The Role of Working Memory in Second Language Acquisition

Info: 7712 words (31 pages) Dissertation

Published: 21st Dec 2021

Tagged: LinguisticsPsychology

Introduction

Learning a second (or third, or fourth…) language is an enriching activity for a plethora of reasons. Firstly there is the social enrichment that access to another culture and its peoples brings. There is also the much debated “bilingual advantage” which has been linked with cognitive advantages such as a higher level of executive control. In fact, there is evidence that multilingualism contributes to a cognitive reserve that delays the onset of Alzheimer’s Disease (Schweizer et al., 2012). Furthermore, there is the economic cost to the UK’s uniquely high level of monolingualism within Europe. In 2013, it was estimated that the UK’s language skills deficit cost the economy a staggering £48bn a year equating to 3.5% of GDP (Foreman-Peck and Wang, 2013). In a post-Brexit Europe, multilingualism will be an asset to the UK in maintaining and nourishing vital international relations. Encouraging language skills should be a priority for any government as the benefits seep into many spheres; the personal well-being of its citizens, employment within the UK and international stability in this time of great uncertainty.

Some individuals are remarkably successful in acquiring additional languages. We often hear of Herculean language acquisition, with some individuals speaking dozens of languages. However, many of us are also monolingual. There is evidently a large range in human ability to acquire second languages. Language aptitude has been defined by (Stansfield, 1989) as the “prediction of how well, relative to other individuals, an individual can learn a foreign language in a given amount of time”. Second language acquisition (SLA) in adults is an important area of psycholinguistic research because if we can identify the qualities of successful language learners we can improve the teaching of second languages for all. For consistency, success is defined in this dissertation, as a high level of proficiency; near-native or native language acquisition, although for an individual learner success can range from conversational fluency to occupational mastery.

There are both cognitive (working memory, intelligence, attention to name a few) and social factors (such as education, motivation and age) that contribute to successful SLA. It is a combination of these factors that results in the success of one learner and the failure of another. While social factors are indeed important, there is a lot of variance in these different factors and this goes beyond the scope of this dissertation. Indeed, as Smith (1991) said, the cake of SLA is cognitive while the icing is social; this dissertation will focus on the cake.

Learning a Language

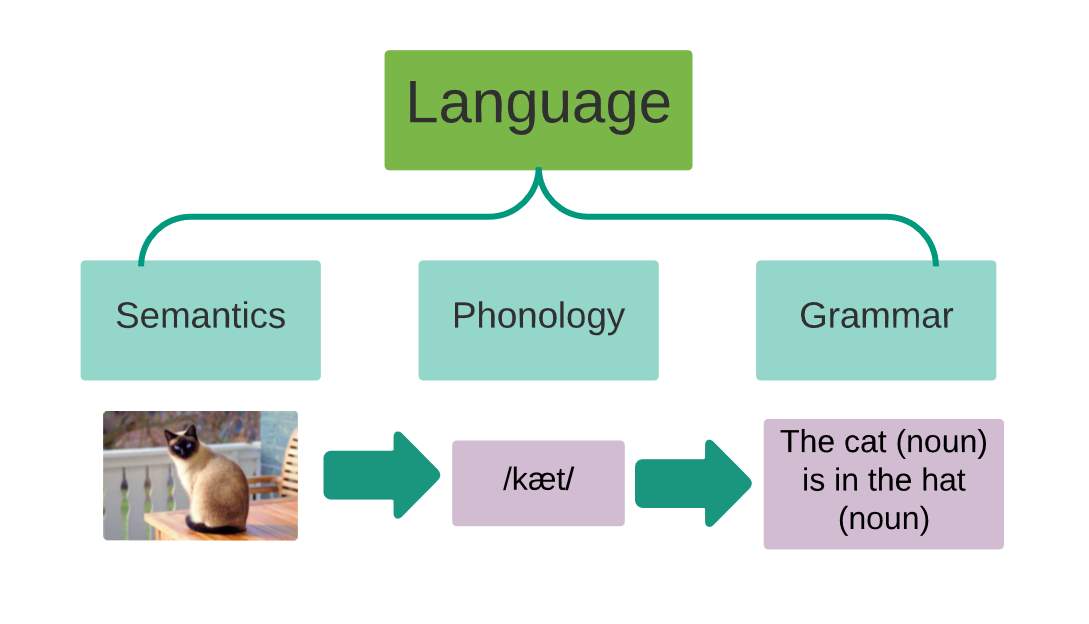

Figure 1 – What is language?

Language has three main characteristics that must be acquired; semantics, phonology and grammar. Semantics is the meaning behind language and L2 learners already have semantic knowledge. Phonology is the characteristic combinations of sounds in a language and grammar is a set of syntactic rules within a language. While there is clear overlap between L1 and L2 acquisition, L2 acquisition is distinct from L1 as learners do not need to re-learn semantic meaning, they only need to acquire new phonological labels and the language’s grammar. Additionally, after the critical period of language acquisition (between age 5 and puberty, Johnson and Newport, 1989) it is harder to acquire language and learners have a lower chance of success, resulting in a lower level of ultimate proficiency. These factors make L2 acquisition distinct.

Despite this, it has long been thought that differences in WM capacity are an important determinant of differential native language attainment in young children and it is claimed that the phonological loop component is a language learning device (Baddeley et al., 1998). It would naturally follow that the WM system may also be involved in adult SLA. This dissertation will consider the role of working memory in the successful attainment of second language proficiency in post-critical-period leaners.

Working Memory; Literature Review

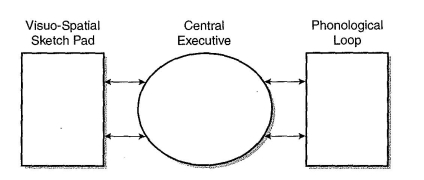

Working memory was first proposed by Baddeley and Hitch (1974) as a temporary store for incoming information, where this information could also interact with long term memory (e.g. for the purposes of language comprehension) and then be transferred to long term stores. This model consisted of three subsystems; the phonological loop (PL), the visuospatial sketchpad (VSS) and the supervising central executive. These subsystems have informational limits and these limits vary between individuals. It is debated whether this system is part of the larger system of memory or instead cognition (Unsworth and Engle, 2007) but it can be thought of to be comprised of a storage component and a processing component (Baddeley, 2000). Gathercole and Baddeley (2014) have hypothesised that WM is the gateway to language acquisition and so hypothetically variation in working memory capacity and processing power of individuals would lead to varying success in SLA.

Figure 2 – Baddeley Model of Working Memory from Baddeley (1986)

The PL component is by hypothesis critical to SLA and is said to be comprised of a phonological store and an articulatory control process. For acoustic information to enter the phonological store, it must first be encoded by the auditory system an ability called phonological coding ability. After it has been deciphered, the phonological store can hold 1-2 seconds of it, while the articulatory control process allows this information to be ‘refreshed’ and stay in the store longer through repetition. This system is also referred to as Phonological Short-Term Memory (PSTM). It is this system that has been most clearly implicated in SLA. However, the other 3 components also have their roles to play, although these roles are more enigmatic.

The VSS is also involved in the learning and reading of written language. Additionally, there is a third component called the episodic buffer that was added by Baddeley in 2000 which binds together information from the other stores and presents it in a ‘unitary episodic representation’. The model also includes the overseeing Central Executive (CE), which coordinates between the slave systems and controls information going in and coming out of them from long term memory. This dissertation will look primary at the role of the central executive and the phonological loop in SLA for the following reasons. Primarily, while the VSS does play a role in reading and writing, this is not the main route of language acquisition. Secondly, as the episodic buffer was a recent addition to the model, very little is known about its role in SLA. Thirdly, the processing component of WM, the central executive, must also be considered to determine if it is the sheer capacity of WM or the processing power that determines SLA success. These questions can be answered with the help of tests that question the nature of WM.

SLA Considerations in Measuring WM Capacity

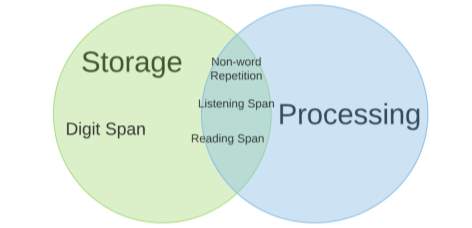

There are different methodologies used to investigate working memory that reflect that it is comprised of both a storage component as well as a processing component. The storage component of working memory can be measured using simple tasks whereas both components are called upon in more complex tasks.

Figure 3 – Tests of Working Memory

Simple tasks test an individual’s ability to recall information presented to them in list form. For example, the digit span test looks at an individual’s ability to recall a list of numbers that has been presented to them. However, the digits can often already be familiar to the subject and studies have found that the lack of cognitive demand means that little differentiation in ability is found, especially if the test is conducted in L1 (Akamatsu, 2008). On the other hand, conducting these lists in L2 may be confounded by the individual’s knowledge of the language and linguistic background. This has been solved by some studies by using an artificial language (Nayak and Gibbs, 1990) however problems with this methodology is that artificial languages need to be constructed very carefully to ensure that they are processed in a similar fashion to real languages by the brain. Simple tasks explore the storage capacity of the WM in the context of acquiring a new language.

A more demanding task that escapes artificial processing confounding is Non-Word Repetition (NWR). These tasks involve the presentation, memorization and recall of words that are phonologically but not lexically valid. This is a good way at looking at the capacity of WM with regards to SLA as it is much less likely to be confounded by previous exposure to the words. For non-words to be repeated, they must be phonologically processed, stored and then repeated, therefore the task does involve both the storage and processing component. Recall of non-words has been shown to be strongly and consistently linked to L2 outcomes in both adults and children (Baddeley et al., 1998; Hummel, 2009; Masoura and Gathercole, 1999; O’Brien et al., 2007) However, it is dangerous to assume that NWR abilities are directly measuring WM and the phonological loop, as there could be other cognitive processes underlying this and causing the variance in ability.

Even more demanding tasks can also be used to look at working memory, for example reading and listening tests. The Reading and Listening Span test (Daneman and Carpenter, 1980) are such tests that involve reading (or listening), comprehending and then recalling a specific part of the sentence. However, these tests can be confounded again by previous exposure and knowledge of the language. Other problems across this methodology include the inability to control for other factors that may cause differences in ability; intelligence, attention and social factors. Thus, these tests should be used cautiously in looking at WM in SLA, as if not carefully controlled they could be measuring other cognitive abilities.

A further problem is the interplay of WM and L2 outcome. It has been found that polyglots have larger WM capacities compared to monolinguals or bilinguals (Vallar and Papagno, 1993), but this is simply correlational, not causational. It is hard to distinguish if is increased WM that leads to ease at acquiring at multiple languages or the capacity and processing ability of WM is expanded by successive language acquisition. Additionally, it is also important to bear in mind that many languages are used in SLA research and that the way an alphabet language is learned is very different from a language such as Chinese. For such non-alphabet languages, preliminary research (Tong and McBride-Chang, 2010) has begun to show that language acquisition is more reliant on visual processing. Mapping the differences between languages is a laborious task as they need to be compared grammatically, phonologically and lexically and this is beyond the scope of this dissertation but I do acknowledge the importance of this and how this may relate to the VSS component of WM. It is thus important to bear in mind when considering evidence that while WM affects SLA, the reverse relationship may also be true.

In conclusion, there are a multitude of methods that can be used to investigate the relationship between WM and SLA. However, using only a single method, for example digit span, is limiting because it assumes that digit span is only measuring working memory. Consequently, in my opinion, the best approach to research considering WM and SLA would be to use a wide array of different tests to capture the array of abilities that might be measured on WM tasks while considering the acquisition of many different languages. Lastly, a key resource that has not been utilised is language centres. These centres would provide a readily accessible large pool of subjects, with a variety of backgrounds, for longitudinal study. If the large cohort were tested in WM capacity alongside L2 gains across their language study it could provide enough data to more clearly elucidate the direction of a causational relationship between the two.

The Components of Working Memory in SLA

Phonological Loop and Vocabulary Acquisition

The first evidence of the working memory system being involved in language acquisition came from studying patient PV (Baddeley et al., 1988). Patient PV had suffered from a left hemisphere stroke that resulted in impaired short-term memory. There was no impaired visual memory but an impaired phonological loop; the patient could only recall 2-3 digits compared to the average of 7 digits ± 2. The first experiment showed that the patient’s ability to learn pairs in her native language was intact whereas the second showed that she was not able to pair a word in her native language to a second word in a foreign language that she had studied in the experiment previously. These results suggested the learning of new words in native language involves semantic learning whereas the PL does play a key role in SLA.

These findings were expanded on by Papagno and Vallar (1992) through looking specifically at the link between PSTM and the learning of novel vocabulary. The 24 subjects were read out two lists of paired words where stimuli were the same syllable length but either phonologically dissimilar or similar (E.g. ‘volpe and segno’ compared to ‘tetto and berba). The other two lists, while matched for syllable length, paired a word with a non-word (a word generated by altering an existing word by a single word, tetto and zibro). The lists that were phonologically similar took longer to learn, for both non-word lists and word lists. A further experiment disrupted the articulatory control process (ACP) by preventing rehearsal, preventing the information from being stored in the phonological loop. Learning for the non-word lists dramatically reduced but not for actual word lists. This suggests that for novel foreign words, PSTM is important but learners are using other cognitive tools to learn words of their native language. The third experiment used lists with 2 or 4 syllable long words and non-words. They found that the longer syllable non-words have significantly lower rates of recall compared to comparatively long words. They hypothesised that this was because the ACP was impaired so the non-words could not be repeated. The strengths of this study were that they used a varied number of methods to look at the phonological loop but a limitation that was acknowledged that they could not control for the use of memory strategies or differences in attentional abilities. However, from this evidence, it is evident that at least initially, the rate of vocabulary learning is linked to the strength of the phonological loop.

PSTM and the Acquisition of Grammar

Having discussed vocabulary, it now makes logical sense to discuss the role of PSTM in the acquisition and abstraction of grammar. A language’s grammar is the rules that allow the construction of words into meaningful sentences. (Ellis, 1996a) argues that after a sufficient bank of L2 phonological labels has been acquired, then the same abstraction processes that have tuned the phonological system to L2 then are able to tune the grammatical system. The system becomes attuned to L2 word order and associations after building a lexical foundation. It naturally follows then that the phonological loop would also be involved in the acquisition in grammar.

In fact, Martin and Ellis, (2012) found that individual differences in ability to acquire vocabulary and grammar correlated between 0.44 to 0.76 (using different measures of language assessment) when exposing subjects to an artificial language. This suggests that there could be some overlap of the abilities required to acquire vocabulary. Additionally, the same study showed that working memory explained 17% of variance in vocabulary ability. Moreover, NWR, used here as a proxy for PSTM, accounted for 16% of the variance in vocabulary acquisition. Working memory also explained 14% of the variance in grammar production and non-word repetition explained 10%. This shows that both working memory and PSTM are correlated to both vocabulary and grammar acquisition, which are both correlated to each other. Age and years of formal language studied were also entered into regression data and did not explain any significant variance. However, this data should be interpreted cautiously, as all these factors independently relate to each other; grammar cannot be acquired without vocabulary and PSTM is not independent of working memory.

The role of PSTM in grammar acquisition and syntax has been much less studied than its role in vocabulary. It is the natural progression of the ideas discussed in this dissertation, to suggest that PSTM also underlies the mechanisms for syntax acquisition as well. Results from 3-year-old children (Adams and Gathercole, 1995) have found that good PSTM was correlated with longer utterances which were more grammatically complex but these results are not causational, just correlational. Similar results are also being found in adult learners. For example, (Ellis, 1996b) tested 87 subjects and found that those who were allowed to repeat the test words aloud, had a better ability to comprehend Welsh and also a greater metalinguistic knowledge of the Welsh grammatical regularities that they were exposed to. However, this is inconclusive as the articulatory suppression used in the experiment could have been interfering with other cognitive process as well as the articulatory control process, such as attention and analytic processes.

A more recent study (Williams and Lovatt, 2003) investigated the role of phonological memory and rule learning. They looked at how individual differences in phonological ability affected the ability to learn determiner-noun rules in semiartificial languages and real languages. The 20 native English-speaking participants were exposed to an artificial language and were required to abstract and learn rules from the exposure. PTSM was tested by asking the participants to repeat 5-item lists of unfamiliar Italian vocabulary. They were also tested on learning of the Italian words. Commendably, they also assigned Language Background scores based on each participants history of studying languages, which is a good variable to attempt to control for differential experience of language learning. They found that PSTM correlated significantly to vocabulary learning efficiency and suggested that the reason for this was that an ability to repeat novel phonological combinations was related to the ability to improve phonological representations. Additionally, they did find that language background was also related to PSTM, the theory being that those with more experience of foreign languages were able to call upon their broader phonological representations to repeat non-words. When the experiment was changed to use an artificial language, when controlling for the effect of morpheme learning by using familiar morphemes, phonological memory was found to be significantly correlated to rule learning. The authors suggested that a better ability to capture, analyse and store morphological representations leads to an improved ability to abstract rules from them. However, to understand how grammar is forged from WM, grammar rules across many languages need to be studied, both familiar and non-familiar to the individual. This would help us elucidate how the language learning system abstracts rules from PSTM.

Limitations to the Role of PSTM in Second Language Acquisition

Results from studies investigating the link between PTSM and SLA are not always consistent and therefore there are loud critics of the theory that WM is the gateway into language acquisition. For example, (Juffs, 2004) argues that the role of WM in SLA is overstated and that it should be considered within a larger toolkit of cognitive abilities that are used to acquire languages.

In support of this, there have been studies that have not found a link between PTSM span such as (Akamatsu, 2008) which looked at the relationship between word span and gains made in word recognition over 7 weeks of training. No evidence was found for a link between WM and gains in reaction time to word recognition. The author commented on the lack of cognitive demand on simple word span test which meant that different mechanisms, such as automation, were underlying acquisition. He further hypothesised that more demanding tasks would give those with high WM capacities an advantage as less demanding tasks do not challenge participants enough to reveal the link between WM and SLA.

Additionally, further evidence from a recent meta-analysis (Linck et al., 2014) sheds further light on the magnitude of the relationship between WM and SLA. 79 samples were used comprising a total of 3,707 participants. This study found a positive correlation between WM and L2 proficiency outcomes with the effect size being .255. A strength of this meta-analysis was the differentiation between the storage component of WM and the central executive. While both components were correlated positively with L2 skills, there was a stronger link between executive function and outcomes. It was also found that Verbal STM capacity was a better predictor of L2 skills than non-verbal STM capacity, which hints at the lesser role of the VSS in SLA. These results call for more detailed study of the individual components of Baddeley’s WM model and their relationship with SLA. Additionally, there are other cognitive abilities that may underlie SLA, such as general intelligence, attention and long-term memory. These cognitive abilities may also be connected to WM however, through the central executive.

The Role of the Central Executive in Second Language Acquisition

Having considered SLA in terms of the phonological loop, a slave system, it now is time to consider the master; the central executive. Research into the CE has been neglected compared to the rest of WM model due to its complex nature. Despite this lack of research, as the CE coordinates the three slave systems of WM it must be involved in language acquisition. There is still great discussion on if it works as one entity or it itself has overlapping subsystems. This dissertation will consider some of its main facets; access to long term phonological memory, role in general intelligence and language analytic ability.

The Central Executive as the Gate Keeper to Long Term Phonological Memory

At higher stages in SLA, (Robinson, 2005) proposes that cognitive differences, such as WM capacity differences, are weak indicators of success. This view has been supported by experimental evidence. For example, (Gathercole, 1995) observed that the capacity for the immediate repetition of nonwords is enhanced when they are comparatively word-like in structure, indicating a clear influence of prior word knowledge on immediate memory. Furthermore, in (O’Brien et al., 2007) it was also found that amongst high proficiency bilinguals digit span didn’t correlate with improved results. This data suggests that the interplay of the CE and PL may be involved in later stage SLA.

Hypothetically, a good ability to build representations about non-words, improves the ability to recall them; phonological coding ability, one of the four factors that constituted language aptitude in the seminal works of Carroll (Carroll, 1990; Carroll and Sapon, 1959). It is possible that this reflects the ability of the CE to make similar auditory information available to PSTM. This is also likely where knowledge of other languages and the relationship between the speaker’s native and L2 (Or L3, L4…) is likely to interact with SLA. According to MacWhinney’s Competition Model, (MacWhinney, 1997), initially, learners are hindered by L1 but gradually as language is acquired, the learner constructs his own network and categories of lexicon for L2. However, (Beebe, 1988) does argue that instead of acquiring a discrete network for L2, L2 is simply mapped on and learnt in terms of the native language. These results are further supported by a cluster analysis of 208 students (Sparks et al., 2012). From this study, it was reported that L2 achievement prior to L2 exposure was strongly and consistently related to L1 proficiency. Thus, it may be that good PSTM underlies both successful L1 and L2 acquisition. This relationship should be examined in more detail as it is critical to elucidating the role of WM in SLA.

The Central Executive and Previous Language Experience

The relationship between the learner’s native language and L2 while certainly important is not clear. Light may be shed on this relationship if it is seen through the lens of the CE. Bhela (1999) acknowledged this and designed an experiment whereby the participants were asked to tell stories in both their native language and in English. Through analysis of language errors in both L1 and L2, the study found that similarity between L1 and L2 is helpful, differences hinder learning. As the study only had four participants and four languages it would be unwise to extrapolate these results across all SLA. However, it does illustrate that it is important to acknowledge that previous knowledge of languages have impact on SLA.

Further considering this effect of previous language experience, Papagno and Vallar (1995) looked at individuals that already spoke three languages or more in Italy. Ten polyglots were tested alongside ten monolinguals. The polyglots had significantly superior ability to repeat non-words compared to the monolinguals. General intelligence and vocabulary in the two groups was said to be comparable. While these results are correlative, they are not causative as it could be that language acquisition expands WM by giving polyglots the advantage of a larger library of acquired phonology through the CE. Although the sample size was small, it does seem to suggest that language aptitude may be linked to a highly functional phonological loop. Further experiments need to be done to isolate the direction of the relationship between language learning, PSTM and the CE.

Consequently, (Gathercole and Martin, 1996) instead suggest that it is not the capacity of the PSTM that is important in language acquisition, but representations ‘built from the perceptual analysis process’. The better this process, coordinated by the central executive, the better the chance of correct output and recall. This hypothesis would fit better with the results of (O’brien et al., 2006). It is possible that instead of relying on the sheer capacity of the PSTM, skilled learners are better at encoding and translating new phonology by comparing and aligning it with lexicon that has already been well established due to prior L2 experience. Further experience would gradually refine the library of phonological long-term memory which allows new entries to be incorporated more efficiently and more rapidly. The advantage of not having immediate transfer to long-term memory is that it gives the new ‘entry’ time to be considered with exisiting vocab, allowing it to be more precisely placed in a neural map, close to similar already existing vocabulary. While the process starts in the hands of PSTM, the SLA process is coordinated and PLTM is brought in by the central executive.

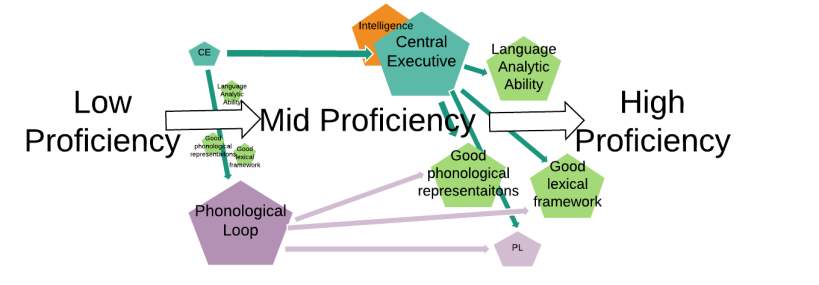

Thus, it is likely that working memory is critical to second language acquisition but that different components have different functions at different points. Initially, it may be that it is the phonological short-term memory that is responsible for successful language learning but then to attain higher levels of proficiency this is then supported by the central executive. However, it is also possible that when considering SLA, it could be a completely different cognitive ability outside of WM that is underlying late stage SLA success.

The Central Executive and Grammar

Additionally, the acquisition of grammar has also been linked to language analytic ability (LAA) which may be a subsystem of the central executive. Harley and Hart (1997) looked at the relationship between different L2 aptitude components and L2 outcomes. They looked at associative memory, memory for text and analytical ability and L2 outcomes in 65 11th graders. Proficiency was measured in an impressive number of ways; vocabulary recognition, listening comprehension, a cloze test, written production task and an individual oral test. The 65 participants were split into a group that were immersed early from 1st grade and a group that were immersed late from grade 7. For early immersion students proficiency was correlated to the memory tasks whereas for the late-immersion learners LAA was a significant positive predictor of proficiency. This research suggests that after the critical period, language analytic ability, and therefor possibly the CE, may be as important as working memory in acquiring additional languages.

A recent meta-analysis (Li, 2015) looked at the associations between the different components of language aptitude and L2 outcomes. The author found that language analytic ability was more predictive of grammar learning than phonetic coding ability and wrote memory across 33 study reports and 3,106 L2 learners. Additionally, the author found that overall language aptitude was more important in the earlier stages of learning than later stages. This could suggest that at high proficiency levels there are other mechanisms, involving the CE, at work through which high proficiency language is acquired. However, it is important to bear in mind that LAA could also be a manifestation of other cognitive faculties such as problem solving, abstract thinking or creative thinking. This dissertation will consider this relation to the role of general intelligence in SLA.

The Central Executive and General Intelligence

It has been long argued by many critics that working memory and intelligence may actually be different measures of the same cognitive abilities. Consequently, this would mean that the central executive’s role in SLA is the same as that of general intelligence (Jensen, 1998; Kyllonen, 2002; Stauffer et al., 1996). It could be that it is in fact general intelligence that is at the heart of successful language acquisition and that it mediates this through the central executive. However, there are loud voices in this debate that argue that while the two are very significantly correlated (estimates from .995 in Stauffer et al., (1996) to .479 in (Ackerman et al., (2005)), they are separate constructs entirely (Unsworth and Spillers, 2010). Unsworth and Spillers, 2010 used confirmatory factor analyses to suggest that attention control, secondary memory and WM were all separate abilities that were each related general intelligence. They also found using structural equation modelling that part of the relationship between the two factors could explained by attentional control and secondary memory but also that WM accounted for variance in fluid intelligence independently. Therefore, the variance that is often attributed to WM in successful SLA could be a combination of both WM and general fluid intelligence. Engle et al., 1999 argues that this relationship is mediated by the Central Executive. This topic would be further illuminated by further research into if a strong CE increases WM capacity and if the CE is perhaps a form of intelligence by another name. By establishing this, it would help to elucidate which of these abilities is truly the driving factor behind differential SLA. In conclusion, it seems plausible that the CE component of working memory is at least strongly correlated with intelligence and that it may be g that is mediating the relationship between WM and SLA.

CONCLUSIONS

Conclusion 1; PTSM IS Involved and Important in SLA

In conclusion, from analysing the evidence through this dissertation, the PSTM is certainly central to successful and effective initial SLA. The evidence from meta-analyses particularly is convincing (Li, 2015, p. 20; Linck et al., 2014) at showing that the strength and robustness of this relationship, especially in the early stages of SLA.

However, there is doubt, and rightly so, that is the sole ‘gateway to second language acquisition’ that it has long been heralded to be. As (Juffs, 2004) rightly points out, the evidence is inconclusive but this may be linked to the wide range of methodologies used to study working memory. Another problem is that tasks of working memory often include a combination of storage and processing demands. (Linck et al., 2014) found from their meta-analysis, that the processing component of WM was most strongly correlated with L2 outcomes. Further research should focus at looking at a wider array of measures that capture other cognitive abilities and consider roles specific components of working memory are playing to address the gap of research around the central executive.

Conclusion 2; The Central Executive is Increasingly Important in Later Stages of SLA

Therefore, with this gap of research in mind, the second conclusion is that WM may influence and be related other cognitive abilities needed for SLA and that this influence is exerted through the CE. Linck et al (2014) found that high-level attainment was indeed related to working memory (namely PSTM) but also to associative learning and implicit learning in a sample size of 522 participants. Having previously considered how WM relates to other factors such as fluid intelligence and attention this suggests that SLA is the coordinated effort of a network of different nodes that are important at different stages of the process. This coordination is likely facilitated by the central executive component of working memory. For example, it seems that PSTM is initially very important in establishing the foundations of L2, but as these are built, long term representations become more important in the high proficiency learner later in SLA. The interaction of incoming phonological information and PLTM is orchestrated by the CE and data suggests that it plays a key role in SLA.

Moreover, P. Skehan (1986) used cluster analysis technology to demonstrate different successful profiles of language aptitude with varying abilities. For example, one group of learners had high linguistic analysis ability and average memory while another had good memories but average linguistic analytic ability. The last group had average aptitudes for SLA but were still successful. This suggests that as well as different abilities contributing to successful SLA, varying combinations of these abilities could still lead to success. The last section of this dissertation will consider the more precisely the role of WM in the trajectory of SLA.

Figure 4 – Dissertation Summary of Working Memory’s Role in SLA

Conclusion 3; WM’s overall role in the Toolkit of SLA

From this dissertation, it seems likely that the phonological loop component is the most important initial factor in SLA, as details about linguistic form need to be abstracted. However, as a learner grows in confidence and proficiency they are able to construct solid lexical networks and phonological representations in L2. The phonological loop also has a role in the of grammar from these lexical networks.

Once a learner is sufficiently proficient, they switch over from relying on primarily the phonological loop, and their reliance is now on these solid L2 foundations and other cognitive abilities such as language analytic ability, a process that may be mediated by the central executive. This allows the faster processing of new inputs as they can be speedily aligned with exisiting L2 knowledge. The role of the different components of WM changes and evolves throughout the process of SLA.

Lastly, as we learn more about the nature of SLA, the roles of the VSS and EB may also be extracted. For this to happen, there needs to be both a unified cognitive account of how second languages are acquired and further development of the WM model. This would allow the models to be aligned and for a more precise role of WM to be revealed.

Application of Conclusions

Accurate specification of the exact role of WM in SLA will have clear benefits. Firstly, in terms of cognitive neuroscience, since language comprehension and production require coordination of many different brain systems, understanding WM’s role within this would shed light on the nature of WM itself and how the components operate together. In addition to this, it may provide insight into the nature of general intelligence and its relationship with WM.

Moreover, if all language learners were tested for different facets of language aptitude, such as WM and LAA, they could be profiled and taught in accordance with their results. For example, those with large phonological capacities would be taught in a way to utilise their advantage. This may prove more effective than assigning all learners to the same language course. Furthermore, I would argue that this approach could be extrapolated so that it recognises that different cognitive abilities are important at different stages. This may lead to the creation of very effective second language teaching courses.

Lastly, I would hope that by tailoring language courses to individual types of learner this would reduce attrition in language courses and increase the number of adults who successfully acquire a second language. In addition to this, lessons learned from SLA research could have wider implications for the processes that underlie learning in general and could have applications in the larger field of education.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Ackerman, P.L., Beier, M.E., Boyle, M.O., 2005. Working memory and intelligence: The same or different constructs? Psychol. Bull. 131, 30.

Adams, A.-M., Gathercole, S.E., 1995. Phonological Working Memory and Speech Production in Preschool Children. J. Speech Lang. Hear. Res. 38, 403. https://doi.org/10.1044/jshr.3802.403

Akamatsu, N., 2008. The Effects of Training on Automatization of Word Recognition in English as a Foreign Language. Appl. Psycholinguist. 29, 175–193. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0142716408080089

Baddeley, A., Gathercole, S., Papagno, C., 1998. The phonological loop as a language learning device. Psychol. Rev. 105, 158–173.

Baddeley, A., Papagno, C., Vallar, G., 1988. When long-term learning depends on short-term storage. J. Mem. Lang. 27, 586–595. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-596X(88)90028-9

Baddeley, A.D., Hitch, G., 1974. Working Memory, in: Psychology of Learning and Motivation. Elsevier, pp. 47–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0079-7421(08)60452-1

Beebe, L.M., 1988. Issues in second language acquisition: Multiple perspectives. Newbury House.

Bhela, B., 1999. Native language interference in learning a second language: Exploratory case studies of native language interference with target language usage.

Carroll, J.B., 1990. Cognitive abilities in foreign language aptitude: Then and now. Lang. Aptit. Reconsidered 11–29.

Carroll, J.B., Sapon, S.M., 1959. Modern language aptitude test.

Daneman, M., Carpenter, P.A., 1980. Individual differences in working memory and reading. J. Verbal Learn. Verbal Behav. 19, 450–466. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-5371(80)90312-6

Ellis, N.C., 1996a. Working memory in the acquisition of vocabulary and syntax: Putting language in good order. Q. J. Exp. Psychol. Sect. A 49, 234–250.

Ellis, N.C., 1996b. Analyzing language sequence in the sequence of language acquisition: Some comments on Major and Ioup.

Engle, R.W., Tuholski, S.W., Laughlin, J.E., Conway, A.R., 1999. Working memory, short-term memory, and general fluid intelligence: a latent-variable approach. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 128, 309–331.

Foreman-Peck, J., Wang, Y., n.d. The Costs to the UK of Language Deficiencies as a Barrier to UK Engagement in Exporting: A Report to UK Trade & Investment 56.

Gathercole, S.E., 1995. Is nonword repetition a test of phonological memory or long-term knowledge? It all depends on the nonwords. Mem. Cognit. 23, 83–94. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03210559

Gathercole, S.E., Martin, A.J., 1996. Interactive processes in phonological memory. Models Short-Term Mem. 73–100.

Harley, B., Hart, D., 1997. LANGUAGE APTITUDE AND SECOND LANGUAGE PROFICIENCY IN CLASSROOM LEARNERS OF DIFFERENT STARTING AGES. Stud. Second Lang. Acquis. 19, 379–400.

Hummel, K.M., 2009. Aptitude, phonological memory, and second language proficiency in nonnovice adult learners. Appl. Psycholinguist. 30, 225. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0142716409090109

Jensen, A.R., 1998. The g factor: The science of mental ability. Praeger Westport, CT.

Johnson, J.S., Newport, E.L., 1989. Critical period effects in second language learning: The influence of maturational state on the acquisition of English as a second language. Cognit. Psychol. 21, 60–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/0010-0285(89)90003-0

Juffs, A., 2004. Representation, Processing and Working Memory in a Second Language. Trans. Philol. Soc. 102, 199–225. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0079-1636.2004.00135.x

Kyllonen, P.C., 2002. g: Knowledge, speed, strategies, or working-memory capacity? A systems perspective. Gen. Factor Intell. Gen. It 415–445.

Li, S., 2015. The Associations Between Language Aptitude and Second Language Grammar Acquisition: A Meta-Analytic Review of Five Decades of Research. Appl. Linguist. 36, 385–408. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/amu054

Linck, J.A., Osthus, P., Koeth, J.T., Bunting, M.F., 2014. Working memory and second language comprehension and production: A meta-analysis. Psychon. Bull. Rev. 21, 861–883. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13423-013-0565-2

MacWhinney, B., 1997. Second language acquisition and the competition model. Tutor. Biling. Psycholinguist. Perspect. 113–142.

Martin, K.I., Ellis, N.C., 2012. The roles of phonological short-term memory and working memory in L2 grammar and vocabulary learning. Stud. Second Lang. Acquis. 34, 379–413.

Masoura, E.V., Gathercole, S.E., 1999. Phonological Short-term Memory and Foreign Language Learning. Int. J. Psychol. 34, 383–388. https://doi.org/10.1080/002075999399738

Nayak, N.P., Gibbs, R.W., 1990. Conceptual knowledge in the interpretation of idioms. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 119, 315–330. https://doi.org/10.1037/0096-3445.119.3.315

O’brien, I., Segalowitz, N., Collentine, J., Freed, B., 2006. Phonological memory and lexical, narrative, and grammatical skills in second language oral production by adult learners. Appl. Psycholinguist. N. Y. 27, 377–402.

O’Brien, I., Segalowitz, N., Freed, B., Collentine, J., 2007. PHONOLOGICAL MEMORY PREDICTS SECOND LANGUAGE ORAL FLUENCY GAINS IN ADULTS. Stud. Second Lang. Acquis. 29. https://doi.org/10.1017/S027226310707043X

P. Skehan, 1986. ‘Cluster Analysis and the Identification of Learner Types,’ in: Experimental Approaches to Second Language Learning. pp. 81–94.

Papagno, C., Vallar, G., 1995. Verbal Short-term Memory and Vocabulary Learning in Polyglots. Q. J. Exp. Psychol. Sect. A 48, 98–107. https://doi.org/10.1080/14640749508401378

Robinson, P., 2005. Aptitude and Second Language Acquisition. Annu. Rev. Appl. Linguist. Camb. 25, 46–73.

Smith, 1991. Speaking to many minds: on the relevance of different types of language information for the L2 learner [WWW Document]. URL http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/026765839100700204 (accessed 4.11.18).

Sparks, R.L., Patton, J., Ganschow, L., 2012. Profiles of more and less successful L2 learners: A cluster analysis study. Learn. Individ. Differ. 22, 463–472. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2012.03.009

Stansfield, C.W., 1989. Language Aptitude Reconsidered. ERIC Digest.

Stauffer, J.M., Ree, M.J., Carretta, T.R., 1996. Cognitive-Components Tests Are Not Much More than g : An Extension of Kyllonen’s Analyses. J. Gen. Psychol. 123, 193–205. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221309.1996.9921272

Unsworth, N., Engle, R.W., 2007. On the division of short-term and working memory: an examination of simple and complex span and their relation to higher order abilities. Psychol. Bull. 133, 1038–1066. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.133.6.1038

Unsworth, N., Spillers, G.J., 2010. Working memory capacity: Attention control, secondary memory, or both? A direct test of the dual-component model. J. Mem. Lang. 62, 392–406.

Vallar, G., Papagno, C., 1993. Preserved Vocabulary Acquisition in Down’s Syndrome: The Role of Phonological Short-term Memory. Cortex 29, 467–483. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0010-9452(13)80254-7

Williams, J.N., Lovatt, P., 2003. Phonological Memory and Rule Learning. Lang. Learn. 53, 67–121. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9922.00211

Cite This Work

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing stye below:

Related Services

View allRelated Content

All TagsContent relating to: "Psychology"

Psychology is the study of human behaviour and the mind, taking into account external factors, experiences, social influences and other factors. Psychologists set out to understand the mind of humans, exploring how different factors can contribute to behaviour, thoughts, and feelings.

Related Articles

DMCA / Removal Request

If you are the original writer of this dissertation and no longer wish to have your work published on the UKDiss.com website then please: