Impact of Second Language Acquisition on the Individual and Society

Info: 19977 words (80 pages) Dissertation

Published: 11th Oct 2021

Tagged: Languages

Being Bilingual: The effects and impact of second language acquisition on the individual and society.

Abstract

The aim of this research is to ascertain the benefits of bilingualism alongside the impact that learning a second language can have on both the individual and the society in which they are integrated within. The factors and variables that influence bilingualism is considered and compared to see if there are any advantages to being bilingual, for both the individual and society. This dissertation shall be exploring biological and neurological factors that contribute toward language acquisition and the way in which individuals learn and acquire SLA (State, 2014). Research is continuously taking place to try and understand exactly how the brain learns language, therefore this dissertation will aim to explore this further and the results of SLA on the brain. Furthermore, the essay investigates the cognitive functions that are impacted and the advantages or struggles that may transpire. Research involving motivation and attitudes will be explored to see if these have an impact on whether individuals are more susceptible to language learning leading closely to globalisation and education. The second half of this dissertation shall aim to consider how bilingual effects the world around us and what bilingualism impacts through both trade and socialisation and how this links closely to motivation.

Acknowledgements

There are so many people I would like to thank for guiding and supporting me throughout my degree. Firstly, thank you my dissertation supervisor for offering encouragement, support and helping me make sense of my obscure ideas likewise, Paddy for being my listening ear and giving me so much guidance in the final stages. I would also like to thank my partner, I owe so much to Marco, who has listened to my cries of frustration and stood by helping any way he can, making sure that I still remember to have fun in times of crisis and no matter what, listens and tries to help in any way he can, I could never ask for a more amazing person to share my life with. Thank you to all my friends who have been here no matter what, particularly Sonny who is the best cheerleader I could ask for. Lastly, I owe the most to Kirsten, without who I never would have made it through, by being able to have someone stand by my side while making me laugh no matter what, has shown me what an incredible friendship we have.

Contents

Abstract 3

Acknowledgements 4

Introduction 9

Chapter one

1.1. Prenatal development 11

1.2. Lexical stress 11

1.3. Gender Gap 12

1.4. Broca’s area and Wernicke’s area 13

1.5. Behavioural deviations 14

1.6. Delaying the onset of Alzheimer’s 15

1.7. Critical learning period 16

Chapter Two

2.1. Information processing 18

2.2. Cognitive development theory 18

2.3. Four stage model of SLA and social interaction theory 19

2.4. Language delay 20

2.5. Code switching and language interaction 21

2.6. Cognitive consequences 22

Chapter Three

3.1. Attitude and Motivation 24

3.2. Opportunity and motivation 25

3.3. Behavioural factors 25

3.4. Language and emotion 26

Chapter Four

4.1. Second culture acquisition 27

4.2. Society and culture 28

4.3. Socialisation 28

4.4. Communication Technology 29

4.5. Globalisation 30

4.6. Economics and language 31

Chapter Five

5.1. Development of SLA 32

5.2. Teacher and learner relationship 32

5.3. English education system with regards to languages 33

5.4. Worldwide education system with regards to languages 34

5.5. Societal power 34

Conclusion 36

References 39

"The limits of my language mean the limits of my world.” ― Ludwig Wittgenstein, 1922

Introduction

This dissertation examines and compares the role and effects of learning a second language along with the outcomes it can have on individuals. It will seek to advance knowledge while interrogating the varying factors and influences that learning a second language can have both on the individual and society (Byers-Heinlein et al., 2010). Whilst it may be argued that there are many benefits and advantages to learning a second language, especially for individuals living within Britain and for British society itself, the limitations and opportunities also relate closely to children’s development; a subject that will be revisited throughout (Callahan and Gandara, 2014). The significance of bilingualism is that language is often described as a human communication system so unique, that it has been made an inclusion factor of what it means to be human. It is a system of communication used by a community or country, either spoken or written, language can be used to express and communicate to others alongside providing a way in which society can progress and develop. Although, it has been suggested that communication is possible because language represents both ideas and concepts that exist independently of and prior to language (Bett, 2010).

This dissertation shall take the form of an essay to examine all the different contributors, each taking the form of a chapter and exploring the subject matter further whilst relating to theories concerning bilingualism and the influences it has. However, this essay will aim to avoid eurocentrism, the excessive focus on European languages which is often found when discussing linguistics. As of 2015, English is the official language of 53 countries around the world with an estimation of 7000 languages spoken in total (Central intelligence Agency, 2015). Despite this, the ability to learn a second language is not highly regarded within the British National curriculum. Since the review in 2013, computing has taken a priority over learning a second language, learning a foreign language is not compulsory until KS2 with only the basics being touched upon (DfE, 2014, p.7). However, a recent survey showed that London is the most linguistically diverse area, with 45% of primary school children recorded that they had a language other than English spoken at home (Board and Tinsley, 2014).

Furthermore, statistics from 2016 shows that, out of the world population of 7 billion, 1,500 million people worldwide speak English of whom only 6% are native speakers, this amounts to 21% of the world’s population able to speak English (Statista, 2016). The ability to speak English, is encouraged all around the world, many countries include learning English as a second language within the school syllabus, as it is argued that learning English will increase your chances of employment (Cummins and Davidson, 2007). This is based on the idea that English is seen to be the language of: science, computing, aeronautic, diplomacy and tourism, alongside being the language of both media and the internet industry (Oxford Royale, 2014).

This dissertation shall be split into two parts, with the first part observing psychological contributors and the second part observing further into sociological aspects.

The psychological section shall be split into three chapters with chapter one concentrating on biological and neurological factors that contribute toward language acquisition and the way in which individuals learn and achieve Second language acquisition (SLA). Research is continuously taking place to try and understand exactly how the brain learns language, therefore in this chapter it will aim to explore this further and examine the results of SLA on the brain.

Chapter two will be considering cognitive factors and observing further into how SLA is developed along with the idea that bilingualism can benefit or hinder cognitive development.

Chapter three shall be considering affective variables, observing the role and impact that attitude and motivation has on SLA in addition to the behavioural factors, this chapter shall explore the link between emotion and language.

The sociological section shall be split into a further two sections with chapter four observing culture and society. It is within this section that we begin to see the links between differing cultures and language along with the difference between societies’ motivations behind learning a second language.

Finally, chapter five shall consider bilingual education in both British society and worldwide in addition, the benefits of bilingual education while considering society’s view on involving language with education In this dissertation, the notion of bilingualism shall include both bilingual and multilingual individuals.

There are many different definitions to what is meant by bilingualism, with a further four different categories regarding bilingual acquisition. Beginning with infant bilingualism, which results in the individual learning two languages from the offset. Followed by child bilingualism, which involves successive attainment, this is next followed by language acquisition after puberty. The finally category is adult bilingualism which involves language procurement after the teen years.

Language is obtained and learnt throughout an individual’s childhood with many different factors playing a role into how developed the individual will become. The scientific study of language is linguistics, after much research it is now understood that being bilingual is more complex than having two monolinguals within one person (Grosjean , 1989). Whereas, Second Language Acquisition (SLA) is the process by which individuals learn a second language (L2) or any other language after their mother tongue (Myles, 2000).

There are various theories surrounding SLA based around two main areas of focus; linguistic and psychological. Regarding linguistic theories, Chomsky argues that language is acquired in a reasonably short period; this would not be possible if the human did not have an innate language facility. However, Chomsky continues to argue that this natrual language facility is dependent on more than language input alone, it is a combination of innate, biological and grammatical categories (Berwick and Chomsky, 2016).

This has been criticised, as there is no true definition of a short time and so there is no way to measure or confirm what it means to acquire language in a reasonably short period. In addition, critics also mention that it does not deal at all with the psychological processes involved with learning a language (Smith, 2004). In contrast, Krashen (Benthin, 2015) developed the input hypothesis, a group of five hypotheses all relating to SLA.

According to this theory the input hypotheses states that learners can progress when they are surrounded by language at a higher level than they speak. Acquisition learning hypothesis claims that there is a clear separation between acquisition and learning which involves the subconscious, whilst the monitor hypothesis claims that consciously learnt language can never be the source of spontaneous speech. On the other hand the affective filter hypothesis states that an individual’s ability to acquire language is constrained if they experience negative emotions such as distress or embarrassment (Benthin, 2015). Whilst the input hypotheses have had a great influence on language education, it has been criticised deeply; it has been argued that despite Krashen perception of acquisition as a subconscious process and learning as conscious, these have not been proven to exist, in addition the hypothesis is unable to be tested (Rebuschat, 2013).

Chapter One

This chapter aims to examine the biological and neurological components of language development, alongside the critical period within which a second language should be learnt. It will seek to consider if there are any neurological advantages to studying a second language and how they influence the acquisition of language itself.

1.1 Prenatal Development

Throughout an individual’s life the brain links closely with biological and neurological factors all of which play a vital role regarding human development and communication which relate closely back to language development (Singleton and Ryan, 2004).

Contemporary findings have found that language acquisition begins before the birth of the child, resulting in the uterus becoming a big part of an individual’s language development. Prenatal sensory experience shapes the structure of the brain, which begins the developmental process for language (Talaber, 2011).

A child learns their first language from four months while inside the womb through visceral noises from the mother’s body and the surrounding environment, the child is able to retain memories of the sounds after their birth. Research shows that it is estrogen that plays a dual role and modulates the gain of auditory neurons cellular process that enables activation of auditory senses and memory formation when in the womb (Pinaud,2011). Therefore, it is argued to be a critical period for the fetus for both survival and the transition to the postnatal world (Hepper, 2015).

Likewise, corresponding findings have discovered that children can learn their first lullabies in the womb from the mothers and surrounding environment, potentially supporting later speech development (Yliopisto, 2017).

Furthermore, a recent study argues that the environmental sounds that the fetus hears, including speech and songs are background noise become recognised by the fetus and persists for at least four months after birth, with no stimulation (Partanen et al., 2013).

1.2 Lexical Stress

The patterns of language that the individual experiences while in the womb are referred to as lexical stress. These include loudness, vowel length and changes in pitch, all which give prominence to a given word or sentence, making the language unique (Field, 2005).

English uses variable stress, while languages such as French are more syllable based languages, resulting in newborns being able to distinguish a difference between stress based English and syllabic based French. However, this is not always a given as a newborn would continue to struggle to tell the difference between English and Dutch which is also stress based (Yang, 2010).

Similarly, children who have been exposed to both languages while in the womb showed no favour to either language once born (Buyer-heinlen et al, 2010). However, they could distinguish that the languages were not the same and each held a different rhythmic pattern.

Moreover, while monolingual individuals showed that they preferred listening to their mother tongue rather than a language they had not previously heard, further search shows that infants are able to discriminate between the two separate languages from birth (Rowland, 2013).

1.3 Gender Gap

Vast array of studies implicates a significant gender gap regarding SLA, however, it is also suggested that gender distinctions are as much cultural as they are language (Cohen, 2011). Conclusive research displays that males have more advanced motor abilities in comparison to females, who obtain more advanced social cognition skills alongside an innovative memory.

From this it has been concluded that the structural makeup of the human brain, enables females to learn and develop second language easier, it has been shown to be most prominent at stages which involve grammar and vocabulary (Ingalhalikar et al, 2015). However, this idea has been criticized as it is seen to be more difficult given the differences between biological gender and gender roles (Lindsey, 2015). Yet, there were seen to be very few differences in the size of structures in both the Broca’s and Wernicke’s in both men and women (Leonard et al., 2008).

Further studies, conducted in the Netherlands, have analysed findings from bilingual individuals in both native and second languages. Results showed that female learners consistently outperformed males in both speaking and writing proficiency. In contrast, with regards to reading and listening skills there was no gender gap to be found (Van der silk, Van hout and Schepens, 2015).

Likewise, many supporting studies aimed to explore how the findings link with further influences, the findings focused attention on second language acquisition being both nature-based and genetic-based. This also interacted closely with the surrounding environmental factors, such as self-motivation and education; both factors that also mediate second language acquisition, ideas shall be further explored in Chapter four (Van der silk, Van hout and Schepens, 2015).

1.4 Broca's Area and Wernicke's Area

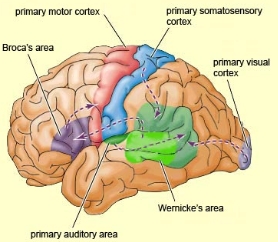

From studying the brains of individuals who were bilingual and able to comprehend both language before the age of 7, recent research has found that no spatial separation is to be located in either the Broca's areas or Wernicke's area (Rilling, 2014) (See figure 1). This links closely with the idea that the ability to process both languages is controlled by the same regions of the brain, rather than in differing subsections (Bishop, 2013).

Furthermore, FMRI studies of children's brain development show that second languages learned early in childhood are not separately processed in the brain (Hernandez et al., 2001). The ability and need to be able to first understand which language the individual is receiving and then continue to understand the language itself is referred to as code-switching (Aron, Robbins, and Poldrack, 2014).

A report from the UCLA suggests that it is during the ages of 6-13 when the brain goes through the most growth, it is during this time that the brain is biologically most advantageous for SLA (Tommasi, Peterson, and Nadel, 2009).

In addition, further research has concluded that there are two forms of bilingual brains; brains that become bilingual at an early age and brains that become bilingual as adults (Abutalebi and Rietbergen, 2014).

Overall, it has been concluded that individuals that acquire either child or infant bilingualism develop a Broca’s area that works as a complete unit when speaking a second language, rather than working as separate parts. Although both languages are stored in the Wernicke’s area, an individual that has learnt a language at an early age has an interconnection between both languages and hence use the same region within the Broca’s area for both languages, even though only one language is being used to process thought and speech (Weber et al., 2016).

In contrast, individuals who acquire adult bilingualism, show that the native and second languages are separated in the Broca's area, which is responsible for the motor parts of language movement, while there is very little separation in the Wernicke's area, which is responsible for the comprehension of language (Garbin et al., 2010). Whilst adult learners have more facility when understanding language in comparison to when producing it, young learners do not encounter this difficulty as there Broca’s area is working as a complete unit providing them with language productivity (Jasinska and Petitto, 2013). This correlates with past neurocognitive studies which imply that the areas surrounding the Broca’s area are vital to the memory in both non-linguistic and linguistic tasks (D’Esposito et al., 1999).

Further research suggests that the Broca’s area is most involved with articulation, giving reason to believe that its main role is fundamental to the working memory functions of the frontal area (Miller and Cummings, 2014). From this, it is argued that there is a strong correlation between psychiatric disorders and the hypoactivity of the Broca’s area, these correlations link closely to disorders such as ADHD, Bipolar, and anxiety (Cohen, 2011). Current research indicates a link between bilingualism and ADHD, in particular bilingualism from an early age, despite limitations of control factors, there is enough evidence to suggest that bilingualism has a positive effect on inhibitory functions alongside behavioural responses (Beck, 2014).

A recent study investigated functional abnormalities within the Broca’s area in adolescents with ADHD, the results showing a positive correlation between fractional amplitude of low-frequency fluctuations which reflects spontaneous neural activity and adolescences with ADHD. The findings lead the research to understand that there are functional abnormalities in the Broca’s area for individuals with ADHD, furthermore it has been argued that the location of these abnormalities could link with particular language discrepancies (Pikusa and Jonczyk, 2015).

Correspondingly, bilingual individuals have a faster reaction time and can take advantage of alerting cues provided by society (Costa, Hernández, and Sebastián-Gallés, 2008). Other studies have shown that by increasing the rate in which children gain inhibitory control, the child develops the ability to regulate attentional and behavioral responses and focus on the relevant stimuli surrounding them (Carlson and Meltzoff, 2008). While others argue that it is bilingualism that helps and supports both attention and inhibit action through the process of code-switching, hence strengthening the Broca’s area along with the ability to focus, code-switching shall be discussed throughout this dissertation (Boeree, 2004).

Studies involving Positron Emission Tomography have shown that those individuals that have a stutter or a lack of fluency while speaking present hyperactivity in the motor cortex, yet hypoactivity in cortical areas of the brain, the Broca's area (Sandak and Fiez, 2000).

Additionally, there is a link between specific language impairment which is also developed due to a hypoactive Broca's area and the difficulties that can be encountered including slow development, physical abnormalities of speech apparatus (Roeper, 2011). An individual who is bilingual has both languages always active and competing, resulting in the individual using control mechanisms every time speech is both heard and spoken. By constantly putting these skills into practice the brain adapts and changes the correlated Broca's area (Marian, Shook, and Schroeder, 2013).

1.6 Delaying the onset of Alzheimer's

Further studies by Carlson and Melzoff (2008) concluded that bilingual individuals outperformed their monolingual peer’s significantly due to their advanced inhibitory control. New research has shown a that bilingualism can help delay the onset of Alzheimer's, by the brain constantly controlling two languages it engages the brain and challenges the grey matter which prevents it from deteriorating (Mortimer et al., 2014). However, many critics have suggested that more research needs to be done to understand this idea further and look into how the Broca's area and Wernicke's area work together with grey matter; current MRI scans have shown that bilingual individuals hold a higher density of both grey and white matter (Woumans et al., 2014).

A recent study was conducted by Olsen et al., (2015) researching if the frontal lobes are also sensitive to bilingualism, hypothesising that bilinguals shows greater frontal lobe white matter in comparison with monolinguals. Moreover, monolinguals showed that during the ageing process there was a decrease in temporal pole cortical thickness, however there was no such correlation showed for bilinguals (Olsen et al., 2015). Implicating a link between bilingualism and the preservation of frontal and temporal lobe function during ageing. This idea and evidence is further supported by the argument that having gained bilingualism at an early age is another contributing factor to the onset of Alzheimer's disease (Craik, Bialystok, and Freedman, 2010). Popular opinion states that younger children find it easier to learn a second language alongside being able to retain the information for longer because childhood is a critical period in which language learning takes place (Meulman et al., 2015). The critical learning period, is seen as the period in which an individual must begin to learn the language or become exposed to the language in order to learn the language to the best of their ability (Birdsong, 2013).

From this, it is suggested that children have a natural ability to learn and that by learning a second language before puberty the mind is being challenged and enhanced, in turn language allowing for more easy acquisition of language (Long, 2013). Despite the nature of languages being learnt differently, recent data revealed a steep decline in the learning of grammar of a second languages up to the age of 18, hence supporting the idea that the early learners are in the critical period (Deskeyer, Alfi-Shabtay, and Ravid, 2010). Recent statistics have revealed that by the age of four, 50% of our ability to learn is developed with a further 30% being developed by the age of eight; these statistics mainly concentrate on the main learning pathways (Brain and Mukherji, 2005).

In accordance with this, it is argued that adult learners struggle to acquire a second language to the same fluency, it has been indicated that as few as 5%, maybe fewer could ever achieve native-like fluency in their second language (Miller, 2004). At a younger age the brain is much more susceptible and flexible in comparison to an adult, however after the age of nine the brain begins to mature and becomes less flexible and accommodating to change (Moyer, 2004).

Overall, brain development regarding Second language acquisition links closely to lateralisation which refers to the dominance of certain cognitive processes in a particular side of the brain (Sommer and Kahn, 2009). The whole process of lateralisation isn't completed until just before puberty, with the whole process complete this results in the brain being too developed and losing its plasticity resulting in a difficulty regarding fluidity (Davide, 2014).

To conclude, biological and neurological components of language development have a supporting role regarding an individual’s SLA. Linking closely with both hormones and gender, bilingualism affects the brains structure, correlating with higher grey matter volume in the left inferior cortex (Fabbro,2000). From the conducted research, it can be observed that a bilingual experience changes neurological structures and how the individual process information alongside altering the neurological structure itself. It has been further argued that bilingualism helps and supports both attention and inhibitory action through the process of language, hence strengthening the Broca’s area along with the ability to focus (Boeree, 2004).

Chapter Two

This chapter shall be investigating the cognitive influences, with focus on how the learners’ mental processes influence their learning, thinking and memory. By looking at how cognitive approaches to language are generally characterised, we are able to query the way in which the human mind deals with learning, and how learners use their knowledge in speech and to understand their languages (Juffs, 2010).

This chapter will also consider if there are any cognitive benefits of being bilingual and how they will continue to be of an advantage as the learner develops and matures.

2.1 Information Processing

The idea of information processing compares the human mind to a computer. From this idea, it is suggested that like computers human are information processors, taking information and following a program to produce an output. From this it is possible to investigate the link that lies between the stimuli and the response that we provide (Grosjean, 2010).

This idea is heavily critiqued by behaviorism, which emphasises the role that the environment has on an individual’s behaviour. It assumes that all behaviours are a consequence of an individual’s history, including reinforcement and punishment (Watson, 2010). It is further argued that through observation the individuals may try and imitate the behaviour or language displayed to them; if the imitation is received well and responded to by the surrounding environment, this results in the behaviour reinforced either negatively or positively (Kostelnik et al., 2014).

2.2 Cognitive Development Theory

Changing the behaviour or actions through the use and result of reinforcements acting as either a stimulus or reward is further known as conditioning (Hergenhahn and Olson, 2008). Much of the work regarding cognitive development relates back, or aims to contradict Piaget's theory of cognitive development, which considers the nature and development of human intelligence (McLeod, 2009).

Although Piaget’s theory is mainly focused on language acquisition, it can easily be correctly applied to second language acquisition. Piaget focuses on two main processes, being assimilation and accommodation. Assimilation is how humans perceive and adapt to new information presented to them, whereas accommodation is taking new information and altering pre-existing schemas to fit in with the new information; Piaget argued that one was unable to exist without each other (Berger, 2011). Piaget's work has not gone by without much criticism as it was firstly criticised that child development is not always able to progress smoothly. Likewise, it has been suggested that Piaget undervalues the influence that culture has on cognitive development (Slee and Shute, 2014).

In addition, cognitive development theory has been criticised for not regarding social interaction which teaches the individuals about the surrounding world and helps develop the individual through the cognitive stages (Kail, 2009).

2.3 Four Stage Model of SLA and Social Interaction Theory

Using Piaget's work as a base, Klein (1999) developed a four-stage model of second language acquisition, in which it is claimed that the majority of adult learners will pass through these stages with some degree of uniformity (Piaget et al., 2001).

During the first stage of the process, borrowing takes place in which the individual begins to replace key words with the new language learnt.

In the second stage, the lexicons are firmly grounded and the process of translation begins to take place and the two linguistic systems also begin to separate and strengthen individually.

The third stage consists of the two participating linguistic systems beginning to separate further, and reinterpretation and translation, which is both complex and bidirectional begins to come into play.

At the final stage of the model, Klein (1999) argues that the emergence of individual constraints take place, relying heavily on confidence and the motivation that the individual may have received; the idea of motivation shall be discussed further in chapter three.

A second theory that plays an important role regarding cognitive influences is Vygotsky's theory as it differs from Piaget's theory in several important ways (VanPatten and Williams, 2016). Vygotsky’s theory places more emphasis on how the surrounding culture affects cognitive development, contradicting Piaget's idea that cognitive development is not varied depending on culture (Rothman, 2009).

Vygotsky also considers the social factors and how they contribute to the development in addition to different emphasis on the role language plays in cognitive development (Lantolf and Poehner, 2014). From these ideas, social interaction theory is formed, a concept that is based around the role that social interaction has between both the developing individuals and society or linguistically able adults. It emphasises the role of social interaction, suggesting that individuals learn language from one another via observation, imitation and modelling relating closely with the idea of behaviorism (Payne, 2014).

There are many milestones regarding child development and second language acquisition. By surrounding themselves during the ages of 2-3 with language that is being spoken correctly means that the children are supplied with an active learning environment. This supports the use of grammar through both lessons and exercises, linking closely with social interaction theory (Robinson, 2008).

Further research shows that, after the age of 5 semantics are not affected as much by environment which surrounds them, dissimilar to pronunciation and grammar both which will always rely heavily on the surrounding environment (Robinson, 2008). This research also highlights that the left hemisphere is most active in grammatical processing and code-switching tasks (Kovelman, Baker, and Petitto, 2008).

The next significant milestone is at five years old when you maintain a discourse organisation and have a vocabulary of over 2000 words which you continue to develop further. Whilst it has been previously argued that bilingualism can disadvantage children, as at first they are seen to develop smaller vocabulary along with poorer grammar and writing skills (Ribot, Hoff, and Burridge, 2017).

2.4 Language Delay

Despite the original delay of the onset of languages, bilingual children develop grammar along the same patterns and timelines as their monolingual counterparts (Genesse, 2009). There is much conspiracy that being bilingual can cause a language delay, an ideology is based on the idea that rather than a child concentrating on one language, they have to split their resources over two languages (Junker and Stockman, 2002). Although there are many differences regarding language development between monolinguals and bilinguals, it has been investigated that if only one of the two languages are considered, the vocabulary content for bilinguals is much lower than monolinguals (Patterson, Barbara, and Rodriguez, 2016); ‘The mind is not a container with a limited capacity for language, there is no truth in the belief that the use of more than one language necessarily reduces the individual’s ability in each language’ (Whitehead, 2002, P.21).

This idea has been developed and investigated, with the result of a comparable study concluding that while bilinguals have a limited vocabulary in comparison to monolinguals, bilingual individuals catch up to their monolingual counterparts in both languages before the age of five (De Houwer, 2009). Continuing with the problems that bilingual children may encounter Genesse (2009) discusses how a child’s ability and competence is reflected in the amount of time that the child spends in each of the other languages.

This idea is supported through children who may have family abroad and spends a certain amount of time with them during the year, where in this time only one of the languages is used. However, it is noted that while the child may lose proficiency is one of the language when it is not in used, this a temporary shift that will revert back after exposure to the language is sufficient (Genesse, 2009).

2.5 Code Switching and Language Interaction

Code-switching occurs when individuals alternate between multiple languages within a single conversation, offering another language to use when words in the native language are inadequate (Hughes et al., 2006). Many disadvantages to code-switching have been presented as a sign of delay in language ability, as bilingualism is viewed as either a subtractive or additive language process; subtractive refers to the increasing fluency of one language while the ability in the other language is decreased (Hughes et al., 2006).

Many children who are raised as bilingual face the challenge of sorting out the languages learnt, which can lead to mixing languages, although temporary, language mixing can help develop the code-switching skills which the child will later develop as a result from being bilingual (Auer, 2014). This is seen throughout the world, an example being Spanglish, which is commonly used by Latinos in the United States (Gardner-Chloros, 2009).

Overall, one language generally has a stronger influence within the child's life than the other and as a result they often draw on this language when speaking the minority language, as it is this language that may have developed a small vocabulary (Sebba, Mahootian, and Jonsson, 2012).

It has also been proposed that bilingual children may say their first words slightly later in comparison to monolingual children, but still within what is classified as the normal age range of 8-15 months (Meisel, 2004). Yow (2014) measured bilingual children’s speech capabilities in both languages to investigate code-switching, findings demonstrating that children who regularly code-switched were able to have a more advanced knowledge of their second language. Other findings have shown that code-switching enhances the ability to express emotions along with communication and the development of languages (Lee and Wang, 2015).

2.6 Cognitive Consequences

In recent years, bilingualism has been linked to a number of cognitive consequences in particular cognitive control. Research has studied how an individual’s languages interact with one another alongside the influence that the languages have on each other. (Antoniuo et al., 2014).

Research involving linguistic development and inhibitory control has suggested that bilinguals benefit from cognitive advantages and, in turn, outperform monolinguals in certain areas that are associated with cognitive domains including faster reaction times and more cognitive control which could reveal a bilingual advantage (Pelham and Abrams , 2014).

To manage the balance between two or more languages that are always active and competing, the brain develops more advanced cognitive mechanisms. These depend on executive functions that include processes such as attention and inhibition as discussed previously in chapter one (Barac and Bialystok., 2012). It is suggested that cognitive control outcomes for bilinguals vary due to the amount of experience managing the bilingual demands that may be encountered (Macnamara and Conway, 2013).

Moreover, research suggests that introducing a second language at an early age can have a positive impact on cognitive development, rather than hinder the child's performance. By confusing the child, the second language interferes with the child's ability to develop what society would classify as normal cognitive functions (Bialystok, 2008). However, this idea has been explored further and resulted in bilingualism being viewed as positive force that enhances children's linguistic and cognitive development.

Likewise, it affects the individual’s ability to solve problems, in particular those that involve a high level of language processing (Bialystok, 2009). The cognitive consequences of bilingualism extend from early childhood until old age, as the brain becomes more effective and efficient at being able to process information and in turn delays cognitive deterioration (Li, Wu, and Liu, 2013).

It has been further acknowledged, that a second language enriches and enhances a child's mental development as discussed earlier, leaving learners with the ability to think on a broader scale alongside a greater sensitivity to language as it helps to develop their understanding of the native language (Green, 2009).

Furthermore, research has shown that control and analysis are components that develop a lot later in monolinguals than in bilinguals because of the cognitive control that is gained from managing two languages (Bialystok, 2007).

To conclude, we can see many outcomes that result in an advantage in both cognitive and linguistic development with regards to bilingual children (Turnbull, 2016). Cognitive research has shown that through the experience of two language systems being produced, bilingual children are left with a more flexible and diverse set of mental capabilities. This includes an advantage in working memory and sustaining attention and language, alongside the ability to process and adapt information both efficiently and effectively (Ilieva and Farah, 2013). The cognitive consequences of bilingualism stem from childhood to maturation; as the brain continues to develop and process information, not only is the relevance of child bilingualism apparent but also adult bilingualism, although it is not as advanced (Collins and Frank, 2013).

Moreover, the cognitive control along with metalinguistic awareness, enhanced memory and creativity highlight the importance of how bilingualism affects the activity and development of the brain (Chan, 2004).

Chapter Three

This chapter aims to explore attitudes and motivations, in addition to what means these affective variables relate closely to, such as moods, feelings and attitudes throughout SLA. Affective variables are of considerable importance regarding language learning being successful (Sturgeon, 2016).

3.1 Attitude and Motivation

It is argued that an individual’s motivation behind learning a second language and the attitude they hold regarding second language acquisition influences the proficiency of the learner (Mitchell, Myles and Marsden, 2012).

Likewise, it has been argued that learners that study a language with the aim of advancing their knowledge and understanding of culture and society are more motivated to learn (Ishihara and Choen, 2014).

In recent years, there has been a heightened interest regarding attitudes and motivation concerning SLA, in particular research has begun to look in to the idea of why individuals may have a negative attitude towards learning a second language (Dornyei and Ushioda, 2013). It is suggested that attitude and motivation are the most influential factors in successfully learning a second language, the definition of motivation being multifaceted as it involves both cognitive and behavioural elements (Ellis, 2009). Gardener (1985) defines that motivation consists of four main components, otherwise referred to as affective variables; Goals, desire to achieve the goal, positive attitudes and effort (Pawlak, 2015).

These affective variables differ from cognitive factors as they are associated with related influences such as intelligence and aptitude, which impact and combine the individual’s autonomy and self-esteem, subsequently promoting positive attitudes and enhancing motivation (Alrabai and Moskovsky, 2016). The socio-educational model proposes that there are two individual variables: ability and motivation resulting in two main influences. Individuals who have either higher intelligence or higher levels of motivation will be more successful at learning a second language than those who obtain lower levels (Chambers, 1999). However, Gardener (2010) argues that although in a classroom setting ability and motivation will be of equal involvement, it is in the informal environment that motivation will always be more crucial.

Throughout the years, the socio-educational model has been revised many times, each time trying to improve upon criticism. Many critics have intended to expand the socio-educational model to include additional motivational variables, in addition to base their model on more consistencies when considering the impact of attitudes on language development (Csizer and Magid, 2014).

3.2 Opportunity and Motivation

Opportunity and motivation work together as one to affect language acquisition. Krashen (2003) argues that motivated students are more likely to seek out opportunities that put to use language skills.

Moreover, learner’s affective factors in particular motivation are of crucial importance when considering individual differences with regards to learning outcomes (Ni, 2012). The suggestion that there are two types of motivation (Gardner, 2010) introduces the idea that each individual’s learning may be affected differently. Individuals from countries that have more than one official language could be seen as being more motivated in order to connect with the surrounding community or another culture, otherwise known as integrative motivation. In comparison to those that learn a language to achieve a personal goal, or because it will serve a purpose, are instrumentally motivated, sequentially, making language acquisition more successful as it will serve a purpose which in turn may help them to succeed (Filmore, Kempler and Wang, 2014).

Similarly, learners that require the English language for a more advanced career are instrumentally motivated more than those that have already inherited the English language, or those that do not require it (Dörnyei, 1998).

Moreover, the learner’s motivation towards SLA is crucial as the stronger motivation will result in a more positive attitude in comparison to an individual who lacks motivation, resulting in a negative attitude.

Motivation is not always constant and when negative attitudes are projected or prejudices are portrayed against the language the motivation can be diminished (Mercer, 2014).

3.3 Behavioural Factors

There are many behavioural factors that come into play regarding second language acquisition. These include extrinsic factors involving the environment, in addition to the willingness to do something due to its separable outcome intrinsic factors which involve the individual at hand, basic human needs, in addition to the internal desire to do something because it is worthwhile (Mercer,2014).

Intrinsic factors consist of motivation, self-esteem, attitude, and the desire to understand and learn the new culture they are immersing into (Sanz, 2005). The self-determination theory concentrates on both the intrinsic and extrinsic aspects of motivation, concerning itself with innate psychological needs by focusing on the degree to which an individual’s behaviour is both self-motivated and self-determined (Dörnyei, 2006).

Expanding on this idea, Deci and Ryan (2013) differentiate between intrinsic and extrinsic motivation, whilst suggesting that there are three main psychological needs that motivate an individual; universal, innate and psychological, all of which include the need for competent autonomy and relatedness. It has been argued that these needs are required to satisfy and uphold psychological health and individual well-being, overall, the self-determination theory offers distinct differences between the different types of motivation and the underlying consequences (Deci and Ryan, 2017).

Self-determination theory has been critiqued by suggesting that free will has not been taken into account, likewise, proposing three psychological needs while other have proposed more needs in particular Marlow, with the hierarchy of needs (Fairclough, 2014).

3.4 Language and Emotion

Investigation has begun into how our emotional experiences become transformed into language, these ideas which trend from different areas including; cognitive, linguistics and anthropology (Divitz, 2016), all of which make differing assumptions about the link between emotion and language (Lindquist, Satpute, and Gendron, 2015).

There are two main ideas about the link of emotion and language. In accordance with the conceptual act theory, it is suggested that language plays a role in emotion as it is used to help understand the surrounding environment in given context (Schuller and Batliner, 2013). Other ideas suggest that language and emotion work alongside each other with each impacting the performance of the other (Fox, 2008).

Overall, there is significant differences in the way in which affective factors influence learning a foreign language between students who are beginning to learn a second language and those who already had began (Henter, 2014). However, although an individual’s performance is derived from intrinsic and extrinsic motivation, there are major differences between those that are motivated intrinsically or extrinsically regarding language development. It is suggested that those that are intrinsically motivated are more susceptible to knowledge, and hence achieve a higher level of education, whereas learners that are externally motivated may face a greater risk of underperforming (Lei, 2010).

Chapter Four

This chapter shall be discussing the importance of social context alongside the links between different cultures and the diversity of societies’ motivation when learning a second language.

4.1 Second Culture Acquisition

Since society influences both attitude and motivation, these are aspects which are necessary when learning a second language (Charmorro-Premuzic, 2011). The concept of society itself is an aggregate of people involved in persistent social interaction while sharing cultural beliefs, prospects and language. It is suggested that society itself that designs and shapes our expectations through both contemporary sociological theories and post-modernist ideas (Stevenson, 2010).

Furthermore, Durkheim (2003) argues that society confronts us as an objective fact encompassing our entire lives and shaping our expectations, however, that society is external to ourselves with the differences in language showing us the variances in culture.

Second culture acquisition is the process of creating shared meaning between cultural representatives, continuing over years of language learning and penetrates deeply into the individual's patterns of thinking, feeling and acting (Goldstein and Naglieri, 2011).

There are four main stages of culture acquisition, (Brown, 1980) the first being a period of excitement with everything being new and fascinating. Next is the culture shock period, the third known as anomie, a long period of social uncertainty and acceptance.

Once acceptance has taken place, the individual can progress to the fourth stage recovery, otherwise known as assimilation or self confidence in the new person. The most vital component of the stages is the feeling of anomie, the moment where the individual has a feeling of being between cultures but not yet a member of either, the individual will perceive a social distance between the individual and both cultures (Brown, 1980).

In contrast, unlike the stages of culture acquisition, the Optimal Distance Model suggests that age and accompanying changes in the brain are what place a limit on second language acquisition (Brown, 2007). This hypothesis fails to give an insight into how individuals learn language, instead proposing an explanation for the most desirable conditions in which to learn a language (Doughty and Long, 2003).

Contrastingly, the fourfold model consists of four models of acculturation that discusses the cultural and psychological change that results from learning a new language, in addition to referring to the changes that occur as a result of intercultural contact (Sam and Berry, 2010).

Assimilation, which involves the willingness to share cultural identity with those whose language they are learning alongside the cultural identity of themselves, leads to the new community feeling they can accept the individual completely. Integration implicates the aspiration to become a member of society, the one that they originate from, in addition to the culture they are aspiring to be a member of. Rejection requires the individual to be able to separate themselves from the majority community so that they can continue to accept the new culture and community they seek to integrate within.

Finally, de-acculturation is the loss of identity when the individual begins to distance themselves from their community and marginalisation (Cook and Singleton, 2014). It is further suggested that an individual may differ between various stages, for instance, an individual may reject certain values and social norms in private while adapting to the dominant culture in public (Arendt-Toth and Van de Vijver, 2004). Culture is seen as vital to fulfil particular biological and psychological needs in people; language is a part of culture and culture is a part of language, with the two not being able to be separated without losing the significance of the other (Jackson, 2013).

4.2 Society and Culture

Bourdieu views language as not only a form of communication but as a form of power, used to designate an individual’s position within society through material representations which language provides (Bourdieu, Nice and Bennett, 2010). The use of different dialects within an area of society can represent a varied social status for individuals, with Bourdieu (2014) arguing that capital formed the foundation of social life and hence dictates an individual’s position within society despite being a major source of inequality. As a social relation within a system of exchange, cultural capital includes the knowledge that confers with social status and power, certain forms of cultural capital occur including, embodied, objectified and established (Grenfell, 2011).

4.3 Socialisation

Linguistic anthropology studies how language can influence the social life, exploring how language shapes communication and forms social identity groups (Senhas and Stanlaw, 2001). From this idea, it is suggested that through socialisation both children and immigrants or outsiders are able to become part of the surrounding community (Keenan, 2014). The usage based theory surrounds the idea of socialisation and suggests this is how children initially build up their language; the theory intended to explain how individuals learn the norms and beliefs of our society. It is argued that our earliest experiences make us aware of societal values and expectations (Spybey, 1995).

Moreover, Tomasello (2005) suggests that children take their surroundings and use them to gain language experiences, over time becoming more academic and intellectual, particularly at the age of 3-4 years old as they continue to use recurring sequences.

4.4 Communication Technology

Through key events such as the freedom of trade and the improvement of communication, technology and the internet has allowed greater communication between people in different cultures and societies, resulting in globalisation (King, 1990). In recent years, linguists are claiming that over time a 'Global English' is bound to emerge to help facilitate communication on a worldwide scale, this could lead to the extinction of languages just as it has been previously observed in both North America and Australia (Coupland, 2012).

4.5 Globalisation

According to Luttermann (2014), human culture evolves in response to both extrinsic and intrinsic factors therefore, as a result of globalisation and other variables such as knowledge and wealth, globalisation can be dangerous for national local or endangered languages. In contrast, research argues that a language is known because of the works of academics or its association with religion or culture, it is argued that a language is in fact shaped by traders and marketing agencies, otherwise known as political power through this the language becomes seen as more desirable (Crystal, 2014). However, it could be argued that the role that media plays in language development is encouraging individuals in differing societies to learn a second language to be able to access media, thus encouraging a bilingual situation (Cormack and Hourigan, 2007).

Different forms of mass media such as film digital media and advertising frequently have to appeal to a wide array of consumers on a global scale. Language therefore becomes an important factor in their production as the target group may include many different cultures, meaning choosing the appropriate language is integral (Plappert, 2010). New communication technologies have enabled it so that distance is no longer an issue. However, language remains a predicament as many individuals learning the required language are encouraged to master a new language whilst changing the conditions in which language learning and development take place (Block, 2006). It has been argued that the domain of English is fundamentally vital for individuals wanting to progress through society and experience new cultures which in turn strengthens the English language on a global scale (Correa and Almeida, 2016).

In accordance with this, a recent study by Rata (2013), observed how Arabic students relate to the English language, the findings found that the mains reasons for learning English are instrumental as it is essential as both the universal language and the main language of tourism.

Linking closely to the previous research within chapter three (Gardener, 2010), this observation is further supported by the idea of instrumental motivation with the motivational reasoning linked to the knowledge that by learning English the Arabic students would gain a cultural enrichment through literature and poetry. However, findings also concluded that while English could be regarded an international language, this is not conclusive to Arabic countries as religious tourism is of immense value and results in an integrative connection to the Arabic world which the English language doesn’t contribute towards (Rata, 2013).

Countries such as The Netherlands, Japan or Belgium speak English daily for both work in politics, trade and tourism, therefore requiring English for a specific purpose rather than trying to integrate individuals into an English-speaking culture (Pennycook, 2014). From this it could argued that as many individuals are under the informal understanding that they are living in a country where English is required, it could be considered a social norm to have the capability to speak English (Rimal and Lapinski, 2015).

In recent years, countries such as Pakistan, Nigeria and Rwanda have seen what are considered by surrounding society as advantages from being able to speak English in addition to their mother tongue; as it has provided them the ability to communicate in the business world, hence repositioning themselves in the new global economy (Euromonitor International for the British Council, 2010).

Many countries implement the involvement of the English language through education, while giving individuals motivation to learn English as a second language, the concept of motivation through education shall be further discussed in Chapter five (Juffs, 2007).

4.6 Economics and Language

Over the last 30 years with an increase of businesses such as tourism, chemical and automotive industries relying heavily on language skills, many countries have begun to recognise the correlation between multilingualism and economic success (Bel Habib, 2011). Many politicians argue that the UK needs a multilingual population to be able to ensure business and to acquire employment opportunities in the globalised world (CILT, 2007). While this may be the vision, the most recent census reported that only 8% of the population of Britain were able to speak another language other than English (ONS, 2012). However, many have criticised the census due to the phrasing of the question, resulting in the idea that many households may have under reported their languages capabilities (Matris, 2014).

It is argued that many learn a second language within England to link back to their heritage or because of a community they may have been raised within, rather than learning a second language for the benefit of society or to help further themselves (Atkinson, 2014).

From analysing the influence that language has on individuals there has been a recent surge and, interest in bilingualism leading to new research, by joining the research together it allows society to explore many different situations (Appel & Muysken, 2006).

In accordance with this, ensuring that language needs are responded to effectively and efficiently is vital for social advances, in particular, public health and court procedures where the misuse of tenses from the translation provided may lead to discrepancies or a misunderstanding due to restricted access (Corsellis, 2001). The Socio-cultural perspective is a recent theory based on the works of Vygotsky, exploring the important contributions that society can make to an individual’s personal development and cognition (Lantolf and thorne, 2006). The theory argues that human learning is mainly revolved around society and is based on the interactions between individuals and the culture in which they participate (Swain, Kinnear and Steinman, 2015). The effects of globalisation which work to linguistic and cultural homogenisation is acquired through modernisation, translation and standardisation (Yaghobi, 2005).

Overall, research shows that there is a link between different societies and their motivation of SLA. Within the UK, individuals learn English for instrumental reasons and to integrate themselves into a culture, whereas surrounding countries use the English language as a tool and so are interactively motivated to develop the language skills required to gain intercultural relations (Ushioda, 2010).

Furthermore, communities that are involved in sharing language skills are able to help support their society build social cohesion, in turn creating a stronger and more diversely accepted culture (Hemon, 2011). This links closely to the idea that individuals shall continue to rely on society as it is here that an individual is surrounded by culture learning social norms which allows them to succeed within society (Crawford and Novak, 2014). According to Berger (2002), society not only controls our movements but shapes our identity, our thoughts and our emotions; over time the structure and formations of society form and develop as part of the individuals own consciousness.

Chapter Five

This chapter aims to explore how the educational system in Britain encompasses SLA, referring to the process and practice of acquiring a second or foreign language, while considering societies view on involving language within the education system.

The importance of being able to communicate efficiently is viewed as a necessary result of the educational process, language playing an important role in the transmission of culture (Schulz, 2008). Increasing globalisation has led to international awareness and international communication resulting in a need for individuals who can communicate in multiple languages (Bel Habib, 2011). This has led to the introduction of language education, a relatively new concept, emerging from the research of second language acquisition, focusing on both the societal and individual obstacles in languages while considering the politics surrounding language minorities (Baker, 2011).

5.1 Development of SLA

It is argued that there are two ways in which individuals develop SLA, through obtaining a second language at a young age either at home, through social interaction, play and without much academic input, otherwise known as simultaneous second language learning; individuals are able to simultaneously learn two languages alongside each other (Hoff et al., 2011).

In contrast, individuals who may become bilingual after the native language is developed, rather than from birth or during early years, are referred to as sequential bilinguals, which will require different learning strategies to successfully achieve SLA (MacLeod et al., 2012).

In addition, further research by Siraj-Blatchford (2007) enforces how young learners have better chances of gaining native-like pronunciation in the second language if they are exposed at a young age, leading to the idea that the young learners are more inclined to take risks with learning.

This is based on previous research that argued that 'Young children don't have to learn as much fluidity as adults and the vocabulary they need is a lot smaller so therefore it is easier and less stressful when learning a foreign language’ (Siraj-Blatchford,2000). Cohen (2011) discusses how the motivations differ for individuals living in various societies.

5.2 Teacher and Learner Relationship

If SLA is classroom based, unless the individual is also motivated instrumentally or outside of the classroom, they may struggle to gain the language skills. It also relates closely to the learner’s resistance as the individual may feel that the material being presented is of no use to them and irrelevant to their needs as so overall, they may not take the task seriously (Cohen, 2011).

Language learning in the classroom includes the ideology that the teacher can create context for communication which offers the opportunity for acquisition (Benson, 2011), both the teacher and learner of a second language need to comprehend and recognise the cultural differences that separate them. From this both must endeavor to teach one another identities in terms of their sociocultural backgrounds (Salzmann, Stanlaw, and Adachi, 2011).

5.3 English Education System with Regards to Languages

The national curriculum (2013) states that at KS1 and KS2 the core subjects are English, Mathematics and Science, with a foreign language being placed within the foundation subjects. In 2013 after a review of the national curriculum, computing has taken priority over modern foreign languages, presently language teaching is not compulsory until KS3 where the average teaching consists of two hours a week (National curriculum, 2013, p.7).

There has been a steady decline in the number of individuals choosing to take modern foreign languages at GCSE level, which critics claim the decline can be traced back to a decision to make languages optional for 14-year-olds in England for the first time in 2004 (SCILT, 2010). It has been argued that modern foreign languages within schools are very exam driven, with teachers only able to teach within the exam format rather than language skills that would be needed in daily life (Stinson and Winston, 2016).

Wales as a nation reinforces learning modern foreign languages, the Welsh language has an official status and all public sectors are required by law to deliver all legalities in both Welsh and English meaning there is a demand for the language (Mac Giolla, 2016). Therefore, in contrast to England all pupils in Wales are required to learn Welsh from reception up to GCSE. Despite this, there is still a lack of Welsh speaking teachers and many are leaving school without good Welsh language skills (Gould and Riordan, 2010).

5.4 Worldwide Education System with Regards to Languages

Throughout Europe bilingual education is helping to integrate immigrant children while promoting bilingualism throughout the rest of the community (Mateus, 2014). Siraj-Blatchford (2000) argues that children who have begun their development in a language other than their native tongue should continue this development within their early childhood. Blakemore and Frith (2005) suggest that learning grammar in a foreign language after the age of 13 is much more difficult, continuing to argue that children are notable to grasp the basics at a young age in comparison to when they begin high school and don't have the social stress alongside the academic stress associated with learning a foreign language.

Certain countries within Europe have more than one official language, exemplifying Luxembourg having three official languages with the majority of pupils receiving a trilingual education. The key language begins at primary school with Luxembourgish, before changing to German while touching on French, however, when at secondary school with the main languages prevail as French as well as English being introduced as a core subject (Kiijarvi, 2006).

It has been argued that due to individuals having already learnt a second or third language, they have gained the required mindset to enable themselves to pick up a third or even fourth language by the age of 11 (Ragnarsdottir, 2016).

Similarly, Belgium has three national languages depending on the region, with the country being divided in to linguistic area. The capital of Brussels is bilingual with legalities and general amenities offered in both Dutch and French, therefore during education the focus of the second language is either French or Dutch, depending on the region at which they are based (Bhatia and Ritchie, 2012).

According to GAO (2010) China has been promoting the extreme importance of learning a second language, in particular English as it will help promote internationalism. During the 2008 Beijing Olympic Games, it provided a chance for society to speak English to tourists. Many Chinese businesses are making it a requirement for employment meaning, that many graduates and individuals are learning English to have a chance at a job in a society of a billion people (Rai and Deng, 2014). Within Europe it is seen as essential to ensure that citizens learn a second language so that they can travel and learn freely throughout; recent statistics state that 'Over 70% of the world’s population speaks more than one language' (Siraj-Blatchford, 2000, p. 28).

Many concerns have been raised that individuals within British society lack SLA, research analysing that the fall in language skills could lead to a decline in Britain’s ability to compete in the global market. Language matters (2009) is a report that demonstrates the effect of the fall in modern foreign languages being cultured, despite this many British individuals do not see the need or obtain the motivation to learn a second language (British Academy, 2009).

5.5 Societal Power

Overall, we are able to observe that societal power has a great influence on the surrounding educational structures. Although society and education are two separate influences, together they have an impact on the individual and as a result, influence society as a -whole (Biesta, 2013). Society is able to influence education both negatively and positively, many educational opportunities arising from the positive impacts identified progressively in education, this can be used to motivate individuals to acquire SLA (Mackey, 2014).

Likewise, through society identifying the advantages of bilingualism in the surrounding environment and involving teachers who share societies’ motivation to develop SLA, this will result in students having an increased attention and personal interests regarding learning a second language (Cohen, 2011).

Conclusion

From examining and comparing the roles and effects of learning a second language, this dissertation has taken into account various factors and influences while considering the benefits and advantages. There are many individuals that are in favour or oppose the idea of bilingual education, however, research has revealed that there are many advantages to both the individuals and society (Pelham and Abrams, 2014).

As a result of globalisation and cultural interrelations, exposure to multiple languages is a regular occurrence, leading to the promotion of bilingualism within society for both personal and social advances (Lo Bianco, 2010). Bilingualism is a resource and as a result of globalisation there is a need for bilinguals within British society, however many employers recruit bilinguals from abroad to meet these needs (Horii, 2015). The value of second languages taught within the educational system is not addressed with other subjects taking priority over modern foreign languages, leading to children developing without a solid foundation of SLA (Fairclough, 2014).

Through the development of SLA, the theoretical basis has created a foundation from which linguistics can advance while investigation can commence on the circumstances that will lead to successful SLA (Ellis, 2015). At current the role of the involvement of the learning focus is gradually becoming of interest to academics.

Throughout this dissertation, research has shown that much of bilingualism is linked to motivation. Overall it has been concluded that to obtain successful SLA, the individual must experience motivation in the informal environment through both community and surrounding role models (Gardener, 2010). Motivation has been demonstrated through many different sources including the enabling of communication with differing cultures in addition to the opportunities presented from intercultural relations (Richards and Schmidt, 2013).

This dissertation also highlights the importance of individuality and the idea that no human being learns or develops in the same way, instead, every individual has similarities that relate to one another. This idea links closely to behaviorism, which emphasises the role that the environment has on an individual’s behaviour (Filmore, Kempler and Wang, 2014). Many biological and neurological advances provide a greater understanding of the link between bilingualism and the brain structure.

Neurological benefits showed that there is a correlation between bilingualism and the development of the Broca’s area which could be linked to the delay of Alzheimer’s and various psychiatric disorders including ADHD (Pikusa and Jonczyk, 2015).

Although further research needs to be completed, this dissertation highlights the impact that bilingualism has on the brain and how this influences the individual throughout life. With both languages constantly being active, an individual who is bilingual develops the advancement in inhibitory control at a much higher level than a monolingual (Marian, Shook, and Schroeder, 2013).

As a result of this many bilinguals children develop more flexible and diverse mental capabilities resulting in a heightened metalinguistic awareness and enhanced memory and creativity (Ilieva and Farah, 2013).

This dissertation was of great importance as it began to explore bilingualism and the influences that different variables can have on individuals successfully acquiring SLA.

Furthermore, this dissertation gives an insight as to why language learning may not be as successful in Britain in comparison to surrounding countries. Linking closely to Gardeners (2010) theory of motivation, British citizens may not feel that there is a demand or need to learn a second language, as a result of globalisation English is often referred to as a ‘Global language’.

From this idea, it could be argued that learning a language within Britain is not as rewarding in comparison to other countries, with no extrinsic motivation from society learning a second language is not seen as a necessity within Britain (Noels et al., 2003). Instead the rewards of learning a language correspond to the personal goals and cognitive advantages. Therefore the individual must obtain integrative motivation to be successful, which once pursued it will benefit them and as it was their choice this will lead to a greater sense of freedom and self-determination (Filmore, Kempler and Wang, 2014).

Many theories with regards to SLA date back to the idea that the ability to able to recognise critical and social issues are vital to certain individuals as it gives us a greater comprehension as to why and how individuals learning SLA both succeed and fail (Larsen-Freeman and Long, 2014). By learning a second language, it enables the learner to communicate with people they otherwise would have not been able to, opening the doors to other cultures and helping the learner to understand and appreciate the people within them (Schmidt, 2014).

While the research within this dissertation draws upon an extensive range of academic sources and research, this dissertation has shown that there are major gaps with regards to neurological understanding of how the brain truly processes and develops information.

Likewise, research needs to be undergone to understand the link between the Broca’s area and psychiatric disorders and how they integrate with one another. Negative attitudes are created from a lack of motivation, however, there is yet research to be conducted into the lack of motivation for British individuals and why the education system removed the encouragement of studying a second language specifically during the critical period (Smith and Mackie, 2007). These areas of interest can be assumed through corresponding research, however, until further investigation the gaps in knowledge shall remain.

Finally, while SLA research is extremely current with theorists and linguists laying down a foundation to understand and observe the process involved in learning a second language, alongside the internal and external variables that may contribute towards the development, there is much more work that remains to be done. Development is required between our knowledge of the human mind and scientific limitations to help us gain an understanding of the scientific processes (Altarriba and Heredia, 2011). Nevertheless, the progress made in the last few decades is phenomenal especially regarding psycholinguistics and the understanding of how motivation can help towards an individual’s learning, this allows us to continue to develop our understanding of ourselves as humans.

References

Abutalebi, J. and Rietbergen, M.J. (2014) “Neuroplasticity of the bilingual brain: Cognitive control and reserve,” Applied Psycholinguistics, 35(05), pp. 895–899. doi: 10.1017/s0142716414000186.

Alrabai, F. and Moskovsky, C. (2016) “The relationship between Learnerss Affective variables and Second language achievement,” SSRN Electronic Journal, 7. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.2814796.

Altarriba, J. and Heredia, R.R. (2011) An introduction to bilingualism: Principles and processes. 2nd edn. New York, NY [etc.]: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Antoniuo, M., Liang, E., Ettlinger, M. and Wong, P.C.M. (2014) “The bilingual advantage in phonetic learning,” Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 18(04), pp. 683–695. doi: 10.1017/s1366728914000777.

Appel, R. and Muysken, P. (2006) Language contact and Bilingualism (Amsterdam university press - Amsterdam archaeological studies). Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

Arends-Tóth, J. and van de Vijver, F.J.R. (2004) “Domains and dimensions in acculturation: Implicit theories of Turkish–Dutch,” International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 28(1), pp. 19–35. doi: 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2003.09.001.

Aron, A.R., Robbins, T.W. and Poldrack, R.A. (2014) “Right inferior frontal cortex: Addressing the rebuttals,” Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 8. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2014.00905.

Atkinson, J. (2014) Education, values and ethics in international heritage: Learning to respect. Aldershot, Hamps.: Ashgate Publishing.

Auer, P. (2014) Code-switching in conversation: Language, interaction and identity. London: Routledge.

Baker, C. (2011) Foundations of bilingual education and bilingualism. 5th edn. Bristol, UK: Multilingual Matters.

Barac, R. & Bialystok, E. (2012). Bilingual Effects on Cognitive and Linguistic Development: Role of Language, Cultural Background, and Education. Child Development.

Beck, C. (2014) Bilingualism, executive function and attention deficit/ hyperactive disorder. Southern Illinois : OpenSIUC.

Bel Habib, I. (2011) “Multilingual Skills provide Export Benefits and Better Access to New Emerging Markets,” Sens-Public, .