Audience Intentions to Revisit Live Theatre Performance

Info: 9242 words (37 pages) Dissertation

Published: 10th Dec 2019

Tagged: Theatre

TITLE

The Audience and the Live Show: a closer examination of the audience’s intentions to revisit a live theatrical performance

ABSTRACT (approximately 200 words-5% grade)

The purpose of this study is to explore the ontological and epistemological underpinnings of the concept audience intention to revisit a theatrical performance. Assess an audience’s intention to revisit a live entertainment performance. Define and clarify those factors to help management in their decision-making process. Encourage further creative endeavors with more emphases on details that strengthen the audience’s re-visit intentions. Given that audience satisfaction, gratification and repeat attendance are measures of success used by entertainment companies, and given that audience evaluation of quality is recognized in the literature (Boerner and Renz, 2008) as equivalent, in certain instances, to expert measurement of quality, then the present findings go some way towards validating audience experience as a measure of quality in live theatrical performances.

Key words: Entertainment, Audience, Revisit, Satisfaction, Theatrical, Gratification

INTRODUCTION

Pearce (2008) defined tourism entertainment as structured and managed situations designed for a predominantly visitor audience, which include cultural shows, dance performances, theme park presentations, fun guided tours and film and video presentations tailored exclusively for visitors. Entertainment experiences are becoming increasingly important in area of theatrical events and festivals, which are prime manifestations of the experience economy (de Geus, Richards, Toepoel, 2015). However, research on entertainment experiences has generally been concerned with economic impacts and visitor motivations (Gursoy, D., Kim, K., & Uysal, M., 2004). Unique and memorable entertainment experiences are an important part of consumers’ lives and arguably the best way for suppliers to gain competitive advantage (Pine & Gilmore, 1998, 1999). As a result, concepts such as the entertainment “experience economy” and entertainment “experience management” have been widely discussed (Boswijk, Thijssen, & Peelen, 2009; Nijs, 2003; Scott, Laws, & Boksberger, 2009).

Creative entertainment experiences and events generate both civic pride and substantial revenues for communities that host local, regional, national, or international events by serving as the event’s host destination. The is found to be true in previous works Goeldner and Richie (2012) found that events provide local communities with economic wellbeing in a region (Chhabra, Sills, & Cubbage, 2003; Dwyer, Forsyth, & Spurr, 2005; Lim & Patterson, 2008; McHone & Rungeling, 2000), indirect spending’s on hospitality products and services (Thrane, 2002) or through their indirect effect on higher employee income generated by tourist spending (Daniels, 2007; Daniels, Norman, & Henry, 2004). Grove et al. (1992) framed the event service experience as a drama containing four critical elements:

- Actors, employees, who are the personnel contributing to the services

- Audience, participants, who are the audience and customers

- Set or venue, which is the service setting or physical surrounding

- The show/story, process of story assembly, which is the service performance itself

Grove et al. (1998) extensively examined the entertainment market by analyzing tourists’ satisfactory and unsatisfactory experiences with entertainment events offered. Lacher and Mizerski (1994) found support in a relationship between satisfaction and intention to re-experience a performance and repurchase intentions, which can be summarized as audience behavior.

One of the main goals of a theatrical performance experience of a destination is to boost the local tourism industry, whereas that of stakeholders is profitability (Song & Cheung, 2010). In previous studies, consumer satisfaction has been linked to higher business profits through loyalty (Alegre and Juaneda, 2006; Gupta et al., 2007). Hence, there is an urgent need to study tourist satisfaction with and loyalty towards theatrical performance (Song & Cheung, 2010).

This study proposes that the audience would play a key factor in the role in helping to understand entertainment in better detail. Entertainment is reliant on the audience and their appreciation of the form. Entertainment is an expansive topic and has many forms to appease the audience. Some forms of entertainment could bore some members of the audience and with that response they may not desire to revisit that form of entertainment. If the entertainment fails to entertain them, but so long as it entertains some (and meets other criteria), it still does remain entertainment (Bates & Ferri, 2010). The entertainment focus being addressed here is the specific in relation to investigating theatrical experiences planned and performed with principally visitors in mind (Pearce, 2008).

Authors Bates & Ferri (2010), put forth the notion of developing a more objective definition can help unify and advance the field of entertainment studies. Their assessment is that entertainment involves communication featuring external stimuli; it provides pleasure to some people, though not of course to everyone; and it reaches a generally passive audience. (Bates & Ferri, 2010). The further meaning of entertainment is implicit in the current approach is that the audience as a whole is passive, at least in a physical sense of not participating in the core activity (Pearce, 2008). This distinction thus marks off entertainment related tourism from ‘participatory activities’ such as bungy jumping or white-water rafting (Pearce, 2008). This passivity has the implication that the approaches to tourist behavior built on an embodied, experience constructing view of active travelers may be less relevant to tourism and entertainment analyses than those approaches deriving from gaze and staging metaphors (Goffman 1959; Urry 1990; Franklin 2003).

The purpose of this study is to explore the ontological and epistemological underpinnings of the concept audience intention to revisit a theatrical performance. This paper proposes factors that help create a construct that can be used to measure the audience’s intentions to attend a repeat performance of a live theatrical creative entertainment, which will summarize as the ‘show’. The show is foundational in the sector of entertainment industry.

Perhaps the most compelling rationale for developing the nexus between tourism and entertainment lies in connecting the world of tourism research to the larger and increasingly complex world of entertainment provision and industry (Pearce, 2008). On a global scale, there are several key powerful corporations providing public entertainment options to millions of consumers through vertically integrated businesses (Pearce, 2008). Some of these corporations have influences which penetrate such areas as film, theme parks, airlines, hotels and the digital media, thus providing them with the leverage to shape and influence public taste and knowledge (Pearce, 2008).

Studies in cultural tourism could well be embellished by a fuller consideration of these invisible hands of influence as manifested in certain forms of tourism entertainment (Harris 2004). The owners, managers and controllers of entertainment are a group of interest-these are the people who both decide what will be offered and who pay the wages of others from the tourist income (Pearce, 2008). A second group of interest is the performers or talents who enact and embody the themes and presentations which the tourists come to watch (Pearce, 2008). The nature and characteristics of audiences are a third focus of interest when studying entertainment (Pearce, 2008). Additionally, in describing audience composition a particular interest of tourist researchers lies in assessing and understanding audience response (Pearce, 2008). The key variables for audience assessment here include satisfaction and gratification.

Special attention is given to the distinction between different theoretical roles of satisfaction and gratification in entertainment experience. On the one hand, the experience of moods and emotions per se can be satisfying, including for instance individuals’ sense of pleasure, excitement, or sentimentality during media exposure (Bartsch (2012). On the other hand, Bartsch (2012) proposed that emotional media experiences can also be gratifying in an indirect manner in that they contribute to the gratification of individuals’ social and cognitive needs. The aim of the literature search is to provide a systematic assessment of both direct and indirect forms of audience satisfaction and gratifications live theatrical entertainment. These concepts and ideas were used in the search parameters for this study and the foundation for the building of the literature review.

LITERATURE REVIEW (approximately 2400 words-40% grade)

There are many types of tourism entertainment in the tourism industry. According to the 2012 U.S. Census Bureau, approximately 225 million adults attended leisure activities such as concerts, musicals, or art festivals. Their data suggested that in 2008 and 2009, leisure activities generated an estimated total spending of $897 billion along with $14.5 billion solely on live entertainment. It was also reported that the estimated total revenues generated by businesses associated indirectly with these entertainment events exceeded $188 billion. According to various sources from Forbes, Wall Street Journal, Ticketmaster and other, those numbers are on the steady incline. Consequently, entertainment events should be recognized as having great potential for generating financial benefits for venues (e.g., stadiums, arenas, or performing arts centers) and also for other hospitality business segments (e.g., restaurants, lodging, shopping facilities, and/or transportation) (Kim, Tucker, Erinn, 2016).

The literature related to theatrical performance is rooted in the tourism entertainment research (Song & Cheung, 2010). In the selection of the articles for the literature review, there was a concerted effort and focus on the more recent research materials (2010 to 2010) that focused on the audience satisfaction & loyalty, their entertainment value and their intention to revisit. As research progressed, there was older articles selected and used that reinforced the contemporary concepts. The studies of Oliver and Petrick, J. F., Morais, D. D., & Norman, W. C. were also included. A broadening of the scope of academic literature investigation to include this entertainment visitor ‘re-visit’ idea was discovered in various useable articles.

Theatrical Performance

According to Hughes (2000), entertainment includes live performances of music, dance, shows, and plays, going to the cinemas, clubs, discos and sport matches, watching television, playing computer games, and listening to CDs. Hughes and Allen (2008) defined entertainment as live performances of plays, music, dance and the like that are different from the fine arts as experienced in developed, long established tourist destinations. Pearce (2008) identified common and noteworthy characteristics of tourism entertainment from a range of micro-cases, and defined tourism entertainment as structured and managed situations designed for a predominantly visitor audience.

One definition of theatrical performance is ‘a performance of a play.’ In the present study, theatrical performance refers to large-scale live performances staged indoors or outdoors, that are predominantly designed for tourists (Song & Cheung, 2010). Chen et al. (2008) analyzed inbound tourist satisfaction and future revisit intention regarding a theatrical production. They found a significant relationship between the three factors and tourist satisfaction and revisit intention, respectively (Song & Cheung, 2010). However, little is found about the attributes of theatrical performances in the tourism research (Song & Cheung, 2010). Because of the lack of research means that there are other areas of study can be used to help fill in the gaps. The hospitality field has some great example of work to measure theatrical events. For instance, Hede et al. (2004) measured eight attributes of a theater event, ‘storyline’, ‘stage work’, ‘costumes’, ‘acting and singing’, ‘ambience of the theater’, ‘service at the theater’, ‘value for money’ and ‘vision from the seats’, to test a conceptual framework that included personal values, satisfaction and post-consumption behavioral intentions. They found that with the exception of ‘vision from the seats,’ these attributes were significantly related with tourist satisfaction (Song & Cheung, 2010).

Entertainment Satisfaction

Theories on entertainment psychology have tended to focus on the response of enjoyment, exploring such questions as why viewers enjoy some types of entertainment genres, portrayals, or behaviors over others, and why different viewing situations and mood states lead individuals to select and enjoy different types of entertainment offerings over others (Oliver & Bartsch, 2010). The focus of enjoyment is understandable—after all, the word ‘‘entertainment’’ conjures up thoughts of amusement, thrills, relaxation, and diversion (Oliver & Bartsch, 2010). Satisfaction as used in the hospitality industry studies and methodologies describe the guest’s positive reaction to stimuli, which can be categorized as satisfaction. Satisfaction is defined as post-consumption evaluation concerning a specific product or service (Westbrook and Oliver, 1991), and proposed to be one of the key judgments that tourists make regarding a tourism service. Hence, it is a well-established, longstanding focus marketer attention (Yuksel and Yuksel, 2002).

Author Zillmann (2000) proposed a theory on the behavior of an audience. He suggests the Affective Disposition Theory, in which audience members morally assess a character’s behavior and either approve or disapprove it, when they watch a performance or show. The concept of satisfaction being interpreted differently by each individual, the definitions given are quite varied (Petrick, Morais, & Norman, 2001). Satisfaction is conceptualized as cognitive and affective reactions to a certain experience or form of consumption (Rust and Oliver, 1994). The cognitive component of satisfaction is based on Lewin’s (1938) expectancy-disconfirmation theory (Oliver, 1980; Churchill and Surprenant, 1982; Tse and Wilton, 1988; Yi, 1990). More specifically, satisfaction is derived when positive disconfirmation occurs (Park, J., & Jang, S., 2014). According to the Oliver (1980) model, feelings of satisfaction arise when consumers compare their perceptions of a product’s performance with their expectations. Thus, if perceived performance is greater than expectations (termed a positive disconfirmation), the consumers are satisfied. Inversely, if the perceived performance falls short of expectations (i.e., a negative disconfirmation) the customer perceives dissatisfaction (Park, J., & Jang, S., 2014). This subjective assessment of disconfirmation causes satisfaction-related emotions, such as pleasure or excitement (Oliver, 1993). Satisfaction includes two different dimensions – overall evaluation of the experience and emotional response after consumption (Oliver, 1999).

Entertainment Gratification

The idea that gratification can be derived from the experience of moods and emotions per se is perhaps most evident in Mood Management Theory (Zillmann, 1988). Mood Management Theory assumes that individuals prefer an intermediate level of arousal that is experienced as pleasant (Bartsch, 2012). In addition to balanced arousal, mood management theory highlights the gratification of positive affective valence, and the gratification associated with the absorption potential of strong emotions that can help distract individuals from negative thoughts, which is best described in the work of Knobloch-Westerwick, (2006). The gratification of feelings evoked by sad and tragic entertainment has been more puzzling to explain, specifically given the absence of just or happy endings (Bartsch, 2012). Oliver (1993) proposed an explanation based on the concept of meta-emotion (i.e., evaluative thoughts and feelings about emotions). Oliver (1993) predicted and found that ‘‘feelings of sadness elicited from viewing tearjerkers can be interpreted as pleasurable sensations among many viewers’’ (p. 336). A similar argument was made by Mills (1993) who interpreted the appeal of tragedy in terms of positive attitudes toward empathic sadness.

Entertainment research has accumulated an impressive body of evidence supporting the assumption that affective experiences can be gratifying for media users, including both the immediate gratification derived from rewarding feelings, and the more indirect but not less significant role of affect in the gratification of social and cognitive needs (Bartsch, 2012). Bartsch (2012) categorized at least six theoretically distinct factors can be identified that seem to contribute to entertainment gratification.

Three of the factors are related to the experience of emotions per se:

1) positive affect can clearly be gratifying, as assumed for example in theories of mood management and affective disposition;

2) arousal is an important theoretical element in models of mood management, sensation seeking, and excitation transfer; and

3) empathic sadness has been related to entertainment gratification in models of meta- emotion, and empathic attitudes.

The second set of gratification factors is related to social and cognitive processes that can be stimulated by emotional media experiences:

4) social relationship functions of shared emotions have been assumed with regard to courtship functions of horror films;

5) emotional engagement with characters is highlighted in models of affective disposition, transportation, involvement, identification, narrative engagement, and para- social relationships; and

6) the role of emotions in stimulating (self-)reflection is emphasized in models of aesthetic experience and social comparison.

Recent conceptualizations of entertainment as an intrinsically rewarding activity (Oliver & Bartsch, 2010; Sherry, 2004; Tamborini et al., 2010; Vorderer, Steen, & Chan, 2006) have provided a useful and parsimonious formula that covers both aspects of entertainment gratification, that is, rewarding feelings as well as psychosocial functions of entertainment. Through the lens of an intrinsic motivation framework (cf., Csikszentmihalyi, 1990; Ryan, Huta, & Deci, 2008), media experiences are entertaining to the extent that the affective, cognitive, and social aspects of the experience are gratifying in and of themselves, independent of extrinsic rewards.

Servicescape Quality

Servicescapes are sites for commercial exchanges and are produced with attention to both substantive and communicative staging (Arnould, Price, & Tierney, 1998). Berry, Wall, and Carbone (2006) proposed to measure the quality of a servicescape using clues embedded in visitors’ experiences with its service systems. Berry et al. (2006) have explained how a service system can be categorized as containing such functional, mechanical or human clues. Service experience evaluation then reflects a customer’s satisfaction and gratification about their entire service encounter (Dong, Siu, 2013).

Since visitors are intended to interact extensively with servicescape two audience predispositions moderate the relationship between the servicescape elements as a whole and total service satisfaction (Wakefield, Blodgett, 1996). An audience’s central role in forming experiential responses to various kinds of stimuli is not only influenced by their prior knowledge, individual differences, goals and predispositions, but also by the peripheral elements, regardless of the substantive or communicative staging of the servicescape (Wakefield, Blodgett, 1996). In addition, the interaction of audience predispositions with servicescape elements helps explain the customer and service provider co-production process in service provision (Wakefield, Blodgett, 1996).

The impact of the perceived primary service on visitors’ satisfaction is by far greater than the impact of the servicescape, as indicated by more significant individual factors and higher b-values of the variables pertaining to the primary service (Jobst, Boerner 2015). To summarize, servicescape is confirmed as a relevant determinant of customer satisfaction in the venue when done as a correlation with an entertainment event. However, if analyzed in isolation (as was done in the literature of Jobst and Boerner), its relevance is likely to be overestimated. Because of the issue factors will moderate the relationship between primary entertainment expereince and servicescape, respectively, and overall audience satisfaction (Jobst, Boerner 2015). The study of Jobst and Boerner determined that the audience’s motivation to attend a theatrical performance turned out to be significant moderators when evaluating the servicescape quality. Their study also discovered that, neither audience’ lifestyle nor their individual personalities were significant moderators. To conclude, the identified main effects of entertainment production (i.e. the perceived artistic quality, followed by visitors’ emotional and cognitive response to the performance) and servicescape (i.e. seating and view, other customers’ behavior) appear to be relatively robust (Jobst, Boerner 2015).

Revisit Intention

Tourist revisit intention is commonly measured by three indicators: intention to continue buying the same product, intention to buy more of the same product and willingness to recommend the product to others (Hepworth and Mateus, 1994). In the theatrical performance research, Chen et al. (2008) measured tourist loyalty towards theatrical performance using two indicators: would you recommend the theatrical performance you have seen to your friends and relatives, and would you watch the same theatrical performance in the future? They found that inbound tourists were willing to revisit the same theatrical performance and to recommend it to others.

Conflicting Evidence

While there has been a considerable amount of research conducted on the revisit intention of a tourist, there was a notable study by Petrick showing an audience can act differently. Petrick et al. (2001) study examined tourist intention to revisit an entertainment destination, live theater entertainment, and take advantage of an entertainment package again. He discovered that past behavior, satisfaction and perceived value are not good predictors of intention to revisit live theater entertainment. This idea suggests that guests are not willing to try a new form of entertainment, but instead just re-visit a form of entertainment that they are previously familiar with.

Discovering Research Gaps (approximately 1000 words-30% grade). Apply assignment 4.

Entertainment can be a board area of study. It will require more academic institutions to encourage the development scholar who continue to the push the boundaries of knowledge in the field. It will also be necessary for using established methodologies from other fields to help define measurement in the entertainment field. The more universally accepted methodologies applied to the entertainment to more traction it will gain as a full formed and respected area of scholarly pursuit.

A substantial literature documents the effects that repeated exposure to stimuli have on affective judgements of those stimuli (Bornstein, 1989; Zajonc, 1968). Exposure research has examined effects of exposure on initially affective, meaningful stimuli (e.g., written arguments, music, live performance) (Witvliet & Vrana, 2007). As Bornstein (1989) has argued, this line of research is important because most stimuli people attend to are motivationally and affectively meaningful. The gap that is most present in the literature is in the gap deeper understanding of reasons why an audience would revisit a live theatrical performance. There have been various local and specific entertainment studies done but these are few. One such study by Song, H., & Cheung, C. (2010) lamented that there is gap in knowledge about tourist satisfaction and loyalty related to theatrical performance. They even went an expressed a further suggestion that with focus study that they performed, those results would only be applicable to the mainland China and would not be generalized for international audiences. Another limitation that they pronounced was that were unable to differentiate in the data collected from the visitors. That study was unable to determine the whether the attending audience were tourists or attending the event because it was a local leisure activity. They believe that leisure visitors and tourists perhaps will have different satisfaction levels with various theatrical performance attributes.

Conversely, there is wide and various amount of literature and studies on the re-visit factors in other sectors of the hospitality & tourism industry. There is nowhere near the robust amount of research conducted done on the reason why an audience would return to a live theatrical performance they have already viewed. There had been research conducted on the many different factors regarding the audience and one of the comprehensive outline of the audience can be found in The Theater of Plautus: Playing to the Audience. This book focus in on how to enhance the experience of the performance for the audience but doesn’t touch upon the concept of creating an atmosphere so that audience desire to return and see the same performance again.

Objective Definitions

Authors Bates & Ferri (2010), put forth the notion of developing a more objective definition can help unify and advance the field of entertainment studies to help close this gap in research. Their assessment is that entertainment involves communication featuring external stimuli; it provides pleasure to some people, though not of course to everyone; and it reaches a generally passive audience. (Bates & Ferri, 2010). The current less-defined objectives are hindering scientific progress and therefor a concerted effort should be made to increase conscience on objective definitions. The academic studies for entertainment are not as mature as other fields and still have much more room to grow. Having an objective viewpoint will help in understanding the live theatrical audience re-visit intentions in more depth.

METHODOLOGY

The study looks to draw attention to qualitative differences in the types of live theatrical entertainment experiences that contribute to gratification and satisfaction evaluation. This is a proposition study, so the measurements will need to be refined by a group in two steps. To determine the most prominent dimensions in individuals’ experience of emotional gratification and satisfaction, a combination of qualitative and quantitative research methods was utilized.

The first phase of the data collection will focus on qualitative interviews, conducted at the conclusion of a live theatrical performance. To broaden the scope of theoretical assumptions about the role of the audience in entertainment gratification and satisfaction, qualitative interviews were conducted concerning the individuals’ experience of the live theatrical performance. During this step, researchers will acquire data from feedback from face-to-face interviews. This method would let respondents explain in their own words why it is gratifying and satisfying for them while they use their own natural language in the statements. As a form of qualitative research which may be seen as akin to the humanities tradition of providing an informed critique, this tactic can be insightful and draw on other traditions of artistic and symbolic analysis (Pearce, 2008).

The interview feedback will be used to establish a set of “descriptions” need to ask more astute questions for a follow up quantitative survey. This breakdown can occur using a coding system.

(1) DATA OPEN CODING: Open coding aims to identify the discrete concepts or the building blocks of the data, with a focus on the nouns and verbs used to describe a specific conceptual world (Bakir & Baxter, 2011; Daengbuppa et al., 2006). After every interview and observation, the field notes were analyzed and open coded before moving to the next interview (Bakir & Baxter, 2011). The feature of analysis can be a sentence, paragraph, an episode or an observation (Daengbuppa et al., 2006).

(2) AXIAL CODING: The next phase is Axial coding, the open codes which seem interconnected were grouped together to generate tentative statements of relationships among phenomena (Daengbuppa et al., 2006).

(3) SELECTIVE CODING: Selective coding was used to integrate and develop the into concepts for categories to analyze.

Once the coding is complete, a panel group of experts will be created to determine the questions to ask an audience for an online follow-up survey and the second phase can begin.

In the second phase, a series of questionnaire studies was conducted using a pool of statements derived from the qualitative interviews. The panel of experts will create an online questionnaire to follow up with those audience members who gave the post-performance interviews. The online questionnaire data will be used to analyze the dimensions in individuals’ emotional gratifications and satisfaction. A recent set of scales to assess gratifying entertainment experiences developed by Oliver and Bartsch (2010) includes measures of fun, suspense, and appreciation (i.e., moving and thought-provoking experiences). These measurements will be useful in breaking down the general entertainment factor into qualitatively different facets of entertainment experience.

The online survey questions will be of a quantitative approach. The refined measurements for the online survey would ask more focused questions, using a 7-point Likert scale on Quality of Performance, Perceived Value and Atmospheric Quality. To arrive at a more comprehensive understanding of the appeal and function of live theatrical entertainment, it is vital to enhance the detail with which these aspects of entertainment experience can be measured and described. This mixed mode method will give the research a greater understanding of the  data and enhance the measurement validity factors.

data and enhance the measurement validity factors.

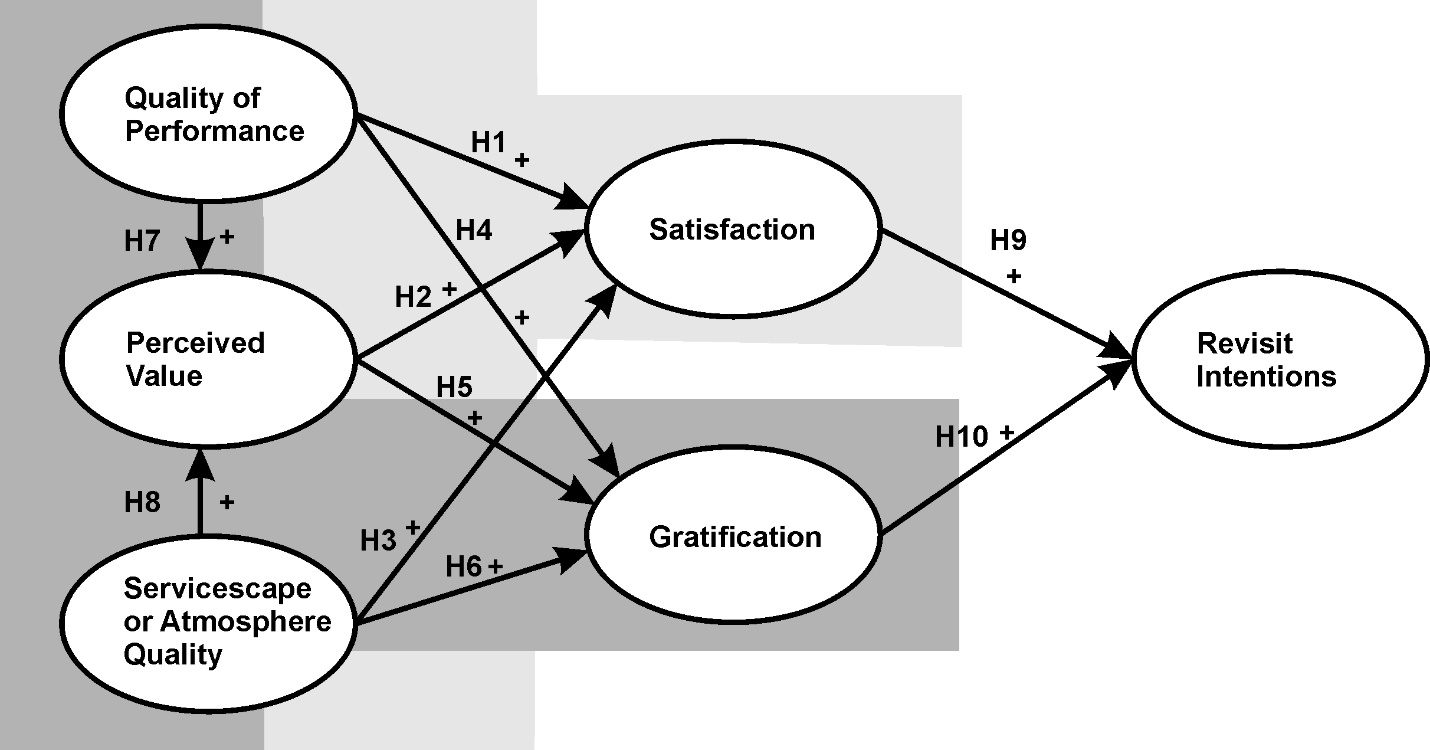

Figure 1: Model on evaluation of revisit intentions

Hypothesis (Figure 1)

Quality of Performance

According to Oliver (1980) model, feelings of satisfaction arise when consumers compare their perceptions of a product’s performance with their expectations. Thus, if perceived performance is greater than expectations, then consumers are satisfied. Conversely, if one’s perceived performance is less than his or her expectation, negative disconfirmation (dissatisfaction) occurs.

H1: Perceived quality of performance increases audience member’s satisfaction.

The role of the employee or performer goes beyond not only understanding the level of service intended by the organization and expected by the audience, but also understanding that his or her role as a facilitator for a successful service encounter will be invaluable to the attendees’ overall gratification and event experience (Kim, Tucker, Erinn, 2016).

H4: Perceived quality of performance increases audience member’s gratification.

Servicescape/Atmosphere Quality

Venue managers may consider utilizing their venue employees who traditionally perform utilitarian functions, by increasing their audience interaction which may promise a high payoff in terms of repeat business and higher spending on ancillary items (Kim, Tucker, Erinn, 2016). The “performance of staff/facility” otherwise known as the “front of house” should not be overlooked since these elements suggest implementable recommendations for managing venues.

H3: Perceived quality of Servicescape/Atmosphere increases audience member’s satisfaction.

Visitors’ satisfaction with the substantive staging of a servicescape should therefore positively predict their evaluation of the service experience, since servicescape elements have been shown strongly to influence their cognitive and affective responses (gratification) toward a service encounter (Lin, 2004; Mason & Paggiaro, 2012).

H6: Perceived quality of Servicescape/Atmosphere increases audience member’s gratification.

Perceived Value and Satisfaction

Entertainment management should not only be concerned with satisfying visitors but also need to stress quality at a good price (perceived value) to an audience. This finding is similar to that of Woodruff (1997), who contends that the measurement of consumer satisfaction should be accompanied by a measurement of perceived value to better understand consumers’ perceptions.

H2: Perceived value of the performance increases audience member’s satisfaction.

Perceived Value and Gratification

Perceived value has been defined as “the consumer’s overall assessment of the utility of a product based on perceptions of what is received and what is given” (Zeithaml 1988, p. 14). In her definition, Zeithaml (1988) identified four diverse meanings of value: (1) value is low price, (2) value is whatever one wants in a product, (3) value is the quality that the consumer receives for the price paid, and (4) value is what the consumer gets for what he or she gives. She proposed that high levels of perceived value will result in re-purchase and ultimately in higher levels of customer gratification.

H5: Perceived value of the performance increases audience member’s gratification.

Quality of Performance and Perceived Value

Live performances are aesthetic experiences due to the rich sensory input needed; consequently, audience satisfaction needs to be measured taking these factors into consideration (Minor, Wagner, Brewerton, & Hausman, 2004).

H7: Perceived quality of performance increases audience member’s perceived value.

Servicescape/Atmosphere Quality and Perceived Value

The overall evaluation of a venue visit seems to depend on both the perceived artistic quality (i.e. staging, play, artistic quality) and visitors’ individual emotional and cognitive reaction to the performance (Jobst & Boerner, 2015). Generally speaking, it can be concluded: the better visitors evaluate the artistic quality and the more intensive their emotional and cognitive response to the performance, the better they evaluate their overall theatre visit (Jobst & Boerner, 2015). This study results showcased that there is high relevance of the interaction between audience and venue.

H8: Perceived quality of servicescape/atmosphere increases audience perceived value.

Satisfaction

Oliver’s 1980 article proposes a ‘satisfaction assessment’ paradigm. Simply stated, Olive’s satisfaction assessment paradigm studies an audience’s satisfaction and will have a positive influence on the audience intention to revisit.

H9: Satisfaction has a positive influence on revisit intentions.

A strong, positive relationship exists between gratification the intention to revisit.

H10: Gratification has a positive influence on revisit intentions.

Expected Implications (HMG 6586)

This study expects to find at least three major findings emerged from the hypothesis testing. First, similar to past research, previous results suggest that satisfaction (Barsky, 1992), and perceived value (Jayanti, Ghosh, 1996) can be used to predict entertainment travelers’ intentions to revisit an entertainment activity. I believe that the best predictor of entertainment audience intentions to revisit is a high satisfaction of the audience member.

The research of this study, will be conducted on the specific focused area of the ‘live theatrical stage entertainment’. Examples of these tourist destination live theatrical entertainment would be “Walt Disney World’s Hoop-Dee-Do review”, “Sleuth’s Dinner Theatre”, or “Medieval Times”, just to name a few. All of these established shows date originated in the 1980’s. The implications derived from this study’s results would help in the development of new live performances that target the revisit intentions of the audience member(s).

Further implications would be to determine the best use of entertainment resources, to encourage audience members to revisit the show. Decision-makers and entertainment managers can apply these resources more accurately, with the goal of creating a profitable and sustainable ‘show’.

Another focus of this study will help in education of new entertainment managers while also filling some of the gaps in academic literature regarding the revisit intentions for live theatrical entertainment.

Conclusion

The purpose of this study is to explore the ontological and epistemological underpinnings of the concept audience intention to revisit a theatrical performance. This paper proposes factors that help create a construct that can be used to measure the audience’s intentions to attend a repeat performance of a live theatrical creative entertainment, which will summarize as the ‘show’. Given that audience overall satisfaction, gratification and repeat attendance are measures of success used by entertainment companies, the audience’s evaluation of quality is recognized in the literature (Boerner and Renz, 2008) as an equivalent to expert measurement of quality. The study’s findings go some way towards validating audience experience as a true measurement of overall quality.

The results of this study also shed light on the types of affective responses elicited by entertainment preferred by individuals reporting high levels of satisfaction and gratification. Both satisfaction and gratification can be measured from the audience’s detailed assessment of the quality of the performance, their perceived value and the servicescape/atmospheric quality. As one might expect, higher satisfaction scores were associated with the greatest affinity for entertainment provoking sentiments that might be described as ‘‘fun’’ (e.g., pleased, amused, entertained), whereas higher gratification scores were associated with preferences for entertainment associated with more meaningful and emotional experiences (e.g., thoughtful, pensive, empathetic).

This study’s findings are expected to contribute to the understanding of distinctive types of live entertainment customers (Grove et al., 1998). The gap in research suggest that there should be a distinct effort to determine if the audience is there for tourism or leisure. By understanding the base associated on the audience member might help venue managers. Venues would be able to use this data to create a competitive marketing advantage in the entertainment event field. Implications for theater operators can be given to increase its revenue or even enhance audience loyalty.

It is my hope that future research will also consider a broader range of measurement techniques than was employed in these studies in audience’s reactions. This tactic makes sense in the context of initially identifying the diversity of audience responses. Extending the conceptualization of entertainment gratifications in order to differentiated further from satisfaction, which would be a particularly fruitful direction for research. Future research would be wise to include the addition of technological measuring devices such as behavioral indicators of audience response (e.g., facial expression, physiological data) or data-collecting techniques (e.g., smart watches) to tap into cognitive responses. The data gathered from those devices would certainly add and even verify the findings obtained here.

By recognizing that entertainment can be both fun and meaningful, perhaps researchers will be in a stronger position to explore the gratifications of entertainment that provide an audience with not only pleasure, but also with insight about human compassions and vulnerabilities.

References

Alegre J., Juaneda C. (2006). Destination loyalty: Consumers’ economic behavior. Annals of Tourism Research 33(3): 684–706.

Arnould, E. J., & Price, L. L. (1993). River magic: Extraordinary experience and the extended service encounter. Journal of Consumer Research, 20(1), 24-45.

Bakir, A., & Baxter, S. G. (2011). “Touristic Fun”: Motivational Factors for Visiting Legoland Windsor Theme Park. Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management, 20(3-4), 407- 424.

Bates, S., & Ferri, A. J. (2010). What’s entertainment? Notes toward a definition. Studies in Popular Culture, 33(1), 1-20.

Barsky, J. D. (1992). Customer satisfaction in the hotel industry: meaning and measurement. Hospitality Research Journal, 16(1), 51-73.

Bartsch, A. (2012). Emotional gratification in entertainment experience. Why viewers of movies and television series find it rewarding to experience emotions. Media Psychology, 15(3), 267-302.

Berry, L. L., Wall, E. A., & Carbone, L. P. (2006). Service clues and customer assessment of the service experience: Lessons from marketing. The Academy of Management Perspectives, 20(2), 43-57.

Boerner, S., & Renz, S. (2008). Performance measurement in opera companies: Comparing the subjective quality judgements of experts and non-experts. International Journal of Arts Management, 10(3), 21-37.

Bornstein, R. F., Kale, A. R., & Cornell, K. R. (1990). Boredom as a limiting condition on the mere exposure effect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 58(5), 791-800.

Boswijk, A., Thijssen, T., & Peelen, E. (2009). The Experience Economy: A New Perspective. Amsterdam: Pearson Education.

Daengbuppha, J., Hemmington, N., & Wilkes, K. (2006). Using grounded theory to model visitor experiences at heritage sites: Methodological and practical issues. Qualitative Market Research: An International Journal, 9(4), 367-388.

Chhabra, D., Sills, E., & Cubbage, F. W. (2003). The significance of festivals to rural economies: Estimating the economic impacts of Scottish Highland Games in North Carolina. Journal of Travel Research, 41(4), 421-427.

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1990). Flow: The psychology of optimal experience. New York, NY: Harper Collins.

Daniels, M. J. (2007). Beyond input-output analysis: Using occupation-based modeling to estimate wages generated by a sport tourism event. Journal of Travel Research, 43(3), 75–82.

Daniels, M. J., Norman, W. C., & Henry, M. S. (2004). Estimating income effects of a sport tourism event.Annals of Tourism Research, 31(1), 180–199.

Dong, P., & Siu, N. Y. M. (2013). Servicescape elements, customer predispositions and service experience: The case of theme park visitors. Tourism Management, 36(6), 541-551.

Dwyer, L., Forsyth, P., & Spurr, R. (2005). Estimating the impacts of special events on economy. Journal of Travel Research, 43(4), 351–359.

Geus, S. D., Richards, G., & Toepoel, V. (2016). Conceptualisation and operationalisation of event and festival experiences: creation of an event experience scale. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 16(3), 274-296.

Grove, S. J., Fisk, R. P., & Bitner, M. J. (1992). Dramatizing the service experience: a managerial approach. Advances in services marketing and management, 1(1), 91-121.

Finn M., Elliott-White M., Walton M. (2000). Tourism and Leisure Research Methods: Data Collection, Analysis, and Interpretation. Longman: Harlow, England.

Franklin, A. (2003). Tourism: An Introduction. London. Sage.

Goeldner, C. R., & Ritchie, J. B. (2012). Tourism: principles, practices, philosophies (No. Ed. 12). John Wiley and Sons, Inc.

Goffman, E. (1959). The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life. New York. Doubleday.

Gupta S., McLaughlin E., Gomez M. (2007). Guest satisfaction and restaurant performance. Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly 48(3): 284–298.

Gursoy, D., Kim, K., & Uysal, M. (2004). Perceived impacts of festivals and special events by organizers: an extension and validation. Tourism Management, 25(2), 171–181.

Harris, D. (2004). Key Concepts in Leisure Studies. London. Sage.

Hede A, Jago L, Deery M. (2004). Segmentation of special event attendees using personal values: relationships with satisfaction and behavioral intentions. Journal of Quality Assurance in Hospitality and Tourism 5(2/3/4): 33–55.

Hepworth M, Mateus P. (1994). Connecting customer loyalty to the bottom line. Canadian Business Review 21(4): 40–44.

Hughes H. (2000). Arts, Entertainment and Tourism. Butterworth Heinemann: Oxford.

Jayanti, R. K., & Ghosh, A. K. (1996). Service value determination: An integrative perspective. Journal of Hospitality & Leisure Marketing, 3(4), 5-25.

Jobst, J., & Boerner, S. (2015). The impact of primary service and servicescape on customer satisfaction in a leisure service setting: an empirical investigation among theatregoers. International Journal of Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Marketing, 20(3), 238-255.

Kim, K., & Tucker, E. D. (2016, April). Assessing and segmenting entertainment quality variables and satisfaction of live event attendees: A cluster analysis examination. In Journal of Convention & Event Tourism (Vol. 17, No. 2, pp. 112-128). Routledge.

Kim, T., Ko, Y., & Park, C. (2013). The influence of event quality on revisit intention: gender difference and segmentation strategy. Managing Service Quality, 23(3), 205-224.

Knobloch-Westerwick, S. (2006). Mood management: Theory, evidence, and advancements. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

Lacher, K. T., & Mizerski, R. (1994). An exploratory study of the responses and relationships involved in the evaluation of, and in the intention to purchase new rock music. Journal of Consumer Research, 21(2), 366–380.

Lim, C. C., & Patterson, L. (2008). Sport tourism on the islands: The impact of an international mega golf event. Journal of Sport & Tourism, 13(2), 115–133

Lin, I. Y. (2004). Evaluating a servicescape: the effect of cognition and emotion. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 23(2), 163-178.

Mason, M. C., & Paggiaro, A. (2012). Investigating the role of festivalscape in culinary tourism: The case of food and wine events. Tourism Management, 33(6), 1329-1336.

McHone, W. W., & Rungeling, B. (2000). Practical issues in measuring the impact of a cultural tourist event in a major tourist estimation. Journal of Travel Research, 38(3), 299–302.

Mills, J. (1993). The appeal of tragedy: An attitude interpretation. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 14(3), 255-271.

Milohnic, I., Lesic, K. T., & Slamar, T. (2016). Understanding the motivation for event participating-a prerequisite for sustainable event planning. In Faculty of Tourism and Hospitality Management in Opatija. Biennial International Congress. Tourism & Hospitality Industry (p. 204). University of Rijeka, Faculty of Tourism & Hospitality Management.

Nijs, D. (2003). Imagineering: engineering for imagination in the emotion economy. Creating a Fascinating World, 15-32.

Oliver, R. L. (1980). A cognitive model of the antecedents and consequences of satisfaction decisions. Journal of Marketing Research, 17(4), 460-469.

Oliver, M. B. (1993). Exploring the paradox of the enjoyment of sad films. Human Communication Research, 19(3), 315-342.

Oliver, Mary & Bartsch, Anne. (2010). Appreciation as audience response: exploring entertainment gratifications beyond hedonism. Human Communication Research. 36(1). 53 – 81.

Pearce PL. (2008). Tourism and entertainment: boundaries and connections. Tourism Recreation Research 33(2): 125–130.

Petrick, J. F., Morais, D. D., & Norman, W. C. (2001). An Examination of the Determinants of Entertainment Vacationers’ Intentions to Revisit. Journal of Travel Research, 40(1), 41- 48.

Pine, B. J., & Gilmore, J. H. (1998). The Experience Economy. Boston, MA: Harvard Business.

Pine, B. J., & Gilmore, J. H. (1999). The Experience Economy: Work is Theatre & Every Business a Stage. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press

Richards, G. (2011). Creativity and tourism: The state of the art. Annals of Tourism Research, 38(4), 1225–1253.

Ryan, R. M., Huta, V., & Deci, E. L. (2013). Living well: A self-determination theory perspective on eudaimonia. In The exploration of happiness (pp. 117-139). Springer Netherlands.

Sherry, J. L. (2004). Flow and media enjoyment. Communication theory, 14(4), 328-347.

Song, H., & Cheung, C. (2010). Attributes affecting the level of tourist satisfaction with and loyalty towards theatrical performance in China: Evidence from a qualitative study. International Journal of Tourism Research, 12(6), 665-679.

Scott, N., Laws, E., & Boksberger, P. (2009). The marketing of hospitality and leisure experiences. Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management, 18(2-3), 99-110.

Tamborini, R., Bowman, N. D., Eden, A., Grizzard, M., & Organ, A. (2010). Defining media enjoyment as the satisfaction of intrinsic needs. Journal of communication, 60(4), 758- 777.

Tan, S. K., Kung, S. F., & Luh, D. B. (2013). A model of ‘creative experience’ in creative tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 41, 153-174.

Thrane, C. (2002). Jazz festival visitors and their expenditures: Linking spending patterns to musical interest. Journal of Travel Research, 40(3), 281–286.

Urry, J. (1990). The Tourist Gaze: Leisure and Travel in Contemporary Societies. London. Sage.

Vorderer, P., Steen, F., & Chan, E. (2006). Motivation. In J. Bryant & P. Vorderer (Eds.), Psychology of Entertainment (pp. 3–17). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Wakefield, K. L., & Blodgett, J. G. (1996). The effect of the servicescape on customers’ behavioral intentions in leisure service settings. Journal of Services Marketing, 10(6), 45- 61.

Westbrook RA, Oliver RL. (1991). The dimensionality of consumption emotion patterns and consumer satisfaction. Journal of Consumer Research 18(1): 84–91.

Witvliet, C. V., & Vrana, S. R. (2007). Play it again Sam: Repeated exposure to emotionally evocative music polarises liking and smiling responses, and influences other affective reports, facial EMG, and heart rate. Cognition & Emotion, 21(1), 3-25.

Woodruff, R. B. (1997). “Customer Value: The Next Source for Competitive Advantage.” Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 25(2): 139-53.

Yuksel A., Yuksel F. (2002). Measurement of tourist satisfaction with restaurant services: a segment based approach. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 9(1): 52–68.

Zajonc, R. B. (1968). Attitudinal effects of mere exposure. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 9 (2p2), 1.

Zeithaml, V. A. (1988). Consumer perceptions of price, quality, and value: a means-end model and synthesis of evidence. The Journal of Marketing, 52(7): 2-22.

Zillmann, Dolf. (2000). “The Coming of Media Entertainment.” Media Entertainment: The Psychology of its Appeal. Eds. Peter Vorderer and Dolf Zillmann. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum, 1-20.

Cite This Work

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing stye below:

Related Services

View allRelated Content

All TagsContent relating to: "Theatre"

Theatre studies typically explore drama and theatre in a cultural and social context and cover a range of theatre and drama practices and companies.

Related Articles

DMCA / Removal Request

If you are the original writer of this dissertation and no longer wish to have your work published on the UKDiss.com website then please: