Wes Anderson Films: Style Over Substance?

Info: 9623 words (38 pages) Dissertation

Published: 26th Aug 2021

Tagged: Film Studies

Does the safety and reassurance of a Wes Anderson film limit its narrative potential?

TABLE OF CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION......1

ACTORS AND CREW......2

ATMOSPHERE......3

AUTEUR DIRECTING.....6

PLANIMETRIC STAGING AND COMPOSITION......8

DOUBLE FRAMING AND RATIO......12

GOD’S EYE VIEW......17

LATERAL TRACKING AND DOLL’S HOUSE SHOTS......20

LATERAL WHIP PAN......22

CUTTING AND SHOT LENGTH......23

SLOW MOTION......24

CONCLUSION: STYLE OVER SUBSTANCE?......25

BIBLIOGRAPHY......27

DISTILLATION......32

INTRODUCTION

With eight feature films over 18 years, Wes Anderson has established himself as one of American cinema’s most distinctive filmmakers of this generation. From his first feature Bottle Rocket (1996), his stop-motion animation The Fantastic Mr. Fox (2009), to his most recent four-time Oscar Winner The Grand Budapest Hotel (2014), he is a director who never fails to divide people’s opinion. His immense attention to detail and the mixing of contrasting genres – comedy and tragedy – often feel hedonistic to some of his audience. Whereas for others, Anderson has a quirky, unique and visionary sense of humour, teamed with an unparalleled imagination.

Remarkably knowledgeable in his film history and technique, Anderson is a classic example of an auteur filmmaker, a term that was coined by the critics from the magazine Cahiers du Cinéma. This refers to an artist who strongly imprints their own personality and idiosyncrasies onto their work, overriding the influences of other contributors. (Seitz, 2009)

Wes, arguably, has the most distinct look in cinema with his infamous symmetrical style, frequent use of the overhead shot, saturated colour palettes, Futura Bold title cards, family issues, and a recurring ensemble cast. One of the most signature traits belonging to Anderson is his consistency of organising elements in the frame, making sure that the most important thing is, more or less, dead centre. Directors are taught to avoid symmetry as it feels too theatrical and that an asymmetrically framed shot has a natural visual dynamism to it, but if you have watched any of Anderson’s films, you will know that seeming artificial and contrived has never been one of his concerns. (Crow, 2014)

But does his stylistic mise-en-scène impact the storytelling? Is the audience so captured by all his clever visuals that they fail to understand the story and the meaning of the film? This essay examines some of Wes Anderson’s many cinematic influences and his attempt to combine them to create his uniquely personal visual style. Additionally, it explores whether his repetitive and memorable style is as, or more, important than the substance and narrative of his films.

ACTORS AND CREW

After the release of his second film, Rushmore, in 1998, it became obvious that Anderson was an idiosyncratic filmmaker worth discussing. Not only does he have an immediately identifiable mise-en-scène, but retains the same cast, crew, and even some collaborators too.

In an interview that Wes Anderson did in 2014, he was asked…

“You often work with the same people… Why do you like working with the same actors again and again?”

WA: “Well, these are obviously great actors, so that’s quite an incentive. But also, I think these stories are just suited to having well-known faces play these parts… like having an old-fashioned company of actors on stage.”

(Economist.com, 2014)

Giving Anderson what he wants isn’t easy, though. Actor Jeff Goldblum says, “He does a lot of takes”. Every prop, every frame, and every actor’s line must be correct. There is no improvising, no interfering with the script and very little room for actors to suggest improvements. In The Grand Budapest Hotel (2014), Saoirse Ronan, who plays the female lead Agatha, said she had never seen anything like it:

“There was one shot… It was the hardest thing I’ve ever had to do,” she said. “It took 35 takes or something. We just did it over, and over, and over, and over again.”

(The Daily Beast, 2014)

Ralph Fiennes, who made his Wes Anderson debut as the concierge Gustave H. in The Grand Budapest Hotel, said Wes’ obsessive compulsion to recreate each scene exactly as he planned it is heightened as he is both the writer and director. If, for example, Anderson was purely the writer, the director would then have more control over the development of roles. But Wes is incredibly “controlling” over his script, and would notice if an actor changed a line by mistake. (The Daily Beast, 2014) As Fiennes said,

“Wes is someone I think who hears [the lines] very distinctly, he hears the rhythms, he hears the delivery, he hears the comic timing of it”.

(The Daily Beast, 2014)

Along with a similar cast ensemble, in terms of Anderson’s storylines, he also almost solely focuses on the white, straight and privileged as they go about their problematic and troublesome lives. He rarely casts minorities, but when he does they seem to be pushed to the side, virtually mute, and often hired as the help. An example of this is the character Pelé in Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou (2004), a Brazilian who “sits in a crow’s-nest and sings David Bowie songs in Portuguese.” (Weiner, 2007)

Not only does Anderson use the same cast, but also the same crew. Robert Yeoman has served as the Director of Photography on every live-action Wes Anderson feature, starting with 1996’s Bottle Rocket. His work on Moonrise Kingdom (2013) even won him a citation from the British Society of Film Critics. (Seitz, 2016)

A lot of the same art department have also been hired again and again, with David Wasco and Adam Stockhausen being the two key production designers that Wes has used on almost all his feature films, with the exception of The Darjeeling Limited (2007) and Fantastic Mr. Fox. (2009) (IMDb, 2018)

ATMOSPHERE

Meticulously designed with colourful, dandyish flourishes, a Wes Anderson film is often described as child-like and ethereal. In The Grand Budapest Hotel (2014), there is a stark contrast between the toy-like visual stylisation and the realism of the emotionally grounded performances. These opposing forces, mixed with the themes of tension and Europe in the era of genocide, all seem to ingeniously blend together instead of clash. This is because of the soft, pale-to-warm light that cinematographer Robert Yeoman creates, which ties the whole film together visually, rather than just predominantly narratively. (Seitz, 2016)

[1] and [2] Stills from The Grand Budapest Hotel (2014)

There is little doubt that colour plays a huge role within Anderson’s work. He clearly has an eye for art direction, as his attention to detail of all aspects have helped him to create a fictional, yet realistic cinematic world where his characters exist – and the viewers feel they do too. Through using colour to create this picture-perfect atmosphere, the characters ultimately become their own visual language, allowing for an immersive visual experience even if there were to be no score or dialogue. For example, in The Grand Budapest Hotel, the muted pink makes the hotel itself feel like the main character in the film; additionally, the boy-scout green of the uniforms in Moonrise Kingdom (2013) help create an appropriately vintage feel; and even the mustard used in The Royal Tenenbaums (2001) is soon associated with the character of Margot Tenenbaum. [see picture] (Havlin, 2014)

[3] Still from The Royal Tenenbaums (2001)

The fictional worlds that have been brought to life in his films all have a certain dream-like quality, dependant on Anderson’s microscopic attention to detail; precisely colour drenched sets teamed with pastel painted skies and picture-perfect costumes, fit for even the most dysfunctional of characters. In terms of colour palette, his hazy-hued, full-colour scenes offer a view into his own world, with a vintage quality that casts the audience into a completely nostalgic trance. (Havlin, 2014) This romantic realism is from one of Anderson’s major influences, François Truffaut. Truffaut was a director, producer, screenwriter and even film critic who paved the way for the revolutionary French New Wave movement in the late 1950s. By founding this movement, it meant directors could now turn film into more of an art form rather than just a piece of literature, yet still maintaining a theoretical and artistic equilibrium. Anderson has not only been influenced by Truffaut narratively, for example showing young people struggling to find peace in the adult world, romanticism, and themes of revolution, but also visually. Truffaut brought to the cinema much warmer and profound films than had been seen before, hence it is clear how he paved a new sense of filmmaking ready for future generations of auteurs.(Insdorf, 1978)

AUTEUR DIRECTING

In 1954, over half a century ago, legendary film director François Truffaut proposed in the world famous French film magazine, Cahiers du Cinéma; the auteur theory. His theory explained that a filmmaker who is an auteur is the foremost author of the film, with their work being a place for personal ideas. Fundamentally, they are the artist and the film is their masterpiece. (Hillier, 1985)

Truffaut was soon faced with harsh criticism. People promptly expressed their negations of the auteur theory, explaining that it belittles the role of the crew involved within the production of a film and instead seems to only acknowledge the director. Despite the backlash the idea received, it became a recognised theory and went on to shape contemporary cinema as we know it today. (Edictive On Filmmaking, n.d.) This is because the auteur theory is perhaps the most honest reflection of the filmmaker.

When considering if a director counts as an auteur, there are three variables that must be accounted for. Firstly, they should own the look of the film. This means creating a signature revolving around the mise-en-scène, for example, cinematography, costume design and even seemingly insignificant features such as the title font. (Edictive On Filmmaking, n.d.) In Wes Anderson’s case, a key aspect of his signature, or formula so to say, is his consistent use of the Futura font, production, and costume design, and production. In terms of costume design, he chooses to never follow the fashion of any historical period, thus making his films feel almost timeless. (Seitz, 2009)

Another way a filmmaker can create a signature is through the musical score, as an auteur also owns the sound of the film. Anderson’s preference for the combination of old and new are obvious when listening to his film scores. His soundtracks frequently feature the music of Mark Mothersbaugh, whilst they also juxtapose classics with rising artists too. (The Conversation, 2014) Additionally, music is as much about creating the identity of a feeling as it is a person or place. This is explored in Grand Budapest Hotel’s original Oscar winning soundtrack, arranged by Alexandre Desplat, as it emphasises the dream-like quality, thus tying the whole film together.

Last and most importantly, it means owning the emotion of the film. Characters and themes should be the most important aspect of any auteur’s signature; therefore, these must be consistent throughout their entire collection of work. This means a film must not be studied as one individual piece, but instead, together along with the auteur’s complete history of work. (Edictive On Filmmaking, n.d.) Nonetheless, not every filmmaker can be considered an auteur, as a director must present a unique and instantly recognisable signature style that is irrefutably theirs.

As well as this, in terms of narrative, Anderson’s personal stories and memories are greatly reflected within his work. For instance, The Royal Tenenbaums (2001) has a number of references of his and also co-writer Owen Wilson’s childhood stories: Anderson’s parents divorcing and friends from school.

The film is riddled with references and similarities from many diverse influences,but one of his influences is legendary director Orson Welles. For Welles, being an auteur was about involving himself in virtually every aspect of film production; scriptwriting, producing, directing and even acting. When studying The Magnificent Ambersons (1942), Welles’ deep-focus images and Gothic sensibility feel somewhat parallel to ones in The Royal Tenenbaums. (Seitz, 2013) Not to mention the comically similar names, and that in both films the families live in very similar large manor homes with spires. (Lanthier, 2012)

In summary, to become an auteur, the filmmaker must regard themselves as an artist, and they must make the film their own. There are a number of ways to create a signature style, or formula, hence the following sections will be exploring some of Wes Anderson’s many auteur characteristics.

PLANIMETRIC STAGING AND COMPOSITION

Wes Anderson has one of the most distinctive styles of any American filmmaker. His composition is one of his key signatures because he always seems to know where exactly to place the camera, with which he repeatedly uses symmetrical and planimetric geometry.

One of the many forms of composition is symmetry, when used at the right moment, can maximise the potential of a shot. The implementation of symmetry may appear straightforward, but, in fact, cinematically it is much more complex. The impact of symmetry on a scene is so tremendous that directors sometimes avoid using these compositions. For example, if a filmmaker were to use symmetrical compositions too frequently or at the wrong points, it can make a scene feel overly formal, wooden and artificial. This subsequently eliminates any illusion the director intended the scene to have. (Raskin, 2003) Whereas, the filmmakers who have mastered symmetry and employ it in their work have a compelling visual style and are capable of conveying multifaceted meanings just through visual narrative alone. (Thonsgaard, 2003) Perhaps this hit-or-miss form of composition is the reason many directors tend to avoid it. But in saying this, symmetry is no doubt a useful visual marker to highlight important sections within the storyline, as it accentuates the moments that should be given the most attention.

While three-quarter forward-facing shots are common in Hollywood films, they are rare in Anderson’s. He instead uses planimetric shooting, which involves framing characters against a perpendicular background as if they were taking part in a police line-up. Usually characters face the camera, but can be rotated in multiples of 90-degrees to show their profile or have them turn their backs to the audience. Similarly to Anderson, Yasujiro Ozu, a Japanese director, would often arrange a group of his characters so they appeared in a perpendicular fashion, therefore making each plane parallel. Additionally, rather than using typical three-quarter shots in his dialogue scenes, the camera would look at the actors straight on, which makes the viewer feel as if they are another character in the middle of the conversation. (Seitz, 2016)

Anderson has been using planimetric staging in his work for a while, but it became particularly noticeable in Moonrise Kingdom (2013), where his characters seemed to be rigidly snapped to the x and y axis almost completely throughout. [see pictures]

[4]

[5]

[6]

[7]

Stills from Moonrise Kingdom (2013)

Anderson’s rigid planimetric staging limits his options. Characters seem to stare directly at the camera, and with three-quarter views being almost non-existent in Anderson’s work, when used, the characters can sometimes feel out of place. But when he does steer away from an all symmetrical shot, he does it sparingly, thus keeping its emotional impact. Such as in The Grand Budapest Hotel with Gustave interviewing Zero, when the scene ends with a turning point in their relationship, the camera pans from a three-quarter shot of Zero to Gustave smiling back at him. While this would go unnoticed in any other films, it seems to stand out here.

[8] Still from The Grand Budapest Hotel (2014)

[8] Still from The Grand Budapest Hotel (2014)

One of Japanese director Akira Kurosawa’s many gifts was his ability to stage his scenes in ways that were bold yet simplistic. He placed objects and characters in the scene in simple geometric shapes and even showed groups of people in recurring specific numbers. (Every Frame a Painting, 2015)

His approach to filmmaking was to shoot a scene in a way that the meaning of the shot was enhanced, and so that the composition itself could visually add to the narrative. He said,

“Before I decide how to photograph something I first of all think about how to improve whatever it is I’m photographing…And each technique I use necessarily differs according to whatever it is I’m taking a picture of”

(Richie, 1970, Pg. 188)

Alfred Hitchcock believed emotion should be the pivotal goal of all his films. He also believed a filmmaker should know where to position the camera with prior knowledge of what emotion they want the audience to feel at every point in the story. He had a theory which was:

“Emotion comes directly from the actor’s eyes. You can control the intensity of that emotion by placing the camera close or far away from those eyes. A close-up will fill the screen with emotion, and pulling away to a wide angle shot will dissipate that emotion.”

-Alfred Hitchcock (LaValley, 1972)

Hitchcock used this theory to plan out every scene and would use it knowing that it would draw the audience right inside the situation, rather than leaving them feeling distanced. He also believed that he would lose his power over the audience if he just simply recorded a scene with the camera in a constant single position. He was correct, since if the camera were to not move, the audience would watch a scene without becoming too involved, thus their attention would no longer be focussed on the specific visual details which connect with their emotional connotation. (LaValley, 1972, pg. 35)

Planimetric shots became more common in European and Asian films from the 1970s, and French New Wave directors, such as François Truffaut and Jean-Luc Godard, employed it in several films. Today they tend to show up only as one-off effects in mainstream films, with only a few directors making them building blocks of the whole piece. (Seitz, 2016)

In America, Anderson has become undoubtedly the most visible example of this technique, and while some others use planimetric staging as just another visual technique, it is the foundation of Anderson’s cinematic language. As mentioned before, this can sometimes give the audience a sense of detachment and stiffness. It is as if they are looking from a distance into an enclosed, synthetic world, but then, perhaps this is Anderson’s intention. This begs the question: has Anderson’s incessant use of symmetry and geometrically perfect planimetric frames made his films become monotonous?

DOUBLE FRAMING AND RATIO

The cinematic technique of a frame within a frame, whichever shape or positioning the director chooses to use, can emphasise and expand on the less obvious meanings within the narrative. Double framing can break up the information within the frame for maximum impact whilst also creating visual interest and depth within the overall composition. (Every Frame a Painting, 2015)

When trying to achieve the frame within a frame technique, it is important to understand the role of the Z-axis when organising the frame. The Z-axis is essentially the background, mid-ground, and foreground in every shot. An example of this is imagining the axis line as a hallway that moves away from the camera, like the unnerving corridor scenes in Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining (1980). To achieve this cinematic framing, many directors break the frame into smaller sections by using physical elements in the set such as mirrors, doors, and windows. Director Yasujiro Ozu even used shoji screens as a means to organise his composition. For example, double framing was spectacularly used in The Twilight Zone (1961) by using mirrors consistently throughout the episode. [see picture] Nevertheless, although uncommon in Anderson’s films, it is important to note that the frame within is not always limited to a rectangular shape. (Goodman, 2016)

[9] Still from The Twilight Zone – “The Mirror” (1961)

[10] Still from The Royal Tenenbaums (2001)

[11] Still from The Grand Budapest Hotel (2014)

[12] Still from The Darjeeling Limited (2007)

The Grand Budapest Hotel (2014) was revolutionary in Wes Anderson’s filmography in terms of framing and ratio. The multi-layered formatting started with Yeoman and Anderson’s strong desire to film in Academy ratio, also known as 1:37. This format is different to what they worked with previously, as it is less wide and very square.

“When this movie came up, we thought about the 1930s segment of it and we decided to shoot 1:37 for these parts. Gradually, that idea kind of expanded to using 1:85 and 2:40 to represent the other time periods.”

-Robert Yeoman (Seitz, 2016, pg. 231)

By separating the present day and also 1985 by using 1:85:1, or 16:9, to the year 1932 by using Academy Ratio, the film has clear distinct markers between the two time periods. It is one of the only films to change the format this much throughout. The particular formats used for their corresponding time periods can be seen as visual cues for the formats popularised at the time they are set in.

Anderson’s fondness for centering and symmetry in the wider formatted frames can be adapted to fit the square Academy ratio simply by cropping on the left and right, thus keeping his characters centre frame. But in scenes that feature wide or long shots, there are times where there is a lot of extra space at the top and bottom of the frame, areas which simply aren’t there in wider ratios, such as 1:85:1 being used for the present day. Fitting the 1930s narrative of The Grand Budapest Hotel into the 1:37:1 box gave Anderson a new problem in terms of maintaining his signature style. (Seitz, 2016)

One solution to this space in the top half of the frame is setting the camera height below eye level. Another, commonly used by Wes, is using the headroom as a comedic device, for example in the elevator shot [see picture] where Gustave and Madame D. have an awkward imbalance, shown in the space above them. This is in stark contrast to the perfectly balanced framing in scenes with Inspector Henckels and his men. [see picture] (Seitz, 2016)

[13] Still from The Grand Budapest Hotel (2014)

[14] Still from The Grand Budapest Hotel (2014)

The dressing of sets can also contribute to the effect of negative space within a shot. This can be shown when Agatha and Zero’s embrace are centre frame, but with lots of headroom the shot still conveys the sense of feeling confined, and this is from the stacks of muted pink pastry boxes in the upper background. [see picture] (Seitz, 2016)

[15] Still from The Grand Budapest Hotel (2014)

[15] Still from The Grand Budapest Hotel (2014)

In today’s generation, many filmmakers are “eclectic maximalists, not stringent minimalists.“ (Seitz, 2016) This meaning most want to do more with more, whereas Anderson on the other hand, takes the approach of doing more with less. He is a director who somewhat limits his options to the point of creatively testing himself. Similarly to Yasujiro Ozu, he refines his means, and by doing so, it opens new doors that perhaps “maximalist” directors would never stumble upon. A prime example of how he best uses his minimalist framing techniques is The Grand Budapest Hotel, and this is undoubtedly from refining his style through his earlier work. He created, yet resolved, a problem for himself that no longer exists for other filmmakers today. He used multi-formatting, including the less common Academy ratio, yet still managed to retain his signature style. This was a turning point in the way he used ratios and framing, and this resulted in the visually dominant film’s narrative being given a new importance.

GOD’S EYE VIEW

God’s eye view shots are an Anderson signature that can be dated back to Bottle Rocket (1996). He tilts the camera up, and subsequently tilts it down, and this always ends up with the God’s eye perspective; an overhead shot where the camera is generally parallel to the floor. an (Seitz, 2013)

Usually this technique is used as a way of distancing the audience from a scene, and a way of taking the narrative away from the character’s perspective, therefore the audience can see the bigger picture. Not only this, but this overhead view can also: highlight a character’s personality by showing props laid out, emphasise an emotion such as isolation, and even demonstrate themes of freedom and imprisonment. (Horton, 2016)

An auteur who revolutionised the way this camera angle is used is American director Martin Scorsese. Although he uses perpendicular angles and tight framing, he goes about it in a distinctive way. He uses it in the same way as Anderson; as a “brief time-out” from a scene, to let the audience thoroughly absorb the character, along with their personal objects and the surroundings that define them. (Seitz, 2009)

Although Scorsese used the God’s eye view in a refreshingly new way, he was certainly not the first filmmaker to employ it. Alfred Hitchcock utilised this technique in a beautifully dramatic way, and it is evident in his work that Scorsese’s devotion for it comes from closely studying Hitchcock. Nevertheless, when Scorsese uses this overhead shot, instead of using it as a means to distance the viewer from the situation, he uses it to give them a more personal point of view. Looking over the characters gives the audience the sense of feeling like “God” and lets them view the scene in a more neutral, level-headed way to re-establish their grasp on the narrative. (Horton, 2016)

However, Scorsese applied it to close-up shots placed within an otherwise conventionally edited dialogue scene – consequently diverting the audience’s attention to something they initially may not have been focussed on.

[16] Still from The Last Temptation of Christ (1998)

[17] Still from The Grand Budapest Hotel (2014)

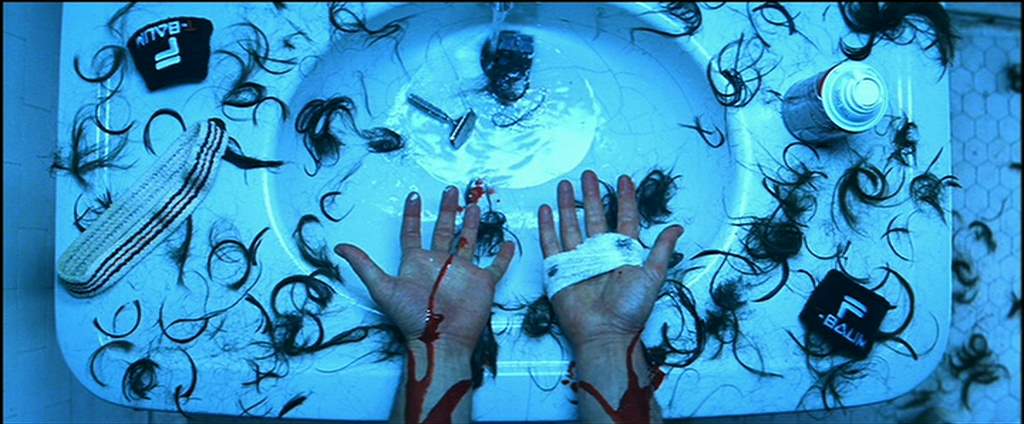

There are numerous similar examples throughout Scorsese’s filmography showing how Anderson’s use of the overhead insert is strikingly similar, from the composition and lighting, even to the duration of the shot. For example, the hand washing scene in The Aviator (2004) is similar to the attempted suicide scene in The Royal Tenenbaums (2001). [see pictures]

[18] Still from The Aviator (2004)

[19] Still from The Royal Tenenbaums (2001)

[19] Still from The Royal Tenenbaums (2001)

LATERAL TRACKING AND DOLL’S HOUSE SHOTS

Anderson has many shots in his films where the camera appears to be physically moving through walls, for example, looking straight on as if peering into a doll’s house, with the characters walking around inside. In some cases, the sets seem as if they were built for that specific tracking shot, but, in other cases, it feels as though you are moving through a doorway, passing through a wall, or even going up and down a level of the set. (Seitz, 2013, pg. 146)

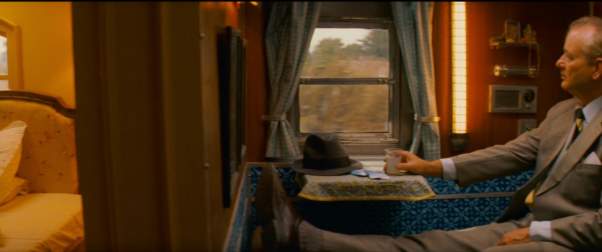

The beginnings of this signature shot were unintentionally founded during the filming of the aquarium scene in Rushmore (1998). With the first “purely figurative” version of this type of shot being the train carriage tracking sequence in The Darjeeling Limited (2007). [see picture] (Seitz, 2013)

[20] Still from The Darjeeling Limited (2007)

Anderson draws a lot of his inspiration from French New Wave filmmakers, including Jean-Luc Godard, who is a clear influence on his cutting techniques. But towering above the rest is François Truffaut, a devotee of Orson Welles, but with a warmer approach. Anderson pays tribute to Truffaut by quoting shots directly, but reversing their screen direction. The lateral tracking shot through the classroom in The 400 Blows (1959) is distinctly mirrored in the first scene of Rushmore, and from that same Truffaut film, the shot of Antoine in a chain-link cage, an image which is repeated in the penultimate shot of Bottle Rocket. (Seitz, 2009)

[22] Still from Bottle Rocket (2007)

[21] Still from The 400 Blows (1959)

A director who has influenced this doll’s house style is Orson Welles. Anderson evokes many “Wellsian” signatures, not only including the use of extreme wide-angle lenses (often placed at a low angle so that ceilings are visible in the shot), but also the fantastically complex extended tracking shots through geographically tricky locations.

Anderson refines this ‘doll’s house’ technique in a cleverly orchestrated scene in The Life Aquatic. One of the famous shots in Citizen Kane is the “rising-through-the-opera-house-manoeuvre”. This is echoed in Anderson’s The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou (2004) equally fantastic “let-me-tell-you-about-my-boat” sequence where the camera tracks laterally across Steve Zissou’s boat and lasts about the same length of time. (Seitz, 2013, pg. 126)

[23] Still from The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou (2004)

LATERAL WHIP PAN

There are certain techniques that Wes Anderson returns to again and again, and one of these is his heavy use of lateral whip pans. They are usually taken from eye level, panning 90 to 180-degrees horizontally or vertically, and uniquely merge both the first and third person. These quick, lateral pans seem to create the feeling that the camera is acting as another character in the scene – as though the viewer is sitting in between the characters, witnessing the scene first-hand, and can quickly change their perspective to view whichever subject they find most compelling.

This style originated in Bottle Rocket (1996), Anderson’s first full length film. It features his first use of a 90-degree horizontal whip pan, in a scene where they are on a bus, and the camera closely follows the action by darting between the three friends and the bus driver. (Seitz, 2013, pg. 58)

Anderson’s use of this distinctive camera movement is highly “Scorsese-esque”. For example, the whip pan that documents the arrival of Johnny Roast Beef at the post-heist party in Goodfellas (1990) is clearly resonated in the “hardest geometry equation in the world” scene which takes place at the start of Rushmore (1998), with Anderson’s camera darting to and from the chalkboards with a very similar feel to Scorsese’s. (Seitz, 2009)

But in Wes’ most recent work, a lot like director Edgar Wright, he uses whip-pans to create visual comedy. It can also used as a tool to reveal a character or prop that is of particular importance within the drive of the narrative. He first shows the character centrally facing the camera, then reveals what they see from their perspective. This technique is often used to create suspense, by showing a character’s reaction, then quickly panning to reveal what exactly they are looking at. (Seitz, 2013, pg. 240)

CUTTING AND SHOT LENGTH

In most of Anderson’s work, he opts for long, continuous shots that direct the audience’s attention through camera movement. While not constantly throughout his films, Wes, instead of cuts, uses the aforementioned lateral tracking and whip pans at the appropriate moments.

Alfred Hitchcock’s method of cutting and shooting a scene was to use it to its full emotional capability. In Rear Window (1954), his method of cutting was to speed it up as the film progresses – a way of imitating the narrative. At the start of the film life is normal, but as tensions rise, the tempo does so too.(LaValley, 1972 pg. 42) Akira Kurosawa, on the other hand, believed that if a scene is fast, then it should be shot fast with lots of tracking shots cut together, such as a chase scene. Whereas, a slow scene should be shot in a single take with no cuts whatsoever. (Richie, 1970)

“I guess I do always like the longer takes. For me, there’s suspense in it. I just find it thrilling.”

-Wes Anderson (Seitz, 2013)

Inspired by Hitchcock and Kurosawa, Anderson tends to use lots of long takes in his scenes. He often breaks these up through whip panning, but when he does use cutting, it is mostly used for his quick-cut montage sequences, where a character establishes a place or explains a situation. Anderson also draws a lot of his cutting inspiration from French New Wave filmmaker Jean-Luc Godard. Both directors use these types of jump cuts to quickly switch between scenes, thus showing a change in perspective in a short amount of time. (Miller, 2014)

Cutting is a director’s key way of tying the visuals with the storyline. Anderson can cleverly depict one scene as suspenseful, yet the next humorous. These rapidly changing and contrasting scenes show how when Wes uses cutting, although sparingly, he does it well.

SLOW MOTION

When looking at the visual momentum of a Wes Anderson film, it is important to note his use of slow motion. Slow motion became popularised in the 1960s as a way to elongate an action scene. But while Martin Scorsese used it primarily for this use, he also used it to exaggerate a character’s emotion. (Seitz, 2009)

There are numerous times in his filmography where Anderson has used slow motion to draw out this effect.Another great example of this is in The Royal Tenenbaums (2001) when Margot gets off the Green Line bus and the camera slows right down to 48 frames per second. As she steps off, she looks up and notices Richie, the man who has been constant in her life, waiting on a bench. Then the scene returns to dialogue, with frames now at 24 per second. (The Brojax, 2015)

This slowed down, yet fleeting moment in the scene allows the audience to have this ethereal view of Margot Tenenbaum and emphasises the realisation that although this is, simply, just a brief second in the character’s lives, it is a very important moment.

[24] Still from The Royal Tenenbaums (2001)

CONCLUSION: STYLE OVER SUBSTANCE?

“From Dignan in Bottle Rocket and Max Fischer in Rushmore to the extended family of fallen geniuses in The Royal Tenenbaums and burned-out explorer-filmmaker Steve Zissou in The Life Aquatic, the director’s filmography is filled with characters who learn the hard way that you can’t control life; you can only manage your own response to it.”

(Seitz, 2013, pg. 197)

There is an irony in this statement when you look at the films themselves, considering that Wes Anderson is in fact control of every line, composition, cut and pan. For when it comes to his work, there are no coincidences. If the camera quickly pans from one centrally framed character to another, or if a character’s clothing choice happens to perfectly coordinate with the colour of their bedroom walls, Wes has choreographed it.

To answer the posed question of whether Anderson’s consistent use of planimetric framing risks his style becoming monotonous: Yes, he risks the potential to become repetitive, but having imposed a constraint on himself, he is now compelled to show how he can vary these in both noticeable and elusive ways.

When Anderson creates his films, he is painting an aesthetically perfect picture by bringing all the visually sensual elements of his style together. He is compiling a jigsaw; putting the same pieces together, but pushing the boundaries by arranging them in a slightly different way, thus conveying a fresh story every time. However, it is all a matter of opinion, as even though Anderson creatively uses his techniques in this way, many still find his constant use of the same formula dull, stiff, and repetitive. But, there is no doubt that he has found an equilibrium between the substance and the visual style that accompanies it.

The most gripping part of Hitchcock’s films were not just the legendary stories he told, but the way he showed them. His visual techniques are his narrative. He used the camera to convey emotion, revealing what the character is thinking or feeling, thus creating his notorious suspense. (Once upon a screen…, 2012) But when watching Hitchcock’s films, were the audience so captured by his clever visuals that they failed to understand the story and the meaning of the film? They were not, simply because he used his mise-en-scène harmoniously and complementary with his storytelling, and Wes, too, does just that.

Millions of people are drawn to Anderson’s films because within the structured frames lies familiarity. This familiarity is his refined and successfully established formula, and this is what keeps his ever-growing audience coming back for more. Human beings are prone to find order where there may be none, yet, Wes Anderson delivers order every time, with his own uniquely styled menu.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

WES ANDERSON FILMOGRAPHY

Bottle Rocket. (1996). [DVD] W. Anderson.

Fantastic Mr. Fox. (2009). [DVD] W. Anderson.

Isle of Dogs (2018) [To be released] W. Anderson.

Moonrise Kingdom (2012) [DVD] W. Anderson.

Rushmore (1998) [DVD] W. Anderson.

The Darjeeling Limited. (2007). [DVD] W. Anderson.

The Grand Budapest Hotel. (2014). [DVD] W. Anderson.

The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou (2004). [DVD] W. Anderson.

The Royal Tenenbaums. (2001). [DVD] W. Anderson.

BOOKS

Allen, S. and Hubner, L. (2012). Framing film. Bristol, UK: Intellect.

Barr, C. (1969). The Films of Jean-Luc Godard. 2nd ed. London: Studio Vista.

Elam, K. (2011). Geometry of design. New York: Princeton Architectural Press.

Hillier, J. (1985). Cahiers du cinéma. 1st ed. London: Routledge.

Insdorf, A. (1978). François Truffaut. Boston: Twayne.

LaValley, A. (1972). Focus on Hitchcock. Englewood Cliffs (N.J.): Prentice-Hall.

McBride, J. (1972). Orson Welles. London: Secker & Warburg Ltd.

Petrie, G. (1970). The cinema of François Truffaut. 1st ed. London: Zwemmer.

Neumann, D. and Albrecht, D. (1996). Film architecture. Munich: Prestel.

Richie, D. (1970). The Films of Akira Kurosawa. 2nd ed. Berkeley, Calif.: University of California Press, pp.184-198.

Roud, R. (1970). Jean-Luc Godard. London: Thames & Hudson.

Seitz, M.Z (2013). The Wes Anderson collection. New York: Abrams.

Seitz, M.Z. (2016). The Grand Budapest hotel. New York: Abrams.

Sterritt, D. (2002). The films of Alfred Hitchcock. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Walker, A. (1972). Stanley Kubrick directs. London: Davis-Poynter, pp.54-64.

WEBSITES AND ONLINE JOURNALS

Akira Kurosawa info. (2017). The 10 Most Essential Akira Kurosawa Films. [online] Available at: http://akirakurosawa.info/2015/01/28/the-10-most-essential-akira-kurosawa-films/ [Accessed 10 Nov. 2017].

Antunes, J. (2015). From Kubrick to Anderson: One-Point Perspective by Jose Antunes – ProVideo Coalition. [online] ProVideo Coalition. Available at: https://www.provideocoalition.com/from-kubrick-to-anderson-one-point-perspective/ [Accessed 11 Nov. 2017].

Bordwell, D. (2014). THE GRAND BUDAPEST HOTEL: Wes Anderson takes the 4:3 challenge. [online] Observations on film art. Available at: http://www.davidbordwell.net/blog/2014/03/26/the-grand-budapest-hotel-wes-anderson-takes-the-43-challenge/ [Accessed 2 Jan. 2018].

Brody, R. (n.d.). Wes Anderson: The French Connection. [online] The New Yorker. Available at: https://www.newyorker.com/culture/richard-brody/wes-anderson-the-french-connection [Accessed 2 Jan. 2018].

Crow, J. (2014). The Perfect Symmetry of Wes Anderson’s Movies. [online] Open Culture. Available at: http://www.openculture.com/2014/03/the-perfect-symmetry-of-wes-andersons-movies.html [Accessed 4 Dec. 2017].

Economist.com. (2014). Style meets substance – The Q&A. [online] Available at: https://www.economist.com/blogs/prospero/2014/02/qa-wes-anderson [Accessed 4 Dec. 2017].

Edictive On Filmmaking. (n.d.). How to Become An Auteur Director. [online] Available at: http://edictive.com/blog/how-to-become-an-auteur-director/ [Accessed 8 Dec. 2017].

Every Frame a Painting (2015). The Bad Sleep Well (1960) – The Geometry of a Scene.

Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jGc-K7giqKM [Accessed 1 Dec. 2017].

Goodman, D. (2016). How to Craft a Cinematic Frame Within a Frame. [online] The Beat: A Blog by PremiumBeat. Available at: https://www.premiumbeat.com/blog/how-to-craft-a-cinematic-frame-within-a-frame/ [Accessed 11 Nov. 2017].

Havlin, L. (2014). Wes Anderson’s Colour Palettes. [online] AnOther. Available at: http://www.anothermag.com/art-photography/3586/wes-andersons-colour-palettes [Accessed 2 Jan. 2018].

Holland, N. (n.d.). Norman Holland on Yasujiro Ozu’S Tokyo Story, Tôkyô monogatari. [online] Asharperfocus.com. Available at: http://www.asharperfocus.com/TokyoStory.html [Accessed 11 Nov. 2017].

Horton, H. (2016). Martin Scorsese and the God’s Eye View as a Moral Reminder. [online] Film School Rejects. Available at: https://filmschoolrejects.com/martin-scorsese-and-the-gods-eye-view-as-a-moral-reminder-af4e4d29556e [Accessed 2 Jan. 2018].

IMDb (2018). Wes Anderson. [online] IMDb. Available at: http://www.imdb.com/name/nm0027572/ [Accessed 2 Jan. 2018].

Keynejad, R. (2015). Wes Anderson’s The Grand Budapest Hotel – psychiatry in the movies. The British Journal of Psychiatry, [online] 206(2), pp.159-159. Available at: http://bjp.rcpsych.org/content/206/2/159 [Accessed 5 Nov. 2017].

Lanthier, J. (2012). The Royal Tenenbaums and The Magnificent Ambersons: Wes, Welles and Literary Cinema – The L Magazine. [online] The L Magazine. Available at: http://www.thelmagazine.com/2012/05/the-royal-tenenbaums-and-the-magnificent-ambersons-wes-welles-and-literary-cinema/ [Accessed 4 Dec. 2017].

Lee, S. (2016). Wes Anderson’s ambivalent film style: the relation betweenmise-en-scèneand emotion. New Review of Film and Television Studies, 14(4), pp.409-439.

Lyttelton, O. (2017). 5 Essential Films By Yasujirō Ozu. [online] IndieWire. Available at: http://www.indiewire.com/2016/03/5-essential-films-by-yasujiro-ozu-263749/ [Accessed 10 Nov. 2017].

Metropolis. (2017). Hitchcock and the Architecture of Suspense – Metropolis. [online] Available at: http://www.metropolismag.com/ideas/arts-culture/hitchcock-and-the-architecture-of-suspense/ [Accessed 11 Nov. 2017].

Miller, M. (2014). Wes Anderson: His Impact on Cinema and Cinema’s Impact on Him (with image) · maxabillion. [online] Storify. Available at: https://storify.com/maxabillion/wes-anderson [Accessed 2 Jan. 2018].

No Film School. (2016). Video: Comparing the Visual Styles of Stanley Kubrick & Wes Anderson [online] Available at: http://nofilmschool.com/2016/06/comparing-visual-styles-stanley-kubrick-wes-anderson [Accessed 1 Nov. 2017].

No Film School. (2017). Video: Surprising Connections Between the Films of Yasujiro Ozu and Wes Anderson. [online] Available at: http://nofilmschool.com/2015/07/video-surprising-connections-between-films-yasujiro-ozu-and-wes-anderson [Accessed 1 Nov. 2017].

Nordine, M. (2017). How Alfred Hitchcock, ‘Lawrence of Arabia’ and More Influenced Wes Anderson — Watch. [online] IndieWire. Available at: http://www.indiewire.com/2017/02/alfred-hitchcock-lawrence-of-arabia-and-more-influenced-wes-anderson-1201785291/ [Accessed 10 Nov. 2017].

Once upon a screen… (2012). The Hitchcock Signature. [online] Available at: https://aurorasginjoint.com/2012/05/13/the-hitchcock-signature/ [Accessed 2 Feb. 2018].

Raskin, R., 2003. A Danish Journal of Film Studies. [online] Available at: http://pov.imv.au.dk/pdf/pov15.pdf [Accessed 4 Dec. 2017]

Rose, S. (2014). Wes Anderson: the architectural film-maker. The Architects’ Journal; London, [online] (00038466). Available at: https://search.proquest.com/docview/1507611332?accountid=14693 [Accessed 11 Nov. 2017].

Seelie, C. (2014). 10 Films That Had The Biggest Influences On The Films of Wes Anderson. [online] Taste of Cinema – Movie Reviews and Classic Movie Lists. Available at: http://www.tasteofcinema.com/2014/10-films-that-had-the-biggest-influences-on-the-films-of-wes-anderson/ [Accessed 2 Feb. 2018].

Seitz, M. (2009). The Substance of Style, Pt 1 by Matt Zoller Seitz – Moving Image Source. [online] Movingimagesource.us. Available at: http://www.movingimagesource.us/articles/the-substance-of-style-pt-1-20090330 [Accessed 4 Dec. 2017].

Seitz, M. (2009). The Substance of Style, Pt 2 by – Moving Image Source. [online] Movingimagesource.us. Available at: http://www.movingimagesource.us/articles/the-substance-of-style-pt-2-20090403 [Accessed 4 Dec. 2017].

The Conversation. (2014). Wes Anderson is one of cinema’s great auteurs: discuss. [online] Available at: https://theconversation.com/wes-anderson-is-one-of-cinemas-great-auteurs-discuss-25198 [Accessed 4 Dec. 2017].

The Brojax. (2015). By Way of the Green Line Bus — Wes Anderson’s The Royal Tenenbaums. [online] Available at: http://www.thebrojax.com/new-blog/2015/2/27/by-way-of-the-green-line-bus-wes-andersons-the-royal-tenenbaums [Accessed 2 Feb. 2018].

The Daily Beast. (2014). The Cast of ‘The Grand Budapest Hotel’ Says Wes Anderson Is a Genius Hardass. [online] Available at: https://www.thedailybeast.com/the-cast-of-the-grand-budapest-hotel-says-wes-anderson-is-a-genius-hardass [Accessed 4 Dec. 2017].

Thonsgaard, L. (2003). Symmetry…. [online] Pov.imv.au.dk. Available at: http://pov.imv.au.dk/Issue_15/section_5/artc1A.html [Accessed 2 Jan. 2018].

Vimeo (2017). Wes Anderson // Centered. [online] Available at: https://vimeo.com/89302848 [Accessed 2 Nov. 2017].

Vimeo (2012). Ozu//Passageways. [online] Available at: https://vimeo.com/55956937 89302848 [Accessed 2 Nov. 2017].

Weiner, J. (2007). How Wes Anderson mishandles race.. [online] Slate Magazine. Available at: http://www.slate.com/articles/arts/culturebox/2007/09/unbearable_whiteness.html [Accessed 2 Jan. 2018].

YouTube. (2017). How to Direct Like Wes Anderson – Style and Trope Breakdown. [online] Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JDeo49wtvdU [Accessed 11 Nov. 2017].

YouTube. (2017). Monitor – Alfred Hitchcock (1964). [online] Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=c9PO-767D8I [Accessed 10 Nov. 2017]

YouTube. (2017). The Cinematography of Robert Yeoman (Wes Anderson’s DoP). [online] Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=D6L_txEdKDg [Accessed 9 Nov. 2017]

PHOTOGRAPH REFERENCES

1. Still of The Grand Budapest Hotel. [image] Available at: https://film-grab.com/2014/07/10/the-grand-budapest-hotel/37-524/#main [Accessed 10 Feb. 2018].

2. Still of The Grand Budapest Hotel. [image] Available at: https://film-grab.com/2014/07/10/the-grand-budapest-hotel/ [Accessed 10 Feb. 2018].

3. Still of The Royal Tenenbaums. [image] Available at: https://nofilmschool.com/2017/12/watch-3-ages-wes-anderson-characters [Accessed 10 Feb. 2018]

4. & 5. Stills of Moonrise Kingdom. [image] Available at: http://www.vulture.com/2014/03/wes-anderson-characters-cant-move-diagonally.html [Accessed 10 Feb. 2018].

6. Still of Moonrise Kingdom. [image] Available at: https://nerdist.com/blu-ray-review-criterions-moonrise-kingdom-is-the-most-wes-anderson-y-yet/ [Accessed 10 Feb. 2018].

7. Still of Moonrise Kingdom. [image] Available at: http://www.vulture.com/2014/03/wes-anderson-characters-cant-move-diagonally.html [Accessed 10 Feb. 2018].

8. Still of The Grand Budapest Hotel. [image] Available at: https://ccpopculture.com/2014/04/09/the-grand-budapest-hotel-2014/ [Accessed 10 Feb. 2018].

9. Still of The Twilight Zone [image] Available at: https://www.premiumbeat.com/blog/how-to-craft-a-cinematic-frame-within-a-frame/ [Accessed 10 Feb. 2018]

10. Still of The Royal Tenenbaums. [image] Available at: https://film-grab.com/2011/03/24/the-royal-tenenbaums/#jp-carousel-9045 [Accessed 10 Feb. 2018]

11. Still of The Grand Budapest Hotel. [image] Available at: https://bestmovieshots.files.wordpress.com/2016/02/27.png [Accessed 10 Feb. 2018].

12. Still of The Darjeeling Limited. [image] Available at: https://film-grab.com/2010/07/19/the-darjeeling-limited/#jp-carousel-2578 [Accessed 10 Feb. 2018].

13. & 14. Stills of The Grand Budapest Hotel. [image] Available at: https://hk.asiatatler.com/life/fendi-and-the-grand-budapest-hotel [Accessed 10 Feb. 2018].

15. Still of The Grand Budapest Hotel. [image] Available at: http://variety.com/2014/film/news/five-keys-to-wes-andersons-hotel-success-story-1201154272/ [Accessed 10 Feb. 2018].

16. Still of The Last Temptation of Christ. [image] Available at: http://moviemezzanine.com/the-second-criterion-the-last-temptation-of-christ/ [Accessed 10 Feb. 2018].

17. Still of The Grand Budapest Hotel. [image] Available at: https://film-grab.com/2014/07/10/the-grand-budapest-hotel/19-523/#main [Accessed 10 Feb. 2018].

18. Still of The Aviator. [image] Available at: https://vimeo.com/193740044 [screen grab image] [Accessed 10 Feb. 2018].

19. Still of The Royal Tenenbaums. [image] Available at: https://film-grab.com/2011/03/24/the-royal-tenenbaums/#jp-carousel-9086 [Accessed 10 Feb. 2018].

20. Still of The Darjeeling Limited. [image] Available at: https://cinea.be/too-pretty-to-eat-the-grand-budapest-hotel/ [Accessed 10 Feb. 2018].

21. Still of The 400 Blows. [image] Available at: https://twitter.com/filmicallusion/status/758803130570055680 [Accessed 10 Feb. 2018]

22- Still of Bottle Rocket. [image] Available at: http://www.criterionconfessions.com/2009/04/bottle-rocket-450.html [Accessed 10 Feb. 2018].

23- Still of The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou. [image] Available at: http://www.fthismovie.net/2017/11/a-movie-im-thankful-for-life-aquatic.html [Accessed 10 Feb. 2018].

24- Still of The Royal Tenenbaums. [screen grab image] Available at: https://vimeo.com/83728153 [Accessed 10 Feb. 2018].

DISTILLATION

Wes Anderson has established himself as one of American cinema’s most distinctive filmmakers of this generation. Remarkably knowledgeable in his film history and technique, Anderson is a classic example of an auteur filmmaker.

He, arguably, has one of the most distinct looks in cinema with his infamous symmetrical style, frequent use of the overhead shot, saturated colour palettes, Futura Bold title cards, family issues, and a recurring ensemble cast. Symmetry is sometimes felt to be overly theatrical, but if you have watched anything by Anderson, you will know that seeming artificial and contrived has never been one of his concerns.

But does his stylistic mise-en-scène impact the storytelling? Is the audience so captured by all his clever visuals that they fail to understand the story and the meaning of the film? This essay examines some of Wes Anderson’s many cinematic influences and his attempt to combine them to create his uniquely personal visual style. It explores whether his repetitive and memorable style is as, or more, important than the substance and narrative of his films.

Cite This Work

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing stye below:

Related Services

View allRelated Content

All TagsContent relating to: "Film Studies"

Film Studies is a field of study that consists of analysing and discussing film, as well as exploring the world of film production. Film Studies allows you to develop a greater understanding of film production and how film relates to culture and history.

Related Articles

DMCA / Removal Request

If you are the original writer of this dissertation and no longer wish to have your work published on the UKDiss.com website then please: