Audio-Aero Tactile Integration in Speech Perception: Literature Review

Info: 6714 words (27 pages) Example Literature Review

Published: 23rd Nov 2021

Tagged: Physiology

This example is part of a set:

- Introduction

- Literature Review

- Methodology

Chapter II - Review of Literature

2.1 Speech Production

Production of speech is underpinned by a series of complex interaction of numerous individual processes beginning at brain with phonetic and motoric planning, followed by expelling of air from lungs that leads to vibration of vocal cords, termed as phonation. Puffs air released after phonation is then routed to oral or nasal cavities, which gives the resonance quality needed. Before expelling off, as speech sounds, these air puffs undergo further shaping by various oral structures called articulators. These physical mechanisms by articulators are being studied as articulatory phonetics by experts in the field of linguistics and phonetics. The basic unit of speech sound is called phoneme which consists of vowels and consonants. Perceptual studies and spectrographic analysis revealed that speech sounds could be specified in terms of some simple and independent dimensions and that they were not grouped along single complex dimension (Liberman,1957). Linguists and phoneticians have thereby classified phonemes according to features of the articulation process used to generate the sounds. These features of speech production are reflected in certain acoustic characteristics which are presumably discriminated by the listener.

The articulatory features that describes a consonant are its place and manner of articulation, whether it is voiced or voiceless, and whether it is nasal or oral. For example, [b] is made at the lips by stopping the airstream, is voiced, and is oral. These features are represented as:

| Consonants | [p] | [b] | [k] | [g] |

| Voicing | Voiceless | Voiced | Voiceless | Voiced |

| Place | Labial | Labial | Velar | Velar |

| Manner | Stop | Stop | Stop | Stop |

| Nasality | Oral | Oral | Oral | Oral |

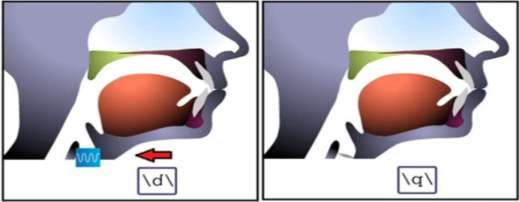

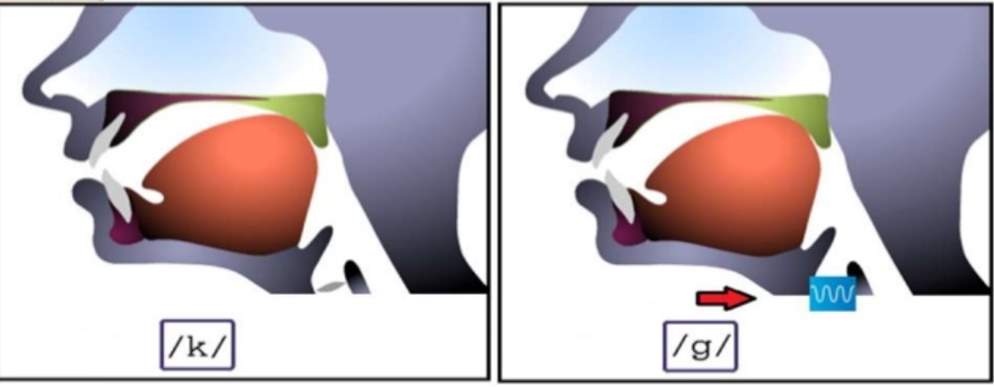

Figure illustrates the place and manner of articulation of labials and velars stops

Much of the featural study in speech has focused on the stop consonants of English. The stop consonants are a set of speech sounds that share the same manner of articulation. Their production begins with a build-up of pressure behind some point in the vocal tract, following which is a sudden release of that pressure. Two articulatory features in the description of stop consonant production are place of articulation and voicing. They have well defined acoustic properties with minimal difference in production(Delatte,1951). Place of articulation refers to the point of constriction in the vocal tract, especially in oral cavity, where closure occurs. Formant transitions are the acoustic cues that underlie the place of articulation in CV syllables (Liberman et al.,1967). On the other hand, presence or absence of periodic vocal cord vibration is the voicing feature. The acoustic cue that underlie the voicing feature is voice onset time (Lisker & Abramson, 1964) and it corresponds to the time interval between release from stop closure and the onset of laryngeal pulsing. In English, six stops of three cognate pairs share place of articulation but differ in voicing feature. These consonants are /p/ and /b/ are labial, /t/ and /d/ are alveolar, and /k/ and /g/ are velar where the first of each pair is voiceless and the second is voiced.

Initially, processing of place and voicing features were thought to be independent of each other in stops. Miller and Nicely (1955) investigated perceptual confusion in 16 syllables presented to listeners in various signal-to- noise ratios. Information from several features including place and voicing, were calculated individually and in combination and the values of the two were found to be approximately equal, leading them to a conclusion that these features are mutually independent. So, this study suggests that features are extracted separately during preliminary perceptual processing and recombined later in response.

In contrast, non-independence of articulatory features especially, place and voicing, has also been evidenced by researchers in literature.

Lisker and Abramson (1970) found evidence for change in voicing as a function of place of articulation. Voice onset time(VOT) is the aspect of voicing feature that depends on place of articulation. It has been found that the typical voice onset time lag at the boundary between voiced and voiceless stop consonants produced under natural conditions is longer as the place of articulation moves further back in the vocal tract (i.e. from /ba/ to /da/ to /ga/).

Pisoni and Sawusch (1974) reached a similar conclusion regarding the dependency of place and voicing feature. They constructed two models of interaction of phonetic features in speech perception to predict syllable identification for a bi-dimensional series of synthetic CV stop consonants (/pa/,/ba/,/ta/,/da/) by systematically varying acoustic cues underling place and voicing features of articulation inorder to examine the nature of the featural integration process. Based on their comparison and evaluation of the two models, they concluded that acoustic cues underlying phonetic features are not combined independently to form phonetic segments.

Eimas and colleagues (1978) also reported a mutual, but unequal, dependency of place and manner information for speech perception using syllables (/ba/, /da/, /va/, /za/), in which they concluded that place is more dependent on manner than manner is on place.

In addition, Miller`s (1977) comparative study on mutual dependency of phonetic features using the labial‐alveolar and the nasal‐stop distinctions(/ba/,/da/,/ma/,/na/) also provided strong support for the claim that the place and manner features undergo similar forms of processing even though they are stated by different acoustic parameters.

In summary, there is considerable evidence for dependency effects, in the analysis of phonetic features from several experimental paradigms establishing the fact that combination of phonetic features can aid in better perception of speech sounds.

In face-to-face communication between normally hearing people, manner of articulation of consonantal utterances is detected by ear (e.g., whether the utterance is voiced or voiceless, oral or nasal, stopped or continuant, etc.); place of articulation, on the other hand, is detected by eye.

Binnie et al. (1974) found that the lip movements for syllables /da/, /ga/, /ta/, or /ka/ were visually difficult to discriminate from each other; similarly, lip movements for /ba/, /pa/, /mal/ were frequently confused with each other. Conversely, labial and nonlabial consonants were never confused. They also stated that the place of articulation is more efficiently detected by vision than manner of articulation. At the same time, they established Miller and Nicely’s (1955) finding that voicing and nasality feature of consonants are readily perceived auditorily, even in low signal noise ratios. Furthermore, they explained that auditory-visual confusions stated, indicate that the visual channel in bi-sensory presentations reduced errors in phoneme identification, when varied by place of articulation.

Hence, it can be concluded that speech perception ideally is a multisensory process involving simultaneous syncing of visual, and acoustic cues generated during phonetic production . Therefore, investigation of speech perceptual performance in humans require use of conflicting information. This can be achieved by using congruent and incongruent stimulus conditions.

2.1.1 Congruent and incongruent condition

During an identification task of a stimuli, multisensory representation of stimuli induces a more effective representation than unisensory. The effect would be remarkably more pronounced for congruent stimuli. Stimulus congruency is defined in terms of the properties of the stimulus. In stimulus congruence, there is a dimension or feature of stimulus in a single modality or in different modalities, that are common to them.

Stroop effect (Stroop, 1935) is a classic example to understand stimulus congruency. In the Stroop task, participants respond to the ink colour of coloured words. Typically, participants performed in terms of reaction times and accuracy if the word’s meaning is congruent with its colour (e.g., the word “BLUE” in blue ink) than if colour and meaning are incongruent (e.g., the word “BLUE” in green ink). Similarly, when perceiving speech if the stimuli is congruent i.e. stimuli from one modality (e.g. visual) is in sync with another modality (e.g. auditory), then perception of speech is found to be substantially better. Sumby and Pollack (1954) evidenced that in a noisy background, watching congruent articulatory gestures improves the perception of degraded acoustic speech stimuli. Similar findings were also found in auditory – tactile stimulus congruency conditions as well which will be discussed later.

Now that we discussed how various speech sounds are produced, articulatory features that define speech sounds and reviewed studies suggesting that these features are encoded in brain in an integrated fashion making speech perception a unified phenomenon. Also, we extended our understanding of the terms – congruent and incongruent stimuli which will be frequently used in next session with supporting evidence from literature. In the subsequent section, we will continue to review speech perception as a multisensory event with evidences from behavioural studies.

2.2 Bimodal Speech perception

Speech perception is the process by which the sounds of language are heard, interpreted and understood. Research in speech perception seeks to understand how human listeners recognize speech sounds and use this information to understand spoken language. Just like speech production process, the perception of speech also is a very complicated, multi faced process that is not yet fully understood.

As discussed in previous sections, speech can be perceived by the functional collaboration of the sensory modalities. In ideal conditions, hearing a speaker`s words is sufficient to identify auditory information. Auditory perception may be understood as processing of those attributes that allow an organism to deal with the source that produced the sound than simply processing attributes of sound like pitch, loudness etc. So, recently researchers have viewed speech perception as a specialized aspect of general human ability, the ability to seek and recognize patterns. These patterns can be acoustic, visual, tactile or a combination of these. Speech perception, as a unified phenomenon involving association of various multisensory modalities (e.g. auditory- visual, auditory – tactile, visual -tactile) will be discussed in detail now reviewing significant behavioural studies of multisensory literature.

2.2.1 Auditory – visual (AV) integration in speech perception

The pioneering work on multisensory integration showed that while audition remains vital in perceiving speech, our understanding of auditory speech is supported by visual cues in everyday life, that is, seeing the articulating mouth movements of the speaker. This is especially true when signal is degraded or distorted (e.g., due hearing loss, environmental noise or reverberation). Literature suggests that individuals with moderate to severe hearing impairment can achieve high levels of oral communication skills.

Thornton and Erber (1979) evaluated 55 hearing impaired children aged between 9-15 years using sentence identification task. Their written responses were scored and was found that their speech comprehension and language acquisition is quite high and quick with auditory – visual perception.

Grant et.al. (1998) also arrived at a similar conclusion when they studied auditory- visual speech recognition in 29 hearing impaired adults through consonant and sentence recognition task. Responses were made by choosing the stimuli heard from a screen and it was obtained for auditory, visual and auditory – visual conditions. Result is suggestive of AV benefit in speech recognition for hearing impaired.

Influence of visual cues on auditory perception was studied by Sumby and Pollack (1954) in adults using bi-syllabic words presented in noisy background. And the results demonstrate that visual contribution in speech recognition is significantly evident at low signal to noise ratios. Moreover, findings from Macleod & Summerfield`s (1990) investigation of speech perception in noise using sentences also confirms that speech is better understood in noise with visual cues.

On the other hand, even with fully intact speech signals, visual cues can have an impact on speech recognition. Based on a general observation for a film, McGurk and MacDonald (1976) designed a AV study that lead to a remarkable break through in speech perception studies. They presented incongruent AV combinations of 4 monosyllables (/pa/, /ba/, /ga/, /ka/) to school children and adults in auditory only and AV conditions. Subjects responses were elicited by asking them to repeat the utterances they heard. Findings from the study demonstrated that when the auditory production of a syllable is synchronized with visual production of an incongruent syllable, most subjects will perceive a third syllable that is not represented by either auditory or visual modality. For instance, when the visual stimulus /ga/ is presented with the auditory stimulus /ba/, many subjects report perceiving /da/. While reverse combinations of such incongruent monosyllabic stimuli usually elicit response combinations like /baga/ or /gaba/ (McGurk & MacDonald, 1976; Hardison, 1996; Massaro, 1987). This unified integrated illusionary percept, formed as a result of either fusion or combination of stimulus information, is termed as “McGurk effect”. This phenomenon stands out to be the basis of speech perception literature substantiating multisensory integration.

Conversely, studies suggests that McGurk effect cannot be easily induced in other languages (e.g. Japanese) as in English. Sekiyama and Tohkura (1991) evidenced this in their investigation to evaluate how Japanese perceivers respond to McGurk effect. 10 Japanese monosyllables were presented in AV and audio only condition in noisy and noise- free environment. Perceivers had to write down the syllable they perceived. When AV and auditory only condition was compared, results suggested that McGurk effect depended on auditory intelligibility and McGurk effect was induced when auditory intelligibility was lower than 100%, else it was absent or weak.

Early existence of audio-visual correspondence ability has established when literature evidenced AV integration in pre-linguistic children (Kuhl & Meltzoff,1982; Burnham &Dodd, 2004; Pons etal.,2009) and in non-human primates (Ghazanfar and Logothetis,2003).

Kuhl and Meltzoff (1982) investigated AV integration of vowels (/a/ and /i/) in 18 to 20 weeks old normal infants by scoring their visual fixation. Results showed significant effect of auditory- visual correspondence and vocal imitation by some infants, which is suggestive of multimodal representation of speech. Similarly, McGurk effect was replicated in pre-linguistic infants aged four months employing visual fixation paradigm by Burnham and Dodd (2004). Infant studies indicate that new-borns also possess sophisticated innate speech perception abilities demonstrated by their multisensory syncing capacity which lay the foundations for subsequent language learning.

In addition, it is quite interesting to know that other non-human primates also exhibit a similar AV synchronisation, as humans ,in their vocal communication system. Rhesus monkeys were assessed to see if they could recognize auditory–visual correspondence between their ‘coo’ and ‘threat’ calls by Ghazanfar and Logothetis (2003) using preferential-looking technique to elicit responses generated during the AV task. Their findings are suggestive of an inherent ability in rhesus monkeys to match their species-typical vocalizations presented acoustically with the appropriate facial articulation posture. The presence of multimodal perception in an animal’s communication signals may represent an evolutionary precursor of humans’ ability to make the multimodal associations necessary for speech perception.

Complementarity of visual signal to acoustic signal and how it is an advantage to speech perception has been reviewed so far. Moreover, we also considered the fact that AV association is an early existing ability as evidenced by animal and infant studies. Recently research progressed a step ahead beyond AV perception and extended findings by examining how tactile modality can influence auditory perception which is discussed in the following section.

2.2.2 Auditory – tactile (AT) integration in speech perception

Less intuitive than the auditory and visual modalities, the tactile modality also has an influence on speech perception. Remarkably, the literature suggests that speech can be perceived not only by eyes and ears but also by hand (feeling). Previous research on the effect of tactile information on speech perception has focused primarily on enhancing the communication abilities of deaf-blind individuals (Chomsky, 1986; Reed et al., 1985). But robust evidence for manual tactile speech perception mainly derives from researches on the Tadoma method (Alcorn, 1932; Reed, Rubin, Braida, & Durlach, 1978). The Tadoma method, is a technique where oro-facial speech gestures are felt and monitored from manual-tactile/hand contact/haptic with the speaker’s face.

Numerous behavioural studies have also shown the influence of tactile cues on speech recognition in healthy individuals. Treille and colleagues (2014) showed that speech perception is altered regarding the reaction time when haptic (manual) information is provided additionally to the audio signal in untrained healthy adult participants. Fowler and Dekle (1991), on the other hand, described a subject who perceived /va/ responses when feeling tactile (mouthed) /ba/, presented simultaneously with acoustic /ga/. So, when the manual-tactile contact with a speaker’s face coupled with incongruous auditory input, integration of both audio and tactile information evoked a fused perception of /va/, thereby representing an audio-tactile McGurk effect.

But not only manual-tactile contact has been shown to influence speech perception. Abundant work conducted by Derrick and colleagues (2009) demonstrated puffs of air on skin when combined with auditory signal can enhance speech perception. In a recent study conducted by Gick and Derrick (2009), untrained and uninformed healthy adult perceivers received puffs of air (aero-tactile stimuli) on their neck or hand while simultaneously hearing aspirated or unaspirated English plosives (i.e., /pa/ or /ba/). Participant responses for the mono- syllable identification task was recorded by pressing keys corresponding to the syllable they heard. Participants reported that they perceived more /pa/ in the aero-tactile condition indicating that listeners integrate this tactile and auditory speech information in much the same way as they do synchronous visual and auditory information. A similar effect was replicated using puffs of air at the ankle (Derrick & Gick, 2013) demonstrating the effect does not depend on spacial ecological validity.

In addition, in the supplementary methods of their original article (Aero-tactile integration in speech perception), Derrick and Gick (2009b) demonstrated validity of tactile integration in speech perception by replicating their original experiment on hand with 22 participants ,but by replacing puffs of air with taps presented from a metallic solenoid plunger. No significant effect was observed on speech perception by tap stimulation. Thereby confirming that participants were not merely responding to generalized tactile information nor it was the result of increased attention. And this indicates that listeners are shown to respond to aero-tactile cues normally produced during speech, which evidences multisensory ecological validity.

Moreover, to illustrate how airflow would help in distinguishing minor differences in speech sounds, Derrick et al. (2014b) designed a battery of eight experiments consisting of comparisons with different combinations of voiced and voiceless (stops, fricatives and affricatives) English monosyllables (/pa/, /ba/, /ta/, /da/, /fa/, /ʃa/, /va/, /t͡ʃa/, /d͡ʒa/). Study was run on 24 healthy participants where auditory stimuli was presented simultaneously with air puff on their head. Participants were asked to choose which of the two syllables they heard for all the experiments. Stops and fricatives perception was found to be enhanced on analysis of data. Results obtained advocates that aero-tactile information can be extracted from the audio signal and used to enhance speech perception of a large class of speech sounds found in many languages of the world.

Extending Gick and Derrick’s (2009) findings on air puffs, Goldenberg and colleagues (2015) investigated the effect of air puffs during identification of syllables on a voicing continuum rather than using voiced and voiceless exemplars as in the original work (Gick & Derrick, 2009). English consonants (/pa/,/ba/,/ka/ and /ga/) were the syllables used for the study. Auditory signal was presented simultaneously with and without air puff received on the participant`s hand. 18 normal adults who took part in the study, were made to press key corresponding to their response from a choice of two syllables. Their findings showed an increase in voiceless responses when co-occurring puffs of air were presented on the skin. In addition, this effect became less pronounced at the endpoints of the continuum. This suggests that the tactile stimuli exert greater influence in cases where auditory voicing cues are ambiguous, and that the perception system weighs auditory and aero-tactile inputs differently.

Temporal asynchrony to establish the temporal ecological validity of auditory-tactile integration during speech perception was evaluated by Gick and colleagues (2010). They assessed whether asynchronous cross-modal information became integrated across modalities in a similar way as in audio-visual perception by presenting auditory (aspirated “pa” and unaspirated “ba” stops) and tactile (slight, inaudible, cutaneous air puffs) signals synchronously and asynchronously. Experiment was conducted in 13 healthy participants who made choice of the speech sound they heard using a button box.Conclusions from the study states that subjects integrate audio- tactile speech over a wide range of asynchronies, like in cases of audio- visual speech events. Furthermore, the temporal difference between speed of sound and air flow is varied as our perceptual system incorporates different physical transmission speeds for different multimodal signals, leading to an asymmetry in multisensory enhancement in this study.

Aero- tactile integration was found to be effective for perception of syllables, as evidenced in studies above, so researchers extended their evaluation to see if a similar effect could be elicited for complex stimulus types like words, and sentences.

Derrick et al. (2016) studied the effect of speech air flow on syllable and word identification with onset fricatives and affricates in two languages- Mandarin and English where all the 24 participants had to choose response from an alternative of two expected responses when auditory stimulus was presented with and without air puff conditions. And the results show air flow is in helping distinguish syllables. The greater the distinction between the two choices, the more useful air flow is in helping to distinguish syllables. Though this effect was noticed to be stronger in English than in Mandarin, it was significantly present in both languages.

Recently, benefit of AT integration in continuous speech perception was examined with highly complex stimulus and with increased task complexity by Derrick and colleagues (2016). The study was conducted on hearing typical and hearing impaired adult perceivers who received air puffs on their temple while simultaneously hearing five-word English sentences (e.g. Amy bought eight big bikes). Data as recorded for puff and no puff conditions and the participants were asked to say aloud the words after perceiving each sentence. Outcome of the study suggests that air flow doesn`t enhance recognition of continuous speech as it could not be demonstrated by hearing- typical and hearing- impaired population. Thus, in continuous speech study the beneficial effect of air-flow in speech perception could not be replicated.

The line of speech perception literature discussed above clearly illustrated the effect of AT integration in speech perception for several stimulus types (syllables or words), in different languages and for wide range of temporal asynchronies. But a similar benefit couldn’t be noticed in continuous speech. Factors that altered the result, remains unclear and needs further investigation. Just as AT and AV integration was found to be beneficial in enhancing understanding of speech, investigations were carried out to see if visuo- tactile integration could aid in better perception of speech, which will be discussed in the upcoming section.

2.2.3 Visuo – tactile (VT) integration in speech perception

It is quite interesting that speech, once believed to be an aural phenomenon, can be perceived without the actual presence of an auditory signal. Gick et al. (2008) examined the influence of tactile information on visual speech perception using the Tadoma method. They found that syllable perception of untrained perceivers improved by around 10% when they felt the speaker’s face whilst watching them silently speak, when compared to visual speech information alone.

Recently, effect of aero-tactile information on visual speech perception English labials (/pa/ and/ba/) in the absence of audible speech signal has been investigated by Bicevskis, Derrick & Gick (2016). Participants received visual signal of syllables alone or synchronously with air puffs on neck at various timings. Participants had to identify the syllables perceived from a choice of two. Even with temporal asynchrony between air flow and video signal, perceivers were more likely to respond that they perceived /pa/ when air puffs were present. Findings of the study shows that perceivers have shown the ability to utilise aero-tactile information to distinguish speech sounds when they are presented with an ambiguous visual speech signal which in turn confirms that visual –tactile integration occurs in the same way as audio-visual and audio-tactile integration.

Research into multimodal speech perception thus shows that perceptual integration can occur with audio-visual, audio-(aero)tactile, and visual-tactile modality combinations. These findings support the assumption that speech perception is the sub-total of all the information from different modalities, rather than being primarily an auditory signal that is merely supplemented by information from other modalities. However, multisensory integration could not be proven in all the studies described, even though most of it does. Hence a thorough understanding of factors that disrupted the study outcome is essential, which is elaborately explained in the next section.

2.3 Methodological factors that affect speech perception

In the previous sections of chapter, we discussed the wide range of behavioural studies in different sensory modality combinations (AV, VT and AT) that supported multisensory integration. But a similar result could not be replicated in continuous speech perception study described in 2.2.2 (Derrick etal., 2016). The next step would be to determine factors that potentially resulted in this variability. From a careful literature review, I found that methodological differences including the response type used to collect reports from the participants and specific stimulus differences like stimulus type ranging from syllable level to five-word sentence identification task might be those factors.

2.3.1 Effect of Response Type on Speech Perception

Speech perception studies have predominantly adopted two different ways in which individuals are asked to report what they perceived. These response types include open-choice and forced-choice responses. Open-choice responses allow individuals to independently produce a response to a question by repeating aloud or writing down, while forced-choice responses give preselected response alternatives out of which individuals are instructed to select the best (or correct) option. Moreover, forced-choice responses deliver cues that may not be spontaneously considered, but in open-choice responses generated by the participants, no cues are made available. However, open-choice responses can sometimes be difficult to code, whereas forced-choice responses are easier to code and work with (Cassels & Birch, 2014).

Therefore, different approaches may be used in these two response types. For example, an eliminative strategy might be adopted by participants in case of forced-choice responses, whereby, participants continue to refine alternatives by eliminating the least likely alternative until they arrive at the expected alternative (Cassels & Birch, 2014). A task that exhibits demand characteristics or experimenter expectations (“did the stimulus sound like pa?”) might give different results than one that does not (“what did the stimulus sound like?”) (Orne, 1962). Forced-choice responses are often influenced by demand characteristics. However, in case of open-choice responses expression of demand characteristics are easily avoided with non-directed questions.

In addition, literature evidences that the experimental paradigm can affect the behavioural response. Colin, Radeau and, Deltenre (2005), examined how sensory and cognitive factors regulate mechanisms of speech perception using the McGurk effect. They calculated McGurk response percentage by manipulating the auditory intensity of speech, face size of the speaker, and the participant instructions to make responses aligned with a forced-choice or an open-choice format. However, like many other studies, they instructed their participants to report what they heard. They found significant effect of instruction manipulation, with higher percentage of McGurk response for forced choice responses. But in the open choice task, the participant responses were diverse as they were not provided with any response alternatives. And the reduction in the number of McGurk responses in the open-choice task may be attributed to the participants being more conservative about their responses so that they could report exactly what they perceived. They also found an interaction between instructions used and the intensity of auditory speech. Likewise, Massaro (1998, p184-188) found that stimuli were correctly identified more frequently and elicited in a limited set (forced choice) than in an open choice task.

Recently, Mallick and colleagues (2015) replicated findings of Colin et al. (2005) when they examined the effect of McGurk effect in modifying parameters like population, stimuli, time, and response type. They demonstrated that the frequency of the McGurk effect can be significantly altered by response type manipulation, with forced-choice response increasing the frequency of McGurk perception by 18 % approximately, when compared with open choice for identical stimuli.

In the literature review provided, multisensory integration effect is not very consistent. Table given below summarizes the described studies from 2.2, providing an overview with respect to used stimuli, paradigm and effect of multisensory integration.

| Article/ Study | Response type/ Paradigm used | Stimuli used | Multisensory integration present or not |

| Thornton, N. E., & Erber, N. (1979) | Open choice (write down responses) | Sentences | Significant AV Integration |

| Grant, K. W., Walden, B. E., & Seitz, P. F. (1998) | Forced choice | Consonant and sentences | Significant AV benefit |

| Sumby, W. H., & Pollack, I. (1954) | Forced choice | Bi-syllabic words | Significant AV benefit |

| Macleod, A., & Summerfield, Q. (1990) | Open choice (write down response) | Sentences | Significant AV benefit |

| McGurk, H., & MacDonald, J. (1976) | Open choice (say aloud reponses) | Monosyllables | Significantly strong AV benefit |

| Sekiyama, K., & Tohkura, Y. i. (1991) | Open choice (write down response) | Monosyllables | AV integration present but not very strong as in English |

| Kuhl, P. K., & Meltzoff, A. N. (1982) | Forced choice (visual fixation) | Vowels | Significant AV benefit |

| Burnham, D., & Dodd, B. (2004). | Forced choice (visual fixation) | Monosyllables | Significant AV benefit |

| Ghazanfar, A. A., & Logothetis, N. K. (2003) | Forced choice (preferential looking) | Species specific vocalization | Significant AV benefit |

| Avril Treille, C. C., Coriandre Vilain, Marc Sato. (2014) | Forced choice | Monosyllables | Significant auditory -haptic (tactile) benefit |

| Fowler, C. A., & Dekle, D. J. (1991) | Forced choice | Monosyllables | Significant auditory -haptic (tactile) benefit |

| Gick, B., & Derrick, D. (2009) | Forced choice | Monosyllables | Significantly strong auditory – tactile benefit |

| Derrick, D., & Gick, B. (2013) | Forced choice | Monosyllables | Significantly strong auditory – tactile benefit |

| Derrick, D., & Gick, B. (2009b) | Forced choice | Monosyllables presented with metallic taps instead of air puff | No auditory – tactile benefit |

| Derrick, D., O’Beirne, G. A., Rybel, T. d., & Hay, J. (2014) | Forced choice | Monosyllables | Significantly strong auditory – tactile benefit |

| Goldenberg, D., Tiede, M. K., & Whalen, D. (2015) | Forced choice | Monosyllables | Significant auditory – tactile benefit |

| Gick, B., Ikegami, Y., & Derrick, D. (2010) | Forced choice | Monosyllables | Significantly strong auditory – tactile benefit |

| Derrick, D., Heyne, M., O’Beirne, G. A., Rybel, T. d., Hay, J. & Fiasson, R. (2016) | Forced choice | Syllables and words | AV integration present but not very strong as in English |

| Derrick, D., O’beirne, G. A., De Rybel, T., Hay, J., & Fiasson, R. (2016) | Open choice (say aloud) | 5-word sentences | No auditory – tactile benefit |

| Gick, B., Jóhannsdóttir, K. M., Gibraiel, D., & Mühlbauer, J. (2008) | Open choice (say aloud) | Disyllables | Significant visuo – tactile benefit |

| Bicevskis, K., Derrick, D., & Gick, B. (2016) | Forced choice | Monosyllables | Significant visuo – tactile benefit |

The conclusions of Colin et al. (2005) and the literature review suggest that response choice may be a significant contributor to variability in speech perception. In case of forced-choice responses, participants can compare their percept with available response alternatives. However, in case of open-choice responses, participants attempt to retrieve which syllable closely matches their percept from an unrestricted number of possible syllables.

2.3.1 Effect of stimulus type on Speech Perception

As outlined in previous sections (2.2.1 and 2.2.2) and illustrated in the table, the type of stimuli may also affect the behavioural outcome. Use of continuous speech such as phrases or sentences containing confounding factors (semantic information, context information, utterance length etc.) requiring complex central processing rather than syllables disrupted the findings of the study showing no effect of tactile in speech perception (Derrick etal., 2016).

Similarly, Liu and Kewley-Port (2004) measured vowel formant discrimination in syllables, phrases, and sentences for high- fidelity speech and found that the thresholds of formant discrimination were poorest for sentences context, the best for the syllable context, with the isolated vowel in between indicating that complexity of task is increased with higher stimulus type.

In summary, literature suggests stimulus type, represents context effect, is a product of multiple levels of processing combining the effect of both general auditory and speech-related processing (e.g., phonetic, phonological, semantic and syntactic processing). Hence type of stimuli (e.g. sentences) in a study can contribute to an increase in the task complexity.

So, methodological factors, response type and stimulus type, discussed above can be the possible features that interfered in multisensory integration tasks of speech perception studies. So, in this study, I would like to take these aspects into consideration to generate the best experiment design to study aero-tactile integration in speech perception.

Cite This Work

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing stye below:

Related Services

View allRelated Content

All TagsContent relating to: "Physiology"

Physiology is related to biology, and is the study of living organisms and how they function. Physiology covers all living organisms, exploring how the body performs basic functions in relation to physics and chemistry.

Related Articles

DMCA / Removal Request

If you are the original writer of this literature review and no longer wish to have your work published on the UKDiss.com website then please: