Transnational Mergers in the Airline Industry and the Hofstede Dimensions

Info: 9503 words (38 pages) Dissertation

Published: 17th Dec 2019

Tagged: Management

Cultural issues accompanying transnational mergers in the airline industry with the example of Air France – KLM

Table of Contents

Introduction

Chapter 1. Transnational mergers in the airline industry and the Hofstede dimensions

1.1 Transnational mergers in the airline industry…………………..

1.2 Cultural issues in mergers and acquisitions……………………

1.3 Hofstede dimensions………………………………..

Applicability to organizational culture

Chapter 2. Analysis of the cultural issues in the airline industry with the example of the merger of Air France-KLM and British Airways-Iberia

2.1 Intra-industry analysis mergers and culture in the aviation industry……..

2.2 Merger Air France-KLM………………………………

2.3 Cultural components of the merger between Air France and KLM………

Chapter 3. Results from the case studies and implications (3350)

3.1 Results from the analysis………………………………

3.2 Recommendations and implications for future transnational mergers…….

3.3 Future research……………………………………

Summary and Conclusion

References

Introduction

There has been a steady increase in the number of transnational mergers over the years, even though not all the mergers prove to be financially successful. Companies have different reasons to choose for a merger. This can be efficiency-related reasons, such as creating economies of scale, or increasing market power or the removal of insufficient management (Andrade, Mitchell & Stafford, 2001). Where in most industries mergers are possible, the airline industry is the odd one standing out. Mergers were prohibited in Europe until 2002 and the first actual merger in the European airline industry was in 2003, which was the merger between Air France and KLM (Regulation 139/2004). Up until this day, mergers between European and American companies are prohibited due to fear of the creation of an oligopoly or even a monopoly (Brueckner & Pels, x). Before the lift of the prohibition, airlines tried to create more efficiency or increase their market power by forming alliances (Brueckner & Pels, x).

As mentioned above, not every merger proves to be financially successful. The literature gives different reasons for this. When a merger has been not successful, the companies conduct an analysis to determine the reason why. The focus of this analysis is often on the financial aspect of the merger and they thus analyse availability, price, potential economies of scale and projected earnings ratios. However, these factors are not sufficient enough to explain why the merger has not been successful and the focus has therefore shifted to the human actor in the merger (Andrade, Mitchell & Stafford, 2001). An important component of the human actor is the organizational culture of the company. Research has shown that there is a relation between the organizational culture and the success of the merger (Cartwright & Cooper, 1993). This gives rise to the question what cultural issues influence the merger.

Since the airline industry have only started to merge after 2002, it’s a very interesting industry to analyse. There are two reasons for this. Firstly, mergers are relatively young and therefore they should be aware of the cultural component of the merger. Secondly, airlines are always nationally based and therefore usually have characteristics of the nation itself. Consequently, mergers between airline companies can be a good indicator to assess how the merger between any company of these nations would turn out. The example this study will use is the merger between Air France and KLM in 2003. In 2017, a report was leaked that stated that the merger did not function properly due to cultural issues (Culture Vulture, 2017). It’s therefore especially interesting to analyse this specific merger for cultural issues. Thus, the research question of this paper will be: what are the cultural issues accompanying transnational mergers in the airline industry with the example of Air France-KLM?

The object if this research is to identify cultural issues accompanying transnational mergers in the airline industry and the subject is what are the specific cultural issues that affect transnational mergers in the airline industry. The goal of this paper is there to analyse the cultural issues that affect transnational mergers in the airline industry and give recommendations based on this analysis for future mergers in the airline industry.

In order to assess whether a company is a cultural fit, the organizational culture of the company must be evaluated (Wilkins, 1984). There are different possibilities to do that and one of them is the Hofstede dimensions of culture. The Hofstede dimensions are: individualism versus collectivism, power distance, masculinity versus femininity, uncertainty avoidance and shot-term versus long-term orientation (Hofstede & McCrae, 2004).

The methodology used in this paper is a qualitative method, namely a case study. A case study allows the exploration and understanding of complex issues. It enables the researcher to examine the data within a specific context (Zainal, 2007). Quality of qualitative research can be assessed in terms of validity, reliability and generalizability. Validity means the ‘appropriateness’ of the tools, processes and data (Leung, 2015). Reliability in qualitative research concerns consistency. This means that when data is extracted from the sources, the researcher must verify their accuracy in terms of form and context with constant comparison (Leung, 2015). Generalizability can be achieved by the use of systematic sampling, triangulation and constant comparison. However, some researchers contest whether qualitative research can be generalizable (Leung, 2015).

Chapter 1. Transnational mergers in the airline industry and the Hofstede dimensions

1.1 Transnational mergers in the airline industry

The institutional and regulatory structure of an economy can influence the economic activity, such as in the aviation sector, where the structure of the economy has a significant impact on the activity in the aviation sector. This entails that when the institutions or regulations change, the aviation sector will react to this change very rapidly (Brueckner & Pels, x). In order to demonstrate this it is important to first outline the international regulations and the regulations concerning M&A in the EU.

Under the 1944 Chicago Convention on international air transportation, each country has exclusive sovereignty over its airspace. Bilateral ASAs between every country pair govern the commercial rights of airlines on international routes (Fu, Oum & Zhang, 2010). The next important international event is the signing of the first open-skies agreement between the Netherlands and the U.S. in 1992. Due to this agreement, both countries have unrestricted landing rights at each other’s airports. The U.S. also granted antitrust immunity to the alliance between Northwest Alliances and KLM Royal Dutch Airlines. After these two events, several other major liberalization events have taken place, such as the establishment of the EU single aviation market in 1992, which compromised the twelve member states of the European Economic Community (EEC). In 2006, the single aviation market evolved into the wider European Common Aviation Area (ECAA), compromised of 35 states in 2006. Effects of the single aviation market where the development of low-cost airlines and increase in competition and consumer choice (Fu, Oum & Zhang, 2010).

Mergers and acquisitions (M&A) are subject to regulations. The reasons for this is the ‘market power hypothesis’. This hypothesis states that when companies merge, the concentration level in a given industry might significantly rise. This could result in a price increase at the expense of the customer (Aktas, Bodt & Roll, 1996). Empirical research has shown that there is increased market power when airlines merge (Kim & Singal, 1933). The M&A regulation in the European Union (EU) is rather new, since the first regulation was created in the 1989, Council Regulation (EEC) No 4064/89 of 21 December 1989 on the control of concentrations between undertakings (Regulation 139/2004). The regulation has remained stable over time and has underwent a significant change only once, in 2004 (Aktas, 2007). Until 2004 the regulatory procedures in the EU concerning M&A were highly standardized. The proposed combining firms had to notify the European Commission within a week after they had reached an agreement. Thereafter, the European Commission had one month to respond to this notification. The European Commission either accepted the merger, accepted the merger with specific conditions or postponed the decisions, in order to do an in-depth investigation (Aktas, 2007). This system changed in 2004, when Regulation 139/2004 of 20 January 2004 on the control of concentrations between undertakings (the EC Merger Regulation) was accepted (Regulation 139/2004). In 2013, a new regulation was published in which the amendments made to the Regulation of 2004 were outlined (Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) No 1269/2013). The most important change in the 2004 Merger Regulation was the introduction of the “significant impediment of effective competition” (SIEC) test (European Commission, x). This test is based on article 2(2) and article 2(3) of the Regulation of 2004. According to the SIEC test, a SIEC arises most prominently through the creation or strengthening of a dominant position. This test allowed the Commission to strengthen its economic analysis of complex mergers and therefore analyse the effect of the merger upon the competition (European Commission, x).

In the 1990s the European air transport was altered due to certain developments. The first development was the emergence of international airline alliances. The rationale for these alliances was to increase the number of intercontinental passengers carried by European airlines. This increase would have beneficial effects on the traffic densities of European airlines and would thus increase cost per passenger, resulting in more profit for the airline. The cause of the rise of airline alliances is globalization of the world economy. This has led to an increase of international passengers, not just for business, but also for leisure. Due to international airline regulation, cross-border mergers were not possible. Airlines could then try to serve more international destinations by expanding their network, but this is constraint by the existing bilateral agreement between countries, that limit the number of carrier that can provide service on any given international route. Passengers are therefore forced to transfer to certain locations. Since the airlines were not able to change this, they decided to improve the quality of interline trips by forming the already mentioned alliances. These alliances led to a decrease in walking distance between gates, a decrease in waiting time between connecting flights, an improvement in the transfer of baggage and a merger of the frequent flyer programs, which allows passengers to earn more miles (Brueckner & Pels, x). Thus, two benefits can be witnessed from the formation of airline alliances from the perspective of the airlines. The first is that it results in an extended network coverage. The second benefit is that an alliance creates a close link between the companies, which forms a fruitful base for more tight forms of cooperation, such as joint ventures or mergers (Gaggero & Bartolini, 2012).

Due to the airline alliances, regulatory concerns in Europe and North America arose (Brueckner & Pels, x). This concern was the result of the following situation. Due to the alliance, there is overlap between a part of the trip. When a passenger travels from point A to C and has to travel through point B, due to international regulations, this passenger can travel with airlines that are part of an international alliance, which would increase the comfort of the journey. This means that there is a combination between an U.S. airline and a European airline. However, although the U.S. airline flies from point A to B to C, the European airline also flies from point A to B. There are thus two carries between point A and B. This has consequences for that group of passengers that have nonstop trips between point A and B. These passengers can make this trip with an U.S. or European airline. Normally the competition between two companies improves the customer’s prospect, but this is not the case in the airline industry. Due to antitrust immunity, the carrier has full scope of cooperation in the fare-setting process. On a route where overlapping service is provided, the result can be anticompetitive. This means that the carrier’s license to cooperate might be used in a collusive manner in the AB city-pair market. In an anticompetitive manner, the carrier can raise the faire, begin aware of the fact that the passengers might have no other choice than to choose this airline. This is the reasons there is regulatory action on alliances. However, as long as the regulatory environment forbids cross-border mergers between the U.S. and European carriers, international alliances are the only way through which the airlines can compete for a larger share of international traffic (Brueckner & Pels, x).

Currently the European airlines have complete pricing freedom and the freedom to enter and exit routes anywhere in the EU. There is also no prohibition on cross-border mergers within the EU (Brueckner & Pels, x). The prohibition on mergers was lifted because there were too many airlines in Europe, which led to inefficient excess capacity. The excess of airlines was the result of the flag-carrier system (Brueckner & Pels, 2005). The flag-carrier system is The cross-border mergers in the EU are a response to low-cost competition that forces the airlines to increase their operating efficiency. These mergers would also allow a rationalization of European route networks. Merged airlines would chose a system by which they choose one base from which they fly to every location, instead of a system by which the airlines flies to every location from his own city. Consequently, traffic densities will rise, which leads to a decrease of the cost per passenger and improve profits. The increase in density would also lead to higher flight frequencies on key routes (Brueckner & Pels, x).

1.2 Cultural issues in mergers and acquisitions

Economic theory has provided possible reasons as to why mergers occur. Firstly, efficiency-related reasons, which often encompass economies of scale or other ‘synergies’. Secondly, an attempt to create market power, which could be done by forming a monopoly or oligopoly. Thirdly, market discipline that is applicable in the case of the removal of incompetent target management. Fourthly, self-serving attempts by management in order to expand the business. Fifthly, to take advantage of opportunities by diversification, for instance by managing risk for undiversified managers (Andrade, Mitchell & Stafford, 2001). Literature in the 1990s has tried to explain why mergers occurs by building upon the two most consistent empirical features of merger activity. The first is that mergers occur in waves and the second one is that within a wave, mergers strongly cluster by industry (Andrade, Mitchell & Stafford, 2001). Another benefit of a merger is the increase in wealth of the shareholders. Empirical evidence has shown that shareholders of acquired firms almost always gain, while the shareholders of acquiring firms do not lose. When the wealth effects of the acquired and acquiring firms are combined, it shows that there is an increase in the stock-market value of the merging firms. This increase may represent value creation or wealth transfers form other stakeholders of the firm. Value creation can arise from different synergistic gains, such as economies of scale or scope, increases in managerial efficiency and improvement in production techniques. The transfer of wealth may arise from other stakeholders and can be losses suffered by bondholders, losses of jobs by employees or a reduction in job wages (Kim & Singal, 1993). Mergers can also only be for defensive reasons in order to protect market share in a declining or consolidating industry (Marks & Mirvis, 2011).

However, most M&A’s are financial failures and produce undesirable consequences for the people and the companies involved. There are positive short-term returns for target-firm shareholders, but investors in bidding firms usually experience share price underperformance in the months following the acquisitions. Research has shown that 83% of all the deals fail to deliver shareholder value and that 53% of the deals destroyed value. Besides that, M&A can be a heavy toll on the employees (Marks & Mirvis, 2011). When the merger fails to realize the financial expectations, the analysis of the merger to determine what went wrong, tends to focus on factors that prompted the initial decisions. The focus of analysis is therefore mainly on availability, price, potential economies of scale and projected earnings ratios. However, these factors are not sufficient to explain why the merger did not meet the financial expectations. Consequentially, there has been an increased focus on the human aspect and its role in determining the merger outcome. A survey, that has been conducted among 200 European chief executives, discovered that the most important factor for a successful merger is the ability to fully integrate the new company. This factor is ranked higher than the financial or strategic factors (Cartwright & Cooper, 1993). Practitioners have also admitted that on the long-run cultural plays a crucial role in determining the success of a merger (Chakrabarti, Gupta-Mukherjee & Jayaraman, 2009).

In order to integrate this component when acquiring a new company, the buyer needs to look beyond the typical approach. Thus, the buyer needs to do a behavioural due diligence (Marks, x).

“Behavioural due diligence: the process of investigating a potential partner’s talent, organizational makeup and culture.”(Marks & Mirvis, 2011)

By conducting a behavioural due diligence, a buyer can understand if the values of the potential partners are compatible (Marks, x).

Organizational culture encompasses symbols, values, assumptions, ideologies that guide individual and business behaviour and it creates order and regularity in the members of the organization (Cartwright & Cooper, 1993). Every company expresses its organizational culture through a clear vision and values that guide the employees (https://www.grin.com/document/342719). The vision defines the future state of the company, where the mission defines the environment in which the firms operates and in which environments it serves its customers (Grant, 2010; Volberda et al., 2011). Values are important concerns that determine group behaviour (Kotter & Hesket, 1992).

Two main streams of management research can be identified, studies that have focused on the pre-acquisition or studies that have focused on the post-merger integration stages. The stream that focuses on the pre-acquisition stage examines the relationship between the firms’ levels of financial measurement and the strategic fit between buying and selling firms. They specifically focus on the added value of the merger or acquisition for the buying company. The second stream, that focuses on the post-merger stage, examines the cultural fit of the buying and selling firm and the impact this has on the success of the merged company. However, research has failed to combine both streams into one research. Even though all stages of the merging procedure are of relevance for the success of the merger (Weber & Tarba, 2012). Previous literature has also shown that cultural differences may enhance the potential synergies of a merger. This happens particularly through the transfer of capabilities, the sharing of resources and learning. However, this happens on the cost of increased integration challenges (Chakrabarti, Gupta-Mukherjee & Jayaraman, 2009). This is supported by another empirical study, which concluded that cross-border M&A had a tendency to perform better when the routines and repertoires of the target country where more distant than those of the acquirer’s (Morosoni, Shane & Singh, 1998).

Having determined that organizational culture is of importance to achieve financial success for a merger, it is important to outline how organizational culture can be measured. As mentioned above, culture consists of values, rituals, heroes and symbols.

“Symbols are words, gestures, pictures or objects that carry a particular meaning within a culture. Heroes are persons, alive or dead, real or imaginary, who possess characteristics highly prized in the culture and who thus serve as models for behaviour.” (Wilkins, 1984)

Rituals are collective activities that are technically superfluous but are socially essential within a culture. Rituals, heroes and symbols can be encompassed by the term practices. The core of the culture is formed by the values. Values in the sense of broad, nonspecific feelings of good and evil, beautiful and ugly, normal and abnormal, rational and irrational. Values cannot be observed, but they are present in the behaviour people portray (Hofstede, Neuijen, Ohayv & Sanders, 1990).

1.3 Hofstede dimensions

A theory that covers culture in an organization are the Hofstede dimensions. The Hofstede dimension have become the standardized tool in business disciplines to assess cultural differences (Chakrabrati, Gupta-Mukherjee & Jayaraman, 2009). Geert Hofstede, a Dutch social psychologist, developed his dimension after a survey among 116,000 IBM employees. This survey included more than 50 cultures. The survey revealed systematic differences among the following four dimensions are the following:

- Power distance index (PDI) is the extent to which the less powerful members of the organization accept and expect that power is distributed unequally.

- Uncertainty avoidance index (UAI) deals with a society’s tolerance for ambiguity. It indicates to what extent a culture programs its members to feel either uncomfortable or comfortable in unstructured situations.

- Individualism versus collectivism (IDV) refers to the degree to which individuals are integrated into groups.

- Masculinity versus feminism (MAS) refers to the distribution of emotional roles between the sexes (Hofstede & McCrae, 2004).

Over the years two extra dimensions have been added:

- Long term orientation versus short term normative orientation (LTO) is linked to how a society deals with its own past while dealing with the challenges of the present and the future.

- Indulgence versus restraint (ND), where indulgence stands for a society that allows relatively free gratification of basic and natural human drives related to enjoying life and having fun. Restraint stands for a society that suppresses gratification of needs and regulates it by means of strict social norms.

There are certain limitations of Hofstede’s Cultural Framework. An obvious limitation is that the data is quite old (data has been collected between 1967 and 1973). Even though the study has been replicated over time, the dimensions might miss important political developments. Moreover, Hofstede’s dimensions are based upon the data of one single company. By generalizing this data, Hofstede assumed that the employees of IBM were representable for the supposed national conformity (McSweeney, 2002; Chakrabarti et al.,).

Hofstede has also developed dimensions of organisational culture. This model is developed in collaboration with his research team in Denmark in the 1980s. The data for these dimensions was gathered through 180 interviews with industry and academic leaders and through a paper-pencil survey among a total of 1500 respondents. These dimensions are based on strategic practices, which can be monitored by the organisation’s management. The model is called the Multi-Focus Model on Organisational Culture and it exists of six autonomous dimensions. These dimensions help us to gather insight on the fit between the actual culture and any strategic direction.

- Means-oriented versus goal-oriented is closely connected to the effectiveness of the organisation, where means-oriented organisation is concerned with the way work is done and this is usually related to a low risk level for employees. Goal-oriented organisation are concerned with the results of the work the employees have to deliver and the employees have a substantial risk level.

- Internally driven versus externally driven is concerned with business ethics and honesty. When an organization has an internally driven culture, employees perform their task on the basis that they know what is best for the customer through their business ethics and honesty. When an organisation has an externally driven culture, the employees aim to meeting the customers’ requirements.

- Easy-going work discipline versus strict work discipline, relates to the amount of internal structuring, control and discipline.

- Local versus professional is related to whether the employee can identify with the boss and/or the unit in which one works. In a local organisation, an employee can identify with his boss, where in a professional organization the identity of an employee is determined by his profession.

- Open system versus closed system is related to the accessibility of an organisation, where in an open system newcomers are immediately welcomed and in a closed system it is the exact opposite.

- Employee-oriented versus work-oriented is related to the management philosophy of the organisation. In an employee-oriented company the employee is central and the organisation takes responsibility for the welfare of the employee. In a work-oriented organisation the work is central and this can come at the expense of the employee (Hofstede insight, n.d.).

Chapter 2. Analysis of the cultural issues in the airline industry with the example of the merger of Air France-KLM and British Airways-Iberia

2.1 Intra-industry analysis mergers and culture in the aviation industry

Research focused on merger and acquisitions in the airline industry has analysed certain components. Firstly, a focus on whether they actually achieve an economy of scale and scope by merging (Barros & Peypoch, 2009). Secondly, a focus has been on advantages and disadvantages of mergers in the airline industry (Iatrou & Oretti, 2007). Thirdly, a focus has been on the advantages and risks of M&A transactions in the airline market (Merkert & Morrel, 2012). Fourthly, a focus has been on the impact of passenger welfare when airline merge (Vaze, Luo & Harder, 2017). Fifthly, research has focused on the influence of geographical location for pre-merger cost structure, synergy estimates and synergy realization (Schosser & Wittmer, 2015).

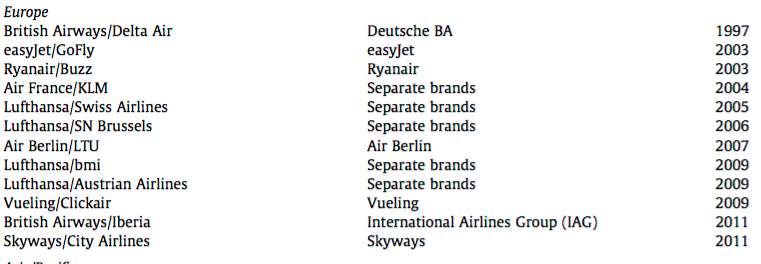

Figure 1. Overview of mergers in Europe since 1997 until 2011 (Merkert & Morrell, 2012).

Through M&A airline companies gain two main cost synergies. The first cost synergy is related to the effects of the cooperation between the companies. Due to the cooperation redundancies of processes, resources or assets can be eliminated. The second cost synergy is related to procurement. By procuring fuel, materials and IT systems as one new company, the costs are less in total, than when these necessities were bought by the separate companies. As a result of the merger or acquisition, the companies bargaining power can also increase. This can have a positive effect on the procurement of the previous mentioned fuel, IT systems and materials. Lastly, through standardizing the fleet, maintenance and training costs can diminish. In addition, an increase in aircraft utilization can be achieved by optimizing the network and flight schedule. Consequently, an economy of density is created and therefore the variable costs are lower (Schosser & Wittmer, 2015). Besides cost synergies, revenue synergies are also a reason for M&A’s in the airline industry. Access to new markets, a larger network, a combination of a frequent flyer program and an increase in market power are factors that lead to revenue synergy (Schosser & Wittmer, 2015). A prerequisite for an optimal revenue, is to that the right size of the airline. The optimal size for an airline is in between 32 billion and 54 billion ASK (available seat kilometres) and an airline that is bigger than 100 billion ASK is too big to operate efficiently. Air France-KLM has a 163.9 billion ASK concerning the time period 2007-2009. This research proposes that airline should merge or acquire a company through which they do not gain more than 100 billion ASK, which entails the company can remain efficient (Merkert & Morrell, 2012).

Research that has been conducted in the aviation industry that has focused on culture, has researched the relation between safety and culture. This arises from the fact that safety plays an important role in the aviation industry and they work with different cultures (d’Agincourt-Canning, Kissoon, Singal et al., 2011; Metscher, Smith & Alghamdi, 2009). Thus, culture plays a significant role in the airline industry, especially since there is a relation between airline safety and culture.

Culture in the airline industry is divided into three different components: national, professional and organizational. All three cultures can have an impact on the safety of the flight. In the aviation industry, some aspects of national culture are analysed through the Hofstede dimensions. The professional culture influences how one executes their job as effective as possible through feelings of responsibility and dedication and the professional pilot culture reflects what attitudes and values are associated with the pilot profession. The organizational culture assesses how the organization influences the people within that specific organization. It is the overarching layer of the national and professional culture, since both cultures operate within the organizational culture (Metscher, Smith & Alghamdi, 2009).

Pilots have three cultures that shape their actions and are attitudes that should be considered. The first culture is the national culture. The second culture is the professional culture of the pilot profession. The third culture is the organizational culture, which is the closest to the daily life of the pilots. All these three cultures influence the pilot in a critical situation. Also, culture shapes the pilots attitude towards stress and it influences the pilot’s personal capabilities (BAA Training, 2013; Metscher, Smith & Alghamdi, 2009).

2.2 Merger Air France-KLM

Currently, KLM Royal Dutch Airline is the oldest airline still operating under its original name and base. The company was founded in 1919 by Albert Plesman, a Second Lieutenant in the Netherlands Air Force. The airline grew rapidly, which is demonstrated by their first intercontinental flight in 1924 (Netherlands-Indonesia) and the fact that KLM was the first European airline to launch an air service across the Atlantic Ocean (Amsterdam-New York) in 1946 (Gudmundsson, 2014). KLM offers at the moment 133 destinations in 66 countries on six continents and it’s a group. The group exist of KLM, KLM Cityhopper and Transavia. As a group. they have four core activities: passenger transport, cargo transport, engineering and maintenance and the operation of charters and low cost/low fare scheduled flights. The goal of the company is to be the customer’s first choice passenger and cargo airline, this while providing maintenance service and consistently enhancing shareholder value (Gudmundsson, 2014).

In the beginning the Dutch State owned the majority of the outstanding capital stock. This was reduced to 38% in March 1986. Over the following years there would be a further reduction of state ownership which resulted in a 25% ownership of the Sate in 1996. In 1998, the remaining shares were converted and transferred to the Netherlands Aviation Interests Foundation. However, the Sate continued to own the majority of the outstanding Priority Shares. Consequently, they were given certain rights in the governance of the company. Thus, the Dutch State maintained an interest in the company through the holding of priority shares, but it no longer participates in the company’s decision making (Gudmundsson, 2014).

Air France was established in 1933 through the combination of five French airlines. At this point in time they covered Europe, the Mediterranean region and South America and their priorities as a brand-new airline were comfort and safety. The second world war interrupted their expansion and by the end of 1945 Air France became state-owned. By this time, they had the largest network of the world, covering 160000 km. In 1946 Paris-New York route was officially integrated and in 1948 Air France became a National Company. As a consequence of the economic crisis the Air France Group was established in 1990, which consists of Air France, UTA and Air Inter. In this period, Air France also expanded through partnership, such as the partnership with Delta Air Lines. This partnership was transformed into a global alliance in 1999, when Air France and Delta Airlines signed a long-term agreement. This was followed by another global alliance, the SkyTeam on the 22nd of June 2000. The four airlines were Aeromexico, Air France, Delta Air Lines and Korean Air. The alliance was completely focused on customers and aimed at meeting their expectations with high quality and seamless service (http://www.museeairfrance.org/en/the-history-of-air-france).

A year before the merger between Air France and KLM, KLM was not doing well. The situation is well described by the CEO of KLM, Leo van Wijk:

“..there are hardly any opportunities to generate more reveneus. We aren’t growing and higher fares are out of the question in this incredibly competitive market. If you take all these factors together, you see our prospects are not very bright.”[1]

Potential synergies have been identified by Air France and KLM and these should result in a growing annual improvement of €385-495 million on the Group’s consolidated operating income. The synergies would be: network optimization, improved organization of passenger and cargo operations, an expanded offering of maintenance services, cost reduction in purchasing, sales distribution and IT applications. For the customers, the merger would result in an expanded network, attractive fares and enhanced service on all the new Group’s flights (Gudmundsson, 2014). Air France-KLM has three core businesses: passenger, cargo business and engineering & maintenance (https://www.klm.com/corporate/en/about-klm/profile/). In May 2004, Air France and KLM establish the grounds for their merger in a Framework Agreement. A new holding is being formed, Air France-KLM. This holding controls the shares of Air France and KLM. Both airlines continue to work rather independent from each other and this is evidently shown in their new motto: ‘One group, two airlines, three businesses.’ A very interesting component of the Framework Agreement is that not integration is the goal, but coordination between the two airlines. This entails that integration only occurs when it is deemed absolutely necessary and there are good reasons for integration, such as the integration of the financial communication department of KLM by Air France. In many areas coordination is the goal and consequently, many areas operate independently from the other.

On the website of KLM, the KLM Culture is described as follow: “Passion, energy, drive and brainpower are common traits of KLM team members” (KLM Culture – Jobsite, n.d.).A lot of employees have a strong connection with the KLM brand and this feeling is called ‘the blue feeling’ (het blauwe gevoel). KLM is a combination between Dutch reliability and an international feeling. After analysing interviews that have been conducted among KLM personnel, two different sets of characteristics become evident. The first set of characteristics is that KLM is dynamic, commercial, entrepreneurial, pragmatic and opportunistic. The other set is that KLM is bureaucratic, hierarchic and not-flexible (KLM Culture – Jobsite, n.d.).

2.3 Cultural components of the merger between Air France and KLM

In the beginning of the merger the issues that can arise due to cultural differences are acknowledged, but the top managers are hesitant to take action. Since there is a lot of media attention in the Dutch press concerning the merger with a French company and Air France has experience with the American company Delta Air Lines, the companies decide to hire an international consultancy group to do a culture scan. In February 2004, the consultancy provides the two airlines with a report that outlines the differences between Air France and KLM and makes clear where attention is required and risks could occur. The most important point in the rapport concerns the vertical relations in the companies. When making decisions reaching consensus is very important for KLM, where Air France has a hierarchical decision making process. Related to this point is the difference in delegation and empowerment. At KLM decisions can be made at a lower management-level than at Air France, there is thus more delegation at KLM than at Air France. Managers at KLM are used to receive comments or suggestions from their subordinates. This in contrast with Air France, where the relation between the manager and the subordinate is more separated. The orientation towards time also differs between the companies. Being a Dutch company, KLM has a monochromic time orientations. This entails that they focus on one thing only, where Air France, as a French company, has a polychromic time orientation and that entails that they do several things simultaneously. Related to the time orientation is the difference in attitude concerning quick wins, KLM, and long-term strategy, Air France. Concerning the planning and preparation of policy there are also some differences. Employees of KLM have a tendency to start with the process that should eventually lead to a decision. Employees of Air France start with the exploration of the content of the decision that has to be taken (Noorderhaven, Kroon & Timmers, 2010).

As a consequence of the rapport, the management decided to offer cultural workshops to the employees that will work with the merging partner. The workshops are aimed at enhancing the awareness of cultural differences, especially concerning the communication between the two companies. A consultancy company specialized in intercultural communication is hired and 1,500 employees of Air France and KLM have a workshop. The workshops are aimed at creating awareness of cultural differences. Two other initiatives are established by the company. These initiatives are not directly aimed at diminishing cultural differences, but they do contribute to diminishing the cultural differences. Firstly, an exchange program is established for young professionals. 10 managers of KLM go to Paris to work there for two years and 10 managers of Air France go to KLM to remain there for two years. This would enable the young professionals to learn from the other company and culture, At the end of the exchange program, the young professionals create a book, the Cultural Navigator, in which they clarify the main differences between each side of the company and how miscommunications can occur as a result of that. The second initiative is a training for senior managers and high potentials organised by IMD Lausanne and HEC Paris. These trainings provide the participants with a content wise and a behavioural program. However, the exact effect of these two initiatives concerning diminishing cultural differences is hard to measure (Noorderhaven, Kroon & Timmers, 2010).

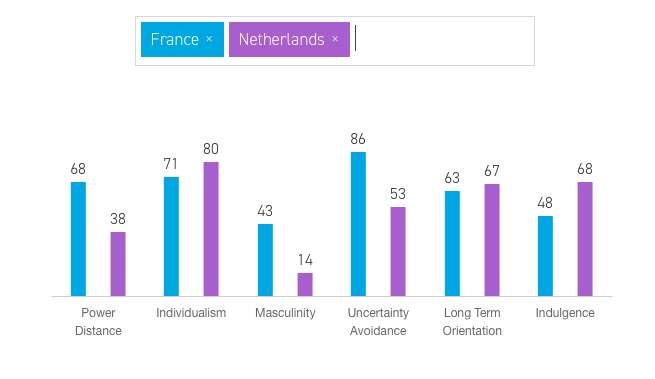

Figure 2. The six dimensions’ model of Hofstede applied to the Netherlands and France (Hofstede insights, n.d.)

The above figure shows the difference in the national cultures of France and the Netherlands. The main differences are in power distance, masculinity, uncertainty avoidance and indulgence. These results are not surprising, since the above analysis of the merger between Air France and KLM showed similar differences between the companies (Hofstede insights, n.d.).

An Air France-KLM report that was leaked in 2017 showed that the French and Dutch people of the company experience a culture clash. The report is written by a French and Dutch researched who spoke to 50 managers at the airline company. According to this report, the French view the Dutch as money-grabbing, meaning that the Dutch would do anything to gain more profit. According to the Dutch, the French are too attached to hierarchy and care more for political interests, which are not always in line with the interests of the company. Both KLM and Air France managers accuse the other side of only worrying about their own company (Boffey, 2017; Culture Vulture, 2017).

Chapter 3. Results from the case studies and implications (3350)

3.1 Results from the analysis

Air France-KLM has invested in assessing the cultural differences pre-merger through a cultural analysis of the company and intercultural communication training for the employees. However, the leaked rapport of 2017 shows that the cultural differences are more than present. Even though, Air France-KLM initially invested in creating awareness for cultural issues, evidence has not been found that Air France-KLM invested in this as well post-merger. A reason for the culture clash could be that the company only invested in raising cultural awareness pre-merger and not post-merger.

3.2 Recommendations and implications for future transnational mergers

The European airline industry faces several challenges, due to the growth of price-competitive low-cost carriers and because Middle Eastern and Asian full-service airlines are becoming more attractive in Europe, due to advantages in costs and quality of service. However, due to the fragmented nature of the European airline industry, opportunities for airlines to collaborate and consolidate arise. Collaborations and consolidation would enable airlines to reduce costs and build scale. In addition, the airlines would also be able to expand their routes, which would lead to additional business and thus additional profit (Canelas & Ramos, 2016; Rivers, 2016).

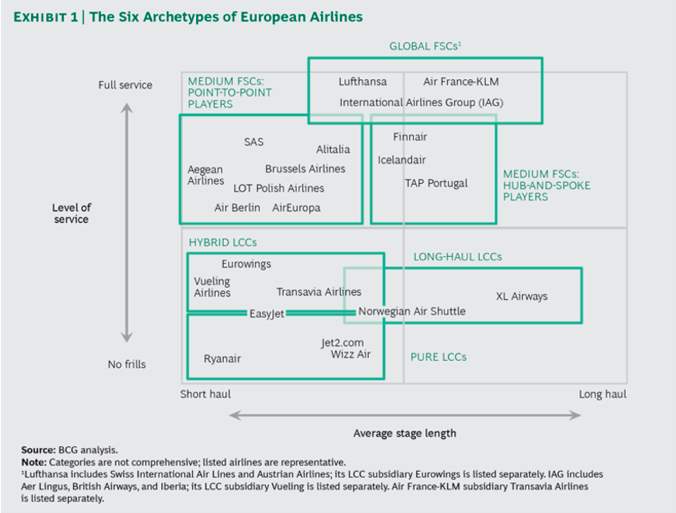

Currently, the market in Europe exists of six types of airlines, each with their own strategic strengths and needs.

Figure 3. The six archetypes of European Airlines (Canelas & Ramos, 2016).

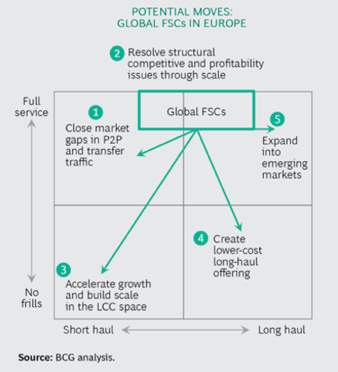

Concerning strategic growth, five options have been identified for Global FSCs, such as Air France-KLM.

Figure 4. The five options of strategic growth for Global FSCs (Canelas & Ramos, 2016).

Within each strategic move, certain options for collaboration or consolidation are available. The strategic moves move along a continuum of low complexity to high complexity, where low complexity is organic growth and high complexity is a full merger (Canelas & Ramos, 2016) However, consolidation in the European airline industry is challenging, due to the differences in languages, fiscal structure and legal system (Rivers, 2016).

Global FSCs have a need to resolve their structural competitive and profitability issues. These issues can be improved by expanding their network and by increasing their sale. M&A are probably the fastest option for these companies to achieve this (Canelas & Ramos, 2016; Merkert & Morrell, 2012). However, as demonstrated by this paper and previous research, mergers can be difficult to manage and are not always successful. For a successful merger, not only financials need to be taken into account, but also the culture of the company and whether the companies are a cultural fit. This could be done by not only analysing the financial situation of the company before the merger, but also the cultural situation of the company. Thus, cultural components should be integrated in the process of analysing a company pre-acquisition and cultural components should be analysed to create success post-merger. This is specifically of relevance for the airline industry, where culture already plays an important role in the daily functioning of the company. Not only transnational barriers are preventing the success of M&A in the airline industry such as national foreign ownership rules, but the increase in antithrust authority scrutiny forms another substantial barrier (Merkert & Morrell, 2012).

3.3 Future research

This was paper was unfortunately only able to analyse one merger in the airline industry, namely Air France and KLM. However, in order to make this research more applicable to the airline industry, more mergers in the airline industry must be researched. As a result, a more complete overview of important cultural issues that accompany mergers in the airline industry can be created.

Another interesting point of future research is to assess what potential mergers between a company and Air France-KLM could be. After this first initial step, the cultural issues that could accompany such a merger could be analysed and assessed.

Summary and Conclusion

References

Aktas, N., Bodt, E., and Roll,R. (2007). Is European M&A Regulation Protectionist? The Economic Journal,117(522), 1096-1121.

Andrade, G. M., Mitchell, M. L., & Stafford, E. (Spring 2001). New Evidence and Perspectives on Mergers. The Journal of Economic Perspectives,15(2), 103-120. doi:10.2139/ssrn.269313

Brueckner, K. and Pels, E. (_). Institutions, Regulation and the Evolution of European Air Transport. Advances in Airline Economics 2, edited by Darin Lee : 1.

Cartwright, S., and Cooper, C. (1993, May). The Role of Culture Compatibility in Successful Organizational Marriage. The Academy of Management Executive (1993-2005)7(2), 57-70.

Chakrabarti, R., Gupta-Mukherjee, S., and Jayaraman, N. (2009, February-March). Mars-Venus marriages: Culture and cross-border M&A. Journal of International Business Studies,40(2), 216-236.

Council of the European Union, “Regulation 139/2004 of 20 January 2004 on the control of concentrations between undertakings (the EC Merger Regulation)”. Official Journal of the European Union L24, 1. http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32004R0139&from=EN

D’Agincourt-Canning, L. G., Kissoon, N., Singal, M., & Pitfield, A. F. (2010). Culture, Communication and Safety: Lessons from the Airline Industry. The Indian Journal of Pediatrics,78(6), 703-708. doi:10.1007/s12098-010-0311-y

Denison, D., & Mishra, A. (1995, March – April). Toward a Theory of Organizational Culture and Effectiveness. Organization Science,6(2), 204-223.

European Commission, “White paper towards more effective EU merger control”, http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52014DC0449&from=EN

Flores-Fillol, R., and Moner-Colonques, R. (2007, September). Strategic Formation of Airline Alliances. Journal of Transport Economics and Policy,41(3), 427-449.

Gaggero, A., and Bartolini, D. (2012, September). The Determinants of Airline Alliances. Journal of Transport Economics and Policy,46(3), 399-414.

Groningen, E., & Rothman, A. (2016, July 04). The Dutch Half of Air France-KLM Isn’t Happy with the French Half. Skift. Last seen 24th of March 2018.

Gudmundsson, S. (2014, June). Mergers vs. Alliances: The Air France-KLM Story. Toulouse Business School, 1-34.

Hofstede, G. (1983, Spring – Summer). National Cultures in Four Dimensions: A Research-Based Theory of Cultural Differences among Nations. International Studies of Management & Organization,13 (½), 46-74.

Hofstede, G., & McCrae, R. (2004, February). Personality and Culture Revisited: Linking Traits and Dimensions of Culture. Cross-Cultural Research,38(1), 52-88.

Hofstede, G., Neuijen, B., Ohayv, D. D., & Sanders, G. (1990). Measuring Organizational Cultures: A Qualitative and Quantitative Study Across Twenty Cases. Administrative Science Quarterly,35(2), 286-316. doi:10.2307/2393392

Han, K.E., & and Singal, V. (1993, June). Mergers and Market Powers: Evidence from the Airline Industry. The American Economic Review, 83(3), 549-569.

Leung, L. (2015, July). Validity, reliability, and generalizability in qualitative research. Journal of Family Medicine and Primary Care,4(3), 324-327.

Marks, M., and Harris, P. (2011, June). Merge Ahead: A Research Agenda to Increase Merger and Acquisition Success. Journal of Business and Psychology,26(2), 161-168.

Marks, M., Harris, P., & Brajkovich, L. (2001, May). Making Mergers and Acquisitions Work: Strategic and Psychological Preparation (and Executive Commentary). The Academy of Management Executive (1993-2005),15(2), 80-94.

Mcsweeney, B. (2002). Hofstedes model of national cultural differences and their consequences: A triumph of faith – a failure of analysis. Human Relations,55(1), 89-118. doi:10.1177/0018726702055001602

Merkert, R., & Morrell, P. S. (2012). Mergers and acquisitions in aviation – Management and economic perspectives on the size of airlines. Transportation Research Part E: Logistics and Transportation Review,48(4), 853-862. doi:10.1016/j.tre.2012.02.002

Metscher, D., Smith, M., & Alghamdi, A. (2009) Multi-Cultural Factors in the Crew Resource Management Environment: Promoting Aviation Safety for Airline Operations. Journal of Aviation/Aerospace Education & Research,18(2), 9-16.

Morosini, P., Shane, S., and Singh, H. (1998, 1st Quarterly). National Culture Distance and Cross-Border Acquisition Performance. Journal of International Business Studies,29(1), 137-158.

Noorderhaven, N., Kroon, D., & Timmers, A. (2010). KLM na de fusie met Air France: cultuurverandering in het perifere gezichtsveld. In J. Boonstra (ed.), Leiders in cultuurverandering: hoe Nederlandse organisaties succesvol hun cultuur veranderen en strategische vernieuwing realiseren(Cahier 3). Assen: van Gorcum.

Sørgard, L. (2009, September). Optimal Merger Policy: Enforcement vs. Deterrence. The Journal of Industrial Economics,57(3), 438-456.

Schosser, M., & Wittmer, A. (2015). Cost and revenue synergies in airline mergers – Examining geographical differences. Journal of Air Transport Management,47, 142-153. doi:10.1016/j.jairtraman.2015.05.004

Zainal, Z. (June 2007). Case study as a research method. Journal Kemanusiaan,9, 1-6.

Brueckner, J. K., & Pels, E. (2005). European airline mergers, alliance consolidation, and consumer welfare. Journal of Air Transport Management,11(1), 27-41. doi:10.1016/j.jairtraman.2004.11.008

Vaze, V., Luo, T., & Harder, R. (2017). Impacts of airline mergers on passenger welfare. Transportation Research Part E: Logistics and Transportation Review,101, 130-154. doi:10.1016/j.tre.2017.03.005

Xiaowen F., Oum, T.H., and Zhang, A. (2010, Fall). Air Transport Liberalization and Its Impacts on Airline Competition and Air Passenger Traffic. Transportation Journal,49 (2), 25.

COMMISSION IMPLEMENTING REGULATION (EU) No 1269/2013 of 5 December 2013 amending Regulation (EC) No 802/2004 implementing Council Regulation (EC) No 139/2004 on the control of concentrations between undertakings

ulation 139/2004 of 20 January 2004 on the control of concentrations between undertakings (the EC Merger Regulation)

European Commission, “White paper towards more effective EU merger control”, 4.

BAA Training. (2013, May 29). The importance of organizational culture in Aviation. Retrieved from https://www.baatraining.com/the-importance-of-organizational-culture-in-aviation/

Bechai, D. (2016, June 10). Air France-KLM: An Unhappy Marriage. Retrieved April 29, 2018, from https://seekingalpha.com/article/3981195-air-france-klm-unhappy-marriage

Canelas, H., & Ramos, P. (2016, August 17). Consolidation in Europe’s Airline Industry. Retrieved April 28, 2018, from https://www.bcg.com/publications/2016/mergers-acquisitions-divestitures-joint-ventures-alliances-consolidation-in-europe-airline-industry.asp

National Culture. (n.d.). Retrieved April 29, 2018, from https://www.hofstede-insights.com/models/national-culture/

KLM Company profile – KLM Corporate. (n.d.). Retrieved March 29, 2018, from https://www.klm.com/corporate/en/about-klm/profile/

KLM Culture – Jobsite. (n.d.). Retrieved March 29, 2018, from https://www.klm.com/jobs/en/over_klm/klm/klm_cultuur/index.html

Organisational Culture. (n.d.). Retrieved April 29, 2018, from https://www.hofstede-insights.com/models/organisational-culture/

Rivers, M. (2016, April 29). Lufthansa Beats The Merger Drum, But Are Europe’s Airlines Ripe For Consolidation? Retrieved April 29, 2018, from https://www.forbes.com/sites/martinrivers/2016/04/29/lufthansa-beats-the-merger-drum-but-are-europes-airlines-ripe-for-consolidation/#43c9885a32ca

The history of Air France. (n.d.). Retrieved March 29, 2018, from http://www.museeairfrance.org/en/the-history-of-air-france

Vulture, C. (2017, July 21). Cultural Differences Troubling Air France-KLM Merger. Retrieved April 29, 2018, from https://www.commisceo-global.com/blog/cultural-differences-troubling-air-france-klm-merger

[1] Leo van Wijk, CEO of KLM (2002).

Cite This Work

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing stye below:

Related Services

View allRelated Content

All TagsContent relating to: "Management"

Management involves being responsible for directing others and making decisions on behalf of a company or organisation. Managers will have a number of resources at their disposal, of which they can use where they feel necessary to help people or a company to achieve their goals.

Related Articles

DMCA / Removal Request

If you are the original writer of this dissertation and no longer wish to have your work published on the UKDiss.com website then please: