The Development of a Dermatology Tactile Learning Tool

Info: 3117 words (12 pages) Dissertation

Published: 18th Nov 2021

Dermatology Tactile Learning Tool: Development and student evaluation of an interactive 3-dimensional skin lesion model for first year medical student education

Keywords: dermatology; education; medical student; 3-D models; learning tools, tactile learning, skin diseases, teaching

ABSTRACT

Background

Dermatology requires both visual and tactile expertise to formulate the pattern-recognition and analytical problem-solving skills that are essential for accurate diagnosis and treatment. However, current undergraduate dermatologic education focuses primarily on lectures and two-dimensional (2D) images.

Objectives

We sought to develop, implement, and assess a tactile learning tool (TLT) aimed at supplementing core lectures and improving dermatologic education for first year medical students.

Methods

A three-dimensional (3D) silicone TLT was designed to provide appropriate visual and tactile cues of common primary and secondary skin lesions. The TLT was then integrated into first year medical curriculum at the University of Colorado School of Medicine and its efficacy was measured through a survey.

Results

We successfully designed and synthesized a durable 3D printed TLT that can easily be mass-produced and used in medical schools throughout the United States. The vast majority of students surveyed were impressed with the TLT giving it an overall rating of 4.32/5.

Limitations

The results display students from one institution.

Conclusions

Overall students highly valued the TLT for its ability to provide tactile and visual teaching of common skin lesions. These results indicate that the TLT could improve the learning of medical students in dermatology and therefore may encourage other medical training programs to implement similar educational tools at their institutions.

Capsule summary

- The Tactile Learning Tool provides a 3D tactile and visual model of common skin lesions.

- Medical student satisfaction and confidence using the Tactile Learning Tool was overwhelmingly positive indicating its benefit in teaching dermatology terminology.

INTRODUCTION

Skin diseases account for up to 20% of visits to primary care physicians, with the majority of skin lesions initially seen by non-dermatologists1,2. However, dermatologic instruction in undergraduate medical education has been inadequate to meet this demand. Less than 50% of fourth-year medical students report being “somewhat skilled” or “very skilled” in the skin cancer examination3. In practice, non-dermatologists do not perform as well as their dermatology colleagues in correctly identifying common skin disorders4. Learning dermatology can be challenging for students because correct assessment requires both accurate pattern-recognition as well as analytical problem-solving. These skills can be difficult to acquire and master in brief clerkships or pre-clerkship courses5. In addition, expert clinicians rely on both visual and palpable cues to perform an effective skin exam, whereas student instruction often consists primarily of lectures and 2D images. Both the importance of visual and tactile properties have been demonstrated by several prior studies6,7,8,9, while others have shown that use of three-dimensional (3D) models improves recall, even at 3 months10. Haptic feedback has been shown to be important outside of dermatology as well11,12. Underlying proper diagnosis of skin lesions is a necessity for accurate description of primary and secondary morphologies.

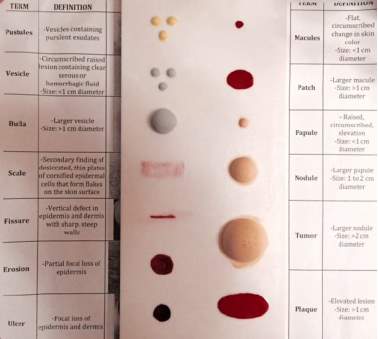

Considering the importance of tactile and visual learning in dermatology, we have developed a 3D Tactile Learning Tool (TLT) aimed at improving medical student’s understanding of common primary and secondary skin lesions. The tool aims to fill the void seen in the current medical school curriculum by providing an interactive, hands-on model of common skin lesions that more closely resemble lesions seen in clinic. To begin, we designed and fabricated a silicone 3D model that would provide students with both a visual and tactile impression of various skin lesions. Next, we included a relevant term and a short description of each lesion intended to be used along side the 3D model to provide students with appropriate context (Figure 1). Finally, we integrated the tool into the dermatology curriculum at the University of Colorado and then surveyed students to measure the effectiveness of the tool in supplementing traditional lecture and 2D image-based educational modalities.

METHODS

Design and fabrication of TLT

We started by creating a mold of various skin lesions using CAD software (license, company). This mold model was 3D printed (3D printer info) into an acrylic mold and later casted in silicone with the help of Protogenic, Inc (company info). The most recent iteration of the 3D silicone model was altered to possess a more natural skin color to better represent realistic skin lesions (Pantone Matching System, Pantone, Inc., Carlstadt, New Jersey). The silicone 3D model returned to us from the manufacturer was then appropriately painted for adjunctive visual demarcation. Finally, a relevant term and a short description of each lesion represented on the 3D model was included in the TLT.

Setting and participants

This study was conducted at the University of Colorado, Anschutz Medical Campus. All first year medical students enrolled in the dermatology pre-clerkship course were invited to participate in the study. Of the 184 first year medical students, 96 students elected to participate in this study.

Integration of TLT into curriculum

Prior to using the TLT, first-year undergraduate medical students received 18 hours of dermatology teaching during their pre-clerkship course. The dermatology pre-clerkship course occurs as part of the first year spring semester lasting two calendar weeks, meeting three days per week for a total of 18 contact hours. Ten hours are allocated for traditional large group lecture, 6 hours for small group case-based learning, and 2 hours for direct patient contact in a Grand Rounds-style format. Prior to the introduction of the TLT, dermatologic terminology was briefly discussed during large group lecture and small group sessions. Next students were presented with the TLT during a one-hour small group session led by dermatology residents. Resident small group facilitators distributed the TLT and discussed primary and secondary lesion terminology in this setting, allowing students the opportunity to reinforce visual, tactile and auditory stimuli with the TLT.

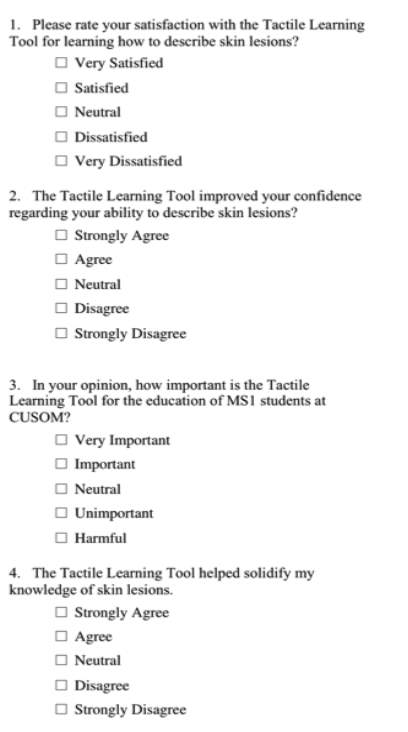

Survey instrument

To assess satisfaction with the TLT, a survey of first-year undergraduate medical students (n = 96) was performed after the dermatology pre-clerkship course (Figure 3). The survey consisted of four multiple-choice questions asking students to rank the impact of the TLT on the following variables: satisfaction with the TLT on learning how to describe skin lesions, confidence describing skin lesions, importance of the TLT for education of first-year medical students, and the TLT solidifying knowledge of skin lesions. The impact of the TLT on these variables was ranked on a five-point scale starting with dissatisfied/harmful and going to very satisfied/very important. Responses were assigned a weight, with the most favorable receiving a weight of 5 (very satisfied/very important) and least favorable receiving a weight of 1 (very dissatisfied/harmful). We further asked students to provide comment-based feedback on their experience with the TLT. The University of Colorado Institutional Review Board approved this study (IRB Number).

Data analysis

Categorical data and student comments were acquired from the student evaluations and organized in a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA). Categorical data was organized into appropriate groups to determine the number of students that selected each weighted group. Groups were assigned a numerical value from 1 to 5 going from least to most satisfied or strongly disagree to strongly agree. The mean value and standard deviation was calculated for each survey question and the corresponding answers. Further analysis converted the raw data into percentage of total students. Comments were separated from the categorical data and analyzed to detect any overlying themes.

RESULTS

Participation and demographics

Of the 184 students who engaged in the session, 96 responded to the TLT-specific survey.

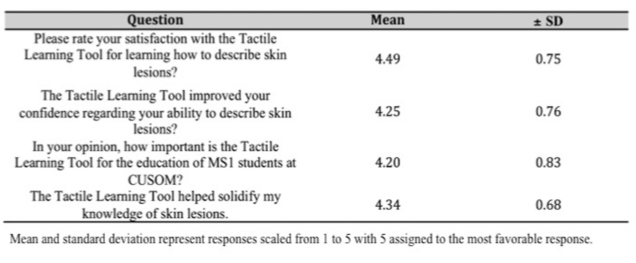

Survey

Results of the four survey questions are summarized and analyzed in Table 1. Overall, the majority of students responded in a very positive manner regarding the TLT. On a scale of 1 to 5 students rated their satisfaction wither the TLT for learning how to describe skin lesions with a mean of 4.49 (standard deviation 0.75). Students rated the TLT’s ability to improve confidence describing skin lesions at a mean of 4.25 (standard deviation 0.76). Students rated the importance of the TLT in first year medical curriculum at the University of Colorado at a mean of 4.20 (standard deviation 0.83). Finally, students rated the TLT’s ability to solidify knowledge of skin lesions at a mean of 4.34 (standard deviation 0.68). In terms of percentages, 94.8% of students that responded to the survey said that they were satisfied with the TLT as an educational tool; 85.4% agreed that the TLT improved their confidence in describing skin lesions; 82.3% noted that the TLT was an important educational tool; and 90.1% agreed that the TLT helped solidify their knowledge of skin lesions.

Student comments

The survey also included a “Other Comments” section in which students could provide additional feedback concerning the TLT. Overall student comments were extremely positive and appeared to reflect two common themes. First, students seemed to greatly appreciate the tactile learning component of this tool. Some examples of the comments received that express this trend were : “Loved this! Tactile learning is best”, “Nice way to have tactile learning”, and “Really cool to actually feel and know the difference”. Secondly, students stated that this TLT helped solifity the dermatology content that they learned in previous lectures and reading. Some comments expressing this theme were “Great way to confirm previous lessons” and “Didn’t necessarily teach me any of these things but helped solidify definitions in my head”. Student also provided comments to improve the sessions held using the TLT as well as the TLT itself. Some examples of these comments included, “If we had longer, it would be a helpful tool” and “They should be painted”.

DISCUSSION

Previous studies have shown dermatology education in medical school is extremely limited, leaving many students unconformable with basic skin lesion terminology and skin exams13, 14. This can present a significant problem due to the number of medical students that will go into primary care combined with the amount of skin disease seen by these providers15. In fact it has been shown that primary care providers are less proficient at diagnosing skin disease than dermatologists4. This can greatly impact proper diagnosis, management, and overall quality of medical care. Previous studies have demonstrated the importance of sensory inputs (visual and tactile) in dermatology; however medical student education is mostly limited to a lecture-based curriculum.

To combat these issues we aimed to design, produce, and implement a 3D silicone TLT designed to stimulate both tactile and visual learning. The TLT was created to fill the current void in medical student education and improve medical student understanding of common skin lesions. This is a fundamental concept that is not only important for diagnosing skin disease but also for communication between future dermatologists and non-dermatologists. Improper use of terminology may delay or even prevent timely diagnosis and treatment of patients. Following development and testing of the TLT we were able to show overwhelmingly positive feedback from first year medical students. Furthermore, students rated the TLT with a high overall average score of 4.32/5. Due to this, we consider the TLT to be a valid tool that can be used to improve first year undergraduate medical student understanding of primary and secondary lesion terminology.

We believe the advantage of using 3D models in educating first year medical students lies in the ability of students to directly engage with concepts and offers an opportunity for students to practice their dermatologic terminology. The incorporation of the TLT into medical school curricula can be a beneficial supplement to conventional educational tools, providing more opportunity for engagement and hands-on learning. Furthermore, this TLT was designed to provide a durable and consistent 3D model that may be used over many years and can potentially be distributed to other medical education programs. We achieved this by utilizing silicone casting to create a greater number of identical, durable TLTs. This process has the benefit of streamlining production and repair as well as the student to tool ratio, while preserving tactile quality.

In summary this study represents the successful integration of a dermatology tactile learning tool into first year medical student curriculum. This tool reported high satisfaction and increased student confidence in identifying common skin lesions. Furthermore, this TLT can be consistently produced and easily integrated into dermatology education in other medical programs across the country. In the future, we hope that this learning tool increases the knowledge of our future physicians resulting in better patient care.

References

1. Sari F. Skin Disease in a Primary Care Practice. Ski Dermatology Clin. 2005;4(6):350 – 353 . doi:10.1111/j.1540-9740.2005.04267.x.

2. Patadia DD, Mostow EN. Dermatology elective curriculum: Birdwatching list and travel guide. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17(6).

3. Geller AC, Venna S, Prout M, et al. Should the skin cancer examination be taught in medical school? Arch Dermatol. 2002;138(9):1201-1203. doi:10.1001/archderm.138.9.1201.

4. Federman DG. Comparison of dermatologie diagnoses by primary care practitioners and dermatologists a review of the literature. Arch Fam Med. 1999;8(2):170-172. doi:10.1001/archfami.8.2.170.

5. Burge SM. Learning dermatology. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2004;29(3):337-340. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2230.2004.01463.x.

6. Braverman IM. To see or not to see: How visual training can improve observational skills. Clin Dermatol. 2011;29(3):343-346. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2010.08.001.

7. Langley RGB, Tyler SA, Ornstein AE, Sutherland AE, Mosher LM. Temporary tattoos to simulate skin disease: Report and validation of a novel teaching tool. Acad Med. 2009;84(7):950-953. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181a84446.

8. Punj P, Devitt PG, Coventry BJ, Whitfield RJ. Palpation as a useful diagnostic tool for skin lesions. J Plast Reconstr Aesthetic Surg. 2014;67(6):804-807. doi:10.1016/j.bjps.2014.02.009.

9. Cox NH. A literally blinded trial of palpation in dermatologic diagnosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56(6):949-951. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2007.01.044.

10. Garg A, Haley H-L, Hatem D. Evaluating the Use of 3-Dimensional Prosthetic Mimics in a Dermatology Teaching Program for Second-Year Medical Students. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146(2):143-146. doi:10.1001/archdermatol.2009.355.

11. Våpenstad C, Hofstad EF, Langø T, Mårvik R, Chmarra MK. Perceiving haptic feedback in virtual reality simulators. Surg Endosc Other Interv Tech. 2013;27(7):2391-2397. doi:10.1007/s00464-012-2745-y.

12. Stalfors J, Kling-Petersen T, Rydmark M, Westin T. Haptic palpation of Head and Neck cancer patients – Implications for education and telemedicine. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2001;81(February 2015):471-474. doi:10.3233/978-1-60750-925-7-471.

13. Whitaker-Worth DL, Susser WS, Grant-Kels JM. Clinical dermatologic education and the diagnostic acumen of medical students and primary care residents. Int J Dermatol. 1998;37(11):855-859. doi:10.1046/j.1365-4362.1998.00537.x.

14. Hansra NK, O’Sullivan P, Chen CL, Berger TG. Medical school dermatology curriculum: Are we adequately preparing primary care physicians? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61(1):23-29.e1. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2008.11.912.

15. Lowell BA, Froelich CW, Federman DG, Kirsner RS. Dermatology in primary care: Prevalence and patient disposition. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45(2):250-255. doi:10.1067/mjd.2001.114598.

Figure Legend

Figure 1. Schematic

Figure 2. TLT

Figure 3. Survey administered to first year medical students following session using the TLT.

Table legend

Table 1. Mean and standard deviation of student responses for the Tactile Learning Feedback Survey. Student responses were weighed with the most favorable receiving a score of 5 and the least favorable a weight of 1.

Fig 2. Acrylic prototype with post-order processing, including painting and attachment of terminology and descriptions.

Fig 3. Survey administered to first year medical students following session using the TLT.

Table1. Mean and standard deviation of student responses for the Tactile Learning Feedback Survey. Student responses were weighed with the most favorable receiving a score of 5 and the least favorable a weight of 1.

Q1. Company names where the model fabrication was done?

Q3. IRB number?

Cite This Work

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing stye below:

Related Services

View allRelated Content

All TagsContent relating to: "Medicine"

The area of Medicine focuses on the healing of patients, including diagnosing and treating them, as well as the prevention of disease. Medicine is an essential science, looking to combat health issues and improve overall well-being.

Related Articles

DMCA / Removal Request

If you are the original writer of this dissertation and no longer wish to have your work published on the UKDiss.com website then please: