Accuracy and Timeliness of Corporate Ratings Before and after the Financial Crisis of 2007-2008

Info: 9862 words (39 pages) Dissertation

Published: 15th Feb 2022

Abstract

The history of credit industry in United States dates back to 1900s when it gradually became a part of global financial system. Credit rating agencies (CRA) also then popularly called the gatekeepers of the financial markets strived for the efficient functioning of the financial markets by reducing the asymmetry of information available between who wanted to invest and people who had money to give it out to credible and trustworthy people (Adelson, 2012). Credit rating industry had essentially been unregulated for over a century. However, the bankruptcies of corporates such as Enron and Worldcom, financial crises such as 1997 Asian crisis and finally with the advent of global financial crisis in the 2000s, the financial industry was concerned regarding the credibility, accuracy and reliability of timeliness of these ratings. The accuracy and reliability of the credit ratings was questioned and investigated by the users and authorities. Thus, they felt the need for some regulations to be implemented and congress authorized limited regulation in 2006 and the Securities and Exchange Commission issued formal regulations by 2010.

The objective of this paper is to develop an understanding of the role and credibility of CRA in the global investment and financial markets. The scope of the research will focus largely on information concerning the credit rating agencies, their role and their credibility. Drawing from the empirical evidence collected during the research process and critical study of the literature already available on the subject matter, this research paper aims to uncover rationales and theories behind credit ratings, how they operate and form their conclusion on the creditworthiness of the issuers, changes made in relation to methodology of credibility and timeliness of CRAs, stricter regulation implemented and other significant changes related to CRAs and their impact post the financial crisis. The research will focus on evaluating if regulations implemented on the credit rating agencies post the financial crisis will succeed in increasing accuracy, credibility and timeliness of the credit rating agencies.

The expected result of this event study was a larger positive coefficient compared to the reaction of yields to downgrades before the credit crisis. This expectation is caused by the magnitude of downgrades since the financial crisis and fall of financial market. Morris (2001) provides in his paper a strong support for the reputation hypothesis which indicates that after implementation of regulation the CRAs are more concerned and protective of their reputation and hence issue downgrades that are less informative, lower ratings and false warnings. The results of that paper also indicates that when regulation were implemented in the post financial crisis, on average bond ratings were lower. Thus, using a comprehensive sample of corporate bond credit ratings from 2005 to 2015, we also intend to find results that show us the correlation between regulation changes and timeliness and accuracy of the credit rating. However, the results of this empirical research conducted provides little evidence that the regulation disciplines credit rating agencies to provide more accurate and informative ratings. Thus, the research would conclude that there is no significant statistical evidence to support the argument that the regulation changes would improve the timeliness and accuracy of the rating. In fact, increasing the legal and regulatory costs to CRAs could actually have an adverse effect on the quality of credit ratings but we might have to perform additional research to confirm that fact.

Introduction

Credit rating agencies (CRA) are known to give ratings to different issuers and securities using several methodology to evaluate the creditworthiness and judge these issuers’ capability to fulfil financial commitments (de Servigny & Renault, 2004). In other words, credit rating agencies assign ratings to different issuers and securities which in the financial market serves as indication about their credit quality. In 1909, John Moody pioneered the credit rating business when he published about creditworthiness of bond ratings of railroad companies and made it available to public for the first time. A bond rating provides insightful information to the investors about the debtors’ capability to pay back the debt and about the debtors’ probability of default.

Credit rating agency play a pivotal role in the financial system as the existence of credit rating agencies reduces information asymmetry existing between borrowers and lenders as this information asymmetry leads to inefficient investment decisions. The reduction of information asymmetry enables the investors to make more assertive and informed investment decisions. So, credit rating agencies is an important part of financial market that attempts to make the market more efficient and effective in functioning. However, with time, there have been several institutions that has appeared in the financial market that issue number of ratings but the market still remains undisciplined and unregulated.

This existence of mushrooming CRAs on the financial market leads to several concern regarding the credibility of credit rating agencies, the accuracy and timeliness of the information that is released to the financial market and the regulating that monitors the governance of these credit rating agencies. Although, the idea is that credit ratings should be considered as opinion and not endorsements or recommendations for financial instruments, as credit rating agencies evolved and gained power, several investors take their investment decisions based on the ratings as they fail to make their own informed financial decisions.

Due to this lack of knowledge in finance and of carefulness, people had to face huge losses in 2007 and 2008 during the financial crisis as there were mass defaults of highly rate structured finance products. This raised concerns over the credibility of credit rating agencies and quality of rating issued by these CRAs. Thus, credit rating agencies were a relevant target of scrutiny for it after that. The financial crisis exposed and publicized numerous flaws in agency ratings and the entire rating industry, leading to lots of criticism of the credit-worthiness assessments of then leading CRAs like Standard & Poor’s (S&P), Moody’s, and Fitch. The credit rating were mostly criticized for lack of transparency related to the rating methodology, poor timeliness of ratings, insufficient regulation, and incentive conflicts associated with the leading rating agencies. The lack of timeliness of credit rating was one of the most criticized aspect of credit rating agencies in the aftermath of Enron, financial crisis and other high-profile bankruptcy cases. It is argued that failing to issue timely downgrades and accurate rating has become more costly to the rating agencies after financial crisis and thus, we expect rating agencies to take measures to improve rating timeliness and thus consequently stability and accuracy. Thus, several regulations were implemented to regulate and monitor the credit rating agencies.

Post the financial crisis, there were important regulations that were passed that had significant impacts. Dodd-Frank Act was implemented which would increase the liability of credit rating agencies’ liability in case of inaccurate ratings insurance since the pleading standards for private actions under Rule 10b-5 of the SEC Act of 1934 for credit rating agencies was reduced. Also, the regulation passed made it possible for the SEC to easily levy prohibitions on credit rating agencies and bring claims against credit rating agencies for material misstatements and fraud.

On one hand, the increase in legal and regulatory scrutiny for issuing inaccurate ratings may encourage CRAs be careful, efficient and effective to improve their rating methodology and incorporate better monitoring system. These changes could lead to more accurate and timely credit ratings. Credit ratings may improve further as CRAs strengthen internal control and corporate governance mechanisms, although this effect is likely to be muted given the uncertainty regarding the SEC’s final rules. On the other hand, the increase in legal and regulatory scrutiny can have an adverse effect on the quality of credit ratings because it would be more costly to the credit rating agencies. Thus, the credit rating lower their credit ratings irrespective of any information available to them and investors would rationally discount CRAs’ rating downgrades which would result in loss of information of the credit ratings.

Taking into consideration the events mentioned above regarding the regulatory framework changes, the research question of this thesis is if the credibility, accuracy and timeliness of the credit ratings have changed before and after the financial crisis and implementation of these regulations. For the purposes of this research, via qualitative inquiry and quantitative descriptive statistics, the paper seeks to shed light to support the inference that rating agencies lack in timeliness and understand if credit ratings have any informational content. The paper is intended to provide a theoretical knowledge of what credit rating and agencies stand for, their history and evolution.

It is also a research based evaluation of some of the principal criticisms and point to some of the lessons learned from several financial crisis in terms of regulations to shed more light on the argument for and against regulation and to what extent if any the credit rating industry should be regulated. Thus, the paper intends to reach to conclusion about the credibility of the CRAs and the timeliness of the ratings and the informational value of these credit ratings.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 presents background information on credit ratings and the credit rating industry and prior literature review, Section 3 shows Hypothesis Development, Section 4 includes Methodology, Sections 5 include results of the empirical research conducted and conclusions are presented in Section 7.

Background

A credit rating is an assessment issued by a credit rating agency about the credit quality of a debt issuer or a specific debt obligation (SEC [2005a]). A credit rating consists of a letter grade and commentary where commentary includes assumptions, criteria, and methods used to determine the rating opinion. These conditions was used by the credit rating agencies to change credit ratings, information about the rated company and details related to it like its lines of business. The three prominent credit rating agencies in the financial market provide detailed, freely available information on letter ratings and commentary as well as offer fee-based services that provide additional information and data to subscribers. The credit rating detail disclosed to public is strongly influenced by the primary income source of the credit rating agencies. Corporate credit rating opinions are assigned at the issuer level and to specific fixed payment obligations undertaken by these issuers generally debt and preferred stock. Ratings of specific issues are created by first rating the issuer and then making adjustments based on such features as seniority. Undisclosed or confidential ratings are those that are provided only to the rated issuer when they purchase it.

Credit rating agencies are information intermediaries whose business is the reduction of information asymmetry between debtors and creditors. In current context, although dominated by the three big and main players like Moody, S&P and Fitch, there are numerous credit rating agencies that operate globally and several others that strive for industry or geographic niche markets. The three largest CRAs apply a combination of quantitative models and qualitative analysis for credit ratings. Several credit rating agencies smaller in size rely mostly on quantitative models, enabling them to rate all issuers in a given marketplace with limited resources. The credit rating process by the credit rating agencies involves analysis of both business risk and financial risk. The large CRAs use a committee process to evaluate issuers. Following company visits by analysts, rating committees meet to discuss analyst recommendations and the pertinent facts supporting the rating. After the committee votes, the company is notified of the rating and major factors supporting it. The issuer is allowed to present additional data in response to the rating decision before the rating is published.

In the United States, credit rating agencies were largely unregulated in the early periods. The first prominent regulations on credit ratings began in 1931 basically because were required to mark-to-market lower rated bonds and by 1936 they became popular as U.S. Treasury Department specified that unless the bonds were considered “speculative” by “recognized rating manuals” the banks could not invest. These regulations represent the biggest initial events with regard to ratings regulation. However, there are no prior literature or research that I could that indicate how effective or what impact these regulation on credit rating agencies.

The only significant change to regulatory landscape in credit rating industry from 1930s until 1975 would be the Securities Valuation Office (SVO) established by the National Association in 1951. Securities Valuation Office (SVO) assigned risk ratings to bonds held in the investment portfolios of insurance companies. These ratings would be used to determine insurance companies’ capital requirements. At this time, the NAIC began equating the term “investment grade” to bonds with a Baa-rating or better. Investment grade bonds were therefore bonds with a rating of Baa (BBB) or higher by Moody’s and S&P; and speculative grade bonds also known as junk bonds or high-yield bonds are those with a rating of Ba (BB) or lower by Moody’s and S&P respectively.

Credit rating industry has been heavily criticized with the argument that there are several policies and procedures followed which leads to potential tampering of the entire process. The want of higher and better ratings for investment would cause companies to create their own rating agency and allow it to issue their investments higher rating. SEC addressed this issue on June 26, 1975 by using only the credit rating issued by Nationally Recognized Statistical Rating organization (NRSRO). This was implemented in order to set a benchmark and establish the standard for defining acceptable credit rating agencies in the industry. The act of SEC was accepted well by the credit rating industry and all the other regulators and the financial market soon joined in to accept only the NRSRO issued credit ratings.

This new regulation in 1975 was probably another landmark event in the history of regulation for credit rating agencies. The 1975 rules contained two major parts that makes it important landmark in the history of regulation. The first was that the acceptance of only NRSROs given credit ratings gave significant power to these certain credit rating agencies. Secondly, there was an additional annex to this new regulation adopted by SEC called Rule 15c3-1 for broker-dealers which set the requirements for the value of their relationship and based it on the credit ratings of the securities. As per the rule, SEC applied a new net capital rule to calculate the capital requirements owned by broker-dealers according to which credit ratings became the foundation for determining the percentage reduction in the value of bonds.

For several years post the regulation of 1975, SEC became a substantial barrier to entry. NRSRO designation was given to only four credit rating agencies and after the merger of Fitch in 2000 the number of NRSRO designated credit agency had reduced to only three. One of the major flaws with this whole process was that SEC had no open and defined set of criteria mentioned for the credit rating agencies to attain this NRSRO designation. Thus, when the fall of Enron happened journalists got further instigated and discovered that the three major NRSRO designated credit rating agencies had continued to uphold the Enron’s investment-grade ratings until five days of it is collapse. SEC officials were interrogated about the NRSRO system, its management and the monopoly within the industry. This event made SEC go through a lot of skepticism and under pressure additional credit rating agencies were granted the NRSRO status. However, congress dissatisfied with entire process took matters in their own hands and enacted additional legislation in 2006. That specific legislation would cater to specify the need for criteria to be follow in designating credit ratings agencies the NRSRO status and granting SEC the power to gather more information and keep a regulatory oversight over the credit rating agencies and the ratings they issue.

The US Credit Rating Agency Reform Act which was enacted in 2006 thus further created a new section- Section 15E of the Exchange Act-that established a regulatory framework for a registration and recognition process. According to the act, credit rating agencies needed abide to rules of this regulation to maintain the NRSRO status. Section 15E enabled NRSRO to be responsible for creating, maintaining, and enforcing written policies and procedures. These policies and procedures of regulation were formulated for seamless recordkeeping purposes like providing the necessary details to the SEC when the credit rating agency files the registration statement for its NRSRO recognition, updating on an annual basis the data found in the initial registration statement and solving any possible conflicts of interest. Section 15E intended to prohibit coercive practices of credit rating agencies, and allowed SEC to issue rules to forbid or require the management and disclosure of conflicts of interest. Revocation of the registration of any NRSRO that is unable to monitor the financial and managerial resources properly to reliably produce accurate and timely credit ratings is also one of the authorities granted to SEC by Section 15 E.

The financial crisis and the rising allegation on the role that credit rating agencies had in the chaos compelled the SEC to continue its momentum for increasing the oversight upon credit rating agency (Dimitrov, 2015). In 2009, the SEC adopted several additional regulatory framework changes. These new added regulation would bring positive changes like transparent rating methodologies and performances of credit rating agencies, proper and accurate recordkeeping and reporting obligations of NRSRO to ensure NRSROs’ compliance with regulation and regular monitoring by SEC of these records and reporting obligation. In July 2010, the most significant credit rating agency regulation was passed by Congress in response to the Global Financial Crisis of 2008-2009 – Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act (Dodd-Frank). This new regulation passed in 2010 post the financial crisis is also one of the event of importance for this research as well.

The main intention of the new regulation was to improve rating stability, accuracy and credibility by increasing competition. In order to achieve the desired result, the regulation intended to remove barriers to entry of new rating firms through a formal but voluntary registration system. The new law also approved regulation that debt issuers should pay for ratings instead of investors to avoid conflict of interest. However, several arguments were put forward that the credit ratings were lower, less accurate, and less informative to the market following the passage of Dodd-Frank since the reputation effect outweighs the disciplining effect of Dodd-Frank in the market for corporate bond credit ratings. (Dimitrov, 2015).

There have also been several empirical and anecdotal evidence that indicate that the quality of ratings varies significantly due to various factors which made it less credible reliable and timely. For instance, the credit rating agencies have failed to predict significant credit events be it the Asian crisis of the late 1990s, the Enron and Worldcom bankruptcies, or the global financial crisis of the late 2000s. Due to this, there were several debate that the credit rating industry needed to be more regulated and monitored.

Consequently, Congress passed regulations like the Credit Rating Agency Reform Act of 2006 and the Dodd-Frank Act of 2010. These regulations were implemented with the intention of improving accuracy and timeliness of credit ratings through increased competition and transparency. These events and different line of thoughts have also inspired and encouraged a line of academic research investigating the underlying causes of variation in the quality of credit ratings and the factors that affect the accuracy and timeliness of these ratings.

There are several empirical studies and past literature on the credibility of credit rating, timeliness of the credit ratings, if it carries any informational value and their eventual impact in the financial market. There have been several researchers like Xia (2013), deHaan, E. (2013), Jorion and Zhang (2007), Löffler G. (2004), Norden and Weber (2004), Klepczarek, E. (2015), Dilly, Mark and Mählmann, Isaia, E., Damilano, M. (2017), Kim, S., & Park, S. (2016) who have studied about credit rating agencies and have been able to contribute significant findings about it that could be useful for my research.

There are basically three distinct types of empirical research that have been done on credit ratings in the past (Blume et al., 1998). The first type of research examines whether credit ratings agencies measure what they intend to which is the creditworthiness of the issuers. Zhou (2001) and Jorion & Zhang (2007) examined this subject by measuring the relationship between rating and default. The research will be using these type of evidence on my paper to understand the concept of credibility of rating agencies, the methodology and regulation adopted before and post financial crisis, what creditworthiness would mean and how efficiently they do this to gain credibility in the financial markets.

The second type of empirical research measures the informational value of credit ratings issued to corporation in the financial markets. The response of financial market because of credit rating changes are evaluated to see if ratings contain information content not found from somewhere else. While researchers like Jewel and Livingston (1999) emphasize that credit ratings provide significant informational value, others like Partnoy (2001) stress that ratings do not provide much informational content, and that stock price changes take place before any credit rating fluctuations new releases. Several researches who disapprove the role of credit rating agencies, believe that in fact rating releases cause market lag. This reinforces expectations and responses of investors, leading to instability in financial markets. Altman and Saunders (2001) also echo the same opinion which suggests that credit rating agencies are slow and inflexible which question the objectivity and timeliness of their ratings.

The third type of research investigates the several determinants of credit ratings. Although CRAs estimate creditworthiness of a corporation irrespective of impacts of temporary business cycles, credit ratings do get affected by business cycles. Therefore, macroeconomic variables such as financial statements, financial ratios (Amato & Furfine, 2004) and corporate governance features (Bhojraj & Sengupta, 2003) are determinants of credit ratings. These studies show that credit ratings could be replaced by using publicly available data and that the financial statements could be the main factor in determining credit ratings. Also, corporate governance mechanisms that solve agency issues between management and stakeholders and effect possible wealth redistribution from bondholders to shareholders are relevant to determine the creditworthiness of a corporation.

Apart from theses, there have been works of several researchers like Dichev and Piotroski (2001), Holthausen and Leftwich (1986), and Hand, Holthausen, and Leftwich (1992) which shows investors respond to credit rating publications from the agencies especially in case of credit rating downgrades than for upgrades as downgrades have a greater response. The focus of the research however is mainly on prior work that explores the relationship between credit ratings agencies, ratings and regulatory changes over time and its impact on the credit ratings.

There have been a numerous arguments backed by theoretical standpoint, in favor of regulation that are based on a varied set of standards. Historically, regulatory oversight has been imposed or tightened in the credit rating industry whenever there has been a major critical event in the financial market and the credit rating industry has not been alleged to be responsible for it. Several policymakers in the United States and around the world have considered the possible measures to make rating agencies more accountable, rating processes more transparent and the credit rating more timely and accurate. However, after a comprehensive review it was revealed that despite the large number of different aspects discussed by practitioners and researchers, there were only of few persuasive arguments about the possible reasons for regulating the credit rating industry. The most common reason for more regulation being in response to the increasing monopoly power in the credit rating industry and the problem of windfall profits. (Breyer, 1982)

Fisch (2004) in his paper reasons that to bring about a reformation in the broader corporate landscape it is essential to have increased regulatory pressure or at least some additional clarification of some of the relevant regulatory procedures relating to the credit rating agencies. He further add that the credit rating industry needs such policy and regulatory measures to monitor the credit rating agencies and have a transparent process. Fisch, however, admits that the positions that his paper supports are driven by abstract reasoning and not based on any empirical research. He further adds to his point that before implementing any reform kind of regulatory measures, further empirical evidence needs to be collected and analyzed to determine the extent to which the reforms helps to enhance the relevant features of the regulatory framework market for credit rating or the extent to which it contributes in further distortion of an already present susceptible regulatory framework.

Along the same lines, Jorion, Liu, and Shi (2005) find that after the Regulation Fair Disclosure (RegFD) in 2000 the response and information content of both credit rating downgrades and upgrades is greater. The authors also find that the stock price response to rating changes became more pronounced following the implementation of Reg FD. They also provide analysis that the commencement of the RegFD the equity analysts do not have access to companies’ confidential information and hence less chances of manipulation which increases the information value of credit ratings because under that act. This consistent with the view that CRAs do use their access to confidential information, and that their ratings actions convey more information to the market as a result.

Similarly, Cheng and Neamtiu (2009) find if credit rating agencies issue more timely downgrades, increase rating accuracy, and reduce rating volatility following the passage of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act in 2002. Their research studies the credit rating agency and their role in the financial market under increased regulatory scrutiny and extreme criticism for timelines of the ratings of the credit rating agencies. Their study examines whether and how rating agencies respond to these increased regulatory scrutiny and criticism and reach the conclusion that the credit rating agencies improve rating timelines and rating accuracy along with reducing rating volatility. They are in support of the arguments that although in the past the credit rating agencies have failed due to less efforts and not adopting the correct methodologies when increased regulatory pressure threatens their influence in the financial market and reputation, credit rating agencies tend to respond by improving their credit analysis and ratings.

There have been several researchers who have analyzed the relationship between the increasing regulatory pressure in the credit rating agencies and their performance and the quality of credit ratings. Dimitrov, Palia and Tang (2015) analyze that the impact of regulation especially the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act (Dodd-Frank) on credit ratings. The evidence from their research suggests that rules and regulations like Dodd-Frank although monitors credit rating agencies, they do not regulate the credit rating agencies enough to issue more timely, accurate and informative credit ratings. Their paper furthermore investigates that after the implementation of regulation namely the Dodd-Frank act, the credit ratings issued by the CRAs are lower ratings with false warnings and downgrades with less informative content.

Consistent to that, like mentioned previously in this paper, the work of Morris (2001) is closely related to regulatory changes in the credit rating industry and the influence of that in the timeliness and accuracy of the credit ratings issued by the credit rating agencies. Morris (2001) suggests that regulations especially after the financial crisis following the founding of Dodd-Frank Act, credit rating agencies when pressured with regulatory changes tend to become more conscious and defensive about their reputation. Morris in his paper concludes that there are adverse consequences on the quality of credit ratings due to increasing the legal and regulatory costs to

There have been certain researches that highlight the involvement of credit rating agencies in the financial crisis and what went wrong with them. Voorhees (2012) emphasized by giving higher ratings to poorly understood new financial instruments, credit rating agencies where highly involved in the financial crisis. The research pointed out that credit rating agencies had strong conflict of interest and also lacked significant responsibility and oversight as they were not properly regulated or monitored. Cathcart, El-Jahel, and Evans (2013) analyzed the credit default swaps market after the 2008 financial crisis and found that corporate credit ratings were regarded as less credible.

Alp (2013) researched about the correlation between increasing regulation in credit rating industry increasing problems and crumbling financial industry. He found out that there was definite trend of financial moving towards more strict and stringent rules and regulations in ratings in 2002 due heightening regulatory scrutiny and criticism post the Enron and WorldCom collapse.

There are also some specific research studies that are closely related to the work in is the paper. Goel and Thakur (2011) propose that there might be an adverse effect on the quality of credit ratings due to the increase in legal and regulatory penalties under Dodd-Frank. The reason being that these penalties are asymmetric, whereas CRAs are penalized for optimistically biased ratings but not for pessimistically biased ratings (Goel and Thakor (2011)).

Secondly, Dimitrov et al. (2015) also using bond price reactions to rating changes compares ratings’ level and informative content post the Dodd-Frank regulation period which commenced after 2010. Through their research they discovered that the probability of no default within a year, which they termed as false warning, while receiving a rating lower than BB+ increased after the passage of Dodd-Frank regulation. Also, they found out that that bond prices are less responsive to bond downgrades in the post regulation period compared to their pre-regulation period (01/2006-07/2010).

In contrast, Jankowitsch et al. (2016), observes information content of credit rating over three periods: a pre-crisis period (prior to 2007), a crisis period (2007-2010) and a post regulation period (after 2010). They infer in their research that for non-financial bonds, bond price reaction is significantly stronger after the passage of regulation in 2010 compared to that in period before financial crisis. In addition, they find that during the financial crisis period, non-financial bond prices are less responsive to downgrades compared to the period before the financial crisis, after controlling for liquidity. The findings in Jankowitsch et al. (2016) is opposite to the findings in Dimitrov et al. (2015).

Bozanic and Kraft (2015), demonstrates that credit analysts collect the information conveyed by borrowers’ qualitative disclosure in ratings based on soft adjustments. They further find that in the post regulation period of greater regulatory monitoring and scrutiny, credit rating agencies appear to rely less on acquiring and processing costly qualitative disclosure, and thus the reliability and accuracy for rating downgrades involving soft adjustments would be diminished.

Hypothesis

Following the Enron and Worldcom debacle and more so after the global financial crisis in 2007-2208, the credit rating agencies especially the nationally recognized rating agencies faced intense investor criticism and reputation concerns with respect to the timeliness and accuracy of their ratings. In 2002, Association for Financial Professionals conducted a survey according to which corporate treasuries and financial officers believed that credit rating agencies were inefficient in responding to changes in corporate credit rating quality in terms of timeliness and accuracy. The investor argued that this inefficiency of the credit rating agencies was due to lack of enough competition which killed the credit rating agencies’ incentive to respond to rating users’ needs in a timely fashion with reliability (Ip, 2002; Tafara, 2005).

Credit rating agencies’ lack of timeliness has been highly criticized in predicting some high-profile bankruptcies attracted regulatory scrutiny. Regulators have specifically questioned the thoroughness of these credit rating agencies’ review of bankrupt companies’ public filings and whether they investigated vague financial disclosures and aggressive accounting practices (SEC, 2003). After the financial crisis the criticism increased and caught a new momentum about the regulatory review process. The argument for regulation has been that regulation help to the maintain and monitor regulatory oversight of rating agencies and also foster more healthy competition which will push the credit rating agencies to give reliable and timely ratings. There has constant momentum against any regulation of credit rating agencies as well. Throughout this regulatory scrutiny period, the credit rating agencies have ardently criticized, opposed and lobbied against more regulation of their industry (Partnoy, 2001). The basis for their argument against the regulation is on the grounds that the credit risk assessments and rating methodologies of the agencies would be doubted upon which would cause them to compromise on their independence and integrity, which is crucial to the credibility and reliability of credit ratings.

Thus based on this contradicting arguments, we hypothesize that, when faced with increased rules and escalating regulatory pressure, the credit rating agencies improve the most criticized aspect of their ratings, i.e., timeliness and accuracy of their credit ratings. To investigate potential changes in rating timeliness, we focus on the timeliness of credit rating downgrades with respect to abnormal returns. Thus, the hypothesis for the research stated in an alternative form would be:

H1: Accuracy and timeliness of corporate ratings before and after the financial crisis with regulation implemented.

In other words, with the advent of financial crisis, the financial industry was very concerned and there were several regulation that were formed and implemented post the 2007 crisis. As a consequence of these regulatory changes that occurred between 2005 and 2010, in our hypothesis, we express our theory which explores the idea that credit rating agencies may have altered their accuracy of ratings and improved their timeliness in years after 2010. Through the research, we intend to assess the existence of breaks in the parameters that capture timeliness and accuracy of ratings, consists in splitting our sample in two distinct periods with the purpose of comparing sub‐sample estimation results: the pre-regulatory period before 2010; the post‐regulatory change period after 2010.

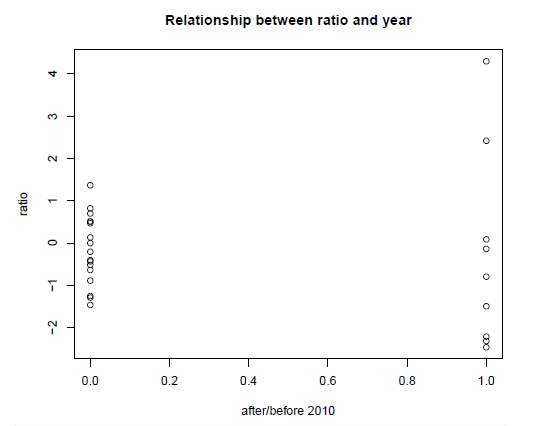

So, the primary analyses was carried out by retrieving the downgrade ratings, calculating the abnormal return and then ratio of abnormal return. Then, after setting 0 for event date before 2010 and for any event date 2010 or after as 1, a statistical test is run according to the following specification: Y= b0+b1 x1, where: Y= ratio of abnormal return one year prior to rating change divided by abnormal return one year after rating change. Here, x1 is a dummy variable that takes the value one prior or in correspondence to the post period and zero otherwise i.e. x is 0 for 2010 or before and 1 for 2011 and after.

Thus, considering the background work and prior literature concerning the regulation of CRAs, assumption similar to that argued by Cheng and Neamtiu (2009) may be reasonable which is when pressured to improve their timeliness and accuracy post the implementation of regulation credit rating agencies weaken the perception and tend to issue ratings that they may not be accurate and credible. However, whether the credit rating agencies would improve the timeliness and accuracy of their credit ratings due to regulatory pressure is still an open question. Given the oligopolistic structure of the credit rating industry and the fact that large market share is covered basically by three nationally recognized credit rating agencies, it is uncertain whether apprehensions about reputation and regulation are strong simulators to make these agencies act as desired. In addition, if the argument posed by the credit agencies is correct and timeliness and accuracy are inversely correlated, then the credit rating agencies may not significantly improve timeliness of the credit ratings because they do not want to sacrifice rating stability and accuracy.

This research is primarily interested in examining whether the credit rating agencies can attain the anticipated progress in timeliness without sacrificing stability and accuracy post the financial crisis period when regulation was implemented as the financial market and credit rating agencies mutually acknowledge that both timeliness and stability are important.

Methodology

The most important and crucial aspect of any research is the collection of the appropriate information which provides necessary data and information that will help reach the conclusion. This research is combination of theoretical analysis of past literature and empirical research. The research will be looking at secondary data from the past literature to understand more about the credit rating agencies, their history and the evolution of regulation in this credit rating industry. Moreover, the study will be aiming to understand how these changes in regulatory framework in the industry has impact the credit rating agencies and importantly the credit ratings they issue. The emphasis will be to analyze the impact of regulatory changes especially on the timeliness and accuracy of the credit ratings.

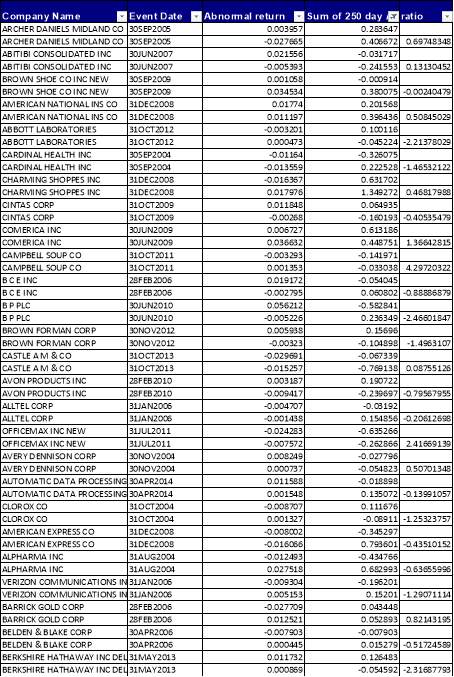

The empirical test will use different samples based on the data requirements. Data is gathered from different credible online data sources like WRDS, Moody’s, S&P, and Bloomberg. The analysis is focused on daily company returns to determine if the bond ratings are issued on a timely basis and were informative about downgrades. The sample construction commenced with retrieving a list of 30 firms placed with bond rating downgrades between 2005 and 2015. The following data was collected for firms at the time of listing from WRDS: 1) Company name, 2) Listing event date and 3) PERMNO (Table1). If there were any firms without PERMNO they were deleted. PRMNO and event date were then converted into a text file (Table 2).

The file was then uploaded to WRDS and used to extract company and market index, CSRP value weighted market index, event date daily return and market index. We measure the abnormal return for each rating change. The abnormal returns for the sample was then computed by subtracting the value weighted return from the daily company return. Then, we took trading day count for one year i.e. 250 days before and after the event day for each firm. After that, the abnormal return was summed up for each 250 days ending on the event date and the ratio was calculated (Table 1). I also marked the event date if the before or after 2010. After that, we took the ratio calculated and the event date and ran regression test in https://www.wessa.net/rwasp_multipleregression.wasp. (Table 4).

Results

Table 1 shows the sample firms for the research with event date and market-adjusted stock returns with credit rating downgrade announcements from 2005 to 2015 i.e. before and after the financial crisis and implement of several regulation like the Dodd Frank Act. The sample includes only returns for company with credit rating downgrades and excludes companies with credit rating upgrades. The table shows the credit rating downgrades by event year and also includes the sum total of ratio calculated for the event window of 250 days along with the ratio of abnormal return of the event window of 250 days or in other words ratio of abnormal return one year prior to rating change divided by abnormal return one year after rating change.

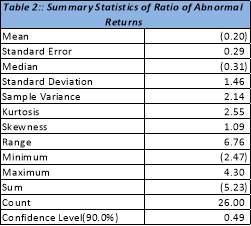

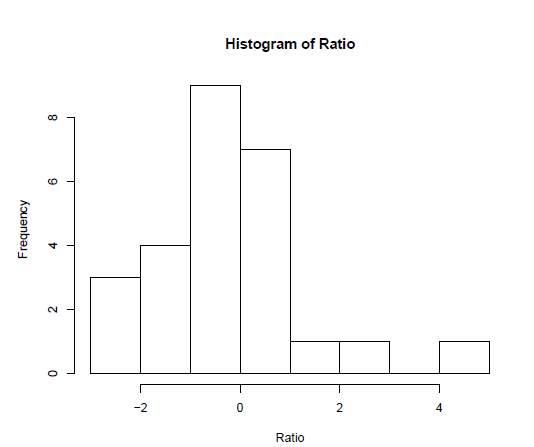

Table 2 shows the summary statistics of the ratios of abnormal return for the sample. There were total 26 sample of ratios. The mean and median of the ratio was -.20 and -.31 respectively. The sample minimum was -2.47 and 4.30 was the maximum, having a range of 6.76.

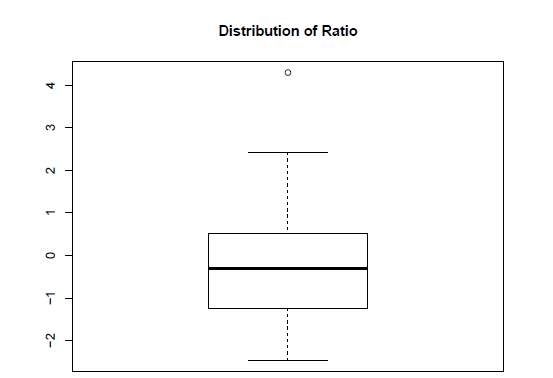

The graphical depictions below (Figure) also sample distribution of the ratios of abnormal returns which shows that the data is negatively skewed. For the purposes of this research, we did not take note of this skewed distribution for reviewing our results later. We ran regression tests and focused more on those results.

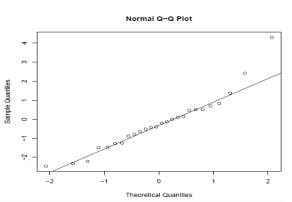

The final results of the research achieved after running the regression tests are reported in Table 4. This table shows regression results for credit rating codes for all credit rating announcements for U.S. corporate bonds between 2005 and 2015. The dependent variable is the ratio of abnormal return in the 250 days event window and the event year of 2010 is a dummy variable with a value of 1 for ratings assigned 2010 and after, and zero for ratings assigned before 2010. According to the results from the regression testing:

Multiple Linear Regression – Estimated Regression Equation is

Ratio of Abnormal Return= -0.152979 -0.14 (Years After/Before 2010) + Error

The coefficient is 0.14 and the p-value is 0.82 which indicates that result is not statistically significant. This indicates that the regulation have little impact on the accuracy and timeliness of the credit ratings issued by the credit rating agencies.

Conclusion

Credit ratings agencies publish credit ratings which represent the financial strength of the company and assesses the creditworthiness of corporate bonds. However, with time, the quality of these ratings and integrity of credit rating agencies has been constantly questioned. Credit ratings agencies have been associated with and blamed for in several significant controversy, and more so for their supposed role in the 2007 financial crisis, along with the Enron and Worldcom debacle and other high profile defaults. There are two crucial features that impact the quality of credit ratings. Fair competition in the credit ratings industry and the effective and efficient use of rules and regulations in the credit ratings are the two important factors. Despite all the controversy and understanding of the need for good competitive environment and appropriate regulations, reforms in the credit rating industry have not been remarkable.

To effectively address the concern regarding the credit rating agencies one needs to understanding the impact of these regulations on ratings quality, accuracy and timeliness. Thus, in the light of the debate on the alleged shortcoming in credit rating agencies’ conducts and practices before and after the Great Financial Crisis, many would be tempted to argue that the industry may need a further tightening of the regulations enforced. In this paper, we try to address this issue and examine one of the notable events in the history of credit ratings regulation, the introduction of the regulation and the use of those regulations in 2010 in the post financial crisis era. We attempt to investigate whether this landmark regulatory shift led to lower ratings quality in terms of timeliness and accuracy.

This study examines whether and how regulatory pressure post the financial crisis has affected the nationally recognized credit rating agencies to change their credit rating qualities in terms of timeliness and accuracy. The research hypothesized that credit rating agencies downgrade defaulting issues earlier in the post financial crisis with increased regulatory scrutiny than in the pre period. We also hypothesized that rating stability and accuracy should improve in the post period, suggesting that credit rating agencies improve rating timeliness by increasing the quality of their credit analysis, and not by sacrificing rating stability and/or accuracy.

However, we do not find any positive or significant coefficients for the specifications. The magnitude of the economic effect is mild, with coefficients of -0.14. This finding contributes the conclusions drawn that the implementation of the regulations in 2010 has no significant impact on the quality of credit ratings despite the higher barriers to entry and increased reliance on ratings in regulations that resulted from them. Supporting the prior literature, our study also finds that when credit rating industry encounters increased regulatory pressure and reputation concerns, credit rating agencies have less timeliness, as well as stability and accuracy of credit rating.

This research is subject to at least one limitation. Although all other economic factors that could affect credit rating properties has been controlled , we cannot completely rule out the possibility that our results are attributable, at least in part, to some other factor unrelated to regulatory pressure and criticism. We would need to add additional factors to research model and run it with more data to be able to reach some concrete conclusion. There can be also some addition research done to check if the regulation had any impact on some other aspect of credit rating quality other than timeliness and accuracy. This could be a scope for future research.

References

Isaia, E., Damilano, M. (2017). ARE RATING AGENCIES STILL CREDIBLE AFTERTHE SUBPRIME CRISIS?

Fisch, Jacob, 2004: “Rating the Raters”. Davis Business Law Journal, 5 (3): http://blj.ucdavis.edu/article/549/.

Adelson, Mark H. 2007. Bond rating confusion. Journal of Structured Finance 12: 41–48.

Altman, Edward I. and Saunders, Anthony, (2001), An analysis and critique of the BIS proposal on capital adequacy and ratings, Journal of Banking & Finance, 25, issue 1, p. 25-46

Lazareva, E. (2016). Do rating agencies confirm or surprise the market? Atlantic Economic Journal, 44(1), 133-134. http://dx.doi.org.rlib.pace.edu/10.1007/s11293-016-9486-6

Kim, S., & Park, S. (2016). Credit rating inflation during the 2000s: Lessons from the U.S. state governments. International Journal of Economics and Financial Issues, 6(1) Retrieved from https://search-proquestcom.rlib.pace.edu/docview/1809610457?accountid=13044

DeHaan, E. (2013). The financial crisis and credibility of corporate credit ratings (Order No. 3588667). Available from ProQuest Central; ProQuest Dissertations & Theses A&I. (1428427893). Retrieved from https://searchproquestcom.rlib.pace.edu/docview/1428427893?accountid=13044

Cantor, R., Mann, C. (2006) “Analyzing the Tradeoff between Ratings Accuracy and Stability”, Moody‟s Investor Service

Cheng, M., & Neamtiu, M., (2009). An empirical analysis of changes in credit rating properties: Timeliness, accuracy and volatility. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 47(1–2), 108-130.

Carvalho, P. V., Laux, P. A., Pereira, J. P. (2014) “The Stability and Accuracy of Credit Ratings”, Working Paper Series Confidential Presentation to Lehman Brothers. Credit Ratings Strategy, 2007, March 1

Heski, B. I., Shapiro, J. (2011) “Credit Ratings Accuracy and Analyst Incentives”, American Economic Review, 101(3): 120-24

Dilly, Mark and Mählmann, Thomas, Is There a ‘Boom Bias’ in Agency Ratings? (May 1, 2014). Forthcoming in Review of Finance; published by Oxford University Press. SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2336079 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2336079

Klepczarek, E. (2015). THE CREDIBILITY OF CREDIT RATINGS. Knowledge Horizons.Economics, 7(3), 33-38. Retrieved from https://search-proquest-com.rlib.pace.edu/docview/1696718391?accountid=13044

Bhojraj, S., & Sengupta, P. (2003). Effect of Corporate Governance on Bond Ratings and Yields: The Role of Institutional Investors and Outside Directors. The Journal of Business, 76(3), 455-475. doi:10.1086/344114

Blume, Marshal, Felix Lim, and Craig Mackinlay (1998). The Declining Credit quality of US Corporate Debt: myth or reality? The Journal of Finance, 53 (August): 1389-1413

Jewell, J., Livingston, M. (1999). A comparison of bond ratings from Moody’s, S&P, and Fitch. Finan. Markets, Inst. Instruments 8, 1-45

Breyer (1982), Regulation and Its Reform 2 (Harvard University Press).

Jorion, P. and Zhang, G., (2007), “Information Effects of Bond Rating Changes: The Role of the Rating Prior to the Announcement,” The Journal of Fixed Income, Vol. 16, pp. 45-59.

Morris, S., (2001). Political correctness. Journal of Political Economy, 109(2), 231-265

Partnoy, F., (2001), “The Paradox of Credit Ratings,” University of San Diego Law and Economics Research Paper No. 20.

Holthausen, R. W. and Leftwich, W.R., (1986), “The Effect of Bond Rating Changes on Common Stock Prices,” Journal of Financial Economics, Vol. 17, pp. 57-89.

Amato, Jeffery D. and Furfine, Craig H., (2004), Are credit ratings procyclical?, Journal of Banking & Finance, 28, issue 11, p. 2641-2677. https://EconPapers.repec.org/RePEc:eee:jbfina:v:28:y:2004:i:11:p:2641-2677

Voorhees, R (2012). Rating the Raters: Restoring Confidence and Accountability in Credit Rating Agencies, 44 Case W. Res. J. Int’l L. 875. https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/jil/vol44/iss3/33

Alp, A., (2013). Structural shifts in credit rating standards. Journal of Finance, 68(3), 2435-2470.

Cathcart, L., El-Jahel, L., & Evans, L., (2010). The credit rating crisis and the informational content of corporate credit ratings. https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/84bc/39a784ca54a31f8e7bad63b1929f960d50d6.pdf

Goel, A., & Thakor, A., (2011). Credit ratings and litigation risk.

Dimitrov et al, (2015). Impact of the Dodd-Frank act on credit ratings. https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/55c4/3109a2fd7b3f0f04bc4f8d95053110268f61.pdf

Bozanic, Z., Kraft, P., 2015. Qualitative corporate disclosure and credit analysts’ soft rating adjustments. Working paper. The Ohio State University and New York University.

Jankowitsch, J., Ottonelloy, G., Subrahmanyam, M.G., 2016. The new rules of the rating game: market perception of corporate ratings. Working paper. Vienna University of Economics and Business, Vienna Graduate School of Finance and New York University.

Ip, G., (2002). Companies keep closer eye on accounts – Enron collapse prompts more clout for raters, less business spending. Wall Street Journal. Feb 1, A2.

Tafara, E. 2005. Speech by SEC staff: remarks for the international organization of securities commissions annual conference panel on the regulation of credit rating agencies. Colombo, Sri Lanka, April 6.

Security and Exchange Commission. 2003. Report on the role and function of credit rating agencies in the operation of securities markets. Available from

Attig, N., El Ghoul, S., Guedhami, O., & Suh, J. (2011). Corporate Social Responsibility and Credit Ratings. Working paper, Saint Mary’s University, Halifax, NS

White, L. (2013). An Assessment of the Credit Rating Agencies: Background, Analysis, and Policy.

Wessa P., (2017), Multiple Regression (v1.0.48) in Free Statistics Software (v1.2.1), Office for Research Development and Education, https://www.wessa.net/rwasp_multipleregression.wasp/

Tables

Table 1: Sample firm and the abnormal returns

Table 2

Figure 1

Table 4

Multiple Linear Regression – Estimated Regression Equation:

Ratio of abnormal return = -0.152979 -0.138925 (year before/after 2010) + error

Table 4 shows estimates and standard errors (SE) of the estimates for the regression models: Model 1 with year before and after the regulatory change in 2010 as the predictor. The table displays information on the p-values associated with slope coefficient. The table also displays information about the model fit, including the R2 value, F-statistic, and RMSE for the model. All statistics have been rounded.

|

Regression Output: Model 1 |

||||||||

| Included Output: 26 | ||||||||

| * indicates a significance at a level of 10% | ||||||||

| Variable | Coefficient | Std. Deviation | t-Statistic | 2-tail p-value | 1-tail p-value | |||

| Intercept | -0.15 | 0.36 | -0.42 | 0.68 | 0.34 | |||

| Year | -0.14 | 0.62 | -0.23 | 0.82 | 0.41 | |||

| Multiple R | 0.05 | F-TEST (value) | 0.05 | |||||

| R-squared | 0.00 | F-TEST (DF numerator) | 1.00 | |||||

| Adjusted R-squared | (0.04) | F-TEST (DF denominator) | 24.00 | |||||

| p-value | 0.82 | Residual Standard Deviation | 1.49 | |||||

| Sum Squared Residuals | 53.41 | |||||||

Cite This Work

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing stye below:

Related Services

View allRelated Content

All TagsContent relating to: "Finance"

Finance is a field of study involving matters of the management, and creation, of money and investments including the dynamics of assets and liabilities, under conditions of uncertainty and risk.

Related Articles

DMCA / Removal Request

If you are the original writer of this dissertation and no longer wish to have your work published on the UKDiss.com website then please: