Changing Nature of the Silhouette in 18th to 19th Century Art

Info: 7672 words (31 pages) Dissertation

Published: 17th Nov 2021

Tagged: Arts

Abstract

This dissertation will explore the changing nature of the silhouette during the late 18th to early 19th century. It will discuss how the silhouette stood as a precursor to photography and demonstrate how the art form reflects the social ideas of extravagance or modesty. Through exploring this development, it will look at how different social groups utilised silhouettes as an accessible form of portraiture and discuss the silhouette from its simplest form to the latter development of the ornate and grotesque. It will investigate the ways in which the silhouette has changed in terms of use and how this reflects social and class distinctions.

To do this my research plots this change through its initial use as a ‘pure’ form of portraiture, its expansion through mass production to the lower classes, development into a grotesque of its origins through embellishment and latterly its use in contemporary art today. It will consider how the silhouette was utilised as an accessible form of portraiture and how its use reflected social and class ideals of extravagance and modesty. Considering the silhouettes development alongside the class theories of Simmel, Bourdieu and Veblen, it will comment on how theories of taste and consumption underpinned key advances in the artform. Using initial historical analysis to anchor my research I will discuss further how it was able to articulate issues around class and culture and eventually race within its growth. I will consider this alongside relevant artefacts to further discuss how changes within the silhouettes evolution lie with theoretical exploration.

Contents

Abstract 1

Contents 2

Introduction 3

Chapter One 6

Chapter Two 9

Chapter Three 16

Conclusion 18

List of Figures 20

Figures Bibliography 25

Bibliography 27

Introduction

This dissertation will explore the historical narrative behind the silhouette and discuss its development in line with class theorists. It will look into how this development is an expression of social forces and how these forces have had an impact on artistic culture during the late 18th to early 19th century. Discussing how the silhouette stood as a precursor to photography this dissertation will demonstrate how the art form reflects the social ideas of extravagance or modesty. Through exploring this development, we can look at how different social groups utilised silhouettes as an accessible artform and its underlying commentary on social change. Evidence of social development can be read through our pictorial history, a populist artform such as the silhouette becoming the substantial embodiment of a slow incremental social change. Cultural artefacts such as the silhouette consequently can be considered an indicator of underlying social forces. We are therefore able to read into the development of society in terms of literacy, equality and rights through its production of cultural products.

The silhouette in its simple and ‘purest’ (Lavater, 1789) form eventually filtered down to the lower classes and ran in tandem alongside the latter ornate advances of the artform by the upper classes; as they attempted to prevent social equalization. This attempt allowed for the development of the silhouette to a more complicated, ornate medium which is arguably a grotesque of its early form. The introduction of the silhouette in its simplest form to the lower classes allowed for its decline in fashionable society and its rise toward the grotesque. Beginning to be associated with sub-standard mass production simple ‘shadow portraits’ (Rutherford, 2009 p.21) were coined ‘Silhouettes’ after Etienne de Silhouette. The French finance minister who was ridiculed for his sever tax modifications, his namesake becoming associated with all things inexpensive and austere.

Looking at a variety of historical and cultural artefacts which outline the growth of the silhouette we can see how these changes were influenced by historical, cultural and contemporary developments and theories. Seminal works that discuss the topic at length such as Emma Rutherford’s book Silhouette: The Art of the Shadow (2009) are integral for historical research into the silhouette. The book compiles the history and development of the silhouette into different forms throughout its history. Rutherford draws on a mass of surviving sources from Europe and America, accumulating a broad look at the form and its variants alongside informative text on the progression, materials and background of the processes. Although Rutherford’s research considers the social history behind the silhouette it cannot be said that the text makes any kind of social or theoretical commentary about the form itself. This text is a solid reference to the basic understanding of the topic and it will inform an analytical critique of the use of the silhouette, allowing a consideration to its place in the representation of society in the 18th and 19th centuries. The lack of social commentary within the literature surrounding silhouettes has prompted my exploration of a new avenue within the subject. The development of the form and its link to the social standing of the sitter has proven to be an inquiry which is little written about and therefore this investigation will look into how it effects the artform.

Alongside Rutherford’s key text my research will use primary sources from the Library of the Society of Friends (London) and secondary sources from the Victoria and Albert Museum to discuss a range of artists who employed the silhouette. Linking such works to social theorists it discusses how the products of society can be influenced by cultural and social forces. Using the ideas of Pierre Bourdieu (1984), Thorstein Veblen (1965) and Georg Simmel (1957) this investigation will look into how the silhouette began to extend itself to different classes to become a populist artform and how this powered the continuous reinvention of the silhouette toward the grotesque.

My research will attempt to plot how the silhouette is used historically and contemporarily though three chapters. Initially addressing the silhouette through historical analysis in the first chapter, discussing it as a historical entity. Chapter two will look at the silhouette as a cultural form and how the articulates issues around class and cultural structure effected its development, further relating this to class theory models. The last chapter will discuss the silhouettes place within the contemporary and its modern relevance today, being used as a tool to address issues around race and power.

Chapter 1

This chapter will explore the silhouette as a historical artefact, looking at the background behind the artform and the reasons behind its development.

Within the decade before photography the silhouette provided a quick and cheap medium of producing a person’s profile. Although often eagerly produced by amateurs, the process swiftly grew in popularity and professional silhouettests began to make a profit from the artform. The simplicity of the silhouette allows the viewers ideas to be easily projected onto it due to its general lack of content and therefore expression. This was perhaps the case behind the success of the work of Johann Casper Lavater’s Essays on Physiognomy (1789) which encouraged the sharp rise in prominence of the silhouette. Lavater’s now outdated theories combined aesthetic, theological and psychological models to form the idea that traits and internal qualities can be indicated by an individual’s external appearance, specifically the face and skull (Lavater, 1789). Lavater’s work initiated the trend in silhouettes as the traced profile was seen as the truest representation of facial features before photography in the late 18th and early 19th century, thus the truest documentation for use of physiognomy. Silhouettests advertising their work to have an ‘unequalled degree of accuracy as to retain the most animated resemblance and character’ (Artofmourning.com, 2014) encouraged their customers to distinguish inner traits from the appearance of the face alone through an ‘accurate’ representation of their profiles. The term ‘accuracy’ in regard to the silhouette refers to a truthful representation of the human profile for the use within physiognomy. The silhouette is limited in methods to truly note a sitter’s facial features for a factual representation of the face. Instead it draws on the contour lines of the sitter’s face from the side to capture a modest and truthful likeness of the subject’s profile. Therefore, the craft of creating the ‘accurate’ and restrained representation of the sitter though profile can be used predominantly within the physiognomic science of the measurement of the skull and facial features to determine intelligence, character and breeding.

The silhouette stood as the most ‘accurate’ from of physical representation in pre-photographic society. The profile of the sitter would be depicted quickly yet skilfully by an artist cutting blackened paper. This non-stylised and simple method moved away from the elaborate portraiture trends of latter periods and became an art of ‘accuracy’. As the demand for the form grew the development of machines were introduced to replace free hand cut work, supplying the need for cheaper and quicker results amongst less wealthy classes. This shift in its availability meant the silhouette moved away from the craftsmanship of the artist toward mass production. The art was accessible with only the ability to mechanically trace a person’s profile, allowing portraiture to move from a practice of higher skill and greater interpretation of the artist toward a mass producible form. With this change came the decline in the quality and status of the silhouette.

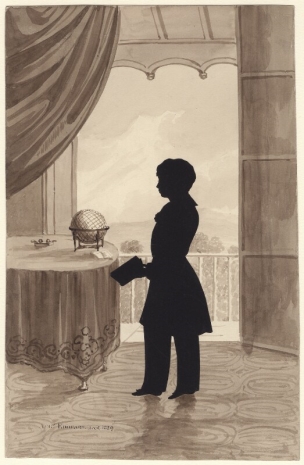

The initial development of the silhouette as a craft blossomed within the higher ranks of society; royals and the wealthy alike taking pleasure from its novel simplicity, accuracy and rapidity. The silhouette in its original form would be cut with scissors out of blackened paper and pasted on a contrasting white lithograph background. Although it was common to see a silhouette of the chest to head; proportions varied per artist, within renowned artist Augustin Edouart’s catalogues we see many examples of full body portraits which can even include painted backgrounds or scenery such as tables, stools or toys (Figure 1 and 2). The size of the silhouette always remained small and modest, the largest individual silhouette I have found within my research is no larger and an A4 piece of paper. These proportions tended to become smaller with the spread of the silhouette, smaller silhouettes tending to express higher skill levels of the artist thus dictating the wealth and prosperities of its owner. The widespread practice and popularity of the silhouette trickling down to lower class systems encouraged a large developed in its form. Machines which traced a sitter’s profile reduced the need for skilled artists and the silhouette became a cheap, mass producible and attainable method of individual representation. The wide availability of the silhouette allowed its status within the wealthier classes to be diminished. The idea behind the silhouette shifted from the novel depiction of the upper classes to the representation and documentation of the lower classes for the first time, allowing the social commentary behind the silhouette to change. This changed allowed the development of the silhouette as the upper classes attempted to reclaim the portraiture form and reassert its affluence and unattainability within social rankings. The silhouette therefore began to move away from the ‘scientific physiognomy’ of its origins and began to move toward the grotesque. Profiles began to be captured in drawings, glass work and jewellery with smaller details such as hair and clothing being defined in pencil or through bronzing. The silhouette no longer sitting at its modest roots was allowed to develop to assert the lavish and therefore superior lifestyle of the upper-class system.

It is important to consider that although social change is influential to the development of cultural forms such as the silhouette it is not the only force at play. Just as every artform evolves through time the silhouettes progression toward the grotesque is not only due to social change but also through development of artistic expression. The skill of the artist naturally evolves to fit new markets with the introduction of new materials and skills available. Art trends can have their own internal forces which power their development, when these new materials and skills become available the form in its newest shape can begin to become popularised. In short, we can note that although we are considering the development of the silhouette through social change we must also bare in mind that it is not solely these forces which dictate its evolution. Therefore, the market of the silhouette evolves in order to differentiate itself from its populist forms alongside material and artistic forces.

Chapter 2

In the previous chapter I have undertaken the historical background of the silhouette and its development to the grotesque, within this chapter I will analyse why this is the case looking at the silhouette as a cultural form in line with social theories.

The development of the silhouette lies alongside class tensions and the unspoken rank of social hierarchy. These elements relate to Georg Simmel’s ‘Trickle Down’ theory. The theory states that the upper classes dictate fashions in material goods and these trends ‘trickle’ down to the middle and lower classes. When the fashion reaches lower class levels the style is no longer en vogue within the upper-class community and they therefore change the fashion to re-establish social hierarchy. When the silhouette progressed into an accessible and individualised yet mass produced form amongst the lower classes the style became obsolete to its original audience who reinvented it to become the grotesque to its modest predecessor. This fashion cycle simultaneously unites and isolates social classes from one another, whereby the fashions function as social imitation and attempt equalization before they are reprocessed to render the latter outdated. ‘fashion, as noted above, is a product of class distinction… the double function of which consists in revolving within a given circle and at the same time emphasizing it as separate from others’ (Simmel 1957, p.544) This leads us to believe that trends within society are a social creation which serves as an identification of taste and therefore class. As the lower classes embraced art as a form of representation, a method formerly reflecting the education and status of higher class levels, it became apparent that previously preserved elitist forms were becoming more easily accessible to the lower classes. Cultural products of society such as the silhouette could therefore be read as a sign of the evolution of the social forces at play. This evolution toward the lower classes allows for a retaliation within the upper classes to re-establish themselves as elitist. Reverting to Simmel’s ‘Trickle down’ theory this therefore explains the development of the silhouette to forms of jewellery, painting and pottery as the higher classes regenerate the artform to define their superior tastes. The silhouette began to move away from the simple ‘accurate’ depiction of the sitter’s profile to depict costume, hair and even define facial features concluding in a romanticised and vain representation of a person’s profile thus reasserting a luxurious and unattainable quality to the artwork.

Such artworks became popular from the 1780’s to the 1820’s. Miniature shadow portraits set in jewels followed the neoclassical trend to capture ones ‘self’ in sentimental keepsakes. Artist John Miers and his partner John Field seemed to head up the supply of miniature shades in jewellery within the period; with many of the surviving works signed by the pair. Miers being skilled at prolific works created flawless two to three-inch representations of the sitter on rings, brooches and pins. Advertising their work, they publicised:

‘Profile Likenesses in a superior style of elegance and with that unequalled degree of accuracy as to retain the most animated resemblance and character, given in the minute sizes of Rings, Brooches, Lockets, etc. (Time of Sitting not exceeding five minutes.) Messrs. Miers & Field preserve all the original shades by which they can at any period furnish copies without the necessity of sitting again.’ (Artofmourning.com, 2014)

Looking at an example by Miers at the Victoria and Albert Museum we can see the painted watercolour silhouette of a woman on ivory, set into a trinket box lid (Figure 3). The box itself is only of approximately two to three inches in length, with the shade being considerably smaller set in the middle. The size of the portrait draws the viewer in to observe it in more detail making the portrait a more intimate element. The profile of the sitter is defined only by the black outline of the silhouette with no embellishment to romanticise or flatter features. The figure is full with thin pursed lips and a rounded chin which reflect the age of the sitter. This is further depicted through the wispy lines of the hair and the loose, imperfect hairline. Although this example of a grotesque silhouette is not elaborate in a sense of the shades detail, its framing, materials and overall aesthetic is much richer in time and cost and therefore aims to express the status or perhaps wealth of its owner further than that of the simple cut silhouette.

Much like the work of Simmel, sociologist Pierre Bourdieu’s theory on taste states that the upper classes dictate trends in material matter which the lower classes then adopt in cheaper forms. Within Bourdieu’s model he defines ‘taste’ as the factor which outlines a person’s class, assuming that the subject’s wealth, prosperity and rank are reflected in what they choose to surround themselves with. ‘immediate adherence…to the tastes and distastes, sympathies and aversions, fantasies and phobias, which more than declared opinions, forges the unconscious unity of a class’ (Bourdieu 1984, p.77) The process of cultural cachet being rendered to products, goods and behaviour tends to be a circular phenomenon. The appropriation and re-appropriation of goods which have been deemed unfashionable allow for the opportunity within the cognoscenti to re-establish elitism through the revival of unfavourable goods. These goods therefore become of greater value because the elite have asserted their interest back into it. Its new value carries with it its earlier rejection which defines its elitist adoptees with a higher level of refinement to its previous rejecters.

This seems to be true within fashions in art. Taking the silhouette as our main example we can see that it began as portraiture for the upper classes. As the artform moved its way down to the lower classes the method becomes outdated and unfashionable and no longer to the tastes of the elite. The silhouette is then reinvented to re-establish itself as a reflection of the tastes of the upper classes. As portraiture becomes more accessible through the development of the silhouette the connotation behind it shifts. Art had often been associated with the leading classes and the understanding and appreciation of said art was seen as a reflection of education, culture and status. As the silhouette ‘trickled down’ to the lower classes the portrait, and therefore art, was no longer reserved for the well-read. This began to equalise class ‘taste’ and therefore pushed the silhouette in its original form to be rejected from higher classes to reinstate taste hierarchy. Again, this theory underpins the advance of the silhouette to the grotesque as the higher classes reinvent the artform to become more affluent and unattainable, a manifestation of a superior taste.

The movement of the silhouette from the ‘pure’ to the grotesque asserts the thought of aristocratic taste further through flaunting obvious consumption. Thorstein Veblen’s theory of ‘conspicuous consumption’ expressed the need of the leisure class to display economic wealth through illustrious goods. The development of the silhouette allowed it to be lent to luxury objects such as rings, bracelets and trinket boxes. This movement toward the grotesque testified obvious waste through the consumption of more expensive and less versatile materials, thus expelling the silhouettes previous simple form and transferring it to a more complicated execution. By snubbing the original modesty and novelty of the silhouette and transferring it to such grotesque forms the higher classes demonstrate leisure and consumption. This therefore reinstates power above lower classes who had adopted the original fashion they set. ‘Conspicuous consumption of valuable goods is a means of reputability to the gentleman of leisure’ (Veblen 1965, p.64) The depiction of a person’s silhouette on these less attainable materials, such as ivory flaunted the use of tricky and therefore more expensive techniques. Furthermore, the smaller scale of the portrait when expressed on jewellery required a certain level of skill, one not as freely available to the uninfluential, which in turn reflects the wealth of the person commissioning the portrait. This movement from the silhouette at its ‘purest’ form to its exaggerated grotesque displays an unconcealed demonstration of consumption; which in theory establishes a social order.

A second example from the V&A is a metal bracelet by Field containing a bronzed watercolour silhouette on ivory, sitting central within bracelet straps which have been finely woven or plaited with hair (Figure 4). This silhouette is an example of the progression of the artform to the grotesque. In this later evolution of the silhouette we can see garments and hair began to be defined more prominently in the profiles in shades of brown, commonly known as bronzing. Within this profile care has been taken to exaggerate the small amount of hair on the sitter’s head, perhaps being of importance to the subject showing vanity and thus expression of consumption and hierarchy.

Within these grotesque versions the miniature profiles of the sitters are kept true to silhouette form with strong solid shadow outlines of side facial features. However, alongside the natural evolution of an artwork, the progression of expenditure to define consumption and thus class comes with the attention to the finer details. The details on these examples, namely hair and garment definition, achieved on such a complex material as ivory set a precedent for the owner’s wealth through display of ‘conspicuous consumption’. In these cases, we must also consider the setting in which the silhouettes are placed. The placement of the profiles into the bracelet and trinket box suggests a need for the silhouette to be openly displayed, again presenting the progression of the silhouette from its modest beginnings to the grotesque as it is commissioned and exhibited to boast wealth, taste and social rank.

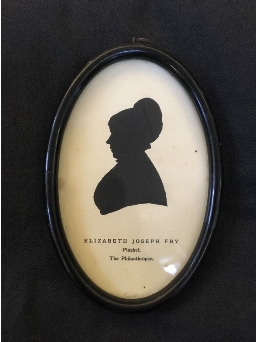

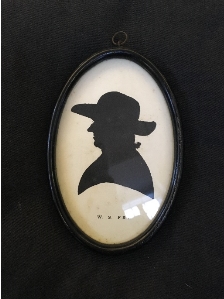

As opposition to the latter argument of how social inclinations encouraged the development of the silhouette it was interesting to research into the use of the silhouette within the American Quaker community. The Quakers adopted the silhouette as their only form of portraiture due to the belief it was one of the most ‘accurate’ depictions of one’s physical appearance. ‘Accuracy’ in this case defined by the idea that the silhouette was a simple and unadorned trace of profile likeness, one uninfluenced by the artists inclination to present a fashionable, perhaps flattering, version of the sitter. The silhouette, sitting in line with Quaker beliefs, was the only accepted form of portraiture for the group who were defined by their plainness of speech, behaviour and apparel. Quakers cautioned often of the vain fashions of the world. ‘A novelty in dress is first regarded as objectionable, then it is admitted and not considered inconsistent; and lastly, when the rest of men have passed away from it, it is clung to with all devotion which our society entertains for its peculiar customs’ (Fry, 1859 cited in Laughon, Laughon and Edouart, 1987)

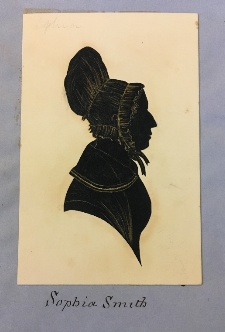

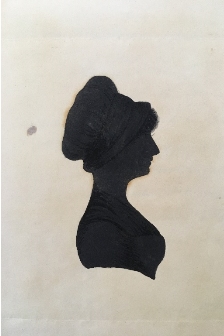

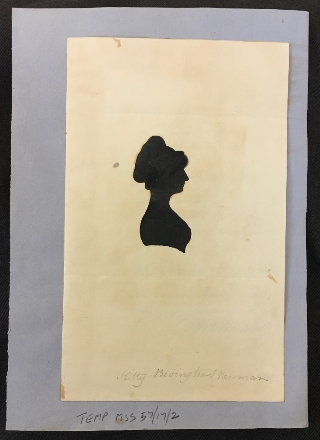

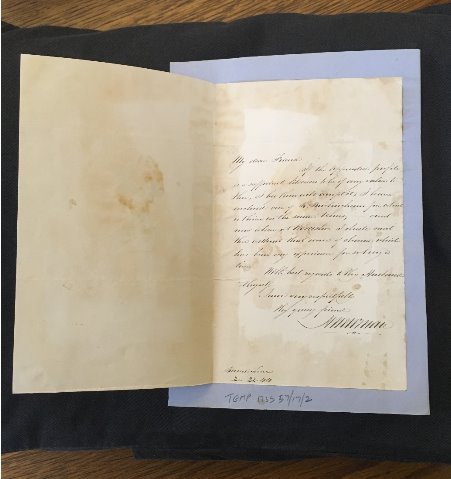

Of the many primary sources observed at The Library of the Society of Friends (London) (Figure 5, 6 and 7) one silhouette of a woman stands out. Much like many of the silhouettes archived by the library the silhouette exists as part of a postal correspondence meant as a keepsake for a loved one. This factor demonstrates the meaning and modesty of the silhouette within the Quaker community. The silhouette was seen as a personal item with great familial meaning. This example, a portrait of a Quaker woman noted ‘Kitty Bevington (Newman)’, is a simple black cut silhouette of the sitters head neck and bust (Figure 8,9 and 10). Measuring only approximately three inches the portrait is small yet holds precise detail. The silhouette itself sits in the middle of the front of the folded letter and is the only component to the first sight of its consumer. Its size within the A5 folded sheet is not boastful or unsightly but again depicts the modesty and humbleness of the Quaker community. Interestingly in this form small details of the sitter’s garments are depicted through the working of a dark pencil or paint to create a subtle drape in fabrics and hair. These added details define garment structure but do not depict any features of the face, this is instead defended by a strict cut contour line, only broken by the pencil work of eyelashes and hair on the forehead.

This style of portrait being adopted by the Quakers in its ‘purest’ form allows us to see an opposition to art and fashions in relation to social and class structure. We can deduce that it is only when a new society is formed that actively choose to reject these structures, that an artform such as the silhouette can remain at its ‘purest’ state. When groups, such as the Quakers, no longer use fashions to dictate hierarchy, economic wealth and status, modes no longer lie within a catalyst to develop into the grotesque. The Quakers adoption of the silhouette after the movement has renounce to photography allows the form to no longer dictate taste and vogues but instead reflect the simplicity of manner and dress within the Quaker community, their values perfectly suited to sustaining the silhouette in its earliest form.

From these examples alongside class theories we can deduce that fashions within art become devalued by their entry into the working class, this only being opposed within communities which ignore the social norms of society. Instances such as the silhouette demonstrate how modes which are seen as defined, rare and aristocratic can ‘trickle down’ to the lower classes through the development of fast manufacturing and production of imitations. This allows the form to move away from exclusive craftsmanship and therefore affluent consumption and taste to cheap and mass-produced by-products. This process within social structure dictates the development of many forms, moving them away from their ‘purest’ origins and deforming them into the grotesque.

Chapter 3

Although scarcely used in its original method the silhouette still inspires modern artists who use it as a tool to openly comment on social tensions. Contemporary artist Kara Walker is noted to use a modern silhouette form to distinguish her work and express a social commentary on race and class structure (Figure 11 and 12) . Walkers placement of the silhouette into history painting allows her to use the medium for story telling through stereotypical figures, which she claims, ‘says a lot with very little information’ (Walker cited in The Art Story, n.d.). As discussed previously Walker has developed the silhouette form through artistic and material growth. Walker has been playful with the artform developing a new artistic interpretation to comment openly on social forces. Walker comments on slavery, aristocracy and social inconsistencies through exaggerated figures which adorn cliché ideas of social presence, dress, order and emotion. The potential for the silhouette to de-stratify depictions of all classes quickly lead to the elaboration of its form. Here with Walker we see conversely simplicity of forms used to distinguish and illustrate social division. This contemporary use which serves to blatantly display social tensions formulates a new type of silhouette grotesque for a modern audience. Although stripped back to its original monochromatic 2D format the silhouettes in Walkers work act as a grotesque as they are embellished with stereotypical caricature. This stereotyping is allowed through the simplicity of the silhouettes form. The overall simplicity of the form leads to a lack of expression, this therefore leaves more scope for the form to be read into because the general content is limited. Walker takes advantage of how the viewer loads their own prejudices onto the simple imagery by exaggerating such prejudices or stereotypes within her work. This development again moves the silhouette away from its ‘purest’ form toward an exaggerated version which openly, and vividly, comments on issues of race and class to a modern audience. The silhouette is therefore no longer situated alongside portraiture but instead encourages a narrative to discuss cultural inequalities thus becoming a grotesque of its origins.

This development of the art of the silhouette has allowed us to see that the artform is still pertinent today. Although often shoehorned as an antiquated artform the silhouette has been revived through Walkers work and still carries with it a poignancy in relation to tensions in class and race. Ideals of taste and consumption theories are transferred to no longer be shown through the embellishment and ownership of the silhouette but instead through the narrative of the artist and how she chooses to depict the subjects of her work. The adoption of the silhouette within Walkers work again links to Bourdieu’s theories as the silhouette is still part of a cycle of appropriation of cultural products.

The revival of the silhouette by contemporary practitioners who are still using the form in an urgent manner explicitly expresses how social developments are still embodied in the development of the form today.

Conclusion

This dissertation has addressed the changing nature of the silhouette from a historical and theoretical perspective. Doing so by plotting this change through its initial use as a ‘pure’ form of portraiture, its expansion through mass production to the lower classes, development into a grotesque of its origins through embellishment and latterly its use in contemporary art today. Looking at how the silhouette was utilised as an accessible form of portraiture and how its use became a reflection of social and class ideals of extravagance and modesty. I examined this by considering the silhouettes development alongside the class theories of Simmel, Bourdieu and Veblen, commenting on how theories of taste and consumption underpinned key advances in the artform. Through initial historical analysis I was able to anchor my research into the silhouette as a historical entity allowing me to discuss further how it was able to articulate issues around class and culture and eventually race within its growth. I have been able to show that this is still a relevant art form that carries with it urgent questions about race, class and cultural identity. Additionally, to this my use of case studies allowed me to extend my research further as the discussed artefacts outlined the changes within the silhouettes evolution in line with my theoretical exploration.

Within this research dissertation I wished to discuss how social developments are embodied in the development of the silhouette form through the study of social and class theories. Although I have touched lightly on the subject limitations within the research format have caused restrictions. Further study would allow me to look deeper into an artform little written about. To investigate further I would discuss alternative forms of art in which you can notice the same social phenomenon of appropriation to refine my argument. Alongside this I would consider the enhancement of the silhouette toward the grotesque more closely to discuss technicalities such as materials, techniques and additional details of costume frippery which distinguish its grotesque nature. Furthermore, an analysis of the popularity of the form would be desired through investigation of catalogues of key artists or directories of shops to expand and anchor my research.

List of Figures

Figure 1. Silhouette of Hannah More (Edouart, 1826)

Figure 2. Silhouette of Alexander Hope (Edouart, 1829)

Figure 3. An Unknown woman (Miers, 1780)

Figure 4. Silhouette of an unknown man (Field, 1790)

Figure 5. Framed silhouette of Elizabeth Joseph Fry (Elizabeth Lee papers, 1751)

Figure 6. Silhouette of W. S. Fry (Elizabeth Lee papers, 1751)

Figure 7. Silhouette of Sophia Smith (Silhouettes, n.d.)

Figure 8. Silhouette of Kitty Bevington (Newman) (Silhouettes, n.d.)

Figure 9. Silhouette of Kitty Bevington (Newman) (Silhouettes, n.d.)

Figure 10. Silhouette of Kitty Bevington (Newman) Inside correspondence (Silhouettes, n.d.)

Figure 11. Gone: An Historical Romance of a Civil War as It Occurred Between the Dusky Thighs of One Young Negress and Her Heart (Walker, 1994)

Figure 12. The End of Uncle Tom and the Grand Allegorical Tableau of Eva in Heaven (Walker, 1995)

Figure Bibliography

Figure 1

Edouart, A. (1826). Hannah More. [Cut black paper with wash] London: National Portrait Gallery.

Figure 2

Edouart, A. (1829). Alexander Hope. [Silhouette] London: National Portrait Gallery.

Figure 3

Miers, J. (1780). An Unknown woman. [Watercolour on ivory] London: The Victoria and Albert Museum.

Figure 4

Field, J. (1790). Silhouette of an unknown man. [Watercolour on ivory set on a hair bracelet] London: The Victoria and Albert Museum.

Figure 5

Elizabeth Lee papers. (1751). [silhouettes, some framed, of members of the Fry family; (1/22) prints of Priscilla Hannah Fry, Mary Tylor and Earlham House; (1/23)] The Library of the Society of Friends, Manuscript Collection. London.

Figure 6

Elizabeth Lee papers. (1751). [silhouettes, some framed, of members of the Fry family; (1/22) prints of Priscilla Hannah Fry, Mary Tylor and Earlham House; (1/23)] The Library of the Society of Friends, Manuscript Collection. London.

Figure 7

Silhouettes. (n.d.). [This series consists of silhouettes of Frances Thompson, Kitty Bevington [later Newman], Candia Burlingham, Emily Fryer, Sophia Smith, Tabitha Barber, Henry Tuke, Lucy Burlingham of Lynn, Lichfield, Staffordshire, Arnee Frank, Alfred Fryer, Adey Bellamy, P Guin, Richard Burlingham, junior and Mary Pryor, with a colour miniature portrait of Ephraim Lingham. Wrapper addressed to “William Spriggs, Worcester [Worcestershire]”] The Library of the Society of Friends, Manuscript Collection. London.

Figure 8

Silhouettes. (n.d.). [This series consists of silhouettes of Frances Thompson, Kitty Bevington [later Newman], Candia Burlingham, Emily Fryer, Sophia Smith, Tabitha Barber, Henry Tuke, Lucy Burlingham of Lynn, Lichfield, Staffordshire, Arnee Frank, Alfred Fryer, Adey Bellamy, P Guin, Richard Burlingham, junior and Mary Pryor, with a colour miniature portrait of Ephraim Lingham. Wrapper addressed to “William Spriggs, Worcester [Worcestershire]”] The Library of the Society of Friends, Manuscript Collection. London.

Figure 9

Silhouettes. (n.d.). [This series consists of silhouettes of Frances Thompson, Kitty Bevington [later Newman], Candia Burlingham, Emily Fryer, Sophia Smith, Tabitha Barber, Henry Tuke, Lucy Burlingham of Lynn, Lichfield, Staffordshire, Arnee Frank, Alfred Fryer, Adey Bellamy, P Guin, Richard Burlingham, junior and Mary Pryor, with a colour miniature portrait of Ephraim Lingham. Wrapper addressed to “William Spriggs, Worcester [Worcestershire]”] The Library of the Society of Friends, Manuscript Collection. London.

Figure 10

Silhouettes. (n.d.). [This series consists of silhouettes of Frances Thompson, Kitty Bevington [later Newman], Candia Burlingham, Emily Fryer, Sophia Smith, Tabitha Barber, Henry Tuke, Lucy Burlingham of Lynn, Lichfield, Staffordshire, Arnee Frank, Alfred Fryer, Adey Bellamy, P Guin, Richard Burlingham, junior and Mary Pryor, with a colour miniature portrait of Ephraim Lingham. Wrapper addressed to “William Spriggs, Worcester [Worcestershire]”] The Library of the Society of Friends, Manuscript Collection. London.

Figure 11

Walker, K. (1994). Gone: An Historical Romance of a Civil War as It Occurred b’tween the Dusky Thighs of One Young Negress and Her Heart. [Cut paper on wall] New York: The Museum of Modern Art.

Figure 12

Walker, K. (1995). The End of Uncle Tom and the Grand Allegorical Tableau of Eva in Heaven. [Cut paper on wall] New York: Collection Jeffrey Deitch.

Bibliography

Archive Materials

Alice Mary Hodgkin papers. (1673). [Items collected by Alice Mary Hodgkin: a letter from Elizabeth Irton to George Fox (1673); a letter from John Hodgkin (22 March 1841); a print of Ury, home of Barclay the Apologist; a black and white photograph of an elderly man (1858) an outline for a silhouette believed to be David Barclay of Youngsbury] The Library of the Society of Friends, Manuscript Collection. London.

Daniel and Jane Wheeler correspondence. (1833). [Letters to Joseph John Gurney from his son William (1 December 1833) and from Daniel and Jane Wheeler, while in Russia, to their family (1833) and to Joseph, Samuel, Elizabeth and Mary Gurney. Also included is part of an account of a journey headed, “J and A Backhouse” and a silhouette possibly of Daniel Wheeler.] The Library of the Society of Friends, Manuscript Collection. London.

Elizabeth Lee papers. (1751). [silhouettes, some framed, of members of the Fry family; (1/22) prints of Priscilla Hannah Fry, Mary Tylor and Earlham House; (1/23)] The Library of the Society of Friends, Manuscript Collection. London.

Silhouettes. (n.d.). [This series consists of silhouettes of Frances Thompson, Kitty Bevington [later Newman], Candia Burlingham, Emily Fryer, Sophia Smith, Tabitha Barber, Henry Tuke, Lucy Burlingham of Lynn, Lichfield, Staffordshire, Arnee Frank, Alfred Fryer, Adey Bellamy, P Guin, Richard Burlingham, junior and Mary Pryor, with a colour miniature portrait of Ephraim Lingham. Wrapper addressed to “William Spriggs, Worcester [Worcestershire]”] The Library of the Society of Friends, Manuscript Collection. London.

Books

Bourdieu, P. (1984). Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, p.77.

Brinton, A. (1964). Quaker profiles, pictorial and biographical, 1750-1850 / Anna Cox Brinton. Wallingford, Pa.: Pendle Hill Publications.

Cobban, A. (1969). The eighteenth century: Europe in the Age of Enlightenment. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Laughon, H., Laughon, N. and Edouart, A. (1987). August Edouart, A Quaker Album: American and English DuplicateSilhouettes 1827-1845. Richmond, Va.: Cheswick Press.

Lavater, J. and Holcroft, T. (1789). Essays on physiognomy. London: Printed for G.G.J. and J. Robinson.

McNeil, P. and Vincent, S. (2017). A cultural history of dress and fashion in the age of Enlightenment. London: Bloomsbury Academic.

Rutherford, E. and Guinness, L. (2009). Silhouette. New York: Rizzoli International.

Veblen, T. and Wright Mills, C. (1965). The Theory of the Leisure Class. New Brunswick (U.S.A.) and London (U.K.): Transaction Publishers, p.64.

Journals

Simmel, G. (1957). Fashion. American Journal of Sociology, [online] 62(6), pp.541-558. Available at: http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0002-9602%28195705%2962%3A6%3C541%3AF%3E2.0.CO%3B2-2 [Accessed 30 Dec. 2017].

Websites

Artofmourning.com. (2014). Silhouettes & Shades From Miers & Field | Art of Mourning. [online] Available at: http://artofmourning.com/2014/06/02/silhouettes-shades-from-miers-field/?doing_wp_cron=1517178157.5040049552917480468750 [Accessed 18 Nov. 2017].

Collections.vam.ac.uk. (n.d.). An Unknown woman | Miers, John | V&A Search the Collections. [online] Available at: http://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O76676/an-unknown-woman-portrait-miniature-miers-john/ [Accessed 20 Nov. 2017].

Collections.vam.ac.uk. (n.d.). Silhouette of an unknown man | Field, John | V&A Search the Collections. [online] Available at: http://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O76677/silhouette-of-an-unknown-man-bracelet-field-john/ [Accessed 20 Nov. 2017].

Kara Walker. (n.d.). Works, 2013. [online] Available at: http://www.karawalkerstudio.com/5583240ee4b0fe87a727ac18/ [Accessed 26 Jan. 2018].

Npg.org.uk. (n.d.). Augustin Edouart’s silhouettes – National Portrait Gallery. [online] Available at: https://www.npg.org.uk/shop/prints/augustin-edouarts-silhouettes.php [Accessed 21 Nov. 2017].

Npg.org.uk. (n.d.). Silhouette – National Portrait Gallery. [online] Available at: https://www.npg.org.uk/collections/explore/glossary-of-art-terms/silhouette [Accessed 21 Nov. 2017].

The Art Story. (n.d.). Kara Walker Biography, Art, and Analysis of Works. [online] Available at: http://www.theartstory.org/artist-walker-kara-artworks.htm#pnt_1 [Accessed 28 Jan. 2018].

The Art Story. (n.d.). Kara Walker Biography, Art, and Analysis of Works. [online] Available at: http://www.theartstory.org/artist-walker-kara.htm [Accessed 19 Jan. 2018].

The Museum of Modern Art. (2018). Kara Walker. Gone: An Historical Romance of a Civil War as It Occurred b’tween the Dusky Thighs of One Young Negress and Her Heart. 1994 | MoMA. [online] Available at: https://www.moma.org/collection/works/110565 [Accessed 28 Jan. 2018].

The Postal Museum. (n.d.). Rowland Hill’s postal reforms | The Postal Museum. [online] Available at: https://www.postalmuseum.org/discover/explore-online/postal-history/rowland/ [Accessed 19 Nov. 2017].

Wolfe, R. (n.d.). The golden age of bourgeois portraiture, before the rise of photography. [online] The Charnel-House. Available at: https://thecharnelhouse.org/2015/08/01/the-golden-age-of-bourgeois-portraiture-before-the-rise-of-photography/ [Accessed 22 Dec. 2017].

Wood, C. (2005). Silhouettes. [online] Frieze.com. Available at: https://frieze.com/article/silhouettes [Accessed 14 Nov. 2017].

Cite This Work

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing stye below:

Related Services

View allRelated Content

All TagsContent relating to: "Arts"

Art can be described as the expression of creativity, using emotion, imagination, and skill to produce a work of art. Art is a matter of opinion and preference, and can be understood or appreciated in different ways by different people.

Related Articles

DMCA / Removal Request

If you are the original writer of this dissertation and no longer wish to have your work published on the UKDiss.com website then please: