Expanding Pre-hospital Healthcare: Chronic Pain Management

Info: 8679 words (35 pages) Example Dissertation Proposal

Published: 31st Jan 2022

Tagged: Healthcare

Table of Contents

Click to expand Table of Contents

1.0 Summary

2.0 Background

2.1 Introduction

2.2 Literature Review

2.3 Rationale

3.0 Aims and Objectives

3.1 The Question

3.2 Aims and Objectives

4.0 Research Design, Methodology and Method of Analysis

4.1 Methodology

4.2 Setting

4.3 Sample

4.4 Data analysis

5.0 Ethical Considerations and issues pertaining Research Governance

6.0 Dissemination of findings

7.0 Scope

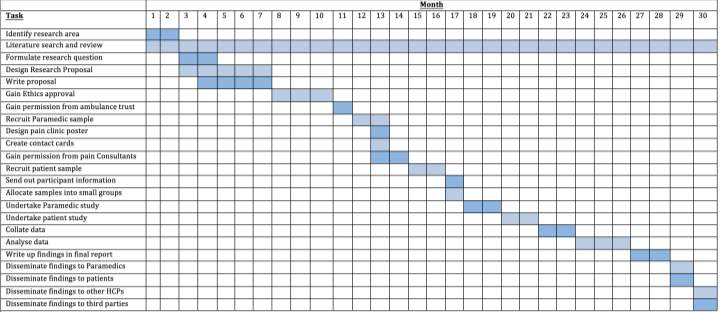

7.1 Gantt Chart

8.0 Budget & Resources

9.0 References

Appendix A: Consent Form

Appendix B: Letter to Pain Clinic

Appendix C: Poster for Pain Clinic

Appendix D: Contact Card

Appendix E: Email to Team Leaders

Appendix F: Paramedic Interview

Appendix G: Patient Interview

1.0 SUMMARY

Current research into chronic pain management has a key focus on currently available analgesics and their efficacies on chronic pain conditions. The proposed study aims to identify any gaps in protocol for the management of chronic pain in the pre-hospital setting.

This could lead to changes in the way healthcare professionals in this environment triage and manage patients presenting with diagnosed chronic pain conditions. The study will involve investigating how chronic pain is currently assessed, managed and moderated in paramedic practice, focusing on techniques employed in pain management.

The proposed study will involve a purposive sampling of (n=50) paramedics from various ambulance services in the UK, and purposive sampling of (n=50) chronic pain illness patients. Semi-structured interviews have been chosen as the most reliable means of data collection, wherein the participants will be assigned identification numbers for confidentiality purposes. The interviews will be tape recorded, transcribed, and then analysed by external expert analysts for non bias and posterity, using a content analysis framework.

This study will compare and contrast results given by HCPs versus results from patients and highlight any discrepancies. Bridging this gap could then lead to better patient care for chronic pain illness sufferers in the pre-hospital setting.

2.0 BACKGROUND

2.1 Introduction

Pain can be defined as ‘An unpleasant, subjective, sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage or described in terms of such damage’ (International Association for the Study of Pain, 1979).

In the UK, Paramedic practice has always been at the forefront of emergency care. Previously, hospital admission was inevitable for most, if not all, patients. Now, however, with much research and training, paramedics have the ability and scope of practice to assess a patient on scene, manage and treat them, and arrange to discharge the patient, or refer to an alternative care pathway (DoH, 2005).

Pain assessment and management by Paramedics combines accurate history taking, physical examination and underlying pathophysiological knowledge, in order to recognize clinical patterns in a patient (Aehlert & Vroman, 2011). It is gaps in this knowledge that this study could ultimately improve for Paramedics.

A key challenge posed is the efficient management of chronic pain, which is well established as being of greater difficulty than the more common presentation to emergency services of purely acute pain (Jones and Machen 2003, p.168). Paramedics will come across patients with chronic pain in the form of historic injury, degenerative illnesses such as osteoarthritis, as well as malignancy.

In other incidences, they are faced with more challenging situations such as when they are dealing with patients for whom pain may not come from obvious physical illness, including that of a neuropathic nature (Bigham et al., 2013, p.369). When a paramedic attends such patients, they are faced with the challenge of having to care for their complex pain firsthand before they reach hospital, another care pathway, or are able to be discharged on scene.

Due to the challenges patients with existing chronic pain conditions present, compared to the more common acute pain that paramedics are more likely to see, there is a need for a careful examination of the aspects of pain management in Paramedic practice in the UK (Lord, 2004, p. 50).

2.2 Literature Review

Chronic pain is a commonly used term for pain which persists over a course of time. It may originate, for example, from an injury or surgery, continuing long after the normal acute phase. It can be associated with many illnesses, such as degenerative illness, and malignancy.

The International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) (2011) emphasizes the importance of the need for Health Care Professionals to have an understanding of chronic pain. They expand upon the more common understanding of chronic pain, asserting that the nature, symptoms and characteristics of the pain are key features, and not only the timescale of the suffering. They state that it presents ‘slightly differently as a persistent pain that is not amenable, as a rule, to treatments based upon specific remedies, or to the routine methods of pain control such as nonnarcotic analgesics.’ These chronic pain illnesses have an underlying continuous pain, that can then develop acute ‘flare ups’, which can be very difficult for the patient to manage themselves.

Acute flare-ups of chronic pain conditions are not thought of as an emergency in pre-hospital medicine, however patients are still calling 999 and/or the NHS 111 advice line due to their respective illness/condition. We are also seeing that most 999 patients are no longer critically ill, presenting paramedics with the added pressure of treating and referring patients (Petter & Armitage, 2013). The Department of Health (DoH) recommended that Paramedics be armed with a wider range of competencies to support their ‘treat and refer’ system of patients (DoH, 2005), and this includes the knowledge and abilities to advise patients on best care alternatives. Alternative referral pathways to more appropriate services were introduced over the last decade via the introduction of ‘treat and refer’ guidelines (Fitzpatrick, 2013). These were produced in order to enable ambulance clinicians to treat and discharge the patient at home, and refer them to appropriate care pathways. Alternative Care Pathways therefore result in avoiding unnecessary admittance to emergency departments.

A study by the American Academy of Pain Medicine (2006) of 303 chronic pain illness sufferers in America revealed that more than half of the participants felt they had ‘little or no control over their pain’, with the majority experiencing an acute flare up of their chronic pain daily; having a severe impact on their quality of life and general well being. Though this study was not conducted in the UK, it was able to demonstrate the extent to which chronic pain can influence a patients overall wellbeing, and thus can be used to recognize similarities with UK patients.

According to Buhrman et al. (2011), the assessment and management of pain is crucial to the foundation of pre-hospital health care. Paramedics are, in this regard, expected to possess effective assessment strategies within their scope of practice to be able to detect any instance of pain in a patient. Current research explores factors undermining analgesics issuance (Lord et al., 2009, p.527). A key underlying factor demonstrated as a reason for failure of analgesic administration is that sometimes patients fail to admit that they are in a lot of pain due to factors such as age, cognitive impairment or ignorance (Young et al., 2006, p.417). Practical assessment, therefore, demands that the sphere of paramedic practice has clear clinical guidelines on handling pain (Bigham et al., 2013, p.369). Such protocols arm the paramedics with the right kind of tools with which they can identify and manage such incidences efficiently.

Assessment of chronic pain requires effective strategies to evaluate patients, so that a resolution may be found in due course. Several analytical perspectives have highlighted the need for further research on the issue of management of chronic pain complications in patients. Notably, paramedics are core to the management of chronic (and acute) pain each time they are dispatched to an accident or otherwise. Most incidences of pain require acute reasoning and quick judgment calls to be made on account of the health of the patient (Lord and Parsell, 2003, p.356). Paramedics are only able to achieve this by effectively adopting the right kind of strategies.

Paramedics are responsible for ensuring patient care before admittance to hospital, another referral pathway, or discharged back to their own care. Current practices routinely used by non-emergency health care professionals (HCPs) such as acupuncture and reflexology, among other alternative techniques are among the few procedures through which chronic pain has been proven to be improved (French et al., 2006, p.75), however these practices are not currently in a Paramedics remit. Despite this, there is a variety of ways through which the pain can be relieved while the patient is in the care of Paramedics. Some of them may be traditional, while others are mostly modernized.

The traditional management, on the one hand, may involve techniques such as the use of massage. For instance, in cases where a patient is complaining of back pains, a paramedic may opt to encourage a relative of the patient to massage the affected area; a technique able to be used in the safety of their own home. This practice, along with administering the analgesic drugs, can be used in a bid to maximize the efficacy of the pain medication (Siriwardena et al., 2010, p.1272).

Paramedics have practice guidelines for the management of acute pain, and these may be able to be adapted to care for patients with acute exacerbation of chronic pain. The JRCALC pocketbook, which the majority of Paramedics carry whilst on a front line shift outlines a stepwise approach to pain, adopting the McCaffery, M. and Pasero, C. (1999). 0–10 Numeric Pain Rating Scale. This is targeted mainly for use by adults, with appropriate analgesia to be offered for each numerical value.

The paramedic’s perspective is core to determining a patient’s experience of pain. The issuance of analgesia is thus dependent on the assessment performed by the paramedic. A common obstacle is the paramedic’s perception of a patient’s pain (Figgis et al., 2010, p.153). It is not uncommon to find cases whereby a paramedic has withheld analgesics from the patient after incorrectly judging that the patient is exaggerating or falsifying their pain when, in fact, they are in dire need of analgesia. Such incidences need to be stemmed from paramedic practice, and the aspects of administration and withholding of analgesia in the pre-hospital setting need to be determined by accurate assessment of the patient’s pain state (Chambers and Guly, 1993, p.189).

Recent research has revealed that some paramedics have fallen short of professionalism when it comes to administering analgesic drugs. Some paramedics have been demonstrated to lack the capability to effectively evaluate a patient’s condition, resulting in the making of wrong executive calls (Figgis et al., 2010, p.153). Such incidences where paramedics fail to identify the chronic illness of the patient create a scenario where patients run the risk of succumbing to acute pains. Chronic pain requires critical examination, as acute flare ups can pose potentially unbearable consequences to the patients (Ball, 2005, p.899). Chronic pain brought about by degenerative diseases, comorbid or otherwise, can be very harmful to the psychological well-being of the patient.

Over time, the issue of managing chronic pain by Paramedics has been highlighted as often being low priority and hence, is an issue deserving of new study (Jones and Machen 2003, p.168). Adult patients, as the most affected people with chronic pain, are faced with particular challenges. Advancing age has been categorically revealed as one of the major causes leading to the development of degenerative illness such as osteoarthritis. Paramedics are expected to portray professionalism when they address such issues (Hirsh et al., 2014, p.553). A paramedic is expected to discretely identify and appreciate the type of pain experienced by the patient (Lord et al., 2009, p.527), after a series of quick assessments (Lord and Parsell, 2003, p.356). Successful assessment implies that a paramedic knows best how to manage the said condition.

Studies reveal that a good number of Paramedics lack the capability to determine if a patient is in pain, as well as to administer the right dosage of analgesia (Ruan et al., 2010, p.339). For instance, how adults respond to pain is not the same way that younger people will react to pain.

Paramedic practice is driven by key factors, including current evidence based practice, which play a crucial part in the decision making process for the administration of analgesia (Jones and Machen 2003, p.168). Making the right decision about when to administer pain relief in the pre-hospital setting is of paramount importance, as studies have shown that decision-making should be critical and precise in the event of administration of analgesia, with pain management encouraged early in proceedings (Chambers and Guly, 1993, p.189). In paramedic practice, the element of time is critical to the safety of the patient, as it determines the alleviation of pain, thereby assuring the patient of their well-being; including their psychological health. The patient’s psychological well-being is vital, as it acts as the cornerstone of the patient’s nerve response, (Wuhrman and Cooney, 2011).

It is important to consider how a Paramedics attitudes and inclinations might either directly or indirectly influence their practice. By most accounts Paramedics are deemed to have the right kind of attitudes towards their patients (Weber et al., 2012, p.1394). Thus far, the attitudes of Paramedics determine just how successful the patient interaction is. some studies, including those done by Heins et al., (2006), and Pletcher, Kertesz, Kohn, & Gonzales (2008) have indicated that Health Care Professionals have at some time decided not to administer analgesics to a patient of a different ethnic background, and if such a situation happens, the health of the patient is jeopardized. This study was performed over 13 years, improving the validity of the study, due to the amount of patients seen over that time frame, and the fact it is a retrospective study removes an element of bias.

From the analysis of previous research, it is clear that paramedics are faced with the challenge of understanding the behaviors of their patients, by determining if indeed their pain is real or exaggerated (Jones and Machen 2003, p.168). By this token of logic, the element of psychological understanding is important. A paramedic should be equipped with the right kind of behavioral and psychological knowledge in order to determine when the patient is in pain; so that analgesia should be administered (Kanowitz et al., 2006, p.5). Behavioral psychology, if applied well, has the potential to enable the paramedic to decide when to initiate medical care to the patient. By understanding the behaviors of the patients, it is much easier for a Paramedic to form meaningful decisions based on the timelines for analgesia administration (Rupp and Delaney, 2004, p. 497). Interpreting behavior changes in patients can further help the Paramedic assess and gauge the levels of pain their patient is in, so as not to rely on the sole use of the verbal 1 to 10 scale (Middleton et al., 2010, p.442). Such an aspect implies that the Paramedic becomes more efficient in delivering pre-hospital health care to the chronic pain patient.

Through a close examination of the patient’s behavioral changes and perceived response to pain, the Paramedic becomes confident in whatever mechanism he/she may adopt in the alleviation of the suffering (Jones and Machen 2003, p.168). It is crucial for the Paramedic to recognise that the patient could experience behaviour changes, and even mental illness, as a consequence of the ongoing challenges of living with a chronic pain illness. This understanding would be beneficial to the patient as it aids in establishing trust that the Paramedic is treating them with a holistic approach. The Paramedic is accounting for their mental wellbeing, as well as their physical health. (Lamba et al., 2013, p.516). The patient feels attended to by the paramedic and thus may become more forthcoming about their condition, as opposed to a situation where the patient feels unattended to; due to the misconstrued perceptions of the patient’s psychology.

Recent research has revealed that the field of study analyzing pre-hospital health care provided by Paramedics has been neglected. As such, newer, in-depth research is of great importance, due to the number of patients a Paramedic can have an impact upon. It is the field that often first diagnoses a patient (Berben et al., 2012, p.1399). The incidences of chronic pain have been increasing in the course of time, but unfortunately, less and less intervention has been accorded to this area of urgency. Over time, unfortunately, there have been well meaning but poorly designed services meant to give a patient’s pain a higher priority in assessment. The underlying reasons for their failure are due to decreasing or no research into this area.

2.3 Rationale

The rationale for undertaking this study is highlighted by the gaps in research pertaining to paramedic practice on the management of chronic pain. The study aims to demystify the challenges experienced by UK paramedics surrounding the efficient management of chronic pain. The study aims present full results, which hold answers to the existing problems presently in the sphere of Paramedic practice.

This study also seeks to give Paramedics insight into the unbiased views of patients who suffer from chronic pain illness, and how they feel their management could be improved in the pre-hospital setting.

A review of the literature above supports the surmise that an investigation of HCP and patient views will positively reinforce and help develop clinical practice. This will be done by outlining weaknesses in assessment and management, which may not be acknowledged by Paramedic investigation alone, but will be reinforced by the views of patients involved in this care group.

3.0 AIMS AND OBJECTIVES

3.1 Research Question

How can the management of patients with chronic pain be improved in Paramedic Practice?

The proposed research seeks to come up with effective measures for the improvement of management of chronic pain in paramedic practice. The future studies in this respect seek to discover new avenues for which the paramedic practice can be improved.

3.2 Aims/Objectives

- To report findings which could potentially provide a suitable ground for the improvement in the management of chronic pain, in relation to pre-hospital health care.

- To address the problems experienced in paramedic practice on the management of chronic pain, such as the lack of knowledge in the alternative methods of pain management.

4.0 Research Design

The research design the researcher will be using for this proposal will explore the question, and achieve its aims and objectives.

The literature above reinforces the need to improve on the practice of assessment and management of patients having either an acute flare up of their chronic pain illness, and/or are finding themselves unable to cope with the impact their condition has on their activities of daily living, and their mental well-being. Evidence shows patients want to feel safe and involved in decisions surrounding their care, so ensuring Paramedics understand and recognize chronic pain illness is vital in achieving best care for this group of service users.

This research proposal reports qualitative research, undertaken in a bid to facilitate a better understanding of the paramedics’ standpoints about the status of pre-hospital health care, and the patients’ viewpoint. Qualitative research is appropriate for this study to enable the researcher to learn more about human motivation, perceptions and behavior (Williams, 2012). As such, this played a trans-disciplinary study; the objectives of which are to develop and/or improve while conducting an articulate examination about the paramedic participation in the research about pre-hospital medical care for chronic pain. This study involves one to one interviews with ten groups of five participants focus group of UK paramedics. This is in a bid to understand their viewpoints regarding their participation in pre-hospital health care, with respect to assessment and management of chronic pain illnesses. It also involves ten focus groups of five adult chronic pain sufferers who are currently diagnosed, and under the care of a pain specialist. This will report a phenomenology approach, as will allow for both Paramedics and patients alike to reflect on previous events, and allows the researcher to study their experiences.

Data collection and recruitment were designed to tolerate social disparities, as well as, work practices, all for the convenience of the respondents. The findings of the research are all covered by the design. Semi-structured questions will be used for the interview. Numbers will be used in place of names for confidentiality. This proposal elicits an opinion-based response from the paramedics and patients, since they gave feedbacks based on their individual perceptions. The study design was developed jointly by all UK-based analysts.

4.1 Methodology

The technique used in this research proposal involved a sampling of fifty paramedics from a UK ambulance service, where this service serves a considerably large and diverse population. The researcher will also use purposive sampling for fifty patients, in an ‘opt in’ basis. The researcher will recruit patients using posters within pain clinics; put up with consent from the doctors running these clinics. Current research which precluded selective recruitment techniques wherein the participants were directly selected by the researcher. A qualitative study used focus groups to explore Paramedics’ attitudes towards chronic pain patients and their care, and equally their counterpart of focus groups with patient currently being treated at UK pain clinics for the same purposes.

Furthermore, the approval of ethical standards will be pursued to the latter. Written permissions will be obtained to enable the analysts willfully interview the paramedics. The paramedics will be, in turn, prompted to sign an agreement form. A semi-structured mode of the interview was preferably chosen as the most befitting form of data collection suitable for the research. The semi-structured interviews were preferred mostly because of the inherent element of confidentiality. The participants will be assigned identification numbers, in keeping with confidentiality.

Regardless of the topic guide, the conversation trajectory will be allowed to diverge; thus allowing the participants to relate their opinions about their experiences. This research involves the usage of nine open-ended questions. The paramedics will be asked to explain the factors which, according to them influenced the pain of the patients. They were also asked how they ascertained if the patients’ claims as honest or otherwise. The paramedics described their pain identification, as well as, assessment criteria and the types of illnesses for which they issued analgesia. The research also covered the factors which dictated the paramedics’ issuance of analgesia to the patients. Lastly, their perceptions regarding the administration of analgesia to the patients without pain were also discussed.

The topic guide was subjected to a thorough review by a proficient analyst. The data collected from the study will be recorded on tapes and then transcribed. After the transcription, the data will undergo a thorough analysis based on the fourteen stage framework (Pope et al., 2000, p.114). The proposed method of analysis involved the use of a strategy about thematic content analysis schematic (Vaismoradi et al., 2013, p.401). After transcription, the data will further analyzed by selectively partitioning the data as a result of the thematic concerns as stated in the findings section below.

4.2 Setting

Potential Paramedic participants will be found via email. The researcher will email Team Leaders from across the NHS service chosen for this study, where they, in turn, will recruit Paramedics willing to opt in and take part in the research. The incentive to participate would be the ability to use this as an opportunity to further their learning and education in respect to chronic pain illness, and also include it in their CPD portfolio.

Potential patient participants will be found via pain clinics. With permission from the consultants running the clinic the researcher will put up posters directed to appeal to the patients within the clinic. This will ensure the patients do not feel intimidated or coerced to join the study; but will opt in of their own volition.

The patient setting for this study must be somewhere that the participants feel comfortable, potentially familiar surroundings, whilst still ensuring accurate results, Roberts & Priest (2010). It is for this reason that the patient participants interviews and focus groups will be held at their own local pain clinic. The Paramedic participants will

4.3 Sample

Paramedic group: Registered Paramedics. Preferably a mixture of graduate Paramedics and non University Paramedics, of all ages, to encourage a diverse population. All should be familiar with treating chronic pain patients.

Patient group: Over eighteens only, with diagnosed chronic pain illnesses currently being treated in a pain clinic. Preferably those who have had contact with pre hospital Paramedic care.

4.4 Data Analysis

There are two separate pieces of data being collected for this study; the Paramedic and patient interviews, and ideas formulated and discussed during the focus groups. The analysis of this data aims to draw out patterns from concepts and insights, and use these patterns to ultimately determine if there is, in fact, gaps within the assessment and management of chronic pain illness patients. By comparing and contrasting the responses from the Paramedics with the responses from the patients these gaps, if any, may become evident.

The Framework Method of analysis will be used for this piece of qualitative research, so another more experienced researcher will be brought in to lead the project, due to the inexperience of the writer, and the desire for the project to succeed and produce repeatable results (Gale et al 2013).

The interviews will be transcribed verbatim, then the researchers can become familiar with the interviews, and the meaning behind responses given. The data will then be coded separately by each researcher (Gale et al 2013), in order to classify the data and allow for systematic comparison.

Next, the researchers will develop and apply a working analytical framework. This data will then be charted into a matrix, allowing for interpretation. Characteristics or differences between the two sets of data will then allow for a theory to be developed (Charmaz K. 2006).

5.0 Ethical considerations and issues pertaining to Research Governance

Once the research proposal has been fully designed, an application will be submitted to the National Health Service Health Research Authority (HRA) for approval to undertake research in England (NHSHRA, 2016).

This research proposal has been designed in accordance with the Health and Care Professions Council (HCPC) (2016) Standards of Conduct, Performance and Ethics, to ensure the participants are protected whilst assisting with this study.

Ethics are the set norms and or standards critically defined to aid in the determination of right deeds from wrong. Ethical standards are core to setting acceptable conducts apart from the unacceptable ones. The ethics form the basis of collaboration, as well as teamwork, which is essential to the success of the research (Walker, 2007, P.39). Ethical conduct, in a way, ensures certainty in the retrieval of accurate data, which coincides with the public’s desires. The considerations employed by ethical standards do more in the way of assuring quality from varied angles (Tracy, 2010, p.842). Nonetheless, it goes without saying that such considerations have the potential to breed respect and nurture accountability among the researchers, thus promoting a culture more founded on credibility than a fallacy.

Conceivably, the public domain seeks to be assured that the analysts retrieved their data through the right channels. They want to be sure that the proper guidelines were followed to the letter in the course of retrieving the data. Thus far, ethics are fundamental to any research conducted for any particular purpose.

Several research affiliate groups have come up with stringent policies which are aimed towards the achievement of moderation and discipline in the conduction of research (Walker, 2007, P.39). The policies are meant to ensure that the research is conducted and or operated along the strict lines of austerity while upholding the fundamental values at the same time. Such considerations are crucial to the pursuit of credible data retrieval (Munhall, 1988, p.157). These policies provide a framework, which if adhered to, should aid in the integrity of conducting the research. It reinforces the importance of, for example, honesty and timeliness among other qualities.

Regardless of the legal policies set by the agencies dealing with surveys, the researcher is still faced with many challenges which demand the power of choice from the analyst. The aspect of decision making, therefore, becomes more critical in the event of data retrieval. For instance, this proposal, focusing majorly on the paramedics’ perceptions about their participation in the pre-hospital management of chronic pain, requires due diligence on the part of the analyst since the paramedics’ perceptions are unlikely to be unanimous but rather diverse (Walsh et al., 2013, p.82).

Such policies which attempt to lessen or eradicate the element of bias will be used during the conduction of the survey. The findings of the research in this regard will be founded by credibility (Munhall, 1988, p.157). No aspects of misconduct will be allowed in the course of the study.

Most studies to date utilize the regulations employed by the International Research Board, (IRB) which is keen on safeguarding human rights. Human subjects have to be granted certain assurances regarding their safety e.g. use of the Data Protection Act (1998) (Tracy, 2010, p.841). The legal implications and the potential risks are clearly explained by the researcher to the participants before their involvement in the survey, ensuring informed consent is obtained.

Integrity, which is an element of ethics, is crucial to the researcher since it is a key aspect which dictates the validity of the results obtained from the survey.. Researchers are bound by moral laws, which bar them from falsifying results in the course of their studies, increasing their validity. Furthermore, the same goes for the study subjects; the paramedics and chronic pain patients, who will play their role in increasing the validity and reliability of the study by hopefully providing truthful responses.

Biased results would provide no grounds for the development of potential changes to paramedic practice regarding chronic pain management because the data obtained would be unreliable and invalid. Good ethical considerations aid in the procurement of valid results, since the all participants should provide real and legitimate response.

Ethical considerations lay the necessary foundation for giving a study reliability and validity. Reliability is an essential concept in the retrieval of results from the field, which in this case, is the feedback from the selected paramedics and chronic pain patients about their involvement in pre-hospital health care.

6.0 Dissemination of Findings

All participants in the research will be given a report of the findings, and will be encouraged to comment on them.

As well as the above, dissemination of the results will take place by three methods:

- A report will be formulated to distribute throughout the Ambulance Trust used in this proposal, which can then be further distributed to all ambulance services in the UK

- A report will be formulated to distribute to the Consultants at the pain clinic used in this proposal, which can be further distributed to other Pain clinics across the UK, with an aim to inform their patients of any findings.

- Publishing papers in specialist and general, national and international journals.

7.0 Scope

This proposal will be carried out in a time span of 30 months, allowing for appropriate timescales for various tasks. The timeline was majorly designed for the retrieval of more conclusive findings in the long run.

7.1 Gantt Chart

8.0 Budget/Resources

Overall costs of this study. Information gained from independent sources.

| Resource | Price | Quantity | Total |

| Photocopying | £0.05 per sheet | (31+10) X 100 | £205 |

| Printing | £0.15 per sheet | 100 sheets | £15 |

| Contact card | £14.39 per hundred | 100 | £1,439 |

| Posting | £0.04 per envelope

£0.61 per stamp |

100 participants

100 |

£4.00

£61.00 |

| Setting | £30 per day refreshments | 40 days | £1,200 |

| Statistician | £50 per hour | 30 hours | £1,500 |

| Researcher | £20 per hour

£0 (own time) |

2,340 | £46,800

£0 |

| Travel Expenditure | £15 per person | 100 | £1500 |

| Personal Expenditure | No charge | X | £0 |

| Total | X | X | £52,724 |

This proposal constitutes a budgetary allocation to this effect:

- One hundred interviews in England all by me.

- Record of 100 interviews: 100 x 30 minutes per interview.

- 10 separate focus groups; 5 Paramedic focus groups and 5 patient focus groups.

- Price of a second researcher to lead.

9.0 References

Aehlert, B., & Vroman, R. (2011). Paramedic Practice Today: Above and Beyond (revised ed. Vol. Volume 2): Jones and Bartlett Publishers 2011

American Academy of Pain Medicine (2006). Voices of Chronic Pain Survey. (American Pain Foundation)

Ball, L., 2005. Setting the scene for the paramedic in primary care: a review of the literature. Emergency Medicine Journal, 22(12), pp.896-900.

Bigham, B.L., Kennedy, S.M., Drennan, I. and Morrison, L.J., 2013. Expanding paramedic scope of practice in the community: a systematic review of the literature. Prehospital Emergency Care, 17(3), pp.361-372.

Bledsoe, B.E., Porter, R.S., Cherry, R.A. and Armacost, M.R., 2006. Paramedic Care, Principles & Practice. Prehospital Emergency Care, 10(4), pp.522-523.

Buhrman, M., Nilsson-Ihrfelt, E., Jannert, M., Ström, L. and Andersson, G., 2011. Guided internet-based cognitive behavioural treatment for chronic back pain reduces pain catastrophizing: a randomized controlled trial. Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine, 43(6), pp.500-505.

Chambers, J. A., and Guly, H. R. “The need for better pre-hospital analgesia.” Archives of emergency medicine 10.3 (1993): 187-192.

Charmaz K. (2006) Constructing grounded theory: a practical guide through qualitative analysis. London: Sage.

Department of Health. (2005). Taking healthcare to the patient: Transforming NHS ambulance services UK. DoH.

Figgis, K., Slevin, O. and Cunningham, J.B., 2010. Investigation of paramedics’ compliance with clinical practice guidelines for the management of chest pain. Emergency Medicine Journal, 27(2), pp.151-155.

French, S.C., Salama, N.P., Baqai, S., Raslavicus, S., Ramaker, J. and Chan, S.B., 2006. Effects of an educational intervention on prehospital pain management. Prehospital Emergency Care, 10(1), pp.71-76.

Gale NK, Heath G, Cameron E, Rashid S, Redwood S. (2013) Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research. BMC Med Res Methodol

Gausche, M., Lewis, R.J., Stratton, S.J., Haynes, B.E., Gunter, C.S., Goodrich, S.M., Poore, P.D., McCollough, M.D., Henderson, D.P., Pratt, F.D. and Seidel, J.S., 2000. Effect of out-of-hospital pediatric endotracheal intubation on survival and neurological outcome: a controlled clinical trial. Jama, 283(6), pp.783-790.

Heins, J. K., Heins, A., Grammas, M., Costello, M., Huang, K., & Mishra, S. (2006). Disparities in analgesia and opioid prescribing practices for patients with musculoskeletal pain in the emergency department. Journal of Emergency Nursing, 32(3), 219–224.

Hennes, H., Kim, M.K. and Pirrallo, R.G., 2005. Prehospital Pain Management: A Comparison of Providers Perceptions and Practices. Prehospital Emergency Care, 9(1), pp.32-39.

Hirsh, A.T., Hollingshead, N.A., Matthias, M.S., Bair, M.J. and Kroenke, K., 2014. The influence of patient sex, provider sex, and sexist attitudes on pain treatment decisions. The journal of pain, 15(5), pp.551-559.

International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) (2011) Classification of Chronic Pain, Second Edition (Revised) Descriptions of Chronic Pain Syndromes and Definitions of Pain Terms

Jones, G.E. and Machen, I., 2003. Pre-hospital pain management: the paramedics’ perspective. Accident and Emergency Nursing, 11(3), pp.166-172.

Kanowitz, A., Dunn, T.M., Kanowitz, E.M., Dunn, W.W. and VanBuskirk, K., 2006. Safety andEffectiveness of Fentanyl Administration for Prehospital Pain Management. Prehospital Emergency Care, 10(1), pp.1-7.

Lamba, S., Schmidt, T.A., Chan, G.K., Todd, K.H., Grudzen, C.R., Weissman, D.E. and Quest, T.E., 2013. Integrating palliative care in the out-of-hospital setting: four things to jump-start an EMS-palliative care initiative. Prehospital Emergency Care, 17(4), pp.511-520.

Layman Young, J., Horton, F.M. and Davidhizar, R., 2006. Nursing attitudes and beliefs in pain assessment and management. Journal of advanced nursing, 53(4), pp.412-421.

Lord, B., Cui, J. and Kelly, A.M., 2009. The impact of patient sex on paramedic pain management in the prehospital setting. The American journal of emergency medicine, 27(5), pp.525-529.

Lord, B.A. and Parsell, B., 2003. Measurement of pain in the prehospital setting using a visual analogue scale. Prehospital and Disaster Medicine, 18(04), pp.353-358.

Lord, B., 2004. The Paramedic’s Role in Pain Management: A vital component in the continuum of patient care. AJN The American Journal of Nursing, 104(11), pp.50-53.

McCaffery, M. and Pasero, C. (1999). Pain: Clinical Manual, Page 16. Printed in St. Louis,

Middleton, P.M., Simpson, P.M., Sinclair, G., Dobbins, T.A., Math, B. and Bendall, J.C., 2010. Effectiveness of morphine, fentanyl, and methoxyflurane in the prehospital setting. Prehospital Emergency Care, 14(4), pp.439-447.

Munhall, P.L., 1988. Ethical considerations in qualitative research. Western Journal of Nursing Research, 10(2), pp.150-162.

National Health Service Health Research Authority (2016). HRA Approval: the new process for the NHS in England. Version 4.0: NHS. Updated 30th March 2016.

Petter, J & Armitage, E. (2013). Raising educational standards for the paramedic profession. Journal of Paramedic Practice, 4(4)

Pletcher, M. J., Kertesz, S. G., Kohn, M. A., & Gonzales, R. (2008). Trends in opioid prescribing by race/ethnicity for patients seeking care in US emergency departments. Journal of the American Medical Association, 299(1), 70–78.

Pope, C., Ziebland, S. and Mays, N., 2000. Analysing qualitative data. British medical journal, 320(7227), p.114.

Roberts, P., & Priest, H. (2010). Healthcare Research: A Handbook for Students and Practitioners (Vol. 1). Chichester: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd

Ruan, X., Couch, J.P., Liu, H., Shah, R.V., Wang, F. and Chiravuri, S., 2010. Respiratory failure following delayed intrathecal morphine pump refill: a valuable, but costly lesson. Pain Physician, 13(4), pp.337-41.

Rupp, T. and Delaney, K.A., 2004. Inadequate analgesia in emergency medicine. Annals of emergency medicine, 43(4), pp.494-503.

Siriwardena, A.N., Shaw, D. and Bouliotis, G., 2010. Exploratory cross‐sectional study of factors associated with pre‐hospital management of pain. Journal of evaluation in clinical practice, 16(6), pp.1269-1275.

Tracy, S.J., 2010. Qualitative quality: Eight “big-tent” criteria for excellent qualitative research. Qualitative inquiry, 16(10), pp.837-851.

Vaismoradi, M., Turunen, H. and Bondas, T., 2013. Content analysis and thematic analysis: Implications for conducting a qualitative descriptive study. Nursing & health sciences, 15(3), pp.398-405.

Walker, W., 2007. Ethical considerations in phenomenological research. Nurse researcher, 14(3), pp.36-45.

Walsh, B., Cone, D.C., Meyer, E.M. and Larkin, G.L., 2013. Paramedic attitudes regarding prehospital analgesia. Prehospital Emergency Care, 17(1), pp.78-87.

Weber, A., Dwyer, T. and Mummery, K., 2012. Morphine administration by Paramedics: An application of the Theory of Planned Behaviour. Injury, 43(9), pp.1393-1396.

Williams, J. (2012) Qualitative research in paramedic practice: an overview. In Griffiths, P. and Mooney, G.P. (ed) The paramedic’s guide to research. Maidenhead; Open University Press.

Wuhrman, E. and Cooney, M. (2011) Advanced Practice Nursing. Acute Pain: Assessment and Treatment

Appendix List

Appendix A

CONSENT FORM

| Please Initial Box | |

|

1. |

|

|

2. am free to withdraw at any time, without giving reason. |

|

| 3. I agree to take part in the above study. | |

4. I agree to the use of any data collected being published. |

|

|

5. I have had the opportunity to ask any questions I have about my involvement in the study. |

|

Name of Participant Date Signature

Name of Researcher Date Signature

Appendix B

Letter to pain clinic

Dear __[Pain Clinic Consultants]__,

This particular study involves recruiting a number of your patients to take part in focus groups and one-to-one interviews with myself. The research will focus on identifying any current gaps in assessment and management of chronic pain illness patients by Paramedics in the pre-hospital setting, and aims to find ways of closing these gaps.

I would like your permission to use your premises to put up posters to recruit patients, and leave contact cards with my information on them. I would also like to use your premises to conduct the interviews and focus groups, as I understand it can be difficult for your patients to travel too far due to their pain. It also allows for the patients included in the study to feel relaxed in familiar surroundings.

Please don’t hesitate to get in touch for further information, I would be very keen to discuss my research with you,

Kind regards,

Name:

Email:

Contact Number:

Appendix C

Poster for pain clinic

Appendix D

Contact Card Design for Nurses Station

Appendix D

Email to TL’s

Dear __[Ambulance Complex]__ Team Leaders,

I am proposing to conduct research in the field of chronic pain in the pre-hospital setting. I am interested to explore Paramedics viewpoints in respect to how they assess and manage chronic pain illness patients.

This research project will require me to recruit 50 registered Paramedics from across the service. This research will report qualitative data, secured via interviews and small focus groups.

Please can I ask that you recruit Paramedics from your complex for this study? This research could ultimately gain results that improve the ways in which pre hospital clinicians assess and manage a chronic pain illness patient.

I am also writing to ask for your permission to use your grounds to conduct the interviews and focus groups, for ease of the Paramedics form your station.

If anyone wishes to obtain further information please do not hesitate to get in touch,

Kind regards,

Name:

Email:

Contact Number:

Appendix E

Paramedic Interview

- Do you feel you have a good understanding and foundation knowledge of chronic pain illnesses?

- What symptoms do you associate with a patient who is suffering from an acute flare up of their chronic pain?

- Are you aware of any gaps that may be present in current practice regarding chronic pain? If so, what are they?

- What is your current management strategy regarding assessing and treating a chronic pain illness patient, who is suffering from an acute flare up of their condition?

- Do you feel this practice needs improving upon?

- If so, what improvements do you feel could be made?

- How long do you take to apply analgesia to this patient group, if at all?

- Do you involve patients from this care group in decisions surrounding their treatment?

- If so, how do you involve them? If not, why?

- Are you comfortable that previous encounters with chronic pain illness patients have been managed appropriately?

Follow up questions will be asked as appropriate to each response.

Appendix F

Patient Interview

- Do you feel you have a good understanding and foundation knowledge of your chronic pain illnesses?

- Do you understand the current management of your own chronic pain?

- What symptoms do you experience when suffering from an acute flare up of your chronic pain?

- Have you ever had to call an ambulance due to the symptoms of your chronic pain?

- If so, what prompted you to call an ambulance? If not, why do you feel you have you not needed an ambulance?

- How did the ambulance staff assess you when they arrived?

- Did you feel involved in the decisions made surrounding your care?

- If so, how were you involved? If not, why were you not involved?

- How long did they take to apply pain relief to you, if at all?

- Had you already taken rescue pain relief before their arrival?

- If you were ever in need of calling an ambulance for your chronic pain illness [again], would there be any changes from previous encounters you would like to see? Were you happy with previous encounters? If no previous encounters with the Ambulance service, what involvement would you like to see in your case?

Follow up questions will be asked as appropriate to each response.

Cite This Work

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing stye below:

Related Services

View allRelated Content

All TagsContent relating to: "Healthcare"

Healthcare is defined as providing medical services in order to maintain or improve health through preventing, diagnosing, or treating diseases, illnesses or injuries.

Related Articles

DMCA / Removal Request

If you are the original writer of this dissertation proposal and no longer wish to have your work published on the UKDiss.com website then please:

I confirm that I have understood the information the researcher has given to me regarding the above study.

I confirm that I have understood the information the researcher has given to me regarding the above study.

I understand that my participation is voluntary and that I

I understand that my participation is voluntary and that I