Occupational Health and Safety Issues in Agriculture

Info: 7350 words (29 pages) Dissertation

Published: 9th Dec 2019

Tagged: Health and SafetyFarming

Contents

Section 2 Vehicles and Machinery

2.2 All-Terrain Vehicle (ATV) / Quad Bike

2.3 Machinery and power take off (PTO)

Section 4 Work Related Musculoskeletal Disorders (MSDs)

4.2 Theories of Musculoskeletal Injury Causation

4.2.1 Multivariate Interaction Theory

4.2.2 Differential Fatigue Theory

4.4 Risk Factors in Agriculture

Section 5 Higher Risk Categories

6.3. Potential Outcome of Stress – Depression and Suicide

Section 7 Accident Prevention Strategies

7.1 Occupational Health and Safety Legislation

7.2 Health and Safety Authority (HSA)

7.3 Farm Safety Partnership Advisory Committee

Agriculture — a hazardous industry

Section 1 Introduction

The Oxford English Dictionary defines agriculture as the science, occupation or practice of farming, including cultivation of the soil for the growing of crops and the rearing of animals to provide food, wool, and other products (“agriculture, n.”, 2018).

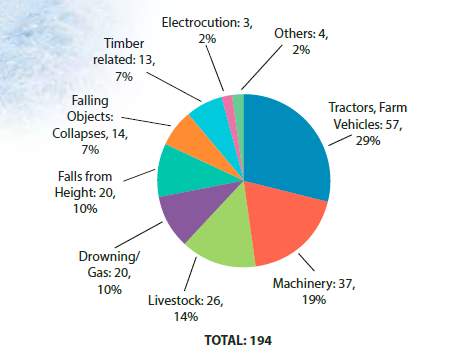

In Ireland, the agriculture sector has one of the highest rates of work-related injuries and fatalities even though only a small proportion of the workforce is employed there. In 2016 almost 73 percent of work related fatalities occurred in the sector. The rate of fatality was ten times higher than in all sectors, with agriculture at 21.3 per 100,000 workers and all sectors being 2.1 per 100,000 workers (Health and Safety Authority, 2017a). The Census 2016 found that agriculture accounted for only 4.6 percent of total employment, it also found the majority of farmers were self-employed (Government of Ireland, 2017). The causes of all fatal accidents in agriculture in Ireland 2006 – 2015 are shown in chart in Figure 1.

Figure 1 Causes of fatal accidents in agriculture in Ireland (2006-2015) (Health and Safety Authority, 2017b)

The Health and Safety Executive in Great Britain also report high rates of injury and fatalities in this sector, the worker fatality rate was 7.61 per 100,000 workers in 2016/17. This equates to around six times that in construction and 18 times that for all sectors (Health and Safety Executive, 2017). In 2014 14.3 percent of fatal accidents and 5.4 percent of non-fatal accidents at work in the EU-28, occurred in the agriculture, forestry and fishing sector (Eurostat, 2018).

This literature review is focused on the topics of vehicles and machinery, livestock, work related musculoskeletal disorders, groups that are in the higher risk categories on farms, stress and accident prevention strategies in agriculture.

Section 2 Vehicles and Machinery

Agriculture is dependent on the use of tractors, farm vehicles and machinery. They allow farmers to work with less effort, more efficiently and improved productivity. Statistics from the Health and Safety Authority (HSA) demonstration that for the period 2006 to 2015, there were 194 fatalities in the agricultural sector in Ireland, 29 percent of these were caused by tractors and farm vehicles and 19 percent by machinery (Health and Safety Authority, 2017b).

2.1 Tractors

In years gone by, most tractor fatalities worldwide were due to overturning (Day, 1999) (Pacific Northwest Agricultural Safety and Health Center, 2004) (Horsburgh, et al., 2001). Tractor overturn fatality rates are dropping due to increases in the use of rollover protection structures (ROPS). ROPS can be of various designs, they are roll bars or cabs provided to establish a protective zone for the tractor operator in the event of a tractor overturn. The tractor operator must also wear a seatbelt to keep them inside the protective zone during an overturn. When properly used ROPS can prevent almost all agricultural tractor rollover fatalities (Ayers, et al., 2018).

In Sweden the occurrence of fatal rollovers per 100 000 tractors per year was reduced from 17 to 0.3 after regulations were introduced requiring ROPS. There were also reductions in Norway, Finland, West Germany and New Zealand due to the introduction of similar regulations (Springfeldt, 1996).

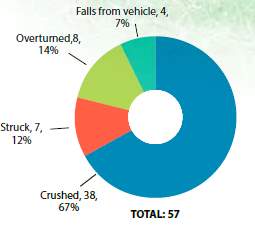

Being run over, hit or crushed by a tractor is also a frequent cause of death in agriculture (Rorat, et al., 2015). 79% of all deaths involving vehicles and farm machinery in Ireland between 20006 – 2015 were from being crushed (67%) or struck (12%) as seen in Figure 2. Poor planning, operator error, lack of training and inadequate maintenance of the vehicle or machine and poor operation of vehicles particularly when reversing was the main cause of these fatalities (Health and Safety Authority, 2017b).

Figure 2 Causes of fatal accidents involving tractors and vehicles (2006- 2015) (Health and Safety Authority, 2017b)

2.2 All-Terrain Vehicle (ATV) / Quad Bike

There is increasing unease in many countries regarding the number of serious injuries and fatalities related to ATVs /quad bikes. An ATV/ quad bike is defined as a vehicle with low-pressure tires, a straddle seat and handlebars for steering. A fatality is more likely to occur when an ATV rolls over or pins a driver underneath. Fatalities are also linked with injuries to the head, neck and chest (Shulruf & Balemi, 2010) (Grzebieta, et al., 2015) (Transport and Road Safety (TARS), 2017). The use of a helmet significantly decreases the likelihood of injury or fatality associated with ATV-related crashes (Bowman, et al., 2009).

In Ireland In the past 10 years (2008-2017) there were 12 quad bike fatalities. Although ROPS are available for quad bikes the Health and Safety Authority has not issued an instruction or recommendation in relation to the use of ROPS as they do not have sufficient information on its effectiveness (Health and Safety Authority, 2018a).

2.2.1 Further Research

Further research is required on the effectiveness of ROPS on quad bikes in Ireland.

2.3 Machinery and power take off (PTO)

PTO entanglement causes 11% of all fatal machinery accidents and many serious injuries. Most PTO accidents occur when clothing, hair and/or limbs are entangled in the rotating PTO shaft. Most of these accidents would be prevented with the use of a guard. In Ireland all PTO guards should comply with European Standard EN 12965 and bear the CE mark (Health and Safety Authority, 2017b). A recent study of farms in New York found that PTO guards were missing off 57% of PTO driveline implements (Sorensen, et al., 2017).

Section 3 Livestock

3.1 Handling and facilities

Animal encounters are a prominent cause of injuries and fatalities in the agriculture sector (Health and Safety Authority, 2017a) (Health and Safety Executive, 2017). Many cases involve large farm animals butting or kicking workers. Kicks to the head and chest result in more instantaneously fatalities, this is possibly due to the effects of direct trauma to the brain, heart, or lungs (Bury, et al., 2012).

Animal behaviour is often unpredictable. Animals that are usually docile can become agitated in certain situations, an example of this is shown in a Swedish study of dairy cows. The study looked at the amount of potentially dangerous incidents and risk situations when moving cows to be milked compared to moving them to have hoof trimming carried out. It found that a significantly higher amount of potentially dangerous incidents and risk situations occurred when moving cows to hoof trimming compared to milking (Lindahl, et al., 2016).

The risk of injury from an animal encounter is also increased when it involves animals that have not been handled frequently or newly calved cows, this can occur when animals being moved, separated or released. Proper livestock handling systems are important to ensure calm animals and a safe work environment for farm workers. Many accidents involving cattle could be avoided with better handling facilities (Health and Safety Executive, 2012).

Handling facilities should include a crush or race suitable for the cattle that will be handled. A crush/ race should allow most straightforward chores to be carried out safely. They should have adequate light, be easily accessible and have an emergency escape or slip gates for staff (Health and Safety Authority, 2010b)

3.2 Zoonotic Disease

Zoonotic disease or zoonoses or zoonosis are diseases and infections which are transmittable between animals and people. They include a wide variety of disease types including parasitic, fungal, bacterial and viral. They can cause illness by infecting the body when they are inhaled, swallowed, absorbed through the eyes or when they penetrate the skin through small cuts or grazes. In the UK in the agriculture sector about 20,000 people per year are affected by zoonoses (Health and Safety Executive, 2017).

In Ireland 20 zoonosis are known to exist these include brucellosis, tuberculosis, tetanus, leptospirosis (from rats or cattle urine), escherichia coli O157, ringworm, orf and toxoplasmosis (Health and Safety Authority, 2017b). Mahon, et al., (2017) found concerning the level of Irish farmers’ knowledge and awareness of the spread of infection from animals to humans (Mahon, et al., 2017).

3.2.1 Control Measures

Control measures should be put in place to prevent the spread of infections. Theses should include: avoiding or, if not possible, reducing contact with animals; maintaining a healthy herd; vaccinating; covering all wounds, cuts and scratches; immunising (for example, against tetanus); using protective equipment (for example, gloves, aprons); and maintaining good personal hygiene (Health and Safety Authority, 2017b).

3.2.2 Further Research

A lot of the focus on zoonotic disease research is related to food safety and public health, no Irish research exists on the prevalence of zoonotic diseases as a result of occupational exposure in agriculture. International research mostly relates to veterinary surgeons.

Section 4 Work Related Musculoskeletal Disorders (MSDs)

4.1 Definition and Effects

MSDs are a group of disorders affecting the musculoskeletal system and can present in the tendons, muscles, joints, blood vessels and/or nerves of the limbs and back (National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, 1997). Symptoms can include pain, discomfort, numbness and tingling in the affected area and can range in severity from mild to severe, they can also be periodic, chronic or debilitating (Health and Safety Authority, 2013). MSDs especially lower back pain often results in work disability requiring farmers to take time off work, to change work habits and to get help on the farm (Osborne, et al., 2013).

4.2 Theories of Musculoskeletal Injury Causation

Four theories exist to explain the causes of MSDs, all centre around the assumption that MSDs are biomechanical in nature. They can all occur at the same time and interact with each other and each MSD can be a combination of them.

4.2.1 Multivariate Interaction Theory

Injury to the musculoskeletal system is due to individual components and their mechanical properties. These components can be affected by individual’s physical characteristics, size, shape, and structure and by their psychosocial makeup. They can also be affect by the type of biomechanical hazards in their occupation.

4.2.2 Differential Fatigue Theory

Unbalanced occupational activities create different fatigue and in doing so an imbalance in body movement resulting in injury.

4.2.3 Cumulative Load Theory

This theory suggests that each component of the musculoskeletal system has a threshold range of load and repetition. Wear and tear causes deterioration of the component, each component has a limited life and after this an injury occurs.

4.2.4 Overexertion Theory

This theory is based on when excessive physical effort surpasses the tolerance limit of the musculoskeletal system or its components. Force, duration, posture and motion interact to cause occupational musculoskeletal injury (Kumar, 2001).

4.3 Prevalence

Russell, et al., (2015) found that between 2001 and 2012 the highest injury rates were in the agriculture sector, of those musculoskeletal disorders were the most common form. Between 2002 and 2014 musculoskeletal disorders accounted for 63 percent of all injuries recorded and agriculture workers were 2.2 times as likely to experience one as in all sectors combined (Kenny, et al., 2018) (Russell, et al., 2015) (Russell, et al., 2016) (Osborne, et al., 2012).

In a 2010 published study of 600 Irish farmers, 56% had experienced a MSD in the previous year. MSDs included: back pain (37%); neck/shoulder pain (25%); knee pain (9%), hand–wrist–elbow pain (9%), ankle/foot pain (9%) and hip pain (8%) (Osborne, et al., 2010). This reiterated the findings of a 2009 study which showed there was a high prevalence of lower back pain felt by Irish Farmers (O’Sullivan, et al., 2009).In 2006 a study in Kansas also found 60% of farmers reported an MSD symptom in the previous year (Rosecrance, et al., 2006).

4.4 Risk Factors in Agriculture

Musculoskeletal disorders are a major cause of pain and incapacity among working adults. Working in jobs where ergonomic conditions are poor may lead to the development of musculoskeletal disorders (Madan & Grime, 2015). In agriculture the main risk factors are: lifting and carrying heavy loads; sustained or repeated full body bending (stoop); very highly repetitive work; excessive force; and very awkward posture during lifting activities; (Fathallah, 2010) (Health and Safety Authority, 2018b).

Additionally Osborne, et al., (2010) found that the number of hours worked by farmers makes them predisposed to MSDs. (Osborne, et al., 2010). Russell, et al., (2015) also found longer working hours are linked with a higher likelihood of both injury and illness (Russell, et al., 2015).

4.5 Control measures

Although it is difficult to control some of the hazards associated MSDs, improvements can be made. These should include: reducing load size; using attachments on tractors; improving seating in tractors; improving storage facilities; raising work platforms or benches; fitting wheels to heavy loads; using hitch three-point linkage systems (Health and Safety Authority, 2018b).

Section 5 Higher Risk Categories

5.1 Older Farmers

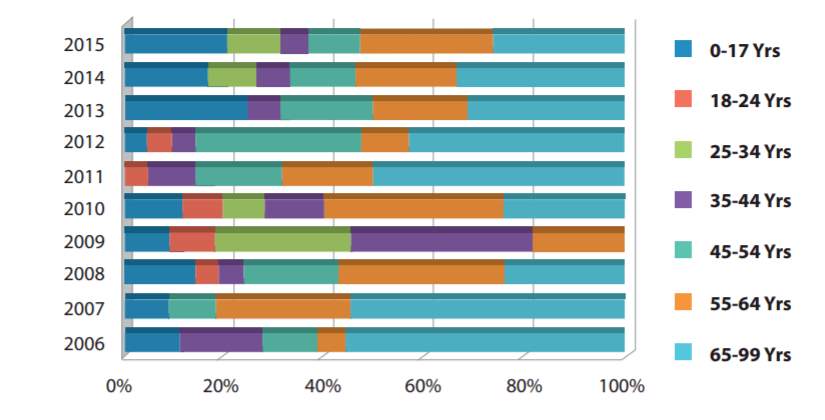

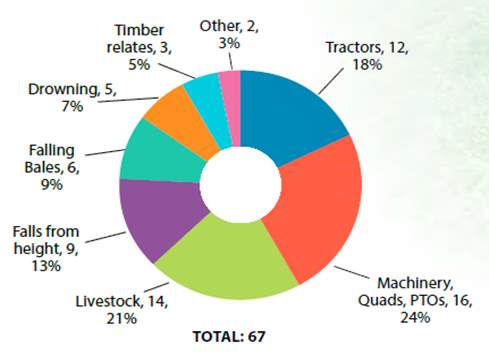

In Ireland around 30% of farms are operated by those aged 65 and over (Dillon, et al., 2015) (Dillon, et al., 2017). The average age of an Irish farmer is 57 years (Health and Safety Authority, Farm Safety Partnership, 2016). Older farmers are at a greater risk of having accidents, farmers aged 65 or more accounted for 35 percent of all farm fatalities between 2006 and 2015 see figure 3. Most of these deaths are thought to be associated with reduced speed of movement and reduced agility in the use of tractors and machinery; livestock handling and falls from heights see Figure 4 (Health and Safety Authority, 2017b).

Heaton, et al., (2012) found age-linked health problems may impact the aging farmer’s ability to respond to hazards and avoid injury. Farmers who had mobility problems were twice as likely to have an injury as those with out (Heaton, et al., 2012). Furthermore the chance of work-related illness increases with age (Russell, et al., 2015). Farmers who were older and had farmed over long hours, over a long period of time were more likely to suffer with hip problems (Osborne, et al., 2010).

Figure 3 Farming fatalities by age 2006- 2015 (Health and Safety Authority, 2017b)

Figure 3 Farming fatalities by age 2006- 2015 (Health and Safety Authority, 2017b)

Figure 4 Causes of fatal accidents in farmers 65 and over (2006-2015) (Health and Safety Authority, 2017b)

5.2 Children and Young People

Farms are an unusual place of work in so far as they often combine a family home and a hazardous workplace. Farming as well as being an occupation, is a way of life for most farmers, part of their identity. While parents are often aware of the hazardous environment, they choose to bring child on to a farm as they feel the benefits are greater than the risks (Elliot, et al., 2018). The Health and Safety Authority define a child as a person who is under 16 years of age or the school leaving age (whichever is the higher) and a young person as older than a child but under the age of 18 (Health and Safety Authority, 2010a).

Children and people aged under 18 suffered 12 percent of fatal farm accidents between 2006 and 2015 (Health and Safety Authority, 2017b). Watson, et al. (2017) suggested that younger farmers were more likely to take risks where risk taking was measured in terms of failing to routinely take safety precautions (Watson, et al., 2017). In Canada a study has shown risk taking behaviour is much higher in farm verses non-farm children. Farm adolescents partake more often in multiple risk-taking and it is this risk taking that is linked with incidences of serious injury in farms adolescents (Pickett, et al., 2017)

Section 6 Stress

6.1 Definition

Lazarus (1966) defined stress as a person/ environment relationship. Stress and emotion depend on how a person assesses their interactions with their environment and how they react. Stress arises when a person perceives that they cannot effectively cope with the demands being made on them or with threats to their well-being (Lazarus, 1966). Furthermore Lazarus and Folkman (1984) found ‘stress results from an imbalance between demands and resources’ (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984).

6.2 Causes of stress

Research into stress and stressors such as economic worry is conflicting. Glasscock, et al., (2006) suggest that higher levels of stress and poor safety behaviour were associated with an increased risk of injury (Glasscock, et al., 2006). Watson, et al., (2017) could find no firm relationship between risk taking and stress and found that in general, farmers reported low levels of distress (Watson, et al., 2017). In comparison Parry, et al., (2005) found a complicated web of factors make farming a particularly (or potentially) stressful occupation. The main causes of stress among farmers are: uncertainties due to markets, farm prices and farm policies; financial worries,excessively long working hours, poor working conditions, poor health and isolation (Parry, et al., 2005). Furey, et al., (2016) established farmers frequently work alone, for long periods, in difficult and often unpredictable conditions (Furey, et al., 2016).

6.3. Potential Outcome of Stress – Depression and Suicide

A study in the U.S.A. demonstrated that farming was among the highest occupations for rates of suicide. This study also suggested farmers may be at a higher risk of suicide due to job-related isolation and demands, stressful work environments, and work-home imbalance, as well as socioeconomic inequities, including lower income, lower education level, and lack of access to health services (McIntosh, et al., 2016). Furthermore Tiesman, et al. (2015) found that the issues that may contribute to the high rate include the potential for financial losses, chronic physical illness, social isolation, work–home imbalance, depression due to chronic pesticide exposure, and barriers and unwillingness to seek mental health treatment (Tiesman, et al., 2015).

Section 7 Accident Prevention Strategies

7.1 Occupational Health and Safety Legislation

In some areas of farming, legislation and regulation have been proven to reduce fatalities. An example of this was the regulations requiring ROPS (Springfeldt, 1996). Although there is no single European-level directive that explicitly deals with the safeguarding the health and safety of workers in all areas of agriculture, under Irish health and safety legislation farmers have similar duties to other employers (European Commission, 2012).

Farmers must produce a safety statement or comply with the terms of a Code of Practice. They must also carry out hazard identification and risk assessments, these legal requirements are incorporated into Safety, Health and Welfare at Work Act 2005 (Government of Ireland, 2005). They must also comply with Safety, Health and Welfare at Work (General Application) Regulations 2007 to 2016 (Government of Ireland, 2007) (Government of Ireland, 2016). Tractors, farm machinery and guards must comply with European Communities (Machinery) Regulations 2008 to 2015 (Government of Ireland, 2008) (Government of Ireland, 2011) (Government of Ireland, 2015).

Farmers must ensure their activities do not harm themselves or others. If employed they must co-operate with their employers and use any personal protective equipment to them. Safety hazards must be reported, they must ensure safety devices are not misused, interfered with or bypassed. Farmers should their consult with their employer on matters of safety and health and take account of any training and instruction which they have been given (Government of Ireland, 2005).

7.2 Health and Safety Authority (HSA)

The HSA is tasked with implementing and monitoring many of the accident prevention strategies in Ireland. The aim of these strategies is to improve the level of safety and health in the agriculture sector, to raise awareness and to prevent accidents. They do this by running information campaigns, publishing safety alerts, providing education and training, carrying out inspections, enforcing occupational health and safety legislation and prosecuting farmers when they are found to be in breach of this legislation (Health and Safety Authority, 2017c).

In 2017 the HSA carried out 2000 inspections on Irish farms with a further 2000 planned for 2018 (Health and Safety Authority, 2018). Annual inspection rates have been linked with lower levels of injury and ill-health, with inspections showing positive effect on new recruits. Cuts in public expenditure have affected the annual inspection rate which has fallen since 2009 this may have negative effect on workers’ health and safety in the future (Russell, et al., 2015).

After being inspected 92% of employers said they had an increased commitment to health and safety, 90% believed there was less chance of an accident at their place of work, 89% had a greater understanding of hazards in their workplace and 74% had taken action on health and safety issues that they knew about but had not previously actioned (Health and Safety Authority, 2017c).

7.3 Farm Safety Partnership Advisory Committee

To help improve the level of safety and health the HSA set up the Farm Safety Action Group (renamed Farm Safety Partnership Advisory Committee (FSPAC)), this group included all the major stakeholders in agriculture and could implement a coordinated multiagency approach to health and safety in agriculture. The FSPAC developed Farm Safety Action Plans (2009-2012), (2013-2015) and (2016-2018), which set out goals and associated actions to improve OSH (Health and Safety Authority, Farm Safety Partnership, 2009) (Health and Safety Authority, Farm Safety Partnership, 2013) (Health and Safety Authority, Farm Safety Partnership, 2016).

The 6 goals included in the 2016-2018 which aim to improve OSH in the sector are as follows

•Change cultural behavioural through research, education and training.

•Develop programmes that will foster innovative approaches and deliver engineering solutions to reduce the hazards.

•Reduce the level of injury arising from tractor and machinery use.

•Establish initiatives to reduce number of injuries arising from working with livestock.

•Ensure high standards of health and safety are adopted in timber work on farms.

•Implement programmes for the protection of health and wellbeing of people working in agriculture (Health and Safety Authority, Farm Safety Partnership, 2016).

7.4 Codes of Practice

The HSA produce Codes of Practice with the aim of reducing accidents in the agriculture sector. In 2010 they published Code of Practice on Preventing Accidents to Children and Young Persons in Agriculture. In consultation with FSPAC the HSA has revised the Code of Practice for Preventing Injury and Occupational Ill Health in Agriculture 2017. This revision focuses on improving the level of safety and health of all people in the agriculture by providing practical guidance in the implementation of the Safety, Health and Welfare at Work Act 2005 (Health and Safety Authority, 2017b).

7.5 Education

Hagel, et al., (2008) found that educational interventions alone were not linked with noticeable improvements in farm safety practices, physical farm hazards, or farm-related injury outcomes (Hagel, et al., 2008). Morgaine, et al., (2014) also found in a study in New Zealand that even a well-conducted safety awareness workshop, tailored to farmers was not enough to change safety practices. They suggested that future interventions may be more likely to succeed if they were wide-ranging, included environmental and enforcement features, and target more than one farm member (Morgaine, et al., 2014).

Section 8 Conclusion

Agriculture is one of the most dangerous occupations worldwide, hazards are numerous and diverse. Accidents resulting in fatality or injury are often caused by tractors and farm vehicles; machinery; falls and collapses; and livestock handling. The introduction of ROPS has caused a decline in the number of fatalities and serious injuries due to overturns.

Being hit, run over or crushed by a tractor is still a frequent cause of injuries both fatal and non-fatal. Quad bike fatalities are increasing and research is required into the effectives of ROPS for this type of farm vehicle. PTO entanglements are responsible for 11% of farm fatalities in Ireland and most could be prevented by the use of a guard that complies with the European Standard.

Encounters with livestock frequently result in injuries and fatalities, animal behaviour is unpredictable. Well planned handling facilities can prevent these occurrences. Little is known about the prevalence of zoonotic disease as an occupational health and safety issue in agriculture in Ireland, further research is required in this area.

Work-related injuries are common in agriculture and musculoskeletal disorders are most frequently encountered. MSDs often result in pain and incapacity among farmers. Working long hours; lifting and carrying heavy loads; sustained or repeated full body bending (stoop); very highly repetitive work; excessive force; and very awkward posture during lifting activities; are the causes the main causes of MSDs in agriculture.

Some members of the farming community are at a greater risk of injury, children, young people and older farmers are an example of this. Older farmers’ injuries are thought to be associated with reduced speed of movement and reduced agility. Studies have shown children and young people from farms show more incidences of risky behaviour than non-farm children and young people.

There is conflicting evidence in regards the prevalence of stress in farming but most research agree uncertainties due to markets, farm prices and farm policies; financial worries, excessively long working hours, poor working conditions, poor health and isolation may lead to stress and in turn depression or suicide.

Accident prevention strategies in agriculture are varied. Strategies include education, training, regulatory and enforcement procedures. A coordinated multiagency approach is taken in the form of the Farm Safety Partnership Advisory Committee who produce Farm Safety Action Plans. This approach is proven to work better than education alone in the prevention of agricultural fatalities.

Section 9 Bibliography

“agriculture, n.”, 2018. OED Online. [Online]

Available at: http://www.oed.com/view/Entry/4181?redirectedFrom=agriculture

[Accessed 15 5 2018].

Ayers, P., Khorsandi, F., Wang, X. & Araujo, G., 2018. ROPS designs to protect operators during agricultural tractor rollovers. Journal of Terramechanics, Volume 75, pp. 49-55.

Bowman, S. et al., 2009. Impact of helmets on injuries to riders of all-terrain vehicles. Injury Prevention, Volume 15, pp. 3-7.

Bury, D., Langlois, N. & Byard, R. W., 2012. Animal-Related Fatalities—Part I: Characteristic Autopsy Findings and Variable Causes of Death Associated with Blunt and Sharp Trauma. Journal of Forensic Sciences, 57(2), pp. 370-374.

Day, L. M., 1999. Farm work related fatalities among adults in Victoria, Australia: The human cost of agriculture. Accident Analysis & Prevention, 31(1-2), pp. 153-159.

Dillon, E. et al., 2015. Teagasc National Farm Survey: The Sustainability of Small Farming in Ireland. Athenry, Co Galway, Ireland: Teagasc.

Dillon, E., Moran, B., Lennon, J. & Donnellan, T., 2017. Teagasc National Farm Survey Preliminary Results 2017. Athenry, Co. Galway, Ireland.: Teagasc.

Elliot, V. et al., 2018. Towards a deeper understanding of parenting on farms: A qualitative study. PLoS ONE, 13(6), pp. 1-18.

European Commission, 2012. Protecting health and safety of workers in agriculture, livestock farming, horticulture and forestry. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

Eurostat, 2018. NACE Rev. 2 Fatal and non-fatal accidents at work by economic activity, EU-28, 2014. [Online]

Available at: http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/images/a/ac/Accidents_at_work_YB2016_II.xlsx

[Accessed 17 5 2018].

Fathallah, F. A., 2010. Musculoskeletal disorders in labor-intensive agriculture. Applied Ergonomics, 41(6), pp. 738-743.

Furey, E. et al., 2016. The Roles of Financial Threat, Social Support, Work Stress, and Mental Distress in Dairy Farmers’ Expectations of Injury. Frontiers in Public Health, 4(126), pp. 1-11.

Glasscock, D. J., Rasmussen, K., Carstensen, O. & Hansen, O. N., 2006. Psychosocial factors and safety behaviour as predictors of accidental work injuries in farming, Work & Stress. An International Journal of Work, Health & Organisations, 20(2), pp. 173-189.

Government of Ireland, 2005. Safety, Health and Welfare at Work Act S.I. No. 10 of 2005. Molesworth Street, Dublin, Ireland: Government Publications.

Government of Ireland, 2007. Welfare at Work (General Application) Regulations S.I. No. 299 of 2007. Molesworth Street, Dublin, Ireland: Government Publications.

Government of Ireland, 2008. European Communities (Machinery) Regulations S.I. No. 407 of 2008. Molesworth Street, Dublin, Ireland: Government Publications.

Government of Ireland, 2011. European Communities (Machinery) (Amendment) Regulations S.I. No. 310 of 2011. Molesworth Street, Dublin, Ireland: Government Publications.

Government of Ireland, 2015. European Communities (Machinery) (Amendment) S.I. No. 621/2015. Molesworth Street, Dublin, Ireland: Government Publications.

Government of Ireland, 2016. Safety, Health and Welfare at Work (General Application) (Amendment) Regulations S.I. No. 36/2016. Molesworth Street, Dublin, Ireland: Government Publications.

Government of Ireland, 2017. Census 2016 Summary Results – Part 2, Dublin: Central Statistics Office.

Grzebieta, R., Rechnitzer, G., Simmons, K. & McIntosh, A., 2015. Final Project Summary Report: Quad Bike Performance Project Test Results, Conclusions and Recommendations Report 4, 92-100 Donnison Street, Gosford, New South Wales 2250, Australia: The Workcover Authority of New South Wales.

Hagel, L. et al., 2008. Educational interventions delivered via the AHSN program were not associated with observable differences in farm safety practices, physical farm hazards, or farm-related injury outcomes. Injury Prevention, 15(5), pp. 290-295.

Health and Safety Authority, Farm Safety Partnership, 2009. Farm Safety Action Plan 2009- 2012. The Metropolitan Building, James Joyce Street, Dublin, Ireland: Health and Safety Authority.

Health and Safety Authority, Farm Safety Partnership, 2013. Farm Safety Action Plan 2013-2015. The Metropolitan Building, James Joyce Street, Dublin, Ireland: Health and Safety Authority.

Health and Safety Authority, Farm Safety Partnership, 2016. Farm Safety Action Plan 2016- 2018. The Metropolitan Building, James Joyce Street, Dublin, Ireland: Health and Safety Authority.

Health and Safety Authority, 2010a. Code of Practice on Preventing Accidents to Children and Young Persons in Agriculture. s.l.:Health and Safety Authority.

Health and Safety Authority, 2010b. Safe Handling of Cattle on Farms – How safe are you – Information Sheet. The Metropolitan Building, James Joyce Street, Dublin 1: Health and Safety Authority.

Health and Safety Authority, 2013. Guidance on the prevention and management of musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs) in the workplace. The Metropolitan Building, James Joyce Street, Dublin 1.: Health and Safety Authority.

Health and Safety Authority, 2017a. Summary of Workplace Injury, Illness and Fatality Statistics 2015–2016. Metropolitan Buildings, James Joyce Street, Dublin, Ireland: Health and Safety Authority.

Health and Safety Authority, 2017b. Code of Practice for Preventing Injury and Occupational Ill Health in Agriculture. Metropolitan Buildings, James Joyce Street, Dublin, Ireland: Health and Safety Authority.

Health and Safety Authority, 2017c. Annual Report 2016. Metropolitan Building, James Joyce Street, Dublin 1.: Health and Safety Authority.

Health and Safety Authority, 2018a. Quad Bike Safety Update. Metropolitan Buildings, James Joyce Street, Dublin: Health and Safety Authority.

Health and Safety Authority, 2018b. Reducing the Risk of Back Injuries on the Farm. Metropolitan Buildings, James Joyce Street, Dublin 1: Health and Safety Authority.

Health and Safety Authority, 2018. Programme of Work. Metropolitan Building, James Joyce Street, Dublin 1.: Health and Safety Authority.

Health and Safety Executive, 2012. Agriculture Information Sheet No 35 (Revision 1) – Handling and housing cattle. Sudbury: Health and Safety Executive.

Health and Safety Executive, 2017. Farmwise: Your essential guide to health and safety in agriculture. 3rd ed. Norwich, Untied Kingdom: The Stationery Office.

Health and Safety Executive, 2017. Health and Safety in the Agriculture, Forestry and Fishing Sector in Great Britain, 2017, Sudbury, Great Britain: HSE Books.

Heaton, K. et al., 2012. The effects of arthritis, mobility, and farm task on injury among older farmers. Nursing: Research and Reviews, Volume 2, pp. 9-12.

Horsburgh, S., Feyer, A. & Langley, J., 2001. Fatal work related injuries in agricultural production and services to agriculture sectors of New Zealand, 1985–94. Occupational and Environmental Medicine, Volume 58, pp. 489-495.

Kenny, O., Maître, B. & Russell, H., 2018. Analysis of Work-related Injury and Illness, 2001 to 2014 Agriculture, Forestry and Fishing Sector – Sectoral Analysis No. 4: Agriculture, Forestry and Fishing Sector, Whitaker Square, Sir John Rogerson’s Quay, Dublin, Ireland: The Economic and Social Research Institute & The Health and Safety Authority.

Kumar, S., 2001. Theories of musculoskeletal injury causation. Ergonomics, 44(1), pp. 17-47.

Lazarus, R., 1966. Psychological stress and the coping process. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Lazarus, R. & Folkman, S., 1984. Stress, Appraisal and Coping. New York: Springer.

Lindahl, C., Pinzke, S., Herlin, A. & Keeling, L. J., 2016. Human-animal interactions and safety during dairy cattle handling-Comparing moving cows to milking and hoof trimming. Journal of Dairy Science, 99(3), p. 2131–2141.

Madan, I. & Grime, P. R., 2015. The management of musculoskeletal disorders in the workplace. Best Practice & Research Clinical Rheumatology, 29(3), pp. 345-355.

Mahon, M. et al., 2017. An assessment of Irish farmers’ knowledge of the risk of spread of infection from animals to humans and their transmission prevention practices. Epidemiology and Infection, 145(12), p. 2424–2435.

McIntosh, W. et al., 2016. Suicide Rates by Occupational Group — 17 States, 2012. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR) , 65(25), pp. 641-645.

Morgaine, K., Langley, J., McGee, R. & Gray, A., 2014. Impact evaluation of a farm safety awareness workshop in New Zealand. Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment & Health, 40(6), pp. 649-653.

National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, 1997. Musculoskeletal Disorders and Workplace Factors. A Critical Review of Epidemiologic Evidence for Work-related Musculoskeletal Disorders of the Neck, Upper Extremity, and Low Back. DHHS(NIOSH) Publication No. 97–141 ed. Cincinnati: National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health.

Osborne, A. et al., 2012. Prevalence of musculoskeletal disorders among farmers: A systematic review. American Journal of Industrial Medicine, 55(2), pp. 143-158.

Osborne, A. et al., 2010. Musculoskeletal disorders among Irish farmers. Occupational Medicine, 60(8), p. 598–603.

Osborne, A. et al., 2013. An evaluation of low back pain among farmers in Ireland. Occupational Medicine (London), 63(1), pp. 53-59.

O’Sullivan, D., Cunningham, C. & Blake, C., 2009. Low back pain among Irish farmers. Occupational Medecine , 59(1), p. 59–61.

Pacific Northwest Agricultural Safety and Health Center, 2004. National Tractor Safety Initiative. Seattle: National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health.

Parry, J., Barnes, H., Lindsey, R. & Taylor, R., 2005. Farmers, Farm Workers and Work-Related Stress, Sudbury, Great Britain: Health and Safety Executive.

Pickett, W., Berg, R. & Marlenga, B., 2017. Social environments, risk-taking and injury in farm adolescents. Injury Prevention, 23(6), pp. 388-398.

Rorat, M., Thannhauser, A. & Jurek, T., 2015. Analysis of injuries and causes of death in fatal farm-related incidents in Lower Silesia, Poland. Annals of Agricultural and Environmental Medicine, 22(2), pp. 271-274.

Rosecrance, J., Rodgers, G. & Merlino, L., 2006. Low back pain and musculoskeletal symptoms among Kansas farmers. American Journal of Industrial Medicine, Volume 49, pp. 547-556.

Russell, H., Maître, B. & Watson, D., 2015. Trends and Patterns in Occupational Health and Safety in Ireland. Whitaker Square, Sir John Rogerson’s Quay, Dublin, Ireland: The Economic and Social Research Institute.

Russell, H., Maître, B. & Watson, D., 2016. Work-related Musculoskeletal Disorders and Stress, Anxiety and Depression in Ireland: Evidence from the QNHS 2002–2013. Whitaker Square, Sir John Rogerson’s Quay, Dublin, Ireland: The Economic and Social Research Institute.

Shulruf, B. & Balemi, A., 2010. Risk and preventive factors for fatalities in All-terrain Vehicle Accidents in New Zealand. Accident Analysis & Prevention, 42(2), pp. 612-618.

Sorensen, J. et al., 2017. A Comparison of Interventional Approaches for Increasing Power Take-off Shielding on New York Farms. Journal of Agromedicine, 22(3), pp. 251-258.

Springfeldt, B., 1996. Rollover of tractors — international experiences. Safety Science, 24(2), pp. 95-110.

Tiesman, H. M. et al., 2015. Suicide in U.S. Workplaces, 2003–2010. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 48(6), pp. 674 – 682.

Transport and Road Safety (TARS), 2017. Quad Bike and OPD workplace Safety Survey Report : Results and Conclusions, 92-100 Donnison Street, Gosford, New South Wales 2250: SafeWork NSW.

Watson, D., Kenny, O., Maître, B. & Russell, H., 2017. Risk taking and accidents on Irish farms, Whitaker Square, Sir John Rogerson’s Quay, Dublin, Ireland: The Economic and Social Research Institute.

Cite This Work

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing stye below:

Related Services

View allRelated Content

All TagsContent relating to: "Farming"

Farming is the business or activity of working on a farm. Farming activities include ground preparations, sowing or planting seeds, tending crops, or activities involved in the raising of animals for meat or milk products.

Related Articles

DMCA / Removal Request

If you are the original writer of this dissertation and no longer wish to have your work published on the UKDiss.com website then please: