Foreign Direct Investment and Possible Benefits for Emerging Countries Demonstrated by the Mexican Automotive Industry

Info: 16980 words (68 pages) Dissertation

Published: 4th Jan 2022

Tagged: AutomotiveInvestment

Abstract

The aim of this paper is to provide the readers with a basic understanding of the financial instrument Foreign Direct Investment (FDI), and the reason why Multinational Enterprises (MNEs) have been using it in the Mexican automotive industry. In this context, past events regarding FDI, the current economic situation as well as future prospects of this industry has been analyzed. Moreover, it explains how MNEs have made the Mexican automotive industry one of the most competitive industries of its kind and, currently, the most successful in whole Latin America. It has to be considered that the findings are sector specific and therefore, can not be applied to another sector. Based on the research conducted, possible benefits for other emerging economies derived from FDI were examined. As an outcome, this work will show what other emerging economies can learn from Mexico’s example.

The methodological approach is primarily based on the research of secondary sources in combination with local insights provided by an economics lecturer from Mexico City. As the automotive industry has been very vivid during the last two decades, especially in Mexico, relevant quantitative and qualitative data, journals, already existing research papers, online reports, as well as official documents from international institutions and the Mexican government served as valuable inputs.

Key words: FDI, Developing countries, Mexico, automotive, TTIP

Table of Contents

Click to expand Table of Contents

List of Abbreviations

1 Introduction

1.1 Research Objectives

1.2 Research Questions

1.3 Methodology

1.4 Limitations

1.5 Structure of the work

2 Foreign Direct Investment (FDI)

2.1 FDI in developing countries

2.2 Components

2.3 Determinants

2.4 Host country determinants for FDI

2.4.1 Policy framework for FDI

2.4.2 Economic determinants

2.4.3 Business facilitation

2.5 Classification of FDI

2.5.1 Horizontal FDI

2.5.2 Difference between horizontal and vertical FDI

2.5.3 Vertical FDI

2.6 Greenfield Investment

2.7 Brownfield Investment

3 Attractiveness of FDI for car manufacturers in Mexico

3.1 Economic overview of Mexico

3.2 Historical development and adjustments made by the Mexican government

3.3 FTA current situation

3.4 Reasons why to invest in the Mexican automotive industry

3.5 Benefits for Mexico derived from FDI

3.6 Remaining challenges for Mexico

3.6.1 TTIP and CETA as threat for Mexico’s automotive industry

4 Development of the Mexican automotive industry with the help of FDI

4.1 Development of the industry

4.2 Development of exports in the automotive industry

4.3 Current situation

4.4 Planned projects

4.5 Possible benefits for other emerging economies

4.5.1 Mexico’s spillovers

4.5.2 Spillovers to other emerging economies

4.5.3 Reasons why FDI not necessarily leads to positive spillovers

4.6 Porter’s Diamond on the national advantage

4.6.1 Background

4.6.2 The diamond model

4.7 The diamond model applied to the Mexican automotive industry

4.7.1 Factor Conditions

4.7.2 Demand Conditions

4.7.3 Related and Supporting Industries

4.7.4 Firms Strategy, Structure and Rivalry

4.7.5 Role of chance

4.7.6 Role of government

5 Conclusion

6 List of references

List of Figures and Tables

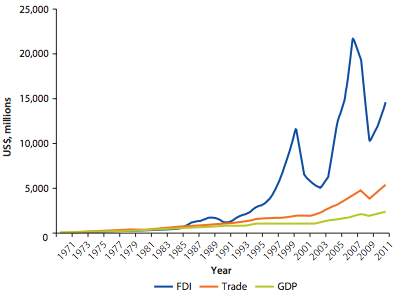

Figure 1: Global development of FDI

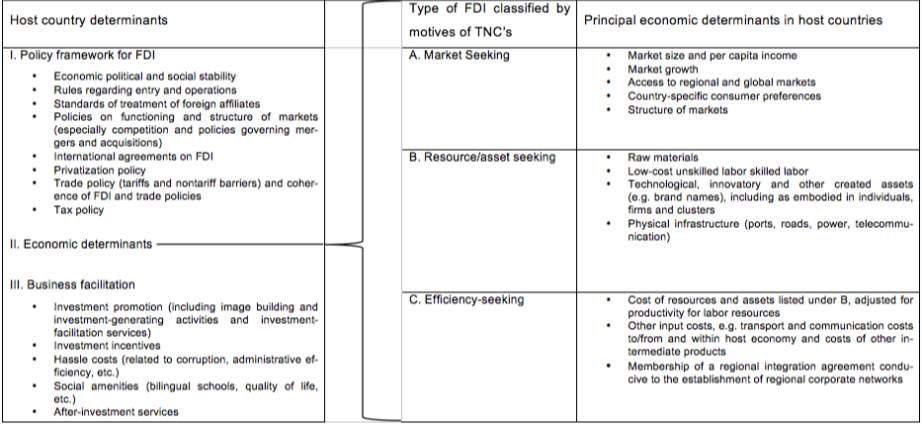

Figure 2: HI Automotive industry

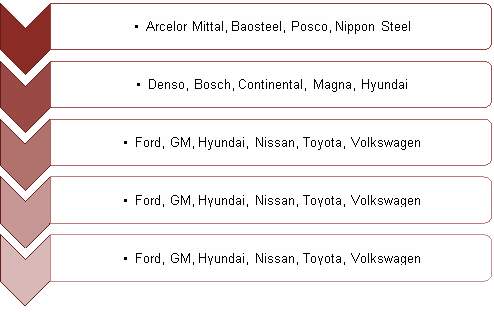

Figure 3: Difference between Horizontal and Vertical Integration

Figure 4: FTAs Mexico

Figure 5: Accumulative automotive production per units January-February

Figure 6: Accumulated automotive exports in units January-February

Figure 7: Light vehicle production facilities by brand and location

Figure 8: Determinants of national competitive advantage

Figure 9: Supplier network

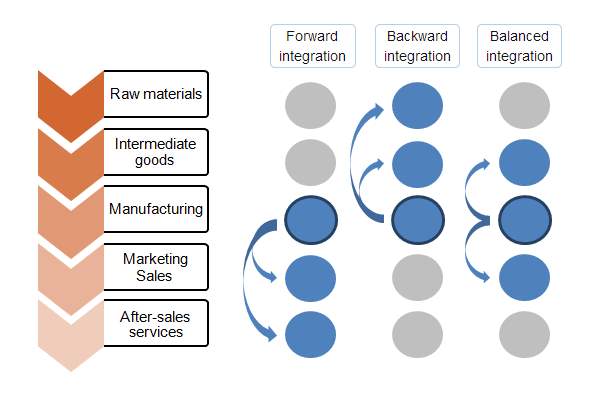

Table 1: Host country determinants for FDI

Table 2: Top 10 Export Commodities Mexico

List of Abbreviations

| AMIA | Asociación mexicana de la industria automotriz

Association of the Mexican automotive industry |

| CETA | Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement |

| EBC | Escuela Bancaria y Comercial |

| FDI | Foreign Direct Investment |

| FTA | Free Trade Agreement |

| GATT | General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade |

| GDP | Gross Domestic Product |

| GNI | Gross National Income |

| HI | Horizontal Integration |

| IMF | International Monetary Fund |

| MNEs | Multinational Enterprises |

| MXN | Mexican Peso |

| M&A | Mergers and Acquisition |

| NAFTA | North American Free Trade Agreement |

| NTBT | Non-Tariff Barriers to Trade |

| OECD | Organization for Economic Co-Operation and Development |

| ROW | Rest of the world |

| R&D | Research and Development |

| TTIP | Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership |

| UN | United Nations |

| UNCTAD | United Nations Conference on Trade and Development |

| VI | Vertical Integration |

| WTO | World Trade Organization |

1 Introduction

The global economic landscape is rapidly changing. Economic giants like the European Union (EU) and the United States (US) are increasingly challenged by emerging economies. A free trade agreement (FTA) currently under negotiations named transatlantic trade and investment partnership, or TTIP by its acronym might be a mechanism to slow down competition from emerging economies. It is a FTA between the EU and the US, with the aim to boost trade for both parties involved. Some of the emerging economies account for huge growth in terms of GDP, compared to sluggish growth figures within most parts of the EU. Conducting business globally, requires, in some industries, the involvement of emerging countries. TTIP is controversial as it will be counteractive for emerging economies. One heavily influenced sector in global context, which is highly competitive, will be the automotive industry. Multinational institutions impede automobile manufacturers business via new environmental regulations. While in some parts of the world, for example the EU and the US, the automotive industry tends more towards hybrid and sustainable cars, other parts of the world seem not too bothered. What is universal is that the competition level rises. However, competition is associated with more opportunities. MNEs with expertise in their home countries seize these opportunities to expand worldwide. Especially expertise from German and Japanese automobile manufacturers is highly demanded. Besides German expertise also global players like Ford, Toyota, Nissan, Peugeot, and a lot more are seizing their opportunities almost everywhere. They realize this in form of investments, so-called Foreign Direct Investments (FDI). Emerging countries indicate enormous growth opportunities for them.

1.1 Research Objectives

Mexico is the perfect example for successful foreign investment, especially its automotive industry, accounting for double-digit growth figures compared annually. As a matter of fact the Mexican automotive industry is, currently, the most successful of its kind in whole Latin America. Acquired knowledge gathered during the last decades in the Mexican automotive industry is valuable, and can serve as helpful input for other emerging economies. In order to understand the bigger picture, firstly the financial instrument FDI will be discussed, followed by a brief overview of the macroeconomic and automotive landscape of the nation. After providing the readers with basic knowledge, a discussion of macroeconomic effects and a competitive analysis of the Mexican automotive industry will close the work.

1.2 Research Questions

The considerations mentioned above can be summed up in the following research questions:

- Why did so many car manufacturers decide to make FDIs in the Mexican automotive industry?

- How did the Mexican automotive industry benefit from FDIs?

1.3 Methodology

The author chose a two-folded approach to gather information. The vast majority of the research was conducted by secondary research, as a lot of topic related information was available online. Consequently, secondary qualitative data was carefully selected by reviewing journals, existing academic papers, articles, webpages of official institutions like the Mexican secretariat of economy, International Monetary Fund (IMF), Organization for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD), World Bank, United Nations (UN) and business related magazines. Moreover, the Austrian chamber of commerce provided the author with the latest branch report about the Mexican automotive industry, which was a valuable input. Additionally, secondary quantitative data was obtained by renowned databases in order to underpin the findings from the qualitative data.

Fortunately Mr. Irving Ilie Gomez Lara, economics lecturer from Escuela Bancaria y Comercial (EBC) Mexico City, Campus Reforma, was willing to contribute with his knowledge to make this paper more valuable, including local insights.

1.4 Limitations

The research was focused on Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) in the Mexican automotive industry. Therefore this thesis has multiple limitations. Firstly it is focused on one financial instrument only, FDI. The term FDI will be explained in order to enable readers with a basic understanding of this investment form. Still, FDI will not be discussed in detail, meaning without further explanations of legal frameworks, laws, etc., as this would go beyond the scope of this paper. It rather should provide a general overview. Secondly it is geographically limited as the discussed topic solely focuses on Mexico. Thirdly it is limited to the automotive industry only, not considering FDIs in other sectors in Mexico. Therefore, the most relevant factors are analyzed in order to explain how foreign investments can contribute substantially to this specific industry, that make a country prosper and its connected network effects.

1.5 Structure of the work

At first this thesis takes a look at FDI, how MNE have been using this financial tool in the Mexican automotive industry. Further, this paper will continue with an overview about the industry and the nation as a whole, displaying the FDI made in this area and, consequently, how the automotive industry developed. The information will be illustrated with graphs and examples of car manufacturers. In the last part of the paper, learnings gathered from the example Mexico will be stated, and possible linkages to other emerging markets are discussed. This includes a competitive analysis of the automotive sector in form of Porter’s diamonds analysis. As a result useful knowledge that might be beneficial for other developing countries in regards to FDI will be presented.

2 Foreign Direct Investment (FDI)

In context of the work, the following definition of FDI will be used. Foreign direct investment (FDI) is an investment category that reflects the objective of establishing a lasting interest by a resident enterprise in one economy, or a direct investor, in an enterprise, or direct investment enterprise which is resident in an economy other than that of the direct investor. The lasting interest implies the existence of a long-term relationship between the direct investor and the direct investment enterprise and a significant degree of influence on the management of the enterprise. (OECD, 2008)

The threshold value for foreign equity ownership that is used to determine the existence relationship of direct investment differs across countries. In some countries the threshold point is not specified, but depends on other determinants such as if an investing firm has an effective voice in a foreign firm, in which it has an equity stake. The differences in the threshold value used is relatively small, regarding the quantitative impact, owing to the large proportion of FDI, which is directed to majority-owned foreign affiliates. The threshold, expressed as a percentage value of the participation by the direct investor, determines if effective impact in the management of the enterprise is given. (UNCTAD, 2003) The threshold value that is normally applied regarded FDI is if a direct investor owns at least 10 percent, but not more than 50 percent of the direct investment enterprise. The percentage indicates if an investor is considered to have influence over the management of a certain enterprise, hence if a direct investment relationship exists. (OECD, 2008)

The differences in the threshold value used is relatively small, regarding the quantitative impact, owing to the large proportion of FDI, which is directed to majority-owned foreign affiliates. (UNCTAD, 2003)

Nevertheless, the methodology as defined by the OECD recommends strict application to ensure statistical consistency across countries, and suggests to not allow any qualification of the 10 percent threshold. (OECD, 2008)

2.1 FDI in developing countries

Developing countries are labor-intensive countries, but scarce in capital. (Schekulin, 2013) Unfortunately developing countries’ internal capital resources are often not sufficient to overcome their saving investment gap, limiting the level of domestic investment. As a result they turn to foreign investors to acquire more capital. (Picardo, 2014)

During the past two decades developing countries started liberalizing their national policies and to establish more open regulatory frameworks for foreign investors. During 1990 and 2011 global FDI more than eight-folded. According to a report of the World Bank, this was 250 percent faster growth than the global gross domestic product (GDP) and 60 percent fast than global trade growth during the same time period. (Farole, Thomas; Winkler, Deborah; eds., 2014)

Figure 1: Global development of FDI

Source: World Bank

Liberalizing measures include loosening the market entry rules and foreign ownership rules, to ensure better functioning markets and to improve the standards of treatment accorded to foreign companies. Policies are vital, because FDI will simply not be made where they are forbidden or impaired by governments. If, however, governments change their policies regarding FDI, whole nations or group of nations can benefit from it. Changes granting greater openness allow companies to establish affiliates in the respective country/location. These changes do not guarantee that they will do so. On the contrary, changes towards less openness will surely reduce a country’s attractiveness towards FDI. (IMF, 1999)

This represents a challenge for developing countries. The better they can develop and match factors determining FDI location with a corporation’s strategy, the more likely it is to attract investment by the respective country. Policies, which are intended to bolster national innovation systems as well as encourage spread of technology are of major interest, as they underline potential to create assets. (ibid.)

2.2 Components

FDI consists of three components, namely equity capital, reinvested earnings, and other capital. Other capital mainly consists of intra-company loans. (Piana, 2005)

- Equity capital is money that is not repaid to investors, but staked by the owners through purchasing ordinary shares, a company’s common stock. (BusinessDictionary, 2007)

- “Reinvested earnings comprise the direct investor’s share (in proportion to direct equity participation) of earnings not distributed as dividends by affiliates, or earnings not remitted to the direct investor. Such retained profits by affiliates are reinvested.” (United Nations, 2007)

- Intra-company loans refer to long-term borrowing and lending from direct investors to the affiliate in a host country. This usually happens without the intention of asking the money back, as the purpose of FDI is more long run oriented. (Piana, 2005)

2.3 Determinants

Whether or not an economy is attractive for FDI depends on several factors. In general open economies with a skilled workforce and good growth prospects tend to attract larger amounts of foreign direct investment than closed, highly regulated economies. However this definition is too broad in order to derive any real determinants. (Schekulin, 2013)

More specifically there are 3 big groups of host country determinants in FDI:

- Policy framework for FDI

- Economic determinants

- Business facilitation

On the following page specific host country determinants, as defined by the IMF are displayed as table 1

2.4 Host country determinants for FDI

Table 1: Host country determinants for FDI

(Based on: (UNCTAD, 1998, p. 91)

2.4.1 Policy framework for FDI

A nation’s policy framework is highly important to attract FDI. How countries deal with policies towards international investors have a major impact on potential foreign investment decisions. One part of this determinant is the overall economic, political and social stability of a host country. Furthermore, present rules regarding entry and operations as well as standards of treatment of foreign affiliates is decisive for foreign investors. Moreover, different kind of sets of policies including the functioning and structure of markets, especially regarding competition and policies concerning mergers and acquisitions (M&A), privatization policies, trade policies, including tariffs and non-tariff barriers to trade (NTBTs), the coherence of FDI and trade policies and tax policies. Of course, international agreements on FDI are also an important coefficient in this context. (UNCTAD, 1998)

2.4.2 Economic determinants

Determinants that attract investments to particular locations like large host country markets, cost advantages, a flexible labor force or abundant natural resources continue to be important. However their relative importance is changing as MNEs increasingly engage in new strategies, to further improve their competitiveness. Reasons for this are for example rising globalization and a constantly liberalizing global economy. Due to a liberalized landscape across the world, technology flows and FDI, firms nowadays have a facilitated access to markets for goods and services, as well as to immobile factors of production. The downside of a more liberal world economy is that competition in previously protected markets is vastly higher, which might force firms to leave a host country and seek new assets, markets or resources abroad. (IMF, 1999)

Simultaneously technological progress facilitates coordination of international production networks for MNEs. Increasingly, MNEs focus on developing portfolios of locational assets including HR, market access and infrastructure in order to enhance their competitiveness. Foreign investors seeking to invest in a host country do not just take the mentioned determinants for granted, but are more likely to look for a combination of different factors like cost reduction, and created assets which facilitate to maintain a competitive edge and larger markets. These created assets include communications infrastructure, innovative capacity, marketing networks and technology in order to remain competitive in a constantly changing world. The higher emphasis on these assets represents an important change among FDI determinants in a globalizing and liberalizing global economy. (ibid.)

2.4.3 Business facilitation

Companies deciding for FDI are looking for a favorable environment for future business purposes. The conditions in a host country should be supportive for investments or, in other words facilitate business. One major incentive for foreign investors is a facilitated investment environment. (UNCTAD, 2009, p. 110) Facilitating measures include for example monetary incentives, investment promotions and post-investment services, improvements in social amenities, as well as measures that minimize hassle costs for foreign investors. Social aspects also should be considered like bilingual schools for Expats families, and the current quality of life in comparison with the host country. Post-investment services are supporting further investments, as existing investors are encouraged for reinvestments. Fiscal or financial incentives are also a mean to attract investments, although they typically range after investors’ location decisions, and when the most important variables, the economic determinants, are in place. (UNCTAD, 1998)

2.5 Classification of FDI

2.5.1 Horizontal FDI

This type of FDI is most likely to involve MNE that produce the same product/-s, or offer the same services in several countries. In this case the local plant should primarily serve the domestic market, and in some cases, markets nearby. This strategy aims to strengthen a company’s position within their industry. (Strategic Management Insight, 2013) The biggest benefit associated with this form of FDI is that transportation costs are reduced substantially and a facilitated access to a foreign market. (Protsenko, 2003)

Horizontal integration (HI) may be especially effective if a MNE competes within a growing industry, and economies of scale would have a significant effect. Furthermore, if competitors lack of some capabilities, competencies, resources or skills that the company already possesses, HI is recommendable. (Strategic Management Insight, 2013) An example for the automotive industry would be the following:

Figure 2: HI Automotive industry

Raw Materials

Components

Assembly

Importing/Exporting

Marketing and Sales

Based on: (Strategic Management Insight, 2013)

2.5.2 Difference between horizontal and vertical FDI

The difference between vertical integration (VI) and HI regards the number of activities and industries in which a company is engaged. HI includes a firm usually acquiring or opening up new affiliates in the same industry, conducting the same activity as in the home country. However, VI includes a firm engaging in activities other than in the current industry, and/or acquire their own supplier/distributor. (Chanda, 2010) An example for a VI would be for example a raw material supplier, also engaging in intermediate goods supply. A practical example for HI would be for example Volkswagen purchasing Porsche. (Strategic Management Insight, 2013)

Figure 3: Difference between Horizontal and Vertical Integration

Source: (Strategic Management Insight, 2013)

2.5.3 Vertical FDI

Vertical FDI occurs if a MNE invests in a business that plays a role of a supplier or a distributor, and to divide its production geographically by stages. The reason for this is to exploit differences in relative factor costs. Through this strategy MNE can gain more control over their industry’s value chain. In this context the question for firms is, whether a company should compete in one or many industries. In other words, perform one or many activities along their industry value chain. (MyOwnBusiness.org, 2011)

Before deciding for a VI, companies should consider potential costs and the scope of the respective activity. If manufacturing costs inside the company are lower than buying the product in the market place, this strategy is disbursing. However, engaging in several industries should not weaken current competencies and work load. A larger number of activities are harder manageable, than focusing on some few. (Strategic Management Insight, 2013)

2.5.3.1 Forward integration

If a company engages in activities after the manufacturing process, either sales or aftersales, it follows a forward integration strategy. Companies do that to achieve higher economies of scale and to increase their market share. As a result many manufacturing companies are selling their products directly to customers via online stores. This way they can save considerable amounts of money by bypassing retailers. This strategy is recommendable in case there are few high qualitative distributors available within the industry. Moreover if retailers have high profit margins, are unreliable or unable to meet a company’s distribution needs. Bypassing retailers makes sense in order to get self-sufficient in the long-term. Furthermore if the market is young and unreliable forward integration is an option. (McKinsey, 1993)

2.5.3.2 Backward integration

In case a manufacturing company starts to produce intermediate goods in order to bypass previous suppliers, or acquires its previous suppliers, it follows a backward integration strategy. Companies do that to increase its efficiency and secure stable input of resources. This strategy is beneficial if a firm has necessary resources and capabilities to manage the new business. Moreover if current suppliers earn high profit margins, cannot supply the required input or are unreliable. Another factor is the input price. If input prices are unstable backward integration makes sense in order to not be dependent on suppliers. (ibid.)

The combined version of the two integration forms discussed above is called balanced integration (Strategic Management Insight, 2013).

2.6 Greenfield Investment

This strategy involves a resident enterprise from one country setting up its own factories and plants from scratch in another country. MNEs like McDonalds, Starbucks, etc. like to choose this approach when expanding abroad. (Investopedia, 2006)

This advantages associated with this investment strategy are for example that

enterprises can choose their new location more strategically. Firms are able to control their staff better, as they do not takeover former personnel from an acquired company. This is also linked with the control over a certain brand. Employees that were part of a company acquisition might not be committed to work for another brand. Starting from scratch facilitates a firm’s intention to impose their values to the staff and form solid commitment to the company and its products or services. Furthermore the commitment to the market is solid. (TCii, 2012)

However, this strategy also brings along some downsides. First of all this approach is likely to cost more. Competition differs between countries. Still, to overcome any kind of competition after a new market entry is likely to be difficult across the globe. Market access, and in broader context, the entry process potentially can take many years to succeed. Additionally entry barriers can be costly and local governmental regulations might put MNEs at a disadvantage on short-term view to complicate the market entry. (ibid.)

In the case of Mexico’s automotive industry most car manufacturers like VW, Audi, Kia, Chrysler, BMW, just to name a few decided for the Greenfield Investment strategy. This has made these firms characterize whole cities like Puebla where even signs can be found in German language.[1]

2.7 Brownfield Investment

This strategy involves a resident enterprise from one country acquiring an existing foreign enterprise in the country of interest, instead of building own factories from scratch. This means, compared to Greenfield Investments, short-term cash flow. However it does not necessarily guarantee stability on mid- or long-term view. According to TCii Strategic and Management Consultants do 50 percent of merged businesses never achieve their projected financial and market goals. (TCii, 2012)

Nonetheless, this investment strategy is beneficial in certain points of view. One major benefit is market access in an already established sector for a foreign investor. The present labor force is skilled and does not necessarily have to be re-introduced to machines. The acquisition of a company includes absorbing its technology, clients, vendors and licenses. Negotiations usually occur at top level. Therefore usually the target company handles licensing and compliance. The investor has instant branding, as no further introduction of a new brand is required. Moreover, buying up a foreign enterprise means eliminating one competitor. Additionally the knowledge base increases, with local insights and valuable information. (Online Academy for IAS Preparation, 2013)

On the contrary there could be hidden surprises, which might take years to ascertain. Local management has to be trained and familiarized to the new approach and company philosophy. There might be some favors and concessions assumed under the current company structure. Potentially the target firms’ technology is outmoded. Branding might not be favorable to the headquarter ideals. Acquiring a company is cost-, and time-intensive and company cultures might not be very well adaptable. (TCii, 2012)

One good example of Brownfield Investment was made in 2008 by TATA motors. In this M&A, the Indian multinational automotive manufacturing giant acquired Jaguar and Land Rover from Ford. (Investopedia, 2012)

3 Attractiveness of FDI for car manufacturers in Mexico

This section will describe the attractiveness of Mexico for foreign investment of carmakers. In order to answer this question, it is beneficial to give the reader a brief economic overview of Mexico, including the historical development of the country and the current situation regarding FTAs. This is important, as Mexico is the country with most FTAs signed globally. Moreover, it reasons why MNEs invest in the Mexican automotive industry, and states the benefits for Mexico derived from FDI as well as remaining challenges. Finally a brief discussion is focused on the possible threat of TTIP for the Mexican automotive industry.

3.1 Economic overview of Mexico

Mexico is Latin Americas second largest economy after Brazil. The World Bank classifies Mexico as a developing country in the upper-middle income economy group. Middle-income group countries are defined by per-capita Gross National Income (GNI) ranging from US$ 4126 to US$ 12745. In the case of Mexico the GNI accounts for US$ 9940. (World Bank, 2015)

Mexico’s economy is highly export-oriented. In 2014, merchandise exports increased by 4.61 percent reaching US$ 397.5 billion. The US was by far Mexico’s main export partner and accounted for 80.22 percent of total exports, followed by Canada accounting for 2.68 percent. Around 5 percent of Mexican exports are destined to the European Union, with Spain being the highest recipient with 1.5 percent. China also accounted for 1.5 percent. Exports within the Latin Integration Trade Association (ALADI) accounted for 4.57 percent. The main partners in this context are Brazil and Colombia with both an export share of 1.19 percent. Chile has been gaining momentum with stable annual growth and a current share of 0.54 percent of Mexican exports. Because of the high share of trade with the US, trade performance was heavily influenced. The local market recovered slowly after the crisis, accounting for weak economic growth rates. (Secretariat of Economy Mexico, 2014)

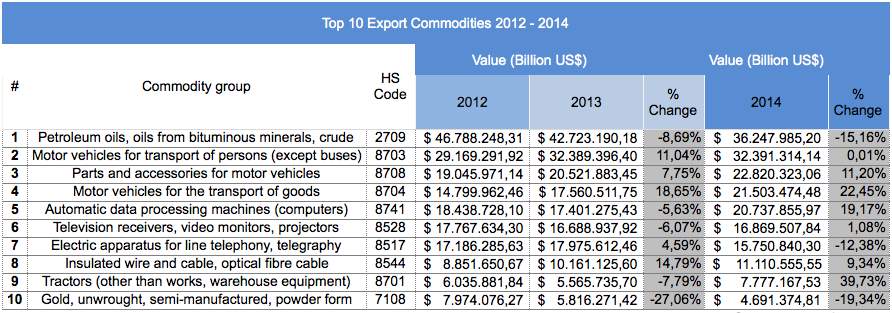

83 percent of total exports are manufactured products, followed by oil and oil products, which account for 13 percent. (Trading Economics, 2015) Table 2 displays Mexico’s top 10 export commodities during the time period from 2012 to 2014 and the annual percentage change. While the typical Mexican export commodity: Petroleum oils and oil products show annual declines, is it vice versa with automotive related products. Motor vehicles for transport of persons (except buses), parts and accessories for motor vehicles, motor vehicles for the transport of goods, as well as tractors account for huge growth, partially double digit growth in percentage.

Table 2: Top 10 Export Commodities Mexico

Based on: (UN Comtrade Database, 2015)

The Mexican economy gained momentum in the last quarter of 2014. The reason for this gain was solid growth in manufacturing, construction and services. This compensated less favorable economic activity in the mining sector. Business activities moderated in the manufacturing sector during the beginning of 2015. Economic growth is overall stable, but currently weakened due to unstable oil prices. At the beginning of March, the local government stated that the initial growth figures might have to be adjusted if oil prices do not recover. (Focus-Economics, 2015)

Mexico suffered hard from the financial crises of 2008 and experienced the worst recession since 1930. In 2010 FDI increased almost 30 percent in the first half of the year compared to 2009. (BBC, 2015) Despite Mexico experienced a cyclical downturn after the crisis, current economic activity is showing signs of recovery. Growth figures fell to 1.1 percent in 2013. 2014 started weaker than expected which led to adjustments of growth prospects to approximately 2.5 percent. Due to strong manufacturing exports and public spending, recovery is more likely to boost economic activity, leading to growth expectations of approximately 3.5 percent. Private investment, especially in the energy sector and infrastructure are likely to drive growth in the near future. Still, productivity effects will probably be evident over the course of the next decades. (World Bank, 2014)

The president Enrique Peña Nieto passed on 11 structural reforms since he became president. 6 of these reforms are focused on increasing growth and productivity in the fields of labor, education, competition policy, financial sector, telecommunications and energy. Attention will shift in 2015 towards bringing these reforms into action. The legislative framework, which is necessary for the structural reform agenda is largely in place. Possible delays might occur due to the mid-term elections in July 2015, which potentially will renew parts of the Mexican political landscape. Despite some outstanding issues Mexico seems on the right track towards a promising future. (ibid.)

3.2 Historical development and adjustments made by the Mexican government

Mexico is today among the most open countries regarding trade liberalization. However, this was not the case until some decades ago. Until the 1980s Mexico maintained to a strict protectionist trade policy in order to be independent and promote domestic growth. Part of these policies was import substitution in the 1930s containing general protection of the whole industrial sector by restricting foreign investment and controlling the exchange rate. Moreover, the oil industry was nationalized at this time. This strategy was not that favorable as it turned out in the 1980s, where Mexico experienced a series of economic challenges. The Mexican economy was at the edge to collapse, due to a debt crisis in 1982, where foreign debt obligations could not be met anymore. (Villareal, 2012) Consequently, Mexico started in late 1982 to gradually liberalize the economy and abandoned the import substitution model. The local government sold off a lot of public enterprises, deregulated several aspects of the economy such as banks, financial institutions, telecommunication and transportation. Moreover, these measures included liberalizing Mexico’s trade policies to eliminate trade barriers and attract FDI. During 1983 and 1984, 16.5 percent were excluded due to import permits. Liberalizing efforts led to a reduction of average tariffs to 22 percent. (Puyana & Romero, 2006)

In 1986, Mexico assured further trade liberalization measures by acceding to the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT). Shortly afterwards Mexico entered into its first FTA in goods with Chile. The liberalization efforts led to discussions with the USA about possible formation of a FTA during the early 1990s. Canada also joined negotiations, resulting in signing the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) in December 1992. NAFTA was, compared to the Mexico-Chile FTA, much broader in regards to trade in services, government procurement, dispute settlement procedures, and intellectual property rights protection. In the late 1990s, the original FTA between Mexico and Chile was complemented with similar provisions as NAFTA. More FTA-negotiations were conducted successfully and made Mexico one of the most liberal countries on global scale. (Villareal, 2012) The results of an opened economy in terms of trade were outstanding. Between 1980 and 2000 exports accounted for an average growth rate of 7.9 percent, 2 percent more than during 1940 and 1982. (Puyana & Romero, 2006)

3.3 FTA current situation

Mexico has currently 10 FTA including 45 countries, 30 Agreements for the Reciprocal Development and Protection of Investment and 9 agreements for limited scope in the framework of the Latin-American association for integration. Furthermore, Mexico participates actively in multilateral and regional forums like the WTO, OECD the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) and the Latin-American association for integration. (Secretariat of Economy Mexico, 2014) As the vast majority of exports are directed towards the USA and Canada, the NAFTA represents the most important FTA for Mexico. The USA represents Mexico’s most important trade partner accounting for more than 70 percent of its exports and 50 percent of its imports. Despite the fact that the USA are Mexico’s most important trade partner, liberalizing the markets more and, increasing the number of FTAs should make Mexico more independent. (Villareal, 2012) In figure 4 you can see a list of countries that have signed FTAs with Mexico.

Figure 4: FTAs Mexico

Source: (PwC Mexico, 2014)

3.4 Reasons why to invest in the Mexican automotive industry

Probably the main reason to invest is that Mexico is the country, which has signed most FTA globally. This is a major factor facilitating exports of vehicles as well as automobile parts. (PwC Mexico, 2014) Mexican labor costs are very competitive and have, compared to, the US substantial cost advantages. According to the Wall Street Journal, the minimum wage in Mexico as of April 2015 is 70 pesos per day. The equivalent in Euros is approximately € 4.32. (WsJ, 2014) Furthermore the country is economically stable and has some projects in place, which will increase the situation if implemented successfully. Mexico’s geographic location is excellent for export purposes to the main markets in the world. With 92 ports geographically distributed over the whole country Mexico is accessible from all directions. The main ports are the port of Manzanillo, Lazaro Cardenas, Altamira and Veracruz. (Trade and Logistics Innovation Center, 2013) Due to the proximity logistic costs to the world’s biggest automobile market, the US, are lower compared to other supplying countries. Mexico is well experienced in manufacturing automobiles, components and parts. The automobile sector has the latest efficient and modern installed capacity for automobile production worldwide. Moreover the capacity is very flexible and highly technical, enabling to manufacture several models of cars. (PwC Mexico, 2014) Additionally due to the higher demand in the automotive industry there are colleges and universities, which are offering industry-tailored study programs like automotive engineering. (El Financiero, 2014)

3.5 Benefits for Mexico derived from FDI

Mexico benefits from FDI in several ways. Mr. Gomez Lara, economics teacher at the EBC Mexico City, affirms benefits for his nation. MNEs boost economic activity, resulting in industrial clusters and specialization of production. Moreover, contributes FDI significantly to the GDP and creates thousands of jobs. (Gomez Lara, 2015)

Due to its liberal position, competitive advantage and openness to world markets FDIs are incrementing annually. This is connected with job creation, both direct and indirectly (OECD, 2001) This statement is affirmed by Eduardo Solís, president of the Mexican automotive industry association (AMIA). He stated as cited in El Economista, that the Mexican automotive industry has created more than 1 million one hundred thousand jobs. This number will even increase in the next few years as MNE seek more investments in either current plants or further expansions in Mexico. (El Economista, 2015)

Furthermore, cash inflows can be directly associated with technology transfer. This enables Mexico to get newer technology, which otherwise would hardly be available in the country. Better technology leads to the adaption of new products in the current production assembly, which in turn results in export opportunities. Local workforce benefits a lot as MNE offer trainings for their employees. Investments are made by the purpose to increase productivity, which, in the long-term, leads to higher wages. Moreover do FDI related firms pay on average 50 percent higher salaries than the national average (OECD, 2001)

In the automotive industry MNE car manufacturers pay considerably higher wages than the national average. According to Huberto Juárez as cited by thenews.mx some Japanese car manufacturing plants in Mexico pay $ 6 to $ 10 a day, which is above the nations minimum wage of approximately $ 4.5 per day, depending on the region. Other manufactures as VW even pay wages twice as high. (The News, 2015)

3.6 Remaining challenges for Mexico

The benefits of FDI are outweighing the detriments. Mexico as a country, and especially, the Mexican automotive industry is highly dependent on the US market. The interdependence has helped Mexico to advance in great strides economically. However, this is also associated with some downsides. The offer for vehicle renewal programs is low, which leads to progressive imports of used vehicles from the US. As a result internal growth is slowed down. Automobile – and automobile part manufacturers, as well as distributors are handicapped. In 2013 only, 7 million used cars were imported from the US to Mexico, compared to 8 million new cars sold during the same time period. (PwC Mexico, 2014) Another problem is that the average of total cars running in Mexico equals 16 years, compared to 11.4 years in the US. (Automotive News, 2014) As the majority of Mexicans cannot afford new or semi-new vehicles, most people are dependent on cheaper vehicle imports. Higher fuel consumption is directly connected with this issue, which in turn worsens the air quality in major cities like Mexico City. Unfortunately, the local government has not yet shown interest in developing programs to promote electric or hybrid cars. Mexico is internationally known for low security in huge parts of the country. The offer of competitive financing schemes is lacking. A better offer would enable an increase of the potential sales for new and semi-new car. Moreover improved financing schemes could be used to develop supply sources, which would benefit several industries. Programs to develop qualified technical labor for the automobile industry are present. Still, the employment offer will increase over the next few years as MNEs realize more projects and new investments throughout the country. Future struggles to obtain qualified labor force seem reasonable if not enough education possibilities will be provided. (PwC Mexico, 2014)

According to Mr. Gomez Lara the main challenge for Mexico to attract more FDI will be to offer investment security for foreign investors. Additionally the local infrastructure for transports is still lacking efficiency, and represents a moderate cost factor. By constructing new car manufacturing plants, Mexico should fit its strategic program of the automotive industry towards permission of necessary actions to orient and coordinate further development within the industry. Further, competitive benefits available like the access to high quality providers and the competitive – and specialized workforce in the automotive industry could be exploited better. The internal and external demand needs to be better suited in order to be adaptive, also to innovative technologies. Mexico is trying to create a specialized workforce by offering more customized university programs like for such as automotive engineering. However, tuition fees are quite high and hardly affordable for the general public. Still, as the country is known for its cheap labor force, bolstering a more specialized workforce in the respective industries like the automotive industry turns out as a success. (Gomez Lara, 2015)

3.6.1 TTIP and CETA as threat for Mexico’s automotive industry

TTIP by its acronym means Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership, which is currently under negotiations. It will be, once in place, the world’s largest FTA and investment treaty between the EU and the USA. The aim of TTIP is to remove regulatory trade barriers, which limit profits by MNE on both sides of the Atlantic. However as negotiations take place secretly and closed to the public, it is controversial. (Hilary, 2015)

CETA by its acronym means Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement. It is an international treaty between the EU and Canada. It is the first FTA between the EU and one major economy. Negotiations have already finished. However the European Parliament as well as the governments of the EU member states have to approve it before it can enter into force. (European Commission, 2014)

A more detailed discussion of TTIP and CETA would go beyond the purpose of this paper. Still, to say it in few words, both agreements have the goal to increase trade, create jobs and boost global economic growth.

A report by the Austrian Foundation for Development Research evaluated 4 studies regarding TTIP and the claimed benefits of the agreement. While TTIP economies are expected to benefit from the treaty, most other countries are likely to lose. Particularly economies, which have close trade relationships to Europe and the USA including Mexico, Canada, Norway and Russia, are likely to experience declines in real GDP figures. (ÖFSE, 2014, p. 9) Canada might be better off due to CETA, but trade relationships are still likely to suffer.

One of the mentioned studies expects negative real GDP change for emerging economies with a 2.8 percent decline in Latin America, 2.1 percent drop in Sub-Saharan Africa as well as a 1.4 decrease for LICs. (ÖFSE, 2014, p. 5) The EU has made a commitment to Policy Coherence for Development, or in other words to contribute to reduce and eradicate poverty. (Eurostep EEPA, 2008) Negative figures caused by the EU would mean a violation of this commitment. A TTIP impact study by the Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) predicts that intra trade within EU member states is expected to decline by € 72 billion, compared to an increase in exports to the US and the rest of the world (ROW) of € 187 billion and

€ 33 billion, meaning positive impacts for all regions. Assumptions of one study include export increases between 0.6 and 2.3. (ÖFSE, 2014, p. 6) The latter still seems quite humble compared to the US figure, though its occurrence remains questionable.

Precise forecasts of how CETA and TTIP will influence the Mexican economy are hardly possible. Still, negative impact is likely to occur. One part of the CEPR scenario was how TTIP will influence motor vehicle trade. While in an ambitious scenario conducted by the CEPR forecasts an expected output in the EU to rise by 1.54 percent and even to decline by 2.87 percent in the US, total trade in this sector is expected to skyrocket. (CEPR, 2013) Exports from the EU to the US are expected to increase by 87 percent. Furthermore commercial activity between the two parties involved is expected to increase by 346 percent. The CEPR estimated, that this would generate approximately 43 percent of total changes in extra EU trade exports. (ÖFSE, 2014, p. 11) Summing up more goods will be exchanged, but hardly more will be produced.

If the small growth margin or ROW increase in trade will turn out beneficial for the Mexican automotive or the nation as a whole is questionable. Despite the fact that the treaties should boost global economic growth, most models and papers show quite the opposite. Furthermore if TTIP and CETA boost growth, then the change is so minimal that they real reasons for the planned treaties seem to be not only economically oriented.[2]

4 Development of the Mexican automotive industry with the help of FDI

4.1 Development of the industry

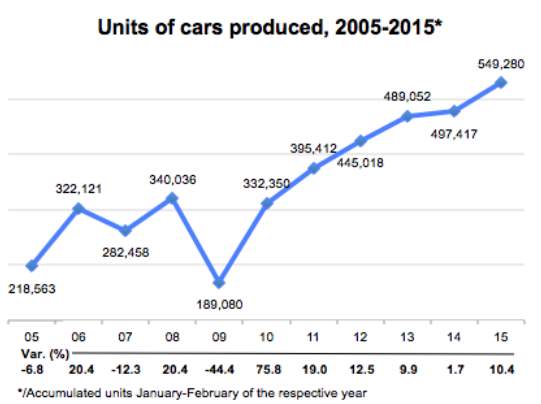

The Mexican automotive industry benefited substantially from FDIs. In figure 5 can see the increase during the first two months of the respective year during the first two months of the respective year. Average growth was 12.5 percent plus p.a. The output figure more than doubled comparing the year 2005 with 2015. Due to the dependency on the US and the financial crisis sales plummeted in 2009, after strong recovery in 2010.

Figure 5: Accumulative automotive production per units January-February

Based on: (El Economista, 2015)[3]

4.2 Development of exports in the automotive industry

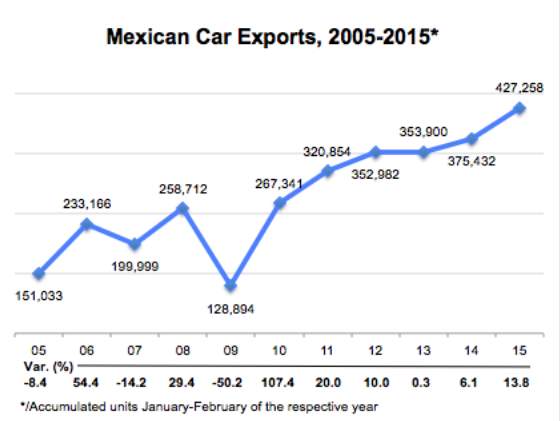

The export share even shows a more successful development like output figures. Automotive exports accounted for 151,083 units in 2005, an export share of approximately 69 percent of total automotive production. The figure for 2015 is expected to rise to 427,258 units, an export share of approximately 77 percent. In figure 6 you can see the development of Mexican car exports during the first two months of the respective year.

Figure 6: Accumulated automotive exports in units January-February

Based on: (El Economista, 2015)[4]

The production and sales figures during the first quarter were the highest in Mexican history recorded yet. 688,514 units were exported representing an increase of 13.6 percent compared to the previous year. (Portal Automotriz, 2015) Looking at export growth figures per regions, Africa accounts for the greatest growth with 58.3 percent, followed by Canada, Asia and the US accounting for 33.4 percent, 14.2 percent and 12.6 percent regarding additional units exported during the first quarter of 2015. (AMIA, 2015)

The principle export destinations remain the same. 70 percent of automotive exports went to the US, followed by Canada with 11.8 percent and Germany with 2.6 percent. (Autopistas, 2015)

4.3 Current situation

The current situation of the local automotive industry is record-breaking. Internal sales figures accounted for a 21.9 percent increase in March 2015 compared 2014. (AMIA, 2015) This is connected with positive development of one of Mexico’s main issues, car imports from the US. More than 90 percent of used cars were imported during recent years due to vague car import restrictions. The federal government, in cooperation with the secretariat of economy and finance introduced stricter import regulations to counteract unregulated imports. (Mexico News Daily, 2015) The consequences are remarkable. 25,272 units were imported during the period of January-February 2015, representing a decrease of 73.2 percent with regards to 2014. (Portal Automotriz, 2015) The problem is tackled by the government, but still not erased, as imported used cars account for 43 percent of the total new car sales in Mexico. (Mexico News Daily, 2015)

Banorte bank stated as cited in the Wall Street Journal that the industry is expected to further gain due to lower global gasoline prices. A stronger US dollar compared to the Mexican peso helps Mexican exports getting more competitive. Furthermore, with stricter import regulations for car imports in place, domestic demand is expected to further improve. (WsJ, 2015)

Currently there are 18 car factories in Mexico, making the country the seventh-biggest auto producer globally. (The News, 2015) Figure 7 displays the location of light vehicle production facilities with their location and brand. Most plants are located in northern regions as well as in central Mexico.

Figure 7: Light vehicle production facilities by brand and location

Source: (Automotive Meetings, 2015)

The number of employees in car manufacturing in Mexico has risen spectacularly since 2008. According to industry statistics and the local government as cited on thenews.mx automakers employed approximately 675,000 people by the end of 2014 compared to 490,000 in 2008, accounting for a 40 percent increase in jobs. The US automaker employment grew by 15 percent to approximately 900,000 during the same period. (The News, 2015)

4.4 Planned projects

Besides a currently stable automotive industry future prospects also look bright. The AMIA forecasts as cited on automotivemeetings.com that total unit output is expected to reach US$ 4 million units by 2018. (Automotive Meetings, 2015) IHS Automotive, a consulting firm, expects as cited on thenews.mx that the projects will result in a 50 percent output increase of the industry until 2022 nearly reaching the US$ 5 million mark. (The News, 2015) These growth prospects seem legit, when considering latest news. Almost weekly are car manufacturers or firms involved in the automotive industry announcing new planned investments or projects planned.

Lately Ford announced a US$ 2.5 billion dollar investment into two new plants to produce diesel engines and new transmissions. (Reuters, 2015) Toyota also decided for Mexico and against Canada. The management decided to shift the production of the Corolla into a new factory in Mexico, which will cost around

US$ 1 billion. The investments will create more than 5,000 jobs. (Detroit Free Press, 2015)

General Motors (GM), which produced approximately 131,000 vehicles in 2014, announced that they are going to invest US$ 87 million in San Luis Potosí state to expand their current output. (CNN, 2015)

BMW currently invested US$ 1.3 billion in a new plant in San Luis Potosí with planned start of production as of 2019. The Bavarians seem convinced of their decision, as they assigned the former manager of the BMW plant in Munich Hermann Bohrer as new general manager in San Luis Potosí. (Automotores-Revista, 2015) The plant in Mexico has a 20 percent cost advantage compared to a current plant in South Carolina. (WKO Austria, 2014)

VW announced to invest US$1 billion into their existing plant in Puebla. The investment will be used to expand current production capacities and increase their assembly line. By realizing this investment, Tiguan production will start in late 2016, and generate around 2000 more jobs. (Reuters, 2015)

The Canadian-Austrian car manufacturer Magna announced in March 2015 a

US$ 135 million investment in an additional plant in Queretaro. The planned manufacturing plant will already be the 30th plant of Magna in Mexico. Accumulated Magna employs more than 24,000 people in Mexico. (Magna International, 2015)

Audi invested more than € 1 billion into a new plant and infrastructure in San Jose Chiapas, Puebla, to produce their Q5 model with an annual capacity of 150,000 units. The German carmaker will create additional 3,800 direct jobs, as well as 20,000 jobs indirectly for suppliers, car body makers, etc. in the surrounding area. (Audi Media Services, 2015) According to Sean McAlinden as cited on thenews.mx producing the Q5 in Mexico saves US$ 6,000 per vehicle in tariffs, when shipped to Europe compared to producing it in the US. (The News, 2015)

4.5 Possible benefits for other emerging economies

4.5.1 Mexico’s spillovers

Mexico and Brazil are the two largest and economically very important economies in Latin America. Trade figures within Central America and Mexico have increased over the last two decades, as percentage of GDP. Still, the contribution of Mexico to intra-regional trade has been limited. Due to strong economic ties with the US, Mexico has insignificant linkages with Central American economies. (IMF, 2012) Central America accounted for just 1.23 percent of Mexican exports in 2014. Countries like Brazil and Colombia accounted both for 1.19 percent in the same year. (Secretariat of Economy Mexico, 2014)

Weaker linkages with Central and South America provide evidence that spillovers are small. Moreover, the fact that financial and trade linkages between Mexico and Central American economies are of minor influence, suggests that business cycle synchronization with economies in Central and South America mostly reflects external shocks rather than spillovers. (IMF, 2012)

4.5.2 Spillovers to other emerging economies

As seen at the example of Mexico FDI can be associated with benefits. One of the most important benefit in connection with FDI can potentially be made with economic spillovers. These effects have valuable potential that productivity gains arise from the diffusion of technology and knowledge from multinational affiliates to the local workforce and domestic firms. As a result they are fostering growth and development in the long run. (World Bank, 2014)

This can also include benefits that may accrue to domestic actors from linking into worldwide networks of multinational investors. If spillovers are dispersed from MNEs to domestic producers within the same industry they are so-called horizontal or intra-industry spillovers. If another industry is involved it is called vertical or inter-industry spillovers. (ibid.)

Positive spillovers are one driving force making emerging economies’ governments want to attract more FDI. They hope that attracting more FDIs will generate technological or learning spillovers, which in turn might be beneficial in other activities and industries. Exporting firms are likely to be technologically more dynamic and productive than companies that are focused on the local market. This is associated with selection effects, meaning that better firms are able to or choose to export. Consequently, export subsidies tend to have little impact on improvement in overall technological or productive capacity. Dani Rodrik argues in his paper about industrial policy for the twenty-first century, that in some cases, evidence of spillovers or externalities from FDI was not given at all – resulting in negative spillovers. Considering these circumstances, subsidizing foreign investors is not a rewarding policy for developing economies, as the compensating benefit is not necessarily given. It is more likely that income from poor country taxpayers is transferred into the accounts of shareholders in richer countries. (Rodrik, 2004)

According to the World Bank, spillover effects of FDI in developing countries do not necessarily have positive impacts in the short term, but have the potential to benefit local participants and supplies in the medium and long-term. (World Bank, 2014) This is due competition effects, meaning that domestic producers are exposed to compete with MNEs. The results are losses of domestic firms in the short-term. Still, in the long-term local domestic firms are likely to improve their efficiency and, hence, welfare. (Dictionary Central, 2012)

4.5.3 Reasons why FDI not necessarily leads to positive spillovers

Multinational affiliates are more competitive than their domestic counterparts, as their purposes are more export-oriented. This makes domestic linkages hardly possible. Incentives to attract MNEs might lead to less local integration, if for example local governments waive duties on imports, but value-added taxes still apply for domestic purchases. MNEs, make use of these incentives, which involve less domestic partners. Moreover, firms are less likely to involve local workforce in every division of their work force. Especially in managerial positions, where it is most probable that important knowledge spillovers take place, it is more likely that skilled labor is acquired from the home country. Still, this varies between countries and sectors. While in the Chilean mining sector 70-80 percent of workers in skilled positions are locals, African countries share ranges from 30-50 percent. In agribusiness in Kenya and Vietnam, local skilled workforce employed ranges from 75-85 percent compared to 60-75 percent in Ghana and Mozambique. (World Bank, 2014, pp. 248-249)

Moreover, less linkages with domestic parties is also reflected in engagement with local suppliers. Foreign investors are less likely to provide assistance to local suppliers. This is bad as local sourcing is very valuable in the short- and long-term. Technical assistance would help domestic firms to improve their supply chains, which improves the probability that they start exporting. (ibid.)

4.6 Porter’s Diamond on the national advantage

4.6.1 Background

In the 1980s, US industry was increasingly challenged by European and Japanese competition. Back then existing trade theories were able to explain economic contexts quite acceptable. However, some of the contexts were complex and hardly explainable with former existing theories. Michael Porter, Professor of Harvard Business School, concluded that classical trade theories were not able to fully explain why nations either gain or lose competitive advantage in a certain industry. His conclusion was followed by a study of ten major national economies covering half of the global exports in 1985. As a result he developed the Porters diamond, a theory model to assess the competitiveness of regions, nations, and states. (ProvenModels, 2009)

4.6.2 The diamond model

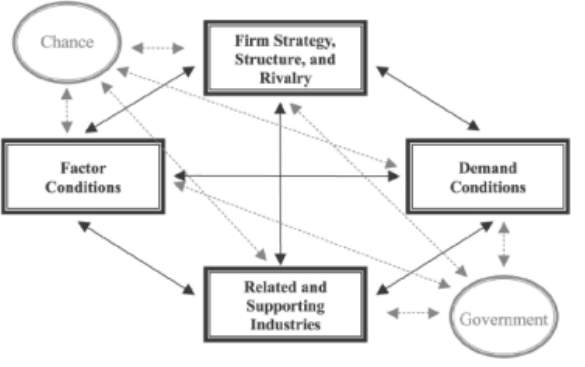

Porter defined a diamond shaped diagram to illustrate four main factors or dimensions of national advantage. The determinants are namely Factor conditions, Demand conditions, Firm Strategy, Structure and Rivalry, and Related Supporting Industries. Additionally, Porter defined two more factors that namely are chance events and the role of the local government. (ibid.)

These determinants construct the national environment in which firms are being established and compete with each other. Each determinant has an impact for achieving international competitive success. These are resources and skills available that are necessary to achieve competitive advantage in an industry, information available that enables opportunities that companies can seize and to define the direction in which a firms’ resources and skills are deployed. Continuously, it includes the aims of the owners, management and individuals of firms, and finally, pressure on firms to innovate and further make investments. (HBR, 1990)

In figure 8 you can see a graphical illustration of the determinants of national competitive advantage as defined by Michael Porter.

Figure 8: Determinants of national competitive advantage

Source: (Loughborough University, N.D.)

4.7 The diamond model applied to the Mexican automotive industry

4.7.1 Factor Conditions

This factor or diamond is concerned with available resources, including the infrastructure. Resources are divided into Human -, Physical -, and Capital Resources.

4.7.1.1 Human Resources

School penetration in Mexico experienced a significant upturn during the last decades. According to the OECD the number of students grew from approximately 3 million in 1950 to more than 30 million in 2007. (Santiago P., et. al 2012, p. 28) As a result illiterate population above 15 years increased from approximately 65.5 percent to approximately 91.5 percent during 1960 and 2005. (INEGI, 2011) Mexico has, as Barragán already argued in 2005, a strong base of engineers, technicians and a high level of productivity. This is partially due to trainings from car manufacturers like one manager of VW de Mexico confirmed in his study. (Barragan, 2005) The fact that foreign affiliates offer also local workforce trainings is very valuable to the local workforce. Mexico also makes more efforts to educate a larger number of engineers as mentioned before. Still, considering the amount of projects planned within the next decade, the problem to meet the demand of skilled labor remains problematic.

4.7.1.2 Physical Resources

According to the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) the main resources of Mexico are copper, gold, lead, natural gas, gold, petroleum, silver, timber and zinc. (CIA, 2014) In 2014 Mexico produced 2,459 barrels of crude oil a day compared to 8,652 barrels produced daily by the US. (EIA, 2014) Oil is the most important and valuable resource in the country, as it generates substantial revenues. Additionally oil also provides collaterals for loans. The national monopoly is held by Pemex, which estimates Mexico’s reserves are equivalent to approximately 50 billion barrels of oil, with an additional approximate 60 billion in unconventional resources. (EY, 2014) A huge part of Mexico’s exports are oil and gas related, which is also reflected in the nations exports. As shown in figure 3, oil and oil related exports account for most of the exported value. The geographical location of the country favors exports.

4.7.1.3 Capital Resources

FDI in the Mexican automotive industry is setting new records. Considering the projects mentioned before, foreign car manufacturers have announced investments of more than US$ 5 billion since the beginning of 2015. The upcoming investments, in combination with adjusted government principles focused on improving the current principles gives evidence that this factor will remain stable. One outstanding issue that should be addressed is lacking development in national research and development activities (R&D) activities. Several institutions offer now university programs designed to create an adequate workforce as mentioned in previous chapters. However, FDIs are rather focused on raising production capacities or the number of plants within Mexico, than investing in national R&D development. Michael Porter supports this statement arguing that the government should be involved in national R&D activities during initial stages. Despite initial assistance, main inputs that boost the competitiveness of industries should be originated from industry R&D activities. (HBR, 1990)

4.7.1.4 Infrastructure

Mexico has diverse means of transportation, which connect states located on the Atlantic coast with those on the Pacific, as well as northern with southern states. The transportation network within the country has been further built and modernized in recent years. As of 2014 it consists of a network of highways of approximately 133,000 kilometers and 76 airports, out of which 64 offer transnational flights, and more than 27,000 kilometers railroads. Moreover, 117 maritime ports are accessible throughout the country. 68 of them are container ports. Highways are the most used mean of transportation within Mexico. Former local governments have made efforts to improve the infrastructural situation constantly. The current government led by Enrique Peña Nieto takes further efforts towards a better and more efficient infrastructure. They announced in 2013 the so-called “Communication and Transportation Infrastructure Investment Plan”, which is aimed to foster Mexico’s position as a global economic hub. Planned investments of

US$ 45.3 billion during 2013-2018 should improve the infrastructure sectors of the country by attracting further investment. Transportation infrastructure should be further developed in regards to toll roads, ports infrastructure, railways and public transportation. (PwC Mexico, 2014)

This project should help Mexico to gain the previously lost position in the Logistics Performance Index, where Mexico was globally number 42 in 2012 compared to number 50 in 2014, and further improve the country’s global position. (World Bank, 2014)

4.7.2 Demand Conditions

Gathered information provides evidence of a significant market growth potential. The nation’s population is rapidly growing. In 2000 approximately 103 million people were living in Mexico compared to almost 124 million people in 2014. Population forecasts expect this number to rise to more than 131 million people by the end of the decade. (Worldometers, 2012) The increasing demographic structure is expected to shift towards age groups with higher purchasing power and, hence, create millions of potential customers. According to the Economist Intelligence Unit as cited in the report of “Assessing an investment in the Mexican automotive industry” by KPMG, future growth will continue to be export-oriented. Additionally the local market has big potential for growth, with vehicle penetration of one quarter in comparison with other OECD countries, meaning room for improvement. (KPMG Mexico, 2012) With regards to the automotive sector, internal sales of cars accounted for just 57 percent in 2014 as mentioned previously. While domestic demand increased by 21 percent at the beginning of 2015, this number is expected to further improve throughout the year. (WsJ, 2015) Although the minimum salary was adjusted just by the beginning of April 2015 to $ 70 Mexican Pesos (MXN) per day, income levels still remain low. The average salary is accounts for $ 295 MXN per day, which is the equivalent of approximately US$ 20. (Trading Economics, 2015) The low wages level is especially beneficial for the local automotive industry representing huge cost benefits in comparison to their neighboring countries in the north.

4.7.3 Related and Supporting Industries

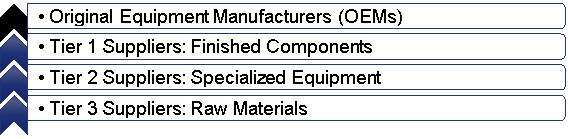

This third dimension refers to existing related, or supplier industries in a given country. The absence or presence of these industries that interact horizontally and vertically with the targeted sector is a basic factor. (Bakan & Dogan, 2012) Automotive sectors are for example dependent and in closely related to its suppliers. Unlike other countries that have to import a lot of car parts and components, Mexico is able to manufacture parts and components itself and acts as a global supplier to major carmakers. (ThomasWhite, 2010) ‘Parts and accessories for motor vehicles’ are the third place in regards to Mexico’s exports and account for approximately US$ 22.8 billion. (UN Comtrade Database, 2015) The supply industry, including auto parts consists of three levels of production as displayed in figure 9.

Figure 9: Supplier network

Based on: (Lauridsen, Lerdo de Tejada S., Peterson, Puyana, & Rosales, 2013)

To better understand Figure 9, Tier 3 supplies Tier 2 with raw materials, which in turn produces specialized components and equipment such as die casting, as well as machined – and plastic parts. Tier 2 suppliers in turn supply Tier 1 suppliers that manufacture finished components such as air conditioning systems, engines, or specific electronic components. Tier 1 supplier directly delivers the finished components to the OEMs. (ibid.)

According to the Executive President of the AMIA Eduardo Solís, as mentioned on mexicoautomotivesummit.com, Tier 2 carries especially big growth potential. This is due to the fact that 71 percent of the total demand for processes was still imported in 2014. Minimizing transportation costs will be one of the future objectives. Purchasing Director of Ford Mexico Leo Torres states in the same article that supply-chain expenditures reflect a costs of 75 percent in a new vehicle. (Automotive Summit, 2014)

4.7.4 Firms Strategy, Structure and Rivalry

In the fourth dimension Porter advocates that three basic determinants impact the competitiveness of a given sector that are namely: firms strategy, industry structure and domestic rivalry effects. Whether or not a sector is domestically competitive will impact the need in productivity to engage with international competition. (Barragan, 2005) In the Mexican automotive industry, most of its output is produced to serve international markets. MNEs designed their manufacturing plants for global needs and specifications, meaning that automobiles and parts are exported worldwide. This international standard requirement in Mexico’s car manufacturing plants has helped the country to become an important export hub for finished automobiles and components. (Perez Debrand, 2005)

Domestic rivalry is present as every global major carmaker is present in the domestic market. Furthermore as discussed before, the vast majority plans to either further expand, or build new affiliates in Mexico.

4.7.5 Role of chance

This additional factor of the diamond model describes uncontrollable external events that may enable opportunities emerging from a reshaped industry structure. Disruptive impacts could be unexpected commodity price changes, radical technological innovations, or riots to name some examples. (ProvenModels, 2009) Mexico aims to be less dependent on the US. Efforts towards this goal were currently made, when government officials extended a vehicle trade agreement with Latin America’s biggest economy, Brazil. (Automotive Logistics, 2015) Regional integration with the common market for South America (MERCOSUR, Spanish abbreviation) would have potential for growth for both Latin America and to be less dependent on the US in the case of Mexico. (Perez Debrand, 2005)

4.7.6 Role of government

Governmental decisions are able to influence all of the previous dimensions of the diamond model. Successfully implemented principles can have major influences, especially when determinants of national advantage as discussed above are present and reinforced by the local government. (ProvenModels, 2009) As examined before the local government has made clear contributions to the current success of the automotive industry, such as the willingness to sign new FTAs, adjustments of local laws towards liberalization, and incentives for foreign investors. Furthermore, current governmental plans include new principles to be implemented soon to further attract FDI and continuously build upon Mexico’s competitive position in the global market. Additional projects in related industries will be realized to improve the infrastructure network of the country as a whole. This will also benefit the automotive industry, and facilitate business for foreign investors. (PwC Mexico, 2014)

5 Conclusion

Concluding, it can be said that FDI is crucial for developing countries, which will be even more on the rise in the near future. A changing demographic landscape in developing countries will result in bigger middle class on a global scale. Consequently, there are more potential customers for current economic leaders like some European countries, the US and Japan. These nations can use their expertise as competitive advantage. This will shift business purposes even more towards realizing economic activities in developing countries, altering FDI on a global basis. In this context, this paper examined FDI, using the Mexican automotive industry as an example and leading to the following research questions:

The first question concerns the “Attractiveness of FDI for car manufacturers in Mexico.” Mexico has high potential for foreign carmakers due to its openness, favorable market conditions and substantial cost advantages compared to other countries. Moreover, the nation’s geographic location is one of the cornerstones contributing to its success because of the proximity to the worlds largest car market, the US. Besides business opportunities in the north, the internal car market has huge growth potential, which is yet to be exploited by MNEs. Additionally, Mexico is well accessible through different means of transportations and connections to the main seas of the world making cargo options more doable and flexible. The fact that Mexico is the country accounting for most FTA globally in combination with cheap, but good, labor force, makes the nation an excellent export hub for automotive business purposes. Local market conditions are favorable for foreign investors due to a dedicated government. Still, there is room for improvements regarding security for foreign investors and a costly transportation infrastructure. The local government is continuously working on improving policy principles to further ensure stable investment inflows. Measures include an investment plan to improve the overall infrastructure and reduce transportation costs, which represent an issue for carmakers. Cost advantage is another major factor that drive MNEs’ want to realize more business in Mexico. The possibility to manufacture high quality products for a fraction of the costs elsewhere led to affiliates of the most prestigious and best carmakers worldwide in the country.

The second research question examines the “Development of the Mexican automotive industry with the help of FDI.” Foreign investment and a historically successful manufacturing industry were crucial factors that have helped Mexico to establish today’s well-functioning automotive sector. After liberalizing its macroeconomic policies in the 1980s it was especially FDI from the US that has helped Mexico to overcome the investment gap and had a major impact during early stages of development. Approximately a decade later, NAFTA led to foster the economic connection between Mexico and the US. Ever since the signing of this agreement significant contribution has been made to the Mexican automotive industry. Besides the US, foreign investors from the most successful carmakers including Audi, BMW, Mazda, Nissan, Toyota and VW have been seizing the opportunity to realize business in Mexico. The presence of high quality original manufacturers has made the country an international hub for the automotive branch, resulting in industrial clusters and benefits for the nation as a whole. FDI in this respective sector has created more than one million jobs, both direct and indirect. Growth was substantial within the last two decades and has made Mexico the current number one in automobile production in whole Latin America. Future prospects are bright, as the demand for car exports is not expected to slow down in the near future since carmakers continuously announce new investments. Just in 2015, projects worth more than US$ 5 billion were announced to further exploit the market potential.

TTIP will impact developing countries in the broader context of FDI and global trade. It is designed to increase business interactions between the EU and the US. However, this will result in less commercial activities with developing countries and the ROW. Consequently, these nations will face lower growth and have to seek other opportunities, which might be regional integration. Despite the fact that FTAs are in principle designed to benefit both parties involved, TTIP does hardly provide evidence to do so. Therefore, the author concluded that TTIP is just an attempt to temporarily impede fast growing developing economies and, hence, maintain the West powerful. Personally, the author thinks that TTIP will not be as beneficial as promoted by the European Commission in the long run.