Compassion Focused Therapy Intervention to Reduce Self-criticism

Info: 63607 words (254 pages) Dissertation

Published: 28th Jan 2022

Tagged: PsychologyTherapy

Abstract

Objectives

Self-criticism is a transdiagnostic process that is receiving increased research attention. This uncontrolled pilot study evaluated the feasibility and acceptability of a novel intervention based on Compassion Focused Therapy to reduce self-criticism, as well as investigating changes in a range of outcome and process measures.

Methods

Twenty-three student participants with significant impaired functioning associated with high levels of self-criticism completed a six-session formulation-focused intervention and a two-month follow-up appointment. Sessions were delivered weekly and the majority of techniques focused on increasing self-compassion. Self-report outcome and process measures were collected weekly prior to each session. Acceptability was assessed through qualitative feedback and rating scales.

Results

The intervention was feasible in terms of recruitment and retention of participants, and both the assessment methods and intervention were acceptable to participants. One way repeated measure ANOVAs showed statistically significant differences between pre and post-intervention on outcome measures (self-critical thinking, functional impairment, depression, anxiety, self-esteem and unhealthy perfectionism) and process measures (self-compassion, unhelpful beliefs about emotions and emotion regulation strategies). Participants either continued to improve between post-intervention and follow-up, or the gains were maintained between these two time points for all outcome measures. Effect sizes were medium to large for all outcome and process measures at both post-intervention and follow-up. Pearson correlations indicated that reductions in self-criticism were associated with increases in self-compassion suggesting it could be investigated further as a possible mediator of treatment outcome.

Conclusions

The compassion-focused intervention showed preliminary evidence of effectiveness for self-critical students and was a feasible and acceptable treatment approach.This intervention now requires investigation in a randomised controlled trial.

Contents

Click to expand Contents

1. Introduction

1.1 Self-criticism

1.2 The treatment of self-criticism

1.3 Constructs related to self-criticism and their treatment

1.3.1 Perfectionism

1.3.2 Self-esteem

1.3.3 Depressive rumination

1.4 Self-compassion interventions to target self-criticism

1.5 Student mental health

2. Aims

2.1 Hypotheses

3. Method

3.1 Ethical Approval

3.2 Design

3.3 Participants

3.4 Measures

3.4.1 Primary outcome measures

3.4.2 Secondary outcome measures

3.4.3 Process measures

3.4.4 Measures to aid formulation

3.4.5 Participant feedback

3.5 Procedure

3.6 Intervention

3.7 Feasibility & acceptability objectives

3.8 Data preparation and analysis

3.8.1 Hypotheses 1 & 2: Feasibility & acceptability

3.8.2 Hypotheses 3, 4 & 5: Changes in self-criticism and other outcomes

3.8.2.1 Therapist effects

3.8.2.2 Effects of waiting for intervention

3.8.2.3 Comparison between pre and post-intervention

3.8.2.4 Associations with reductions in self-criticism

4. Results

4.1 Participant demographic information

4.2 Hypothesis 1: Feasibility

4.2.1 Recruitment and retention

4.2.2 Inclusion / exclusion criteria

4.3 Hypothesis 2: Acceptability

4.3.1 Acceptability of assessment methods

4.3.2 Acceptability of the intervention

4.3.2.1 The intervention as a whole

4.3.2.2 Treatment rationale

4.3.2.3 Psycho-education components

4.3.2.4 Acceptability and use of specific techniques

4.3.2.5 Session attendance

4.4 Treatment protocol: fidelity & revisions

4.4.1 Fidelity

4.4.2 Protocol revisions

4.5 Changes in self-criticism and other outcomes

4.5.1 Therapist effects

4.5.2 Effect of waiting time for intervention

4.5.3 Hypotheses 3 and 4: Comparison between pre and post-intervention

4.5.3.1 Hypothesis 3A, 4 & 5: Primary outcome measures

4.5.3.2 Hypothesis 3B, 4 & 5: Secondary outcome measures

4.5.3.3 Hypothesis 3C, 4 & 5: Comparison between pre and post-intervention for process measures

4.5.3.4 Hypothesis 3C: Associations with reductions in self-criticism

5. Discussion

5.1 Hypothesis 1: Feasibility

5.2 Hypothesis 2: Acceptability

5.2.1 Acceptability of assessment methods

5.2.2 Acceptability of the intervention

5.3 Hypotheses 3, 4 & 5: Changes in self-criticism and other outcomes and associations between the changes

5.3.1 Impact on self-criticism and associated impairment

5.3.2 Changes in secondary outcome measures

5.3.3 Changes in process measure

5.4 Limitations

5.5 Strengths

5.6 Implications

5.7 Conclusions

References

Appendices contents page

Appendix 1. Psychiatry, Nursing & Midwifery Research Ethics Subcommittee (PNM RESC) original approval (18.11.2014)

Appendix 2. Psychiatry, Nursing & Midwifery Research Ethics Subcommittee (PNM RESC) modification approval (27.02.2015)

Appendix 3. Psychiatry, Nursing & Midwifery Research Ethics Subcommittee (PNM RESC) modification approval (16.07.2015)

Appendix 4. Questionnaires completed at each time point

Appendix 5. Study questionnaires

Appendix 6. Participant feedback questionnaire

Appendix 7. Measure of frequencies of use of specific intervention techniques since end of treatment collected at two-month follow-up appointment

Appendix 8. Flow chart to show participants’ journey and involvement of therapists

Appendix 9. Online recruitment advertisement

Appendix 10. Participant information sheet

Appendix 11. Participant consent form

Appendix 12. Session protocols

Appendix 13. Blank participant formulation worksheet

Appendix 14. Participant booklets

Appendix 15. Post-intervention ratings of how useful participants found the intervention

Appendix 16. Post-intervention ratings of how useful participants found each technique

Appendix 17. Ratings of frequency of use for each technique since end of treatment collected at follow-up appointment

Appendix 18. Results of independent t-tests comparing the two therapists on participant measures across time points

Appendix 19. Results of linear regressions investigating relationship between (a) length of baseline (time between screening and pre-intervention), (b) time from screening to post-intervention and (c) time from pre to post intervention and change in study measures

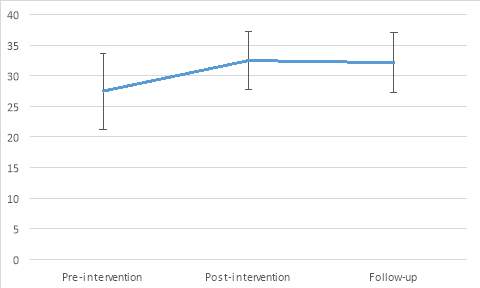

Appendix 20. Line graphs for secondary outcome measures (PHQ-9, GAD-7, RSES and ‘maladaptive perfectionism) at main study time points

Appendix 21. Line graphs for process measures (SCS, ERQ-reappraisal, ERQ-suppression, and BES) at main study points

List of Tables

Table 1 Feasibility objectives and outcomes

Table 2 Acceptability of assessment methods and intervention

Table 3 Participant baseline demographic information

Table 4 Primary outcome measures: Results of one-way ANOVAs, means and standard deviations and effect sizes

Table 5 Secondary outcome measures: Results of one-way ANOVAs, means and standard deviations and effect sizes

Table 6 Process measures: Results of one-way ANOVAs, means and standard deviations and effect sizes

List of Figures

Figure 1 Study flow diagram showing recruitment process

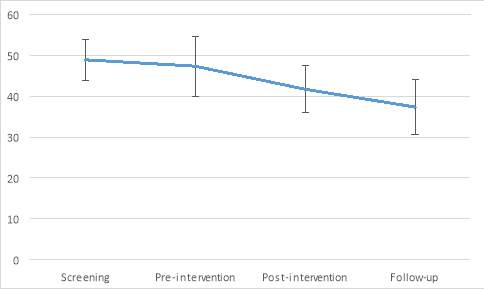

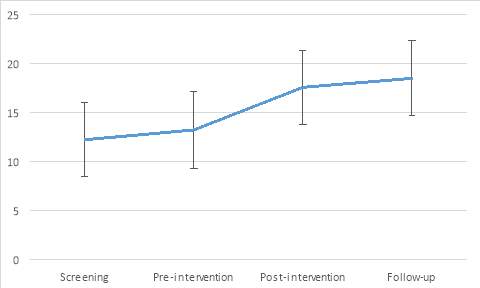

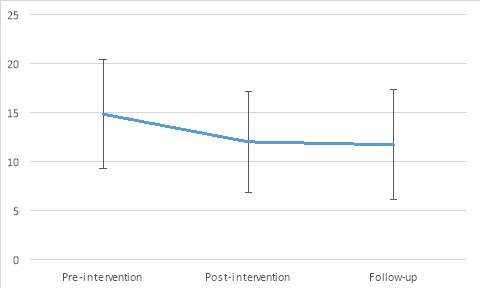

Figure 2 Line graph to show mean scores for the Habitual Index of Negative Thinking (HINT) at screening, pre-intervention, post-intervention & follow-up (one standard deviation error bars)

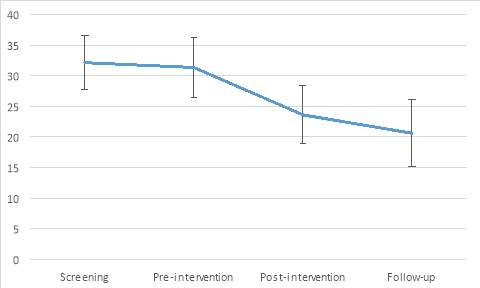

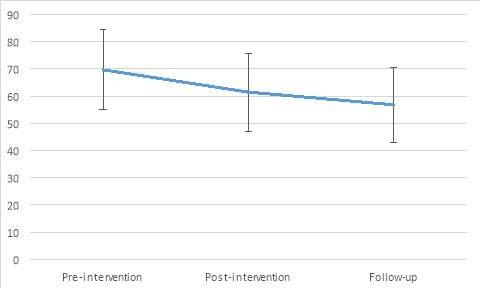

Figure 3 Line graph to show mean scores for the Self-Critical Rumination Scale (SCRS) at screening, pre-intervention, post-intervention & follow-up (one standard deviation error bars)

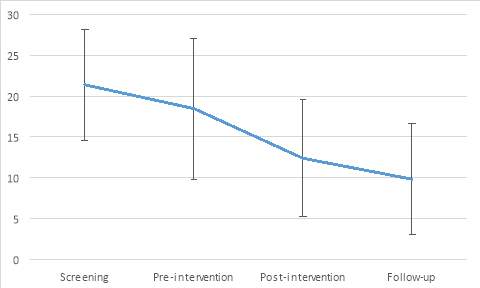

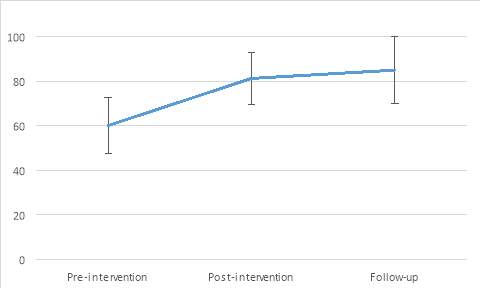

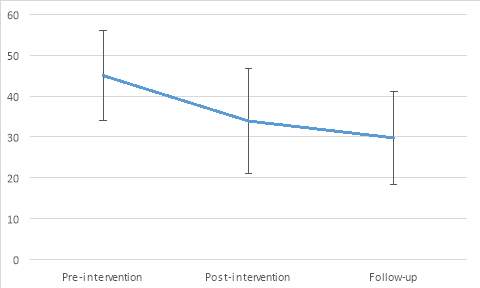

Figure 4 Line graph to show mean scores for the Work and Social Adjustment Scale (WASAS) at screening, pre-intervention, post-intervention & follow-up (one standard deviation error bars)

1. Introduction

1.1 Self-criticism

Self-criticism is a self-evaluative process where individuals judge themselves in a harsh or punitive way (Shahar et al., 2015). Self-criticism is considered to be a common experience; it has been reported across a range of settings including academia (Powers et al., 2011), and within both clinical and non-clinical populations (Baiao et al., 2014). Self-criticism has been described as a transdiagnostic process; high levels of self-criticism are predictive of a wide range of clinical difficulties including depression (Luyten et al., 2007), suicidality (O’Connor & Noyce, 2008), social anxiety (Cox, Fleet & Stein, 2004; Shahar, Doron & Szepsenwol, 2015) and eating disorders (Fennig et al., 2008). The relationship between self-criticism and depression has been a particular focus in previous research; levels of self-criticism have been found to predict depression and global psychosocial impairment in a clinical population after a four-year period (Dunkley et al., 2009). Self-critical individuals also have more difficulties forming and maintaining therapeutic relationships in treatment (Whelton, Paulson & Marusiak, 2007), and have poorer outcomes after treatment for depression (Marshall et al., 2008; Rector et al., 2000).

1.2 The treatment of self-criticism

Recently, specific interventions have been piloted to directly target high levels of self-criticism. Shahar et al (2012) found that an emotion-focused two-chair dialogue technique significantly reduced self-criticism in individuals recruited from university and community advertisements who scored at least one standard deviation above the means reported on the Forms of Self-Criticising/Attacking and Self-Reassuring Scale (FSCRS) by Gilbert et al (2004). These gains were maintained at a six-month follow-up (Shahar et al., 2012). Shahar et al (2015) used a Loving-Kindness Meditation (LKM) intervention with individuals who were ‘above average’ on the 11-item self-critical perfectionism subscale of the Dysfunctional Attitude Scale (SCP-DAS) (de Graaf, Roelofs & Huibers, 2009) and found significant reductions in self-criticism and increases in self-compassion compared to a waitlist control. Other than these studies, research focused on specific self-criticism interventions have been limited. Instead, interventions have been developed targeting overlapping or related constructs such as certain forms of perfectionism, self-esteem and rumination. These constructs will briefly be outlined below, including their relationship with self-criticism and the different treatment approaches designed to target them.

1.3 Constructs related to self-criticism and their treatment

1.3.1 Perfectionism

Self-criticism is often suggested to be a component of certain forms of perfectionism. Different types of perfectionism are thought to exist (Bergman, Nyland & Burns, 2007); for example, some have distinguished between maladaptive ‘self-critical perfectionism’ (SCP) (also called ‘evaluative-concerns’) and ‘positive striving’, a more adaptive perfectionism (Bieling, Israeli & Antony, 2004).SCP has been defined as a “hypersensitivity to perceived excessive external standards and criticism” (Powers et al., 2004, P. 62).Interestingly, Dunkley, Zuroff & Blankstein (2006) found that the Depressive Experiences Questionnaire (DEQ) (Blatt, D’Afflitti & Quinlan, 1976) self-criticism was the only sub-component of SCP that was a unique significant predictor of anxiety, depression and eating disorder symptoms after controlling for the effects of the other SCP subcomponents, suggesting that self-criticism is the key component of SCP that is associated with clinical problems.

Other researchers have drawn a distinction between perfectionism and ‘clinical perfectionism’, the latter of which has been conceptualised to include increased levels of self-critical thinking (Shafran, Cooper & Fairburn, 2002; 2003).Shafran, Cooper & Fairburn (2002) have developed a cognitive behavioural model of clinical perfectionism and CBT interventions have been shown significantly reduce clinical perfectionism (Riley et al., 2007; Steele et al., 2013). As part of these interventions, self-critical thoughts are targeted through psychoeducation, thought challenging and behavioural experiments. Of note, Steele et al (2013) found reductions in both perfectionism and the self-criticism subscale of the DAS (Weissman and Beck, 1978) after a group CBT intervention for psychiatric patients with clinical levels of perfectionism and a variety of Axis 1 diagnoses.

1.3.2 Self-esteem

Self-criticism is associated with lower self-esteem (Thompson & Zuroff, 2004) which in turn is a risk factor for mental health problems, such as depression and anxiety (Sowislo & Orth, 2013)and eating disorders (Cervera et al., 2003). High self-esteem has been defined in terms of a feeling that one is ‘good enough’ with a sense of self-worth (Rosenberg, 1989). In a CBT model of self-esteem, self-criticism is suggested to be a maintaining factor for low self-esteem (Fennell, 1998). Based on this model, a CBT intervention has been developed to improve self-esteem (Fennell, 1998; 2013). Part of this intervention targets self-criticism through thought challenging and behavioural experiments (Fennell, 2013). However, as this intervention contains multiple components, it is unclear to what extent self-criticism is a specific focus, and the impact of CBT for self-esteem on self-critical thinking has not been reported.

1.3.3 Depressive rumination

The relationship between self-criticism and rumination is also important to consider. Depressive rumination is defined as repetitive thinking or analysing about oneself, one’s symptoms or mood, as well as the reasons and implications of one’s problems (Nolen-Hoeksema, 1991; Watkins et al., 2014). Rumination is a risk factor for the onset and maintenance of depression (Nolen-Hoeksema, 2000). Self-critical individuals have a tendency to respond to low mood with more rumination (Spasojevic & Alloy, 2001). Although both self-criticism and rumination are self-focused, and rumination may include self-criticism, rumination is also conceptualised to include a far broader range of content including blaming others. Watkins and Nolen-Hoeksema (2014) conceptualise rumination as a learnt habitual behaviour. Watkins’ Rumination-Focused CBT (RF-CBT; Watkins et al., 2007; 2011) aims to identify warning signs of rumination and practice alternative responses to depressed mood in order to develop more adaptive habits. However, the impact of RF-CBT on self-critical thinking has not been investigated.

Like rumination, self-critical thinking could be conceptualized as a habitual response to, for example, making mistakes. An intervention to target self-criticism could therefore be based on a similar principle; identifying situations that trigger self-criticism and develop more adaptive habits. Research focused on self-compassion suggests that this could be an effective adaptive habit to teach individuals with high levels of self-criticism. This will be discussed further in the section below.

1.4 Self-compassion interventions to target self-criticism

Low levels of self-compassion have been suggested to be a key feature of self-critical individuals (Neff, 2003a). Self-compassion has been associated with lower levels of anxiety and depression, and higher levels of wellbeing and happiness (see Barnard & Curry, 2011; Macbeth & Gumley, 2012 for reviews). Furthermore, self-compassion has been found to partially mediate the relationship between self-criticism and depression (Joeng & Turner, 2015).

In an experimental design, Falconer et al (2014) found that a one-off virtual reality paradigm that focused on practicing a compassionate response to a child avatar from different perspectives led to reductions in self-criticism in individuals who reported high levels of self-criticism as measured by the FSCRS. However, such an approach is not available in most settings as requires virtual reality equipment.

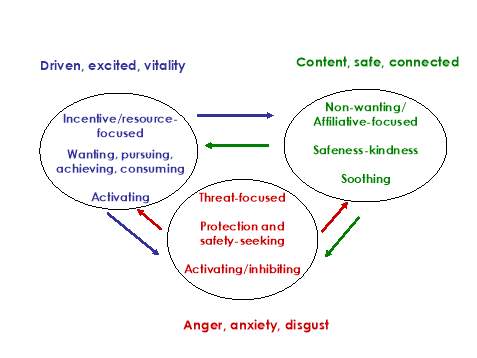

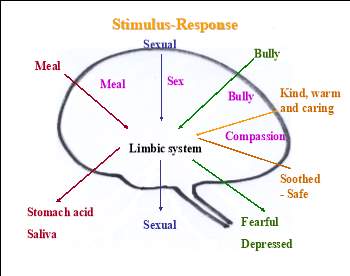

A range of treatment approaches have been developed to increase self-compassion (e.g. Neff & Germer, 2012; Jazaieri et al., 2013; Gilbert, 2009). One of these, Gilbert’s Compassionate Focused Therapy (CFT) has been designed specifically for individuals with high levels of self-criticism and shame (Gilbert, 2009; 2010a). CFT is based on the idea that there are at least three types of emotion regulation systems: a threat-protection system, designed to detect and respond to threats in the environment; a drive-motivation system, designed to direct individuals towards appropriate rewards, and a contentment-soothing-safeness system, designed to regulate feelings of contentment and calm (Gilbert, 2010a). CFT uses a ‘threat/safety strategy’ formulation (Gilbert, 2010c) which focuses on the organisation of these three systems, with a particular focus on threat and safety strategy development (Gilbert, 2010a). In this formulation, an individual’s early experiences lead to the development of key ‘internal’ fears, i.e. fears that an individual has about themselves, and ‘external’ fears, i.e. fears that an individual has about other people or the world. Individuals then develop ‘safety protection strategies’ as a way of coping with these key fears. For example, individuals may use achievement as a way of avoiding negative events or feelings of rejection leading to over-active drive-motivation systems (Gilbert, 2009). Individuals may also engage in self-criticism as a safety strategy that develops, for example, in the context of abuse, bullying or harsh parenting styles (Gilbert, 2009). As a safety strategy, self-criticism has both ‘intended’ consequences such as ‘to learn from mistakes’ and ‘unintended’ consequences, such as ‘worry, anxiety and low mood’ (Welford, 2012). Over time, self-critical individuals become even more highly sensitive to threats and, because they focus most of their attentional resources on detecting and responding to threat, the contentment-soothing-safeness system does not develop properly (Gilbert & Irons, 2005). Thus, self-critical individuals are thought to have over-active threat-protection and drive-motivation systems, and an under-active contentment-soothing-safeness system (Gilbert, 2009). CFT therefore aims to develop the contentment-soothing-safeness system using Compassionate Mind Training (CMT); a range of skills and practices that focus on developing self-compassion (Gilbert, 2009; 2010b).

Self-compassion is thought to consist of a range of attributes including ‘care for well-being’: having the intention and commitment to care about oneself; ‘sensitivity to distress’: being aware and open to one’s distressing experiences; ‘non-judgement’: trying not to judge or condemn one’s thoughts, feelings and behaviours; ‘distress tolerance’: learning to tolerate one’s difficult feelings rather than avoiding them, and ‘sympathy’ and ‘empathy’: being emotionally touched by one’s experiences (Gilbert, 2009). In CMT, individuals are taught to, for example, accept and tolerate their emotional experiences and develop more compassionate beliefs about distressing and difficult emotions. This is particularly important given that, in line with previous research about ‘maladaptive’ perfectionism, self-critical individuals may have unhelpful beliefs about experiencing or expressing negative emotions (Rimes & Chalder, 2010), and as a result, may have a tendency to suppress difficult emotions. Specific CMT exercises include using compassionate thought records to develop a ‘compassionate reframe’ or a compassionate reappraisal of difficult situations (Gilbert, 2005). This technique may help individuals increase their use of ‘cognitive reappraisal’, an adaptive emotion regulation strategy (Gross, 1998). CMT also includes the use of imagery, for example, developing a ‘compassionate other’ image, which has been shown to reduce self-reported self-criticism in individuals with depression (Gilbert & Irons, 2004).

Although there is growing evidence-base for CMT for individuals with severe and enduring mental health problems (Gilbert & Procter, 2006; Mayhew & Gilbert, 2008), the CFT approach has not yet been applied to individuals with specific difficulties with self-criticism. This study aimed to develop a novel intervention based on CFT to target self-criticism in a student population as a form of early intervention.

1.5 Student mental health

Half of all mental health problems start by mid-teens and three quarters by the age of 24 years (Kessler et al., 2007). Furthermore, in 2012 approximately 80% of university students were aged between 18 (and under) and 24 years (Higher Education Statistics Agency, 2016). Therefore, providing interventions to university students is a potential method for addressing mental health problems at an early stage before they may become chronic.

Whilst at university, students face a range of different stressors, such as managing the transition from school to university, their academic studies, and issues related to diversity and relationships (Hurst et al., 2013). These burdens have been positively associated with depression (Mikolajczyk et al., 2008). In a UK student survey, 31% of females and 23% of males reported to have had depression in the preceding year (El Ansari et al., 2011). This is similar to the rates of depression in the general population (Blanco et al., 2008). However, the mental health of students has become a particular concern for universities (Castillo & Schwartz, 2013); both the number and severity of mental health problems in this population is increasing (Gallagher, 2008). Furthermore, mental health problems can have a negative impact on academic performance (Brackney & Karabenick, 1995) or lead students to prematurely end their education (Kessler et al., 1995). Mental health problems in young adulthood have also been associated with a number of negative outcomes including fewer employment opportunities (Eisenberg, Goldberstein & Gollust, 2007). Given this context, it has been suggested that university is a promising setting for the early intervention of mental health problems (Hunt & Eisenberg, 2010).

One advantage of targeting self-criticism is that it is a transdiagnostic factor associated with a range of different psychological problems. It can also be present and impairing in the absence of a full clinical disorder and therefore addressing it could be a form of primary prevention for mental health problems. For students, learning to effectively manage self-criticism is not only important because of its relationship to mental health problems, but it has also been found to be associated with lower levels of goal pursuit (Powers et al., 2011), which in turn could impact on a student’s academic performance. Furthermore, in academic settings there is a high prevalence of perfectionistic tendencies (Arpin-Cribbie et al., 2008) and maladaptive forms of perfectionism have been associated with higher levels of anxiety and depression in students (Kawamura et al., 2001). There may also be particular benefit in helping students increase their self-compassion; it has been associated with lower levels of procrastination (Williams, Stark & Foster, 2008), personal distress (Neff & Pommier, 2012), and an increased sense of self-efficacy (Iskender, 2009). Self-compassion has also been found to act as a ‘buffer’ against the difficulties associated with the transition to university such as homesickness (Terry, Leary & Mehta, 2014).

2. Aims

The present study involved the development of a new six-session intervention, drawing predominantly on methods from CFT, to reduce self-criticism in students with high levels of self-criticism. An uncontrolled pilot study was conducted with the following specific aims:

- To assess the acceptability and feasibility of the new intervention and assessment methods to investigate the impact of this intervention.

- To investigate changes in self-criticism, impaired functioning, depression, anxiety, self-esteem and ‘maladaptive’ perfectionism, comparing pre-treatment scores with those at post-treatment and two-month follow-up.

- To gain preliminary information about possible mechanisms of change including self-compassion, beliefs about emotions and emotion regulation strategies (‘cognitive reappraisal’ and ‘expressive suppression’), as these are all addressed in CFT.

2.1 Hypotheses

It was hypothesized that:

- The intervention would be feasible to deliver in terms of the recruitment and retention;

- Participants would find both the intervention and assessment methods acceptable;

- At post-treatment compared to baseline participants would report:

- Lower levels of self-criticism and associated impairments in functioning;

- Lower levels of depression, anxiety and ‘maladaptive’ perfectionism and higher levels of self-esteem;

- Higher levels of self-compassion and ‘cognitive reappraisal’ and a reduction in ‘expressive suppression’ and unhelpful beliefs about the unacceptability of negative emotions. Linked to this, it was hypothesised that reductions in self-criticism would be associated with increases in self-compassion, ‘cognitive reappraisal’ and reductions in ‘expressive suppression’ and unhelpful beliefs about emotions.

- There would be significantly larger improvements in key outcomes from pre-treatment to post-treatment than between screening and pre-treatment assessments.

- The gains made in the intervention would be maintained over time (i.e. between post-treatment and follow-up).

3. Method

3.1 Ethical Approval

Ethical approval was gained from the King’s College London (KCL) Psychiatry, Nursing & Midwifery Research Ethics Subcommittee (see Appendices 1, 2 and 3).

3.2 Design

The study was an uncontrolled pilot study of a new intervention. A mixed qualitative and quantitative design was utilized in order to collect participant feedback about the acceptability of the intervention and assessment methods. Standardised questionnaire measures of self-criticism and other outcomes were completed at screening, prior to the weekly intervention sessions and at the 2-month follow-up appointment (see Appendix 4 for details about which questionnaires were completed at each time-point).

3.3 Participants

All participants were KCL students (see below for the inclusion and exclusion criteria). In regards to point 3 of the inclusion criteria, all participants had high scores on the self-criticism measures, however, an exact cut-off was not specified. Part of the development work of this study was to identify suitable questionnaire cut-off scores for inclusion as no previous studies were identified using this strategy.

Inclusion Criteria:

Exclusion Criteria:

|

The target sample size was 16-25 participants. This was in line with recommendations regarding sample sizes for pilot studies assessing intervention efficacy in a single group of participants (Hertzog, 2008).

3.4 Measures

Questionnaires were completed online using an online survey tool, Survey Monkey. To reduce burden placed on participants, the complete data set was only completed at session 1, 3, 6 and follow-up (see Appendix 4). Of note, two self-criticism questionnaires were completed at each time point. Two additional self-criticism questionnaires were completed once prior to session 1 to aid with the development of individualized formulations. The questionnaires are described below (see Appendix 5 for copies). The Cronbach’s alphas of the measures were examined at pre-intervention to confirm their internal consistency. Only the ‘doubts about actions’ subscale of the Multi-Dimensional Perfectionism Scale (MDPS) and the ‘inadequate self’ subscale of the FSCRS were below 0.70. Thus, the other measures were within satisfactory limits (Nunnaly & Bernstein, 1994).

3.4.1 Primary outcome measures

The Habitual Index of Negative Thinking (HINT) (Verplanken et al., 2007)

The HINT has 12 items measuring habitual negative self-thinking. Participants rated their agreement on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from “Strongly disagree” to “Strongly agree”. A score was given out of 60; higher scores represented higher levels of negative self-thinking. In previous research the internal consistency was 0.95 (Verplanken et al., 2007); in this study Cronbach’s alpha= 0.88.

Self-Critical Rumination Scale (SCRS) (Smart, Peters & Baer, 2015)

The SCRS has 10 items measuring self-critical rumination. Participants rated their agreement on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from “Strongly disagree” to “Strongly agree”. A score was given out of 40; higher scores represented higher levels of self-critical rumination. In previous research the internal consistency was 0.92 (Smart et al., 2015); in this study Cronbach’s alpha= 0.75.

Work and Social Adjustment Scale (WASAS) (Mundt et al., 2002)

The WASAS has 5 items and was used to measure the impact of self-criticism on different areas of an individual’s life. Each item focused on a different area of functioning such as work and home management.Participants rated their agreement on a 9-point Likert scale ranging from “Not at all” to “Very severely”.In previous research the internal consistency ranged from 0.70 to 0.94 (Mundt et al., 2002); in this study Cronbach’s alpha= 0.80. A score was given out of 40; higher scores represented more impaired levels of functioning. Scores of 10 and above are thought to indicate significant functional impairment (Mundt et al., 2002). As there is little evidence about scores on measures of self-criticism that would indicate a clinically significant level of self-criticism, the WASAS was used as the measure for calculating the proportion of the participants whose scores fell below clinical cut-off (i.e. WASAS score of 9 and below) after treatment.

3.4.2 Secondary outcome measures

Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) (Kroenke, Spitzer & Williams, 2001)

The PHQ-9 has 9 items measuring depressive symptoms over the last 2 weeks. Participants rated their agreement on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from “Not at all” to “Nearly every day”. A score was given out of 27; higher scores represented more severe depression. In previous research the internal consistency ranged from 0.86 to 0.89 (Kroenke et al., 2001); in this study Cronbach’s alpha= 0.83.

Generalised Anxiety Disorder (GAD-7) (Spitzer et al., 2006)

The GAD-7 has 7 items measuring anxiety over the last 2 weeks. Participants rated their agreement on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from “Not at all” to “Nearly every day”. A score was given out of 21; higher scores represented more severe anxiety. In previous research the internal consistency was 0.92 (Spitzer et al., 2006); in this study Cronbach’s alpha= 0.90.

Rosenberg’s Self-Esteem Scale (Rosenberg, 1965)

The RSES has 10 items measuring global self-esteem. Participants rated their agreement on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from “Strongly agree” to “Strongly disagree”. Items 3, 5, 8, 9 and 10 were reverse scored. In previous research the internal consistency ranged between 0.72 – 0.88 (Rosenberg, 1965); in this study Cronbach’s alpha= 0.81. A score was given out of 30; higher scores represented higher self-esteem.

The Multi-Dimensional Perfectionism Scale (MDPS) (Frost et al., 1990)

The MDPS has 35 items measuring perfectionism. Participants rated their agreement on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from “Strongly agree” to “Strongly disagree”. There are 6 subscales: ‘concern over mistakes’ (CM), ‘personal standards’ (PS), ‘parental expectations’ (PE), ‘parental criticism’ (PC), ‘doubts about actions’ (DA) and ‘organisation’ (O). For this study, the CM, DA, PE and PC subscales were totalled to measure ‘maladaptive’ perfectionism (Range: 22 – 110) (Stumpf & Parker, 2000). In previous research internal consistency ranged from 0.77 to 0.93 (Frost et al., 1990); in this study subscales Cronbach’s alpha ranged from 0.67 – 0.90.

3.4.3 Process measures

Self-Compassion Scale (SCS) (Neff, 2003b)

The SCS has 26 items divided into 6 subscales: 3 measure ‘self-compassion’ (‘common humanity’, ‘self-kindness’ and ‘mindfulness’) and 3 measure ‘coldness towards the self’ (‘self-judgement’, ‘over identification’ and ‘isolation’). Participants rate their agreement on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from “Almost never” to “Almost always”. Items from the 3 ‘coldness towards the self’ subscales are reverse scored. A score was given out of 130; higher scores represented higher levels of self-compassion. In previous research the internal consistency was 0.97 (Neff & Germer, 2013); in this study Cronbach’s alpha= 0.88.

The Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (ERQ) (Gross & John, 2003)

The ERQ has 10 items divided into 2 subscales measuring individual differences in the use of 2 emotion regulation strategies: ‘cognitive reappraisal’ and ‘expressive suppression’ (referred to as ‘reappraisal’ and ‘suppression’ in following sections). Participants rate their agreement on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree”. Higher scores indicated a greater use of this type of strategy. In previous research the internal consistency was 0.79 for ‘reappraisal’ and 0.73 for ‘suppression’ (Gross & John, 2003); in this study Cronbach’s alpha was 0.79 for ‘reappraisal’ and 0.80 for ‘suppression’.

Beliefs about Emotions scale (BES) (Rimes & Chalder, 2010)

The BES has 12 items measuring the unacceptability of experiencing or expressing negative emotions. Participants rated their agreement on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from “totally agree” to “totally disagree”. A score was given out of 72; higher scores represented stronger beliefs about the unacceptability of negative emotions. In previous research the internal consistency was 0.91 (Rimes & Chalder, 2010); in this study Cronbach’s alpha= 0.83.

3.4.4 Measures to aid formulation

The Forms of Self-Criticizing/Attacking and Self-Reassuring Scale (FSCRS) (Gilbert et al., 2004)

The FSCRS has 22 items measuring different forms of self-critical and self-reassuring responses to a setback. It has 3 subscales: ‘inadequate self’ (9 items; internal consistency = 0.90), ‘hated self’ (5 items; internal consistency = 0.86), and ‘self-reassurance’ (8 items; internal consistency = 0.86). Participants rated their agreement on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from “Not at all like me” to “Extremely like me”. In this study, Cronbach’s alpha were 0.62 for ‘inadequate self’, 0.83 for ‘reassure self’ and 0.75 for ‘hated self’.

The Functions of Self-Criticizing/Attacking Scale (FSCS) (Gilbert et al., 2004)

The FSCS has 21 items examining reasons why individuals may be self-critical. It has 2 subscales: ‘self-correction’ (13 items; internal consistency = 0.92) and ‘self-persecution’ (8 items; internal consistency = 0.92). Participants rated their agreement on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from “Not at all like me” to “Extremely like me”. In this study Cronbach’s alpha for the whole scale was 0.72.

3.4.5 Participant feedback

Feedback was collected at various points throughout the study. In session 1, participants rated how ‘logical’ the intervention approach seemed to be on a 5-point Likert scale where 0 was “not at all” and 4 was “extremely”. Feedback was also collected online through Survey Monkey after the last intervention session (completion was optional). The survey was devised for the purpose of this study and contained both quantitative rating scales and open-ended questions (see Appendix 6). As part of this questionnaire, participants were asked to rate different aspects about the intervention on a 5-point Likert scale where 1 was “strongly disagree” and 5 was “strongly agree”. Participants also rated the usefulness of techniques on 5-point Likert scale where 0 was “not at all” and 4 was “very much”. At follow-up, participants rated how often they had used each technique since the end of treatment using a 6-point Likert scale where 0 was “not at all” and 5 was “every day” (see Appendix 7).

3.5 Procedure

The current study was completed by two trainee clinical psychologists. Both were involved equally in all stages of the study design, procedure and participant data collection. Therapist 1 (author) analysed the feasibility, acceptability and pre and post outcome data for the current study. Therapist 2 analysed the data that was collected from a qualitative interview that took place immediately prior to session 1. Appendix 8 displays a flow chart highlighting the participants’ journey through the study and the tasks completed by both therapists.

Two recruitment drives were completed; the first took place between February – March 2015, the second took place in September 2015. For each drive, the study was advertised twice through a fortnightly email about current KCL research projects and further information about the study was included on the KCL intra-net (see Appendix 9 for advertisement). Individuals who responded were sent a Participant Information Sheet (see Appendix 10) and a link to the screening questionnaires.

Individuals who appeared to meet the inclusion criteria were offered a telephone screening to further assess eligibility. During this screening, past and current mental health problems were assessed using the latest version of the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I) (English Version 6.0.0), a brief structured interview that assesses DSM-IV and ICD-10 psychiatric disorders through different modules (Medical Outcome Systems, 2016). The M.I.N.I has been validated against other clinical interviews and expert opinion across different European countries (Lecrubier et al., 1997; Sheehan et al., 1997; Amorim et al., 1998; Sheehan et al., 1998). If any risk issues were identified through the M.I.N.I ‘suicidality’ section, a further detailed risk assessment was completed.

Decisions about eligibility were made after discussions with the research team and then communicated to the individual by either phone or email. If they still wished to take part, participants then completed a participant consent form (see Appendix 11). Individuals who were not eligible were signposted to appropriate alternative sources of support.

Two trainee clinical psychologists delivered the intervention supervised by a consultant clinical psychologist. Treatment was offered on a first-come-first-served basis but also took account of participants’ availability to complete a course of weekly sessions. The average time between screening and session 1 was 13 weeks (SD=7.62).

Measures were completed weekly through Survey Monkey (see Appendix 4). Immediately prior to session 1, a semi-structured interview was conducted by the therapist about the participant’s experiences of self-critical thinking. This ranged from 45 minutes to 1.5 hours. These interviews were used for therapist’s 2 research project, however, the information gained was also utilised in session 1.

3.6 Intervention

The intervention consisted of six 1-hour individual sessions (seeAppendix 12 for session protocols). Sessions were delivered approximately weekly. The time between some of the sessions varied in length; reasons for this included university holidays and sickness. Every session was audio-recorded and listened to by the therapist’s supervisor to ensure fidelity to the protocol and for supervision purposes. A telephone follow-up appointment took place approximately 2-months post-intervention.

In session 1, the information gathered during the semi-structured interview was used to develop an individualized formulation with the participant based on Gilbert’s (2010c) ‘threat/safety strategy formulation’ (see Appendix 13). Participants were given psychoeducation about the self-compassion approach, including information about the 3-emotion regulation systems (Gilbert, 2009; 2010a). Finally, as part of the acceptability objectives, participants were given an overview of the intervention and rated how ‘logical’ the treatment rationale was.

The remaining sessions followed the same general structure: agenda setting and check in, review of the homework tasks, completion of an experiential exercise to practice a new technique and, finally, a summary of the session and homework setting. The sessions covered techniques primarily aimed at helping participants to reduce and cope with their self-critical thinking, as well as developing self-compassion. Throughout the sessions, where appropriate, links were made to the both the original formulation and the 3 emotion-regulation systems. Participants were given a booklet at the end of sessions 1-5 with further details about the session content (see Appendix 14). The treatment protocol and booklets were designed by the two trainee psychologists providing the intervention and their primary supervisor, drawing heavily from Gilbert’s Compassionate Mind approach as well as general cognitive behavioural therapy principles and research evidence about self-criticism.

3.7 Feasibility & acceptability objectives

Feasibility and acceptability were assessed through specific objectives which were further operationalized into specific outcomes (Thabane et al., 2010) (see Table 1 & 2).

Table 1 Feasibility objectives and outcomes

| Objective | Specific Objective | Outcome |

| Recruitment | How easy is it to recruit eligible participants? |

|

| Is the inclusion/exclusion criteria appropriate for the target population? |

|

|

| Retention | Do participants complete the intervention? | Number of drop outs:

|

Table 2 Acceptability of assessment methods and intervention

| Objective | Specific Objective | Outcome |

| Assessment methods | How acceptable are the:

|

|

| Intervention | How acceptable is the intervention content?

|

|

| How acceptable are the practical aspects of the sessions? |

|

3.8 Data preparation and analysis

3.8.1 Hypotheses 1 & 2: Feasibility & acceptability

Written responses to the open-ended feedback questions were analysed using brief content analysis (Mayring, 2000). Inductive category development was utilised whereby responses were read through and categories were defined based on the material. After reading through approximately 50% of the text for each question, these categories were refined before the entire text was analysed using the final categories.

3.8.2 Hypotheses 3, 4 & 5: Changes in self-criticism and other outcomes

As there were only 11 missing items across the dataset, mean item scores were computed and input for missing items (Fox‐Wasylyshyn and El‐Masri, 2005). As multiple tests were used, a more conservative cut-off p value ≤0.01 was used to indicate statistical significance; p values between 0.01 and 0.05 were considered to be a ‘non-significant trend’. As well as this, in line with the assumption of equal standard deviations, a rule of thumb was used for t-tests and ANOVAs to check that the smallest standard deviation between, for example, therapists, was not less than half of the largest standard deviation (Howell, 2012). Throughout, pre-intervention is defined as session 1 as this was the first time point that participants completed all measures; post-intervention is defined as session 6. Of note, a statistician was consulted prior to data analysis.

3.8.2.1 Therapist effects

Independent t-tests were completed to determine if there were differences in outcomes between therapists at each time point. The data was assessed to confirm that it met specific parametric assumptions. Although there were 3 extreme data-points, the inclusion and exclusion of them resulted in no changes to conclusions and they were therefore included in the analyses. Normality was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test. A number of time points for therapist (2) violated this assumption. However, as independent t-tests are considered ‘robust’ to deviations from normality, and the non-parametric Mann-Whitney U test resulted in no changes to the final conclusions, parametric t-tests were used. For each t-test, homogeneity of variances was also confirmed.

3.8.2.2 Effects of waiting for intervention

Linear regressions were used to investigate whether the time between screening and pre-intervention and the subsequent time to complete the intervention (time between screening and post-intervention and time between pre and post-intervention) predicted change in any of the study measures. It was confirmed that the data met the following assumptions for linear regressions: linearity, independence of observations, no significant outliers, homoscedasticity, and residuals (errors) were approximately normally distributed.

3.8.2.3 Comparison between pre and post-intervention

To examine the effect of the intervention on the study measures separate repeated measures ANOVAs were conducted for each measure with time as the repeated measure factor. The time points included were screening (if completed), pre-intervention, mid-treatment (session 3), post-intervention and follow-up. When a significant effect of time was found, planned pairwise comparisons were completed to determine whether there were significant differences between measures at the end of the intervention and follow-up compared with pre-intervention. A further t-test was conducted to investigate whether gains were maintained between post-intervention and follow-up. Contrasts between screening and pre-intervention were also completed to determine whether there were any significant changes during the baseline period prior to treatment.

Effect sizes were calculated using Cohen’s d and interpreted using the following cut-offs: ‘negligible’ effect

Across the dataset, there was 1 extreme outlier. As there were no changes to final conclusions without this data point, it was included in the analyses. Normality was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Although a number of time-points for the PHQ-9 and GAD-7 violated this assumption, since repeated measures ANOVA are considered ‘robust’ to deviations from normality and the non-parametric Friedman test resulted in no changes to the final conclusions, the ANOVAs are presented. Where the Mauchly’s test of sphericity indicated that the assumption of sphericity had been violated, Greenhouse-Geisser was used to correct the ANOVAs.

For outcome measures that were completed at both screening and pre-intervention, paired t-tests were also completed to determine whether there were statistically significant differences between the mean change in scores between screening and pre-intervention and between pre-intervention and post-intervention. Change in scores were computed by pre-intervention scores minus screening scores and post-intervention scores minus pre-intervention scores.

3.8.2.4 Associations with reductions in self-criticism

Pearson correlations were used to determine whether reductions in self-criticism were associated with increases in self-compassion and ‘reappraisal’, and reductions in ‘suppression’ and unhelpful beliefs about emotions. For this analysis, change in scores between pre-intervention and post-intervention were used.

4. Results

The results are presented in five different sections: participant baseline demographic information, feasibility and acceptability objectives and outcomes (see Table 1 & 2), details about the treatment protocol (fidelity and revisions), and descriptive statistics and statistical analyses for outcome data.

4.1 Participant demographic information

Table 3 summarizes baseline demographic information. The majority of participants were Caucasian female postgraduate students. Although only 7 participants had a current mental health diagnosis (anxiety and/or depression), 13 participants had a past diagnosis of depression.

Table 3 Participant baseline demographic information

| Characteristics | |

| Age, mean (SD), years | 25.3 (6.16) |

| Sex, n (%) | |

| Female | 19 (82.61) |

| Male | 4 (17.39) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |

| Caucasian | 17 (73.91) |

| Non-Caucasian | 6 (26.09) |

| Current antidepressant medication, n (%) | 2 (8.70) |

| Current Psychiatric Diagnoses at screening, n (%) | |

| None | 16 (69.57) |

| Depression | 1 (4.35) |

| Social phobia | 1 (4.35) |

| Generalised anxiety disorder (GAD) | 1 (4.35) |

| Social phobia & GAD | 1 (4.35) |

| Depression, social phobia & GAD | 1 (4.35) |

| Depression, agoraphobia, social phobia & GAD | 1 (4.35) |

| Depression, agoraphobia, obsessive compulsive disorder & GAD | 1 (4.35) |

| Past diagnosis of depression, n (%) | 13 (56.52) |

| Stage at university | |

| Undergraduate | 7 (30.43) |

| Postgraduate | 16 (69.57) |

4.2 Hypothesis 1: Feasibility

4.2.1 Recruitment and retention

Figure 1 displays the recruitment and retention numbers for this study. A sufficient number of eligible participants were recruited and subsequently completed the intervention.

Figure 1 Study flow diagram showing recruitment process

Responded to online advertisement (n=176)

Excluded (n=17)

- Lack of distress or significant impairment (n=4)

- Unsuitable level of English language (n=3)

- Alcohol dependence (n=3)

- Level of risk (n=2)

- Availability issues (n=2)

- Anorexia nervosa (n=1)

- Not stable medication (n=1)

- Receiving another intervention (n=1)

Completed screening questionnaires (n=93)

Offered telephone screening (n=68)

Assessed for eligibility (n=47)

Consented (n=30)

Withdrew prior to starting treatment (n=6)

- Change in personal circumstance (n=1)

- Started student counselling (n=1)

- Other family commitments (n=1)

- Unknown reasons (n=3)

Started treatment (n=24)

Did not complete treatment (n=1)

- Withdrew after session 2 due to life event

Completed treatment (n=23)

Complete two-month follow-up measures (n=23)

Attended telephone follow-up appointment (n=22)

4.2.2 Inclusion / exclusion criteria

The inclusion / exclusion criteria resulted in a group of participants who were all experiencing significant distress or impairment as a result of their self-criticism and were able to complete the intervention. There was therefore no indication that the criteria would need adjusting for a follow-on study.

4.3 Hypothesis 2: Acceptability

Twenty-one of the 24 participants completed the feedback questionnaire about the acceptability of the assessment methods and intervention. The open-ended questions were optional and therefore not always completed by all 21 participants.

4.3.1 Acceptability of assessment methods

Qualitative analysis revealed that the telephone screening appointment provided participants with a helpful introduction to the study and therapists. Some participants suggested that they would have preferred to complete this appointment face-to-face rather than over the phone due to the sensitive nature of some of the questions.

All participants completed the outcome measures at each time point (see Appendix 4). The qualitative analysis revealed that some participants thought that there were too many questionnaires in the full questionnaire pack. Some participants described the weekly questionnaires as “repetitive” to complete.

4.3.2 Acceptability of the intervention

4.3.2.1 The intervention as a whole

Results from the feedback ratings about the usefulness of the intervention are presented in Appendix 15. Of the 21 participants who completed these ratings, 100% of participants “agreed” or “strongly agreed” that the intervention was useful and that they would recommend it to others with high levels of self-criticism. Nineteen participants (90.5%) “agreed” or “strongly agreed” that their therapist understood their needs. Nineteen participants (90.5%) “agreed” or “strongly agreed” that the intervention reduced their self-criticism and 95.2% (n=20) “agreed” or “strongly agreed” that they had improved their ability to cope with it. In line with this, the qualitative analysis revealed that the intervention helped participants learn about the causes and negative impacts of self-criticism, as well as increasing their awareness and control over it. Seventeen participants (81%) “agreed” or “strongly agreed” that the intervention improved their self-compassion. Qualitative feedback revealed that participants had learnt how to use self-compassion towards their self-criticism as well as towards their distress more generally. For the single participant who had not agreed with the statements that the intervention had helped to reduce self-criticism or their ability to cope with it had, nevertheless, indicated that the intervention was helpful, their feedback about “the most important thing” about the intervention was inspected. This indicated that they had learned to view things in in a more positive light instead of focusing on the negative and that mental health requires effort and practice and should not be neglected or disregarded.

4.3.2.2 Treatment rationale

In session one 90.5% of participants (n=19) described the intervention rationale as either “very” or “extremely” ‘logical’ (Mean= 3.60, SD= 0.56).

4.3.2.3 Psycho-education components

The mean percentage of the weekly booklets read by participants was 79.5% (SD= 27.51).In the qualitative analysis participants described them as clear and comprehensive and as a useful way of recapping on the techniques covered in the sessions.

4.3.2.4 Acceptability and use of specific techniques

The mean time spent practicing techniques each week was 140.8 mins (SD= 155.58). Results from the ratings about the usefulness of each technique are presented in Appendix 16. All techniques were rated as at least “somewhat” useful by most of the participants. ‘Decentering’ and ‘compassionate reframes’ received the greatest proportion of the two highest usefulness ratings (both 76%, n=16). Relaxation had the smallest proportion of the two highest ratings, although 38% of participants (n=8) rated it as very useful.

At follow-up, 100% of participants who attended the telephone follow-up (n=22) had been using at least 1 of the techniques during the time between post-intervention and follow-up (see Appendix 17 participants’ reports of technique usage at follow-up). Fifteen participants (68%) had been using either ‘decentering’ or ‘compassionate behaviours’ at least “once a week”. Thirteen participants (59.3%) had been using ‘compassionate reframes’ at least “once a week”. Thus, ‘compassionate reframes’, ‘decentering’ and ‘compassionate behaviours’ were the most frequently used techniques. In the follow-up session, the majority of participants commented that the ‘compassionate reframe’ had become fairly automatic rather than a deliberate process each time.

4.3.2.5 Session attendance

Across all treatment phases, there were 16 cancelled and rearranged appointments. No sessions were missed without prior warning. The qualitative analysis revealed that the majority of participants could not identify anything that could have been changed about the delivery of the intervention to improve participation (n=16, 76.2%). Specific suggestions described by participants were offering sessions at a different point in the academic year (although further explanation as to why was not given), as well as offering longer sessions or sessions fortnightly, in the evenings or during weekends. Most participants felt the number of sessions had been appropriate; only 1 participant suggested that they would have preferred 1-2 additional sessions.

4.4 Treatment protocol: fidelity & revisions

4.4.1 Fidelity

For 21 participants, the full treatment protocol was followed. There were 2 participants whose treatment deviated (slightly) from the protocol. The first participant required a longer time to go through the ‘compassionate self’ technique (across 2 sessions rather than 1 session) and was therefore offered an additional telephone appointment to finalise the session 6 action plan. The second participant was slower to engage with the techniques practiced in the first few sessions and the decision was taken to support them using those techniques rather than practising new methods in session 5 or 6, although they received information about all techniques in the booklets.

4.4.2 Protocol revisions

The feedback and engagement of the first 4 participants were discussed in supervision and, based on these discussions, there were 3 minor changes to the treatment protocol. Firstly, the ‘self-criticism summary’ was made into a homework task after session 1 to allow more time in session 2 to practice the ‘compassionate reframe’. Secondly, in order to support participants to access their ‘compassionate self’ specific participant responses were incorporated into a script which was read and audio-recorded by the therapist. Finally, the ‘loving-kindness meditation’ was incorporated into the session 6 protocol, rather than given as a homework task.

4.5 Changes in self-criticism and other outcomes

4.5.1 Therapist effects

Independent t-tests revealed that at session 1, there was a significant difference in ‘suppression’ scores between therapist (1) (M= 11.73, SD= 5.71) and therapist (2) (M= 17.67, SD= 3.70); [t(21)= -2.99, p= 0.007]. No other statistically significant differences were found (see Appendix 18).

4.5.2 Effect of waiting time for intervention

Linear regression analyses showed that length of the baseline period, the time between screening and post-treatment and the time between pre-treatment and post-treatment were not significantly associated with the change in any of the study measures (see Appendix 19).

4.5.3 Hypotheses 3 and 4: Comparison between pre and post-intervention

The Results of one-way repeated ANOVAs for primary, secondary and process measures are displayed in Table 4, 5, & 6 respectively. Results of the subsequent planned pairwise comparisons are summarised below.

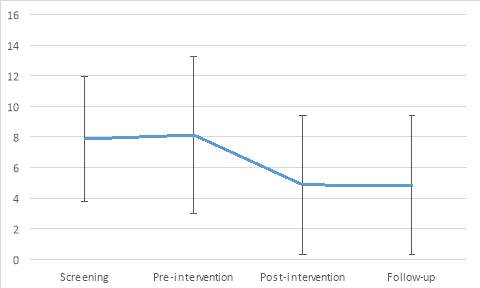

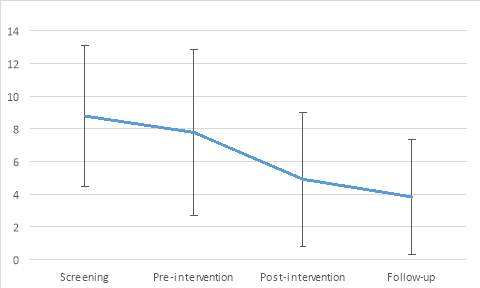

4.5.3.1 Hypothesis 3A, 4 & 5: Primary outcome measures

In line with hypotheses, there were statistically significant reductions between pre and post-intervention and between pre-intervention and follow-up for all primary outcome measures (p values ≤0.002). There were also statistically significant reductions between post-intervention and follow-up (p values ≤0.009) (Figures 2, 3 & 4 display mean scores for the HINT, SCRS and WASAS at main study time points). The Cohen’s d indicated that the intervention had a large effect size for self-criticism at both post-intervention and follow-up, compared with a small effect size for changes over the pre-treatment period. For impaired functioning there was a small effect size for the pre-treatment period, medium effect size from pre-treatment to post-intervention and a large effect size from pre-treatment to follow-up. No significant changes in the primary outcome measures were found over the baseline period between screening and pre-intervention (p values >0.08). Comparing change during the baseline period with the treatment period directly, paired t-tests indicated significantly larger reductions in pre- to post-treatment mean scores than screening to pre-treatment changes for the HINT [t(22)= -6.23, pt(22)= -8.24, pt(22)= -5.07, p

At post-intervention 8/23 (35%) of participant’s impaired functioning related to self-criticism reduced to below sub-clinical cut-off (Mundt et al., 2002). At follow-up, this had increased to 14/23 (61%) of participants.

Table 4 Primary outcome measures: Results of one-way ANOVAs, means and standard deviations and effect sizes

| Mean scores (standard deviations) | ANOVA | Effect sizes | |||||||||||

| Screening | Session 1 (Pre) | Session 2 | Session 3 | Session 4 | Session 5 | Session 6 (Post) | Follow-up | F (4, 88) | p-value | Pre-treatment changes (Pre – Screening) | Post – Pre | FU – Pre | |

| Habitual Index of Negative Thinking | 48.91

(5.09) |

47.35

(7.30) |

49.39 (5.15) | 46.52

(6.69) |

45.00 (5.05) | 43.00 (5.73) | 41.70

(5.76) |

37.35

(6.70) |

22.76 | -0.31 | -0.77 | -1.37 | |

| Self-Critical Rumination Scale (i) | 32.13

(4.42) |

31.35

(4.83) |

31.04 (4.79) | 28.48

(5.60) |

27.48 (4.91) | 26.26 (5.75) | 23.61

(4.75) |

20.61

(5.47) |

36.93

(2.42, 53.30) |

-0.18 | -1.60 | -2.22 | |

| Work and Social Adjustment Scale | 21.39

(6.79) |

18.48

(8.63) |

20.30 (7.86) | 17.70

(7.25) |

17.26 (7.68) | 15.87 (8.82) | 12.39

(7.15) |

9.83

(6.81) |

20.65 | -0.43 | -0.71 | -1.00 | |

Notes:

Scores for session 2, 4 and 5 are included for information and were not included in any of the analyses.

(i) Greenhouse-Geisser correction applied & degrees of freedom listed in table; FU: Follow-up.

Figure 2 Line graph to show mean scores for the Habitual Index of Negative Thinking (HINT) at screening, pre-intervention, post-intervention & follow-up (one standard deviation error bars)

Figure 3 Line graph to show mean scores for the Self-Critical Rumination Scale (SCRS) at screening, pre-intervention, post-intervention & follow-up (one standard deviation error bars)

Figure 4 Line graph to show mean scores for the Work and Social Adjustment Scale (WASAS) at screening, pre-intervention, post-intervention & follow-up (one standard deviation error bars)

4.5.3.2 Hypothesis 3B, 4 & 5: Secondary outcome measures

In line with hypotheses, there were statistically significant differences between pre and post-intervention and between pre-intervention and follow-up for all secondary outcome measures (p values ≤0.005) (see Appendix 20 for line graphs displaying mean scores for the PHQ-9, GAD-7, RSES and ‘maladaptive’ perfectionism at main study time points).Participants reported lower levels of depression, anxiety and ‘maladaptive’ perfectionism, and higher levels of self-esteem at post-intervention and follow-up compared with pre-intervention.For depression, anxiety and self-esteem there was no significant further change between post-intervention and follow-up. There was a trend that participants reported lower levels of ‘maladaptive’ perfectionism between post-intervention and follow-up (p= 0.03).Cohen’s d indicated that the intervention had a medium effect size for depression at both post-intervention and follow-up, compared with a ‘negligible’ effect size for change over the pre-treatment period. For anxiety, there was a small effect size for change over the pre-treatment period, medium effect size at post-intervention and a large effect size at follow-up. For self-esteem, there was a small effect size for change over the pre-treatment period and a large effect size at both post-intervention and follow-up.The effect sizes for ‘maladaptive’ perfectionism were medium at post-intervention and large at follow-up.

No significant differences were found for depression, anxiety and self-esteem between screening and pre-intervention (p values >0.24). Indeed, additional paired t-tests indicated significantly larger changes in scores between pre-intervention to post-intervention than over the baseline period for the PHQ-9 [t(22)= -3.61, p=0.002], the GAD-7 [t(22)= -4.14, pt(22)= 6.38, p

Table 5 Secondary outcome measures: Results of one-way ANOVAs, means and standard deviations and effect sizes

| Mean scores (standard deviations) | ANOVA | Effect sizes | |||||||||

| Screening | Session 1 (Pre) | Session 3 | Session 6 (Post) | Follow-up | F (df) | p-value | Pre-treatment changes (Pre – Screening) | Post – Pre | Follow-up – Pre | ||

| df | (4, 88) | ||||||||||

| Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) | 7.87

(4.07) |

8.13

(5.15) |

7.52

(4.64) |

4.87

(4.53) |

4.83

(4.54) |

7.30 | 0.06 | -0.63 | -0.64 | ||

| Generalised Anxiety Disorder (GAD-7) | 8.78

(4.32) |

7.78

(5.08) |

7.39

(5.05) |

4.91

(4.09) |

3.83

(3.51) |

12.58 | -0.23 | -0.56 | -0.78 | ||

| Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (i) | 12.22

(3.77) |

13.22

(3.95) |

13.09

(3.90) |

17.57

(3.79) |

18.48

(3.84) |

30.11

(2.26, 49.73) |

0.27 | 1.10 | 1.33 | ||

| df | (3, 66) | ||||||||||

| ‘Maladaptive’ perfectionism | N/A | 69.70

(14.64) |

68.13

(14.47) |

61.48

(14.30) |

56.83

(13.79) |

14.62 | N/A | -0.56 | -0.88 | ||

Notes: (i) Greenhouse-Geisser correction applied & degrees of freedom listed in table; df: degrees of freedom

4.5.3.3 Hypothesis 3C, 4 & 5: Comparison between pre and post-intervention for process measures

In line with hypotheses, there were statistically significant improvements between pre and post-intervention and between pre-intervention and follow-up for self-compassion, beliefs about negative emotions and the ‘reappraisal’ emotion regulation strategy (p values d calculations indicated large effect sizes for these three process measures at post-intervention; at follow-up, the effect size for self-compassion and beliefs about negative emotions was large and the effect size for ‘reappraisal’ was medium. For self-compassion and ‘reappraisal’, there was no further significant change between post-intervention and follow-up (p values >0.09). For the BES, there was a non-significant trend for participant’s beliefs about negative emotions to continue to improve between post-intervention and follow-up (p= 0.03).

In terms of the emotion regulation strategy ‘suppression’, there was statistically significant decrease between pre and post-intervention (p= 0.003) but between pre-intervention and follow-up there was only a non-significant trend (p= 0.016).There was no significant change between post-intervention and follow-up (p= 0.71).Cohen’s d indicated a medium effect size for this emotion regulation strategy at post-intervention and follow-up.

4.5.3.4 Hypothesis 3C: Associations with reductions in self-criticism

Pearson correlations were used to determine whether reductions in self-criticism were associated with increases in self-compassion and ‘reappraisal’, and reductions in ‘suppression’ and unhelpful beliefs about emotions. For the HINT, in line with predictions, there was a strong significant negative correlation between changes in self-criticism and self-compassion [r(23)= -0.65, p= 0.001]. The correlation between changes in self-criticism and unhelpful beliefs about emotions, [r(23)= -.34, p= 0.11], ‘reappraisal’ [r(23)= -0.32, p= .13] and ‘suppression’ [r(23)= 0.24, p= .27] were non-significant.

For the SCRS, there was also a strong significant negative correlation between changes in self-criticism and changes in self-compassion [r(23)= -0.67, pp= 0.02] and ‘reappraisal’ [r(23)= -0.48, p= 0.02]. The correlations between changes in self-criticism and ‘suppression’ [r(23)= 0.30, p= .17] were non-significant.

Table 6 Process measures: Results of one-way ANOVAs, means and standard deviations and effect sizes

| Mean scores (standard deviations) | ANOVA | Effect sizes | ||||||

| Session 1 (Pre) | Session 3 | Session 6 (Post) | Follow-up | F (3, 66) | p-value | Post – Pre | Follow-up – Pre | |

| Self-Compassion Scale | 60.13

(12.65) |

62.13

(12.75 |

81.30

(11.75) |

85.04

(14.97) |

46.82 | 1.67 | 1.97 | |

| Emotion Regulation Questionnaire-Reappraisal | 27.48

(6.23) |

26.91

(6.37) |

32.48

(4.79) |

32.13

(4.95) |

8.73 | 0.80 | 0.74 | |

| Emotion Regulation Questionnaire-Suppression | 14.83

(5.56) |

13.04

(4.51) |

12.00

(5.18) |

11.70

(5.61) |

4.58 | 0.006 | -0.51 | -0.56 |

| Beliefs about Emotions Scale | 45.04

(10.98) |

41.87

(11.98) |

33.91

(12.75) |

29.78

(11.33) |

17.57 | -1.01 | -1.39 | |

5. Discussion

This uncontrolled pilot study investigated the feasibility and acceptability of a novel intervention targeting self-criticism in a student population. Changes in self-criticism and other outcome and process measures were also investigated by comparing scores at pre-intervention with those at post-intervention and two-month follow-up.

5. 1 Hypothesis 1: Feasibility

In line with the first hypothesis that the intervention would be feasible to deliver, advertisements on the university volunteer webpage and email circular were sufficient to recruit adequate numbers of participants for the study. Retention was also good; although 6 individuals who had consented to participate in the study withdrew before starting the intervention, only 1 dropped out once the intervention had started (due to a significant life event).

The inclusion criteria of a score of at least 10 on the WASAS was successful in selecting a participant sample who reported significant distress or impairment associated with self-criticism in the screening interview and who reported at least some benefit from the intervention. This study also provides information about the mean and SD scores on measures of self-criticism that could be utilized in relation to inclusion criteria in future research studies. It should be emphasized that although these participants had a significant level of impaired functioning due to their self-criticism, they were a student sample responding to an advertisement for a research study and were not a clinical population. Thus, future research would need to assess the applicability of these cut-offs to patient populations.

In line with previous research about gender differences in psychological help-seeking (Oliver et al., 2005), the majority of participants were female. Over 50% had experienced depression in the past which suggests that it may be helpful to intervene earlier. The majority of participants were also postgraduate students, so future research could focus more on recruiting undergraduate students or even those still at school or college. Research is needed into the prevalence of high levels of self-criticism in the secondary school/college population and the feasibility and acceptability of a similar intervention for this age group.

5.2 Hypothesis 2: Acceptability

5.2.1 Acceptability of assessment methods

In line with the second hypothesis that the assessment methods would be acceptable to highly self-critical students, the telephone screening appointment was described as a helpful way to introduce individuals to the study and specific therapists. Some participants would have preferred for this appointment to have been completed face-to-face due to the sensitive nature of the questions. This may also have allowed for greater rapport from an earlier stage.Future research could assess the feasibility of face-to-face screening, taking into account challenges such as the multisite nature of the campus, room-booking issues and the extra clinician time that would be required to book in sufficiently long screening slots. It could be that other formats, for example, Skype may be an appropriate way of providing individuals with the non-verbal therapeutic cues that are less evident over the telephone, whilst still being feasible for researchers to complete.

The weekly questionnaires were completed by every participant. However, qualitative feedback suggested that some participants found the full questionnaire pack to be too lengthy to complete. This study used several measures of self-criticism; this could be reduced in future research, and fewer process measures could be included. Some participants found it burdensome to complete weekly measures. Weekly assessment had been included in case of a high level of drop-out, however, as this was not a problem, the collection of data in future studies could be reduced to pre, post and follow-up.

5.2.2 Acceptability of the intervention

In line with the second hypothesis that the intervention would be acceptable to participants, the treatment rationale was rated as logical by 90.5% of participants and 100% either “agreed” or “strongly agreed” that the intervention was useful and that they would recommend it to others. Furthermore, only one participant dropped out after starting the intervention (due to a significant life event) which is also consistent with adequate treatment acceptability. At post-intervention participant feedback indicated that the practicalities of session appointments were also acceptable; all but one participant said that there were a sufficient number of sessions, and the majority of participants (76.2%) said that no changes could be made to the intervention delivery that would have improved participation. In line with some participant feedback, future research could consider offering a choice over frequency of appointments (for example, weekly or fortnightly), or offering evening appointments.

Participants engaged well with intervention protocols both within and between sessions. On average, participants reported spending over 2 hours practicing the intervention techniques each week. On average, participants read approximately 80% of session booklets, and described these as a useful way of recapping on the session techniques. This may provide an interesting avenue for future research; ‘guided self-help’, which commonly uses written psychoeducation components, are NICE recommended for common mental health problems (NICE, 2011), thus the effectiveness of a modified form the study intervention could be assessed within the context of, for example, an Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT) service.

In terms of the specific intervention techniques, on average, all techniques were rated as at least “somewhat useful”, and the mean rating for 6 out of 8 of these was “quite a lot”. ‘Decentering’ received the highest proportion of the top usefulness rating and at follow-up 68% reported using it at least “once a week”. ‘Decentering’ is thought to enable people to distance themselves from the content of their thoughts and emotions, and gain a sense of mastery over them (Gecht et al., 2014). In line with this, the qualitative feedback suggested that participants had learnt to control their self-criticism. The ‘compassionate reframe’ was the other most popular technique; 76% gave it the first or second highest usefulness rating, which was the same proportion as for ‘decentering’. Furthermore, at follow-up, approximately 60% of participants were continuing to use this technique at least “once a week”.

Although, on average, participants rated ‘compassionate behaviours’ as “somewhat” useful at the end of the intervention, at follow-up 68% were completing these “once a week”, making this one of the three most popular technique at this time point (in addition to ‘decentering’ and ‘compassionate reframes’).It is possible that initially participants found the idea of ‘compassionate behaviours’ threatening because they may have believed that they did not deserve to do nice things for themselves, but over time felt more comfortable with it (Gilbert, 2009).

Overall, there was nothing in the participant feedback that indicated that changes to the protocol are required. However, if the intervention were to be reduced in length, the findings suggest that ‘decentering’, ‘compassionate reframes’ and ‘compassionate behaviours’ may be the most appropriate methods on which to focus.

5.3 Hypotheses 3, 4 & 5: Changes in self-criticism and other outcomes and associations between the changes

5.3.1 Impact on self-criticism and associated impairment

As predicted, there were significant reductions in self-criticism and impaired functioning from pre to post-intervention and from pre-intervention to follow-up. The intervention had a large effect size for self-criticism and a medium to large effect size for impaired functioning. Overall, these findings provide preliminary indication that the intervention may be an efficacious treatment for self-criticism. However, due to the uncontrolled nature of the study, other explanations for the reductions in self-criticism and impairment cannot be ruled out. For example, the self-criticism may have reduced anyway with the passage of time. This explanation is less likely, however, given that the average time between screening and pre-intervention was 13 weeks (i.e. longer than the time taken to complete the intervention) and the changes between screening and pre-intervention for all study measures were non-significant, with ‘negligible’ to small effect sizes, compared with medium to large effect sizes between pre-treatment and post-intervention and follow-up. Also, paired t-tests showed that there were significantly larger changes between pre-intervention and post-intervention compared with screening and pre-intervention for measures collected at both time points. Nevertheless, further research using controlled study designs would be needed to confirm these findings.

Self-criticism and functional impairment continued to decrease between end of treatment and two-month follow-up. Indeed, although only 35% of participants had moved to scores below the ‘significant functional impairment’ range on the WASAS at post-intervention, this increased to 61% at follow-up. This may have been because the additional two months had given participants more time to practice the techniques and integrate them into their day-to-day life. It is also possible that the follow-up session helped to motivate or remind participants to continue applying the techniques as they knew they would be reporting back to their therapist.

In line with the reductions on the standardised outcome measures, the participant feedback highlighted that 100% “agreed” or “strongly agreed” that the intervention was useful. However, one participant indicated “neither agree nor disagree” in relation to both the statements that the intervention had reduced their self-criticism or improved their ability to cope with self-criticism. Although this participant had not benefitted in the two key ways intended, they reported that they had learnt to view things in a more positive light.

5.3.2 Changes in secondary outcome measures