Challenges of Local Biodiversity Policies Implementation

Info: 9154 words (37 pages) Dissertation

Published: 10th Dec 2019

Tagged: BiologyEarth Sciences

CHAPTER THREE – OVERVIEW OF CASE STUDIES

- Introduction

Biodiversity is a topical issue in recent times across the world because of the increasing pressure on the environment. Human activities and natural processes have immense implications on the amount, variety and variability of natural resources. Therefore, there is need for conscious and joined-up effort to address issues of loss of biodiversity at all levels.

The state, trend and threats to biodiversity vary The management of resources in the environment is becoming increasingly important in recent decades. This scenario is complicated by human induced activities and environmental challenges which stretch the utilisation and carrying capacity of these resources resulting in global decline in biodiversity. This research suggests a holistic approach and assessment to local biodiversity policy implementation in line with other overarching policies and strategies.

The research discussed the main challenges of local biodiversity policies implementation in Newfoundland and Labrador which are uncoordinated policies and improperly monitored policy targets, initiatives and programmes. It will apply the concept of planetary boundaries to articulate effective interaction and efficient interdependence of biodiversity management systems. Finally, the research will identify policy gaps and suggest best practices to address the main challenges of local biodiversity policy implementation. This research will support the debate for relevant theories and appropriate methodology in biodiversity management research. according to differs factors that influence resultant environmental dynamics. Furthermore, there are differential responses to these environmental challenges, thereby dictating the precautionary approach to biodiversity conservation. This is further amplified by a comparative account of the biodiversity conservation approaches in the United Kingdom and in Newfoundland and Labrador province, Canada. The historical and contextual perspectives of biodiversity and related policy formulation, implementation and review processes and issues in the United Kingdom are also further discussed below. Consequently, biodiversity and policy formulation, implementation and review issues are highlighted in a view to present the existing policy initiation, implementation and evaluation in these case studies. Aside from these, best practices in biodiversity conservation and policy implementation and evaluation in the United Kingdom are identified with a view to replicate them in Newfoundland and Labrador province.

Biodiversity reflects the number and variety of all life on Earth which comprises all species of animals and plants, and the natural systems that support them. Biodiversity is important because it provides the life support system for all life on earth besides vital benefits for humans from the natural environment. It contributes to the human economy, health and wellbeing, and it enriches peoples’ lives. Biodiversity is a topical issue in recent times across the world because of the increasing pressure on the environment (Joint Nature Conservation Committee, 2016b).

- The European and International Context

At the international level, biodiversity involves agreed conventions and legislation, an ecosystem approach, focus on overseas territories and dependencies, assessing global impacts and operational instruments (The Intergovernmental Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services – IPBES). The EU’s environmental legislation is complemented by a variety of other non-binding policy instruments such as strategies, programmes and action plans to address the wider use of terrestrial and marine resources.

- The EU Biodiversity Strategy

In May 2011, the European Commission ratified a new approach to halt the loss of biodiversity and ecosystem services in the EU by 2020, in line with the Convention on Biological Diversity’s (CBD) commitments in 2010. The strategy includes a new vision stating that “by 2050, European Union biodiversity and the ecosystem services it provides – its natural capital – are protected, valued and appropriately restored for biodiversity’s intrinsic value and for their essential contribution to human wellbeing and economic prosperity, and so that catastrophic changes caused by the loss of biodiversity are avoided” (European Commission, 2016).

The strategy contains six targets and 20 actions. The six targets cover:

- full implementation of EU nature legislation to protect biodiversity;

- better protection for ecosystems, and more use of green infrastructure;

- more sustainable agriculture and forestry;

- better management of fish stocks;

- tighter controls on invasive alien species; and

- a bigger EU contribution to averting global biodiversity loss.

The agenda for the adoption of the new EU Biodiversity Strategy by the Environment Council in June 2011 was initiated by the failure to meet the 2010 biodiversity target set in 2001. The new EU Biodiversity Strategy main targets, as listed above, are aimed at protecting and contributing to avert biodiversity loss.

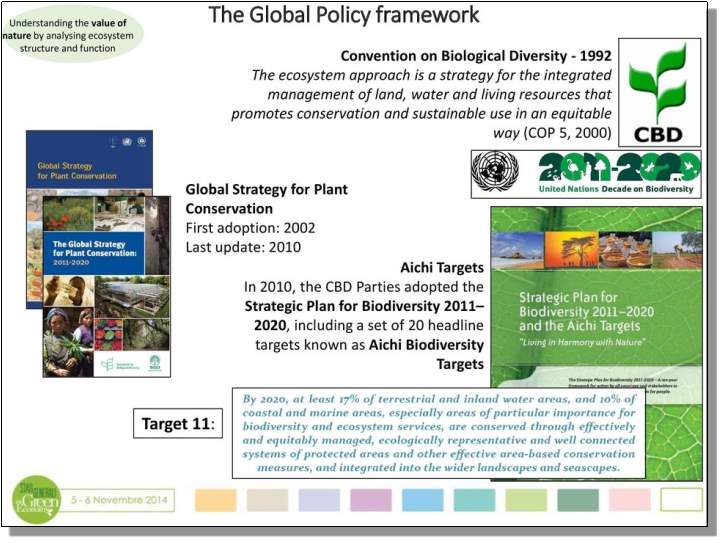

The EU biodiversity strategy was drafted by the European Commission based on the Global Policy Framework as shown in Figure 3.1. It is also aimed to promote

Figure 3.1 The Global Policy Framework

Source:http://www.bing.com/images/search?view=detailV2&ccid=kTdoW%2BWh&id=4FBFB57FE6549F60EE081F69E16373B0C29A14CB&thid=OIP.kTdoWWh3Pmsw6WoRACeQEsDf&q=EU+biodiversity+strategy+2011&simid=608037031199248283&selectedindex=7&mode=overlay&first=1

conserving biodiversity within its own territory and it is also the avenue through which the EU intends to fulfil its commitment as a signatory to the international agreement on global biodiversity target. A new set of biodiversity targets (the Aichi targets and the Strategic Plan 2011 – 2050 were agreed at the CBD 10th Conference of the Parties in Nagoya, Japan in 2010 (JNCC, 2014). The Aichi Target 11 is relevant to this research on biodiversity and protected areas especially as it relates to land use management to meet urban and regional development needs.

A policy instrument which provides the framework to manage the use of land and to implement the EU Biodiversity Strategy in accordance with the Aichi Targets is the EU Environmental Action Programme. This is the framework for policy-making in the Environmental Action Plan (EAP). This plan period is from 2013 – 2020 and it has nine priority objectives and three key areas (to protect and enhance nature and biodiversity; boost resource efficient, sustainable growth; and to improve environmental links with health). The goals of the EAP are achieved by better implementation of existing legislation, by enhancing knowledge, through larger investments and full integration of environmental issues into policy. The programme intends to make EU cities more sustainable and it is applied across boundaries on a global scale. The EU EAP is a top environmental priority which will be regularly monitored and will be revaluated in 2020 (JNCC, 2014).

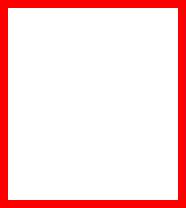

There is a reporting obligation under the Nature Directives (Birds and Habitats). The European Commission requires the production of reports to present progress towards meeting the objectives of the Birds and Habitats Directives and the conservation trend and status of species and habitats listed. The goal of conserving biodiversity within its own territory is also the avenue through which the EU intends to fulfil its commitment as a signatory to the international agreement on global biodiversity target. A new set of biodiversity targets (the Aichi targets and the Strategic Plan 2011 – 2050 were agreed at the CBD 10th Conference of the Parties in Nagoya, Japan in 2010 (JNCC, 2014). The Aichi Target 11 is relevant to this research on biodiversity and protected areas especially as it relates to land use management to meet urban and regional development needs. Habitats Directive is to assess the implementation of the Directives on species and habitats and the assessment is focused on outcomes. The reporting cycles are at six year intervals and three reporting rounds (1994-2000, 2001-2006 and the most recent 2007-2012) under the Habitats Directive have been produced, while the Birds Directive requires reports on the implementation of the Birds Directive every three years. There have been nine reporting rounds between 1983 – 2007. Strategically, the EAP is situated within a wider European Policy Framework which incorporates other strategies and policies at the regional (European) level, as shown below in Figure 3.2.

It is worthy to note that the reporting periods are not synchronised, making the overview of implementation of the two Directives difficult. It is important to note that the EU biodiversity policy is based on the international ecosystem approach. In addition, the conservation technique is at the centre of the United Kingdom biodiversity initiative.

Figure 3.2 European Policy Framework

Source:http://www.bing.com/images/search?view=detailV2&ccid=DjfmOpNE&id=4FBFB57FE6549F60EE08C7A81CC08FF88FC3DD9E&thid=OIP.DjfmOpNEV_VlyAQCT57IjQEsDe&q=EU+biodiversity+strategy+2011&simid=607991465884716268&selectedindex=23&mode=overlay&first=1

Source:http://www.bing.com/images/search?view=detailV2&ccid=DjfmOpNE&id=4FBFB57FE6549F60EE08C7A81CC08FF88FC3DD9E&thid=OIP.DjfmOpNEV_VlyAQCT57IjQEsDe&q=EU+biodiversity+strategy+2011&simid=607991465884716268&selectedindex=23&mode=overlay&first=1

- Biodiversity Conservation and Information System in the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom is a signatory to the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) and is committed to the biodiversity goals and targets ‘the Aichi targets’ agreed in 2010. These are set out in the Strategic Plan for Biodiversity 2011-2020. The United Kingdom is also committed to develop and use a set of indicators to report on progress towards meeting these international goals and targets (Joint Nature Conservation Committee, 2016b). There are related commitments on biodiversity made by the European Union, and the United Kingdom indicators may also be used to assess progress with these.

Generally, nature conservation tends to sustain and enrich biodiversity. UK nature conservation is driven by various policies, legislation and agreement from various stakeholders (the statutory, voluntary, academic and business sectors). The UK has demonstrated innovation and leadership through successive biodiversity strategies which take a devolved, integrated, ecosystem approach to the implementation of activities needed to address biodiversity loss (JNCC and Defra, 2012:4).

In 1994, the UK produced the first national biodiversity action plan (the United Kingdom Biodiversity Action Plan – UK BAP), based on its obligation to the Convention on Biological Diversity. However, “biodiversity policy is a devolved responsibility in the UK: England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland have each developed or are developing their own biodiversity and environmental strategies” JNCC, 2015: para.3).

The Joint Nature Conservation Committee (JNCC) organised conservation action and research in the UK and published the ‘UK Post-2010 Biodiversity Framework’. This framework incorporates the common purpose “(International/European context, facilitating and contributing to common country approaches and solutions, evidence provision and reporting)” (JNCC and Defra, 2012:2). It also includes shared priorities “(production of National Biodiversity Strategy and/or Action Plan (NBSAP)” and achieving “The 20 Aichi targets through the five strategic goals” (JNCC and Defra, 2012:2) of the four countries (England, Scotland, Northern Ireland and Wales) and was endorsed by their governments’ agencies.

The UK Post-2010 Biodiversity Framework (17 July 2012) was developed based on two major drivers: the Convention on Biological Diversity’s (CBD’s) Strategic Plan for Biodiversity 2011-2020 and its five strategic goals and the 20 ‘Aichi Biodiversity Targets’ (October 2010) and the launch of the EU Biodiversity Strategy (EUBS – May 2011). The framework is developed to demonstrate how the activities of the four countries are coordinated at a national (UK) level to achieve the ‘Aichi Biodiversity Targets’ and the aims of the EU Biodiversity Strategy. The framework identifies how the country biodiversity strategies contributes to international obligations and how to complement these strategies. This framework typifies an approach which signifies a paradigm shift towards a holistic approach to the management of the environment and to recognise the value of nature in decision-making. The implementation of the UK Post-2010 Biodiversity Framework requires operational tools in the form of biodiversity indicators to monitor and report progress on the trend and status of biodiversity in the UK.

- UK Biodiversity Indicators

The UK is a signatory to the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) commitments, goals and targets [‘the Aichi Targets’ (2010), Convention on Biological Diversity, 2017] and they are contained in the Strategic Plan for Biodiversity 2011-2020 (Convention on Biological Diversity, 2017). Consequently, there is a commitment to develop and apply a set of indicators to monitor and report on the achievement of these international goals and targets.

These indicators are designed to monitor progress in each country with the specific purpose for international reporting and were a result of consultation and agreement between the stakeholders and the administrations. Consequently, a set of 18 indicators initially developed for reporting against previous international targets has been broadened to 24 indicators (Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs, 2012). The indicators provide an adaptive and flexible framework and comparative methodologies for country reporting.

The UK Biodiversity Indicators are based on a wide variety of most robust, reliable and available data, provided by Government, research bodies, and the voluntary sector. The indicators present shifts in various aspects of biodiversity, such as the value of biodiversity, global biodiversity impact, climate change adaption and protection areas, to mention few. However, the indicators may be subject to further review as necessary (see Appendix 1 for the list and status of the UK biodiversity indicators).

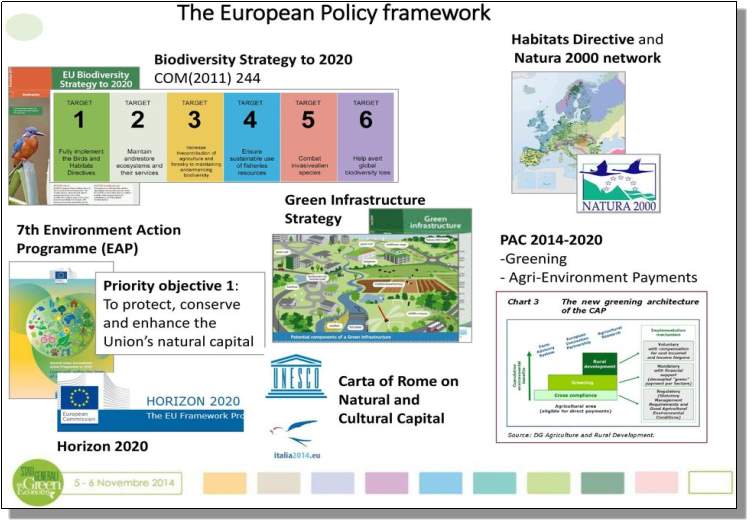

- UK Habitats and Species

There is abundance of habitats and species in the UK. The JNCC is responsible for habitat and species conservation in the UK. This is done through the provision of advice and development of surveillance and monitoring initiatives which contribute to assess the status, trends and threats of species and habitats in the countryside. Information from these initiatives are used in problem identification, prioritising conservation actions and assessing the success of conservation activities. Currently, there are 65 priority habitats in the UK (JNCC, 2016d). Similarly, there are up to 1,150 priority species in the UK as contained in the Species and Habitats Review Report, 2007 (JNCC, 2016e). At this juncture, the availability and distribution of these habitats and species are relevant to the state, trend and threat of biodiversity loss. The level of threat on species in the UK is relatively low compared to the rest of Europe, as described in Figure 3.3. This reflects the on-going nature conservation activities in the UK.

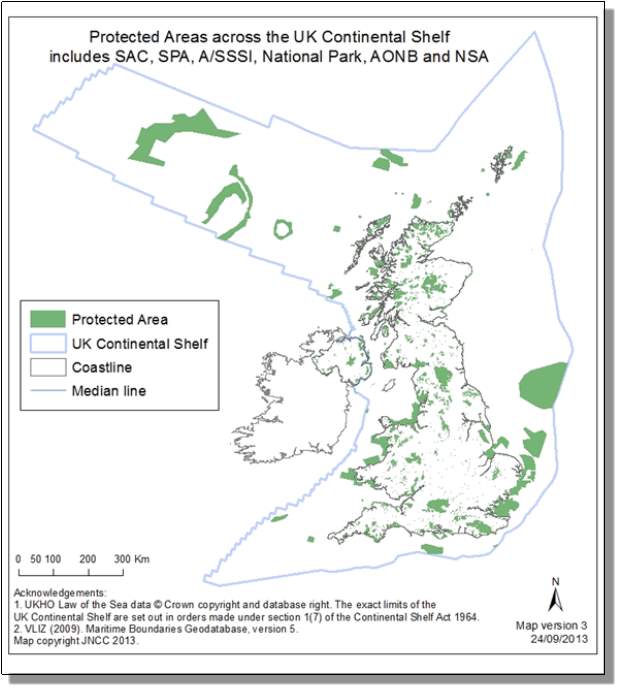

- UK Protected Sites

There are many protected areas in the UK and the JNCC designates protected areas in order to conserve and enhance habitats, earth features and species. Information is collected on designated sites to support nature conservation and explain the criteria for site selection. The UK Protected Sites are graphically presented in Figure 3.4 below.

Figure 3.3 Threatened Species in Europe

Source:http://i.dailymail.co.uk/i/pix/2015/04/13/15/2786BFBD00000578-3037027-The_UK_has_five_endangered_mammals_but_these_are_almost_exclusiv-a-91_1428935444706.jpg

Figure 3.4 Protected Sites in the UK

Source:http://www.bing.com/images/search?view=detailV2&ccid=3lhFJhCZ&id=7FE2102487170B1074B5B40CCD3577E781E1740B&thid=OIP.3lhFJhCZccdLpaY0NMlL7wENEs&q=protected+areas+uk&simid=608035755595598753&mode=overlay&first=1

Source:http://www.bing.com/images/search?view=detailV2&ccid=3lhFJhCZ&id=7FE2102487170B1074B5B40CCD3577E781E1740B&thid=OIP.3lhFJhCZccdLpaY0NMlL7wENEs&q=protected+areas+uk&simid=608035755595598753&mode=overlay&first=1

- UK Legislation

The origin of the laws and regulations applicable to biodiversity conservation and its regulation is found at global, European Union, national and sub-national levels. There are differences in nature conservation approaches due to devolution of power. The main legislation addressing nature conservation in the UK is the Wildlife and Countryside Act, 1981 (as amended). This legislation is applied with consideration for the National Planning Policy Framework.

The inception and development of biodiversity conservation is better understood through the sequence of activities overtime. A brief timeline, as presented in Appendix 2, describes and highlights the trend of activities, plans and strategies that have been incorporated since the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) in 1992 up to the publication of the UK Post-2010 Biodiversity Framework in 2012. However, the brief timeline encourages biodiversity coordination and monitoring through policy instruments to guide and direct biodiversity conservation in the UK.

- Reporting and Information Sharing

Biodiversity reporting and information sharing in the UK is conducted through a suite of information systems. The UK BAP Species and Habitat Information System provides collated information about priority species and habitat. This information base is complemented by a country-level information system which provides details of the most recent country strategies and documents. In addition, the Biodiversity Action Reporting System (BARS), a web-based information system documents action executed to achieve specific biodiversity objectives and to progress biodiversity planning, coordination of effort and meeting reporting requirements. Furthermore, the Habitat Management on the Web, is a search engine developed to provide information on management approaches to non-marine habitats in the UK for biodiversity and conservation. These information systems provide good platforms for reporting and sharing of information on biodiversity and conservation issues. They are also applied in the planning system (national planning policy framework) to devise planning instruments to direct biodiversity and nature conservation in England.

- National Planning Policy Framework

The National Planning Policy Framework sets out Government’s planning policies for England, how they should be applied and the relevant, proportionate and necessary Government requirements. The framework enhances? residents and their local planning authorities to develop local and neighbourhood plans in accordance with the communities’ needs and priorities. These efforts are geared towards the achievement of sustainable development dimensions (economic, social and environmental). The pursuit of sustainable development incorporates positive improvements in the transition from net loss of biodiversity to net gains for nature. This framework contains provisions which include conserving and enhancing the natural environment. Detailed policy directions in this regard are contained in paragraphs 109 – 125. The overarching provision is in para. 109, which states that

“the planning system should contribute to and enhance the natural and local environment by:

- protecting and enhancing valued landscapes, geological conservation interests and soils;

- recognising the wider benefits of ecosystem services;

- minimising impacts on biodiversity and providing net gains in biodiversity where possible, contributing to the Government’s commitment to halt the overall decline in biodiversity, including by establishing coherent ecological networks that are more resilient to current and future pressures;

- preventing both new and existing development from contributing to or being put at unacceptable risk from, or being adversely affected by unacceptable levels of soil, air, water or noise pollution or land instability; and

- remediating and mitigating despoiled, degraded, derelict, contaminated and unstable land, where appropriate”.

All these provisions contained in the National Planning Policy Framework are aimed at favouring sustainable development and improving the existing biodiversity infrastructure through local planning policies and partnerships.

- Strategic Biodiversity Partnership

Different strategic biodiversity partnerships exist in boroughs and counties across England. However, a relevant strategic biodiversity partnership in terms of scope and context is established within the North Northamptonshire. It was formed from the strategic partnership of neighbouring Borough and District councils. These councils are Corby Borough Council, Kettering Borough Council, Borough Council of Wellingborough and Northampton Borough Council.

The implementation instrument of the strategic biodiversity partnership is the North Northamptonshire Joint Planning Unit. The North Northamptonshire Joint Planning Unit, a local partnership of Corby, Wellingborough, Kettering and East Northamptonshire councils together with Northamptonshire County Council work together to create an overall plan for North Northamptonshire. All these borough and county councils require an operational Biodiversity Supplementary Planning Document (SPD) to execute biodiversity conservation within their areas of jurisdiction.

- Biodiversity Supplementary Planning Document (SPD)

The Biodiversity SPD is a statutory Local Development Document (LDD) prepared under the 2004 Planning and Compulsory Purchase Act (the “2004 Act”) with operational coverage of the entire Northamptonshire and adopted by the respective Local Planning Authorities as a statutory SPD. This SPD supplements policies and strategies within the North Northamptonshire Core Spatial Strategy (2008) and West Northamptonshire Joint Core Strategy Local Plan (Part 1 – 2014). It is also consistent with the draft North Northamptonshire Joint Core Strategy 2011-2031.

Each local authority has a statutory commitment to conserve biodiversity and this is addressed by incorporating nature conservation policies in Northamptonshire’s core strategies and saved policies (previous development policies) of each borough/district. The SPD aims to integrate biodiversity into the development process in order to aid the achievement of legislation and policy requirements and ensure best practice standards are met. It is applied in conjunction with the main principles of the National Planning Policy Framework, local planning policies and ecological assessment. The biodiversity policy framework described herein, reveals how well connected biodiversity concerns are enshrined in the planning system and geared towards the achievement of the overall biodiversity targets. This is evident by the articulation of biodiversity policy issues in North Northamptonshire Joint Planning Unit.

- Biodiversity Policy Cycle Issues in North Northamptonshire Joint Planning Unit

The biodiversity conservation policy issues in North Northamptonshire was initiated by a clear agenda setting based on the recognition of the EU’s failure to meet the 2010 biodiversity target set by the European Council in Gothenburg (2001), where Member States committed to halt the decline of biodiversity in the EU by 2010.

The challenge to achieve this agenda trickled down to different levels of governance and administration but geared towards the overarching agenda which is to halt the decline of biodiversity in the EU. This has shaped policy agenda setting in North Northampton Joint Planning Unit. Biodiversity policy agenda setting was initiated by the combination of intense public complaints, general biodiversity loss in both built-up and natural environment, need to be close to nature and statutory requirements, to mention few. The explanatory factors that justified this phase in the policy development process include the importance of environmental stewardship, citizens’ articulation of preference process, local governance (interaction and participation) and Northamptonshire’s responsibilities towards its residents.

Policy formulation

The legislative instruments establishing biodiversity supplementary planning documents are the 2004 Planning and Compulsory Purchase Act (the “2004 Act”) and Town and Country Planning (Local Planning) (England) Regulations 2012 (Statutory Instrument 2012 No. 767). Germane to this, local planning authority was responsible for formulating a supplementary planning document for biodiversity policy.

The four local planning authorities established the North Northamptonshire Joint Planning Unit to facilitate the formulation, implementation and review of biodiversity policy. North Northamptonshire Joint Planning Unit and stakeholders have identified and analysed available policy options, considered existing environmental regulations and analysed the impacts of policy options to formulate biodiversity policy goals to improve biodiversity and quality of life. Policy objectives (plans, strategies and programs) were drafted to address biodiversity loss.

The driving factors for this policy phase include setting goals, decision to ‘act’, estimating risks, cost and benefits, choice of available policy instruments, meeting environmental and biodiversity standards, political interests and agenda, while the explanatory factors justifying this phase were to deliver a ‘public good’ (improved biodiversity and good environmental stewardship) and to perform governmental duties.

Decision making / Legislation

Four local planning authorities in Northamptonshire formed a Joint Planning Unit to address planning related issues within North Northamptonshire area. This led to draft a Supplementary Planning Document (SPD) on biodiversity for the planning area. The SPD on biodiversity was drafted in line with Northamptonshire Biodiversity Action Plan.

The decision to act was influenced by various proposals for solutions, such as the adoption of national biodiversity policy, or delegating biodiversity management duties to local planning authorities. The draft SPD on biodiversity was presented, debated and adopted by various Councils. The North Northamptonshire’s Supplementary Planning Document on Biodiversity was adopted in July 2011.

The driving and explanatory factors that justified this policy phase were Government’s constitutional duties, level of rational decision making, citizen acceptance and participation, and political objectivity and transparency.

Policy Implementation

The North Northamptonshire Joint Planning Unit is the leading institution for the formulation, implementation and monitoring of the North Northamptonshire biodiversity policy; other stakeholders were actively involved at various levels. The implementation plan for North Northamptonshire biodiversity policy utilised existing Northamptonshire Biodiversity Action Plan. The policy was planned to be reviewed as need arises through the consultation of the public and direction from the North Northamptonshire Joint Planning Unit and other stakeholders. The implementation plan focussed on financing, responsibilities, roles and specific biodiversity conservation programs and activities and specified actors, process and outcomes. Policy implementation was more regulatory (command-and-control) and informative at the local level than at the regional and national levels.

– Financing

The four local planning authorities in the North Northamptonshire Joint Planning Unit provide larger proportion of the funds (technical personnel, money and other resources) to implement the policy, while the rest were contributed through community engagements, private sector sponsorships and participations from Northamptonshire Biodiversity Records Centre, Northamptonshire Biodiversity Partnerships and others.

– Roles and Responsibilities of Executing Institutions

The roles and responsibilities of the executing institutions varied accordingly for the achievement of policy objectives. North Northamptonshire Joint Planning Unit is the leading institution coordinating strategic visioning and implementing biodiversity programs, public enlightenment, and technical and financial support. Northamptonshire Biodiversity Partnership and Northamptonshire Biodiversity Records Centre provide advisory and advocacy, community awareness and involvement, planning and policy, and data, monitoring and evidence.

– Policy Instruments

Biodiversity policy applied a combination of policy instruments to set agenda, formulate, implement and monitor biodiversity conservation policy. These policy instruments were a) regulatory and command-and-control – this involved the application of existing legislations at local and regional levels; b) public outreach and education – this involved the use of the mass media to disseminate information for public awareness and engagement. The driving and explanatory factors for this policy phase include intention for positive change, choice of policy instruments, addressing biodiversity conservation issues, linkage between policy programs and policy instruments, identifying ‘actors’ and their roles and meeting budgetary and statutory requirements.

Policy monitoring and evaluation

The North Northamptonshire Joint Planning Unit, in conjunction with Northamptonshire Biodiversity Records Centre, Northamptonshire Biodiversity Partnership and other local partnerships, monitor the biodiversity conservation policies focussing on evidence gathering and compliance, while actual evaluation was conducted by the North Northamptonshire Joint Planning Unit through annual monitoring reports.

Policy monitoring was evidence based (policy focus areas), while policy evaluation was outcome-based using indicators. The policy focus areas used for policy monitoring include: levels of service, capacity development, legislation and regulation, information, education and communication, financing and cost recovery, research and development and monitoring and evaluation. The indicators include: area of coverage, measuring effectiveness, efficiency, impacts (social, ecological and economic), compliance (number of violators), identify policy gaps and produce quarterly and annual monitoring and evaluation reports. This involved developing appropriate indicators for each policy focus areas. These indicators formed the basis for evaluating policy impacts in order to reassess policy goals and objectives.

- The Northamptonshire Biodiversity Records Centre (NBRC)

Northamptonshire Biodiversity Records Centre is the county’s biological and geological information centre. It was created in 2006 with support from statutory and non-governmental organisations. Today, NBRC provides access to information about species, habitats and designated wildlife and geological sites for public, research and commercial users. The data NBRC holds originate from sources including local voluntary recorders and various organisations. The NBRC encourages biological recording in all its forms, promote The Northamptonshire NNJU’s need for biodiversity information in decision making in relation to conservation, sustainable development and natural capital stewardship for the benefit of all.

NBRC is run on a non-profit basis and hosted by the Wildlife Trust for Bedfordshire, Cambridgeshire and Northamptonshire. These operations are overseen and guided by a Steering Group comprising representatives of a range of local stakeholder groups with varied interests in different aspects of biological recording, data curation and biodiversity information use across the county.

The existing framework for biodiversity conservation in the UK as presented above, are developed to address the failures of the past biodiversity conservation pursuits, to meet both local and international targets and to provide a foundation to build upon for the future. The UK biodiversity conservation framework connects various actions, policies, strategies by different units at various levels, with different roles in coordination to implementation. The UK biodiversity conservation framework exhibits best practices that can be replicated elsewhere. However, there is need for improvement in agenda setting, formulation and review of goals and objectives, implementation and information collection and sharing to reflect biodiversity conservation needs, changing the biodiversity conservation paradigm, or environmental resource and management practices.

- Rationale for a Biodiversity Conservation and Information System in Newfoundland and Labrador

Extreme environmental change presents ecological concerns to the people, such as the disruption of natural processes through ecosystem services – air and water purification, natural resource production, and other benefits to humanity. Therefore, it requires management and policy responses. “Humans are rapidly altering the environment of many species, reducing range size and habitat quality and altering ecological processes” (Biodiversity Research Centre, 2017). Furthermore, “the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment shows that human actions often lead to irreversible losses in terms of diversity of life on Earth and these losses have been more rapid in the past 50 years than ever before in human history” (Greenfacts, 2016b).

Historically, environmental concerns in Canada have been addressed through different policy (procedural, substantive and institutional) means. This has influenced the availability of policy instruments and policy considerations for choosing implementation tools. It started at the beginning of the 1970s with the establishment of the basic institutional tools for policy implementation such as departments and ministries of the environment. Subsequently, this progressed by legislative frameworks for applying procedural and substantive instruments. However, there has been a paradigm shift from substantive policies to procedural and institutional policies. Hence, the development of the Canadian Biodiversity Strategy to address the trend and status of biodiversity loss and to meet local and international targets.

- Canadian Biodiversity Conservation

The Canadian Biodiversity Strategy is a policy instrument developed as a response to the commitment to the CBD, and is designed to meet local and international targets. The Canadian Biodiversity Strategy aims to achieve five main goals, as follows:

- to achieve sustainable conservation of biodiversity and use of biological resources;

- to improve the understanding of ecosystems and increase resource management capacity;

- to promote an understanding of the need for sustainable conservation of biodiversity and use of biological resources;

- to develop incentives and legislation that support sustainable conservation of biodiversity and use of biological resources; and

- to collaborate with other countries for sustainable conservation of biodiversity and use of biological resources and equitable share of benefits from the utilization of genetic resources.

These are the overarching goals at the national level in Canada. Other biodiversity frameworks, sub-national biodiversity strategies, local strategies, actions and initiatives at different jurisdictions are geared towards the achievement of these overarching goals. The Canadian Biodiversity Strategy is operationalised through the Biodiversity Outcome Framework. The Canadian Biodiversity Outcomes Framework attempts to prescribe how the overarching goals of the Canadian Biodiversity Strategy can be met. This framework, specifies the steps and activities to achieve the aims and objectives of the national biodiversity strategy; it aims to complement, advance, identify and connect “current and future priorities; endeavours to engage Canadians in planning and implementation and to report on progress; and highlights and guides progress towards Canada’s Biodiversity Outcomes, as shown in Figure 2.1.

Furthermore, according to the agreement and commitment under the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), the 13 provinces and territories in Canada are required to develop their sub-national biodiversity strategies. The sub-national biodiversity strategies are meant to be prepared at the provincial and territorial levels and these sub-national strategies are intended to operationalise and complement the national biodiversity strategy. However, all the provinces and territories have not met this requirement. Precisely, Newfoundland and Labrador province has not met this requirement.

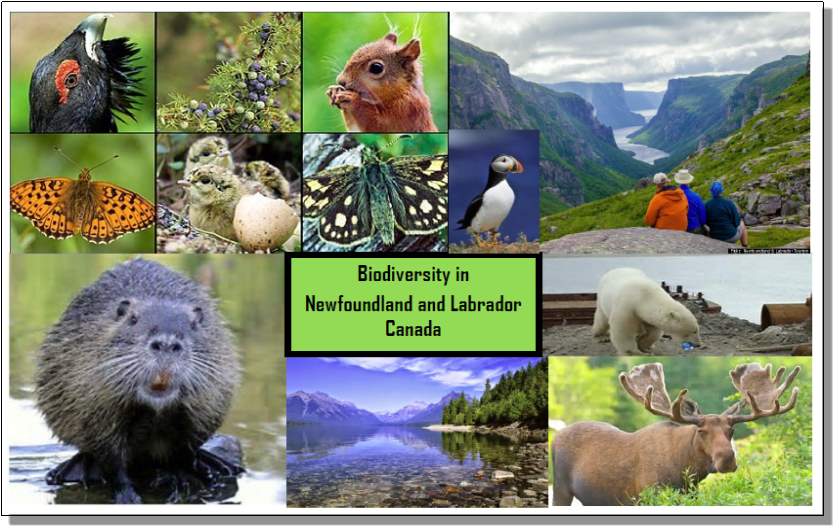

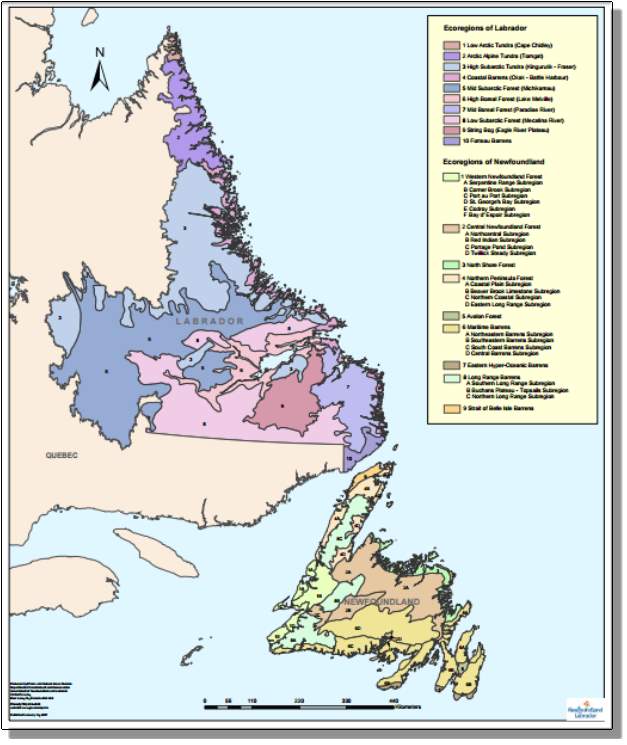

The Province of Newfoundland and Labrador has not developed a sub-national biodiversity strategy, but attempts to achieve the goals of the Canadian Biodiversity Strategy through a suite of policies, strategies and plans. “The Canadian Biodiversity Strategy has been integrated into many provincial planning processes in Newfoundland and Labrador, such as development of a provincial sustainable forest management strategy, and protected areas planning. The suite of provincial planning processes used to integrate biodiversity also include the Wildlife Biodiversity Monitoring, Exotic and Alien Invasive Species, Ecosystem Status and Trends Reports, Wildlife Diseases and Rare Plants. The Endangered Species and Biodiversity Section of the Wildlife Division implements the strategy within Newfoundland and Labrador” (Newfoundland and Labrador province, 2017). Figure 3.5 is a representation of the array of biodiversity assets in Newfoundland and Labrador province, Canada. A brief discussion of the suite of provincial planning processes will present a clear understanding of the biodiversity conservation in Newfoundland and Labrador (NL).

Figure 3.5 Biodiversity in Newfoundland and Labrador Province

Source: Figure compiled by the author using information from sources (https://www.google.ca/search?q=biodiversity+in+ Newfoundland+and+Labrador&rlz=1C1GGRV_enCA750CA750&source=lnms&tbm=isch&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwixqc7Jh8vUAhVBdz4KHUMGC3UQ_AUICigB&biw=1249&bih=1238#imgdii=zppl6MKgaPEAIM:&imgrc=TDIRoxt0fdI6NM:).

The Wildlife Biodiversity Monitoring is a voluntary based program which involves reporting the sighting of the listed species (Dragonfly and Damselfly, Butterfly) and incidental sightings (Newfoundland Marten, Short-eared Owl, Wolverine, FrogWatch, PlantWatch and WormWatch). This program provides information to monitor and protect NL’s biodiversity and wildlife resources.

The Exotic and Alien Invasive Species, under the Invasive Alien Species Partnership Program, provides means of educating the public and investigating the invasive alien species issues in NL. This is supported by legislation review of how to protect NL province and prevent the introduction of species from other provinces and territories within Canada and from outside Canada.

Ecosystem Status and Trends Reports aim to contribute towards maintaining healthy and diverse ecosystems. They also enhance the collation of information to assess the state of the ecosystems. The Ecosystem Status and Trends Reports provide science-based information on the status and trends of Canada’s ecosystems; ecosystem-based information for articulating the national biodiversity agenda; means of communicating the importance of healthy ecosystems; and baseline information for the status and trends section of the 4th National Report to the CBD. The Ecosystem Status and Trends Reports contain an assessment which provides an “integrated assessment of current status, emerging trends and significant stressors of Canada’s ecosystems. It also proposes a new and ongoing system for ecosystem monitoring and status and trends reporting, providing policy-makers with the detailed assessments required to develop policy and alert the public to ecosystem changes of concern” (The Government of Newfoundland and Labrador, 2017b). This is a laudable goal but how well is it achieved?

Newfoundland and Labrador is endowed with rich wildlife and plant species, of which many need assistance to survive. “The Wildlife Division coordinates the assessment and listing of species at risk, and develops recovery and management plans, monitoring programs, and research projects to promote their conservation” (The Government of Newfoundland and Labrador, 2017c). The American marten, Long’s braya and Red Crossbill are part of NL’s landscape and are regarded as Species at Risk. These species are safeguarded by the Species at Risk Policy which ensures that no native species are extinct as a result of human activity or interference. In addition, NL’s Endangered Species Act (2004) provides legislative provision for special protection of endangered, threatened, or vulnerable plant and animal species, with the exception of marine fish, bacteria and viruses in NL province. The Endangered Species Act contributes towards NL’s commitment under the National Accord for the Protection of Species at Risk. Similarly, protective measures are applied in the form of terrestrial and marine protected areas and supported by the Protected Areas Strategy in NL.

- Protected Areas Strategy

The Protected Areas Strategy aims to manage the province’s special natural heritage (protected area network) in healthy diversity for present and future generations for sustainable, viable resource-based economy. The Protected Areas Strategy’s framework is focussed on scientific research, sound conservation practices and the understanding of the processes of ecological systems (The Government of Newfoundland and Labrador, 2017e).

The Protected Areas Strategy was developed to conserve and safeguard unique aspects of the diverse natural heritage for the present and future generations. In 2004, a total of 55 provincial protected areas and 8 federal protected areas were identified, designated and managed to pursue the Aichi (2010) Biodiversity Target to protect a minimum of 17% of its land and inland waters by 2020. Newfoundland and Labrador province’s terrestrial protected areas (provincial and federal) account for only 4.6% of the land in NL province while Canada’s national average was 10% as at 2011. The rate of establishing protected areas has diminished over time.

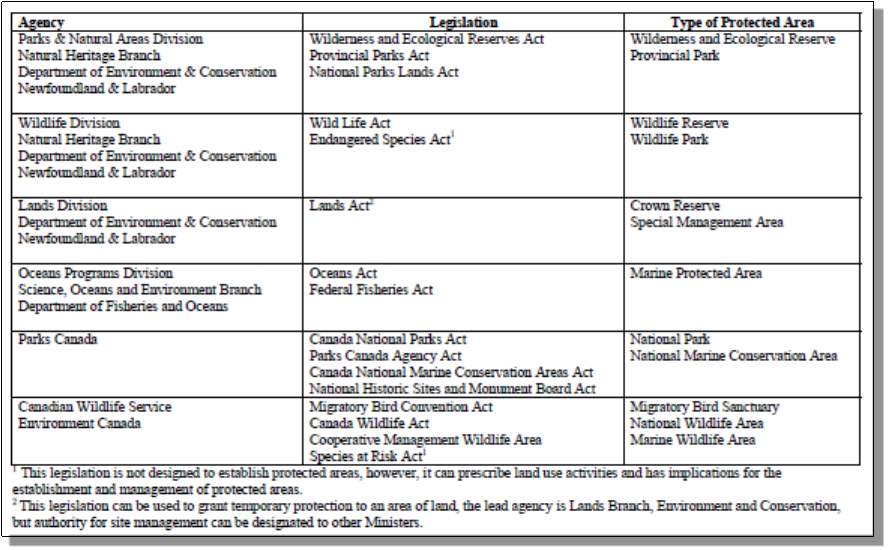

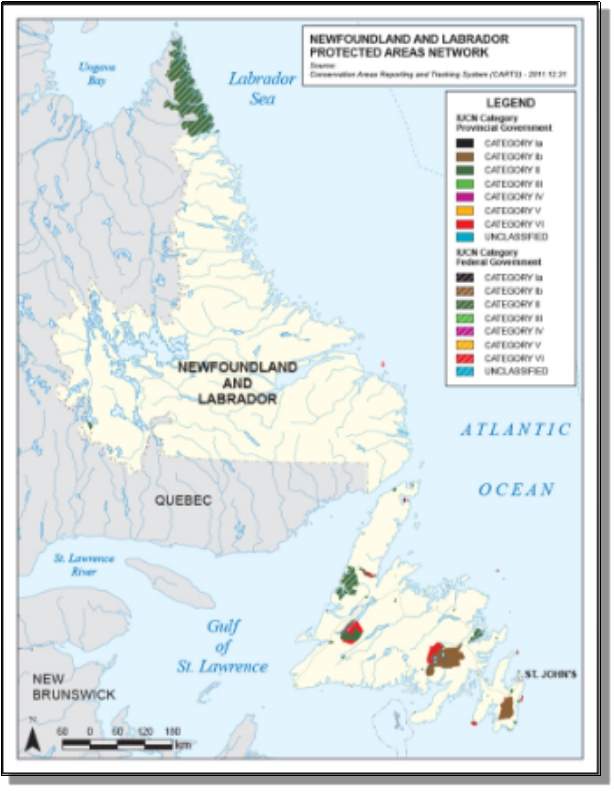

Protected Areas in Newfoundland and Labrador are divided in two categories – Provincial Protected Areas and Federal Protected Areas. However, there are “six types under provincial jurisdiction and seven under federal jurisdiction” (The Government of Newfoundland and Labrador Province, 2017d: para.1), as presented in Tables 3.1 and 3.2 below. There are 63 terrestrial protected areas covering about 18,405km2(4.52% of the Province area) and the National Protected Land Average is 8.52% as at Nov. 2003 (The Government of Newfoundland and Labrador Province, 2017d). These protected areas are created and maintained for biodiversity conservation, ecotourism, scientific research and purposes.

Table 3.1 Protected Areas in Newfoundland and Labrador

Source: The Government of Newfoundland and Labrador (2017e)

Figure 3.6 Location of Protected Areas in Newfoundland and Labrador

Source:https://ca.images.search.yahoo.com/yhs/search;_ylt=A0LEVu9NqCdZXmcA5OsXFwx.?p=protected+areas+in+newfoundland+and+labrador&fr=yhs-blp-default&fr2=piv-web&hspart=blp&hsimp=yhs-default&type=hmp_996_692_0#id=20&iurl=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.ec.gc.ca%2Fap-pa%2F8EF4F871-F880-4A6E-BD75-6585F21913FD%2Fapp_map10_eng.jpg&action=click

Table 3.2 Type and Size of Protected Areas in Newfoundland and Labrador

| Jurisdiction | Type of Protected Area | Number | Area | % | % | % |

| (km2) | Island | Labrador | Province | |||

| Protected(b) | Protected (b) | Protected (b) | ||||

| Provincial | Wilderness Reserves | 2 | 3,965 | 3.56% | 0.00% | 0.98% |

| Ecological Reserves | 16 | 910 | 0.74% | 0.03% | 0.22% | |

| Provincial Parks | 31 | 211 | 0.18% | 0.00% | 0.05% | |

| Wildlife Parks | 1 | 15 | 0.01% | 0.00% | 0.00% | |

| Wildlife Reserves (a) | 3 | 1,183 | 1.06% | 0.00% | 0.29% | |

| Public Reserves(a) | 1 | 178 | 0.16% | 0.00% | 0.04% | |

| Development Control Area | 1 | 1 | 0.00% | 0.00% | 0.00% | |

| Federal | National Parks | 3 | 11,906 | 1.98% | 3.30% | 2.93% |

| National Historic Sites | 2 | 37 | 0.03% | 0.00% | 0.01% | |

| Migratory Bird Sanctuaries | 3 | 0 | 0.00% | 0.00% | 0.00% | |

| Total Land Protected (NL) | 63 | 18,405 | 7.72% | 3.33% | 4.52% | |

| Marine = 162km2 (Ecological Reserves and Migratory Bird Sanctuaries) | ||||||

| National Protected Land Average (Canada, Nov. 2003) | 8.52% | |||||

| (a) Mineral exploration is allowed under permit | ||||||

| (b) Based on Island area of 111,390 km2 and Labrador area of 294,330 km2 | ||||||

| Source: The Government of Newfoundland and Labrador (2017d) | ||||||

research, recreational and educational purposes. Figure 3.6 shows the location and distribution of these protected areas in NL province, while Tables 3.1 and 3.2 present more details on responsible agency, relevant legislation and type of protected areas and statistics on the protected areas. These protected areas fall under one of the following pieces of legislation: Provincial Parks Act, Wilderness and Ecological Reserves Act, Wildlife Act and Lands Act, as shown in Table 3.1 below. These legislations enhance the administration and enforcement of control in these protected areas. The success of protected areas enhanced the establishment of ecoregions based on natural endowment the protected areas constitute the ecoregions.

Ecoregions are natural regions because they are identified by their distinctive, peculiar vegetation and soil development and are defined by local climate and geology, but they may differ in plants, landscapes, geology, and other features. 19 ecoregions (9 in Newfoundland and 10 in Labrador) and 35 subregions – ecodistricts (The Government of Newfoundland and Labrador, 2017f).

These province’s ecoregions and subregions are natural habitat to “1,406 known species of vascular plants, 13 indigenous mammals in Newfoundland and 37 indigenous mammals in Labrador, and 73 species of birds” (The Government of Newfoundland and Labrador, 2017f). Figure 3.7 presents more details about the location and distribution of ecoregions in Newfoundland and Labrador. The province’s latitudinal position and aerial coverage provide the northern or southern limits for many plant and animal species. Therefore, the designation of present and future protected areas is to preserve and be representative of the ecoregions and subregions.

Figure 3.7 Location of Ecoregions in Newfoundland and Labrador

Source: http://www.flr.gov.nl.ca/natural_areas/pdf/ecoregions_nf_lab.pdf

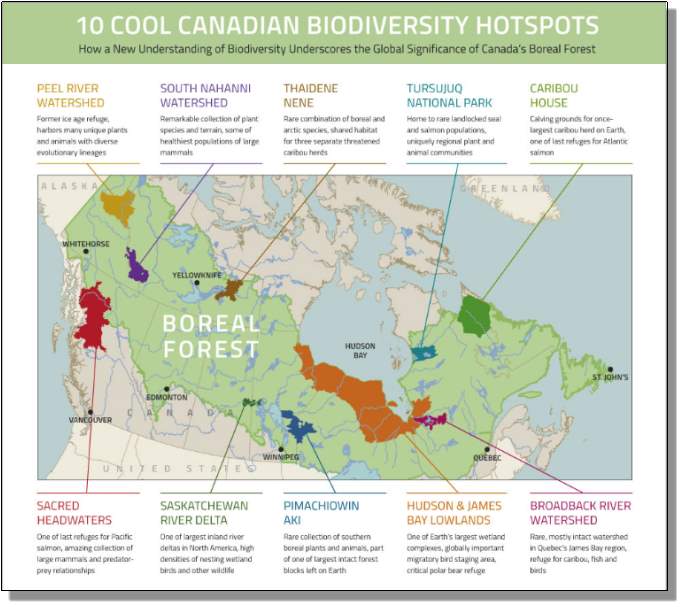

Generally, Canada is endowed with resource rich forests of high level of ecological intactness. The combination of favourable climatic, ecological, soil, geological and human (high overexploitation) factors have created pockets of rich natural heritage spots (biodiversity hotspots) across Canada. This is the indication of the rich natural blend of biodiversity over decades and centuries. Biodiversity spots are locations with high number, variability and species richness. 10 biodiversity hotspots across Canada have been identified, as shown in Figure 3.8. The biodiversity hotspot’s location and distribution reveal the following underlining factors – remoteness to human population, closeness to water body, latitudinal position towards the north and difference in size. The Caribou House biodiversity hotspot is partly within NL province and it is the breeding ground for one-time largest caribou herds on earth and it is also one of the remaining habitats for Atlantic salmon. These biodiversity hotspots are being managed by various provincial biodiversity conservation policies and the combination of provincial planning and management processes.

Other provincial planning and management processes employed include: Terrestrial Research and Habitat Management, Conservation Areas Reporting and Tracking System (CARTS), Environmental Impact Assessment, Environmental Review Process and Wildlife Information Management System. The suite of provincial planning processes, information systems and the biodiversity management structure mainly at the provincial level in Newfoundland and Labrador as discussed above, are insufficient and patchy.

Figure 3.8 Biodiversity Hotspots in Canada

Source: http://www.rcinet.ca/en/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2013/05/map-coolspots1.jpg

There are conscious attempts in the NL province to address the status and trend of biodiversity loss through different plans and strategies which often times are not coordinated and not jointly monitored to achieve the overarching goals of the Canadian National Biodiversity Strategy and the CBD through sub-national strategies. However, it is expected that these provincial planning and management processes are directed towards the NL’s sub-national biodiversity strategy in order to mainstream and monitor biodiversity concerns through their initiation, development, implementation and review.

Cite This Work

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing stye below:

Related Services

View allRelated Content

All TagsContent relating to: "Earth Sciences"

Earth Sciences is a field of study that focuses on the science behind planet Earth. Earth Sciences explores the physical and chemical aspects of not only planet Earth, but it's atmosphere too.

Related Articles

DMCA / Removal Request

If you are the original writer of this dissertation and no longer wish to have your work published on the UKDiss.com website then please: