Challenges Faced by Private Landlords Due to Regulations

Info: 8378 words (34 pages) Example Literature Review

Published: 23rd Nov 2021

Tagged: HousingSocial Policy

CHAPTER I – INTRODUCTION

1.1 Dissertation Introduction

The intention of this thesis is to introduce the reader to the research topic and provide an insight into the challenges that private landlords face with adherence to the continued rise in standards enforced through HMO legislation. This research specifically targets the private sector as it is believed that there is a lack of guidance for smaller landlords as opposed to the readily available knowledge and expertise within larger public organisations such as LA’s and RSL’s. The private rented sector plays an instrumental role in delivering homes throughout boroughs up and down the country and without its input, immense pressure would be forced upon the Government to deliver properties for those in need.

The growth of the private rental market heavily relies on investors studying economic patterns within the industry and making educated decisions on when is best to invest in the property market. Unfortunately, with uncertainty around contributing factors such as mortgage interest rates, Government incentives to help promote the growth of owner-occupiers and increased health and safety control measures under the Housing Act 2004, many landlords have been left with doubt on the longevity and sustainability of their current investments. The property market is being seen as more of a gamble than a feasible investment opportunity. Many current investors argue that they are not returning the yields required to break even, let alone form a lucrative income and so many have turned to multiple occupancy lets or ‘HMO’s’ as a way to generate more rental return. In a simplified manner, the intention to create more living space per m2 through the adaptation of properties in order to generate more income. However, with increased control measures under HMO legislation and a lack of knowledge and regulation for private landlords, the number of HMO’s with sub-standard living conditions is causing major concerns for tenants and local authorities. The Governments strategy to tackle these issues through substantial penalties and fines when landlords fail to comply has impacted the growth of the market.

In an effort to address the concerns within the market, this thesis identifies clear and concise aims and objectives that can be found in bullet points 1.3 and 1.4 which will each be achieved through a selection of quantitative and qualitative methodology.

Finally, the data will be analysed and a conclusion will be drawn upon the field research conducted. Personal recommendations will be made based on the information gathered in an attempt to provide a solution to gaps within the market and help promote reinvestment.

1.2 Research Context

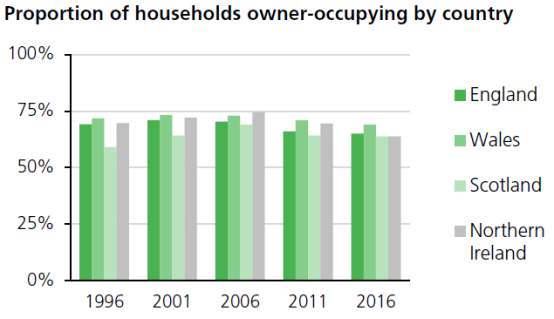

The housing market has seen a steady increase in the private rented sector over recent years with more individuals opting to invest in buying a second property with the intentions to accumulate rent as a secondary source of income whilst respectfully also looking to supplement their pension. However, the increase of the private rented sector has been compromised by the steady decline in the owner-occupier market. This is supported by the data extracted from the ‘House of Commons Briefing Paper on Home ownership and renting demographics’ in Figure 1 and Table 1 below:

Figure 1: Owner Occupier Statistics 1996-2016 – (Barton, 2017)

Table 1: Supplementary Data – Owner Occupier Statistics 1996-2016 – (Barton, 2017)

Back in 1996, the Government initiated its ‘Buy to Let’ scheme, which initially seemed to offer a lucrative avenue for investors to gain capital through the rental of properties. During its infancy stages, this seemed to work and attracted increased numbers of private investment. The dataset in Figure 1 identifies that between 1996-2006, the owner-occupier market in England rose from 13,472,000 to 14,743,000, a + 9.43% increase within 10 years.

The following 10 years between 2006-2016 however indicated a substantial decline in the owner-occupier market with figures decreasing from 14,743,000 to 14,500,000, equating to a decrease of – 1.64%. These figures not only indicate that the market remained relatively saturated during this time but the 2008 financial crisis clearly influenced the owner-occupier market and contributed to the markets most impacted period in 20 years.

Figures indicate a disappointing increase of only + 7.63% in owner-occupiers in England over the past 20 years and with statistics published by ONS showing a population increase of 6,749,000 between 1996-2016, it is clear that owner-occupation has taken a back seat over rented accommodation.

The West Midlands region saw an increase of + 8.96% of owner-occupiers between 1996-2006 with numbers increasing from 1,490,000 to 1,568,000. Between 2006-2016, the region saw a decrease of – 2.86% with numbers falling from 1,568,000 to 1,523,000. An overview of the West Midlands owner-occupier statistics between 1996-2016 indicate a disappointing increase of only 5.83%. These- figures confirm that the owner-occupier market was heavily impacted during times of economic stress and despite the Governments incentives to initiate growth, regions such as the West Midlands were amongst the worse impacted.

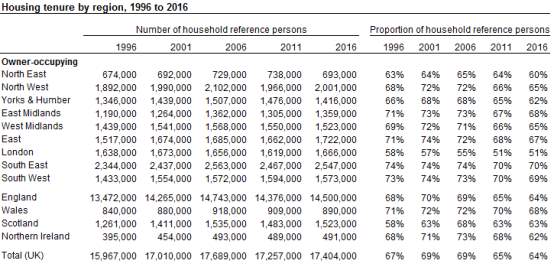

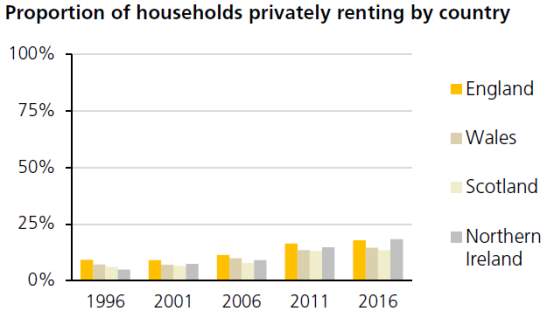

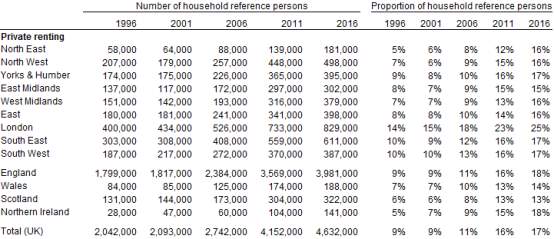

Figure 2: Private Rental Figures 1996-2016 – (Barton, 2017)

Table 2: Supplementary Data – Private Rental Figures 1996-2016 – (Barton, 2017)

With owner occupation figures declining, comparison turns towards the private rented market. The dataset shown in Figure 2 and Table 2 indicate a steady incline between 1996-2006 with numbers rising from 1,799,000 to 2,384,000, a + 32.5% increase in England. Between 2006-2016, England saw a rise from 2,384,000 to 3,981,000, an increase of + 66.98%. An overall impressive increase of + 121.28% between 1996-2016 in the private rented market supports the expected growth.

The West Midlands, region saw an increase of + 26.14% of private rented tenures between 1996-2006 with numbers increasing from 151,000 to 193,000. Between 2006-2016, the region saw an increase of + 96.37% with numbers increasing from 193,000 to 379,000. A total regional increase for the West Midlands between 1996-2016 indicated an impressive + 150.99% increase of private rented tenures.

These figures pose the question, why is the owner-occupier market failing to flourish? Many areas may contribute to this decline such as unemployment rates, immigration, rising house prices and interest rates and more recently, uncertainty around the economic future exiting the single trade market. Similarly, a question can be posed as to why the private rental market has returned such impressive figures over the past 20 years. It is understood that the introduction of the use of HMO’s to generate better returns for investors has attracted more investors into becoming private landlords but with more inexperienced investment in HMO’s comes more need for regulation to ensure that certain health and safety standards are met by landlords looking to rent their properties. This thesis will look to identify the impact of the HMO regulations enforceable under the Housing Act 2004 have influenced the private rented market and how the field has taken to these changes.

Although the Governments demands to increase the number of properties built per annum to accommodate rising population figures and assistance for first time buyers with ‘help to buy’ schemes, the increase in property prices has left some with no option but to rent. Private investors have noticed this gap within the market and noticed that multiple occupancy lets can prove to be far more lucrative that single occupancy lets. However, a lack of property knowledge along with no form of regulation for private landlords may be contributing factors to the expanding number of overcrowded, poorly maintained and non-compliant HMO’s being let by ‘rogue landlords’ in order to achieve lucrative yields.

In an effort to challenge the increasing number of substandard living conditions in HMO’s, the Government introduced the HHSRS as a template for local authorities to formally categorise and enforce landlords who fail to provide safe housing conditions. The introduction of mandatory licencing in 2006 was also introduced to certify which properties fell under HMO regulations and which did not. The cost of licensing of HMO’s along with the added pressures of enforceable legislation and civil and custodial penalties has not seemed to outweigh landlords objectives to capitalise on yields through supplying non-compliant HMO’s. The increased control measures were intended to offer local councils who were already under staffing pressure the power to enforce strict penalties in a ploy to tidy up their districts of substandard living arrangements however this tool seems to have disconcerted potential investors instead of providing a Government based support network.

1.3 Aim

The aim of this research is to investigate whether the latest changes to the Housing Act 2004 regarding HHSRS and HMO licensing conditions has fulfilled its purpose to improve the living standards within the private rental sector in the West Midlands and to establish what needs to be done to further improve living standards.

1.4 Objectives

This aim will be achieved through the following objectives:

1. To conduct a critical review of literature based on the composition of the private rented market in the West Midlands in specific, housing stock which falls under the mandatory licencing terms of the Housing Act 2004.

2. To conduct a critical review of the literature relating to the changes made to HMO legislation and relevant housing legislation in order to counter health and safety within mandatory licences properties and the consequences faced with failure to comply.

3. To collate data in the form of a mixture of questionnaires and in depth interviews with direct landlords and managing agents to identify their awareness and understanding of HMO legislation and their experience in delivering the requirements of the law. To lastly seek their personal opinions on the practical effectiveness of delivering these requirements.

4. To conduct research directed towards managing agents and landlords to establish where responsibilities sit in terms of compliance to legislation with the aim to establish clarity on the interpretation of the law when wording is unclear.

5. To study what precautions managing agents take to ensure compliance to HMO legislation and to draw conclusion on the pros and cons on the mandatory licensing of certain HMO’s.

6. To analyse, evaluate and summarise the dataset to determine the challenges faced with HMO legislation in the private rental sector.

7. To draw conclusions from the findings and provide recommendations to mitigate uncertainty around the potential misinterpretation of the law and conclude common difficulties that are faced with HMO properties.

1.5 Research Methodology

A literature review has been conducted to achieve objectives 1 and 2 through a critical review of existing publications, journals and books associated with the subject matter (Fisher, 2010). The literature review has been categorised into (7) sections each which have identified specific subject areas. Section 8 concludes these findings and proves a summary of the literature review. A diagram has been provided to indicate the main discussion points.

1.6 Research Limitations

One limitation was the selection of information available for the literature review, in specific the key changes within legislation leading up to the research question. In order to achieve the criteria of this thesis, the information needed to be condensed to the most relevant subjects leading to the changes in HMO legislation.

Another limitation is the lack of information published directly relating to landlords and managing agents in the West Midlands region. As a lot more information was required, a series of questionnaires and in depth interviews was required to specify how the changes in HMO legislation affected the region.

1.7 Dissertation Content

Chapter Contents

Chapter I Chapter I aims to introduce the reader to the thesis and outlines the rationale for this research.

Chapter II The literature review will demonstrate the development of the private rental sector since the initial changes in HMO legislation in 2005.

Chapter III To be completed

Chapter IV To be completed

Chapter V To be completed

CHAPTER II – LITERATURE REVIEW

2.1 Introduction

This literature review will demonstrate the development of the private rental sector since the initial changes in HMO legislation in 2005 and evaluate what issues were prevalent before its introduction. This review will be categorised into five key areas of research detailing a full representation of the issues surrounding HMO legislation.

The aim of this literature review is to develop a knowledge of how the private rental sector has expanded over the past ten years and to detail what economic and legislative influences may have initiated this growth. This literature review will exploit the circumstances that led to the forced changes in legislation set out in 2005.

2.2 Timeline of significant housing legislation (1915-2018)

The lack of direction within the UK’s private housing market has historically been problematic with major concerns around the living conditions for tenants. The Governments unsuccessful attempts to control the standards of living has led to many changes in recent legislation, some might argue displaying a lack of clarity and inconsistency.

English property law originally dates back to post-Norman invasion in 1066 when the first act of William the Conqueror in 1067 declared that every acre of land in England belonged to the monarch. It was not until 1925, somewhat 858 years later when the government decided to take a leap to modernise the law.

2.2.1 The Increase of Rent and Mortgage Interest (War Restrictions) Act 1915

A shortage of housing during WWI stimulated a response from the Government to introduce rent controls within the private rented sector. The aforementioned act was designed to prevent landlords from profiteering from premium rents during a period of high demand for housing. Despite the intention for rent control to act as a temporary measure, such controls sustained in prevalence on certain dwellings until January 1989.

2.2.2 Law of Property Act 1925

In 1925, Lord Birkenhead introduced the Law of Property Act (LPA) 1925 with the intention to ‘facilitate and cheapen the transfer of land’ due to the preceding law of land transfer proving lengthy and cumbersome. Although many of the principles have since been updated and supplemented over time, the framework of this act remains in effect today and therefore deemed an iconic revolution in property law.

2.2.3 The Rent Act 1957

Sir Winston Churchill’s second reign under parliament saw a heavy focus on the housing crisis and in particular, the living conditions under the private rental sector. In 1953 the White Paper publication ‘Housing – the next steps’ responded to the preceding rent structures as “hopelessly illogical” and so in response the Conservative party recognised the restrictions forced upon private landlords offered little to no room to provide maintenance of their properties.

It was under the following consecutive years of Conservative leadership the introduction of The Rent Act 1957 was implemented in an effort to stimulate the housing market and encourage private landlords to invest in property with the basis that rental values would be based on gross rateable value. This format of legislation proved unsuccessful in meeting its objectives as the private rental sector witnessed a decrease in figures from 45% of private rented properties in April 1951 to 25% by December 1961. The conclusion drawn from the substantial decrease in figures indicated that the controlled rents below market rent and decontrol on vacant possession of properties enabled landlords to evict sitting tenants to either increase rents or sell the property to gain capital as property values with a sitting tenant were considerably less than that without. A process that became familiarly known as ‘Rachmanism’ named after Perec Rachman, a famous landlord operating in Notting Hill London, notorious for the exploitation of his tenants through such means.

2.2.4 Protection from Eviction Act 1964

Following the Conservative parties lack of success in fixing the downward spiralling housing market, the Labour Government was voted into power in 1964. With a heavy focus on the housing market, the first act passed under Prime Minister Harold Wilsons jurisdiction was the Protection from Eviction Act 1964. The measures that this Act adapted were focused around the protection of tenants from being evicted from properties for the expense of capital gain and without no true motive. The Act detailed four key categories:

1. Harassment – The first Act that made the act of harassing a tenant into vacating a property a criminal offence.

2. Due process – The concept of landlords having to obtain a court order for possession of the property should tenants stay beyond their contractual tenancies against the will of the landlord. This Act applied to tenants falling both in and out of the scope of Rent Acts.

3. Notices to Quit – A formal document that landlords had to issue giving tenants a minimum of four weeks’ notice irrespective of the terms of the tenancy. This document was similarly used for residents wishing the end their tenancies.

2.2.5 The Rent Act 1965

The Labour Government reformed The Rent Act 1957 legislation on two occasions, which resulted in the introduction of The Rent Act 1965. The prime focus of this legislation was the implementation of regulated tenancies with long term security of tenure ‘fair rents’ set by rent officers employed by the local councils with a vision to boost the housing market. In response, this had an adverse effect as landlords opted to sell their properties to make capital instead of renting them to tenants who would have the rights to security of tenure and rights to succession.

2.2.6 The Housing Act 1980

On the 3rd October 1980, Margaret Thatcher introduced The Housing Act 1980 in a ploy to mend the market. The aim was to relax the constraints of legislation from the preceding acts to try to influence investment by means of decontrolling 400,000 controlled tenancies into regulated tenancies. This was achieved by implementing rent reviews every two years instead of three to aim to equip landlords the tools to remain in line with inflation rates. This was aimed to provide a non-biased approach to both landlord and tenant.

Unfortunately, these attempts proved ineffective as the continuation of properties being sold following vacant possession sustained highs. It seemed as though investment outside of the property market seemed more lucrative.

In conclusion, this increase of vacant possession because of The Housing Act 1980’s decontrolled legislation permitted landlords with the ease of sale and so it was argued by some critics that shorthold tenancies did not better the situation. Shelter, the housing and homeless charity predicted this in their comments made in 1979:

“Shorthold tenancies (would) destroy the long established principle that a tenant who pays his rent should be secure from arbitrary eviction. More tenants will become homeless, and tenants will be too scared to ask for essential repairs and improvements.”

2.2.7 Margaret Thatcher’s Right to Buy Influence (1980-2018)

Another major influence introduced by Margaret Thatcher and the Conservative party was the independence for council tenants to purchase their rented accommodation through the Right to Buy scheme. The Housing Bill was published on 3rd December 1979 and granted tenants discounted rates on the purchase of their council house based on how long they had lived there for. Tenants who had been in situ for up to three years were eligible for 33% discount on the market value on their home, increasing in stages up to 50% discount of market value for 20 years tenure.

Thatcher’s vision to create a property owning democracy through the Right to Buy scheme seems to have left the Government compensating excessive costs towards housing benefit. Figures indicate that approximately 40% of homes sold under the Right to Buy scheme are now owned by private landlords which in turn are being rented back by those in receipt of housing benefit. On the contrary, ex council tenants who opted to keep their Right to Buy have found a gap within the market through the use of sub-letting. A fundamental issue with this is the lack of statutory right to enter these properties to inspect alterations or living conditions. Many are thought to have been adapted to form multiple occupancy properties that do not comply with the current HHSRS and HMO regulations.

2.2.8 The Housing Act 1988

Widely considered as one of the most influential pieces of legislation bought into act concerning the private rental sector, the stipulations within this act abolished the system on rent regulation as of 15th January 1989. Under Part 1 of the Act, with the limitation of some exceptions, no new regulated tenancies could be formed. This influential change was a desperate attempt to revitalise the saturated market and reinitiate trust and investment within the sector. In response, the new legislation required properties to be advertised at the current market rent with an aim to increase yield percentages and boost interest within the market through phasing out historic Rent Act tenancies in replacement for the new, non-biased assured tenancies. The new assured tenancies introduced a minimum tenure of six months, which allowed tenants to apply for fair rent assessments to ensure that the property they lived in was in line with its market value. Critics argued that the increase in rent would dramatically rise and so too would the requirement for housing benefits. Figures show that in 1987, 60% of the private rental market were claiming housing benefits and with the projected rise in rents this would not only put a strain on the Government but also create a poverty trap as undoubtedly the eligibility criteria for support would alter.

Another fundamental article within the Act was the introduction of tighter controls over landlords statutory obligations to disrepair and specifically tenants’ rights to civil remedies should these standards not be met. A key piece of legislation that is still regulated today.

2.3 Impacts of Stamp Duty Taxation

The history of Stamp Duty originally dates back to 1694 where it was introduced as a means to finance the war with France. Although this was originally an interim plan, we see that the taxation is still present in 2018.

The UK’s economy has been through many influential changes over recent years, with two major financial recessions, a coalition Government and although still in its infancy stages, Brexit is likely to have some impact on the market.

In March 2005, Gordon Brown raised the entry level for Stamp Duty taxation from £60,000 to £120,000. This was the first major impact for the 0% bracket market since March 1993 when the 0% bracket was upped from £30,000 to £60,000. Although the intentions were noble, critics say that these figures were not in line with the average house prices causing many potential buyers to fall within taxation brackets and therefore resulting in a decrease in owner-occupiers and an increase in private rented tenures.

Figure 3 below itemises the average house price per region in the UK from the tax changes in 2005 compared to the average house prices in 2018:

Table 3: Average House Price per Region 2005 v 2018 – Land registry reference

| Region | Average House Price 2005 | Average House Price 2018 | % +/- |

| North East | £112,596 | £128,218 | 13.80% + |

| North West | £120,919 | £158,152 | 30.79% + |

| Yorkshire & The Humber | £121,919 | £155,385 | 27.44% + |

| West Midlands | £141,930 | £192,648 | 35.69% + |

| East Midlands | £137,121 | £186,071 | 35.73% + |

| East of England | £173,743 | £288,468 | 66.03% + |

| London | £231,263 | £471,986 | 104.09% + |

| South East | £196,494 | £322,489 | 64.12% + |

| South West | £179,376 | £250,186 | 42.20% + |

With the average house prices per region listed in Table 3, it is evident that on average, the only area to benefit from the raised entry level for Stamp Duty taxation was the North East at the initial stages in 2005. This data again, supplements the evidence provided in Tables/Figures 1 and 2.

In March 2006, the 0% taxation bracket was raised to £125,000 where it has remained since however it seems as though this increase has again failed to fall in line with the current average house prices. The average house price within the West Midlands in 2018 has increased to £192,648, a total £67,648 over the entry-level taxation bracket. This criticism is supported by the statistics showing the increase in private rented tenures vs the decrease in owner-occupiers within the West Midlands. The gap between the average house price and entry level taxation avoidance is so far adrift that the West Midlands owner-occupier market is now almost proportionate to a 50/50 split between owner-occupier and rented accomdation.

2.4 Composition of the UK housing market

The composition UK housing market has significantly changed over the past 100 years and in 1914, just prior to the Increase of Rent and Mortgage Interest (War Restrictions) Act being passed, the private rented sector was estimated to be responsible for 90% of all dwellings in the UK. Fast forwarding to 1991 and it was estimated that only 7% of the dwellings in the UK were privately rented, a decrease of 83% in 77 years. (Balchin, 1995)

Private HMO’s supply an important service to the public and local councils throughout the West Midlands as they supply affordable living in urban areas and university towns where budgets for accommodation are lower than surrounding areas. The ONS reports that the total number of private HMO’s in England and the West Midlands region is unknown, the only figures presented are the total number of public sector HMO’s. A rationale behind the lack of data around this particular subject has been identified to be down to the incapability to identify a HMO externally as the main structural changes to form a HMO from a residential dwelling are formed internally. The only figures produced were estimates based on information fed back from audits of home condition surveys.

It was noted that in 1991, approximately 1,638,000 occupied properties were deemed unfit for human habitation. This remarkable figure represented 7% of properties in the UK. (Leather and Morrison, 1997) These figures exemplify the severe lack of housing standards being delivered in private rented homes in the UK and the essential requirements for the Government to implement stringent regulations and so in 2005 the HMO regulations were introduced under the Housing Act 2004.

A report issued in 1995 by the Department of Environmental Health estimated a total 334,000 HMO’s in England and Wales that were deemed in serious disrepair, whilst 81% did not have the adequate requirements of fire escape routes and 80% had sub-standard amenities. (Balchin, 1995)

A report issued in 2001 by the Office of the Deputy Prime Minister noted that 10% of the households forming the private rented sector in the UK and 3% of owner-occupiers properties were classed as unfit for human habitation mainly due to the ageing housing stock, 95% of which was built pre 1919.

Naturally, many of these pre 1919 properties that were re-designed to house multiple tenancies to accommodate the aftermath of shortage in housing post World War I lacked suitable living standards due to their age and cost of maintenance and repair. In an effort to improve housing conditions during the 1970’s, local authorities initialled large-scale demolition programmes of sub-standard properties however this was eventually put to a halt as the demolitions were superseding development thus, causing a housing shortage. (Mullins and Maurie, 2006)

In the years leading up to the introduction of the latest HMO legislation, local authorities enforced improvement of conditions of private rental properties through Section 11 of the Landlord and Tenant Act 1985 which enforced the landlords obligations to carry out basic repairs. Although this enforced landlords to keep elements such as the structure, drainage and general amenities in repair, these requirements did not extend to improving the condition of the properties and often lead to very basic remedial works being carried out. Instrumental requirements such as fire protection did not become prevalent until the Regulatory Reform (Fire Safety) Order 2005.

Decreased staffing levels within the local authorities made it difficult to enforce the housing standards set within housing legislation and so the Government introduced incentives such as repairs grants and accreditation schemes allowing landlords the right to apply for repairs to be completed on their house and in turn gain accreditation through the authorities therefore making it easier to find tenants. (ibid)

It soon became clear that the accreditation schemes only seemed to offer a solution in areas of low demand and despite the poor living conditions, areas of high demand continued to find tenants without the need of accreditation schemes. Suggestions made by the Chartered Institute of Housing for the Government to enforce licensing on all private sector properties were rejected on the terms that administering this would be a far greater exercise than what was manageable. Instead, the Government decided to focus their attention solely towards the licencing of HMO’s as it was seen that these posed the highest health and safety risk through the lack of enforcement of fire safety and consequently, mandatory and selective licencing was introduced. (Mullins and Murie, 2006)

2.5 The birth of buy-to-let

The buy-to-let framework was initiated in 1996 by the ARLA group with the sole purpose of encouraging investors back into the private rental market. Adrian Turner, ARLA’s Chief Executive quoted in the 2006 PRS report:

“ARLA went out on a limb to launch the modern concept of buy-to-let in September 1996, backed by a far seeing panel of mortgage lenders. Our aim was to bring more and better quality property to the private rented sector. Ten years on we are the first to admit that we could never have foreseen the success this was to be for investor landlords, their tenants and the private rented sector.” (Turner, 2006)

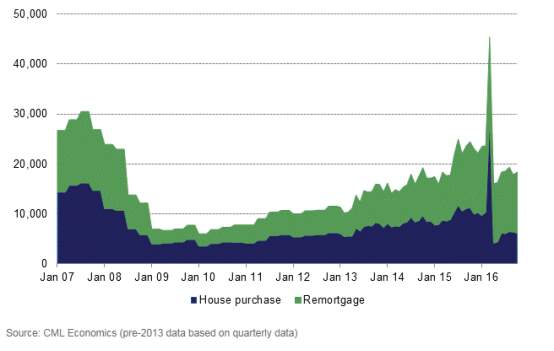

Statistics indicate that the buy to let market is still recovering from the 2008 financial crisis where it hit a record low. The overall UK market has seen a steady incline in the amount of buy to let mortgages since January 2009 and hit its record high in January 2016 with over 40,000 buy to let loans in place. Figure 4 below indicates the buy to let market growth between January 2007-2016.

Figure 4: Number of buy to let loans – January 2007-2016 – (CML, 2016)

Although the market seems to be recovering back to its original state, David Cox, Chief Executive of ARLA quoted in the PRS report 2018:

“This month’s results very much show a ‘business as usual’ period for the private rented sector, but this isn’t necessarily a good thing. Supply is still too low and almost a quarter of tenants are experiencing rent hikes every month as landlords try to recoup the costs lost trying to keep on top of all the recent legislative changes – including the recent energy efficiency deadline.”

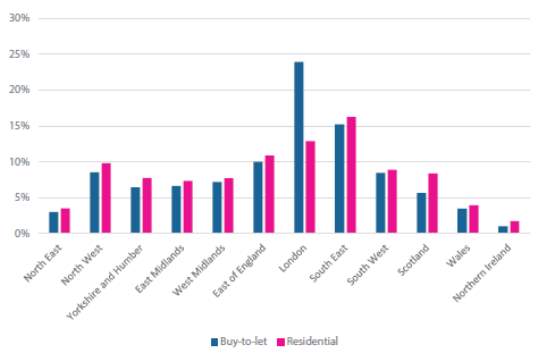

It is clear that the changes within HMO legislation are becoming more of a concern with the private rental market, which poses special concern within the West Midlands. Regional data supplied on the geographical spread of buy to let mortgages in Figure 5 indicates that the West Midlands housing sector is an almost 50/50 split between buy to let and residential mortgages. This indicates the importance of the buy to let and private rented facility within the West Midlands housing market.

Figure 5: Geographic spread of buy to let vs owner-occupier loans – (Shawbrook, 2018)

David Cox continued to quote:

“For the last two decades, successive Governments have passed significant amounts of complex legislation for landlords, none of which have been properly policed or adequately enforced – but most of which cost decent landlords a lot of money.

This is why we’re so supportive of the Government’s proposals to crack down on rogue agents, and more recently, plans to confiscate properties from criminal landlords. The announcements mark a sensible shift towards focusing on the root cause of the issues affecting the sector, rather than trying to find solutions to individual problems. This coupled with greater rental stock is the key to fixing Britain’s broken rental sector.”

The new changes being enforced in HMO legislation are likely to impact in the region of 50% of the housing market within the West Midlands. This poses a great risk regionally as the Governments tighter constraints on health and safety within properties could end up leaving a void within the market. Oppositely, these changes could help improve the market by flushing out the rouge landlords and therefore allowing honest, compliant landlords to make up the shortfall.

2.6 Requirements of HMO legislations

All forms of HMO’s are subject to two main pieces of legislation that fall under the Housing Act 2004:

1. Management of Houses in Multiple Occupation (England) Regulations 2006

2. Licensing and Management of Houses in Multiple Occupation (Additional Provisions) (England) Regulations 2007

The guidelines for generating a compliant HMO are all set within these regulations and include certain management and health and safety responsibilities for the landlord to adhere to. Failure to comply with legislation can lead to court proceedings with no maximum fine limits.

2.6.1 Licensing Terms

There are two forms of property licencing that may be required when renting a private property. Failure to hold the relevant licence is a breach under the Housing Act 2004 and can be subject to legal proceedings.

It is the landlords responsibility to ascertain whether their property requires a licence. If the landlord is unsure then contact should be made with the local council who can assist. If an agent is responsible for the management of the building, the agent is able to apply for the licence on behalf of the landlord.

Mandatory licencing is the main type of licencing required for all large HMO’s. A property is defined as a large HMO is all of the following apply:

1. It is rented to 5 or more individuals who form more than 1 household.

2. The property is at least 3 storeys high

3. Tenants share toilet, bathroom or kitchen facilities.

Licences are valid for a maximum of 5 years and upon expiry, the landlord must renew should the property still consist of the HMO conditions. The costs of licencing can vary between £0-1500 depending on the constituency; however, the average cost of mandatory licencing in West Midlands is £387. Although the cost of licencing doesn’t seem excessive, the possibility of owning a mandatory licensed HMO can incur many unexpected costs, both in terms of building compliancy and management and the consequences of non-compliancy.

Selective licensing is the second type of licencing that may be required to a property if it does not fit under the mandatory licencing conditions; however, this form of licencing depends on the area of the property. For instance, certain districts within a council may be subject to selective licencing for example, All Saints in Wolverhampton. Councils look to summon selective licencing terms in districts to help regulate the control of housing in line with the areas strategic housing requirements.

2.6.2 Planning Permission

As of 1st October 2010, new regulations came into force which directly impacted properties let to groups of sharers such as students, migrant workers and young professionals.

One notifiable change within legislation is that planning permission will no longer be required where single house/flats are occupied by a family that is rented out as a small shared house/flat or bedsit for the first time after April 2010 unless the local planning authority have made the area an Article 4 area.

Article 4 direction areas are implemented by local councils in order to maintain control over the amount of HMOs being built or converted within an area. This means if the area is an Article 4 area, it will not be possible to convert a HMO without planning permission. Critics feel that the introduction of Article 4 will reduce the amount of investment into the private sector due to the continued efforts of gaining planning permission along with the burden of meeting building regulations and the overall lengthy time from start to completion. On an opposing stance, investors may look to exploiting areas that are currently not Article 4 listed but are in the pipeline to be and using this piece of legislation as a support boundary to local competition. In conclusion, buying in an area before it becomes Article 4 may optimise the value of the property due to the lack of incoming competition within the area.

It is important to note that HMO’s built prior to an area becoming Article 4 will not be subject to the conditions within this piece of legislation.

2.6.3 Energy Performance Certificates

As of 1st April 2018, all private landlords must improve the energy efficiency rating of their buildings to a minimum EPC rating of E before the property is rented out unless the landlord qualifies for an exemption through the Public Exemptions Register.

For all continuing tenancies, landlords have until 1st April 2020 to ensure that their property meets a minimum rating of E on the EPC.

Prohibition orders will be served on all properties failing to comply with this requirement meaning that landlords will not be permissible to rent the property until the EPC is to standard. Any landlords found breaching their prohibition orders will be subject to a minimum £2000 fine per item breached with no maximum fine.

2.6.4 HHSRS

The HHSRS controls the standard of each property on a risk based approach and in particular are targeted towards HMO’s which are susceptible to tenant complaints. The assessment is based on 29 housing hazards which may impact the health and safety of current of future occupants.

The enforcement framework of the HHSRS is determined by the presence of a hazard either above or below the threshold set within the regulations. Hazards that are set above the threshold are known as Category 1 hazards, and those below the threshold are known as Category 2 hazards.

On identification of the category of hazard, the council must take the necessary enforcement actions upon the landlord. The action taken will depend on the severity of the hazard, however these will general be dealt with through the following procedures:

1. Improvement notice being served on the landlord whereby the HHSRS assessor identifies a breach in health and safety law. Improvement noticed generally serve landlords with a date as to what and when remedial action must be completed by (usually 28 days). If the landlord fails to complete the identified work or makes little progress then the local council have the authority to complete the works and recoup any costs from the landlord.

2. Prohibition order being served on the landlord whereby the HHSRS assessor is authorised to stop the entire or part use of a building or restrict the type or number of people living there due to the category of hazards identified. Landlords have the right to appeal prohibition orders within 28 days, however failure to comply with overturned appeals can lead to prosecution.

3. Hazard awareness notice being served on the landlord advising the person on whom it is being served on of the existence of a hazard. However, hazard awareness notices are not enforceable and down to the landlord whether action is taken.

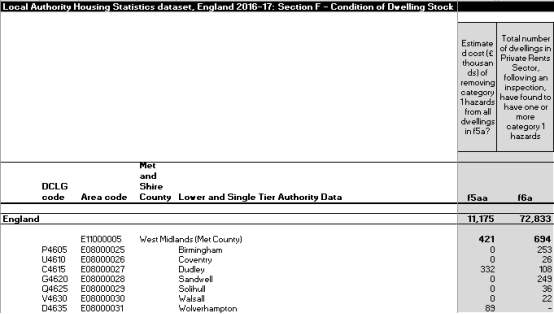

Between 2016/17, 3140 properties were identified as being mandatory licensable HMO’s with Category 1 hazards. Figure 6 below indicates the total amount of properties identified in the West Midlands with Category 1 hazards and the total costs of remediation:

Figure 6: Category 1 hazards and cost of remediation in West Midlands 2016-2017

The total cost of remedial works following HHSRS assessors identifying Category 1 hazards in the West Midlands alone cost in the region of £421,000 split across 694 properties, averaging out at £606 per property.

2.6.5 Regulatory Reform (Fire Safety) Order 2005

Introduction of the RRO 2005 has placed responsibility on landlords and managing agents for fire safety in HMO’s. Guidance on fire safety for landlords is provided by Lacors Housing Fire Safety which helps landlords and managing agents ensure that their buildings comply with HMO fire standards. As a minimum, all HMO’s should have the following fire safety measures in place:

1. Hard wired smoke alarms

2. Heat detectors

3. Fire doors leading from high fire risk areas to protected fire escape routes.

4. Emergency lighting in large HMO’s.

In addition to the installations costs which can easily rise into the thousands of pounds mark depending on the building size and layout, HMO landlords should be aware of the ongoing servicing and maintenance costs of equipment. HMO guidelines state that all safety equipment should be serviced in line with the manufacturer’s recommendations combined with HMO fire safety regulations. An example of the servicing frequency schedule of fire and electric equipment that can be found in a typical HMO is listed in Table 4:

Table 4: Fire and Electric servicing frequencies

| Equipment Type | Explanatory | Frequency |

| Automated Doors | Doors that open/close under their own power | Every 6 months |

| Dry Riser | Pipes in multi-story properties which fire brigades can use to pump water to upper floors | Every 6 months |

| Electric Gates | Gates that open/close under their own power | Every 6 months |

| Emergency Lighting | Maintained (may also operate as normal light) Non maintained | FLICK test – Every 1 month |

| Central battery or individual batteries | Every 12 months | |

| Fire Alarm Systems | Fire Panel | Every 3, 6, 9, 12 months |

| Fire Alarms | FLICK test – Every 1 month | |

| Fire Blanket | Every 12 months | |

| Disabled Refuge Systems | Every 12 months | |

| Fire Extinguishers | Every 12 months | |

| Fire Hose Reel | Every 12 months | |

| Intruder Alarm System | Every 12 months | |

| Panic Alarm System | Every 12 months | |

| Sayphone Dispersed Alarm System | Similar to Warden Call systems except handsets are not connected through dedicated wiring | Every 12 months |

| Smoke Curtain | Lowers automatically in case of a fire to keep smoke away | Every 6 months |

| Smoke Vents (AOVs) | Vents that open automatically in the case of fire to remove smoke from escape routes | Every 6 months |

| Sprinkler System | Every 12 months | |

| Standalone Smoke Alarm | Smoke detectors which are powered from the mains and interconnected. So if one goes off, all go off. Located in communal areas only | Every 12 months |

| Warden Call | Hard wired warden call system | Every 12 months |

| Wet Riser | Similar to dry riser but has no water supply | Every 12 months |

Items that are highlighted bold are mandatory requirements for HMO properties. Items that are not bold are depending on the design of the building and the use and clientele. It is important to understand that the private rental sector not only supplies accommodation for the general public but also care and support services for residents with vulnerabilities and so additional safety measures may be required in order to comply with building and HMO regulations. The items listed in bold in Table 4 are generally what would be found in a non-care residential property.

The cost of servicing and maintenance will vary depending on the region and contractor. It is worth noting that service charges can be applied to tenancies in order to cover servicing, maintenance and new installation costs but this will need to fall in line with the relevant rent review legislations. Costs must be paid by the landlord who then has the right to service charge after.

2.7 Literature Review Summary

This literature review critically analysed 5 main subject areas pertaining to the current impacts that the private rental sector face with adhering to HMO legislation. The purpose of the literature review was to view how economic trends and legislation has influenced the investment into the private rental sector, in particular towards HMO’s and understand how these changes have reformed and potentially impacted investment into the market.

It is clear that the increase in population and decrease in owner-occupiers forms a gap for the private rental market to serve, however the impacts of HMO legislation and the requirements to form compliant HMO’s has not assured potential investors that the investment is worth the risk and so, the market is not growing as anticipated.

It is evident from the figures provided in the HHSRS assessment completed in 2016/2017 that the numbers of non-compliant HMOs are still very high, therefore causing health and safety risks towards tenants. It is also clear that the depth of the legislation requirements and potential costs and lack of support for landlords is supporting the number of non-compliant HMO’s. In conclusion, although the HMO legislation has been forced to help rise the standards of living, in fact, the complexity of the legislation has caused landlords to either not invest or turn a blind eye towards the requirements.

Cite This Work

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing stye below:

Related Services

View allRelated Content

All TagsContent relating to: "Social Policy"

Social Policy is policy set out by the Government, related to the quality of life and welfare of people. Social Policy includes guidelines and legislation, with policies created for housing, education, health, and other relevant areas of life.

Related Articles

DMCA / Removal Request

If you are the original writer of this literature review and no longer wish to have your work published on the UKDiss.com website then please: