The Battle at Chosin Reservoir, 27 November – 01 December 1950

Info: 8622 words (34 pages) Dissertation

Published: 9th Dec 2019

The Battle at Chosin Reservoir, 27 November – 01 December 1950

Introduction

The battle at Chosin Reservoir was fought between the UN forces and the Chinese People’s Volunteer Army (PVA) during the Korean War, from 27 November 1950 to 02 December 1950. This battle was a turning point in the war that forced UN leaders to transition from offensive to defensive operations. The UN forces were unable to regain a decisive advantage over North Korean and Chinese forces for the remainder of the war, and focused on defensive operations until the armistice was signed in 1953. This analysis will focus on the actions of LTC Don Carlos Faith, Jr, the commander of the 31st Regimental Combat Team (RCT), specifically his application of the principles of mission command. The 31st RCT was a task force of 3,200 Soldiers from the US Army 7th Infantry Division, hastily assembled to defend the 1st Marine Corps Division’s right flank to the east of Chosin Reservoir. Despite suffering 90% casualties, the 31st RCT (later known as Task Force Faith) fixed two PVA divisions long enough to allow the 1st Marine Division to secure Hagaru-ri, the UN Forces’ only supply point and airfield in the vicinity. Securing Hagaru-ri allowed the Marines to retrograde to the port city of Hamhung and evacuate UN forces and civilians in the area. On the surface it would appear that the 31st RCT failed to accomplish its mission given the high casualty rate and ultimate failure of the 1st Marine Division to conduct offensive operations. However, LTC Faith’s ability to quickly establish trust, provide clear commander’s intent, exercise disciplined initiative, and accept prudent risk ensured the survival of his remaining Soldiers and ultimately accomplished the 31st RCT’s mission of defending the 1st Marine Division’s eastern flank.

Strategic, Operational, and Tactical Setting

Strategic Setting

Following World War II, the US, USSR, China, and Great Britain declared the Korean Peninsula an “international trustee” and it was divided into two territories along the 38th parallel. This separation was only intended to last for five years, after which time the Korean Peninsula would be re-established as a unified state.1 To the north, the USSR supported a communist government lead by Kim Il Sung. The US supported an anti-communist government in the south lead by Syngman Rhee. By 1948, the US and USSR had both withdrawn forces from Korea, leaving two highly nationalistic states that viewed each other as the “personification of evil…committed to the imposition of their respective rule throughout the Korean peninsula.”2 Between 1948 and1950, North Korean leader Kim built and trained military forces (referred to as DPRK forces), and obtained military advisors and equipment including tanks, artillery, small arms, aircraft, and ground vehicles from the USSR and Communist China.2 After five years of tension and with no feasible reunification plan established by the UN, North Korea invaded South Korea on 25 June 1950 with the intent of unifying the peninsula under communist rule.

Following the initial failure of UN forces to disrupt DPRK offensive operations, General Douglas MacArthur, commander of UN forces, planned and executed a successful breach of DPRK forces at Incheon in September 1950. The operation was a success, and UN forces began offensive operations against the DPRK. By late October, DPRK forces had been forced as far north as the Yalu River in some areas of the peninsula and the conflict appeared to be drawing to a close. However, Chinese forces totaling sixteen divisions (up to 380,000 troops3) had entered North Korea by early November to reinforce the retreating DPRK forces. Despite intelligence reports to the contrary, General MacArthur and Lieutenant General Edward Almond, Commander of the US Tenth Corps, believed the PVA forces were not a significant threat.4 General MacArthur’s final offensive operation, with the purpose of delivering the final defeat of DPRK forces, was to be launched from the Chosin Reservoir, located in the northeast corner of North Korea. As late as 25 November, General MacArthur told troops to expect to be home by Christmas.

Operational Setting

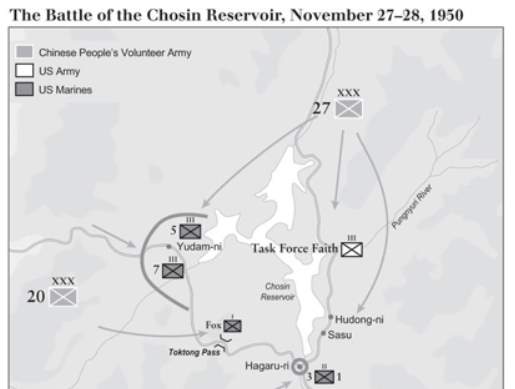

Figure 1 USMC and 31st RCT positions 27 November (Cleaver, 2012)

The 1st Marine Corps Division, consisting of the 5th and 7th Marine Regiments and US Army 7th ID arrived at the Chosin Reservoir by mid-November. The 7th Marines occupied the west side of the reservoir, while the 5th Marines occupied the east side.5 After intelligence reports indicated increasing numbers of PVA in the area, LTG Almond and MG Oliver Smith (Commander of the 1st Marine Corps Division) decided to move the 5th Marines to the west side of the reservoir to combine with the 7th Marines. MG David Barr, US Army 7th ID Commander, was ordered to assemble a task force to replace the 5th Marines and protect the 1st Marine Division’s eastern flank within 36 hours.6 This hastily assembled task force became the 31st RCT, commanded by COL Allen McLean.

Tactical Situation

Size and Composition. The 31st RCT consisted of the 1/32nd IN BN, 3/31st IN BN, 57th FA BN, D Battery, 15th AAA BN, 31st, and one heavy mortar company totaling 3,200 Soldiers. The 2/31st IN BN, 31st Medical Company, and 31st Tank Company were also assigned to the 31st RCT, but never arrived at the reservoir due to the rough terrain and PVA attacks at the base of Hill 1221. These units would have provided an additional 1,500 Soldiers.7 At the time MG Barr ordered the formation of the 31st RCT, the individual units selected were spread out between the port city of Hamhung and Hagaru-ri.8 Conversely, the PVA consisted of the 80th Division and elements of the 81st Division, totaling up to 20,000 Soldiers.

Technology. The 31st RCT used weapons and vehicles from WWII, which frequently malfunctioned in the extremely cold temperatures. The most influential weapon assigned to the 31st RCT was the 57th FA BN’s M19s. However, the lack of 40mm ammunition rendered them ineffective by the third day of the battle, degrading the 31st RCT’s ability to fight the PVA forces during the breakout on 01 December. The Soldiers lacked proper cold weather uniforms, which only consisted of light field jackets, windbreakers, and regular gloves during the battle.9 PVA forces possessed Soviet-designed weapons and artillery meant to withstand cold weather conditions of Siberia, causing less degradation due to the cold.10

Doctrine and Training. Prior to the battle, the 31st Regiment was originally stationed in Japan following WWII and experienced a high turnover rate prior to its involvement at the Chosin Reservoir. Many senior officers and NCOs were reassigned to 8th Army units fighting in Busan prior to the Inchon landing, and the remaining Soldiers were generally inexperienced and inadequately trained.10 Nearly 70 percent of one company of 3/31st IN BN consisted of Soldiers on early release from the 8th Army Stockade.11 Upon arrival to Korea, South Korean Soldiers (KATUSAs) augmented US forces, making up one third of some battalions. The KATUSAs had little training and few spoke English, creating serious issues with unit cohesion and communication in combat.12 The Army did not have official doctrine for how to conduct breakout operations at this time, nor was discussion of breakout operations included in the curriculum at service schools.13 PVA forces were generally more experienced and better trained, having recently fought in the Chinese Communist Revolution lead by Mao Zedong.

Logistical Systems. Logistical support was generally poor.The locations of fuel points were not communicated causing many 1/32nd IN BN vehicles to run out of fuel before the battalion relocated to 3/31st IN BN’s position.13 Resupply was accomplished only by aerial drop, as the terrain was impassible and surrounded by PVA forces. High winds caused supplies to land outside the perimeter or several miles south of the 31st RCT’s position. The 31st RCT lacked medical services, including medical personnel, supplies, and MEDEVAC. The inability to evacuate their wounded would slow the 31st RCT’s breakout and caused more casualties as Soldiers were forced to defend the wounded rather than moving across the ice to join the 1st Marine Division.

Intelligence. The single greatest point of failure leading to the destruction of the 31st RCT was the dismissal of intelligence. The 7th ID, including the 31st RCT, depended primarily on aerial reconnaissance (used only during the daytime) for its intelligence and did not detect PVA forces moving at night.13 Although CAS assets were available, they were strictly used for airdrop resupply and CAS; no one thought to ask the pilots what they had seen regarding the enemy disposition or strength. Dismounted reconnaissance and patrolling was only utilized at the battalion level and below.14 The 31st RCT’s reconnaissance assets consisted only of one ISR platoon. GEN MacArthur and LTG Almond dismissed intelligence reports of increasing numbers of PVA Divisions approaching the Chosin Reservoir. They did not consider the PVA forces to be a significant threat, and dismissed the PVA forces as “retreating Chinese laundrymen” after the attack on 27 November.15 Intelligence sharing between the Marines and the Army was grossly insufficient because of the poor personal relationship between LTG Almond and MG Smith. The Marines refused to share the intelligence they received regarding PVA forces in the area, and the intentions of those forces.16

Condition and Morale. Morale was high at first due to GEN MacArthur’s statements to the Soldiers to expect to be home by Christmas.17 The attitude that the war was almost over created a relaxed attitude among the Soldiers that would be a contributing factor in the outcome of the battle,and was reinforced by the fact that they had only experienced fighting defeated DPRK forces up to this point.18 Continuous attacks from PVA forces degraded morale quickly. By 01 December, the remaining Soldiers had become apathetic, to the point that LTC Faith was forced to draw his weapon to force some Soldiers to move.19 MAJ Robert Jones, 1/32nd IN BN S3, later wrote “If LTC Faith and I had decided to shoot anyone in order to get their attention it wouldn’t have worked. Those people were too far along from injuries, frozen cold, shock, fear, and confusion to care. This may seem like a condemnation of the people of the task force, but it is not.”19

Command, Control, and Communications. Communications between the 31st RCT and its higher headquarters, the 1st Marine Division, and between the individual units of the 31st RCT were insufficient and directly contributed to the destruction of the 31st RCT. LTC Faith was forced to make decisions in a vacuum due to poor communication between himself, MG Barr, and LTG Almond. At the time, doctrine dictated that it was the responsibility of the higher headquarters to re-establish lost communications with a subordinate unit.20 LTG Almond, MG Barr, and MG Smith did not attempt to contact LTC Faith at any point from 28 November to the morning of 30 November (MG Barr re-established contact on 30 November only to inform LTC Faith that the 31st RCT should not expect reinforcements).21 GEN MarArthur and LTG Almond had issued several orders for the 31st RCT to withdraw prior to 01 December, but the orders were not delivered in a timely manner. The 31st RCT was two hours into the breakout when LTC Faith received the order to withdraw.22The 1st Marine Division and the 31st RCT did not have radio communications because they were not netted.23 The radios and communications equipment malfunctioned due to the extremely cold temperatures, forcing the 31st RCT to rely on runners to communicate between battalions. The reliance on runners was especially detrimental during the breakout. The radios used were WWII radios that were rebuilt in Japan after the war. They operated line-of-sight and weren’t capable of operating in extreme temperatures, which rendered them nearly useless in the cold and mountainous terrain.24 The most powerful radio the 31st RCT possessed was the SCR 193, which was mounted on the 3/4-ton vehicle and was used by COL McClean. It failed the night of 27 November.25 Because the radios were inoperative, the 31st RCT relied primarily on runners to communicate internally, which contributed to the breakdown in organization and subsequent loss of control during the breakout.26 MAJ Curtis, one of the surviving officers, stated that “during movement, radio communication from battalion to company to platoon was practically non-existent….The command group was out of communication with [MAJ] Miller and the rear guard. Runners could not run in the snow in shoe pacs.”27 As night fell during the breakout on 01 December, unit cohesion was lost as Soldiers became isolated from one another other in the dark and falling snow.28 In the chaos following the retreat from Hill 1221 with no communications from officers and NCOs, the Soldiers lost their will to stay as a unit and the survival instinct took over, with many escaping over the frozen reservoir.28

Leadership. Although individual officers and NCOs would later be recognized for their leadership in combat, leadership in the 31st RCT was generally poor due to high casualty rates among officers and NCOs.With so few officers and senior NCOs, junior NCOs and Soldiers were unexpectedly thrust into leadership positions. For example, following the initial attack on 27 November, the new I Co, 3/31st IN commander was an E-541. Other companies were also lead by E-5s, and platoon leaders were nearly all E-4s or below after 30 November.29

The most influential leader in the battle was LTC Faith. LTC Faith was a highly respected and well-liked leader in his battalion. His Solders viewed him as an intelligent, capable, and competent commander.30 In WWII, he served as General Matthew Ridgeway’s aide, and quickly rose through the ranks.31 At thirty-two years old, he was the youngest battalion commander in the regiment. His charisma and drive to accomplish the mission made him a positive, direct leader and created a “can do” attitude in his organization.32 Although he had combat experience, he had very little experience leading in combat.33 His experience in combat was limited to the retreating and defeated DPRK forces that did not put up much resistance.34

The Battle

Initial Disposition

Figure 2 Initial Disposition (Precious, 2012)

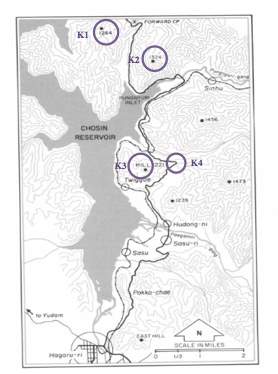

By nightfall on 27 November, the 1/32nd IN BN and 3/31st IN BN had established two mutually unsupported positions at Hill 1264 and 1324, respectively.35 South of the 3/31st IN BN, the 57th FA BN and D Battery, 15th AAA had established its defenses. No unit from the 31st RCT had occupied Hill 1221.

Day 1 – 27 November 1950

As the 31st RCT prepared its defensive position and awaited the arrival of the remainder of the task force, two PVA divisions, the 80th and elements of the 81st Division approached the east side of the Chosin Reservoir from the north. That night, the PVA forces attacked the 1/32nd IN BN position from the north. COL McLean had not anticipated encountering PVA forces, so defensive positions were only 50% manned.36 PVA forces quickly penetrated the defense established by 1/32nd IN and made its way south to the 3/31st IN position south of the Pungnyuri River. Only M Company, 3/31st IN was able to hold its position (this was the company comprised of 70% Soldiers on early release from 8th Army Stockade).37 The A Co, 57th FA BN was overrun, and its guns captured (the guns were recaptured hours later by B Co, 57th FA).38

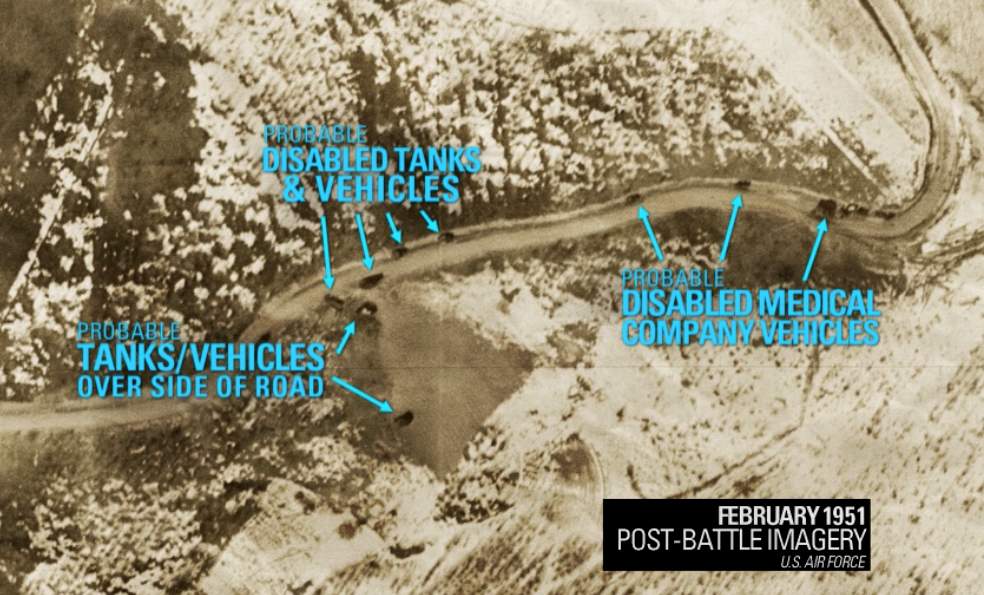

Meanwhile, the 31st Medical Company decided to attempt to join the 31st RCT from Hudong, despite exhaustion resulting from travelling that day. The company was ambushed south of Hill 1221, and never arrived at the Chosin Reservoir. Most of the medics, medical supplies, and ambulances were lost to the PVA forces.39

Day 2 – 28 November 1950

The majority of PVA forces withdrew at dawn, allowing the 31st RCT to regroup. At this point, the 31st RCT had suffered heavy casualties, including most of its officers. Two battalion commanders had been killed, leaving LTC Faith the only remaining battalion commander. The 1/32nd IN was completely cut off from the remainder of the task force and lacked ammunition, rations, and medical supplies. PVA continued to assault the 1/32nd IN position throughout the day, finally taking the valuable high ground overlooking the inlet by mid-morning.40

In the afternoon on 28 November, LTG Almond visited the 31st RCT CP to assess the damage from the previous night’s attack. He still believed the Chinese forces were the fleeing remnants of PVA the 7th ID had previously encountered. The PLA’s true disposition was still unclear at this time. Despite heavy losses, LTG Almond and COL McLean remained optimistic the 31st RCT could continue offensive operations. Only LTC Faith argued against continuing with the planned attack.41 LTG Almond ordered LTC Faith to re-take the high ground he had lost that day before dark. Before leaving, he presented LTC Faith with a Silver Star, despite his protests that there were Soldiers more deserving.42 Immediately following LTG Almond’s departure, LTC Faith threw the Silver Star into the inlet.43

At Hamhung, the 31st Tank Company began making its way north to the Chosin Reservoir. Like the 31st Medical Company, the PVA ambushed them as they approached Hill 1221 and forced them to withdraw after suffering casualties and losing four tanks. Also like the 31st Medical Company, the 31st Tank Company never made it to the Chosin Reservoir to assist the 31st RCT.44

Figure 3 Destroyed tanks and medical vehicles at the base of Hill 1221 (Precious, 2012)

After dark, the PVA resumed its attack against the 31st RCT. The 80th PVA Division attacked the 1st BN, 32nd INF position again. The B/1-32nd and C/1-32nd lines were penetrated, allowing the PVA to attack the battalion CP and Mortar Company. LTC Faith, with only his headquarters support personnel, defended the CP and fixed the PVA forces north of the mortar company until B/1-32nd was able to regroup and push the PVA back. By morning, the 1st BN, 32nd INF retook the high ground that had been lost the previous day.45

To the south, elements of the 81st PVA Division breached narrow sections of the perimeter several times throughout the night, penetrating as far south as the D Battery, 15th AAA position. However, the 3rd BN, 31st INF defenses, supported by the 57th FA and D/15th AAA were able to push the PVA back, ensuring that the defensive perimeter held until the following morning.46 At dawn, the PVA once again withdrew.

Day 3 – 29 November 1950

COL McLean and LTC Faith assessed that the 1/32nd INF would be unable to hold its position for another night, and decided to move the 1/32nd south of the Pungnyuri River to combine with the 3/31st INF. At 0440, COL McLean ordered the withdrawal of 1/32nd IN BN.47 As the 1/32nd IN BN made its way south, it encountered a roadblock built by the PVA. LTC Faith lead an attack of ten Soldiers to clear the roadblock with small arms fire and the convoy continued on. As the convoy approached Hill 1324, it became apparent that the 3/31st IN BN and 57th FA BN were still under heavy fire. The exhausted Soldiers of the 1/32nd IN BN crossed the frozen inlet to Hill 1324 under fire, and assisted the 3/31st and 57th FA until the PVA withdrew.48

Later that morning, COL McLean sighted a unit in the distance, and assumed it was the 2nd Battalion, 31st INF finally arriving to the reservoir. He ordered the 3/31st to stop returning fire, and ran onto the ice to stop the approaching unit. However, this was not the 2/31st IN BN, it was a battalion of PVA forces.49 COL McLean was shot and taken prisoner (he later died as a POW). At this point, LTC Faith assumed command of the 31st RCT.50

LTC Faith consolidated his remaining forces south of the Inlet. He attempted to obtain reinforcements from the 1st Marine Division, evacuate dead and wounded, and receive resupply. However, MG Smith refused to send reinforcements, arguing that he could not spare any of his forces lest Hagaru-ri, the only airfield and resupply point in the area, be seized by the PVA.51 This left the 31st RCT completely isolated. In the afternoon, two aircraft dropped ammunition and medical supplies on the 31st RCT’s position. However, due to high winds half of the supplies fell outside of the perimeter defense into the hands of the PVA.52 The supplies that did fall within the perimeter contained very little of the requested ammunition, medical supplies, and rations requested. Also missing from the resupply was the requested 40mm ammunition, which had been inadvertently dropped four miles south of their position.53 Once again, after dark, the PVA Forces attacked the 31st RCT’s perimeter defense, but the combined assets of the 1/32nd INF and 3/31st INF were able to keep the PVA from penetrating the perimeter.

Day 4 – 30 November 1950

A second airdrop of ammunition and supplies was conducted during the daytime, containing ammunition for crew served weapons and 4.2 inch mortars.54 However, the requested 40mm ammunition was once again missing from the resupply, as was the medical supplies.55

In the afternoon, MG Barr arrived to inform LTC Faith that no reinforcements were enroute. He stated “I would lose more men getting you out than what we would save,” and told LTC Faith that he had written the 31st RCT off as lost.56 LTC Faith requested MEDEVAC for the wounded Soldiers he currently had, but MG Barr denied his request. However, MG Barr arranged for CAS to assist with a breakout attempt. The 31st RCT was given first priority for CAS the next day.57

The PVA did not withdraw at dawn as they previously had, and attacks continued into the day. The 31st RCT was forced to use drivers, cooks, and headquarters support personnel to augment the infantry companies.58 As night fell, a snowstorm had begun, reducing visibility and bringing strong winds. PVA attacks intensified that night, and the 31st RCT was forced to reduce volume of fires due to the limited resupply that day. The 31st RCT held the perimeter most of the night, although in some areas Soldiers were forced to resort to hand-to-hand combat with PLA.59 Near dawn of 01 December, the PVA broke through one corner of the perimeter, gaining control of the high ground. A counterattack failed to retake the ground. A mortar had also hit the aid station, killing the medics and destroying the remaining medical supplies.60

Day 5 – 01 December

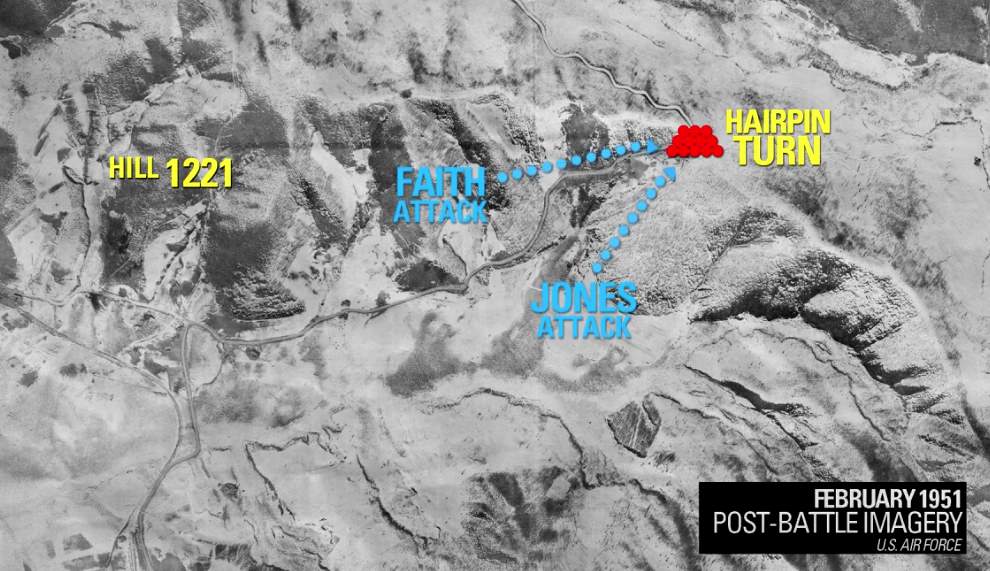

Figure 4 Attack on Hill 1221 and Roadblock (Precious, 2012)

LTC Faith made the decision to conduct a breakout, although he had not been ordered to do so.61 He ordered Soldiers to destroy unneeded cargo, supplies, and disabled vehicles to prevent them from being used by the PLA and load the wounded onto trucks.62 The PVA continued mortar attacks while preparations continued though the morning. Cloud cover and snow meant that CAS would be unavailable until ceiling and visibility improved around noon. At 1300, the convoy began moving south, and the PVA attacked in force. LTC Faith ordered the forward air controller (FAC) to direct an air strike, but the aircraft dropped napalm on the front of the convoy as well as PVA forces.63 This further degraded the morale of the Soldiers. LTC Faith regrouped his Soldiers and forced them to continue on. The convoy continued south while the FAC directed airstrikes against PLA, who were focusing fires on the wounded Soldiers in the vehicles. A blown bridge caused the convoy to stop, and LTC Faith was forced to move his convoy rear security to the west to fight of closing PLA, allowing for the PVA to disable or destroy vehicles of wounded in the rear.64 As the convoy approached Hill 1221, the PVA resistance continued to increase. At the base of Hill 1221, the PVA occupied a saddle at the apex of a hairpin turn and established a series of roadblocks to ambush the convoy as it attempted to pass.65 Disabled vehicles on the single-lane road blocked the convoy, forcing the 31st RCT to stop, unload wounded, load the wounded into a second vehicle, and push the disabled vehicle off the side of the cliff to allow the convoy to keep moving, until it encountered another roadblock.66 This cycle continued throughout the day and into the night. By nightfall, nearly all of the officers and NCOs had become casualties, and individual units “ceased to exist as organizations.”67

It became apparent that the roadblock needed to be cleared to allow the convoy to pass through. LTC Faith gathered his remaining officers and issued the order to take Hill 1221 and destroy the final roadblock at the apex of the hairpin turn.68 LTC Faith personally gathered assault teams and lead from the front as they assaulted Hill 1221, telling the wounded Soldiers “don’t just lie there and die. Lets go take that hill.”69 As Soldiers made it to the top of Hill 1221, LTC Faith shifted his focus and began to lead the attack on the roadblock. Approximately 30 meters from the objective, LTC Faith was hit with a grenade and mortally wounded, but continued to direct the attack until he bled out minutes later.70 While the attack on the roadblock was successful, the PVA was able to regain the initiative on Hill 1221 and overwhelmed the Soldiers, forcing them back down the hill. With their senior leadership gone and LTC Faith dead, the remaining officers and NCOs lead their Soldiers down the hill and fled across the ice on foot to attempt to join the 1st Marine Division.71 At this point, the 31st RCT was effectively disbanded.

Figure 5 Position where LTC Faith was wounded at the base of Hill 1221 (Precious, 2012)

Short Term Results. Despite heavy casualties, the 31st RCT fixed the two PVA Divisions for five days, preventing them from seizing Hagaru-ri before the 1st Marine Division had concentrated enough forces to defend it.72 Only 385 Soldiers survived to return to the front lines after the battle.73 Loss of Hagaru-ri would have blocked the only escape route for the US Forces. The sacrifice by the 31st RCT allowed the Marines to withdraw into Hagaru-ri, and rendered the PVA 80th and 81st Divisions combat ineffective. Those two divisions did not re-enter combat until April 1951.74

Long Term Results. After the defeat at Chosin Reservoir, the UN forces were unable to decisively regain the advantage over PVA and DPRK forces. The refusal to accept the intelligence reports of increasing presence of PVA forces by GEN MacArthur allowed them to mass combat power greater than or equal to UN combat power in North Korea. The result was a stalemate that lasted until the signing of the armistice in 1953.

Analysis

Area of Operations – Weather Analysis

Visibility / Winds. Strong winds, estimated greater than 30 mph, and snowstorms brought low visibility that lasted the duration of the battle.75 Snowstorms obscured visibility, allowing PVA forces to approach the 31st RCT’s perimeter undetected. High winds caused airdrop resupplies to be blown into PVA positions outside the 31st RCT’s perimeter. Fog and overcast conditions prevented Soldiers from seeing PVA forces during the breakout attempt, preventing them from returning fire.76

Temperature. Extremely cold temperatures were perpetuated by strong winds, causing reduced effectiveness of weapons and medical supplies, cold weather injuries, and death by hypothermia.77 During the day, temperatures were near 20°F, and as low as

-30°F at night (wind chill caused the temperature to drop even further).78 Several Soldiers froze to death in their foxholes at night.79 Blood plasma froze solid, leaving medics unable to treat Soldiers.80 The metal barrels on the M2 .50 caliber machine guns contracted due to the cold and could not fire. Soldiers resorted to taking turns urinating on the barrels to unfreeze them so they could fire.81

Precipitation / Cloud Cover. The low visibility caused by snow contributed to a loss of mission command, as defensive positions lost sight of one another during snowstorms.82 Heavy snowstorms brought 100% cloud cover and low ceilings on 01 December. This delayed the 31st RCT’s breakout plan, as CAS was essential for the breakout plan and unavailable during the snowstorm.83

Area of Operations – Terrain Analysis

Obstacles. The terrain was generally restrictive, consisting of mountains, hills, river inlets, and unimproved single-lane roads with no light. Mountainous terrain prevented armor assets from reaching the reservoir. Units south of the inlet were not aware of other units being attacked on the other side of the hill.84 The PVA forces successfully constructed roadblocks and destroyed bridges to prevent the 31st RCT from retrograding.

Figure 6 Key Terrain (Appleman, 1991, Kindle Edition)

Key Terrain. Four key terrain affected the 31st RCT’s operation. Hill 1264 (K1) was located northwest of the Pungnyuri River and occupied by 1/32nd IN BN for the first two days of the battle. It provided a key observation point (OP) for the occupying force for the area north of the inlet and a wide field of fire. Hill 1324 (K2) was the 3/31st IN BN position, and later was the location of the 31st RCT’s entire perimeter. It overlooked the 80th and 81st PVA Divisions’ avenue of approach leading south toward the inlet, and also provided an OP and wide field of fire. By controlling Hill 1324, the 31st RCT was able to fix the PVA forces by denying them access to that avenue of approach. Hill 1221 (K3) was the highest and dominating terrain feature for the entire Chosin Reservoir area. Originally occupied by the 5th Marines, it was occupied by PVA forces throughout the battle. It overlooked the only avenue of approach leading south. By controlling Hill 1221, the PVA forces prevented the 31st RCT from retrograding to Hagaru-ri. The hairpin turn (K4) was a sharp turn that allowed the PVA forces to ambush and destroy the 31st Medical Company and 31st Tank Company. This is where the 31st RCT was effectively defeated, and where LTC Faith was wounded.

Cover and Concealment / Observation Fields of Fire. High terrain provided cover and concealment and wide fields of fire for infantry and field artillery weapons, which provided the advantage to the PVA forces, who seized the high ground early in the battle and effectively utilized its position to attack the 31st RCT with small arms, crew served weapons, and mortars from Hill 1221. Hills occupied by PVA and winding roads prevented the 31st RCT’s AAA and FA assets from observing PVA forces and supporting the infantry battalions’ defensive perimeter. This was especially detrimental during the breakout attempt given the PVA advantage of controlling the high ground.

Avenues of Approach. Only two avenues of approach were accessible on the eastern side of the reservoir due to the mountainous terrain: the road running north to south, overseen by Hill 1324, and the road leading south from Hill 1221 toward Hagaru-ri. The roads were rough and unimproved, and contained hairpin turns. The road conditions slowed any forces traveling them and provided the PVA forces the opportunity to ambush the 31st RCT. The road leading south from Hill 1221 was the only escape route for the 31st RCT.

Analysis – Principles of Mission Command

Given the circumstances and limitations imposed upon the 31st RCT, LTC Faith was able to effectively apply the principles of mission command, ensuring mission success. He was able to quickly establish trust, provide clear commanders intent to junior leaders, exercise disciplined initiative, and accept prudent risk.

Build Cohesive Teams Through Trust. LTC Faith had established trust by leading from the front and making sound decisions under pressure, which earned him the respect of the 31st RCT Soldiers with whom he had never previously worked. His refusal to accept the Silver Star awarded to him by LTG Almond is a testament to his character and mindset as a leader. He personally lead attacks against the PVA forces whenever possible (in some cases, necessary) including the final assault of Hill 1221 and the roadblock. CPT Robert Jones of the 57th FA BN said of him, “I’d been with LTC Faith all the way through [from the inlet] and when he got hurt I felt a great loss because he was the leader. And he was the one that was very decisive.”85 It was only after LTC Faith was mortally wounded that the remaining officers and Soldiers broke ranks and fled across to frozen reservoir to the 1st Marine Division’s position. Because the Soldiers of the 31st RCT trusted him to make sound decisions, they followed his orders even, despite knowing or suspecting they would not survive the missions he asked them to execute.

Provide clear commander’s intent / Create Shared Understanding. Despite physical exhaustion and lack of leadership within the 31st RCT, LTC faith was clear enough in his intent to ensure his junior leaders and Soldiers understood the end state of all stages of the operation. He was particularly successful during the breakout and subsequent attacks on Hill 1221 and the roadblock. The most common criticism of LTC Faith’s planning is that he did not include intermediate objectives, phase lines, and other coordination measures between his units.86 However, by not incorporating these measures he actually ensured a more clear understanding of his intent.87 As previously stated, the officers and NCOs suffered high casualty rates, leaving junior NCOs and Soldiers in command of companies and platoons. These NCOs and Soldiers did not have the knowledge of operational terms and concepts such as phase lines and intermediate objectives that officers and senior NCOs were more familiar with. The use of these terms would have made it more challenging to create a shared understanding of the mission and his intended end state. LTC Faith overcame this language barrier by explaining his intent and concept of the operation in layman’s terms to ensure that the utterly exhausted Soldiers clearly understood what needed to be accomplished.

Exercise Disciplined Initiative / Accept Prudent Risk. LTC Faith frequently made command decisions without being ordered to do so, and accepted the risks associated with those decisions. Communication with his higher headquarters was virtually nonexistent for much of the battle, forcing LTC Faith to make decisions with little guidance. After the meeting with MG Barr and informed that no reinforcements were being sent, he made the decision to attempt the breakout on his own initiative.88 The decision to execute the breakout plan was extremely high-risk due to the exhaustion of the Soldiers and lack of FA, AAA, and CAS assets to assist (although, MG Barr eventually ensured CAS priority on 01 December). LTC Faith was aware that his defenses would not hold much longer; it was only a matter of time before the PVA overran their position and made its way to Hagaru-ri. By maintaining the 31st RCT’s position, the majority of his remaining Soldiers would be killed or captured by the PVA forces, and Hagaru-ri would certainly have been overrun. By retrograding to Hagaru-ri, he would ensure the survival of his remaining Soldiers and integrate with the 1st Marine Division to defend Hagaru-ri, ensuring the intent of his mission was met. He therefore accepted the risk to mission and issued the breakout order. Unbeknownst to him at the time, orders to withdraw had already been issued by both GEN MacArthur and LTG Almond. During the breakout, it became apparent that they could not advance further south without seizing Hill 1221 and destroying the roadblock, and he again made the intuitive decision to attack the PVA forces on the hill, and then personally led the attacks on both. He accepted the high risk to his forces because the convoy could not move further south under the barrage of PVA fire from those positions. Had these attacks been successful the 31st RCT may have made it to Hagaru-ri intact.

Notes

1Cleaver, Thomas Mckelvey. The Frozen Chosen: The 1st Marine Division and the Battle of the Chosin Reservoir. Oxford, UK: Osprey Publishing, a Division of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc., 2017. Kindle Edition.

2Cleaver, Thomas Mckelvey. The Frozen Chosen.

3Task Force Faith: The Story of the 31st Regimental Combat Team. Directed by Julie Precious. Produced by Vincent Gaines and Julie Precious. January 01, 2012. Accessed April 13, 2018.

4Task Force Faith: The Story of the 31st Regimental Combat Team. Directed by Julie Precious.

5Task Force Faith: The Story of the 31st Regimental Combat Team. Directed by Julie Precious.

6Task Force Faith: The Story of the 31st Regimental Combat Team. Directed by Julie Precious.

7Task Force Faith: The Story of the 31st Regimental Combat Team. Directed by Julie Precious.

8Cleaver, Thomas Mckelvey. The Frozen Chosen.

9Task Force Faith: The Story of the 31st Regimental Combat Team. Directed by Julie Precious.

10Berquist, Paul T. Organizational Leadership in Crisis: The 31st Regimental Combat Team at Chosin Reservoir, Korea, 24 November-2 December 1950. 2014. Accessed April 14, 2018. Kindle Edition.

11Task Force Faith: The Story of the 31st Regimental Combat Team. Directed by Julie Precious.

12Berquist, Paul T. Organizational Leadership in Crisis

13Berquist, Paul T. Organizational Leadership in Crisis

14Berquist, Paul T. Organizational Leadership in Crisis

15Task Force Faith: The Story of the 31st Regimental Combat Team. Directed by Julie Precious.

16Berquist, Paul T. Organizational Leadership in Crisis

17Task Force Faith: The Story of the 31st Regimental Combat Team. Directed by Julie Precious.

18Berquist, Paul T. Organizational Leadership in Crisis

19Task Force Faith: The Story of the 31st Regimental Combat Team. Directed by Julie Precious.

20Berquist, Paul T. Organizational Leadership in Crisis

21Berquist, Paul T. Organizational Leadership in Crisis

22Task Force Faith: The Story of the 31st Regimental Combat Team. Directed by Julie Precious.

23Appleman, Roy E. East of Chosin: Entrapment and Breakout in Korea, 1950. College Station: Texas A & M University Press, 1991. Kindle Edition.

24Appleman, Roy E. East of Chosin: Entrapment and Breakout in Korea, 1950.

25Appleman, Roy E. East of Chosin: Entrapment and Breakout in Korea, 1950.

26Appleman, Roy E. East of Chosin: Entrapment and Breakout in Korea, 1950.

27Appleman, Roy E. East of Chosin: Entrapment and Breakout in Korea, 1950.

28Berquist, Paul T. Organizational Leadership in Crisis

29Task Force Faith: The Story of the 31st Regimental Combat Team. Directed by Julie Precious.

30Task Force Faith: The Story of the 31st Regimental Combat Team. Directed by Julie Precious.

31Task Force Faith: The Story of the 31st Regimental Combat Team. Directed by Julie Precious.

32Berquist, Paul T. Organizational Leadership in Crisis

33Task Force Faith: The Story of the 31st Regimental Combat Team. Directed by Julie Precious.

34Berquist, Paul T. Organizational Leadership in Crisis

35Task Force Faith: The Story of the 31st Regimental Combat Team. Directed by Julie Precious.

36Task Force Faith: The Story of the 31st Regimental Combat Team. Directed by Julie Precious.

37Task Force Faith: The Story of the 31st Regimental Combat Team. Directed by Julie Precious.

38Task Force Faith: The Story of the 31st Regimental Combat Team. Directed by Julie Precious.

39Task Force Faith: The Story of the 31st Regimental Combat Team. Directed by Julie Precious.

40Task Force Faith: The Story of the 31st Regimental Combat Team. Directed by Julie Precious.

41Task Force Faith: The Story of the 31st Regimental Combat Team. Directed by Julie Precious.

42Task Force Faith: The Story of the 31st Regimental Combat Team. Directed by Julie Precious.

43Task Force Faith: The Story of the 31st Regimental Combat Team. Directed by Julie Precious.

44Task Force Faith: The Story of the 31st Regimental Combat Team. Directed by Julie Precious.

45Task Force Faith: The Story of the 31st Regimental Combat Team. Directed by Julie Precious.

46Task Force Faith: The Story of the 31st Regimental Combat Team. Directed by Julie Precious.

47Task Force Faith: The Story of the 31st Regimental Combat Team. Directed by Julie Precious.

48Task Force Faith: The Story of the 31st Regimental Combat Team. Directed by Julie Precious.

49Cleaver, Thomas Mckelvey. The Frozen Chosen.

50Task Force Faith: The Story of the 31st Regimental Combat Team. Directed by Julie Precious.

51Task Force Faith: The Story of the 31st Regimental Combat Team. Directed by Julie Precious.

52Appleman, Roy E. East of Chosin: Entrapment and Breakout in Korea, 1950.

53Appleman, Roy E. East of Chosin: Entrapment and Breakout in Korea, 1950.

54Task Force Faith: The Story of the 31st Regimental Combat Team. Directed by Julie Precious.

55Task Force Faith: The Story of the 31st Regimental Combat Team. Directed by Julie Precious.

56Task Force Faith: The Story of the 31st Regimental Combat Team. Directed by Julie Precious.

57Task Force Faith: The Story of the 31st Regimental Combat Team. Directed by Julie Precious.

58Task Force Faith: The Story of the 31st Regimental Combat Team. Directed by Julie Precious.

59Task Force Faith: The Story of the 31st Regimental Combat Team. Directed by Julie Precious.

60Task Force Faith: The Story of the 31st Regimental Combat Team. Directed by Julie Precious.

61Task Force Faith: The Story of the 31st Regimental Combat Team. Directed by Julie Precious.

62Task Force Faith: The Story of the 31st Regimental Combat Team. Directed by Julie Precious.

63Appleman, Roy E. East of Chosin: Entrapment and Breakout in Korea, 1950.

64Task Force Faith: The Story of the 31st Regimental Combat Team. Directed by Julie Precious.

65Task Force Faith: The Story of the 31st Regimental Combat Team. Directed by Julie Precious.

66Task Force Faith: The Story of the 31st Regimental Combat Team. Directed by Julie Precious.

67Task Force Faith: The Story of the 31st Regimental Combat Team. Directed by Julie Precious.

68Task Force Faith: The Story of the 31st Regimental Combat Team. Directed by Julie Precious.

69Task Force Faith: The Story of the 31st Regimental Combat Team. Directed by Julie Precious.

70Cleaver, Thomas Mckelvey. The Frozen Chosen.

71Task Force Faith: The Story of the 31st Regimental Combat Team. Directed by Julie Precious.

72Cleaver, Thomas Mckelvey. The Frozen Chosen.

73Task Force Faith: The Story of the 31st Regimental Combat Team. Directed by Julie Precious.

74Cleaver, Thomas Mckelvey. The Frozen Chosen.

75Berquist, Paul T. Organizational Leadership in Crisis: The 31st Regimental Combat Team at Chosin Reservoir, Korea, 24 November-2 December 1950. 2014. Accessed April 14, 2018. Kindle Edition.

76Berquist, Paul T. Organizational Leadership in Crisis

77Berquist, Paul T. Organizational Leadership in Crisis

78Berquist, Paul T. Organizational Leadership in Crisis

79Task Force Faith: The Story of the 31st Regimental Combat Team. Directed by Julie Precious.

80Task Force Faith: The Story of the 31st Regimental Combat Team. Directed by Julie Precious.

81Task Force Faith: The Story of the 31st Regimental Combat Team. Directed by Julie Precious.

82Berquist, Paul T. Organizational Leadership in Crisis

83Task Force Faith: The Story of the 31st Regimental Combat Team. Directed by Julie Precious.

84Berquist, Paul T. Organizational Leadership in Crisis

85Task Force Faith: The Story of the 31st Regimental Combat Team. Directed by Julie Precious.

86Berquist, Paul T. Organizational Leadership in Crisis

87Berquist, Paul T. Organizational Leadership in Crisis

88Berquist, Paul T. Organizational Leadership in Crisis

Bibliography

Appleman, Roy E. East of Chosin: Entrapment and Breakout in Korea, 1950. College Station: Texas A & M University Press, 1991. Kindle Edition.

Berquist, Paul T. Organizational Leadership in Crisis: The 31st Regimental Combat Team at Chosin Reservoir, Korea, 24 November-2 December 1950. 2014. Accessed April 14, 2018. Kindle Edition.

Cleaver, Thomas Mckelvey. The Frozen Chosen: The 1st Marine Division and the Battle of the Chosin Reservoir. Oxford, UK: Osprey Publishing, a Division of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc., 2017. Kindle Edition

Task Force Faith: The Story of the 31st Regimental Combat Team. Directed by Julie Precious. Produced by Vincent Gaines and Julie Precious. January 01, 2012. Accessed April 13, 2018.

Cite This Work

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing stye below:

Related Services

View allRelated Content

All TagsContent relating to: "Military"

The term Military is often referred to as the armed forces, of which are the organisations employed to protect the country that they serve. Military personnel are highly trained, highly equipped individuals that are committed to serving their country in any way necessary.

Related Articles

DMCA / Removal Request

If you are the original writer of this dissertation and no longer wish to have your work published on the UKDiss.com website then please: