Merchant Cement & Lime Pty Ltd Supply Chain Management Evaluation

Info: 3468 words (14 pages) Dissertation

Published: 9th Dec 2019

Tagged: ManagementSupply Chain

Industry Overview

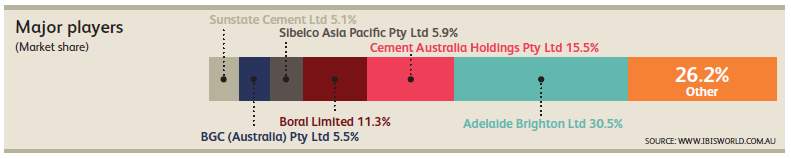

The cement and lime manufacturing industry in Australia is worth approximately A$2.6bn per annum, of which lime comprises 16.8% or A$436.8m. The industry is intensely competitive, which, over the past two decades, has driven the major players to rationalise their operations and implement highly-automated manufacturing plants (Kelly, 2017).

Traditionally, the market has been dominated by domestic producers; however, in recent years, and typical of many mature, domestic markets, increased competition and globalisation has seen an influx of imported product (Bozarth and Handfield, 2013, Kelly, 2017).

Figure 1: Major Players in the Cement and Lime Market (Kelly, 2017)

Lime is used in a wide variety of industrial applications; however, this paper will focus on the supply chain associated with imported quicklime for use in mineral extraction; in this context, gold production. It is common for the chemistry involved in leaching gold to be controlled using Calcium Hydroxide (Lime) to maintain optimal pH levels and suppress the formation of toxic Hydrogen Cyanide gas (Core_Resources, 2014).

Supply Chain Overview

The subject of this paper is the supply chain of a Melbourne-based quicklime importer, Merchant Cement & Lime Pty Ltd (‘MCL’). According to an Anti-Dumping Commission Report into MCL’s affairs by the Australian Government’s Department of Industry, Innovation and Science (ADC, 2016b), MCL describes its business as ‘a shipping, logistics and freight forwarding company’.

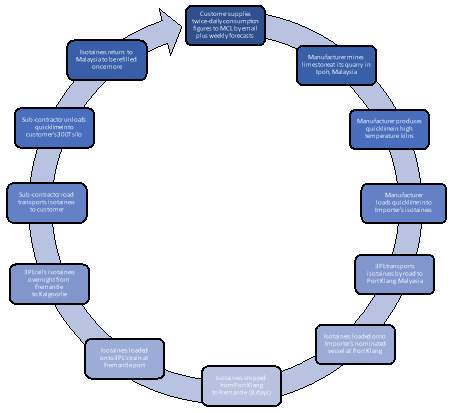

Figure 2: Supply Chain Geography – Quarry to Customer

In 2014, MCL commenced importing quicklime powder (CaO 90%) from Malaysia.

In 2014, MCL commenced importing quicklime powder (CaO 90%) from Malaysia.

It has several quicklime customers in Western Australia including Gold Fields Australia Pty Ltd, which owns and operates the St Ives Gold Mine (‘SIGM’), located 76 kilometres south-east of Kalgoorlie.

MCL’s supply chain commences upon receipt of the customer’s weekly forecast production schedule, and finishes upon delivery of quicklime into SIGM’s 300-tonne silo.

The supply chain demonstrates a moderate degree of complexity, requiring constant collaboration between customer, importer, manufacturer, 3PL partners and subcontractors.

It should be noted that MCL does not add any value to these products prior to distributing them.

Figure 2: MCL’s Imported Quicklime Supply Chain

Customer Demand

The supply chain is initiated by SIGM providing MCL with a blanket purchase order for each month’s consumption. Silo readings are provided to MCL at 6am and 6pm daily. Every Tuesday, SIGM emails MCL the mine and mill’s forecast production schedule for the following week’s requirement. This allows MCL to manage delivery scheduling and conform with MCL’s safety policy in relation to driver fatigue. In addition, SIGM is obliged under the terms of their agreement to provide a forecast of quicklime consumption to MCL every month, on a three-month rolling basis (MCL, 2017).

Armed with forecast consumption figures, MCL’s Operations Manager calculates how much quicklime will be required to sustain SIGM’s operations. He then contacts the Sales Office of the quicklime manufacturer, RCI Lime Sdn Bhd (‘RCI’), which is a private company owned by Mega First Corporation Berhad (Malaysia).

Quicklime Manufacture

According to an Anti-Dumping Commission Exporter Questionnaire (ADC, 2016a), RCI receives enquiries for lime products from MCL via email or phone call. After confirming the product specifications and requirements, RCI provides a quotation containing product description, price, packaging, quantity offered, pricing validity and credit terms. Once all terms and conditions have been negotiated and agreed, MCL will issue RCI a Purchase Order. RCI will schedule production of the required lime products, then advise MCL of the delivery date for the goods.

RCI owns and operates three mines in different locations, which hold a combined total of over 300 million tonnes in limestone reserves. RCI’s Sales Office liaises with the Quarry Manager with respect to the volume of limestone required to be made available in stockpiles at the kiln. All mines are fully integrated with their own crushing facilities and equipment necessary for moving limestone feed to one of (7) state-of-the-art kiln and hydration plants, which have a combined quicklime production capacity of 1,600 mt/day (RCI, 2017).

The limestone goes through a process of preheating, burning and cooling in the kiln for 18 to 24 hours before turning into quicklime. Quicklime output is then segregated into three different sizes, fine, medium and large, before being stored into silos according to size (ADC, 2016a). RCI’s annual production of quicklime powder is 80,000 tonnes; however, the facility is capable of producing up to 600,000 tonnes per annum (RCI, 2017).

Quicklime Dispatch

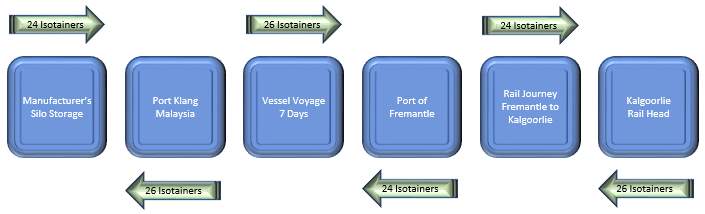

In fulfilling an export order, RCI’s dispatch team transfers the required volume of quicklime from its storage silos into purpose-built, 20’ pressurised isotainers, which are leased by MCL. Over 150 isotainers cycle continuously from RCI (Ipoh, Malaysia) to SIGM (Kambalda, W.A.) and return. A typical shipment of quicklime consists of 24 – 26 isotainers (approx. 504 – 546 tonnes) with quicklime shipments departing Port Klang, Malaysia on a weekly basis (MCL, 2017).

Maintaining the flow of isotainers between Malaysia and Australia is a constant challenge for MCL’s Operations Manager who must be acutely aware of their position within the supply chain. According to Bozarth and Handfield:

Visibility represents the most basic function of information in the supply chain. Here information allows managers to “see” the physical and monetary flows in the supply chain and, as a result, better manage them (2013, p 400).

As an importer of quicklime, constant communication with the manufacturer, 3PL providers (i.e. road, sea and rail) and the customer, are key to supply chain responsiveness. A lack of coordination, combined with complexity, will inevitably lead to disruptions in the supply chain (Bozarth and Handfield, 2013).

Figure 3 below outlines an approximation of the isotainer flow from quarry to customer and return.

Figure 3: Isotainer flow from quarry to customer and return

Third-Party Logistics Provider – Road Transit

Further coordination between the various supply chain entities is evidenced by RCI timing its deliveries to Port Klang, according to the laycan period of the vessel nominated by MCL. RCI contracts with three local third-party logistics providers (3PL), which ferry the isotainers from Ipoh in the State of Perak to Port Klang, a journey of between 209 – 221 kilometres, dependent upon whether the northern port or western port is utilised (RCI, 2017).

Once loaded, each truck passes over a nearby weighbridge upon departing RCI’s storage silos. According to the Exporter Questionnaire response prepared by RCI, transportation costs are based on invoices received from the transporter. In the absence of an invoice, transportation cost is estimated and accrued based on past experiences (ADC, 2016a).

In the event of congestion or disruption to the freeway transport route, RCI has access to a rail service 19.3km from the plant. Alternatively, there is a trunk road which connects RCI’s plant to the nearest port (RCI, 2017).

Third-Party Logistics Provider – Shipping Line

On 18 July 2017 in a personal interview, Mr C. Dunphy (Managing Director – MCL) stated that MCL contracts with ANL Container Line Pty Limited (‘ANL’) for most of its shipping requirements. MCL purchases space for its isotainers on a return slot basis, i.e. the forward journey and return journey are purchased at the same time, to ensure the empty isotainers make their way back to Port Klang. MCL does this because most shipping lines dislike transporting empty containers, as they are an inefficient use of valuable cargo space (Kristiansen, 2012).

Once the trucks arrive at Port Klang, the isotainers containing the quicklime are transferred from the truck onto the vessel by Port Klang’s stevedores, or if the vessel happens to be delayed, into a holding area at the port. According to the Exporter Questionnaire, ‘the incoterm is Free On Board (FOB) delivery to MCL’s vessel. RCI delivers the invoice and supporting documents such as delivery order and weighbridge tickets to the buyer together with the goods’ (ADC, 2016a).

According to the International Chamber of Commerce Incoterms® rules, Free On Board stipulates that the seller must deliver the goods on board the vessel nominated by the buyer at the port of shipment. Once the goods are on board the vessel, the risk of loss or damage to the goods passes to the buyer who bears all costs from that moment onward (ICC, 2010). Therefore, responsibility for the goods transfers to MCL upon crossing the ship’s rail, including freight and insurance of the cargo. Vessels depart weekly from Port Klang. A typical voyage to Fremantle takes 8 days (MCL, 2017).

Third-Party Logistics Provider – Rail Transit

On 7 July 2017, in a personal interview Mr A. Smith (Mining Chemicals Manager, W.A. – MCL) confirmed that upon arrival at the port of Fremantle (W.A.), the isotainers are unloaded from ANL’s vessel, customs cleared and as per MCL’s instructions, loaded directly onto a train occupying a nearby rail siding within the port’s boundaries, operated by Aurizon. If no train is present at the rail siding, the isotainers are loaded onto drop-deck low-loaders and transported to a nearby rail yard operated by Aurizon Ltd, which is used for temporary storage.

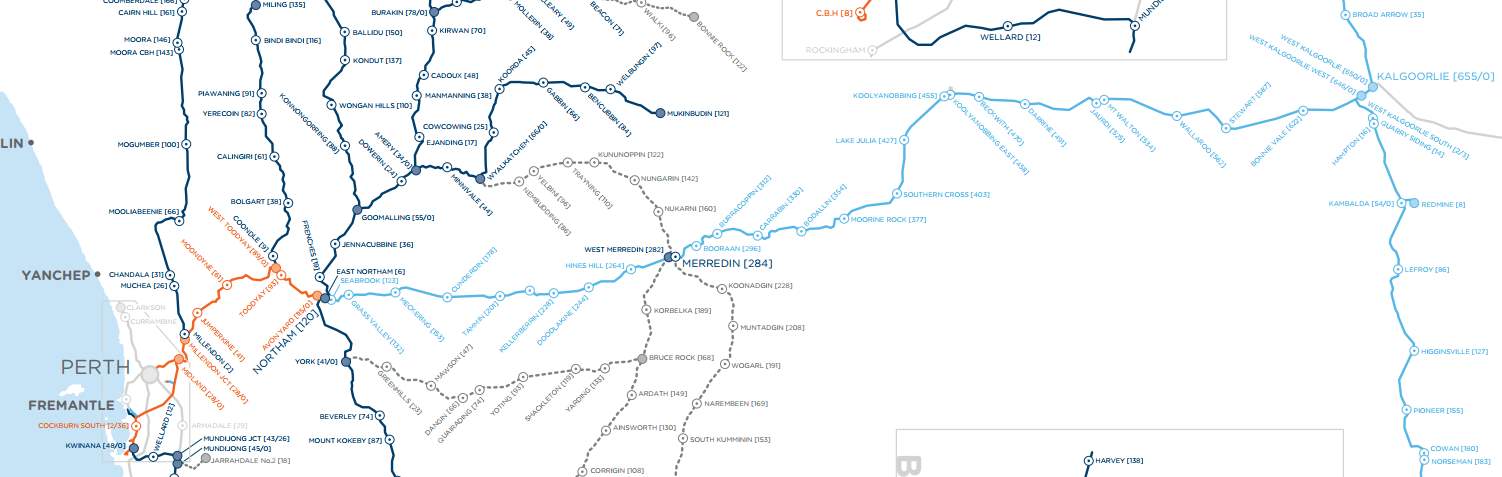

Aurizon Ltd is Australia’s largest rail freight operator and a Top 50 ASX company. It operates a fleet of trains hauling freight of various configurations throughout Western Australia and interstate (Aurizon, 2017). On 7 July 2017, in a personal interview Mr A. Smith (Mining Chemicals Manager, W.A. – MCL) confirmed Aurizon Ltd is contracted by MCL to transport the isotainers by rail from Fremantle to Forrestfield and onto the Kalgoorlie railhead. To access the rail network itself, Aurizon Ltd contracts with Arc Infrastructure who owns, operates and maintains the railway network throughout the southern half of Western Australia (AI, 2017a).

Upon departing the Fremantle port rail siding or temporary rail yard, the train carrying the isotainers makes its way to Aurizon Ltd.’s main Forrestfield yard where it is connected to a super freighter, which transits daily to Kalgoorlie departing at 6pm. A typical journey from Forrestfield (Perth) to Kalgoorlie takes approximately 17 hours to complete and covers 653 kilometres. The east-bound orange and light blue rail-lines in Figure 5 are indicative of the route taken by the super freighter.

Figure 5: 3PL rail provider transport route from Forrestfield (Perth) to Kalgoorlie, Western Australia (AI, 2017b)

If, for instance, the rail line was to suddenly be washed out for two or more days due to inclement weather, the supply chain would come under pressure and emergency protocols would need to be deployed such as transporting the isotainers from Perth to Kalgoorlie by road (MCL, 2017).

Sub-Contractor – Road Transit

MCL utilises a local sub-contractor to collect the isotainers from the Kalgoorlie rail siding and transport them by road-train to either MCL’s Kalgoorlie depot or directly to the St Ives Gold Mine, located in West Kambalda, 76 kilometres away (MCL, 2017). MCL’s operations personnel advise the sub-contractor when a delivery is due to arrive. According to MCL’s Lime Logistics Plan, minimum stock levels at the depot will be 2,000 tonnes (or 30 days consumption), maximum stock levels will be 2,500 tonnes (MCL, 2017).

Receipt of Product by Customer

Silo capacity determines the final number of isotainer deliveries. SIGM can accept deliveries of up to 75 tonnes at a time. The sub-contractor communicates with SIGM’s Processing Superintendent with respect to how much quicklime to deliver. The sub-contractor delivers using 63-tonne road trains.

At present, the aim is to keep SIGM’s 300-tonne silo above 50% of capacity but as close to 100% as possible (MCL, 2017). Once the delivery is complete, the sub-contractor alerts MCL and an invoice can be issued to the customer.

Isotainer Return Journey

Once empty, the isotainers are returned to the Kalgoorlie rail-head for back-loading by rail to Fremantle (and eventually to Malaysia); however, simple oversights such as failing to remove all exterior signs of contamination prior to export at Fremantle (i.e. oil, grease, insects, bird droppings, etc.), could lead to officers of the Department of Agriculture and Food (Quarantine WA) refusing to clear an isotainer for export, resulting in unwanted delays in returning the isotainers to Malaysia.

Conclusion

In conclusion, MCL’s imported quicklime supply chain is a delicate balancing act, requiring constant monitoring on the part of its operations personnel and frequent vertical collaboration with its customers, suppliers, 3PL partners and sub-contractors. This minimises the possibility of the ‘Bullwhip Effect’ occurring as variability is minimised, uncertainty is removed, lead times are compressed and increased safety stock is avoided (Simchi-Levi et al., 2008).

Despite being independent entities, RCI and MCL are highly interdependent to the point where their senior executives regularly meet with each other in either Australia, Malaysia or by video conference. Strategic partnerships such as these demonstrate that quicklime can be imported into Australia and still compete in terms of price and service with local domestic producers, who have dominated the market until now. This is due to the high level of information sharing between the parties such as production forecasts, usage statistics, isotainer movements and shipping schedules.

Mangan and Lalwani (2016) suggests that supply chains can be both complicated and complex; however, in this instance, MCL’s supply chain isn’t so much complicated, as the product itself does not change form or require integration with another element. It is; however, complex due to the number of logistical touch points and handovers throughout the supply chain. That said, MCL has expensed considerable effort in ensuring surety of supply for its customers in the West Australian goldfields, whose operations depend upon a steady supply of quicklime to guarantee gold production.

References:

ADC 2016a. 010 Exporter Questionnaire – RCI Lime. www.adcommission.gov.au: Department of Industry, Innovation and Science.

ADC 2016b. Application for Anti-Dumping Measures: Quicklime Exported from Malaysia, the Kingdom of Thailand (Thailand) and the Socialist Republic of Vietnam (Vietnam). In: DEPARTMENT OF INDUSTRY, I. A. S. (ed.). Anti-Dumping Commission.

AI. 2017a. Company Overview [Online]. Arc Infrastructure Web Page: Arc Infrastructure. Available: http://www.arcinfra.com/Company [Accessed 24 July 2017 2017].

AI. 2017b. Rail Freight Network Map (Western Australia) [Online]. Arc Infrastructure. Available: http://www.arcinfra.com/ARCInfrastructure/media/documents/Network%20Specifications/ARC_Map_Network.pdf [Accessed 22nd July 2017].

AURIZON. 2017. Company Overview [Online]. Available: https://www.aurizon.com.au/company/overview [Accessed 24 July 2017 2017].

BOZARTH, C. & HANDFIELD, R. 2013. Introduction to Operations and Supply Chain Management (3rd Edition), New Jersey, U.S.A., Pearson Education Inc, publishing as Prentice Hall.

CORE_RESOURCES. 2014. The Metallurgy of Cyanide Gold Production – An Introduction [Online]. Core Resources Pty Ltd. Available: http://www.coreresources.com.au/the-metallurgy-of-cyanide-gold-leaching-an-introduction/ [Accessed 16th July 2017].

ICC. 2010. Incoterms® rules 2010 [Online]. International Chamber of Commerce. Available: https://iccwbo.org/resources-for-business/incoterms-rules/incoterms-rules-2010/ [Accessed 22nd July 2017].

KELLY, A. 2017. IBISWorld Industry Report C2031a: Cement and Lime Manufacturing in Australia.

KRISTIANSEN, T. 2012. Empty containers cost Maersk Line USD 1 billion a year [Online]. shippingwatch.com: shippingwatch.com. Available: http://shippingwatch.com/articles/article4891909.ece [Accessed 23 July 2017 2017].

MANGAN, J. & LALWANI, C. 2016. Global Logistics and Supply Chain Management (3rd Edition), West Sussex, United Kingdom, John Wiley & Sons Ltd.

MCL 2017. Merchant Cement & Lime Pty Ltd: Logistics Management Plan for the Supply of Lime Products to Gold Fields Operations. Perth, Western Australia: Merchant Cement & Lime Pty Ltd.

RCI 2017. Supply Chain Overview. Malaysia: RCI Lime.

SIMCHI-LEVI, D., KAMINSKY, P. & SIMCHI-LEVI, E. 2008. Designing and Managing the Suppy Chain: Concepts, Strategies, and Case Studies (Third Edition), Boston, Massachusetts, USA, McGraw Hill / Irwin.

Cite This Work

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing stye below:

Related Services

View allRelated Content

All TagsContent relating to: "Supply Chain"

A Supply Chain is a system in place between companies and their suppliers, from producing a product to distributing it ready to be sold. An effective and smooth running supply chain can contribute to the successful running of a business.

Related Articles

DMCA / Removal Request

If you are the original writer of this dissertation and no longer wish to have your work published on the UKDiss.com website then please: