The Impact of Perceived Risk on Perceived Value and Purchase Intention in E-commerce

Info: 28986 words (116 pages) Dissertation

Published: 22nd Feb 2022

Tagged: E-commerce

ABSTRACT

In recent years, with the development of the Internet and high-tech services, E-commerce is a potential and fast-growing market in Vietnam, according to reports of eMarketer (2016), Vietnam E-commerce Association (2015), and the E-commerce and Information Technology (2014). In order to maximize the potential E-commerce market of Vietnam, as well as understand the importance of studying the impact of Perceived Risk on Perceived Value and Purchase Intention, the researchers decided to conduct the research. The objectives of this study are to identify the components of Perceived Risk, analyze the relationship Perceived Risk has with Perceived Value and Purchase Intention in E-commerce context, determine whether there is difference in Perceived Risk in terms of gender, and propose some managerial implications to corporations. The research method includes both qualitative research (in-depth interview and focus group) and quantitative research (survey). The sample size of the survey is 400, with respondents are who live in Ho Chi Minh City and have purchased online. The key findings of this paper include that Perceived Risk in E-commerce consists of Perceived Risk associated with Product/Service, Perceived Risk happening during Transaction and Psychosocial Risk. In addition, Perceived Risk has a strong negative effect on both Perceived Value and Purchase Intention. Finally, Male are more aware of Psychosocial Risks than Female. Managerial implications for companies are suggested in Chapter 5 of the paper.

Keyword: Perceived Risk, Perceived Value, Purchase Intention, E-commerce, Ho Chi Minh City.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Click to expand Table of Contents

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

Chapter 01: INTRODUCTION

1.1. Rationale

1.1.1. Background of E-commerce market in Vietnam

1.1.2. Practical Problems

1.2. Research Objectives

1.2.1. General objective

1.2.2. Specific objectives

1.3. Objects

1.4. Research Scope

1.5. Research Questions

1.6. Methodology and Data Overview

1.7. Research Meaning

1.7.1. Academic meaning

1.7.2. Practical meaning

1.8. Research Outline

Chapter 02: LITERATURE REVIEW

2.1. Theoretical Background

2.1.1. Internet and E-commerce

2.1.2. Consumer Behavior

2.1.3. Marketing

2.2. Related Researches

2.2.1. The relationships among perceived quality, Perceived Risk and perceived product value (Snoj, Korda and Mumel, 2004)

2.2.2. A trust-based consumer decision-making model in electronic commerce: The role of trust, Perceived Risk, and their antecedents (Kim, Ferrin and Rao, 2008)

2.2.3. Hotel restaurant co-branding: The relationship of perceived brand fit with intention to purchase (Ashton and Scott, 2011)

2.2.4. Development of a scale to measure the perceived benefits and risks of online shopping (Forsythe et al., 2006)

2.2.5. On the Explanation of Factors Affecting E-Commerce Adoption (Lee, Park and Ahn, 2001).

2.2.6. Predicting E-Services adoption: a Perceived Risk facets perspective (Featherman and Pavlou, 2003)

2.3. Proposed Research Model

2.4. Definitions and Hypotheses

2.4.1. Purchase Intention

2.4.2. Perceived Value

2.4.3. Perceived Risk

2.4.4. Hypotheses

Chapter 3: RESEARCH METHOD

3.1. Research Process

3.2. Research Method

3.1.1. Qualitative Research

3.1.2. Quantitative Research

3.3. Data Collection Methods

3.3.1. Primary Data

3.3.2. Secondary Data

3.4. Sampling Design

3.5.1. Sampling Techniques

3.5.2. Sample Size

3.5. Questionnaire Design

3.4.1. Measurement Scale

3.4.2. Pilot Test

3.6. Data Analysis Methods

3.6.1. Descriptive Statistical Analysis

3.6.2. Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA)

3.6.3. The Reliability of Scale

3.6.4. Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA)

3.6.5. Verification of the research model by Structural Equation Modeling (SEM)

3.6.6. Independent-Samples T-Test

3.7. Ethical Consideration

Chapter 4: DATA ANALYSIS

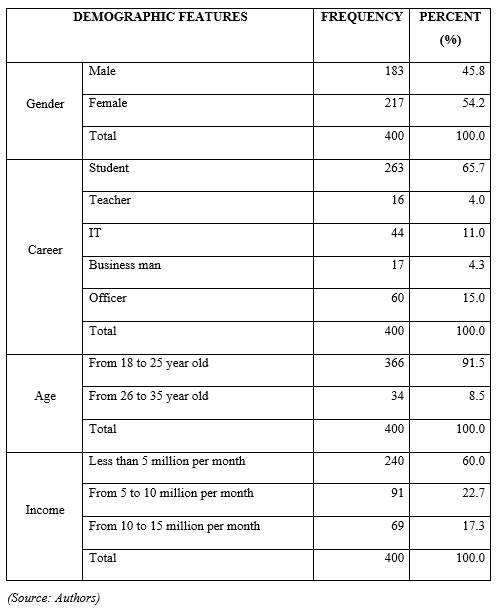

4.1. Sample Demographics

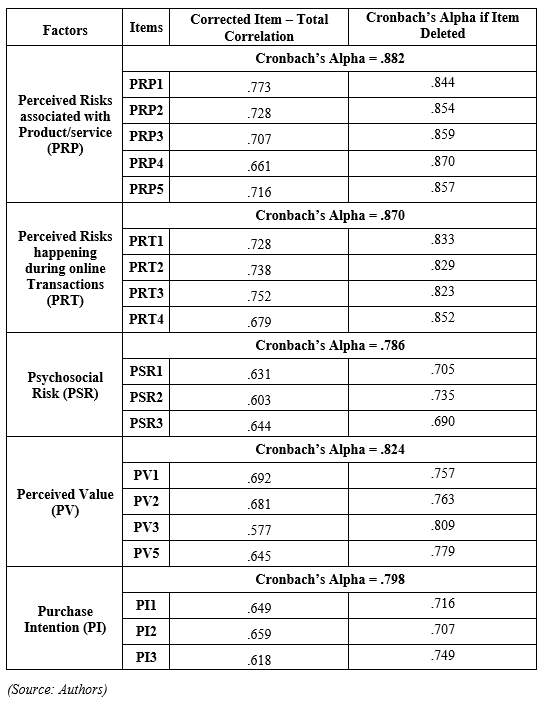

4.2. Scales’ reliability

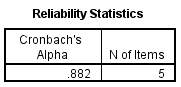

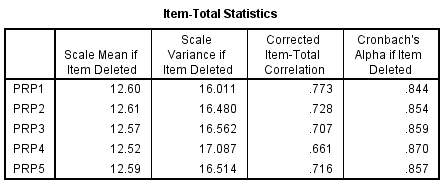

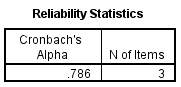

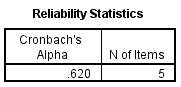

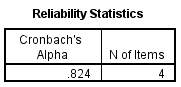

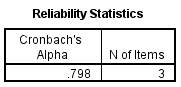

4.2.1. Cronbach’s Alpha: Perceived Risk scales

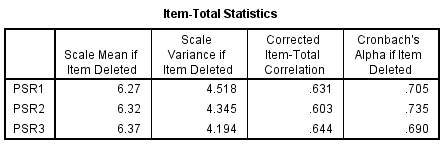

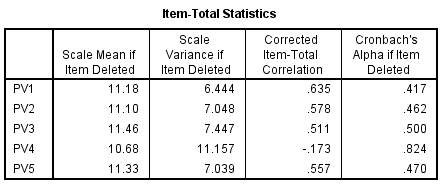

4.2.2. Cronbach’s Alpha: Perceived Value scales

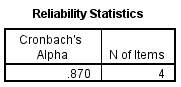

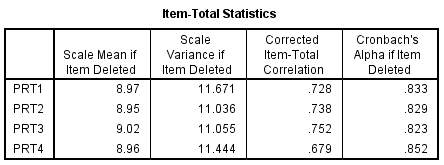

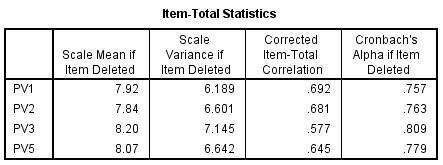

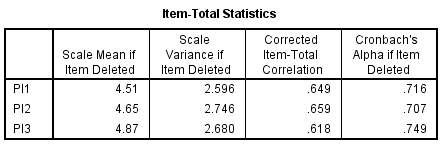

4.3.3. Cronbach’s Alpha: Purchase Intention scales

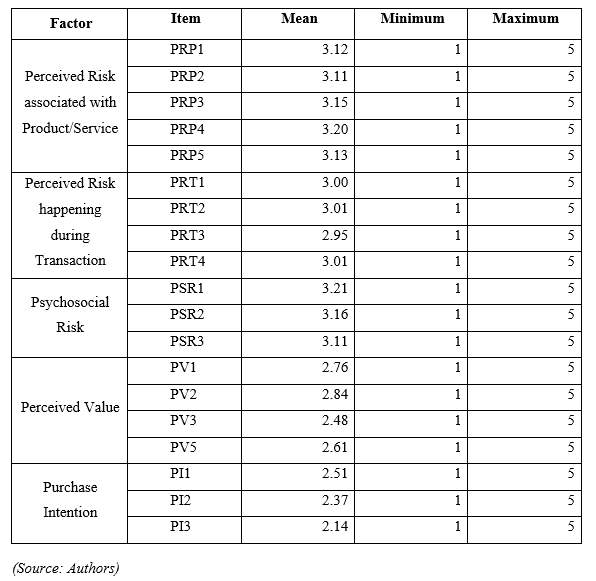

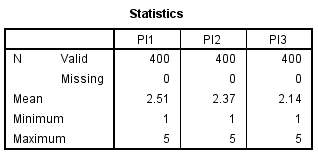

4.3. Descriptive statistics

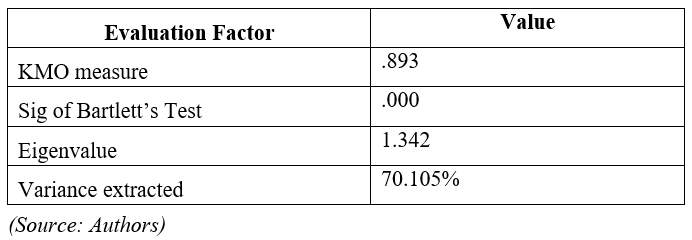

4.4. Principal components and factor analysis

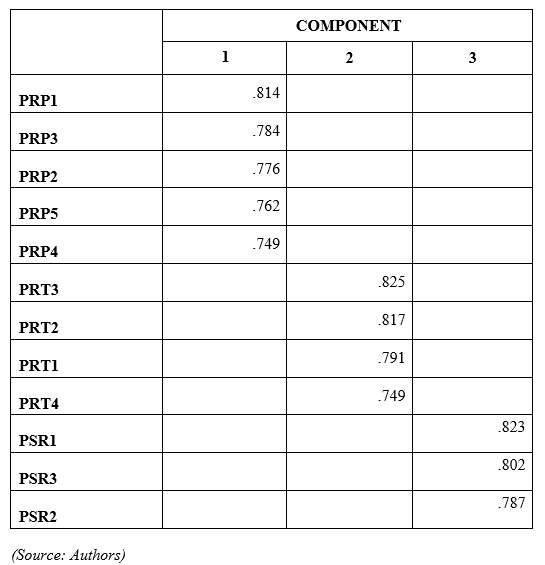

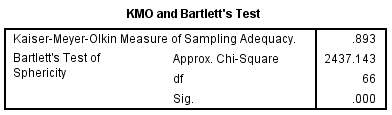

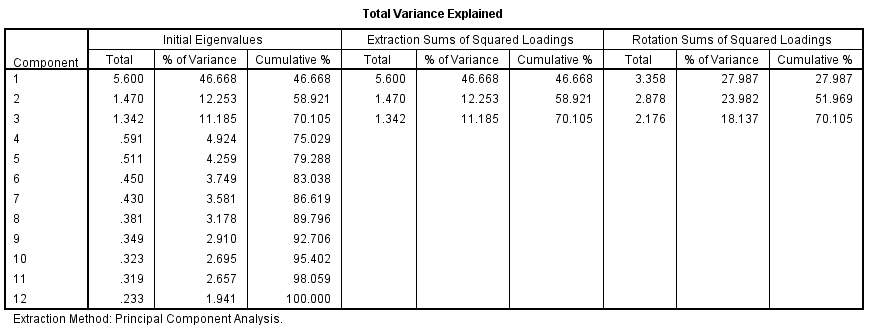

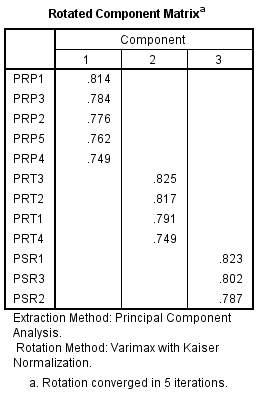

4.4.1. EFA: Perceived Risk scales

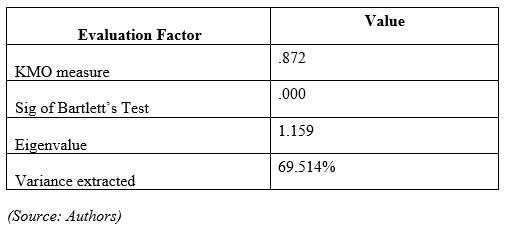

4.4.2. EFA: Perceived Value and Purchase Intention

4.5. Measurement development

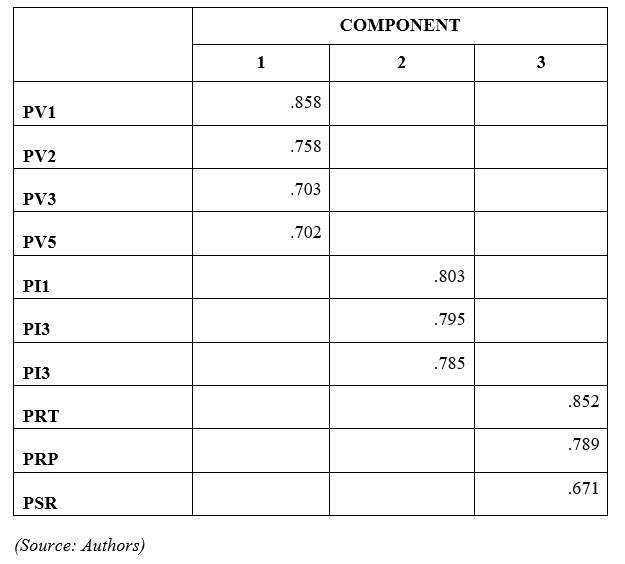

4.5.1. CFA results of the Perceived Risk

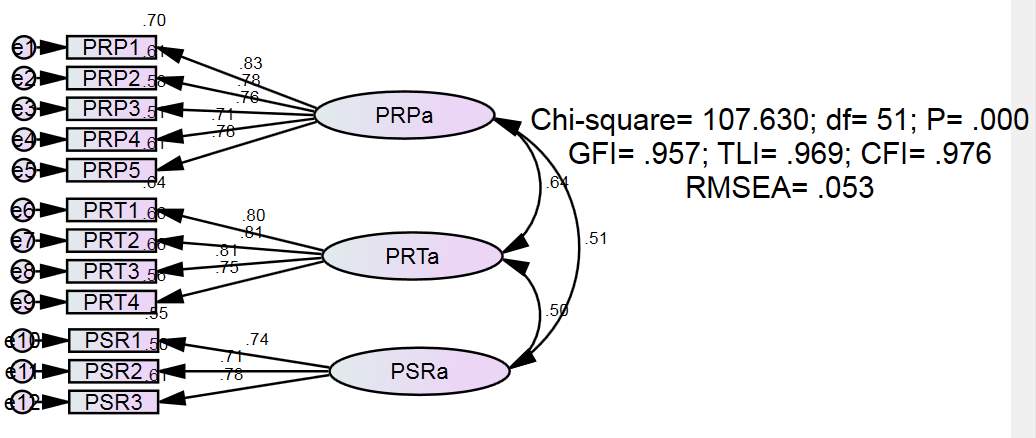

4.5.2. CFA results of the Perceived Value and Purchase Intention

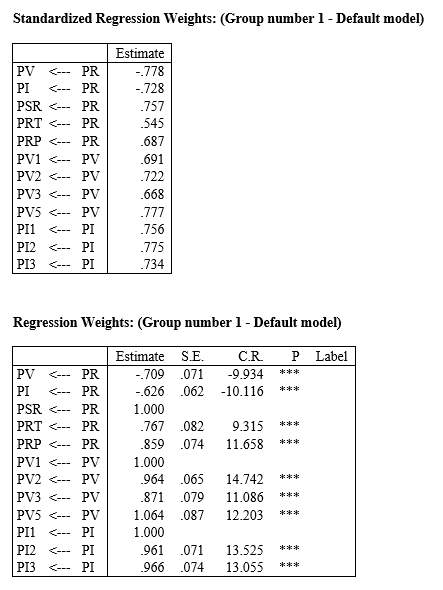

4.6. Verification of research model

4.6.1. Analysis of Perceived Risk theoretical model

4.6.2. Analysis of research model

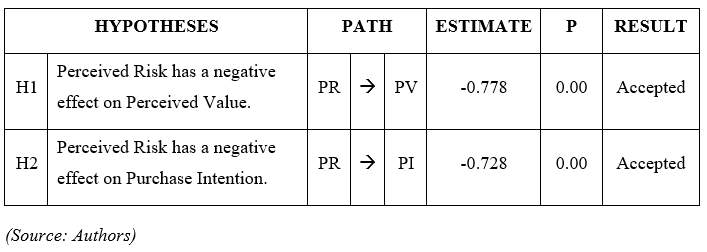

4.6.3. Hypotheses testing

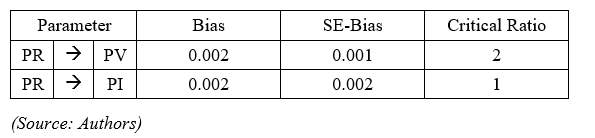

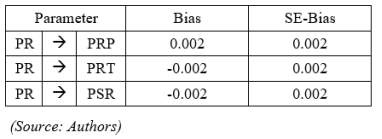

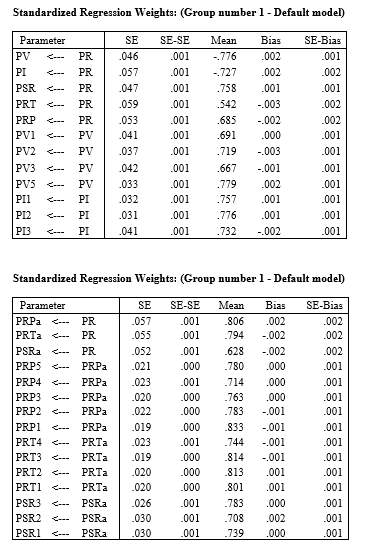

4.6.4. Verification of research model via bootstrap

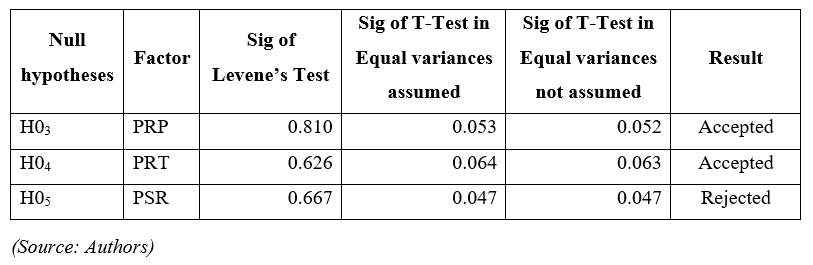

4.7. Other Test related to gender

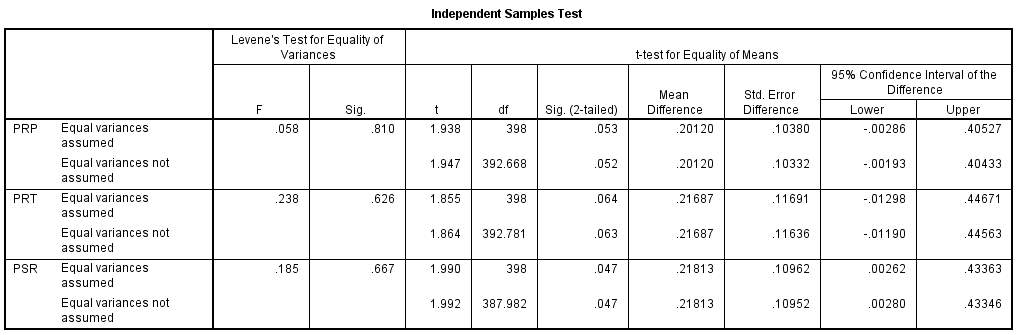

4.7.1. The Perceived Risk associated with Product/Service between male and female

4.7.2. The Perceived Risk happening during Transaction between male and female

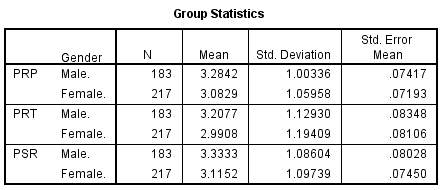

4.7.3. The Psychosocial Risk between male and female

Chapter 5: FINDINGS AND IMPLICATIONS

5.1. Key Findings

5.2. Discussion

5.3. Managerial Implications

5.4. Limitations and Future Research

REFERENCES

APPENDICES

Appendix 1: Questions for in-depth interview

Appendix 2: Questions for focus group interview

Appendix 3: Official Questionnaires

Appendix 4: Pilot Test’s Analysis Results

i. Cronbach’s Alpha test of the scales

ii. EFA of Perceived Risk scales

iii. EFA of Perceived Value and Purchase Intention

Appendix 5: Official Analysis Results

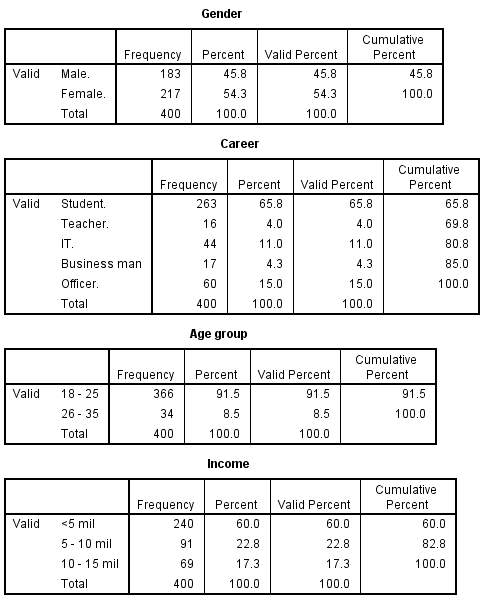

i. Frequency table of sample

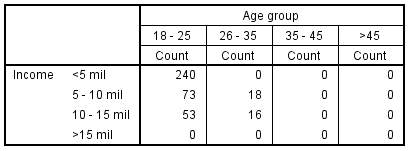

ii. Sample distribution by age group and income

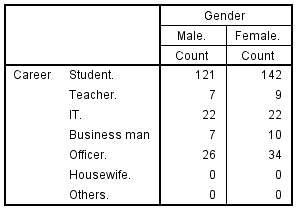

iii. Sample distribution by gender and career

iv. Cronbach’s Alpha of the research factors

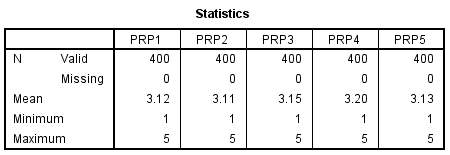

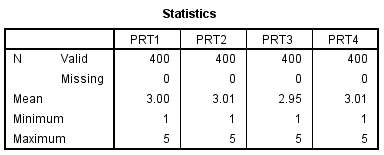

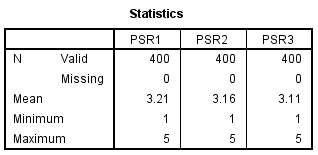

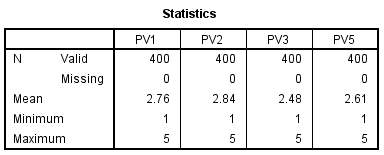

v. Means of the scales

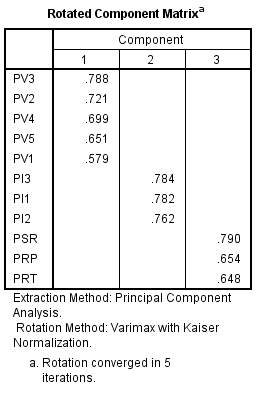

vi. EFA test of the Perceived Risk’s scales

vii. EFA test of the Perceived Risk, Perceived Value and Purchase Intention scales

viii. T-Test of Perceived Risk related to Gender

ix. Hypothesis results

x. Bootstrap results

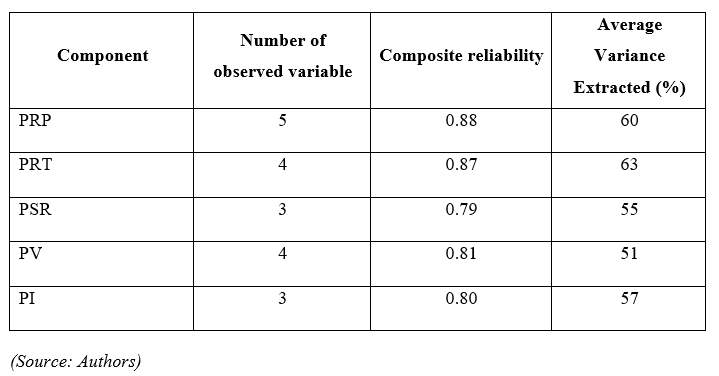

LISTS OF TABLES

Table 2.1. Dimensions of Perceived Risk based on Featherman and Pavlou (2003)

Table 2.2. Perceived Risk Dimensions and Their Concepts Proposed in Marketing and Information System Literature

Table 3.1. The relationship between Quantity and Quality of Sample Sizes

Table 3.2. Measurement Scale

Table 3.3. Cronbach’s Alpha pilot test

Table 3.4. The table summarizes EFA results of Perceived Risk

Table 3.5. Rotated Component Matrix of Perceived Risk

Table 3.6. The table summarizes EFA results of Perceived Value and Purchase Intention

Table 3.7. Rotated Component Matrix of Perceived Value and Purchase Intention

Table 4.1. Respondents’ profile

Table 4.2. Cronbach’s Alpha of the scales

Table 4.3. Descriptive statistics

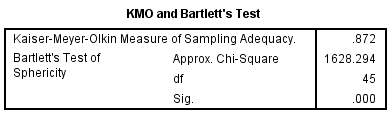

Table 4.4. KMO result of Perceived Risk’s scales

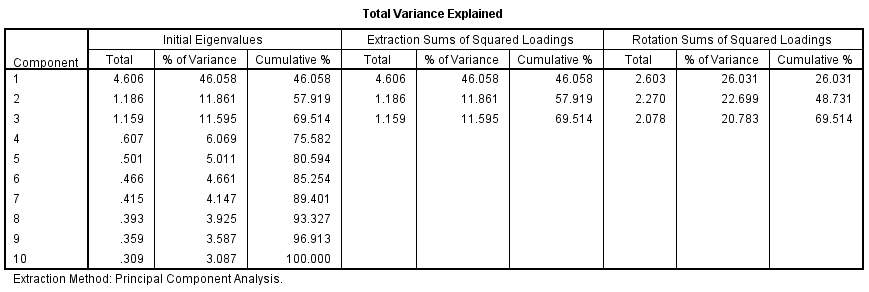

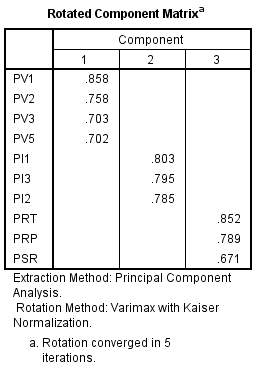

Table 4.5. Principal components of Perceived Risk’s scales

Table 4.6. KMO result of the concept in the research model

Table 4.7. Principle components of research model

Table 4.8. Summary table of test results

Table 4.9. Result for Hypothesized Path Relationships

Table 4.10. Bootstrap’s Result with N = 1000

Table 4.11. Bootstrap’s Result of Perceived Risk theoretical model with N = 1000

Table 4.12. Independent statistics of Perceived Risk between genders

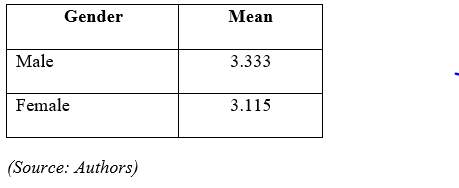

Table 4.13. Means of Psychosocial Risk between male and female

LISTS OF FIGURES

Figure 1.1. Obstacles of online shopping

Figure 1.2. Reasons for no online shopping

Figure 2.1. Conceptual model of relationships among perceived quality, Perceived Risk and perceived product value of the mobile phone (Snoj, Korda and Mumel, 2004)

Figure 2.2. Model of trust-based consumer decision-making in electronic commerce: The role of trust, Perceived Risk, and their antecedents (Kim, Ferrin and Rao, 2008)

Figure 2.3. Research Model of Hotel restaurant co-branding: The relationship of perceived brand fit with intention to purchase (Ashton and Scott, 2011)

Figure 2.4. Conceptual Model to Explain the Role of Perceived Benefits/Risks on Consumers’ Online Perceptions and Shopping Behaviors (Forsythe et al., 2006)

Figure 2.5. Research Model of Factors Affecting E-Commerce Adoption (Lee, Park and Ahn, 2001)

Figure 2.6. Research model of Predicting e-services adoption: a Perceived Risk facets perspective (Featherman and Pavlou, 2003)

Figure 2.7. Proposed Research Model

Figure 2.8. Value hierarchy model (Woodruff, 1997)

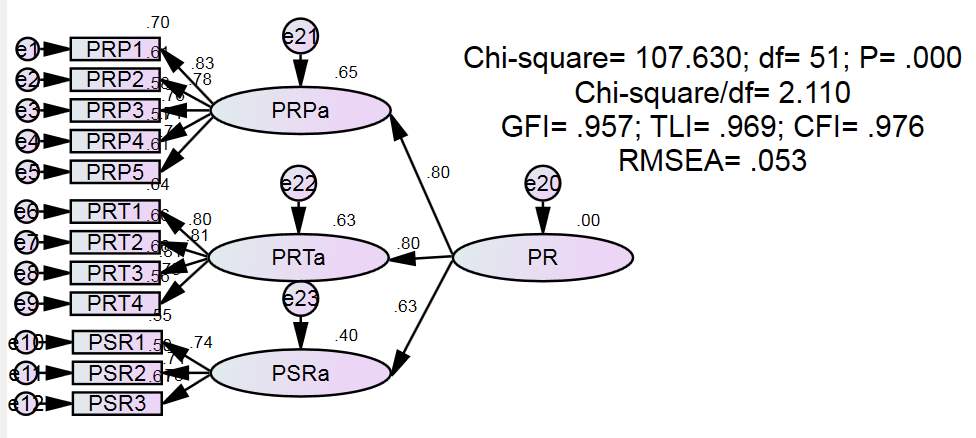

Figure 4.1. CFA results of Perceived Risk (standardize)

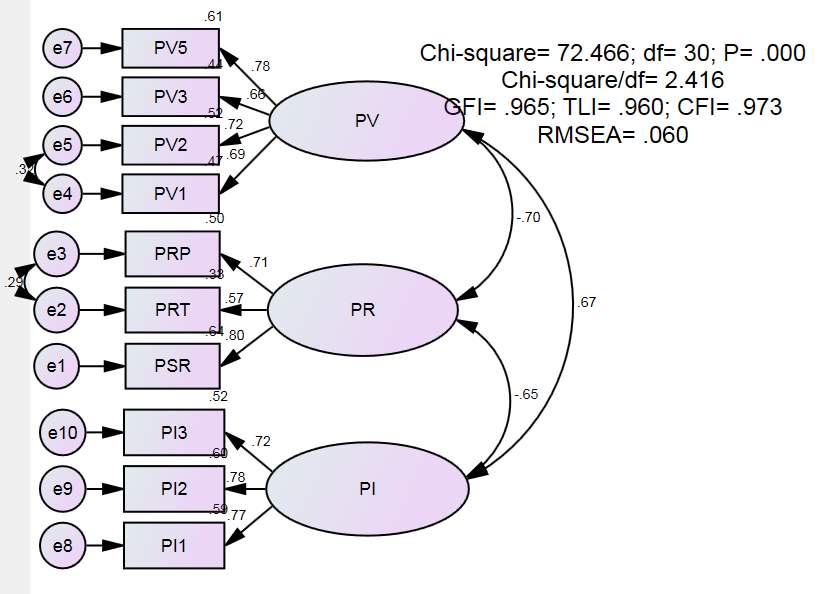

Figure 4.2. CFA results of Perceived Value and Purchase Intention (standardize)

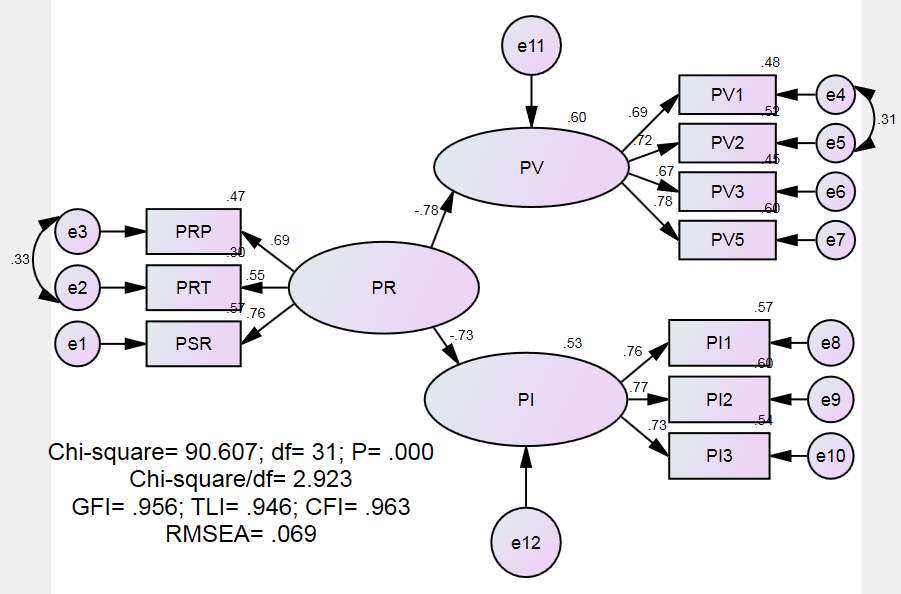

Figure 4.3. Estimated results of the Perceived Risk theoretical model

Figure 4.4. Estimated results of the research model

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

| B2C | Business to Consumer |

| C2C | Consumer to Consumer |

| CFA | Confirmatory Factor Analysis |

| e-CAM | e-Commerce Adoption Model |

| EFA | Exploratory Factor Analysis |

| IP | Internet Protocol |

| KMO | Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin |

| MOIT | Ministry of Industry and Trade of the Socialist Republic of Vietnam |

| SEM | Structural Equation Modeling |

| SPSS | Statistical Package for the Social Science |

| TCP/IP | Transmission Control Protocol/Internet Protocol |

| VECITA | Vietnam E-Commerce and Information Technology Agency |

| VECOM | Vietnam E-Commerce Association |

Chapter 01: INTRODUCTION

This chapter will demonstrate the background of E-commerce market worldwide and in Vietnam. Practical problems of Vietnam E-commerce are also mentioned, which are the rationale for the authors’ choosing the thesis topic. Additionally, the research objectives, research objects, research scope, research questions, methodology and data overview, research meaning and research outline are included in this chapter. These parts will provide a clear guideline for this paper.

1.1. Rationale

1.1.1. Background of E-commerce market in Vietnam

The information technology is developing day by day and its representative is the Internet (Ulrike Schultze, 2002). Because of the global attributes, Internet has profoundly transformed all aspects of human society, especially economy (Bughin et al., 2011). This means that the process of buying, selling or exchanging products, services or information can take place without borders. E-commerce opened up the possibility of reducing transaction costs, and penetrating the potential market. Thereby, the structure of the national economy and the globalization are changed (McMillan, Rodrik and Verduzco-Gallo, 2014).

Moreover, eMarketer (2016) has collected the information that the total worldwide C2C E-commerce retail is about $1,548 billion, more 6.0% than the previous year. While Ecommerce Foundation (2016) also had the data that the global B2C E-commerce turnover was about $2,273 billion, up 19.9% from the 2014. For more details, Asia-Pacific was considered the world largest retail market with nearly $875 billion (increased 35.2%) in C2C market and $1,057 billion (increased 28%) in B2C market.

According to Internet World Stats (2016), in 2016 there are about 49 million Vietnamese using Internet, this number accounts for 51.5 percentage of total Vietnamese. The report of Vietnam E-commerce Association (VECOM) (2015) also forecasted Vietnam E-commerce would reach about $ 20 billion sales in 2020 and growth rate in the period 2016-2020 is expected to reach about 20% per year.

In the Vietnam, E-commerce is also considered new exchange market with many benefits for the enterprises. E-commerce industry includes the prominent brands such as Vatgia.com, Lazada.vn, Adayroi.com, Tiki.vn, Sendo.vn, so the consumers are gradually accustomed to shopping on the website instead of traditional shopping. According to Ministry of Industry and Trade of the Socialist Republic of Vietnam (MOIT) (2014), E-commerce has a rapidly growing step through telecommunications systems booming to about 1/3 of the population of Vietnam Internet access. The percentage of websites that feature online ordering 58%, while the proportion website featuring online payment is 15%.

However, E-commerce does not explode so rapidly because of some barriers. According to Bizweb.vn (2015), wanting to touch the items is considered to be the most common barriers for E-commerce while the potential consumers is worried about the counterfeit and want to receive the products as quickly as possible. Furthermore, Vietnamese consumers still prefer to pay in cash than the other types, which means that they just decided to pay the bill when receiving the goods in hand.

Moreover, based on the survey about people living in Vietnam who has the ability to use the Internet, Google (2015) as cited by Bizweb.vn (2015) declared that 44% of online people who have never online shopped desire to shopping online in the next 12 months.

1.1.2. Practical Problems

Vietnamese E-commerce market is full of potential, yet maximized (Talk Vietnam, 2016). According to Vietnam E-commerce Report conducted in 2015 by VECITA, the result shows that up to 62% of Vietnamese Internet users purchased online, 4% higher than that of 2014 (Figure 1.3). However, the number of online purchasers is just nearly 24.2% of the total Vietnam population. Therefore, there is a big gap in Vietnamese E-commerce market for companies to expand and develop (vietnamnews.vn, 2015).

One of the most noticeable reasons that prevent potential online consumers from joining E-commerce activities is their Perceived Risks (Liebermann and Stashevsky, 2002; Snoj, Korda and Mumel, 2004; Mitchell, 1999). Since E-commerce is a new market and there is not enough reliable information and trust towards the market, consumers are often reluctant when deciding whether to make an online purchase or not (VECITA, 2015; Pallab, 1996; Ko et al., 2004). In the study of Snoj, Korda and Mumel (2004), belief about the potential uncertain negative outcomes from the online transaction is the major barrier for trading online.

In comparison with traditional retail formats, consumers perceive a higher level of risk when purchasing online (Lee and Tan, 2003; Tan, 1999). Various studies have consistently revealed that consumers have higher Perceived Risks in non-store shopping formats, such as telephone shopping (Akaah and Korgaonkar, 1988), mail order (Van den Poel and Leunis, 1999), catalog (Eastlick and Feinberg, 1999), and direct sales (Peterson, Albaum, and Ridgway, 1989).

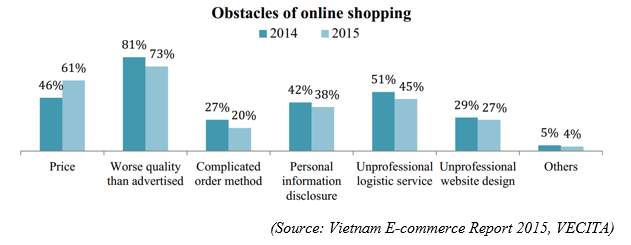

VECITA (2015) has also found out those major obstacles that prevent potential consumers from online shopping was the worse quality than promoted of products or services (73%), the following was price concern (61%) and unprofessional logistics service (45%).

Figure 1.1. Obstacles of online shopping

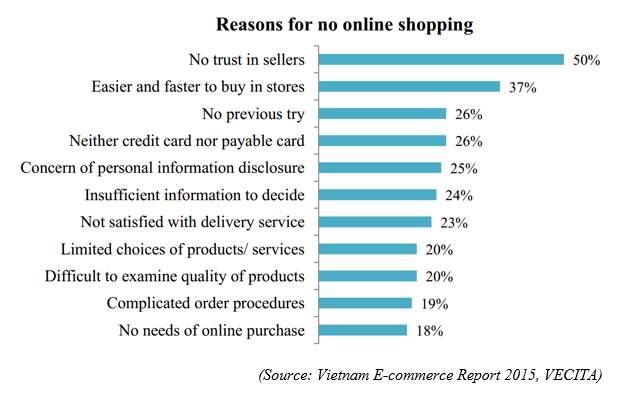

Furthermore, among the 38% of respondents who have never tried online purchases before, half has chosen “no trust in sellers” as their explanations. Following are Finding it faster and easier to buy in stores, Not having credit cards or payable cards, and Having concerns about personal information disclosure to be picked by 37%, 26% and 25% of the respondents respectively.

Figure 1.2. Reasons for no online shopping

According to different authors, consumers’ Perceived Value is considered as a multidimensional concept, which presents a trade-off between benefits and sacrifices perceived by consumers in a supplier’s offering (e.g. Woodruff et al., 1993; Zeithaml et al., 1996; Snoj and Gabrijan, 2000; Slater and Narver, 2000; Ulaga and Chacour, 2001). As Levy, Valenciano and Michal (2009) once stated, retail consumers are “value-driven”, managers should have a deep understanding of what consumer’s value and where they should draw attention to attain this needed market place advantage (Woodruff, 1997).

According to Fishbein and Ajzen (1975), to fully understand purchase behaviors, it is essential to analyze Purchase Intention. The intention is the best tool to predict behaviors since one’s action is measured by their intentions in doing that action. Purchase Intention is the most concerned issue among companies and retailers who have the idea of joining E-commerce market because Purchase Intention can support them in comprehend consumers’ behaviors and their acknowledgment about the products (Magistris and Gracia, 2008).

Understanding consumers’ Perceived Risk is of great concern to managers (Kalakota and Whinston, 1996). However, according to Macintosh (2002), Perceived Risk is the least studied concept of sacrifices. In Vietnam, there are few types of research focusing on Perceived Risk and its impact on Perceived Value and Purchase Intention of consumers, especially in E-commerce, which is a new trend in recent years. Additionally, despite value’s importance, relatively little empirical research has been conducted to develop an in-depth understanding of the factors influencing Perceived Value and Purchase Intention of consumers. There is a need to have a research studying the influences of Perceived Risk on Perceived Value and Purchase Intention of Vietnamese consumers.

Therefore, researchers have decided to conduct this research to study “The impact of Perceived Risk on Perceived Value and Purchase Intention in E-commerce: Case study on Ho Chi Minh City”.

1.2. Research Objectives

1.2.1. General objective

The main purpose of this research is to understand how Perceived Risk affects Perceived Value and Purchase Intention in E-commerce of consumers in Ho Chi Minh City. By doing quality and quantity research, the research will point out the components of Perceived Risk, which can be used to measure Perceived Risk’s effect on Perceived Value and Purchase Intention of consumers. Based on the collected and measured data, the relationship between Perceived Risk, Perceived Value and Purchase Intention will be analyzed. It will help enterprises understand more about their consumers to optimize their business process, and capture more value from consumers in the E-commerce market.

1.2.2. Specific objectives

- Identify components of Consumers’ Perceived Risk in E-commerce, case in Ho Chi Minh City.

- Identify the influences of Perceived Risk on Perceived Value and Purchase Intention in E-commerce context.

- Identify whether there is any difference in Perceived Risk based on gender.

- Propose solutions to increase Perceived Value, Purchase Intention, and decrease Perceived Risk of consumers in E-commerce in Ho Chi Minh City.

1.3. Objects

The three objects of this paper are Perceived Risk, Perceived Value and Purchase Intention of Consumers in E-commerce context in Ho Chi Minh City.

1.4. Research Scope

This study focuses on Consumers who live in Ho Chi Minh City and have experiences in purchasing online. The research subjects are students, workers, and officers, aged between 18 and 35. The survey is conducted in two weeks with the results of 400 valid samples in the end.

- Research place: Ho Chi Minh City (District 1, 3, 12, Tan Binh).

- Research time: 01/01/2017 – 15/04/2107.

- Official survey time: 01/03/2017 – 14/03/2107.

1.5. Research Questions

Our research questions to gain the research objectives are:

- What are components of Consumers’ Perceived Risk in E-commerce?

- How does Perceived Risks affect Perceived Value and Purchase Intention in E-commerce?

- Is there any difference between male and female in Perceived Risk?

- How should corporations improve Perceived Value, Purchase Intention, and reduce Perceived Risk of consumers in E-commerce?

1.6. Methodology and Data Overview

To get answers for research questions mentioned above, qualitative methods (in-depth interview and focus group) and quantitative method (survey) are applied. All of the research results are based on analyzing collected data, including primary and secondary data.

Primary data were collected through in-depth interview, focus group interview and survey conducted in Ho Chi Minh City. In-depth interview is carried out with an expert of Vat Gia Corporation. After that, the authors conducted a focus group interview with eight participants in FPT University Campus Ho Chi Minh City who had purchased online. After carrying out and analyzing the pilot test of 60 samples, the researchers collected 400 valid samples of official questionnaire from consumers who already purchased online in District 1, 3, 12, and Tan Binh.

Secondary data were collected through journal articles, newspapers, books, conference proceedings, televisions and reports from governments or reliable organizations.

The software of IBM SPSS 20 and IBM AMOS 22 are used to analyze and process the data. Data analysis methods include descriptive statistical analysis, Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA), testing the Reliability of Scale by using Cronbach’s Alpha, Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA), Verification of the research model by using Structural Equation Modeling (SEM), and Independent-Samples T-Test. Finally, the authors will give out some appropriate managerial implications based on the study’s findings, which are expected to be valid and reliable through proper methods above.

1.7. Research Meaning

1.7.1. Academic meaning

The thesis reinforces the relationship between Perceived Risk versus Perceived Value and Purchase Intention. In addition, the authors also implement factors critical to the research model. Moreover, a new model of E-commerce is introduced in Ho Chi Minh City.

1.7.2. Practical meaning

Based on the basis of the model and the hypothesis built into the framework of this study, the research will help companies better understand the impact of Perceived Risk on Perceived Value and Purchase Intention. Besides that, the group of authors also analysis and evaluates the influence of the elements in the model in Ho Chi Minh City. Since then, the solutions have been proposed to create the basis for E-commerce companies to understand the market.

1.8. Research Outline

This paper includes five Chapter with main content as follows:

Chapter 1: Introduction

This chapter provides general information about Global and Vietnam E-commerce market, which leads to the topic rationale, research objectives, scope, research question, research meaning and thesis outline.

Chapter 2: Literature Review

This chapter describes key concepts and related researches, which are the basis for the proposed model. The hypotheses development is also provided in this chapter.

Chapter 3: Methodology

The methods to conduct this study, which includes Research Process, Research Approach, Data Collection Methods, Questionnaire Design, Sampling Design, Data Analysis Methods, and Ethical Consideration, is presented in this chapter.

Chapter 4: Data Analysis

Research results and data analysis are demonstrated in this chapter. Collected data is analyzed and discussed by using Descriptive Statistical Analysis, Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA), testing the Reliability of Scale by using Cronbach’s Alpha, Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA), Verification of the research model by using Structural Equation Modeling (SEM), and Independent-Samples T-Test.

Chapter 5: Findings and Implications

This section discusses the key findings, which clarify the research questions, and gives out implications for managers. The limitations of the paper and suggestions for future research are also mentioned.

Chapter 02: LITERATURE REVIEW

In this chapter, the theoretical background including definitions of Internet and E-commerce, Consumer Behavior, and Marketing is displayed. In addition, researches related to Perceived Risk and its relationship with Perceived Value and Purchase Intention are selected and played as the basis for the proposed research model. The definitions and appropriate modifications of research objects are then discussed. Finally, hypothesized relationships between Perceived Risk and Perceived Value and Purchase Intention in E-commerce context are introduced.

2.1. Theoretical Background

2.1.1. Internet and E-commerce

Internet

In the Oxford Dictionary (2015), Internet is defined as a worldwide computer network, which comprises interconnected networks using standardized communication protocols to supply a diversity of information and communication readiness.

For further details, since 1995, Resolution of the U.S. Federal Networking Council has propounded the definition of the Internet, which is accepted by many researchers and organizations (Kahn and Cerf, 1999). The Federal Networking Council announced that Internet was the global information system with three factors. Firstly, the Internet is logically connected together by a globally sole address space based on the Internet Protocol (IP) or its subsequent extensions/follow-ons. Secondly, it can support communications by using the Transmission Control Protocol/Internet Protocol (TCP/IP) suite or its subsequent extensions/follow-ons, and/or other IP-compatible protocols. Finally, this global information system also provides, uses or makes accessible, either publicly or privately, high-level services layered on the communications and related infrastructure described.

E-commerce

According to World Wide Web Foundation (2017), since Tim Berners-Lee invented the World Wide Web in 1990, organizations and individuals have actively exploit, develop it. Businesses find World Wide Web helped them a lot in the display, providing and sharing information, contact partners quickly, conveniently and economically. Since then, businesses and individuals across the world have actively exploit the strengths of the Internet, World Wide Web to do the business, which forms the definition of e-commerce. Internet and Web is the main tool of the E-Commerce and help E-Commerce developing and operating effectively. For example, the company Netsscape launched the software application to extract information on the Internet in May 1995. Moreover, the company Amazon.com was launched in May 1997. Furthermore, the company IBM also launched an ad campaign for the business model electronic sales in 1997.

According to Clarke (2000), the principle of Australian National University E-commerce is defined as the conduct of commerce in goods and services, with the assistance of telecommunications and telecommunications-based tools. Following the E-commerce and Development Report 2001 (2001), E-commerce was considered as the sale or purchase of goods or services, whether between businesses, households, individuals, Governments and other public or private organizations, conducted over the Internet. The goods and services were ordered over the Internet, but the payment and the ultimate delivery of the good or service may be conducted on- or offline.

Moreover, academic definitions are narrowed and focused on applications and business supports. For example, Zwass (1996) defines E-commerce as using many means of telecommunication networks to share the business information, converse business relationships and conduct business transactions. Others (Applegate, 1999, Fellenstein and Wood, 2000) also support this view and consider E-commerce to include various processes within and outside the organization in addition to buying and selling activities.

2.1.2. Consumer Behavior

Consumer behavior is the study of individuals, groups, or organizations and the processes they use to select, secure, use, and dispose of products, services, experiences, or ideas to satisfy their needs and wants. It is also concerned with the social and economic impacts of purchasing and consumption behavior on both the consumer and wider society (Kuester and Sabine, 2012).

It is worth noting that consumer buying behavior is studied as a part of marketing and its main objective is to learn the way how the individuals, groups or organizations choose, buy, use and dispose the goods and the factors such as their previous experience, taste, price and branding on which the consumers base their purchasing decisions on (Kotler, 2014).

Factors Affecting Consumer Behavior

There is a wide range of factors that can affect consumer behavior in different ways. These factors are divided by Hoyer, Pieters and MacInnis (2013) into four broad categories: situational, personal, social and cultural factors.

Situational factors influencing consumer behavior may include location, environment, timing and even weather conditions (Hoyer, Pieters and MacInnis, 2013).

Personal factors, on the other hand, include taste preferences, personal financial circumstances and related factors. The impact of personal factors on consumer decision-making is usually addressed by businesses during market segmentation, targeting and positioning practices by grouping individuals based on their personal circumstances along with other criteria, and developing products and services that accommodate these circumstances in the most effective manner (Hoyer, Pieters and MacInnis, 2013).

Social factors affecting consumer behavior arise as a result of interactions of perspective consumers with others in various levels and circumstances. Targeting members of society perceived as opinion leaders usually proves effective strategy when marketing products and services due to the potential of opinion leaders to influence behavior of other members of society (Hoyer, Pieters and MacInnis, 2013).

Hoyer, Pieters and MacInnis (2013) also stated that cultural factors affecting consumer behavior are those related to cross-cultural differences amongst consumers on local and global scales. Culture can be defined as “the ideas, customs, and social behavior of a particular people or society” (Oxford Dictionaries | English, 2017) and the tendency of globalization has made it compulsory for cross-cultural differences amongst consumers to be taken into account when formulating and communicating marketing messages.

2.1.3. Marketing

There are many different concepts of marketing, depending on the actual situation and perception; many researchers have dissimilar ways to define marketing (Arndt, Angelmar and Hunt, 1983; Burnett, 2008). The disparity is not only in the level of details but also in the contents. Over time, the term marketing is adverted in many fields. Today, in the light of science and technology, management level and advanced level of modern industry, there is the appearance of modern marketing (American Management Association, 2017). According to this new view, marketing activities have gradually. It develops in both quantity and quality, explaining more properly the meaning it contains (Burnett, 2008).

According to Kotler and Armstrong (2012), marketing is considered as the process by which consumers receive the value created by the companies while these companies try to build strong relationships with their consumers to get the return. In addition, Aaker (2004) and his colleagues also define the “marketing” term as the activity, set of institution and process for creating, communicating, delivering and exchanging offering that create value for consumers, clients, partners and society at larger. On the other hand, basing on the viewpoint of organization Perreault et al. (2010) said that marketing is the process of carrying out activities to achieve the goals of the organization by anticipating the needs of consumers or consumers to control the flow of goods and services that meet the needs of the producer to consumers or consumers

In other words, marketing can be also understood as the economic and social mechanism that organizations and individuals use to satisfy their needs and wants through the process of exchanging products on the market (Thai, 2017).

2.2. Related Researches

2.2.1. The relationships among perceived quality, Perceived Risk and perceived product value (Snoj, Korda and Mumel, 2004)

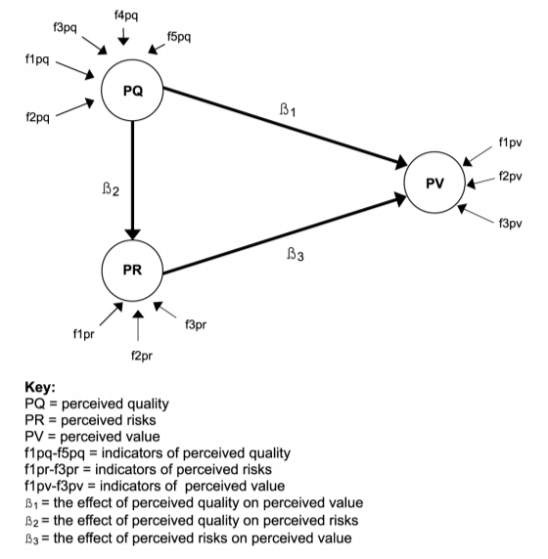

Snoj, Korda and Mumel did a research on the relationships among perceived quality, Perceived Risk and perceived product value in 2004 in Slovenia. Perceived Value is a critical concept in marketing and many researchers have studied about it of late, however, not in Slovenia. Therefore, Snoj, Korda and Mumel decided to research the influences of individual factors on Perceived Value of a product, which happened to be mobile phones. The inquired target group was students – the quickest developing segment among the users of cell phones in Slovenia.

In their research, the researchers concentrated on two of the Perceived Value impact factors: perceived product quality and Perceived Risk. Based on literature and research findings, their fundamental researched objective was to design the model of connections among Perceived Value, perceived quality and Perceived Risk. After the model had been examined with the method of LISREL 8.0, the researchers found that, among the concepts researched, statistically significant relationships do exist.

In particular, the perceived quality of a cell phone positively affects the Perceived Value. Meanwhile, the Perceived Risks of a cell phone affect adversely on the Perceived Value. In addition, the perceived quality of a cell phone negatively affects the Perceived Risks. The authors’ findings emphasize the close relationship between Perceived Risks and Perceived Value and how risks can be utilized theoretically and practically in creating perceptions of Perceived Value.

Figure 2.1. Conceptual model of relationships among perceived quality, Perceived Risk and perceived product value of the mobile phone (Snoj, Korda and Mumel, 2004)

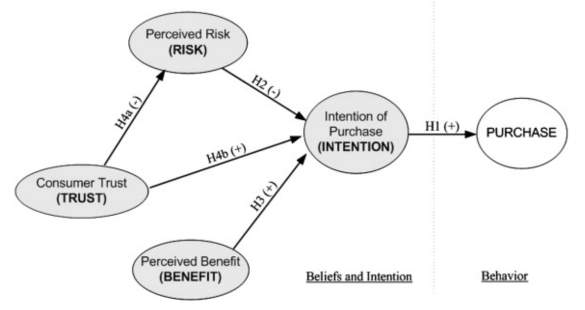

2.2.2. A trust-based consumer decision-making model in electronic commerce: The role of trust, Perceived Risk, and their antecedents (Kim, Ferrin and Rao, 2008)

According to Kim, Ferrin and Rao (2008), trust and risk play a vital part in consumers’ E-commerce purchasing decisions. To examine the antecedents of trust and risk in E-commerce, as well as to understand how an Internet consumer’s buying decision can be affected by trust and risk, these authors have developed a hypothetical framework describing the trust-based decision-making process a buyer applies when making a purchase from a website. In order to testify the proposed model in the paper, authors made use of Structural Equation Modeling procedure on Internet consumer purchasing behavior data that are gathered by means of a Web survey.

The outcomes of the study demonstrate that Internet consumers’ trust and Perceived Risk have profound influences on their purchasing decisions. Internet consumers’ trust in the Website is deeply affected by consumer disposition to trust, reputation, privacy concerns, security concerns, the information quality of the Website, and the company’s reputation. Fascinatingly, the presence of an outsider seal did not strongly affect consumers’ trust.

The empirical consequences recommend that a consumer’s trust directly and indirectly influence his or her buying intention. A consumer’s trust has a solid constructive impact on the purchasing intention as well as a solid destructive impact on a consumer’s Perceived Risk. Moreover, the paper provides confirmation that a buyer’s Perceived Risk diminishes the consumer’s purchasing intention, while a consumer’s perceived benefit rises the consumer’s intention of purchase. In addition, the effects of trust, Perceived Risk, and perceived benefit on Purchase Intentions eventually had a “downstream” influence on consumers’ actual buying decisions. Hence, the discoveries confirm the contention that a consumer’s trust is a vital element in electronic, “cyber” transaction decision, and thus the extended version of the valence framework is supported. Lastly, the outcomes show that there are two ways to address the risk issues in E-commerce, resulted from trust to a large degree: by decreasing Perceived Risk and by expanding Purchase Intentions specifically (trust was the strongest indicator of the online shopper’s Purchase Intention, followed by perceived benefit and Perceived Risk respectively).

Figure 2.2. Model of trust-based consumer decision-making in electronic commerce: The role of trust, Perceived Risk, and their antecedents (Kim, Ferrin and Rao, 2008)

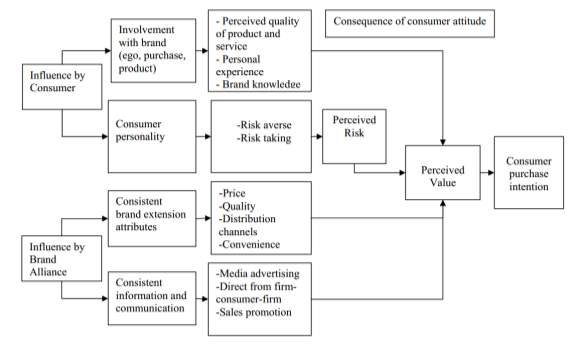

2.2.3. Hotel restaurant co-branding: The relationship of perceived brand fit with intention to purchase (Ashton and Scott, 2011)

A research on the influence of perceived brand fit on intention to purchase in the context of Hotel restaurant co-branding was conducted in 2011 by Ann Suwaree Ashton and Noel Scott. The drive of the applied paper is to build up an understanding the part of consumer assessment of hotel restaurant co-branding and study how this influences Purchase Intention. Advanced from the current co-branding literature, a theoretical model of hotel restaurant co-branding is delivered. The model portrays the relationship between consumer Perceived Risk and Perceived Value and their impact on consumer intention to buy.

The conclusions of the consumer valuation of hotel restaurant co-branding are impacted by both consumer characteristics and the nature of the brand cooperation. From the consumer standpoint, an essentially influential feature is the connection with the brands (consumer collected brand information) which is developed from past involvement. The nature of the brand cooperation and the consistency of brand extension traits are also elements that affect the consumer assessment result.

The theoretical model displays two groups of features that impact Purchase Intention, first, influences from the consumer viewpoint and second, impacts from a brand coalition view. Both groups of features are antecedents to Perceived Risk and Perceived Value. The purchaser perspective includes both the level of involvement with brand and the shopper personality. Consumers will intent to (re)purchase the item relying on high or low connection with the brands comprising sense of self-contribution, purchase involvement, and item connection (Dowling and Staelin, 1994). Briefly, the evaluation consequence from consumers towards the hotel restaurant co-branding is Perceived Risk, Perceived Value and Purchase Intention, and the elements affecting this conclusion are resulting from consumer personality and the perception of the brand.

Perceived brand fit between two brands is a result of consumers assessing a brand on Perceived Value, Perceived Risk, satisfaction, and intention to purchase, loyalty and image transfer. The relationships between partner qualities, inspiration, and consumer attributes are crucial in the procedure of achieving a constructive perception of brand cooperation. Subsequently, the consumer assessment of hotel restaurant co-branding influences buying intention.

Figure 2.3. Research Model of Hotel restaurant co-branding: The relationship of perceived brand fit with intention to purchase (Ashton and Scott, 2011)

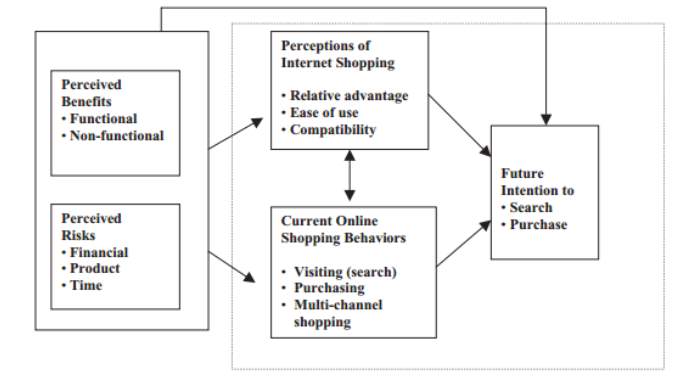

2.2.4. Development of a scale to measure the perceived benefits and risks of online shopping (Forsythe et al., 2006)

In 2006, Sandra Forsythe, Chuanlan Liu, David Shannon, and Liu Chun Gardner carried out a study on the developing a scale which measures the perceived benefits and Perceived Risks related with online shopping. By applying exploratory qualitative inquiry and quantitative assessment, a four-factor scale of perceived benefits (Shopping Convenience, Product Selection, Ease/ Comfort of Shopping, and Hedonic/ Enjoyment) and a three-factor scale of Perceived Risks (Financial Risk, Product Risk, and Time/ Convenience Risk) of online shopping were created. Results from two national samples endorse the proposed measures of perceived benefits and risks that are related with online shopping.

The findings uncovered that those consumers who shopped more regularly and spent more money online perceived greater benefits and less risk to be related with online shopping. Additionally, perceived benefits were a positive predictor of future intentions to visit and purchase on the Internet, whereas Perceived Risks related adversely to future online Purchase Intentions. Finally, a practical evaluation of these scales revealed that people purchasing (as opposed to just visiting) online perceived considerably greater benefit and less risk, and that heavy online consumers (comparing with light ones) perceived considerably greater benefits in terms of shopping convenience and product selection.

Figure 2.4. Conceptual Model to Explain the Role of Perceived Benefits/Risks on Consumers’ Online Perceptions and Shopping Behaviors (Forsythe et al., 2006)

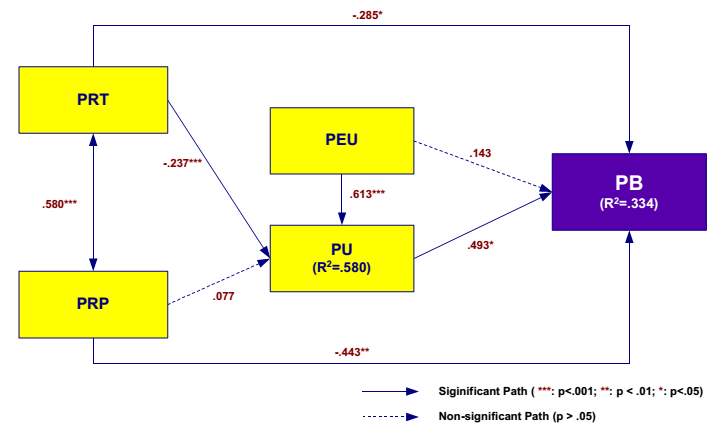

2.2.5. On the Explanation of Factors Affecting E-Commerce Adoption (Lee, Park and Ahn, 2001).

In 2001, Dongwon Lee, Jinsoo Park (University of Minnesota) and Joong-Ho Ahn (Seoul National University) conducted “On the Explanation of Factors Affecting E-Commerce Adoption” article. They integrated the technology acceptance model with the theories of Perceived Risk to explain the e-Commerce Adoption Model (e-CAM). In details, they examined the influence of perceived ease of use, perceived usefulness, Perceived Risk with products/services, and Perceived Risk in the context of online transaction on the consumer’s purchasing behavior. Subjects for the study were the undergraduate and MBA students at two major universities in the United States. The survey lasted about a month and collected 183 responses, among which there were only 176 valid responses.

The results revealed that perceived usefulness, Perceived Risk with products/services and Perceived Risk in the context of online transaction have strong direct effect on the adoption of E-Commerce.

Figure 2.5. Research Model of Factors Affecting E-Commerce Adoption (Lee, Park and Ahn, 2001)

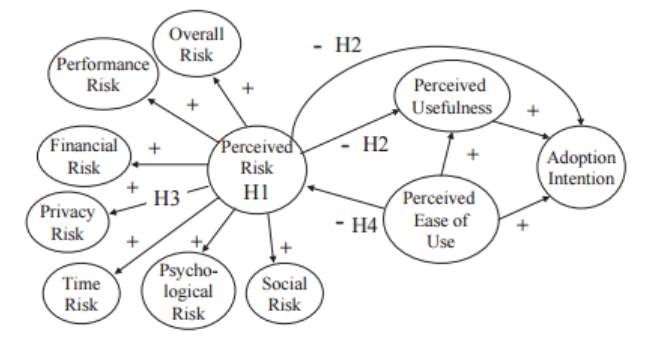

2.2.6. Predicting E-Services adoption: a Perceived Risk facets perspective (Featherman and Pavlou, 2003)

To understand the negative utility (potential losses) attribute to e-service adoption, Featherman and Pavlou did a research predicting E-Service adoption based on Perceived Risk Theory in 2003. The research gave out a proposed E-Services adoption model by operationalizing, integrating, and empirically testing specific risk facets within the Technology Acceptance Model. Also in the research, due to the low number of items when measuring the psychological and social risk facets, the authors combined these facets of Perceived Risk into one psychosocial facet as defined by Cunningham (1967).

Research findings indicated that performance-based risk facets (time risk, privacy risk, financial risk) adversely influenced e-services adoption, and perceived ease of use decreased these risk concerns. Performance-related risks proved to be the most salient concerns for the sample and context, with the fact that they appears to be the basis for all other risk facets. Meanwhile, the social risk concerns—the chance of losing status by using the e-service, were not noticeable.

Figure 2.6. Research model of Predicting e-services adoption: a Perceived Risk facets perspective (Featherman and Pavlou, 2003)

2.3. Proposed Research Model

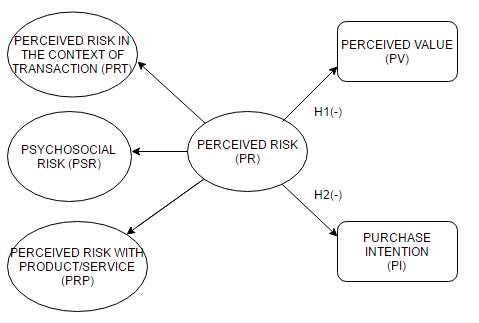

In regard of the relationship between Perceived Risk and Perceived Value, there are many researches (Sweeney et al., 1999; Teas and Agarwal, 2000; Korda and Mumel, 2004; Ashton, et al., 2008) that all reach the same conclusion of Perceived Risk has a negative impact on Perceived Value. Besides, there is an adverse relationship between Perceived Risk and Purchase Intention, which is proved and tested in the studies of Bauer (1960), Mitchell (1999), Kim, Ferrin and Rao (2008), and Chiu et al. (2012). Therefore, the researchers also hypothesize that Perceived Risk affects negatively on both Perceived Value and Purchase Intention of E-commerce Consumers in the context of this study.

Additionally, by applying the two theories of Lee, Park and Ahn (2001) and Featherman and Pavlou (2003), and conducting qualitative research, Perceived Risk in this study is made of three main components: Perceived Risks associated with Product/service, Perceived Risks happening during the process of online Transactions, and Psychosocial Risk.

In conclusion, from all related researches and qualitative research, the authors propose the model of Studying the Impact of Perceived Risk on Perceived Value and Purchase Intention as follows:

Figure 2.7. Proposed Research Model

2.4. Definitions and Hypotheses

2.4.1. Purchase Intention

The theory of reasoned action is considered as an influential explanation of the process that determines people’s intentional behavior (Boster et al., 2014). People generally consider the results that their actions will lead to before they decide to perform a certain action (Ajzen and Fishbein, 1980). The theory of reasoned action is used in order to predict a person’s intention to behave in a certain way; this is done by evaluating a person’s attitude towards a specific behavior as well as the subjective norms of influential people and groups that could affect the person’s attitude (Ajzen and Fishbein, 1980). Subjective norms are persuaded by one’s perception of the beliefs of the people around us, for example, parents, friends or colleagues (Ajzen and Fishbein, 1980). Subjective norms influence us since we have certain beliefs of how people will react to our behavior, and whether they will accept it or not (Ajzen and Fishbein, 1980). The subjective norms influence consumers’ online Purchase Intention through the attitude consumers have towards online shopping (Hansen et al., 2004).

Attitudes influence consumers’ online intention to purchase (Korzaan, 2003). Lim and Dubinsky (2005) stated that consumer attitudes towards online shopping affects if consumers have intentions to purchase online. Hansen et al. (2004) concluded that consumers attitude toward online shopping is a predictor of online shopping. Consumers’ attitude toward the behavior of shopping online is a determinant of behavioral intention (Hansen et al., 2004). In order for online Purchase Intention to exist, consumers must perceive the benefits of shopping online instead of in physical stores (So et al., 2005).

Purchase Intention is the plan to buy a specific product or service within a designated time (Hair, Wolfinbarger, and Money, 2011). Moreover, online Purchase Intention is affected by the consumers’ determination to purchase from an E-commerce business (Salisbury et al., 2001; Choon et al., 2010). When consumers are familiar with E-commerce businesses, they are more likely to visit an online site with the intention to purchase (Forsythe and Shi, 2003; Gefen and Straub, 2004; Yu-Hui and Barnes, 2007). The familiarity in E-commerce means that the consumers have an understanding for what is happening in that context, and what is going to happen next (Gefen, 2000; Gefen and Straub, 2004).

Companies need to meet the demands of consumers in terms of their needs and wants in order for Purchase Intention to increase (Fortsythe and Shi, 2003). Online Purchase Intention is a significant predictor to actual purchase (Pavlou, 2003; Kim et al., 2008). Online Purchase Intention is used to reach the goal of actual purchase (Lee and Lee, 2013). However, consumers’ actual buying behavior can be different from their buying intention (Lee and Lee, 2013).

2.4.2. Perceived Value

The general concept that can be understood is that Perceived Value involves the relationship between consumer and the product (Holbrook, 1996). Integrating various definitions of value into a single definition, Zeithaml (1988) proposed “Perceived Value is the consumer’s overall assessment of the utility of a product based on the perceptions of what is received and what is given”. The “received” components can be referred to the benefits get from using the product while the “given” components can be referred to the consumer sacrifice in acquiring the product including monetary and non-monetary aspect. In this regard, Zeithaml (1988) described value in four different ways: (1) value as low price, (2) value as whatever the consumer wants in a product, (3) value as the quality get from the price the consumer pay, and (4) value as what is get for what is given.

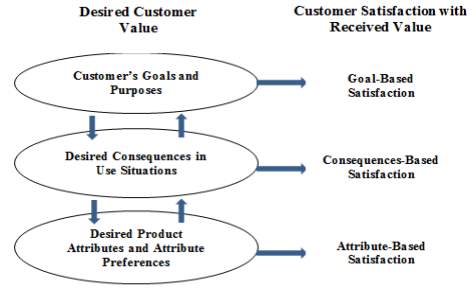

Woodruff (1997) defined Perceived Value as consumer’s perceived preference for an evaluation of those product attributes, attribute performances, and consequences arising from use that facilitate (or block) achieving the consumer’s goals and purpose in use situations. He suggested the value hierarchy model conceptualize into three hierarchy levels, which are desired attributes, desired consequences, and desired end-states or goal and purposes.

Figure 2.8. Value hierarchy model (Woodruff, 1997)

Woodruff (1997) suggests that consumers may either use their goal to attach and evaluate the attribute preferences and attribute performance, or think the product as a bundle of attributes then form the certain attributes based on their ability to facilitate the desired consequences, which eventually help them to achieve their goals and purposes. Woodruff (1997) argues that this hierarchy model helps manager to specify exactly what managers should learn about their consumers. He argues that this model looks beyond the attribute-based key buying criteria, in which it involves the consequences in use situation that the seller should learn and the goals to which those consequences lead. The dynamic concept of Perceived Value proposed by Woodruff (1997) is explaining the complexity of Perceived Value as well as has successfully helped to explain why consumer attach different weights to various benefits in evaluating alternative product/ service.

Zeithaml’s (1988) and Woodruff’s (1997) definitions and concept of consumer Perceived Value are the most used and implemented in the literature.

2.4.3. Perceived Risk

In 1996, Pallab said that consumers were worried about their credit cards and disclosing personal information when purchasing on the Internet. Meanwhile, Ko et al. (2004) assumed that consumers were also concerned about purchasing a product from the sellers without physically examining the products. Therefore, E-commerce consumers perceive the risk at high level when purchasing online compared with traditional one. Negative aspects belonging to this shopping mode are also becoming critical (Ko et al., 2004). On the other hand, Mitchell (1999) suggested that Perceived Risk is a powerful factor at explaining consumers’ purchase behavior since consumers are more often motivated to avoid the potential loss than to achieve purchasing success. Consequently, Perceived Risk has been a topic of study for many researchers and marketing managers (Kalakota and Whinston, 1996).

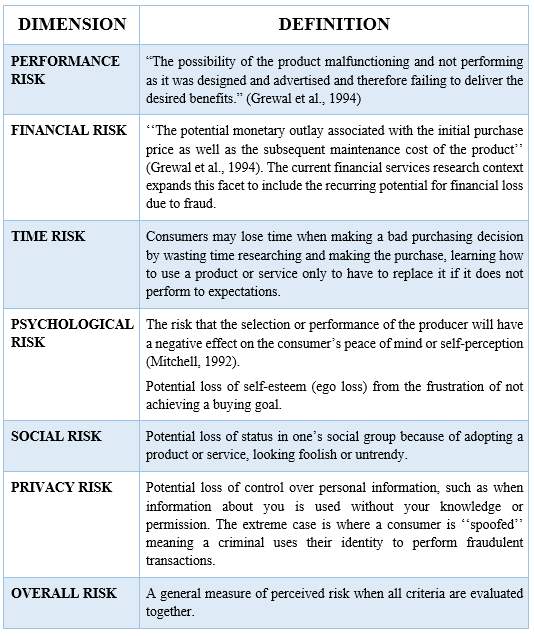

In 1960, Bauer pioneered the application of Perceived Risk theory to consumer behavior and indicated that Perceived Risk is developed on the basis that all consumer behavior involves risk and that, in uncertain circumstances, actions conducted by consumers may produce consequences that are beyond their expectations and unpleasant. Therefore, consumer behavior can be regarded as bearing a burden of risk. Cox (1967) further indicated that, when negative effects are produced because consumers are uncertain of how purchases should be executed to satisfy their target level the most or are worried that their purchases cannot achieve expected goals, Perceived Risk is produced. In addition, Cox (1967) indicated that Perceived Risk incorporated two concepts: the importance and degree of risk from the consequences of decision-making by consumers, and consumers’ subjective expectation that negative consequences may possibly occur. Moreover, if consumers perceived the probability of the mismatches between their expectations and incentives offered by the situation, after that, they perceived a risk of not fulfilling their motives at that time (Atkinson 1964). Cunningham (1967) proposed that consumer Perceived Risk is comprised of the severity of loss and unexpected results that may possibly occur. On the other hand, Freatherman and Pavlou (2003) defined Perceived Risk as consumers’ feeling unclearly about possible negative consequences when using product or service. They also identified seven dimensions of Perceived Risk: performance risk, financial risk, time risk, psychological risk, social risk, privacy risk, overall risk.

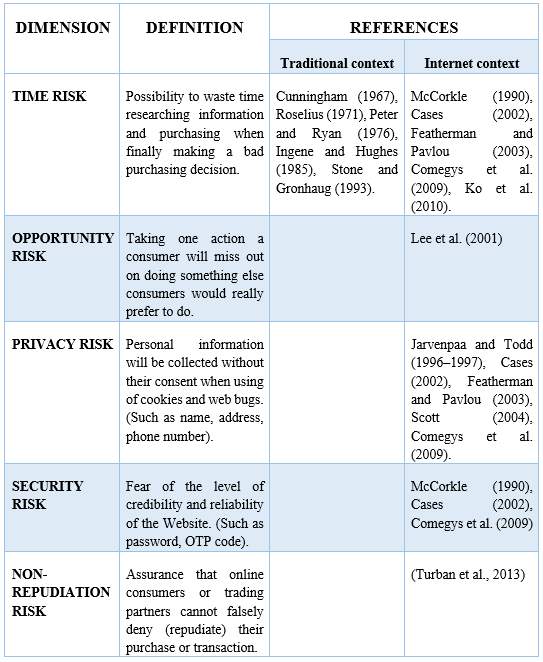

Table 2.1. Dimensions of Perceived Risk based on Featherman and Pavlou (2003)

In their research in predicting E-Service adoption based on Perceived Risk Theory (2003), Featherman and Pavlou combined the psychological and social risk facets of Perceived Risk into one Psychosocial facet as defined by Cunningham (1967).

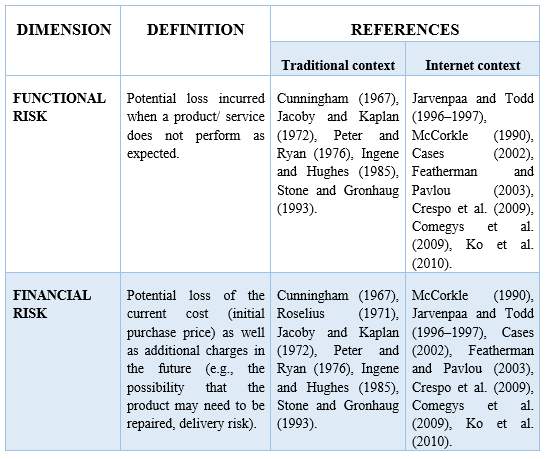

In addition, as mentioned by Lee and colleagues (2001), there are two main sections of Perceived Risk in the process of online shopping. The first one is the Perceived Risks associated with Product/service, which means that the risks when the consumers have to face to functional loss, financial loss, time loss and opportunity loss. The second is the Perceived Risks happening during the process of online transactions and including risk of privacy, security (authentication), and non-repudiation. Among them, the influence of financial risk, product risk, and concern for privacy and security is momentous (Senecal, 2000; Borchers, 2001; Bhatnagar et al., 2000). For more specific, Table 2.2 below shows the Perceived Risk dimensions which are cited from the previous researches.

Table 2.2. Perceived Risk Dimensions and Their Concepts Proposed in Marketing and Information System Literature

2.4.4. Hypotheses

The negative influence of Perceived Risk on the Perceived Value of different types of products (e.g. household appliances, calculators) has been found in researches of Sweeney et al. (1999), and Teas and Agarwal (2000). In addition, according to the study conducted by Snoj, Pisnik Korda and Mumel (2004), there is a significant relationship between Perceived Risk and Perceived Value. The research has found out that Perceived Risk has a negative influence on Perceived Value of mobile phones in Slovenia.

Furthermore, in a paper studying The impact of consumer evaluation on Perceived Risk, Perceived Value and intention to purchase in the field of Hotel restaurant co-branding, Ashton, et al. (2008) has led to the conclusion that low Perceived Value may be resulted from the high Perceived Risk and conversely, the low Perceived Risk may result in high Perceived Value. This also means that there is a negative relationship between these two mentioned factors.

Hence, the proposed first hypothesis is stated as follows:

Hypothesis 1. Perceived Risk has a negative effect on Perceived Value.

A consumer’s online decision has been found to be affected by Perceived Risk. It is common for a consumer who is about to make an online transaction to be unwilling to purchase online due to the overwhelming sense of risk when compared to the brick-and-mortal shopping (Bauer, 1960; Mitchell, 1999). Additionally, according to Kim, Ferrin and Rao (2008), a consumer’s Perceived Risk has a solid destructive impact on the Purchasing Intention, which has the meaning that the higher the level of Perceived Risk is, the less the intention to purchase of consumers is. Moreover, Chiu et al. (2012) provided confirmation that consumers’ Perceived Risk decreases Purchasing Intention in B2C E-commerce. In other words, Perceived Risk remains a negative factor of Purchase Intention.

Therefore, this research’s second hypothesis is formulated as follows:

Hypothesis 2. Perceived Risk has a negative effect on Purchase Intention.

Chapter 3: METHODOLOGY

Chapter 3 will discuss research process, research methods (qualitative and quantitative research), data collection methods, sampling design, questionnaire design, and data analysis methods. The details of qualitative research (in-depth interview and focus group) and quantitative research (survey) applied in this study are also described. Furthermore, the ethical aspect while conducting this paper is fully committed.

3.1. Research Process

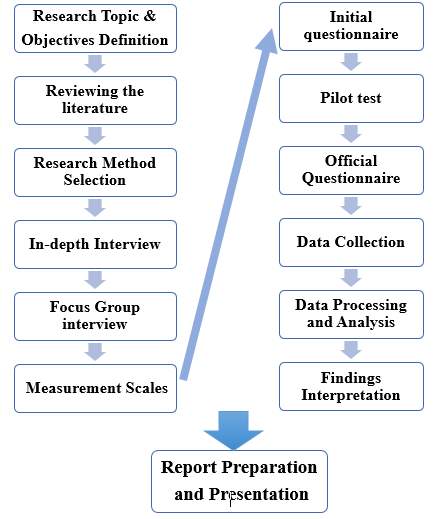

In this study, the research process is modified based on the business research process that is developed by William et al. (2012). The details of research stages are illustrated in the figure below, which was already adjusted to fit the research.

Figure 3.1. Research process (Adapted from William et al., 2012)

3.2. Research Methods

3.1.1. Qualitative Research

Hair, Wolfinbarger, and Money (2011) argued that qualitative research is a collection of data in the form of the text or image by using open-ended questions, observation and finding data. The researchers took data from respondents by using questions and observation of the behavior, gestures and their attitude. The aim is to find out deeply thoughts of the respondents. According to Bogdan and Biklen (1982), qualitative research has five features. The first is natural features. The researchers will directly interview respondents. In addition, they will use a number of tools such as paper, pens and recording equipment to support. It will help the researchers carefully observe behavior and attitudes of the respondents in the interview. The second feature is described data. This data is mainly in the form of words or images. It may be gestures, words, body language, the small details, which expressed through videos, recordings. Third, the researchers are interested in everything related to the process. In other words, they interested in how things happen. Fourth is data analysis by using inductive reasoning. Researchers will rely on open-ended questions to analyze the data. Final feature is meaningful features. The data collected will be displayed in the transcript and the material recorded. It will provide information for the report.

The advantage of qualitative approach is providing preliminary insight, which is useful in developing ideas about how variables are related. Normally, it can help to define constructs or variables, and even help to suggest items that can be used to measure those constructs (Hair, Wolfinbarger, and Money, 2011). Therefore, using this method, the research can successfully explore the impact of Perceived Risk on Perceived Value and Purchase Intention in E-Commerce. The main method for collecting qualitative data is in-depth interviews and focus group. In this research, researchers conducted both Focus Group and In-depth interviews with consumers who are using products and services in E-Commerce platform.

In-depth Interview

In-depth interview is method in which participant was asked by an interviewer face-to-face. The advantage of this method can provide good detail because researchers focus on individually at a time (Hair et al., 2012), which would be useful for this research to analyze as much factors as possible for the research. Furthermore, researchers can concentrate more about the insight of consumers’ decision, to clarify whether there is different view of factor on consumers’ perspective. The interviewers ask interviewees semi-structured or probing questions basing on prepared model and attributes (Hair et al., 2012). The authors decide to interview an expert who is working for Vat Gia Corporation.

In the interview, the expert introduced E-Commerce market in Vietnam was in the explosive period. She thanked to some reports, in which many evidences were showed to realize that this market was potential. However, she also mentioned that there were too many risk for consumers when they bought products or service via E-Commerce website. For more specifics, the consumers were facing various types of risk such as product risk, time risk, financial risk, security risk, privacy risk, and non-repudiation risk. Moreover, she emphasized that especially in Vietnam market, there were the appearance of opportunity risk, relationship risk and social risk, since buying via E-Commerce website was not popular, while the traditional trade played an important role in the everyday trading. When asked, the expert stated that these risks had the negative impact on the perception of consumers about not only what additional values consumers could gain from E-commerce compared to that from traditional trading, but also whether buying products or services via E-Commerce websites or not.

Focus Group Interview

Focus Group interview is one where the interviewer exercises greater control over the interview while permitting the interviewee’s opinions to come out as he or she answers to the questions of the researcher (Easterby-Smith et al., 2008; Ghauri and Gronhaug, 2010; Robson, 2011). A focus group is a group interview that focuses on a particular issue, product, service or topic by encouraging discussion amongst participants and the sharing of perceptions in an open and tolerant environment (Krueger and Casey, 2009). This means that, in comparison with other forms of group interview, individual group members’ interactions and responses are both encouraged and more closely controlled to maintain the focus. Participants are selected because they have certain characteristics in common that relate to the topic being discussed and they are encouraged to discuss and share their points of view without any pressure to reach a consensus (Krueger and Casey, 2009).

In this research, there are eight participants who had purchased through E-Commerce website. They include four students, two professors and two employees in FPT University Campus Ho Chi Minh City. Questionnaire content for qualitative research methods at Appendix 2: Questions for focus group interview.

In the interview, the participants said that they bought many kinds of products via E-Commerce websites, such as cosmetics, fashion items, household devices and electronic devices. Moreover, Tiki.vn, Lazada.vn, Amazon.com, Taobao.com were the popular websites that they often visited to look for the information of electronic devices and make orders. Most of them knew these websites by their friends and the advertisement banners in other websites. When asked about their Perceived Risk when buy electronic devices in E-Commerce websites, they realized that there were many types of risk including time risk, financial risk, performance risk, privacy risk, security risk, non-repudiation risk, social risk and psychological risk. The interviewees also mentioned that if they felt the risk in some E-Commerce websites, they would not buy products or service via these websites, never introduced these websites for their friends.

On the other hands, six over eight participants agree with the interviewer about the opportunity risk when make the electronic devices in E-Commerce websites. Most of the reasons why they perceived the opportunity risk were that they found other websites sell the same products with low prices, that buying this products means they waived buying other products.

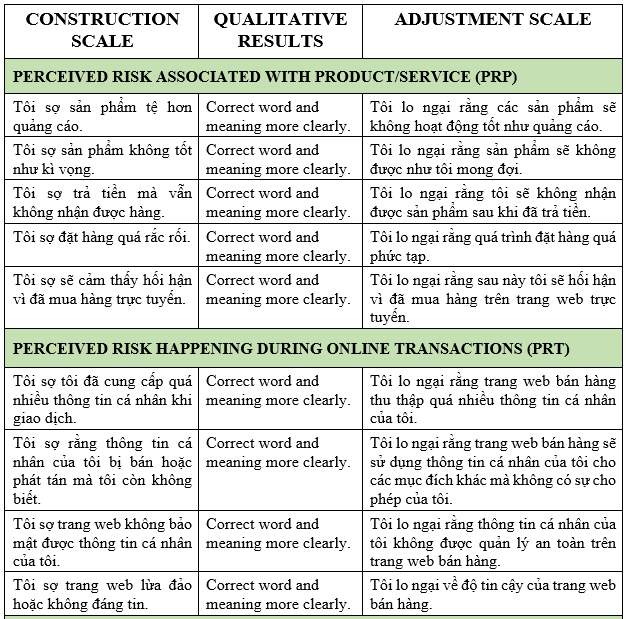

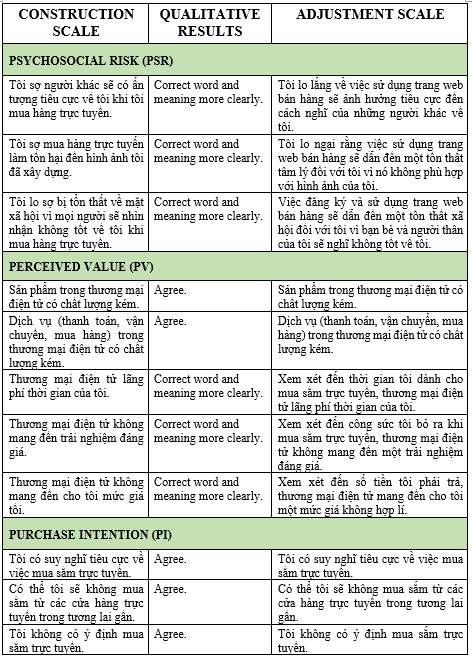

Participants in the interview also assisted the author in developing and adjusting variables that fit the scale, adding, subtracting or changing the wording for comprehension and relevance to all participants who attempt the official survey. Qualitative research results help the authors get the corrected scale as the following:

Table 3.1. Adjusted Measurement Scale

3.1.2. Quantitative Research

Quantitative research methods is common methods and mainly that the researchers used (Goulding, 2002; Singh, 2007). According to Creswell (2009), data were collected by using quantitative methods are more valuable and more reliable than qualitative research method. Besides, quantitative research method uses predetermined response options and questions in form of questionnaire to reach a huge number of respondents (Hair et al., 2012). In addition, Woodside and Wilson (2003) suggested quantitative research method help researchers understand the problem better. It will help identify relationships between data sets. Moreover, the researchers can have conclusion based on the analysis of statistical data.

As mentioned above, qualitative method is useful in explore the factors of service quality and combine with secondary data, it can create the literature framework, which have both factors and relationships of these factors. On the other hand, quantitative method is better use for in obtaining information to predict relationship between factors, get meaningful insight of the relationship, validate relationship and test hypotheses (Hair et al. 2012). Therefore, in this research, quantitative research method is conducted after qualitative research to analyze the relationship of factors achieved from qualitative research. In particularly, survey was used.

Survey method

Survey research method is usually used to collect quantitative data for descriptive research design from large group by using question/ answer process. There are three major type of Survey research methods: Person-Administered, Telephone-Administered and Self-Administered (Hair et al., 2012). Self-Administered survey, which completed by the survey subject, comprise Mail survey; online survey; Mail panel survey; Drop-off survey; Paper and pencil survey (Hair et al., 2012).

Paper and pencil survey method in Self-Administered are used in this research.

3.3. Data Collection Methods

Data collection methods play an important role in impact evaluation by providing information useful to understand the processes behind observed results and assess in people’s perceptions (Fhssrsc.byu.edu, 2017). Researchers need to deepen the understanding of data collection methods as well as develop a data plan in a scientific manner. This helps not only achieve the highest efficiency but also avoid wasting money and time-consuming. The researcher should use as many data sources as possible (e.g. using primary and secondary data) as this will make a research more powerful (Myers, 2008). Secondary data refers to information that previously collected for some other problem or issue, and it includes data from reliable sources such as journal or newspaper articles or published books (Myers, 2008). In other way, primary data is the data collected by the researchers for a current research problem or opportunity (Hair et al., 2010). Therefore, the data can be collected through primary or secondary sources.

3.3.1. Primary Data

The primary data is collected from both qualitative research (in-depth interview and focus group) and quantitative research (survey). The in-depth interview was conducted on January 25, 2017 with an expert from Vat Gia Corporation, with the total time of interview approximately 20 minutes. The focus group interview was conducted on January 30, 2017 with eight participants from FPT University Campus Ho Chi Minh City (four students, two professors and two employees) at the self-study corner on second floor. After that, the pilot study with 60 respondents was carried out online in there days time starting from February 15, 2017. The link of the online survey was delivered through social network’s accounts of the researchers.

Finally, the official survey was conducted in two weeks time, from March 01 to March 14, 2017, in four districts (District 1, 3, 12, and Tan Binh) of Ho Chi Minh City. The official questionnaire has four pages, including three sections with 28 questions. The researchers collected 400 valid samples at the end of the survey.

3.3.2. Secondary Data

Secondary data is not directly collected by researchers but it is collected from available sources. Many different sources, such as reports of government, ministries, agencies, newspapers, specialized scientific and academic journals, and books, help researchers explore research problem and use related information effectively. There are three kinds of secondary data: Multiple Sources, Survey and Documentary (Mark Saunders, Philip Lewis and Adrian Thornhill, 1997). In this study, secondary data are used to support clarifying the impact of Perceived Risk on Perceived Value and Purchase Intention in E-Commerce.

3.4. Sampling Design

3.5.1. Sampling Techniques

Sampling techniques consist of a list of methods that minimize the overload-collected information by gathering data from a sub-group instead of all possible cases (Saunders et al., 2003).

Hair (2011) separated sampling methods into two categories, including Non-probability and Probability. According to Dissertation.laerd.com (2017), Non-probability Sampling is the technique that the subjective judgement of the researcher is the basis for samples to be collected, while Probability Sampling Technique has random selection as its cornerstone. Within the scope of this research, there is not a comprehensive population list available or online shopper database. Therefore, non-probability sampling method is chosen and applied in this paper.

There are many types of Non-probability sampling technique, but Judgmental Sampling Technique is selected to be used in this research. Judgmental Sampling is a technique in which the researchers choose a sample from a population based on their own experience and assessment of the condition, rather than using statistical sampling techniques (Neuman, 2005; Oxfordreference.com, 2017). In addition, Judgmental Sampling has the advantage of making generalizations easier because all participants have characteristics the paper focus on, compared to a random sample (Statistics How To, 2017).

3.5.2. Sample Size

According to Hair, Black and Babin (1998), to ensure the accuracy of the research, the sample size (n) is defined on the ratio of 5:1, which means the minimum number of samples should be at least 5 times the total number of variables in Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA), and the amount of samples should not be less than 100.

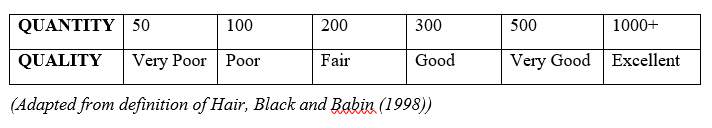

In this study, with 20 items, the minimum sample size to be ensured should be n= 5*20 =100. In addition, Comrey and Lee (1992), Tabacknick and Fidell (1996) stated that the number of respondents would reflect the reliability of the corresponding results as shown in Table 3.

Table 3.2. The relationship between Quantity and Quality of Sample Sizes

Consequently, the authors decided the sample size in this paper would be 400.

Consequently, the authors decided the sample size in this paper would be 400.

3.5. Questionnaire Design

Questionnaire is a tool including many associated questions to reach the final goal of collecting data from respondents (Malholtra and Briks, 1999). The questionnaire structure consists of three parts: screening questions, survey questions, and personal information. Part 1 employs Nominal Scale to develop Screening Questions, whereas Part 2 applies the 5-point Likert Scale to determine consumers’ Agreement level in 3 factors.

Nominal Scale requires respondents answer to gather raw responses (Hair, Wolfinbarger, and Money, 2011).

Likert Scale asks respondents the agreement level with statements based on their behaviors (Likert, 1931). According to Likert (1931), the Likert Scale had five scale descriptors, which include ‘Strongly Disagree’, ‘Disagree’, ‘Neither Agree or Disagree/ Neutral’, ‘Agree’, and ‘Strongly Agree’.

3.4.1. Measurement Scale

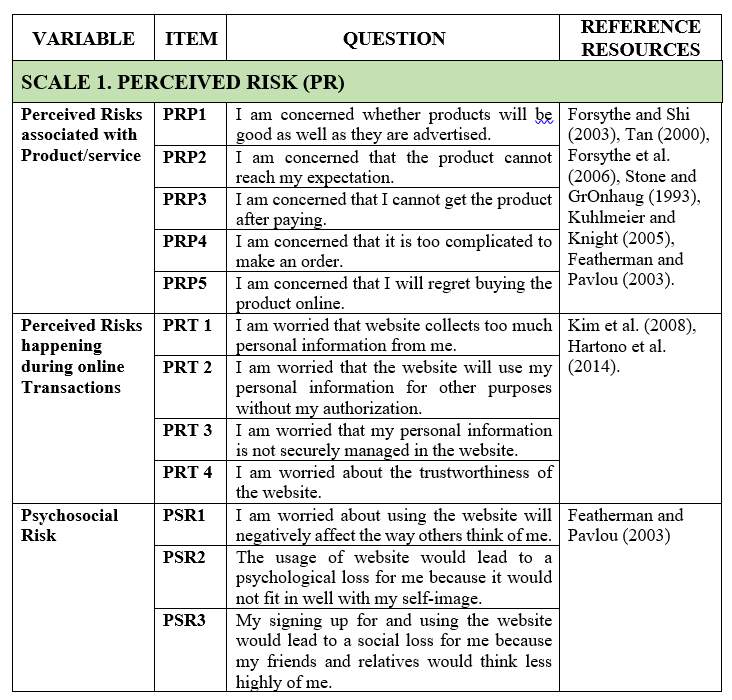

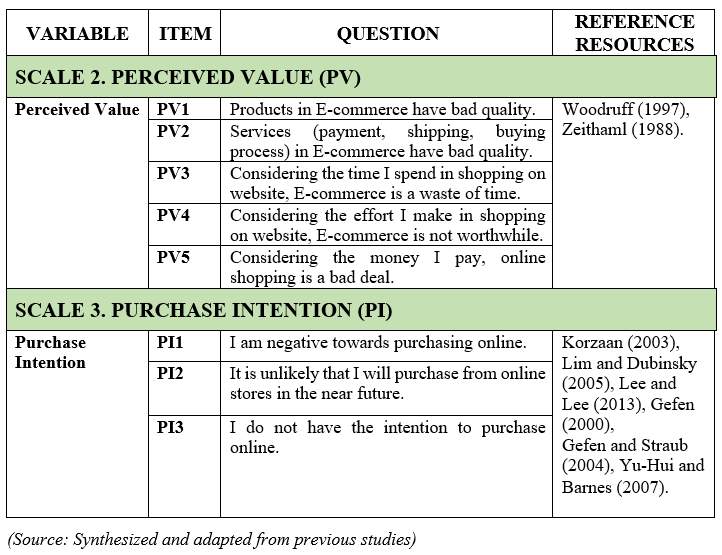

Measurement scale is the combination of selectively earlier studies in the field such as the research of Forsythe et al. (2006). Stone and GrOnhaug (1993), Kim et al. (2008), Hartono et al. (2014), Woodruff (1997).

In details, the measurement scales of Perceived Risk, Perceived Value, and Purchase Intention are demonstrated as follows.

Table 3.3. Measurement Scale

3.4.2. Pilot Test

A pilot test is carried out on a small scale of 60 respondents, who are guided by researchers and worked independently. The objective of this pilot test is to test the logic of the questions, grammatical and spelling errors before the official survey.

Scale verification and preliminary analysis

Cronbach’s Alpha analysis

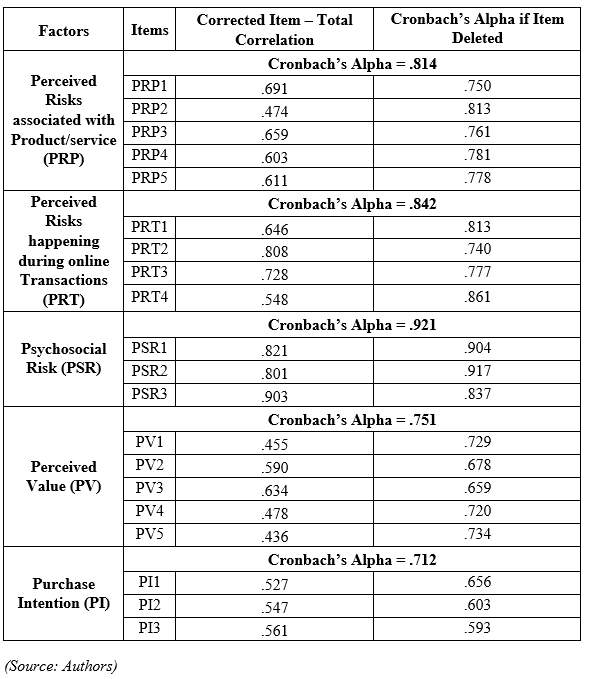

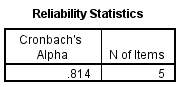

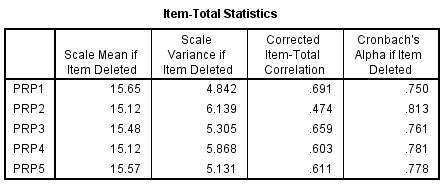

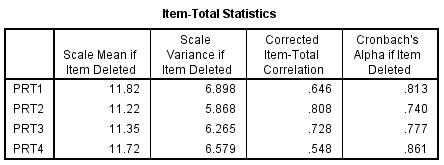

For the Perceived Risk associated with product and service scale, both the Corrected Item – Total Correction coefficient of all items are greater than 0.3. The Cronbach’s Alpha coefficient of the group is 0.814 and greater than 0.6 while the Cronbach’s Alpha coefficient of each variable when eliminating itself is smaller than Cronbach’s Alpha coefficient of the group. Therefore, scale met the standard for conducting official survey.

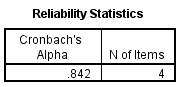

For the Perceived Risk happening while the process of online transaction scale, both the Corrected Item – Total Correction coefficient of all items are greater than 0.3. The Cronbach’s Alpha coefficient of the group is 0.842 and greater than 0.6 while the Cronbach’s Alpha coefficient of each variable when eliminating itself is smaller than Cronbach’s Alpha coefficient of the group. Therefore, scale met the standard for conducting official survey.

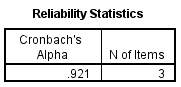

For the Psychosocial Risk scale, both the Corrected Item – Total Correction coefficient of all items are greater than 0.3. The Cronbach’s Alpha coefficient of the group is 0.921 and greater than 0.6 while the Cronbach’s Alpha coefficient of each variable when eliminating itself is smaller than Cronbach’s Alpha coefficient of the group. Therefore, scale met the standard for conducting official survey.

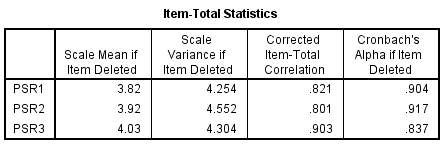

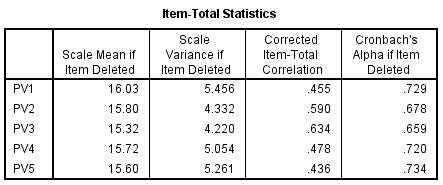

For the Perceived Value scale, both the Corrected Item – Total Correction coefficient of all items are greater than 0.3. The Cronbach’s Alpha coefficient of the group is 0.751 and greater than 0.6 while the Cronbach’s Alpha coefficient of each variable when eliminating itself is smaller than Cronbach’s Alpha coefficient of the group. Therefore, scale met the standard for conducting official survey.

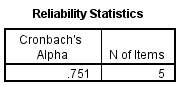

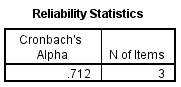

For the Purchase Intention scale, both the Corrected Item – Total Correction coefficient of all items are greater than 0.3. The Cronbach’s Alpha coefficient of the group is 0.712 and greater than 0.6 while the Cronbach’s Alpha coefficient of each variable when eliminating itself is smaller than Cronbach’s Alpha coefficient of the group. Therefore, scale met the standard for conducting official survey.

Table 3.4. Cronbach’s Alpha pilot test

Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA)

Perceived Risk

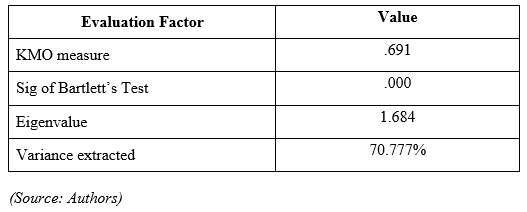

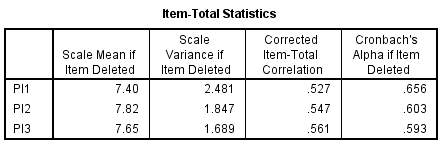

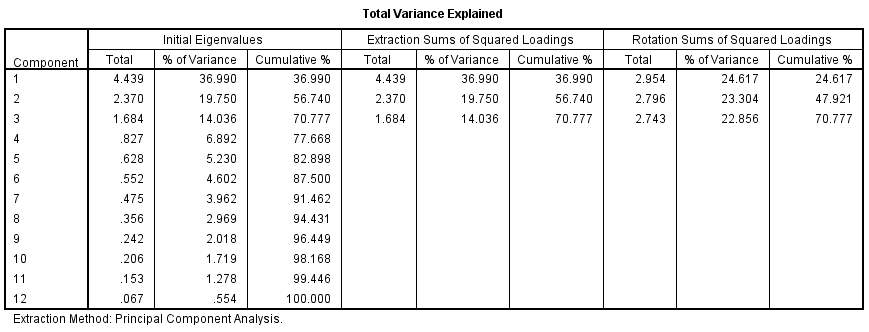

Based on the test results, the KMO of the three Perceived Risk scales is 0.691 and greater than 0.6. Sig value (Bartlett’s test) is 0.000 and is less than 0.05 so the Exploratory Factor Analysis is reasonable and analytical coefficients meet the requirement to conduct the official survey.

Eigenvalue equals to 1.684 and greater than 1, which represents that the variance is explained by each factor, and the derived factors have the best summary information.

The variance extracted is 70.777% and greater than 50% so the scale has the statistical significance.

Table 3.5. The table summarizes EFA results of Perceived Risk

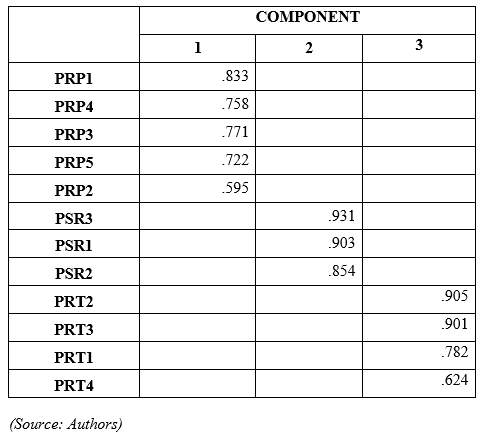

Table 3.6 shows that 12 observation variables are grouped into 3 groups, all variables have the Factor Loading coefficient about 0.5. Therefore, conditions are met to conduct the formal survey.

Table 3.6. Rotated Component Matrix of Perceived Risk

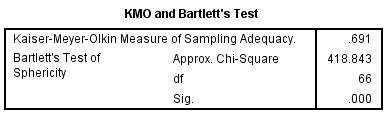

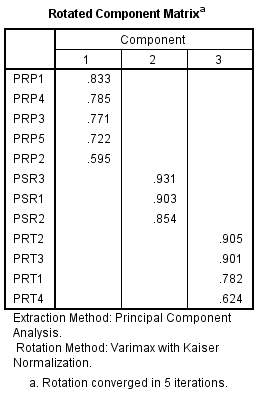

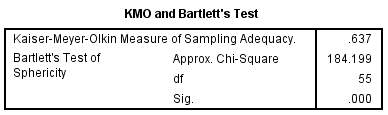

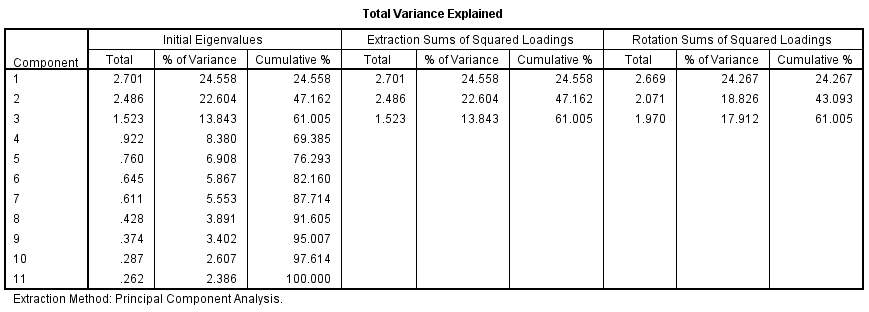

Perceived Value and Purchase Intention

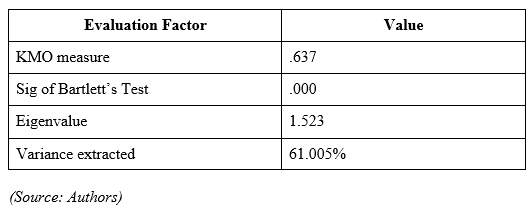

Based on the test results, the KMO of the three Perceived Risk scales is 0.637 and greater than 0.6. Sig value (Bartlett’s test) is 0.000 and is less than 0.05 so the Exploratory Factor Analysis is reasonable and analytical coefficients meet the requirement to conduct the official survey.

Eigen value equals to 1.523 and greater than 1, which represents that the variance is explained by each factor, and the derived factors have the best summary information.

The variance extracted is 61.005% and greater than 50% so the scale has the statistical significance.

Table 3.7. The table summarizes EFA results of Perceived Value and Purchase Intention

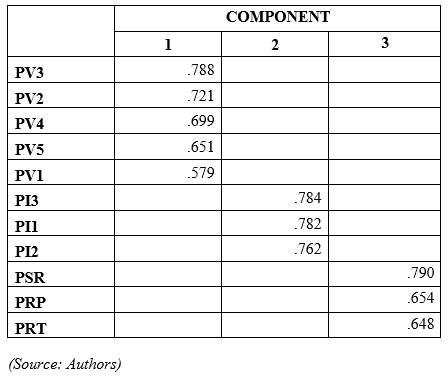

Table 3.8 shows that eight observation variables are divided into two groups; all variables have the Factor Loading coefficient about 0.5. Therefore, conditions are met to conduct the formal survey.

Table 3.8. Rotated Component Matrix of Perceived Value and Purchase Intention

3.6. Data Analysis Methods

In this report, the authors used IBM SPSS 20 and IBM AMOS 22 as the tools to analyze and process the data.

3.6.1. Descriptive Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics is applied to not only describe the basic characteristics of the data but also provide an elementary summary of sample and measures. This provides the basis for all quantitative data analysis.

When summarizing a quantity of consumer characteristics such as gender, age, income, the statistical parameters usually mentioned are frequency, percentage, variance, standard deviation. These data are represented by diagrams or descriptive tables that make it easy to analyze and compare information together. To approximate the relevance of descriptive statistics, consider whether there is a relationship between pairs of related variables, the Independent-Sample, T-Test, One-Way ANOVA test are generally considered to use.

3.6.2. Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA)

Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) is a technique to reduce a set of observational variables to a smaller number of factors but these still demonstrate most of the information content and statistical significance of the initial set of variables (Hair, Black and Babin, 1998). Each observation variable will be weighted as a factor called Factor Loading, which tells the researchers which factor that each variable will belong to.

The EFA model is considered appropriate when the following criteria are met:

Factor Loadings are the single correlation coefficients between variables and factor systems. The selected observational variable is the factor whose Factor Loading is greater than or equal to 0.5 (Hair, Rolph and Tatham, 1987) and KMO coefficient (Kaiser Meyer Oklin) is from 0.6 to 1 (Kaiser, 1974).

Cumulative of variance is the percentage of total variance cited by the factors. Total variance accounted for with the addition of each successive factor. According to Kaiser (1974), the criterion for accepting factorial analysis is cumulative of variance greater than 50%.

After the new factorial variables from a set of observations are reduced, these variables are included in further analyses such as Independent-Sample T-Test, One-Way ANOVA Test.

3.6.3. The Reliability of Scale

The reliability of scale is evaluated by using the Cronbach’s Alpha coefficient. This is the reliability confidence used to measure the correlation between observed pair variable.