated that there are gaps in the peer supporter.

In the focus group the peer supporters were asked to list the main activities of a peer supporter, the following broad categories were listed: providing information, emotional support to PWD, planning visitations, using a diary, visiting the clients, listening to them and writing up notes on client management tool. The evaluator made notes of the details and these activities were reflected in the roles and responsibilities of HAPD.

The peer supporters expressed that they felt like they fulfil many roles in the community, they felt like social workers, physiotherapists, psychiatrists, a doctor, and a close friend. The peer supporter mentioned being called at different times of the day to help with daily tasks, to attend special events, and speak to family members.

The peer supporters mentioned that fulfilling so many roles was very tiring. They felt that they were more than just a peer supporter and the all the peer supporters agreed together when one mentioned they are the “angels of disability”. They are seen by the community as people that could do anything and knows everybody.

The peer supporters feel under pressure regarding all the roles that they are requested or expected to fulfil by the PWD in the community, this mostly refers to the roles that fall outside their job description.

The evaluator asked about the positive aspects of these ‘other’ roles they mentioned, peer supporters said that it made them feel confident in the community and that they felt they were needed.

The evaluator asked on the negative aspects of these roles all the peer supporters reinforced the following comments as they were mentioned:

“Gets hectic”

“They always expecting something”

“It takes a lot of energy”

“They come with a lot of personal problems”.

The peer supporter said they initially needed to get used to being a “crutch for someone”. This suggests that there is an important emotional component to the roles and responsibilities of peer support that is not reflected in the list described by WCAPD and HAPD. The emotional component is a critical element to the support peer supporters provide.

The list of roles and responsibilities of HAPD was presented to the peer supporter after they had discussed their own roles and responsibilities and they commented that the list was very detailed. The peer supporter said they did not know that the work would be so detailed and demanding when they applied for the position. They all confirmed when one peer supporter commented that list was missing the emotional aspect of the work they do.

In answering the evaluation question 1 it can be confirmed that the roles and responsibilities is well defined from an administrative perspective but there is a crucial element missing regarding the emotional demand that is placed on the peer supporters.

b. Do peer supporters fulfill their roles and responsibilities as expected by HAPD? The COO expressed that HAPD employs PWD that had no or very little working experience and by efforts in training, mentoring and support, HAPD supported them to develop into a peer supporter. The interview with the COO suggested that HAPD aims to develop peer supporters to fulfil their role as peer supporters, to train PWD to have the skills to do needs assessments, provide specific information to PWD, and network within the community.

Each month a training day and a monthly meeting consisted of supporting the peer supporter and developing skills to improve the knowledge base in CBR, building confidence in home visitations, and understanding of services in the community. The monthly meetings included discussion on targets and setting realistic goals for each peer supporter regarding home visitations and other activities. These sessions allowed the peer supporters to grow into their role as a peer supporter.

The peer supporter needed to submit proof of all home visitations they had done by completing the details on the client management tool, if this was not submitted monthly the peer supporter would not receive their wages.

It was a benefit to having the roles and responsibilities well defined from an administrative point and allowed the COO to monitor peer supporter activities. The client management tool allowed the COO to keep track of activities and targets and the COO could follow up on if a peer supporter did not meet these goals as expected from HAPD each month. All peer supporters would report to the COO on the targets they did not reach, and the COO could discuss the details and find ways peer supporter meet the goals.

In answering evaluation question 1b it can be assumed that the peer supporter was able to fulfill their roles and responsibilities as expected by HAPD. The peer supporter did mention they needed the help of a social worker. A social worker would specifically help the peer supporter to cope with the emotional stressors that were expected from working with PWD, one aspect is that the peer supporter would be able to share/refer difficult cases.

c. Do the roles and responsibilities reflect the need of the PWD in the community? The need in the communities that the peer supporters serve can be represented by the variety of needs identified and by the types of disabilities that were identified with each home visitation. The needs and the disabilities create a unique combination of home visitations that the peer supporters need to be ready for to provide support in, it is a difficult task as there were many needs and disabilities identified.

Table 5 below represents the details of categories and percentage of different needs of persons with disabilities in the community. The highest needs fall within health and wellness needs which contribute to 29.9% of needs identified. The second needs highest relate to transport and housing at 19.7%.

Table 5

Percentage of Needs Identified

| Health & Wellness | Transport & Housing | Social & Family Issues | Education & Employ-ment | No Needs Identi-fied | |

| Percentage of needs identified | 29.9% | 19.7% | 16.3% | 12.5% | 21.6% |

Note: N = 608.

It was difficult to categorise the disabilities mentioned in the client management tool as there were numerous types of disabilities named in the client management tool, to overcome this challenge the disabilities were categorised into four main types of disability: physical, sensory, intellectual, psychiatric and other. Please see Table 2 for details.

The following table 6 represents the percentage of categories of the four main disabilities in the community.

Table 6

Percentage of Disabilities Categories

| Physical Disability | Sensory Disability | Intellectual Disability | Psychiatric Disability | Other | No Disability Identified |

| 79% | 7% | 6% | 0.5% | 6% | 1.5% |

Note: N = 608. Sample including home visitations with no needs identified.

Physical disabilities were 79% or the disabilities identified, this category was explored further to distinguish the different physical disabilities. There was some challenge to analyse some of the descriptions of the physical disabilities, for example, when a stroke was noted, it was not clear if it caused mobility impairment or a sensory impairment. As stroke and mobility impairment were listed in the client management tool as separate disabilities, they were categorised as separate physical disabilities in the table. Table 7 below represents the categories of physical disabilities found in the client management tool.

Table 7

Percentage of different types of physical disabilities

| Mobility Impairment | Stroke | Other* | Amputee |

| 38% | 25% | 20% | 17% |

Note: N = 480.

* Other physical disabilities related to physical disabilities include: Muscular Dystrophy, Spina Bifida, Arthritis, Polio, Meningitis, Cerebral Palsy, and head injuries.

Mobility impairment has the highest percentage in the physical disabilities category at 38% but the client management tool does not provide enough information regarding the details of the disability. 25% of the physical disabilities could be related to stroke and 20% to any other kind of combination of physical disability.

Tables 5, 6 & 7 show the variety of disabilities the peer supporters encountered in home visitations as well as the main categories of needs. The lists of roles and responsibilities as described in the previous questions, provides details needed for home visitations, support in how to disseminate specific information to PWD and address the different needs in a systematic way. It cannot however list all the combinations of disabilities and the needs that peer supporters encounter.

An example would be where one PWD could have physical disabiltiy and have a transport related problem that could be met by providing information of clinic transport for PWD on quarterly clinic days. Another PWD could also have a physical disability and a transport need, but the peer supporter would not be able to provide transport to support the PWD getting to a medical professional. Thus is some home visitations the peer supporter can meet a need and they would not be able in another visit, although they have the same disability and need categories.

In answering question 1b it can be seen from the list of roles and responsibilities that it aims to equip the peer supporter to systematically address different activities that are needed to support PWD in the community but is not clear if the roles and responsibilities can reflect the large variety of needs and disabilities identified in the community.

d. Are the roles and responsibilities defined considering that peer supporters are people with disabilities?One of the key criteria for being a peer supporter is the ability to visit a PWD at their home although it was a bit of a challenge as all the peer supporters had a physical disability. In the focus group, the peer supporters discussed how having accessibility constraints made it difficult to visit PWD but that it could be overcome if they phoned in advance and knew the address. The peer supporters said they were always aware of the weather and how that influenced their home visitations.

The peer supporters discussed that able-bodied people could do home visitations much easier as they would have fewer physical barriers to deal with. The peer supporters did feel though that PWD could understand PWD better than able-bodied people could. They suggested if an able-bodied person had someone close to them with a disability it would help them understand disability better than only have a theoretical background. The peer supporters felt being a PWD was an advantage.

The peer supporters explained that although they face some physical barriers to see the PWD they know that because they themselves are PWD and have experienced the stressors themselves that they can give hope and they can “help our peers excel”.

The peer supporters mentioned that working with someone with the same disability was easier but even if it was a different disability they could support PWD to overcome emotional stress. The COO also expressed that it depends on the type of support that the PWD needs and that a peer supporter with a disability could assist any PWD as it created a unique emotional connection and opportunity to support the PWD.

In answering question 1d it was difficult to determine if the tasks on the list of roles and responsibilities were designed with people with disabilities in mind, or if it was designed for able-bodied or both. The main restrictions seemed to be having the correct assistive device for the terrain and accessibility to the community, which could be mitigated by planning visitations and minding the weather. An important element is that the programme theory is built on the premise that a PWD will be able to better support a PWD as compared to someone that does not have a disability. So even if an able-bodied person would be to fulfil the roles and responsibilities the peer supporter with a disability would be a better fit according to the programme theory of HAPD.

Process Evaluation Question 2

a. How many home visitations have the peer supporters done in the communities they serve? To explore the details of the home visitations this section below describes the age, gender, race, the frequency of visitations, and a summary of the amount home visitations.

There were 608 usable entries for home visitations; this included a combination of first visitations for the year and re-visitation(s). 48% of the home visitations were new visitations for the year, i.e. new clients (N=290). This sample was used in the description of age, gender. Table 8 below is a summary of the details of the first home visitations.

Table 8

Age, Gender and Race of New Clients

| Category | Age | Gender | Race |

| Amount | 42 Years Average

(SD = 16,4). Male 39 Years, (SD = 17). Female 43 Years, (SD= 18). |

62% Male, 38% Female. | 76% Coloured, 24% African. |

Note. N=290. New clients as indicated on the client management tool.

62% of first visitation were male and 38% female, 76% were coloured and 24% African. The average age for fist visitations was 42 years (SD = 16.4), average age for males was slightly younger at 38 years, (SD = 15.7) and females almost the same at 43 years, (SD = 18).

The number of times a name was added to the client management tool allowed the evaluator to determine how many times a PWD was visited. There were 344 first visitations for the year, but 290 of those were indicated as new clients. Thus 54 clients were clients before March 2016 and were re-visited, thus it was a first visitation for the year, but not a new client. Table 9 reflects the frequency and percentage of home (re)-visitations for the year.

Table 9

Frequency and Percentage of Visitations and Re-Visitations

| Category | Frequency | Percentage |

| One Visitation | 344 | 56.6 |

| Two Visitations | 133 | 21.9 |

| Three Visitations | 74 | 12.2 |

| Four Or More Visitations | 57 | 9.4 |

| Total | 608 | 100 |

Note. N=608.

Around 57% of the PWD received one visitation. 43% of the home visitations received two or more visitations and 23% received three or more home visitations. 9% received four or more home visitations. As the follow-up section of the client management tool was not completed it was not possible to explore why the PWD were seen more than once.

b. How many client needs were identified by peer supporters.It is interesting to note that 23% of the visitations had no need identified. Please refer to Table 5 which represents the percentage of need identified for all home visitations. Table 10 below excludes the ‘no needs identified’ category. “No need identified” could mean that there was no actual need, or the home visitation notes were not complete, or the PWD did not provide information.

As the ‘no needs identified’ category was not considered it decreased the sample to 433, table 10 shows the distribution where all home visitations have a need identified.

Table 10

Needs Categories – Excluding “No Needs Identified” category

| Health & Wellness | Housing & Transport | Social & Family Issues | Education & Employment | |

| Percentage | 39% | 24% | 21% | 16% |

Note: N = 433

The needs categories remain in the same order after the “no needs identified” was removed. All the percentages increase by +-5% only the Health & Wellness needs increased by 10%, from 29% to 39% of the selection. Please refer to table 1 for the details on the different needs in the categories.

Proximal Outcome Evaluation Question 3

3. Was the programme better able to meet the needs of certain types of disabilities or needs categories? As a reminder, a meetable need in this evaluation is a need that the peer supporter should be able to provide support in. Support would include mainly be providing information, emotional support, and/or other support in alleviating the need within their scope of work and training. Table 11 represents the frequency and percentage of meetable and unmeetable needs of the PWD that had needs identified.

Table 11

Percentage of Meetable vs Unmeetable needs

| Meetable | Unmeetable | |

| Frequency | 315 | 118 |

| Percentage | 73% | 27% |

Note: N = 433

73% of the needs identified were meetable. This is a high percentage, the assumptions is that according to their roles and responsibilities and training, the peer supporter should be able to, at least, provide information regarding their need. This caused many of the needs to be meetable as providing information would be a relatively straightforward task. The unmeetable needs include the needs where providing information or emotional support could not meet the need or help the PWD. Please see Table 3 for more details on meetable and unmeetable needs.

The following sections explore the association between a (un)meetable need and the category of disability or the category of need the PWD had.

Disability category and meetable needs. To explore if a (un)meetable need was associated with any type of disability category it was compared in a joint frequency distribution also called a cross-tabulation (Michael, 2001). This cross-tabulation contains the number of cases that fall into each combination of categories. The categories have to have enough observations in each category to be considered (Field, 2013). The psychiatric disability category had too few entries and was not considered. Table 12 represents the top 3 disability categories that had sufficient amount of entries to do the croos-tabulation on SPSS 24.

Table 12

Top Three Disability Categories

| Physical | Sensory | Intellectual | Total | |||||||

| Frequency | 359 | 35 | 30 | 424 | ||||||

| Percentage | 85% | 8% | 7% | 100% | ||||||

Note: N=424. Psychiatric disability not considered as it only had 9 entries.

The crosstabulation and Chi-square test of independence was run on SPSS 24 to determine whether the (un)meetable needs were statistically independent or if they were associated with the different need or disability categories (Michael, 2001). Table 13 represents the cross-tabulation of disability categories with the meetable or unmeetable need categories. Percentages and observed count vs expected count was included to calculate odds ratios if the association was significant.

Table 13

Cross-tabulation Meetable and Unmeetable needs in different Disability Categories.

| Physical Disability | Sensory Disability | Intellectual Disability | Totals | |

| Meetable Need* | 75%

(269 vs 266) |

74%

(26 vs 26) |

63%

(19 vs 22) |

314 |

| Unmeetable Need* | 25%

(90 vs 93) |

26%

(9 vs 9) |

37%

(11 vs 8) |

110 |

| Totals | 359 | 35 | 30 | 424 |

Note. N = 424.

χ 2 = 1.94, df =2. p < .379.

*Percentage and (Observed vs Expected Count).

There was a non-significant association between the type of disability identified and if the need was meetable χ2 (2) = 1.94, p < .379. The type of disability that the PWD had was not associated to the PWD having a meetable or unmeetable need. The peer supporters were just as likely to provide support to a person with a physical disability, sensory disability, or intellectual disability.