The Work of the Film-music Composer After and Before the Digital Era

Info: 11133 words (45 pages) Dissertation

Published: 9th Dec 2019

Tagged: Film StudiesMusic

The work of the film-music composer after and before the digital era

INDEX OF CONTENTS

1.1. REASON AND MOTIVATION FOR THE WORK

1.2. QUESTIONS AND HYPOTHESIS ABOUT THE TOPIC

2.1. WHAT IS FILM MUSIC? DEFINITION AND GENERAL CHARACTERISTICS

2.3.3 The classical film (1935-1975)

2.3.4 Contemporary film (1975-2000)……………………..26

3. GENERAL CONCEPTS OF FILM SCORING

3.2. GENERAL STEPS ON FILM SCORING

4. FILM SCORING BEFORE THE DIGITAL ERA

4.1. CLASSICAL SCORES AND SONGS IN FILM MUSIC WITHOUT SYNCHRONISATION

4.2. ORIGINAL FILM MUSIC (SYNCH) AND THE HOLLYWOOD STYLE

4.3. SYNTHESIZERS AND ANALOGUE TECHNOLOGY IN FILM MUSIC

5. FILM SCORING IN THE DIGITAL ERA

5.2. THE NEW TOOLS OF THE FILM COMPOSER IN THE DIGITAL ERA

5.2.4 Plug-ins (Digital Emulators)

5.2.7 Orchestration and Music Preparation

5.3. INFLUENCES AND CONSEQUENCES OF DIGITAL TECHNOLOGY ON FILM SCORES

5.3.2 The “new” digital film scoring business

6.1. BEFORE AND AFTER THE DIGITAL: COMPARISON

7. BIBLIOGRAPHY AND FILMOGRAPHY

1.1. REASON AND MOTIVATION FOR THE WORK

The way of music making today have a large spectrum of possibilities. In our contemporary world, it is possible to compose music writing notes in a piece of paper –as since several centuries ago–, as well as create music from sounds in a computer or other electronic device, without even having a theoretical knowledge on music.

This fact is a consequence of the development of an aspect that has always been linked to humanity: technology.

Although many Music and Technology Studies have considered their processes as isolated issues, music and technology are without a doubt two topics that nowadays are indeed working with and for each other. Even the development of both music and technology is intertwined.

In particular, one of the areas of music that has been most affected by technology is film music. The way in which digital technology has come to the world has opened a large palette of new paths for musical creation and in particular in film scoring. Yet way before the digital era, technology changed film music continuously, as we will see in the chapter about history of film music.

Starting from these previous ideas, this thesis aims to cover two aspects: first, a description of how the work of film composers is; and second, an analysis of how the digital technology affects the musical creation for film, and how different has become film music since the emergence of the digital tools.

For the first point, I will discuss how are the main steps of film scoring, as well as how several composers have worked at different times in the last hundred years. In this way, we will be able to decipher what are the similarities and differences of the way they work. This is interesting for the students who want to learn how the film world works, in addition to how to compose music film with today’s available tools.

The second aim is to compare the film music of composers who have used the digital technology with which they have not used these media, and to observe the differences. In this way, I want to observe the impact of the technology, not just on the work of the composer, but also on the musical result. In short, how technology affects the composition and to film music as a result.

Music and technology have always been my two biggest passions. I have always tried to put them together. Since my musical career began, I have barely considered that technology could play such an important role in music making. However, during my studies in Media Composition I have learn that the possibilities that digital technology can bring to a composer are many, especially in a world where everything is increasingly digitized; and since one of the main areas of my composition studies (and interest) is film music, I wanted to connect both ideas and see how the film composer works, but also what have the digital technology have changed on the way film composers work and compose around the last century.

1.2. QUESTIONS AND HYPOTHESIS ABOUT THE TOPIC

It is a fact that technology changes the way of making and producing music. It has and has had a big influence on music composing since the beginning of the times. For example, the invention of different instruments has been crucial in the musical creative process. Most of musical pieces have been created considering the technical and acoustic possibilities of the instruments for which they have been composed.

Additionally, technological innovations, as for example the radio, allowed that certain music and music genres developed a bigger importance in the culture and in the society, which ad as a result an influence on music composing, since the amount of pop music written since the radio was invented increased exponentially in front of the called classical music and its tradition and avant-gardes.

The question that I want to address in this thesis is:

“Do the technological (and especially digital) tools affect film scoring, and change film music as a result?”

In case the answer to this question would be “yes”, the next question would be “how?”. In order to answer this question it is necessary to make an analysis of the subject before and after by contrast and analogy. In other words, in order to see what have change and how, we have to look to the similarities and the differences, and then to compare the work of the film music composer in both eras, with and without digital technology.

My hypothesis and therefore what I aim to show in this thesis is that technology changes the way we make music. The possibilities that technology gives us, is today almost infinite, or at least much greater than the possibilities we had before. The digital age has broken many limits that until then were unimaginable. But, has it been a factor that changed radically the music on films? I hope at the end of this thesis the reader will be able to answer to that question by him- herself.

Film music is one of the central objects of this thesis, and for this reason before going deeper into the main focus it is important to clarify questions what is it, how it works, what function it has, and a summary of its history, with the aim of achieving a better understanding of the subject in the 21st century through its past.

2.1. WHAT IS FILM MUSIC? DEFINITION AND GENERAL CHARACTERISTICS

Film music, today also known as Film Score, is all music created or related to accompany a film. The score is one of three sound elements that can be found in a film, along with dialogs and sound effects.

The main purpose of film music is to enhance the narrative of the film. The score has become nowadays one of the most important elements in a film production, and it is hard to imagine today a movie without any associated music at all.

Film music can be understood as every music contained in the film, but for this work, I focus the term of film music as the original score (or original soundtrack) specially composed for a specific film.

Other songs or music pieces included in a film which are not composed and produced specifically for it are sometimes considered as a part of the soundtrack, but not as original film music itself, rather adapted music, because they were not created along with the movie.

Another important general line to point at is that the score of a film has no defined associated style, which means that, although it is usually associated with orchestral and strings sound in a western classical/romantic music style, every kind of music -including jazz, pop, rock, electronic, contemporary, concrete music, or soundscapes- can be suitable for a film. This means that film music must not be considered a genre of music, as many people believe, but rather as any kind of music composed for serving a film as a purpose.

As already mentioned, the main function of film music is to accompany, or enhance the action in a movie. More specifically film music can fulfil, among others, the following functions:

- Set a story at a specific time and place. If the action happen in the early 20th century or in a modern futuristic world, the music usually reflects it. The same way happens if the action occurs in a big city or in a South-American jungle.

- Contribute to the development of the psychological element in the characters. In addition of enhancing their feelings, music can help to let the spectator know the personality of the characters.

- Serve as background for the dialogues and give them a point of sentimentality, dramatization, etc. or replace those that are unnecessary. For example, in a typical love scene, when the protagonists meet and begin to have a conversation, we usually listen to a suitable romantic music for the scene.

- Join scenes that without music would be difficult to connect.

- Make some scenes clearer and more accessible. Music helps the spectator to receive clearly the intention that the director wants in a scene or action.

- Involve the viewer emotionally. Music can influence the feelings and emotions that the viewer experiences throughout the film, changing the sense of the image or anticipating a particular situation, as, for instance, in the famous shower scene in the movie “Psycho” (Hitchcock, 1960).

In other forms of analysis, the functions of film music have been divided into 3 groups: formal, narrative and emotional (Flach, 2012, p.23-28).

Music’s formal functions refers to their structural employment, that is, their function is to clarify the elements of the film, for example to divide sequences, e.g. one scene finishes with a certain music, and a new different music starts, making out clear to the audience a contrast between the previous scene and the new one. “If a film is organized in several acts, a common way to structure a film, music is likely to underscore the transition from one act to the next” (Flach, 2012). Another typical formal function of the music in a film is during the opening titles, where the music often engages us into the universe of the film.

The second function of music is the narrative. Music, although often has no concrete meaning that we could explain in words, almost always creates certain associations and suggests things to the listener. Music has indeed very often a semantic dimension. In this way, when we listen to a specific music, our mind is automatically and sometimes unconsciously transported into a determined universe. These premises often coincide with the universe of narration in a film. For example is a scene begins with some taiko drums and a gong, the audience probably will expect to find the story in China (or other Eastern countries), and maybe even in an older time. This proves that music narrates to us also a story (or part of it).

And finally the music’s emotional function is probably one of the reasons of why music has been so useful and meaningful in films. Its capacity to evoke emotions in the works as a tool of engagement for the audience and at the same time enhances the power of the dramaturgy.

Some authors, such Cohen (2010, p.880) points a distinction between mood, which is an emotional atmosphere, and emotion, which has a specific object or subject related; while Michel Chion (1997) remarks a difference between empathetic music and anempathetic music. Empathetic music is the one directly connected with the suggested emotion of the scene: pain, worry, love, etc. While anempathetic music creates the opposite effect: it is a music which does not logically belong to the scene, and therefore creates a different emotional effect (e.g. terror scenes accompanied by children’s music).

By its application, film music can be also presented in three different forms:

- Diegetic music: It is the music that we find inside a scene and that arises from elements present in it, like a radio, a television… They are heard by the characters and it is very useful to convey feelings. For example, during a dancing scene in the eighties, the music that the orchestra plays is an example of diegetic music. Several scenes from the film “Amadeus” (Forman. 1984) are good examples of diegetic music.

- Non-diegetic (or incidental) music: It is the music that only the spectator can hear. The characters of the film cannot listen to this music. Its function is to create a special atmosphere and to express and/or enhance what the characters, through words or acts, cannot transfer us. (Chion, 1997)

- In his book, Scoring for films (1971), Earle Hagen suggests a third category called “Source Scoring”, which would be a mix of both diegetic and non-diegetic. This is a rare case in films, but an example would be if during the scene an orchestra is playing a music, which can be heard by the characters, but at the same time accompany the dramaturgy of the scene.

Finally, the function of film music, in communicative terms, can be necessary music, when this music is necessary to give an important information to the public in order to facilitate the association with an action, place or event (e.g. Tango music during a views of Buenos Aires); but it can also be creative music, where is not so necessary, but optional, and usually its communication with the spectator is more emotional than intellectual.

The history of film music can only be understood along with the history of film itself. Through a historical vision of how music became part of the world of film and examining chronologically how, we will be able to understand how film music and the role of its composers has evolved over time until reaching the digital age.

The history of film begins on the 28th of December in 1895, when the Lumière brothers publicly projected the departure of workers from a French factory in Lyon, the demolition of a wall, the arrival of a train, and a boat leaving the port.

The success of this invention was immediate, not only in France, but also throughout Europe and North America. In a year, the Lumière brothers created more than 500 films. There was characterised by the absence of actors and also by the use of natural decorations. They were also very brief, and the camera had always a fixed position.

First films were only short, until 20 minutes –the feature film did not appear until the decade of 1910–. They were not a narration as we are used nowadays, but rather a sequence of animated postcards, reconstruction of an actuality event, etc. At the time it became “lineal”, it was just as a consequence of the junction of autonomous sequences.

There were no cinemas of specific places for film projections, so that theaters were adapted for that purpose instead. Orchestras, instrumental ensembles and soloists working for those theaters became the first performers of film music.

In 1895 the Phonograph —a previous prototype of a gramophone, able to record and reproduce sound mechanically invented in 1877— and the Kinetoscope —first motion picture device— were already invented but yet they were not used together because there was no synchronisation between the film and the sound (cylinder or disc), the reproduction of instrumental sounds was not so good, there was no electronic amplification yet, and musicians at that time were cheap and highly available. All this favoured a live performed film music with rather an approximated or even random synchronization.

Live music which accompanied films looked for reflecting the “clima” or atmosphere of the scene and stimulate more intensively the emotions of the spectator. Another role of this music was promoting the film. And it even fulfilled the function of attenuating other sounds or noises external to the film (such as the projector, for example).

At that time, it was characteristic of this early film music, that every country used its traditional music and spectacles to accompany their films. For example in Italy the live film music used a lot of music (from the opera tradition), while in France they used to be very brief (as in French theater tradition). In Japan they combined music and comments. Film music was also, as the film itself, sequential.

The music performed by musicians in the pit was provided from three different sources (Chion, 2008a):

- Pieces of pre-existing works arranged for the occasion. Usually there were included some fashion popular songs (this last only until the decade of 10, decade in which the copyright laws for musical works was stipulated). The conductors and performers reconstituted suites from different pieces of works by Beethoven, Mozart, Brahms, etc., to which were added tangos, rag times and ballads, all pieces of taste and knowledge of the public. This usually constituted a fixed repertoire for each performer or orchestra group, which had many advantages (less rehearsals, etc.).

- With the establishment of the authors’ rights laws, the cue sheets started to be a standard in the U.S.A. Each Hall had their own library of cue sheets, subtitled by categories such as following: love themes, exotic atmospheres, funny atmospheres, comedy, nature, battle, tragedy, consequences of a tragedy, young characters, old characters, good characters, bad characters, death, light, neutral…

- Original music for films already existed at that time, but it was the less common alternative at that time. This music was composed usually for orchestra. It was not the most economical profitable, because the production had to pay to the composer and the orchestra (which had to do more rehearsals for the new pieces). Additionally, playing new music brought more risks for the performance. Some of the composers who composed music for film at that time were well-known names from classical music: Erik Satie in “Entr’acte” (Clair, 1924); Paul Hindemith in “Vormittagsspuk” (Richter, 1928); Darius Milhaud in “L’Inhumaine” (Marcel L’Herbier , 1925); Sergey Prokofiev in “Lieutenant Kijé” (Faintzimmer, 1932); Edmund Meisel in “The New Babylon” (Kozintzev-Trauberg, 1929); or Dmitri Shostakovich in “Battleship Potemkin” (Eisenstein, 1925).

Film music of this period had not stylistically an own aesthetic. Both popular and classical music coexisted, subjected to the fluctuation of popular taste, the evolution of cinema and, of course, copyright laws. This tradition was so standard and strong that one of the first partially-spoken feature films, “The Jazz Singer” (Crosland, 1927), included the music of Tchaikovsky and Lalo along with jazz songs and little musical pieces by unknown artists. It is important to highlight that in that period the expansion of popular music —thanks to the radio— was rapidly increasing, and also there was an evolution of classical music towards the popular (Group of Six).

Another common practice was to integrate singers or musicians onto the stage, singing or playing together with the accompaniment in the pit. There are only few films that do not include any scene of popular dance, ballet, concert, circus number, songs, etc.

With the emergence of the audio-visual synchronism, film had to establish a speed of recording and reading of images, which transformed the cinematographic art from fixed movements to a chronographic art (fixed times). This resulted in the birth of the absolute temporal values —now known as Timecode—. In other words, a new film with stabilized speed and an amplified and synchronised sound. The material causes of this development are found in the invention of electrical amplification, and the continuous improvement of sound recording procedures. The following list specifies the best known procedures of the time:

- Sound on Disc: Used by the Warner for feature films, quickly left aside because of its discomfort.

- Sound on Film: Invented by the North American Lee Forrest; it inscribed the sound on a punched tape, allowing its assembly easily.

- Fox Case System: Invented by William Fox, a variation of Sound on Film.

- Vitaphone: It begins to be used in 1926, and starts, according to William H. Hays, president of Motion Picture Producers and Distributors of America, “… a new era in music and in film”. The system was based on the electric amplification of discs, read by platters electrically synchronized by both the camera and the projector.

For our current audiovision, there are great problems of synchronization and the origin of the listener in these procedures. However, given the non-obviousness of these resources at that time, these problems were apparently not perceived. Still, composers like Milhaud criticized the mediocre reproduction of sounds in movie theaters (Chion, 1997).

Music had to redefine its role in the cinema, not only because it was now present in a single concrete and recorded form, but also because it had to find its place with dialogues and noises, which now had the possibility of really listening. Music auditions were reserved for visually justified sequences and for the timely efforts to transport forms of musical theater such as operetta and comic opera to a cinematographic space.

The transition from silent movies to a film with audio-visual synchronization was not instantaneous. The transformation was as fast as the political – economic – geographical situation of each country allowed. The fastest transformation took place in the U.S.A. (however, in the large rooms it was continued playing with orchestra).

Some of the new stylistic elements were as follows:

Between the end of the twenties and the beginning of the thirties there was a great peak of films about singers, just at the same time that radio and records experimented an intense grown. Many of the scripts commonly spoke of a normal guy with a hidden special vocal talent, who represents the American dream: someone who can improve his or her social status through his or her talent. This tradition will continue until the mid-sixties.

Also appeared the pulsed noise, the melody of noises and the Silly Symphonies: In the USA, and ahead from the birth of the concrete music —a form of experimental music based on the treatment and manipulation of certain isolated sounds in combination with others—, many films emerged with rhythms made with noises as an expression of “modern rhythms”. They even engaged in metaphors such as “City Symphonies”, “Nature Orchestras”, etc. On the other hand, in Europe, the concept of “World Melody”, which gave a rhythmic-melodic order to a sequence of noises, was composed in a more sophisticated and intellectual way.

Finally, cartoons played at the time an important role from this point of view, because virtually everything could be transformed into a musical instrument, the musical parameters could be applied to no matter what sound object. It was the time of the Silly Symphonies (Fig 2.1), and many of them illustrate the conflict between jazz and classical music, for example in the “Music Wars” (a kind of adaptation between a Romeo-sax and a Juliet-harp, which ends, after an intricate and musical combat, with peace between the realms of jazz and classical music).

Fig. 2.1 – Silly Symphony

2.3.3 The classical film (1935-1975)

After the first experimental period, we arrive at a stable and standard model, a formula in which musical inputs and outputs will be admirably organized to never lose the sense of continuity. Music will become a bridge between the words and physical actions.

A music made to cohabit with the dialogues should adopt a more fused, obedient style, and for that, the Wagnerian instrumental recitative was the model to follow. The element of popular music, according to Chion (1997), will no longer be linked to that healthy vitality of the past period, but will represent vulgar, trivial, profit, etc.

If music in the pre-classical period was characterized by the assembling (beautifully) of different pieces or sequences -discontinuity-, the classical period will admirably organize its inputs and outputs with an important function: never losing the sense of continuity.

In her book “Unheard Melodies” (Gorbman, 1988), Claudia Gorbman explains some of the criteria and characteristics of the film music in classical cinema:

Invisibility of music production devices: Just as the cameras are not shown, neither instruments nor singers are shown, unless they come from the scene. It is accepted, for example, violins playing in a love scene, but not in the recording room, nor their breathing noises, return of score, etc. (e.g.: In King Kong, a tribe loves the gorilla, they hear and see percussionists and singers, but it is accompanied by an invisible orchestra).

Inaudibility of music: Music shouldn’t be consciously heard; is thought as an accompaniment of actions and dialogues, placing the latter in a higher hierarchy. To subordinate music to narration, there are certain stylistic parameters to respect:

- Little musical motifs.

- Percussions not defined rhythmically.

- Chords that keep going through time.

- Tremolos and pizzicatos on strings.

- Form of recitative.

Music as emotions interpreter: Will be engaged in scenes of objectivity will disappear in scenes of greater objectivity

Narrative Cueing: Music marks the narrative. There are 2 semiotic categories in the classical film:

- Music sends the viewer to the limits of the narration (accompaniment).

- The music emphasizes, accuses, points (e.g., beginning and end of a sequence; characterization of a time, place, culture; points of view of the characters).

- Illustration function of the music, chasing the latter second to second to the action (mickey-mousing effect). It is preferred the impression of the illustrated, to the illustration itself (e.g.: it is preferred a music that illustrates the sea, that the noise of the sea itself).

Music as a continuity factor: Music fuses the discontinuities of the montage (ellipsis of time, change of space, etc.)

Music as a factor of unity: Music should contribute to the unity of the whole film through a set of themes repeated variously or not; and through a global orchestral color.

We can find some examples of film music in classical cinema in the following movies:

- In “Casablanca” (Curtiz, 1942) music takes over the narrative entirely: it locates the geographical place (exotic music), the historical place (sombre music for the images of the exodus of Paris), the punctual decoration (musical environment of oriental villa when the action begins), etc. Below, two quotes from this film:

- A German from the occupying forces communicates by loudspeaker the prohibition of leaving the city under pain of death. This is preceded by an orchestral rendezvous at the beginning of the hymn “Deutschland über alles”, which stops at the discourse, leaving under the words a tremolo effect imitating the military marching band. This holds the tension, and gives the context of doom.

- In the following scene, a member of the French resistance tries to escape from the police of Vichy. The music describes his effort with hurried times and quick notes. When he pauses in a small dialogue, in which the police check his papers, the orchestra discreetly maintains a tremolo in the low ropes, giving space to the words (mid-high register). Little by little, a musical motif begins to make its way from the low register to the middle, anticipating what will happen: you will find that the papers are false. The resistance member returns to escape (ad-hoc music, similar to the first one), until it is shot down.

- Another example are some “The Public Enemy” (Wellman, 1934) scenes:

- On a musical background the actors pose and look at the camera, identified by the name and the character they embody. This comes from a radio genre of the time, where credits were usually listed on a musical background (“Citizen Kane”, 1941, was made with the same spirit, as retro effect, alluding to this period of both cinema and Radio).

- Then there is a fanfare that is visually justified with a hornet playing. Music will no longer come from the pit (outside time and space), but will be linked to concrete times and spaces determined by action.

- Like other gangster films of the time, this is also a retrospective type (recounting possible facts only 20 years ago). This needs to be strengthened musically (for the public to recognize the music and place it in time). In this movie, a mechanical piano with a rag-time (ten years old) is heard in a cafe. It has nothing to do with the purposes that the gangsters plan in the cafe, however, the musical cadence coincides with the end of the sequence.

- To symbolize a temporal ellipsis, the orchestra music of a restaurant goes in fade out (along with a visual fade in black), and it replaces a solo piano music, while the image returns to the same place.

- The music also contributes to the passage between sequences. A romantic scene, accompanied by orchestra music from the radio, cadence synchronously to the opening of a door by a gangster, which announces to the hero bad news.

- Music begins to tell the facts by itself. In the movie, the hero and his accomplice visit a character to kill him. The latter reminds them of a song that sang to them as children, accompanying themselves to the piano, first with a voice weak by fear, but then more certain. The camera rotates from left to right and arrives at the passive accomplice, while the song is still heard (which in all of this evokes memories of childhood to the spectators of 1931). Symbolically on the word broken, a shot is heard, interrupting the song with random notes and agonizing moans.

- In the end, when the hero dies, the music (waltz) does not go to the cadence until the word “The End” appears on the screen.

In conclusion, we can say that, from music, the elements of interruption are justified realistically, related to shocks, bullets, etc. The elements of continuity are those that are justified either by a mechanical support (turntable, pianola, etc.) or with musical pieces indifferent to the story.

During the Fifties and the Sixties, the “classic formula” still worked perfectly but some element of the new age were added:

At the end of the second war television war born. This meant for film a search for differentiation, which will result in:

- The film will go on the street in search of action (it will not stay, as it has until now, in the studio).

- The characters will have greater psychological versatility. The subjects will be chosen and treated more freely (sex, drugs, violence, freedom lost in the thirties, etc.)

- The concept of film-show (systems such as cinemascope, of colors and more defined images emphasized the existence of color images versus the television system that was black and white)

- For the first time more specific audiences are sought. Do not forget that in the USA Young people have greater purchasing power in this era, a product of part-time jobs (a situation that will trigger, among other things, the birth of rock’n roll in this country). Taking advantage of this, the American film will look for themes that identify them. The rock begins to occupy, and as a consequence it revitalizes the use of the form song in the film.

In Europe, the trend of the vanguard will be to occupy a jazz also avant-garde. Hard Bop, Cool and experimental tendencies will be on the order of the day (versus the old Swing and Standards of North American movies). Clear example of this is the film “Knife to the Water”, with music of the saxophonist John Coltrane.

As a consequence of the above points, the great orchestra is no longer used preponderantly, to give way to more varied coloraturas.

Another leading European factor is found in directors such as Giovanni Fusco; The latter imposes its criterion of economy of means, whether in the musical object itself (color, texture, etc.) or in expressiveness itself (music subtly expressive). It is in these films that the conscious idea of counterpoint music – image is born. A clear example of this is the film “Il Grido” (Antonioni-Fusco), in which, in scenes of sadness, small pieces of piano are heard, without much connection and not very expressive. In directors like Buñuel, it will be sought to avoid exacerbated emotions and precipitations of meanings; The music always runs the risk of provoking these phenomena, so it is limited in its interventions.

2.3.4 Contemporary film (1975-2000)

Until 1975, high fidelity was a class privilege: Only cinemas were equipped with multi-track (and obviously, with special copies), with which a good sound definition could be reached. In 1975 the Dolby Stereo was born. This contributes to greater color richness (better definition in both bass and treble) and dynamic (by eliminating noise) for all. This will be complemented later with the invention of Dolby Sorround, which will especially expand the music and noise bands. The advances of the Dolby Stereo materialize in the following points:

In the treble, the optical sound reached 8000 Hz of definition. The Dolby allowed to reach the 12,000 Hz of definition. Sounds, and particularly those of musical instruments, are transmitted in a much more precise way, because the accompanying harmonic sounds are also heard.

The Lows also acquire a new presence, reason why it begins to take importance in the musicalisations (it is committed corporal to the auditor)

The system allows a great dynamic sensitivity.

Because the system has the power to divide the sound into several independent tracks, it can be distributed and occupy the sound space.

Due to the definition of the sound, both musical and dialogues and noises, it allows to finish the historical fight between them, acquiring great and unpublished own spaces to develop.

Musical films such as “Amadeus” (1984, Milos Forman), “Every Morning in the World” (1991, Alain Corneau), Farinelli (1994, Gérard Corbiau) are totally linked to these new possibilities. This will be complemented later with the invention of Dolby Surround that will spatially expand musical and noise bands.

In contrast to the above, a taste for a nostalgic retro is born at all levels. In U.S.A. Is returned to the color of the great orchestra. It is also returned to old fashions (the twenties, thirties, and fifties). For example, in “Manhattan”, music from Gershwin is superimposed on the image of contemporary New York. In “Cotton Club”, film in the celebrated night club of Harlem, in the decade of the thirty, is heard ad-hoc music (Duke Ellington works), with orchestration of the time (beginnings of the Swing), but with a sound (Record). In “Apocalypse Now” you can hear popular songs from the time of the action, which could even have been broadcast on radio stations dedicated to the military (Walter Murch sounds an impressive opening with the theme “The End” from the group Psychedelic of Los Angeles “The Doors”).

In “American Graffiti” a compilation of songs from a decade ago is heard, with the aim of situating the spectator at that time, but also in order to obtain a sort of musical dust that is present in the global sound, creating an effect Overlapping free of words versus music; To the units of time and space, you will then add a kind of “radio station unit”. All these ideas will be developed later with the name of music on air. This technique consists of applying a piece of music (usually pop music) on images and / or situations to which it is not completely synchronous. This, which could be read as negligent overlapping, is not such; We are consciously looking for an effect of dispersion of attention, reflecting the same type of random overlap that in our day causes portable radio, car radio, background music in commercial premises, supermarkets, etc. For example, in the movie “Thelma & Louis” there is a scene where they stop at a motel to rest. Thelma goes to the pool while Louis calls a friend. Both sequences go in parallel assembly. Affirming itself slowly (Fade in very slow), a song is heard; By the discretion with which it is heard at the beginning, seems more coming from the action than from the pit (however, it is heard on both sides of the phone, the conversation is distanced by a good amount of kilometers, so it is difficult to think – Especially in the USA – that is the same radio station). In any case, it imposes its own pace and its own development, regardless of the facts. Follow a plane of Thelma in swimsuit, with a personal stereo. The music rises synchronously in volume, so it gives the feeling that the staff is the sound source. Louis, who had decided to leave, the flame, she does not listen, so he is forced to remove the hearing aids. However, music does not stop, but, on the contrary, it rises more volume, affirming itself as pit music (none of the three characters alludes to the subject, which would have been enough to place the song in action).

The film – catastrophe is born, as a kind of return (very commercial) to the epic film (“Airport”, “Hell in the Tower”, “Tiburón”). It is born precisely in an age of anti-heroes, of political criticism, and of various treatments of the everyday world.

A new concept of pit music is also born; The new narrative role will not be discreet, but will relate to the recurring themes of the Verdian opera (in which each theme represented a character or feeling). A clear example of this new pit is found in the films musicalized by John Williams, and particularly important is from this point of view the film “Star Wars”, in which there are themes for the characters, for situations, for symbols, for ideals, for places, etc. Also interesting is the use not only of an overture, but of an end, making in it a summary of the main themes, lengthening the final holiday.

Another novel aspect from the point of view of coloratura (but not of language) is the use of the synthesizer. It begins to occupy like orchestra in movies of low budget, but of little composers like Vangelis and Hans Zimmer place the synthesizer in a category a little more interesting.

3. GENERAL CONCEPTS OF FILM SCORING

Film scoring is the common designation associated to the work of the film composer. The film composer is the person designated to compose the music for a movie. Sometimes composers work alone but recently the biggest productions have a whole team working in the score of the movie. However it is still the name of the main film composer on the credits, because is the person who does the most creative work, meaning the musical ideas.

The production of a film can be initiative of a single person (director, screenwriter, producer), or of a group (investors, big film production companies) that look for people capable of writing a story that may have interest and generate income, and a team that is capable of making a good film with it (Davis, 1999: 69f). We usually differentiate between commercial films and independent (or non-commercial) films. Independent films are those produced outside of the biggest film studios, and which their main purpose isn’t, opposite to commercial, to generate income, but rather to explore news ways to filmmaking. In this context, the composer’s work is also affected by this difference. In the independent films, the objective of the music sometimes escapes the general lines that we have mentioned about film music previously. Also the budget, which is usually smaller in independent productions, makes the process and the phases of creating a soundtrack different. In this thesis we are focusing on productions in the style of Hollywood, since the composers to analyse have developed their careers around this large film industry and further reasons explained in the introduction.

Still, talking about music strictly, it has no repercussions. A score for large production may also be valid for independent production. Notes and silences do not distinguish budgets.

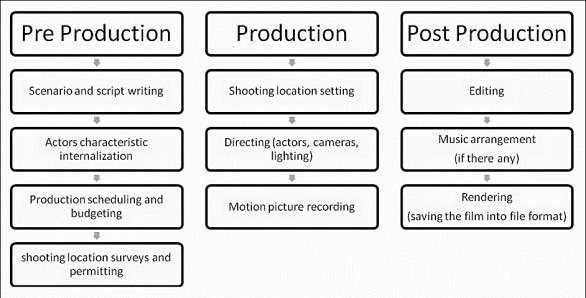

The process of filmmaking usually is divided in three different phases: pre-production, production, and post-production (Davis, 1999: 74f).

During the phase of pre-production, the producers have to organize all the matters required for the later production and post-production. This includes especially conceiving the idea, financing, casting, hiring, writing the final screenplay, scheduling, scouting locations for the shooting and all organizational matters. During this phase, the producer (or producers) of the film is who hires the composer. Then, an agreement about legal, monetary, royalties and timing matters must be set.

After it, the phase of production of the film begins. In this phase is where the filming process takes place. This means, setting the scenarios, rehearsing and shooting the scenes with actors, recording dialogs, etc. Also during the production phase begin to take place tasks as editing, special effects, animation and similar.

The post-production phase begins when all the material is shot, and the main work is focused in an advanced phase of editing and assembling, including color corrections, cuts, audio post-production, sound design and music.

Fig. 3.1 – Film Production Stages

Fig. 3.1 – Film Production Stages

3.2. GENERAL STEPS ON FILM SCORING

Generally the composer is hired during the pre-production phase. However, before that happens, he must have a meeting with the filmmakers. In this meeting, the director and the producer talk with the composer about the movie and its musical needs. Sometimes other members of the crew, such as the music editor or the music supervisor, attend the meeting too. The composer usually knows already a general idea of the film, and probably he has gotten also the script of the movie.

The economic terms are also one of the important points to discuss. The producer has to suggest or agree with the composer a budget dedicated to music, depending on the needs of the film. It is necessary to take into account factors such as how many minutes of music will have approximately – this is defined more concretely during the spotting, if it will be possible to hire orchestrators or other helpers, if it is necessary to make recording sessions, if so, how many musicians can pay, etc. For example, it may happen that the composer cannot compose for orchestra because the budget of the film does not allow to hire so many musicians. Then the composer must be creative when it comes to creating a film music that does not lose quality whatever the economic conditions. Obviously it is much easier when the producer is open to listen to the needs of the composer after the spotting session.

Equally important is to define a work schedule, where the timing required for each activity must be determined, as usually there is not much time to make the music. After all the mentioned steps are agreed by both film production and film composer, they can start the legal processes to hire the composer.

From that point, the composer can start to gather ideas, share them with the director, get feedback, etc. Usually the film composer starts to compose some sketches or demo cues[1] during the production process, so that he can start to sketch ideas for the film and think about melodies or sounds associated to characters and locations, and a first look on the spotting.

However, most of work of the film composer usually begins during the later post-production phase, when the movie is completely assembled or in a very advanced phase. The reason is that usually the composer needs a “locked”[2] version of the film in order to do the spotting, and to think about synchronization between music and pictures, and this is usually only possible after almost all film editing post-production.

If the composer would be contacted and hired in a later phase of the film production and the film would be already edited and assembled, the director would give a copy to the composer to start getting familiar with the project. This happens often in amateur or low-budget productions, but it must not be considered as a common practice into the professional world of filmmaking and film scoring.

The spotting session is the task where the composer and the director (and also sometimes some relevant persons of the production such for example the producer, the music editor…) work together to set up where in the movie will be music and what will it sound like. This is the first serious task of film scoring for the composer but without a doubt one of the most important. Placing the music in wrong places or compose a music that does not fit the picture at all can ruin a whole film.

In his book, Davis (1999: 90f) gives three keys that every film composer should consider during the spotting session:

- Music is a part of a mixed media production. The music must accompany the movie, not be all the time the most important and interesting part of the film. A very good film music is created when all parts of the movie (picture, sound design, dialogues…) work well together.

- Music is not always needed. The film composer must think that music have to enhance the picture and the dramaturgy. If there’s a music sounding all the time, maybe it doesn’t impact in the same way when a certain scene comes. The dramatic needs must lead the spotting.

- In the points where music is needed, the film composer must think about the exact point where it has to start and when it has to end, and more important, think about what this music has to say, and how to say it according to the picture and to the story that the spectator will see.

The communication between the director and the composer is one of the keys of a good spotting. The director is the person who knows the dramatic intention of every scene and picture in the film better. Additionally, the director always has the power to accept or reject a music, or to make suggestions to the composer, since he is ultimately responsible for the film as a complete work. Therefore, the composer must be able to understand the wishes and needs of the director as accurate as possible, in order to make a music that fits the motion picture as best as possible, and also to save time, since every composed cue that is rejected must be modified or totally recomposed from the beginning.

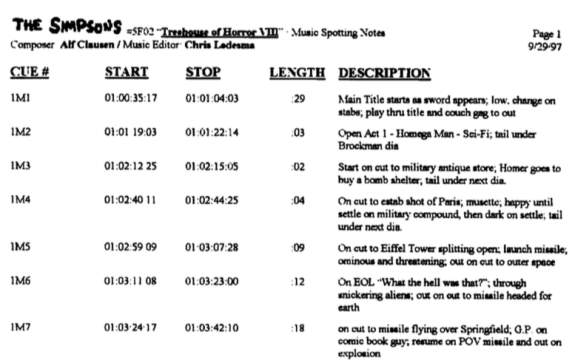

As a result of the spotting session, the composer (or music editor, if there’s one in the crew) should have taken notes and transform them into a cue sheet.

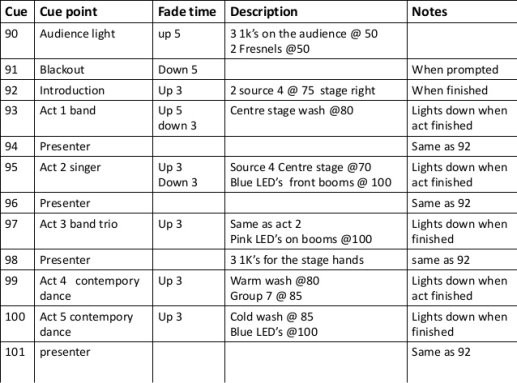

A cue sheet is a document which lists all the music used in a film and relevant information about each cue. I distinguish between two types of cue sheets:

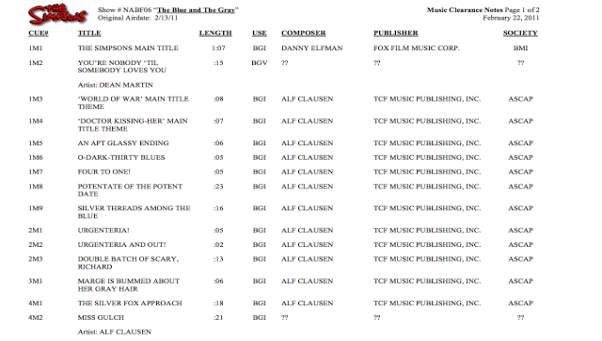

The first, the composer’s cue shit or cue list, is the one resulting of the spotting, in which the composer or music editor have taken notes of the points where the music starts, when the music ends, notes about the scene, notes about dramatic intention of the music and maybe even first suggestions about the instrumentation and for the composition. It is this cue sheet that will accompany the composer during the composition process. As an examples we can see Fig. 3.2 and Fig. 3.3.

Fig. 3.2 – Example of a Spotting Notes from “The Simpson”.[3]

Fig. 3.3 – Example of cue list.

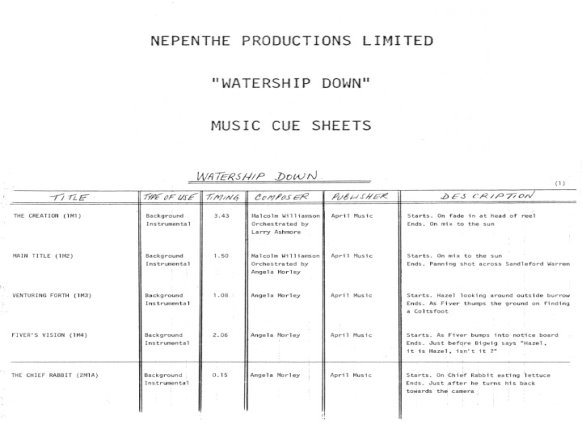

The second, the official cue sheet, is just a simple document with information about the music works used in a film. It contains most of information of the composer’s cue sheet (especially about the timing and duration of the cues), but also contains the information about other possible musical pieces that may be included in the film. Its function is to ensure that part of the rights that television companies, cinemas, hotels and other organizations pay annually to the management companies go to the correct author or publisher. We can see two examples in Fig. 3.4 and 3.5.

Fig. 3.4 – Example of an official cue sheet from The Simpson.[4]

Another topic to take in account during or after the spotting and directly previous to the composition process is the conceptualization (Olaya Maldonado, 2009). In order to achieve a unified music and justified, it is necessary that the composer makes approaches such as:

- What kind of music does the film require?

- What characters, actions or objects need music?

- What function has every cue (diegetic, incidental, empathic, etc.)?

- What is the proper instrumentation?

- How many synchronization points are there?

- What is the rhythm and time of the images?

- How to properly distribute music, how many central and secondary themes?

Answering these and many other questions, the composer will be able to determine the parameters of his composition and thus generate a unified concept for his score.

Fig. 3.5 – Example of a Cue Sheet of composer Angela Morley[5]

In the central stage is where the main musical creative process takes place. After all phases described on the first stage, the composer begins the composition process, which is a very personal activity, carried out by the composer alone. First of all, the composer has to define the musical structure for every musical moment in the film. Film music, usually, is constructed from musical themes or fragments that behave according to parameters (narrative, technical, dramatic, etc.) that determine the film. These Themes can be organized as following (Olaya Maldonado, 2009):

- Main titles: Is the music that accompanies the opening credits, which often can introduce melodies that will be used and developed in the film.

- Credits: music of the final credits. Often songs from other artists are used on them.

- Central Themes and Main Theme: They both are the most important, dramatically speaking. Central Themes highlight an important event, place or character in the film. The Main Theme is the one that especially highlights over the rest of central themes.

- Secondary Themes: Is music used above all for ambient. It has not so much dramatic potential as the central themes and it is not created for the spectator to remember it.

- Subtheme: Is a theme of a fragment of a theme inserted inside another dominant theme, working as a subtheme of the dominant one.

- Leitmotif: It is a theme, musical fragment or sound, which create a reference and an association with a certain character (or situation). In this way, every time that this character appears, that leitmotif or a variation of it appears too (e.g. Star Wars Leia’s Theme).

Once determined what kind of function has every cue into the whole film, the composer can decide from which one he wants to start to work. Once some sketches for a cue are composed, the composer must think about synchronisation with the pictures, with time signature or tempo changes, and development of some motif. It is important, especially if the music has to be, to make clear synchronisation points. During the composition phase, the composer can already start to think about the orchestration, which kind of instruments he wants to use in order to create an specific sound. However, usually the final orchestration is not made until the whole cue is composed and synchronised.

About synchronisation, there are several methods to adjust a score and generate the sensation of synchronization between music and image. The composer is free to choose which of these procedures while composing. First you have to look at the scene several times in order to determine a tempo and evaluate all possible ways to reach Sync Points. Then, with the help of spotting‘s notes, define the proper qualities of the music in those points and the function (dramatic, technical or psychological) that must be achieved. It is important that the cue does not lose meaning when it reaches a Sync Point, that is, it does not sound like a “patch” over the image, but instead is logical and justified.

Synchronization is important for two moments of the process: composing and recording.

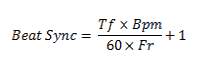

In the first, the composer does not have many options; there is an equation where once the tempo (Bpm) of the cue has been determined, the beat on which the synchronization happens (Beat Sync) is searched. It does exist an equation to calculate that:

(Tf = Total frame) (Fr = Frames) (Bpm = beats per minute)

This formula is especially effective to create a very precise Synchronisation Points, or for effects such as Mickey-mousing. However, still today many composer prefer to adjust the synchronisation by “eye” and “ear”, in a way that they look and sound natural for them.

The second moment is about the timing when recording. Before the session, the composer or music editor generates a click that is known as a click track[6], which serves as a reference. The first method of synchronization (perhaps the most used) is known as Punch and Streamer; Is to place a white dot (punch) on the picture where the action happens[7]; As it is necessary to prepare the arrival at the point of synchronization, that is, to give the musicians time to touch the “hit”, a few seconds before they draw vertical lines on the frames before the punch, so that they are seen as a Vertical line running from left to right until reaching the white point; These lines are the streamers. Another method is with a stopwatch in front of the conductor, where you only have to know when the music comes in and out. In some cases, especially with short duration cue, no synchronization reference is required.

The last task in the central stage, but not for less important, is orchestration. In the orchestration the composer (or orchestrator) must arrange the music into the different instruments of the orchestra or other instruments, depending of which are available or which instruments fit better to get the desired sound for each cue. Many composers orchestrate their own music, as for example Ennio Morricone, but also many others have orchestrators working for them, sometimes just because a matter of time. This is the case of composers as John Williams and Hans Zimmer. It is a task equally creative and technical, but the knowledge about the instruments and their possibilities is highly required. Both composer and orchestrator have to work very close, because the orchestration also must sometimes require of composition procedures, such as adding or modifying harmonies, adding counter-lines or secondary melodies, or modify some keys, in order to make the cue easier playable for some instruments.

Further concepts of the workflow of the film music composer such as Temp Tracks and Mock-ups are nowadays a standard, but since they didn’t exist in the early film, the Golden Age of Hollywood, we will discuss about these practices later, in the chapter about film scoring in the digital era.

After the composition and orchestration process, the next step is usually to record the piece with musicians –except in the case of produced mock-ups, which we will discuss later in this thesis–. The first task for this purpose is to prepare the music.

The music preparation covers following aspects: copying the manuscripts of the score, prepare separate parts for each instrument, organize the scores for the recording session, and, of course, check if there are errors and correct them.

After the scores are ready, it is the moment for the recording session. To ensure success in recording and above all the good use of time in the studio, each member of the team has very specific tasks to perform before, during and after recording. Before recording the music editor must prepare the audio of each click track, as well as the punches and streamers that guarantee the synchronization. A copy clerk, make sure that all musicians have their music scores on their music stand. If electronic sounds were used in the composition, such as rhythmic loops or effects, the composer must assemble them beforehand within the session as the acoustic instruments should record on them. Finally, the composer decides the order of recording either by assemblies or by level of difficulty, there is no specific order, but it must be planned.

During the recording, both the music editor and the composer (unless the latter is the orchestra director himself) are in the control room, following “note to note” of the score, checking that everything is going well. If any of the cue is very long (more than 4 minutes), the composer can search for a “cut point” to record it in two parts and then join them in postproduction. In the recording also they are the director of the film and the producer; It may happen that one of them asks the composer to rewrite a fragment to make a change to his score in full recording. It is there that the composer must be professionally prepared to make any changes and with the greatest agility, as the time goes on and the hours of study are worth. If the settings become too large, it is better for a copyist to be present there, with his software to reprint the parts and avoid confusion among the musicians.

Mixing is the step to follow after recording. Some sound engineers, given the time pressure, are mixing at the same time with the recording, and thus the two processes (recording and mixing) end almost at the same time. When this is already ready, it is taken to the assembly room where the Dubbing session is performed, which consists of mixing music, sound effects and dialogues, the latter being the highest priority over the other two. This session involves the music editor, who is assigning the pieces of music for each scene and adjusting them technically and / or dramatically. It is always good that the composer participates in the Dubbing, because there the control of the music has the director of the film and it can be the case that transform some cue, either because it cuts or even discards it in a scene.

After all those stages of film scoring, a recording of every cue should be ready to synchronize with the film and to mix it together with the dialogues and other sound effects.

[1] A cue is a “piece of music written for a film or television project. Cues can be of any length and are written for a particular scene or scenes in a film. Cues can be score cues (background or theme music) or source cues (music that is heard by the actors in the scene, such as music in a nightclub or music coming out of a radio). Source cues are often music that already exists (such as songs from an album) that are licensed for use in a film. The music supervisor typically handles the licensing of source cues.” (Global Media Online, 2010)

[2] Refers to “Locked Picture – a production’s final edit, after which no timing changes in terms of frames of video will occur. Since the advent of nonlinear hard disk editing of film and television show productions, this term is used less frequently as this editing technology allows editors to make edits and changes to the picture much more easily.” (Global Media Online, 2010)

[3] Extracted from Davis (1999: 100)

[4] Available at: https://simpsonsmusic500.wordpress.com/2011/08/03/music-editing-101-music-spotting-notes/

[5] Available at http://www.angelamorley.com/site/wd-cue1.htm (Last accessed: 4 June 2017)

[6] Click (Click Track) – Click is an audible metronome signal that the conductor and musicians hear through their headphones during recording. Click helps the conductor and musicians perform music at exactly the right tempo so that it will synchronize with the picture as the composer intended. Composers will either indicate a constant or varying click speed for each piece of music that is written. If the microphones inadvertently pick up this sound coming from the headphones during recording, the problem is called click bleed. Clicks that are played for musicians before the cue starts in order to establish the tempo of the cue are called free clicks. (Global Media Online, 2010)

[7] Earlier it was necessary to make space in the tape so that when the projector was passed over it, a white dot would be seen on the screen.

Cite This Work

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing stye below:

Related Services

View allRelated Content

All TagsContent relating to: "Music"

Music is an art form of arranging sounds, whether vocal or instrumental, in time as a form of expression. Some form of music can be seen in all known societies throughout history, making it culturally universal.

Related Articles

DMCA / Removal Request

If you are the original writer of this dissertation and no longer wish to have your work published on the UKDiss.com website then please: