Traditional Korean Music in Contemporary Context: A Performance Guide to Gideon Gee Bum Kim’s Kangkangsullae.

Info: 11730 words (47 pages) Dissertation

Published: 10th Dec 2019

Tagged: Music

Traditional Korean Music in Contemporary Context:

A Performance Guide to Gideon Gee Bum Kim’s Kangkangsullae.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Chapter Page

- INTRODUCTION…………………………………….…………1

- BIOGRAPHY OF GIDEON GEE BUM KIM……………………6

- BACKGROUND INFORMATION OF TRADITIONAL KOREAN MUSIC………………………………………………………………10

- SELECTED CHAMBER MUSIC WORK OF GIDEON GEE BUM KIM: KANGKANGSULLAE………………………………16

4.1 Historical, Cultural and Compositional Background of the Kangkangsullae………………………………………………….16

4.2 Musical Aspects of Kangkangsullae………………………………..18

- CONCLUSION………………………………………………….44

BIBLIOGRAPHY……………………………………………………46

CHAPTER 1

INTRODUCTION

1.1 Purpose of Study

As interest in traditional Korean music grows, the works of certain Korean composers are becoming increasingly popular among international performers and audiences. For example, Isang Yun, one of the most famous Korean composer from South Korea, combined elements of traditional Korean music and the Eastern philosophy of Taoism using the twelve-tone techniques.[1] Another famous composer, Youngjo Lee, integrated a variety of nineteenth and twentieth century compositional techniques such as tone clusters, unresolved diminished chords, cyclic form, and octatonic scales in his works.

Gideon Gee Bum Kim (1964) is an internationally-acclaimed contemporary Korean-Canadian composer. Kim has utilized traditional Korean musical elements with Western compositional techniques in some of his works. An understanding of Korean compositional elements in his music is essential for the study of his works.

The purpose of this study is to develop a performance guide for Gideon Gee Bum Kim’s Kangkangsullae for string trio. I will give a detailed historical and cultural background for this work and will demonstrate how Kim integrated Western compositional techniques with traditional Korean music. My emphasis will be on defining specific characteristics of traditional Korean music which will provide several points toward understanding Kim’s compositional style.

Furthermore, there is no literature to date that discusses or analyzes Gideon Gee Bum Kim’s unique compositional style. Kim created his own style by incorporating traditional Korean musical elements such as the scale, rhythmic diversity, metric variability, syncopation, variation, ornamentation, and the progression of melody into a body of music that is otherwise contemporary and Western. I hope this study will encourage string players to perform Gideon Gee Bum Kim’s valuable works and will inform listeners of the existence of traditional Korean musical elements in his works.

1.2 Method

The study will include composer interviews, background information of traditional Korean music, and analysis. Because there is not sufficient existing research on Kim’s works, this study will contain interviews with the composer.

Interview Questions about the Music:

-Did you use the original Kangkangsullae (traditional Korean women’s dance genre) as inspiration for your Kangkangsullae?

-Korean Minyo (Korean folk songs)have several particular characteristics such as melody, the use of Korean instruments, dance components, and other elements of Korean culture. Did you apply any of these characteristics in Kangkangsullae?

-Is there a specific reason you titled the piece in Korean?

-Why did you compose this work for string trio?

-In m.1 and mm.51-56, I feel like I have heard the melody before. Did you take the motive from the original Kangkangsullae?

-All three instruments are alternating the same melodies several times. Did you want to show Korean rhythmic patterns or Western Heterophony?

-To what degree do you utilize traditional Korean music?

To understand kangkangsullae as a musical work, performers must be aware of the inner meaning of the words of the Korean title and the historical and cultural background of traditional Korean music. A correct understanding of the historical and cultural backgrounds, as well as traditional musical elements such as melody, rhythm, meter, syncopation, and ornaments, are essential to perform an accurate and effective performance of Gideon Gee Bum Kim’s music.

For analysis, I will discuss how Kim uses the above-mentioned Korean traditional musical elements in relation to Western music in Kangkangsullae. I also will demonstrate how Kim composes and imitates traditional Korean music and from what sources he draws his core materials.

1.3 Significance and State of Research

Korea’s long history of its unique musical tradition has been recreated by Gideon Gee Bum Kim and other composers during the twentieth and twenty-first centuries using contemporary compositional techniques.

Gideon Gee Bum Kim (b.1964) is an internationally-acclaimed contemporary Korean-Canadian composer. Kim has utilized unique tone colors in Korean music while combining Western elements. Kim’s music exemplified the development of melody, irregular rhythmic changes, and harmonic progression, recalling traditional Korean music, while simultaneously adding Western materials and techniques. Kim’s main goal of composition is not to imitate or mimic traditional Korean music, but to create new sounds by using both Eastern and Western musical styles.

The recontextualization of traditional Korean music has been regarded as one of the effective ways to integrate Western compositional techniques. Korean composers such as Isang Yun and Heejo Kim have enthusiastically embraced many aspects of Western musical traditions and have used them to compose works based on traditional Korean music.

Some composers have evoked Korean music in their contemporary compositions through the use of emulating and utilizing the sound of Eastern instruments. Jihyun Son discussed how Younghi Pagh-Paan emulated the sound of traditional Korean percussion instruments, such as the Jango, on the violin through techniques such as collegno (playing with the wood of the bow). Son also mentioned that Pagh-Paan has written orchestral pieces that include traditional instrument groups, the Piri (a type of cylindrical oboe)and Daegeum (a Korean wind instrument), along with a larger, more Western orchestra.[2]

Composers of choral music, such as Heejo Kim, have incorporated elements of traditional Korean music into choral textures. Chunghan Yi discussed how Heejo Kim used a traditional Korean rhythmic pattern, the Jangdan, in his piece Bat-No-Rae. Gideon Gee Bum Kim also used this rhythm, but in the context of music written for solo violin and string trio.[3]

The most famous Korean composer, Isang Yun, used twelve-tone techniques in his music. Koeun Lee describes how Yun would utilize one or two of the possible forty-eight row forms of a given row matrix in FÜNF STÜCKE FÜR KLAVIER.[4] Gideon Gee Bum Kim also used methods of pitch organization common to twentieth-century music, such as pentatonic collections.

Korean Folk Songs are simple songs that contain the inherent sentiments of the Korean people, which are created and have evolved in the lives of the Korean people for many years.[5]

Kangkagnsullae trio is based on Korean historical, cultural and musical influences. They are designed both for Koreans and international audiences.

There are no academic publications about Gideon Gee Bum Kim’s chamber works. I will study Kim’s chamber work, concentrating on his compositional style, which integrates traditional Korean and Western music. Also, musicians who play this piece may lack information needed to perform it according to Kim’s compositional design. With this study, performers can understand Kim’s musical expression. Furthermore, although Kim’s music is played in both Korea and Canada, it is not well-known in the United States. Therefore, this study will provide the historical and cultural background and the analytical foundation needed to understand the use of traditional Korean music in a contemporary context as exemplified in Gideon Gee Bum Kim’s Kangkangsullae trio. Additionally, this study will introduce these works to a larger body of performers and audiences.

CHAPTER 2

BIOGRAPHY OF GIDEON GEE BUM KIM

In chapter 2, I will introduce the biography of the composer, Gideon Gee Bum Kim in order of the different places he resided. He lived in three different countries: South Korea, the United States, and Canada.

Gideon Gee Bum Kim (b.1964) is an internationally-acclaimed contemporary Korean-Canadian composer. Kim utilized unique tone colors of Korean music in combination of Western elements. Kim studied in Korea and the United States where he learned both traditional Korean musical elements and Western harmony, melody, form, texture, and many other contemporary compositional techniques. Kim’s music exemplified the development of melody, ornamentation, irregular rhythmic changes, and harmonic progression, recalling traditional Korean music, while simultaneously adding Western materials and techniques. His music combines the musical heritage of Korean and Western compositional techniques, especially in the field of heterophonic textures.

Kim has become an established musician as a composer, conductor, music educator, and performer in Asia, Europe, and Canada. He teaches composition at the Reformed Presbyterian Seminary of the East, in Toronto, Canada; and Kim is a composer with the Canadian Music Centre. He has composed a large output of orchestral, chamber, and vocal works. He studied composition both in Korea and in the United States at the University of Pennsylvania.

Kim was born in Seoul, South Korea in 1964. Kim began piano lessons at the age of five and performed a Mozart piano concerto at age eleven. However, he quit playing the piano when he was fifteen. His parents were deeply touched after listening to a performance of Messiaen and recommended that Kim study composition as his father had done.

Kim received his B.A. in Music Composition at Seoul National University. One of his mentors, Youngja Lee, was an Honorary Professor at Seoul National University and the Honorary Chairman of the Association of Korean Women Composers.

Gideon Kim won the very famous Dong-A music competition when he was twenty-one in South Korea. Kim’s orchestral work, “Strange Experience” won the competition and was played by the Seoul Philharmonic Orchestra.

Kim was a music composition professor at Kyungwon University in South Korea for twelve years from 1992 to 2004. His music was published by Ye-Dang Press and can be heard on Sony Classical, Synnara Music, and Sung Eum Limited labels.

Kim’s Song of the Heavens and Firmament for piano triowas awarded the grand prize at the 1993 Korean Broadcasting System (KBS) Composition Competition and the 1994 Ye Eum Composition Award from the Ye Eum Culturale Foundation. His Symphony No.1, The Strange Seasons for orchestra, won the 1995 Ahn Eak Tae Composition Award from the Ahn Eak Tae Foundation of The Korea Times. In 1998, Kim was honored by South Korea’s Ministry of Culture and Tourism as the first composer to receive Today’s Young Artist Award.

Kim spent over five years in the United States between 1987 and 1991. Kim received his M.A. and Ph.D. in Music Composition from the University of Pennsylvania under George Crumb. George Crumb was one of his important mentors. Crumb described Kim as “a composer who shows great originality in use of rhythm and harmony, and possesses a fine melodic gift. Gideon Gee Bum Kim’s music shows a connection of the rich musical heritage of Korea and new compositional techniques, especially in the field of heterophonic texture and all of this with live and emotional imagination.”[6]

Kim was a Distinguished Composer-in Residence at Colorado College, which honored him with an all-Kim concert, performing various chamber and solo works that he composed. He was also a Visiting Scholar at the University of Pennsylvania as well as a guest composer at the University of Pittsburgh, University of Oregon, and Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

In 2000, Kim was awarded the International Commission Prize from Music at the Anthology (MATA) in New York.[7]

Kim has been an Associate Composer at the Canadian Music Centrewhich has highlighted his music since he moved to Toronto, Canada in 2004. He is the professor at the Reformed Presbyterian Seminary of the East. He is also a member of the Canadian League of Composers and the American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers.

In 2011, Kim founded the Toronto Messiaen Ensemble, a Canadian chamber ensemble dedicated to the performance of classical and contemporary music. The goal of the ensemble is to express a positive and hopeful message through music and Kim is serving as Artistic Director of the ensemble. In 2015, he also became Music Director of the Yemel Philharmonic Society in Toronto.

Kim’s works have been performed regularly in concert halls, festivals and in music worship services in Europe, North America and Asia.

His works have been commissioned and performed worldwide by leading ensembles and orchestras such as the Jerusalem Kaprizma Ensemble, Gaudeamus Ensemble of Amsterdam, North/South Chamber Orchestra of New York, Continuum of New York, New York Treble Singers, Gamelan Son of Lion of New York, Curtis Institute Orchestra of Philadelphia, Quattro Mani of Colorado, Toronto Esprit Orchestra, Montreal QAT Ensemble, Orchestra London Canada, Taiwan National Symphony Orchestra, Seoul Philharmonic Orchestra, Korean Symphony Orchestra, New Seoul Philharmonic Orchestra, Prime Philharmonic Orchestra, Seoul Baroque Ensemble, Trio Haan and Color String Quartet, Music AT The Anthology, Colorado College, Korean Broadcasting System, National Gugak Center, Music Association of Korea, Korean-Canadian Symphony Orchestra, Lee Myung Hee Gayaguem Quartet, and the Israeli Embassy in Seoul.

Kim has written many instrumental pieces, concertos, songs, and operas that utilize Korean traditional musical elements. His compositions reflect his strong understanding of Korean rhythms and harmonies as well as Western music characteristics.

Kim’s main goal of composition is not to imitate or mimic traditional Korean music, but to create new sounds by using both Eastern and Western musical styles.

CHAPTER 3

BACKGROUND INFORMATION OF TRADITIONAL KOREAN MUSIC

In this chapter I will examine background information regarding traditional Korean music. I will provide information about how traditional Korean musical elements relate to Kim’s music. I will give the essential information that performers need to know to understand Kangkangsullae music.

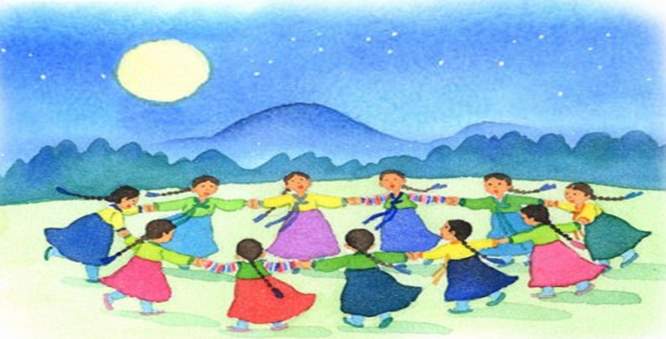

Example 1. Image of Kangkangsullae dance

Traditional Korean music has several unique characteristics.

First, Korean folk songs are simple songs that contain the inherent sentiments of the Korean people. These sentiments are created and have evolved in the lives of the Korean people over time.[8] An example of this is the Korean folk song entitled, Minyo. Itis the Korean functional and unique public genre of folk song that maintains its own ethnical, historical, cultural, and regional characteristics. It has existed for so long that it is unknown what its origins are.

Minyo requires no particular training. It gained popularity because anyone could sing these folk songs. The themes express optimism, the love of the simple life, and the strong feeling of resignation and regret in Korean culture. [9] Minyo is comprised of songs with no recognized composers. It has a shrouded and timeless history, and few prescribed texts. Minyo varies from village to village and tends to use simple strophic melodies.[10]

Second, ornamentation and embellishments are two of the characteristics of traditional Korean music. I want to introduce two unique performance techniques for expression of ornamentation, the first being Sigimsae. Sigimsaeconsists of notes that ornament the main pitch from in front of or behind a musical note.[11] The other technique is Nonghyun. Itis also one of the ornamentation techniques for strings in traditional Korean music, which can embellish the melodic line. Nonghyun is represented by glissandi and grace notes. Itconsists of two different approaches, Chusungand Tosung. Chusung is glissando from a lower note to higher note. Tosung is a glissando from a higher note to a lower note. Chusung is shown in traditional Korean music called Jindo Arirang. This is marked with a circle in Example 2. Tosung is shown in Jindo Arirang as well, which is marked with square in Example 2.

Example 2. Jindo Arirang

Example 3. Translation of Jindo Arirang

아리아리랑 서리서리랑 아라리가났네 (Ari arirang, Sri srirang, Arari has appeared)

아리랑 응응응 아라리가났네 (Arirang, Ung Ung Ung, Arari has appeared)

아리아리랑 서리서리랑 아라리가났네 (Ari arirang, Sri srirang, Arari has appeared)

아리랑 응응응 아라리가났네 (Arirang, Ung Ung Ung, Arari has appeared)

오다가 가다가 만나는 님은 (A lover who I meet by chance)

팔목이 끊어져도 나는 못놓겠네. (I cannot let go the lover I met even if my wrist would be broken)

Chusung (the circle marking) can be seen above as the glissando from A to C or from C to E. Tosung (the square marking) is shown as the glissando moving from A to E or E to C.

Gideon Gee Bum Kim used these ornamentations using the glissando marking for string players in Kangkangsullae trio. I will show these examples in chapter 4.

Third, traditional Korean music neither uses common cadences nor major or minor scales.

Samumgae consists of three pitches. Oeumgae is a musical scale with five pitches. Oeumgaemeans “consisting of five pitches.” There are three different Oeumgae. The first Oeumgae contains C, D, E, A, G, which is called Yoojo. The second Oeumgae consists of C, E-flat, F, G, and B-flat. The third, Oeumgaeuses C, D, F, G, and A. This is called Pyeongjo. The Oeumgae scale is similar to a Western pentatonic scale.Usually, many pentatonic and monadic melodies are present in the traditional Korean music such as Mynyo and Pansori (a traditional Korean musical storytelling).

Fourth, Koreans call rhythm and tempo, Jangdan. However, the concept of Jangdan is very different from that of Western rhythm. Koreans developed Jangdan based on human breathing. Some rhythms were intended to follow deep breaths, and other rhythms were designed to follow quick breaths, producing the long and short cycles of Jangdan.[12]

There are several common traditional Korean rhythmic Jangdan: Toduri, Semachi and Gutguri.[13] Each Jangdan has a particular tempo and its own rhythmic groupings and is determined by accent and meter. Ever since ancient times, Jangdan is recognized with three-beat grouping structures of rhythms and advanced techniques using irregular meters.[14] Jangdan patterns utilize predominantly triple or compound meters to a much greater extent than is common in Western music.[15]

Rhythmic groupings are an important characteristic of traditional Korean music. 12/8 is a time signature known to all Koreans.[16] Some common historical metrical structures include 12/8 (3+3+3+3), (3+3+2+2+2), (2+2+2+3+3), (3+2+2+2+3), 9/8(3+3+3), 8/8(2+3+3), 7/8(3+2+2), 6/8(3+3), 5/8(3+2), and 3/8(3). Almost every measure is divided into smaller groups of two or three beats. Korean music is typically composed in flexible tempos and uneven beats that imitate the irregular breathing pattern of humans.[17]

Fifth, the history of Korean contemporary music in the twentieth century can be divided into three generations of composers. The first generation are those composing in the period under the Japanese reign (1910 – 1945) and military administration (1945 – 1948). The second covers the period of 1950 – 1970. And the third is after 1980. Composers of the first generation wrote songs mostly using European musical materials with simple tertian tonal systems, while those of the second and third generations developed a more advanced harmonic style and ventured into larger form chamber music and orchestral works.[18]

CHAPTER 4

GIDEON GEE BUM KIM’S CHAMBER WORK FOR STRING TRIO:

KANGKANGSULLAE

In chapter 4, I will study Kangkangsullaetrio, composed by Gideon Gee Bum Kim. I will provide historical and cultural backgrounds along with music analyses containing traditional Korean musical characteristics as a performance guide. I will present the composer’s general musical techniques associated with traditional Korean elements absorbing Western compositional techniques to help the performer understand the composer’s intentions.

In order to understand Kim’s musical works, performers must be aware of the inner meaning of the Korean words in the title and the historical and cultural background of the form of Kangkangsullae. I will provide Korean cultural, historical and compositional aspects related to the music as a performance guide. An understanding of both Eastern and Western elements can help musicians play Kim’s work.

4.1 Historical, Cultural and Compositional Background of the Kangkangsullae.

The term Kangkangsulleis an ancient native Korean word with no specific modern meaning. Korean historians guess the dance to be thousands of years old. The ancient tradition was added to the list of UNESCO’s (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization) Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity in 2009.

The Kangkangsullae dance is the most representative cultural activity of South Korea. The dance is comprised of a large circle of women holding hands and singing. Original song lyrics exist; however, the lyrics are sometimes improvised with each dance. The dance usually reflects woman’s emotions such as sorrow, happiness, anger, and so on. The starting direction of the round dance is always to the right. The genre of songs accompanying this dance is referred to as kangkangsullae and is a women’s genre.

Although the dance movements are relatively simple, the speed of the dance steps in the choreography corresponds with the music, which may be fast and vigorous at times, or slow in other instances. The dance is unique, innovative, and striking as a part of Korean heritage.

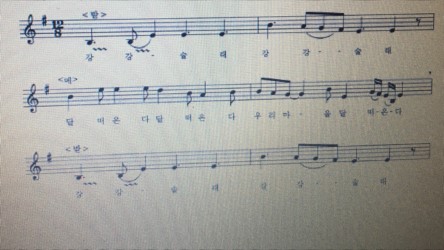

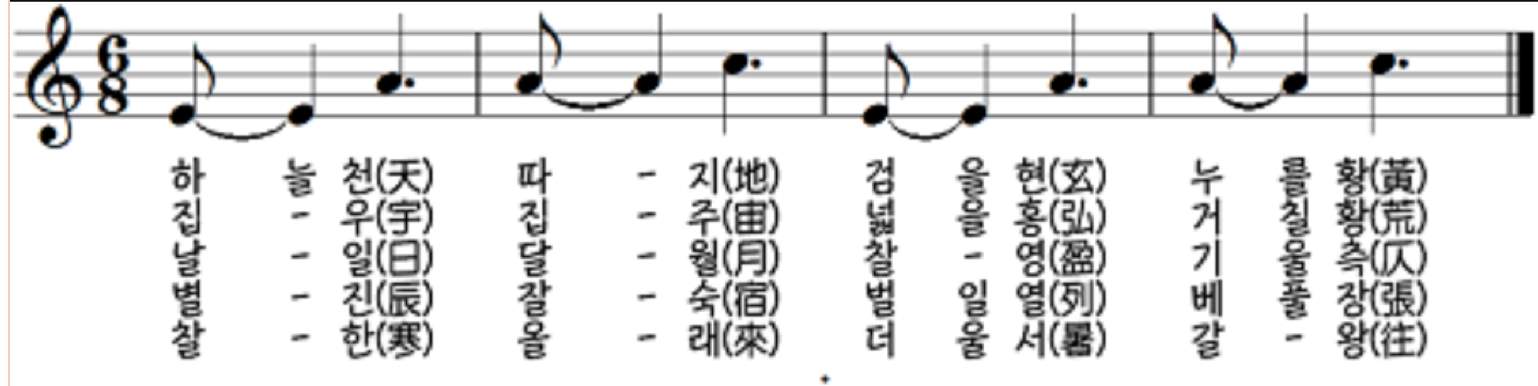

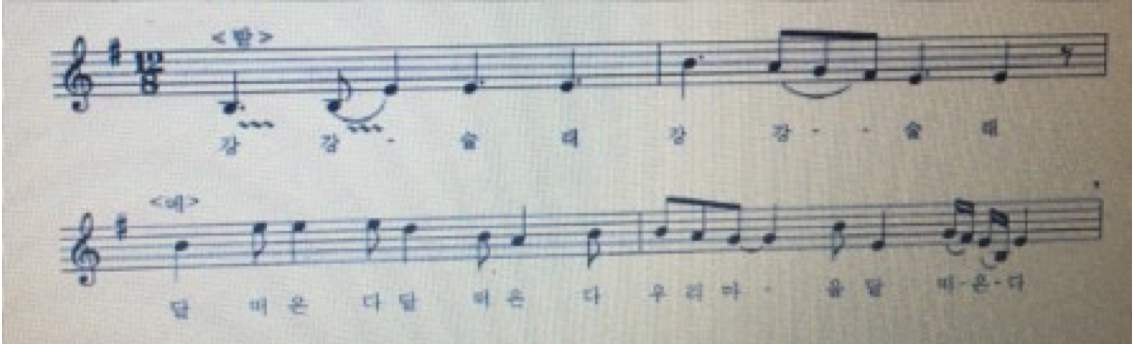

Example 4. Original Kangkangsullae music

For compositional background regarding the Kangkangsullae, Kim interpreted the original Kangkangsullae in a contemporary sense for string trio. Kim’s Kangkangsullae for string trio was written for the twentieth anniversary of KBS FM Radio and Professor, Mark Kopytman’s seventiethanniversary.[19] The piece was selected for the International Rostrum of Composers in Unesco, Paris in 2002.

4.2 Musical Aspects of Kangkangsullae

The original Kangkangsullae is very simple musically, but Kim created a more energetic, joyous, active, and complicated music in his unique Kangkangsullae. Kim stated that he was trying to express the substance of the original Kangkangsullae.

The structure of Kangkangsullae for string trio is found in development and change, which takes place in sections that hint of the original Kangkangsullae, some of which clearly make use of it, and others that freely use the theme in variations. All of these things combine to evoke a spirit of celebration.

Kangkangsullae trio was composed in 1999. It is one movement, one key signature, and thirteen minutes long. The music looks easy to play at first, but each player must play without breaks. During the performance, there are only several one-measure grand pauses or two-measure long breaks. Therefore, it requires both good concentration and excellent technique.

For right hand techniques, performers require smooth string crossings, three note chords, syncopation, tremolo, pizzicato, Bartok pizzicato, and expression of piano and sforzando to enrich the color of the music. As for left hand techniques, performers require a wide and broad vibrato while playing in a slow tempo because Korean music vibrato is more broad and wider than Western. Glissando, chords, ornamentation, and exact rhythm of Korean Jangdan are also required.

Kangkangsullae follows a ternary form. The music is clearly divided into nine sections and composed for violin, viola and cello. Part A consists of four sections. Part B consists two sections. A’ consists of three sections. There is a one measure grand pause before starting the new section at the end of section 1, 2, 4, and 5. The division of these nine sections are shown below in Example 5.

Example 5. Structure of section division in Kangkangsullae

Section I: mm. 1-31

Section I: mm. 1-31

Section II: mm. 32-50

A Section III: mm. 51-88

Section IV: mm. 89-145

Section V: mm. 146-158

Section V: mm. 146-158

B Section VI: mm. 159-181

Section VII: mm. 182-199

Section VII: mm. 182-199

A’ Section VIII: mm. 200-208

Section IX: mm. 209-235

I will examine Korean traditional elements that Kim applied in Kangkangsullae.

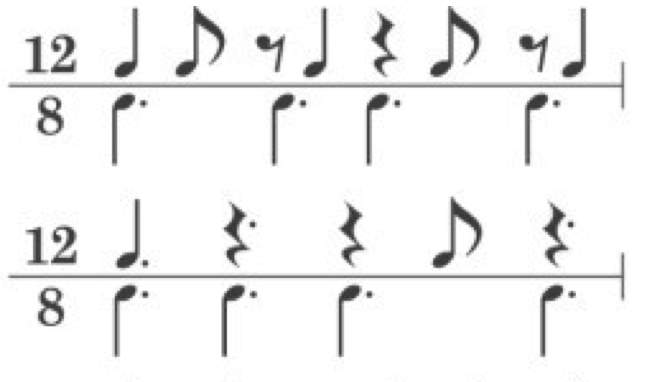

First, Jangdan is recognized by two or three beat groupings using traditional Korean rhythms. The music emphasizes rhythmic elements. As far as traditional Korean compositional rhythmic elements, compound meters are an important characteristic in this genre. Korean folk music is noted for symmetrical metric structures. 12/8 time, is a musical rhythm known to all Koreans.[20] As stated in chapter 3, some common historical metrical structures include 12/8 (3+3+3+3), (3+3+2+2+2), (2+2+2+3+3), (3+2+2+2+3), 9/8(3+3+3), 8/8(2+3+3), 7/8(3+2+2), 6/8(3+3), 5/8(3+2), and 3/8(3). Almost every measure is divided into smaller units of two or three beats. Korean music is typically composed in flexible tempos and uneven beats that imitate the irregular breathing pattern of humans.[21]

Kim utilized metrical variety, such as 3/8, 4/8, 5/8, 6/8, 8/8, and 12/8 consecutively, and they appear in his Kangkangsullae frequently to represent traditional Korean metrical variety. In traditional Korean music, Western tempo markings such as, 2/4, and 4/4 are rarely used. To understand Kim’s music, Jangdan and compound meter are necessary for players. Kim wanted to express the joy of the women’s Kangkangsullae dance through meter changes. For performers who have had no experience in playing Jangdan, this technique can be confusing at first, but it becomes easier with practice.

Some unique traditional Korean rhythmic patterns of Jangdan, such as

Semachi, Chungchungmori, Jajinmori, Utmori, and Danmori are utilized in Kangkangsullae trio. These five different Jangdans each have varying characteristics.

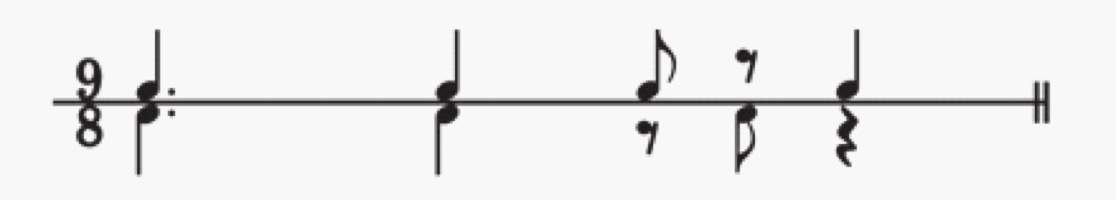

Semachi Jangdan is a 9/8 meter marking. Ninety percent of Jangdan that have a 9/8 meter are most likely Semachi Jangdan. It is divided by three (3+3+3) and has a fast tempo. The Semachi Jangdan is frequently used in Mynyo. A famous Korean folk song, Arirang also uses Semachi Jangdan.

Example 6. Original Semachi Jangdan

All of Jangdan can vary rhythmically, but stay within the same meter marking or rhythmic groupings of three. In Kangkangsullaetrio, Kim did not apply the exact same Semachi Jangdan, but he used a similar rhythm based on it.

Example 7. Rhythmic variety based on Semachi Jangdan

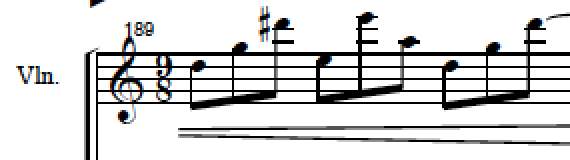

In measure 189, the three groupings consist of all nine notes in the violin part.

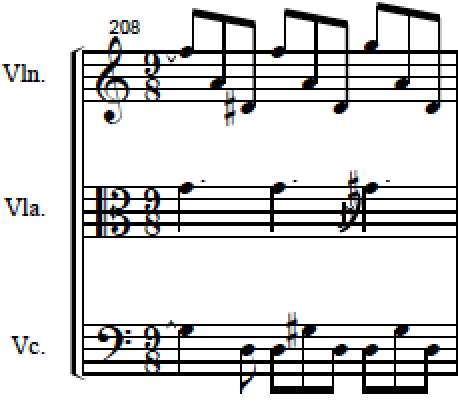

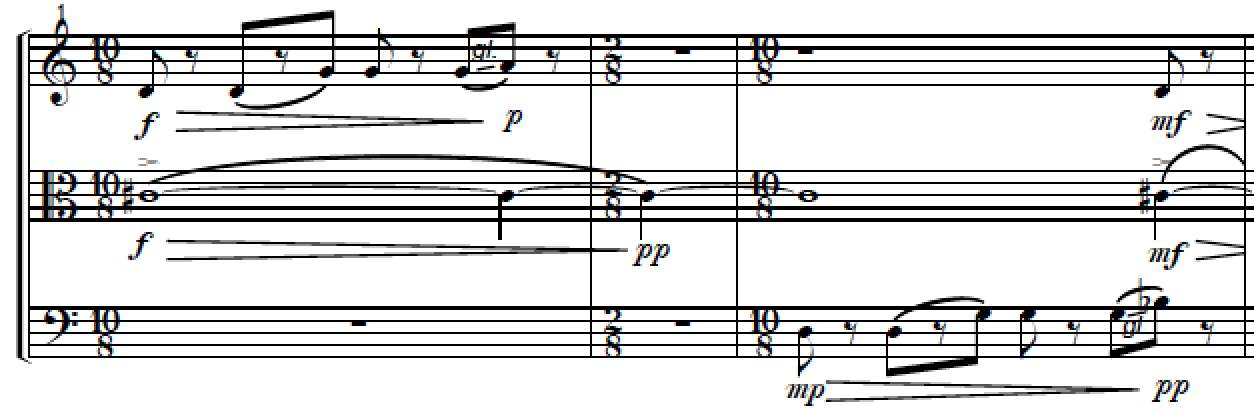

Example 8. Kangkangsullae, m. 208

In measure 208, Kim applies all three different forms of rhythms based on Semachi Jangdan.

Example 9. Kangkangsullae,m. 222

In measure 222 and 226, Kim applies all three different forms of rhythms based on Semachi Jangdan.

Example 10. Kangkangsullae, m.230

A new rhythm is also applied in measure 230.

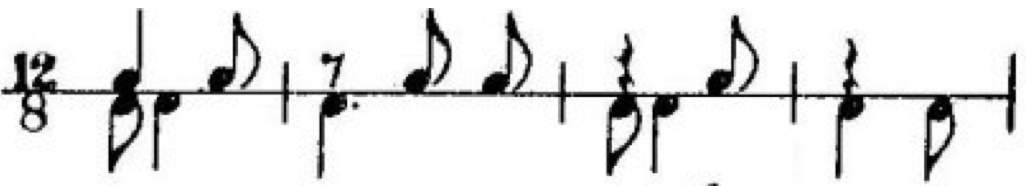

Chungchungmori Jangdan is a 12/8 meter marking. Original Kangkangsullae used this Jangdan. Chungchungmori Jangdan is faster than Chungmori Jangdan, which is moderato in the Western tempo marking and slower than Jajinmori Jangdan.

Example 11. Chungchungmori Jangdanin Kangkangsullae, m.211

Kim applies this same rhythmic pattern based on Chungchungmori Jangdan in the viola line in measure 211. Kim varies the rhythmic pattern based on Chungchungmori Jagdan in the viola in measure 215.

Example 12. Kangkangsullae, m.215

Example 12. Kangkangsullae, m.215

Jajinmori Jangdan is a 12/8 meter marking. It can be played in three ways: slow-Jajinmori, moderate-Jajinmori, and Jajinjajinmori (fast-Jajinmori). Jajinmori means, “very hurried” in Korean. This Jangdan gives the performer a feeling of excitement and joy.

Example 13. Jajinmori Jangdan

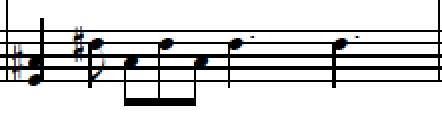

Kim applies different kinds of rhythms based on the Jajinmori Jangdan violin part in measure 63, the cello part in measure 65, and the viola part in measure 66.

Example 14. Kangkangsullae, mm.63-66

The same rhythm found in the violin part in measure 63 can be found in measures 211 and 215 (violin), measures 196 and 206 (viola), and measure 53, 59, 202, 206, and 212 (cello).

Utmori Jangdan is a 10/8 meter marking. It is composed of a combination of two beats and three beats. For example, eighth notes can be divided into four groups, such as (3+2+3+2), (3+2+2+3), (2+3+2+3). It can be divided into four groupings with three beats and two beats in three different combinations. As a result of this, it can be regarded as unequal four groupings with the Western tempo criteria. In fact, Utmori means “uneven rhythm” in Korean.

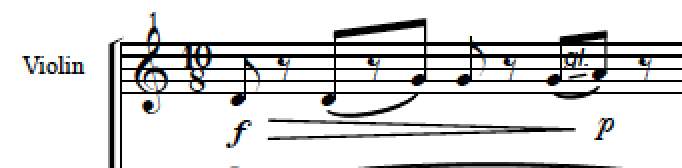

Example 15. Kangkangsullae based on Utmori Jangdan, mm.1-3

The violin uses a 2+3+2+3 rhythmic grouping in measure 1. The cello uses the same rhythmic grouping in measure 3, which is marked by a square.

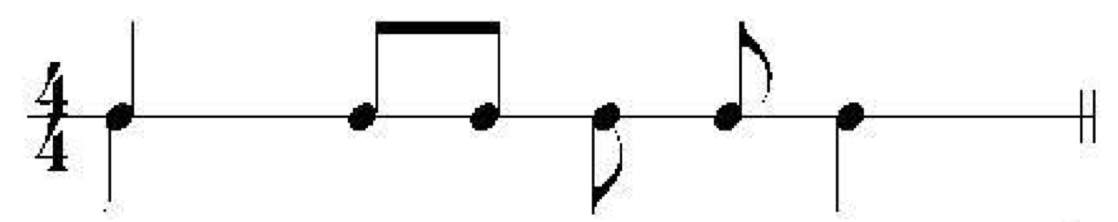

Danmori Jangdan is a 4/4 meter marking. Hwimori Jangdan is another name for Danmori Jangdan. It is the fastest of all the Jangdans. It provides a light, exciting, and cheerful atmosphere.

Example 16. Danmori Jangdan

m.26

m.26

Kim applies the same rhythm from the Danmori Jangdan in the viola in measure 26 of Kangkangsullae.

All Jangdans have different tempos. The order of the Jangdan tempos are shown in example below.

Example 17. Jangdan tempo order from fastest to slowest

| Tempo | Type of Jangdan |

| Fastest

Slowest |

Danmori |

| Jajinmori | |

| Semachi | |

| Chungchungmori | |

| Gutguri | |

| chungmori |

Jungmori Jangdan is comparable to moderato in Western tempo. Danmori Jangdan is comparable to presto in Western tempo.

All Jangdans can vary rhythmically in different ways but use the same meter marking. Kim did not apply the exact same rhythm, but he used similar rhythms based on the Jangdan.

It is important to understand each characteristic of Jangdan for players to understand and perform Kim’s Kangkangsullae.

As for rhythmic patterns, Kim also used syncopation. Syncopation is a common technique in Korean dance music. Kim used syncopation to express the dynamic figure of the woman’s dance, Kangkangsullae.[22]

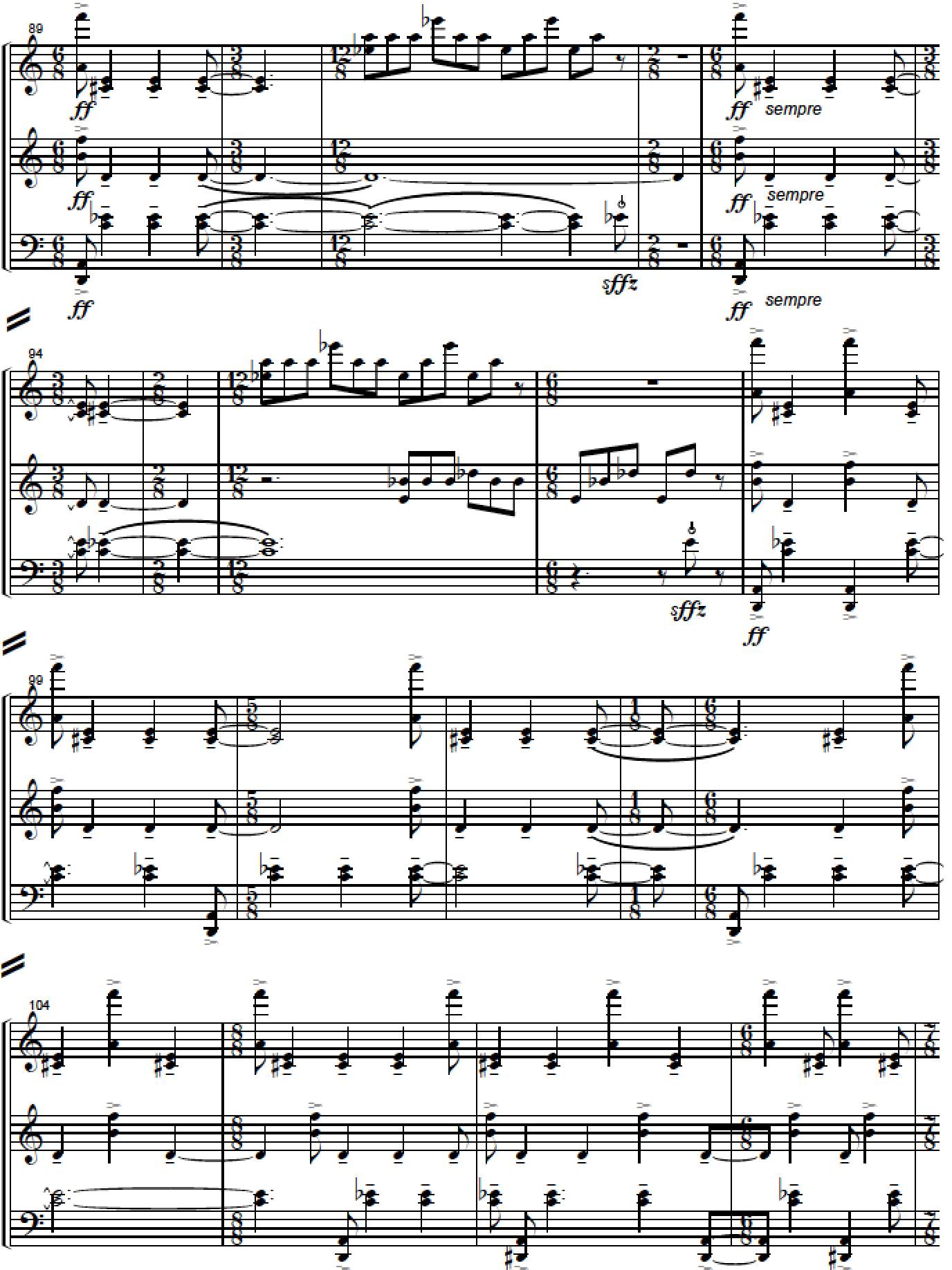

Example 18. Syncopated rhythmic patterns in Kangkanasullae mm.89-107

For suspension, syncopation is shown in mm.89, 93, 99-102, 109, and 112. The last beat in the measure carried over to next beat. This is marked with a circle. Also, there is off-beat syncopation in mm.98 and 105. The stress can be shown in the off beats. This is marked with a square. Performers have to put biting accents on all roles with accent markings.

Metrical variety is also one of the characteristics of Korean music. Kim wanted to express natural accelerando for players utilizing different meter markings in mm. 120-123 which create the illusion of an accelerando.[23]

The metrical variety is shown in brackets in the example below.

Example 19. Metrical variety of Gideon Gee Bum Kim’s Kangkangsullaetrio, mm. 112-123

Meter changes and accents appear in almost every measure. Performers must maintain strength on the bow to express each accent for articulation purposes.

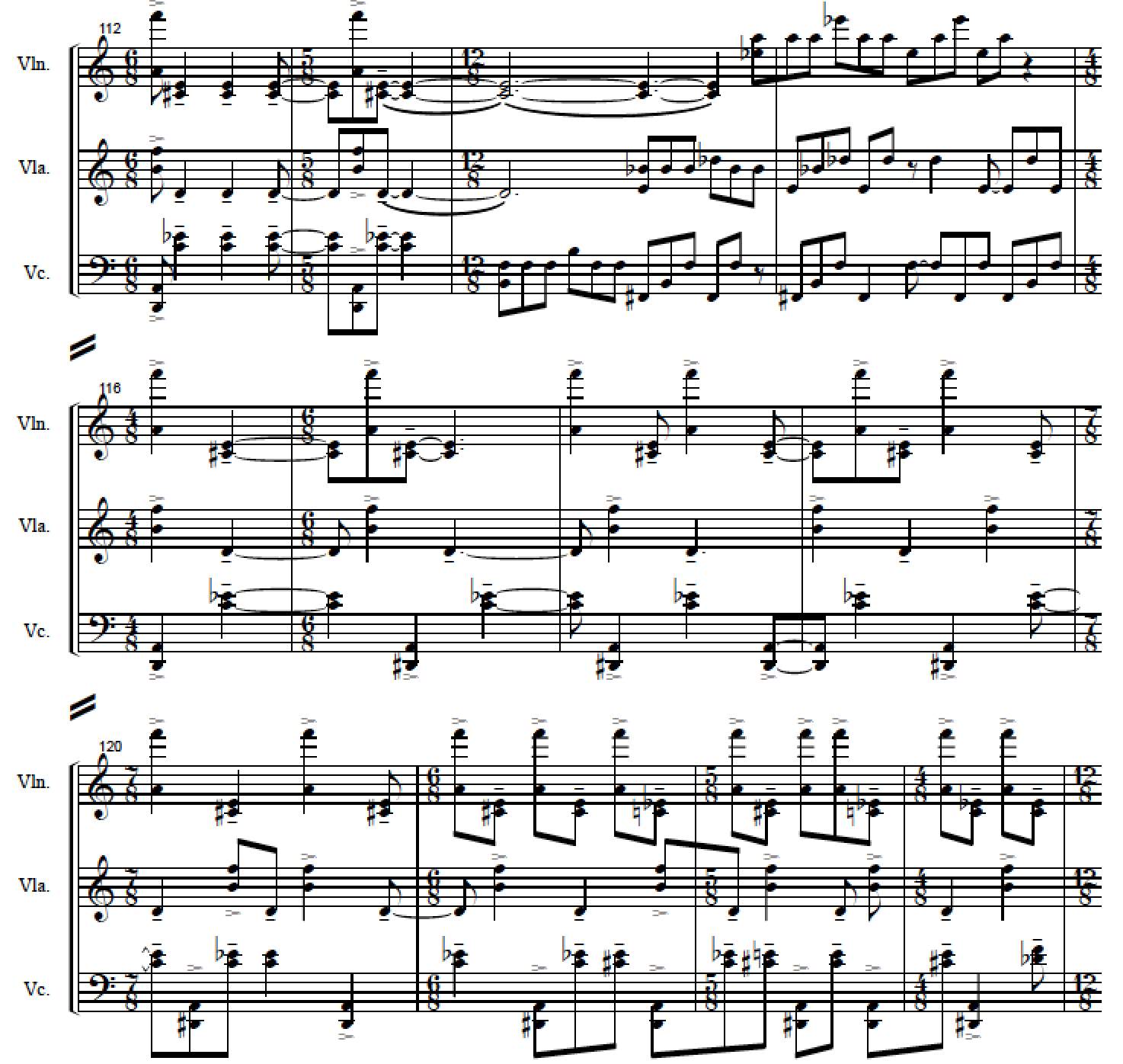

Second, Kim utilized several Korean folk melodies from the Korean folk song, Hanulcheonddazi in his Kangkangsullae.

Example 20. Original Mynyo, Hanulcheonddazi

The melodic theme in measure 1 of Kangkangsullae trio is a traditional Korean folk song, Hanulcheonddazi.

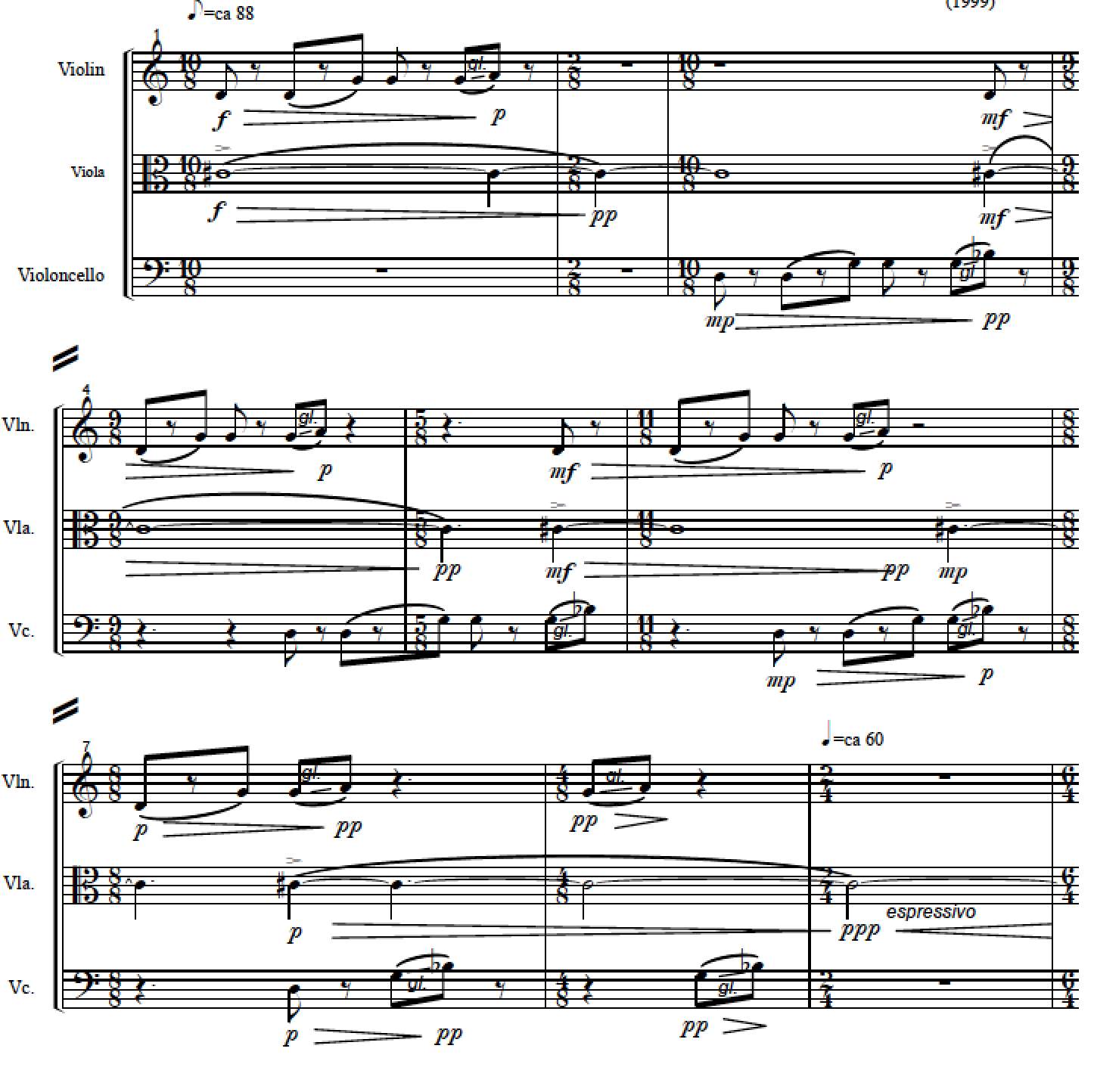

Example 21. Kangkangsullae, m.1

Also, Kim utilized another Korean folk melody from Mynyo in his Kangkangsullae.

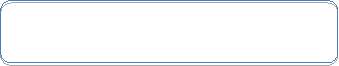

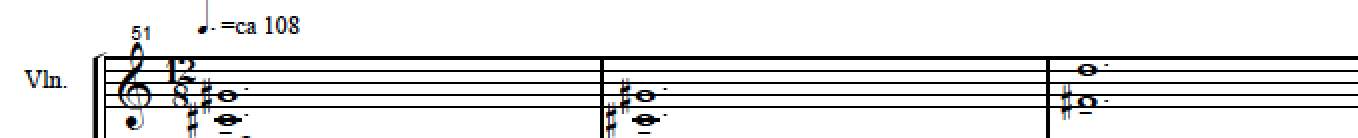

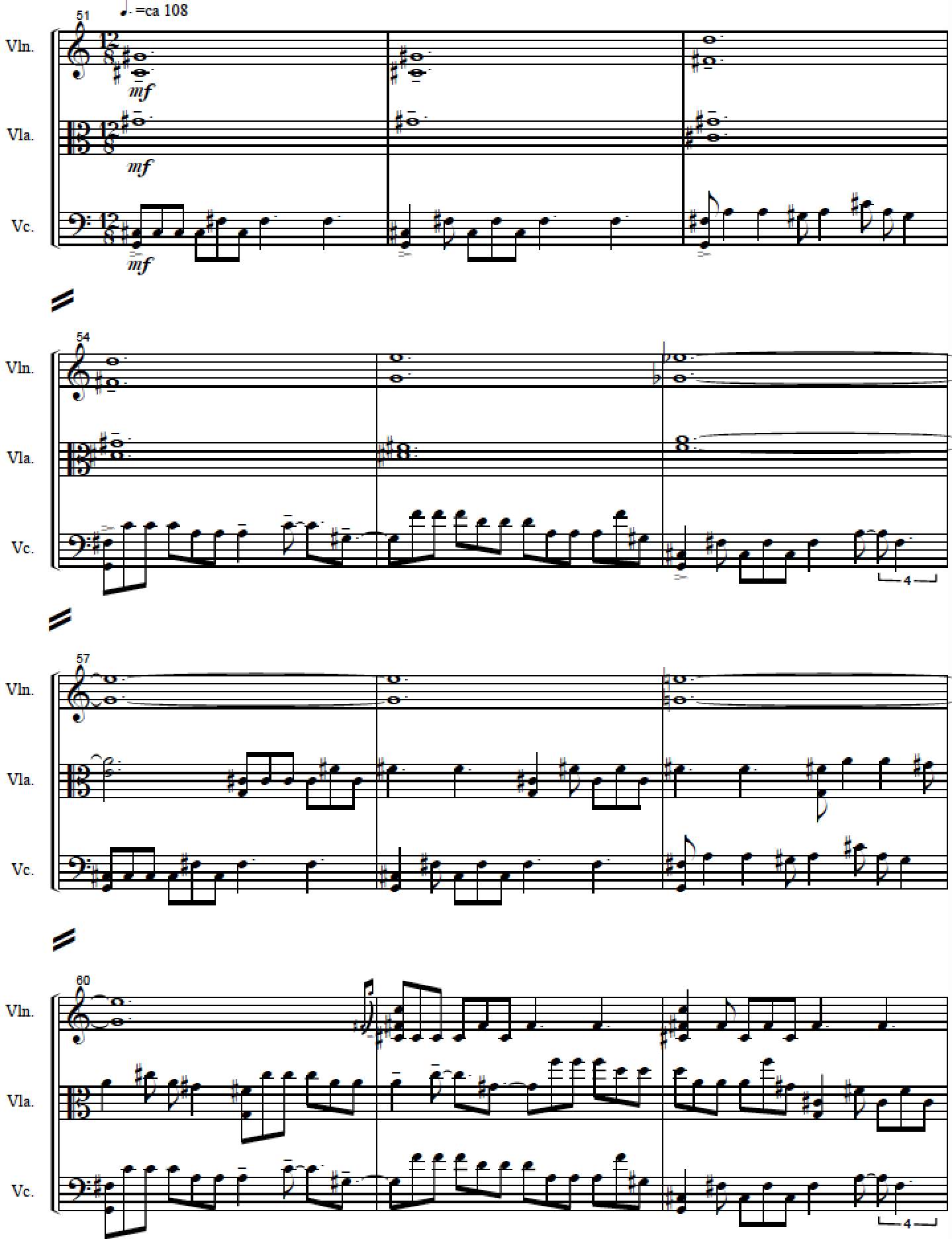

In section three of Kim’s Kangkangsullae, the cello provides six measures of the new theme in mm. 51-56. The cello continues with this theme again in mm. 57-62. The viola also continues the theme in m. 57-63. The violin continues in mm. 61-66 which is a new theme from the original Mynyo, “Kangkangsullae”.[24]

Example 22. Original Korean folk song, Kangkangsullae

The words in Kangkangsullaeare repeated several times in the original song. Song lyrics do exist however, and the lyrics are usually improvised with each dance. The lyrics and dance reflect woman’s emotions such as sorrow, happiness, anger and so on.

The original Kangkangsullae song has a four-measure theme, but Kim applies the four- measure theme and prolongs it by two measures intentionally as a variation.

Example 23. Kim’s new melodies of Kangkangsullae, mm.51-62

Third, ornamentation and embellishments are also one of the characteristics of traditional Korean music. I want to introduce two unique performance techniques for the expression of ornamentation.

The first ornamentation technique is called Sigimsae. These are notes that ornament the main pitch from either below or above the musical note.[25]

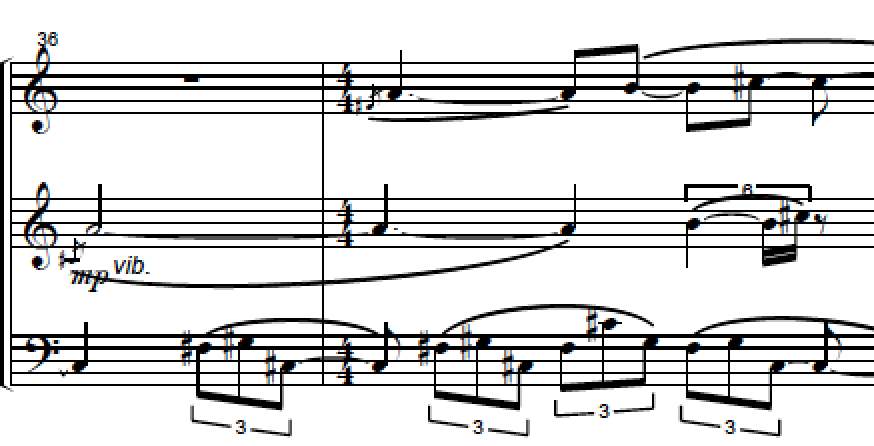

Example 24. Sigimsae ornamentation in Kangkangsullae

m.15 m.25 mm.36-37

m.42-43

Sigimsaeis also present in m.32, 41, 44, 150, and 154.

The other technique is called Nonghyun. Itis also a string ornamentation technique in traditional Korean music for melodic lines. It uses various vibrations and hand movements played on the string. Kim used these Nonghyun techniques to express Eastern sounds in Kangkangsullaetrio.

Nonghyun is represented by glissando and grace notes. Nonghyun contain Chusung, which means glissando from a lower note to higher note and Tosung, which means glissando from a higher note to a lower note. Kim applies a glissando marking to show Chusung.

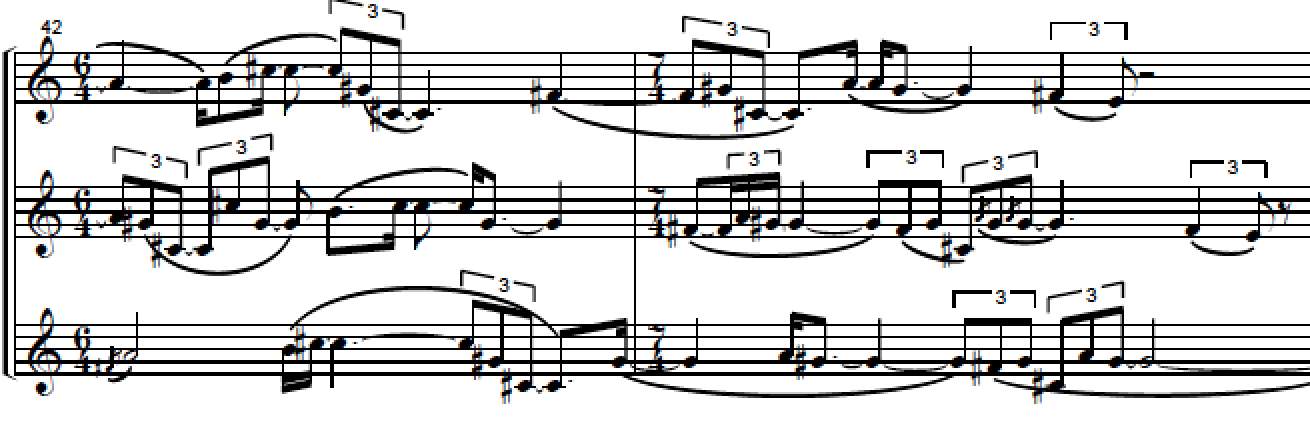

Example 25. Chusung in Kangkangsullae, mm. 1-9

Chusung is also present in mm.10-21.

Tosung appears in the viola part below from C to A sharp and C sharp to A sharp. Kim also applies the glissando marking to express Tosung.

Example 26. Tosung in mm.27-28

Fourth, Samumgae and Oeumgaeare traditional Korean tonality. Samumgae means, “consisting of three pitches.” Kim used this Samumgae at the beginning of the Kangkangsullae in the violin part.

Example 27. Kim’s Kangkangsullae in m.1

Oeumgae means, “consisting of five pitches.” There are three different Oeumgae. The first Oeumgae consists of C, D, E, A, G called Yoojo. The second, Oeumgae contains C, E-flat, F, G, B-flat. The third consists of C, D, F, G, A, which is called Pyeongjo. The Oeumgae scale is similar to Western pentatonic scales.Usually, many pentatonic and monadic melodies are present in the traditional Korean music such as Mynyo and Pansori.[26]

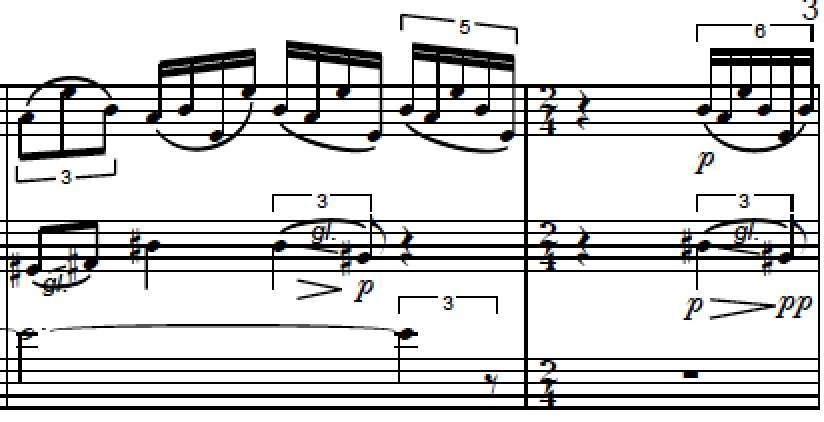

Kim used Oeumgaein his Kangkangsullae, but he used F sharp and B instead of D and E to express the combination of Eastern and Western sounds in m.42.

Example 28. Oeumgaein Kim’s Kangkangsullae m.42

Example 29. Kangkangsullae, m.57

In m. 57, an F-sharp is used instead of a D in the viola and cello parts.

Example 30. Kangkangsullae, mm.61-62

In mm. 61-62, an F-sharp is used instead of an E in the violin, viola, and cello parts.

Example 31. Kangkangsullae, mm.67-69

Also, he used an F-sharp instead of E in mm.67-69.

In m.77, F and B are used instead of G and A.

Example 32. Kangkangsullae, m.77

In m.176, Kim used B-flat instead of a C.

Example 33. Kangkangsullae, m.176

Harmonically, Mynyo usually contains perfect fourths and fifths using three different Oeumgae, which he utilized frequently. Kim introduces the melody with a perfect fourth (D and G) in the violin in measure 1. In mm. 51-52, the violin plays a perfect fifth (C sharp and G sharp). After these measures, Kim uses six intervals to connect to contemporary sounds in m. 53.

Example 34. Perfect fifth interval of Kangkangsullae, mm. 51-53

In mm.209-210, the violin introduces a new theme, which also contains perfect fourths and fifths. The viola follows the theme playing a perfect fourth interval.

Example 35. Kangkangsullae, m. 58

In m. 58, the chord in the cello plays a perfect fourth.

Example 36. Kangkangsullae, m.58

Both the performers and the audiences can hear the contemporary sound that combines both Western and Eastern musical elements.

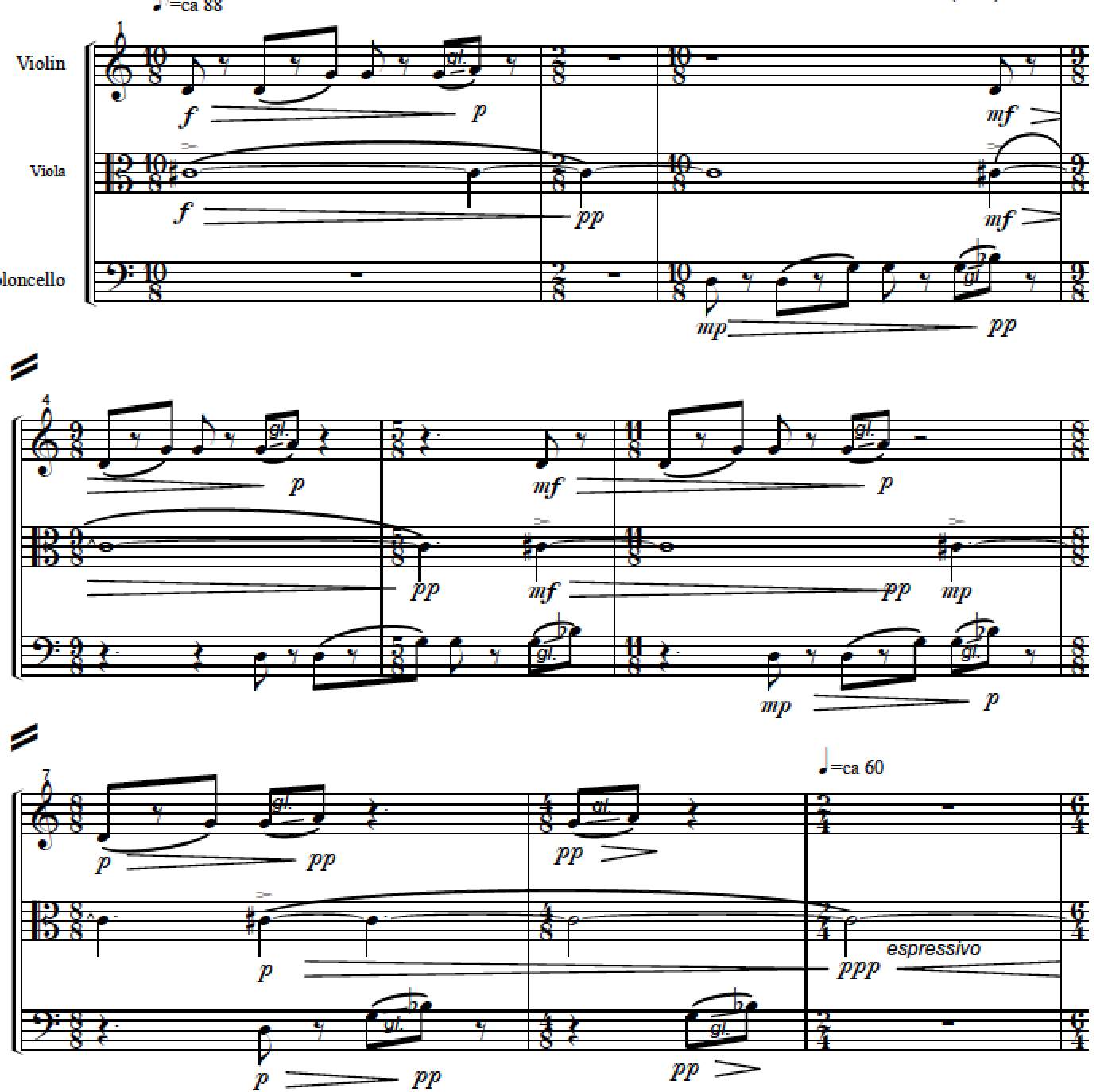

For elements of Western music, Kim develops an imitation using heterophonic techniques in this Kangkangsullae. One of the most important aspects of Kim’s music is characterized by heterophony techniques that appear in 1919. Kim utilizes heterophonic textures based on traditional Korean musical elements in Kangkangsullae. Heterophonic techniques are shown in brackets in the example below.

Example 37. Heterophonic techniques in Kangkangsullae, mm.1-9

Each instrument gives and takes the same phrasal structure. The violin introduces the first theme with three pitches, D, G and A in measure 1. The first theme is comprised of a perfect fourth (G) and fifth (A) from the root D. This theme is played again by the cello in measure 3. These melodic heterophonic techniques are exchanged between the violin and cello parts until measure 7. The melody begins with the violin and is then immediately followed by the viola and cello answering continuously until measure. 7.

Another example of Heterophony can be found from m. 51 to m. 66.

Example 38. Heterophonic techniques in Kangkangsullae, mm.51-66

The cello introduces the new theme from measures 51 to 56. The viola responds with the theme from measures 57 to 62. After that, the violin responds playing the theme from measures 61 to 66. This new theme is from the original Kangkangsullae.[27] It is important for players to pay attention to the phrasing.

Kim also composed Kangkangsullae with more energy, excitement, and life than the original folksong by using Western music elements such as artificial harmonics, sudden changes of pizzicato and arco, Bartok pizzicato, chaconne, accents, and sforzando. The sound of pizzicato is similar to traditional Korean string instruments, the Gayagum and Gumungo. Kim mentions that he did not apply any traditional Korean instruments for Kangkangsullae trio.

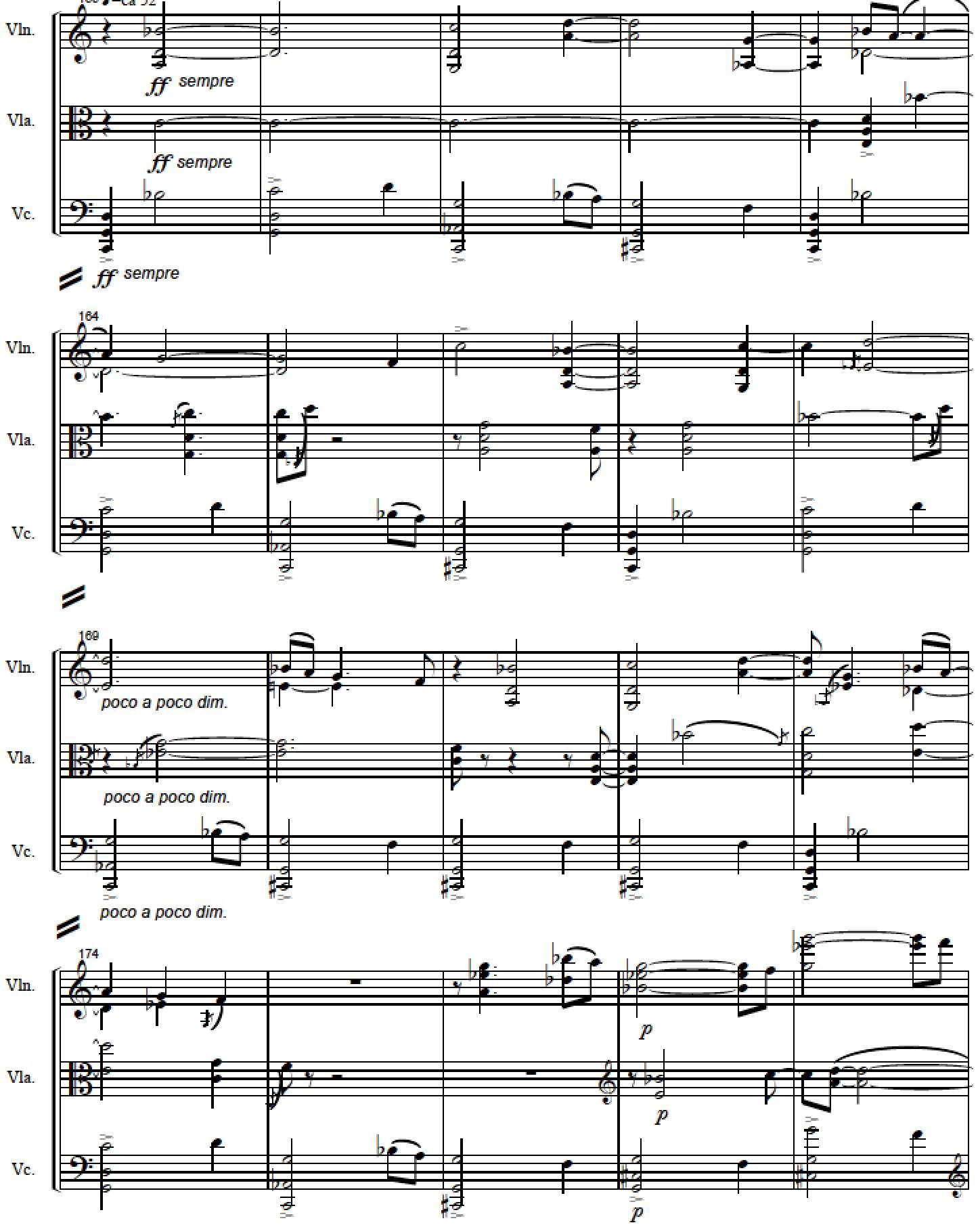

Kim also uses a chaconne in section six in the cello part; a four-measure harmonic progression repeated three times until measure 170. After this, a two-measure harmony prolongs the variation in mm.171-172. Then, the four-measure harmonic progression repeats again. The chaconne applied can be seen in the below example.

Example 39. Chaconne in Kangkangsullae, mm.159-176

This short and harmonic progression repeats four times. Performers should play with a heavy and wide sound.

CHAPTER 5

CONCLUSION

Gideon Gee Bum Kim’s Kangkangsullae is a great example of the combination of music, history, and culture of traditional Korean music and Western compositional styles. Composers who have the ability to combine both Western and Eastern techniques are a valuable asset.

Kim’s music successfully uses harmonized traditional Korean and Western compositional elements, which are helpful for performers to understand his compositional techniques based on traditional Korean music. He utilizes many challenging techniques, such as rhythmic diversity, metric variability, irregular rhythm changes, syncopation, variation of Jangdan, materials from Mynyo, and ornamentations in the Kangkangsullae. For performers, it requires playing highly difficult techniques and an understanding of traditional Korean musical elements.

I provided characteristics of several traditional Korean musical elements that are necessary for performers to understand the cultural, historical, and musical aspects of Kangkangsullae. I also learned about many unique elements of traditional Korean music that I did not know before my research was completed.

Combining both natural musical Eastern and Western elements is difficult and an outstanding feat to create. Therefore, Kim’s Kangkangsullae is a valuable asset for musicians. There is still a lack of data to aid in understanding both Kim’s music and traditional Korean music. The result of this study will provide motivation and an opportunity for musicians to know and perform Kim’s valuable works with the understanding of this beneficial information about traditional Korean music and its cultural and historical background. I believe that this dissertation provides string players with suggestions and ideas about how to interpret and play Gideon Gee Bum Kim’s selected chamber work, Kangkangsullae for violin, viola, and cello.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Books:

Bahk, Daewoung. What is the Rhythm? Seoul: Minsokwon, 2008.

Byeon, Gyewon. The Concept of Composition in Korean Music. Seoul: DongyangeumakPress, 2001.

Chang, Sahun. The History of Korean Music. Seoul: Saekwangeumaksa Press, 1986.

Feliciano, Francisco F. Four Asian Contemporary Composers. Quezon City: New Day Publishers, 1983.

Howard, Keith. Perspectives on Korean Music: Creating Korean music: tradition, innovation, and the discourse of identity. England: Ashgate, 2006.

Hwang, Byung-Ki. Aesthetic Characteristics of Korean Music in Theory and in

Practice. Seoul: Asian MusicPress, 1978.

Kang, Joonman. Korean Modern History. Seoul: Inmulguasasangsa Press, 2007.

Kim, Chunmi, Yonghyan Kim, Youngmi Lee, and Kyeongchan Min. Dictionary of Korean Composers. Seoul: Sigonsa Press, 1999.

Kim, Eunhye. “A study on characteristics of the Korean Folk Song in Flute Works Isang Yun.” Ph.D. diss., Dankook University, 2010.

Kim, Kisu. A Korean Traditional Music Theory Book for Beginners. Seoul: Hangukkojonemak Press, 1972.

Kim, Yong-Hwan. Yun-Isang Yongu II. Seoul: National Korean Arts Conservatory Press, 1997.

Lee, Kangsook. Hanguk Eumakhak: Korean Musicology. Seoul: Minemsa, 1990.

Lee, Hyeku. Triple Meter and Its Prevalence in Korean Music. Edited by Noblitt Thomas. New York: Pendragon Press, 1981.

Pratt, Keith. Korean Music. Its History and Its Performance. London: Farber and Farber, 1987.

Reti, Rudolph. The Thematic Process in Music. New Work: Greenwood Press, 1978.

Song, Hyejin. A Stroll Through Korean Music History. Seoul: National Center for Traditional Performing Arts, 2000.

Tayake, Mayumi. “Performance Guide to Makrokosmos Volume II” Ph.D. diss., University of Washington, 2012.

Whittall, Arnold. Exploring Twentieth Century Music: Tradition and Innovation. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2003.

Journals:

Bowman, Barbara G. “Korean Folk Music in Your Curriculum.” Music Educators Journal 95 (September 2008): 48-53.

Howard, Keith. “Minyo in Korea: Songs of the People and Songs for the People.” Asian Music Vol. 30, no. 2 (Spring-Summer 1999): 1-37.

Dissertations:

Condit, Jonathan. “Sources for Korean Music, 1450-1600.” Ph.D. diss., University of Cambridge, 1976.

Han, Hyunjin. “An Analytical Overview of Min-Chong Park’s Impromptus Pentatoniques for Violin Solo.” DMA. diss., Florida State University, 2012.

Hur, Daesik. “A Combination of Asian Language with Foundations of Western Music: An Analysis of Isang Yun’s SALOMO for Flute Solo or Alto Flute Solo.” DMA. diss., University of North Texas, 2005.

Lee, Koeun, “Isang Yun’s Musical Bilingualism: Serial Technique and Korean Elements in Fünf Stücke für Klavier (1958) and His Later Piano Works.” DMA. diss., University of North Carolina, 2012.

Son, Jihyun. “Pagh-Paan’s No-ul: Korean identity formation as synthesis of Eastern and Western music” Ph.D. diss., University of New York, 2015.

Yi, Chunghan. “A performance Guide to heejo Kim’s Choral Arrangements Based on Traditional Korean Folk Music.” DMA. diss., University of North Texas, 2009.

Internet sources:

“Allargando” Oxford Music Online,

http://www.oxfordmusiconline.com/subscriber/article/opr/t114/e182?q=allargando&search=quick&pos=2&_start=1#firsthit (accessed October 17, 2016).

“Gideon Gee Bum Kim.” Wikipedia

Foundation.https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gideon_Gee-Bum_Kim (accessed September 7, 2016).

“Rubato” Oxford Music Online,

http://www.oxfordmusiconline.com/subscriber/article/opr/t237/e8772?q=rubato&search=quick&pos=5&_start=1#firsthit (accessed October 24, 2016).

[1]Daesik Hur, “A Combination of Asian Language with Foundations of Western Music: An Analysis of Isang Yun’s SALOMO for Flute Solo or Alto Flute Solo” (D.M.A. diss., University of North Texas, 2005), 3.

[2] Jihyun Son, “Pagh-Paan’s No-ul: Korean identity formation as synthesis of Eastern and Western music” (Ph.D. diss., University of New York, 2015), 58.

[3] Chunghan Yi, “A performance Guide to Heejo Kim’s Choral Arrangements Based on Traditional Korean Folk Music” (D.M.A. diss., University of North Texas, 2009), 7.

[4] Koeun Lee, “Isang Yun’s Musical Bilingualism: Serial Technique and Korean Elements in Fünf Stücke für Klavier (1958) and His Later Piano Works” (Ph.D. diss., University of North Carolina at Greensboro, 2012), 29-30.

[5] A Study on Logical Grounds of Music Therapy: Focus on Case Study of Korean Folk Songs, hyesung Im, 2013, page 3.

[6] www.musiccentre.ca/node/37767/biography

[7] www.torontomessiaen.com/ad.html (accessed March 1. 2017.)

[8] A Study on Logical Grounds of Music Therapy: Focus on Case Study of Korean Folk Songs, hyesung Im, 2013, page 3.

[9] Traditional Music: Sounds in Harmony with Nature, Robert Koehler et al.2011, no page

[10] Korean Folk Songs & Folk Bands, Keith Howard, professor University of London, 2003, Koreana Foundation,

[11] Eunhye Kim, “A study on characteristics of the Korean Folk Song in Flute Works Isang Yun” (Ph.D. diss., Dankook University, 2010), 34.

[12] Singing Culture of Koreans: A Multifaceted Soundtrack of Life, Noh dong-eun, winter 2008 Vol.22 No.4

[13] Korean Folk Songs & Folk Bands, Keith Howard, professor University of London, 2003, Koreana Foundation,

[14] Advanced Science and Technology Letters Vol.113 (Art, Culture, Game, Graphics, Broadcasting and Digital Contents 2015), pp.1-4, Fusing Korea and Cuban Rhythms to Derive Rhythm

Contents for Popular Music , Chang Ku Lee, Seungyon-Seny Lee

[15] Jonathan Condit, “Music of the Korean Renaissance,” Songs and Dance of the fifteenth century, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1984, p. 22.

[16] Barbara G.Bowman, “Korean Folk Music in Your Curriculum,” Music Educators Journal 95 (September 2008): 49.

[17] Jihyun Son, “Pagh-Paan’s No-ul: Korean identity formation as synthesis of Eastern and Western music” (Ph.D. diss., University of New York, 2015), 58.

[18] Jaesung Park, ―Korean contemporary music, a brief history. Sonus Vol.20, Spring 2000, 31.

[19] (Phone interview with Gideon Gee Bum Kim. November 14, 2016.)

[20] Barbara G.Bowman, “Korean Folk Music in Your Curriculum,” Music Educators Journal 95 (September 2008): 49.

[21] Jihyun Son, “Pagh-Paan’s No-ul: Korean identity formation as synthesis of Eastern and Western music” (Ph.D. diss., University of New York, 2015), 58.

[22] (Phone interview with Gideon Gee Bum Kim. November 14, 2016.)

[23] (Phone interview with Gideon Gee Bum Kim. November 14, 2016.)

[24] (Phone interview with Gideon Gee Bum Kim. October 26, 2016.)

[25] Eunhye Kim, “A study on characteristics of the Korean Folk Song in Flute Works Isang Yun” (Ph.D. diss., Dankook University, 2010), 34.

[26] Korean music genre that a singer performs with one who plays the Buk, a Korean instrument.

[27] (Phone interview with Gideon Gee Bum Kim. October 26, 2016.)

Cite This Work

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing stye below:

Related Services

View allRelated Content

All TagsContent relating to: "Music"

Music is an art form of arranging sounds, whether vocal or instrumental, in time as a form of expression. Some form of music can be seen in all known societies throughout history, making it culturally universal.

Related Articles

DMCA / Removal Request

If you are the original writer of this dissertation and no longer wish to have your work published on the UKDiss.com website then please: