Counterculture in New York City, c.1964-1974

Info: 34432 words (138 pages) Dissertation

Published: 11th Dec 2019

| – Table of Contents – | |||

| Introduction | 1 | ||

| Chapter I – The Universities of the City

Divisions on the Campuses Universities and the Neighbourhood University Networks of Solidarity Fashions and Fads Unwitting Interactions – Alumni, Parents, and Other Students |

9

14 19 23 26 29 |

||

| Chapter II – Race and Ethnicity

Jewishness and the Counterculture Whiteness and the Counterculture Cosmopolitan Neighbourhoods – Greenwich Village to the East Village |

33

35 40 47 |

||

| Chapter III – Politics and Counterculture

Hippy Politics Influence on Mainstream Political Protest Politics of ‘Decline’ in New York City Conclusion |

54

55 59 64 68 |

||

| Bibliography | 70 | ||

| – Abbreviations –

CCNY – City College of New York CUNY – City University of New York ESSO – East Side Social Organisation GAA – Gay Activists Alliance GLF – Gay Liberation Front LIU – Long Island University MANA – MacDougal Street Area Neighbourhood Association NYU – New York University SDS – Student Democrat Society SNCC – The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee TS – Transcendental Students (New York University Student Group) U.C. Berkeley – University of California, Berkeley YAF – Young American’s for Freedom (Columbia University Student Group)

– Figures and Illustrations –

|

|||

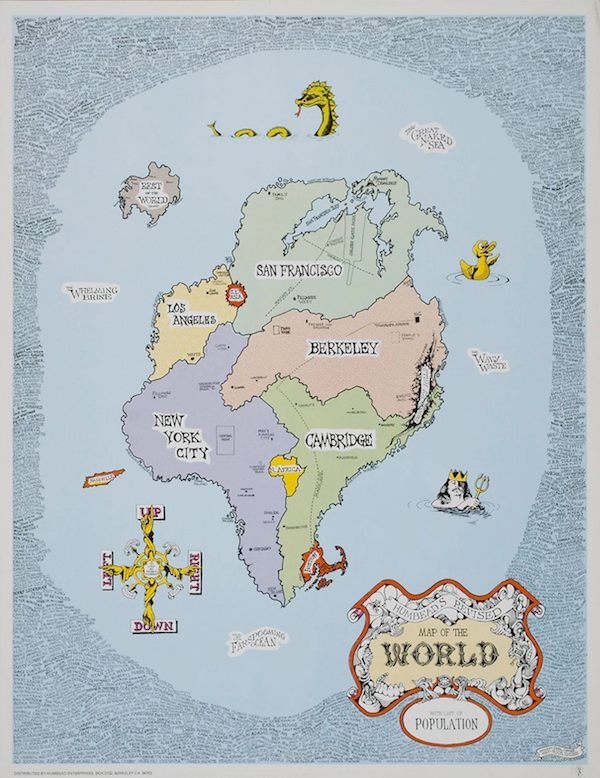

Fig-1.[1]

‘…it provides the independent verification of the fallacy of space, and that pernicious reasoning that makes New York and Berkeley seem far apart on normal maps…’ [2]

Introduction:

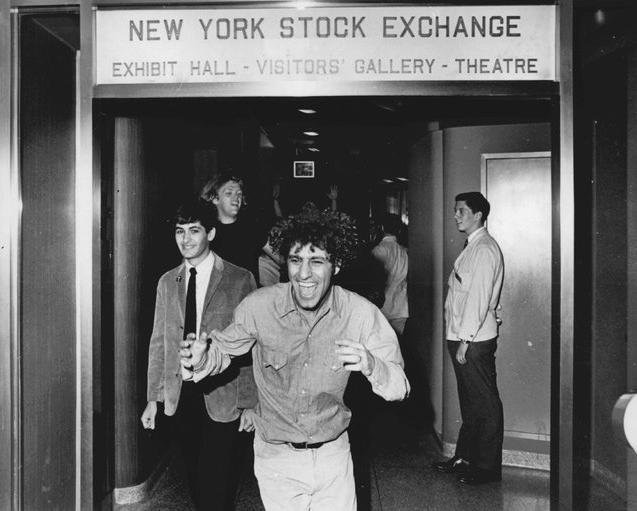

Abbie Hoffman, who co-founded the countercultural Youth International Party (dubbed the ‘Yippies’), noted in his 1980 memoir, Soon to be a Major Motion Picture that he had ‘an inner calling’ to be ‘headed for New York and big-time protest.’[3] The countercultural figure – a former student at U.C. Berkeley and one of the Chicago Seven arrested at the Democratic National Convention in August 1968 – was aware that there was something special about New York City.

New York’s Greenwich Village has long been known as a countercultural hub, deviating from the rest of the metropolis and the nation at large for the most part of the twentieth-century.[4] This dissertation will attempt to square this with what Jeremy Suri has called the ‘International Counterculture’[5] of the 1960s and early 1970s, and this bifocal study aspires to add both to the historiography of the city and the counterculture. Residing in the Village in the 1950s, the famous ‘Beat’ poet Allen Ginsberg found himself travelling to thirty-odd colleges around the nation in 1968 alone.[6] This, alongside the U.C. Berkeley journalist’s comment on Humbead’s Revised Map of the World (on the previous page) illustrates that the countercultural creations of New York City were significant to the counterculture at large.

Peter Braunstein and Michael Doyle, editors of the first academic volume on American counterculture, warned historians of attempting to ‘construe [it] as a social movement.’[7] They appropriately cautioned that ‘it was an inherently unstable collection of attitudes, tendencies, postures, gestures, ‘lifestyles,’ ideals, visions, hedonistic pleasures, moralisms, negations, and affirmations.’[8]

One issue with counterculture for historians is that it is like a mirage. Being too reductionist or specific – concentrating on one group (hippies, students, or one commune), an individual (Allen Ginsberg, Bob Dylan, or Joan Baez), a theme (feminism, youth culture, guerrilla theatre, musical performance), or an event (Woodstock Festival, Columbia Student Protests in 1968) – spontaneously dissolves the eclecticism vital to the counterculture’s character.[9] Nevertheless, it is also important to avoid such an expansive concept of culture which would make it look, as critics of cultural history often warn, ‘like all and nothing.’[10]

First coined academically by Theodore Roszak in 1969, commenting on the rumblings of the decade, the historian prefaced his work by noting that the counterculture drew parallels with the Renaissance; criticized for anachronistic terminology, yet still useful for encapsulating the spirit of the age.[11] The term featured sporadically in the New York Times from the mid-1960s, and was increasingly evoked in the early 1970s, yet ‘counterculture’ was not widely used as a point of reference, while hippies and other terms were.[12]

Thus, it is understandable why historians have become so tongue-twisted by the concept of counterculture.[13] This dissertation argues that counterculture retains distinctive characteristics that cannot be summed up by hippies alone. Ronald Martin helpfully illustrated that lessons can be learned from Benedict Anderson’s work in historicizing ‘nationality’ in Imagined Communities.[14] Retrospectively, the counterculture has garnered ‘profound emotional legitimacy’ akin to a nation.[15] Developing Martin’s (briefly made) point, Abbie Hoffman titled his 1969 book Woodstock Nation.[16] Originally relating to the upstate New York festival-goers, the term later referred to subscribers of the festival’s values nationwide. Academic titles inadvertently traded on the idea of a countercultural ‘nation’ too.[17]

This dissertation’s original working definition of counterculture is ‘confident deviance.’ Alive to the diversity, but also limiting it to intentional rejection of social norms, counterculture was behaviour that self-consciously acted against the grain. The counterculture is therefore the nation of ‘confident deviance’ that horizontally strung together its adherents in the 1960s and early 1970s.

In 1966, whilst campaigning to become Governor of California, Ronald Reagan took issue with the behaviour of students at U.C. Berkeley and hippies alike, exclaiming ‘we have some hippies in California. For those of you who don’t know what a hippie is, he’s a fellow who dresses like Tarzan, has hair like Jane, and smells like Cheetah.’[18] But the counterculture occurred elsewhere, both in urban and rural enclaves of the country. Ronald Martin called for studies of counterculture in cities, especially in those, including Detroit, Chicago, Los Angeles, Philadelphia, Seattle and New York, which had such a strong underground press.[19] For urban areas, these underground newspapers indicated budding countercultural communities.[20]

But New York’s counterculture needs not be signposted by an underground press. Longstanding city traditions of counterculture, predating the international counterculture, from speakeasies to bohemian artists and the ‘Beats’, reaffirm most strongly the argument that the events of the 1960s were an evolution of earlier countercultural traditions.[21] Yet up until now, little work has explored how the international counterculture played out within the city.

Looking solely at New York City has its merits. Echoing George Chauncey’s academic justifications in Gay New York, the study of a theme, such as counterculture, within a city ‘makes it possible to study broad questions with a greater degree of precision and specificity than would otherwise be possible.’[22] It is possible to illustrate networks, so too to look at issues such as ethnicity and politics, whilst simultaneously retaining a holistic picture of the counterculture. Additionally, the city was important as a hub of cultural creativity, ‘exercising enormous political, economic, and cultural influence both at home and abroad’ in the post-war years.[23]

John Steinbeck wrote in 1953 that New York was ‘an ugly city, a dirty city. Its climate is a scandal, its politics are used to frighten children, its traffic is madness, its competition is murderous.’[24] A tradition of deviance existed, but the 1960s rocked the city afresh. The Harlem Riots of Summer 1964 saw six consecutive days of protests involving around 4,000 protestors, which unsettled its residents and which would prove instrumental in city politics’ conservative turn in the latter half of the decade.[25] On John V. Lindsay’s first day as mayor in 1966, a public transportation strike threw the city into chaos – foreboding of disruptions and difficulties on the horizon. Anti-war demonstrations gripped the city. From March to May 1968, Columbia University was thrown into chaos as student protests halted the functioning of the Ivy League college. Covering Lindsay’s mayoralty, Vincent Cannatto noted that ‘the political ground beneath him shifted dramatically. Student radicalism, the counterculture, racial tensions and riots, growing conservatism, and anti-war protests made Lindsay’s brand of earnest, idealistic, good-government liberalism seem quaint and ineffective and helped create an aura of chaos and dissension beyond his control.’[26] It is this very sense of ‘decline’ that the counterculture, as the earliest histories note, was said to have created.[27] But as David Farber stressed, seeing the counterculture as causing something would be ‘mistaking an effect for a cause.’[28]

This dissertation argues that any focus of the counterculture around ‘1968’ is unnecessarily reductive, and belies its regenerative quality and ingenuity over the period.[29] It thus fills the void between the ‘Beats’ of the 1950s and 1968 and illustrates that counterculture did not expire as Richard Nixon entered the White House. Instead, its energies and membership diffused into the cultural liberation movements of the 1970s.[30]

It also reconceptualises the counterculture so that membership of the nation of ‘confident deviance’ is seen along a sliding scale. While ‘hippies’ and those at communes are traditionally seen as the strongest countercultural characters, it is important not to discount those college students who grew their hair, who started taking drugs recreationally, and others that were weakly affiliated with the air of confident deviance. Through this altered understanding, the contribution that counterculture made to ‘mass chaos’ within the city becomes clear.

The first chapter tests the role of New York’s universities in the counterculture. Traditionally seen through Columbia University’s uprisings in 1968, it explores the longer 1960s and includes other universities – so-called ‘commuter schools’ of the City University of New York (CUNY) – which have rarely been examined. The blossoming of American universities in the post-war period fostered new educational environments where avant-garde intellectual and artistic ideas thrived – environments formerly attributed to bohemian neighbourhoods of the city.[31] Through using material from numerous university archives, it concludes that there were good reasons as to why private campuses at NYU and Columbia, rather than the public CUNY campuses, would become strong centres of New York’s counterculture. Despite divided university campuses, solidarity between students of different universities fostered a countercultural network across the city, contributing to a nation of confident deviance.

This study has made use of a rich variety of previously untapped archival material extracted from both New York’s university and city archives, revealing the bustling nascent counterculture existent on both campuses and the city at large. Memoirs, diaries, interviews, visual material as well as articles from the underground press and other media, have augmented this archival research.

Kenneth Kmiel noted that ‘a very visible counterculture began to surface in 1964,’ with the first Beatles’ visit coinciding with long hair becoming fashionable.[32] Initially, the counterculture was most visibly a revolution of clothing, fashion and music. Braunstein and Doyle use the same periodisation, dividing the counterculture between the ‘hippie’ phase (up until 1968) and cultural liberation movements in the years afterwards, but the third chapter argues that the counterculture’s political wing was alive and kicking well before 1968 – it was just not seen as particularly threatening as radical politics of the latter part of the decade.[33]

The second chapter explores how New York City’s cosmopolitan character influenced its 1960s counterculture. The ‘Jewishness’ of New York is distinctive, and a disproportionate number of countercultural figures, on and off campuses, were Jewish, yet little countercultural scholarship explores its consequences. So too, critiques of counterculture’s ‘whiteness’ by Black Power groups is well known in the field, but this should not lead to an automatic conclusion that New York’s counterculture was racially exclusive. The strongest enclaves of the counterculture in downtown New York, in Greenwich Village and the Lower East Side, were also neighbourhoods for recent immigrant communities. Coexisting alongside hippies was, for these groups, an emotional rollercoaster: at times hostile, other times ambivalent, occasionally cooperative.

The final chapter responds to Christopher Gair’s call to recover the politics of the counterculture. He aptly noted that ‘the cultural artefacts of the ‘60s are canonised but the political agenda that accompanied them is discredited or overlooked.’[34] City archives, corroborated by newspaper reports, reveal that the supposedly ‘a-political’ hippies engaged with neighbourhood politics. So too, the counterculture fed into narratives of decline that had convulsed city politics by the mid-1960s.[35] And while counterculture’s legacy is discernible in early 1970s liberation movements, political activism of the 1960s (on and off campuses) was infected by the culture of ‘confident deviance’ in method.

The absence of any major study on New York’s counterculture of the 1960s and early 1970s is striking. By using new material from an array of university archives, as well as institutional and city papers, this dissertation goes some of the way to correcting this lacuna. While written in the knowledge that it would be hubristic to think a project of this scope can explore every aspect of this rich history, it is, nonetheless, hoped that this dissertation casts light on the wider history of New York City as well as the counterculture.

Chapter I: The Universities of the City

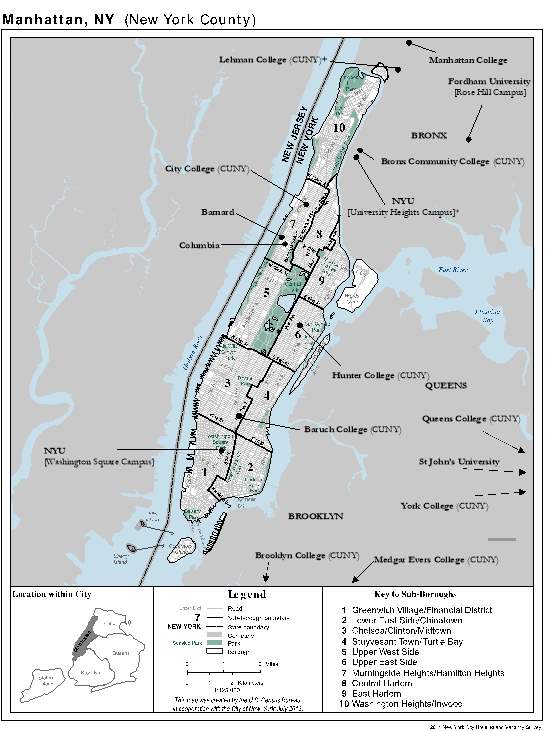

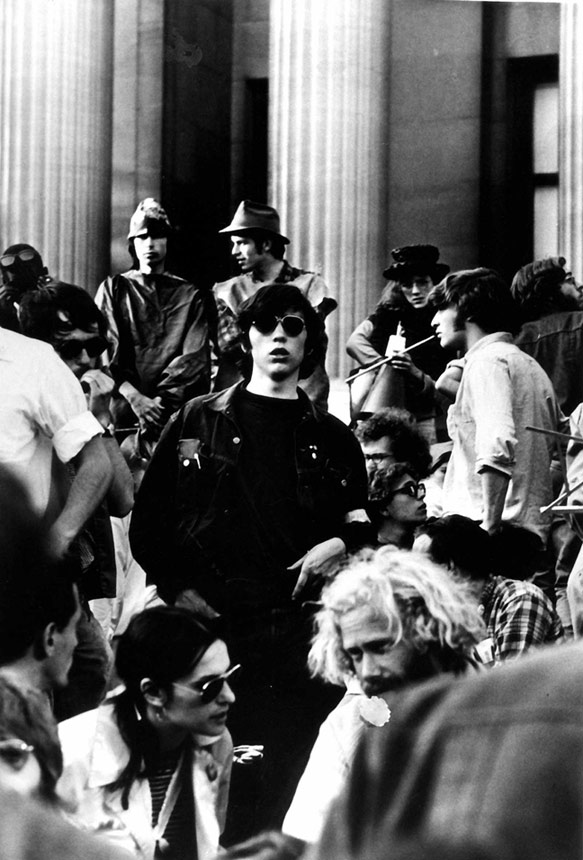

Fig-2[36]

‘You know, the 60’s on campuses like Columbia really began in like ’64, ’65. To all of this, you have to add in the counterculture with music, and clothing, and drugs. That’s the personal liberation, just breaking out of the culture and creating a new young people’s culture.’ [37] – Eric Foner

Fig-3[38]

Mid-way through term on March 6th, 1969 at New York University’s Washington Square Campus, 500 students occupied the South Study Hall for a five-hour ‘Freak In.’ Drinking chianti wine from unconventionally wide bottles, listening to fellow students perform, and smoking marijuana, the event – organised by the campus group Transcendental Students – pursued the group’s aims of bringing about ‘insurrection through happiness.’[39] One in eighty NYU undergraduates attended the event, and it was covered extensively in student publications including the Washington Square Journal.[40] It was only eleven days later that fifty students as part of the Hog Farm Commune descended on the Loeb Student Centre to organise a ‘happening,’ venerating a 300-pound sow named ‘Pigasus.’[41] The event, which saw students jumping into a thousand pounds in weight of pudding in the main hall in a giant vat, caused $2,000 worth of damage, attracted attention, and

distrupted the beating heart of the university.[42]

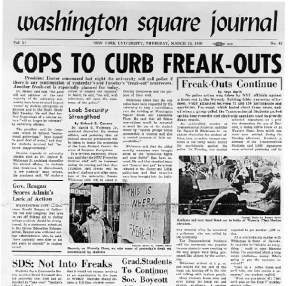

Fig-4[43]

These successive events, which might at first appear trivial and inconsequential, are illustrative of a tumultuous period of unpredictable and spontaneous student behaviour on college campuses. Yet solely recreating these stereotypical instances would add little to our understanding of the counterculture. As William Rorabaugh has argued, while ‘hundreds of thousands of young Americans were, at least for a time, hippies […] millions adopted some if not all hippie beliefs and practices.’[44] This chapter recovers everyday countercultural life at, and facilitated by, New York’s universities.

For every student that participated in these public acts and demonstrations, there others whose fashion trends were subtly shaped, but also those whose classes were cancelled. Parents and alumni reacted with disdain. University authorities had to react to impulsive student behaviour. Local residents interacted with and, at times, jumped on the bandwagon of campus counterculture. Student groups disagreed, others collaborated, and networks of allegiance between students from different universities were formed, forging a nation of those who affiliated with confident deviance.

Universities across the United States erupted in colourful protest in the 1960s, famously at U.C. Berkeley, Columbia, and the University of Wisconsin-Madison.[45] The post-war boom in higher education, which saw 40% of 18-22-year-olds attending university, was particularly pronounced in New York City.[46] In 1961 numerous colleges merged, becoming the City University of New York (CUNY).[47] Providing free tuition, through open admissions (from 1970), paid partly by the City of New York, CUNY changed the landscape of higher education of the metropolis.[48] Between 1961 and 1969, students under CUNY’s remit increased from 36,000 to 79,000, partly from acquiring colleges, partly by expanding institutions.[49] While teething problems of fast-growing CUNY in the 1960s have been historicized, little work has been done to include how students of public universities engaged with the decade’s counterculture.[50]

Differences between public and private universities were more significant than just that public universities were free. CUNY students were from the city, and by 1970, the colleges were beginning to reflect ethnic and racial demographics of their immediate vicinity. For private universities at NYU and Columbia, the 1960s saw a corresponding decrease in students from the city. In 1965, ‘58.5% of NYU’s freshmen were from outside the city […] as opposed to 35% in 1961.’[51] While controversy at CUNY schools in the 1960s predominantly reflected the implementation of open admissions, responding to African-American and Puerto Rican demands, their students still engaged with the city’s counterculture. Class, ethnicity and gender shaped the idiosyncrasies of these institutions, too. Barnard College was all female, and neighbouring ivy-league Columbia all male, NYU’s students particularly affluent, Fordham a Jesuit (and thus Catholic) institution. Brooklyn College and City College (CCNY) with high Jewish enrolment, yet this was changing in the 1960s; by the end of the 1960s African-Americans and Latinos a nascent presence at Hunter College.[52]

Distinguishing counterculture from the New Left, youth culture, and other liberation movements is essential. Confident deviance stands firm in demarcating the counterculture as a behaviour rather than an agenda, welcoming a self-consciously unconventional conduct in leisure, socialising, and political activism. For this reason, the hybrid countercultural-come-political activism visible on university campuses by the late 1960s falls under the remit of countercultural historiography.

Revealing much about New York City, this chapter illuminates that countercultural university campuses could act as platforms for local protest. Outlining residential and leisure patterns of students makes it clear why certain students engaged with counterculturalbehaviour, passing others by. It also has relevance for New York’s declining status as an academic centre in the 1970s.[53] The failure of New York’s universities to reconcile with the force of the counterculture constituted part of the reason as to why Columbia and NYU fell into reputational and financial difficulty in the early 1970s.[54]

Additionally, it reveals much of counterculture, exposing the early sixties on university campuses as dominated by fashion and fads, the later years dominated by politics. It is through looking at universities of the city that ‘1968’ as being, in Mark Kurlansky’s words, the ‘year that rocked the world’ and that the counterculture pivoted, is made redundant.[55] The fulcrum, instead, was the decline of the anti-war movement, and emergence of distinctive liberation movements, which respectively sapped countercultural energies away from college campuses, and made them less fitting platforms for protest.

Divisions on Campuses

The ardently political New Left had a complicated rapport with counterculture, and towards the hippie wing, their stance was ‘one marked by ambivalence and confusion, but also by self-consciousness and strategic thought.’[56] A binary of ‘us and them,’ however, sits uneasily with a counterculture that was defined by behaviour rather than membership of an organisation. The New Left operated within formal structures, most famously the Student Democrat Society (SDS), which was a political organisation with chapters set up on various colleges nationwide. Comparatively speaking, informal association with counterculture was possible through clothing and hair, and acting in a way that affiliated with the aura of confident deviance.

Absent in mainstream media, NYU’s archives illustrate counterculture’s existence beyond newspaper headlines.[57] NYU’s eclectic mix of student organisations jostled for the limelight. Tensions and collaborations existed among factions of confident deviance at university campuses.[58]

Fig-5[59]

Explicitly wacky and inventive protest employed by the Transcendental Students marked a divergence with traditional forms of demonstration – such as petitioning and picketing, sit-ins, and teach-ins – that had become standard student behaviour. [60] Common to many campus groups of New York’s universities up until the end of the 1960s was the goal of ‘liberation’ – ideas that would play ideologically and rhetorically into the more formally organised liberation movements of the early 1970s.

An NYU graduate student described the Transcendental Students’ Freak In as a ‘radical political event to show people how to use this space in a way that was to be liberated.’[61] It was the process of acting out however they wanted that members of their group strove to attain ‘liberation through happiness.’[62] It is this juncture which illustrates the most glaring difficulty that historians of the counterculture face, for historians convey arguments with language and reasoning that, at their strongest, countercultures rejected.[63] Peter Braunstein noted that ‘the countercultural mode revelled in tangents, metaphors, unresolved contradictions, conscious ruptures of logic and reason [and that] it was expressly anti-linear, anti-teleological,’ making its representation testing.[64] This study avoids getting bogged down in the semantics of counterculture, instead engaging with an understanding of the counterculture as seen by the mainstream and through conventional discourse – appropriately surmised as one that fell into the category of confident deviance.[65]

NYU’s SDS chapter staged a guerrilla theatre performance at the Loeb Student Centre the same day as the ‘Freak In’ on March 6th, 1969.[66] If the genre could be best described as controversial theatre in public spaces, the publicity stunt sought to broadcast student protest in a novel and eye-catching way. What this illustrates more than anything else is that there were simultaneous expressions of counterculture at New York’s universities operating independently of each other. It also serves to break down assumptions that the New Left was not itself artistically creative – countercultural in their confidence and novelty. At NYU, groups competed to be recognized as the authentic voice of personal liberation.[67]

SDS attempts to affiliate with the Transcendental Students over March 1969 are symptomatic of the inter-relationship operating between factions and groups. The process of learning, imitating, affiliating but also disagreeing, created a competitive dynamic that fuelled counterculture on college campuses. An SDS-TS sponsored ‘Freak Out; held out on the 18th of March that same year degenerated as police arrived, a student was arrested, and the SDS crowd moved to occupy Vanderbilt Hall, protesting and chanting ‘Lynch the Pigs! Today’s pig is tomorrow’s bacon!’[68] It was unlike the Transcendental Students to be so confrontational, and one member sourly left the scene, noting that the SDS was overtly political and that their members seemed to be ‘on an ego trip.’[69] The Transcendental Students disbanded in 1970 and other groups rose to fill the void.[70] The regenerative quality of student groups and organisations at NYU underscores the regenerative quality of campus counterculture – iterations of which created novel deviant displays over the course of the 1960s.

Other groups were hostile to NYU’s counterculture. The Society for Individualism penned an open letter to the NYU’s President in October 1968 addressing concerns from a section of students that demonstrations and strikes of other groups have led to the ‘violation’ of their right to attend classes.[71] Noting that ‘if campus buildings should be occupied or if students should be physically prevented from entering the buildings, the duty will devolve upon you, as President, to maintain free access to classes for every student who chooses to exercise his right to them,’ the letter shows that there was a planned mobilisation amongst the student body against other student demonstrations.[72] By the beginning of the 1970s, student union election voting patterns revealed hostility towards radical student groups, indicating a university population tiring and unamused by counterculture.[73]

NYU student behaviour was regular for the city. Analysis by the New York Post estimated that in 1965, citywide, the number of student activists was ‘small, and the hard-core is probably well under 5 per cent of the total student population.’[74] They estimated that at CCNY and Columbia, 10% of students engaged in radical activism, ‘with as many as 25 to 35 percent more sympathetic to many of its causes,’ yet over half ambivalent or negative. [75] New York Post continued, ‘at NYU, Hunter and Queens, about 3-4 per cent, at Brooklyn, even less; at Fordham, St. John’s and Manhattan [all Catholic independent], the number of leftist students can be counted on two hands.’[76] Similar patterns of solidarity, cooperation and hostility emerged. Young Americans for Freedom, Students for a Free Campus, and athletes emerged as hostile to ’68 protests at Columbia.[77] At Queens, students distributed flyers in the wake of 1969 anti-war protests, calling on students to go to seminars.[78] Radical student activists were never the majority, but their voices were ‘being heard and affecting their contemporaries.’[79]

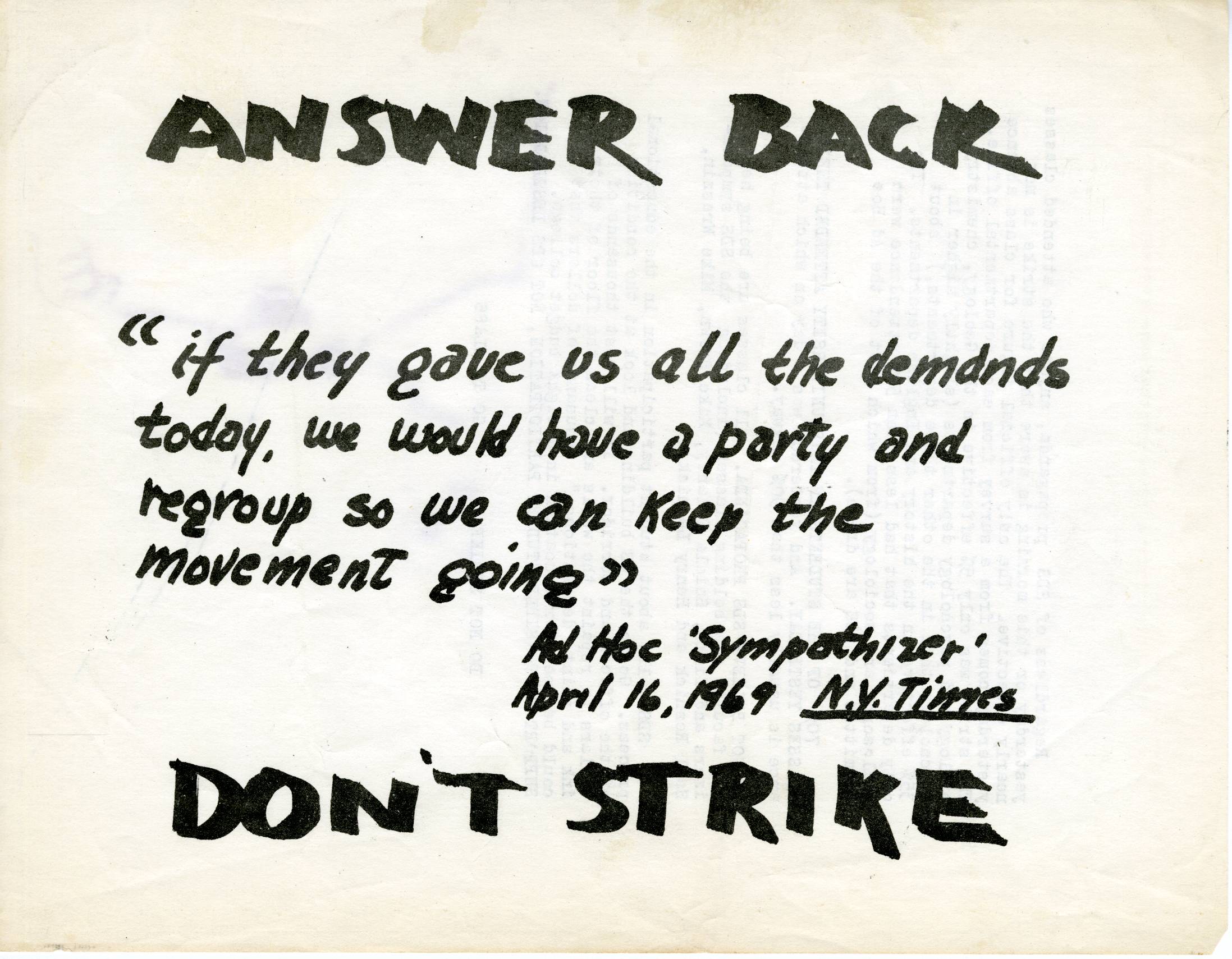

Fig-6[80]

Universities and the Neighbourhood

University counterculture did not happen in a geographical vacuum. At times, universities became platforms for local protest. The SDS’ guerrilla theatre performance (the same day as the Freak Out) saw seventy ‘hippies’ belonging to the Motherfuckers – a Lower East Side city organisation – storm into the building, disrupt the performance, destroy furniture, punch reporters and bystanders, and confront guards.[81] NYU’s Washington Square Campus neighboured Greenwich Village and the Lower East Side. University counterculture was also city counterculture, and neighbourhood grievances were important in shaping the counterculture on the university campus.[82]

Part of this came from the unplanned and spontaneous countercultural trait. The New Left was criticised for this very issue. Carl Davidson, Vice President of the SDS in the mid-1960s fully accepted this point, yet claimed that it was an ‘advantage.’ [83] Writing that ‘to my mind, the great strength of the New Left has been its unconscious adherence to Marx’s favourite motto – doubt everything,’ Davidson’s comments conjure up that radical students from the New Left tradition ‘had its deepest roots in people’s day-to-day life activity.’[84] Neighbourhood grievances played an important part in influencing the spontaneous reactionary politics.

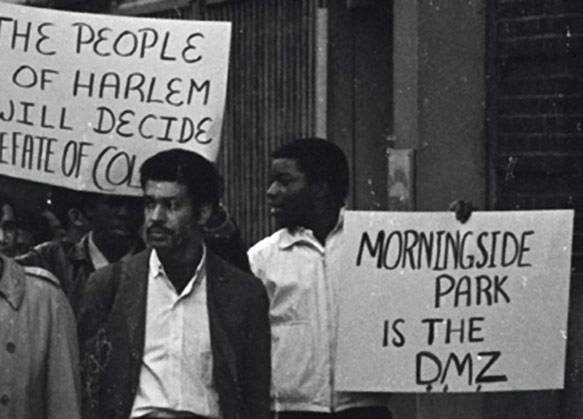

Official statements from Columbia University reflect that the problems of 1968 were local. Protests erupted after a build-up of issues that particularly affected African-Americans – students and neighbouring residents – in Morningside Heights and Harlem. Whether by implicitly supporting the Vietnam War by funding the Institute for Defense Analysis, or through viewing expansion plans of 1950s and 1960s as infringing on African-American and Puerto Rican neighbourhoods, the uprising was articulated as an affront to a racist institution.[85] A letter released mid-way through protest by the university administration addressed student concerns, promising to release full statements on ‘the Urban Renewal Project, relocation policy, renovation of the residence halls, military recruitment, a black studies program, religious councillors, principles governing university construction outside the quadrangle, and electoral procedures for the University Senate.’[86]

Fig-7[87]

In the 1960s, NYU was split between a campus at Washington Square Park in downtown New York, and a campus in the Bronx, and student experiences differed at each. A student newspaper at the Bronx campus noted in an article that ‘the whole atmosphere in a major metropolitan area is somewhat more tolerant than in a suburban section’ of the city.[88] It is no surprise that the close proximity of the NYU’s Washington Square Campus to the centre of the gay movement in Greenwich Village influenced the university’s countercultural activism. Gay Liberation activists from the Village flocked to the assistance of NYU’s Gay Student Liberation group when they were occupying a room in the sub-cellar of Weinstein residence hall, following the cancellation by the university of a dance that the student group was planning on holding in the fall of 1970.[89]

Staff became embroiled in the turmoil of the 1960s too. An NYU employee, Jim Clifford, publically complained to the university about its association and running of Bellevue Hospital – a hospital which had treated homosexuality with electric shock therapies. He noted that ‘the Village is the largest gay ghetto in the world, and the university, as a guest in this community, should take its responsibility to the community seriously.’[90] The flourishing of independent liberation movements in the 1970s in New York City, particularly for Gay Liberation, debased the necessity of campus-centric confident deviance, as the campus became adjunct to avant-garde city politics.[91] Jim Clifford and the group, Gay Student Liberation, were joined by other groups such as the Gay Liberation Front, Street Transvestites of Sheridan Square, in demonstrations at NYU.[92] Foreboding of the growing external liberation groups that undermined campus radicalism, the Washington Square Journal made references to Women’s Liberation groups that had kick-started a debate over the mini-skirt in the New York Times, and signalled that by 1970, student organisations were becoming redundant. The student journalist noted that student-led activism was dying, for ‘what is relevant on campus is not always relevant in the real world.’[93]

The university structure was important in enabling and averting student collaboration. A Brooklyn College student noted that ‘Brooklyn College, like all CUNY schools, was a commuter school. […] there were no student dormitories, every student lived at home that I knew of with their parents, and this continually led to a complaint about a lack of community at the school.’ [94] Newsweek might have noted that students had ‘world enough and time, and as a result, no issue is too cosmic or too parochial to launch a student power demonstration,’ but the reality was that for students at CUNY schools, living at home, time on campus was more limited.[95] A rare sit-in at Queens College for four days and night from March 27th, 1969 was perceived by the SDS as an event that ‘created a real community on campus’ for the first time.[96] Otherwise, at best, student radical groups at CUNY schools would organise around mealtimes. At CCNY, in Hamilton Heights, ‘students chose booths in the school cafeteria according to their political views.’[97]

Widespread protests at New York’s universities following the May 1970 Kent State shootings illustrate the universality of countercultural political protest organised around anti-war activism. Student classes were cancelled, and at Brooklyn College, among others, classes never continued for the rest of the year.[98] But they also demonstrate the effect of campus demonstration on the local neighbourhood. A diary of a Brooklyn College student noted that ‘high schools situated near college campuses were the most heavily affected,’ as 1,500 Brooklyn students picketed outside nearby Midwood High School. [99] The same student noted that his ‘Dad’s Bronx Store on Fordham Road was closed due to the Fordham demonstrations’ against the war.[100]

Boundaries demarcating universities from their neighbourhoods were permeable. Everyday countercultural campus life was affected by the neighbourhood, but campus life also had an effect on the neighbourhood. But this process of exchange also mattered for the university network, enabling students to offer support to activism and dissent at other campuses around the city.

University Networks of Solidarity

‘…In large cities, radical students can shuttle from one campus to another. At a recent demonstration at City College, less than half of the 174 demonstrators arrested were CCNY students…’[101]

Links between universities were vital in forging the nation of confident deviance that blossomed in the 1960s. It is worth observing that the city-level countercultural network was different from the formal national network of organisations such as SDS. The city network lent itself to more spontaneous and informal (countercultural) support, and it was through this web that CUNY students most visibly engaged with New York’s counterculture. Untapped archives from Columbia, NYU and Queens show that the interrelationship between colleges and universities across the city were, on the whole, collaborative and imitative – the solidarity between university students of different campuses stifled points of contention found among students of the same campus.

Collaborative efforts across the city mirrored initial attempts at collaboration that existed on the campus anyway. An internal memo at Columbia in 1969 feared that students from around the city would be joining student protests that year. It noted that the ‘SDS has been active for some months in certain New York high schools and has announced that several hundred students will come to the campus on April 21.’[102] The national links, it seemed, could have more local and nuanced connections too. In the anti-war demonstrations at NYU in May 1970, a group of 500 students from Queens were diverted from a Washington Square protest by an NYU student who called them over, and they all descended on NYU’s Kimball Hall.[103] A student noted in his diary that ‘about 1,500 students from Brooklyn Technical High School went to the Long Island University auditorium on the downtown Brooklyn Campus, at the invitation of L.I.U students’ in the same wave of anti-war protests that shook the city.[104] Demonstrations by 3,000 students at Fordham on an afternoon in the fall of 1969 were supplemented in the evening by a ‘candlelight vigil at Fordham’s Rose Hill campus’ by ‘7,500 students from Fordham, Bronx Community College, and Hunter College’s Bronx campus.’[105] Solidarity in confident deviance was a hallmark of the international counterculture, and it was particularly strong in New York’s university network.

Countercultural students relished mimicking and mirroring student activism on other campuses.[106] A student-run guerrilla theatre performance in October 1967 at Brooklyn College against army recruiters escalated into violence, necessitating police intervention.[107] Concurrent anti-war student groups at NYU riled up support for their allies in Brooklyn, threatening similar action, leading the NYU administration to issue a memorandum that they would have to ‘indefinitely postpone’ the recruitment visit by the airforce that was planned for later that year.[108] So too, the strategy of putting on a ‘counter-commencement’ protest in May 1968 at Columbia was replicated at Queens in 1969.[109]

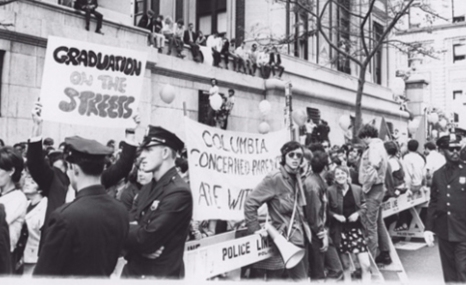

Fig-8.[110]

Late 1960s political protests on New York’s campuses were magnets for countercultural behaviour – it being commonplace for students to highjack the protests ‘to further their own causes.’ [111] Many more than the 300-odd registered members of Columbia’s SDS and Afro-American Society protested in 1968. Other students rose to the occasion, and alongside the protestors who were rifling through the President’s office to engage the political wing of protests and to pressure Columbia to change, there were those who ‘drank his sherry’ and others who got married.[112] The band, the Grateful Dead, came over from the west coast of the United States to attend the protest, smuggling through the crowds to get into the midst of the Columbia student strike for a gig on the Low Library steps.’ [113] So too, the San Francisco Mime Troupe made the long journey, using the demonstration as an opportunity to perform their trademark political satire.

Fig-9[114]

Campus newspapers also indicate that students were aware of how their experiences contrasted with other universities. A comparative piece between State University of New York at Stony Brook (out of the city on Long Island) and NYU at the Heights Campus, over the issue of LSD and drugs, written in NYU’s paper signalled this awareness. As the article wrote, ‘the situation here is different from that at Stony Brook [… for] in the first place, the New York City police force is more sophisticated than the Suffolk County force.’[115] All too aware of similar problems and points of grievance, these issues galvanised countercultural connections and admiration between students.

Fashions and Fads

For every student that participated in these public acts and demonstrations, there were those whose fashion trends were subtly shaped and those whose classes were cancelled. It was not always necessary to be part of SDS, or another fringe group, to be involved with countercultural trends. A less political counterculture affected the early-1960s behaviour and fashion of many New Yorkers – long hair a stereotypical characteristic.[116]

Culturally, through fashion trends and other fads, universities of the city retained distinctive countercultural characteristics. New York Post’s exposé on student campuses in 1965 revealed that ‘at Columbia this winter, the peaked Lenin hat is in. For Barnard girls, it’s the shepherdess look – long hair and Mexican regalia. Brooklyn boys wear rubber type parkas. With recent dress restrictions lifted, both boys and girls are in dungarees, with bell bottoms on the girls.’[117] At ‘Hunter, they wear tight fitting jeans; at NYU uptown, it’s the plaid wool heavy overshirt. This year’s look among student hipsters is steel rimmed glasses.’[118] Telling of the spread of political messages through the university networks in the early 1960s was the ascendancy of activists’ badges, which were ‘widely worn on the campus.’[119] But a nod to characteristic early and mid-1960s rejection of the political counterculture, the trend at Queens was ‘a button that said, ‘Button.’’[120] A Queens student said, ‘It’s quite a joke… It’s like calling an ace an ace… It’s funny because it’s absurd.’ [121] At Columbia, buttons read ‘Never.’ At CCNY they read ‘Gone Are the Days.’[122] Fashion and hair trends embodied the spirit of confident deviance – subverting gender norms in clothing and hair, riling up older generations, and taking digs at fellow students too.

Fig-10.[123]

But the generaltrend on university campuses worked in tandem with city trends. In Sean Deveney’s work, Fun City, he references, how by the end of the 1960s, New York convenience stores were filling up with fake moustaches and the like, so that students could, in effect, dip in and out of countercultural fads and trends.[124] One Brooklyn College student claimed that he liked to be presentable at school during the day, but that he was in a rock band called the Brooklyn Dodgers by night. Using the fake moustaches, he justified using them by claiming that ‘I wouldn’t be hired if I looked clean-cut and normal.’[125]

Hair was a symbol by which people could identify, and be identified, with the counterculture. This was apparent from as early as 1964 when the Beatles came to the city. [126] Danny Landau, a Brooklyn College student, admired the Beatles’ deviance from traditional norms, and noted ‘they’re different, they’re just so different. I mean, all that hair. American singers are soooo [sic] clean cut.’[127] Hair took conscious effort to cut, and thus was a symbol of particular perseverance to the cause of deviance. By the end of the decade, a Columbia student, James Kunen, embraced the ‘bad vibrations’ that his long hair signified.[128] He said ‘I say great. I want the cops to sneer and the old ladies swear and the businessmen worry. I want everyone to see me and say: “There goes an enemy of the state,” because that’s where I’m at, as we say in the Revolution game.’[129]Hair became symbolic of counterculture and hippies. Larry Merchant, a sports commentator during the 1960s noted, ‘a young person […] who didn’t take a haircut every three weeks, was automatically hooked up with Allen Ginsberg, Haight-Asbury and dirty feet.’ [130] But it also became a way of working out who was hip from who was ‘square’ (phoney-hipster), by the very nature of the fact that it was nearly impossible to fake long hair.[131] The New Yorker stereotyped visitors at Woodstock Festival in 1969 by their hair length, treating it as indicative of their affinity to the festival’s countercultural message. A reporter described a University of Chicago student as having ‘hair neither very short nor very long’ and who apathetically noted ‘I went rather casually partly because I wanted to hear the music, and partly because I knew, by word of mouth, that there would be a tremendous mass of people my age, and I wanted to be part of it.’[132]

A narrow look at protest and politics takes away from the strong impact that counterculture’s early years had on leisure and fashion. By April 1968, 75%, of NYU students were estimated to have tried marijuana – a total numbering 30,000.[133] Seeing confident deviance as a sliding scale, there was a large cohort of college students who affiliated with the deviant nation at large, unfamiliar to radical politics. The university campus incubated these very trends.

Unwitting Interactions – Alumni, Parents, and other Students

But if affecting hairstyle and fashion trends were a choice, there were many unintentional encounters with counterculture that the universities facilitated. It would be trite to solely point out that demonstrations and ‘happenings’ affected the ability of students to go to classes, for there were other more nuanced ways in which people were embroiled in the spill-over effects of the counterculture. In April 1968, members of the Columbia basketball team were swept up in student protests whilst practising in Morningside park, for ‘members of the team were roughed up by the police in Morningside Park during a general ‘sweep’ of the area to remove students protesting in the building of the gym.’[134] Being swept into the issue by physical means, the team complained to the university authorities, angry that the predominantly-black team was stopped and questioned without reason, and that they were assumed to be protestors. With the University rejecting the team’s wish to ‘speak of the park incident at the awards dinner’ they refused to attend, and ‘instead, picketed outside the event in a driving rainstorm.’[135]

Looking at the at Columbia University’s pro-homosexual Student Homophile League offers a different way in which non-subscribers off the university campus interacted with confident deviance. It was on the 3rd April 1967, that its existence was slapped on the front page of the New York Times.[136] Established in October 1966, the organization had received official recognition from Columbia as a student organisation – it was seen as an organisation which poked at the questions and assumptions around homosexuality, rather than one that defined itself as a homosexual organisation. Yet it sought publicity and attention, and released a press statement to the New York Times which precipitated a crisis within the administration.

Fig-11[137]

A written record of a telephone conversation reflected the fact that confident deviance on the campus affected networks beyond the city – it affected alumni and parents too, and bears extended quotation here:

‘Mr Robert McCullen, who is President of the Bergen County Columbia Alumni Club, (College ’43, Law School ’50), telephoned about the TIMES article this morning re. homosexuals club. Mr McCullen is extremely agitated by this publicity, not only the moral aspect, but the legal – homosexual acts are subject to fines and imprisonment in New York State, maximum punishment being life imprisonment. Mr. McCullen is a practicing attorney in New York City and said we should talk with Frank Hogan … crime against sodomy. [As an active recruiter for Columbia] he and all other alumni are now going to be the laughing stock of every prospective Columbia student, prospective donors.’[138]

Letters came flooding in from alumni and parents, who were concerned with the impact that the event would have on the university environment and the reputation.[139] Recruiters noted that they would have difficulty in persuading children of friends to attend the university, donors threatened to withhold financial assistance, and parents expressed concern that the university was promoting deviance.[140] The organisation had an impact and an influence that went beyond Columbia’s residential populace. It affected the conversations of the readers of the New York Times, it interacted with other organisations around the city, alumni, parents and religious institutions, too.

The impact that this behaviour would have more generally on the fortunes of the private universities is of note. Eric Foner – an undergraduate at Columbia University from ’63 and later PhD student ‘69 – noted that ‘Columbia’s fortunes rise and fall with New York City.’[141] The behaviour on campuses during the 1960s, but particularly the heavily publicised events, was one of the reasons that the university fell into dire financial conditions. Foner remembers that ‘the university went into a financial tailspin in the 70’s because alumni were so appalled by these events.’[142] So too, NYU would descend into financial difficulties in the 1970s.[143]

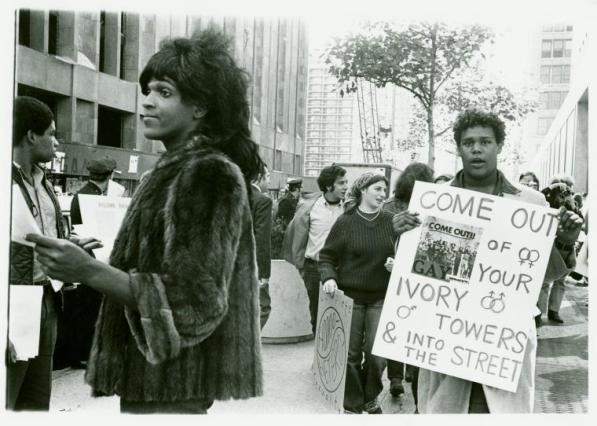

Deviant hairstyles and deviant fashion were hallmarks of mid-1960s university life, and counterculture fused with a radical student political agenda to form a distinctive hybrid in the later part of the decade. This chapter, resisting cartoon versions of 1968, has outlined everyday experiences of countercultural life on New York’s university campuses, broadly speaking, from 1964 to 1970. But counterculture became less prominent on campuses once structured liberation groups had emerged in the 1970s. Emblematic of things to come, Marsha P. Johnson, a prominent New York gay liberation activist, marched outside NYU in September 1970 with a placard that read, ‘come out of your ivory towers & into the street.’[144]

Fig-12.[145]

Chapter II: Race and Ethnicity

The Village Voice’scoverage of a ‘Happening’ in December 1968 reflected that New York was a cosmopolitan city. Three-hundred NYU students were hurling Italian, French and Wonder Bread (American-branded sliced bread) across the Eisner Auditorium in a food fight. ‘“Love bread, not war bread” shouted someone from the gallery who had just been clobbered with a ravaged loaf of Jewish pumpernickel.’[146] Appreciating the work of Gary Gerstle, which has argued for the ‘centrality of race to American politics and society,’ this chapter attempts to foreground race and ethnicity as aspects of the counterculture which have not been fully explored in existing accounts.[147]

On first glance at New York City, it becomes apparent that it has garnered a reputation as a Jewish metropolis. Woody Allen famously remarked in the film Annie Hall (1977), ‘don’t you see the rest of the country looks upon New York like we’re left-wing, communist, Jewish, homosexual, pornographers? I think of us that way sometimes and I live here.’[148] Jews constituted 25% of the city population for the majority of the twentieth-century, while only 2.5% nationally.[149] Nathan Glazer noted that ‘in culture, the distinctive role of Jews has been as advocates of the avant-garde, whatever that avant-garde happened to be at any time.’[150] But little work has been done to interrogate to what extent Jewishness intersected with the counterculture of the 1960s and 70s – particularly surprising given a Rabbi’s comment to the New York Times in 1967 that ‘an awful lot of hippies are Jewish.’[151]

Joshua Zeitz has noted how hard it can be to navigate the world of statistics to achieve any ‘accurate’ demographic representation for New York, but he concluded that in 1960 Italians comprised roughly 17%, Irish 10%, and Jews 27% of its population.[152] These groups forged distinctive ‘white ethnic’ identities within post-war New York City, and he has argued that ethnicity (defined as ‘the intersection between religion, national origins, and class’[153]) played a ‘meaningful force’ in post-war America.[154]

The increase in African-American and Puerto Ricans residents over the 1950s and 60s was consequential for the city’s counterculture too, [155] comprising 14% and 8% of the population, respectively, by 1960.[156]An article in New York Post claimed that during the decade, ‘black and white liberals split along racial lines, and two cries were heard: ‘Black Power!’ and ‘Flower Power.’[157] Yet with a reconceptualization of the counterculture towards a behaviour and away from just ‘hippies,’ this chapter recovers attempts at racial integration within this nation of confident deviance.[158] These first two sections reveal much of the nature of counterculture; first, Jewishness and the counterculture, second, whiteness and the counterculture.[159]

The final section illuminates, comparatively speaking, more about New York. Illustrating the evolving and sensitive relationships that unwitting neighbours (often recent immigrants) in downtown New York had with hippies and college dropouts, it also illuminates the eastward move of New York’s traditional countercultural epicentre.

‘Jewishness’and the Counterculture

‘…commune is not far from kibbutz…’[160]

Fig-13[161]

It was in the middle of the Columbia 1968 demonstrations that Mark Rudd, who was leader of Columbia SDS and of the student uprising, told journalists that his Jewish parents were ‘100% behind him.’[162] His parents drove into Manhattan from New Jersey, bringing a homemade and not kosher, ‘veal parmigiana dinner, which the family ate in their parked car on Amsterdam Avenue.’[163] The perception that ‘an awful lot of hippies [were] Jewish’[164] correlated with surveys that showed that students at Columbia from Jewish homes were disproportionately represented in the university demonstrations.[165] Despite historical trends of anti-Semitic admissions procedures and faculty recruitment at Columbia, by the 1960s it had the highest enrolment of Jewish students in the Ivy League – a figure of 45%.[166] Joshua Zeitz noted that ‘it did not occur to many bystanders or participants that Jews played an unusually large role’ in Columbia’s demonstrations.[167] For historians of the counterculture, this is the same.[168]

Jewish New Yorkers’ proclivity towards dissent is best illustrated comparatively alongside traditional Catholic commitment to law and order (yet it is important not to imbibe traditional caricatures.)[169] Popular accounts of American Jewish traditions by Jews cite dissent, debate and agitation as age-old habits of the faith.[170] But this did not stop at the liturgical level. Over the course of the twentieth-century in New York City, patterns of self-employment amongst Jewish communities contrasted with salaried jobs amongst (Irish and Italian) Catholics in New York in the early twentieth-century. While Jewish families imbibed an individualism enabled by the workplace, Catholic families imbibed a respect for authority out of necessity for job security.[171] In this light, ‘Jewishness’ dovetailed with the nation of confident deviance.

The Jewish constituency within the nation of confident deviance did not go unnoticed by New York’s Mayor, John Lindsay, in his re-election campaign in November 1969. Lindsay’s adviser, Richard Aurelio, noted that ‘the whole thesis of our campaign was to try to appeal to the Jewish consciousness in terms of the minorities.’[172] Illustrative of Jewish hostility towards the war was the case of John Ruskay – a Long Island student – who sought Conscientious Objector status in the draft, arguing that it aligned with Jewish beliefs.[173] Aware that Jewish voters were often opposed to American involvement in Vietnam, Lindsay approached anti-war protestors at the heart of New York’s counterculture in Greenwich Village on October 15th, 1969. Allying with Jewish credence that dissent was part of their civic duty, Lindsay noted that the method of protest in the Moratorium to End the War in Vietnam was ‘the highest form of patriotism,’ and that ‘those that charge this [as] unpatriotic do not know the history of their own nation and they do not understand that our greatness comes from the right to speak out.’[174] The Jewish vote would prove crucial for his eventual re-election, with Lindsay winning an ‘impressive 43% of Jewish votes.’[175]

Fig-14[176]

Fears of high Jewish representation in student protests precipitated anxiety within the American Jewish Committee and the wider American Jewry.[177] Nathan Glazer, a Jewish Marxist-turned-anti-Communist, feared that ‘Jews would be held responsible for the loss of the Vietnam war.’[178] The sociologists Geoffrey Simmon and Grafton Trout, while researching hippies on 1960s college campuses, noted that their study reflected ‘a disproportionate number of Jewish students, yet only two negroes.’[179] Yet despite these findings, a Rabbi reflected on rows between African-American and Puerto Rican groups and hippies in Greenwich Village in 1967 that he ‘didn’t think anti-Semitism was a relevant factor in present tensions.’[180] With anti-Semitism unfashionable, explicit correlations between Jewishness and the problems of the counterculture seemed to be rare within New York City.

Elsewhere in the United States, Jews – New York’s Jews – were seen to be central to campus turmoil of the 1960s. In March 1967, the board of the University of Wisconsin-Madison reduced out of state enrolment to 15%, decreasing the number of Jewish students by 65% by 1970. Original attempts made to curtail student numbers from ten heavily Jewish states, based on beliefs that ‘Jewish activists were responsible for campus unrest and for acts of civil disobedience’ were rejected.[181] More relevant to the city’s Jewish identity as a hotbed of countercultural activity, a board member allegedly said to a group of students, ‘it is the damned New York Jews we want to keep out, not Gentile out-of-state students.’[182]

Coded correlations, however, were more prominent within the city.[183] Vincent Cannato noted that at Columbia the conservative and anti-protest group Young Americans for Freedom (YAF) illustrated YAF and SDS differences by saying ‘We’re Staten Island. They’re Scarsdale.’[184] It was not just a class comparison (Staten Island was predominantly working class, Scarsdale professional), but also one of ethnicity. Scarsdale was predominantly Jewish, Staten Island Catholic. The development of tensions between New York’s Jews and African Americans over the course of the 1960s, too, did not develop into explicit critiques of a Jewishness of the counterculture. Instead it was subsumed into the critique of whiteness.[185]

That Jews made significant contributions to confident deviance in New York is evident. But the inclusion of Jewishness in the counterculture means that historians have to review arguments that suggest it was a rejection of parents, and a rejection of authority.[186] For Jews, counterculture, or the nation of confident deviance, was not as much a rejection of their upbringing, more, as Zeitz has argued, ‘following to its logical conclusion the very instruction manual on which they had been raised.’[187] As the counterculture snowballed in the 1960s, it appealed to those who saw it in line with Jewish traditions as much as it appealed to those who were running away from and rejecting parents. The counterculture was, thus, a coalition of those who, for different reasons, wished to act deviantly and with confidence.

Yet this chapter does not wish to suggest that all Jews were sympathetic to the counterculture. Milton Himmelfarb, a well-known contributor to Commentary, an American Jewish magazine, ‘concluded that radical Jews were the most “anti-Jewish”[188] Jews ever witnessed in history.’[189] So too the Hasidic Jewish community on the Lower East Side set up a ‘Tefillin-Mobile’ truck in Washington Square Park in May 1968, seeking to explain Jewish heritage to male Jews in the area.[190] Rabbi Samuel Schrage, helping out, said ‘young men, especially Jewish young men, are searching for mystic experience like LSD and pot, and gurus and maharishis. We can give them mysticism.’[191] There were also those who were indifferent. But neither does it wish to suggest that all in the counterculture were Jewish. Whilst Jewishness was an important constituent of confident deviance, ‘they were joined by millions of Catholic and Protestant youth who developed a similar, deep-seated suspicion of powerful institutions.’[192]

‘Whiteness’ and the Counterculture

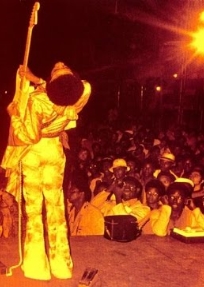

Fig-15[193]

Timothy Leary famously coined a phrase of the counterculture, ‘turn on, tune in, drop out,’ at a Be-In in California in 1967.[194] The first time the phrase was articulated, it was accompanied by a follow-up clause – ‘I mean drop out of high school, drop out of college, drop out of graduate school.’[195] But you had to be in it to be able to ‘drop out.’ For ethnic minorities and working-class Americans, this countercultural epitaph was at best, irrelevant, and at worst, derisive, of their aspirations. ‘Whiteness’ applied to the counterculture invokes ideas of exclusivity through both racial andclass categories. While agreeing that counterculture was affluent, this chapter questions the racial exclusivity of New York’s counterculture.

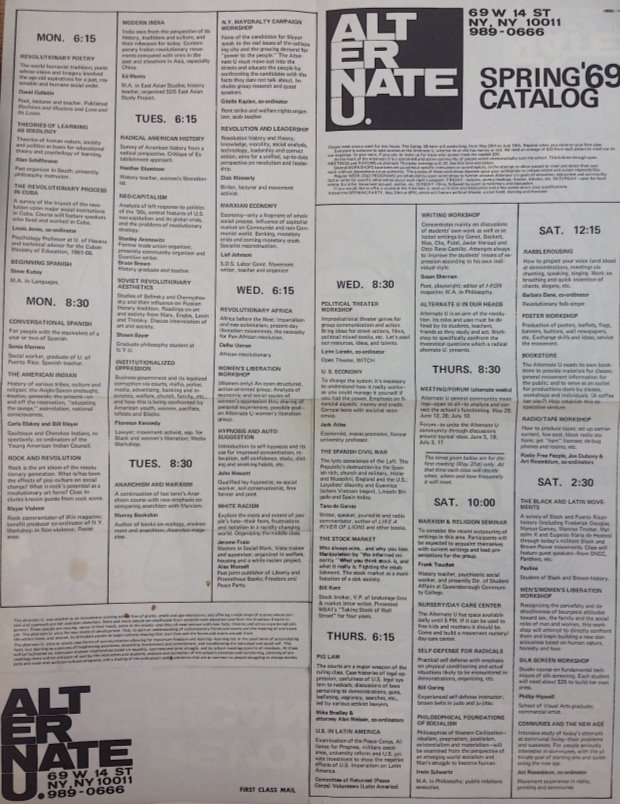

New York’s counterculture professed a racial and ethnic inclusivity that has been lost in a history that sorted ‘Black Power’ and ‘Flower Power’ into different silos. Columbia’s SDS in 1968 galvanised student appetite for revolution around issues of racism.[196] But it was the case away from high-profile incidents, too. New York’s restless students, in the summer of 1964, went in huge numbers to help SNCC with voter registration drives in southern states.[197] In publishing an open letter to academics of the city in 1969, Tom Wodetzki in founding the Alternate University in Greenwich Village, noted its necessity, for it was providing new courses for ‘the alienated youth-hippie element, the growing number of education drop-outs […] who know they are not getting the whole story.’[198] The Alternate University’s Spring 1969 course list included Street Spanish for Beginners, and Racism and the Rise of the Industrial North.[199] With the aim of educating to ‘combat elitism, sexism, racism, liberalism – and fear,’ New York’s counterculture was, at first glance, seemingly racially and ethnically inclusive.[200]

Fig-16[201]

To suggest that the counterculture was exclusively driven by ‘white’ groups whitewashes ethnic minority efforts to engage with counterculture’s ‘productive wing’.[202] The Real Great Society, established in 1964 by two former Puerto Rican gang leaders, secured sponsorship worth $40,000 by 1967, and provided resources for people from ‘diverse educational, social and economic backgrounds’ to engage in creative arts.[203] In June 1967, it established a University of the Streets (predating the Alternate University) creating an organisation that rebutted formal structures, signalling that it ‘will have neither faculty nor students and thus no separation of the type that normally exists in educational institutions.’[204]

Fig-17[205]

Counterculture’s exclusivity came originally from financial barriers more so than race. Detroit’s underground newspaper, Fifth Estate, established in 1965, was not a lone-wolf in soiling a segment of the counterculture as ‘affluent hippies’ that ‘have lots of the world’s money lurking somewhere in their father’s pocket.’[206] Critical of the fact that ‘hippies shudder to identify with the working classes, the underprivileged or the attitudes of the under-developed nations,’ the anarchist publication touched a nerve with many who questioned how economically (and by proxy racially) inclusive hippies really were.[207] A memo from the Bulletin of International Socialism echoed these sentiments, noting that ‘defeatism and dreams’ were not an option for the economically marginalised. [208] Free love and flowers could not pay the rent and feed mouths.

But it was not just the availability of money, but also the desire to reject extreme wealth and affluence, that meant that class (and race) were distinguishing factors. The New York Times dryly commented that ‘the Village scene has no more than a handful of Negro teeny-boppers, largely because Negro youths apparently don’t need such a scene to declare their freedom from and hostility to the Establishment.’ [209] Hippy rejection of affluence and privilege did little to ring in the ears of marginalised ethnic minority communities. When Jimi Hendrix addressed the Black Associated Press in Harlem months after his appearance at Woodstock Festival, he noted that ‘a lot of the kids in the ghetto, or whatever you want to call it, you know, don’t have the money to travel across the country, to see these different festivals.’[210] Token African-American involvement at counterculture’s forefront, such as Jimi Hendrix headlining Woodstock Festival, sullies the reality of the extent to which African-Americans were able to participate in the counterculture.[211] The lack of anywhere near proportionate representation of African-Americans in aspects such as hippies and student rebels gives it an exclusive, affluent, and white, characteristic. Parochial protest did little to appeal to African-Americans, and it is not surprising that energies

went into concurrent black nationalism rather than picnics and Love-Ins.[212]

went into concurrent black nationalism rather than picnics and Love-Ins.[212]

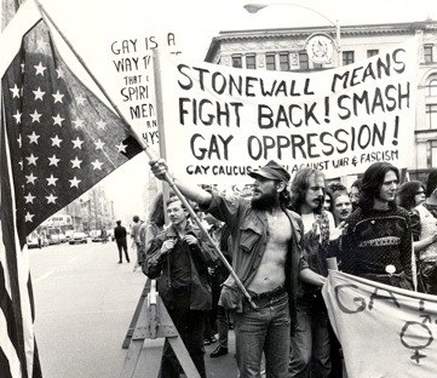

Issues of race were imprinted in counterculture’s legacy. A Stonewall Inn barman in the late 1960s noted that the customer base consisted of ‘a few blacks, but mostly white and a few Hispanics’ for ethnic minorities ‘were more likely to hang out by the pier, or at Ty’s.’[215] He noted that segregation was evident inside, as ‘the ones that were dancing on the floor were mostly the black and Spanish. The white ones would be at the bar just getting drunk.’[216] Derogatory terms also demarcated race as an issue: ‘white guys who like blacks, they’re dinge queens […] if you like Asians, you’re a rice queen.’[217] As confident deviance in sexuality evolved into gay liberation, so too the racial demarcation was evident in the organisations that evolved in the 1970s. The former President of the Gay Activists Alliance (GAA), a spinoff group of the Gay Liberation Front (GFL), openly admitted that both organisations were ‘predominantly white male middle class with a smattering of women and a smattering of people of colour.’[218]

The justice system came down heavy on ethnic minorities, too.[219] Henry Giordano, the commissioner of Narcotics Bureau between 1962 and 1969, noted that ‘the probability of a college student, caught with one marijuana cigarette, ending up in jail “is absolutely nil.”’[220] Ethnic minorities were predominantly seen as the criminals in acts of confident deviance. Allen Ginsberg noted in an interview in the late 1960s how ‘the junk problem’ was an endemic issue, suggesting that ‘hippie and Puerto Rican junkies, mostly minority group junkies’ have their issues compounded, because they have ‘got the police on their necks, they can’t go to doctors, they have to pay fifty dollars a day to the Mafia for their medicine, they have to steal for it, and that causes animosity and crime and stealing back and forth.’[221] This reverberated in issues of sexual as well as narcotic nature. Police raids at the Stonewall Inn targeted African-Americans, and particularly the ‘elderly black’ cloakroom attendant.’[222] Another Stonewall Inn customer noted that the police would not hassle people who ‘would wear a tie and a suit.’ He admitted that he ‘was in several raids and they never bothered me.’[223]

Rich Wandel, GAA President in New York in the early 1970s surmised that the counterculture and other liberal groups marched along under the ‘pretence of integration and lack of racism’ but at the end of the day ‘we were better at talking about it than actually doing it.’[224] Whiteness – a concept linking both race and class – professed both racial and financial boundaries that counterculture did little to combat. Black Power, on the whole, proved to be more attractive in voicing anti-establishment sentiments for African-Americans grievances than did throwing bread across the hall at NYU.

Cosmopolitan Neighbourhoods – Greenwich Village to the East Village

‘… hostile Ukrainians and Puerto Ricans look askance at young men with flowers in their hair.’ [225]

Immigrant and ethnic minority communities often found themselves unwitting neighbours of the fiercest districts of New York’s counterculture in downtown Manhattan, coexisting yet leading very different lives. A policeman told the New York Times that the Village, ‘like all of New York, is known as a melting pot, but the trouble is there’s precious little melting. There is at best a degree of suspicious toleration.’[226] The final section of this chapter illustrates the relationship between hippies and immigrant groups, swinging from hostility to ambivalence and curiosity, and at points, cooperation. Second, it illustrates the eastward drift of New York’s counterculture from Greenwich Village to the East Village.

For Greenwich Village, 1960s counterculture was nothing new.[227] Accounts of Italian immigrants underwriting the coffeehouse culture of bohemian New York in the early twentieth-century attest to the significance of immigrant communities in creating the distinctiveness of the Village in the first place.[228] Children of Jewish immigrants constituted many of Greenwich Village writers in the 1940s.[229] The area attracted immigrant groups, artists and creative types alike from all over the world. Irving Sandler noted that ‘for most of the twentieth century, avant-garde painters and sculptors have made it a point to live in Greenwich Village or within easy walking distance of Washington Square.’[230] Greenwich Village is broadly defined as the area sandwiched between Broadway and the Hudson River, and Houston Street and 14th Street; and the Lower East Side ran the other side of Broadway, reaching out to the East River.[231] Yet, as Betsy Beazley has shown, ‘early in the decade, as Greenwich Village gradually gentrified, traditional Village residents moved east’ towards what was known as the East Village in the north-west corner of the Lower East Side.[232] The emergence of the underground publication, the East Village Other, in 1965, suggests much of this eastward shift.[233]

The New York Times noted that 45% of the Lower East Side’s residents were Puerto Ricans, 35% were ‘old line whites of Slavic, Italian and Jewish background, and 20% Negroes’ in 1967.’[234] Yet the streets and public parks these immigrant groups were joined by others. New York Post wrote that ‘the area, where coffee houses are numerous, is overrun by as many as 10,000 youngsters during warm spring and summer weekends. The atmosphere is wild and free. The boys’ hair is often long and the faces often bearded.’[235] The Village Voice commentedthat hippies interacted and lived alongside other groups, sharing the same blocks, neighbourhoods and streets. A reporter wrote that ‘Puerto Ricans shopped alongside kids dressed in levis, boots and heavy surplus store jackets.’[236] But hippies and Puerto Ricans, living worlds apart, would ‘go back to nearly identical apartments, three rooms and a tub in the kitchen for $62.50 a month.’[237] So too, hippies shopped in the same shops, buying ‘groceries at the supermarket, bread at the kosher bakery, late-night soda at the bodega’ whilst adding stores of their own, supplying psychedelic props and beads for long-haired hippy residents.[238] A former kosher butcher shop on 11th Street was converted into ‘Ed Sanders’ Peace Eye Bookstore’ selling underground magazines. Greenwich Village was a hybrid of hippie and immigrant cultures.

It was a contested vision over the use of a public park – Tompkins Square Park – on Memorial Day, 1967 that indicated abundant neighbourhood tensions. The New York Times, reporting the brawl that saw 9 hippies hurt and 38 arrested by the police for outlandish behaviour, described the park as ‘very ethnic. In the afternoon it is peopled by the local Ukrainians, Poles, Puerto Ricans, and Jews, all in their customary little groups.’[239] On the public holiday, hippies had been ‘sitting on the grass […] disturbing many residents of the neighbourhood with their bongo drums and Buddhist love chants.’[240] A middle-class Ukrainian voiced his concerns (anonymously), noting that ‘these unwashed beatniks are terrible […] our people [will soon] lose their patience with this dirty invasion. […] Nobody lets children into the park. Old men and women who want to rest are crowded off the benches.’[241] Only three days later a hippie music performance in the park would be disrupted by a group of Puerto Ricans, as ‘a melee broke out between the hippies and a crowd of Puerto Ricans and Negroes who hurled bottles and debris on the hippies and sought to strip one young woman of her clothes.’[242] Police were called to the park twice in three days; neighbourhood relations were tense.

Fig-20[243]

This is not to say that the 1960s tensions were different to those of older Greenwich Village counterculture.[244] Prior to the influx of hippies in the mid-1960s, there were still disgruntlements with radicals. Incidents between ‘slavs and bohemians’ were common prior to 1964 and students from NYU with a hippy manner ‘were said to have been beaten up by blond youths with broad Slavic faces.’[245] Yet it was not all violent; hippies and white ethnics were at times simply confused by each other. An account of hippies ‘asking for free flowers from a street vendor, without success’ precipitated ‘a wizened old Ukrainian staring at them in disbelief.’[246]

What was different about the 1960s in downtown New York was that many intolerant of bohemian lifestyles had moved away. A rabbi remarked that his institute had become a ‘Jewish ‘oasis’ in an area where members of his faith had once been dominant.’[247] It was not just Jews. ‘Many of the Polish families who used to cluster on East Seventh Street and some of the area’s former Czech and Ruthenian resident have moved away during the last few years.’ [248] But newsstands in the area demonstrated that there was still an appetite for Slavic, Hungarian, Italian and Yiddish publications, ‘together with the newer Spanish-language dailies.’[249]

This animosity was explainable. An intellectual noted that ‘Poles, Czechs, Ruthnians and Ukrainians are stolid types who go in for law and order in a big way,’ intolerant of the lifestyle of hippies and student radicals.[250] Cultural differences between ethnic minorities and hippies came from the fact that hippies had given up privilege, status and economic security, while Negroes and Puerto Ricans, while also poor, did not have the privilege of choice. A journalist noted that ‘by and large, Negroes view with bewilderment and ridicule the white hippies who flaunt, to the extent of begging on the streets, their rejection of what the Negroes have had scant opportunity to attain.’[251] The feeling was mutual for hippies, a New York hippie noted that Negroes and Puerto Ricans alike, ‘were fighting to become what we’ve rejected. We don’t see any sense in helping that.’[252]

But these patterns were not totalistic. The Village Voice’s assertion that the close-knit Italian neighbourhood was hostile to the influx of ‘hordes of strangers with strange customs’ flies in the face of the Italian mafia, who had long-standing pragmatic working relationships with New York’s bohemia, whatever the personal distaste individual mafia members may have felt.[253] For the 1960s, the Mafia ran many of the gay community’s bars – bars that had their licenses suspended by the New York Liquor Authority. A barman who lost his job after the Stonewall Inn was raided was offered ‘a job in New Jersey as a truck driver,’ and they were ‘very warm, down to earth, friendly people’ towards gays in the city.[254] Even the Dom on St. Marks’ Place, which had the longest bar in the world, was pioneered by a Pole. Located under the former Polish National Home, and serving Polish food – it was a celebrated hangout for hippies that bucked the trend of Polish intolerance with the counterculture.

Fig-21[255]

Puerto-Rican and hippie communities attempted to make amends, particularly after the Tompkins Square Riots. On the 15th August 1967, a group called the Diggers organised a party to assuage and calm tensions. Hosted at Cheetah (a nightclub further uptown), it brought together just shy of 1,000 Puerto Ricans and hippies. There were ‘free tickets distributed through the Diggers’ Free Store in the East Village, and through the Real Great Society.’[256] Allen Ginsberg noted that the hippies sought to engage with Puerto Ricans and Hispanic communities by pointing out the ‘common minority problems that everyone has.’ [257] A group called ESSO – East Side Social Organization – ‘tried to communicate this by putting out handbills printed in Spanish, for the Puerto Ricans, and English.’ [258] But equally, through music, there were attempted efforts to ‘open mixed cultural things, like Puerto Rican, Afro-Cuban music, and rock and Roll and folk in the band shell at Tomkins Square.’[259]

New York’s cosmopolitan demographics were, in many ways, exceptional and unique. But as Joshua Zeitz aptly noted ‘examining ethnic trends in a city like New York helps reveal them in other places, where the primacy of race politics [in the decade of Civil Rights and Black Power] rendered them more invisible to the naked eye.’[260] While this chapter is necessarily limited in scope, archival research interrogating these ethnic trends has shown race and ethnicity as consequential for our understanding of New York’s counterculture.

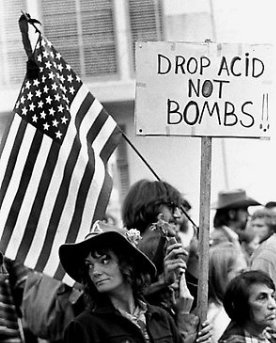

Chapter 3: Politics and Counterculture

Christopher Gair aptly noted that ‘the cultural artefacts of the ‘60s are canonised but the political agenda that accompanied them is discredited or overlooked.’[261] This, he explains, is partly because the culture – the music, the art and so on – ‘has become virtually a new orthodoxy’ while ‘many of the political advances that accompanied it have been reversed or halted.’[262] Bob Dylan earned the 2016 Nobel Prize in Literature, yet his reputation as a radical political agitator is all too easily lost for an individual who spent formative years of his career in the early-1960s in Greenwich Village.

Describing counterculture as a-political would belie compelling contrary evidence. While this dissertation has already shown that university politics was saturated by confident deviance, this chapter retrieves New York’s self-ascribed ‘a-political’ hippies’ engagement with city and local politics, illustrating that whilst earnest attempts were made in the early-1960s to articulate and forge a life independent from politics, efforts were short-lived, and pretty soon hippies took to the streets in pursuit of mainstream political demands.

Beyond hippies, confident deviance wove its way into the methods of routine city political engagement. Most apparent is its influence on the anti-war movement in the 1960s, with its strong student constituency. But this included, eventually, working-class protestors in the early 1970s who were fed up with keeping to political conventions.[263] The counterculture provided human fodder for the explosive liberation movements of the 1970s, influencing liberation movements too. Its impact was more than simply adding the likes of ‘guerrilla theatre’ to a political arsenal. It added a spontaneous rule-breaking mentality, and a youthful hyper-activeness to political protest. Culminating altogether, the counterculture is a piece of the puzzle of ‘decline’ that pervaded New York City, in the 1960s and 70s.

Hippy Politics

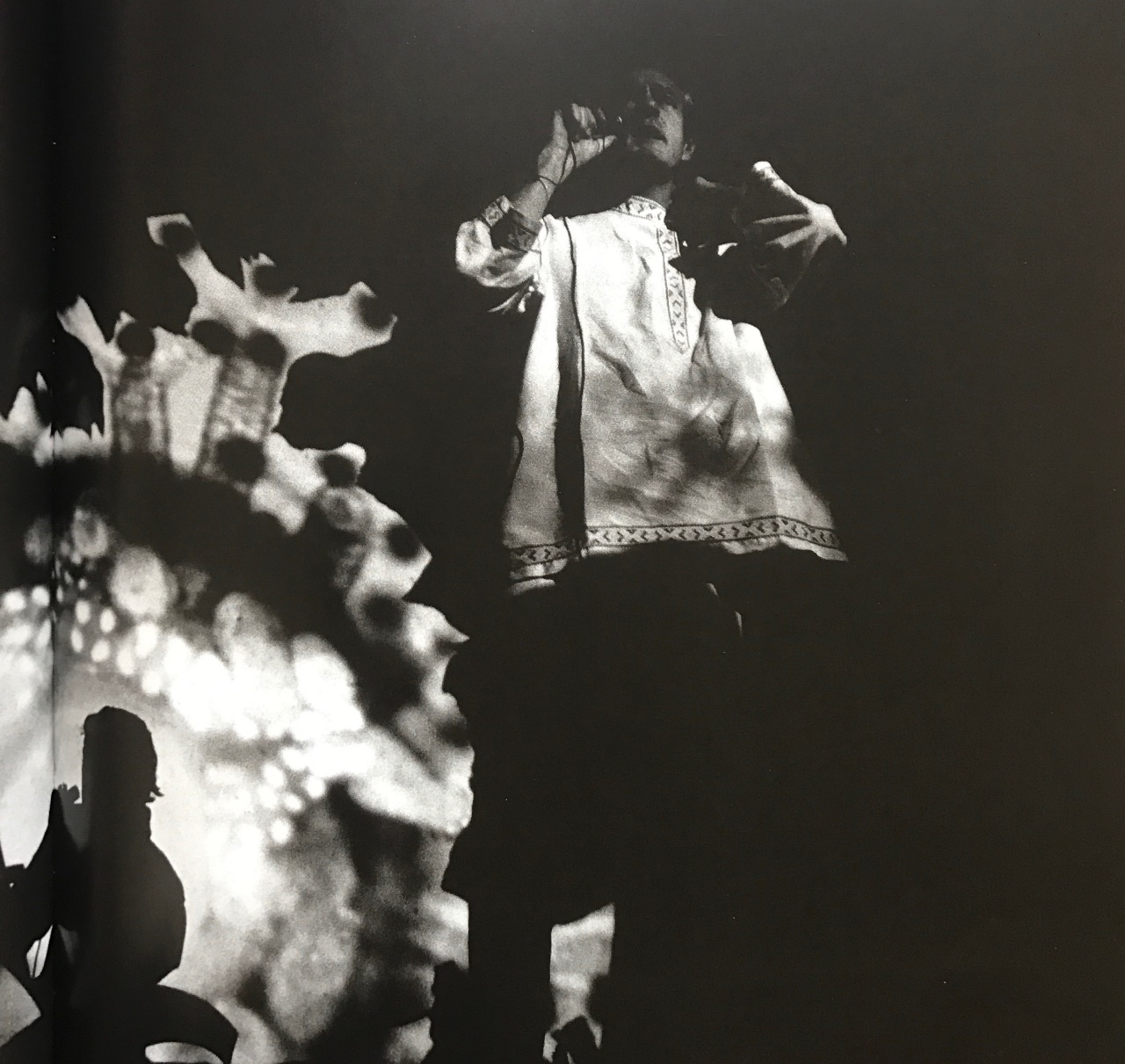

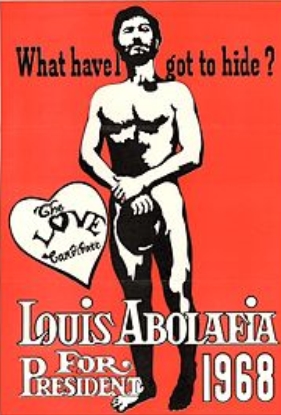

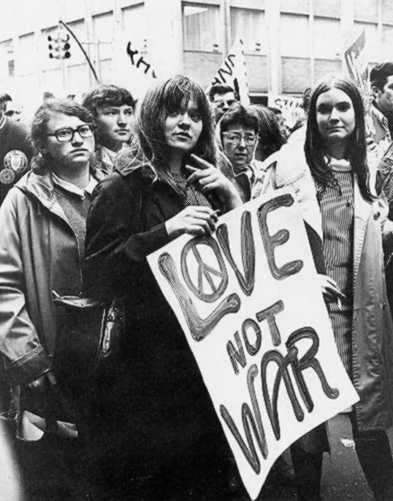

Fig-22[264]

It is widely thought that hippies were a-political, for they would use disapproving terms to denigrate fellow drop-outs as ‘politicos’ and ‘power freaks.’[265] Anarchist groups that were victims of their torments rebutted these claims, denigrating hippies and freaks for ‘having ‘conveniently metaphysical’ politics that were insubstantial and ineffective.’[266] That the nation of confident deviance was politically divided is evident, but the political chasm between anarchists and hippies reveals the difficulties in drawing any coherent conclusions from countercultural politics. Yet as David Farber noted, ‘a blurred boundary between so-called freaks and politicos had become increasingly commonplace in the late-1960s.’[267] For New York’s hippies, political activity from is palpable from 1965. While it was seemingly enough initially to have long hair and drop out of college, hippies and freaks soon came to defend their interests and engage in politics – initially on a local level.