Factors Associated with the Non-progressive Moves of Offenders Within the Offender Personality Disorder (OPD) Pathway

Info: 10451 words (42 pages) Dissertation

Published: 28th Feb 2022

Tagged: CriminologyPsychology

1. Introduction

1.1 Personality Disorder

The concept of personality disorder (PD) in forensic settings has been the subject of much debate, and attempts have been made to diagnose, treat and manage offenders in forensic settings with PD. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 5th Edition (DSM-V; American Psychiatric Association, 2013) defines PD as a mental disorder characterised by “an enduring pattern of inner experience and behaviour that deviates markedly from the expectations of the individual’s culture, is pervasive and inflexible, has an onset in adolescence or early adulthood, is stable over time and leads to distress or impairment” (p. 685). The manual groups PD into three clusters: Cluster A (paranoid, schizoid and schizotypal); Cluster B (narcissistic, histrionic and boderline); and Cluster C (antisocial, dependent, obsessive-compulsive and avoidant). While the manual has been significant in shaping the classifications of different types of personality disorder, the classification of antisocial personality disorder (ASPD) for example, has been highly criticised. The focus on diagnosing ASPD based on behavioural elements of the disorder (i.e. criminal behaviour), rather on the underlying personality structure means by nature, majority of the offender population will meet the criteria for ASPD.

PD is considered to arise from the complex interplay of biological (genetic) vulnerabilities, early childhood experiences and social factors (Tyrer, Reed & Crawford, 2015). The prevalence of PD among the general population ranges from 5% to 10%. The highest prevalence of PD is found among the general prison population: 64% of male sentenced prisoners and 78% of male remand prisoners meet the criteria for PD. The most common PD is antisocial personality disorder (ASPD), affecting 47% of the prison population. Borderline personality disorder (BPD) affects 25% of the prison population (Coid et al., 2009). ASPD is identified by traits that include irresponsible and reckless behaviour, impulsivity, lack of remorse and stability and disregard for society’s norms; whereas, symptoms of BPD occurs within interpersonal contexts, indicating BPD is marked by traits that include overly dependent attachment styles, interpersonal distress, affective instability and attention seeking behaviour (Cloninger, 2005; Kendall et al., 2009). BPD is particularly prevalent and severe in domestic violence, arsonist and sexual offenders including adult rapists. Violent offenders including murders have high rates of antisocial PD traits (Lowenstein, Purvis, & Rose, 2016; Beech, Craig and Browne, 2009; Black et al., 2009).

There is growing evidence to suggest that PD contributes to the commission of violent and sexual crimes. In general, studies using offender samples have shown PD to be a great predictor of recidivism (Coid et al., 2007). In a large cohort of over 350,000 people, researchers found that the risk of violence to be four times greater for individuals with mental health issues including PD (Brennan, Mednick, and Hodgins, 2000). Another study found that in a sample of offenders with ASPD released from high secure settings, 41% reoffended within two years (Coid 2010). The like-hood of recidivism, however, is likely to be confounded by factors such as substance misuse, depression and unemployment.

1.2 Treatment and interventions for personality disordered offenders

A number of interventions have been employed to manage offenders diagnosed with PD. Among the interventions employed in prison settings, psychological interventions have demonstrated to be the most effective at meeting the complex needs of this offender population (Bateman, Gunderson and Mulder, 2015). An example being cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), which involves role-playing, reconstructing risky situations and goal setting, in order to enhance individuals’ understanding of their dysfunctional thinking styles. An early review by Vennard (1997) found that CBT produced positive results with offenders diagnosed with PD in terms of reducing violent reoffending. Offenders with PD also appear to respond positively to dialectical behavioural therapy (DBT). DBT is a variation of CBT, and focuses on the teaching and application of skills related to emotional regulation and interpersonal competency, through group and one-one therapeutic sessions. The work is collaborative: offenders, therapists and other group members mutually agree on treatment goals and ways of achieving such. Both forms of therapies have been adopted in offending behaviour programme including the Focus on Resettlement programme, the Thinking Skills programme and the Controlling Anger and Learning to Manage programme. In general, CBT and DBT techniques have shown to improve problematic behaviours short-term. In term of long-term effectiveness, it is unclear whether the benefits of DBT for this offender population are sustained and specialised adaptations of these therapies for PD offenders is recommended. (Nee & Farman, 2007; Craissati, Horne, & Taylor, 2002)

There is also supportive evidence for Therapeutic communities (TCs). Under the TC system, staff and offenders share significant responsibility and involvement in the running of the community. Treatment in TCS takes the form of psychotherapy, usually delivered in-group settings. TCs also provide traditional individual psychological based interventions. Although TCs are traditionally offered to offenders with substance use disorders or learning difficulties, it has recently been tailored to meet the needs of offenders with risk of reconviction meeting a possible PD diagnosis (Kennard, 2004; dolan & dolan, 2017). As an intervention for PD offenders, TCs have produced promising results in terms of reductions in violence; changes to the psychological well-being; behavioural changes during and after treatment; and lower rates of recidivism (Dolan, 1998; Davies & Campling, 2003; Dolan & Dolan, 2017)

Specialised custodial interventions for offenders with PD include ‘the Dangerous Severe Personality Disorder programme’. Between 2000 and 2013, offenders meeting the potential for dangerousness, serious harm to self and others and pathologies of personality linked to criminal behaviour, were primarily managed under DSPD units. These units were initially developed across five high secure units (Broadmoor Hospital, Rampton Hospital, HMP Whitemoor, HMP Frankland and HMP Low Newton). The aims of the DSPD units were to ensure that effective psychological-based interventions were put into place to reduce the risk of offenders with PD, thus improving public protection and the management of these offenders (Maden, 2007; Buchanan & Leese, 2001).

Research into the DSPD units has been controversial. Early evaluations of the programme found that the units were effective at reducing violence among high risk offenders. Other successes included investment and the development of interventions into a neglected population (Burns et al., 2011; Duggan, 2011). However, a number of failures were highlighted, including the lack of evidence for its effectiveness and the substantial funding into the units (Barrett et al., 2009). There also ethical concerns regarding longer periods of incarceration of offenders based on informal diagnosis and subjective ‘potential’ harm. (Tyrer et al., 2010; Barrett, Byford, Seivewright, Cooper & Tyrer, 2005). This resulted in the decommission of the DSPD units in 2010.

1.3 Offender Personality Disorder Pathway

Subsequent to the closure of the DSPD units, the Offender Personality Disorder (OPD) Pathway was developed through the partnership between the National Health Service (NHS) in England and Wales and the National Offender Management Services (NOMS). The OPD Pathway was commissioned in response to the ineffective management of PD offenders, which results in huge and unnecessary social, economic and political costs. These costs are largely a result of the crimes they commit and their antisocial behaviours, as well as, increased rates of suicide, self-harm incidents and substance abuse among this offender poputlation. Offenders with PD are particularly challenging to work with, contributing to staff burn-out (Freestone et al., 2015). In addition, of those serving life and expired indeterminate sentences, majority meet the criteria for PD (McRae, 2016; . This is because offenders with PD are less likely to fit comfortably into criminal justice services; thus easily identified as “high risk” and “complex” and fit the criteria for indeterminate sentencing (Buchanan & Leese, 2001).

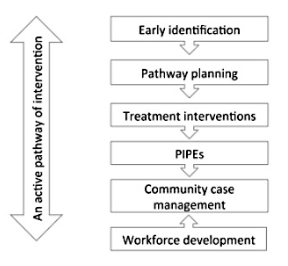

The coalition’s strategy therefore aims to: improve, prioritise and meet the needs of offenders with PD who present a significant level of risk; improve risk assessment and case management in the community to reduce the like-hood of recidivism; to implement effective and interventions in prison settings; to enhance work-force development and to provide professionals with the training and resources required for offenders’ progression (Joseph & Benefield, 2010). It aims to do this by diverting interventions from psychiatric hospitals into prison wings, targeting targer population of offenders with personality complexities. This in turns aims to enhance offender psychological well-being and pro-social behaviour. Lastly, it aims to provide offenders with a pathway of intervention and transition from custodial settings to the community (Minoudis, Shaw & Craissati, 2012). Figure 1 illustrates the key principles compromising the OPD Pathway of intervention.

Figure 1. The OPD Pathway of intervention (Criassti, 2012jr)

1.4 London Pathways Unit

The London Pathways Unit (LPU) is the service setting focused in the present study. The LPU sits within the OPD Pathway services and is delivered by multi-disciplinary team (MDT) of psychologists and prison staff. The LPU is a service for male offenders from London with a history of violence, personality complexities, and with a great like-hood of reoffending upon release. Male Offenders are offered individualised and group interventions informed by formulation based approaches and their case management plan. Other roles of the service are to enable service users’ progression into the community through consultation and partnership with probation services. (Minoudis, Shaw & Craissati, 2012).

Since its opening in April 2013, a number of offenders have completed the pathway and have had either ‘progressive moves’ (i.e. change of security level, relocation to a TC or open conditions, release) or “non-progressive moves” following discharge from the service. “Non-progressive moves”, here are identified as recall due to breach of license, reoffending or de-selection (the removal) from LPU.

1.5 Non-progressive moves

The current understanding of non-progressive moves of offenders is minimal. In general research suggests that non-progressive moves are predicted by PD diagnosis. Studies have generally demonstrated poorer outcomes for offenders diagnosed with PD in comparison to other types of offenders (Coid et al., 2007). In one particular cohort study, offenders with PD had a higher recidivism rate (69%) compared to other offenders (Walter, Wiesbeck, Dittmann & Graf, 2011). Similarly, a study by Phillips et al. (2005) found that individuals with PD re-offended significantly more. In both studies, there were suggestions that the reconviction rate among this group of offenders were associated with poor coordination, and the lack of services and treatment upon release into the community.

More specifically, Andrews and Bonta (2010) identified different diagnoses of PD to be predictive of recidivism in offenders. For example, offenders with borderline traits/diagnoses generally experience higher amounts of interpersonal distress and lower quality in life; subsequently they are more likely to commit re-offences including arson, whereas offenders with ASPD are more likely to violently re-offend (Lowenstein, Purvis & Rose, 2016).The same can be said for younger offenders: they demonstrate greater difficulties adhering to license conditions and cooperating with probation services, and these challenges are magnified for those whom possess antisocial personality traits (Coid et al., 2007).

At the same time a substantial proportion of offenders with PD are resistant to treatment (McRae, 2013). For example, they may refuse to engage in treatment and interventions, which is highly likely amongst this offender population (Howells, Krishnan & Daffern, 2007). Generally, offenders with ASPD are harder to engage in treatment; this often results in their removal from treatment (McRae, 2013). Like with most psychological interventions, its effectiveness varies in terms of motivation and commitment, and offenders’ responsiveness to the treatment, which unlikely this to be present in this offender group. The failure to engage and respond to treatment has the ability to interfere one’s progression (McMurran, 2012)

Non-progressive moves can also be seen in the context of “denial status”. Research suggests that offender denial and minimisation are associated with poor treatment outcomes, responsiveness to treatment, unwillingness to engage and poor compliance to services in custodial and community settings (Harkins, Howard, Barnett, Wakeling & Miles, 2015). All of these factors are negative indices of progress and those who often exhibit denial have higher rates of recidivism. Generally speaking, services typically require offenders to be able to reflect on their offending behaviour to participate in treatment. Lack of offender denial is concerning for group instability and treatment responsiveness in services is concerning for service funding, staff morale and group instability (Nunes et al, 2007; Levenson & Macgowan, 2004). Offenders must also demonstrate a suitable level of truthfulness, and where both denial and deception is apparent, they are likely to be removed from treatment/interventions(Spidel, 2002; ). However, it is important to acknowledge that this kind of behaviour is often adopted as a coping mechanism to either cope with the surrounding circumstances or overwhelming past experiences and and by doing it so it facilitates interpersonal detachment and prevents feelings of shame and guilt (Whyte, Fox &Coxell, 2006)

The relationship between offender-staff relationships and non-progressive moves is also of importance. Indeed, the suggestion that positive staff-offender relationships decreases offenders’ likehood of reoffending fits with conclusions of various meta-analyses (refrence). This is because positive interactions play a prominent role in shaping one’s adherence to moral codes and acceptable behaviour (Burnett & McNeill, 2005). On the other hand, the presence of criminal associates and gang affiliations is one of the strongest predictors of recidivism. Criminal associates promote antisocial attitudes and lifestyle, providing support for continued anti-social behaviour (Andrews and Bonta, 2010; Tatar, Cavanag & Cauffman, 2016). Additionally, social exclusion is frequently found with this offender population, and research has shown social exclusion to be linked to offending and reoffending. A protective factor for those most vulnerable and likely to experience great levels of social exclusion is to build a support network with services. For offenders with PD, building positive relationships is significant for rehabilitation and social reintegration (Unit, 2002)

Furthermore, it is likely that offenders diagnosed with PD use illegal substances, which increases the like-hood of producing non-progressive moves due to its association with reoffending/breach of license conditions. In prison settings problematic behavioural and mental health issues is often associated with substance use problems. These problems are likely to be followed by offenders’ post release. High-risk offenders are thought to be at a greater risk of drug overdosing than other types of offenders. Research also indicates that offenders who inject drugs in prison, are likely to inject in the community three months after release (Stöver et al., 2008). At the same time the transition from incarceration to life outside in the community is a challenging period for vulnerable offenders, and the longer an offender has been incarcerated, the greater difficulty they demonstrate in adapting and conforming to life outside prison.

1.6 Rationale for the current study

Non-progressive moves are a significant problem for the criminal justice system, costing the Government ….yearly. The literature has attempted to explore this subject; however, there is still an absence of research investigating factors associated with non-progressive moves of offenders, in particular for offenders within the OPD Pathway. It therefore seemed appropriate that the present study focused on this gap in the literature and in doing so it will inform treatment planning and practise for the LPU. As such, it will allow evidence-based revisions to be made to the OPD Pathway to better meet the needs of this population. The results produced may also act as a starting point for future research in this area.

1.7 Aims of the current study

The overall aim of the research was to apply a qualitative research method to investigate factors associated with non-progressive moves for offenders within the OPD pathway from the perspective of professionals whom worked with the offenders.

Methodology

2.1 Research design

The present research was conducted with a qualitative focus. The choice of research methodology was informed by the objective of gaining an in-depth understanding of factors associated with non-progressive moves. This was initially explored through focus groups and then semi-structured interviews.

2.2 Sample and inclusion criteria

A purposive sampling strategy was sought. This is a strategy commonly applied in qualitative research for the identification and selection of in-depth cases related to the topic of interest. There were two main inclusion criteria: (1) professionals working under the OPD Pathway, including probation officers, psychologists and prison officers involved in the management of the offenders who produced non-progressive moves; and (2) at least a year experience of having worked under the OPD Pathway. This was to ensure that the data derived from the participants were relevant to the study and participants had enough of experience of having worked under the OPD Pathway. With qualitative research, the sample size is of less importance and often dependent on the homogeneity of the group being studied/interviewed. A sample size between 6-10 participants is considered adequate to generate themes using qualitative thematic analysis (Guest, Brunce and Johnson, 2006)

(No) professionals were recruited for the study. Majority of the participants were members of the MDT team in the LPU including, forensic psychologists, assistant psychologists, a consultant psychologist, a prison officer, offender managers and probation officers. Of those (no), (no) participated in the two focus groups and (no) participated in the semi-structured interviews. Demographic details are provided in Table 1 and Table 2.

Table 1 Sample demographic information for Focus Group 1&2

| Demographic Variable | Frequency |

| Age | M=32 (SD=8.8, Range= 22-55) |

| Gender | 9 females, 2 males |

| Profession | 5 psychology staff, 5 probation staff, 1 prison officer |

| Length of time of focus group | M= (SD=, Range=) |

Table 2 Sample demographic information for interviews

| Demographic Variable | Frequency |

| Age | M= (SD=, Range=) |

| Gender | females, males |

| Profession | psychology staff, probation staff |

| Length of time of interviews | M= (SD=, Range=) |

2.3. Characteristics of offenders who produced non-progressive moves

No of offenders were identified using the LPU database of all present and discharged service users.

2.4. Recruitment strategy

Participants were recruited via email. A database maintained by the LPU of all discharged service users was used to extract information of offenders who produced the non-progressive moves and the contact details of professionals that had worked with these offenders. Out of (insert final number) identified and contacted, (insert final number) agreed to participate in the focus groups and (insert number) agreed to participate in the the semi-structured interviews.

2.5 Data Collection

2.5.1 Focus group

The research required a preliminary understanding about the issues of non-progressive moves. Focus group discussions were seen as an appropriate forum to elicit such understanding. Two focus groups were held within HMP Brixton and Lambeth hospital to ensure accessibility and convenience for participants. A topic guide was used, following a schedule broadly around the three following questions Does the OPD Pathway work for everyone? (2) Thinking of the men you have worked with, who does the pathway work for? (3) What factors do you think prevented people from benefiting from the Pathway? The questions were used as prompts and developed in advanced to provide relevant data to the study’s aims (see appendix 1). The focus groups were digitally recorded and transcribed by the researcher. The data generated from the focus groups was used to inform the development of an interview schedule (see appendix no).

2.5.2. Semi-structured interviews

Interviews were conducted using a semi-structured approach. An interview schedule was followed to provide guidance to the topics covered in the focus groups. The interview schedule included open questions to encourage participants to speak expressively about the non-progressive moves of offenders (i.e. what do you think could have prevented the offender from producing a non-progressive move; what could have been put in place to ensure offenders benefit more from the pathway; what was is it like working with the offender?).

2.6. Data management

All aspects of the Data Protection Act and the British Psychological Society code of ethics and conduct guidelines were adhered to. Participant anonymity was upheld using a unique numeric identifier. Documents containing information regarding participants were kept in a locked cabinet. The audio-recorder was stored separately in a safe location, where it was protected from damage and destruction. The controlled access to the audio was accomplished by storing the audio-recorder in a locker in a locked office/room, and only accessible through security procedures and to the researcher lead and researcher assistant. The information contained in the audio-recorder was converted into data to be analysed in detail. Files was sent and collected using a login and password specific to the project, using the service’s Upload Page, thus avoiding sending files by email. All typists were vetted and signed a confidentiality agreement. These digital files and transcripts will be kept for a maximum of two years. Data extracted from the LPU Database for each offender was anonymised and transported, stored and destroyed as per standards.

2.7. Ethical approval and considerations

Ethical approval was obtained from the National Offender Management Service Research Committee (NRC 2015- 161) and Goldsmiths, University of London Ethical Committee. Ethical considerations relating to this research was informed consent and debriefing, right to withdraw, anonymity of participants, follow-up support, and controlled access and safe storage of audio-recorder.

2.7.1. Informed consent

Written consent was sought prior to commencing the focus groups and interviews. All participants were informed of the nature of the research and given a participant information pack to review prior to consenting. This included information about the research’s methodology, future publications, and the use of recording devices and participants’ rights to withdrawal. Time was also spent with participants at the beginning and ending of the focus groups and interviews to explain what the research involved, and in particular how the results would be presented and published. Participants were given time to consider this information and ask any relevant questions.

2.7.2. Right to withdraw

Participants were informed of their right to withdraw from the research before and after the focus groups and interviews, and the information collected would not be used if researchers were informed of their withdrawal within 24-hours. However, participants were briefed that once the data was analysed it would be stored against unique numeric identifiers and because of this it would not be possible withdraw their data after the 24-hour period. This information was revealed verbally to ensure all participants understood of this.

2.7.3. Potential vulnerability

The vulnerability of the content of the discussions was identified as a potential ethical issue. Professionals were asked questions regarding men who did not produce progressive moves and share experiences that had the potential to evoke discomfort. Upon completion, participants were offered psychological support, should they require.

2.7.4. Debriefing and feedback

Upon the completion of the focus groups and interviews, participants were given the opportunity to ask any further questions regarding the research and were given the contact details of the research team. In term of feedback (regarding the results of the research) this will be made available through the publication of the research and future conference presentations. A copy of the published report will be sent to participants.

2.8. Data Analysis

Data generated from the interviews were transcribed and analysed using Thematic Analysis (TA). TA is a method of qualitative analysis used to establish, examine and distinguish themes within data. For the present study, TA was deemed the most suitable analysis to address the aims of the research due to its flexibility to link relationships between themes. Other methods, such as Content Analysis were also considered, however would limit data interpretation. Table 3 summaries the 6 phases of Thematic Analysis adapted from Braun and Clarke (2006).

Table 3 The 6 phases of Thematic Analysis

| Phase | Description |

| 1. Data familiarisation | Transcripts were read and re-read, noting initial coding ideas. |

| 2. Generating initial codes | Initial codes were notes in the right column of the transcripts. |

| 3. Searching for themes | Codes were collated into potential themes. Emerging themes were noted in the left hand column of the transcripts. |

| 4. Reviewing themes | Themes were reviewed to ensure they represented a patterned response of relevant statements and meanings. |

| 5. Defining and naming themes | Themes were defined, labelled and discussed with independent reviewers to ensure they adequately represented the coded extracts. |

| 6. Producing the report | The themes generated were discussed in the results and discussion section. A selection of direct quotations were used as compelling evidence. |

An example of the analysis is provided below in table 4.

| Emerging Themes | Transcript | Initial Notes |

Figure 1: Example of Analysis

2.8. Data reliability and validity

Data reliability and validity concerns with the consistency and/or the repeatability of the data and the extent to which the central themes accurately represent the data generated from the interviews. In order to reach this, the same interview schedule and interviewer was used to conduct the semi-structured interviews. Secondly, two independent reviewers reviewed and evaluated the labelled themes against the coding extracts. Here an adequate level of agreement was achieved with respect to the labelled themes. Thirdly, a coding template was followed to ensure data was interpreted in a similar fashion.

3. Results

From the analysis of the interviews, five central themes were generated. These themes were selected on the basis that they held direct significance and relevance to offenders’ non-progressive moves. The five themes were labeled as: substance use; suitability of offender and motivation; nature and complexity of personality disorder; interpersonal difficulties; and problems in risk management. Within each theme, a number of sub-themes were also identified. Table 3 represents the central themes with associated sub-themes. The numbers in bracket displays how many participants cited the particular theme. This will be used for further discussion.

Table 3 Summary of central themes with associated sub-themes relevant to offenders’ non-progressive moves.

| Central themes | Sub-themes |

(insert final number) |

Illegal substance use and deselection

Drug habit and recidivism |

|

ASPD and emotion regulation problems BPD traits and attachment difficulties |

|

Willingness to engage

Readiness to change Responsiveness to treatment |

|

Superficial charm and manipulation

Pathological lying and deception Denial and minimisation |

|

Quality of decision-making Lack of personal support Non-compliance with services |

3.1 Substance use

Substance use was a recurring theme and was cited in all interviews. Two further sub-themes compromised this theme: substance use and deselection; and drug habit and recidivism. Participants frequently cited illegal substance use as the main factor for the deselection of offenders:

“…he was using drugs all the time and in a unit where you are supposed to be drug-free to engage with service, it came with no surprise he was deselected…”

“…he was challenged about his spice use but he continued using spice and I think a lot was to do with the fact that it all felt a little bit too much for him…so when he became overwhelmed he would increase his drug use…and it wasn’t just the prescribed drugs…it was everything he could get his hands on…”

References were also made to offenders ‘using drugs’ and “offending to fund drug habit”, making it the most frequently identified factor associated with offenders’ non-progressive moves in the community:

“…and I was aware he had a history of using drugs and had previously been involved with services but unfortunately the drug use became more problematic when he left prison…and he lied to me about this…so he began using cocaine and made a habit of it…so I think when he decided to go back to the same betting shop and rob it…it was to sustain his cocaine habit.

3.2 Nature and complexity of PD Traits

(insert final number) of participants considered the nature and complexity of PD traits considered relevant to offenders’ non progressive moves. ASPD traits appeared to predict non-progressive moves:

“…he had extreme traits of antisocial personality disorder so he would often have these angry outbursts and would threaten staff…but funny enough it felt like this happened a lot after a group or a keywork session so I do wonder if it was because we were exploring emotions that he wasn’t used to speaking about…”

“…I always find the more antisocial pd offenders harder to gain a progress with because they have so much difficulty talking about their feelings and emotions, and for a lot of these guys you know their lack of emotional regulation plays a big role in their offending behhaviour and their lack of progressive moves…”

Offenders’ borderline personality disorder traits were also relevant to their non-progressive moves:

“…when you think about offenders that are borderline and fail…you often think about the fact that they are overtly attachment to people and services so I think once they don’t have those attachment figures in place they find it difficult to progress and do anything for themselves…”

“…his main issues was his attachment to his partner…she was very pd herself and would often lie about pregnancies and other serious issues and he couldn’t handle things like that very well and because of his overbearing attachment to her he gradually began disengaging with the service…and that overall resulted in a non-progressive move…”

3.3 Suitability of offender and motivation

(Insert final number) of participants cited suitability of offender and motivation a significant factor for progression. This theme was divided into three sub-themes: willingness to engage, readiness for treatment and responsiveness to treatment. In terms of willingness to engage, staff reported similar views in that lack of engagement often resulted in offenders not progressing and being deselected from the unit:

“…in places like the LPU you need to have someone who is willing to participate and engage with staff and the service, because when you don’t there isn’t much hope for the prisoner and you don’t see them progressing at all…”

“when he was first admitted to the unit, he engaged well and you could see some changes to his behaviour, but soon after he stopped engaging he wasn’t able to progress and his needs were not met…”

3.4 Interpersonal difficulties

This theme was observed in the narratives of five participants. Within this theme were three sub-themes: superficial charm and manipulation; pathological lying; and denial and minimisation:

“…he was very charming in the way he conducted himself and when you first meet him, you think of him as the perfect prison role model and he appeared to be very pro-staff and very pro-psychology…but then…there was a very manipulative side to him and he used his superficial charm to trick people into thinking he was doing well and nothing was wrong with him, and that he was very helpful…when actually he was never up to no good and this made the relationship very difficult, because it was constant games with him…and that in the end is still one of the reasons he can’t progress and he is still stuck in the system”

“…the problem here was that I didn’t know what was true so we couldn’t really determine his treatment needs were…”

“…I have known him for many years now and not once has he taken responsibility for any of his behabiousr…and till now he still denies the offence and likes to victim blame a lot and until he is able to take responsibility for his actions…the continue denial of his offence will always be a risk and the parole board acknowledge that and even thought he completed the LPU and moved one…he wasn’t able to progress because of this…”

3.5 Problems in risk management

Problems in risk management was an area where probation staff highlighted having a significant impact in the progression of offenders in the community. Firstly, there as a general view that staff were not always consulted in the decision of releasing some offenders and there was a lack of collaborative decision-making:

“…I don’t know how he was ever released or why they even thought (referring to the parole board) he was at a stage where he could be released…and myself and X mentioned that he was still very risky to be put in the community but they were willing to risk the decision and test it out for themselves and in the end what we predicted happened: he re-offended again…”

The lack of compliance of services resulting in subsequent incarceration was also evident in participants’ narratives:

“….his license conditions required a moderate level of compliance to he wasn’t able to keep up this compliance and he then began engaging in a lot risky behaviours including drinking excessively so I had no option but to recall him…he was given the chance to engage with A&A and other relevant substance misuse help services”

Participants also expressed that for some offenders whom “made significant personal” and “social gains” in the LPU to subsequently being release with no support system, there was a greater difficulty getting them to adhere to their license conditions:

“although he was placed in supported premises, he wasn’t given the same amount of support as he received on the LPU and he found himself not having peers or anyone he could turn to so the lack of support resulted him in going out and committing petty offences”

4. Discussion

The accounts of participants have generated a number of themes relevant to non-progressive moves of offenders. The data suggests that substance abuse; suitability of offender and motivation; nature and complexity of PD traits; interpersonal difficulties; and problems in risk management remains significant issues for the progression of offenders. Here, the themes are discussed reference to the psychological literature.

First of all, illegal substance use was the most consistent theme. This confirms the link between illegal substance use and reoffending, breach of license conditions and removal from services. The link, is however, is complex. Illegal substance use appeared to predominately interact with offenders’ deselection in two ways: as a barrier to engaging with staff and the LPU service and as a coping mechanism for dealing with difficult emotions. In the community illegal substance use was linked to the pressure to re-offend to fund one’s drug habit. These findings are in alignment with the psychological literature in that the illegal substance use is particularly prevalent in offenders with PD. Interestingly, the literature also suggests that severity of PD traits appeared to be exhibited as a result of using substances.

Secondly, the results suggest that non-progressive moves are associated with the characteristics of offenders with diagnoses of ASPD and BPD. These included emotional regulation problems for offenders with ASPD, and interpersonal difficulties (overly attachment and dependence on staff and other individuals, and extreme reactivity to interpersonal) for offenders with BPD. Indeed, the described interpersonal difficulties and emotional regulation problems in BPD and ASPD offenders respectively, is associated with non-progressive moves; offenders with ASPD are more likely to re-offend, indicating deficits in emotion regulation which increases this behaviour; while offenders with BPD produce non-progressive moves within interpersonal contexts.

Furthermore, results support the idea that offender motivation and suitability remains a key factor in offender progression. Offender motivation and suitability is influenced by factors such as willingness to engage, readiness to change, and responsiveness to treatment. The results confirmed that for offenders who were unwilling to engage and change and unresponsive were likely to remain untreated and to re-offend. Offenders’ motivation and readiness to change also appeared to have had an impact upon the quality of therapeutic relationship with professionals. However, all factors’ role in non-progressive moves remains complex and is evidently affected by other factors such as one’s PD, at the same time; professionals spoke of having more positive therapeutic relationships and could identify more progression of offenders whom engaged in treatment and the groups.

For those produced non-progressive moves, the presence of interpersonal difficulties was also evident. There association between interpersonal difficulties propensity re-offend is widely recognised. Notably, there was a strong association between denial and minimasation, and factors such as willingness to engage, responsiveness to treatment and offender motivation, and progress. This is not surprising given the support for the exclusion of deniers from treatment to maintain group stability. However, it is worth highlighting that offenders’ level of denial may also reflecr the offenders’ risk level and acceptability for their offending behaviour. In this case it is harder to engage the offender in treatment but to also produce and progressive move. In terms of those offenders whom continued to re-offend and because the offended continued to deny previous offences and to take personal responsibilities for one’s offending behaviour. Still, the relationship between denial and non-progressive moves, particularly re-offending is not fully understood. There was also a focus on offenders’ superficial charm and manipulation and Pathological lying and that this again affected the relationship and the work carried out with offenders. Findings revealed that these kind of offenders are likely to engage in ‘impression management’. The difficulty with this is that offenders may be reluctant to revealing their truth difficulties and managing skills, and it may be difficult to assess their needs and risks and possibly when they are release they exhibit behavior that may be keeping inside. Notably there is an absence in research exploring deception as a factor for reoffending, removal from services or recall due to breach of license.

Problems in risk management offers further explanation to the production of non-progressive moves of offenders. For example, with some of the extracts provided above (see results section) participants made reference to the lack of collaborative decision-making in the cases of those who produced non-progressive move in the cases of those who produced non-progressive moves. The importance of collaborative decision-making is long established in policy and significant for offenders within the OPD Pathway whom require complex risk management needs. Offender progression also appeared to have been hindered by offenders’ non-compliance to services in research has predominately shown that those who demonstrate non-compliance re-offend more. Similarly, the lack of support was cited as potential inhibiting factor for progression. The findings suggest that limited attention was paid to offenders’ reintegrating ito the community, in particular, offenders. That is not to say that risk management plans did not take factors like this into account. However it appeared to be neglected in the cases of those whom produced non-progressive moves. The literature on offender desistance emphasizes on the significance of having having a support network as a central part to rehabilitation and social reintegration (Unit, 2002). Indeed, a positive support network has the potential to reduce the like-hood of reoffending,

Limitations of the research

Although the present study shows promising findings, some methodological limitations are worth consideration. The main limitation of this study is relevant to the use of qualitative methodology. Limitations regarding qualitative methodology include lack of objectivity, replication and generalizability. Indeed, these limitations are frequent in this type of methodology (reference )—however, the focus of this research was to explore a currently neglected and underrepresented area of research and in contrast to quantitative methodology, qualitative offers in-depth knowledge of the topic of interest. Participation was also voluntary, creating the potential for a biased sample. Indeed the study sampled a small number of research participants, limiting the study’s relevance to other services part of the OPD Pathway. The predominate use of psychologists, offender managers and probation officers also indicates an overrepresentation of this profession in comparison to prison officers for example, whom were underrepresented and only a prison officer participated in the focus groups., the interviews adopted a semi-structured approach, and biases associated with semi-structured interviews are acknowledged. It is possible that the direction of the interviews was limited or overly-guided, however, an interview schedule was followed to ensure that participants were able to expressively speak about non-progressive moves whilst ensuring professionals expressed information relevant to the topic of interest. Finally, the focus groups and semi-structure interviews were conducted, recorded, transcribed and analysed by a researcher who had previously worked on another OPD Pathway custodial service. It could be argued that the researcher had

At the same time, it could be argued that the researcher’s interpretations of the data may be biased based prior knowledge and interest in the topic of interest. However, efforts were made to ensure that the data and themes generated were reviewed by two independent reviews and research bias was reduced to a moderate level.

Recommendations for practice and continuing research

In line with the Nice guidelines on management of offender diagnosed with PD, attention is placed for interventions on the LPU to be flexible, and to consider engagement, responsiveness, emotional regulation problems and interpersonal processes. Where personality dysfunction is severe, it will be particularly important to implement interventions with a greater risk of reoffending and treatment needs. In light of this, Therapeutic work for ASPD offenders may be directed towards challenging their emotion regulation problems and needs, which appears to related to their non-progression; whereas interpersonal difficulties play a big role in the non-progression of BPD offenders which treatment needs. With both groups it is recommended professionals adopted intense measures to engage these as much as possible.

The findings of this study support the importance of substance abuse treatment in custodial settings and during the time offenders’ renter society after incarceration and its potential to reduce non-progressive moves. This supports the current guidelines (Ministry of Justice, 2011; Bourne 2010) with working with Personality Disordered Offender which places a great emphasis on increased transitional planning and support from those whom are released and at greater risk of abusing substances. Here, the study’s findings support the recommendation for increased and relapse prevention planning before and after release, in particular for offenders whom are identified at a greater risk of using substances. Substance use problems may also be a key focus of interventions on the LPU.

The results results draws attention to the significance of support and intervention post release, in particular for offenders whom have been incarcerated for a long time and have not been able to build a stable and positive support network in the community. It may be useful to consider how support is delivered post release for those most vulnerable. In this instance, offenders may benefit from post-release work directed towards building positive relationships and on promoting pro-social ways of achieving this,

The research further highlights need for substance misuse interventions to be implemented in the OPD Pathway services.

Risk management is an integral part of preventing offenders of re-offending and breaching their licenses and the following f recommendations are regarded in that context: professionals focus on the quality of decision-making regarding offenders risk in the community, in particular acknowledge that all sources of information and professionals have been consulted and included in the decision. This is to ensure it targets decisions made for offenders most vulnerable and risky. In line with existing NICE guidance (NICE, 2013) professionals should develop comprehensive risk management plans for offenders considered to be of high risk and vulnerability. This plan should focus incorporating different multi-agency services to ensure areas of risk such as: lack of social support; non-compliance with services continuity of case management is considered.

Finally, the current study recommends further exploration of this topic. To make any further conclusions about the study’s findings, it would be useful to compare the experiences of staff whom worked with offenders who produced progressive moves, in comparison to staff whom worked with offenders that produced the non-progressive moves. While this study provides some indication of factors associated with non-progressive moves of both ASPD and and BPD offenders on the OPD Pathway, it would be interesting to identify any similarities and differences in the progression of these two groups of offenders. In addition. Future studies may also wish to consider using using a larger sample of professionals and a greater inclusion of prison officers. Finally, it worth acknowledging that future studies may benefit from exploring different non-progressive moves, including using three different types of non-progressive moves, as we didn’t differentiate between all three or neither did we differeiate between different types of disorder and its specific influence on non-progressive rather this was a theme generated by participants narratives.

Conclusion

In summary, the present study has shown that various factors are associated with the non-progressive moves of offenders within the OPD Pathway. Results indicated that while some factors are directly relevant to offenders’ non-progressive moves, that one factor alone does not influence the production of non-progressive moves; rather a combination of different factors. Some factors also appeared to have been more predominate in the production of the non-progressive move in comparison to other factors and therefore, were frequently cited in participants’ narratives. Prior to this, there was a little understanding of non-progressive moves, in particular, an absence in the literature exploring the non-progressive move of offenders with the OPD Pathway. Futhermore, the findings from this study are not too dissimilar to those in the literature, and research has predominately shown that illegal substance use; nature and complexity of PD traits; suitability of offender and motivation; interpersonal difficulties; and problems in risk management all have the ability to contrite to non-progressive moves. However, the current findings offer some extension of previous studies. For example, for ASPD offenders, their non-progressive moves appear to be relevant to their emotional regulation difficulties s opposed to BPD with interpersonal difficulties. Lastly, the present study may be used as a basis for further research as suggested above. Finally, despite the study only focusing on one OPD pathway custodial service, it has contributed to this neglected area of research, and by doing it so, it has potential to inform treatment planning and practice for the London Pathways Unit. Lastly, the present findings are preliminary, but nevertheless provide promising results that all the identified themes are all relevant factors associated with non-progressive moves.

References

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing

Andrews, D. A., & Bonta, J. (2010). The psychology of criminal conduct. Routledge.

Barrett, B., Byford, S., Seivewright, H., Cooper, S., & Tyrer, P. (2005). Service costs for severe personality disorder at a special hospital. Criminal Behaviour and Mental Health, 15(3), 184-190.

Barrett, B., Byford, S., Seivewright, H., Cooper, S., Duggan, C., & Tyrer, P. (2009). The assessment of dangerous and severe personality disorder: service use, cost, and consequences. The Journal of Forensic Psychiatry & Psychology, 20(1), 120-131.

Bateman, A. W., Gunderson, J., & Mulder, R. (2015). Treatment of personality disorder. The Lancet, 385(9969), 735-743.

Beech, A. R., Craig, L. A., & Browne, K. D. (Eds.). (2009). Assessment and treatment of sex offenders: A handbook. John Wiley & Sons.

Black, D. W., Gunter, T., Allen, J., Blum, N., Arndt, S., Wenman, G., & Sieleni, B. (2007). Borderline personality disorder in male and female offenders newly committed to prison. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 48(5), 400-405.

Bourne, R. (2010). Antisocial Personality Disorder: The NICE Guideline on Treatment, Management and Prevention.

Brennan, P. A., Mednick, S. A., & Hodgins, S. (2000). Major mental disorders and criminal violence in a Danish birth cohort. Archives of General psychiatry, 57(5), 494-500.

Buchanan, A., & Leese, M. (2001). Detention of people with dangerous severe personality disorders: a systematic review. The Lancet, 358(9297), 1955-1959.

Burnett, R., & McNeill, F. (2005). The place of the officer-offender relationship in assisting offenders to desist from crime. Probation Journal, 52(3), 221-242.

Burns, T., Yiend, J., Fahy, T., Fitzpatrick, R., Rogers, R., Fazel, S., & Sinclair, J. (2011). Treatments for dangerous severe personality disorder (DSPD). Journal of Forensic Psychiatry & Psychology, 22(3), 411-426.

Cloninger, C. R. (2005). Antisocial personality disorder: A review. Personality Disorders. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons, 125-200.

Coid, J., Moran, P., Bebbington, P., Brugha, T., Jenkins, R., Farrell, M., … & Ullrich, S. (2009). The co‐morbidity of personality disorder and clinical syndromes in prisoners. Criminal Behaviour and Mental Health, 19(5), 321-333.

Coid, J., Yang, M., Ullrich, S., Zhang, T., Roberts, A., Roberts, C., … & Farrington, D. (2007). Predicting and understanding risk of re-offending: the Prisoner Cohort Study. Research summary, 6, 1-9.

Craissati, J., Horne, L., & Taylor, R. (2002). Effective treatment models for personality disordered offenders.

Davies, S., & Campling, P. (2003). Therapeutic community treatment of personality disorder: service use and mortality over 3 years’ follow-up. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 182(44), s24-s27.

Dolan, B. (1998). Therapeutic community treatment for severe personality disorders. Psychopathy: Antisocial, criminal, and violent behavior, 407-430.

Dolan, R., & Dolan, R. (2017). HMP Grendon therapeutic community: the residents’ perspective of the process of change. Therapeutic Communities: The International Journal of Therapeutic Communities, 38(1), 23-31.

Duggan, C. (2011). Dangerous and severe personality disorder. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 198(6), 431-433.

Fazel, S., & Danesh, J. (2002). Serious mental disorder in 23 000 prisoners: a systematic review of 62 surveys. The lancet, 359(9306), 545-550.

Freestone, M. C., Wilson, K., Jones, R., Mikton, C., Milsom, S., Sonigra, K., … & Campbell, C. (2015). The impact on staff of working with personality disordered offenders: A systematic review. PloS one, 10(8), e0136378.

Harkins, L., Howard, P., Barnett, G., Wakeling, H., & Miles, C. (2015). Relationships between denial, risk, and recidivism in sexual offenders. Archives of sexual behavior, 44(1), 157-166.

Howells, K., Krishnan, G., & Daffern, M. (2007). Challenges in the treatment of dangerous and severe personality disorder. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment, 13(5), 325-332.

Joseph, N., & Benefield, N. (2010). The development of an offender personality disorder strategy. Mental Health Review Journal, 15(4), 10-15.

Kendall, T., Pilling, S., Tyrer, P., Duggan, C., Burbeck, R., Meader, N., & Taylor, C. (2009). Guidelines: borderline and antisocial personality disorders: summary of NICE guidance. BMJ: British Medical Journal, 338(7689), 293-295.

Kennard, D. (2004). The therapeutic community as an adaptable treatment modality across different settings. Psychiatric Quarterly, 75(3), 295-307.

Levenson, J. S., & Macgowan, M. J. (2004). Engagement, denial, and treatment progress among sex offenders in group therapy. Sexual Abuse: A Journal of Research and Treatment, 16(1), 49-63.

Lowenstein, J., Purvis, C., & Rose, K. (2016). A systematic review on the relationship between antisocial, borderline and narcissistic personality disorder diagnostic traits and risk of violence to others in a clinical and forensic sample. Borderline personality disorder and emotion dysregulation, 3(1), 14.

Maden, A. (2007). Dangerous and severe personality disorder: antecedents and origins.

McMurran, M. (2012). Readiness to engage in treatments for personality disorder. International Journal of Forensic Mental Health, 11(4), 289-298.

McRae, L. (2016). Severe personality disorder, treatment engagement and the Legal Aid, Sentencing and Punishment of Offenders Act 2012: what you need to know. The journal of forensic psychiatry & psychology, 27(4), 476-488.

McRae, L. (2013). Rehabilitating antisocial personalities: treatment through self-governance strategies. The journal of forensic psychiatry & psychology, 24(1), 48-70.

National Health Service England & National Offender Management Service (2015) Working with Personality Disordered Offenders. A Practitioner’s Guide. (Craissati J, Joseph N & Skett S). Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/468891/NOMS-Working_with_offenders_with_personality_disorder.pdf (accessed July 2017).

Nee, C., & Farman, S. (2007). Dialectical behaviour therapy as a treatment for borderline personality disorder in prisons: Three illustrative case studies. The Journal of Forensic Psychiatry & Psychology, 18(2), 160-180.

Nunes, K. L., Hanson, R. K., Firestone, P., Moulden, H. M., Greenberg, D. M., & Bradford, J. M. (2007). Denial predicts recidivism for some sexual offenders. Sexual Abuse: a journal of research and treatment, 19(2), 91-105.

Sansone, R. A., & Sansone, L. A. (2009). Borderline personality and criminality. Psychiatry (Edgmont), 6(10), 16.

Spidel, A. (2002). The association between deceptive motivations and personality disorders in male offenders (Doctoral dissertation, University of British Columbia).

Tatar II, J. R., Cavanagh, C., & Cauffman, E. (2016). The importance of (anti) social influence in serious juvenile offenders with psychopathic traits. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law, 22(1), 92.

Tyrer, P., Duggan, C., Cooper, S., Crawford, M., Seivewright, H., Rutter, D., … & Barrett, B. (2010). The successes and failures of the DSPD experiment: the assessment and management of severe personality disorder. Medicine, Science and the Law, 50(2), 95-99.

Tyrer, P., Reed, G. M., & Crawford, M. J. (2015). Classification, assessment, prevalence, and effect of personality disorder. The Lancet, 385(9969), 717-726.

Unit, S. E. (2002). Reducing re-offending by ex-prisoners.

Walter, M., Wiesbeck, G. A., Dittmann, V., & Graf, M. (2011). Criminal recidivism in offenders with personality disorders and substance use disorders over 8years of time at risk. Psychiatry research, 186(2), 443-445

Whyte, S., Fox, S., & Coxell, A. (2006). Reporting of personality disorder symptoms in a forensic inpatient sample: Effects of mode of assessment and response style. The Journal of Forensic Psychiatry & Psychology, 17(3), 431-441

Cite This Work

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing stye below:

Related Services

View allRelated Content

All TagsContent relating to: "Psychology"

Psychology is the study of human behaviour and the mind, taking into account external factors, experiences, social influences and other factors. Psychologists set out to understand the mind of humans, exploring how different factors can contribute to behaviour, thoughts, and feelings.

Related Articles

DMCA / Removal Request

If you are the original writer of this dissertation and no longer wish to have your work published on the UKDiss.com website then please: