Dissertation on Syntactic Processing in Bilinguals

Info: 13153 words (53 pages) Dissertation

Published: 17th Nov 2021

Tagged: Linguistics

Abstract

Selective activation of syntactic representations across a bilingual’s languages was investigated by analyzing cross-linguistic syntactic influence. Processing speed and accuracy of adult Spanish-English and monolingual English speakers was compared on a grammaticality judgment task. For bilinguals, their dominant L2 (English) influenced their heritage language and vice versa. This was found for differential object marking, generics, noun-adjective order, and the expression of the subjunctive mood and was modulated by age of acquisition of English, despite the fact that all participants acquired both languages before the age of 7. In English, child L2 acquirers experienced interference, whereas simultaneous bilinguals did not. In Spanish, in contrast, simultaneous bilinguals exhibited greater influence from English than participants who did not begin learning English until age 4. Findings indicate that processing is non-selective for language for heritage bilinguals at the syntactic level and this selectivity differs based on age of L2 acquisition.

Is Syntactic Processing Selective for Language In Adult Heritage Bilinguals?

How does the mind of a bilingual access syntactic representations in each language? Is syntax processed in a language-selective fashion, or are syntactic representations from both languages retrieved when processing syntax in only one language? Many studies of lexical processing in bilinguals have found evidence that the lexicon is accessed non-selectively across a bilingual’s languages, meaning that when a bilingual attempts to retrieve a word from one language, words from the other language are also activated. Although some tasks assessing performance in a bilingual’s dominant L1 can show evidence of language selectivity, “the presence of nonselectivity at all levels of planning spoken utterances renders the system itself fundamentally nonselective” (Kroll, Bobb, & Wodniecka, 2006, p. 132). Evidence supporting the non-selective nature of lexical processing comes from studies of auditory word recognition (Guasch, Ferré, & Haro, 2017; Marian & Spivey, 2003; Lagrou, Hartsuiker & Duyck, 2011), visual word recognition (Dijkstra & Van Heuven, 2002; Duyck, 2005), cross-linguistic lexical priming (Altarriba, 1990; Costa, Miozzo, & Caramazza, 1999) and translation tasks (De Groot, 1992; De Groot, Dannenburg, & Van Hell, 1994).

In this study, we investigated whether syntactic processing in bilinguals is also non-selective for language in a population of adult heritage speakers of Spanish living in the United States. In other words, are syntactic structures from both languages active during processing in one of the languages?

Hartsuiker, Pickering, and Veltkamp (2004) found that syntactic priming occurred between Spanish and English. Specifically, the bilinguals produced more passive sentences in English after hearing a passive sentence in Spanish. Extending this line of investigation, Bernolet, Harsuiker, and Pickering (2013) found that higher language proficiency scores were related to greater priming or stronger shared representations. Harsuiker, Beerts, Loncke, and Bernolet (2016) found that priming between first and second languages is equivalent to priming between two second languages providing further evidence and specificity for shared systems. In an ERP study on English-Welsh speakers, evidence for non-selectivity in syntactic activation was found (Sanoudaki & Thierry, 2015). However, this effect was restricted to those with higher proficiency in Welsh. Taken together, these findings suggest that language ability can contribute to the selectivity of the system.

Heritage speakers are individuals who acquired their L1 in the home from birth but who were also exposed from a young age to an L2 (English in this case) that is socially dominant in the larger community (Valdés, 2000). As a group, heritage speakers are quite diverse in their language background and linguistic competence (see Montrul, 2008; Rothman, 2007, 2009). However, our population shared a number of significant characteristics. Our participants received most or all of their formal education in English; only a small handful had studied Spanish in a formal setting as children and none had studied Spanish at the college level. They all began acquiring Spanish from birth, considered themselves to be fluent in Spanish, and all used Spanish on a daily basis to communicate with family and friends. All reported themselves to be at least moderately comfortable reading and writing Spanish. Importantly, some of our heritage speakers were also exposed to English between the ages of birth and 3 years (simultaneous acquirers), whereas others were not exposed to English until they started school between the ages of 4 and 6 (child L2 learners). In addition, all of our participants continued to live at home while they attended university, and for that reason were tested in the same bilingual environment in which they had grown up with continual exposure to both languages.

Cross-linguistic influence in heritage bilinguals

Age of L2 acquisition can affect the language development of heritage speakers by altering their ultimate level of L1 attainment. Research on heritage speakers of Spanish has indicated that they do not perform identically to Spanish-speaking monolinguals on various tests of syntactic ability, suggesting that in their L1, heritage bilinguals have either experienced language attrition or they did not acquire certain syntactic distinctions in the first place (e.g., Montrul, 2002, 2004; Montrul & Potowski, 2007; Silva-Corvalán, 1994, 2008). These studies have pointed to age of acquisition as an important variable in predicting whether a heritage speaker’s grammar will diverge from a monolingual’s, in particular, whether the L2 was acquired simultanteously with the L1, in early childhood (roughly between the ages of 4 and 7), or after age 7.

The Spanish grammars of adult heritage bilinguals diverge from those of monolinguals in numerous areas. In the present study, we investigated whether heritage speakers show evidence of cross-linguistic influence in syntactic processing in precisely the areas of grammar which have been found to be vulnerable to such influence in language production. These include the production of null and overt subjects, word order, the use of differential object marking (producing the marker a with animate, specific direct objects), the use of generics, and subjunctive verb morphology (Ionin & Montrul, 2010; Montrul, 2002, 2004, 2008, 2009; Montrul & Perpiñán, 2011; Montrul & Sanchéz-Walker, 2013; Silva-Corvalán, 1994). Similar results have been found for heritage speakers of Spanish in their production of tense and aspectual distinctions, topicalization, and clitic left dislocation (Montrul, 2002; Zapata, Sánchez, Toribio, 2005). Rinke and Flores (2014) conducted a grammaticality judgment test on Portuguese-German heritage bilinguals examining morphosyntactic knowledge of clitics, but they did not find evidence for cross-linguistic influence. However, reaction time was not measured and age of acquisition was not examined.

For many heritage speakers of Spanish growing up in the U.S., intensive exposure to English before mastery of tense, agreement and mood morphology is acquired in Spanish results in non-native like production of these morphological distinctions (Montrul, 2002, 2009; Montrul & Perpiñán, 2011; Silva-Corvalán, 1994). In Spanish, unlike English, the indicative and subjunctive moods are morphologically marked. The selection of a particular mood in Spanish is complex and governed by many factors; however, in general terms, certain verbs and expressions always select the indicative or subjunctive moods, whereas others can vary according to the pragmatic context. For example, predicates of desire, such as (1)a select for the subjunctive mood in the embedded clause, whereas epistemic verbs such as (1)b select a complement marked with the indicative mood morphology.

(1) a. Alicia quiere que su hija practique el piano.

Alicia wants-indicative that her daughter practice-subjunctive the piano

‘Alicia wants her daughter to practice piano’

b. Alicia sabe que su hija practica el piano.

Alicia knows-indicative that her daughter practices-indicative the piano

‘Alicia knows that her daughter practices the piano’

In Spanish, monolingual children begin using the subjunctive mood at approximately four years of age, but it is not fully acquired until age eight or later (Montrul, 2008; Perez-Leroux, 1998).

Montrul and Perpiñán (2011) investigated knowledge of tense, aspect, and mood morphology in heritage speakers and Spanish L2 learners, who began learning Spanish around puberty. They used two tasks that required participants to select the correctly inflected form in a written context—one that examined the preterit/imperfect contrast, and the other testing knowledge of the use of the subjunctive versus indicative mood. The authors found that heritage learners were more accurate than L2 learners in choosing the correct aspectual form, but not in choosing the correct mood, a difference that they attributed to the fact that aspect is acquired earlier than mood in Spanish.

Ionin and Montrul (2010; Montrul & Ionin, 2011) investigated the interpretation of generics in Spanish by heritage adult learners, another area in which Spanish and English grammars diverge. Spanish and English differ in the expression of generic reference because English has two plural forms, one which contains a bare NP (such as ‘tiger’) and has a generic reading as in (2)a, which refers to tigers in general, and another which includes a definite determiner (‘the tigers’) and has a non-generic, specific reading (6)b, and refers to a particular group of tigers.

(2) a. Tigers eat meat. [+generic reference, -specific reference]

b. The tigers eat meat. [-generic reference, +specific reference] (Ionin & Montrul, 2010)

In contrast, Spanish uses phrases with definite determiners such as (7)b to express both specific and generic reference, depending on the context. Omitting the definite determiner is ungrammatical, as in (3)a.

(3) a. *Tigres comen carne.

tigers eat meat

‘Tigers eat meat’

b. Los tigres comen carne. [+generic reference, +specific reference]

the-pl tigers eat meat

‘The tigers eat meat.’

Using comprehension tasks, Ionin and Montrul (2010) found that heritage learners accepted bare plural subjects such as (3)a as grammatical in Spanish and preferred a specific rather than generic interpretation for sentences such as (3)b, unlike native speakers. The authors interpreted these results as evidence of transfer from English to Spanish. Montrul and Ionin (2011) compared the performance of Spanish L2 learners with heritage learners on the same tasks, and found that for both groups, proficiency level was a better predictor than age of acquisition for the participants’ performance.

The use of differential object marking (DOM) (producing the marker a with animate, specific direct objects) is another area in which the performance of heritage learners of Spanish differs from that of native speakers. In Spanish, the use of the marker a is obligatory in (4a), since the direct object is specific and animate:

(4) a. [+ animate, + specific direct object (a-marker needed)]

He visto a Julieta

(I) have seen a-marker Julieta

‘I have seen Juliet’

A study of four monolingual children acquiring Spanish by Rodríguez-Mondóñeo (2008) indicated that children begin using differential object marking early, and that it is largely acquired by age 3.

Despite the early acquisition of differential object marking, Montrul and Bowles (2009) found that adult heritage speakers of Spanish were very inaccurate both in producing sentences with differential object marking as well as in making judgments of the grammaticality of DOM. This was true even of heritage learners with high levels of proficiency, indicating that DOM is highly problematic for bilingual learners despite its early appearance developmentally.

In summary, research on the grammars of heritage bilinguals suggests that age of acquisition of the L2 is an important predictor of the type of cross-linguistic influence that will occur in the L1. In the study reported here, we investigated syntactic non-selectivity by examining whether there is bidirectional cross-linguistic influence in heritage bilinguals (from the L1 to the L2 and vice-versa) during syntactic processing by addressing the following research questions:

1) Do bilingual heritage speakers of Spanish show evidence of cross-linguistic influence during syntactic processing, as reflected in accuracy and speed while performing a grammaticality judgment task?

2) If cross-linguistic influence is established, is it bidirectional, or does it occur only from the L2 to the L1?

3) Do the grammaticality judgments of heritage bilinguals who have learned both languages simultaneously (age 0-3 years) differ in speed and/or accuracy from those who have learned English as an L2 later in childhood (age 4-6 years)?

In order to investigate evidence of cross-linguistic influence in bilingual processing, we used a timed grammaticality judgment task in both English (Experiment 1) and Spanish (Experiment 2). The sentences in the grammaticality task all involved aspects of grammar where English and Spanish diverge and which have been shown to be vulnerable to influence in adult heritage learners or child bilinguals, including the expression of generics, differential object marking, word order, the use of the subjunctive mood, and word order in noun phrases.

We hypothesized that if our participants experience cross-linguistic syntactic influence, it will manifest itself in reduced accuracy and slower reactions times while judging sentences for which a word-to-word translation should yield a differing grammaticality across Spanish and English (“conflicting” sentences), as compared to sentences in which the grammaticality judgment for a direct translation should yield the same judgment (“converging” sentences). To address possible effects of age of acquisition, we compared the performance of our simultaneous acquirers to our child L2 learners and also, in Experiment 1, to that of monolingual speakers of English.

Experiment 1

Experiment 1 investigates whether adult heritage bilinguals’ language processing differs from that of monolinguals. Specifically, this study examines two questions:

- Do English monolinguals and Spanish-English heritage bilinguals differ in language processing speed and accuracy in English?

- Does Spanish syntactic knowledge influence linguistic processing in English?

We expected bilinguals to perform worse on “conflicting” sentences in which the syntax of the two languages differs (i.e., sentences in which a given structure is grammatical in one language but not the other) than on “converging” sentences (i.e., sentences that are either syntactically correct or syntactically incorrect in both languages). Decreased performance could be revealed through slower reaction times, a greater error rate, or both.

Method

Participants

Participants were undergraduate students at an urban university in the northeastern United States. They were recruited through the participant pool for an Introduction to Psychology course and were given course credit for their participation. Forty-seven participants were monolingual speakers of English (mean age = 20.0 years, SD = 2.0); 22 were bilingual heritage speakers of Spanish (mean age = 19.9 years, SD = 1.5), all of whom began acquiring Spanish at birth. Half the bilinguals began acquiring English between birth and age 3. Following Montrul (2002), this group will be referred to as simultaneous acquirers. Also following Montrul (2002), the other eleven began acquiring English between the ages of 4 and 6. This group will be referred to as child L2 learners. All bilinguals were proficient in both languages as verified by self-report and proficiency exams (all participants who scored below 65% on either exam were excluded from all further analyses allowing for the comparison of bilinguals who are fairly proficient in both languages). Additional characteristics of the two bilingual groups are presented in Tables 1 and 2. The country of origin of the Spanish spoken by the majority of the bilinguals was the Dominican Republic, Puerto Rico, or Cuba. A small number spoke Spanish originating from Mexico, Peru, El Salvador, Ecuador, or Colombia.

Stimuli and Apparatus

The sentences presented were recorded in English and were designed to be comparable in length (similar number of words) and complexity (similar number of arguments with basic content words) (see Appendix A). The stimulus sentences and the Spanish and English proficiency exams (obtained from the University of Michigan) were presented on a Macintosh laptop computer using PsyScope for Mac OSX. The experimental test was about 10 min in duration, and the proficiency exams were each approximately 30 minutes in duration. The participants listened to the experiment through Koss Optimus Pro-135 headphones. Participants’ responses and reaction times in ms were recorded for each sentence and proficiency exam question.

Design

Half of the 96 test sentences were “conflicting” and half were “converging.” In the conflicting sentences, the grammatical rules for Spanish and English were in opposition—that is, if the conflicting sentences were translated word for word into Spanish, they should elicit a different grammaticality judgment than in English. In the converging sentences, in contrast, the grammatical rules for Spanish and English coincided. Therefore, converging sentences should elicit the same judgment in either Spanish or English. Half the sentences of each type were grammatical and half were ungrammatical. Each of the 48 conflicting sentences had a semantically matched converging sentence that had the same grammaticality value in English (i.e., both were grammatical or both were ungrammatical), employed the same type of sentence structure, and contained the same verbs and nouns. The matching sentences differed exclusively in the syntactic configuration that caused one member of the pair to be conflicting and the other to be converging. This was done in order to control for reaction time differences that might arise from differences in word familiarity or sentence difficulty across the two sentence types. In order to capture a wide range of syntactic errors, approximately equal numbers of converging and conflicting ungrammatical sentences contained errors in noun phrase, determiner phrase, subjunctive mood, preposition phrase, negation phrase, or wh-question word order (see Appendix A). The sentences were divided into two blocks, each consisting of 24 conflicting sentences and the 24 non-matching converging sentences. Thus, the two members of the semantically matched pairs appeared in different blocks. Half of the sentences in each block were grammatical in English. The order of presentation of the two blocks was counterbalanced across subjects. The order of sentence presentation within each block was randomized across subjects.

Procedure

Participants first filled out a consent form and a questionnaire requesting information about their language history, knowledge, and use of Spanish and English. For the grammaticality judgment test, participants were seated at a computer and asked to press one key if they thought the sentence was grammatical (sounds like the acceptable or correct way to say something) and another key if they thought the sentence was ungrammatical. Participants were asked to respond as quickly and as accurately as possible. To familiarize participants with the procedure, they first responded to four practice sentences for which they were given feedback. No feedback was given during the test. After the first test block, a break was permitted, but few participants reported taking a break. The second block followed the same procedure as the first.

Following the experimental test, the bilingual participants completed the Spanish and English proficiency exams to confirm listening comprehension competence in each language; the order of these exams was counter-balanced across subjects. Participants were provided with paper versions of the exams in case they missed the presentation of an item but were asked to focus on listening rather than reading. The proficiency exams were recorded by a native speaker of the language. After the experiment was complete, the experimenter explained the purpose of the study to the participants.

Results

Two of the 96 sentences were excluded from the analysis due to ambiguity in determining the correct grammaticality judgment. To remove outliers, trials in which a participant’s reaction time was greater than 4000 ms were excluded from all analyses. In addition, trials for which the participant’s grammaticality judgment was incorrect were excluded from reaction time analyses.

Reaction Time Results

Since preliminary analysis failed to reveal any significant effects of block (one vs. two) and order (block one first vs. block two first), these factors were dropped from all subsequent analyses. To compare the performance of the three language groups, we conducted a set of planned three-way, mixed design analyses of variance (ANOVA) with language group as a between subjects factor and sentence type (conflicting vs. converging) and grammaticality (grammatical vs. ungrammatical) as within subjects factors. All three ANOVAs revealed main effects of grammaticality, all F’s (1, 56) > 9.09, all p’s

The ANOVA comparing monolinguals to simultaneous bilinguals revealed only the main effect of grammaticality. No other main effects or interactions were significant.

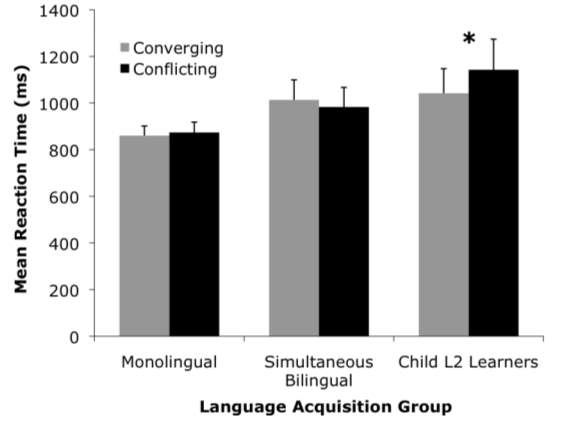

The comparison between monolinguals and child L2 learners, however, revealed a main effect of language group, F(1, 56) = 4.57, p M = 1096.9 ms, SE = 118.7, and M = 867.4, SE = 41.8, respectively). The analysis also revealed a main effect of sentence type, F(1, 56) = 6.42, p M = 894.6 ms, SE = 39.7, and M = 924.6 ms, SE = 45.5, respectively). However, this effect was modulated by a marginally significant interaction between language group and sentence type, F(1, 56) = 3.38, p = .07 (see Figure 1).

Finally, the ANOVA comparing simultaneous bilinguals to child L2 learners revealed the main effect of grammaticality. However, it too revealed an interaction between language group and sentence type, F(1, 20) = 4.65, p

To further illuminate the interactions between language group and sentence type, a set of follow-up paired t-tests compared each group’s performance on the two sentence types (Figure 1). These analyses revealed that only the child L2 learners were significantly slower to judge conflicting vs. converging sentences, t(10) = 2.54, p t’s ns).

Error Rate Results

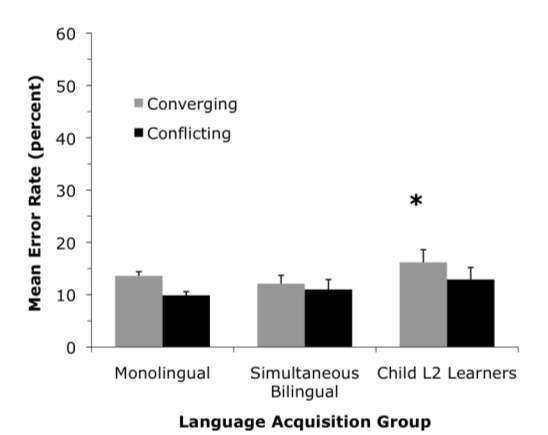

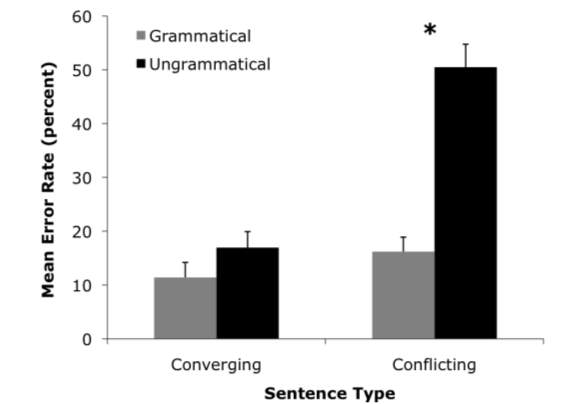

Since preliminary analyses failed to reveal any significant effects of block or order, these factors were dropped from subsequent analyses. Error rates were analyzed with the same planned, three-way ANOVAs that were conducted on the reaction time data. All three ANOVAs revealed main effects of grammaticality (all F’s > 12.43, all p’s 5.49, both p’s

Discussion

The performance of simultaneous bilinguals did not differ from monolingual speakers of English with respect to either reaction times or error rates in Experiment 1. Although it is possible that more sensitive tests might reveal differences between these groups, these null findings are consistent with the proposal that heritage speakers who acquire both the home and dominant languages before the age of 3 experience little interference from the home language into the dominant language.

However, there were several differences between participants who began learning English between the ages of 4 and 6 and both monolingual English speakers and simultaneous bilinguals. First, early child L2 learners were slower on the whole than monolinguals to judge sentence grammaticality. They also made marginally more errors than monolinguals. Notably, however, these individuals were systematically slower (though not less accurate) than either monolinguals or simultaneous bilinguals in judging conflicting sentences that were grammatical in one language but ungrammatical in the other. These differences were obtained despite the fact that our child L2 learners learned English before the age of 6. Like the simultaneous bilinguals, the child L2 participants used English daily, performed comparably to our simultaneous bilinguals on their English proficiency tests, and have received most or all of their formal schooling in English. It is thus unlikely that our child L2 learners are incomplete acquirers of English. Rather, it seems that these results reflect syntactic interference from Spanish in the processing of sentences in English and non-selectivity in syntactic activation, perhaps due to greater activation of the Spanish of the L2 speakers than the simultaneous bilinguals. The fact that the L2 learners scored significantly higher than the simultaneous bilinguals on their Spanish proficiency tests (see Table 1), is consistent with this proposal. The weaker overall Spanish proficiency of our simultaneous bilinguals may have been insufficient to interfere with a strong, dominant L2. These results are consistent with findings that even small differences in pre-pubertal age of acquisition can affect the degree of cross-linguistic influence (Bernolet et al., 2013; Dussias, 2001; Hohenstein, Eisenberg, & Naigles, 2006; Montrul, 2002; Weber-Fox & Neville, 1996; Zapata et al., 2005).

Most previous research on heritage bilinguals has revealed evidence of interference from the dominant language into the home language. It is therefore important to investigate whether our experimental paradigm also reveals interference from English into Spanish. Moreover, the fact that we found differences in syntactic interference in English between heritage speakers who learned English between the ages of 0 and 3 as compared to those who learned English between the ages of 4 and 6 raises the possibility that our paradigm is robust enough to reveal age of acquisition effects on the degree of interference from English into Spanish as well. However, in judging sentences in Spanish, we might expect to find more interference in simultaneous bilinguals, whose Spanish may be less robust than child L2 learners, either as a result of less complete acquisition or greater attrition. Experiment 2 investigates this possibility.

Experiment 2

Experiment 2 investigated whether Spanish heritage speakers experience interference from English to Spanish, using the same methodology as Experiment 1. If heritage speakers experience interference from the dominant language (English) to the home language (Spanish), then all participants should be slower and less accurate to judge conflicting than converging sentences in Spanish. However, if age of L2 acquisition exerts differential effects on degree of interference, simultaneous bilinguals should experience more interference than child L2 learners.

Method

Participants

Twelve bilingual heritage speakers of Spanish were recruited from the same population and in the same manner and using the same exclusionary criteria as Experiment 1 (mean age = 20.5 years, SD = 1.3). Similar to Experiment 1, all began acquiring Spanish at birth and were proficient in both languages as verified by self-report and proficiency exams. Half the participants were simultaneous bilinguals who began acquiring English between birth and age 3. The other six were child L2 learners who began acquiring English between the ages of 4 and 7. Additional language characteristics of each group are provided in Tables 5 and 6. Most participants spoke Spanish originating from Cuba or the Dominican Republic; the others spoke Spanish originating from Puerto Rico, Peru, Nicaragua, or Guatemala.

Stimuli and Apparatus

The sentences were Spanish translations of the sentences presented in English in Experiment 1. Because translating the conflicting sentences word-for-word into Spanish changed their grammaticality value, we slightly altered the converging sentences in order to rematch their grammaticality value with their paired conflicting sentences to retain the overall structure of the stimulus set (e.g. adjective-noun ordering would be switched). The proficiency exams and apparatus were identical to Experiment 1.

Design and Procedure

Both design and procedure were identical to those of Experiment 1.

Results

To remove outliers, as in Experiment 1, all trials in which reaction time exceeded 4000 ms, were excluded from both reaction time and error rate analyses. In addition, trials in which the response was incorrect were excluded from the reaction time analyses.

Reaction Time Results

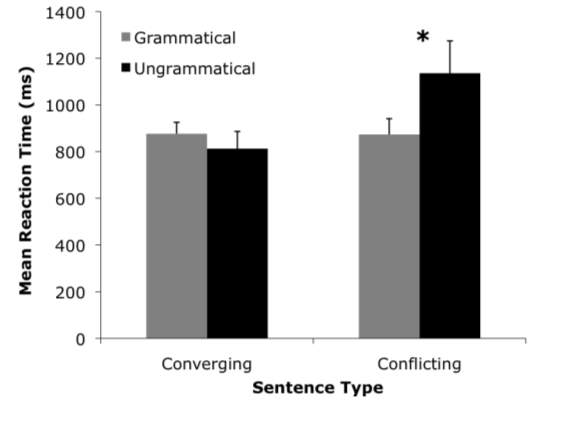

Order (block one first vs. block two first) and block (one vs. two) were excluded since preliminary analyses revealed no significant effects. A three-way mixed design ANOVA was conducted with language group (simultaneous bilingual vs. child L2 acquirer) as a between subjects factor and grammaticality (grammatical vs. ungrammatical) and sentence type (conflicting vs. converging) as within subjects factors. The ANOVA revealed a main effect of sentence type, F(1, 10) = 8.57, p M = 1004.63 ms, SE = 322.56) than converging sentences (M = 844.55 ms, SE = 189.01). The ANOVA also revealed a type by grammaticality interaction, F(1, 10) = 14.53, p F(1, 10) = 7.31, p

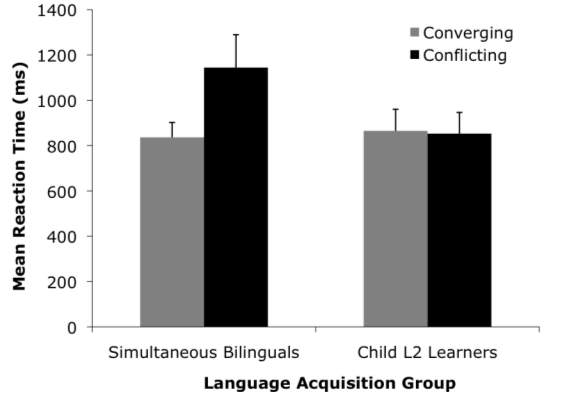

Follow-up analyses were conducted to further illuminate the interactions reported above. Paired-sample t-tests revealed that overall, participants were slower to judge ungrammatical conflicting sentences than ungrammatical converging sentences, t(11) = 3.12, p = .01. Their reaction times for grammatical conflicting and converging sentences did not differ, t(11) ns. Two independent samples t-tests compared the performance of the two groups of bilinguals. The simultaneous bilinguals were slower to judge conflicting than converging sentences, t(5) = 3.13, p t(5) ns (see Figure 4).

Error Rate Results

Since preliminary analysis failed to reveal any effect of block or block order, these variables were excluded from further analysis of the error rate data. An identical three-way, mixed design ANOVA was conducted on error rates. This analysis revealed a main effect of grammaticality, F(1, 10) = 17.22, p

Paired t-tests revealed that whereas accuracy for grammatical conflicting and converging sentences did not differ, t(11) = 1.18, p = .26, participants were less accurate in judging ungrammatical conflicting sentences than ungrammatical converging sentences, t(11) = 6.09, p T-tests following up the marginal interaction between language group and sentence type revealed that both groups performed significantly worse on conflicting than converging sentences (both t’s(5) > 6.54, both p’s t’s(10) p’s > .2) (see Table 7).

Discussion

The focal question of this study was whether or not heritage speakers of Spanish are influenced by their knowledge of English while they are processing only in Spanish as demonstrated by slower reaction times and/or more errors on the conflicting over the converging sentences. This result was obtained for both reaction times and error rates on the ungrammatical sentences. Our heritage speakers were less accurate at judging ungrammatical Spanish sentences in which the grammatical structure would be acceptable in English. In contrast, they judged grammatical Spanish sentences accurately irrespective of whether these sentences would have been grammatical or ungrammatical in English. It thus appears that exposure to English has broadened the range of acceptable Spanish syntactic structures for these early bilinguals. Furthermore, this interference occurred during processing exclusively in Spanish, suggesting that bilinguals need not be in a “bilingual mode” (as suggested by Grosjean, 2001) to experience syntactic interference. This is consistent with the dominant language transfer found in heritage bilinguals as demonstrated in Montrul and Ionin, (2012).

Age of acquisition of English also affected performance. When evaluated separately, our simultaneous bilinguals produced higher reaction times on conflicting than on converging sentences, whereas our child L2 learners as a group did not. These results suggest that acquiring both the home and dominant language from birth results in more interference from the dominant to the home language. This is consistent with the findings of Sanoudaki and Thierry (2015) who argue for the role of verbal fluency in non-selectivity. These results must be interpreted with some caution as number of participants in each language group was quite small. Nonetheless, the group as a whole demonstrated strong evidence of cross-linguistic influence.

General Discussion

In this study we investigated whether heritage speakers of Spanish experienced cross-linguistic influence in syntactic processing both in Spanish and in English. Several findings emerged. First, unlike previous studies which only examined one of the languages of heritage bilinguals, our research found evidence of influence from the dominant L2 into the home language as well as from the home language into the L2. In addition, we found evidence of cross-linguistic influence in processing syntax beyond priming, as opposed to the lexicon, as previous research has shown (Dijkstra, Timmermans & Schriefers, 2000; Hohenstein et al., 2006; Pavlenko & Jarvis, 2002).

Furthermore, we found that the presence of convergence in grammaticality across the two languages was an important predictor of the degree of interference in the bilinguals’ judgments, both in terms of the accuracy and the latency of the judgments.

Our results also revealed that this interference was modulated by age of acquisition for both Spanish and English, despite the fact that all participants acquired both languages before the age of 7, well within the putative sensitive period. These age of interference effects were language-specific: in English, child L2 acquirers experienced interference whereas simultaneous bilinguals did not. In Spanish, in contrast, simultaneous bilinguals exhibited greater interference from English than did participants who did not begin learning English until age 4. This asymmetry suggests that even small differences in the age at which a language is acquired influence the degree to which heritage bilinguals experience cross-linguistic transfer in their two languages.

The results from Experiments 1 and 2 differed in several respects. In Experiment 1 for English, evidence for interference came almost exclusively from reaction time data. Child L2 learners’ judgments were slower on the whole than monolinguals, and they were slower to judge conflicting than converging sentences. However, they made only marginally more errors than monolinguals, a pattern that did not differ across sentence type. In contrast, Experiment 2, which tested knowledge of Spanish, we found that reaction times and accuracy were both adversely affected specifically for ungrammatical sentences in which a word-to-word translation into English would be grammatical. Given that we do not have a Spanish monolingual comparison group, it is conceivable that our ungrammatical conflicting sentences were somehow simply more difficult than our converging sentences in Spanish, despite the fact that overall syntactic structure and individual content words were matched across the two sentence types. However, these effects were specific to ungrammatical conflicting sentences, which could predictably be quite susceptible to cross-linguistic influence as the syntactic structure is used in the other language.

We propose that the type of grammatical influence seen in our participants is the consequence of long-term, cross-linguistic activation resulting from non-selective access to both languages during syntactic processing. Over time, activating grammatical representations from two languages simultaneously allows representations from one language to become acceptable in the other language. While research on bilingual priming has found that only sentences with similar structures are primed across languages, if bilingual processing is non-selective for language then syntactic configurations which are grammatical in language A may be activated in language B even if they are not primed in language B, given that they do not have an analogous structure to map onto. Eventually, the non-native configurations may become part of the grammar of language B. Certainly, in the case of heritage grammars we see many examples of non-native-like constructions which follow the grammatical or semantic rules of the bilingual speaker’s other language and are clearly the result of cross-linguistic contact.

A psycholinguistic model of how cross-linguistic contact could result in the syntactic changes seen in heritage bilinguals’ grammars is provided by the Parallel Architecture Model (Culicover & Jackendoff, 2005; Jackendoff, 1997, 2007, 2011). This model assumes that the language faculty consists of independent modules for syntax, semantics, and phonology which are linked by interfaces. In this model, words are interface rules linking a phonological string with a syntactic tree and a semantic representation, combining all three components simultaneously. For example, “the cat” would yield the following tripartite structure as it is combined with other phrases to form a sentence, so that constraints on syntactic, phonological and semantic well-formedness would all operate in parallel (Jackendoff 2007), as in (5):

(5) [ð ə]2 [k æt]1 NP [CAT1::DEF2]

(5) [ð ə]2 [k æt]1 NP [CAT1::DEF2]

Det2 N1

This model also posits that syntactic structures (treelets) are stored in long-term memory; phrase structure rules “may be general interface rules, or they may be simply stipulations of possible structure” (Jackendoff, 2007, p. 11). According to Jackendoff (2007), syntactic priming finds a natural explanation under such assumptions. In a bilingual speaker, we suggest that these syntactic structures stored in long-term memory are accessed in a manner that is non-selective for language. The continual activation of possible structures in language A as language B is used (in a way parallel to the activation of lexical items) leads to the gradual inclusion of non-native structures in language B. This process is presumably impeded by greater exposure to and use of a language, making a speaker’s non-dominant language more susceptible to cross-linguistic influence than the dominant one.

In our experiments, the timed grammaticality judgment task demonstrated evidence of interference. We suggest that when bilinguals judge grammaticality in one of their languages, they access possible grammatical strings in both languages, leading to greater inaccuracy and latency when the two languages conflict as to whether the sentence is grammatical or not. The hypothesis that these results reflect interference is supported by the fact that the child L2 learners (who were Spanish dominant) in Experiment 1 and the simultaneous bilinguals in Experiment 2 (who were English dominant) were slower to judge sentences in their non-dominant language. They were also slower and less accurate when the grammaticality did not match between English and Spanish. We interpret this to indicate that when bilinguals’ languages have matching syntactic structure, this facilitates recognizing that the sentence is grammatical.

As an example, consider the task faced by a Spanish-English bilingual in determining whether the NP “*car red” is grammatical or not in English. Along with the English words, the Spanish words “coche rojo” (red car) will also be activated, along with the treelets used to construct noun phrases in each language, which would include noun-adjective and adjective-noun for Spanish (6a), and adjective-noun for English (6b).

(6) a. Spanish b. English

NP NP

NP NP

N Adj Adj N

coche rojo red car

We interpret our results from Experiments 1 and 2 as evidence for non-selective access to syntax in bilinguals, given that the participants took longer to judge the grammaticality of sentences with conflicting structures, as in (6) than sentences with converging structures, whether grammatical in both languages or ungrammatical in both of them. The participants’ accuracy in judging conflicting sentences is also lower than for converging ones. We suggest that conflicting structures such as noun-adjective phrases in English and Spanish take longer to process and are more prone to error because there are a wider array of syntactic options from both languages than there are when the sentences converge in linguistic structure across languages. We found that the degree of influence as well as the direction of influence was a function of age of acquisition of the L2 in heritage bilinguals; simultaneous bilinguals experienced influence in their Spanish but not their English, whereas early L2 acquirers showed evidence of influence in their English but not their Spanish.

Our results from Experiment 1 suggest that the English of early L2 learners is modified by influence from Spanish. The results from Experiment 2 are consistent with the possibility that heritage speakers who began learning the dominant language from birth in fact possess a Spanish syntax that differs from that of a monolingual Spanish speaker (Montrul, 2008). In both cases, our participants demonstrate a syntax that appears to be more inclusive than that of a monolingual speaker in ways that are consistent with syntactic influence from the other language. Over time, this expansion of grammatical options may lead to permanent grammatical change, for the bilingual individual and perhaps even for the speech community.

References

Altarriba, J. (1990). Constraints on interlingual facilitation effects in priming in Spanish-English bilinguals. (Doctoral dissertation). Available from ProQuest Dissertations and Theses database.

Bernolet, S., Hartsuiker,R. J., & Pickering, M. J. (2013). From language-specific to shared syntactic representations: The influence of second language proficiency on syntactic sharing in bilinguals. Cognition, 127, 287-306.

Costa, A., Miozzo, M., & Caramazza, A. (1999). Lexical selection in bilinguals: Do words in the bilingual’s two lexicons compete for selection? Journal of Memory and Language, 41, 365-397

Culicover, P. W., & Jackendoff, R. (2005). Simpler syntax. New York: Oxford University Press.

De Groot, A. M. B., Dannenburg, L., & Van Hell, J. G. (1994). Forward and backward word translation by bilinguals. Journal of Memory and Language, 33, 600-629.

De Groot, A. M. B. (1992). Determinants of word translation. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 18, 1001-1018.

Dijkstra, T., Timmermans, M. & Schriefers, H. (2000). On being blinded by your other language: Effects of task demands on interlingual homograph recognition. Journal of Memory and Language, 42, 445–464.

Dijkstra,T., & Van Heuven, W. J. B. (2002). The architecture of the bilingual word recognition system: From identification to decision. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 5, 175-197.

Dussias, P. E. (2001).Sentence parsing in fluent Spanish-English bilinguals. In J. Nicol (Ed.),

One mind, two languages: Bilingual language processing. Cambridge: Blackwell, 159-176.

Duyck, W. (2005). Translation and associative priming with cross-lingual pseudohomophones: Evidence for nonselective phonological activation in bilinguals. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 31, 1340-1359

Guasch, M., Ferré, P., Haro, J. (2017). Pupil dilation is sensitive to the cognate status of words: Further evidence for non-selectivity in bilingual lexical access. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 20(1), 49-54.

Grosjean, F. (2001). The bilingual’s language modes. In J. L. Nicol (Ed.), One mind, two languages: Bilingual language processing. Malden, MA: Blackwell, 1-22.

Harsuiker, R. J., Beerts, S., Loncke, M., & Bernolet, S. (2016). Cross-linguistic structural priming in multilinguals: Further evidence for shared syntax. Journal of Memory and Language, 90, 14-30.

Hartsuiker, R. J., & Pickering, M. J., & Veltkamp, E. (2004). Is syntax separate or shared between languages? Cross-linguistic syntactic priming in Spanish-English bilinguals. Psychological Science, 15, 409-414.

Hohenstein, J., Eisenberg, J., & Naigles, L. (2006). Is he floating across or crossing afloat? Cross-influence of L1 and L2 in Spanish-English bilingual adults. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 9, 249-261.

Ionin, T., & Montrul, S. (2010). The role of L1-transfer in the interpretation of articles with definite plurals in L2-English. Language Learning, 60, 877-925.

Jackendoff, R. (1997). The Architecture of the Language Faculty, MIT Press.

Jackendoff, R. (2007). A Parallel Architecture perspective on language processing. Brain Research, 1146, 2-22.

Jackendoff, R. (2011). What is the human language faculty? Two views. Language, 87, 586-624.

Kroll, J. F., Bobb, S. C., & Wodniecka, Z. (2006). Language selectivity is the exception, not the rule: Arguments against a fixed locus of language selection in bilingual speech. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 9(2), 119-135.

Lagrou, E., Hartsuiker, R., & Duyck, W. (2011). Knowledge of a second language influences auditory word recognition in the native language. Journal of experimental psychology Learning memory and cognition. 37 (4): 952-965.

Marian, V. & Spivey, M. (2003). Competing activation in bilingual language processing: Within- and between-language competition. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 6(20, 97-115.

Montrul, S. (2002). Incomplete acquisition and attrition of Spanish tense/aspect distinctions in adult bilinguals. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 5, 39-68.

Montrul, S. (2004). Subject and object expression in Spanish heritage speakers: A case of morphosyntactic convergence. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 7, 125-142.

Montrul, S. (2008). Incomplete acquisition in bilingual speakers: Re-examining the age factor. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

Montrul, S. (2009). Knowledge of tense-aspect and mood in Spanish heritage speakers. International Journal of Bilingualism, 13, 239-269.

Montrul, S., & Bowles, M. (2009). Back to basics: Differential object marking under incomplete acquisition in Spanish heritage speakers. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 12(4), 363-383.

Montrul, S. & Ionin, T. (2012). Dominant language transfer in Spanish heritage speakers and L2 learners in the interpretation of definite articles. Modern Language Journal, 96, 70-94.

Montrul, S. & Ionin, T. (2010). Transfer effects in the interpretation of definite articles by Spanish Heritage Speakers. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 13, 449-473.

Montrul, S., & Perpiñán, S. (2011). Assessing differences and similarities between instructed L2 learners and heritage language learners in their knowledge of Spanish tense-aspect and mood (TAM) morphology. The Heritage Language Journal, 8(1), 90-133.

Montrul, S., & Potowski, K. (2007). Command of gender agreement in school-age Spanish bilingual children. International Journal of Bilingualism, 11, 301–328.

Montrul, S., & Sanchéz-Walker, N. (2013). Differential object marking in child and adult Spanish heritage speakers. Language Acquisition, 20(2), 109-132.

Pavlenko, A. & Jarvis, S. (2002). Bidirectional transfer. Applied Linguistics, 23, 190-214.

Perez-Lerouz, A. T. (1998). The acquisition of mood selection in Spanish relative clauses. Journal of Child Language, 25(3),585-604.

Rinke, E., & Flores, C. (2014). Morphosyntactic knowledge of clitics by Portuguese heritage bilinguals. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 17(4), 681-699.

Rodríguez-Mondóñeo, M. (2008). The acquisition of differential object marking in Spanish. Probus, 20(1), 111-145.

Rothman, J. (2007). Heritage speaker competence differences, language change, and input type:

Inflected infinitives in heritage Brazilian Portuguese. International Journal of Bilingualism, 11(4), 359-389.

Rothman, J. (2009). Understanding the nature of early bilingualism: Romance languages as heritage languages. Special Issue of International Journal of Bilingualism 13, 2

Sanoudaki, E., & Thierry, G. (2015). Language non-selective syntactic activation in early bilinguals: the effect of verbal fluency. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism. 18(5), 548-560.

Silva-Corvalán, C. (1994). Language contact and change: Spanish in Los Angeles. Oxford:

Oxford University Press.

Silva Corvalán, C. (2008). The limits of convergence in language contact. Journal of Language Contact, 2, 213-224.

Valdés, G. (2000). Spanish for native speakers. AATSP professional development series handbook for teachers K-16, Vol. 1. New York: Harcourt College.

Weber-Fox, C., & Neville, H. J. (1996). Maturational constraints on functional specializations for language processing: ERP and behavioral evidence in bilingual speakers. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 8, 231-256.

Zapata, G., Sánchez, L., & Toribio, A. J. (2005). Contact/contracting Spanish among Spanish heritage bilinguals in the U.S. International Journal of Bilingualism, 9, 377-396.

Appendix A

gr = grammatical in English

un = ungrammatical in English

cf = conflicting sentence (different judgment in Spanish and English)

cv = converging sentence (same judgment in Spanish and English)

Noun Phrases

npgrcf3 This news program is about our country’s economic problems.

npgrcf4 Theirs cost a lot of money.

npgrcf1 The rope was tied to the bench’s leg when we found it.

npgrcf2 I agree that Bill is a nice guy.

npuncf3 *The girl keeps the shoes red in her closet.

npuncf4 *The man has hats weird in his bag.

npuncf1 *The house of Tome is blue.

npuncf2 *The hers is the first on the street.

npuncv1 *The girl keeps shoes red the in her closet.

npuncv2 *The man has hats weird in bag his.

npuncv3 *The Tom’s house is the first on the street.

npuncv4 *The hers house is the first on the street.

npgrcv1 This news program is about the economic problems of our country.

npgrcv2 Their house cost them a lot of money.

npgrcv3 The rope was tied to a leg of the bench when we found it.

npgrcv4 I agree that Bill is a great guy.

Determiner Phrases

dtgrcf3 Our neighbor really likes to talk to people.

dtgrcf4 My cat loves attention from children.

dtgrcf1 Tigers are becoming extinct in India.

dtgrcf2 She says she wants to hear stories about the war.

dtuncf3 *She says she wants to hear story from Maria.

dtuncf4 *My friend Lisa is doctor.

dtuncf1 *In the India tigers are becoming extinct.

dtuncf2 *They will finish it the Monday.

dtuncv1 *She says she wants to the hear story from the Maria.

dtuncv2 *My friend Lisa is doctor the.

dtuncv3 *In the India tiger is becoming extinct.

dtuncv4 *They will finish it a Monday.

dtgrcv1 Our neighbor really likes to talk to the people on the street.

dtgrcv2 My cat loves attention from the children who visit us.

dtgrcv3 The tiger is becoming extinct in India.

dtgrcv4 She says she wants to hear the stories about the war.

Verb Subcategorization Phrases

vbgrcf3 The teacher allows his students to finish their homework in class. (taken out of analysis)

vbgrcf4 I would like for you to arrive on time.

vbgrcf1 We expect students to pay attention to the lecture.

vbgrcf2 The boss believes the employees to be telling the truth.

vbuncf3 *The man consents that his son watch T.V.

vbuncf4 *The woman wants that her daughter eat cake on her birthday.

vbuncf1 *His parents let that he clean the house.

vbuncf2 *They permit that their daughter drive in the snow.

vbuncv1 *The man consents his son watch T.V.

vbuncv2 *The woman wants her daughter eat cake.

vbuncv3 *His parents let he clean the house.

vbuncv4 *They permit their daughter drive in the snow.

vbgrcv1 The teacher allows that his students finish their homework in class. (taken out of analysis)

vbgrcv2 It is necessary that you arrive on time.

vbgrcv3 We expect that students pay attention to the lecture.

vbgrcv4 The boss believes that the employees are telling the truth.

WH- Questions

whgrcf3 Which computer did he buy?

whgrcf4 Which green car does she drive?

whgrcf1 Why did she call the police?

whgrcf2 What does he like with spaghetti?

whuncf3 *When is going to fix his car Sam?

whuncf4 *When is going to get dressed Sally?

whuncf1 *Why is saying that he?

whuncf2 *Why is reading those books Karen?

whuncv1 *When is going Sam to fix his car?

whuncv2 *When is going Sally to get dressed?

whuncv3 *Why is saying he that?

whuncv4 *Why is reading Karen those books?

whgrcv1 Who bought this computer?

whgrcv2 Who drives a green car?

whgrcv3 Who called the police?

whgrcv4 Who likes spaghetti?

Preposition Phrases

ppgrcf3 He is a person that is easy to talk with.

ppgrcf4 Amy spent a long time looking for her lost cat.

ppgrcf1 I am worried about it.

ppgrcf2 He walked between me and Sally down the hallway.

ppuncf3 *This glass is easy of to break.

ppuncf4 *When Robert came home, he put his backpack under of the table.

ppuncf1 *Jane replaced the plates for a bowl of fruit.

ppuncf2 *There must be more of eight people in that room.

ppuncv1 *This glass is easy to break of.

ppuncv2 *When Robert came home, he put his backpack of the table.

ppuncv3 *Jane replaced the plates at a bowl of fruit.

ppuncv4 *There must be more eight people in that room.

ppgrcv1 He is a person with whom it is easy to talk.

ppgrcv2 Amy spent a long time seeking her lost cat.

ppgrcv3 I am worried for them.

ppgrcv4 He walked with me and Sally down the hallway.

Negation Phrases

nggrcf3 Our students wouldn’t participate in this, would they?

nggrcf4 Both Sam and Sally wanted to hear them.

nggrcf1 There are no shoes in the closet, are there?

nggrcf2 No boy would want to sing this song.

nguncf3 *Nor Carlos nor Steve neither expected to see them.

nguncf4 *None adult would eat watermelon.

nguncf1 *No there are none shoe in the closet.

nguncf2 *None monkey would eat candy.

nguncv1 *Carlos nor Steve expected to see them.

nguncv2 *No adult neither would eat watermelon.

nguncv3 *No there are none shoes in the closet.

nguncv4 *None monkeys would eat candy.

nggrcv1 Our students wouldn’t participate in this, right?

nggrcv2 Neither Sam nor Sally wanted to hear them.

nggrcv3 There are no shoes in the closet, correct?

nggrcv4 No boys would want to sing this songAppendix B

Grammatical converging (16 total)

Converging: Los zapatos que la muchacha guarda en su armario son rojos.

The shoes that the girl keeps in her closet are red.

Converging: En su bolsa, el hombre tiene grandes sombreros.

In his bag, the man has big hats.

Converging: La casa que es azul es de Tomás.

The house that is blue is Tom’s.

Converging: Su casa es la primera en la calle.

Her house is the first on the street.

Converging: En América Latina el tigre se está extinguiendo.

In Latin America the tiger is becoming extinct.

Converging: El hombre quiere ver la televisión.

The man wants to watch television.

Converging: ¿Está Carlos en la reunión?

Is Carlos in the meeting

Converging: Ni Carlos ni Julio esperaba verlos.

Neither Carlos nor Julio expected to see them.

Converging: Cuando Roberto llegó a casa, puso su mochila en la mesa.

When Robert came home, he put his backpack on the table.

Converging: Mi amiga Isabelle es la doctora.

My friend Isabelle is the doctor.

Converging: Ellos van a terminarlo un lunes.

They will finish it on a Monday.

Converging: Sus padres le dejan limpiar la casa.

His parents let him clean the house.

Converging: ¿Por qué está diciendo eso?

Why is he saying that?

Converging: ¿Por qué está leyendo eso?

Why is she reading that?

Converging: Juanita substituyó los platos con un tazón de fruta.

Juanita replaced the plates with a bowl of fruit.

Converging: Tiene que haber más de ocho personas en ese cuarto.

There must be more than eight people in that room.

Grammatical conflicting (16 total)

Conflicting: La muchacha guarda los zapatos rojos en su armario.*

*The girl keeps the shoes red in her closet.

Conflicting: EL hombre tiene sombreros grandes en su bolsa.

*The man has hats big in his bag.

Conflicting: La casa de Tomás es azul.

*The house of Tom is blue.

Conflicting: En la India los tigres se están extinguiendo.

*In India the tigers are becoming extinct.

Conflicting: A la mujer le gusta que su hija coma pastel en su cumpleaños.

The woman likes that her daughter eats cake on her birthday.

Conflicting: ¿Cuando va a la reunión Carlos?

*When is going to the meeting Carlos?

Conflicting: Ningún adulto comeria sandia.

*None adult would eat watermelon.

Conflicting: No hay zapatos en el armario.

No there are shoes in the closet.

Conflicting: La suya es la primera en la calle.

*The hers is the first on the street.

Conflicting: Mi amiga Isabelle es doctora.

*My friend Isabelle is doctor.

Conflicting: Ellos van a terminarlo el lunes.

*They will finish it the Monday.

Conflicting: Ellos permiten que su hija maneje en la nieve.

*They permit that their daughter drive in the snow.

Conflicting: ¿Por qué está diciendo eso él?

*Why is saying that he?

Conflicting: ¿Por qué está leyendo eso ella?

*Why is reading that she?

Conflicting: Juanita substituyó los platos por un tazón de fruta.

*Juanita replaced the plates by a bowl of fruit.

Conflicting: Tiene que haber más de ocho personas en ese cuarto.

*There must be more of eight people in that room.

Ungrammatical converging (16 total)

Converging: *Este programa noticiero se trata de los problemas económicos de nuestro país.

*This program news is about the economic problems of our country.

Converging: *Su casa mucho costo les dinero.

*Their house a lot of cost them money.

Converging: *La soga estaba a una pierna del banco atada cuando la encontramos.

*The rope was to the bench’s leg tied when we found it.

Converging: *A nuestro vecino verdaderamente la gente en la calle le gusta hablar a.

*Our neighbor really the people on the street likes to talk to.

Converging: *A mi gato le encanta de atención los niños.

*My cat loves from attention the children.

Converging: *El en tigre India es extinguido.

*The in India tiger is extinct becoming.

Converging: *El maestro permite sus tareas en clase que sus estudiantes terminen.

*The teacher allows their homework in class that his students finish.

Converging: *Es necesario que tiempo tu llegues.

*It is necessary that time on you arrive.

Converging: *Esperamos a los estudiantes presta atencion esa lectura

*We expect to the students pay attention that lecture.

Converging: *El jefe cree que diciendo los empleados son la verdad.

*The boss believes that telling the employees are the truth.

Converging: *El es con quien una persona es facil de hablar.

*He is with whom a person it is easy to talk.

Converging: *Diana buscando su perdido gato mucho tiempo pasó.

*Diana seeking her lost cat a long time spent.

Converging: *Me por preocupalo.

*I about am worried it.

Converging: *Nuestros estudiantes participan no en esto, verdad?

*Our students participate wouldn’t in this, right?

Converging: *Ni Carlos ni Maritza ellos escuchar querían.

*Neither Carlos nor Maritza them hear wanted to.

Converging: *Ningún muchacho querría canción a cantar esto.

*None boy would want song to sing this.

Ungrammatical conflicting (16 total)

Conflicting: *Este noticiero se trata de de nuestro país los problemas económicos.

This news program is about our country’s economic problems.

Conflicting: *Suyo cuesta mucho dinero.

Theirs cost a lot of money.

Conflicting: *La soga estaba atada a la del banco pata cuando la encontramos.

The rope was tied to the bench’s leg when we found it.

Conflicting: A nuestro vecino de veras le gusta hablar a gente.

*Our neighbor really him pleases to talk to people.

Conflicting: A mi gato le encanta la atención de los niños.

*To my cat him pleases attention from the children.

Conflicting: *Tigres se están extinguiendo en la India.

Tigers are becoming extinct in India.

Conflicting: *El maestro permite que sus estudiantes terminar sus tarea en clase.

The teacher allows his students to finish their homework in class.

Conflicting: *Me gustaria para tú llegar a tiempo.

I would like for you to arrive on time.

Conflicting: *Esperamos que los estudiantes prestar atención a la lectura.

We expect students to pay attention to the lecture.

Conflicting: *El jefe cree que los empleados estar diciendo la verdad.

The boss believes the employees to be telling the truth.

Conflicting: *El es una persona que es fácil de hablar con.

He is a person that is easy to talk with.

Conflicting: *Diana pasó mucho tiempo buscando por su perdido gato.

Diana spent a long time looking for her lost cat.

Conflicting: *Me preocupa por lo.

I am worried about it.

Conflicting: *¿No estudiantes participarían en esto, verdad?

No students would participate in this, right?

Conflicting: *Tanto Carlos y Maritza quería escucharlos.

Both Carlos and Maritza wanted to hear them.

Conflicting: *No muchacho querría cantar esta canción.

No boy would want to sing this song.

Table 1

| Language profile for bilingual participants in Experiment 1 | ||

| Simultaneous bilinguals (n = 11) | Child L2 learners (n = 11) | |

| Age of first exposure

to English |

1.05 yrs (1.13) | 4.82 yrs (0.75) |

| Daily amount of time speaking Spanish | 44.5% (15.6) | 48.0% (17.3) |

| English proficiency score | 96.2% (4.8) | 93.7% (5.2) |

| Spanish proficiency scorea | 78.5% (9.9) | 86.3% (6.4) |

| Comfortable reading Spanish | 82% | 91% |

| Comfortable writing Spanish | 45% | 91% |

| Most comfortable speaking

English Spanish both languages equally |

72.7%

0% 27% |

45.4%

18.2% 36.4% |

Note: English and Spanish proficiency test scores are not directly comparable to one another. aThese scores are significantly different t(20) = -2.17, p

Table 2

| Distribution of current language exposure for bilingual participants in Experiment 1 | ||

| Simultaneous bilinguals (n = 11) | Child L2 learners (n = 11) | |

| Language spoken at home

Exclusively Spanish Predominantly Spanish Both languages equally Predominantly English |

2

3 5 1 |

2

8 1 0 |

| Language spoken in community

Spanish English Both |

1

7 3 |

6

3 2 |

| Language heard on TV/radio

Spanish English Both |

0

6 5 |

2

2 7 |

Table 3

| Mean reaction times in ms for grammatical vs. ungrammatical sentences in Experiment 1. | ||

| Language group | Grammatical | Ungrammatical |

| Monolingual | 943.81 (51.42)** | 795.76 (39.92) |

| Simultaneous bilingual | 1105.83 (81.41)* | 896.61 (88.91) |

| Child L2 learners | 1143.53 (114.63)* | 1045.46 (130.33) |

Note: Numbers in parentheses are standard errors. **p p

Table 4

| Mean error rates for grammatical vs. ungrammatical sentences for Experiment 1. | ||

| Language group | Grammatical | Ungrammatical |

| Monolingual | 7.7% (0.7) | 15.8% (1.0) |

| Simultaneous bilingual | 7.5% (1.1) | 15.6% (3.6) |

| Child L2 learners | 8.4% (1.9) | 20.7% (1.8) |

Note: Numbers in parentheses are standard errors.

Table 5

| Language profile for bilingual participants in Experiment 2

|

||

| Simultaneous bilinguals (n = 6) | Child L2 learners (n = 6) | |

| Age of first exposure

to English |

1.55 yrs (1.55) | 5.17 yrs (1.17) |

| Daily amount of time speaking Spanish | 39.5% (6.4) | 38.3% (10.3) |

| English proficiency score | 91.1% (3.9) | 92.2% (7.2) |

| Spanish proficiency scorea | 82.4% (12.3) | 86.2% (7.2) |

| Comfortable reading Spanish | 100% | 100% |

| Comfortable writing Spanish | 100% | 100% |

| Most comfortable speaking

English both languages equally |

50%

50% |

33%

67% |

Note: English and Spanish proficiency test scores are not directly comparable to one another.

Table 6

| Distribution of current Spanish exposure for bilingual participants in Experiment 2 | ||

| Simultaneous bilinguals (n = 6) | Child L2 learners (n = 6) | |

| Language spoken at homea

Exclusively Spanish Predominantly Spanish Both languages equally Predominantly English |

1

2 2 0 |

2

2 1 1b |

| Language spoken in community

Spanish English Both |

1

3 2 |

3

3 0 |

| Language heard on TV/radio

Both Spanish and English English |

3

3 |

4

2 |

aOne simultaneous bilingual lives alone. bParticipant does not live with family of origin.

Table 7

| Mean error rates for converging and conflicting sentences for each language group in Experiment 2. | ||

| Language group | Converging | Conflicting |

| Simultaneous bilingual | 14.8% (2.59) | 30.8% (2.86) |

| Child L2 learners | 13.6% (2.58) | 35.9% (3.22) |

Note: Numbers in parentheses are standard errors.

Figure Captions

Figure 1. Mean reaction times as a function of sentence type for all language groups in Experiment 1.

Figure 2. Mean error rates as a function of sentence type for all language groups in Experiment 1.

Figure 3. Mean reaction times on converging and conflicting sentences as a function of grammaticality in Experiment 2.

Figure 4. Mean reaction times as a function of sentence type for both language groups in Experiment 2.

Figure 5. Mean error rates on converging and conflicting sentences as a function of grammaticality in Experiment 2.

*

*

Cite This Work

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing stye below:

Related Services

View allRelated Content

All TagsContent relating to: "Linguistics"

Linguistics is a field of study that explores the science of languages and their structures. Linguistics covers how factors such as history, culture, society, and politics, amongst other elements, can have an impact on language.

Related Articles

DMCA / Removal Request

If you are the original writer of this dissertation and no longer wish to have your work published on the UKDiss.com website then please: