History of The Congo and An Examination of The Congo Wars

Info: 20761 words (83 pages) Dissertation

Published: 8th Sep 2021

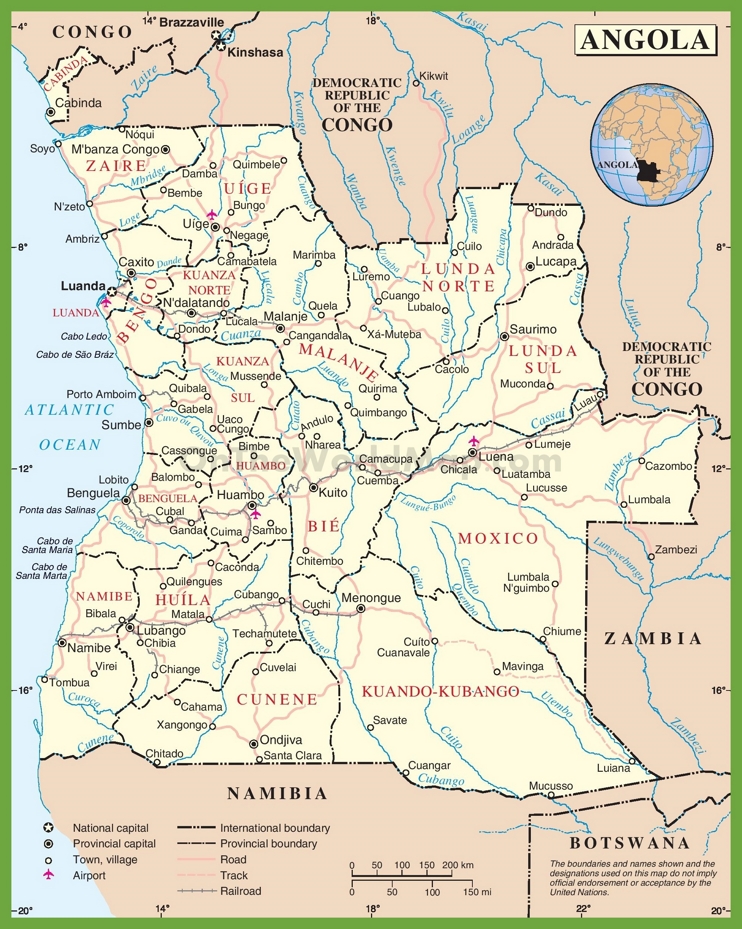

Figure 1.1, 1.2, and 1.3.

ACRONYMS

AFDL Alliance des Forces Démocratiques pour la Libération

ALIR Armée de Libération du Rwanda

CNDD Conseil National de Défense de la Démocratie

DSP Division Spéciale Présidentielle

FAA Forças Armadas Angolanas

FAC Forces Armées Congolaises

FALA Forças Armadas de Libertaçao de Angola

FAPLA Forças Armadas Populares de Libertaçao de Angola

FAR Forces Armées Rwandaises

FAZ Forces Armées Zairoises

FDD Forces de Défense de la Démocratie

FLEC Frente de Libertaçao do Enclave de Cabinda

FNLA Frente Nacional de Libertaçao de Angola

FRD Forces de Résistance de la Démocratie

Frodebu Front pour la Démocratie au Burundi

ICTR International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda

Mai Mai Congolese Ethnic Militias

MLC Mouvement de Libération du Congo

MNF Multinational Intervention Force

MPLA Movimento Popular de Libertaçao de Angola

PRP Parti de la Révolution Populaire

RPA Rwandan Patriotic Army

RPF Rwandan Patriotic Front

RCD Rassemblement Congolais pour la Démocratie

RDR Rassemblement Démocratique pour le Retour

UNITA Uniao Nacional para a Independencia Total de Angola

Note: I will use the name “the Congo” throughout the entire paper despite the official name of the country varying. What is now known as the Republic of the Congo will be referred to as Congo-Brazzaville throughout.

1960-1971 The Republic of the Congo

1971-1997 Zaire

1997-today The Democratic Republic of the Congo.

Crisis in Africa

“We practice the politics of allowing people to solve their own problems”

- Chinese Official to a British Journalist in 1995[1]

The above quote was supplied by a Chinese official commenting on the sale of Chinese produced arms to ex-Forces Armées Rwandaises (FAR), former members of the Rwandan Army under the Hutu regime, and interahamwe, a Hutu militia that participated in the Rwandan genocide. This was also the functional position of the self-styled “international community” towards most of Africa following the end of the Cold War. Certainly, there were denouncements and even token “interventions” in the form of United Nations missions, but the only serious actions taken were by individual nations hoping to preserve their own endangered interests. The international community repeatedly ignored overwhelming evidence of crimes against humanity, or simply abdicated a responsibility to intervene on the grounds of strategic irrelevance. Ruling governments desperately struggled against instability, state failure and armed rebellions. In an environment where “problems” were the difference between state survival and collapse, ruling governments soon learned that they would need to solve their own problems, and they resolved to do so by any means necessary. For many of the nations that bordered the Congo in the mid-1990s a key step to resolving their problems was the neutralization of the Congo as a resource depot and staging ground for armed rebel groups.

The first and second Congo Wars saw the direct or indirect involvement of a huge number of African states. Angola, Burundi, Congo-Brazzaville, Chad, the Central African Republic, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Libya, Namibia, Rwanda, Sudan, Uganda, Zambia and Zimbabwe were all involved. However, only a few of these nations made a significant military or logistical investment in either conflict.

The first 1996 attempt to oust Mobutu enjoyed almost universal support, or at least tolerance, from African States. The only non-Congolese forces that fought for Mobutu were rebel groups, the Angolan Uniao Nacional para a Independencia Total de Angola (UNITA)and Burundian Forces de Défense de la Démocratie (FDD), and mercenaries, mostly of the drunk and Serb variety. However, the 1998 attempt to oust Kabila saw a split in this coalition. The Angolans, joined by several other African states, provided military resistance to the advancing Rwandan and Ugandan forces. What caused this rapid realignment? What caused the Rwandans and Ugandans to abandon the man they had just elevated, Kabila?

Due to the practical limitations of this paper, the analysis will be limited to two of the most important nations involved in the Congo Wars: Rwanda and Angola. These nations fought together in the First Congo War but in the Second, Rwanda attempted to overthrow Kabila while Angola supported him. This split can be traced to a variety of factors. Explanations range from economic incentive to dispassionate strategic calculation to overconfidence. The most convincing explanation for the split is Rwandan political miscalculation that provoked the Angolan response. Rwanda and its allies made overtures to UNITA, provoking the Angolan response.

The paper will begin with a brief history of the Congo, with particular attention to the decline under Mobutu. Then the events of the First Congo War will be detailed. Next the circumstances of Angola and Rwanda in the lead up to the Congo Wars will be examined, and their reasons for entry into the first Congo War will be explained. Finally, the paper will examine major explanations for Angolan and Rwandan involvement in the Second Congo War, and the reasons for their eventually split.

The Early History of the Congo

Leopold seeks a “slice of this magnificent African Cake”[2]

Although this paper seeks to examine the actions of Angola and Rwanda, the battlefield, the Congo, must be examined. The story of the Congo is one of brutal colonialism and destructive authoritarianism. The end result was a state that had almost ceased to exist by the time the First Congo War started.

King Leopold, of Belgium, began his efforts to obtain the Congo in 1876. He launched a significant financial venture to do so in 1878 and then an expedition in 1879, under the guidance of Henry Morton Stanley. Finally, after gaining the support of the United States in 1884, he obtained the assent of the European powers at the Berlin Conference in 1885. Under Leopold the Congo Free State was ruthlessly exploited for economic gain rather than governed in a traditional sense. The Congolese population was mobilized as a massive slave labor force, often through brutal violence. In 1908, after a successful human rights campaign against Leopold, the Congo became a colony of the Belgian state. However, the Congolese people continued to be ruthlessly exploited. This period was marked by the use of chiefs to control the local population. [3]

Eventually, a significant democracy and independence movement arose in the Congo and in 1960 the Congo gained its independence. Willame characterizes the decolonization process in the Congo as “atypical”, in that “no façade could be built.” The administration that had been created collapsed: 10,000 Belgian civil servants left, and the military, the Force Publique, was in “full scale rebellion.”[4]

Political decay was also evident in the wake of independence. The coalition that had achieved independence was “deeply rent by internal contradictions”. The fragility of the independence movement was exposed after the election of Patrice Lumumba. A military revolt and the attempted secessions of Katanga and South Kasai nearly tore the newly independent state apart. In addition, Lumumba was seen as too radical by Western powers, a concern only heightened by his overtures towards the Soviet Union. In 1961 Lumumba was removed from power and then assassinated by Belgium with the complicity of the United States.[5]

A major Lumumbuist revolt began in 1964, but was defeated— with the help of the United States— in 1965. This rebellion led to the rise of Mobutu Sese Seko, who ruled until the conclusion of the First Congo War in May 1997.[6]

Mobutu’s Regime

“Democracy is not for Africa. There was only one African chief and here in Zaire we must make unity.”

Mobutu Sese Seko[7]

Mobutu overtook a struggling nation. Despite early success, Mobutu proved an incapable and deeply corrupt leader. Even with support from Western powers during the Cold War, the state decayed significantly under Mobutu, culminating in widespread state failure.

Mobutu’s regime was a “pure product of the Cold War.”[8] He was backed by Western powers who saw him as a strongman that could control the popular sentiments that had led to the rise of radicals like Lumumba. Mobutu inherited an already weak state. During the 1964-5 Rebellion, several areas of the country—most notably in the east—had resisted government pressure and were conquered only through the utilization of foreign mercenaries. The economy had declined significantly since independence: it would take until 1967 to fully recover. Furthermore, transportation infrastructure had broken down and fighting had displaced thousands of people.[9]

Mobutu, aided by rising copper prices following the outbreak of the Vietnam War, did oversee a period of economic growth from 1968-74. The Congo was extremely dependent on copper exports, and War caused a massive increase in copper prices. During this period, certain gains were made. Mobutu nationalized Union Minière, a Belgian mining company that dominated copper extraction in the Congo.[10] Impressive infrastructure projects, like the Inga Dam, were completed.[11]However, only a few sectors benefitted from this boom. Agriculture, transport and healthcare received a “disproportionately small” amount of investment.[12]

In addition to economic incompetence, corruption dominated the state. Mobutu practiced an extreme form of clientelism: he used the treasury to build a network of loyal political supporters. Mobutu became one of history’s most prolific kleptocrats: he funneled billions of dollars into foreign bank accounts. “Extravagant” and “unproductive” projects were repeatedly undertaken. The most extreme example of this behavior was his 1973 seizure of foreign owned businesses, Zaïrianization (Mobutu officially renamed the country Zaire in 1971). This process was marketed as a strike against foreign interference in the Congo, but in reality, this was simply a way for Mobutu to expand his political power. These businesses were taken from competent hands and used as a way to curry favor and reward allies. Many of the businesses began to fail and Mobutu was forced to enact a policy of mass nationalization for the failing businesses.[13]

The end of the Vietnam War caused a massive drop in copper prices. The fleeting period of growth soon gave way to an extended financial crisis that plagued the Congo until the end of Mobutu’s rule. Zaïrianization and continued reckless spending did further damage. It was not just that the economy experienced a downturn, it was that in many ways the government stopped functioning. Revenues fell, the state withdrew and corruption spread through all major institutions.

The military became functionally useless, as displayed by its dismal performance in both Shaba I and II, domestic uprisings aided by the Angolans. In Shaba II, foreign troops were provided covertly by several Western nations.[14] In 1977 “the deficit had risen to 32 percent of the total budget.” 60 percent annual inflation “became normal.”[15] This economic crisis meant that Mobutu had an increasingly difficult time securing loans through private banks. He became entirely reliant on Paris Club, IMF and later World Bank support. Debt had risen to five billion dollars by 1981 and then a staggering ten billion dollars by 1990. Mobutu was completely incapable of paying these debts: his Paris Club debts were rescheduled 10 times during his rule.[16] All the while, Mobutu practiced “systematic embezzlement”, syphoning away money for lavish personal purchases. However, Mobutu’s behavior was ignored by many of his Western backers. Cold War politics dictated that Mobutu was to be protected as an ally against Communism. All the while, infrastructure continued to be ignored by the government.[17]

As the state drifted towards failure, mass theft became prominent on all levels of society. Unpaid police officers and soldiers used force to create income streams.[18] The informal market became incredibly “dynamic and vibrant.”[19] The lack of transport infrastructure meant that many areas of the country found it easier to trade in neighboring foreign markets rather than internal markets.[20] Goods were smuggled out of the country’s porous borders en masse: 30-60% of coffee, 70% of diamonds, 90% of ivory, and large amounts of goods from a variety of sectors.

The state was breaking down and it often failed to supply many basic services. Thousands of people died every year from preventable diseases due the lack of health infrastructure and education was constantly underfunded. Regulation was limited to the sale of licenses.[21] This was driven by a variety of economic factors. Lack of demographic information and rampant corruption made tax revenues unreliable and insufficient. Already in critical condition, the wheezing state was dealt a further blow in 1990 when the Cold War ended. The world market was flooded with cheap arms, causing copper prices to fall.[22]

The fall of communism as a global force meant that Mobutu’s domain had lost any semblance of strategic value. Mobutu’s clientelism was dependent on having adequate resources to distribute, but his value as an ally diminished when the Cold War ended, and thus his ability to exercise political power domestically diminished.[23] Foreign aid was soon tied to increased democratization and other political reforms that would require Mobutu to engage in significant power sharing. In 1990 Mobutu allowed opposition political parties and appeared to acquiesce to demands for democratization. However, the old dinosaur still had a few tricks up his sleeves: he was able to skillfully avoid these challenges for many years. The Sovereign National Conference was organized in1992, but was slow to resolve any major political questions.[24] A democratically elected government was eventually created under Étienne Tshisekedi, but infighting and Mobutu’s scheming, including the creation of a shadow government, undermined its authority.[25]

All the while, the state continued to decay. In 1991 Mobutu, unable to pay his soldiers, told them to “live off the land”, which sparked massive looting in Kinshasa known as “les pillages.” This quickly spread to other cities.[26] The looting destroyed as much as 90% of the “modern economy” in Kinshasa before targeting grey and black markets. Mobutu’s regime survived this disturbance despite failing to control it: the looters had no mission and no leader. The economic situation worsened severely: average annual inflation was 3,616% from 1990-5, peaking at 9,769% in 1994.[27] Mobutu introduced the 5 million note, called the Zaïre, in 1992. The new bill was not accepted by shopkeepers but was used to pay soldiers. Soldiers paid with these bills mutinied and looted Kinshasa in 1993.[28] Mobutu maintained power but the country was falling apart. There was violent unrest in the East, particularly in North Kivu. The Congo had extremely porous borders in the 1980s and 1990s that allowed unfettered entry for any actor with the money to bribe border guards. Weapons could easily be brought into the country.[29] And all these problems were made worse by the geographical realities of the Congo:

“The geography of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, (the former Zaire), makes it unusually hard for government forces to control because the population lives around the fringes of a huge area, with the three main cities in the extreme west, extreme south-east and extreme north.”[30]

The existence of “multiple centers of accumulation” made the country difficult to control for the weakening Mobutu. Furthermore, the country’s “archipelago of resources” meant that the government needed to project control over a large portion of the country to maintain economic dominance. The “true” political system operated “outside the conventions of formal state sovereignty.”[31] The Congo had ceased to function as a normal state and was now essentially a “warlord state”[32]: it had “no money, no foreign aid, and no functional army”[33]. Reyntjens provides an even more dystopian assessment: “The Zairean State had virtually disappeared”.[34]

The scope of state failure is truly staggering. Borders were porous to the point of nonexistence. Herman J. Cohen, former U.S. assistant secretary of state for Africa, characterized the state as little more than the municipal government of Kinshasa: “there is no real government authority outside the capital city.”[35] Crucially, the Congo was not like the Sudan or Somalia: much of the country was under no control by any group, and was simply wild. Mobutu was often unable to stop violence, but this violence rarely had the intent of toppling his regime, so he continued to limp along. The lack of organized violent opposition meant that Mobutu was only challenged in minor ways, and his usefulness as a Cold War ally and access to the treasury allowed him to fend these challenges off. However, Mobutu could only outmaneuver his enemies for so long.

The Eastern Congo Buckles Under the Weight of the Rwandan Genocide

“I wholeheartedly hope that these attacks take place! Let them try! I do not hide it. Let them try!”

Paul Kagame[36]

As the Congo was experiencing a democratization crisis Rwanda was headed towards genocide. The 1990-4 War with the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF) had stoked already present Hutu power politics. When Rwandan President Habyarimana’s plane was shot down, the country descended into bedlam. Interahamwe, organized Hutu militias, and other civilians armed by the Hutu government committed genocide against the minority Tutsis. The RPF launched an invasion, stopping the genocide and taking power.[37] Following the 1994 Rwandan genocide 1.5 million Hutu refugees flowed into the Eastern Congo.[38] The Kivus, two provinces in the Eastern Congo that border Rwanda, were already facing interethnic tensions. Fighting in 1993 in North Kivu had required the intervention of the Division Spéciale Présidentielle (DSP), elite Congolese troops loyal to Mobutu. These new Hutu refugees further destabilized the situation in a densely packed area. Rwanda, Burundi and the Kivus had “a combined population of 20 million for an area of some 180,000 sq. km.” or 110 per sq. km. This was the “the highest regional density of the continent.”[39]

“HCR stands for Hauts Criminels Rassasiés”[40]

Rwanda is much smaller than the Congo: only 26,338 sq. km compared to 2,345,000 sq. km. Like the Kivus it is very densely populated. Rwanda is mineral poor compared to the Congo. Only small deposits of coltan and tin supplement an agricultural sector that frequently failed to meet the needs of the country.[41] Ethnic balance.

The RPF had inherited a country “that had been profoundly destroyed both in human and material terms.” Infrastructure had been decimated and “banks plundered.”[42] In some ways foreign aid was not forthcoming. Rwanda’s would be Western backers insisted on a “broadening of the political base.” However, this request seems strange at first glance: the RPF had included a large number of Hutu ministers in the government. While it is true that the RPF pursued a visible policy of including Hutu in the highest reaches of government, at all other levels of state they reserved a great deal of power and influence for Tutsis.[43] Prunier contends that the subtext of this request was a demand that Rwanda invite members of the former government into the new coalition: this was a prospect not palatable to the RPF leadership.[44] Others assert that foreign aid was given fairly liberally, and that this aid emboldened the RPF: they believed that they were being given a “blank cheque.” In a January 1995 roundtable Rwanda was given $600 million in foreign aid with no strings attached.[45] However, it is important to note that only $94.5 million had been released to the RPF by June 1995, minus 26 million for outstanding debts.[46]

Simultaneously, the MDR, “the main RPF coalition partner” and a party that could rely on a “good share” of the Hutu vote, attempted to assert itself by making political demands of the RPF. These demands included severe accusations of RPF misconduct. [47]

The RPF also had to address the problem of justice. Using an unreliable system of denunciation, the RPF was jailing supposed perpetrators of the genocide in enormous numbers. By early 1995, 100-150 people were arrested every day. 44,000 were jailed by June 1995, 80,000 by August 1996 and 100,000 by 1997. The Rwandan justice system, itself heavily damaged by the genocide, was not capable of handling prisoners in these numbers: only 36 judges and 14 prosecutors remained in the country. Most arrested never saw trial.[48]

Jails quickly became overcrowded leading to the creation of make-shift prisons; only 16 out of the 183 detention centers were actual jails. This overcrowding also created deadly conditions for prisoners: over 1000 deaths were witnessed by the Red Cross at a prison in Gitarama in a nine-month period.[49] The RPF was certainly not innocent in this situation: they often resorted to extra-judicial killings or simple massacres. The RPF pursued a policy of arbitrary arrests and political oppression, building a substantial “security machine” to perpetuate their rule.[50]

RPF misconduct notwithstanding, the mad dash for justice could not be contained to Rwanda. After the Rwandan genocide 1.5 million Hutu refugees flowed into the Eastern Congo.[51] Other estimates place the number of refugees in the immediate area around Goma, very near the Rwandan border, to be 850,000. 650,000 fled to camps near Uvira and Bukavu. The Rwandan government had obvious reasons to desire repatriation: if the Hutu refugees did not return then they could not be won over and as the RPF well understood having a large portion of the Rwandan population outside Rwanda’s borders was a “destabilizing factor.”[52] However, there were other motivations for repatriation, or at least a reorganization of the camps.

Among the refugees were the remnants of the former government, ex-FAR, and the interahamwe militias. Deibert estimates that the army reconfigured into two divisions of 10,240 and 7,680 men each, with an additional 4,000 men in auxiliary units. Prunier asserts that 30,000 to 40,000 ex-FAR soldiers fled into the Congo with the refugees. Either way, these soldiers were arranged in two divisions, one in North Kivu and one in South Kivu. Politically, they organized under the banner of a newly created organization, the Rassemblement Démocratique pour le Retour (RDR). Porous borders and a sympathetic Mobutu allowed the ex-FAR to retain their “officer corps,” “heavy and light weapons” and “transport echelon.” An Ex-FAR high command was created in the Mugunga camp in North Kivu. Although some fled to other nations, the Congo was the primary destination of the military men and politicians of the former regime.[53]

Former government officials, ex-FAR and interahamwe elements quickly gained political power within the camps. They were able to gain control of the food supply and other important goods using by using force and other methods to influence supposedly democratic elections. These elements were able to prevent refugees from leaving the camps as they began the process of rearming. They accomplished this through control of resources, intimidation and by spreading propaganda.[54]

Almost immediately the military elements in these camps began organizing strikes across the border. On October 31, 1994, ex-FAR forces killed 36 people near Gisenyi. Although the immediate strikes on the Rwandan civilian population were not threatening to the rule of the RPF, the ex-government forces in the camp were “rearming, practically in full view of the international community.” Organized training, with the intent of launching of a full scale invasion of Rwanda, began shortly after the camps were established.[55]

However, the mere intent to rearm would have perhaps been insufficient to constitute a serious security risk if not for two important factors: monetary resources and support from the government. Deibert estimates that the genocidaires, participants in the Rwandan genocide, brought $30-$40 million dollars across the border.[56] Prunier states that that genocidaires brought all the financial resources of the former government, and could draw on money stashed in foreign bank accounts by individual politicians.[57] This allowed the genocidaires to buy a large amount of weapons from former Warsaw pact countries like Bulgaria and Albania.[58]

Mobutu also offered considerable support to the genocidaires despite the crumbling state of his own domain. Crucially, he gave them free reign to use the Congo as a staging ground for operations in Rwanda.[59] Despite promises he made no attempts to police the camps, allowing the genocidaires total control. On a 1994 trip to China Mobutu brought high ranking members of the former government and facilitated a $5 million arms deal with Chinese manufacturers. In a more abstract sense Mobutu also gave the genocidaires a certain amount of importance: they could “pretend” they were still a “major actor.”[60]

However, an actor remained that could solve the problem arising in the camps: the United Nations and the international community as a whole. The international community’s reaction to the refugee crisis was inadequate to say the least. This produced two large problems that contributed to Rwandan intervention in the Congo.[61]

The first was that while the international community was dragging their collective feet in giving aid to Rwanda, they were pouring a massive amount of money into the refugee camps. From 1994-6 $2.03 billion was given to refugees while only $897 million was allocated to Rwanda. This was particularly egregious in the eyes of the RPF given that there were only 2 million refugees compared to 5 million Rwandans.[62]

Secondly, and more importantly for Rwandan security, the international community made no real attempts to demilitarize the camps. The United Nations did attempt to police the camp using a force of 1500 ex-DSP soldiers, called Mrs. Ogata’s troops. They were named after the UN high commissioner for refugees, Sadako Ogata, but not under her control. However, while these troops did introduce a modicum of order into the camps, they had no mandate to limit the activity of the ex-FAR forces. The UN made no attempts to arrest the influence of genocidaires on the camps in a political and military sense. They also made no attempts to infringe the movement of purchased arms into the camps.[63] In addition, while France continued to attempt to stymie the RPF, mostly out of frustration at having lost a friendly government in Rwanda, the United States aligned very closely with the RPF, partially because of guilt and partially because of fascination. This support became almost “uncritical” in the eyes of Prunier, emboldening the RPF.[64] As a result of the behavior of the international community Rwanda believed that they alone could address the problems in the Congo. Furthermore, beyond United States support Rwanda also benefitted from generally low expectations applied to all African states.[65]

Winter presents a slightly different view than Prunier. Winter states that the Rwandan Patriotic Army (RPA), the Rwandan military after the RPF assumed power, was confident in its ability to repel an ex-FAR invasion, and was not motivated by this concern. Instead the RPF was concerned that genocidaires would use the return of the innocent masses to visit violence on the Rwandan civilian population. The Rwandans feared that this would necessitate an RPA counterinsurgency campaign, which could be politically damaging. If the RPF did believe this, then they were badly underestimating the potential threat of the ex-FAR. Furthermore, Winter mentions Rwanda’s economic recovery, but the RPF remained economically limited and the assets of the former government were formidable. [66] Either way, Rwanda still had an interest in decoupling the genocidaires from innocent Rwandan Hutu refugees, an interest that could not be accomplished without the toppling of the Mobutu regime.

In addition to security, two factors, one psychological and one symbolic, influenced the decision making of the RPF. The first problem was that of justice. The very nature of the genocide, neighbors killing neighbors, coupled with the insufficient justice system and the flight of major genocidaires into a country actively protecting them created a complete lack of justice. The international community attempted to provide this “biblical justice” with the creation of the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR), an organization that attempted to prosecute the perpetrators of the Rwandan genocide. However, the sentences of the ICTR were seen as too light by the Rwandans. This led many Rwandan Tutsis to see the Hutu population as collectively guilty: because the Hutu genocidaires had not been “sacrificially executed, all Hutu were now regarded as potential killers.”[67]

Second, the psychology of the RPF must be understood. The “hard core” of the RPF at the time of the genocide were “young boys” in Uganda in the early 1980s. They matured mired in conflict. First they fought in the 1978-9 War with Tanzania. Then they suffered during the 1982 anti-Rwandan pogroms and then joined Yoweri Museveni’s revolutionary movement. They aided Museveni in his overthrow of Milton Obote, the leader of Uganda at the time, and then fought against the rebel forces of Alice Lakwena, who was believed to be a prophet. Then they began an extended conflict with the Rwandan government that ended with the RPF seizing power in the wake of the 1994 genocide. They were witnesses of, subject to, and perpetrators of massacres throughout this period.

The RPF developed a “peculiar” culture during their early years in Uganda: “they knew only the gun, and the gun had worked well for them in the past.” They were self-confident but did not seek complex solutions to political problems, using only force. This explains the systematic killings that the RPF perpetrated during and after the genocide. Prunier argues that they were specifically designed to pulverize the population into submission.[68]

The application of this logic to the refugee problem can be seen in the forceful disbandment of camps in Kibeho, in the Safe Humanitarian Zone that had been created by the French as part of Operation Turquoise. These camps, located in Northern Rwanda, contained 350,000 internally displaced persons (IDP). The Rwandans announced that the camps were to be dissolved and refugees repatriated and that they would use force if necessary. This promise was fulfilled on April 22, 1995: 300 people were killed and the others were forcefully repatriated under brutal conditions. Some twenty thousand people “vanished after the massacre.”[69]

The RPF also calculated correctly that the International Community had little support for intervention in the Congo. The United States’ increasingly enthusiastic backing of the RPF gave them a valuable ally in this regard. The United States did in fact provide quite a lot of “foot-dragging” when an MNF, a multinational intervention force, was proposed to protect Hutu refugees in the Eastern Congo.[70]

Finally, Rwanda’s regional concerns must be evaluated, and the most pressing of these was the looming democratization of Burundi. When the First Congo War was initiated Burundi was embroiled in an extended civil war between Hutu and Tutsi political and military forces. Burundi is 80 percent Hutu, and 19 percent Tutsi, demographically similar to Rwanda. However, the country has historically been politically dominated by Tutsis, demographically like Rwanda. The two ethnic groups have found themselves in near constant conflict since Burundi gained independence in 1961.

In 1992 the international community pressured Burundi into democratization. Elections were held in 1993. Predictably, FRODEBU, a Hutu political party, won the elections convincingly.[71] Tutsi military and political elites reacted by a staging a coup in 1993. Hutu President Ndadaye was assassinated along with other prominent FRODEBU leaders. However, the coup failed to place Burundi under immediate Tutsi control. Thus began the “creeping coup.” Tutsi elites attempted to delegitimize the election results by implicating FRODEBU in a planned genocide. They embroiled the nation in a constitutional crisis, and used Tutsi militias to intimidate FRODEBU supporters and politicians.

This gave way to street violence between Hutus and Tutsis. Both groups became increasingly radicalized. Extremist Tutsi militias sprung up and the Conseil National de Défense de la Démocratie-Forces de Défense de la Démocratie (CNDD-FDD) formed as an offshoot of FRODEBU. Tutsi politicians demanded greater and greater concessions as the country experienced more ethnic violence. A “genocide by attrition” unfolded as the country descended into an endless series of retaliatory massacres.

A successful 1996 Tutsi military coup extinguished hope of compromise, and the country descended into open war.[72] Burundian Refugees flowed into the Eastern Congo. Among them were FDD rebels that the Burundian Government sought to pacify. The CNDD-FDD was supported by Mobutu and allowed to use the Uvira region as a staging ground. The Congo became an important “rear base” for the rebels fighting the Burundian government.[73] However, the Burundian government was being pressured by the international community to end the war and hold elections.

The RPF saw the Tutsi regime in Burundi as an important ally, and feared that if the United Nations was able to force Burundi into negotiations then a Hutu regime could follow. This regime would be hostile to the interests of Rwanda and friendly with genocidaire forces currently in the Congo. The RPF directly intervened in Burundi in 1995 to participate in anti-guerilla activities. The invasion of the Congo was partially a response to the impending crises and a desire to eliminate the rebel factions as legitimate opponents to the regime.[74]

Rwanda was motivated by several factors. First, the RPF was under threat from the genocidaires that had fled into the Congo. They were actively attempting to rearm, and had the political and financial resources to do so. Second, the RPF was driven by the psychological need for justice, which was complicated by a lack of legal infrastructure and a huge number of potential perpetrators. Third, the RPF possessed a peculiar psychology that led them to prefer force as a solution to a broad array of problems. Finally, the deteriorating situation in Burundi, an important all, precipitated the need for intervention in the Congo.

The Angolan Civil War Spills into the Congo

“We are not going to give it up”

Jonas Savimbi referring to UNITA controlled diamond fields and mines.[75]

In sharp contrast to Rwanda, Angola is a large country—1,246,000 sq. km—and fighting was not clustered in one region of the country. Furthermore, Angola is much richer than Rwanda, and possesses significant natural resources, primarily oil and diamonds. The oil industry made Angola wealthy as a nation but the wealth remained extremely concentrated: the oil industry only employed 10,000 Angolans but was the primary target of investment. This resource concentration consistently exacerbated inequality.[76] Angola was embroiled in a contentious civil war for more than 25 years. The Movimento Popular de Libertaçao de Angola (MPLA), the ruling party of Angola since 1975, fought against a series of challengers; the Frente Nacional de Libertaçao de Angola (FNLA), an anti-Portuguese and later anti-MPLA rebel group founded in 1961, was initially the dominant opponent, but it was supplanted by UNITA, an anti-MPLA group formed by Jonas Savimbi. All the while the Frente de Libertaçao do Enclave de Cabinda (FLEC), a minor anti-MPLA group and ally of UNITA remained a minor player throughout the War.

The MPLA was the party of the coastal mestiço and assimilado elite that numbered somewhere around 500,000 in a country of 12 million. UNITA was hardly a pure expression of the people’s will, however, they were favored by the matumbos and the pretos: the “deeply” African masses that inhabited the interior of the country.[77] The Angolan Civil War was also partially fought on ethnic lines: the MPLA was popular among the Umbundu people of Luanda’s hinterlands. The now-defunct FNLA was a primarily Kongo movement with northern base of support and FLEC was of Cabindan origins. UNITA formed after it splintered from the FNLA and was founded by Jonas Savimbi, of Ovimbundu origins.[78] However, as the war progressed ethnic identity became less important that economic status. For the disaffected people Savimbi was their best advocate, despite his more objectionable characteristics.[79]

The Angolan Civil War was initially fought on Cold War terms. On the one side there was the ruling government, the Marxist MPLA, supported by Cuba and the Soviet Union. On the other there was the FNLA, supported initially by the soviets and then by the United States and Mobutu, and UNITA, supported initially by South Africa and then later by the United States and Mobutu as well.[80] However, each of these groups was ideologically flexible: their use of socialism and other ideologies was mainly a response to potential political rewards. The process of picking sides was done “arbitrarily” by the CIA.[81] While UNITA occupied the ambiguous ideological space of pro-western-ism, the MPLA became more doctrinal at the urging of its allies, before lurching back to pragmatism with the ascension of Dos Santos in 1979.[82]

In January 1975, UNITA, the MPLA and the FNLA signed the Alvor Agreement, supposedly ending the conflict and creating a tripartite government. However, the MPLA quickly reneged on the treaty and attempted to expel UNITA and the FNLA. On November 11, 1975, the MPLA declared the creation of the Popular Republic of Angola and received the recognition of the Eastern Bloc countries, but not the recognition of the United States. This sparked a new phase of the civil war, soon “internationalized” by direct South African intervention.[83] In January 1976 the FNLA launched an assault against the MPLA, but it was quickly thwarted by Russian artillery. Mobutu then deployed his own military, but his forces failed miserably. The FNLA essentially ceased to exist and the United States was forced to back UNITA and its leader Jonas Savimbi.[84]

Throughout the 1980s and early 1990s, Mobutu allowed UNITA to use the Congo as a “rear base” for its actions in Angola. In collaboration with the CIA Mobutu used the Kamina military base in Katanga to supply UNITA.[85] In the 1990s Savimbi created a “secret army” of 15,000 soldiers in the Congo, with Mobutu actively aiding their supply efforts.[86] Mobutu also facilitated diamond for arms trades, and sold fuel to UNITA. The antagonism between Kinshasa and Luanda was mutual. The MPLA had previously attempted to overthrow Mobutu using the Katangan Tigers in the Shaba I and II, attempted uprisings against Mobutu, in 1977 and 1978 respectively. The Angolans provided logistical support for the Tigers during both wars.[87]

A 1988 agreement guaranteed free and fair elections in Namibia with the participation of South West African Peoples Organization (SWAPO), a Namibian nationalist party that advocated independence, in exchange for Cuban withdrawal from Angola. However, this did nothing to halt the violence inside Angola, other than halting South African aid to UNITA. The war had been devastating for Angola: one million IDPs and 760,000 externally located refugees, devastated agricultural production, a staggering debt and a budget that was 60% military spending.[88]

On May 31, 1991 Savimbi and Eduardo dos Santos, the leader of the MPLA, signed a peace agreement, agreeing to hold “free and fair” elections in a year and integrateForças Armadas Populares de Libertaçao de Angola (FAPLA), the MPLA military forces, and Forças Armadas de Libertaçao de Angola (FALA), the UNITA military forces, into a unified force, the Forces de Défense de la Démocratie (FAA). In the1992 elections Dos Santos prevailed, but Savimbi alleged that the election results were not valid. In Luanda, just 32 days after the elections violence erupted between UNITA and the MPLA, leading to the infamous “the All Saints Day massacre” slaughter of UNITA forces and the resumption of the civil war. The international community, now thoroughly “anti-UNITA” imposed a “global embargo” on UNITA through the UN, forcing UNITA to sign the Lusaka Peace Protocols in 1994. However, both sides immediately began “acting in bad faith.”[89]

Both the MPLA and UNITA practiced what Reno calls “warlord capitalism.” In the absence of a strong state apparatus both actors exploited economic resources to compensate for other deficiencies.[90] Therefore, the MPLA and UNITA frequently clashed over resources and consistently attempted to limit the other’s access to resources.

The MPLA oversaw a booming oil industry that accounted for a huge portion of the economy by the 1990s, climbing to 89% of GDP by 1997.[91] State revenue from oil production was $1.8-3 billion from 1990-9.[92] Similarly, UNITA was extremely dependent on a massive .

diamond business. UNITA also profited from gold, coffee and other products.[93] Illegal miners exploited secret mines, mostly in the Luanda Notre Province. The rough stones were then sold on the black market, sometimes with the assistance of FAPLA, and later FAA, officers. By 1993 UNITA controlled two-thirds of Angola’s diamond production and was earning hundreds of millions of dollars every year from sales. From1992-1996 UNITA made $600 million, $600 million, $600 million, $320 million, and $720 million.

Diamonds were particularly valuable because they could be easily exchanged directly for arms. This meant that UNITA was able to circumvent the embargos enacted by the UN. UNITA bought weapons from Bulgaria and very likely other Eastern Bloc countries with a variety of African nations, most notably the Congo, providing end-user certificates.[94] The Angolans, with a booming oil industry, were able to purchase “over $1 billion” in Eastern Bloc weapons in 1986-7. After the 1991 peace agreement the MPLA completed a $25-million-dollar purchase of military hardware from Spain. The MPLA also purchased a large amount of military hardware from Russia in 1993.[95]

The imminent resumption of conflict with UNITA was the most pressing reason for Angola’s entry into the First Congo War.[96] Angola was initially neutral in the first Congo War, and was open to an agreement with Mobutu. More than anything, Luanda wanted to harm the efforts of UNITA. In December 1996 Dos Santos contemplated an agreement with Mobutu that would stop UNITA arms buying and diamond selling activities and dismantle UNITA bases in the Congo. In exchange Angola would prevent the Katangan Tigers from crossing into the Congo. However, Dos Santos became wary of Mobutu’s ability to enforce his part of the bargain when he learned that Mobutu’s close associates were “fraudulently” selling arms to UNITA. Furthermore, UNITA had significant military assets in the Congo: the “secret army” of 15,000 UNITA troops represented a significant danger.[97] It is possible that Luanda did not think Mobutu capable of actually decoupling himself from UNITA given his weakness.

The First Congo War

“We are prepared”

Paul Kagame[98]

The stage was set for an invasion, but Kigali needed a casus belli if it was to launch a military operation into Congo. This came in the form of the Banyamulenge rebellion in South Kivu. The region was already unstable due to the influx of Hutu refugees and certainly the Banyamulenge had genuine grievances. The Banyamulenge were under significant threat as “anti-foreigner” sentiment was on the rise in the Kivus. However, the rebellion was not entirely natural. Kigali trained 2000 Congolese Tutsis, who then recruited 2000 additional men. These men launched the Banyamulenge rebellion in October 1996. Rwanda continued sending armed infiltrators across the Burundian border into South Kivu, and started attacking targets from inside Rwandan or Burundian borders. Soon RPA troops were operating in the Congo.[99]

RPA and Banyamulenge groups started making significant advances in South Kivu: Uvira fell on October 28 and Bukavu on October 30. Kigali used this opportunity to attack refugee camps with the goal of destroying military elements and forcing the repatriation of genuine refugees. This was often accomplished by the shelling of camps. RPA fighters began operating in North Kivu as well, even though there was no rebellion. By early November, “Rwandan and Burundian borders were secure.”[100]

Soon the Alliance des Forces Démocratiques pour la Libération (AFDL) was created as a “domestic” front for what was essentially a foreign invasion. This was an amalgamation of several different revolutionary movements in the Congo. Most importantly for the purposes of this paper and the course of history, it included Laurent Kabila and his small time Parti de la Révolution Populaire (PRP).[101] Kabila was soon chosen as the leader of this partially Congolese rebellion.

Kabila was a small time Lumumbuist revolutionary in the early 1960s. He established his own outfit, the PRP. However, the PRP transformed from a minor political group to an economic venture in the mid-1970s. In 1975 the PRP kidnapped four zoologists working with Jane Goodall in Tanzania. Kabila successfully extracted a $500,000 bounty for their release. Then he began a long and prosperous relationship with the Forces Armées Zairoises (FAZ), the Congolese military under Mobutu. FAZ officers participated in the trade of gold and ivory extracted from PRP controlled areas. Kabila’s presence also allowed the military to claim the area was dangerous, thereby justifying extravagant budgets. The PRP never truly abandoned its original revolutionary pretenses: in 1984 and 1985 the PRP unsuccessfully attacked the FAZ. Kabila then retreated permanently to Tanzania. Ultimately, Kabila was chosen by Rwanda and Uganda for two reasons: he had no particular allegiance to Kampala or Kigali, and he was considered “harmless and easy to manipulate” by Tanzanian secret services.[102]

Unlike the Rwandans, the Angolans intervened after the war effort was well under way. In December 1996, they began preparing “several battalions” of the Katangan Tigers, 2,000 to 3,000 troops total, for deployment in February 1997. The FAA provided logistical support for the Tigers but did not intervene directly until April 1997. In the four months before the Tigers entered the war less than one-twentieth of the country had been captured by the AFDL, but within three months of Angolan entry the rest of the country had fallen.[103]

Soon other nations become involved: Ugandan and Burundian troops operated to neutralize rebel forces within the Congo as early as December 1996. Meanwhile, the AFDL, front though it might have been, was gaining massive support. Practically no one, besides the most entrenched Mobutuists, supported the current regime. Banyamulenge militias and foreign troops were joined by Mai Mai (Congolese ethnic militias), fresh recruits and eventually the Katangan tigers. The FAZ crumbled: the poorly paid troops simply deserted and looted before fleeing the rebel advance. Only the DSP and foreign rebel groups like UNITA and the FDD provided serious resistance. The entrance of the Angolans only accelerated the wars forgone conclusion. Mobutu fled and the Congo had a new ruler: Laurent Kabila.[104]

For both Angola and Rwanda, the Congo under Mobutu represented a serious security concern. And desire to limit threats was the primary reason for their involvement. Both regimes faced an active armed opposition with significant resources: both human and material. UNITA and ex-FAR were not just present in the Eastern Congo but were actively being aided by Mobutu. UNITA used the Congo as a staging ground and supply depot. Mobutu and other Congolese actors were involved in diamonds for arms schemes designed to empower UNITA. Ex-FAR elements were offered many of the same benefits: Mobutu actively aided their rearmament and provided them a staging ground to launch attacks on Rwanda. Both Angola and Rwanda were facing immediate crises.

However, the goals of Rwanda and Angola were lofty. For both of these nations invading the Congo and engineering the overthrow of Mobutu could not solve all of the security concerns generated by the Congo. Kabila could not reverse two decades of sharp decline just by ousting Mobutu. Kabila inherited an economy swamped in debt and a state that could barely provide any services. Even if Kabila proved to be a loyal henchman to Angola and Rwanda, he could not be expected to make the Congo’s porous borders solid or rehabilitate the army without significant financial help.

Another Conflagration Approaches

“A Second Rate Remake”[105]

Kabila came into power in May 1997, but it would only be a little more than a year before the Congo was again embroiled in war. Kabila soon adopted a “conspiratorial political style that had been frozen” in the 1960s.[106] Kabila was entirely concerned with maintaining his own power. He endlessly played his various lieutenants against each other. This strategy produced “confusion, sterile infighting and paralysis.”[107] Kabila quickly became repressive, banning all political activity.[108] Kabila came in to power with popular support but he proved an inept tyrant. The state remained very weak, and Kabila oversaw the country “laxly.” More than traditional governing he became extremely concerned with controlling information channels.[109]

Kabila had to address the problem of the remaining Hutu refugees, and the issue of the crimes against humanity committed by “rebel” forces during the war. Kabila greatly damaged his relationship with the international community by refusing to submit to investigations into the killings and disappearances of Hutu refugees. While the conflict ended, violence remained: massacres of Congolese civilians of various ethincities continued after AFDL victory.[110] Kabila was diplomatically unskilled and repeatedly failed to respect protocols. On a state visit to Tanzania Kabila cut the trip short abruptly without providing any real justification. On a visit to Egypt he simply blew-off an appointment with Hosni Mubarak. Kabila repeatedly caused scandal due to a combination of a lack of diplomatic knowledge and false belief that he possessed immense diplomatic skills. His allies were quickly disillusioned: with security concerns unresolved in the East his relationship with Rwanda and Ugandan quickly soured.[111]

Economically the situation was catastrophic. Debt had risen to $12.8 billion by 1996. No revenue and no cash meant that spending on services had essentially stopped. While international actors were theoretically willing to provide aid, these schemes were mostly politically sabotaged by the refugee issue. Others were sabotaged by internal politics: one scheme was also cancelled over concerns that an economic convention would allow political grievances to be heard. Some schemes were simply ill advised: an attempt to incentivize foreign investment by the World Bank failed due to the extreme decay within the country. The kleptocratic tendencies of the Mobutu regime started to appear again. The government became increasingly reliant on foreign welfare just to function.[112]

The East remained unstable: Kabila’s presence could not magically fix the problems of state decay. Kabila devoted little attention to the east, concerned with his own power, like Mobutu, who nicknamed the mayor of Kinshasa. Mai Mai groups quickly sprung up and scattered fighting began with vulnerable civilians being targeted most often. Soon the East descended into a familiar ethnic madness: groups launched attacks into Rwanda targeting Tutsi civilians and the RPA attacked Hutu civilians in the Kivus. Rwandan Ex-FAR and interahamwe elements and Burundian FDD fighters were once again operating out of the Eastern Congo. The 16,000 Congolese troops in the Kivus were of “uncertain loyalties.” Finally, the powder keg was lit. On July 27 Kabila ordered that all Rwandan troops leave the country: five days later the Second Congo War had begun, with Rwandan troops clearly attempting to overthrow the Kabila government.[113]

Prunier refers to the Second War as a “second rate remake” of the first.[114] Like the first, what was ostensibly a Rwandan and Uganda invasion was fronted by a new Congolese rebel group—the Rassemblement Congolais pour la Démocratie (RCD). However, Kabila was significantly more popular than Mobutu had been, leading to shifting alliances. The Katangan Tigers and Mai Mai fought against the Rwandans rather than for them. Initially, Forces Armées Congolaises (FAC) divisions loyal to Kigali mutinied against Kinshasa; first the 10th Brigade on August 2 and then the 12th Brigade on August 3. The rogue FAC forces, with the assistance of Rwandan troops, ran roughshod over the Kivus. They quickly captured Goma, Uvira, and Bukavu. These actions had been arranged entirely by the Rwandans, with the backing of the United States. The usual players, Uganda and Burundi, joined in. Kabila’s FAC proved only marginally more useful than the FAZ.

Kinshasa would have fallen without the intervention of Angola and Zimbabwe against the rebels, which occurred in late August 1998. Eventually, other nations joined in. The Rwandan advance slowed considerably, and completely stalled by early 2000 (will insert map). By this time large armies had been raised on each side: 85,000 for Kabila and 54,000 for the opposition. The rebel movement itself had split into various factions: RCD-Goma backed by Rwanda and Rassemblement Congolais pour la Démocratie- Mouvement de Libération (RCD-ML) and the Mouvement de Libération du Congo (MLC), backed by Uganda. In addition to widespread looting and exploitation, the Second Congo War also saw repeated and extreme human rights violations. It would not conclude formally until 2003.[115] The war was a massive commitment for all involved and a complete disaster for the Congolese people. Why then did it happen? And why did former alliance partners find themselves fighting against each other?

Africa’s World War Starts in Kigali

Rwanda seeks “another Bizimungu”[116]

What had provoked the Second Invasion of the Congo by Rwanda? This invasion is particularly strange given that Kabila had been chosen by the Rwandans and put into power by Rwandan military might. Clearly, the invasion, if successful, would have the effect of toppling the sitting regime, allowing Rwanda to replace Kabila with “another Bizimungu”, or a more compliant puppet. But was this the primary goal of the invasion? What poisoned the relationship between Kigali and Kabila? There are five broad scholarly explanations for Rwanda’s involvement in the Second Congo War: Protection of Congolese democracy and Congolese Tutsi, security, economic gain, RPF psychology and political developments. These explanations are overlapping.

The first explanation, that Rwanda intervened against Kabila as a means to protect the Congolese people, was one of the official explanations given by the RPF. Rwandan involvement was not admitted during the first weeks of the War, but Rwanda “affirmed” the RCD’s reasons for rebelling against Kabila. These justifications included many of the same accusations leveled against Mobutu: Kabila was an anti-democratic kleptocrat that severely mistreated one or more ethnic groups for political gain, in this case Tutsis. These accusations were ostensibly true; however, Longman contends that the RPF’s own authoritarianism renders their supposed defense of Congolese democracy impossible to take at face value.[117] Other authors suggest that the purpose of the invasion was simply to install a more compliant puppet, additionally undermining democracy as a motive.[118]

However, one of the complaints levied at Kabila would have been of legitimate concern to the RPF: Kabila’s move towards Tutsi “genocide” and his general mistreatment of Tutsis would have concerned the Rwandans. Kagame publicly supplied “ethnic solidarity” with the Banyamulenge as a justification for involvement in the Congo.[119] This is a believable motive for two reasons: the RPA had strong connections to the Congolese Tutsi community and the Congolese Tutsis were under legitimate threat from a variety of forces in the Congo.

The RPA’s leadership was mostly Ugandan, but it had recruited a large number of Tutsis from the Congo, especially during the 1990-4 War with Rwanda. Many of these recruits then returned to the Congo during the First Congo War. The First Congo War and the RPA troops left in the Congo after the war further strengthened the bond between Rwandan and Congolese Tutsis.

The Tutsi population in the Congo was under legitimate threat due to the ethnic volatility of the Kivus. In September 1997 an attempt to install non-Tutsi troops in the region sparked ethnic violence, some of which targeted Tutsis. Then, Banyamulenge militias clashed with Mai Mai troops in early 1998. At a national level Kabila began excluding Tutsis from government and FAC leadership positions. He also reportedly made anti-Tutsi statements on Congolese Radio that were followed by sporadic violence against Tutsis.[120]

Longman rejects this as a legitimate motivation on the grounds that Rwanda’s actions were counterproductive and damaging to Congolese Tutsi interests in the long term. Longman contends that Rwanda’s attack only would have increased the “vulnerability” of the Congolese Tutsi. The ideology of genocide portrays the dominant group as under threat, therefore the Rwandan invasion only would increase this threat. This effect had occurred during the RPF invasion of Rwanda in 1994, and would have been familiar to the RPF. While the RPF invasion offered the Tutsi population protection it had long term negative consequences: the RPF presence and their conduct towards civilians during the Second Congo War exacerbated anti-Tutsi sentiments. Therefore, the humanitarian explanation is not convincing.

Longman poses political motivations, and specifically a desire to achieve unity, as explanations for Rwandan involvement. While War in the Congo would likely further fracture the relationship between the RPF and its majority Hutu population small advances could be made.

First, a war in the Congo was an opportunity to unify a divided Tutsi populace. Tutsi survivors did not sweep into power with the RPF, and were marginalized after the RPF ascension. The RPF failure to solve the justice problems detailed earlier, further alienating Tutsis. The RPF was facing a political challenge in the form of widespread support for the return of the monarchy in Rwanda. This was particularly potent because the King was tainted neither by the genocide or allegiance to any specific ethnic group (the King was seen as representative of all Rwandans).

Second, a war in the Congo could serve to unify a divided RPF. The RPF was a multinational organization before it successfully invaded Rwanda in 1994. Anglophone Tutsis from Uganda dominated leadership positions. Francophone Tutsis from Burundi or the Congo were largely excluded. Even outside of government those who returned from Uganda had generally enjoyed greater opportunities. The monarchist movement was therefore attractive to less privileged members of the RPF. Longman asserts that some RPF leaders may have assumed that a Congo war would be popular among returnees from the Congo, along the lines of ethnic solidarity. Prunier also details this motivation, but that will be examined in the economics section.

Finally, the RPF recruited troops for the Congo invasion from overflowing Hutu prison populations. This had the effect of making a small number of Hutus loyal to the RPF, but Longman concedes that this would have been a relatively minor motivation.[121]

Prunier proposes a political explanation for the invasion, specifically the murder of former RPF minister Seth Sendashonga. Sendashonga was the leading opposition moderate in Rwanda, heading the Forces de Résistance de la Démocratie (FRD). After a year in the “political wilderness” Sendashonga was becoming a possible alternative to the RPF when he was murdered in May 1998. Sendashonga could appeal to both Hutu and Tutsi “survivors.” This potential challenge to the RPF regime was cut short with his death, clearing the way for RPF hardliners. When “Commander James”, James Kabarebe, was kicked out of Kinshasa, the hardliners were further emboldened.[122]

Longman also proposes a psychological explanation: the so-called political triumphalism of the RPF. As has already been covered the RPF had been enormously successful, helping to install Museveni in Uganda, taking power in Rwanda and toppling the ruling regime in a country vastly larger and more wealthy than Rwanda in the span of 15 years. Longman argues that the RPF was extremely confident in their military abilities, to the point of viewing themselves as unbeatable. The RPF viewed Kabila as a junior partner even after he seized control of a much larger country, and therefore found Kabila’s noncompliance unacceptable. They interpreted his actions as a “personal betrayal” and failed to recognize the anti-Tutsi sentiments that necessitated Kabila’s rejection of Rwanda. Longman concludes that this “sense of entitlement” partially drove Rwanda to “haphazardly” invade the Congo.[123] This arrogance and lack of political planning can be seen in the Rwandan relationship with UNITA. The importance of impulsivity is echoed by Prunier who notes the extremely quick decision to invade the Congo and the lack of proper planning.[124]

The last major motivation I will examine is economic gain by plunder and occupation. As has previously been stated Rwanda is an overpopulated resource poor country, while the Congo is extremely rich in a variety of natural resources. Longman asserts that Rwanda profited substantially from its 1998 invasion and occupation in the Congo. Wamba dia Wamba, one-time head of the RCD, accused Rwanda of substantially mineral theft. Resources like Diamonds and Gold could easily be smuggled into Rwanda and Uganda and sold on the open market.

Longman cites a report stating that Rwanda’s diamond exports increased from 166 carats in 1998 to 30,500 carats in 2000. Longman links visible prosperity in Rwanda to looting of Congolese mineral wealth, stating that growth extended beyond what natural economic production and economic aid alone could produce. Furthered more there was a construction boon and an increase in commercial flights out of Kigali. Rwanda was extracting an enormous amount of coltan from the Congo $20.5 million a month by 2000.[125] Rwanda supposedly created a “Congo Office” that processed the resources looted form the Congo, and military planes were loaded with goods.[126] It should be noted that looting of the Congo was systematic and not limited to mineral wealth. Livestock, coffee beans and even mundane objects were stolen and transported across the border. Longman is confident that the cost of waging a war in the Congo could be offset by looting of the Congo. Turner also asserts that Rwanda’s looting of the Congo offset to costs of war and occupation.[127]

The plunder of Congo would have benefitted many different actors: RPF, RPA, and individual smugglers.[128] This opened economic opportunities for RPA officers. Prunier contends that this potential opportunity was a way to relieve tension between the “new akazu”, a circle of RPF leaders including Kagame that was perceived to have outsized influence, and the younger officers.[129]

The other official explanation given by the Rwandan government was security. Though the first Congo War had greatly diminished the ex-FAR forces, considerable insurgents remained.[130] Furthermore, while some of these fighters attempted to defend the Mobutu regime, many simply remained in North Kivu, due to the proximity to Rwanda. The threat had changed: there was no longer a large army, but small insurgent group. PALIR, a RDR splinter group, created an armed wing, Armée de Libération du Rwanda (ALIR), that operated in tandem to foment a rebellion in the Northwestern prefectures of Rwanda.[131]

Longman contends that Rwandan security concerns about the Eastern Congo were justified.[132] Reyntjens concedes that insurgent elements put “Kagame’s regime at risk”[133], but Prunier concludes that Kagame’s regime was not immediately in danger of collapse.[134] Armed Hutu forces within the Congo began attacking Rwandan with increased frequency in late 1997 and early 1998, especially in the Gisenyi and Ruhengeri prefectures. In December 1997 an attack on Gitarama Prison freed 500 Hutu accused of participation in the genocide. Attacks by Hutu armed groups on Tutsi civilians in Rwanda and counterinsurgency efforts by RPA forces led to what Longman calls a “virtual civil war” by early 1998.[135] According to this explanation Rwandan intervened primarily because border security concerns similar to those in the First War had not been properly addressed.[136] Reyntjens details the “less than enthusiastic” efforts of non-Tutsi FAC soldiers to combat Mai Mai and interahamwe fighters, including instances of FAC forces escorted Rwandan rebels to the border.[137]

The raids by interahamwe and ex-FAR forces into the Congo became more and more frequent at the end of 1997 and the beginning of 1998. Predictably, the RPA responded with force: they engaged in a brutal counterinsurgency campaign. Repatriated ex-FAR soldiers, who were targeted for recruitment by the infiltrators— or abacengezi—were killed preemptively. Mercenary helicopter pilots “operated without care” for civilians in their hunt for insurgents. The government also destroyed banana plantations to prevent ambushes, but in doing so severely constricted the food supply.[138]

Prunier asserts that Kabila actively recruited ex-FAR and interahamwe fighters. This recruitment gave Kabila loyal forces in an increasingly splintered FAC.[139] Reyntjens asserts that Kabila did recruit genocidaires before the outbreak of the War, but only after Rwandan invasion.[140] Longman is skeptical of this conclusion, declaring that it is “difficult to know” if Kabila actively recruited these genocidaires. However, Longman and Reyntjens concede that Hutu armed elements were actively using the Eastern Congo as a staging ground, just as they had in the lead-up to the First War.[141] Reyntjens judges that Kabila had neither the means nor the will to meet their security concerns.[142]

Furthermore, Rwanda’s neighbors were threatened by activity in the Eastern Congo. Sudan and Uganda were fighting a proxy war through the use of rebel groups. Sudanese intelligence was using the Eastern Congo to support ADF fighters. FDD fighters were still using the Eastern Congo as a staging ground. While neither regime was under immediate risk, these rebel groups were slowly chipping away at the stability and security of these states. Rwanda had a strong interest in preserving friendly regimes in both of these countries.[143]

While all authors examined consider Rwandan security to be endangered by the state of the Eastern Congo in 1997 and 1998, there are key divergences on the exact nature of the threat. Prunier seems convinced that Kabila was actively recruiting ex-FAR and interahamwe elements before the Rwandan invasion of the Congo. Longman remains neutral on this issue, while Reyntjens contends that ex-FAR and interahamwe elements were only recruited after the outbreak of the war. Curiously, Prunier seems to provide no convincing evidence for his claim. Longman cites a Congolese academic, but this academic was involved in the RCD, and so his writing should not be considered objective. Ultimately, Reyntjens claim is better supported and more convincing. However, crucially, all three concede that anti-RPF guerilla forces—ALIR, ex-FAR, and interahamwe—were using the Eastern Congo as base of operations. Furthermore, FAC troops were at the very least passively complicit in Rwandan-bound raids.

Longman finds several problems with security as the justification for Rwandan intervention in the Eastern Congo. One is the problem of scope. Longman contends that security threats in the Eastern Congo were isolated to that region, so while Rwandan action in the Kivus and even Katanga could be justified on the grounds of security, the attempt to topple Kabila could not be. Longman contends no “consensus” had emerged that Kabila himself was a security threat in the same way that Mobutu had been prior to the First Congo War. Longman justifies this analysis by citing the intervention of Angola and other African states on Kabila’s behalf. Longman also contends that Rwanda’s presence in the Eastern Congo actually increased support for and inflated membership of anti-Rwanda militia groups, thereby increasing the security risks posed by the East.

It should be obvious that Rwandan involvement in the Second Congo War cannot be traced to any individual motivation. The RPF probably intended for the invasion to serve several purposes. However, Longman’s argument that security is not a convincing explanation is problematic in several ways.

This argument is unconvincing for a variety of reasons. First, in the lead up to the initial Congo War Mobutu’s regime was a security risk for both Rwanda and Angola, but for separate reasons. UNITA was active in the Congo, and even in the Eastern Congo (Katanga), for nearly two decades before ex-FAR and interahamwe forces began operating in the Kivus. Both forces were supported actively by Mobutu. The War in 1997 represented a confluence of security concerns, but these concerns would have existed, and justified the toppling of the Mobutu regime, independent of one another.

Kabila’s regime could represent a security risk even if he had not actively formed an alliance with anti-Rwanda elements. As has been explained North and South Kivu were extremely volatile regions, and had been for decades. These regions were more densely populated than other parts of the Congo, leading to competition for land and resources. The region featured, both because of resource competition and the Banyamulenge question, ethnic tensions. While war had stopped and restarted in other parts of the Congo, the Kivus in particular had been in a state of near perpetual warfare since the early 1990s.

As has been detailed Mobutu oversaw decades of state decay and eventually collapse. By the early 1990s, the state had essentially ceased to exist. The military was non-functional as early as 1975, as seen by failed action in Angola, and struggled to contain domestic security disruptions as early as 1977 (Shaba I). The military’s worthlessness was on full display during the First Congo War. Border security was essentially nonexistent: a simple bribe to border guards allowed any amount of equipment and men to cross into the Congo.[144] Kabila had inherited a nonfunctional state, and his paranoid political style was not conducive to improvement. Kabila became very focused on maintaining his own power, and essentially ignored the problems in the East.

The FAC itself was extremely split, and not dedicated to solving security problems in the East. While parts of the FAC were essentially loyal to Rwanda, other sections were so completely hostile to Rwanda that they did little to limit the activity of anti-Rwanda groups. As a result of all these factors, porous borders were still a major problem, evidenced by the frequent raids into Rwanda’s northwestern provinces. In 1998 Kabila instructed the governor of South Kivu to “feed these boys” in reference to the Mai Mai.[145] While Kabila’s support of Mai Mai can be seen as anti-Rwanda, it can also be seen as an attempt to gain allies in the face of military divisions.

In the Second Congo War Rwanda was responding not just to specific threats but threats it was likely to face in the future. Collier mentions ethnic divisions are a factor increasing the likelihood of Civil War. Particularly, in states where one ethnicity is 45-90% of the population and the other is 10-15%.[146] This matches the ethnic distribution in Rwanda nearly perfectly, 85% Hutu and 15% Tutsi. Rwanda under the RPF was essentially dominated by the Tutsi minority. This was a recipe for disruption and even open rebellion. The raids launched into the Rwanda after the First Congo War were particularly threatening because they could “activate” the Hutu civilian population in Rwanda.

Sufficient state collapse creates an environment where the active consent of the political leadership is irrelevant. Angola intervened against Mobutu after he offered to discontinue his support of UNITA because they did not believe that he had sufficient authority over relevant elements in the Congo. Angola supported his overthrow because of what he could not do, rather than what he could do. Rwanda’s second invasion of the Congo can be seen as a response to state failure, and if state failure is the outgrowth of incompetent political leadership, then replacing the regime is a way to address the root cause of Rwanda’s security concerns.

However, there is a problem with this analysis. First, if Rwanda saw state failure as a root cause of their security concerns, why had they replaced Mobutu with Kabila? Kabila was chosen for his incompetence—he was regarded as easy to manipulate—rather than his ability as a statesman. Secondly, how would the installation of a new leader by a foreign invasion address a decades long process of state decay? The answers to these questions rest on two factors: the geopolitical relationship between the Congo and Rwanda and the psychology of the RPF.

The Congo is much larger and much more resource rich than Rwanda. The fact that Rwanda had successfully invaded the Congo, and with the help of a few other nations, toppled the Mobutu regime was a reflection of the massive state failure experienced by the Congo, not the natural state of things. Therefore, the RPF had an incentive to install a leader in the Congo that could be easily manipulated and would be loyal to the Rwanda. This puppet would have to an incredibly weak leader. This desire for a weak leader is at odds with the desire for decades of state failure to be reversed, and for the East to no longer function as a staging ground for anti-Rwanda activities. Any Rwandan solution to this problem would be imperfect.

The fact that Rwanda attempted to address this problem by repeating a successful military intervention is a reflection of RPF psychology. As has been detailed the RPF was primarily a military organization that repeatedly applied simple military solutions to complex problems. The systematic killings during and after the genocide, actions towards refugee camps in Kibeho, the first invasion of the Congo and the breakup of Congo refugee camps, brutal counterinsurgency efforts in northwestern Rwanda, and RPA brutality towards civilians in the Congo all display the predilection for violence. These were all responses to complex political cultural and military problems, but the responses universally reflect a “way of the gun” mentality.[147] This explanation dovetails with Longman’s political triumphalism theory. The RPF’s extreme faith in their own military abilities, their belief that they were invincible, may have contributed to their beliefs that simple military action could solve complex situations.

In conclusion, it is possible for Rwanda to have correctly identified legitimate security concerns in the Eastern Congo as an outgrowth of state failure, and that in turn an outgrowth of incompetent political leadership, and to have sought the wrong solution. Constrained by psychological preferences and geopolitical reality, Rwanda sought to address a complex problem with a flamboyant military response. Rwanda should be regarded as a rational actor, but an actor nonetheless limited by perspective and circumstance. This explains why Rwanda took an action that seemed unlikely to improve their security situation, while still responding primarily to security concerns.

This explanation dovetails nicely with explanation offered by Prunier: the murder of Seth Sendashonga. The “hard core” of the RPF that was politically hindered by the threat of Sendashonga suddenly had the latitude to pursue their desired policies. Furthermore, Longman’s assertion that the Second Congo War was meant to enforce internal unity fits into a larger argument about the RPF worldview. The RPF is seeking, on small and large questions, a military solution to complex problems.

Luanda’s Reactive Intervention

“Angola has become a gigantic corpse filled with diamonds and bleeding oil.”

Pedro Rosa Mendes, RDP Africa, October 1997.

Angola dramatically split with Rwandan and Uganda in the Second Congo War by supporting the Kabila regime against the advancing rebels. Angola’s intervention in the Second Congo War was similar in character to its intervention in the first: it came after the initial invasion by Rwanda and Uganda and was largely a reactive decision forced by the actions of Rwanda and Uganda.

As has been detailed Angola’s intervention against Mobutu in the First Congo War was mainly motivated by a desire to damage UNITA. The intervention of the FAA allowed Angola to seek and destroy UNITA bases and the “secret army” as well as destroy UNITA diamond selling networks. This intervention was partially successful, but several thousand fighters escaped into Angola.

There are several explanations for the Angolan intervention in the Congo War. The first is a bundle of sentimental factors including a debt to the Katangan Tigers and a loyalty to Kabila. The second is a response to Rwandan and Ugandan dealings with UNITA. The third is a desire to limit the fighting capabilities of UNITA by attacking economic support networks, in the context of domestic security threat. Finally, the Angolan government and individual Angolans have benefitted economically from looting or gaining control of Congo resources.