Determining the Level of Design Culpability in Construction Contracts

Info: 32281 words (129 pages) Dissertation

Published: 20th Jan 2022

Abstract

Despite preceding case law, scholarly journals and current legislation, the issue of design culpability applicable to construction contracts remains an issue, as disputes continue to be raised in court. The study investigated and addressed the issue, with the focus on whether design responsibility can be clearly delineated by the contractual parties to precisely define the contractual provisions at the time the contract is formed, and deliver certainty. The research strategies recognised design culpability as a conflicting obligation, embedded into industries contracts. Whilst the standards of care have the potential to fairly apportion responsibility, vague contractual terms lead to unclear intent, causing resistance between project stakeholders. It is, therefore, essential that the contractual parties liable for design realise their obligations and have a mutual understanding and interpretation of the contractual clauses.

Key Words: Design Culpability, Contract Law, Reasonable Skill and Care, Fit for Purpose, Contractor’s Designed Portions (CDP), Design and Build, Disputes

Table of Contents

Click to expand Table of Contents

1.0 Introduction

1.1 Background

1.2 Rationale

1.3 Hypothesis

1.4 Research Aim

1.5 Research Objectives

1.6 Research Findings

1.7 Guide to Study

1.7.1 Chapter 1: Introduction

1.7.2 Chapter 2: Literature Review

1.7.3 Chapter 3: Methodology

1.7.4 Chapter 4: Data Collection and Analysis

1.7.5 Chapter 5: Conclusion and Recommendations

2.0 Literature Review

2.1 Introduction

2.2 UK Construction Industry Context

2.2.1 The Industry

2.2.2 Professionalism in Construction

2.2.3 The Nature of Projects

2.3 Design Culpability

2.3.1 Implied Contractual Obligations of the Design Team

2.3.2 Implied Contractual Obligations of the Contractor

2.3.3 Distinctive Levels of Liability

2.3.4 Fitness for Purpose: Sale of Goods Act

2.3.5 Insurance

2.3.6 The Law of Contract and Tort

2.4 Construction Contracts

2.4.1 The Joint Contract Tribunal 2016

2.4.2 NEC Engineering and Construction Contract 2013

2.4.3 Traditional Procurement

2.4.4 Contractor’s Designed Portions (CDP)

2.4.5 Design and Build Procurement

2.5 Chapter Summary

3.0 Methodology

3.1 Introduction

3.2 Narrowing Down the Research Topic

3.3 Research Classification and Strategy Approaches

3.3.1 Quantitative Research

3.3.2 Qualitative Research

3.3.3 Quantitative vs. Qualitative Research

3.3.4 Triangulated Research

3.3.5 Research Design

3.4 Adopted Data Collection Methods and Justification

3.4.1 Questionnaires

3.4.2 Interviews

3.5 Limitations of Research

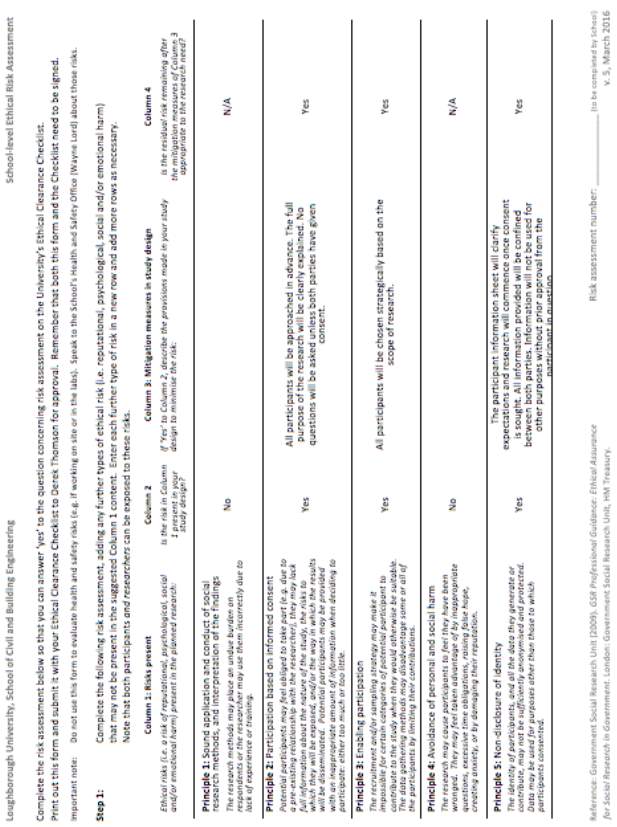

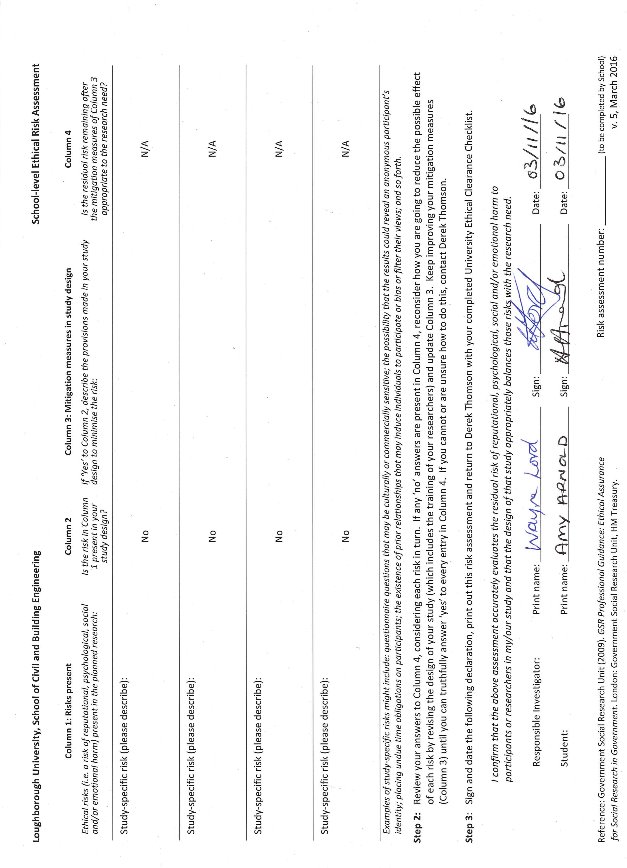

3.6 Ethical Considerations

3.7 Chapter Summary

4.0 Data Collection and Analysis of Results

4.1 Introduction

4.2 Analysis of Questionnaire Survey

4.2.1 Introduction

4.2.2 Profile of Survey Participants

4.2.3 Classifying Culpability

4.2.4 The Importance of Managing Design

4.2.5 Prominent Issues During the Construction Phase of Work

4.3 Analysis of Interviews

4.3.1 Introduction

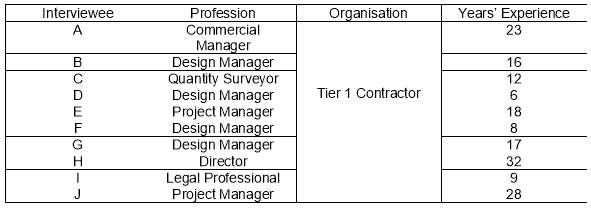

4.3.2 Profile of Interview Participants

4.3.3 Classifying Culpability

4.3.4 The Importance of Managing Design

4.3.5 Prominent Issues During the Construction Phase of Work

4.3.6 Lack of Quality Design Information Impeding the Contractor’s Performance

4.3.7 Requirements at Tender Stage

4.4 Chapter Summary

5.0 Conclusions and Recommendations

5.1 Introduction

5.2 Summary of Research Findings

5.2.1 Literature Review

5.2.2 Questionnaires

5.2.3 Interviews

5.3 Review of Research Objectives

5.3.1 Objective 1

5.3.2 Objective 2

5.3.3 Objective 3

5.3.4 Objective 4

5.3.5 Objective 5

5.4 Recommendations to Industry

5.5 Limitations of the Study

5.6 Recommendations for Further Research

References

Appendices

REQUIRED APPENDICES

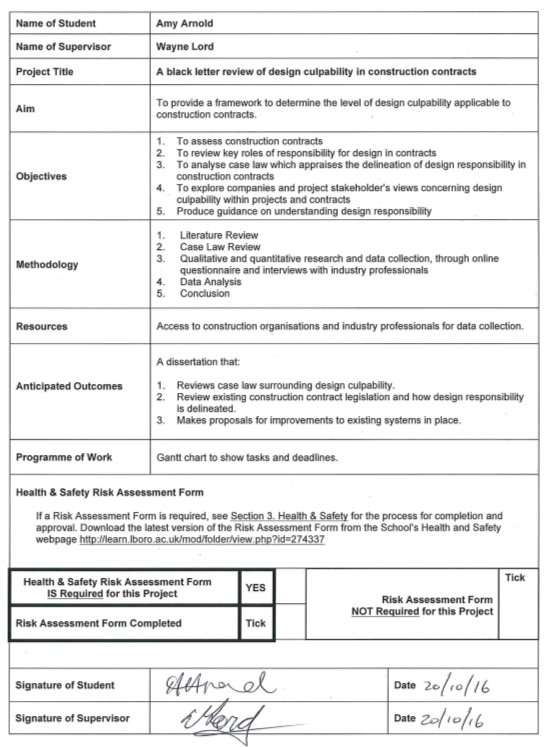

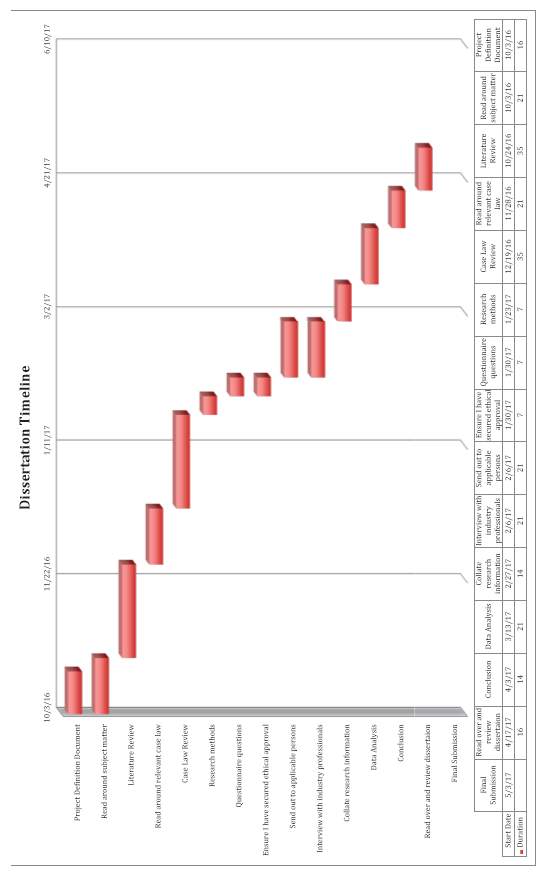

Appendix A: Project Definition Document & Gantt Chart

Appendix B: Health and Safety Risk Assessment

Appendix C: Ethical Clearance Email

Appendix D: Participant Information Sheet

Appendix E: Blank Informed Consent DISSERTATION APPENDICES

Appendix F: Questionnaire Survey Questions

Appendix G: SPSS (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences) Data Tables

Appendix H: Telephone Interview Transcripts

List of Tables

Table 2.1: DESIGN CULPABILITY IN CONSTRUCTION CONTRACTS

Table 3.1: PRINCIPLES OF QUESTIONNAIRE CONSTRUCTION (ADAPTED FROM NAOUM, 2013, P.60)

Table 3.2: COMPARISON BETWEEN A POSTAL SURVEY AND INTERVIEW TECHNIQUE (ADAPTED FROM TASHAKKORI AND TEDDLIE, 2002, P.303)

Table 3.3: INTERVIEW TYPES (ADAPTED FROM NAOUM, 2013, P.55 & 56)

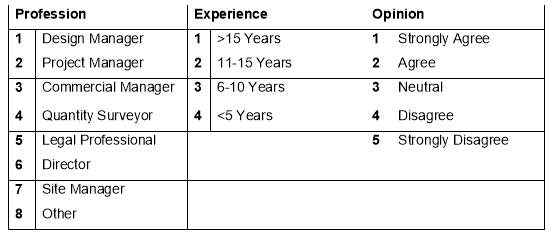

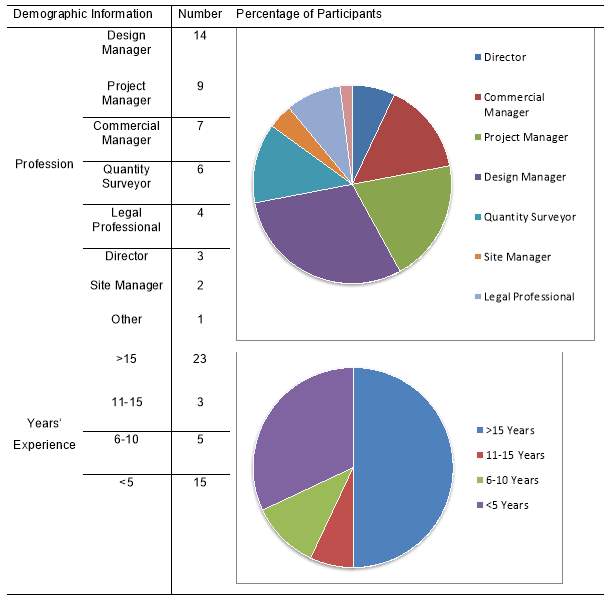

Table 4.1: ORDINAL SCALE RESPONSE CODING

Table 4.2: DEMOGRAPHIC PROFILE OF SURVEY PARTICIPANTS

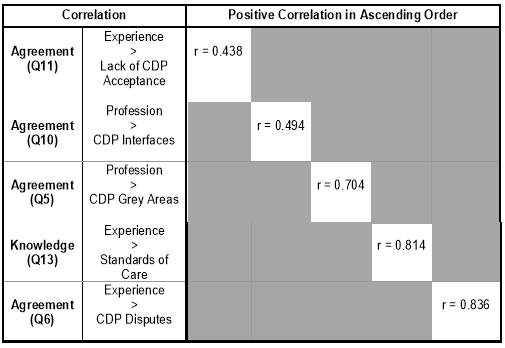

Table 5.1: DEMONSTRATION OF INCREASING CORRELATIONS(Q5, Q6, Q10, Q11, Q13)

List of Figures

Figure 1.1: RESEARCH APPROACH (ADAPTED FROM RAMACHANDRA, 2013, P.66)

Figure 2.1: LIABILITY SPECTRUM (GAAFAR AND PERRY, 1999, P.306)

Figure 3.1: THE NARROWING DOWN OF THE RESEARCH TOPIC (NAOUM, 2013, P.11)

Figure 3.2: TRIANGULATION OF QUALITATIVE DATA (FELLOWS AND LIU, CITED IN AMARATUNGA ET AL., 2002, P.24)

Figure 3.3: ILLUSTRATION OF DATA COLLECTION METHODS TO ACHIEVE THE FORMULATED OBJECTIVES

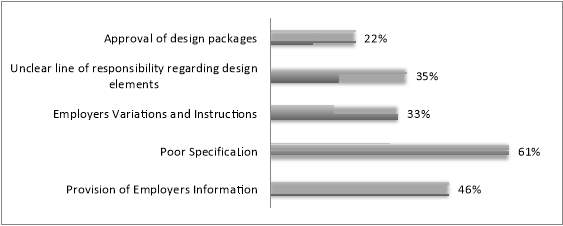

Figure 4.1: ISSUES DURING THE CONSTRUCTION PHASE (Q12)

List of Abbreviations

AEDM Architectural Engineering and Design Management

CDP Contractor’s Designed Portions

D&B Design and Build

ER Employer’s Requirements

JCT The Joint Contracts Tribunal

OGC Office of Government and Commerce

NEC The New Engineering Contract

SD Standard Deviation

SBC Standard Building Contract

SBC/Q Standard Building Contract with Quantities

SPSS Statistical Package for the Social Sciences

TCC Technology and Construction Court

TR Technical Requirements

Table of Cases and Statutes

Note: the page numbers for which cases are referred to have been shown in brackets at the end of each entry.

Bolam v Friern Hospital Management Committee [1957] QB, 1 WLR 582 (QB) (16)

Brunswick Construction Ltd v Nowlan [1974] SC, 21 BLR 27 (SC) (26)

Cooperative Group Ltd v John Allen Associates Ltd [2010] QB, EWCH 2300 (QB) (18)

Cooperative Insurance Society Ltd v Henry Boot (Scotland) Ltd (Costs) [2002] QB, EWHC 1270 (QB) (30)

Donoghue v Stevenson [1932] HL, AC 562 (HL) (27)

Esso Petroleum Co v Mardon [1957] CA, 2 WLR 583 (CA) (27)

George Wimpey & Co Ltd v DV Poole and Others [1984] QB, 128 SJ 969 (QB) (26)

Greaves & Co (Contractors) Ltd v Baynham Meikle & Partners [1975] CA, 3 ALL ER 99 (CA) (17,22,25)

IBA v EMI Electronics Ltd and BICC Construction Ltd [1980] HL, 14 BLR 1 (HL) (22)

John Mowlem & Co v British Insulated Callenders Pension Trusts Ltd and Others [1970] DC, 3 CON LR 63 (DC) (30)

Lanphier v Phipos [1838] CP, 173 ER 581 (CP) (23)

Lindenberg v Joe Canning and Others [1992] QB, 62 BLR 147 (QB) (23)

Merton LBC v Lowe & Another [1981] CA, 18 BLR 130 (CA) (18)

Moresk Cleaners Ltd v Hicks [1966] QB, 4 BLR 50 (QB) (17,18)

MT Højgaard A/S v EON Climate and Renewables UK Robin Rigg East Ltd [2015] CA, BLR 431 (CA) (20)

Murphy v Brentwood DC [1990] HL, AC 398 (HL) (27)

Plant Construction Ltd v Clive Adams Associates and JMH Construction Services Ltd [2000] CA, BLR 137 (CA) (23)

Pratt v George J Hill Associates [1988] CA, 38 BLR 25 (CA) (18)

Prier v Refrigeration Engineering Company [1968] SC, 442 621 (SC) (27)

RM Turton & Co Ltd (In Liquidation) v Kerslake & Partners [2000] CA, 3 NZLR 406 (CA) (23)

Sale of Goods Act 1979 Supply of Goods and Services Act 1982

Tai Hing Cotton Mills v Liu Chong Hing Bank [1985] PC, AC 80 (PC) (27)

Viking Grain Storage Ltd v T H White Installations Ltd and Another [1985] QB, 33 BLR 103 (QB) (22)

Walter Lilly & Co Ltd v Mackay [2012] TCC, EWHC 1972 (TCC) (29)

Young & Marten Ltd v McManus Childs Ltd [1968] HL, 3 WLR 630 (HL) (21)

1.0 Introduction

This chapter highlights the developments of the research problem through addressing the aim and objectives, methodology undertaken and the key findings.

1.1 Background

The detrimental effects unclear contractual provisions, regarding design culpability, have on construction projects and the stakeholders involved, have been highlighted in leading case law and widely acknowledged industry reports and journals over the last 30 years:

- Viking Grain Storage Ltd v T H White Installations Ltd and Another [1985] QB, 33 BLR 103 (QB) (22)

- Limitation of Design Liability for Contractors – Gaafar and Perry (1999)

- Contract Theory and Contract Practice: Allocating Design Responsibility in the Construction Industry – Carl J Circo (2006)

- Design Liability: Problems with Defining Extent and Level – Sarah Lupton (2015)

- MT Højgaard A/S v EON Climate and Renewables UK Robin Rigg East Ltd [2015] CA, BLR 431 (CA) (20)

- The National Construction Contracts and Law Survey (2015)

The issues do not arise solely due to design culpability, but the contractual conflicts and disputes that ascend from the ambiguous performance obligations and contingent contracts. Kraus and Scott (2009) highlight the importance of, “honouring the contractual intent of the parties” (p.1). However, little academic attention has been given to the, “structure of contractual intention” (p.1). It has been recognised that courts now ask, “how a reasonable person would have understood her partner’s intention at the time of contracting” (p.1). A potential weakness with the delineation of design responsibility, is accurately defining and appointing it. Therefore, it is crucial that as the contractual agreements are formed, culpability is mutually agreed with declarations of who is liable for what.

When writing up legally enforceable contracts, the parties must select the contractual provisions and can outline vague or precise terms (Hermalin, 2008). Vague terms endeavor to use the courts to allocate a concrete definition to these phrases, if the case is adjudicated, to allow for interpretation. The parties may not be obliged to specify exact obligations at the time the contract is formed, however, these phrases may provide reason for dispute. Precise terms obviate the requirement of the courts input, enforcing the explicit and accurate obligations the parties have stipulated in advance of adjudication.

Although, Hermalin (2008) illustrates how often difficulties may arise in, “precisely describing potentially relevant contingencies” (p.1) as the contract is written up. This research seeks to understand and explore how design culpability is set out within construction contracts and the level at which this liability is assigned to key stakeholders. Furthermore, it aims to analyse relevant case law that appraises the delineation of design culpability and provide a framework to determine the level of design responsibility applicable to construction contracts.

1.2 Rationale

Hermalin (2008) suggests that “vagueness of language” and, “the difficulty of precision” (p.2) may impede efficient contracting due to incomplete provisions. He went on to say, “if it is difficult to describe contractual contingencies, then how do the parties to the contract necessarily communicate their intentions to each other?” (p.24). These vague terms can often be the foundation for disputes and, “hinder the smooth execution of contracts” (Lai, Yik, and Jones, 2004, p.51). Therefore, “a clear definition of the responsibilities of the contracting parties is crucial” (p.44). The underlying principle of this research is to gather professional perspectives from lead contractors to ascertain the implications of vague design culpability and perceived work scopes in the UK construction industry.

1.3 Hypothesis

The research hypothesis is: ‘The clear delineation of design responsibility will require the contractual parties to precisely define the contractual contingencies at the time the contract is formed, as well as ensure the stakeholders have the same intentions and understanding of these provisions’.

1.4 Research Aim

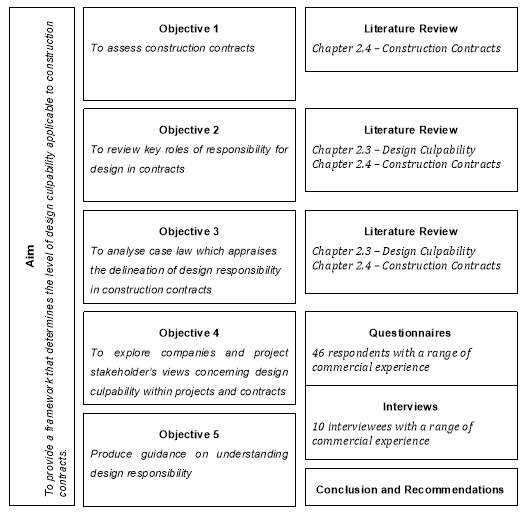

The aim of this research study is to provide a framework to determine the level of design culpability applicable to construction contracts.

1.5 Research Objectives

To achieve the research aim, there are five objectives:

- To assess construction contracts;

- To review key roles of responsibility for design in contracts;

- To analyse case law which appraises the delineation of design responsibility in construction contracts;

- To explore companies and project stakeholder’s views concerning design culpability within projects and contracts, and

- Produce guidance on understanding design responsibility.

1.6 Research Findings

Key findings of the study are as follows:

- Construction contracts required the contractual parties to precisely define the contract provisions as the contract is formed to avoid misunderstanding;

- Where contractor’s design portions are concerned, interfaces between CDP and non-CDP elements require attention to highlight lines of responsibility;

- A spectrum of liability is required to develop industries understanding;

- For use at tender stage, a template should be developed to expose outstanding design information;

- Design and build contracts need to adapt to offer the capability to manage complex designs and/or high level finishes, and

- There is a lack of suitably qualified design managers to cope with their increasing demand.

1.7 Guide to Study

1.7.1 Chapter 1: Introduction

Provided an overview of the research problem and current knowledge and perspectives, highlighting the background and rationale to the study. The hypothesis, aim and objectives and key findings were identified. The Project Definition Document can be found in Appendix A along with an effective time-management strategy.

1.7.2 Chapter 2: Literature Review

Analytical and critical appraisal of current literature and case law related to the research study. The chapter presented industry context, followed by recognition of design culpability applicable to various construction contracts and project stakeholders.

1.7.3 Chapter 3: Methodology

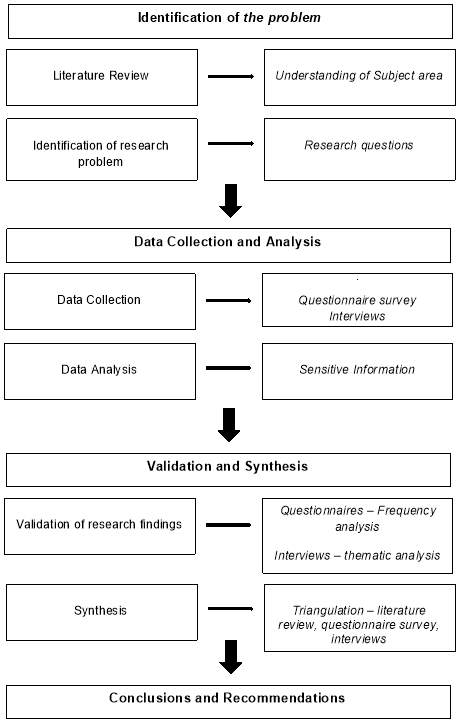

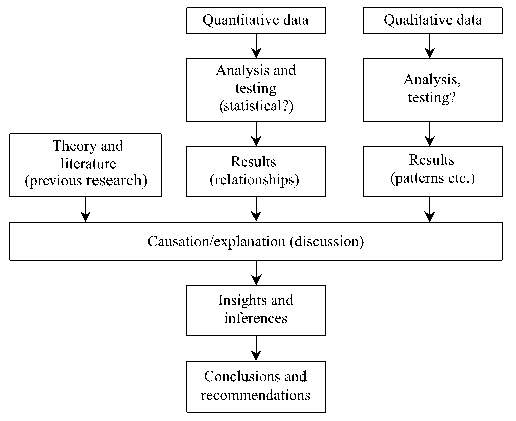

The chapter classified the strategic approaches available and outlined the research method adopted (as shown in Figure 1.1), which was relevant to the solution of the defined problem. It identified the limitations of the research along with establishing the credibility and ethical values adhered to.

1.7.4 Chapter 4: Data Collection and Analysis

Documented the analyses and findings from the questionnaire survey and telephone interviews, in line with the literature findings, research problem and objectives (section 1.5), to identify key themes and patterns.

1.7.5 Chapter 5: Conclusion and Recommendations

A series of concluding results were formed in conjunction with the literature findings, research problem and the set of objectives (section 1.5). Following a provision of recommendations to the industry, limitations of the study and recommendations for further research.

Figure 1.1: Research Approach (Adapted from Ramachandra, 2013, p.66)

2.0 Literature Review

2.1 Introduction

This chapter aims to establish the context for the research by reviewing literature surrounding the allocation of design culpability within a construction contract. A review of the UK construction industry, construction contracts and key project stakeholders’ roles and responsibilities in relation to design culpability will be critically appraised. Throughout the chapter, relevant case law will be analysed as well as leading publications to demonstrate the level of understanding and guidance around design culpability.

2.2 UK Construction Industry Context

2.2.1 The Industry

The industry is highly complex (McDonnell, 2013), interlinking key stakeholders such as consultants, clients, and contractors. A construction project team involves a string of professionals, specialists, and suppliers, each a unique collection of participants appointed for the project’s needs; their professional expertise guide a project to completion. It is, therefore, essential to understand construction contracts, not only as standard forms but also as documents that are flexible, allowing for clause adaptations, to meet the needs and demands of each individual scheme.

Waterhouse, Peckett, Malleson and Beaumont (2015) highlight complying with lawful responsibilities, along with having the appropriate clauses in place to deal with construction disputes, as fundamental procedures to aid a smooth construction process. McDonnell (2013) agrees, depicting detailed contractual terms which appropriately allocate risk and responsibility as significant measures.

2.2.2 Professionalism in Construction

Many scholarly journals base their view of professionalism on individual characteristics and behaviours. However, Martimianakis, Maniate, and Hodges (2009) suggest a focus on these alone, “is insufficient as a basis on which to build further understanding of professionalism” (p.829). Professionalism can be further defined by personal characteristics, ethics and diversity (Martimianakis, Maniate, and Hodges, 2009). To enhance professionalism within the industry, numerous organisations have direct links with higher education, supporting individuals on academic courses gaining qualifications. (Hughes, Murdoch and Champion, 2015). This close involvement enables the industry to develop and continually build on its corpus of knowledge.

2.2.3 The Nature of Projects

Hughes et al. (2015) suggest that commercial risk and project teams are, “the most significant defining characteristics of projects and project strategies” (p.8). Each construction project is unique, thus increasing inherent risks. These risks need to be appropriately managed to ensure the project is completed to the required quality, within time and on the budget. A construction project could be described as a puzzle in relation to the parties who form the temporary organisational structure. A scheme will piece together various specialist skills and groups of people to form a project team, who will all eventually disengage their duties upon completion of their requirements (Hughes et al., 2015). Thus, pieces of the puzzle will come and go throughout the duration of a project, a factor that gives rise to its constantly changing environment.

2.3 Design Culpability

Victor O. Schinnerer and Company Inc. (2017) refer to design responsibilities as obligations which are enforceable at law, “arising out of the performance of, or failure to perform, professional services by the design professional” (Victor O. Schinnerer and Company Inc., 2017, p.2). Traditional contractual relationships would see the client entering two separate contracts for the design and construction phases of work. However, modern tendencies have seen a lean towards both bespoke and design and build contracts, where the contractor is burdened with obligations for both design and construction.

The National Construction Contracts and Law Survey 2015 developed a questionnaire to identify which procurement methods were most frequently used by contractors over that past 12 months, which highlighted that design and build procurement was selected by 49%, as opposed to traditional procurement by 34% of respondents (Waterhouse et al., 2015, p.10). Express provisions within a construction contract detail both the design teams and contractor’s obligations under the contract, outlining the level of responsibility delineated in respect of the design.

2.3.1 Implied Contractual Obligations of the Design Team

2.3.1.1 Level of Culpability

The decisions held in Bolam v Friern Hospital Management Committee[1], confirm that professional designers are required to use ‘reasonable skill and care’: “Where you get a situation which involves the use of some special skill or competence, then the test as to whether there has been negligence or not is … the standard of the ordinary skilled man exercising and professing to have that special skill. A man need not possess the highest expert skill; … it is sufficient if he exercises the ordinary skill of an ordinary competent man exercising that particular art”[2].

However in Greaves & Co (Contractors) Ltd v Baynham Meikle & Partners[3], the structural engineers were held liable for a higher standard of care due to an implied contractual term that required the design to be fit for its intended purpose. Without this term though, the engineers would have been culpable for negligence, breaching their duty to use reasonable skill and care as competent, professional persons. It, therefore, should be highlighted that assumptions cannot be determined regarding implied obligations of the designer: “The law does not usually imply a warranty that [a professional] will achieve the desired result, but only a term that he will use reasonable care and skill. The surgeon does not warrant that he will cure the patient. Nor does the solicitor warrant that he will win the case”[4].

2.3.1.2 Delegation of Design Work

Hughes et al. (2015) advise that the architect has single point responsibility for the design of the work, and without authority to delegate items of this work, he will be personally responsible for all defects, as held in Moresk Cleaners Ltd v Hicks[5]. Where a consultant has signed up to design works that have developed into areas they do not strictly have the necessary knowledge or skills to carry out to the required detail, they are faced with a problem. The judged ruled in Moresk that: “An architect who lacks the ability or expertise to carry out part of a design job has three choices:

- To refuse the commission altogether;

- To persuade the employer to employ a specialist for that part of the work, or

- To employ and pay for a specialist personally, knowing that any liability for defective design can then be passed along the chain of contracts”[6].

In this case, an architect was employed to prepare plans and specifications for an extension to Moresk’s laundry. The architect delegated design work to a subcontractor, and when a claim was brought against him in court, he argued that it was an implied term in his contract that he had the authority to delegate design. However, if a professional is appointed to carry out design works and accepts the contract, he is agreeing he can provide such works himself. The court found no such implied term existed within the contractual provisions and stated, “if a building owner entrusts the task of designing a building to an architect, he is entitled to look to that architect to see that the building is properly designed”[7].

Due to the evolving nature of projects and modern construction technology, which have increased in complexity and speciality, there are a greater chance employers will give architects the authority to delegate works (Hughes et al., 2015). Thus, leading to, “an increased dependence on specialists at both the design and construction stages of a project” (p.205). Cooperative Group Ltd v John Allen Associates Ltd[8] considered the designer’s reliance on guidance from another professional, “construction professionals did not by the mere act of obtaining advice or a design from another party thereby divest themselves of their duties in respect of that advice or design”[9]. The case went on to review Merton LBC v Lowe & Another[10], where the architect was given entitlement to delegate design, unlike in Moresk, which held that when given the authority, they owe a duty of care to their employer, “construction professionals could discharge their duty to take reasonable care by relying on the advice or design of a specialist if they acted reasonably in doing so”[11].

This does not make the architect liable for defects in their specialists work, but if they negligently recommended the use of their skill set, they could potentially be liable for their employer’s losses (Hughes et al., 2015). As held in Pratt v George J Hill Associates[12], the defendant architect was held liable after claiming that a contractor was suitable, though in practice they were not. The contractor became insolvent, and the architect was liable to the client for the money they were unable to recover from the contractor due to their recommendation.

2.3.2 Implied Contractual Obligations of the Contractor

2.3.2.1 Level of Culpability

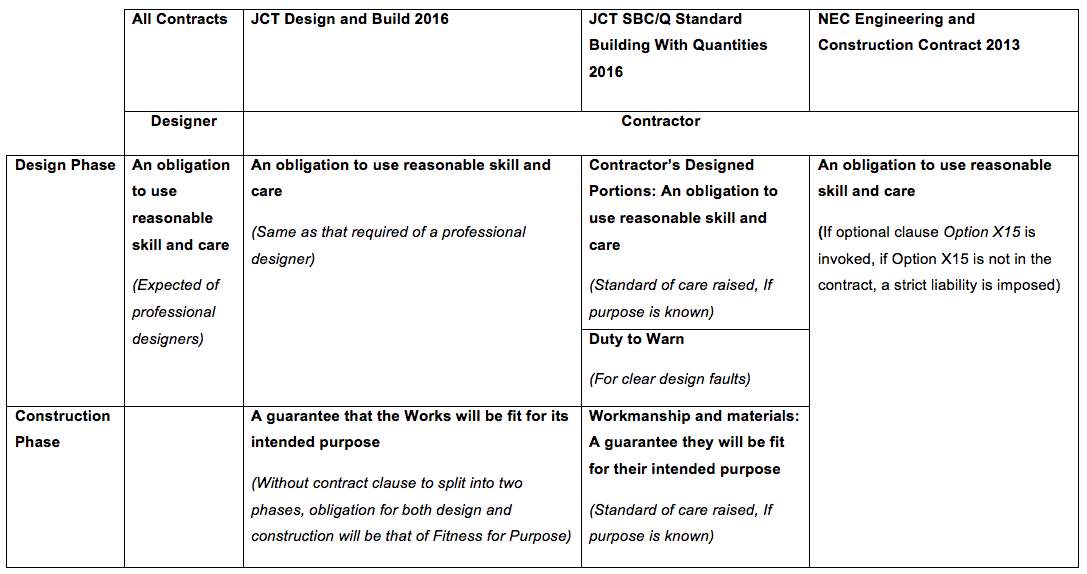

The NEC Engineering and Construction Contract 2013 permits the contractor to rebut a liability presumption if optional clause ‘Option X15’ is invoked. This clause limits the contractor’s liability for his design to reasonable skill and care, “the Contractor is not liable for defects in the works due to his design so far as he proves that he used reasonable skill and care to ensure that his design complied with the Works Information” (Institution of Civil Engineers, 2013, p.52). The implementation of this clause allows the contractor to prove his non-negligence where there is a fault to escape liability.

However, a strict liability will be imposed upon the contractor if this clause is not invoked, to guarantee that the design will be fit for its intended purpose. Without proving he used reasonable skill and care, he will be liable for defects in the works due to his design. The burden of proof is reversed in this case, whereby the contractor is guilty until proven innocent. In both JCT’s Design and Build Contract 2016 and SBC/Q Standard Building Contract with Quantities 2016, there is a similar clause relating to the completion of design work.

Article 1 under the design and build contract states that, “the Contractor shall complete the design for the Works” (The Joint Contracts Tribunal, 2016, p.3) and under the SBC/Q contract, clause 2.2.1 states, where the works include a Contractor’s Designed Portion, the contractor shall, “complete the design for the Contractor’s Designed Portion” (The Joint Contracts Tribunal, 2016, p.33). ‘Complete’notions that the contractor is required, where he is taking on a design, to satisfy himself that the design and/or works are fit for purpose. Determining the standard of care owed by the contractor in a design and build contract presents a challenge given their dual role.

In JCT’s Design and Build Contract 2016, clause 2.17.1 states: “Insofar as his design of the Works is comprised in the Contractor’s Proposals and in what he is to complete in accordance with the Employer’s Requirements and these Conditions (including any further design that he is required to carry out as a result of a Change), the Contractor shall in respect of any inadequacy in such design have the same liability to the Employer, whether under statute or otherwise, as would an architect or other appropriate professional designer who holds himself out as competent to take on work for such design and who, acting independently under a separate contract with the Employer, has supplied such design for or in connection with works to be carried out and completed by a building contractor who is not the supplier of the design” (The Joint Contracts Tribunal, 2016, p.35).

Virtually the same clause as above is present in the JCT’s SBC/Q Standard Building Contract with Quantities 2016, clause 2.19.1 p.38, to define design liabilities where there is a Contractor’s Designed Portion. However, “express terms can override the normal default” (Lupton, 2015, p.102). The standard of care applicable to design and build contractors has been subject to review and analysis since its development in the modern construction industry. Barry Joseph Miller (1982) recommended that a sole fitness for purpose standard of care should be implied when a contractor is engaged in both, “transactions” (p.132) allowing for uniformity.

This could be perceived as unfair, as a lower standard is enforced on a professional designer carrying out only design under a traditional form of contract. They are required to carry out design work with reasonable skill and care, and therefore, if the designer can prove he has done so, and the construction works fail, the contractor will be held accountable for not providing works that are fit for purpose. He cannot shift this culpability back onto the design team if they produced their design work with reasonable skill and care. However, clause 2.17.1 and clause 2.19.1 (referenced above) seek to address this issue, with a clear demarcation between the design and construction phases.

The clause denotes that for the design phase of work, the contractor has the ‘same liability’, as would a professional designer, in contrast to Miller’s beliefs. Therefore, the contractor is only required to carry out their design services with reasonable skill and care. It is only for the construction phase of work that the contractor will have to attain a fitness for purpose standard. Exclusive of this clause, the contractor is obligated to deliver both design and construction works fit for purpose.

These clauses set out to limit culpability, however, they could be amended, as demonstrated by the National Rail 10 Schedule of Amendments (Network Rail, 2016): “2.17.1 Insofar as the design of the Works is comprised in the Contractor’s Proposals and in what the Contractor is to complete in accordance with the Employer’s Requirements and these Conditions (including any further design which the Contractor is to carry out because of a Change), the Contractor warrants and undertakes to the Employer that: 2.17.1.1 he has exercised and will continue to exercise in the design of the Works all the reasonable skill, care and diligence to be expected of a professionally qualified and competent architect, engineer or other appropriate consultant considering the size, scope, nature, type and complexity of the Works; 2.17.1.2 the Works will, when completed, comply with any performance specification or requirement included or referred to in the Employer’s Requirements or the Contractor’s Proposals”.

Both standards of care co-exist in this clause, which supports Mr. Justice Edwards-Stuart’s remarks in MT Højgaard A/S v EON Climate and Renewables UK Robin Rigg East Ltd[13]. He noted that “it is not uncommon for the two obligations … to exist side by side in construction contracts, as they are not mutually incompatible”. The court deliberated whether the contractor’s obligation was limited to using reasonable skill and care or whether it was under a strict obligation to achieve a service life of 20 years. The scheme of the Technical Requirements (TR) led the judges to believe that the 20-year design life was an intention, not a guarantee, which is dissimilar to a warranty to achieve that design life. Further to this, the TRs made no specific reference to a guarantee of 20 years. If it was a requirement, it should have been made patently obvious not, “tucked within the technical requirements”[14].

2.3.2.2 Workmanship and Materials

An implied fit for purpose obligation may arise on the part of the contractor, “in relation to goods and materials supplied” (The Joint Contracts Tribunal, 2013). In the case of Young & Marten Ltd v McManus Childs Ltd[15], the Court of Appeal held that: “There will be implied into a contract for the supply of work and materials a term that the materials used will be of merchantable quality and a further term that the materials used will be reasonably fit for the purpose for which they are used”.

The facts of the case stipulated this implied term as the contract sufficed to exclude it. The contractor installed tiles that were, “latently defective and thereby breached the implied term (of merchantable quality)”[16]. Further to this, a fitness for purpose obligation may arise where the employer makes known the exact intended purpose of the goods, “expressly or by implication” (The Joint Contracts Tribunal, 2013).

In Greaves, Lord Denning explained: “The owners made known to the contractors the purpose for which the building was required … to show that they relied on the contractors’ skill and judgment. It was, therefore, the duty of the contractor to see that the finished work was reasonably fit for the purpose for which they knew it was required. It was not merely an obligation to use reasonable care. The contractors were obliged to ensure that the finished work was reasonably fit for the purpose”[17].

It was Lord Scarman’s obiter remarks in IBA v EMI Electronics Ltd and BICC Construction Ltd[18], which affirmed a further implied term that can arise with regards to the entire completed structure: “In the absence of a clear, contractual indication to the contrary, I see no reason why one who during his business contracts to design, supply, and erect a television aerial mast is not under an obligation to ensure that is it reasonably fit for the purpose for which he knows it is intended to be used.

The critical question of fact is whether he for whom the mast was designed relied upon the skill of the supplier (i.e. his or his subcontractor’s skill) to design and supply a mast fit for the known purpose for which it was required”[19]. If the purpose of a design is made known, in line with the statutory law regulating the sale of goods (Sale of Goods Act, 1979), the designer accepts that the standard of care will be raised to a fit for purpose obligation.

In Viking Grain Storage Ltd v T H White Installations Ltd and Another[20], Judge John Davies QC questioned why the duty in relation to design should be any different than the standard expected for the quality of materials: “I find it difficult to comprehend why an entire contract to build an installation should need to be broken into so many pieces with differing criteria of liability. The virtue of an implied term of fitness for purpose is that it prescribes a relatively simple and certain standard of liability based on the reasonable fitness of the finished product irrespective of considerations of fault and of whether its unfitness derives from the quality of work or materials or design”[21].

2.3.2.3 Duty of Care

Construction professionals are legally required to carry out their services with a duty of care. As discussed by Thomas J in RM Turton & Co Ltd (In Liquidation) v Kerslake & Partners[22]: “It has been generally accepted that duty of care will arise where the relationship between the parties manifests the following criteria:

- The maker of the statement possesses a special skill;

- He or she voluntarily assumes responsibility for the statement and it is foreseeable that the recipient will rely on it;

- It is reasonable for the recipient to rely on the statement and he or she does so, and

- The recipient suffers loss as a result” (Adriaanse, 2016, p.278).

Emden stated in Binder VI (cited in Adriaanse, 2016), that: “It is thought that provided the contractor carries out work strictly in accordance with the contract documents, he is not responsible if the works prove to be unsuitable for the purpose which the employer and architect had in mind” (p.116). Though, if the contractor finds discrepancies in the design documentation, drawings and between the statuary provisions and the works, they are required to, under the JCT Design and Build Contract 2016, clause 2.13 and 2.17, report to the employer (The Joint Contracts Tribunal, 2016).

In Plant Construction Ltd v Clive Adams Associates and JMH Construction Services Ltd[23], the defendant appealed against an implied duty to warn for defective design, “of which it was aware but for which another party was responsible”. Failure to raise it caused the plaintiff to, “suffer economic loss”. Based on the decision held in Lindenberg v Joe Canning and Others[24], which held that where a contractor fails to raise concerns and proceeds with the contract he, “is in breach of an implied term that it would exercise the standard of care to be expected of an ordinary, competent building contractor”, Clive Adams Associates were held culpable.

2.3.3 Distinctive Levels of Liability

The standard of care for design is either an obligation to use reasonable skill and care or a guarantee that the design will be fit for its intended purpose. If reasonable skill and care are not achieved where required, the party is said to have been negligent (Marshall, 2011). Lupton and Cornes (2013) expand on Marshall’s statement by suggesting that the distinction between the two standards necessitates industries understanding as “in the former case negligence has to be shown whereas in the latter case there is an absolute obligation which is independent of negligence” (p.50).

Gaafar and Perry (1999) acknowledge that these overarching design principles may be due to an oversimplification subject to the lack of legal definition surrounding the two standards of care. Jackson and Powell (1992) sought to explain their position by reference to the case of Lanphier v Phipos[25], which initially expressed the standard of care over 100 years ago: “Every person who enters into a learned profession undertakes to bring to the exercise of it a reasonable degree of care and skill.

He does not undertake if he is an attorney that at all events you shall gain your case, nor does a surgeon undertake that he will perform a cure, nor does he undertake to use the highest degree of skill. There may be persons who have a higher education and greater advantages than he has, but he undertakes to bring a fair, reasonable and competent degree of skill”[26].

Holub’s (2017) study discusses how a professional is to provide a service with the “goal of achieving the desired result, but not a guaranteed result” (p.2). Design and construction professionals lack the control necessary to unequivocally guarantee the outcome of their services. It is unclear as to whether a design that is to be produced with reasonable care and skill should likewise be required to be fit for its purpose.

Fitness for purpose is seen to be the greater duty, Adriaanse (2016) endeavoured to define them: “A product or design may not be fit for its purpose without any allegation of fault. Where a particular purpose is made known by the employer, negligence need not be proven. All that had to be shown is that the particular purpose specified has not been achieved. As far as reasonable skill and care is concerned, it has to be proved that the design was negligent and that the designer did not use reasonable skill and care” (p.293).

2.3.3.1 Liability Spectrum

Gaafar and Perry (1999) state that the interpretation of fitness for purpose is dependent on the facts and circumstances of each case. The authors recommended that the industry develops a further understanding of what each level of design responsibility distinctly means, and expand the levels not only as two principles, but broadened into a scale that can be concisely drafted into contract clauses, as a robust solution in the prevailing legal and insurance contexts.

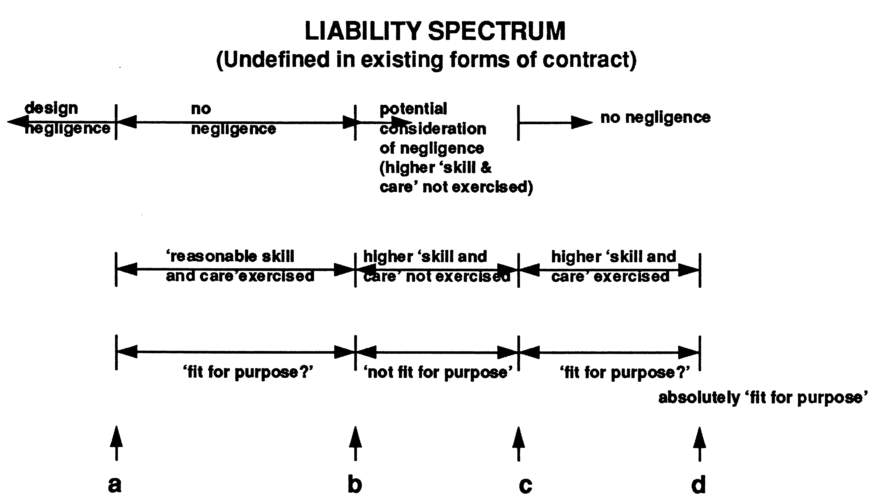

Figure 2.1: Liability Spectrum (Gaafar and Perry, 1999, p.306)

Figure 2.1 is a spectrum deduced from Gaafar and Perry’s research. The latter end of the spectrum ‘d’,demonstrates the contractor’s fitness for purpose liability. Here the intended purpose of the works needs to be clearly communicated by the client, as well as the requirements, to ensure this strict obligation is applied. On the opposite end of the spectrum ‘a’, the contractor will only be held liable to have exercised reasonable skill and care through their negligence. Most existing forms of contract, “attempt to limit the contractor’s liability to either boundary a or d” (p.307). Considering the decisions held in Greaves[27], Gaafar and Perry sought to explain how the determined liability may be placed at a point in-between the spectrum of ‘a and b’.

A professional designer is required to provide a design with reasonable skill and care, however, it was held that the contract stipulated that the defendant was required to take specific steps, “to discharge the duty to exercise reasonable skill and care” (p.305) which had not been taken. If they had been, it was said the design would have been fit for purpose. The spectrum between a and b implies that there may be circumstances in which, “reasonable skill and care may equate to fitness for purpose” (p.306), which corresponds to this decision. Boundary ‘c’ could occur anywhere between ‘b and c’, “in cases where higher skill and care may be interpreted by some practitioners as reasonable skill and care” (p.306), as held in George Wimpey & Co Ltd v DV Poole and Others[28].

George Wimpey aimed to persuade the court that they, “had been negligent on the basis that its special expertise meant it owed a higher duty of care than ordinary competence”. For the plaintiff to claim against his professional indemnity policy, he had to prove his negligence. A perceived problem is establishing the expected level of skill and care conceptualised by boundary ‘a’. If a party has been negligent, the courts have direct reasoning to hold the culpable party at fault for not exercising reasonable skill and care. Where there is potential consideration of negligence, the spectrum between ‘b and c’ is applied. And whereby higher skill and care is exercised, the level of liability lies between ‘c and d’. Brunswick Construction Ltd v Nowlan[29] demonstrates the highly critical nature of assuming a level of design culpability applicable to project stakeholders. In Brunswick, the contractor was held liable for a design defect, owing to his duty to warn, even though he had no direct responsibility for producing any of the design.

The case particulars were extreme, as the client relied entirely on the skill and judgement of the contractor, without any consultants to supervise. However, it proves that it is the specific circumstances of each project and contract that controls the liability applicable to a stakeholder, which can range anywhere from ‘a to d’. Gaafar and Perry’s (1999) notions outline design liability as a combination of factors that are all influenced by implied terms (from statute), clauses that form part of the contract and the manner in which these clauses and specifications have been written.

2.3.4 Fitness for Purpose: Sale of Goods Act

“English Law distinguishes between those who contract to supply a product and those who provide a service” (Adriaanse, 2016, p.276). The Sale of Goods Act 1979, under Section 14: Quality or Fitness, 14.3 states: “Where the seller sells goods in the course of a business and the buyer, expressly or by implication, makes known to the seller any particular purpose for which the goods are being bought, there is an implied condition that the goods supplied under the contract are reasonably fit for that purpose” (Sale of Goods Act, 1979). Both the Sale of Goods Act 1979 and Supply of Goods and Services Act 1982 further stipulate that “goods are of satisfactory quality if they meet the standard that a reasonable person would regard as satisfactory” (Supply of Goods and Services Act, 1982).

2.3.5 Insurance

Fitness for purpose obligations are commonly implied into building contracts, however, they can be the root cause of disruptions and disagreements between parties. This is due to the improbable position that contractors and professionals alike will be able to obtain professional indemnity insurance for such an obligation (Gaafar and Perry, 1999). If contractors are posed with it, it leaves them with a lacuna uninsured risk.

2.3.6 The Law of Contract and Tort

The Court of Appeal held in Esso Petroleum Co v Mardon[30] that where the “same set of facts amount to a breach of contract and tort, the plaintiff could choose in which action to frame a claim” (Adriaanse, 2016, p.276). This put the plaintiff in a better position, as the limitation period in the law of tort is longer than that in the law of contract, “since a tort action can be brought when the limitation period in the contract has expired” (Adriaanse, 2016, p.276). However, this decision was superseded in Murphy v Brentwood DC[31] initially retreated in Tai Hing Cotton Mills v Liu Chong Hing Bank[32], where Lord Scarman said that, “there … (is no) advantage to the development of the law in searching for a liability in tort where the parties are in a contract” (Adriaanse, 2016, p.276).

Professionals must comply with their appointment, and collateral warranties are in place to help remedy defective building works. In Donoghue v Stevenson[33] the Court of Appeal held that “liability was limited to physical damage caused by negligence and did not extend to economic loss” (Adriaanse, 2016, p.277). A leading issue in many cases, and what is of concern is the recuperation of costs associated with building repairs due to negligently constructed works. To ensure issues such as these do not arise, the contract terms regarding liability need to be clearly assessed and redefined, as to not leave construction professionals wholly responsible.

2.3.6.1 Design Culpability in the Law of Contract and Tort

Carl J Circo (2005) advocates that contract principles have been proven to be, “less significant than tort principles in the development of design liability law” (p.599). He went on to say that very few construction contracts fully prescribe, “standards of professional responsibility” with few implementing the standard of care present in the law of tort. It is often declined in court that an implied contractual obligation to produce a design without defects and with a certified result exists.

However, in contrast, and held in Prier v Refrigeration Engineering Company[34], under a D&B contract, “where a person holds himself out as qualified to furnish and does furnish, specifications and plans for a construction project, he thereby impliedly warrants their sufficiency for the purpose in view”. This could infer its applicability only to design and build contracts, however, it is ambiguous. Design culpability in the law of tort is subject to reasonable skill and care, regardless of the designer’s profession. In contract, it is only when the purpose for the works they are designing is known, that the consultancy’s designer’s responsibility evolves from the exercise of reasonable care and skill, into a strict liability.

2.4 Construction Contracts

The purpose for organisations involved in a construction project to enter into a contract is to set out the rights, duties, and obligations of each party, primarily for clarity and to, “record their expectations” (Victor O. Schinnerer and Company Inc., 2017, p.2). Further to this, McDonnell (2013) stated that contracts establish, “the design professional’s terms and scope of service” (p.659). He suggested that clear contractual provisions will:

- “Preserve parties’ risk allocation;

- enforce the reasonable expectations of the parties;

- place the risk of loss on the party better able to bear it, and

- cement the contractual foundation of the design industry with certainty and predictability” (p.671-672).

Despite forming this contractual relationship, McKeeman and Rossetti (2007) conflict McDonnell’s remarks by suggesting that, “design professionals would not be able to contractually limit their potential liability on a project” (p.10). Revealing that protection could be achieved through, “broader and/or more stringent contractual protections” (p.10). Professor Sarah Lupton (2015) recognises that “all too often, perhaps because of a shortage of time, insufficient care is given to finalising these key documents” (p.96).

2.4.1 The Joint Contract Tribunal 2016

The JCT suite of contracts is the most frequently used, accounting for 39% of the UK market in 2015 (Waterhouse et al., 2015, p.17), used predominantly for lower value projects. However, the National Construction Contracts and Law Survey 2015 highlighted the shift in commonly used contracts, with a decrease in the use of JCT forms, accounting for 60% in 2011 (Waterhouse et al., 2015, p.17). Drafted by a cross-section of industry bodies, the JCT suite is generally acknowledged as having a pro-contractor bias. The suite of contracts includes minor works, intermediate, standard, design and build, and ‘with contractor’s design’ options.

2.4.2 NEC Engineering and Construction Contract 2013

The NEC suite of contracts has seen a rise in use accounting for 30% of the UK market in 2015 (Waterhouse et al., 2015, p17), commonly used for higher value projects. In 2011, only 16% of people said they used NEC contracts most often (Waterhouse et al., 2015, p.17). The Office of Government Commerce endorses NEC contracts as ‘Achieving Excellence in Construction’, a set of government principles around collaboration and whole life cycle costing for construction procurement (Office of Government and Commerce, 2007). Unlike JCT though, its contract forms are a ‘one size fits all’ approach, with options to tailor to the project.

2.4.3 Traditional Procurement

Sir Michael Latham’s (1994) Constructing the Team report commented on the segregation between the design and construction phases on a project, and also the lack of clarity between the duty to use reasonable skill and care and the requirement of fitness for purpose. Traditional building procurement divides design and construction into two separate entities, “the employer and the professional designers assume responsibility for the design of the building, and the contractor agrees to build what has been designed” (Adriaanse, 2016, p.128).

The employer’s design team should produce full drawings, specifications and a bill of quantities, to enable the contractor to construct. The contractor has an obligation to construct, “in strict accordance with the contract documents provided” (Hughes et al., 2015, p.197). It is important to establish whether a defect is because of the design or construction phase of works, as this identifies who is culpable for it. Taking into account this segregation, “the employer when faced with a defective building or structure may have to bring claims against both the designer and contractor” (Adriaanse, 2016, p.304). Commonly defects do not fall entirely into either category of design or workmanship, which leads to an overlap between the two.

2.4.4 Contractor’s Designed Portions (CDP)

Under a traditional form of contract, the contractor will be culpable for elements of ‘contractor’s design’. The employer must notify, as a requirement of the contract, the contractor of all work that is to be a CDP. The importance of this was highlighted in Walter Lilly & Co Ltd v Mackay[35], where it was held that the contractor was not liable for defective work, as a clear notification was not given for the CDP packages of work. “Subsequent instructions issued in conformity with the contractual terms” (Lupton, 2015, p.99) were required. However, Circo (2005) questioned whether notifications involving additional design require control to, “prevent the lead design team from requiring unwarranted, unreasonable, or excessive changes to the specialty design” (p.599).

If it is intended that the contractor is to take on such responsibility, it should be made, “certain that the contract documents clearly identify the scope of services and functions that each design party will provide” (Circo, 2006, p.599). Further to this, the documents must identify suitable procedures for, “submitting and finalising the specialty design documents” (p.599). Circo (2006) went on to highlight, “points of connections and interfaces” as, “important design parameters that the lead design team must furnish” (p.599). Where the works comprise Contractor’s Designed Portions, the contractor is obliged to complete the design, “including the selection of any specifications for the kinds and standards of the materials, goods and workmanship to be used in the CDP Works” and integrate the design, “with the design on the Works as whole” (The Joint Contracts Tribunal, 2016, p.35).

Work on these design packages cannot proceed until they have been signed off by the design team. Adriaanse (2016) questioned, “to what extent can the contractor depend on the design provided by the employer’s professional advisers?” (p.309). In Cooperative Insurance Society Ltd v Henry Boot (Scotland) Ltd (Costs)[36], the contractor argued that they were only responsible for generating detailed drawings from the initial design produced by the employer, without liability to check its feasibility. It was held, the conditions of the contract, “required the contractor to develop the conceptual design provided by the engineers into a design capable of construction” (Adriaanse, 2016, p.309). Therefore, the contractor was required and responsible to form an opinion as to whether he believed the design was valid at the point in which he took it on. However, subject to clause 2.13.2 (under the SBC/Q Standard Building Contract With Quantities 2016) it now states, “the Contractor shall not be responsible for the contents of the Employer’s Requirements or for verifying the adequacy of any design contained within them” (The Joint Contracts Tribunal, 2016, p.36).

This is a significant contractual provision from a contractor’s perspective as it rebuts the decision held in Cooperative (2002), where the contractor was liable for the complete design. Although ultimate responsibility to ensure the design complies with the contract still rests with the contractor. It is important that the preliminary design that is handed over to the contractor is produced with reasonable skill and care, as highlighted by John Mowlem & Co v British Insulated Callenders Pension Trusts Ltd and Others[37].

Proceedings took place to identify whether the contractor was liable for defective works. It was held that the engineers were guilty due to their negligent design, which ultimately resulted in failure. Express terms under the NEC Engineering and Construction Contract 2013 for the contractor’s design liability is written in Section 2, under clause 21.1, “the Contractor designs the parts of the works which the Works information states he is to design” (Institution of Civil Engineers, 2013, p.7). The acceptance procedure for contractor’s design is under clause 21.2 and 21.3. The contractor is required to submit, “the particulars of his design… to the Project Manager for acceptance” (Institution of Civil Engineers, 2013, p.7). As with the JCT contracts, these sections of works cannot proceed until the design has been accepted. Clause 21.3, states that the design may be submitted in parts if, “parts can be assessed fully” (Institution of Civil Engineers, 2013, p.7).

Further to this, the project manager has the authority to reject the design where it does not comply with the Works Information. As highlighted by McElroy, Friedlander and Hennig Rowe (2006) the role of the architect/ engineer (design team) has reformed with regards to the review and approval of drawings. “Design professionals now seek to limit their liability for design detail provided by others to a review for overall compliance with the design intent” (p.10). This could be seen to be an area of controversy regarding industry practice. The National Construction Contracts and Law Survey (2015), concurs with these statements, accounting Contractor’s Designed Portions for 17% of disputes in construction projects due to the grey area surrounding liability for these ‘packages’, their extent and approval (Waterhouse et al., 2015, p.23).

However, the conclusions drawn from Pain and Bennett’s (1988) study found that the 49 projects they surveyed using JCT with Contractor’s Design (many of whom were using it for the first time) experienced no serious issues, with a fraction suffering minor difficulties, which suggests that these packages have become more of a problem in recent years.

2.4.4.1 Employer’s Requirements

The Employer’s Requirements (ER) is a list of necessities formed by the design team for each CDP ‘specialist package’ documenting what the contractor is required to achieve. They are set out in the tender contract documents and in response to them, the contractor will submit Contractor’s Proposals. Chan, Chan, and Yu (2005) believe the clearer the ER, the fewer problems the contractor will encounter during the construction phase of works. The level of detail included in the requirements and the extent of the design handed over to the contractor is variable from project to project.

Chan and Yu (2005) note that the amount of information provided by the consultants is a common area of dispute as it may be a simplistic specification; however, it may also be a complete performance specification and concept design (Pain and Bennett, 1988). McElroy et al. (2006) stated that often the construction phase of works commences prior to the completion of, “plans and specifications” (p.4) which are likely to have a critical effect on the “timely completion of the design phase” (p.8). Ultimately, if the ER is clearly defined from the outset it can pave the way for project success. “The better prepared they are, the keener the price from the contractor and the less likely there will be disputes” (Institution of Civil Engineers, 2016).

2.4.4.2 Sub-Contracting

It is the main contractor’s responsibility to procure specialist subcontractors for any contractor’s design however, the employer or design team may propose their preferences. Often the contractor will tender out to three or four companies and present a list to the design team to decide who is appointed to carry out the work. This is a domestic subcontract, whereby the contractor is liable as if he had not subcontracted.

Further to this, the employer or design team can instead put forward a list of three or four subcontractors whom they wish the contractor to work with. The liability for these named subcontractors remains with the contractor as they have a choice. It is only when the employer or design team nominates a subcontractor, which the contractor is required to use without any choice, that the liability for that subcontractor is shifted back onto the employer or design team.

Experience in industry highlighted that there are design professionals with an in-depth understanding of this liability clause, which results in a manipulative approach. Albeit the design team named subcontractors, a forceful encouragement of one left the contractor with no choice but to go into contract with them. The design team was then able to escape liability, which would have been imposed had the subcontractor been nominated, although ultimately, they made the choice.

2.4.5 Design and Build Procurement

Design and build contracts involve, more often than not (Turina, Radujkovic, and Car-Pusic, 2008), the contractor taking on sole responsibility for both design and construction of the works (Doloi, 2008). Rowlinson (1987) considers the approach to be independent, suggesting expertise for both phases should reside with a single stakeholder who has, “sufficient resources to complete any task that arises” (p.3). Castro (2009) proclaimed that the contractor, “must be held responsible for the hybrid responsibilities they have assumed” (p.30).

Miller (1982) argues that “the design-build model removes the internal conflict, waste, and clouding of responsibility that is inherent between the client, architect and contractor” (p.128). Further to this, Turina et al. (2008) suggest that this procurement route reduces the likelihood of misunderstandings and simplifies processes and Tam (2000) notes it, “improves buildability” (p.2). However, Castro’s (2009) counteracting views consider the process to have, “inherent conflict” due to, “the merger of these opposing roles” (p.31).

2.5 Chapter Summary

In expectation of a greater understanding of current thinking on design culpability in construction contracts, the review appraised literature surrounding the research area. When dealing with design liability, Hughes et al. suggest considerations that need to be taken into account: “the nature of design and its complexity, how the law actually defines design obligations; and third, which participants in the construction process may be liable in respect of design faults” (Hughes et al., 2015, p.197). Delineation of design culpability within construction contracts can often be the root cause of disputes that are detrimental to project team relationships. The National Construction Contracts and Law Survey (2015) found that contractor’s designed portions accounted for 17% of disputes in construction projects due to the grey area surrounding liability for these ‘packages’.

There is often confusion about the extent of CDPs, unclear or overlapping requirements appearing in contractual terms, and their related technical documents. Gaafar and Perry highlighted the confusing nature of the standard of care applicable to construction contracts, stating that, “reasonable skill and care may equate to a fitness for purpose” (Gaafar and Perry, 1999, p.306) obligation, dependent on the specific wording of the clause. It is vital that the contracting parties define what is intended within the contract documents. In particular, the hierarchy of contract clauses within each document, and the relationship between documents, and should ensure that the allocation of detailed design tasks and level of responsibility for each is crystal clear, with no gaps or overlaps (Waterhouse et al., 2015).

Table 2.1: Design culpability in construction contracts (Subject to standard clause provisions)

Where contractor’s designed portions are integrated within projects, the following may benefit their clarity:

- The extent of the package should be accurately defined;

- Special care should be given to the interfaces between CDP and non-CDP items, and

- It may be that at tender stage, the exact scope of items of work that are to be the contractor’s design is unknown. Where this occurs, procedures for the instruction of CDP items need to be distinctly noted in the contract terms and obeyed to ensure there is no doubt an item of work is or is not a CDP.

Further research questions that have arisen from the literature review are as follows:

- How can standard contracts be reviewed and updated to include interfaces for CDP packages, specifically to identify design responsibility at these boundaries or outline an agreement going forward on how to manage interface CDP elements with the remaining design;

- Understand how the standard of care be clearly defined within all construction contracts, to avoid confusion and dependency on specific contract clause wording, and

- Achieve an understanding as to how contractors can contractually approach design liability, to manage risk, avoid disputes, and understand their obligations.

3.0 Methodology

3.1 Introduction

This chapter explores and compares research approaches, and identifies the most suitable. A decisive explanation has been given regarding the choice made, and potential limitations and restriction for the research have been acknowledged.

3.2 Narrowing Down the Research Topic

Research can be defined as, “a scientific and systematic search for pertinent information on a specific topic” (Kothari, 2004, p.1). It is, therefore, critical that a process of selection, narrowing down and framing of the final focus of the research takes place at this stage of the research project (See Figure 3.1). Following an industrial placement, the identification of design culpability as an initial idea led on to discussions with industry professionals (colleagues) along with academic staff, and a review of scholarly journals; which produced a refined topic area.

Focus areas assisted in producing a preliminary report on Contractor’s Designed Portions from both an employers and contractor’s perspective. The evolution from the initial idea to an appraisal of the effectiveness of current contract provisions and legislation to restrict unclear delineation of design culpability led to a solution and aim to provide a framework to determine the level of design culpability applicable to construction contracts and produce guidance on understanding design responsibility.

Figure 3.1: The narrowing down of the research topic (Naoum, 2013, p.11)

3.3 Research Classification and Strategy Approaches

Research is conducted to find out the result of a given problem. It can be described as an “action plan” (Naoum, 2013, p.39) for obtaining and analysing data. According to Fraenkel and Wallen (1993), the term research can refer to any sort of, “careful, patient study and investigation in some field of knowledge, undertaken to discover or establish facts and principles” (p.4). Kerlinger (1979) presents a more detailed definition of research defining research as a “systematic, controlled, empirical, and critical investigation of hypothetical propositions about the presumed relations among neutral phenomena” (p.8).

In contrast to these definitions, Fellows and Liu (2015) illustrated research as a “voyage of discovery” (p.4). The purpose of research is to, “gain familiarity with a phenomenon or to achieve new insights into it” (Kothari, 2004, p.2). Research methodology is, “the principles of the methods by which research can be carried out” (Fellows and Liu, 2015, p.49) with aims to implement a precise and analytical approach. There are various approaches to data collection, however, researchers suggest that two main paradigms have influenced research, both quantitative and qualitative.

3.3.1 Quantitative Research

Quantitative research is, “objective in nature” (Naoum, 2013, p.39) and tends, “to relate to positivism” (Fellows and Liu, 2015, p.29). Amaratunga, Baldry, Sarshar and Newton (2002) suggest that it is, “concerned with determining the truth-value” of suggestions to test a theory (p.22). This correlates with Johnson and Onwuegbuzie’s (2004) statements that major characteristics of quantitative research include, “theory or hypothesis testing” (p.18). This research approach is deductive in nature, subject to the researcher’s point of view.

By revealing hard, reliable data that is tangible it allows for, “flexibility in the treatment of the data” (Amaratunga et al., 2002, p.22) to enable verification of reliability. This research strategy is superlative, “when you want to find facts about a concept, a question or an attribute” (Naoum, 2013, p.40). The approach enables the researcher to study the “relationship between the facts in order to test a particular theory” (Naoum, 2013, p.40). The usual process for quantitative research originates with the researcher’s theory. A set of data is collected to test this theory, which can be analysed to evaluate whether there is ‘truth’ behind it.

3.3.2 Qualitative Research

Qualitative research seeks to, “gain insights” (Fellows and Liu, 2015, p.29) through investigating, “the beliefs, understandings, opinions and views” (p.29) of people. The role of the researcher when conducting qualitative research is to gather a, “holistic overview of the context under study” (Punch, 2013, p.119). It focuses on words and is, “subjective in nature” (Naoum, 2013, p.41). Typically presenting the point of view of the participants this strategy, “emphasises meanings, experiences and description” (Naoum, 2013, p.41). It can be further broken down into two types of research, exploratory and attitudinal. Unlike quantitative research which tests a theory, qualitative is an inductive method, whereby the theory is emergent.

Exploratory research is used when there is a restricted amount of knowledge surrounding your topic area, it aims to highlight and generate, “a clear and precise statement of the recognised problem” (Naoum, 2013, p.42). Attitudinal research, “is used to subjectively evaluate the opinion, view or the perception of a person, towards a particular object” (Naoum, 2013, p.43). This method can often be time-consuming; it refers to the respondents' perception in their professional discipline and relies on the subjective interpretations of the researcher.

3.3.3 Quantitative vs. Qualitative Research

Amaratunga et al. (2002) suggest that there are no ideal solutions, each approach involves, “a series of compromises” (p.20) complimenting John Creswell’s (2013) thoughts, “that all methods have bias and weaknesses” (p.14). Though Johnson and Onwuegbuzie (2004) state that purists for each paradigm believe their approach is the most valuable for research and that the strategies, “should not be mixed” (p.14). However Onwuegbuzie and Leech (2005) contest this theory, suggesting that reliance on only, “one type of data is extremely limiting” (p.384)

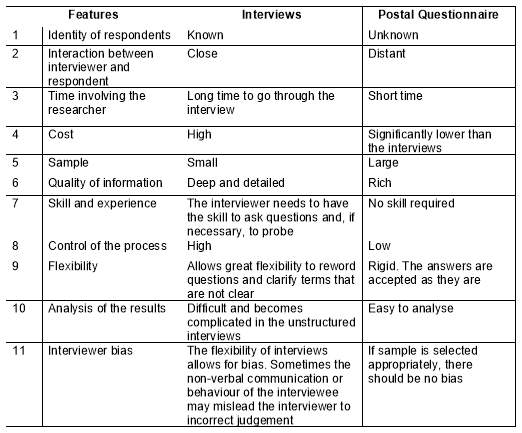

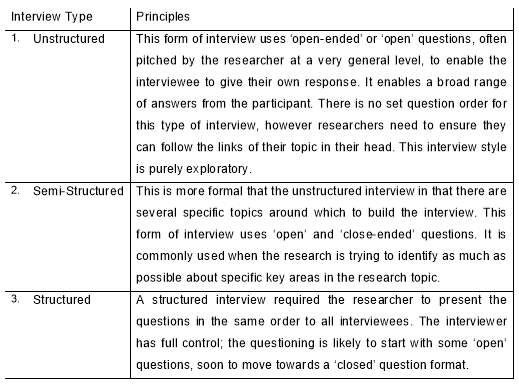

Triangulation, as the third research paradigm, could be seen to bridge the division between these two alternate approaches, by incorporating each of their strengths. Johnson and Onwuegbuzie (2004) state, “the bottom line is that research approaches should be mixed in ways that offer the best opportunities for answering important research questions” (p.16). Naoum (2013) identifies the main features of both a questionnaire survey and an interview, highlighting their strengths and weaknesses (see Table 3.1).

Table 3.1: Comparison between a postal survey and interview technique (adapted from Naoum, 2013, p.60)

3.3.4 Triangulated Research

Johnson and Onwuegbuzie (2004) depict triangulation as, “an expansive and creative form of research” (p.17). This mixed-method approach allows the researcher to, “reduce or eliminate disadvantages of each individual approach while gaining the advantages of each, and of the combination” (Fellows and Liu, 2015, p.29). This allows for a “multi-dimensional view of the subject, gained through synergy” (p.29).

Triangulation seeks to enrich the results and heighten the validity. Rossman and Wilson (1991) (cited in Amaratunga et al. 2002) discuss the benefits of combining both quantitative and qualitative research methods, suggesting it is, “to elaborate or develop analysis; providing richer details; to initiate new lines of thinking” (p.23). However, problems can occur when analysing the data if the findings contradict one another – which dataset has superiority?

Tashakkori and Teddlie (cited by Johnson and Turner, 2002) presented the “fundamental principle of mixed methods research” (p.299), whereby methods should strategically combine paradigms in a certain way to ensure complementary strengths are produced without any overlapping weaknesses.

3.3.5 Research Design

Research design concerns the way in which the researcher links their data collection to the research question; in order draw conclusions from it. Reliability and validity refer to, “the degree to which a researcher draws accurate conclusions” (Fellows and Liu, 2015, p.92) to reduce the possibility of inaccurate data. Precautions were therefore undertaken when planning the survey and interview questions, to remain unbiased. Triangulating the data sources allowed for, “convergence across qualitative and quantitative methods” (Creswell, 2013, p.15) to provide a means of examining the accuracy of the paradigms against one another.

The convergent parallel mixed methods model involves the researcher merging the data sets, “to provide a comprehensive analysis of the research problem” (p.15). Data is collected concurrently, and the findings are integrated into the analysis and conclusions, where incongruent results can be clarified. Fellows and Liu (2015) suggest that conclusions that concern both, “breadth and depth” (p.113), will have maximum validity. Figure 3.2 illustrates how the results from different data sources converge, to achieve breadth and depth.

Figure 3.2: Triangulation of Qualitative Data (Fellows and Liu, cited in Amaratunga et al., 2002, p.24)

3.4 Adopted Data Collection Methods and Justification

To achieve the aim, and meet the objectives (as illustrated in Figure 3.3), a triangulated data collection approach was determined to ensure valid data was obtained. Johnson and Turner (2002) recognise that each method of collection has limitations along with strengths and Tashakkori and Teddlie propose that their “fundamental principle of mixed methods research” (cited by Johnson and Turner, 2002) is followed for the subsequent reasons:

- “To obtain convergence or corroboration of findings;

- To eliminate or minimise key plausible alternative explanations for conclusions drawn from the research data, and

- To elucidate the divergent aspects of a phenomenon” (p.299).

Triangulation is able to achieve a much wider appraisal of the research data with greater depth as the researcher can ask a, “broader and more complete range of research questions because the researcher is not confined to a single method or approach” (Onwuegbuzie and Leech, 2005, p.21). Ultimately the investigator, “can provide stronger evidence for a conclusion through convergence and corroboration of findings” (p.21).

The mixed method approach will aid in formulating more in depth insights and conclusions, which may have been overlooked had there only been a single method used. Bazeley (cited in Ahmed, Opoku and Aziz, 2016) argues that mixed-method data compliments one another, “to offer a more comprehensive picture for the study” (p.40).

Figure 3.3: Illustration of Data Collection Methods to achieve the formulated objective

3.4.1 Questionnaires

Questionnaires are a data–gathering instrument, filled out by research participants. They are widely used to, “find out facts, opinions and views on what is happening” (Naoum, 2013, p.52). Naoum (2013) suggests that the three main advantages of questionnaires are economy, speed and consultation (p.52). Generally the bulk of responses will be, “received within 2 weeks” (Naoum, 2013, p.52), but a further couple of weeks needs to be allocated for follow-ups

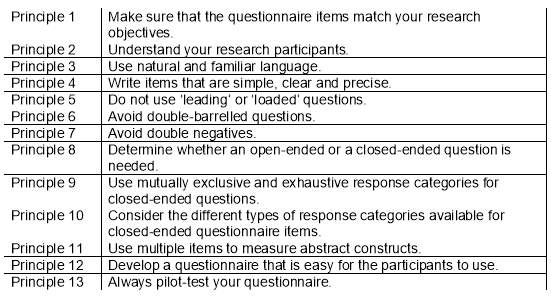

Questionnaires allow the participants to spend time consulting documents and potentially discussing with co-workers before finalising their answers, a luxury that is not offered when undertaking interviews, where answers must be given on the spot. Tashakkori and Teddlie (2002) suggest that when composing a questionnaire, “it is important to follow the 13 principles of questionnaire construction” (p.303) illustrated in Table 3.2. If the questions asked are well designed and precise the results produced should be, “valid and meaningful” (Mathers, Fox and Hunn, 2010, p.19), the questions must be, “self-contained and self-explanatory” (p.31).

Questionnaires are widely recognised as far more expedient than interviews, providing anonymity, which is likely to produce greater honesty. The length of the survey needs to be sensibly considered as the common nature leads to a concise amount of questions, which may overlook elements of required data.

Table 3.2: Principles of Questionnaire Construction (adapted from Tashakkori and Teddlie, 2002, p.303)

3.4.1.1 Formulating the Questionnaires

Gaps highlighted following the literature review prompted the focus points within the questions’ scope. Naoum (2013) identifies three significant phases which need to be considered when formulating a questionnaire:

- “Identifying the first thought questions;

- Formulating the final questionnaire, and

- Wording of questions” (p.64).

First thought questions are based on the literature review, they should not be arbitrary. By ensuring the research has been narrowed down to a specific focus area (section 3.2) it should help, “to formulate the final questionnaire more easily” (Naoum, 2013, p.64). Naoum (2013) suggests that following the initial identification of questions, “sections” (p.64) should be introduced to contain and organise the structure and list of questions. It is beneficial that these sections, “correspond” (p.64) with the objectives.

Finally, upon determining the scope of the questions, the wording needs to be analysed to avoid ambiguity and leading questions. A quantitative questionnaire was implemented which is a, “completely structured and closed-ended questionnaire” (Tashakkori and Teddlie, 2002, p.304) whereby, “all of the questions provide the possible responses from which the participant must select” (p.304).

However, there was an anomaly to this standard form as a single question was mixed. This allowed the participants to respond in their own words with an, “other (please specify)” category, if they believed the responses provided needed further explanation. A section of the questionnaire was a, “summated rating scale” (Tashakkori and Teddlie, 2002, p.304), a likert-scale. Likert-type or frequency scales use a fixed choice response format and they are designed to measure attitudes or opinions (Bowling, 1997; Burns, & Grove, 1997).

They consist of, “attitudinal statements on the survey object” (Naoum, 2013, p.74), which gives the respondent the opportunity to express their, “degree of agreement or disagreement on a particular scale” (p.72). The mode of distribution selected was an Internet based questionnaire. This provided both cost and time benefits, with secondary benefits for data analysis. The online instrument used was ‘Survey Monkey’, an easy to use survey builder that produced real time results. The data collected is generated and presented in statistical packages, readily available for analysis. “For online surveys in which there is no prior relationship with recipients, a response rate of between 20-30% is considered to be highly successful” (Surveymonkey.co.uk, 2017).

Following the sample selection, a covering email was issued to potential respondents, with the hyperlink attached, along with an introduction that clarified the context of the questionnaire. As suggested by Naoum (2013) (in section 3.4.1) a two-week period was stipulated for responses, with a follow up email issued after one week.

3.4.1.2 Pilot Study