Analysis of the Responsible Leadership Model

Info: 11403 words (46 pages) Dissertation

Published: 8th Jul 2021

Tagged: Management

Lessons from History: How Embracing Adaptive Change Could Have Saved Scott in the Race for the South Pole

Introduction

There are number of initiatives that can propel change to the forefront of the modern organization. Research has suggested (O’Brien, 2017, 2016, 2015a, 2015b, 2014, 2013a, 2013b, 2013c; Purcell and O’Brien, 2015; Walsh and O’Brien, 2017) that there are a number of factors to consider: the culture of the organization needs to change or needs to be explored, the cross-functional benefits have not been realized and need better integrating, the actual functional issues at the front-lines have not been understood and need to be better incorporated, the effects of information-system use on group cohesion has not been examined, employee knowledge needs have not been met, managers do not understand the interplay between the services the organization is providing versus the knowledge needed to provide that service, or even the strategic interplay between where an organization is exploiting its knowledge versus searching for new knowledge. These situations could all produce change. That said, in a nutshell, organizations today are faced with two types of overarching change: technical and adaptive, (Caporarello and Magni, 2016; Acona et al., 2007; Acona, 1990). The first type of change calls for diagnosis and resolution based on well-known methodologies and procedures. Changes grounded in technical challenges are usually resolved through the involvement of authority figures that have the skills and knowledge to deal with the issue at hand. Change rooted in adaptive challenges, however, represent issues that do not have a technical solution or expertise, and, importantly, that require facing a dilemma or gap between the reality and the expectations or values that are held dearly by the people affected by the challenge. Adaptive challenges require involvement of people in the organization in the process of problem-definition and search for solutions through experimentation.

With different types of change, the role of people in managerial positions alters. According to Heifetz and Linsky (2002), and Heifetz, Grashow, and Linsky (2009a, 2009b), under the conditions of technical change, management acts in the role of authority figures. In that role, they get authorized by organizational members to play that role in exchange for services. There are three types of those services: direction, protection, and order. Managers are expected to define the problem and bring in a solution. They are also expected to protect the organization and its members from external threats. Finally, they are expected to orient people to their tasks and roles, minimize conflict, and maintain organizational norms.

The requirements of being in an adaptive leadership role, however, are different. Managers in that role identify the adaptive challenge and frame issues and questions that are related to it. Rather than blindly protecting the organization and its incumbents, they make organizational members aware of the external threats and challenges. Instead of orienting people to roles, they question the roles and encourage experimentation. Conflict is not minimized, but rather exposed. Last but not least, in an adaptive leadership role managers challenge existing norms and experiment with created conditions where these norms can be challenged by others. Heifetz, Grashow, and Linsky (2009a, 2009b) argue that most of the change in the future is going to be adaptive in nature, with the expertise and skills for solving organizational challenges not readily available.

[A]daptive change stimulates resistance because it challenges people’s habits, beliefs, and values. It asks them to take a loss, experience uncertainty, and even express disloyalty to people and cultures. Because adaptive change forces people to question and perhaps redefine aspects of their identity, it also challenges their sense of competence. Loss, disloyalty, and feeling incompetent: That’s a lot to ask. No wonder people resist. (Heifetz and Linsky 2002, 30).

At this juncture, the author poses the question: What is good leadership? What is expected of a person in a leadership role? We may all refer to our own experience of being led in organizations. Usually responses to this question refer to a leader’s knowledge and expertise, personal qualities, engagement and motivation of others, challenging the organizational views on the issues at hand, foreseeing need for change, managing the process of change, overcoming resistance to change, conducting necessary evils, management of relationships in the organization, etc. (Hackman, 2002; Locke and Latham, 2002; Magni and Pennarola, 2015).

We may also think about examples of leaders who have managed considerable and painful change efforts in organizations or societies and think about the necessity of some of the harsher actions that are not necessarily liked by people.

In the United States, for example, Abraham Lincoln’s emancipation proclamation was not met with universal applause, or in Ireland, Michael Collins’ signing of the peace treaty with the United Kingdom in the 1920s was met with division and skepticism, yet one could argue the long-term benefits of these leadership choices.

Is the responsibility of the leader to keep people happy or to push them in the direction that is necessary for survival or prosperity?

There are several leadership models to draw upon (e.g., Goffee and Jones, 2000; Kouzes and Posner, 1995; Kets de Vries, 2009) that stipulate that often leadership is about getting people to do what they need rather than what they would like to do. In many cases doing so involves dealing with resistance (De Dreu and West, 2001).

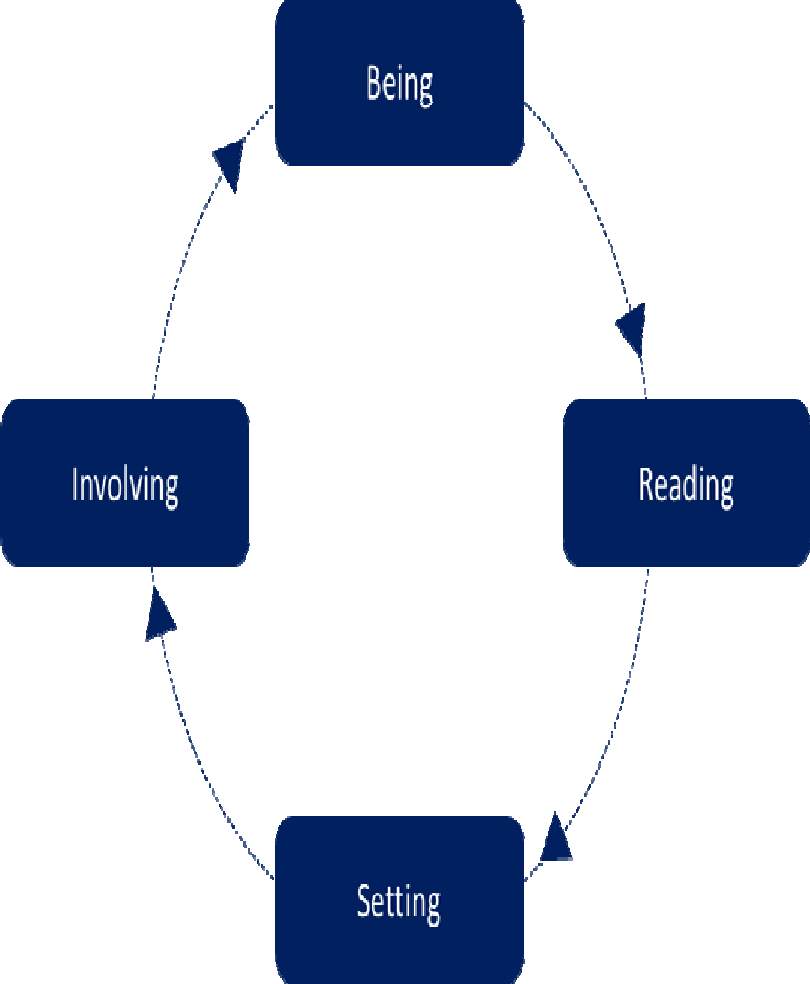

In order to set up the analysis for the case presented, the discussion will utilize the Responsible Leadership model developed by Magni and Pennarola (2015). The Responsible Leadership model is built on the assumption that being a responsible leader is the outcome of systematically questioning and improving leading behaviors through ongoing experiences, in a long-term sustainability perspective.

Figure4: Responsible Leadership Model

A leader’s decisions and actions can be interpreted in the light of the four pillars of the model:

Being: the first step toward Responsible Leadership is the awareness of the self as a key organizational actor (Cannon-Bowers et al., 2001; Carson, et al., 2007; Cullen, et al., 2015).

The leader must own her/his role and bear the responsibilities associated with it. The leader’s drive must be excellence, developed through constant challenging of the comfort zone and continuous improvement of own competencies and skills. Yet, seeking excellence requires great awareness of both strengths and limits, to find the right way to overcome them (Cannon-Bowers et al., 2001; Carson, et al., 2007; Cullen, et al., 2015). Finally, the leader must be able to manage the pressures associated with being responsible for contributors and organizational results through the acting of proper stress-management techniques.

Reading: The challenges of leadership extend beyond the individual, which has to actively screen the context and interact with it to gather useful information and insights. The leader must drive the exploration of what is outside the organization by activating her/his networks to gather new insights and ideas. Such exploration must be grounded in focused attention to screen and capture what is relevant and critical to avoid dispersive overload. The leader must then assimilate the gathered information to shape a vision on future scenarios that is also clear to communicate and understand for contributors.

Setting: Given the context framework, the leader is responsible for orientating the actions of those who surround him toward the implementation of the vision and the meeting of organizational needs (Magni, et al., 2009; Van Knippenberg, et al., 2004). The leader must then set clear and challenging, yet achievable goals, to push contributors toward the target. In doing so, the leader must own a principle of accountability to be transferred to contributors, leading by example in taking full responsibility of decisions and their consequences. The leader thus has to define norms that create a cohesive and determined team unit, aligning opinions and behaviors toward the target goals.

Involving: The leader is responsible for managing others (Wageman, 1995). As such, an effective leader cannot overlook those behaviors that ensure the proper involvement and engagement of contributors, as they are key drivers of the team’s excellent performances. The leader must take into consideration the individualities of contributors, since each one of them may best contribute to team success through specific talents and assets. An effective management of delegation is essential to ensure the right empowerment of contributors, which must share the ownership of team’s actions and results. The leader must finally make sure that contributors are emotionally engaged in putting in their best efforts to reach the goal, also by proposing innovative solutions that go beyond consolidated competencies.

This model will be used later as a basis for the analysis of the leaders outlined in the case below.

Case Study: The Race to the South Pole

The beginning of the 20th century was the golden age of Antarctic exploration. The race to the South Pole, after the North Pole had been reached, came down to two major contenders — Robert Falcon Scott from England, and Roald Amundsen from Norway (Figure 1).

Figure 1: The Contenders

Source: adapted from Bown (2012), Huntford, (2000) – from left to right: Roald Amundsen and Robert Falcon Scott

Scott

Robert Scott served as a naval officer in peacetime Victorian England, when limited opportunities existed for career advancement. Despite having no real interest in Antarctica, at the age of 32 Scott applied to lead the Discovery expedition to the South Pole (Huntford, 2000). Historically, the expedition is generally considered somewhat of a failure and suffered greatly from two key issues – Scott and his crew failed to master dog sledging and skiing. The crew also suffered greatly from scurvy, a condition caused by vitamin C deficiency, and diary entries of those who took part in the Discovery expedition indicate that Scott failed to motivate his subordinates.

“Fancy all hands being drove on deck on a day like this just because the skipper wants to inspect the mess deck, it’s a bit thick you know. Why, one of our men had most of his toes frostbitten whilst waiting for the above mentioned individual [Scott] to go his cursed rounds as they call it. This and a few more petty items [Navy routine] is causing a lot of the discontent on the mess deck.” – Williamson, Discovery expedition (Huntford, 2000, 151).

“Life on board was very monotonous…many are short tempered and low spirited” – Ship steward, Discovery expedition,(Huntford 2000, 151).

Scott relied mostly on the experience of prior British expeditions. He was not open to learning from the Norwegians (the other exemplar polar-explorer nation of the time) about the use of dogs to pull supply sledges (Huntford, 2000). He preferred man-hauling, an arduous physical process to transport supplies. Many of the merchant marines left the expedition on a supply ship. They found Scott’s strict militaristic leadership style unacceptable. During the Discovery expedition, Scott reached the farthest point south, 82 degrees, in a man-hauling trek with two other men. They nearly starved from lack of rations and nearly froze from inadequate clothing, but they made it back to the ship and then back to England (Huntford, 2000). Scott’s leadership style could be criticized, but is hardly surprising given his training. Vice Admiral Dewar’s comments on the training that Scott would have received shed some light:

“The repressive atmosphere…checked initiative and self-confidence…the greater part of the syllabus was allotted to navigation, mathematics and seamanship. Navigation was taught by Naval instructors who had no practical experience of navigating a ship…The syllabus omitted the study and use of the English language. This was particularly unfortunate, for the efficiency of Naval administration often depends on the powers of clear expression.” – Vice Admiral K.G.B. Dewar, (Huntford 2000, 112).

Dewar also comments:

“… the majority worked hard because their future seniority depended on the result of the passing-out examination. Thus it was not intelligence, character, aptitude for command nor professional zeal that started a young officer on his upward career, but mastery of such subjects as algebra, the binomial theorem or trigonometrical questions.” – Vice Admiral K.G.B. Dewar, (Huntford 2000, 112).

The second and most infamous Scott expedition, aboard the Terra Nova, sailed from Cardiff, Wales, on June 15, 1910, with a 65-man party. The Terra Nova stopped in South Africa, Australia and New Zealand for fundraising efforts. In Melbourne, Scott received the cablegram from his rival, Amundsen, informing him of his own expedition. Astounded by the news, Scott was very secretive about it, even with his officers. The crew would know about what had now turned into a race to the Pole through the press, but their captain kept refusing to discuss the subject. Crewmember Lawrence Oates reported:

“If [Amundsen] gets to the Pole first we shall come home with our tails between our legs […]. I must say we have made far too much noise […]. They say Amundsen has been under hand in the way he has gone about it but I personally don’t see it is under hand to keep your mouth shut […] if Scott does anything silly such as under feeding his ponies he will be beaten as sure as death” (Huxley 1990, 202).

The party set its basecamp at Cape Evans, 12½ miles north from Hut Point, the former shelter of the Discoveryexpedition. Scott was eager to start the lay-down of the supply depots that would support his march to the Pole in the coming spring. The ongoing hot season involved the risk of ice cracking, which could impede reaching Hut Point. He then hurried the departure, leaving behind special footwear for the ponies, designed to protect them from the frozen ground. Oates, in charge of the ponies, reported:

“We shall I am sure be handicapped by the lack of experience which the party possesses. Scott having spent too much of his life in an office, he would fifty times sooner stay in the hut seeing a pair of … putties suited him than come out and look at a ponies legs or a dogs feet.” (Limb and Cordingley 1995, 107).

About 37 miles after Hut Point, the party was hit by a severe snowstorm, which mostly weakened the ponies. Selected by Mr. Meares, who had no experience with horses, they were of poor quality and would prove ill-suited to prolonged Antarctic work. Afraid of losing them, Scott ordered to send back the three weakest ponies. However, the load for the remaining ones proved too great to bear (almost 2,000 lbs. each) and some started to suffer from frostbitten feet. Limited by the adverse weather, Scott set to lay-down the One Tone Depot at 79° 29’ S, more than 30 miles north (or short) of the planned position at 80° S. He then hurried back with the dog teams to Safety Camp, the first depot, and waited for the slower ponies. At their arrival, the weakest died. Oates would not forgive the captain for his lack of sensitivity in leaving behind the horse team:

“I dislike Scott intensely and would chuck the thing if it was not that we are the British expedition and must beat the Norwegians […] the fact of the matter is that he is not straight, it is himself first, the rest nowhere, and when he has got what can out of you, it is shift for yourself” (Preston 1999, 161)

While marching back, near Hut Point, the ice cracked and, in spite of the crewmembers efforts, three more ponies died. When the party reached Camp Evans in mid-April, only two ponies remained of the eight. After the leave of other scientific and exploration teams, 27 men spent the winter at Cape Evans. Clothing proved manifestly defective, yet Scott reported in his diary:

“One continues to wonder as to the possibilities of fur clothing as made by Esquimaux, with a sneaking feeling that it may outclass our more civilized garb. For us this can be only a matter of speculation, as it would have been quite impossible to have obtained such articles. With the exception of this radically different alternative, I feel sure we are as near perfection as experience can direct” (Scott, 2006, 260).

As a result, neither clothing nor any other equipment was altered. Preparations for the Polar journey did not start until after mid-June. Meanwhile, Scott worked alone on the plan to reach the Pole, which he shared only on September 10. He wanted to divide the party into four teams: Three support teams would provide supply transportation and manpower support for the fourth team, the only one to eventually reach the South Pole. The teams would start at different rates and the party would reduce in size, leaving a final team of four individuals for the run to the Pole. He set the start from Hut Point, and planned to travel 1,766 miles in 144 days. Scott’s peers silently accepted such plan, yet not so enthusiastically. In his diary, one of the explorers defined Scott’s plan as “a decidedly intricate apparatus.”

The first support team left Camp Evans on October 24, 1911, on motorized tractors. They would transport food supplies to the One Ton Depot and wait for the rest of the crew. However, the motor vehicles broke down 50 miles short of their destination and men had to haul 660 lbs. of supplies to the depot. This, along with the adverse weather slowing down the other teams, determined a significant delay for the departure from the One Ton Depot, which took place on November 24. Scott sent back the first two men, but, in contrast with the original plan, decided to keep the dogs regardless of the additional supply they would have to use in feeding them.

The group was camped about 12 miles from the Beardmore Glacier when it was hit by a blizzard, which would not allow marching to resume until December 9 and forced the consumption of food that was destined for the trail on the glacier. All ponies were killed before leaving and their meat was partly laid in a depot, partly loaded on the sleds. There, Scott ordered another team to bring back the dogs on December 11 and to refill the depots on the return. The remaining men reached the top of the glacier on December 20 and laid down a depot. At the moment of the second-to-last team split, Scott changed his plans again and ordered all the scientific staff to leave, bringing forward only the military men, some of whom had been his companions in the Discovery expedition. The eight-man group reached 87° 34′ South on January 4. Just before parting ways, Scott announced that Edgar Evans, formerly assigned to the last support team, would join him and the other three members of the final team to reach the Pole, making it a five-man group. This completely overlooked the need for extra supplies for a fifth man. The following day, Scott reported in his diary:

“Cooking for five takes a seriously longer time than cooking for four; perhaps half an hour on the whole day. It is an item I had not considered when re-organising” (Scott 2006, 365).

Favored by the good weather, the final team got in sight of the Pole on January 16. The flag they saw in the distance spoke for itself.

“It is a terrible disappointment. Many bitter thoughts come... Tomorrow we must march on to the Pole and then hasten home with all the speed we can compass. All the day dreams must go; it will be a wearisome return” (Mickleburgh, 1987, 92).

Yet not all the romantic British spirit was gone from the party, as Henry Bowers reported:

“It is said that we have been forestalled by the Norwegians, but […] we have done it by good British man-haulage […] and this is the greatest journey done by man since we left our transport at the foot of the Glacier” (Huntford 2000, 496).

They reached their destination the following day: Once they ascertained their position and planted the British flag, Scott ordered to start the return immediately. The team proceeded at a good pace for three weeks, averaging more than 12 miles per day. Yet summer faded, temperatures plummeted, and the group found itself in trouble in reaching the depots. They reached the Beardmore Glacier depot on February 7. Against all the odds they were already facing, Scott decided they should spend a half-day collecting geological samples: as a result, they increased their load by more than 30 lbs. During the descent, Evans started suffering from frostbite and rapidly incurred a sharp physical and morale decay. He fell repeatedly in crevasses and then died from wounds received at the foot of the Beardmore Glacier. The march through the barrier was made even tougher by a further drop in temperatures. Scott reached the 82° 30’ S planned meeting point with two support dog teams, on February 27, three days ahead of schedule:

“We are naturally always discussing possibility of meeting dogs, where and when, etc. It is a critical position. We may find ourselves in safety at the next depot, but there is a horrid element of doubt” (Scott 2006, 380).

By March 10 it became evident that the dog teams were not coming and Scott estimated that they had food for seven days, but One Ton Depot was nine marching days ahead:

“The dogs which would have been our salvation have evidently failed.Meares had a bad trip home I suppose. It’s a miserable jumble” (Huntford 2010, 292).

Food and water supplies were running out and all three explorers had started suffering badly from dehydration, malnutrition, and scurvy. It became clear that the distance between the depots was too great for what the team could achieve in such bad conditions. On March 17, Oates, distressed by a frostbitten foot and a reopened wound, voluntarily left the tent and walked to his death. Scott reported in his diary:

“Oates took pride in thinking that his regiment would be pleased with the bold way in which he met his death… We knew that poor Oates was walking to his death, but… we knew it was the act of a brave man and an English gentleman” (Huntford 2000, 295).

On March 20, nine miles short of the depot, the three-man party was hit by a fierce snowstorm: They would refuge in their tent and never be able to move from it. The support teams marched back twice on the barrier, looking for their fellow explorer on the return. A first two-man party with dogsleds, the only means for transport left available, reached the One Ton Depot on March 1 for a refill. Due to scarcity of food for their dogs, they would not dare to go further to reach the 82° 30’ S, as envisaged by Scott’s plan. They waited for Scott for 10 days, but then had to surrender to the shortage of supplies and to the bad health of one of the explorers. On March 26, lacking any news of their mates, another party left Hut Point to be stopped shortly after by the untamable weather and the extreme cold. Atkinson reported: “Inmymind,Iammorallyconvincedthattheteamisdead.” Scott mounted the TerraNova expedition. He made it to the South Pole, but only after Amundsen from Norway had planted the Norwegian flag. Scott and all four members of his expedition team perished. Below is the last picture of the party alive.

Figure 2: The Last Known Picture of the Scott Expedition at the South Pole

Source: Adapted from Huntford (2000)

Amundsen

Amundsen had his first contact with Antarctica in the years between 1897 and 1899, when he took part in the Belgian Antarctic Expedition. During his sails beyond the Antarctic Circle, the ship Belgica got stuck in the ice at the end of February 1898. The crew faced the winter improvising with the scarce and inadequate equipment they had at hand. Amundsen himself, along with the ship doctor, Dr. Cook, would take the lead of the expedition due to the severe scurvy affecting the captain and the first official. The correlation between deficiency of vitamin C and scurvy was still unknown, yet Dr. Cook had realized that eating fresh penguin and seal meat prevented the illness. In fact, the crewmembers that ate it never fell ill, while the captain and the first official, who despised the flesh of native Antarctic animals, were hit hard by the disease. The ship would difficultly tear loose of the ice in the spring of 1899 and eventually sailed back to Europe.

In 1905-1906, Amundsen led the first quest for the Northwest Passage on the Gjoa ship, between the Baffin Bay and the Bering Strait. On this expedition, his leadership skills were already obvious:

“We have established a little republic on board Gjoa…After my own experience, I decided as far as possible to use a system of freedom on board – let everybody have the feeling of being independent within his own sphere. In that way, there arises – amongst sensible people – a spontaneous and voluntary discipline, which is worth far more than compulsion. …The will to do work is many times greater and thereby the work itself. We were all working towards a common goal and gladly shared all work.” – Amundsen, (Huntford 2000, 84)

“I remember, that he used ‘we’ and ‘ours’ …it was not his expedition but ‘ours’ – we were all companions and all had the same common goal” – Wisting, Amundsen expedition, (Huntford 2000, 287)

“No orders were given, but everyone seemed to know exactly what to do.” – Crewmate on Gjoa, (Huntford 2000, 84)

Following this venture, the Norseman shifted his focus on the North Pole, determined to be the first to reach it. After several difficulties in getting financial support for the expedition and with preparations already at an advanced state, the news that the North Pole had been conquered by the Americans arrived. At this point, his attentions quickly shifted to the South Pole:

“At the same instant I saw quite clearly that the original plan […] hung in the balance. If the expedition was to be saved, it was necessary to act quickly and without hesitation. Just as rapidly as the message had travelled over the cables I decided on my change of front — to turn to the right-about, and face to the South”. (Amundsen 2010, 39)

Amundsen needed a crew. He reflected much on how to choose his fellow explorers:

“There are advantages and disadvantages in having experienced people with one on an expedition like this.The advantages are obvious […].The experience of one man will often come in opportunely where that of another falls short.The experiences of several will supplement each other, and form something like a perfect whole […]. The drawback to which one is liable in this case is that someone or other may think he possesses so much experience that every opinion but his own is worthless […]. In any case, the advantages are so great and predominant that I had determined to have experienced men to the greatest extent possible. It was my plan to devote the entire winter to working at our outfit and to get it as near to perfection as possible” (Amundsen 1929, 51)

Amundsen learned from the native Netsilik Inuit how to build igloos and use seal and reindeer hides to keep warm during days that would freeze those in conventional expedition clothing.

He also paid huge attention to food: Nutrition was the base for healthy men and animals, and the worst enemy of long sails and expeditions was scurvy. Mindful of his experience on the Belgica, Amundsen chose to call on Professor Sophus Torup, who had supervised the ventures of Nansen’s Fram (the ship Amundsen would use) and of his own Gjoa, to plan carefully the organization and storage of meat, both for the sail and the stay on the Antarctic continent. Another critical element was the choice of the sled dogs. Amundsen had already benefited the experience of Nansen, learning that Greenland dogs were the best bet. He traveled to Copenhagen to meet with two inspectors of the Greenland Royal Commerce. The director Rydberg approved Amundsen’s plan and provided him with 100 of the best sled dogs. Sleds, skis and sticks were purchased directly in Norway from the respective top manufacturers, based on accurate advices of experts of each individual equipment piece (e.g. the chosen skis were narrow, but more than 8 ft. long, to ensure higher safety and better resistance on the insidious snow covering ice rifts). Amundsen selected expert skiers for the expedition, including a champion skier, Olav Bjaaland. During interviews to select a crew of 19 men, Amundsen looked for abilities to interact well with other crew members and personalities suited for Antarctic expedition. In spite of the shortage of financial resources, Amundsen provided the clothing equipment firsthand. More than pure generosity, it was a safe way to ensure that the whole crew was adequately equipped. He personally and systematically followed the purchase of leathers, clothes, shoes, and sleeping bags, while asking for support of highly skilled professionals and experienced explorers.

Finally, he thoroughly studied all the available geographical materials about the coast of the Ross Sea, drawing most insights from the detections of previous excursions led by Ross and Shackleton. Knowing that Scott would start his quest from Cape Evans to follow the route Shackleton had marked when he reached the 88° S, Amundsen opted to set his camp base in the Bay of Whales, on the opposite side of the Ross Sea, over 400 miles away from Cape Evans. It was his deliberate intention to find a new way to reach the coveted destination and to avoid crossing ways with the British. Amundsen hoped for the best-case scenario but planned for the worst case. Scott simply hoped for the best case.

The Fram would enter the Ross Sea on January 14, 1911, and set the camp base Framheim (“house of Fram”) at the Bay of Whales. Amundsen had planned to winter there to start the expedition as soon as the favorable spring weather arrived. Once unloaded of its crew and its equipment, the Fram left Amundsen and his party to return the following year. The months spent at the Framheim were ones of restless work. Hunting sessions were held to ensure large supplies of fresh penguin and seal meat for both men and dogs, pits were dug to expand the spaces of the campsite, and the route-planning was started. Amundsen and his team carried out several exploring hikes with two main goals: to test the equipment and the dogs’ response, and to lay down the depots with the food supply that would support the team on its trip to and, more importantly, back from the South Pole. Moreover, a lot of work was put in improving the equipment further, based on the experience of those hikes. For example, some members of the team noted that the sleds could be made lighter without compromising either flexibility or resistance. Throughout the whole winter, the team brought the sleds from the original weight of 165 pounds to 48 pounds. Amundsen commented on the work ethic of the people surrounding him:

“Something more than patience and punctual performance of duty is displayed in such things as those of which I have been speaking; it is love of, and a living interest in, one’s work”. (Amundsen 2010, 84)

During the first days of September 1911, spring seemed to have arrived. After few days of hesitation to ensure that the unpredictable Antarctic weather would not trick him (temperatures kept increasing to -7.6 F°), Amundsen set to leave on September 8 with eight men, seven sleds, 90 dogs and food supplies for 90 days. However, on September 11, the team woke up in a freezing -67.9 F°. The following days brought windstorms and blizzards, which proved extremely challenging for both men and dogs. Realizing the animals would not keep up with such severe conditions, the party agreed to head back to Framheim as they reached the first depot. The pitiless weather on the return claimed the lives of two dogs, and two explorers suffered from frostbite.

This disastrous false start triggered a bitter confrontation between Amundsen and Hjalmar Johansen, who had already showed signs of disapproval of Amundsen’s leadership during the winter. He complained about his inadequate equipment and starkly disagreed on starting the march on September 8. (Roald eventually had enough of Johansen’s insubordination and excluded him from the final team to depart for the Pole.) Nevertheless, the false start pushed Amundsen to revise his calculations. At the next departure from the Framheim, on October 20, 1910, the party accounted five men, four sleds, 52 dogs and food supplies for 120 days.

It took them 15 days (until November 5) to reach the depot at the 82° South. They then proceeded by 50-mile daily stages, regularly unloading food at every latitude degree:

“[…] we decided to build beacons at every fifth kilometre, and to lay down depots at every degree of latitude. Although the dogs were drawing the sledges easily at present, we knew well enough that in the long-run they would find it hard work if they were always to have heavy weights to pull. The more we could get rid of, and the sooner we could begin to do so, the better”. (Amundsen 2010, 250)

On November 17, the party reached the 85° S and the crevassed mainland, which would still not create any significant problem to their advance. Once they reached the first undulations of the Antarctic continent, they laid down their biggest depot, with supplies for 30 full days. They still had food for 60 days left on their sleds. Before them were now two mountain ranges peaking up to more than 13,000 feet. In order to get to the 86° S, they had ascended to the Ross Plateau, where they were hit by a terrific snowstorm. They had to stall for four days, laid another depot, and resumed their march on the fifth day, when the weather finally softened. Over the next few days, the party fought blizzards and fog, in what would have been an already insidious march through the Devil’s Glacier:

“A blinding blizzard raged from the south-east, with a heavy fall of snow.The going was of the very worst… If this part of the journey was trying for the dogs, it was certainly no less so for the men. If the weather had even been fine, so that we could have looked about us, we should not have minded it so much, but in this vile weather it was, indeed, no pleasure”. (Amundsen 2010, 289)

On December 14, 1911, the Norwegian flag was planted at the South Pole. The actual duration of the expedition was 99 days, one day shorter than planned. All members of the expedition survived.

“Pride and affection shone in the five pairs of eyes that gazed upon the flag, as it unfurled itself with a sharp crack, and waved over the Pole. I had determined that the act of planting it — the historic event — should be equally divided among us all. It was not for one man to do this; it was for all who had staked their lives in the struggle, and held together through thick and thin.This was the only way in which I could show my gratitude to my comrades in this desolate spot” (Amundsen 2010, 302)

They pitched a tent on Norwegian pennants and together hoisted the Norwegian flag on top of it.

Taking advantage of the good weather, they stayed on the Pole site for three days, recording, measuring, and observing everything that could prove the reach of their ultimate goal. The party would leave the South Pole on December 17:

“The going was splendid and all were in good spirits, so we went along at a great pace. One would almost have thought the dogs knew they were homeward bound”. (Amundsen 2010, 310)

They reached Framheim on January 25, 1912, all in good health and with 11 dogs. Below is the route traversed by Scott (green), and Amundsen (red).

Figure 3: The Race between Scott and Amundsen

Source: Adapted from Huntford (2000)

Analysis: Supporting Performance

Amundsen distinguished himself for his transformational and empowering leadership style. He matched the ability to select excellent experts with full trust and humility. Consider the respect he shows for captain Nilsen in his notes of praise:

“Captain Nilsen showed himself to be a veritable magician … While I contented myself with reckoning dates, he did not hesitate to go into hours … There was not much wrong with that estimate”. (Amundsen 2010, 45)

Bring also the attention on his sentences relative to his participation to the oceanography class of Professor Hansen, where Amundsen shows some self-irony:

“I myself had spent a summer [at the Bergen biological station], and taken part in one of the oceanographical courses. Professor Helland–Hansen was a brilliant teacher; I am afraid I cannot assert that I was an equally brilliant pupil”. (Amundsen 2010, 56)

These words express both objective recognition of these experts’ value, as well as sincere appreciation for their action and expertise. Further, he stimulated and valued ideas and initiatives of his own crew. Consider the episode of Amundsen and his peers spending the Antarctic winter relentlessly working on the improvement and perfection of their equipment:

“Something more than patience and punctual performance of duty is displayed in such things as those of which I have been speaking; it is love of, and a living interest in, one’s work”. (Amundsen 2010, 84)

Such leadership style had two major benefits. First, Amundsen could gather truly expert insight to support him in setting proper and accurate goals (e.g. Nansen, Hansen, Torup) and approaching the Pole (Nilsen). Yet, sharing the leadership did not detriment Amundsen’s authority among his peers: He would remain the ultimate decision-maker and a strong boss, who would not shy away from imposing his unchallengeable judgement when needed.

Second, allowing his peers to actively participate in the decision-making process and in the constant improvement of several aspects of the expedition allowed to build a strong team identity and cohesion. In his own diary records of the race to the Pole, Amundsen always wrote “we” instead of “I,” also when reporting the decisions of laying down depots. He also takes time and words to express his own admiration for his passionate crew and the feeling of pride and joy they all shared in working and accomplishing their goal together.

Amundsen reveals himself as a leader who was capable of building a strong and cohesive team, which he considered for the individuality of each member and that he fully empowered to bring any idea and input that could make the performance better. Finally, in recognizing the accomplishment of the team, he praises the members and rewards them by sharing the success.

Scott’s style was opposite to that of Amundsen. A militarist by tradition and led by a strong romantic spirit, Scott’s leadership was merely procedural. In the expedition letter calling for volunteers, Scott expresses that he should be the lone and undisputed leader and would not allow any other input. Yet, the members of the expedition team did not match such iron determination with equally disciplined action. Despite his peremptory approach, he did not put much effort into monitoring his staff. The most evident example during the preparation phase came when he recruited skiing expert Gran to train his crew, but did not ensure the training was attended. Further, his centralization of decision-making was so exasperated that he did not share thoughts and opinions with other members of the team, being perceived as secretive and detached from the action field. Lacking a clear vision, Scott missed opportunities to set supporting rules and routines for the team’s functioning. His inconsistent orders, lack of regard, and lack of sensitiveness for keeping the unit together would cost him some bitter thoughts from other members of the team.

The result was a disorganized unit that blindly depended upon the inputs of “the boss” and would not express any divergent opinion. Consider again the episode of Scott presenting his strategy to approach the Pole: His team accepted what he said in a status of behavioral disengagement, so that they would not even express their doubts and perplexity on a critical strategic plan that would actually determine the final outcome of the work (which, in this particular case, directly involved their own survival).

Application of Intrinsic Motivation Framework

In order to better understand the ways through which Scott and Amundsen approached the setting of the decision-making processes within their team, it could be useful to rely on intrinsic motivation theory, which relies on the fact that individuals should satisfy their autonomy and competence to experience intrinsic motivation (Bunderson and Sutcliffe, 2002; Dahlin, et al., 2005; DuFrene and Lehman 2004; Edmondson, 1999; Larson, et al., 1996). In particular, on the basis of this framework, it is possible to point out different sets of motivational factors, which could be focused on the activity that should be performed, on the scope of the activity, as well as on the reward (as an opportunity or as a self-fulfilling situation).

Autonomy refers to the member’s sense of having choice in determining and regulating the actions in performing a task. Thus, autonomy reflects the ability to make decisions about work methods, pace, effort, etc.

Self-efficacy represents the member’s belief in his or her capability to perform a certain activity. In other words, it refers to the individual belief of an individual that he/she can be effective with the available resources.

Meaning refers to the individual perception that the tasks he/she is performing are important, valuable, and worthwhile. The individual perception of meaningfulness is tied to own and subjective ideals or standards.

Impact reflects the degree to which a team member can affect strategic, administrative, or operating outcomes in the accomplishment of his/her role tasks. It is connected to the perception that the individual is producing work that is significant and important for the team success.

The intrinsic motivation lens could help to outline that, while Amundsen pushed intrinsic motivation by leveraging on the different pillars, Scott was much more reluctant in triggering intrinsic motivation in his team members. To better explain the impact of intrinsic motivation drivers, it could be useful to analyze Scott’s and Amundsen’s behaviors in terms of shared leadership approach. Shared leadership can be defined as the occurrence of leadership influence distribution across the members of the team (Spreitzer, 1995). In case of high levels of shared leadership, mutual influence is embedded in the way through which team members interact, as well as on the way the team leader approaches the decision-making process. The shared leadership approach could be considered as the opposite of the vertical command and control attitude, which emphasizes the status of the leader as hierarchically superior and uniquely responsible of team members’ interactions and output (Bunderson and Sutcliffe, 2002; Dahlin, et al., 2005; DuFrene and Lehman 2004; Edmondson, 1999; Larson, et al., 1996). Within the continuum between vertical (leader-centered) leadership and a team with a total shared leadership – where each individual can influence the processes of goal definition, ways to achieve the team goal, as well as norms and culture of the team – it is clear from the cases presented earlier, Amundsen embodied more traits from the shared leadership approach.

Enablers of Success

While Amundsen’s style of leadership was very participatory, Scott was a more distant leader with a hierarchical military style. Amundsen was not looking for a collection of individual bests – he worked with his men to innovate the way they did things, such as the development of new goggles. Scott did not. Amundsen understood the importance of identifying people who would work well together. He learned from the Inuit and translated this learning and planning into detailed preparations for food and supplies (Huntford, 2000). His supply depots were significantly closer to one another and better stocked than Scott’s depots. He also relied on fewer men who possessed the particular skiing skills needed to move swiftly on the ice and snow. His expedition was much more focused on the singular goal of reaching the South Pole. Scott, on the other hand, frequently changed plans at the last minute. His supply depots were underprepared, and he discounted the use of dogs because of his terrible experience using them in the past. He did not filter this bad experience through the reality that the crew did not have the skills or training to use dogs effectively. Scott used ponies and motor sledges, neither able to perform well on the Antarctic terrain. Amundsen relied on skis and dogs, and a small crew that was experienced in their use (Huntford, 2000).

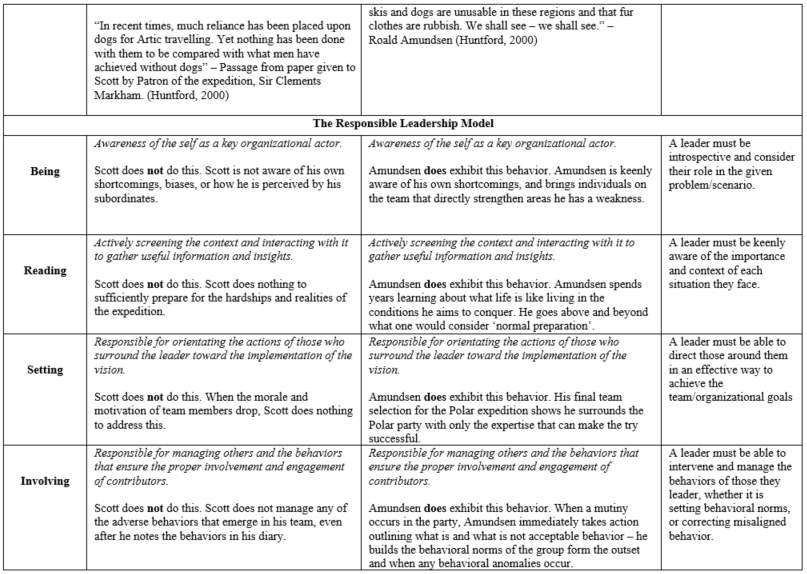

The positioning of this paper provides opportunities for frequent references back to the style of leadership. This paper allows us to ask the question: What was it about Amundsen that enabled success, while Scott’s TerraNova expedition led to the deaths of Scott and several of his team members? The leadership-style contrast is quite sharp between Amundsen and Scott. Table 1 below highlights the key differences between Amundsen and Scott along the critical components of leadership, i.e. planning, team selection, interaction with subordinates, and technology.

When considering the Responsible Leadership Model presented earlier, we can see that Scott violates the principles (Being – the awareness of the self as a key organizational actor; Reading – actively screening the context and interacting with it to gather useful information and insights; Setting – responsible for orientating the actions of those who surround the leader toward the implementation of the vision; and Involving – responsible for managing others and the behaviors that ensure the proper involvement and engagement of contributors) of the model universally. Amundsen, on the other hand, through the evidence presented, embraced all of the aspects of the model one might hope and expect a leader to embrace.

Table 1: Comparison of Leadership Style/Responsible Leadership Model

Conclusion

The goal of this paper is to stimulate discussion of some basic differences in leadership style and to highlight the importance of embracing adaptive change. The author has used this narrative in executive MBA classes to set the stage for thinking about the need for detailed planning and process-orientation, as well as participative and inclusive leadership during painful change scenarios. The author wishes to reiterate the challenges of leading people through an adaptive-change process. Feelings of loss, disloyalty, and incompetence have an impact on human identities (Heifetz and Linsky 2002). A leader often cannot avoid those challenges in running a change process in an organization. In light of what has been outlined above, this paper offers insights for supporting managers and organizations in designing effective cross-functional teams by relying on the specific set of competences of different members. Specifically, the case outlines three main pillars that should be considered in embracing a team-leader role:

(1). The awareness of one’s own strengths and weaknesses, as well as his/her ability to effectively read and frame the issues and challenges the context presents, are critical prerequisites for effective leadership;

(2) The leader should be able to build his/her team on the basis of the environmental needs, assigned goals, and coverage of his/her own skills liabilities (i.e. complementary approach in designing the team (Bunderson, 2003));

(3) The leader should focus on the long-term survival of the team by involving the members and developing them for facing challenges on their own.

References

- Amundsen, R. 1929. The South Pole: An Account of the Norwegian Antarctic Expedition in the” Fram,” 1910-1912. J. Murray.

- Amundsen, R. 2010 The south pole. BoD–Books on Demand.

- Ancona, D. G. 1990 Outward bound: Strategies for team survival in an organization, The Academy of Management Journal, 33(2), pp. 334-365.

- Ancona, D., Malone, T. W., Orlikowski, W. J., & Senge, P. M. 2007. In praise of the incomplete leader. Harvard Business Review, 85(2), 92.

- Cherry-Garrard, A. 1989. The worst journey in the world. New York: Carroll & Graf.

- Bown, S. R. 2012. The last Viking: the life of Roald Amundsen. Da Capo Press.

- Bunderson, J. S. 2003 Team member functional background and involvement in management teams: Direct effects and the moderating role of power centralization, The Academy of Management Journal, 46 (4), pp. 458-474.

- Bunderson, J. S., Sutcliffe, K. M. 2002 Comparing alternative conceptualizations of functional diversity in management teams: Process and performance effects, The Academy of Management Journal, 45(5), pp. 875-893.

- Cannon-Bowers, J. A., Salas, E., & Converse, S. 2001. Shared mental models in expert team decision making. Environmental Effects of Cognitive Abilities, 221-245.

- Caporarello, L., Magni, M. 2016 Team management, EGEA, Milan. Second Edition.

- Carson, J. B., Tesluk, P. E., & Marrone, J. A. 2007. Shared leadership in teams: An investigation of antecedent conditions and performance. Academy of management Journal, 50 (5), 1217-1234.

- Cullen, K. L., Gentry, W. A., & Yammarino, F. J. 2015. Biased Self‐Perception Tendencies: Self‐Enhancement/Self‐Diminishment and Leader Derailment in Individualistic and Collectivistic Cultures. Applied Psychology, 64(1), 161-207.

- Dahlin, K. B., Weingart, L. R., Hinds, P. J. 2005. Team diversity and information use, The Academy of Management Journal, 48(6), pp. 1107-1123.

- De Dreu, C. K. W., & West, M. A. 2001. Minority dissent and team innovation: The importance of participation in decision making. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(6), 1191-1201.

- DuFrene, D. D., Lehman, C. M. 2004. Building High Performance Teams, South-Western College Publishing, 2 edition.

- Edmondson, A. 1999. Psychological safety and learning behavior in work teams, Administrative Science Quarterly, 44(2), pp. 350-383.

- Goffee, R., and G. Jones 2000. Why should anybody be led by you? HarvardBusinessReview 78(5): 62–70.

- Hackman, J. R. 2002. Leading Teams: Setting the Stage for Great Performances, Harvard Business School Press.

- Heifetz, R., and M. Linsky 2002. Leadershipontheline:Stayingalivethroughthedangersofleading. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press.

- Heifetz, R., A. Grashow, and M. Linsky 2009a. Leadership in a (permanent) crisis. HarvardBusiness Review 87(7): 62-69.

- Heifetz, R., A. Grashow, and M. Linsky 2009. The practice of adaptive leadership. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press.

- Huntford, R. 2000. “The Last Place on Earth: Scott and Amundsen’s Race to the South Pole. London. Abacus (2000): 546-7.

- Huntford, R. 2010. Race for the South Pole: the expedition diaries of Scott and Amundsen. A&C Black.

- Huxley, E., J., G. 1990. Scott of the Antarctic. U of Nebraska Press.

- Kets de Vries, M., Korotov, K., and Florent-Treacy, E. eds. 2007. Coachandcouch:Thepsychologyof making better leaders. New York: Palgrave.

- Kets de Vries, M. 2009. Reflectionsoncharacterandleadership. Chichester: Wiley.

- Kouzes, J., and B. Posner 1995. Theleadershipchallenge. San Francisco: Jossey Bass.

- Larson, J. R., Christensen, C., Abbott, A. S., & Franz, T. M. 1996. Diagnosing groups: Charting the flow of information in medical decision-making teams. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 71(2), 315.

- Lansing, A. (2015). Endurance: Shackleton’s incredible voyage. Basic books.

- Limb, S., and Patrick Cordingley, P. 1995 Captain Oates: soldier and explorer. London.

- Locke, E. A., & Latham, G. P. 2002. Building a practically useful theory of goal setting and task motivation: A 35-year odyssey. American psychologist, 57(9), 705.

- Magni, M. and Pennarola. F., 2015. Responsible Leadership: Creating well-being, development and long-term performance. EGEA, SDA Bocconi Collection

- Magni, M., Proserpio, L., Hoegl, M., & Provera, B. 2009. The role of team behavioral integration and cohesion in shaping individual improvisation. Research Policy, 38(6), 1044-1053.

- Mickleburgh, E. 1987. Beyond the frozen sea: visions of Antarctica. Vintage.

- O’Brien, J. 2017. “Integrating the Cultural Perspective into two Knowledge Management Frameworks”, Knowledge Management: An International Journal. Vol. 17, No. 1, pp. 22-35, ISSN: 2327-7998.

- O’Brien, J. 2016. “The Odd Couple: Knowledge Management and Endogenous Growth Theory – Using these theories as a basis for the Development of a Conceptual Interdisciplinary Framework”, Knowledge Management: An International Journal, Vol. 16, No. 2 pp. 1-20, ISSN: 2327-7998.

- Purcell R, and O’Brien, J. 2015. “Unitas: Towards a Holistic Understanding of Knowledge in Organizations – A Case Based Analysis.” Electronic Journal of Knowledge Management 13 (2): 142–54

- O’Brien, J. 2015a. “Ten Practical Findings from the Deployment of an Exploratory Knowledge Management Framework.” Vine: The Journal of Information and Knowledge Management Systems 45 (3): 397–419.

- O’Brien, J. 2015b. “An Examination of the Effects of using a Dedicated System for Learning, Capture and Reuse: The Case of User Productivity Kit at a Medical Device Company.” Knowledge Management: An International Journal 15 (2): 1–12.

- O’Brien, J. 2014. “A Knowledge Positioning Framework of Organizational Groups”, International Journal of Knowledge Engineering and Management 3 (7): 1–22.

- O’Brien, J. 2013a. “The Need for a Robust Knowledge Assessment Framework: Discussion and Findings from an Exploratory Case Study”, the Electronic Journal of Knowledge Management, 11(1): 93 – 106.

- O’Brien, J. 2013b. “Lessons from the Private Sector: A Framework to be Adopted in the Public Sector” in “Building a Competitive Public Sector with Knowledge Management Strategy”, Al-Bastaki, Y., and Shajera, A., (Eds), IGI Global

- O’Brien, J. 2013c. “The Construction of an Operational-Level Knowledge Management Framework”, 10th International Conference on Intellectual Capital, Knowledge Management & Organizational Learning, October 25th, 2013

- Preston, D. 1999. A First Rate Tragedy: Robert Falcon Scott and the Race to the South Pole. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

- Scott, R.F., 2006. Journals: Captain Scott’s last expedition. OUP Oxford.

- Wageman, R. 1995. Interdependence and Team Effectiveness, Administrative Science Quarterly, 40, pp. 145-180.

- Van Knippenberg, D., De Dreu, C. K., & Homan, A. C. 2004. Work group diversity and group performance: an integrative model and research agenda. Journal of applied psychology, 89(6), 1008.

- Spreitzer, G. M. 1995. Psychological empowerment in the workplace: Dimensions, measurement, and validation. Academy of management Journal, 38(5), 1442-1465.

- Walsh, J. & O’Brien, J. 2017. “A Knowledge-based Framework for Service Management”, The Journal of Information and Knowledge Management. Vol. 16, No. 4, pp. 1-31, ISSN: 0219-6492.

Cite This Work

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing stye below:

Related Services

View allRelated Content

All TagsContent relating to: "Management"

Management involves being responsible for directing others and making decisions on behalf of a company or organisation. Managers will have a number of resources at their disposal, of which they can use where they feel necessary to help people or a company to achieve their goals.

Related Articles

DMCA / Removal Request

If you are the original writer of this dissertation and no longer wish to have your work published on the UKDiss.com website then please: