India and “Indianness” in Salman Rushdie’s Works

Info: 16045 words (64 pages) Dissertation

Published: 10th Dec 2019

Tagged: Literature

‘India-Shindia?’: India and “Indianness” in Salman Rushdie’s

Midnight’s Children (1981) and Amitav Ghosh’s The Shadow Lines (1988)

Introduction………………………………………………………………………………….. 3

Chapter One: The Hybridised India of Midnight’s Children………………………………….. 9

Chapter Two: Indian Identity in the Diaspora……………………………………………………………. 20

Chapter Three: The Mui-Mubarak Relic: The Artifice of Borders and Identity Labels…… 26

Chapter Four: The Nation, Imagined……………………………………………………………………….. 36

Conclusion…………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 41

Bibliography………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 44

Appendices………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. 49

Introduction

In an essay titled “The Riddle of Midnight: India, August 1987”, published in Imaginary Homelands (1991), Salman Rushdie poses the question: ‘Does India exist?’ (2010: 26). He continues by qualifying this question:

After all, there the gigantic place manifestly is, a rough diamond two thousand miles long and more or less as wide, […] populated by around a sixth of the human race […], famous as ‘the world’s biggest democracy’. Does India exist? If it doesn’t, what’s keeping Pakistan and Bangladesh apart?

It’s when you start thinking about the political entity, the nation of India […] that the question starts making sense. After all, in all the thousands of years of Indian history, there never was such a creature as a united India. Nobody ever managed to rule the whole place, not the Mughals, not the British. And then, that midnight [of 15th August 1947, India’s day of independence], the thing that had never existed was suddenly ‘free’. But what on earth was it? On what common ground (if any) did it, does it, stand? (26-27)

Here, as Rushdie later clarifies, it is ‘the idea of the nation’ (32) he is bringing into question. For Rushdie, what sets India apart from other countries is that whilst some are ‘united by a common language, India has around fifteen major languages and numberless minor ones. Nor are its people united by race, religion or culture’ (27). Of course, that is not to say all other countries are united by such factors – far from it – but the extent of India’s multiplicity, as well as its size, makes it an exceptional case.

The question mark, both for Rushdie and this dissertation, hangs above the notion of Indian national identity. The problem is not strictly one of existence, but one of definition and meaning. How does one, or indeed can one, define a nation and its associated identities, specifically one of such multiplicity and diversity as India? This implies a need to explore the concept of national identity, rather than just the nation itself. And of course, this is not exclusive to within India’s borders. There are a vast number of diasporic Indians across the world who consider themselves Indian, in one sense or another, even if their passport says otherwise. Rushdie, now a British citizen, is case in point. As he said in an interview with the Indian magazine, Celebrity: ‘One of the things which interests me is that how the concept of “Indianness” changes when it is exported – like now, there is an Indianness in England, America, Africa. And they are all different kinds of Indianness’ (Reder 2000: 27).

When Rushdie asked the question ‘Does India Exist?’, he did not do so rhetorically. Rather, it was ‘the riddle [he] wanted to try and answer’ (Rushdie 2010: 26) with his hugely successful novel, Midnight’s Children (1981). The novel won him the 1981 Booker Prize, as well as The Best of the Booker Prize twice in 1993 and 2008, and it was listed as one of Le Monde’s Books of the Twentieth Century. This dissertation will explore how Midnight’s Children interrogates the concept of Indian national identity and what it means to be Indian, and it shall do so by means of a comparison with another Indian-set novel from the late Twentieth Century, The Shadow Lines (1988). It is written by Amitav Ghosh, an Indian-born author who now lives in the United States (and has US citizenship) and was awarded the Government of India’s Sahitya Akademi Award for this novel.

Midnight’s Children is epic in scope and references – there are allusions to The Wizard of Oz and multiple Bollywood movies, for example – and stretches in time from 1915 right through to 1977. The novel can be read as an allegory for the birth of the Indian nation, by way of its protagonist, Saleem Sinai, whose autobiography the novel is, given his first-person narrative. Saleem is born at the very moment the nation of India comes into being, the stroke of midnight on 15th August 1947 as ‘clock-hands joined palms in respectful greeting as [he] came’ (Rushdie 2008: 3). As he tells the reader, ‘I had been mysteriously handcuffed to history, my destinies indissolubly chained to those of my country’ (3). Soon after Saleem’s birth, India’s first Prime Minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, writes to him saying that ‘We shall be watching your life with the closest attention; it will be, in a sense, the mirror of our own’ (167), and Saleem acts as just that. Thus, Midnight’s Children is also serves as a discourse on the nation. In effect, Rushdie utilises two layers – the individual and the state – and in doing so, as Josna E. Rege writes, the novel ‘does not deny the nation’s power over individual lives, neither does it subordinate individual to national, but it acknowledges and makes creative capital of both their polarity and their unity’ (2009: 156).

Meanwhile, Ghosh’s The Shadow Lines focusses on two families – one in Calcutta, the other in London – from the outbreak of World War II through to the mid-1980s. The narrator – an unnamed boy – lives through the memories and experiences of those who have gone before him. Like Midnight’s Children, it is a Bildungsroman, where by definition the narrator grows up, and here in doing so is made to reconsider his relationship with the nation he grew up in. But each novel’s protagonist represents a different “India”: Saleem, in Midnight’s Children, is Muslim and thus – as I shall shortly discuss – in a minority, whereas the narrator in The Shadow Lines is a member of the majority Hindu community. Yet the question of national identity is one which both protagonists attempt to answer.

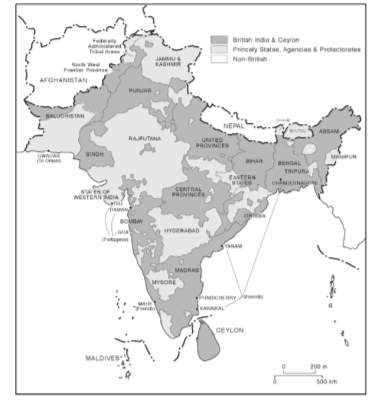

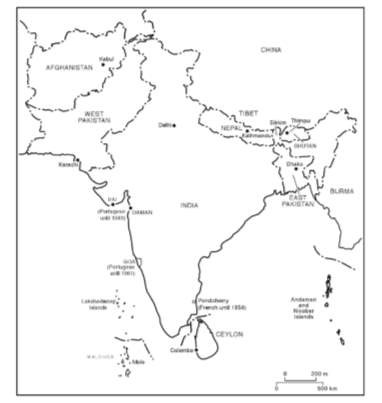

Before I set out how I propose to explore this question, it would be useful to consider some statistics which illustrate the size and multiplicity of India, and the root of Rushdie’s apparent “problem”. The India of now, the Republic of India, is less than a century old; in 1947, British India ceased to exist as the Radcliffe Line – named after its British architect Sir Cyril Radcliffe – partitioned[1] it on a religious basis creating India and Pakistan[2] (see Appendices I and II). India now has the world’s second biggest population with over 1.2 billion inhabitants speaking twenty-two official languages, including English. Hindi is the most commonly spoken of these, used by the Federal Government in Delhi (Chandra 2008: 106), and spoken in a large part of the north of the country, including the state of Uttar Pradesh, the country’s most populous, and the state of Rajasthan, the country’s largest. Yet the Constitution of India does not afford any language the status of national language, and Hindi, certainly as a first language, is rarely spoken in many other, particularly southern, states (see Appendix III). Tamil, for instance, is the official language in Tamil Nadu, with 89.41 percent of the population speaking it (Government of India 2014: 162), whilst 96.74 percent of Kerala’s population speak Malayalam (146). These states have populations similar to that of the United Kingdom; Tamil Nadu’s population, as of the 2001 Census, was in the region of 62 million people (162). It is the sheer numbers involved that make India so seemingly difficult to unify. Tamil Nadu’s population accounts for approximately five-percent of the total national population; even though this is technically a minority, it is nevertheless too considerable a number to be simply classed as such. And though Hindi is the majority language, with 151.7 million speakers in Uttar Pradesh alone (45), one cannot simply label India a Hindi speaking country.

The same can be said about religion. Whilst India is an officially secular nation, its religious make-up is 80.5 percent Hindu, 13.4 percent Muslim, 2.3 percent Christian, 1.9 percent Sikh, 0.8 percent Buddhist, 0.4 percent Jain and 0.7 percent other/not stated (Pinkey 2014: 45). From these crude percentages, it would seem very clear that India is a majority Hindu country and the other religions are minorities. That is indeed the case, but again, the size of the population involved means that these minorities have considerable presence in the Indian population, and therefore one cannot label India a Hindu country. India’s Muslim population is approximately 138 million people, making it the world’s second largest Muslim population after Indonesia’s (Khanam 2013: 2). Furthermore, as John Sargent notes in his book, Society, Schools and Progress in India (2016), ‘these religious groups are neither racially nor linguistically homogeneous’ (xxviii). The problem that stands, therefore, is whether one can define a national identity despite such multiplicity, or whether one needs unifying factors of the kind that Rushdie identifies for a cohesive national identity to exist.

I propose to set out my enquiry into the question of Indian identity and Indianness in Midnight’s Children and The Shadow Lines in the following manner. My opening chapter will begin by outlining the view of India proposed by Rushdie in Midnight’s Children, particularly in the way in which he metaphorises the country to emphasise its hybridised nature. I will then hone in on a specific facet of this hybridity, the British influence. In doing so, I will discuss the way in which India’s colonial past continues to pervade its culture, language and people. The line between the two cultures, as portrayed in the novels, will be seen to have become increasingly blurred. My second chapter will further this idea by examining Ghosh’s representation of India in the diaspora as seen through The Shadow Lines’ character of Ila, the narrator’s cousin, and consequently attempt to show how the notion of a fixed national identity is further complicated when taken beyond the nation’s borders. My third chapter will briefly highlight the syncretic view of India purported by Ghosh through his inclusion of a specific historical event, the Mui-Mubarak Relic theft, before moving on to the chapter’s main focus which is showing how this episode allows him to interrogate the very notion of the nation, particularly the artifice of borders. This will form the basis of my discussion on the arbitrariness of identity labels, particularly in relation to Anglo-Indian identity in Midnight’s Children as highlighted by Loretta Mijares. Then, in my final chapter, I will focus specifically on the different conceptions of “the nation” as purported by both novels, using as my basis Benedict Anderson’s thesis that a nation is an ‘imagined limited community’ (1991: 25). In doing so, I will argue, by drawing on the work of Ranajit Guha, that whilst aspects of Anderson’s view are evident in both novels, his thesis does not hold in relation to India. But that is not to say that the nation does not live in the imagination; as I shall conclude this dissertation, each novel is its own imagining of India.

Chapter One

The Hybridised India of Midnight’s Children

Saleem is the very essence of cultural and genetic hybridity, a term I use here in a basic sense meaning a mixture, or ‘chutnification’ (Rushdie 2008: 642) as Midnight’s Children describes it. Saleem is a polyglot who is the son of a Christian Englishman and an Indian Hindu woman, parented by Kashmiri Muslims with a Goan Catholic ayah, and sent to a Mission school. Saleem embodies a large part of India’s multiplicity, physically so, too, by way of ‘the human geography’ (321) of his face resembling the subcontinent. And therefore, it is no great leap to say that the heart of Rushdie’s representation of the new nation lies in his protagonist. In giving Saleem a background as chaotic as possible, Rushdie is pushing his oft-repeated view that ‘as far as India is concerned, anyway – it is completely fallacious to suppose that there is such a thing as a pure, unalloyed tradition from which to draw. […] The very essence of Indian culture is that we possess a mixed tradition, a mélange of elements as disparate as ancient Mughal and contemporary Coca-Cola American’ (Rushdie 2010: 67), a perfect example of a composite entity with strands so various and entwined that they render the notion of a “pure” Indianness as absurd.

Indeed, Saleem tells the reader that ‘nor am I particularly exceptional in this matter; each “I”, every one of the now-six-hundred-million-plus of us, contains a similar multitude’ (Rushdie 2008: 535). Each one of India’s population has a similarly multitudinous identity, each different from the next, and therefore ‘there are as many versions of India as Indians’ (373), in turn severely undermining the idea of nation-ness based on a pure origin. It is a recurrent theme throughout Rushdie’s works, for example, the half-Jewish half-Christian narrator in The Moor’s Last Sigh (1995) talks of ‘Christians, Portuguese, Jews; Chinese tiles promoting godless views; pushy ladies, skirts-not-saris, Spanish shenanigans, Moorish crowns… can this really be India?’ (2011: 87). For Rushdie and Saleem, India is defined by its extreme and extraordinary diversity. And crucially, each life is intertwined with every other – ‘I am a swallower of lives; and to know me, just the one of me, you’ll have to swallow the lot as well’ (Rushdie 2008: 4), says Saleem – and the eclecticism which is created, whereby traditions mix within each person, as well as the overall cultural make-up of the country, results in persons who can claim that ‘despite my Muslim background, I’m enough of a Bombayite to be well up in Hindu stories’ (206).

Following a certain incident, Saleem develops telepathic powers which enable him to “tune in” to the voices of the nation, the ‘All-India Radio’ (229) as he dubs it. Being a speaker for all of India, Saleem gains access to a nation of consciousnesses, ‘the inner monologues of all the so-called teeming millions, of masses and classes alike’ (232). Saleem exploits this power to go on a whirlwind trip around this new nation. It is a voyage which perfectly encapsulates how India is most commonly viewed from beyond its borders, the India of postcards. I quote at length:

I gained my first glimpse of the Taj Mahal through the eyes of a fat Englishwoman, […] after which […] I hopped down to Madurai’s Meenakshi temple and nestled amongst the woolly, mystical perceptions of a chanting priest. I toured Connaught Place in New Delhi complaining bitterly to my fares about the rising prices of gasoline; in Calcutta I slept rough in a section of drainpipe. […] I zipped down to Cape Comorin and became a fisherwoman […] I flirted with Dravidian beachcombers in a language I couldn’t understand; then up into the Himalayas. […] At the golden fortress of Jaisalmer I sampled the inner life of a woman making mirror worked dresses and at Khajuraho I was an adolescent village boy, deeply embarrassed by the erotic, Tantric carvings on the Chandela temples (239-240).

With its use of verbs such as ‘zipped’, ‘toured’ and ‘hopped’, this passage reads like a tourist’s circuit of India. But further to (though also by way of) some of the clichéd images described, Saleem’s travels highlight the breadth of India’s religious, geographic and socioeconomic diversity. There are contrasting juxtapositions aplenty: priests alongside fat Englishwomen, the wealthy Connaught Place alongside Calcutta’s drainpipes, the extreme altitudinous north of the Himalayas alongside the beaches of the southernmost tip of the Indian peninsula, and the Islamic Taj Mahal – arguably the symbol of India – alongside the Hindu Meenakshi and the Jain Chandela temples. This final pairing is one which is repeated in the peepshow of Lifafa Das; along with their different religions, the Taj Mahal is in the north of the country and the Meenakshi is in the south, accentuating India’s diversity through the geographic polarity of these two landmarks.

But, as Krishna Manavalli’s short study of South Indian representation in Midnight’s Children shows, for a novel whose intention is to give a modern history of India, ‘South India only occupies a liminal space’ (2008: 167). Its references are often asides, ‘on the textual margins’ (167); for example, ‘[Mumtaz’s] skin of a South Indian fisherwoman’ (Rushdie 2008: 69), and mentions of temples and Brahmin priests which result in a ‘stereotypical’ (Manavalli 2008: 168) portrayal. Rather, the novel is considerably more weighted towards the north, especially Delhi and Bombay[3]. Why Rushdie chooses to do this, I would argue, is because these are the metropolitan and cosmopolitan centres of the nation. [4] Bombay is, as Neil Ten Kortenaar writes in his extensive study of Midnight’s Children, ‘a synecdoche of the hybrid nation’ (2004: 147), acting as a microcosm for how Rushdie views the Indian whole. Modern cities are the site of plurality and multiplicity; every one of India’s languages and religions can be witnessed in Bombay, a city where the country’s poorest live adjacent to the country’s – and continent’s – richest. And it was a city built by colonial powers whose cultural influences are still prevalent in India. In The Moor’s Last Sigh, Rushdie describes Bombay as ‘the bastard child of a Portuguese-English wedding, yet the most Indian of Indian cities. In Bombay all Indias met and merged’ (2011: 350).Indeed, in Midnight’s Children, Saleem talks of the ‘highly-spiced nonconformity of Bombay’ (Rushdie 2008: 428). It functions, like India, as a multifaceted whole, ‘a sort of many-headed monster, speaking in the myriad tongues of Babel; they were the very essence of multiplicity’ (317). The country, for Rushdie, is centred around the notion of difference within a heterogenous whole.

I now want to home in on the cultural mélange of India by paying particular attention to the influence Britain has had on the nation and its culture. The move from the colonial to post-colonial period, though divided by a midnight – so symbolic in Midnight’s Children – is not an instantaneous dichotomous change with regards to cultural identity, despite a new nation coming into being. As Harish Trivedi, Professor of English at the University of Delhi, writes in reference to Rushdie’s novel, ‘[India and Britain] are both infected by each other [… and] each ceases to remain what it previously was and becomes “hybrid”’ (2000: 158). By the term “hybrid”, Trivedi is less referring to a mixture of cultures but rather what Homi Bhabha defines ‘a difference “within”’ (1994: 13). To explain this, Bhabha uses the example of a stairwell, a ‘liminal space, in-between the designations of identity, [which] becomes the process of symbolic interaction. […] This interstitial passage between fixed identifications opens up the possibility of a cultural hybridity that entertains difference without an assumed or imposed hierarchy’ (4), because it allows for crossover and movement between two different cultural entities, and thus ‘prevents identities at either end of it from settling into primordial polarities’ (4). Unsurprisingly, British culture and language have worked their way into Indian daily life, and thus, as Richard King notes, ‘the ambivalent figure of the English-speaking Indian in British India […] represents the instability of the coloniser-colonised dichotomy’ (1999: 203).

The rule of the British Crown[5] in the subcontinent lasted close to a century (1858-1947), enough time, then, for at least two generations to live their lives knowing only the Raj. Of course, Britain’s influence in India was not exclusively from the mid-nineteenth century. The British East India Company, an enterprise which began in 1600 with the import of spices and then grew into a gigantic commercial venture, took rule of India in 1757 until it was then subsequently transferred to the British Crown[6] a century later. India thus ‘owed allegiance […] to a whole nation which knew nothing about their history and culture, their aspirations and sentiments; which was at a distance of several thousand miles and could not be approached or influenced by them’ (Husain 1978: 122). This heightened the political importance of the British, in turn shaking Indians’ faith in their own culture. It was therefore, as Husain ironically puts it, Britain’s ‘sacred duty to uplift a depressed people through Western education and culture’ (120), standing on a presumption that ‘humanity is not one’ (Garg 2008: 170). This is predicated on a binary, that of East and West, perpetuating, as Edward Said writes in Orientalism (1979), an ‘ontological and epistemological distinction […] between “the Orient” and […] “the Occident.”’ (2), whereby ‘European identity [is the] superior one in comparison with all the non-European peoples and cultures’ (7). Even Indians who were “European” in character and education were nevertheless deemed to be inferior, and had to be differentiated as such. In his article “Can the “Subaltern” Ride?” (1992), Gyan Prakash talks of how the British utilised the Western-educated Indian’s inability to ride horses to exclude them from the civil service: ‘by pointing to a lack in the Indian, the polarity between the native and the Englishman was preserved, thus containing the threat that the equivocal figure of the English-speaking Indian posed to the binary structure of coloniser and the colonised’ (169). But it was also Britain’s view that Indians needed to be catapulted into the modern age, and for it to do so, ‘India had to assimilate something of the modern Western culture which had helped its rulers to reach their present prosperity and power’ (Doshi 2008: 233).[7]

However, what constituted this “modern Western culture”? Husain writes that ‘the modern Western culture that reached India was not the genuine article but an export model of which the parts came from England but were assembled in India mainly by men of mediocre ability’ (1978: 122). This export model largely consisted of the superficial, such as food, dress and environs, that which can be observed easily. And in many respects, it is this hollow façade of what it means to be “British” that is in evidence in Midnight’s Children. In the novel, prior to his return to Britain, the Englishman William Methwold – a fictional descendant of the real William Methwold, one of the original colonial occupiers of India –divides his Bombay estate between four Indian families on one condition: that ‘the entire contents [of the houses] be retained by the new owners’ (Rushdie 2008: 126) [8]. And therefore, the new inhabitants begin living amongst ‘a pianola’ (130) and ‘pictures of old Englishwomen everywhere’ (127). The Estate’s four houses are each named after one of Europe’s great palaces: ‘Versailles Villa, Buckingham Villa, Escorital [sic] Villa and Sans Souci’ (125). Located off ‘Warden Road between a bus stop and a little row of shops […], arranged nobly around a little roundabout’ (124-125), one gets the impression the estate is, as Kortenaar amusingly calls it, ‘a kind of Brideshead in Bombay’ (2004: 188). And indeed, that is what the British attempted to create, hence ‘Breach Candy Swimming Club, where pink people could swim in a pool the shape of British India without the fear of rubbing up against a black skin’ (124). Whilst the colonial rulers occasionally appear to assimilate to “Indian” culture – Methwold’s speech is studded with Indian phrases, such as ‘Sabkuch ticktock hai, everything’s just fine’ (128), being one example from the novel – the Swimming Club is proof enough that that assimilation was purely token. They wanted their lives to be very much separate. Instead, ‘the coercive weight of assimilation ultimately falls rather more on the colonised’ (Trivedi, 2000: 158). Despite their early grievances – ‘For two months we must live like those Britishers?’ (127), complains Ahmed Sinai – the new Indian inhabitants of the Estate adopt English cultural traits. As Kortenaar notes, ‘living amongst other people’s things transform the current residents into not-so-pale imitations of those they have supplanted’ (2004: 168). Ahmed Sinai’s voice changes into ‘an apeing Oxford drawl’ (Rushdie 2008: 147), and similarly, it is worth noting that in The Shadow Lines, the narrator’s aunt, ‘clutching her teacup like a sceptre’ (Ghosh 2001: 208), so resembles the British Monarch that it ‘earned her the nickname of Queen Victoria’ (31), by which she is referred to throughout the novel.

What is being demonstrated, by way of the examples I have cited, is cultural mimicry, a discourse described by Bhabha as ‘the desire for a reformed, recognizable Other, as a subject of difference that is almost the same, but not quite’ (1994: 86, author’s italics). Over the course of a prolonged period of colonial rule, the colonised develop a tendency to mimic their colonisers. Indeed, that is what was intended, as the British Politician Lord Macaulay’s “Minute on Indian Education” (1836) shows us.[9] In this regard, Macaulay is not anticipating a hybridised culture, but rather a complete replacement. His view is that the superiority of Western knowledge will replace their ‘monstrous superstitions […], false history, false astronomy, false medicine and a false religion’ (Young 1952: 728). But this does not happen in Midnight’s Children. The novel tells us that ‘the sharp edges of things are getting blurred, so [the Indians] have all failed to see what is happening: Methwold’s Estate, is changing them’ (Rushdie 2008: 131). Whilst it is changing them, it is not reinventing them completely as Macaulay would have it. Bhabha states that there is an essential distance between the mimicry and the “authentic” product: ‘in order for it to be effective, mimicry must continually produce its slippage, its excess, its difference’ (1994: 122). There is an irony here, for in their aspiration to Englishness, the “slippage, excess and difference” of the mimicry in itself serves to highlight the distance between the two: ‘when they speak like Englishmen, these Indians will prove they are not Englishmen but parrots’ (Kortenaar 2004: 169).

This mimicry does not end with colonial rule. Take the artwork hanging on the wall of Saleem’s bedroom, a leftover relic from the Methwold-era. It is a print of a painting whose name we are not told, though Rushdie’s description is detailed enough for one to conclude that it is, or certainly has a strong resemblance to, Sir John Everett Millais’ The Boyhood of Raleigh (1870, see Appendix IV). Rushdie writes of ‘the young Raleigh sat, framed in teak, at the feet of an old, gnarled, net-mending sailor [and] another boy […] sitting cross-legged in frilly collar and button-down tunic’ (Rushdie 2008: 166). And Saleem, a young baby at this point in the novel, is dressed in ‘just such a collar, just such a tunic (166), a baby English Milord; as the character Lila Sabarmati exclaims, ‘It’s like he’s just stepped out of the picture!’ (167, author’s italics). But of course, Saleem is only dressed like the boy in the picture; the similarity is one of aesthetics, nothing more. It is a resemblance, not a replication, and it is this difference which Bhabha argues counters the possible threat to the desired binary opposition between the colonised and the coloniser.

As one can see, there is a ‘continued post-colonial Anglicization’ (Trivedi 2000: 158) which is visible not only in the nation’s population but also its material fabric. For example, Connaught Place, in the commercial heart of Delhi, is enclosed by a ring of white colonial buildings with their columns, arches and louvered windows. The Place’s official name is in fact not Connaught but Rajiv Chowk, yet it is seldom called by the Hindi; the British mark remains and persists, both on the landscape and, as we have already seen, the people. Describing Delhi, Saleem tells the reader: ‘You could not see the new city from the old one. In the new city, a race of pink conquerors had built palaces in pink stone, but the houses in the narrow lanes of the old city leaned over, jostled, shuffled, blocked each other’s view of the roseate edifices of power’ (Rushdie 2008: 88). Notice the language used: the “pink conquerors” are mirrored in their “pink palaces”, the buildings embodying their British creators, the hierarchy of power reflected in the fabric of the city. Furthermore, and even more telling, is the obsequious image of India presented in the “narrow lanes leaning over, jostling and shuffling”. The “old city”, the colonised, is vying for space whilst bowing down to the “edifices of power” of the new city of the colonisers. Furthermore, Saleem tells the reader how his father, Ahmed Sinai, ‘becomes entirely white except for the darkness in his eyes’ (247), just as ‘the businessmen of India were [all] turning white’ (248) because of efforts needed to take over from British rule. It is ironic that to take back control of their nation, the Indian people – the once colonised – must not only mimic their ex-colonisers, but they must, quite literally, transform into them too.

However, the biggest legacy of the empire with regards to Midnight’s Children and The Shadow Lines is language. English acts as a pan-India bridge, used for commerce and for communication between different language-groups in the country; as a character says in The Moor’s Last Sigh, ‘all these different lingos cuttofy [sic] us off from one another. […] Only English brings us together’ (Rushdie 2011: 179). But here the “us” is only four-percent of the Indian population (McArthur 2005: 290)[10]; and thus, it is not, as the previous chapter hinted, enough to unify the population. Rather, it is very much India’s elite – predominantly Western educated – who can speak it. And that includes both Ghosh and Rushdie, who utilise the language of the coloniser in their writings of the nation. However, this in turn furthers the hybridised view of India which the novels seek to portray, for both punctuate the English language with words in Hindi and Bengali; ‘mugger-much’ (Ghosh 2001: 27), ‘ayah’ (28) and ‘shikara’ (Rushdie 2008: 11), for example. Indeed, Rushdie writes in Imaginary Homelands that ‘we [Indians] can’t simply use the language the way the British did. It needs remaking for our own purposes. […] To conquer English may be to complete the process of making ourselves free’ (2010: 17). The English language is forced to accommodate the words and lexical structures of Indian languages. English words appended with the honorific suffix “-ji” – ‘sisterji’ (Rushdie 2008: 99) and ‘cousinji’ (88) – is just one form of the hybridization of language on show. Ghosh frequently juxtaposes an English word alongside a native word, such as ‘hot shingaras’ (2001: 5) and ‘street corner addas’ (10). And further to this, it can be argued that the English language is also forced to accommodate the topography of the subcontinent, with paragraph after paragraph throughout both novels featuring place names: Agra, Srinagar and Calcutta, to give just three. Also, words one might consider to be English, including ‘pajama’ (Rushdie 2008: 28) and ‘jungle’ (513), are in fact both Hindi and have been “adopted” by the English language. In this regard, the line blurs in both directions. However, as noted above, the use of English, as well as British education and so on, are only representative of a very thin segment of the population, who, as the next chapter will show, are in the position of being able to travel (and live) beyond India’s borders, which in turn further problematises the notion of what it means to be Indian.

Chapter Two

Indian Identity in the Diaspora

India’s diasporic population is the world’s largest, with a total of sixteen million Indians living outside the country of their birth (Sims 2016). Of course, this does not include all those of Indian origin – who also view themselves as Indian – who were born outside India (and possibly never set foot in the country). But as Sandhya Shukla argues in her probing analysis of India’s diasporas, India Abroad (2003), ‘in each site of the diaspora, “being Indian” has acquired a particular set of meanings’ (19). And these sites are wide-ranging, from South Africa to Malaysia to the United Kingdom. In this chapter, I will look at the experience of Ila in The Shadow Lines as an Indian abroad in the UK, exploring how her diasporic nature brings her fragmented national identity to the fore.

Of all the characters across both novels, Ila – the narrator’s cousin and object of desire in The Shadow Lines – assimilates most to Western culture. Not only does she embrace British ways by dressing in Western clothes – the narrator views her as ‘improbably exotic […], dressed in faded blue jeans and a T-shirt’ (Ghosh 2001: 99) – but she moves to the UK and as such she becomes a diasporic Indian. She does so out of choice, not compulsion. Ila cannot identify with India, in part because she has never really lived there – she spent a large part of her childhood in ‘a worldwide string of departure lounges’ (25), because of her diplomat father – and finds difficulty in identifying with its culture for it is too restrictive and conservative. She cries out to her (Indian) uncle, Robi: ‘Do you see now why I’ve chosen to live in London? […] It’s only because I want to be free […]. Free of your bloody culture’ (109). Ila is turning her back not only on Indian customs but on India itself, ‘seek[ing to] escape from India and its social world by participating in the fantasy that the colonisers promoted: that England is a superior nation with a superior national culture’ (Shukla 2003: 153). In Imaginary Homelands, Rushdie writes that:

I can’t escape the view that my relatively easy ride is not the result of the dream-England’s famous sense of tolerance and fair play, but of my social class, my freak fair skin and my “English” English accent. Take away any of these, and the story would have been very different. Because of course the dream-England is no more than a dream (2010: 18).

And Ila indeed strengthens this view of England as a “fantasy” and “dream”, but her experience – because of the lack of the factors Rushdie lists – is very different.

Her cry of freedom comes on the back of an incident in a Calcutta nightclub, where seeing her flirt with two businessmen, Robi ‘wrenched her away’ (Ghosh 2001: 108) and hits one of them. Justifying his actions, Robi tells Ila that ‘girls don’t behave like that here’ (109), if anything affirming her view of India as backward. Shubha Tiwari, in her critical study of Ghosh, describes Ila as wanting to ‘live life on the edge, […] dangerously, doing things unconventionally’ (2003: 37) – unconventionally being culturally relative, of course. Her grandmother, Tha’mma, holds similar views to Robi; she deems Ila’s looks and clothes as inappropriate to her Bengali middleclass origins. Tha’mma criticises ‘her hair cut short, like the bristles on a toothbrush, wearing tight trousers like a Free School Street whore’ (Ghosh 2001: 99). There is a contention between cultures; Ghosh portrays India as conservative when compared to the UK, upholding ‘certain principles and imbibed value systems, like sanctity of man-woman relations after marriage’ (Dodiya 2006: 255), which are not evident in his portrayal of London.

Though Ila is not Anglo-Indian in the strict sense of the term I shall discuss in the next chapter (neither of her parents are British, for example), she is caught –much more than Saleem, in part because Saleem never journeys beyond the subcontinent –in a limbo between her Indian identity and a British identity to which she is trying to assimilate. It is worth turning to a 1946 poem by C.M. Binti Hassani, published in the Mambo Leo newspaper of British‐Tanganyika, which neatly illustrates the state in which Ila finds herself. In the poem, Hassani writes of an East African-Indian: ‘If he arrives in Africa, we say he is Indian, / If he goes to India, he is reviled as an African, / […] What tribe should we call him?’ (cited in Burton 2013: 2). The “he” in the poem exists in a state of flux whereby he, like Ila, is an outsider in two communities. Ila is neither fully Indian or British, and in each country, she is viewed as the other. In effect, one could rewrite Hassani’s poem for Ila: “If she arrives in Britain, we say she is Indian, / If she goes to India, she is deemed British, / […] What should we call her?”. Of course, both Ghosh and Rushdie are of the diaspora. The former, writing about his position as an ‘exile or emigrant or expatriate’ (Rushdie 2010: 10), talks of being in a position very similar to that of Hassani’s poem: ‘our identity is at once plural and partial. Sometimes we feel that we straddle two cultures; at other times, that we fall between two stools’ (15). Indeed, in Midnight’s Children when Adaam Aziz, Saleem’s grandfather, returns from Germany after five years of studying there, he does so with ‘an altered vision’ (Rushdie 2008: 5). His relationship with India, his country, has been destabilised; ‘the old place resented his educated, stethoscoped return’ (5). There is an in-betweenness that in turn, as we have seen, is mirrored in Saleem and Ila. And in turn, their contributions to the national whole – for each one is an “Indian” – again challenge the idea of a homogenous and distinctly separate Indian identity.

Ila is a woman who is constantly away from “home” because she has no real home. She does not identify with her Indian roots and thus rejects India; in referring to the narrator as a ‘third-world tapioca farmer’ (Ghosh 2001: 26), she locates herself as external to, or even above, its culture. Indeed, as a child she has a doll, Magda, who in one respect acts as her alter-ego, and is everything Ila wants to be. She is described with a distinct hint of envy: she has ‘bright, golden light [hair…], deep blue eyes, […] cheeks pink and healthy’ (90), Caucasian English in appearance. Yet Ila is in many ways rejected by Britain, the culture she wants to identify with. Whilst her financial situation and her mobility mean that she is in the upper echelons of Indian society, her race places her in a lower class in England. Peter van de Veer writes that ‘those who do not think of themselves as Indians before migration become Indians in the diaspora’ (1995: 7). Ila definitely does not think of herself as homogenously Indian. In Britain, however, it is unfortunately her difference which defines her. Although London is a multicultural city – though one must remember this is 1960s to 1980s London – she is nevertheless deemed to be an outsider, both in adulthood and childhood, because of her ethnicity. Nick Price, her school friend (later to be her adulterous husband), does not want to be seen ‘walking home with an Indian’ (Ghosh 2001: 94 my italics). Furthermore, she is subject to abuse because she is Indian, being called a ‘little wog, […] filthy little nig-nog’ (92). She is othered, even unintentionally; her teacher, commenting on a peer’s poor grammar, says ‘perhaps you ought to take English lessons from her [meaning Ila], even though it’s your own language, not hers’ (91, author’s italics). There is an implication from this that Ila does not belong in England, even though she speaks the language better than the “natives”. Here, her Indian identity is defined primarily by race. Ila is treated as a ‘despised Asian’ (Joshi 2008: 125) and not allowed to assimilate, no matter how hard she tries – her linguistic ability, for example, is clearly more than sufficient.

To further van de Veer’s point, Ila seeks out “Indian” culture when in London for want of not being the outsider. I use inverted commas as India’s individual cultures and cuisines are viewed very generally when amongst the fabric of a distinctly different setting such as London. For example, Ila treats the narrator and Robi to her ‘favourite “Indian” restaurant– a small Bangladeshi place called the Maharaja, in Clapham’ (Ghosh 2001: 294). Similarly, she attempts to speak Bengali when enquiring at the Taj Travel Agency; if anything, London helps to bring her Indian identity more into focus. As Jaydipsinh Dodiya explains, ‘the freedom and identity she wanted in the western world […] required a sacrifice of certain principles and imbibed value systems’ (2006: 255), like, as mentioned, the sanctity of marriage. The fact that she struggles to alter her perspective in this respect, Dodiya argues, foregrounds the Indianness in her.

However, as I have shown, other aspects of her identity appear to be at odds with this. But does this make her any less “authentically” Indian? Whilst – bloodline aside –Ila does not see herself as Indian when in India (and neither, to a degree, do the narrator or Tha’mma view her as such), in Britain, Nick and Ila’s classmates, amongst others, do. A foreigner’s concept of a certain national identity is very different to that of someone of that national identity, for it is likely to be homogenised when viewed in light of another culture. Indeed, the “Indian” restaurant shows this; it is called “Indian”, but it is not run by Indians and the food served is ‘something exotic –like Eskimo food’ (Ghosh 2001: 295). India, here, exists as a label which seems to be independent of her borders, and likewise, as I showed using Hassani’s poem, Ila is defined by her difference to the dominant culture in which she finds herself. Rajagopalan Radhakrishnan writes in his excellent essay, “Is The Ethnic “Authentic” In The Diaspora?” (2001), that ‘we can know places that are distant as much as we can misunderstand and misrepresent places we inhabit’ (206). Though Ila both lives abroad and is not, in older generations’ eyes, “Indian”, Radhakrishnan suggests that this does not render her view and version of India any less authentic. She is, after all, Indian in one sense or another. The ‘bloody culture’ (Ghosh 2001: 109) she speaks of is that prescribed by the older generations of Tha’mma and her uncle, and living abroad allows her to ‘experience another culture […] as a reprieve from the orthodoxies of [her] own “given” culture’ (Radhakrishnan 201: 207) and in turn view her “given” culture in a new light, further complicating the notion of a fixed national identity.

Chapter Three

The Mui-Mubarak Relic: The Artifice of Borders and Identity Labels

In my first chapter, I discussed how Rushdie metaphorises India into something else and in doing so pointedly shows its multiplicity. In The Shadow Lines, Ghosh resists metaphors and allegories, but is nevertheless in agreement with Rushdie. As Ghosh writes in his essay “The Diaspora in Indian Culture” (1989), ‘India has failed to develop a national culture. It is not a lack; it is in itself the form of Indian culture. If there is any one pattern in Indian culture in the broadest sense it is simply this: that the culture seems to be constructed around the proliferation of differences’ (78). With The Shadow Lines, Ghosh proposes such a view with the novel’s recounting of a particular historical episode: the 1963 theft of the Mui-Mubarak relic – a strand of hair believed to be from the Prophet Muhammad’s beard –from the Hazratbal Shrine in Srinagar, Kashmir. Following the discovery that the relic was missing, demonstrations of both protest and sorrow took place ‘in which Muslims, Sikhs and Hindus alike took part’ (Ghosh 2001: 276) in an unleashing of religious emotion. Ghosh uses this incident to highlight the syncretic nature – and virtues thereof – of the Indian state:

In the whole of the valley there was not one single recorded incident of animosity between Kashmiri Muslims, Hindus and Sikhs. There is a note of surprise – so thin is our belief in the power of syncretic civilisations – in the newspaper reports which tell us that the theft of the relic had brought together the people of Kashmir as never before (277).

Ghosh’s retelling appears to be grounded in fact; the Hindustan Times of the day notes that ‘Srinagar [upon recovery of the relic] never before witnessed such joyous crowds, which included Muslims, Hindus, Sikhs and others. Women threw off their veils and men tossed their caps and turbans. […] Muslims made for mosques and Hindus blew conches’ (Anonymous 1964). But whilst Ghosh uses this episode to celebrate India’s syncretism, it is also testament to what his narrator terms as the ‘looking-glass borders’ (2001: 286) of the subcontinent. It is to this I now wish to turn, for it is the main focus of this chapter, which will attempt to show how The Shadow Lines interrogates the very notion of “the nation” and the identity that goes with that.

The Shadow Lines shows how the Mui-Mubarak episode extended beyond India’s borders. Though peaceful celebration took over Kashmir, the city of Khulna in East Pakistan – approximately 1500 miles away – experienced violent protest, subsequently causing other protests in nearby towns and Dhaka[11]. And then these protests ignited other protests back across the border in Calcutta[12]. The people of East Pakistan, though partition was twenty years previous, still maintained a strong enough connection with events in Kashmir to cause protest and death. Ghosh, here, is arguing that whilst a line now exists to separate the two, ‘there had never been a moment in the 4000-year-old history of that map when the places we know as Dhaka and Calcutta were more closely bound to each other than after they had drawn their lines’ (286, my italics). The narrator says that ‘I, in Calcutta, had only to look in the mirror to be in Dhaka; a moment where each city was the inverted image of the other’ (286). This, for Ghosh, is the aforementioned ‘looking-glass border’ (286), whereby a focus on boundaries and divisions creates false distances, hence the narrator’s belief that Calcutta and Dhaka are mirror images of one another, ‘locked into an irreversible symmetry’ (286).

The relic theft demonstrates thatthe effects of both religious and national identity spill over imposed constraints imposed that endeavor to cordon off a space as their own. Following the theft, the narrator uses his atlas and a compass to draw out ‘an amazing circle’ (284) whose radius is the distance between Khulna and Srinagar (see Appendix V). This circle went from Sri Lanka to halfway across China, and showed that:

within the tidy orderings of Euclidean space, Chiang Mai in Thailand was much nearer Calcutta than Delhi is […] yet I had never heard of [it]. It showed me that Hanoi and Chungking are nearer Khulna than Srinagar, and yet did the people of Khulna care at all about the fate of the mosques in Vietnam and South China (a mere stone’s throw away)? I doubted it (284-285).

Nothing happened in these adjacent Chinese and South East Asian cities because of the theft in Srinagar, yet they are considerably closer to the site than Khulna is. The narrator is arguing, therefore, that this circle throws into question our notion of distance; geographical distances have been mediated by lines of nationhood, shadow lines, within each enclosure is a ‘monopoly of all relationships between peoples’ (283).

The artifice of borders is arguably the most prominent theme of Ghosh’s novel, and it is on this I now want to focus. Needless to say, a quick glance at a world map shows that each individual country is marked out by lines which distinguish it from other countries. Some, like Australia, have their borders defined by sea, yet not all islands – like Ireland – are home to solely one nation. And again, not all island countries are limited to just one island; Japan, for example, spreads across thousands. India too, as my introduction noted, has a line which encircles it, distinguishing it in part from the sea and in part from the seven other countries it borders. In fact, S. Abid Husain, in his book The National Culture of India (1978), notes that India has a geographical unity ‘which very few national states can boast of’ (xxvii) with its ‘impassable mountains in the north, open sea of the south, south-east and south-west, form[ing] the most sharply defined natural boundaries one could imagine’ (xxvii). Post-partition, however, the northern borders are considerably more artificial [13].

Central to the idea of borders is the notion of difference, and it is this which borderlines both construct and consolidate. In one sense, borders are interactive, for they are where nations meet and negotiate. But foremostly, they signify limits and indicate distinctiveness and separation. Sharmani Patricia Gabriel, in her article “The Heteroglossia of Home” (2005), writes that:

implicit in the conception of the border, i.e. its function of separating entities, is the notion of binary oppositions. Within this logic of binary separation, the framework of which still largely governs the construction of cultural and spatial boundaries […], differences [which] are often conceptualised in terms of clear-cut distinctions (42).

These distinctions rely on ‘Blut und Boden’ (van de Veer 1995: 6, author’s italics), the blood and soil – in other words, territory – where populations are rooted to land, and therefore ‘outsiders do not belong, [because they] are not rooted in the soil’ (6). Gabriel proceeds by citing the semiotician Yuri Lotman, who argues that all cultural systems ‘begin by dividing the world into “its own” internal space and “their” external space’ (cited in Gabriel 2006: 42). ‘An important consequence of this division of the world into cultural spaces marked as “us” and “them”, “inside” and “outside” is the underlying principle that the narrative of the “self” is consolidated through an absolute opposition with its “other”’ (42). This sounds remarkably like what Said argues in Orientalism,but Gabriel here is not restricting this to an East/West, coloniser/colonised dichotomy. Rather, she (and Lotman) are arguing that this binary division extends to all countries; ‘to call yourself Australian or Chilean or Sri Lankan is to draw a psychological as well as a physical boundary around yourself and those who claim the same national identity’ (Brooks and Nicéphore 2014: 128). It is not solely down to power relations; rather if “we” are inside a boundary, “they” are outside it. As one character in The Shadow Lines believes, ‘across the border there existed another reality’ (Ghosh 2001: 268).

However, what Gabriel et al. are stating is at odds with the ‘looking-glass border’ (Ghosh 2001: 286) dividing India and East Pakistan. This would suggest that both sides – Dhaka and Calcutta –are the same, and therefore what is the other side of the border from the Self’s position (Calcutta or Dhaka, it does not matter the viewpoint) is not the “Other” but also the Self. This, in part, is what Ghosh talks of when he says, ‘what interested me first about borders was their arbitrariness, their constructedness – the ways in which they are “naturalised” by modern political mythmaking’ (cited in Roy 2010: 113). Borders are, as the title of Ghosh’s novel tells us, shadow lines.

Before a flight between Calcutta and Dhaka, Tha’mma asks if ‘she would be able to see the border between India and East Pakistan from the plane’ (Ghosh 2001: 185). On learning that she would not, she exclaims, ‘if there aren’t any trenches or anything, how are people to know? I mean, where’s the difference then?’ (186). She is both surprised and concerned at the lack of border between the two countries. The act of partition, and all the violence and deaths that came with it, is deemed worthless if there is no visible mark of difference. And therefore, as a result, it is not only the borderlines which Ghosh portrays as arbitrary, but the citizenship that goes with it. Tha’mma is flying to Dhaka to bring her uncle, Jethamoshaim, back to India to live with her. Both were born in Dhaka, but unlike Tha’mma, he stayed in now East Pakistan. Though Tha’mma is returning to her birthplace, she is now Indian; completing her landing card, she is ‘not able to understand how her place of birth had come to be so messily at odds with her nationality’ (Ghosh 2001: 187). Furthermore, she now requires a visa, in one respect making her more of a foreigner in East Pakistan than May, sister of Nick Price, whose British passport grants her visa-free travel. She concedes to this fact: ‘Yes, I am really a foreigner here – as foreign as May in India or Tagore in Argentina’ (240). Yet Jethamoshai holds a different view, and refuses to leave: ‘I don’t believe in this India-Shindia. […] As for me, I was born here, and I’ll die here.’ (264). He is no longer an Indian in India, a Hindu in a majority Muslim country (Pakistan, after all, was founded on a religious basis), and Tha’mma wants to restore him to the nation to which he is supposed to belong. But East Pakistan is his home; not East Pakistan per se, but the land and the city. The borders have shifted relative to him. Though he is Indian (in the pre-partition sense of the word), he does not recognise himself in the newly born falsity that is “India-Shindia”, as he terms it. He is an advocate for inclusion and communal harmony, questioning the boundary creating ideology of nationalism, and instead – much like the syncretic India which Saleem/Rushdie describes – befriending local Muslims and even offering them places to stay in his large house. It is a similar viewpoint to that of the narrator’s, one which I shall return to and analyse in more detail in the next chapter, that there is an ‘indivisible sanity that binds people to each other independently of their governments’ (283).

I want to further this idea of the arbitrariness and artificiality of citizenships and identity by focussing specifically on Saleem, an Anglo-Indian hybrid child of colonialism, who – like Rushdie, Ghosh and Ghosh’s protagonist – receives a British education and personifies a new cultural mixture in India. Despite India’s new found independence, British and Indian identities, as my first chapter showed, cannot be viewed as mutually exclusive. The term “Anglo-Indian”, quite obviously I would argue, suggests a mixture of British and Indian cultural background, if not blood[14]. But it in fact has a far more precise, if complicated, definition which is worth detailing because it presents several difficulties. In the 1935 Government of India Act, as well as in ensuing Constitutions of India, it states:

An Anglo-Indian means a person whose father or any of whose other male progenitors in the male line is or was of European descent but who is domiciled within the territory of India and is or was born within such territory of parents habitually resident therein and not established there for temporary purposes only. (cited in Gist and Wright 1973: 2)

This definition is bizarrely inconsistent. It is based solely on patriarchal lineage, so a child born to an Indian father and British mother would be considered Indian, not Anglo-Indian. Besides, if both the father and mother of a child are British but “domiciled within the territory of India”, that child would still be conserved Anglo-Indian despite there being no “Indian” within them. Also, note the absence of the term British; only “European descent” is stated, and so one can, in theory, be Anglo-Indian without being either Anglo or Indian. Of this, Loretta Mijares notes that ‘categories such as “Anglo-Indian” and “Domiciled Europeans” are elusive, specifiable only within a given historical and geographic location’ (2003: 126). Furthermore, the term “Anglo-Indian” was used in different ways in different parts of India; some referring to Eurasians, some Europeans, some specifically British-Indian (see 141-142). This lack of coherency highlights the ambiguous and arbitrary nature of labelling identity.

Rushdie’s protagonist further complicates matters, for Saleem is an a-typical Anglo-Indian. He is brought up in a well-off Muslim – though secular – family in Bombay, and crucially he is unaware of his racial makeup, as are most of those around him. He does not look any different, and thus is presumed to be fully “Indian”. Yet when it is discovered that he has British blood, and his parents are not his biological parents because of a switch of babies at his birth, others’ perceptions of his identity do not change noticeably[15]. Midway through the novel, Saleem declares to Padma, his lover, ‘I am Anglo-Indian’ (Rushdie 2008: 158); his real father is not Wee Willie Winkie, an Indian, but Methwold, with whom Vanita had an affair; a potential metaphor for Britain being in India illegitimately. Saleem’s revelation is met with initial shock on the part of Padma: ‘An Anglo?… What are you telling me? You are an Anglo-Indian?’ (158), but it transpires that this reaction is primarily because of shock and Saleem’s apparent deception. As Saleem proceeds to tell Padma, ‘When we eventually discovered the crime of Mary Pereira [the nurse responsible for the baby swap], we all found it made no difference! I was still their son: they remained my parents’ (158, author’s italics). Furthermore, the fact that Saleem and Shiva –Saleem’s archrival who was born at precisely the same moment as him –were switched at birth highlights not only that one’s bloodline is not central to one’s identity, as we have just been told, but also the artificiality of identity by way of class, religion and race. Saleem’s race was assumed by all to be “purely” Indian, but this revelation ruptures these assumptions. Whereas Saleem is raised with privileges in a well-off Muslim household, a life that should have been Shiva’s, Shiva is instead raised a Hindu in abject poverty by a single father. This furthers the view that identity is a ‘socially constructed fiction’ (Mijares 2003: 132). But it is a fiction which nevertheless determines one’s life and the possibilities available therein; the irony of the ditty Mary Pereira sings to Saleem – ‘anything you want to be, you kin be, you kin be just what-all you want’ (Rushdie 2008: 534) – is therefore paramount.

As a label, the term Anglo-Indian is inconsistent and arbitrary, and a similar view can be afforded to citizenship. To show this, I wish to turn briefly to the philosopher and literary critic, Helène Cixous. Cixous was born in Algeria to Spanish and Central European Jewish parents, was brought up in a multilingual household and has French citizenship. Yet, as she remarks: ‘to be French, and not a single French person on the genealogical tree, admittedly it is a fine miracle’ (1998: 127). She has a label, but that label is not reflective of her identity. One’s citizenship is just one form of labelling; ‘it does not define a cultural, linguistic, or, in general, historical participation’ (Roberts 2011: 212). But at the same time, citizenship is not superficial; it provides opportunities, for as Saleem says in Midnight’s Children, ‘without passport or permit, I [am…] cloaked in invisibility’ (Rushdie 2008: 532). There is a tangible link between citizenship and territory – a French passport is intrinsically linked to the land one calls France, for example – but whilst maps appear to delineate permanent boundaries, these are in fact often contested, ambiguous and shifting. And this is evidenced in Saleem who speaks of Pakistan as ‘not “my” country, although I stayed in it – as refugee, not citizen; entered on my mother’s Indian passport’ (405). But the land was his country’s, prior to partition; Pakistan was India but is India no longer. Saleem was Indian but as he later tells the reader, ‘I became a citizen of Pakistan’ (488); his identity has, in one respect, changed, something he recognises when he speaks of ‘my Indian childhood and Pakistani adolescence’ (453).

By contrast, Tha’mma moved to India pre-partition, not because of it. In one respect, both are now in their respective places as the British would see it: Muslim Saleem in Pakistan, and Hindu Tha’mma in India. But it is not so clear cut, for Tha’mma’s home is still Dhaka. Before heading back there to see Jethamoshai, she fears ‘it won’t be like home anymore’ (Ghosh 2001: 183). The notion of home is explored by Ghosh through language, and the differing meanings of “coming” and “going”. Tha’mma talks of ‘com[ing] home to Dhaka’ (187) when, as the narrator points out, it should be “going”: one goes on a trip, one comes home at the end of it. In effect, committing to this phrasing – “going to Dhaka” – implies an up-rootedness. Tha’mma is a victim of the subcontinent’s history and has, in a sense, lost what Edward Said calls ‘their roots, their land, their past’ (2000: 42). And thus, home becomes ‘the traumatic site of cultural reconstruction’ (Gabriel 1999: 243), involving a conflict between many assumptions, including the prevailing idea that “home” always exists, because ‘every language assumes a centrality, a fixed and settled point to go away from and come back to’ (Ghosh 2001: 188). On arrival in Dhaka, Tha’mma asks ‘where’s Dhaka?’ (238). Whilst the city of 14million people blatantly exists, Tha’mma’s question is, as Rupali Sircar notes, ‘recognition that a city where one has lived out their growing-up days is a “person” and not just a place. [There is] a relationship forged’ (2008: 113). In this sense, Dhaka, the Dhaka that is her home, lives in her imagination; as the narrator says, she has ‘no home but in the memory’ (238). Tha’mma is forced to accept that national borders alone are not sufficient in defining what is home, but rather, ‘the meaning of home is dependent on specific historical and social contexts’ (Gabriel 2006: 49), and as such exists in the mind as much as – if not more than – it does physically.

Chapter Four

The Nation, Imagined

In this final chapter, I wish to expand upon the idea of one’s home and nation existing in the imagination. For Ghosh’s narrator, a nation is much more than a piece of land surrounded by a border within which is a “people” to whom that nation belongs. It is also a mental construct, which in turn suggests Benedict Anderson’s thesis that a nation is an ‘imagined community’ (1991: 25). For Anderson, it is not imagined in the sense that it is fictitious, but rather ‘it is imagined because the members of even the smallest nation will never know most of their fellow-members, meet them, or even hear of them, yet in the minds of each lives the image of their communion’ (6). Partha Chatterjee, in his summary of Anderson’s thesis, writes that ‘nations are not the determinate products of given sociological conditions such as language or race or religion; and that they have been, in Europe and everywhere else in the world, imagined into existence’ (2010: 25). Anderson posits that an imagined community is consolidated by the ‘mass ceremony’ (1991: 35) of reading books and newspapers, whereby ‘each communicant is well aware that the ceremony he performs is being replicated simultaneously by thousands (or millions) of others’ (35). Further to this, the nation is ‘imagined as limited because even the largest of them, encompassing perhaps a billion living human beings, has finite, if elastic, boundaries, beyond which lie other nations. No nation imagines itself coterminous with mankind’ (7, author’s italics). Anderson is advocating a distinction between the nation and everything beyond it, maintaining that one needs borders to differentiate between other imagined communities, meaning imagined communities are nevertheless rooted physically.

Rushdie seems to anticipate Anderson (Midnight’s Children being published three years earlier), when he refers to the newly “born” India as ‘a country which would never exist except by the efforts of a phenomenal collective will- except in a dream we all agreed to dream’ (2008: 150). Likewise, Ghosh’s narrator also appears to agree with Anderson that ‘a place does not merely exist […], it has to be invented in one’s imagination’ (Ghosh 2001: 26). Both argue that the nation is, in part, an imagined construct. For the latter, the identity of a place is created and established through stories, photographs and maps. Using such things, Tridib, the narrator’s uncle, stimulates the narrator’s ability to imagine places he has never visited and envisage events he has never experienced. ‘Tridib had given me worlds to travel in’ (24), says the narrator, and thus imagination becomes his guide to perceiving the unknown world, both in India and abroad, beyond Calcutta.

Dipesh Chakrabarty, in his book Provincializing Europe (2000), takes concern with Anderson’s use of the word imagination, arguing that it is conditioned by its Western origins and as such cannot overcome an age-old distinction ‘between an observing mind and its surrounding objects’ (2009: 174). I do not want to dwell on semantics as it is not this dissertation’s focus, but I would take note from Chakrabarty that Anderson’s thesis is – unsurprisingly – founded on Western thought. It occurs to the narrator that all the lines which make up our world as we know it are the product of ‘people, not so long ago, […] who thought that all maps were the same. […] They had drawn their borders, believing in that pattern, in the enchantment of lines, hoping perhaps that once they had etched their borders upon the map, the two bits of land would sail away from each other’ (Ghosh 2001: 286). Those people of “not so long ago” are, of course, the British. Indeed, the historian Ranajit Guha accuses Anderson’s thesis of taking ‘a typically colonialist view’ (1985: 104). Anderson’s emphasis on the mass ceremony of print capitalism, written by an elite minority, leads Guha to conclude that given ‘Britain created the Indian nation and did so by disseminating liberal ideas through Western-style schools and universities among an indigenous elite made up mostly of the landed gentry and professional middle classes’ (104), it is they – the British, and India’s elite – who have imagined the nation. For example, Nehru attended Trinity College, Cambridge. And one can also see this in Midnight’s Children, if one abides by the view that Saleem stands for India, for he attends the Anglo-Scottish Education Society run John Cannon Boys’ High School, and studies works by George Bernard Shaw and the like.

Furthermore, as shown my introduction, India has no unifying language in which to “write the nation”, and besides, India’s illiteracy rate – 26.6% nationally (Kumarl 2016), and much higher at the time of these novels’ publications – render this notion impossible. So not only is Anderson’s thesis not possible for the construction of the Indian nation, but additionally, alternative ways have been adopted. Guha writes that ‘the Indian experience shows that nationalism straddled two relatively autonomous but linked domains of politics – an elite domain and a subaltern domain’ (1985: 105), where only the former can be understood, to an extent, in having utilised print-capitalism. The latter was largely ‘informed by traditional values and beliefs untouched by liberal ideas’ (105), developed within ‘a speech community’ (107).

Guha’s contention is furthered in Saleem’s description of the night of India’s independence, when in Delhi ‘green pistachio is eaten, and saffron laddoo-balls […]. And in all the cities all the towns all the villages the little din-lamps burn on window-sills porches verandahs. While trains burn in the Punjab, with the green flames of blistering paint and the glaring saffron of fired fuel, like the biggest dias in the world’ (Rushdie 2008: 155, author’s italics). The lighting of din-lamps across the country can be read as another form of mass ceremony, a more inclusive one as Dirk Wiemann points out, for it ‘neither require[s] the literacy nor the privacy which the act of reading implies, both of which are not to be taken for granted in an Indian context’ (2008: 76). In this regard, Midnight’s Children mirrors Anderson’s view, albeit taking a much broader view of what mass ceremony can entail. However, I would argue that the novel’s view of India as an imagined limited community is all the more sceptical. The Republic of India’s flag is comprised of a green stripe and a saffron stripe (the former representing Islam, the latter Hinduism), with a white stripe uniting the two. But the burning flames in Rushdie’s novel are only green and saffron, suggesting, along with the violence in the Punjab, that the ‘many-headed monster’ (Rushdie 2008: 317) is already breaking up before it is even created. And indeed, the novel’s final moments, where Saleem tells the reader of his ‘disintegrating’ (643) body, reaffirms this. ‘I shall eventually crumble into (approximately) six hundred and thirty million particles of anonymous, and necessarily oblivious dust’ (43) he says soon into the novel, foreshadowing its later events, where clearly the number of particles reflects the Indian population (at the time of Midnight Children’s publication). Saleem literally begins to crack up, unable to retain wholeness because of the pressure of India’s enormity. This analogous ending argues that one cannot homogenise something so heterogenous, a view furthered by Saleem’s loss of telepathic power when he is in Pakistan, a country which he dubs ‘The Land of the Pure’ (169).

Likewise, Ghosh’s narrator differs from Anderson in his view that, as we have discussed, borders are ‘a mirage’ (Ghosh 2001: 302). Further to my third chapter, the narrator draws another circle of the same radius as his first, this time using the Italian city of Milan as its centre. It is a circle which includes Scandinavia, North Africa and the Eastern Mediterranean. The narrator tries to think of an event happening in one of these places, near the circle’s edge, which would ‘bring the people of Milan pouring out into the streets’ (285). He cannot, other than war, and so concludes that ‘within this circle there were only states and citizens; there were no people at all’ (285). Whilst Anderson’s conception of the nation may function for those within the narrator’s second circle, it does not, in the narrator’s opinion, for the first. For him, the nations of the Indian subcontinent do not operate as exclusive entities. Rather, it is a space of international inclusion, ‘a land outside space, an expanse without distances; a land of looking-glass events’ (275). It is worth noting that in a relatively recent interview, Ghosh says that one such event would be 9/11: ‘the things we had lived with in the subcontinent of my childhood had suddenly come home in America, in Europe’ (cited in Thompson 2016: 167). Yet if anything, this furthers the narrator’s view on false distances. Throughout The Shadow Lines, the narrator places emphasis on stories which ‘could not find their real explanations and meanings if the author only limited his search within “national” borders’ (Zullo 2012: 100); indeed, the novel’s constant to-ing and fro-ing across continents reinforces this.

This chapter has shown, therefore, that Anderson’s specific version of the imagined nation, one which is limited and born out of print capitalism, is disrupted when applied to India, specifically the India that is portrayed in The Shadow Lines and Midnight’s Children. However, that is not to say that a nation does not live in the imagination – far from it. Indeed, as I discussed with regards to Tha’mma, a place is created and lives through memory and imagination.

Conclusion

In my introduction, I – or rather Rushdie – posed the question: ‘Does India Exist?’ (Rushdie 2010: 26). As I noted then, it was a question I intended to explore figuratively; what is Indianness? Can one define what it means to be Indian? How does this identity operate in relation to “the nation”? Indeed, these are all questions which can be equally applied to other “-nesses”, and it should be stressed that by no means is this a suggestion that what I am saying is necessarily exclusive to India. But it is India’s extraordinary and vast linguistic, religious, and cultural multiplicity which makes it particularly notable.

Allow me to briefly reiterate what I have established. I have explored this area through the lenses of Midnight’s Children and The Shadow Lines, which, as I hope I have shown, contribute significantly to this discussion. Both novels purport a hybridised view of India, though Midnight’s Children does so more overtly. Of course, whilst I homed in on only one strand of this hybridity – that is the considerable colonial British influence which is important given the time these two novels are set – this is not to say that there are not others to explore; far from it. And indeed, it would be impossible to extract and compartmentalise all of these for – as in every country – culture and national identity are palimpsests, and though the Republic of India is less than a century old, the subcontinent has been home to civilisation for millennia. Furthermore, when Indianness travels, as shown in my discussion on Ila in The Shadow Lines, it takes on new meanings as it becomes defined by its difference.

There are further questions which I have not had the opportunity to explore but are nevertheless worth considering, including that suggested by Radhakrishnan: ‘Is the “Indian” in Indian and the “Indian” in Indian-American the same and therefore interchangeable?’ (2001: 204). This is particularly pertinent to The Shadow Lines and Midnight’s Children, for Ghosh and Rushdie are writers of the Indian diaspora. Does this, therefore, make their portrayal of India any less “authentic” or valid? After all, both are in a position whereby they are interpreting India for the West, writing in the West’s hegemonic language as citizens of the West. But as my discussion in Chapter Three showed, there is a certain arbitrariness to citizenship and identity labels. Their lack of Indian passport does not disqualify them from being and feeling Indian. Yet place of birth should not dictate either; Sonia Gandhi, current President of the Indian National Congress, was born and raised in Italy to Italian parents, yet to say she is not Indian, nor has the right to speak about India, would be an unsustainable position. As Shashi Tharoor writes, ‘fair-skinned, sari-wearing and Italian-speaking […] Mrs. Gandhi is no more foreign to my grandmother in Kerala than one who is “wheatish-complexioned”, wears a salwar-kameez, and speaks Punjabi’ (2000: 105). Furthermore, one can argue that living abroad allows Ghosh and Rushdie to inhabit the role of native informant, taking the position of both insider and outsider; as argued with regards to Ila in The Shadow Lines, Ghosh and Rushdie are able to view their “given” culture in a new light. Consider the city of Bombay, which features heavily in Midnight’s Children; Rushdie lived there until the age of fourteen, but not since. His living in London has, by his own admittance, physically alienated him from Bombay – and India – and thus he ‘create[s] fictions, not actual cities or villages, but invisible ones, […] Indias of the mind’ (Rushdie 2010: 10). In this regard, the nation is imagined across borders, too.

Hence I return to the central focus of my final chapter; whilst I contended Anderson’s specific view of the nation as an imagined community, I do not refute that the nation does not live in the imagination. India, like any nation, exists as a physical place, but it also exists on another level; without the imagination, one would not have Indianness. Indeed, both Midnight’s Children and The Shadow Lines are, as novels, works of the imagination, but they are also versions, interpretations, of India. Of course, one must acknowledge that both novels are primarily focused on a certain Indian demographic, the middle-class India of the authors, and as such one could never posit that these are representatives of an entire nation. In that sense, as Saleem rightly says, ‘there are as many versions of India as Indians’ (Rushdie 2008: 373). Yet as for how one defines Indian, that is, as this dissertation has shown, not fixed either; it is a very generous term, for there is no one right way to be so.

Bibliography

Anderson, Benedict. 1991. Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. New York: Verso.

Anonymous. 1964. “Missing Relic Found After Nine Day Search” Hindustan Times, 5 January.

Benedikter, Thomas. 2009. Language Policy and Linguistic Minorities in India: An Appraisal of the Linguistic Rights of Minorities in India. Münster: LIT Verlag Münster.

Bhabha, Homi K. 1994. The Location of Culture. London: Routledge.

Bradnock, Robert W. 2015. The Routledge Atlas of South Asian Affairs. London: Routledge.

Brooks, David and Nicéphore, Anastasia. 2014. Diasporic Identities and Empire: Cultural Contentions and Literary Landscapes. Cambridge: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

Burton, Eric. 2013. “‘…what tribe should we call him?’ The Indian Diaspora, the State and the Nation in Tanzania since ca. 1850” Wiener Zeitschrift für Kritische Afrikastudien. 13:25. pp. 1-28.

Chandra, Anjara M. 2008. India Condensed: 5000 Years of History & Culture. Singapore: Marshall Cavendish International Asia.

Chakrabarty, D. 2009. Provincializing Europe: Postcolonial Thought and Historical Difference. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Chatterjee, Partha. 2010. Empire and Nation: Selected Essays. New York: Columbia University Press.

Cixous, Helène. 1998. Stigmata: Escaping Texts. London: Routledge.

Collins, Larry. and LaPierre, Dominique. 1997. Freedom at Midnight. London: HarperCollins.

Dodiya, Jaydipsinh. 2006. Perspectives on Indian English Fiction. New Delhi: Sarup & Sons.

Doshi, S L. 2008. Postmodern Perspectives on Indian Society. Jaipur: Rawat.

Gabriel, Sharmani Patricia. 1999. Constructions of Home and Nation in the Literature of the Indian Diaspora, with Particular Reference to Selected Works of Bharati Mukherjee, Salman Rushdie, Amitav Ghosh and Rohinton Mistry. University of Leeds.

Gabriel, Sharmani Patricia. 2005. “The Heteroglossia of Home” Journal of Postcolonial Writing, 41:1, pp. 40-53.

Garg, Promilla. 2008. “A Post-Colonial Interpretation of The Shadow Lines” In Amitav Ghosh’s The Shadow Lines: Critical Essays. Ed. A Chowdhary. New Delhi: Atlantic Publishers, pp. 169-177.

Ghosh, Amitav. 1989. “The Diaspora in Indian Culture” Public Culture 2:1, pp. 73-78.

Ghosh, Amitav. 2001. The Shadow Lines. London: John Murray.

Gist, Noel Pitts. and Wright, Roy Dean. 1973. Marginality and Identity: Anglo-Indians as a Racially Mixed Minority in India. Leiden: EJ Brill.

Government of India, Commissioner for Linguistic Minorities Ministry of Minority Affairs. 2014. 50th Report Of The Commissioner For Linguistic Minorities In India (June 2012-June 2013) New Delhi.