Adaptation of Japanese Cosplay Culture into Malaysian Society

Info: 17272 words (69 pages) Dissertation

Published: 10th Dec 2019

Tagged: International Studies

Contents Page(s)

Chapter 1. Theory and Methodology

1.2.1 Group and Collective Identity

1.6 Method One — Online Ethnographic Interview

1.7 Method Two — Autoethnography

1.8 Analysis and Interpretation

Chapter 2: Introduction to Cosplay

2.3 Japanese Animation and Manga 25

Chapter 3: Cosplay as an Identity Practice 27

3.0 Identity 28

3.1 Identity of a Cosplayer 30

3.1.1 Group Identity 32

3.1.2 Online and Offline identities 33

3.2 Escapism and Living in Two worlds 34

Abstract

This dissertation analyses the adaptation of Japanese Cosplay Culture into Malaysian societies by engaging theories that have claimed cosplay to be a practice of identity and self-concept. This study will highlight on the formation of identity and self-concept when one participates in cosplay and the meaning of Japanese Cosplay culture to Malaysians. This study then uses this idea together with methods such as ethnographic research by interviewing two active cosplayers from the community and an autoethnographic reflection to examine how identity is created by looking at the theories of culture, identity and self-concept and place attachment.

Introduction

The rapid growth of Japanese comics and animation, known as ‘manga’ and ‘anime’ has been expanding to different parts of the world since the late 1980’s and 1990’s and fans in North America have been participating in costume fandom ‘from as far back as the first World Science Fiction Convention (Worldcon), held in New York City from July 2 to 4, 1949’ (Pollak, 2006: 2). First, it is necessary to describe the concepts of cosplay culture, manga and anime as this will assist in understanding the usage of terms throughout this study.

‘Cosplay, a shortened form of kosupure, is a combination of the Japanese words “costume” (コス) and “play” (プレ)’ (Winge, 2006: 67). Cosplay is a type of costume fandom in which participants, labelled in the cosplay community as “cosplayers” dress in costumes, armours or fashion accessories to represent a specific fictional character, normally from Japanese animation (anime), video games, comics, graphic novels (manga) or science fiction/fantasy media. Cosplayers will mimic their characters as closely as possible to embody that character in conventions. Anime, is Japanese animation series which derives from manga or light novels, while Manga, are Japanese comics, or graphic novels. Researcher Susan J. Napier (2001 and 2007) has explored into this subject by interviewing cosplayers and had short analyses about Japanese cosplay and identity. However, Napier quoted, ‘describing manga and animé simply as Japanese cartoons does not do justice to the variety and depth of the culture’ (Napier, 2005: 6-7). Though this is a small representation of the central concept it will be sufficient enough to understand the terminology used in this theoretical context of this study as further elaborations of the terminologies will be discussed in chapter 2.

The past decade has seen the rapid development of cosplay subculture in many aspects. Hence, it is interesting to look into this subject because limited academic work has been said about this practice in Malaysia as how a practice from Japan can be transplanted into another country with different beliefs and culture.

Hence, to understand the meaning of Japanese Cosplay culture to Malaysian cosplayers, the following questions below will be analysed and answered in Chapter 3:

- How does cosplay work as a practice of identity and self-concept?

- How do cosplayers embody a character/ another identity and escape the mundane everyday life?

- How does cosplay give a sense of ‘home’ towards cosplayers?

- What does it mean to be a Malaysian cosplayer?

In chapter 1, the theoretical foundation of this study, methodologies and my chosen methods used will be discussed. To analyse this study, I will answer my questions through an ethnography study, autoethnographic reflection as well as using online interview methods. As a cosplayer that also participates in this culture, I will reflect on my own experience as a Malaysian cosplayer for the autoethnography. Furthermore, two participants were chosen for an online interview for my ethnographic study. Next, Chapter 2 will give an introduction to cosplay, how cosplay is like in Malaysia and give a short elaboration of anime and manga to set this study into context. Lastly, Chapter 3 will discuss about the main findings of my study as well as the emerging themes such as cosplay as an identity practice, escapism, the definition of ‘home’ in cosplay, how cosplay is like living in two worlds and lastly, to conclude about the Malaysian cosplay identity.

Chapter 1. Theory and Methodology

1.0 Literature Review

The first chapter of this dissertation will be a literature review. For the past decade, there have been limited research materials about anime, manga as well as cosplay in the academic world. Therefore, most of this study will be using Napier’s (2007) work, ‘From Impressionism to Anime’ to view on cosplay. Currently, there is only one work found online for cosplay in the Malaysian context and it is an article from Paidi, Akhir and Lee (2014) ‘Reviewing the Concept of Subculture: Japanese Cosplay in Malaysia’. With limited resources, the adaptation of cosplay in Malaysia will be further examined in this study. The other key books that will be used for the theoretical context of this study will be ‘An Introductory Guide to Cultural Theory and Popular Culture’ by Storey (1993), ‘Social Identity’ by Jenkins (2008), ‘Self-concept and Identity’ by Oyserman (2004) and ‘Space and Place’ by Tuan (1977).

1.1 Culture

Several authors have attempted to provide a definition of what is culture. Williams (1983), calls culture ‘one of the two or three most complicated words in the English language’ (1983: 87) and defines culture in 3 broad definitions. Firstly, Williams defines culture as ‘a general process of intellectual, spiritual and aesthetic development’ (1983: 90). Secondly, he suggest that the use of the word culture is to suggest ‘a particular way of life, whether of a people, a period or a group’ (1983: 90) and lastly, he defines culture could be used to refer to ‘the works and practices of intellectual and especially artistic activity’ (1983: 90). Storey stated ‘to speak of popular culture usually means to mobilise the second and third meanings of the word culture (1993: 2)’. The second meaning as stated from the previous section above suggest culture as ‘a particular way of life’ like having practices like celebrating Easter or Christmas or even youth subcultures like costume fandom (cosplay) which is the main topic of this study and I will give a further elaboration in Chapter 2. The third meaning of culture would refer to ‘the works and practices of intellectual and especially artistic activity’ that are usually referred to as cultural texts like pop music, comics and soap opera. Storey pointed out people would normally associate culture with the first definition when thinking about popular culture.

1.1.1 Subculture

The concept of subculture has been widely used in many studies and in this dissertation, I will view cosplay as one of the many subcultures. There is no real definition of subculture, but the theoretical concept and values itself have been debated by many scholars. Gelder (2005) calls this trend “the “rhetoric of newness (cited in Williams, 2011: 36) and two different terms that have been argued by Maffesoli (1996) and Muggleton (1997), name the term subculture ‘neo-tribes’ or ‘post-subculture’ respectively. Other scholars like Roberts & Keith (1978) and Yinger (1960) tried to coin the term ‘counterculture’ and ‘contraculture’ but there were less successful. Through all these different terms, Williams (2011) said that all the terms were ‘too broad, too biased, or simply out of date’ (Williams, 2011: 3).

In spite of all these debates, Johnston and Snow (1998) proposed five elements to the conceptualization of subculture. They suggested that first, subculture, is an autonomous from the larger culture and subcultures ‘include some of its values and behavioral norms’ (1998: 474). Second, subcultures are distinguished by behaviors markers such as ‘style, demeanor, and argot’ (ibid.,). Third, subcultures are easily differentiated by ‘set of beliefs, interests attributions and values that are shared and elaborated’ (ibid.,). Fourth, subcultures are categorised by ‘a common fate or dilemma derived from their position in the larger social structure’ (ibid.,) and lastly, they are characterised by ‘patterned interactions and relationships within the subculture and between the subculture and larger social structure’ (ibid.,).

Jenkins defines the cosplay community as ‘a cultural community, one which shares a common mode of reception, a common set of critical categories and practices, a tradition of aesthetic production, and a set of social norms and expectations’ (Tulloch & Jenkins, 1995: 143). Subcultures allow participants to participate in a ‘genuinely new and unique culture’ that is ‘[f]reed from material constraints…[and] offer[s] an endless array of possibilities to a world that seems increasingly fettered by the intractable realities of ethnic, religious, and national identifications’ (Napier, 2007: 210). Therefore, cosplay is a subculture because it is a group of individuals who shares similar goals, values, taste and style and these element makes subcultures to be easily differentiated from larger and other groups.

1.2 Identity

The discussion about the theories of identity covers a large portion of this study. Richard Jenkins (2008) referred to The Oxford English Dictionary that identity offers a Latin root – identitas,from idem, ‘the same’ and it has two meanings. The first definition refers to ‘the sameness of objects, as in A1 is identical to A2 but not to B1’ (2008: 17). The second definition refers to ‘the consistency or continuity over time that is the basis for establishing and grasping the definiteness and distinctiveness of something’ (2008: 17). Jenkins refers that the notion of identity normally involves ‘two criteria of comparison between persons or things: similarity and difference’ (2008: 17) and argues that there is something active about identity that cannot fail to be considered, that identity ‘isn’t ‘just there’, it’s not a ‘thing’ (2008: 17) and it must always be established. Therefore, Jenkins pointed out identity is ‘used to classify things or persons; to associate oneself with, or attach oneself to, something or someone else (such as a friend, a sports team or an ideology)’ (2008: 17).

1.2.1 Group and Collective Identity

In this study, I will draw out Jenkins first idea of collective identity for cosplay groups and only briefly touch the topic about group and collective identity because this study will focus more on self-concept. The representation of groups has been ‘periodically questioned by investigators over the last 50 or so years’. (Worchel and Coutant, 2004: 186). Jenkins defines group identity as a ‘product of collective internal definition’ (2008: 105). This is because in groups, we will draw upon identifications of similarity and differences, and that process generates group identities. However, Jenkins (2008) argues that group and collective identification ‘evokes powerful imagery of people who are in some respect(s) apparently similar to each other’ (2008: 102) and he suggested that there are two different types of collectivity. First, the collectivity of identifying themselves: ‘who and what they are’ (ibid., 104). Second, members that are ignorant of their membership ‘or even of the collectivity existence’ (ibid.,). However, Nadel (1951) argues for emphasising that these are not two kinds of collectivity but rather ‘different ways of looking at interaction, at ‘individuals in co-activity’ (1951: 80). Both of the researchers are equally right because both of these definitions are abstractions from data about ‘co-activity’ but the similarity in both of their contexts is they gave a fundamental concept of being in a group.

1.2.2 Self-concept

‘Self-concept and identity provide answers to the basic questions “Who am I?”, “Where do I belong?”, and “How do I fit (or fit in)?”’ (Oyserman, 2004: 5) The self-concept within the identity theory is about how oneself represents and organises current self-knowledge and guides how new self-knowledge is perceived. ‘Being human means being conscious of having a self and the nature of the self is central to what it means to be human’ (Lewis, 1990: 277). Oyserman pointed out self-concept is ‘to help organize experience, focus motivation, regulate emotion, and guide social interaction’ (2004: 8). By having an identity or a sense of belonging, it is easier ‘improving oneself, knowing oneself, discovering oneself, creating oneself, … [these] are all essential self-projects, central to our understanding of what self-concept and identity are and how they work’ (Oyserman, 2004: 5). Self-concept relates to cosplay because this concept associates with one’s sense of belonging and fitting into the world. Oyserman commented on Swann’s self-verification theory by saying ‘… individuals are motivated to preserve self-definitions and will do so by creating a social reality that conforms to their self-view’ (Oyserman, 2004: 9). This proves that self-concept within the identity theory is a social force shaping our reactions, perceptions and behaviours to others. The self-concept theory is further elaborated with the early writings of James (1890/1950), stating that ‘feeling good about oneself, evaluating oneself positively, feeling that one is a person of worth, have been described as a basic goal of the self-concept’ (ibid., 9). Oyserman agrees with theorists like Haslam, Oakes, Turner & McGarty (1996) that positive self-esteem is a fundamental human need and ‘individuals prefer to feel good about themselves and so will self-define in such a way as to maintain positive self-feelings’ (ibid., 9). By looking at Oyserman’s point of view, a person will try to pursue or obtain positive feelings to feel good but she also argues that a person will go to the lengths of ‘compar[ing] the self to other ways that reflect favorably on the self’ (Beauregard & Dunning, cited in Oyserman, 2004: 9). Hence, self-concept is an information processor that filters important self-relevant information. ‘[E]ven if negative, [it] is maintained in the face of contradictory information’ (Oyserman, 2004: 9) and differs by how people perceive and process it.

1.3 Attachment to a Place

Place attachment, often used in the realm of environmental psychology is defined how an individual develops a social attachment between themselves and a place. Tuan, a human geographer states clearly that ‘Place … is more than location’ (Tuan, cited in Moores, 2012: 27). Particularly, Tuan’s approach for a place is the formation of affective attachment towards a place and how one dwells in one. He argues that place ‘exists at different scales’ (1977: 149); at a larger scale of the nation or a region, Tuan had feelings of ‘attachment to homeland’ (1977: 149), on a micro scale, Tuan added that ‘[p]lace can be as small as the corner of a room’ (1996 [1974]: 455). Therefore, using Tuan’s theory of attachment to a place, I will emphasise on how cosplay is a special ‘place’ for me in this study. Moores (2012) also mentioned about a sense of place in his work. When Tuan wanted to find out ‘How long does it take to know a place?’ Moores answered, ‘As a habit field or a field of care is formed, the space … comes to feel ‘thoroughly familiar’’ (Moores, 2012: 32). Therefore, through stylised repetition, a place is explored and it will feel familiar to oneself. Moores also added that one may also get to know the things that may happen and the styles of a place on a regular basis. For Tuan, the something more to place has to do precisely with matters of dwelling or habitation, he argues that place is constituted when locations are routinely lived-in and when what he calls a ‘habit field’ or a ‘field of care’ (1996 [1974]: 451-2)’ (Tuan, cited in Moores, 2012:27). This ‘field of care’ is formed when there is an emotional attachment to a place and will be brought up in the main findings in Chapter 3.

1.4 Methodology

This section will discuss the overall methodology and methods used for this dissertation. To understand my topic further, it was certain that different types of research materials were needed to answer the questions I have set out for this study. As Cosplay is a complex subculture and not widely known by many people, understanding the context of the culture from within was essential. O’Reilly (2005) pointed out that ethnographic methods acknowledge ‘the complexity of human experience and the need to research it by close and sustained observation of human behaviour’ (2005: 2). Ethnography seeks to understand a cultural experience from the point of view of the participants. Therefore, ethnographic methods were chosen for my methodology. This study had two different methods used — Online Ethnographic Interview and Autoethnography Reflection; a combination of interviewing other cosplayers and also reflecting on my own opinion of cosplay culture. Gray (2003) approaches ethnography methods by stating ‘[d]escription is piled upon description with ranges of voices coming through the written text, standing there as evidence of the authentic experience or account of way of life’. (2003: 20). This is because we as humans operate by going through daily structures and routines, we make sense through observing and picking up clues based on our social and cultural competence, through relating to others via conversation and discussion. It is also important to note how fieldwork research and textual practice ‘reproduce and implicate selves, relationships and personal identities’ (Coffey, 1999: 1). Therefore, by conversing and discussing with cosplayers through interviews as well as reflecting myself as a cosplayer, it will be a huge contribution to my study and it can help back my findings.

1.4.1 Ethics

From the beginning of the design process to the provisional decisions and methodology, it is important to consider ethical issues from the early stages of a research project. Therefore, after submitting an ethnographic approval, this project is reviewed and acknowledged by the University of Sunderland’s Ethics Committee. The main ethical issues I have identified are informed consent and confidentiality. Oliver (2010) pointed out that in a piece of ethnographic or field research, the aim is ‘to explore the life histories of a relatively small number of individuals, then it may be more important to ensure that they understand the purpose and function of the research, before agreeing to take part’ (2010: 10). I obtained informed consent from my main participants before the ethnographic study began via a signed consent form online. Next, issues of confidentiality and anonymity will be taken into consideration throughout all stages in the research process via participant information sheet (refer to Appendix A). Participants will be told beforehand that they will be will remain anonymous and pseudonyms will be used when referring to a participant within the final report to preserve their anonymity and confidentiality. The final pseudo names chosen for both participants are Dovah and Sally.

Apart from these ethical considerations, interview topics that will hurt my participants emotionally will not be brought up. Therefore, to reduce these issues, interviews are designed as such to not harm, cause stress or provoke participants in any way. Lastly, research findings with anyone not of the significance of this study will not be discussed in any forms of social media and all evidence of the research study will be destroyed after received a grading for this study.

1.5 Pilot Interview

Before conducting the ethnographic online interview, a pilot interview was done with another close cosplayer friend. A pilot interview is an ‘especially effective way of dealing with the overall problem of increasing the reliability of case studies’ (Yin, 2009: 67). This aim was done so to refine my research material collection plans with respect to both the content of the data and the procedures to be followed. By doing so, this act was to confirm there were no technical difficulties during the real interview and to make sure the planned question were in the right direction to both participants.

During the pilot interview, I tried questioning the participant in different angles using open-ended questions as well as closed-ended questions referring to the interview questions I have designed. This is done so to notice any questions did offend them in any way so I do not harm my participants during the real interview emotionally. 10 minutes briefly into the interview, the main issue of my pilot interview emerged. The phrases and sentences used did not convey the meaning of the intended question. Therefore, to solve this issue, further background elaboration on the topic was needed and modifications were required down for the second version of interview questions.

After making final modifications to the second version of interview questions, a second pilot interview was proposed with the participant again and the interview went smoothly; the preparations for the online ethnographic interview was complete.

1.6 Method One — Online Ethnographic Interview

Firstly, given my dissertation topic ‘The Adaptation of Japanese Cosplay Culture in Malaysian Society’, a study that is based on Malaysia, I could not have done an on-site ethnographic study because I am currently studying due to geographical disperse; the United Kingdom. Therefore, an online ethnographic interview was opted instead. Two participants selected were from people that are from the cosplay community in Malaysia and they were cosplayers that have been cosplaying for more than four years. Before both of the interviews, the ideal criteria was to select two different participants that occupy different positions within the cosplay community so I could have two very different views on the what cosplay means to them and their views on the cosplay community in general. After searching through a long list of cosplayers on various social media platforms that Malaysian cosplayers use frequently (Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Cure & WorldCosplay), two possible candidates that were likely to be the most suitable for the study were recruited via online after explaining to them about this dissertation project. A day before the interview, both participants received a participant information leaflet (refer to Appendix A) detailing what the aims were within this ethnographic study and signed a consent form to allow the interview to proceed via Skype online.

Participant 1 was a cosplayer that has been cosplaying for four years and she is a student from a private university studying Business Tourism. Although she has been cosplaying for four years, she is not that well known in the cosplay community due to the lack of participation in events and also does not join cosplay competitions much. She prefers to mix with cosplayers that she knows rather than new ones because she is more introverted.

Participant 2 was a cosplayer that has been cosplaying for four years as well but she is a working adult, currently working a nine-to-five job in a company that sells electrical appliances. She is very well known in the cosplay community because of her very accurate cosplay of game characters and also she is well known for her performances and skits in cosplay competitions. Due to her fame, she is also a cosplay judge for mini cosplay competitions around Malaysia and she also hosts cosplay workshops for newcomers for cosplay.

The questions asked during the interview were mostly open-ended. Both participants were asked open-ended questions so they could have the opportunity to express their own opinions about the cosplay community and their passion towards their hobby. Although 13 interview questions were carefully planned, the interview did not follow the 13 planned questions because the topic would stray away from the main topic. However, the topics that strayed away were productive and it gave unanticipated research materials that were really useful for this study; an answer to certain topics and it branched out into more subtopics that can be used for the further context of my study. Hence, research materials that were appropriate and useful were collected in the end.

1.7 Method Two — Autoethnography

When conducting autoethnography, it is important to emphasis on both ‘self-reflexive questioning’ and an equal treatment of the self and the research subject (other fans) in terms of theoretical analysis (Hills, 2002: 81). Autoethnographies ‘are highly personalized accounts that draw upon the experience of the author/researcher for the purposes of extending sociological understanding’ (Sparkes, 2000: 21). It determines knowledge of past research that was made on a topic and seek to contribute to this research. As a cosplayer myself, I decided to write a personal reflection on how cosplay has influenced me in this autoethnography. Although I have been cosplaying for 5 years now and I am familiar with the Malaysian cosplay community, ‘[i]t takes a tremendous effort of will and imagination to stop seeing things that are conventionally ‘there’ to be seen (Becker, 1971: 10). For an example, while I was conducting my autoethnography, I needed to understand that the readers viewing my study do not understand slangs and terms that cosplayers usually use. Hence, I had to immerse myself and think about the phrases and terms used as well as stepping out from my own ‘box’ to view this study from a reader’s perspective and to make sure if it was easily comprehensible. Therefore, Adams & Jones (2011) argues that autoethnography provides a space for us to ‘create a relationship embodied in the performance of writing and reading that is reflective, critical, loving and chosen in solidarity’ (2011: 333).

Autoethnography draws different ways of doing research as well as representing the subject by combining the characteristics of autobiography and ethnography. It also considers the ways how other cosplayers experience similar epiphanies when participating in this cultural experience. However, there are limitations to autoethnography, Coffey (1999) refers ‘[o]ver-familiarity is considered a problem, rather than a strength, at least initially’ (1999: 20) and it is premised on a self-evident distance between a self and another, I argue that being able to familiarise with the case I work on as a researcher is easier to divest my knowledge and personhood to achieve an eventual understanding for this study.

The perspective of being a cosplayer enabled me to find my research materials easily on the web by using common phrases that cosplayers used and by applying all the knowledge I learned from events that I have attended for the past 5 years. Besides, it also gave me a good overview of the Malaysian cosplay community as a whole. Being a participant in this subculture made it is easier to find my research participants for this study as well as going through the filtering process. This is because cosplayers used different social media platforms and I knew most of the cosplayers that were on my friend list and the positions they occupy in the cosplay community in general. Hence, being familiar with the fieldwork of my own study helps ease the collection and compilation of the research materials needed.

1.8 Analysis and Interpretation

After collecting the research materials, the interviews were transcribed and it was inserted into a table (Refer to the table in Appendix B) with questions as well as the answers of both participants and my autoethnographic reflection. This is done so it would be easier to compare as well as refer to both participants’ views on cosplay and coding can be done efficiently. The interview transcribe was colour coded to identify different categories of meanings like emotions, flashbacks, personal opinion as well as the theories that were emerging during the course of contextualising and about cosplay. This is because coding can be used to ‘organize the interview texts, to concentrate the meanings into forms that can be presented in a relatively short space, and to work out implicit meanings of what was said’ (Brinkmann & Kvale, 2015: 201).

Gibbs (2007) pointed out that coding demands the use of “code memos” where researchers ‘records the names of the different codes, who coded which parts of the material … the definitions of the codes used, and the notes about the researcher’s thoughts about the code’ (2007: 41). During the interview coding, data instances were constantly compared for similarities and differences between both participants as well as my autoethnography. I noticed the lines that were colour coded were slightly similar but distinguishable that cosplay is related to the theory of identity. Through this act of comparing, it led me to a sampling of new data as well as writing a theoretical memorandum about living in two worlds that will be explained in Chapter 3. Through further reading along the lines of the colour coded words, the theory of self-concept emerged from the transcript and it gave a strong backbone towards this study. With this, a more focused coding was undertaken, and the analysis became more descriptive to more theoretical levels that provided more analysis for this study.

Chapter 2: Introduction to Cosplay

2.0 Introduction to Cosplay

As Winge points out, ‘Cosplay, a shortened form of kosupure, is a combination of the Japanese words “costume” (コス) and “play” (プレ)’ (Winge, 2006: 67). Cosplay is a type of costume fandom in which participants, labelled in the cosplay community as “cosplayers” dress in costumes, armours or fashion accessories to represent a specific fictional character, normally from Japanese animation, video games, comics, graphic novels or science fiction/fantasy media. Cosplay has no age range, it is common to see grandmothers dressed up as fairy godmothers or villains bringing their grandchildren dressing up as a cute Disney princess or superheroes in cosplay conventions.

The general origin of cosplay hails from Japan but there are no actual facts of when the cosplay culture started. However, the credit for the word ‘cosplay’ goes to Nobuyuki Takahashi, a Japanese reporter of Studio Hard when he first used the word in a Japanese magazine called My Anime during 1984. He used the term ‘cosplay’ to describe the fans of science fiction and fantasy he saw at World Con Los Angeles that year ‘who were wearing costumes of their favourite characters’ (Winge, 2006: 66). As he thought translating the word ‘masquerade’ to the Japanese readers, he thought that the word was too outdated to describe the notion of cosplay. Therefore, the invention of this new word Takahashi made, ’cosplay’, revolves around the pair of two words, ‘costume’ (kosu (コス), in Japanese) and ‘play’ (pure (プレ), in Japanese).

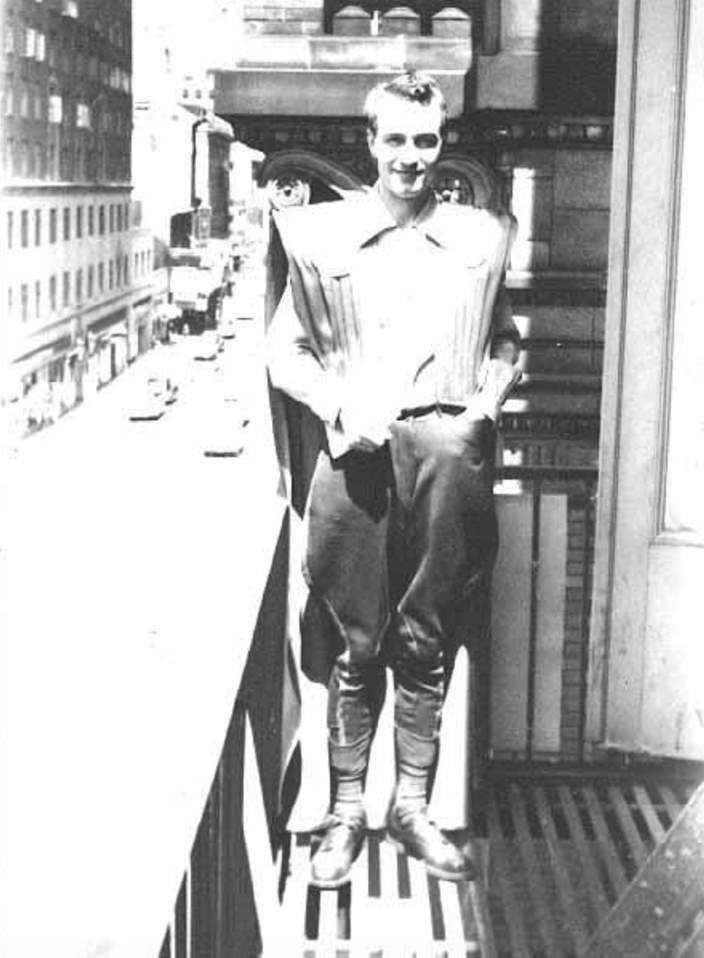

Not just that, fans in North America have been participating in costume fandom from as far back as the first World Science Fiction Convention (Worldcon), held in New York City from July 2 to 4, 1949 (Pollak, 2006: 2). One who was labelled “The Greatest Fan of Science Fiction Who Ever Lived”, Forrest J. Ackerman, attended the first ever Worldcon, in his homemade “futuristicostume” (Figure 1). Inspired by the 1933 film Things to Come and the artwork of pulp illustrator Frank R. Paul, ‘Ackerman was dressed as a futuristic time traveller’ (Ackerman, 1994: 4; Corliss, 2008). ‘Ackerman strode the streets looking like a proto-superhero in the company of lady friend and fellow Esperantist Morojo’ (O’ Brien, 2012: 24).

Figure 1: Forrest J. Ackerman’s “futuristicostume” in 1939 (Source: yahoo.com, 2014)

Ackerman’s futuristic costume made a lasting impression, and a small masquerade was formed at the second Worldcon, held in Chicago in 1940. From that day onwards, the first few decades for Worldcon has been a masquerade. ‘There was a dance band, and tables, and drinks, and now and then people got up and danced’ (Resnick, 2015: 106). As the masquerades got bigger, the dancing ended, the bands vanished, and by the early 1970s, it was much as you see it today: strictly a costume competition.

Besides that, the world renowned comic convention, Comic-Con, was first held in 1970 at Grant Hotel, San Diego, United States. There were 300 attendees, but costuming did not play a prominent role at the event compared to 2016. During 2016, Comic-Con was attended by 135,000 con-goers held in a 460,000 square feet exhibition hall in San Diego.

The increasing number of fandom-based and cosplay events along with the geographical spread of these conventions has certainly indicated eminently the popularity of cosplay. By the 20th century, Japan’s Manga and Anime culture has spread worldwide and Japan decided to host the World Cosplay Summit. It began in 2003 in a famous shopping district in Nagoya, Japan, with an aim to produce a new international friendship with cosplayers from all around the world. The World Cosplay Summit started off bonding cosplayers from four countries, including Japan to join their festivities which includes an international competition and a cosplay parade. In 2012, the World Cosplay Summit managed to link up to 20 countries, including Malaysia, to join The World Cosplay Championship where cosplayers around the world display their best performances and skits on a grand stage to determine the grand champion of cosplay each year. Cosplayers that put up their best costume and unique execution of art direction will be crowned the winner for the international championship every year.

2.1 Cosplay in Malaysia

The cosplay community in Malaysia is increasing slowly and steadily. Cosplay is performed not only at conventions, but also in ‘various urban areas as well’ (Napier, 2007: 160). In 2002, Sequential Arts Youth Society (SAYS Youth Society), a non-profit organisation, wanted to educate Malaysians about the expanding Anime, Comics and Games (ACG) community in Malaysia and made a goal to create an event that allows local and international artists and talents to push Malaysia’s creative industry. Hence, Comic Fiesta has been Malaysia’s longest-running ACG convention since 2002.

A cosplay convention is where fans of Japanese animation, normally called “Otakus” gather together to buy anime and manga comics as well as merchandises, take part in costume competitions and see their favourite seiyuu (voice actors in Japanese), celebrity cosplayer, and Japanese singers. Napier suggested that Otaku is a Japanese word, which can be loosely translated as “obsessive fan” or “technogeek” (2007: 2). Comic Fiesta started off as a small exhibition at the Selangor Chinese Assembly Hall in Kuala Lumpur with only 200 to 300 attendees. As time passed and the love for ACG events in Malaysia expanded, Comic Fiesta is now held in Malaysia’s biggest exhibition hall, Kuala Lumpur Convention Centre (KLCC) and attracting almost 46,000 attendees in 2015. According to star2.com, ‘since its inception in 2002, Malaysia’s largest animation, comics and games (ACG) event, Comic Fiesta, has grown into one of the biggest events of its kind in South-East Asia, and has become a must-go event for Malaysian illustrators, comic artists, cosplayers and fans.’ Cosplayers from different races, age and countries gather together in Malaysia during December just because of their passion towards this hobby.

2.2 Malaysian Cosplay Culture

In a country fill with diverse religion, races and culture, Malaysia is a rather conservative country as 60 percent of the population are Muslims. Though the cosplay community is largely dominated by Chinese, it is normal to see Muslim cosplayers trying to take on cosplay as a hobby as well. In Malaysia, most Muslim women wear a hijab after they reach puberty. It is a personal choice for them as a means of fulfilling God’s commandment for modesty as well as visibly expressing their Muslim identity. Besides, the hijab is often accompanied with wearing loose and non-revealing clothing. The picture below is an example of a Hijab (Head Scarf) cosplayer from Malaysia, Marsha Erika Diana.

Figure 2: From left, Judy Hopps from Zootopia and a Hijab Cosplayer from Malaysia (Source: facebook.com, 2016)

Marsha cosplayed as Judy Hopps, from Disney animation Zootopia. Most Judy cosplayers use grey wigs to symbolise Judy’s fur but Marsha used her creativity to manipulate the hijab as the wig and take on Judy’s character as her own. Without failing to respect her own religion and cultural beliefs, Marsha put her own twist in cosplay using her creativity and adapted it into her own style of cosplay.

In the interview, Sally quoted, ‘[t]he younger generations are slowly opening up. The way I see itself, Malays can’t wear wigs because of their culture and tradition, so they modify it by using their hijab to turn into like similar to the wig. So I find it really cool’ (Sally, Interview, 2016).

Though Malaysia is a conservative country, Malaysians are quite open-minded towards the idea of this Japanese culture and slowly accepting the fact that this new hobby is here to stay. This can be seen evidently by the increase of ACG events every 2 weeks. Through the years, the numbers of cosplayers cosplaying in events are increasing and Dovah also pointed out, ‘[e]ven commercial companies are engaging cosplayers for promotions and also advertisements and we are probably not seen as “crazy” anymore but “weird”’. (Dovah, Interview, 2016).

2.3 Japanese Animation and Manga

As cosplay is a type of costume fandom where cosplayers dress in costumes and/or armours to represent a specific fictional character, mostly from Japanese animation (anime) and comics (manga), this section will give a brief introduction to Japanese Animation and Manga.

Anime, a short for Japanese Animation, and Manga, which derives from the Japanese word ‘漫画’ (manga, in Japanese), is slowly increasing its widespread throughout the world since the 1980s. Anime now appears in the internet, video stores, television broadcasts and even movie theatres. It has been uncompromisingly true to its Japanese roots, not only in terms of religious, social, and cultural reference. Film scholar Susan Pointon (1997) noted that anime is strongly related to ‘character conception, narrative, structure, themes, and imagery’. (1997: 41) Most anime are adaptations from mangas and light novels, with a diverse range of genres that appeals to a wide demographic audience from children to adults. Subsequently, manga has also become vastly popular, from just a few narrow offerings in comic book stores, manga is seen ‘occupying increasingly large sections of such mainstream bookstore chains such as Barnes and Noble and Borders, and even inspiring Western versions of the genre’ (Napier, 2007: 5). For an example, Pokemon has received a Western adaptation in the United States. In a kid’s channel, 4Kids decided to localise Pokemon and changing Japanese products into western products so it would have higher growth, engagement and local relevance. Instead of throwing a Japanese rice ball (onigiri) to the main character, they decided to change it to a sandwich instead.

Figure 3: A side-by-side comparison of two different versions of Pokemon.(Source: dorkly.com, 2016)

Hence, the widespread of Japanese animation and manga have constituted an important part of Japanese cultural influence abroad.

Chapter 3: Cosplay as an Identity Practice

3.0 Identity

The main theme of this chapter revolves around identity and self-concept. In this chapter, I am going to examine my research findings and find the ways my subjects and I engage through cosplay. I will start this chapter with an autoethnography reflection on myself as a cosplayer, drawing out themes in the theoretical context of this study such as the identity, group identity, online and offline identities, escapism and living in two worlds.

3.0.1 The Love of Makeup

Ever since I was a young child, I always found myself searching and rummaging through my mother’s makeup and played with her different coloured lipsticks, eyeshadows and also being fascinated by all the different brushes she had in her room. Back then, I was still young and I didn’t know the value of makeup. Ever since I accidentally broke my mother’s favourite lipstick and she found out, I thought that I would get a huge lecture from the both of my parents for touching her makeup without her permission. Instead, my parents bought me a magazine called ‘Sabrina’s Secrets’. It’s a magazine originated from the animation and Disney movie, ‘Sabrina the Teenage Witch’ and it came with a random makeup product every issue. The first issue gave a beautiful glittery purple makeup box and a lip gloss. The box had little numbers labelled on every empty slot so I had to wait every week to get a new makeup item that will fit perfectly into the numbered slots.

Being excited knowing I would get a free makeup product upon purchasing the book every week was one of my highlights when I was a teenager. Not just that, every issue of ‘Sabrina’s Secret’s made me learn from the step-by-step tutorials on how to use the makeup given and it gave me a basic knowledge of how each product works. By playing with makeup at such a young age, it made me realise that I had an artistic talent as well as during my adolescence period, I became aware of how makeup can change one’s appearances; from making a tired person look awake and altering one’s look with just using different shades of coloured powder. Makeup made me realise that it can shape one’s perception of identity.

3.0.2 Cartoons and Animation

Being a huge fan of cartoons since I was a young child definitely has influenced why I chose cosplay as my hobby. My favourite cartoon when I was younger was Winx Club. Winx Club was about how 6 different girls attended fairy school and they had magical powers to save the world. I remembered my cousin and I making a magical staff out of newspaper with a set of wings to go with it to become my favourite fairy and it felt so surreal. As the characters in Winx Club looks fairly similar to Japanese animation, I started to take a liking towards Japanese animation (anime) and my first anime was called Tsubasa Chronicles.

Tsubasa Chronicles was a Japanese anime featuring a young girl called Sakura who lost her feathers containing her memories all around the world and her friends needed to travel all around the world to find her feathers with her as well as defeating villains along the way. Tsubasa Chronicles was one of the key animes that made me fall in love with Japanese animation because at a very young age, I was mesmerised by the beauty of animation itself. It was one of many animes that had the perfect cohesive merge of original soundtracks, character development, storyline and graphics. Looking at the character’s doe-like eyes as well as different coloured hair made me want to live in their kind of fantasy world too.

3.0.3 Living in That World

Cosplay has been around in Malaysia for almost 10 years and I’ve always found it really interesting after attending my first comic convention in Malaysia – Comic Fiesta 2009. Looking at different people dressed up in their favourite characters, wearing coloured wigs, putting on false eyelashes as well as coloured contact lenses, it gave me shivers down my spine. I remembered going up to a cosplayer to have a photo taken with them and asking some questions about their character and they replied back exactly what their characters would reply in the anime itself. Anime and cosplay have become a sense of place for me as I constantly dwell myself into this animation-fantasy-like-world. When watching anime, the cohesion of the animation, characters and soundtracks really lifts one soul to another realm; making people want to live in that world. Not just that, as I step into the convention hall, looking at cosplayers with their colourful wigs, massive props as well as having the smell of Japanese food in the air, it felt like I was back home where I belong; as if everyone was born in this world.

3.1 Identity of a Cosplayer

‘Who am I?’ A common question people ask when referring to the phrase of self-concept and self-making. Having a self-concept towards cosplay helps organise experience, focus motivation, regulate emotion and guide social interaction and the identity of a cosplayer changes when they cosplay different characters. Cosplay is a practice that takes a fictional character as a point of identification and the player literally attempts to embody that character. ‘For the pleasure is not simply in creating the costumes or even posing for photos … [t]here is also the excitement of getting into the persona of the character one admires’ (Napier, 2007: 161). Cosplayers are often seen to embrace the mannerisms, body language as well as the influence of the characters they portray when taking photographs or in cosplay conventions.

Figure 4: A side by side reference of Hiccup from How to Train Your Dragon and a cosplayer’s (Liui Aquino) attempt of the character. (SOURCE: Google, 2016)

Comparing both images above, it is interesting because the cosplayers brought out the ‘feel’ of a character; the looks, the costume and even the way the character pursed his lips. When one is cosplaying Cinderella, the cosplayer embodies herself/himself into this princess-perfect character that is graceful, beautiful and polite; when one is cosplaying Ursula, the evil sea witch from Little Mermaid, she/he will embody herself into this wicked and evil character when she cosplays. However, the embodiment does not last long, cosplayers do also have ‘out of character’ breaks when not posing in front of cameras and also interacting with other cosplayers.

Cosplayers choose which characters they prefer to be and depending on which character the cosplayer takes on, their identity changes when they are in character. When asked, ‘[h]ow does one start cosplaying?’ to imply how does one choose or create a character or an identity which they want to embody, Dova and Sally, who were both participants that were given pseudo names from my ethnographic study answered, ‘I guess one just starts to pick a character that you like’ (Dova, Interview, 2016) and ‘watch the anime, learn. Watch one that you like and you’ll relate to one character that you know what you want to get’ (Sally, Interview, 2016). Both cosplayers said that cosplay starts of by picking a character that they liked; choosing an identity that they wished to incorporate themselves with and then having a self-concept and organising their self-knowledge of this new identity about that they are going to portray.

Relating back to the earlier writings of the self-concept theory by James (1890/1950), ‘feeling good about oneself, evaluating oneself positively, feeling that one is a person of worth, have been described as a basic goal of the self-concept’ (James in Oyserman, 2004: 9). ‘[C]osplayers get very excited on how cool a character is, and they want to be like the character … [s]ome of the characters … are really cute and some are very will-powered and determined to win and all that and they look really cool with their weapons so some people would love to cosplay them’ (Sally, Interview, 2016). Every individual prefers to feel good about themselves and this process of self-concept into another identity enables them to maintain positive self-feelings about themselves. Self-concept relates to cosplay because this concept associates with one’s sense of belonging and fitting into the world. It illustrated Oyserman’s comment on Swann’s self-verification theory of saying ‘… individuals are motivated to preserve self-definitions and will do so by creating a social reality that conforms to their self-view’ (Oyserman, 2004: 9). This proves that self-concept during cosplay is a social force that shapes our reactions, perceptions and behaviours to others and through this formation of identity and the self-concept of this new identity, it defines each individual’s qualities that characterises which group that they belong to and it will be discussed below.

3.1.1 Group Identity

It is suggested that cosplay is not just an individual practice as well. For a big cosplay event like Comic Fiesta, some cosplayers will plan to debut as a cosplay group. However, debuting a cosplay group is not easy, planning would go on for months as the group leader needs to worry about making sure everyone makes their costumes and props accurately, planning where and when to meet to discuss costume details and more. Therefore Napier pointed out, ‘[p]erhaps most impressive are the group efforts, where sometimes as many as a dozen fans will dress up together as characters in their favorite series’ (2007: 161).

I started my cosplay journey with a group of friends and it gave me a sense of belonging because I felt like I was not alone. Therefore, the notion of constructing an identity through group belonging in this practice is important. With this, Dovah mentioned, ‘find someone who already is a cosplayer and guide you or make some new friends and start out together’ (Dova, Interview, 2016). Through interaction and including oneself in a group, one has created a sense of ‘place’ and it has created a sense of comfort to each individual. ‘For [Tuan], the something more to place has to do precisely with matters of dwelling or habitation, because he argues that place is constituted when locations are routinely lived-in and when what he calls a ‘habit field’ or a ‘field of care’ (1996 [1974]: 451-2)’ (Tuan, cited in Moores, 2012:27). This is because in this ‘field of care’, all cosplayers share the same interest, hobbies and goals. This illustrates Jenkins’ view on how groups ‘evoke powerful imagery of people who are in some respect(s) apparently similar to each other’ (2008: 102). Through this routine of dwelling and habitation, cosplayers developed a sense of affective attachment towards each other when cosplaying as well as concepting their own identities as a group in this ‘field of care’.

3.1.2 Online and Offline identities

It is very common to see this practice in Malaysia during cosplay events – cosplayers reuniting or meeting with other cosplayers, hugging each other, proceeding to take selfies and then exchanging Coscards. There is no specific where coscards originated from but it is a business card sized card that holds your information such as Facebook, CURE and WorldCosplay accounts as a cosplayer. Below is an example of the coscards I have received in an event back in Malaysia.

Figure 5: My coscard collection from an event. (Source: Facebook.com, 2014)

This is interesting because around 80 percent of the cards, Cosplayers used Japanese names to represent their identity on Facebook rather than using their real name. This is because cosplayers prefer to privatise their cosplay accounts from their normal accounts. When questioned about this matter, Sally replied:

‘Other people they might think like you’re a “geek” for cosplay. Basically, they’ll call you a “nerd” and what do you do with your life … They’ll just judge your life basically just because you cosplay. That’s why most cosplayers they will create 2 accounts to separate their cosplay life from their normal life’ (Sally, Interview, 2016).

‘Electronic media affect us … by changing the ‘situational geography’ of social life’ (Meyrowitz, 1985: 6). This act of routine allows them to travel back and forth from both fantasy and reality exploring their own comfort zone without even stepping out from their bedroom. When one spends more than half a day cosplaying in a convention with another and indulging as well as conversing the things they like, they develop a sense of emotional attachment to the other cosplayer. This is because the act of routine when cosplaying creates an emotional dependency with one another. ‘Space, becomes place as we get to know it better and endow it with value’’ (Tuan, cited in Moores, 2012: 28). When two cosplayers meet each other in a convention and meet each other online again, they created a sense of place; the comfort of knowing that there is another friend out there that shares the same interest and hobby as an individual. Therefore, a bond is created among these two individuals as they anticipate to see one another again online and offline.

Though Sally and I both do not have secondary cosplay accounts but initially we had one. We wanted to separate our online identities (being a cosplayer) from our offline identities (friends, family and work) because we were afraid people would judge us. Eventually, we found out the people that surround us in our offline selves were all supportive of this hobby of ours and actually appreciates cosplay as a form of art. With this, I shall continue Tuan’s ideas of emotional attachment to a ‘place’ with the next subchapter below about escapism and living in two worlds.

3.2 Escapism and Living in Two worlds

This section of this dissertation sets out to examine how cosplay is framed in terms of escapism and living in two worlds at the same time.

3.2.1 Escapism

In psychological terms, escapism means to seek entertainment or engaging in fantasy to distract or relief oneself. We are all escapists in one way or another. Some people escape reality through jogging, blogging, playing computer games, indulging themselves in music or even drinking alcohol. Susan J. Napier mentioned ‘cosplay as an activity which lets the fans escape their own identities as well’ and ‘attending conventions allow the fans to escape their mundane lives’ (2007: 161).

When talking about offline and online identities, Moores argues that ‘[i]t is therefore necessary to ask why an ‘escape’ from everyday living might be sought in the first instance, and how different online identities still relate in particular ways to offline selves’ (2012: 23). This is a very agreeable opinion from Moores because cosplayers do set up another Facebook account apart from their own social lives but I argue that they correlate in an opposing way of what the cosplayer desires to become. A cosplayer can be extrovert in a convention but an introvert in real life and a person that’s always negative in their offline selves can become really positive when they cosplay. When asked about escapism, Sally answered, ‘[A] quiet person likes this character that is hyper, friendly, confident which is totally opposite of what they are, so they are basically escaping from their true self to be that character, and no one really judges them from being that character. (Sally, Interview, 2016). When asked to further elaborate on her points, Sally answered:

‘[S]ome of them can’t deal with reality. Some of them are probably, their life is too hard and they just want to y’know and that character is a simple life character and they want to be like that character so they will enter that world of that character by cosplaying them. Because like, you can be them. And you can be that character and comfortable to be that character for a few hours during an event or a photoshoot depending where and when you cosplay’ (Sally, Interview, 2016).

Napier pointed out that there is a desire among cosplayers to become another self in relation with the convention, but reverting back to a more steady identity afterwards. As a self-reflection, I agree with Sally’s and Napier’s points. The idea of creating another identity when cosplaying is very connected to the desire of escapism. This is because I don’t need to fear how people think of me because my family and friends would not know who I am in the convention hall because I look different. When I put on a full face of makeup and then wear my costume and wig, it feels like I’ve transformed into this other character; living in two places at once. Cosplay made me step out from my comfort zone when I am cosplaying and felt a sense of belonging because I inhabit Tuan’s idea of ‘field of care’. I interact more when I am in cosplay and I get even more hyper when I embody the character I chose. Therefore, I argue that the idea of escape is not about escaping the mundane life but it is how one inhabits two worlds and those two worlds are not completely separate and it is interwoven with each other. Hence, the next section will elaborate on my point of ‘living in two worlds at once’.

3.2.2 Living in Two Worlds

‘Place is accomplished through repetitive, habitual practices … giving rise to ‘affective’ attachments in which ‘people are emotionally bound to their material environment’ (Tuan cited in Moores, 2012: 27). Anime and cosplay have become a sense of place for me as I constantly dwell myself into this animation-fantasy-like-world. As I step into the convention hall, looking at cosplayers with their colourful wigs, massive props, the sound of Japanese music and the smell of Japanese food in the air, it felt like I was back home where I belong; as if everyone was born in this world. From my autoethnographic self-reflection above, Tuan’s ideas of ‘place’ and the feeling of home and attachment were brought up and he noted that a “feel” of a place ‘[i]s a unique blend of sights, sounds, and smells, a unique harmony of natural and artificial rhythms’(1977: 183-4).

When a cosplayer frequently goes to events, they will acknowledge that an event will normally have cosplayers, photographers, Japanese merchandises and it has created ‘a spatial schemata that exceeds by far an individual can encompass through direct experience’ (Tuan, 1977: 67). Through this repeated routine and encounters, cosplayers will acknowledge the 5W’s (what, who, when, where, which) and 1H (how) of the cosplay ‘world’. For an example, what style and theme the cosplay conventions will look like, who will be there and also when it will normally take place, where the event will be held and which event is a bigger event than others as well as how to get there. Moores pointed out, ‘[t]hey may also get to know … the styles … on a regular basis’ (2012: 32). Through stylised repetition, Cosplayers will get to know the cosplay ‘world’ and understand how the community works as a whole and inhabit in it after doing the same act of routine repetitively.

Therefore, when I put on a full face of makeup and then wear my costume and wig, it feels like I’ve transformed into this other character; living in two places at once. I acknowledge there is the real world that I live in as my real self but at the same time, I am embodying this other character as another identity, inhabiting ‘two places at once’. An example to inhabiting ‘two places at once’ is when you are using the internet. Tuan (1977) noted that place exists at different scales’ (1977: 149). Noting that if a smaller formation of a place is also sitting in front of one’s computer and the person using the computer is indulging themselves in a virtual world, they are in two places at the same time. However, Kendall argues that ‘… no one ‘inhabits only cyberspace’ (2002: 8), since there are always, simultaneously ‘two … places’ in internet use’ (Kendall, cited in Moores 2012: 24). ‘When space feels thoroughly familiar to us, it has become place’ (Tuan, 1977: 73), cosplayers swing back and forth from reality and the virtual/fantasy world because a familiarity of both places and a ‘field of care’ is form. In fact, cosplayers are enlivening the grey mundane world with something that brings colour and excitement to everyday life by doing something they love. Hence, to illustrate my argument about escapism from the previous section and living in two worlds, cosplay is not a form of escape from the grey mundane world but the cosplayer inhabits two worlds at the same time and these two worlds are interwoven with each other.

4.0 Conclusion

This study has examined the adaptation of Japanese cosplay culture into Malaysian Society from the practice of identity, group identity, concepting another self, offline and online identities, escapism and attachment of place through ethnographic study, an autoethnography and online interview methods. From the results of the ethnographic study and online interview with two Malaysian cosplayers, this study was able to branch out to unanticipated subtopics that provided the evidence to back my findings. However, there are also limitations faced in this study. An over-familiarity with the topic resulted as a problem because of being too familiar with the case being worked on as an ethnographic researcher. Nevertheless, an eventual understanding for this study was achieved and it became a strength in the end.

Cosplay is not just about the colourful wigs, costumes and makeup. It is a practice of identity and self-concept or in other words, the creation of another temporary self within oneself. The development of identity and concepting a new identity defines an individual’s qualities that characterizes which group they belong to and groups elicits a powerful image of people who are similar in style, interests and values that are shared and elaborated. Cosplay groups form a sense of belonging to individual cosplayers in their ‘field of care’ and it generates an emotional attachment to the cosplayer. With that emotional attachment to a place, cosplayers generate the feeling of ‘home’ and a sense of belonging when a cosplayer gets to know a place and endow it with value through stylize repetition. As for the argument between the boundary of fantasy and reality, the idea of escape is not about escaping the mundane life but it is how a cosplayer inhabits two worlds and those two worlds are not completely separated but it is interwoven with each other. This is because when two spaces has become equally familiar to us, it has become a place where one feels at ‘home’ and Malaysian cosplayers are enlivening the real world with something that is filled with colour and excitement in everyday life. Definitely, there are still plenty of areas that are still not looked into yet such as crossplaying, gender imbalance in the cosplay community, cosplay fetish and many more and the cosplay community is vast. The results of this study has the potential to contribute to the limitation of work and research materials for the context of cosplay in Malaysia and anticipate to empower other cosplayers or fans in any subculture, to show that they are not alone and they can find a sense of belonging and ‘home’ within a group of likeminded individuals.

5.0 Bibliography

Ackerman, F. J. (1994). Through time and space with Forry Ackerman (Part 1). Mimosa, 16, 4-6.

Adams, T.E., & Holman Jones, S. (2011). Telling Stories: Reflexivity, Queer Theory, and Autoethnography. Cultural Studies ↔ Critical Methodologies, 11, 108-116.

Becker, H.S. (1971). Footnote to M.Wax and R. Wax, ‘Great tradition, little tradition and formal education’, in M. Wax, S. Diamond and F.O. Gearing(eds), Anthropological Perspectives on Education. New York: Basic Books. pp. 3-27.

Brinkmann, S. and Kvale, S. (2015). InterViews. 1st ed. Los Angeles: Sage Publications.

Coffey, A. (1999). Ethnographic Self: Fieldwork and the Representation of Identity. 1st ed. Sage Publications.

Corliss, R. (2008, December 6). Sci-fi’s no. 1 fanboy, Forrest J Ackerman, Dies at 92. Time Magazine. Retrieved from http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,1865977,00.html

Gelder, K.D. (2005). The Field of Subcultural Studies. Routledge.

Haslam, S.A., Oakes, P., Turner, J.C., & McGarty, C. (1996). Social identity, self-categorization, and the perceived homogeneity of ingroups and outgroups: The interaction between social motivation and cognition. In R. Sorrentino & E.T. Higgins (eds.), Handbook of motivation and cognition: The interpersonal context (pp. 182-222). New York: Guilford Press.

Hills, M. (2002). Fan Cultures. London: Routledge.

Gibbs, G. (2007). Analyzing qualitative data. 1st ed. Los Angeles: Sage Publications.

Gray, A. (2003). Research practice for cultural studies. 1st ed. London: SAGE.

James, W. (1950). The principles of psychology. 1st ed. [New York]: Dover Publications.

Jenkins, R. (2008). Social identity. 3rd ed. New York: Routledge.

Johnston, H. & Snow, D.A. (1998). “Subcultures and the Emergence of the Estonian Nationalist Opposition 1945-1990.” Sociological Perspectives 41(3): 473-497.

Lewis, M. (1990). Self-knowledge and social development in early life. In L. Pervin (Ed.), Handbook of personality : Theory and research. New York: Guildford Press.

Maffesoli, M. (1996). The time of the tribes: The Decline of Individualism in Mass Society. Sage Publications Ltd.

Meyrowitz, J. (1985). No sense of place. 1st ed. New York: Oxford University Press.

Moores, S. (2012). Media, place and mobility. 1st ed. London: Macmillan Education UK.

Muggleton, D. (1997). The Post-Subculturalist.‟ Pp. 167-185 in The Club Cultures Reader edited by S. Redhead, D. Wynne and J. O’Connor. Malden: Blackwell.

Nadel, S. (1951). A black Byzantium. 1st ed. London: Pub. for the International Institute of African Languages & Cultures by the Oxford University Press.

Napier, S. (2005). Anime from Akira to Princess Mononoke. 1st ed. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Napier, S. (2007). From Impressionism to anime. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Napier, S. (2016). Anime from akira to howl’s moving castle. 1st ed. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

O’Brien, C.M. (2012). The Forrest J Ackerman Oeuvre: A Comprehensive Catalog of the Fiction, Nonfiction, Poetry, Screenplays, Film Appearances, Speeches and Other Works, with a Concise Biography. Edition. McFarland.

Oliver, P. (2010). The student’s guide to research ethics. 1st ed. Maidenhead, Berkshire: Open University Press.

O’Reilly, K. (2005). Ethnographic methods. London: Routledge.

Pointon, S. “Transcultural Orgasm as Apocalypse: Urotsukidoji: The Legend of the Overfeed.” Wide Angle, vol. 19 no. 3, 1997, pp. 41-63.

Oyserman, D., 2004. Self-concept and identity. In: Brewer, M. B. and Hewstone, M., eds. 2004.

Self and social identity. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing Ltd.. Ch. 1.

Resnick, M. (2015). …Always a Fan: True Stories from a Life in Science Fiction. Wildside Press.

Roberts, Keith A. 1978. “Toward a Generic Concept of Counter-Culture.” Sociological Focus 11(2): 111-126.

Star2.com, (2015). Comic Fiesta is back, and bigger than ever – Star2.com. [online] Star2.com. Available at: http://www.star2.com/culture/books/book-news/2015/12/12/comic-fiesta-is-back-and-bigger-than-ever/ [Accessed 4 Dec. 2016].

Storey, J. (1993). An introduction guide to cultural theory and popular culture. 1st ed. Hertfordshire: Harvester Wheatsheaf.

Sparkes, A. C. (2000). Autoethnography and narratives of self: Reflections on criteria in action. Sociology of Sport Journal, 17, 21-43.

Paidi, R., Akhir, N. & Lee. P.P. (2014) Reviewing the Concept of Subculture: Japanese Cosplay in Malaysia. Universitas-Monthly Review of Philosophy and Culture, 41.

Pointon, S. “Transcultural Orgasm as Apocalypse: Urotsukidoji: The Legend of the Overfiend.” Wide Angle, vol. 19 no. 3, 1997, pp. 41-63.

Pollak, M. (2006, April 2). F.y.i.: The city weekly desk. New York Times, p. 2.

Tuan, Y. (1977). Space and place. 1st ed. Minneapolis, Minn.: University of Minnesota Press.

Tulloch, J. & Jenkins, H. (1995). Science Fiction Audiences: Watching Doctor Who and Star Trek. New York: Routledge.

Williams, J. (2011). Subcultural theory. 1st ed. Chichester: Polity Press.

Williams, R. (1983). Keywords. London: Fontana.

Winge, T. (2006). Costuming the imagination: Origins of anime and manga cosplay. In F. Lunning (Ed.), Mechademia 1: Emerging worlds of anime and manga (pp. 65-76). Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

Worchel,S. and Coutant, D. (2004). It Takes Two to Tango: Relating Group Identity to Individual Identity within the Framework of Group Development. In: Brewer, M. B. and Hewstone, M., eds. 2004. Self and social identity. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing Ltd.. Ch. 1.

Yin, R. (2009). Case study research. 4th ed. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications.

6.0 Appendices

Appendix A

Participant Information Sheet

Study Title: Adaptation of Japanese Cosplay Culture into Malaysian Society

What is the purpose of the study?

The purpose of this study is to explore how Japanese cosplay culture is adapted in the Malaysian Society. The aim of the study is to find out what does Japanese cosplay culture mean to Malaysians.

Why have I been approached?

You have been approached because you are one of a few renowned cosplayers from the Cosplay circle from Malaysia. Therefore you, who is a seasoned cosplayer is essential to further my ethnographic study.

Do I have to take part?

No. Your participation is voluntary. You can withdraw from the study at any time without giving a reason. If you have already taken part you can still withdraw up to two weeks after finishing. In this case any research materials including you will not be used in the final analysis and will be destroyed immediately. If you wish to withdraw please feel free to contact me by email on the address at the end of this information sheet.

What will happen to me if I take part?

You will take part in a one-to-one interview about your behaviour and interaction with the other Malaysian cosplayers from the cosplayer community. The conversation will be audio recorded for transcription later.

What are the possible disadvantages and risks of taking part?

Even though you will be anonymous in the report, the nature of this research means that it may still be possible for someone who knows you to identify you.

What are the possible benefits of taking part?

Your participation allows me to complete my degree programme and I will fully acknowledge your contributions without breaching the confidentiality agreement. You may also gain theoretical understanding of my research topic if you are interested in reading my dissertation.

What if something goes wrong?

If for some reason the interview cannot go ahead, I will contact you by email as soon as possible. Please let me know if you cannot attend the interview. My email address can be found at the end of this information sheet. If you have any questions or concerns about the research, you can contact my supervisor directly using the email address also found at the end of this information sheet.

Will my taking part in this study be kept confidential?

Yes. You will remain anonymous in both my notes and my dissertation. Pseudonyms will be used and places will not be identified. All research materials e.g. notes, audio recordings, interview transcripts and consent forms will be kept securely. Hard copies will be kept in a locked cupboard and computer documents will be kept on my personal computer and password protected. Only I and my supervisor will have access to them. Once my final report has been assessed all research materials will be destroyed after one year.

What will happen to the results of the research study?

The results will be used in my dissertation which will be assessed as part of my degree programme. The dissertation, or extracts from it, may later be used for teaching purposes.

Who has reviewed the study?

A departmental subcommittee of the University of Sunderland Research Ethics Committee has reviewed and approved the study.

Appendix B

| No. | Questions | Dovah | Sally | Jaymie |

| 1 | J: When did you first started off cosplay? | D: I think I’ve been cosplaying for about 4 years? Since 2012 if i remember correctly. | S: When did I start cosplaying? Uhm, when I was 15. If I’m not mistaken. | J: I started cosplaying when I was 15. |

| 2 | J: What did you remember during your first cosplay? Like what did you cosplay as? | D: I did Shiina from Angel Beats. | S: Yuuki from Vampire Knight | J: My first cosplay was Rima Touya from Vampire Knight. Rima was a shy girl who tied twintails and loved to eat Pockys |

| 3 | J: But what is your most favourite cosplay so far? | D: Ah.. I still have a very soft spot for Rena, the Grand Archer because I still super love the design. | S: Honoka Kousaka from Love Live. | J: My favourite cosplay will be Kotori Minami from Love Live. This is because Kotori has a very cheerful and bubbly personality that relate super closely to me and both of us love the same animal -Alpacas! People say I’m very much alike to her because we have the same squeaky voice and bubbly personality. |

| 4 | J: So, what do you normally cosplay as? | D: Recently I’m more into cosplay from games like League of Legends, mostly game characters. | S: What do I normally cosplay as, mostly schoolgirls or those.. I don’t usually cosplay epic ones, normally those normal school girls and school idols, the very cute ones mostly, and short haired. | J: I normally cosplay girls from the animation Love Live as well as heroes from League of Legends. I like to cosplay characters that has a personality as similar as mine, but there are also times I chose some characters that has a different personality from my usual self. |

| 5 | J: Oh my goodness! That’s great! Okay next question, have you joined any cosplay competitions these past few years? | D: Past few years? Yes. I’ve joined it when I was in 2014. I’ve joined the competition in cosmart with my cosplay partner and we won that one. After that we went to cosplay invitational and we won 3rd place. | S: I won’t say it’s a cosplay competition, more like a halloween competition. I was dressed as a female joker and I won that. But for the cosplay side, I don’t think so. Like so far no, I have joined no cosplay competition. | J: I have not joined any cosplay competitions so far. |

| 6 | J: How does one start cosplaying? | D: In my opinion? I guess one just starts to pick a character that you like and then maybe find someone who already is a cosplayer and guide you or make some new friends and start out together. | S: First, you need to know where to get it, watch the anime, learn. Watch one that you like and you’ll relate to one character that you know what you want to get. Do a lot of research. What inspires them? In my opinion, they get very excited on how cool a character is, and they want to be like the character. Especially those like.. Let’s take League of Legends for an example. That is not an anime, it’s a game. Some of the characters there are really cute and some are very will powered and determined to win and all that and they look really cool with their weapons so some people would love to cosplay them. That is one of reasons that inspires them to cosplay. | J: How does one start cosplaying? I think it starts of with the desire of wanting to be that character you want. Like, when I was younger, I would tie a cape around my neck and become superman. Taking that same concept, I feel one starts cosplaying when you don’t even know you are doing it. It’s a form of character portrayal, whether it is a towel or a cape because you are in that costume and you think you are that character itself. You like a character, you’ll do a lot of research and you’ll try to mimic that character as close as possible to deliver the best outcomes. Not just that, it also depends on the costume as well as makeup. |

| 7 | J: Do you think cosplay is a form of escapism? | D: Escapism.. Uh, in some way yes. It is nice to have something to look forward too. I’ve started working recently, like full time. So I think I really look forward into coming home to working with my costume or looking forward to the weekend I can cosplay and meet my friends and go to an event. | S: Do I think cosplay is a form of escapism? Uhm, yes. Some people would like to.. Let’s just say a quiet person likes this character that is hyper, friendly, confident which is totally opposite of what they are, so they are basically escaping from their true self to be that character, and no one really judges them from being that character. Another reason is some of them can’t deal with reality. Some of them are probably, their life is too hard and they just want to y’know and that character is a simple life character and they want to be like that character so they will enter that world of that character by cosplaying them. Because like, you can be them. And you can be that character and comfortable to be that character for a few hours during an event or a photoshoot depending where and when you cosplay. | J: I do think cosplay is a form of escapism. There are many cosplayers that are introverts and what they call as shut-ins (people who rarely go out). They don’t go out most of the time and they would just stay at home playing their computer games. However, when an event or cosplay convention arises, they will start putting on their best costume and makeup and actually go out to meet new people in their characters as well as interact with other characters. My own personal experience was cosplay actually made me step out from my comfort zone when I am cosplaying. I interact more when I am in cosplay and I get even more hyper because I feel like I have embodied the character itself. I don’t need to fear how people think of me because my family and friends would not know who I am in the convention hall because I look different. When I put on my full face of makeup and then wear my costume as well as wig, it feels like I’ve transformed into this other character and I feel like I’m living in their world, like two places at once. |

| 8 | J: What are the challenges faced in cosplay culture?

J: Do cosplayers get cyberbullied? |

D: I’ve been stalked before. It’s scary. Because at first he seems friendly and all and you are like okay. We’re just gonna talk and then he gets creepy and then you will block him. But then later on he’ll add you back on another account and then that is where it starts scary.

J: Yeap yeah. So you have been stalked before. How bout mean comments? D: Mean comments not so much. Usually if the photo gets shared on an international website, and anyone can see your photo.. They’ll say everything. J: That’s true. Normally if they see photos on Malaysian photography pages they’ll be like oh wow good photo. D: Unless when it gets onto 9gag and all the comments change. |