How Influential Was Medical Understanding in the Implementation of the Contagious Diseases Act 1864

Info: 22575 words (90 pages) Dissertation

Published: 12th Nov 2021

Tagged: HealthHistorySocial Policy

Abstract

This dissertation’s leading research question is: how influential was medical understanding in the implementation of the Contagious Diseases Act 1864.

The aim is to clarify how far medicine, legislation and social attitudes, influenced or were influenced by the other in a complex, three-point relation, with venereal disease and female prostitutes as the shared subject between the three discourses. The prostitute has long been a cause of moral opprobrium, but this dissertation finds it was medical understanding that stimulated legislative action repressing this vice. Additionally identifying further repercussions of the Acts, including justifying the double standard; ensuring the continuation of male hegemony; solidifying the prostitutes connection with disease; securing the continuation of patriarchal control and bourgeoisie values; and objectifying the prostitute as a “necessary evil”.

In order to do this a range of sources have been consulted, notably with the Contagious Diseases Act 1864 and published medical papers at the centre of the argument. These sources assert the one-sided hegemonic and patriarchal views of society. However in light of an analysis of the subjective, religious or moral arguments such as presented in paintings, moralist speeches, and fictional literature, medical knowledge won significant influence both in government and throughout society. To carry out the investigation into Victorian medio-legal-social relations surrounding the CD Acts this dissertation is split into three chapters, with each allocated to answering leading questions that accumulate towards a final conclusion.

The first chapter focuses on the prime, surface reasoning for the Acts implementation; the second on why regulation of prostitution was the chosen solution; the third on medicines relation to patriarchy and male hegemony.

This dissertation concludes to shed new light the paramount importance of medical understanding to 1860’s legal and social, attitudes, understanding, power and control over not just the prostitute’s body as an object warranting regulation, but all the bodies of Victorian society.

Introduction

This dissertation derives its’ important from considering medical factors as the primary focus in relation to the Contagious Diseases Act 1864 (hereafter CD Act). Especial attention will be given to the prostitute as the focus of medical, legal and social intervention. Thus, the subject of this dissertation is medical understanding of venereal disease and sexuality, focusing on patriarchies interpretation and implementation of gynaecological understanding into legislation, consequentially justifying repressive legislation and societal structures.

Alexandra Wallis case study on the Contagious Diseases Acts forms an argument specifically influenced by the theories of radical feminism. The argument is centred upon how patriarchal society maintained the double standard, using medical evidence to enforce chastity, and punished women who transgressed moral ideas of respected female ‘angelic’ behaviour.[1] The theory of radical feminism is used to inform a specific reading aiming to find the influence of patriarchy in the repression of females.

Additionally, scholars such as Judith Walkowitz and Kingsly Kent focus on gender-power relations, particularly how the CD Acts were catalyst to activism across the social classes and the Acts repeal the beginning of women liberation. Rather than focusing on the cultural aspects of gender-power relations in society, uniquely this dissertation will investigate the justification of the CD Acts from the perspective of medics and the extent to which medical knowledge influenced government decision regarding the CD Acts legislative measures.

Interpreting how in the Victorian Age each opposing group of “pure” women verses the prostitute and their male counterparts were defined less by social opinion, as further scholars such as Lucy Bland have considered, but more by medical evidence.

Meanwhile Foucault has extensively studied the dynamics of power from a psychological perspective, finding ‘sexuality in the eighteenth century Europe began to be an object of repressive surveillance and control’.[2] Foucault argues that ultimately power is a function of knowledge.[3] Knowledge was held as a monopoly by medics, military personal, and government. This dissertation will consider how hegemony and patriarchy utilised medical understanding to maintain power over social structures and in particular the female body.

Following on, this dissertation will develop to argue that the measures implemented by the 1864 CD Act were influenced by contemporary medical understandings as well as created: firstly as a solution to ensure the health of the nation; secondly to enforce the continuation of male hegemony through medical justifications; and thirdly criminalise the prostitute. Contmporary Joyce states ‘[a]dministrative machinery and medical technology facilitated their [CD Acts] operation’.[4]

The focus will be upon contemporary medical understandings concerning sexual health and gender differences during the 1860’s, in particular leading up to the 1864 Contagious Diseases Act. An Act which was of paramount importance during Victorian times, and key as evidence to understand the views patriarchy maintained and attempted to legally enforce upon society. Additionally, the Acts have been considered a key moment in legal history for its’ importance to the battles of gender-power relations, however this dissertation investigates the Acts importance as a key event to governance of the body through medio-legal alliances.

Furthermore investigating the social opinion surrounding both medical and legal discourses to gain a comprehensive understanding of medico-legal-social relations. In hindsight the Acts introduction is thought to have been influenced by a combination of moral and social beliefs. However, these beliefs were mainly rooted in medical understandings. Furthermore, subjective opinion was justified by medical evidence. Rising concern for venereal disease was the primary, but not standalone, reason for investigation and implementation of the Acts. This dissertation investigates to what extent the multifaceted reasons towards the CD Acts were affected by medical understanding.

To answer the overarching title investigation this dissertation will analyse how contemporary medical understanding was used as evidence, influence and justification to the creation of the 1864 Contagious Diseases Act. Highlighting in particular how the Act used medical understandings to solely blame women for venereal disease and thus condone discriminatory action. Although there existed discrepancies in arguments presented by medics, who notably belonged to the hegemonic class, the dominating views are those collected, enforced and reflected in legislation.

The views of hegemonic persons are the focus as the most abundant surviving sources and the core representatives of medical and legal views. This dissertation will continually question how medical and social concern for venereal disease insinuated itself into legislation, and consequently upheld male patriarchy, hegemonic power, and the double standard. Recent scholarly material provides academic debates and hindsight considerations of contemporary sources. Combining scholarly material with the 1864 CD Act and contemporary medical publications, which will be considered as primary sources, will enable thorough analysis of the levels of Victorian medical understanding surrounding 1864.

The chapters focus on firstly interpreting the influence medical understanding had on legislation’s reasoning for the Acts introduction; secondly medical influence towards the chosen solution in sight of problems warranting legal intervention upon the prostitute’s life; finally leading onto to consider how medical understanding influenced and was affected by the attitudes towards woman in society.

Chapter One: Reasoning

This first chapter sets out the contemporary context leading to the implementation of the CD Act 1864. Highlighting prostitutes intrinsic link to, even identification as, disease. Combining this identification with varying medical investigations and statistics proving the prevalence of disease and prostitutes cumulatively warranted grave concern for the nations health. Furthermore focusing investigations, statics and medical concern upon the armed forces reveals the prime reason for the Acts introduction was to reduce venereal disease in the armed forces. Medical investigations and evidence forced legal intervention.

1. The prostitute and her intrinsic link to disease

Far beyond the prostitutes association to crime and poverty[5] warranting her branding as ‘The Great Social Evil’ was the heightened concern for the prostitutes as the carrier of venereal disease: destroying the sanctity of the family; respectability of society; the nations health; and strength of the army. ‘When studying the effects of venereal disease on the public, doctors who perceived prostitutes as the cause of illness rarely viewed them in a sympathetic light’.[6] It was disease that centered the prostitute as a pinnacle of societal concern.

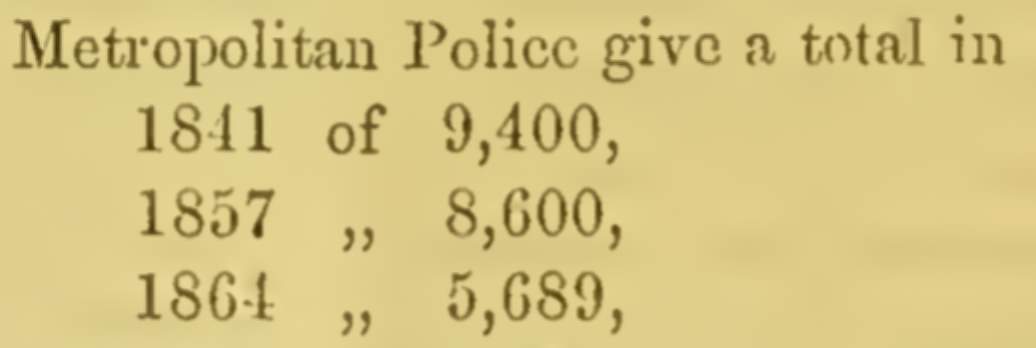

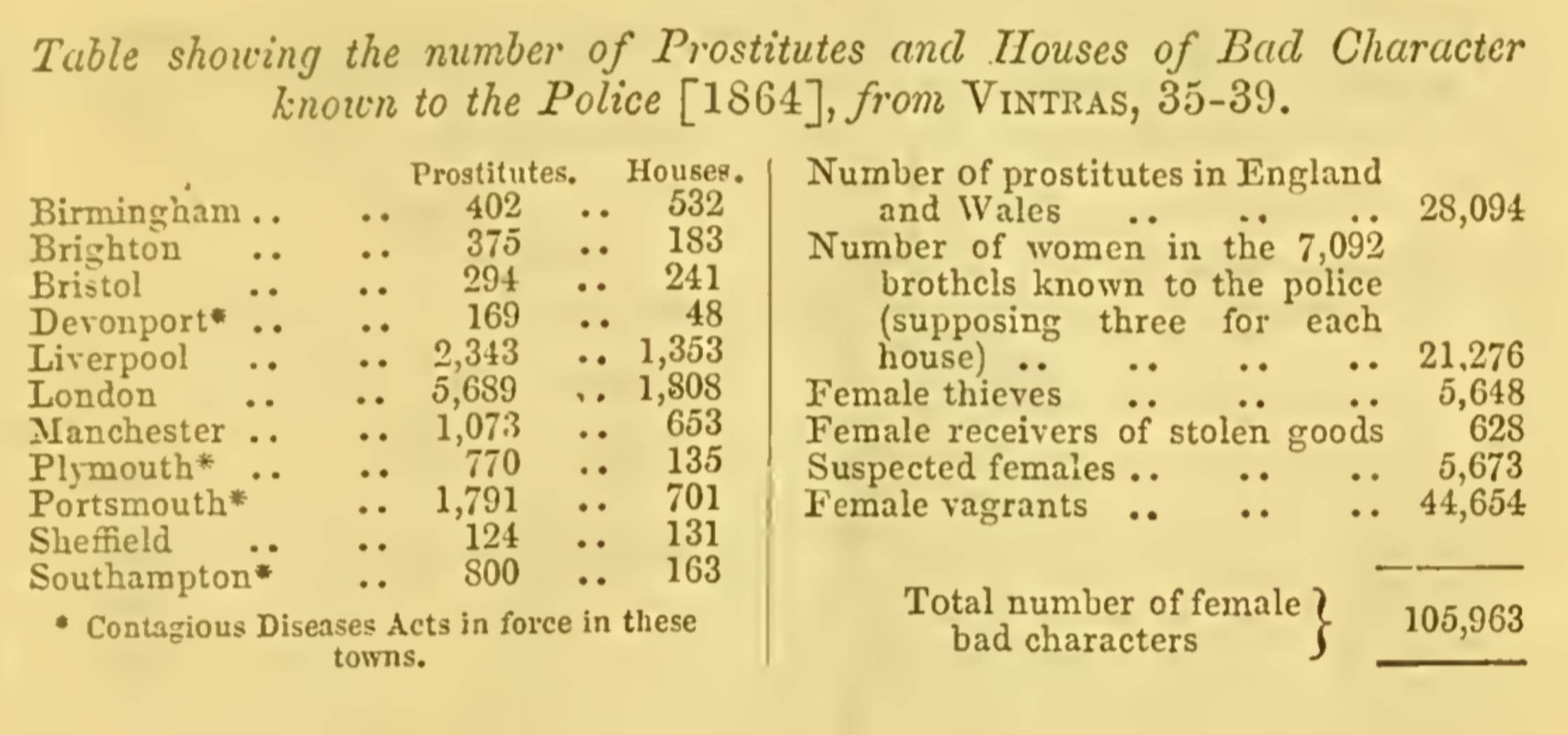

Numbers varied not least due to variations in definitions of a prostitute: from today’s lasting definition of sex by monetary exchange[7] [8], to living but not married to a partner; birthing illegitimate children; even having relations for pleasure as this was deemed improper. Doctors Ryan and Campbell, along with Mister Talbot estimated 80,000 prostitutes in London. Yet the Metropolitan Police, due to differences in their definitions and individual inspectors arrests against police guidelines, estimates vastly different numbers. Perhaps the police wished to appear more effective in their policing. Whereas others, especially doctors, may have exaggerated numbers to pressure legislation.

Estimates varied greatly from 5,000 to 80,000. Contemporary doctors Duchâtelet and Barr claimed ‘prostitutes could have 15-20, and 20-23 clients a day respectively’.[11] Correspondingly doctor Deakin noted encounters were varied: estimating from one to twenty every day.[12] Scholar Joyce highlights that due to post-Victorian medical advancement the nature of contagious disease is that ‘[a]ll might become infected; if the woman herself was healthy, it was likely that one of her clients would not be.

An anonymous doctor calculated the yearly spread of venereal disease: a total of 1,652,500 people infected per year from just 500 initially infected women’.[13] Equally discrepancies were rife, lower numbers, such as 219,000 annual cases in London.[14] Additionally ‘medical officials calculated that 7% of all those hospitalised under the Poor Law were infected, and [contemporary] Hemyng noted that syphilis was found in around a fifth of sailors’ women’.[15] Whilst women’s activist ‘Mrs [Emmeline] Pankhurst believed that 75% of all men had a venereal disease’.[16]

More statistics spread/prevalence disease

P34 deakin

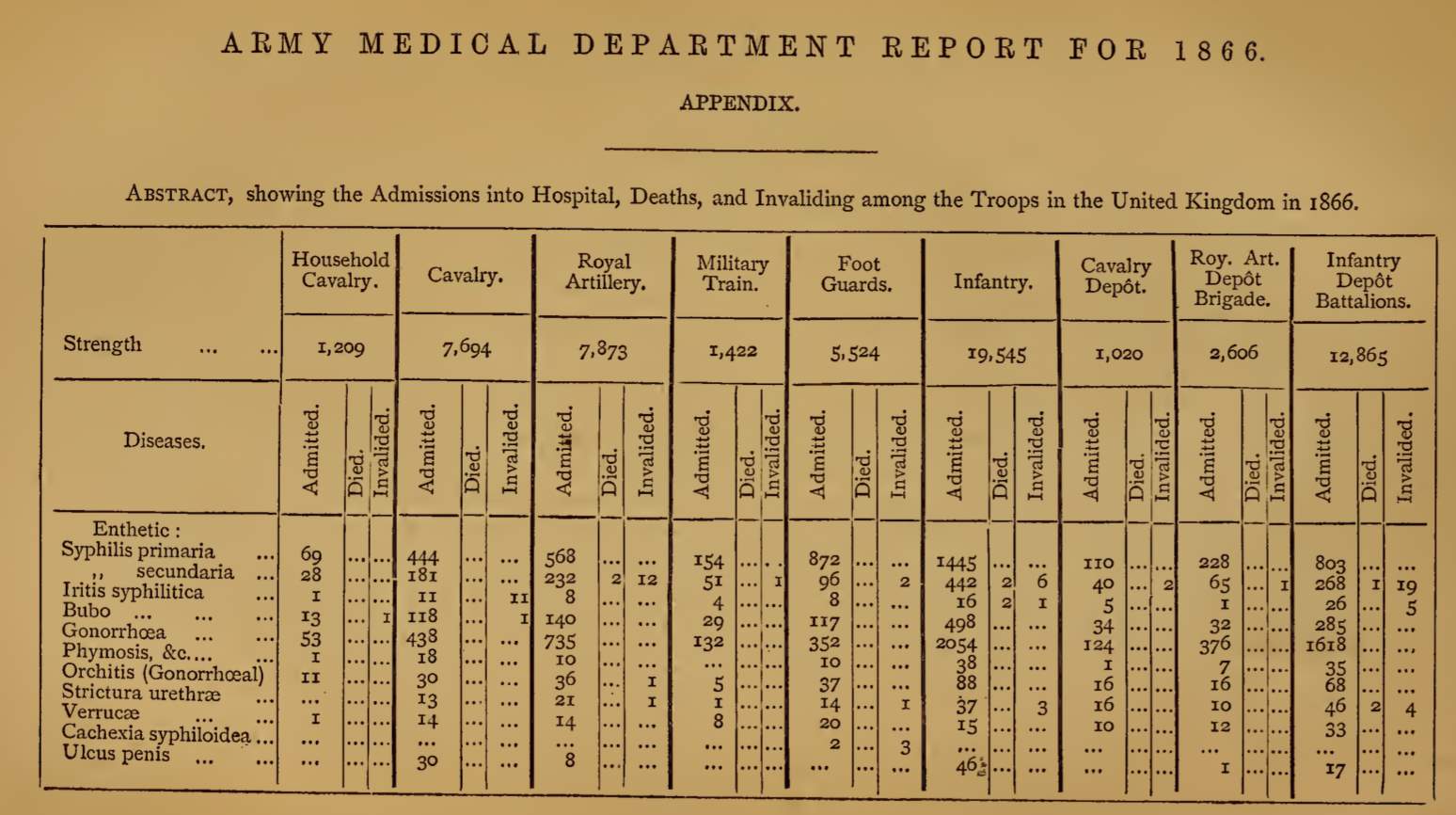

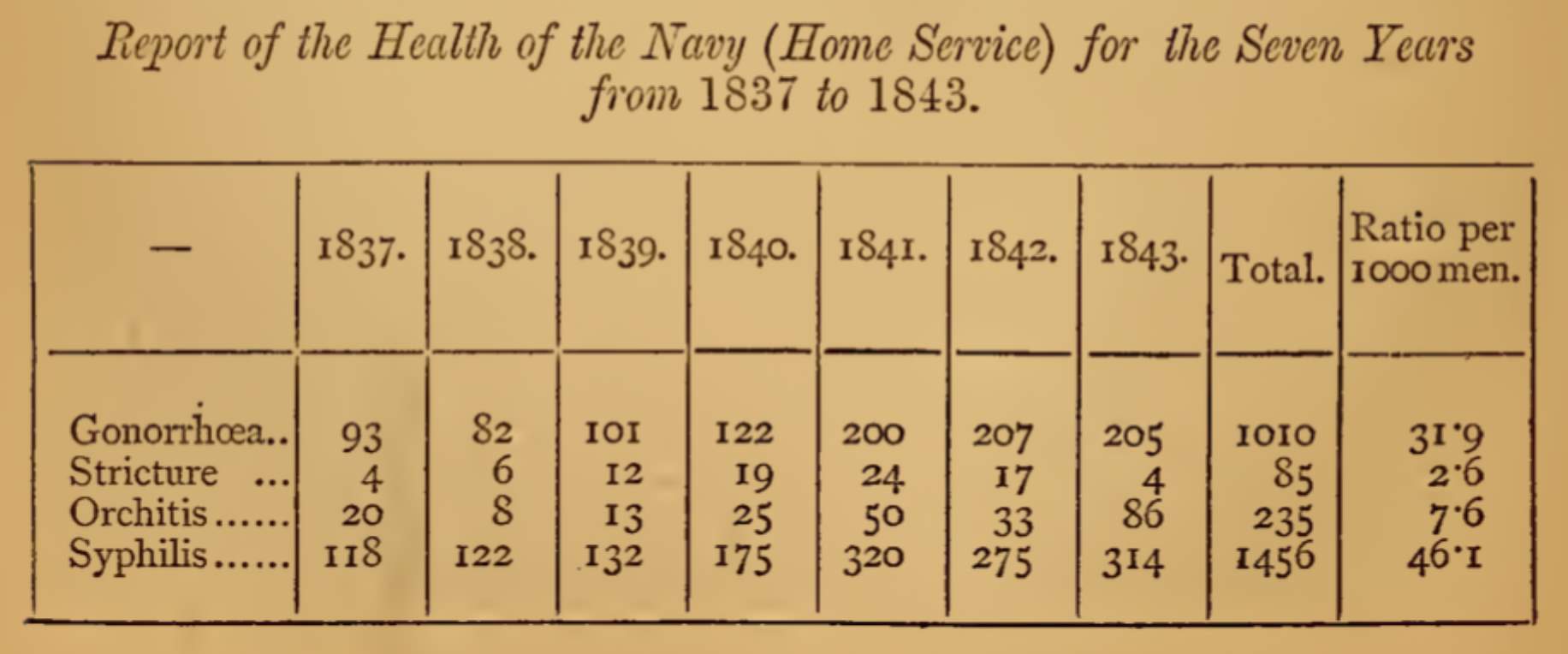

Figure 1

The ‘Home Service’ refers to men employed in England’s ports and coasts. This is significant as it eliminates the potential of having contracted venereal disease from abroad.[17]

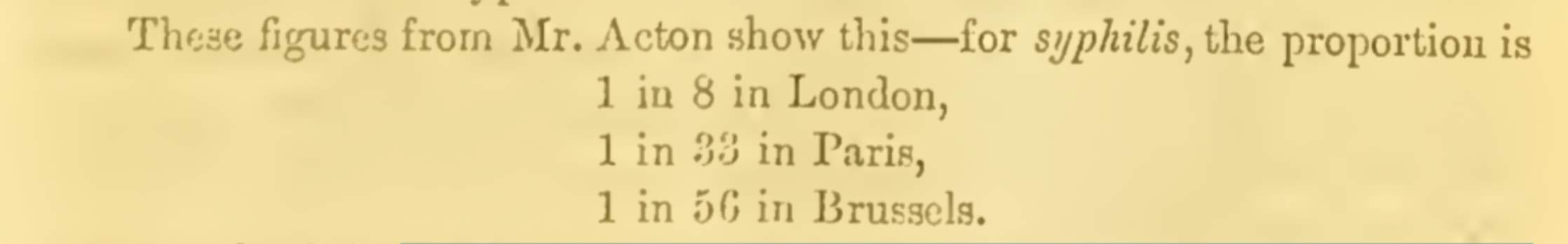

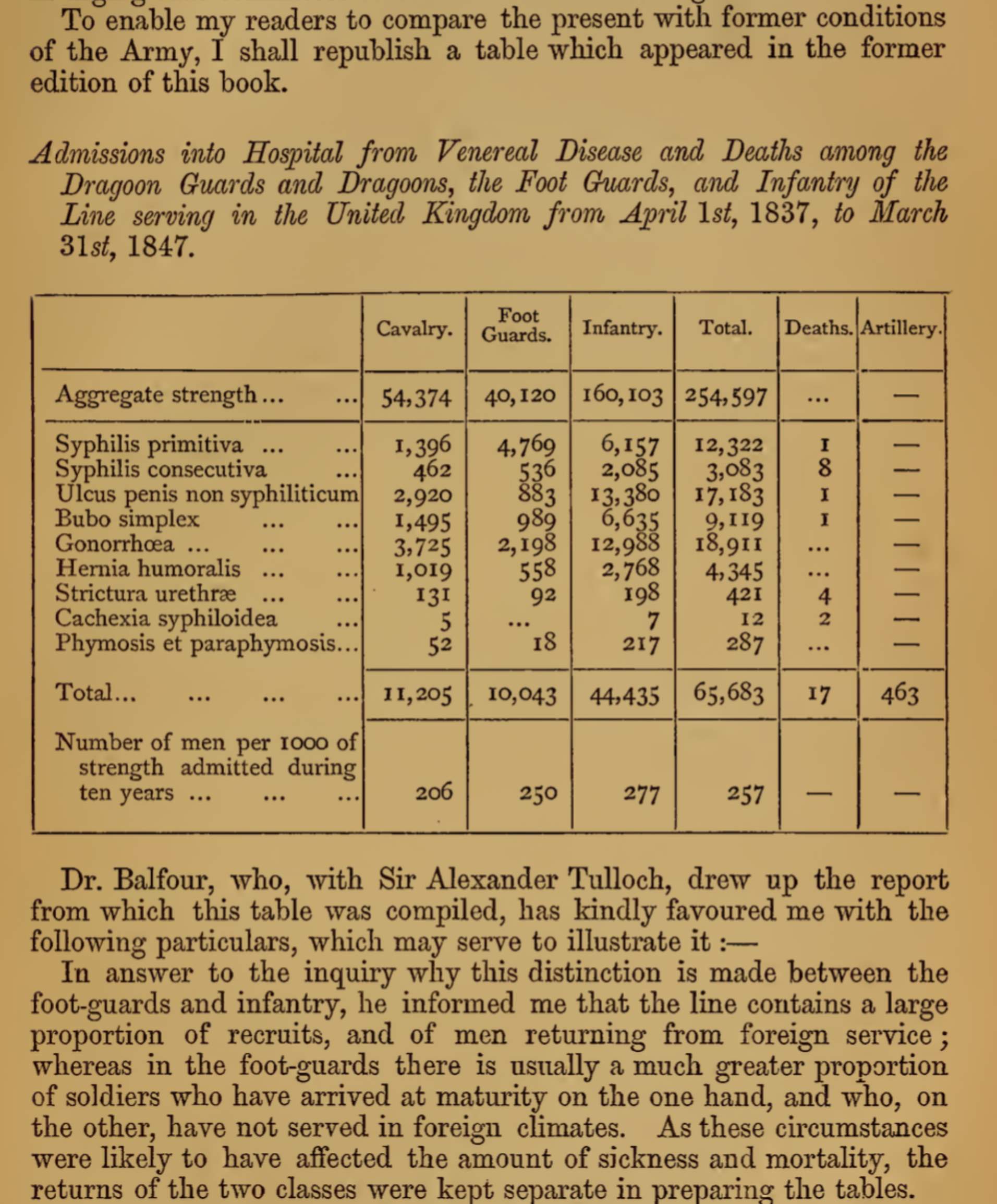

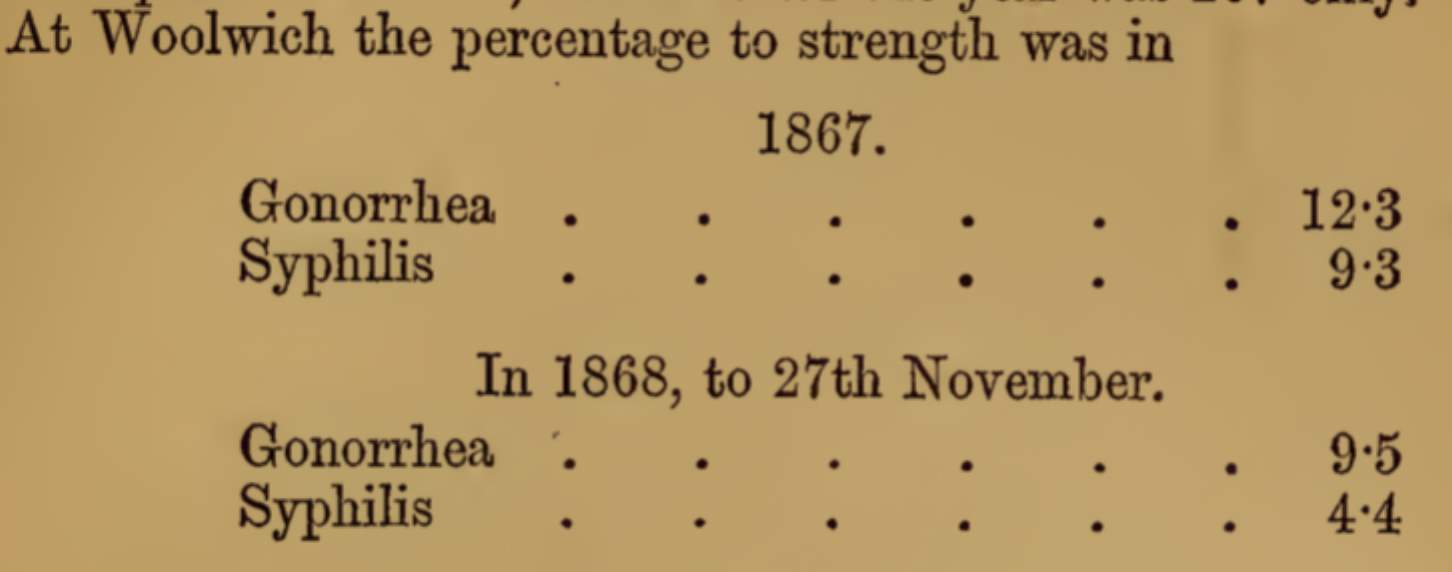

Figure 1 demonstrates rising cases of venereal disease over seven years whilst Figure 2 summarises the heightened levels of syphilis in London compared to abroad according to Acton’s investigations. The prevalence of disease was undeniable, frightening and threatening to England’s’ strength and reputation. Discrepancies depended on definitions, speculative calculations and vested interest from a class, moral or gendered standpoint.

Scholar Fraser concludes from his studies of statistics that prostitutes were considered during the Victorian era, as well as more recently, ‘[t]hus dangerously diseased’[19] adding ‘prostitutes were seen as directly responsible for debilitating the health of the male population’.[20]Lacking knowledge only increased the fear of disease and its exclusively female carrier. Although the numbers of prostitutes and spread of venereal disease was subject to speculation disease was undeniably prevalent.

When referencing the prostitute, scholarly works and literature portray her as almost intrinsically connected with disease. Evidentially, contemporary doctor Hemyng wrote ‘her disease contaminates the very air, like a deadly upas tree, and poisoning the blood of the nation’.[21] Furthermore medical opinion stated ‘Syphilis, doubtless, is the product of prostitution’.[22] Medicine identified females as the sole cause of disease and so intrinsically connected prostitutes to disease that prostitutes were personified as venereal disease itself. Using hindsight professor Bland describes venereal disease as ‘the contagious disease that men are apt to catch by dealing with infected women’.[23] Stereotypes of ‘fallen women’ as dirty, diseased, impure, immoral, promiscuous and poverty stricken pervaded Victorian society through literature. Cases to the contrary were ‘exceptional’[24]:

Thus the fallen woman becomes a symbolically charged site, associated with the dirt of the lower classes, epidemic disease and contamination, and the decline of the English race — responsible for this decline both by spreading disease and contagion and by bearing weakened offspring, ‘one-half of whom die before they reach the age of five years’. This is the context out of which the Contagious Diseases Acts grew.[25]

In other words the foundations of reasoning the prostitute as ‘the Great Social Evil’ was her figure as a vehicle of and symbolic encompassment of disease. Society believed offspring morality rates were higher among prostitutes due to her sexual promiscuity, however considering modern understanding it was more likely mortality was due offspring being born to mothers in poverty. Victorian prostitutes were almost exclusively situated in poverty, meaning there offspring were malnourished, venerable to illness or abandoned. Yet Victorian ideological framing overlooked these reasons in favour of medically branding disease of the prostitute as the root cause of societies evils. Despite the variations in statistics concerning the numbers of prostitutes and contagion it is clear venereal disease and its causality was of grave Victorian concern.

2. What was the prime reason for the Contagious Diseases Acts introduction?

By 1864 concern for venereal disease among the armed forces, alongside medical warning and national consciousness, had risen to levels requiring address. No longer could the state stand in a position refraining from introducing new legislative controls concerning prostitution. Although considered a danger to societies morals, the prostitutes’ primary danger was her profile as a cause of disease. In Victorian society:

Acton, the Lancet, and other influential medical sources may have previously established a climate of medical concern over the incidence of syphilis in the general population, but it was the loss of man-hours and the mounting statistics on venereal disease among troops that finally spurred legislation on the subject.[26]

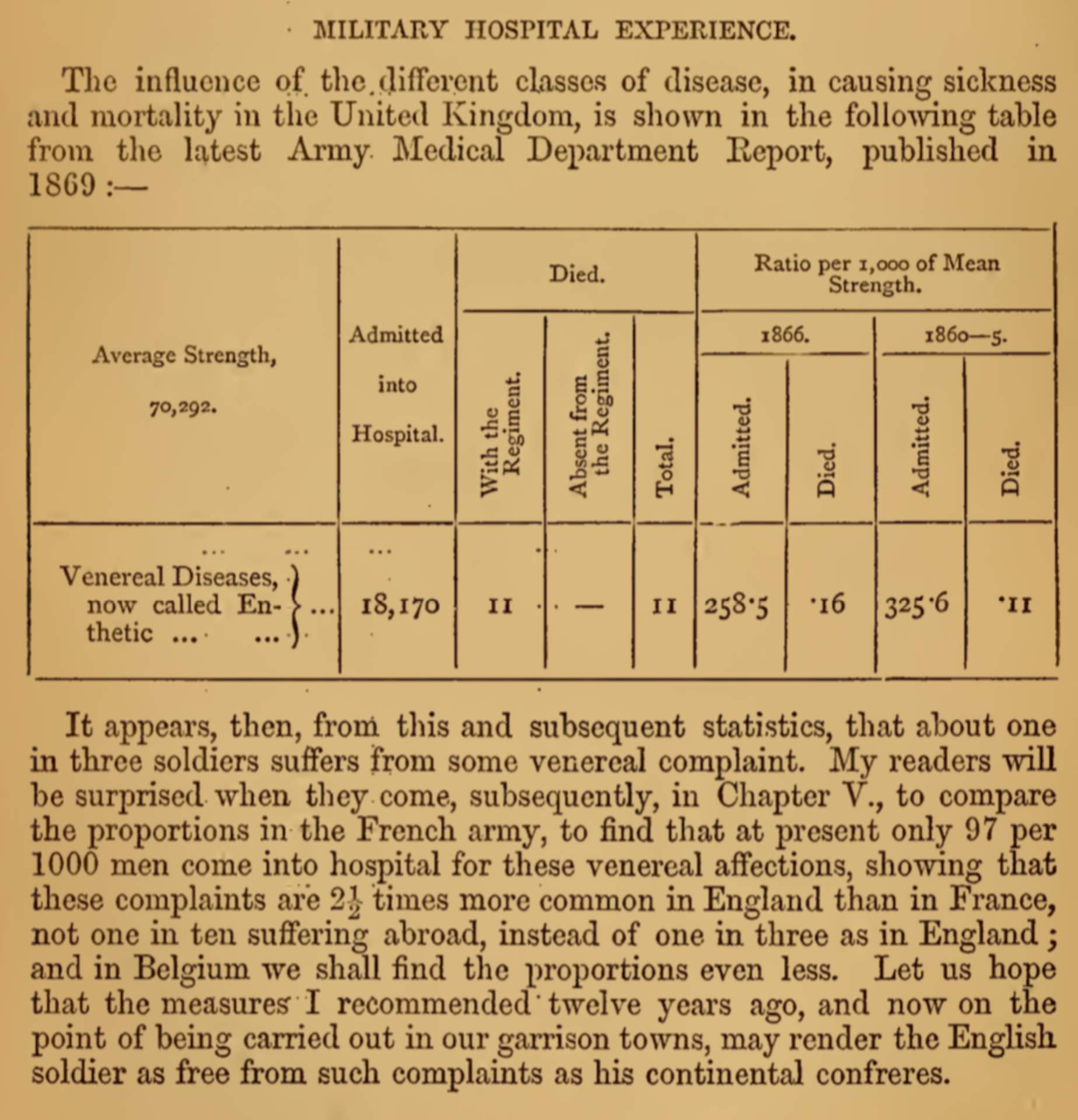

The Act evidences governments prime concern to be that of rising venereal disease especially among the armed forces, because disease ‘was having a dramatic impact on fighting forces’[27] morality and fighting ability. Efforts were aimed towards reforming the army into a more celibate force. To ‘increase the efficiency of the armed forces by decreasing the cost of treating venereal disease amongst the bachelor troops’.[28] Additionally, treatment was lengthy and thus caused problematic lengths of time away from fighting. In 1857 statements varied from twenty-two days to six weeks incapacitation from duty.[29] From 1864-1868 the ‘expense of venereal patients was £4165’.[30]

‘By 1864, one out of three sick cases in the army were venereal in origin, whereas admissions into hospitals for gonorrhoea and syphilis reached 290.7 per cent per total troop strength’.[34] Two years prior concern had already risen enough to warrant investigation: ‘[i]n 1862 a committee was established to inquire into venereal disease in the forces, and on its recommendation the first Contagious Diseases Act was passed in 1864’.[35]

The committee’s findings combined with further medical reports, statistics and arguments of varying radical recommendations by surgeons and doctors such as Deakin, Acton, Sanger and Pearson were highly influential in raising concern for disease that led to the creation of the 1864 CD Act, particularly influencing the opinion disease would be reduced by repressing females exclusively. The 1864 Contagious Diseases Act, with expansions to its areas of operation in 1866 and 1869, was ‘introduced as exceptional legislation to control the spread of venereal disease among enlisted men in garrison towns and ports’.[36] The Acts introduction was a primary combination of medical arguments and medical evidence concerning disease as ‘Evil’ to the strength and health of the nation and its empire.

Chapter Two: Solution

The previous chapter highlighted the prevalence and nations concern for disease. Particularly finding, despite rising public concern, medical arguments and factual evidence revealing the prevalence of disease among the armed forces stimulated government to finally introduce legislation. This second chapter aims to lead on from the first chapter’s notion that the prostitute was identified as the root problem threatening the nations strength: investigating why the government opted for regulatory legislation; how this changed the hospital system; and medical arguments relation the religion and morality.

3. Why did the government favour regulation?

The prostitute was ‘regarded as a social leper’[37]; to introduce legislation against her would criminalise her and thus confirm her status as a danger to society. The prominent contemporary attitude favoured regulation, as opposed to management or eradication, of prostitution to ensure safety from disease whilst maintaining service to male sexual demand. Both health and demand were centred in beliefs of medical necessity.

Disease was prominent at the centre of legal debate and root of all problems concerning morality, civil rights and secularism. All groups either for or against the regulatory actions enforced by the CD Act shared the state’s attitude that the prostitute was an object requiring intervention. Legal institutions, medical practitioners, police, religious groups, repeal and reform activists, all ‘share[d] the language of disease, the construction of ‘prostitute’ as a category authorizing intervention into working-class women’s lives’.[38] The act is evidence of the state favouring argument for regulation and surveillance, [39] having accepted that prostitution was inevitable and beyond eradication.

Acton and Sanger’s studies were upmost influential in contemporary thinking, fuelling the opinion men required sexual satisfaction as a matter of biology. Although Miller considered these ‘unsafe guides’ he still concluded ‘[s]uppression is absolutely impracticable, inasmuch as the evil is rooted in a unconquerable physical requirement’.[40] Acton wrote prostitution is ‘an inevitable attendant upon civilized[…]population’.[41] Sanger argues it would be best, ‘instead of trying to extirpate the evil, to place prostitutes and prostitution under the surveillance of a medical bureau, in the police department’.[42] The Act enforced laws meaning ‘Common prostitutes’ could be identified by special plainclothes policemen and resultantly sanctioned to fortnightly internal examinations. If found to be infected with gonorrhoea or syphilis the woman would be interned into a certified lock hospital for a period not exceeding nine months.[43]

Having deemed, by biological study, prostitution a ‘necessary evil’ the government deemed regulation the measure by which the demand for sex would still be fulfilled, but more so the demand for safer sex would be supplied through reducing the prevalence, and thus contraction, of venereal disease.

Ruling powers opted for regulation in 1864 despite the concern for preventing the causes of prostitution and caution against legally advocating prostitution. This was largely due to moral obscurity and a patriarchal ideology to fulfil the male desire for sex and power.[44] The contradictory existence of prostitution is that through its continued existence to satisfy male sexual desire, the respectability of middle and upper-class society could be upheld.

Having reasoned the major problem with prostitution was not its existence, but the disease associated with it, lawmakers reasoned regulation to reduce disease was the preferable action. Ordered by parliament, the February 1882 Report from the Select Committee on Contagious Diseases Acts consists of seventy-one witness interviews including ‘police officers, priests, physicians, a superintendent of a lock hospital, and nine males and six females’. [45]

The report mostly appraises the Acts regulational methods despite societal testimony from typically lower-class women criticizing them. This could be because of the government’s interest was to interview those who aligned with their views and provided testimony as to the effectiveness, necessity and thus continuation of the Acts in opposition to an increasingly unignorable repeal campaign, which fought on moral and religious grounds. The Acts demonstrate the prevailing forces to be legal, medical and police intuitions desiring to exert control over the prostitute’s body: aiming to exert hegemonic ideologies on her rightful health and actions as defined by biological study.

4. How did the law change the hospital system in response to the demand for repression and prevention?

Prior to 1864 an unregulated voluntary system operated ineffectively. Penitentiaries, asylums and lock hospitals were expensively inefficient and inadequate to cope with disease, this meant women were left to their own devises whereby they avoided the horrific conditions in favour of enduring worsening venereal disease of which neither they, nor medics, understood fully.

In response to the need for repression the 1864 Act changed women’s interning into a lock hospital to involuntary, thus further removing women’s autonomy. As well as repression ‘[t]he unsanitary and neglected condition of female patients [in lock hospitals] convinced doctors like Lowndes and Lane that diseased prostitutes needed to be interned on a compulsory, rather than voluntary, basis’.[46]

Responding to the needs for preventative strategies against diseases doctors also stressed the paramount importance of compulsory education in sanitary measures. Cleanliness would help especially with diseases such as secondary skin infections associated with syphilis. The CD Act evidences government responded to doctors rising demand for prevention, not just the treatment, of venereal disease as previously. Overall, repression and prevention was appealing as it supported the paramount aim to reduce venereal disease. Furthermore, ‘[t]he medical profile of the female patients, as reported in medical journals, tends to support Lane’s observation that women only entered the lock hospital in an aggravated state of disease’.[47]

Thus introducing an involuntary system was believed to help intern women at earlier stages of disease. Resultantly providing greater chances of healthy recovery. Additionally interning a prostitute on an involuntary basis minimised her time on the streets: it was considered new educational measures had greater chances of success the less time she had spent practising trade. But also crucially less time to become morally corrupt or infect others with disease.

Education measures aimed to reform a woman to re-enter respectable society, practising sanitary, moral and domestic behaviour. The surface reason was to reduce venereal disease, however two joint, primary yet unwritten reasons medical and government forces supported repression and protection was: to reduce the number of “unrespectable”, “impure” women and their time on the streets; and to enforce patriarchal belief women belonged in the private sphere, believing it was hegemonic forces duty to protect women from straying into the public sphere.

Venereal disease was evidence of betraying her role, and should she stray be – depending upon which opinion is consulted – punished or returned to the private sphere as quickly as possible. Marriage was considered the optimum role for women and one that, if the prostitute avoided death, could gain retribution.

5. How did medical arguments prevail over religious and moral arguments? Or, did medical arguments reinforce religious and moral arguments?

Medical arguments offered justification against moral arguments dissenting prostitution. The existence of medical understanding supported the regulation of prostitution to ensure sexual safety from disease, demonstrating specific concern for health: in other words aiming to overcome medical problems whilst dis-concerning itself with moral problems or gendered inequality debates reasoning the end of prostitution; or introduction of examination or repression of male clients. Contemporary medical understandings such as advocating women the carriers of disease and males sexually animalistic were considered fact. Medical fact offered grounding for the gendered or moral ideological manipulations that lead to controversy. In fact the undisputed evidence that the CD Acts had reduced venereal disease meant repeal campaigns focused on the Acts moral and patriarchal incriminations, because the medical benefits to vastly improving the health and strength of the nation were an undisputable positive result. Acton wrote ‘strong testimony is borne to the benefits…Prostitution appears to have diminished, its worst features to have been softened, and its physical evils abated’.[48]

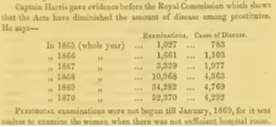

Figure no.?

Figure

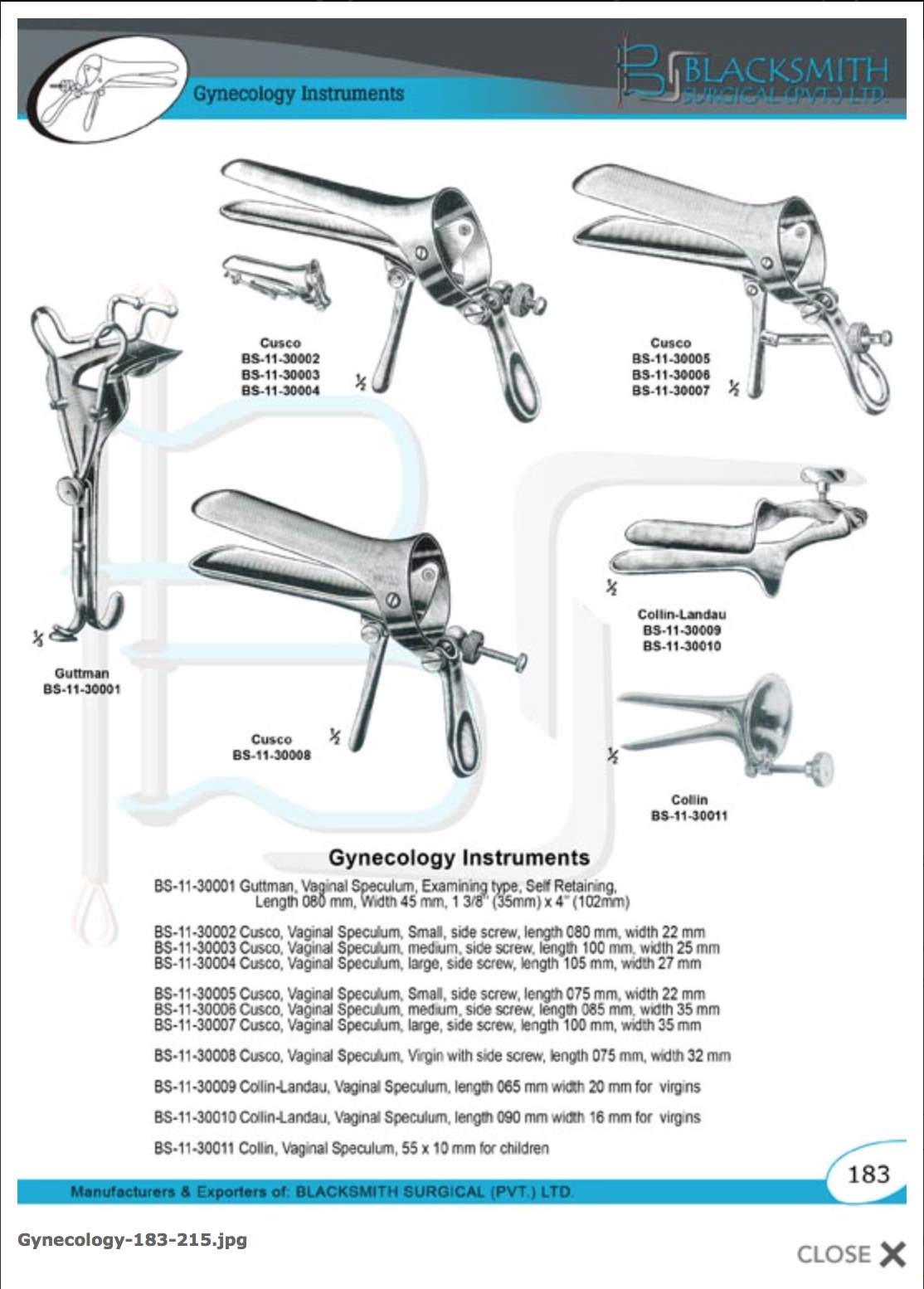

Disagreements concerning medical treatment and examination were criticized on their moral practise rather than their effectiveness. An instruments effectiveness maybe criticized in hindsight as unnecessarily brutal however at the time Victorian’s had no better methods. In the case of the vaginal speculum its’ discomfort is difficult to overcome even by modern developments. Considering the ‘speculum’s history is inextricably linked to extreme racism and misogyny’,[51] its’ use has always been disputed; yet ‘it’s hard to improve on the design’.[52] Therefore medical practice enforced by the CD Acts was hard to criticize on a scientific level. Evidence which, at the time, was taken as correct.

A vaginal speculum from the Victorian Collection at J. Ward Museum. Measuring Length: 110mm x Width: 40mm. Made of stainless steel. [53]

This illustration from a 21st Century supplier of medical instruments demonstrates the variation of women’s vaginal size, including differences in virgin’s and children, is accounted for. Yet the design in strikingly similar and equally a source of great discomfort.[54]

Whilst both religious and legislative avocations came under questioning, legislative attitudes, by boasting undisputable factual medical evidence, were able to rise against more subjective, personal opinion regarding morals. Moral and religious arguments gained support for the repeal of the CD Acts regulationary measures, whereas medical arguments were more difficult to oppose as they were founded in scientific justifications.

The repeal movement drew its greatest force from religious and moral arguments, whose subjectivity is potentially the reason it took so long to gather enough opinions for the reconsideration of the Acts immoral values leading to eventual repeal in 1886 to outweigh the statistically proved medical benefits of the new legislation reducing venereal disease. Where religious instructions and morality advocates sex outside marriage as unmoral and thus prostitution unacceptable, medical understandings advocate prostitutions continued existence as necessary to satisfy males until they have the financial status, or are not military enrolled, to be married. Additionally where God teaches sexual indulgence is ‘fornication, a flagrant infraction of His moral law’[55] because intercourse should be solely for procreation,[56] contrastingly sexual indulgencies are considered an undeniable demand determined by physiological law,[57] therefore supporting regulation of prostitution.

Medicine overruled religion in the view of the rule-making majority. Although medicine and religion jointly maintained that respectable women did not receive or seek sexual enjoyment, rather their innate purity was maintained until suitably married to fulfil their biologically founded natural desired duty to procreate. In this instance, thus fulfilling her role conclusively defined by medicine and religion, and enforced by law. Additionally, referring to the ‘Bible, it was believed, had laid down a subordinate role for women’.[58]

Art and literature also held influence on views towards prostitution, but again these were weakened by their lack of factual evidence, rather they were open to subjective interpretation and personal vested interest to sell their work. Sales could be achieved by causing controversy or adhering to popular opinion, thus fiction works are highly varied and not a source upon which government could strongly justify the CD Acts measures. Although these materials influenced social opinion it was medical evidence and arguments that gave strength and force to repressive legislative measures.

The Outcast by Richard Redgrave (1983).[59]

Legislation represents the upper class views and interests to retain patriarchy, the sanctity of the family and hegemonic control. Arguments debating repression, protection, elimination, other legal measures or personal sympathies were open to subjective personal opinion deeply dependent on class and gender, even within art. Art visually exemplifies society was rife with debate and symbolized how views can vary based on personal standpoint. Part of the strength of medical arguments originated from medics agreement to a greater extent. Redgrave’s painting The Outcast demonstrates the powerful opinion of the father to disown any disgrace and threat to his family structure. As despite the rest of the unfaithful daughters family, including her brother, pleading against the father to let her stay the hegemonic force, symbolized by the father, prevails to outcast her into the dark, cold, unforgiving night. Furthermore, Rossetti’s painting Found raises questions as to whether the prostitute is being punished or saved, accepting or rebuking help. Notably throughout Victorian art and literature the elder male was the dominant, controlling figure.

Past and Present, No. 1 by Leopold Egg (1858)

Past and Present, No. 2 by Leopold Egg (1858)

Past and Present, No. 3 by Leopold Egg (1858).[61]

Augustus Egg’s series Past and Present centers upon the fallen women, particularly the consequences of bleak prospects and poverty for her, her legitimate and illegitimate children. Therefore highlighting the problems unfaithful women selfishly brought upon future generations. Ironically these poverty stricken women would likely be tempted by prostitution in alternative to brutal workhouses.

Medical journals, legislation and mortality statistics provided concrete fact to the characteristic of the ‘fallen’ and ‘angelic’ women in paintings, novels and poems of the time. Often showing that in society existed a simultaneous revulsion alongside a fascination with and lust for the fallen women, but always with a prevalent concern for her diseased status.

Societies opinions varied from scorn to sympathies, portrayed in literature such as Dicken’s Nancy and Reynold’s Rosa Lambert who are shown in a sympathetic light undergoing great hardship to stay alive, and ultimately die to save others. However bourgeoisie scorned these characters, considering the prostitute with distain for she transgressed their biologically reasoned ideal standards and was symbolically synonymous with disease.

Opinions towards prostitutes varied largely depending on class however opinions were also depended on gender and, where some may have questioned the morality of the double standard or desired to extend charity towards prostitutes, biological fact reasoned male dominance; practice of sexual exercise; physiological suitability supporting the continuation of separate spheres in society’s structures; and centering prostitutes as a vice but necessary outcast group to be repressed.

Further fictional works were representative of widespread Victorian ideology, for example ‘Egg’s pictures demonstrate how in Victorian England the full weight of the moral code fell upon women. A man could safely take a mistress without fear of recrimination, but for a woman to be unfaithful was an unforgivable crime’.[62]

Medicine strengthened this ideology and rebuked prior uncertainties or oppositions to legislative measures enforcing these social structures. Yet notably painters were of the bourgeoisie classes; the images of condemnation were insinuated with their ideals. The poorer the individual the more sympathetic towards prostitutes they were as they were more likely to face choices between starvation, the workhouses, or prostitution. Some working class husbands supported their wife or daughters prostitution to earn income.

Often prostitutes worked on a seasonal basis with the tide of economic difficulty and demand; in particular the seasonal visitations of sailors to ports. However the government was interested in reducing venereal disease and maintaining power structures in their favor. Medical evidence and arguments provided both unquestionable reinforcement to these beliefs as well as factually, unquestionably clarifying the importance of introducing legislation to safeguard the future of the nations health, but also safeguard patriarchal and hegemonic power.

Due to opposing views, medical evidence was presented as fact to disguise patriarchies self-interests. Furthermore, throughout all fictional or non-fictional material the fallen woman’s affiliation with dirt, darkness and disrespect demonstrates concern for disease was omnipresent. The proof provided by medicine of venereal disease prevalence, and factual rooting of disease cause into female’s biology, was the judgment from which the CD Acts reached fruition.

Also, contemporary doctor Deakin acknowledges the CD Acts were introduced on the pretence of preserving public health but expresses a personal belief that moral, social and political elements are the key reasons for the act necessity.[63] Medical evidence was fundamental in providing reasoning and justification for the CD Acts creation, disguising hegemonic attitudes behind medical evidence, and thus implementation of legislative measures to further define sexual attitudes towards women.

In the CD Act patriarchal forces translated their ideologies into legal measures to maintain control and uphold a double standard that safeguarded healthy male promiscuousness and enforced supremacy at the expense of female repression as both wives and prostitutes. Therefore sexual standards in law and society support each other in a perpetually cyclic fashion. ‘Legal victimization is piled on top of social victimization, women are dug deeper and deeper into civil inferiority, their subordination and isolation legally ratified and legitimated’.[64]

Additionally, ‘both the opponents and the proponents of the Acts are members of the same linguistic community and share the ‘monopoly of legitimate symbolic violence’[65] In other words outspoken arguementalists were trying to exert their beliefs unto an mostly voiceless lower-class, female populous. The prostitute was deemed an object upon which to enforce an identity, rather than allowing her to practise autonomous decision. The prostitute’s ideological separation from respectable females and intrinsic connection to disease, that grew in the first half of the 19th Century, was solidified and perpetuated by medical knowledge: factual proof to a long standing subjective ideology.

Many moralistic arguments were fuelled largely by emotion and subjective individual opinion, therefore sound reasoning was clouded, yet contemporary doctor Miller aimed to provide ‘sounder views’[66] to the pressing matter of the CD Acts. Miller upheld that health undisputedly necessitated the Acts enforcement. Writing ‘[t]he only shadow of an excuse for this public patronage of, if not identification with, immorality is that thus the ravages of syphilis may be restrained’.[67]

Even in the face of the growing repeal campaigns the vast majority of medics still favoured the sanitary benefits for which the Act had been introduced. ‘In 1872 the National Association delivered a petition to the Home Secretary, Henry Austin Bruce, signed by 50 physicians and surgeons opposed to the CD Acts; medical men in favour of regulation responded with their own petition signed by 1,000 doctors’.[68] The CD Acts allowed, supported by medical avocation, power over women. The Ladies National Association protested the Acts were unlawful as they ‘put their reputation, their freedom, and their persons absolutely in the power of the police’, arguing further ‘liability to arrest, forced medical treatment, and (where this is resisted) imprisonment with hard labour, to which these acts subject women, are the punishment of the most degrading kind’.[69]

Again the fundamental roots of all debates over the Acts were the powers afforded to police and doctors[70] to forcibly examine women on the grounds of medical necessity to investigate their health.

transforming moral law into legislation and medical practise to enforce sexual convention[71] – read

Furthermore, standing opinion of medical men was not to be disregarded as their knowledge was highly considered in a time when urban growth was so rapid that health measures, understanding and introduced sanitation was paramount. Due to population increase and urbanisation cities became a prime place for prostitution fuelled by demand and economic situation but also incidentally a prime place for increased disease.

In 1856 the British Medical Association was founded, complimented thereupon by the General Medical Council’s founding in 1858. Additionally ‘the number of doctors rose considerably, from 14,415 in 1861 to 35,650 in 1900’.[72] Furthermore, committees to enquire into venereal disease often held doctors as their largest occupational group since the focus to determine the prevalence and find solutions to venereal disease was considered within their field of expertise. By combining opinionated language with medical fact rising numbers of medical institutions heightened their influence towards legal and social practice.

Solution. Conclusion

Medicine centred the prostitute as the cause of venereal disease; a prevalent danger that needed reducing through controls over her body, whilst simultaneously bestowing males with beliefs of a biological necessity to satisfy their sex drives. Demand for sexual health alongside demand for sex on the one hand, and a morally standing domestic wife on the other, were centred in beliefs of medical necessity, with regulationary measures building upon the male demand for power and control over the female body. Regulation was further justified as medics used biology to deem prostitution a “necessary evil” beyond eradication. The medically advocated new legislative procedures of arrest, forced examination and involuntary internship into lock hospitals fulfilled patriarchies surface justifiable aim to reduce disease, however procedures also supported the further removal women’s autonomy to support male hegemony. Additionally medical arguments, due to their factual formulation, overruled contending moral and religious argument which were more open to subjective and speculative opinion. The influence of authoritative doctors and effectiveness of reducing disease ensured the Acts were hard to criticise at a scientific level. Physiological law justified legislative measures. Leading on, the double standard was also justified by medicine and safeguarded by law. Patriarchal forces translated their ideologies into legal measure to ensure hegemonic control and uphold a double standard that safeguarded healthy male sexual exercise at the expense of female repression and objectification both as wives and prostitutes. Medicine was instrumental in influencing, justifying and solidifying the legal decisions, as well as social structures, desired by patriarchy.

Chapter Three: Patriarchy and Male Hegemony

This final chapter aims to investigate more closely the patriarchal and hegemonic structures influenced by medical and further implemented by the CD Act. Firstly considering how the Act affected free women citizens; leading on to examine the relationship between patriarchy, hegemonic male ideologies and medical knowledge. Two focus points are how medical examinations and exclusive female arrest enforced power structures. Furthermore evaluating the permeation of medical understandings into societies ideologies, gender and class relations. Accumulating to an extensive analysis questioning whether the CD Acts were a product of failures in medical understanding or conscious oppression.

6. How did the Act affect free women citizens?

State interest is demonstrated by the Act to primarily concern high levels of venereal disease among armed forces.[73] But venereal health concerns were also prevalent throughout society. Further reasoning for the Acts introduction was male benefit both sexually and hegemonically. The Act afforded legal and ideological superiority over all women. Whether as a bride or prostitute, via dowry or other monetary exchange, women were bought.

Women were objectified objects of ownership to their fathers or husbands. Where some women enjoyed the autonomy prostitution offered the law assured she was controlled by legalisation, the police, medical institutions, and the demand created by males. The New Swell’s Night Guide’s were guidebooks addressing men’s leisure desires by listing establishments prostitutes inhabited. Revealing the candid regards for women as existing for the pleasure of men, as objects to be used and discarded. Mme Matileu’s Soho and Kensington establishments uses metaphors for women as meat. Writing: ‘meat dressed to your own liking…when any of them are fried, they are turned out’.[74]

The metaphors maintained some disguise to a males outgoings, and indicates some need for prudery, but the comparisons of women to meat is aligning with contemporary consideration of a females role to serve men whether in the home or for sexual needs outside marriage.[75] Above all the guide’s respond to the rising fear of venereal disease and demand for prostitute’s to be without medical consequence to male customers, exampled in further text reading: ‘nothing is allowed to get stale…her flock is in prime condition’.[76]

The widespread male belief was that by regulation prostitutes, and enforcing health measures, the problems of syphilis, gonorrhoea, and further venereal diseases, would be solved whilst allowing the institution of prostitution to continue existing to gratify male desire. Additionally, ‘some supporters saw the Acts as protecting the chastity of middle-class females, who would otherwise be venerable to sexual predation from gentleman who could find no other release. This belief permeated public felling to such an extent that women, too, were supportive of the Acts, despite its obvious gendered discrimination[77].

The Act specified merely to arrest only upon ‘suspicion’ meaning all women were subject to patriarchy’s controls. The Act was a response to rising venereal disease in enlisted men however free women citizens were targeted as the root of disease. The Act stated ‘prostitutes’ however, due to discrepancies in what defined a prostitute, the female population as a whole was subjected to demeaning examinations and soliciting by men perpetually viewing them as sexual objects. Thus free male citizens benefited from reduced disease among prostitutes.

The following expansions of the 1864 CD Act in 1866 and 1869, to enforce the regulation of prostitutes across a greater area and intern prostitutes for a longer period until healthy, was partially a response to society wide male demand for ensured access to healthy women. After being identified as potential prostitutes women were thus additionally required to undergo demeaning and intrusive inspection. To undergo inspection the Act specified a woman only need be ‘suspected’ of being a prostitute according to male police inspectors, no evidence was required, thus views were heavily subjective. ‘Dr William Lawrence said point-plank that visual inspection of women could not be relied on’.[78]

This contemporary view, combined with scholar Lori’s conclusion ‘[t]he definition of common prostitute was vague, and consequently the metropolitan police employed under the acts had broad discretionary powers’,[79] meant free women were often misidentified as prostitutes. If a woman did not submit voluntarily to the medical and police registration system she would be brought before local magistrates.

During trial it was the woman’s responsibility to prove her virtue and that she did not accompany men for money or otherwise.[80] A women was guilty until proven innocent, rather than innocent until proven guilty. (See print screenshots to highlight) Thus even innocent women would be against the odds to prove their innocence.

Patriarchy was in favour of male hegemony. Making verdict favouring a women’s’ innocence would undermine their hegemony and the very Act they introduced. All process: from arrest, to examination and incarceration medicine and the law were involved. What is more medicine and the law cooperated together to control women. Women who were not prostitutes were also under control: as they modelled their appearance, personality and daily lives in fear of being suspected to be a prostitute.

7. How did contemporary medical knowledge influence and reflect hegemonic male ideologies and the need for repression?

Victorian medical, and in particular gynaecological, knowledge was questionable, lacking in comparison to todays knowledge, which led to ideological manipulation by hegemonic forces. For example ‘a women herself free from disease may be the vehicle of disease from a previous tainted intercourse’.[81] Even undisputable differences regarding female anatomy were utilised to further repress and control females. For example females experiencing menstruation were interned in hospital until inspection could be carried out. Furthermore the natural process of the menstrual cycle, necessary to ovulation and ergo the females sanctioned role of motherhood, was riddled with ideologies enticing fear of females and further aligning her as the central source of the nations disease, dirt and corruption.

‘Mr Berkley Hill said before the Royal Commission:- “Menstruation is contagious…The menstrual fluid is a common cause of gonorrhoea”.’[82] Just as menstruation was, venereal disease was also considered a result of sin, bodily imbalance and excess. Physical ills supposedly reflected morbid spiritual states. Resultantly medical reasoning was intertwined with moral attitudes to perpetuate the view diseased woman were a ‘Great Social Evil’.

Furthermore, another reason for the Acts exclusive blame of women, and attitude that prostitutes were unnatural in their sexual promiscuousness so thus deserved of repression, was biological arguments aligning with Acton’s contemporary view that: ‘the majority of women (happily for them) are not very much troubled by sexual feelings of any kind…and, were it not for the desire of maternity, would far rather be relived from his attentions’.[83]The belief that women felt no sexual pleasure spread widely through Victorian society and is one of the most considered quotes of Victorian sexuality today.

It’s important when accessing Acton’s views to remember that his beliefs were not representative of the entire population but they were widely agreed with, and highly influential especially from a medical perspective. Medical understandings were key to legal institutions who utilized perceived differences in gender sexual needs to warrant examination as unacceptable upon males, but acceptable upon females as according to biology they comparatively held lesser sexual feelings. Victorian’s believed women do not feel sexual enjoyment; rather they should only engage in sex for the purpose and interest of reproduction.[84] P.74 helen mathers

Contrastingly, surgeons such as Acton and Deakin’s work highlights the prominent understanding among medical professionals that males are sexually animalistic, that they are incapable of controlling sexual desires and thus females must be controlled to ensure they are safe for male exercise. Deakin highlights that biological factors support the necessary and inevitable continuation of prostitution; announcing prostitution will ‘exist so long as the animal part of his nature preponderates in man…prostitution is a ‘great and a permanent fact’. It was considered rule that vast differences operated between genders sexual instincts and passions. The contemporary poet Byron lyrically encompassed society’s commonplace belief:

In her first passion, woman lover her lover.

In all the others, all she loves is love.[85]

Echoed by Coleridge who wrote ‘[t]he man’s desire is for the woman, but the woman’s desire is rarely other than for the desire of the man’.[86] Thus exemplifying these views penetrated society into prominently believing that a women’s existence was considered to solely be to gratify man. In many instances such as this science was complimentary evidence to religious and social beliefs.

Before reaching financial suitability for marriage men ‘during this time of probation, [he] is exposed to all the temptation of desire, perhaps unmet by mental, moral, or religious control’[87] he is reasoned biologically incapable of resisting when faced with ‘favourable opportunity’.[88] Victorian’s attitudes were moulded to consider ‘men is led captive to impure embrace of harlot’[89], so framing the prostitute as ‘The Great Social Evil’. That she behaved against nature, rather than her soliciting male counterpart subject to uncontrollable biological needs, was the root of medical and moral upheaval. By definition of societal and medical opinion the prostitute was considered to be behaving unnaturally, regardless of economic situation, market forces or personal circumstance which forced many women to turn to prostitution against their will. Hegemony dictated it was an unnatural desire that turned women to prostitution.

It is important to know that vast academic reconsideration of the views presented by Acton in Functions and Disorders, backed by Marcus’s The Other Victorians (1964), have identified ‘Acton’s problematic status as a source of information’.[90] Using contextual material and subsequent commentators parts of Acton’s opinion is considered atypical; notably, Acton considered prostitution a transitionary phase, with no lasting health consequences once a woman is reintegrated into respectable society by means of marriage and domesticity. Yet statistics prove prostitutes did not naturally regain their health.

Prior to 1864 an unregulated voluntary system operated ineffectively. Penitentiaries, asylums and lock hospitals were expensively inefficient and inadequate to cope with disease, this demonstrates most women were left to their own devices. (‘Quote statistics empty beds/male favour’). Meaning women were not regaining health and respectability without intervention by forceful regulatory measures. Thus the CD Acts were influenced by majority medical opinion and statistics primary a un-regulated system was ineffective at controlling disease.

What is more, Acton controversially considered a woman’s transitionary engagement in prostitution to be due to severe economic circumstance rather than choice to engage in an industry of sexual exchange. Ryan examples, on a scale of extremes, the comparative view to Acton. He believes that women do seek to fulfil sexual desires, furthermore the consequences of engaging in prostitution, including social stigma and pregnancy or infertility, are rightly deserved as punishment for sexual and social deviance.[91]

Prostitutes were widely considered socially deviant vermin and thus should be treated as vermin. The majority of Victorian opinion fell between these extremes, yet nonetheless views were unified threefold by attitudes considering: male sexual exercise necessary; females to hold higher sexual restraint; and most importantly females to be the exclusive cause of medical and moral upheaval, and thus worthy of repression and punishment.

The majority of society believed charitable help encouraged prostitution by reducing the severity of consequences such as medical infliction and suffering. By 1864 charitable attitudes popularised by evangelism had lost favour, attitudes changed to consider prostitution an ‘immoral, sinful practice’[92] unworthy of charity.

Acton’s sympathies for woman entering prostitution due to economic desperation were also controversial and ‘atypical’.[93] Society considered Acton ‘humanized’ the prostitute. Legislative Acts evidence favouring for the hegemonic views shared and presented by forces such as government, generals, officers and doctors in the 1860’s. These views shared arguments in accordance with upper and middle-class ideologies for pressing upon society their attitudes towards women: as disgraceful objects and an objectifiable ‘alien ‘other’’[94] necessitating male intervention via repression.

8. How did medical examinations enforce patriarchy and male hegemony?

Medical institutions treated women dispreferentially in comparison to men. Thus ‘lock hospitals imposed a social discipline and therapeutic regime on female venereal patients that incorporated the class and sex prejudices of the dominant Victorian culture’[95] both prior and post the 1864 CD Acts reform of the voluntary system. Through the hospitals structure and invasive examinations male doctors exercised direct control over women, indirectly male hegemonic values were enforced upon women. Examinations were forceful and often painful. Judith Butler led a campaign against the CD Acts after she gathered vast testimony to the horrors women underwent at the hands of doctors. Testimony was countless to the dreadful pain and bloodied garments both due to the size of the instruments but also the force with which the instruments were used. Examination was widely known and recounted as ‘steel-rape’ or ‘medical-rape’:

It is awful work; the attitude they push us into first is so disgusting and so painful, and then these monstrous instruments – often they use several. They seem to tear the passage open with their hands and examine us and then they thrust in instruments and they pull them out and push them in and they turn and twist them about and if you cry out they stifle you.[96]

Ob Exam

The deep-seated hostilities to women were evident in diagnostic and therapeutic procedures advocated by medical institutions.

9. Why were males not medically examined, repressed or punished by the CD Acts?

Class and gender domination was insinuated within medical theory and practise. As a further example of prejudice: members of the government, armed and medical institutions considered male examination to be derogatory and demoralising to troops.

Florence Nightingale recognised ‘the disease of vice is daily increasing in the Army’,[98] yet her advice to introduce day rooms, clubs and institutes to improve physical health and moral were ignored for favour of pressure by regulationists for the inspection of females.[99] Periodical inspection of army men had been abolished in 1859. The resulting exclusivity of female examination reflects the male hegemonic structures of society, as does the Act’s female gendering of prostitutes.[100]

The 1857 report from the Royal Commission on the Health of the Army called for an end to periodic genital examination of soldiers[101] because it was deemed to be ‘decreasing soldier morale’.[102] Yet prostitutes were extremely popular with military men because marriage and homosexuality were banned among the armed forces. This created a prime customer for prostitutes. Statistics reflects many prostitutes operated on a locational and seasonal basis to the trends of demand stipulated by the transient male population of sailors.(Footnote statistics)

The prostitution market was a dynamic of supply and demand. Therefore the law both fuelled demand for prostitution and regulated it to ensure sexual demand was exercised without consequence to the health of customers and proprietors, whereby the most prominent concern stipulated in the CD Act was to protect the health of the nations army and strength; physically and psychologically. The significance of legal regulation signifies aversion to abolition of prostitution as well as objectification and disregard for the suffering of prostitutes whilst simultaneously heavily regarding the health of customers.

Alongside decreasing moral examination was considered detrimental to male ‘self-respect, and was medically inefficacious’,[103] but the same considerations did not apply to females. An prominent point of the Victorian women’s movement was ‘[o]pposition to these measures, which…involved what was often described as ‘medical rape’ with the instruments of inspection’[104] that ‘disrupt[ed] a woman’s purity’.[105]

Although contemporary doctor Pearson controversially favoured inspection of women and clients alike he also controversially rendered physical or physiological discomfort frivolous. ‘Pearson would argue that public health concerns clearly outweighed such reservations’ [106] of discomfort. Thus, helpfully for patriarchy, it was most widely believed by medics that women did not possess such self-respect or had no more respect to loose after partaking in prostitution. The possibility a women was innocent was irrelevant to those who supported the Acts measures.

Resultantly examination supposedly had no damaging effects on female mentality. Deakin is one of many influential contemporary medical practitioners who shared this overwhelmingly derogatory and patriarchal towards women. Personal opinion representative of the majority of male patriarchal ideology is evidenced within medical practitioners language and accusations of blame. Language such as ‘daughters of shame’,[107] and ‘…’. Even under moral questioning reading before the Medical Society of University College in 1871 Deakin justified legislative methods as necessary to ‘look after the health of the guilty in order to preserve the innocent’.[108]

Biologically males were freed from any blame derived from sexual behaviours outside wedlock. As discussed this was mainly due to contemporary considerations that males, contrastingly to females, were unable to control sexual desires, especially if seduced by a female and thus she was to blame for immorality and corruption. Resultantly the promiscuous female, most often resultantly defined as a prostitute, based solely on her behaviour must be controlled and sanctioned by lawful enforcement as signified by the CD Acts.

10. How did medical understandings permeate societal beliefs?

The spread of disease fuelled a moral epidemic because disease weakened the armed forces and disrupted the sanctity of the family, which in turn dramatically upset the gender roles and family structures upon which Victorian life was orientated around. Prostitution is portrayed as a pollutant among respectable society; ‘wrecking marriages, breaking-up the family home and destroying the very fabric of the nation’[109] Additionally, not only did involvement with prostitutes upset the structure of family units but the prostitutes ill health was considered a pollutant to the purity of children. Thus medical facts were integrated into societal beliefs that perpetuated the fear of prostitutes.

loathsome disease affecting pure future generations (deakin) regulationist properganda: syphilis hereditary so affect innocent generations

Health formed a fundamental part of the legal movement for the CD Acts by engaging concern at a public level, thus forming support for repression.[110] Society was conditioned to beliefs grounded by medical arguments presenting evidence supporting controlling methods as undeniable fact. Men ‘jumping as it does with their natural desires…readily believe it’. Sexual necessity was evidentially supported by medicine, the law freed men from legal sanction, and consequentially social sanction was reduced. Thus ‘[w]ives, temporarily laid aside from marital reciprocity…have in consequence become parties to a vicarious supply’.[111]

Parents overlook their sons’ unchastity. A son’s suitably to marriage is based on his finances, whilst dually society calculates a daughter’s value most prominently in direct correlation to her chastity. Joyce concludes, ‘so concubinage, seduction, and prostitution, necessarily thrive’.[112] Society is conditioned into considering male sexual exercise outside marriage as not only acceptable but necessary as per medical evidence, thus creating a demand ratifying a double standard.

Marriage customs in society, not least conditioned by legal sanction of illegitimacy, existed according to upper and middle-class ideologies. Scholar Hughes emphasises that because a man must prove his financial ability to support a family prior to marriage this leads to a double standard of acceptability for males to use prostitutes until their finances were sufficient.[113] Thus prostitutes became a viable and sole option for lower classes boasting poor finances but who needed to engage in sexual gratification on ‘medical requirement’ to their health.

Further reinforcing this double standard, dually chastity is necessary to a woman’s pure status, value and suitability as a wife and mother, whilst economic desperation among lower classes combined with demand for prostitutes necessitates some woman operate sexual promiscuity that affords both male gratitude and sanction. It was widely considered a male prerogative to access women.

11. Were the CD Acts due to failures of medical understanding or conscious oppression?

The answer to this question is firstly important to consider the operation of the double standard in Victorian Society. During the Victorian period there were no tests to assure a child’s legitimacy. Thus disease was considered evidence of infidelity. Chastity was paramount to the value, purity, respectability and moral upstanding of a woman. But more than that societies structure depended on the upholding of women’s chastity. To lose her virginity before marriage was to ‘fall’; to become a ‘fallen woman’. A woman’s value in her sexual purity, maintaining one sexual partner, connected to patriarchal ideologies of ownership over women. The only way to prove her matrimonial loyalty and purity was to remain free of venereal disease.

However should she contract disease from her husband, where he had engaged in sexual relations unfaithfully, it would be she who was accused of unfaithfulness and resultantly outcast because it was considered biologically and socially unfounded that males were to blame for disease.

Many innocent women were accused of prostitution because it was not considered, or at least hidden, that males could pass disease to their wives. The scholar Lewis raises the question were the Contagious Diseases Act introduced due to failures of medical understanding or conscious oppression?[114] Writing in the 1970’s repeal campaigner Wilkinson highlighted the ‘medical lust of dominating and handling of women’.[115] Affirmably Walkowitz focused from a less personally invested academic perspective, observing the ‘medical profession as a conscious instrument of male dominance’,[116] concluding… The levels to which exclusive female blame was due to contemporary understanding, or intentionally constructed by ideological manipulation in support of framing hegemonic attitudes, is unclear. However in such cases as gonorrhoea, which was ‘harder to determine in females’ due to their anatomy,(walkowitz?) doctors followed societies patriarchal gender-structures by helping males to hide their symptoms.

In cases of hiding disease, medical understandings are evidence that patriarchal society did not always adhere to medical influence, instead ignoring evidence so as to maintain their own repressive, objectifying attitudes toward women. Yet Victorian’s were unaware gonorrhoea was serious, meant intercourse continued whilst doctors readily helped males to mask their symptoms (walkowitz?). Perhaps if the seriousness of gonorrhoea was understood such support to continued male promiscuousness would not have taken place.

This is unlikely however as although syphilis was considered to have the stages of infection in males and females[117], females were provided less treatment, alongside being arrested rather than treated as a victim of vice like their male counterparts. Furthermore ‘non-syphilitic woman were often thrown into the lock hospitals along with their diseased colleagues.

Their gender, rather than disease, being the target for internship. We also know that doctors of the time had no real method for diagnosing the disease’.[118] In hindsight the Victorian’s had a limited knowledge, ability and availability in lock hospitals to cure venereal disease. By manipulating medical evidence to their favour males framed attitudes towards prostitutes as negative, the exclusive blame for disease, thus supporting sanction. ‘Ryan’s Prostitution in London contained a series of anatomic etchings, but none concerned female ailments; the entire work was male-orientated on this subject’.[119] The lacking understanding of females, in comparison to males, opened medical understanding to ideological manipulation, as well as revealing Victorian attitudes considered females less worthy of scientific investigation.

Patriarchal society held a heightened desire to maintain the double standard; achieved by enforcing female chastity and punishing those women who transgressed their moral ideals. Medical statistics; rational; knowledge; and treatment of venereal disease, are all analysed with concern to dominant social and sexual ideologies. The respectable woman was one submissively remained in the private sphere; adhering to domestic, household and family duties.

Prostitutes were contrastingly independent and active in the public sphere. Scholar Hughes considers the ideology of Victorian men and women belonging to ‘[s]eparate spheres’ as defined by gendered ‘natural’ characteristics. Hughes ideology of ‘separate spheres’ is akin to ideologies of the double standard in sexuality, marriage, rights, labour and education. At the centre of Hughes argument lies the biologically founded Victorian consideration that ‘[w]omen were considered physically weaker yet morally superior to men’.[120] This was an ideology that Victorian’s shared, using it to inform their reasoning and justification that females belonged in the domestic sphere, to ‘counterbalance the moral taint of the public sphere’[121] and ‘preparing the next generation to carry on this way of life’[122]to which they were considered biologically suited in physicality and genetic characteristics.

Also, to enforce the separation of genders through occupation males used biological reasoning.[123] Biological understandings considered females physically weaker than males, embodying greater ‘sensitivity, self-sacrifice, innate purity’[124] and delicacy, suiting her to the domestic sphere and deeming the public sphere too dangerous to her ‘innocence and refinement’.[125] In fact ‘[p]hysicians thought that the stresses associated with modern life caused civilized women to be more susceptible to nervous disorders, and to develop faulty reproductive tracts’.[126] Thus restraining her to the domestic sphere was for her own good.

This reveals the focus of societies structures and values upon a females reproductive role. Furthermore this supposed fact supported ideas the prostitute was not of sane mind. ‘[T]he ‘ideal of womanhood’, [was] an ideal which saw their role as centred in the home and which believed them to be creatures too pure and delicate for the rough commerce of the outside world’.[127]

The Victorian era is famed for its ‘social inequality at home’.[128] An inequality that was not only upheld in theory, but also justified by medical understanding and enforced through legal measures such as those demonstrated in the CD Act. It was further believed that women’s purity must be protected from the evils of the public sphere; the CD Acts were a legal exaggeration upon the controls and restrictions males exerted upon females.

Hughes refers to sources exampling the medical arguments, such as women engaging in academic pursuits caused infertility, and literature pertaining to female instruction on what characteristics and performity were expected from females, including elegance, femininity and chasteness prior to marriage.[129] The Victorian ideologies of ‘pure’ and ‘impure’, or ‘fallen’, women originates from this consideration of the female role, whereby purity is a term encompassing purity of the mind and body. Juxtaposing the ‘pure’ woman: the fallen woman was deemed ‘ill’ or ‘unnatural’ in her mental outlook, for transgressing societies standards; and body, for she was synonymous with disease even if she had not already contracted venereal infection. ‘created in direct opposition….the prostitute’s body representing the overly sexualised female body, and the ‘moral’ woman representing the desexualised, maternal body’.[130] The image of two kinds of Victorian women was given pseudoscientific credibility by contemporary medical publications.

Yet prostitution was thus perpetuated because male demand meant prostitution was often the only, if not more attractive, alternative to workhouses for outcast, single and likely disowned women to sustain a living. Throughout Wallis’s paper the expected gender roles are explored and used to support a radical feminist reading.

From female chastity, obedience and domesticity, to male breadwinning alongside an acceptability to enjoy the freedoms of ‘leisureable pursuits’.[131] From the evidence of ‘separate spheres’ and Victorian gender roles in Wallis’s case study it is clear to understand how gender roles translated into a double standard. Women were expected to ‘offer their sexual exclusivity in exchange for male support and commitment’.[132] ‘From an evolutionary psychological perspective, the double standard is a rule of nature’.[133] However ‘[f]rom a social constructionist point of view…men use it to obtain loyalty from women (and punish any lack of loyalty)’.[134] Whereby even if females do not experience sexual pleasure, biological understandings to female’s occupational roles have come a long way in support of female liberation since the 1860’s.

The dividing of women into ‘pure’ and ‘impure’, ‘angel’ and ‘fallen’, ‘faithfully submissive’ and ‘deviant’, is evidence of the patriarchy enforcing strict ideological frameworks, yet simultaneously creating a ‘double standard’. Hegemonic Victorian’s not only enforced ideologies of separate spheres between genders but also created the prostitute as a separate ‘alien’ ‘other’ to respectable females, id est. ‘marriage-worthy’.

Prostitutes were seen as subaltern and separate from other women.[135] This was rooted deeply in disease as the fundamental difference and indicator between chasteness symbolic with respectability and unchasteness symbolic with promiscuous, deviance and disrespect.

In Victorian times there existed ‘two extreme romanticised images of women. The prostitute posed a stark contrast to the upper and middle-class ideal of the woman as a mother, an obedient wife and above all financially and socially dependant on her husband’.[136] It is notable that these differentialities also supported hegemonic interests to maintain class divisions, by placing unrealistic expectations upon lower-class males to be financially able to support an entire family. Lower-class females would often have to turn to unskilled work, where prostitution offered temptation due to better pay and work hours than workhouses.

As mentioned previously prostitutes might operate on a seasonal basis to the movements of sailors and demand to supplement a family’s income. The creation of the ‘fallen-woman’ as a separate class was societies answer to the crisis of morality created by demands of the sexual double standard. Accordingly allowing for a scapegoat to the moral upheavals of society, maintenance of the respectability of upper classes and pure women, and continuation of a market to exercise male sexual desires. The maintenance of control over pure women’s societal position was ensured through the Acts, as well to ensure the chaste women’s sexual servitude to her husband and value to her as an exchange for marital finances and relations.

Patriarchy and Male Hegemony, Conclusion

Adhering to medical arguments the Acts were implement to gratify society’s desire both for un-diseased prostitutes, as forms of sexual release, and wives as loyal childbearing homemakers. The morality of the nation was protected according to male and female bourgeoisie values practicing male promiscuousness alongside protection of bourgeoisie woman as “respectable” citizens.

Prostitutes, most often working-class women, were created as a separate group to respectable females in order to protect the sanctity of the family, social structures, and morality alongside the nations health threefold: sexually, physiologically and psychologically. However the operation of the double standard: including the brutality of exclusively female examination and possibility of a monogamous, respectable women being castaway at the suspect of being a prostitute, or discovery of venereal disease contracted due to her husbands fornicate actions, centred the Acts in debates of gendered repression, morality and broad discretionary use of patriarchal power. Prostitutes were considered void of self-respect, as well as undeserving of sympathy, due to their immoral, wanton behaviour.

Medical knowledge solidified the prostitute as central source of the nations disease, dirt and corruption. As well as solidifying patriarchal and hegemonic structures separating society into six broad groups, given in order of respectability and afforded value: males belonging to patriarchal institutions; bourgeoisie males; working-class males; “pure” females; criminals; prostitutes. Also, biological evidence related to social convention that women’s natural desire was to fulfil her familial duties, and were morally superior to males.

This justified their confinement to the private sphere where their morals would be protected and they were able to fulfil their biological duty unquestioningly supporting her husband and children. Medicine and social ideology contracted the ideal female largely on a complete opposite to the prostitute, as a further method of ensuring the control of women, alongside medical necessity supporting the continuation of the double standard. A women’s existence was deemed to gratify man, medical understanding overruled moral and religious arguments opposing the Acts for implementations interpreted as repressive, demeaning or gendered. However other instances adhering to legislative and bourgeoisie desires married medical understanding with religion and social beliefs to strengthen the Acts support.

The Acts implemented the biologically necessitation of methods to ensure the physical and psychological health of males, respectable females, and the nation. Consequently the medically adjudicated legislative measures protected social structures, in consonance with valuing females based on their sexual status, through an extended fear and repression of prostitutes.

Conclusively medical understanding was influenced and investigations hindered by desires to retain patriarchal and hegemonic power, medical understanding perpetuated societies sexist ideologies. Thus repression was not a complete failure of medical understanding but rather existed in a perpetually cyclic relationship with patriarchal and hegemonic ideologies that hindered investigation into, or published reports on, the true understanding’s of human biology. Medics were unwilling to investigate or deviate from practises that supported the maintenance of bourgeoisie values, power and control over females.

To what extent does the study of medical sources shed a new light on legal and social attitudes to prostitution in 19th Century Britain?

Final conclusion

The Contagious Diseases Act 1864 evidences the government’s solution to rising societal concern for and spread of venereal disease whereby the state favoured regulation. Medical investigation was predisposed to favour male superiority, and objectify any female suspected of or interned with disease through a variety of influences including: historic medical understanding; values; social structures; and religious arguments for male supremacy. However, without medical evidence, arguments and pressure on government to introduce repressive and sanitary protection legislative measures, it is unlikely government would of acted accordingly in light of legislative alternatives, or even been aware of the true extent of venereal disease reasoning the reality of the danger it posed to the nation.

Medicine identified females as the sole cause of disease and so intrinsically connected prostitutes to disease that prostitutes were personified as venereal disease itself. The CD Act medicalised sexuality and prostitution, providing evidence that stimulated attitudes supporting legal intervention and gendered repression.

Legislation seeks to identify, and respond to, the root cause of harm. Medicine facilitated the identification of the prostitute, and the potential of women to become diseased through illegitimate intercourse whilst citing husbands as impossible to contract and pass disease to their wives, as the root cause of venereal disease.