Knowledge and Attitudes towards Ketogenic Diets amongst Vitaflo Employees and Dietitians

Info: 12822 words (51 pages) Dissertation

Published: 16th Dec 2019

Tagged: HealthFood and Nutrition

Investigating the Knowledge and Attitudes towards Ketogenic Diets amongst Vitaflo Employees and Dietitians

Abstract

- Introduction

The ketogenic diet (KD) is a well-established, high-fat, low carbohydrate dietary treatment most frequently used in the management of epilepsies and metabolic disorders (Southern et al., 2015; Shorvon, 2010). There are currently three types of the KD used in clinical practice. The classical KD provides 80-90% of calories from long-chain triglycerides (LCTs), and is usually applied in ratios, typically consisting of a 4g : 1g ratio of fat to carbohydrate and protein combined (Lambrechts et al., 2015; Zupec-Kania and Zupanc, 2008; Magrath et al., 2000). Another common form of the KD is the medium chain triglyceride (MCT) diet. This diet utilises MCTs as the predominant source of fat, providing 60% of calories. As MCTs generate more ketones per gram than LCTs, the amount of total fat required in the diet is reduced (Southern et al., 2015). A greater proportion of carbohydrate and protein can therefore be included in the MCT diet (Sinha and Kossoff, 2005). MCTs are a form of dietary fat that are composed of only 6 to 10 carbon links. LCTs on the other hand, range from 12 to 18 carbon links and are a found in a much wider variety of foods. It is the shorter chain length of MCTs however, that prove more advantageous than LCTs (Dean and English, 2013). The third application of the KD is the modified KD, also known as the modified Atkins diet (MAD) (Vehmeijer et al., 2015). Like other forms of the diet, the MAD provides the majority of calories from fat, however protein intake is unrestricted whilst the quantity of carbohydrate in the diet is very restricted to no more than 20g per day (Southern et al., 2015).

1.1 Knowledge and Attitudes towards the Ketogenic Diet

Discovery of the KD dates back to the 1920’s when many changes were made to the delivery of dietary therapies. The classical KD was first used as a treatment option for intractable childhood epilepsy in 1921, when it was noted that the diet improved seizure control (Jung et al., 2015; Vehmeijer et al., 2015; Magrath et al., 2000). However, the KD soon became a less popular option as antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) became available. As medication was easier to prescribe and take than the KD, it was no longer used as a treatment option for epilepsy (Freeman et al., 2006; Keene, 2006; Kutscher, 2006; Vining, 1998). Despite this, almost one third of children do no achieve epilepsy remission with AEDs (Kwan and Brodie, 2000) and therefore the past 20 years has seen the KD resurface as an alternative seizure treatment option. Use of the KD has significantly risen in the UK, by 50% between 2000 and 2007 (Lord and Magrath, 2010) following the story of a two-year old boy who had been diagnosed with intractable generalised epilepsy in the US. The KD received considerable attention following a film entitled ‘First do no harm’ documenting a true case of a child with severe epilepsy that became seizure-free when treated with the KD. Following this success, the ‘Charlie Foundation’ was formed to promote, educate and aid further research of the KD by providing information about this method of treatment (Southern et al., 2015; Magrath et al., 2000; charliefoundation.org, 1994). As a result, parental awareness and interest significantly increased in the KD following the creation of the Charlie Foundation. A study conducted by Schoeler et al. (2014a) and Williams et al. (2012) assessing parents’ attitudes towards ketogenic dietary treatments, determined that parents have a positive perception of KDs and understand the need and efficacy of the diet as a treatment option. Many parents believe that the KD should be used as a first line of therapy instead of AEDs due to successful use in managing their child’s epilepsy (Williams et al., 2012). The main reported concern of many however, was the uncertainty of the long-term effects the diet could have. Despite this, Schoeler et al. (2014a) has shown that parental beliefs regarding the KD is correlated with their child’s response to the diet and that over half of participants in their study were ‘accepting’ of the diet irrespective of the potential concerns.

There are approximately 9 tertiary NHS trusts in the UK specialised in the use of the KD for epilepsy (Southern et al., 2015). Despite this, there is a lack of literature surrounding the number of patients treated with the KD in the UK. One study conducted by Magrath et al. (2000) discovered that 22 centres/dietitians use the KD, and 101 patients were being treated with it in the UK. These findings suggest the KD is commonly used in the UK, however, the small sample size (127 paediatric dietitians) used, is not representative of the number of people using the KD in the UK population today. Furthermore, there is a lack of literature regarding KDs and the knowledge and attitudes of the public, health professionals, dietitians and those working in the nutrition sector towards it. There are currently no statistics in the UK of how many people are using this specialised diet.

1.2 Use of the Ketogenic Diet

Today the use of the KD has resurfaced in a multitude of areas, in over 50 countries worldwide (Kossoff et al., 2012). It is considered the first-line therapy of choice for patients with a genetic disorder, such as glucose transporter deficiency (GLUT 1) (Vehmeijer et al., 2015; Byrne et al., 2011; Hartman and Vining, 2007); pyruvate dehydrogenase complex (PDC) deficiency (Southern et al., 2015; Shorvon, 2010) and even in some forms of mitochondrial disease (Appleton, 2011). According to Paoli et al. (2014) the KD is used in areas such as; epilepsy, diabetes, cardiovascular risk parameters, training, and weight reduction, of which there is sufficiently strong evidence behind its use. Furthermore, there appears to be emerging and upcoming evidence in the field of cancer, neurological diseases, polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS), and acne (Paoli et al., 2014).

1.2.1 Epilepsy in Children

Epilepsy is a condition that affects the brain (Epilepsy Action, 2017), it is the second most common neurological condition resulting from problems in the central nervous system and causes individuals with the condition to have seizures. It is not an illness nor a disease, but a symptom of an underlying problem with brain function (Johnson and Parkinson, 2002). The onset of epilepsy can occur at any age, and there are approximately 40 different types, of which an individual may have more than one. Some forms may last for a limited time and eventually seizures will stop, however, for many people epilepsy is a life-long condition (Epilepsy Action, 2017). Epilepsy affects approximately 50 million people worldwide, of which 600,000 suffer in the UK alone (WHO, 2017). Despite the development of AEDs, in approximately 20-30% of patients’ epilepsy remains refractory (Mohanraj and Brodie, 2013). Refractory epilepsy is defined by inadequate control of seizures despite treatment with at least two AEDs (Brodie, 2011). Ketogenic dietary therapy is seen as a last resort in the treatment of children with drug-resistant epilepsy, even in clinical practice. Despite this, research suggests that the use of the KD can be effective for up to 50% of children, with 20-30% of children experiencing a greater than 90% reduction in seizures (Southern et al., 2015; Appleton, 2011).

The exact mechanisms of how and why the KD controls refractory epilepsy are unknown; however, research is ongoing, and a number of theories exist. When the KD was first discovered, Woodyatt (1921) and Wilder (1921) theorised that the diet would induce a state of ketosis and in turn improve seizure control in epilepsy. According to Bender (2014) ketosis occurs when there is an increased concentration of ketone bodies; acetoacetate, beta ()-hydroxybutyrate and acetone, in the bloodstream. The KD is thought to mimic the biochemical response to starvation, resulting in a change from aerobic to ketogenic metabolism and the production of ketones in the liver (Vehmeijeret al., 2015; Frayn, 2013; Shorvon, 2010). This change forces the body to utilise ketone bodies instead of glucose as its main energy source (Plogsted, 2010). Ketones are transported by monocarboxylic acid transporters where they can successfully cross the blood-brain barrier and provide up to 60% of the energy source (Southern et al., 2015; Shorvon, 2010). Energy is therefore derived from fatty acid oxidation to meet metabolic needs through the production of acetyl CoA, a substrate involved in the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle (Gropper and Smith, 2012). The oxidation of fatty acids is largely fulfilled by the liver due to limited fatty acid oxidation in the muscle tissues (Bender, 2014). Hence, it is this accumulation of acetyl CoA that leads to an increase in ketone body formation, resulting in ketosis (Gropper and Smith, 2012). Today, other researchers have devised similar theories. Runyon and So (2012) discovered that ketones produce an anticonvulsant effect when they cross the blood-brain barrier, and Cunnane et al. (2002) theorised that it could be the direct inhibitory actions of fatty acids that produce these effects. Other theories explaining the anticonvulsant effect of the KD include changes in brain pH, changes in electrolyte and water balance (Freeman et al.,2006); neurotransmitter alternations (Szot et al., 2001; Yudkoff et al., 2001; Klepper et al., 2002); and changes in energy metabolism (Pan et al., 1999; Freeman et al., 2006).

In 2008, the first randomised control trial was carried out by Neal et al. (2008) reviewing the use of the KD for children who had no success controlling their epilepsy with at least two AEDs. The study compared the efficacy and tolerability of the classical and MCT KD diet and demonstrated that the classical KD did not have any advantages over the MCT diet with regards to efficacy and tolerability. Furthermore, Southern et al. (2015) discovered that the use of the MAD or MCT diets had a positive effect for older children and young adults as they are less restrictive. The results clearly demonstrated that the use of the KD could be equally as beneficial as medication. It has been suggested that ketogenic dietary therapy can improve seizure control from as little as a few days to a week from initiation (Kustcher, 2006; Kossoff, 2005). A study conducted by Vehmeijer et al. (2015) evaluating the efficacy of the KD treatment found that 49% of participants achieved a 50% or greater reduction in seizures within 3 months; and these results are consistent with various other studies; particularly that of Neal and Cross (2010) showing an efficacy rate between 27-62% at three months after the diet initiation. Studies also suggest that by six months, 50% of patients will have a 50% or greater reduction in seizures (Kutscher, 2006; Kossoff, 2005); and of these children with such a response, half again will have a greater than 90% response (Kutscher, 2006). A study conducted by John Hopkins University indicated that by 12 months of diet initiation, despite the smaller participation, half of the children were still maintaining a 50% reduction in seizures, this was also consistent with findings by Levy et al. (2012) and Vehmeijer et al. (2015); and by three to six years, 44% of participants had still maintained the improvement (Shorvon, 2005). Complete seizure control is achieved by approximately 10% of children on the diet (Kossoff et al., 2005; Vining, 1998). It was therefore concluded by Vehmeijer et al. (2015) that a three-month period of KD treatment is a statistically proven trial period and can be used as a predictor of efficacy once on the KD.

Over recent years, various clinical studies have been carried out to assess the efficacy of the KD when it is initiated at an earlier stage. According to Plogsted (2010), initiating the KD at an earlier stage could have a greater impact on the development and lifestyle outcomes for the patient (Carabello and Fejerman, 2006). During infancy, seizures can affect psychomotor development and thus, children with a higher seizure burden, further neurological decline is predicted (Payne et al., 2014). It is for this reason that early seizure freedom is a primary aim of seizure control (Dressler et al., 2015). The recommended introduction of the KD is only after the failure of two AEDs, and this also applies to infants (Kossoff et al., 2009); however, a study conducted by Dressler et al. (2015) evaluating the efficacy of the KD in infants below 1.5 years, found that efficacy was significantly higher in fluid-fed infants than solid-fed children. Findings demonstrated that more infants became seizure free with a 90% or greater reduction (59%) compared to older children (27%). Results indicated that starting the KD earlier during the course of epilepsy had a significantly higher rate of seizure freedom and that the KD is both a safe and effective treatment for infants with epilepsy, and it should be considered earlier during the course of epilepsy rather than a last resort (Dressler et al., 2015).

The first step in implementing the KD is to see a dietitian experienced in its use. The dietitian will determine the suitability of the treatment, assess the patient’s ability to comply with the restricted diet, and chose the best diet for them (Southern et al., 2015). A fast may be initiated to promote ketosis in some patients; however, it is not necessary to induce and maintain a condition of metabolic ketosis (Freeman et al., 2006; Klepper et al., 2002). Fasting must be considered as it can induce a shorter time onset of ketosis, improving screening conditions for identifying underlying metabolic disorders, however, there is a risk of hypoglycaemia or dehydration (Kossoff et al., 2005; Kossoff and McGrogan, 2005). Once the patient’s suitability for the diet has been established and ketones are present, the diet is started and the dietitian will calculate, monitor, and fine-tune the diet throughout the treatment (Southern et al., 2015). Patients will then be required to monitor ketones twice per day to minimise complications (Melchoir et al., 2015; Southern et al., 2015); through the testing of urinary and occasionally, blood ketones (Appleton, 2011; Hartman and Vining, 2007). This will help dietitians assess compliance to the diet.

Not surprisingly, the KD can be difficult for many children to comply to and thus, the importance of clinical supervision is apparent. The major reasons many children stop the diet are due to; poor dietary compliance such as restrictiveness of the diet or unacceptability of ketogenic food (Dressler et al., 2015; Lambrechts et al., 2015; Magrath et al., 2000); lack of efficacy in controlling seizures (Lambrechts et al., 2015; Vehmeijer et al., 2015); food refusal or noncompliance by caregivers (Dressler et al., 2015); and patient suffering from adverse effects (Dressler et al., 2015; Lambrechts et al., 2015; Vehmeijer et al., 2015). The KD is not a natural diet and therefore has, like many other treatments, side effects. Side effects differ from patient to patient, but most commonly they may suffer from nausea (southern et al., 2015); vomiting (Lambrechts et al., 2015; Appleton, 2011; Shorvon, 2005); constipation (Lambrechts et al., 2015; Appleton, 2011; Kutscher, 2006; Shorvon, 2005); abdominal pain (Lambrechts et al., 2015; Appleton, 2011); cardiomyopathy (Appleton, 2011; Kutscher, 2006); poor growth (Appleton, 2011; Shorvon, 2005; Kutscher, 2006) alteration in cholesterol, triglyceride and lipid levels (Kutscher, 2006); and acidosis (Shorvon, 2005).

1.2.2 Epilepsy in Adults

Whilst approximately 40-67% of children experience a 50% or greater reduction in seizure frequency (Schoeler et al., 2014b; Lefevre and Aronson, 2000); there is very limited data available surrounding the efficacy of the KD in adults (Lambrechts et al., 2012; Payne et al., 2011; Klein et al., 2010). However, increasing use of the KD has been acknowledged, not only in adults who have transferred from paediatric services but also those who are starting the KD for the first time (Cervenka et al., 2013). Despite issues with compliance (Rho, 2015), the less restrictive MAD is thought to be of value to older individuals, although the classical KD has also been a popular choice for many adults (Rho, 2015; Southern et al., 2015; Kossoff, 2009). Although infants have the ability to metabolise ketones six times more compared to adults (Dressler et al., 2015); a study conducted by Nei et al. (2014) suggests that the KD can also be beneficial for adults with epilepsy. This study, assessing the long-term outcome of the KD in adults, determined that, out of 29 patients, 45% had a 50% or greater reduction in seizures, with 21% experiencing an 80% or greater seizure reduction (Nei et al., 2014). Similarly, a study conducted by Schoeler and colleagues (2014b) discovered that 39% of adults achieved 50% or greater reduction of seizures, of which 2 individuals achieved a 90% or greater reduction. Approximately half of adults in these studies had a significant reduction in seizure frequency. Furthermore, it was established that a positive short-term response to the KD was predictive of long-term seizure control (Nei et al., 2014). Findings therefore suggest that the KD is an effective dietary treatment in this age group and is a worthy consideration for adults with epilepsy.

1.2.3 Diabetes

Diabetes mellitus is a serious health problem affecting over 200 million people worldwide (Al-Khalifa et al., 2011). It is characterised by defects in insulin secretion or insulin action, resulting in hyperglycaemia; and due to changes in lifestyle and dietary habits, alongside genetic susceptibility, the prevalence of DM is rapidly increasing worldwide (Al-Khalifa et al., 2009). Type 1 diabetes is caused by the autoimmune destruction of pancreatic cells causing insulin deficiency; and it accounts for approximately 5-10% of all diabetic cases (Sparre et al., 2005). On the other hand, type 2 diabetes is due to impaired insulin secretion or insulin resistance; and is more common accounting for 90-95% of diabetic cases (Malecki, 2004). Maintaining blood glucose levels is therefore at the forefront for diabetes management; as adopting the right dietary habits can have positive impact on stabilising blood glucose levels (Al-Khalifa et al., 2009). Despite the vast array of drugs available for diabetes management, there is still no effective therapy available for its cure (Al-Khalifa et al., 2011; Pari and Satheesh, 2004); however, it has been shown that a very low carbohydrate, or ketogenic diet, can be an effective treatment in diabetes management (Al-Khalifa et al., 2011). Carbohydrates are absorbed as glucose, resulting in an immediate rise in blood glucose; therefore the KD, providing energy from triglycerides and proteins rather than glucose, would alleviate this factor in diabetes (Al-Khalifa et al., 2009). The KD appears to improve glycaemic control in diabetics and reduces the need for exogenous insulin (Dressler et al., 2010; Arora and McFarlane, 2005). It has also been found to improve insulin sensitivity by up to 75% (Kirk et al., 2008; Boden et al., 2005).

Despite the limited data surrounding the efficacy of the KD in diabetes management, data suggests short-term use can improve; weight loss (Goday et al., 2016; Dressler et al., 2010; Malandrucco et al., 2012; Al-Khalifa et al., 2009); glycaemic control (Wheeler et al., 2012; Dressler at al., 2010; Al-Khalifa et al., 2009); lipid and plasma glucose profiles (Goday et al., 2016); and cell function (Malandrucco et al., 2012). Beneficial effects of the diet have also been shown in low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol, triglycerides, total cholesterol and urea (Al-Khalifa et al., 2011; Dashti et al., 2007; Kirk et al., 2008). Similar results were recognised in studies conducted by Goday et al. (2016), Al-Khalifa et al. (2011), and Al-Khalifa et al. (2009) investigating the efficacy of the KD in the management of diabetes. These studies used Streptozotocin (STZ), a chemical agent commonly used to alter cell function, to mimic the response of diabetes in rats. Over a six-week period the rats on the KD showed a greater resistance to diabetogenic action of STZ (Al-Khalifa et al., 2011; Al-Khalifa et al., 2009); as blood glucose levels remained within the normal range off 100 mg/dL compared to the rats fed on normal feed and high carbohydrate feeds. Based on these findings, Al-Khalifa et al. (2011) suggests that the KD, specifically ketones bodies act to prevent diabetogenic effects of STZ by stabilising blood glucose levels which could result in improved cell function (Al-Khalifa et al., 2009). Furthermore, a study carried out by Goday et al. (2016) demonstrates the short-term safety, tolerability and efficacy of the KD in patients with diabetes; therefore the KD may be effective not only by improving glycaemia, but also for reducing the need for medication in patients with diabetes (Al-Khalifa et al., 2009). However, further research is required to understand the underlying cellular mechanisms of why the KD has such an effect on glycaemic control.

1.2.4 Cardiovascular Risk Markers

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the leading cause of global mortality (WHO, 2016); and is caused by a range of risk factors including hypertension, high cholesterol, obesity, physical inactivity and diabetes (World Health Federation, 2017). Dietary habits are known to have a strong influence on the myriad of CVD risk factors (Sharman et al., 2002); more specifically, use of the KD has been shown to be an effective diet in the short term to tackle obesity, hyperlipidaemia, and some cardiovascular risk factors (Paoli et al., 2011; Al-Khalifa et al., 2009). However, despite the popularity of KDs, very few scientific studies have evaluated how the diet affects CVD risk factors (Sharman et al., 2002); and of the studies available, findings are notably controversial (Bertoli et al., 2015).

Findings from previous studies have shown that the KD has favourable effects on serum biomarkers for CVD in those with epilepsy and GLUT 1 deficiency, and normal-weight, healthy individuals (Coppola et al., 2014; Schoeler et al., 2014; Paoli et al., 2011; Sharman et al., 2002). Results demonstrate that the KD leads to reductions in fasting triglycerides (Schoeler et al., 2014; Paoli et al., 2011; Sharman et al., 2002); and fasting insulin concentrations (Sharman et al., 2002); reduction of low density lipoprotein (LDL) and total cholesterol (SchoVolekeler et al., 2014; Paoli et al., 2011); and increases in high density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol (Paoli et al., 2011). Furthermore, the KD can cause modification in LDL cholesterol particles, shifting small, dense LDL to larger, buoyant LDL, which may reduce cardiovascular risk since smaller LDL particles have been shown to be more atherogenic (Coppola et al., 2014; Paoli et al., 2011). Collectively, the changes in serum lipid subclasses and insulin in response to the KD, are beneficial in terms of overall CVD risk profile (Sharman et al., 2002). Controversially, numerous studies have suggested that the KD can have an adverse effect on these CVD risk factors. Previous clinical studies have suggested that the KD produces a significant increase in triglyceride levels and LDL cholesterol, reduced HDL cholesterol, and the creation of small, dense LDL particles (Bertoli et al., 2015; Coppola et al., 2014; Kapetanakis et al., 2014; Kwiterovich et al., 2003); a combination of which, alongside insulin resistance, has been termed Metabolic Syndrome (MS) or Syndrome X. Approximately 30% of adult males and 10-15% of postmenopausal women have MS; which is associated with an increased risk of heart disease (Sharman et al., 2002). A study conducted by Raitakari et al. (2004) found a positive relationship between the KD in paediatric patients and an increased thickness of the intima and media layers of the arterial vessels in adult age. Therefore, exposure to these CVD risk factors in early life may induce changes in arteries contributing to the development of atheroscelerosis (Coppola et al., 2014). Furthermore Kapetanakis et al. (2014) determined that the KD can increase the concentration of cholesterol, lipids and lipoprotein levels, as well as the number and composition of both LDL and HDL in plasma. Generally, studies investigating the short-term effects of the KD demonstrate that it can have a positive effect on various CVD risk markers. In contrast, findings from long-term studies differ considerably suggesting that the diet can have an adverse effect on these risk markers, thereby increasing atherogenesis and the risk of developing CVD. More research is therefore required in larger cohorts, over a longer time period to clarify the actual impact that the KD has on overall CVD risk profile, and to determine if these benefits are merely short-term or if the KD can improve long-term vascular function.

1.2.5 Obesity and Weight Loss

The increasing prevalence of overweight and obesity is rising globally (PHE, 2017); and as a result, the KD has received various attention as a means of rapid weight loss (Sumithran and Proietto, 2008). Whilst the KD is often limited to diets containing under 50g of carbohydrate per day (Adam-Perrot et al., 2006); the KD used for weight loss does not have fixed macronutrient ratios, nor does it aim to generate high ketone levels; instead, carbohydrates are limited strictly for weight loss purposes (Sumithran and Proietto, 2008). The KD is frequently cited in the literature and promoted in the lay press as supressing appetite (Gibson et al., 2014); however, there is conflicting evidence surrounding the efficacy of the KD in supressing appetite and thus, aiding weight loss (Sumithran and Proietto, 2008).

Findings from previous studies comparing the KD and a low-fat diet, have demonstrated that those on the KD experienced a greater weight loss (Goday et al., 2016; Yancy et al., 2004; Bravata et al., 2003; Brehm et al., 2003); were significantly less hungry, and exhibited significantly greater satiety (Gibson et al., 2014). Bravata et al. (2003) found that over a period of 50 days, the mean weight loss of those following a KD was approximately 16.9kg, compared to only 1.9kg weight loss in the high-carbohydrate diet group. However, these studies were carried out over a short time period, and of the studies available evaluating the efficacy of the KD for 12 months or more, the results are comparably different. Whilst weight loss was seen at three to six months on the KD, studies conducted for 12 months or more, displayed no significant difference in mean weight seen at 12 months (Sumithran and Proietto, 2008; Johnston et al., 2006; Nordmann et al., 2006).

There are several existing theories as to how the KD may contribute to weight loss. Most commonly it has been hypothesised that initial weight loss is caused by diuresis (Al-Khalifa et al., 2011) as a result of glycogen depletion and ketonuria, thereby increasing renal sodium and water loss (Denke, 2001). Other suggested mechanisms of the KD include supressed appetite (Sumithran and Proietto, 2008; Astrup et al., 2004); limited food choice (Astrup et al., 2004; Brehm et al., 2003); reduced palatability of the diet (Erlanson-Albertson and Mei, 2005); increased satiety due to high protein intake (Erlanson-Albertson and Mei, 2005; Astrup et al., 2004); increased fatty acid oxidation (Erlanson-Albertson and Mei, 2005); and increased adipose tissue lipolysis as a result of reduced circulating insulin levels (Volek and Sharman, 2004).

Based on the literature, findings suggest that the KD can aid weight loss at three to six months, however at 12 months the diet appears to have little effect on weight. Studies have reported a variety of results including an increase, no change, or a decrease in appetite whilst adhering to the KD (Gibson et al., 2014; Sumithran et al., 2013; Boden et al., 2005; Kamphuis et al., 2003). Thus, there is a need for further investigation and stronger evidence in order to conclusively determine if the KD does supress appetite and if it can be used as an effective method of weight loss.

Rationale

The KD has been used to treat and manage refractory childhood epilepsy for almost a century (Southern et al., 2015; Vehmeijer et al., 2015; Magrath et al., 2000). Despite its decreased use after the development of antiepileptic medications, the past 20 years has seen the KD re-emerge in a myriad of areas (Southern et al., 2015; Keene, 2006; Kutscher, 2006). Various research has been conducted surrounding the efficacy of the KD; particularly in childhood epilepsy, however, despite increased awareness of the diet, very few studies exist that investigate the knowledge and awareness, or opinions of the KD. Moreover, of the limited literature that is available, studies primarily focus on parental beliefs, and the attitudes of physicians, not on individuals in the field of nutrition who administer and specialise in ketogenic dietary treatment. Furthermore, research conducted by Jung et al. (2015) discovered that as the KD is quite a restrictive diet, and therefore, cooperation from the patient and an appropriately trained dietitian is vital. Despite this, various studies exploring diet initiation, uncovered that the lack of adequately trained dietitians was the most common determinant of KD use, even though they are fundamental to the successful implementation and maintenance of the diet (Jung et al., 2015; Hemingway et al., 2001). Based on this, a hypothesis was formulated that dietitians would have a lesser knowledge of the KD and differing attitudes towards it, in comparison to that of Vitaflo employees. Therefore, this study set out to investigate the knowledge and attitudes towards the KD in the field of nutrition and dietetics.

2 Aims and Objectives

2.1 Aim

The aim of this study was to explore the knowledge and attitudes towards ketogenic diets in the field of nutrition and dietetics

2.2 Objectives

- To investigate the knowledge and awareness of ketogenic diets amongst Vitaflo employees and dietitians

- To assess the attitudes towards ketogenic diets and determine if occupation has an impact on the perception of ketogenic diets

- To examine the relationship between knowledge of ketogenic diets and how this effects attitudes towards the diet

- Methodology

3.1 Study Design

The study was conducted over a six-week period from 9th January until the 20th February 2017, targeting Vitaflo employees in Liverpool and Dietitians in Belfast. Data were collected using a quantitative sampling method. There are three distinct approaches to research; quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methods (Almalki, 2016; Flick, 2015). Quantitative research is often referred to as a deductive approach (Rovai et al., 2014) as the researcher must quantify participant responses and interpret them to make decisions. Generally, quantitative studies aim to test a previously formulated hypothesis based on the research findings, and generalise these findings on a larger population by conducting analysis using the relevant statistical tools (Almalki, 2016; Flick, 2015; Smith, 2014; Arghode, 2012). To date various method such as observational studies, retrospective studies, and medical record reviews have been used to measure the use, efficacy and knowledge of the KD. However, it was decided that an internet survey was the best method to adopt for this investigation due to its successful use in studies conducted by Jung et al. (2015); Schoeler et al. (2014); Hemingway et al. (2001); and Magrath et al. (2000). The use of an online questionnaire is one of the more practical ways of contacting participants and gaining a larger response rate; it also ensures that participant anonymity is maintained, thus, this quantitative approach was deemed the most appropriate method of data collection in this investigation.

3.1.1 Participants

This study was aimed at an opportunistic random sample of participants at Vitaflo in Liverpool, and at dietitians with varying specialisations in Belfast. These participants were chosen in the hope of gaining various views and insights on the knowledge and attitudes of ketogenic diets from two comparably different job roles. Vitaflo is a leading clinical nutrition company that operates on a global level developing specialised clinical nutrition products for Metabolic Disorders, Ketogenic Diets, Renal Diseases and Diseases Related Malnutrition (Nestle Health Science, 2017). Therefore, staff at Vitaflo were the chosen participants for this study as it was presumed that they would have a substantial level of knowledge surrounding the KD and could thus, provide accurate and insightful information. The dietitians chosen to participate in this investigation were specialised in an array of areas in various hospitals in Belfast.

A small sample size of 20 participants was chosen for both means of data collection from Vitaflo employees and dietitians due to the expected difficulty of obtaining information from these professions. Based on studies such as those carried out by Magrath et al. (2000) and Jung et al. (2015), a small sample size was chosen and a limited response rate was hypothesised due to previous responses gained from dietitians and those in the nutrition industry.

3.2 Sampling Techniques & Data Collection

The sampling method used in this study involved the use of convenience sampling as it is a non-probability sampling technique (O’Leary, 2010) in which participants are sampled because they provide a convenient source of data for the researcher (Lavrakas, 2008). The initial recruitment process involved the use of inclusion and exclusion criteria to elect the study sample. Eligible staff were those who met the criteria of working for Vitaflo or working as a dietitian. Staff at Vitaflo were contacted through a gatekeeper letter sent to the manager at Vitaflo (see Appendix 1).

Data were collected using both primary and secondary means of research. The primary research involved the use of a quantitative questionnaire (see Appendix 2), and the secondary research comprised of data collected from various journal articles and academic websites. Once ethical approval was gained, the primary research could be carried out. A pilot questionnaire was firstly tested on family and friends to gain feedback and identify any problems with the questionnaire. Appropriate changes were then made to the questionnaire layout and to one of the questions following feedback. The questionnaire was composed of 12 tick-box style questions and 6 open-ended questions. A range of open and closed questions were chosen to allow for appropriate quantitative analysis using a software, whilst open-ended questions also allowed for a wider spectrum of opinions, attitudes and knowledge to be assessed. Having gained permission to involve Vitaflo employees in the study, the online link was sent to the manager who forwarded the link onto other members of staff. Over a six-week period, the internet survey was disseminated via SurveyMonkey to the dietitians and staff at Vitaflo to be completed in their own time. Questionnaires were returned, again, through SurveyMonkey to ensure that participants were kept anonymous. An online questionnaire was deemed the most appropriate method of data collection as response rate was predicted to be low and thus, it was easier to distribute and contact participants via email rather than delivering questionnaires by hand, or arranging a time-consuming interview or focus group. This therefore cut down on contact time and allowed for a larger number of participants to be reached.

Despite the predetermined sample size of 20 participants, only 19 responses were gained with a response rate of 95%. The ‘dropout rate’ is a common occurrence in research and it refers to those individuals who drop out of the study (National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute, 2014). Of the 19 questionnaires returned, 8 responses were gained from the employees at Vitaflo and 11 responses were gained from the dietitians in Belfast. Once all the questionnaires were completed and returned they were analysed.

3.3 Data analysis

Once all the questionnaires were completed and returned, the data were analysed using both Microsoft Excel 2016 and SPSS23 (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences). SPSS was used as it allows for various relationships to be made between variables such as the comparison between the knowledge and attitudes of dietitians and Vitaflo employees. Before analysing the data, open-ended questions were coded through the process of content analysis, by which the main themes were identified from the responses given by participants (Kumar, 2014). The content could therefore be divided into sub-categories in order to determine; patterns and trends, or frequency of the language used throughout the responses gained. This content was then ‘quantified’ by converting it into a numeric form before inputting the data into SPSS. Once inputted, data was analysed with the use of bivariate methods such as cross tabulations to assess the relationships between an array of variables. Independent t-tests were applied to determine if there was a statistically significant difference between the means in two unrelated populations. A chi-squared test was also used to explore correlations between familiarity of the KD and occupation. The significance level was set at p <0.05. 95% confidence level??

4 Results

4.1 Demographic Characteristics

Table 1: Demographic characteristics of participants (n=19)

| Demographic Characteristics | Number of participants (n) | Percentage (%) |

| Age:

18-29 30-49 50+ |

5

10 4 |

26.32

52.63 21.05 |

| Occupation/Employment:

Dietitian Vitaflo Employee |

11

8 |

57.89

42.11 |

| Time at Job:

0-11 months 1-2 years 3-4 years 5+ years |

1

6 6 6 |

5.26

31.58 31.58 31.58 |

Of the 19 participants who were involved in the study, 52.63% were aged between 30-49 years, whilst over half (57.89%) were dietitians, as seen in Table 1.

4.2 Knowledge and awareness of the KD

Table 2: Familiarity with the KD amongst participants (n=19)

| Demographic Characteristics | Familiarity1,2 | ||

| Very Familiar | Familiar | Unfamiliar | |

| Percentage (%) | |||

| Age:

18-29 30-49 50+ |

20

20 0 |

40

40 50 |

40

40 50 |

| Occupation1,2:

Dietitian Vitaflo Employee |

0

37.5 |

27.3

62.5 |

72.7

0 |

1 Occupation vs. Familiarity (p=0.004)

2 Mean difference between Occupation vs. Familiarity (p=0.000)

Table 2 illustrates the familiarity of participants with the KD in relation to the demographic characteristics; age and occupation. Participants in the age groups 18-29 and 30-49 years, were more familiar (60%) with the KD than those aged 50+ (50%); 100% Vitaflo employees were either familiar or very familiar with the KD. In comparison, majority of dietitians (72.7%) were unfamiliar with the diet. A chi-square analysis revealed a significant relationship between occupation and familiarity (p=0.004). Moreover, using an independent t-test, a significant difference (p=0.000) was also observed.

4.2.1 Knowledge of Participants who are Familiar with the KD

Table 3: Participants experiences with the KD (n=11)

| Demographic characteristics | Knowledge of the KD | Experience with the KD3 | Outcome4 | |||||||

| H1 | S1 | R1 | P1 | W1 | Positive | Negative | E2 | C2 | T2 | |

| Percentage (%) | ||||||||||

| Occupation3,4:

Dietitian Vitaflo Employee |

33.3

37.5 |

66.7

75 |

33.3

50 |

0

0 |

0

37.5 |

33.3

100 |

66.7

0 |

0

26.3 |

18.2

12.5 |

0

12.5 |

1 H: Heard of it S: Studied it R: Read about it P: Personally been on it W: Worked with someone on it

2 E: Epilepsy C: Compliance T: Therapeutic effect

3 Occupation vs. Experience with the KD (p=0.011)

4 Occupation vs. Outcome of Experience with the KD (p=0.006)

The majority of respondents; both dietitians (66.7%) and Vitaflo employees (75%); knowledge was gained from studying the KD. Whilst all Vitaflo employees (100%) reported having positive experiences with the KD, dietitians reported negative experiences (66.7%) with the diet. Using a chi-square test, a significant relationship between occupation and experiences associated with the KD (p=0.011) was determined. Of the 19 participants who reported their experience with the KD, only 9 explained the outcome of such experience. The reported experiences with the KD included a positive effect on childhood epilepsy as stated by 26.3% of Vitaflo employees; negative effects due to compliance issues reported by 18.2% of dietitians and 12.5% of Vitaflo employees; and finally, the KD offering positive therapeutic effects stated by 12.5% of Vitaflo employees. Based on a chi-square test analysis, it was observed that there was a significance of p=0.006 between the two variables at a 5% significant level.

Table 4: Participants opinions of the KD (n=11)

| Demographic Characteristics | Opinions of the KD1,2 | |||

| Epilepsy | Compliance | Specific Population | ||

| Percentage (%) | ||||

| Occupation1,2:

Dietitian Vitaflo Employee |

0

87.5 |

66.7

0 |

33.3

12.5 |

|

1 Occupation vs. Opinion of KD (p=0.014)

2 Mean difference between Occupation vs. Opinion of KD (p=0.043)

Of the 11 participants, 87.5% of Vitaflo employees gave the opinion that the KD has beneficial effects in the management of epilepsy; 12.5% specified that it should only be recommended for a specific population of individuals. In comparison, all dietitians gave negative opinions of the KD; that it can be difficult for an individual to comply to and that the diet should only be applied to a specific population. Based on a chi-square test analysis, a significance relationship (p=0.014) was determined. Moreover, a significant difference (p=0.043) between the two variables was also observed.

4.2.2 Understanding of the KD

Table 5: Participants ability to identify components of the KD (n=19)

| Demographic Characteristics | Components of the KD | ||||||||||

| HP1 | HF1 | HC1 | AP1 | AF1 | AC1 | LP1 | LF1 | LC1 | |||

| Percentage (%) | |||||||||||

| Age:

18-29 30-49 50+ |

20

30 25 |

100

80 75 |

0

0 25 |

60

50 50 |

0

0 0 |

0

0 0 |

40

10 25 |

0

10 25 |

100

90 25 |

||

| Occupation:

Dietitian Vitaflo Employee |

45.5

0 |

72.7

100 |

9.1

0 |

18.2

100 |

0

0 |

0

0 |

0

0 |

18.2

0 |

63.6

100 |

||

1 HP: High Protein HF: High Fat HC: High Carbohydrate AP: Adequate Protein AF: Adequate Fat AC: Adequate Carbohydrate LP: Low Protein LF: Low Fat LC: Low Carbohydrate

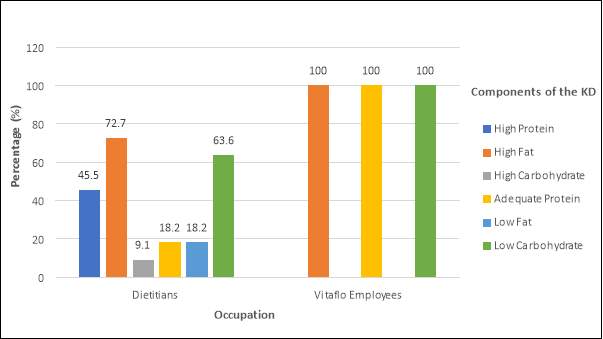

Participants aged between 18-29 years had a greater ability to identify the components of the KD; identifying the diet as being high in fat (100%); adequate in protein (60%); and low in carbohydrates (100%), in comparison to those in other age groups. All Vitaflo employees were able to identify the correct components of the KD; however, a fewer amount of dietitians determined the KD to be high fat (72.7%) and low carbohydrate (63.3%). Furthermore, the majority of dietitians believe the KD is high protein (45.5%) in comparison to only 18.2% recognising it as an adequate amount of protein. This is more clearly illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Ability to identify components of the KD amongst participants (n=19)

Table 6: Participants ability to identify what conditions/individuals benefit from the KD (n=19)

| Demographic Characteristics | Conditions/Individuals benefitting from the KD | ||||||||

| O1 | D1 | C1 | HC1 | EC1 | EA1 | M1 | CVD1 | ||

| Percentage (%) | |||||||||

| Occupation:

Dietitian Vitaflo Employee |

9.1

25 |

0

12.5 |

0

75 |

18.2

0 |

81.8

100 |

63.6

87.5 |

0

0 |

0

12.5 |

|

1 O: Obesity D: Diabetes C: Cancer HC: Heart Conditions EC: Epilepsy in Children EA: Epilepsy in Adults

M: Malnourished CVD: Cardiovascular Disease

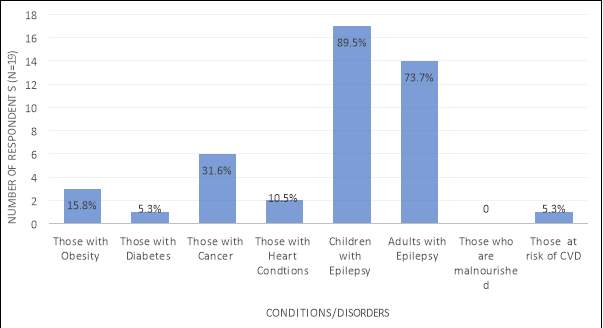

Epilepsy in children was recognised as the condition most benefitting from use of the KD; with 100% of Vitaflo employees acknowledging this and 81.8% of dietitians. Despite a larger number of participants from Vitaflo recognising these conditions in comparison to dietitians, both occupations recognised that KD can benefit individuals who are overweight or obese, and children and adults with epilepsy. Dietitians failed to recognise diabetes, cancer and CVD however, as benefitting from the KD. In comparison, 18.2% of dietitians incorrectly selected individuals with heart conditions. These results are more clearly illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Conditions identified by participants that benefit from the KD (n=19)

4.2 Attitude and Opinions of the KD

Table 7: Participants attitudes towards the KD, whether it can be beneficial and why (n=19)

| Demographic characteristics | Attitudes towards the benefits of the KD3,4 | Why? | ||||||||||

| SA1 | A1 | U1 | D1 | SD1 | E2 | M2 | U2 | |||||

| Percentage (%) | ||||||||||||

| Occupation3,4:

Dietitian Vitaflo Employee |

0

62.5 |

18.2

37.5 |

72.7

0 |

9.1

0 |

0

0 |

40

57.1 |

20

42.9 |

40

0 |

||||

1 SA: Strongly Agree A: Agree U: Undecided D: Disagree SD: Strongly Disagree

2 E: Epilepsy management M: Management of medical conditions U: Unsure

3 Occupation vs. attitude towards the KD (p=0.003)

4 Mean difference between Occupation vs. attitude towards the KD (p=0.000)

The majority of dietitians were unsure (72.7%) of the benefits of the KD compared to all participants from Vitaflo either strongly agree (62.5%) or agree (37.5%) that the KD can have beneficial effects. Having conducted a chi-square test analysis, a significance relationship (p=0.003) was observed between these two variables. An independent t-test was also used to evaluate the relationship between occupation and attitudes towards the benefits of the KD; based on which a significant difference (p=0.000) was determined. Of the reasons explained why they thought the KD was or was not beneficial, the Vitaflo employees explained that the KD was beneficial due to its use in the management of epilepsy (57.1%); and medical conditions (42.9%). Dietitians, as well as also recognising the benefits in epilepsy management; emphasised their uncertainty (40%) of the benefits of the KD.

Table 8: Attitude towards the KD as a ‘fad’ diet amongst participants (n=19)

| Demographic Characteristics | Attitude towards the KD as a fad diet | ||||||||

| SA1 | A1 | U1 | D1 | SD1 | |||||

| Percentage (%) | |||||||||

| Occupation:

Dietitian Vitaflo Employee |

0

0 |

18.2

0 |

27.3

12.5 |

36.4

50 |

18.2

37.5 |

||||

1 SA: Strongly Agree A: Agree U: Undecided D: Disagree SD: Strongly Disagree

Table 8 displays the comparison between occupation and the attitudes towards the KD as a ‘fad’ diet. Based on these results, the majority of Vitaflo employees (87.5%) either disagree or strongly disagree that the KD is a ‘fad’ diet, 12.5% however were unsure. This was similarly amongst most dietitians (54.6%); however, 18.2% belief that the KD is a ‘fad’ diet.

Table 9: Attitude towards the KD as a ‘fad’ diet based on participants’ familiarity with the diet (n=19)

| Familiarity with the KD | Attitude towards the KD as a fad diet | ||||

| SA1 | A1 | U1 | D1 | SD1 | |

| Percentage (%) | |||||

| Very Familiar

Familiar Unfamiliar |

0

0 0 |

0

12.5 12.5 |

0

25 25 |

66.7

37.5 37.5 |

33.3

25 25 |

- SA: Strongly Agree A: Agree U: Undecided D: Disagree SD: Strongly Disagree

Based on Table 9, it is apparent that participants who were very familiar with the KD, either disagree or strongly disagree that it is a ‘fad’ diet. Similarly, most participants who were familiar and unfamiliar with the KD also disagreed or strongly disagreed that it is a ‘fad’ diet. From these two groups; however, 25% remained unsure and 12.5% agreed that it is a ‘fad’ diet.

Table 10: Ability of the KD to treat and control medical conditions amongst participants (n=19)

| Demographic Characteristics | KD as a medical treatment2 | ||||||||

| SA1 | A1 | U1 | D1 | SD1 | |||||

| Percentage (%) | |||||||||

| Occupation2:

Dietitian Vitaflo Employee |

0

25 |

45.5

62.5 |

45.5

12.5 |

9.1

0 |

0

0 |

||||

- SA: Strongly Agree A: Agree U: Undecided D: Disagree SD: Strongly Disagree

- Mean difference between Occupation vs. ability of the KD to treat and control medical conditions (p=0.024)

Based on the comparison between occupation and the KD as a medical treatment, majority of Vitaflo employees (87.5%) either strongly agree or agree that it can be used. Only 1 participant (12.5%) was unsure. In comparison 45.5% of dietitians said they agreed also, or were unsure. One dietitian (9.1%) disagreed that the KD could be used as a medical treatment. An independent t-test was used to analyse the mean difference of these variables, based on which a significance of (p=0.024) was observed.

Table 11: Participant opinions towards the KD offering additional health benefits, irrespective of medical conditions (n=19)

| Demographic Characteristics | Opinions towards the KD additional health benefits1,2 | ||||

| Yes | No | Unsure | |||

| Percentage (%) | |||||

| Occupation1,2:

Dietitian Vitaflo Employee |

0

25 |

9.1

50 |

90.9

25 |

||

1 Occupation vs. health benefits of the KD (p=0.012)

2 Mean difference between Occupation vs. health benefits of the KD (p=0.002)

Of the 8 Vitaflo employees involved in the study, 50% belief that the KD does not offer any other health benefits; with 25% believing either the diet does offer health benefits, or are unsure. No dietitians thought the KD offers health benefits; furthermore, the majority (90.0%) are unsure of the benefits. Following the data analysis using chi-square analysis, it was observed that there is a significant relationship (p=0.012) between occupation and opinion towards the KD additional health benefits. Furthermore, having conducted an independent t-test, a significance difference (p=0.002) was determined.

5. Discussion

This study set out to explore the knowledge and attitudes towards ketogenic diets amongst Vitaflo employees in Liverpool and dietitians in Belfast. Due to the lack of literature and limited research available, the author recognised only two studies with some relevance to the study at hand. However, these studies conducted by Hemingway et al. (2001) and Schoeler et al. (2014); focus primarily on the attitudes towards the KD from the perspective of physicians and the parents of children who have been treated. To the authors understanding, this is the first study of its sort to assess the knowledge and attitudes amongst dietitians and those working in the field of nutrition.

5.1 Knowledge of the KD

A series of questions assessing the knowledge of the KD amongst participants such as awareness and familiarity of the KD, source of knowledge, experiences with the KD, and opinions based on this; were included in the study. Participants were also asked to identify components of the KD and what conditions or disorders they believed would benefit from its use. It was noted that participants aged between 18 and 49 years were more familiar (60%) with the KD; in comparison to those aged over 50 years. Furthermore, 100% of participants employed by Vitaflo were familiar with the diet, as opposed to only 27.3% of dietitians (p=0.004) (Table 2). Of the 11 participants who were familiar with the KD (8 from Vitaflo and 3 dietitians); knowledge was most commonly established from studying the diet (Table 3). This may suggest that, as the KD has only resurfaced recently in the past two decades (Jung et al., 2015; Southern et al., 2015; Vehmeijer et al., 2015; Lord and Magrath, 2010; Magrath et al., 2000); that older participants may be lacking in knowledge due to not having studied the diet at university. Therefore, this is a reasonable explanation as to why the younger participants are more familiar with the KD.

Based on the study conducted by Hemingway et al. (2001), 22% of physicians suggested that they would use the KD more if they worked alongside dietitians with more experience; however, the primary research implies that no dietitians who took part in the study have administered or worked with a patient on the KD (Table 3). Therefore, this lack of knowledge and experience amongst dietitians not only affects the patients they treat, but it acts as a substantial limitation on both the use of the diet amongst physicians and their success with it (Hemingway et al., 2001). This finding was unexpected as according to Southern et al. (2015) and Hemingway et al. (2001); consulting with a dietitian is vital to the implementation of the diet. It is the role of the dietitian to determine the suitability of the treatment, assess the patient’s ability to comply with the restricted diet, and chose the best diet for them (Southern et al., 2015). On the contrary, this finding suggests that the KD is not commonly used within dietetic practice and therefore, even though 66.7% of dietitians studied the diet; it is not commonly administered by them as a dietary treatment option. As the KD is a specialised dietary treatment (Lambrechts et al., 2015; Shorvon, 2010; Zupec-Kania and Zupanc, 2008; Kossoff, 2005; Magrath et al., 2000); this could indicate that only individuals who are specialised in its use, such as the staff at Vitaflo, would tend to work with patients adhering to it. With regards to participants’ occupation and experiences with the KD (p=0.011); 100% of Vitaflo employees reported only positive experiences, stating beneficial effects in childhood epilepsy and (26.3%) and the therapeutic effects the diet can have (12.5%) (Table 3). In comparison, dietitians’ opinion towards the KD was solely negative (66.7%), reporting issues with compliance (18.2%, Table 3); and that the KD should only be applied to specific populations (33.3%, Table 4). These findings were also supported by that of Magrath et al. (2000), Dressler et al. (2015), and Lambrechts et al. (2015); of whom all reported discontinued use of the KD due to problems with compliance amongst participants in their studies. It was unexpected however, that 12.5% of Vitaflo employees acknowledged compliance as a negative aspect of the diet (Table 3); since Vitaflo develop and produce a choice of palatable products to aid compliance to the KD (Nestle Health Science, 2017).

Literature suggests that the KD is a high fat, low carbohydrate, adequate protein diet (Dressler et al., 2015; Jung et al., 2015; Lambrechts et al., 2015; Southern et al., 2015; Vehmeijer et al., 2015; Shorvon, 2010; Magrath et al., 2000). According to the primary research, 100% of Vitaflo employees correctly identified these components of the KD, compared to 72.7% of dietitians recognising the diet as high fat, 63.6% as low carbohydrate, and only 18.2% as adequate in protein (Table 5; Figure 1). These findings suggest that there is a difference in the level of knowledge between Vitaflo employees and dietitians, however, this is unsurprising as understanding the constituents of the KD is a crucial aspect for the development of KD products at Vitaflo (Nestle Health Science, 2017). Table 6 further highlights the differences in knowledge between professions; as Vitaflo staff acknowledged epilepsy in children, epilepsy in adults, obesity, diabetes, cancer and CVD as conditions which may benefit from adherence to the KD. Epilepsy in children was most commonly recognised by both Vitaflo employees (100%) and dietitians (81.8%); which is unsurprising due to the strong evidence of successful use of the KD in the treatment and management of refractory childhood epilepsy (Southern et al., 2015; Vehmeijer et al., 2015; Levy et al., 2012; Neal and Cross, 2010; Neal et al., 2008; Kutscher, 2006; Kossoff, 2005). Despite dietitians unsuccessfully acknowledging diabetes, cancer or CVD as benefitting from adherence to the KD, the evidence in these areas of research is notably controversial; and as no conclusive findings have been drawn, further research is required to understand the underlying mechanisms of how the KD exhibits its beneficial properties within these areas. These results (Table 6; Figure 2) may suggest that Vitaflo employees have more knowledge of the areas in which the KD is currently being used. Whilst not all participants may believe that the KD is beneficial in relation to these disorders or conditions, it has been acknowledged by some Vitaflo employees that there is research available in these areas. In comparison, this may demonstrate that dietitians may not have as up-to-date or current understanding of the areas in which the KD is being used. The primary research further demonstrates that 18.2% of dietitians incorrectly believe that the KD can benefit those with heart conditions. These results are clearly illustrated in Figure 2. Despite this, a study conducted by Hartman and Vining (2007) demonstrates that side effects of the KD can include cardiomyopathy and prolonged QT; therefore, the KD should not be recommended for patients with heart conditions due to the associated dangers.

5.2 Attitudes towards the KD

To assess the attitudes and opinions towards the KD amongst participants, a variety of questions assessing the perceived benefits of the diet, opinions towards the KD as a ‘fad’ diet, perceived ability to treat medical conditions, and how effective and acceptable they determined the diet to be, were included in the study. The primary research indicates that the attitudes Vitaflo employees have towards the KD are vastly different from those of the dietitians (p=0.000). All Vitaflo employees agreed that the KD can be beneficial (Table 7), and 87.5% disagreed that it is a ‘fad’ diet (Table 8). In comparison, 72.7% of dietitians are unsure of the benefits of the KD (Table 7); and whilst the majority (54.6%) believe it is not a ‘fad’ diet, 27.3% were unsure, and 18.2% agreed that it is a ‘fad’ diet (Table 8). It is apparent that Vitaflo employees have a positive attitude towards the KD, whilst dietitians’ emphasis their uncertainty and scepticism towards the diet. Based on these findings it was suggested that there may be an association between the attitudes of participants and their level of knowledge. However, despite analysis, no significant relationship was observed between variables (p= >0.05); which was unexpected. It was noted however, that 100% of participants who were very familiar with the KD, disagreed that it was a ‘fad’ diet (Table 9).

A significant difference was also observed between occupation and attitudes towards the ability of the KD in the treatment and management of medical conditions (p=0.024). The majority of Vitaflo employees (87.5%) agreed that it can be used, similarly, 45.5% of dietitians also agreed; however, 45.5% were unsure and 9.1% disagreed that the KD could be used in place of a medical treatment (Table 10). This again suggests that the attitudes towards the KD are comparably different between occupations. Furthermore, the majority of dietitians (90.9%) expressed their uncertainty of the alternative health benefits of the KD, irrespective of medical conditions. Surprisingly however, half of Vitaflo employees have the opinion that the KD does not offer additional health benefits (Table 11). This could indicate that, based on the job, Vitaflo employees’ knowledge and thus attitudes towards the KD is specific to medical conditions; since the products they develop are specialised for Metabolic Disorders, Ketogenic Diets, Renal Disease and Disease Related Malnutrition (Nestle Health Science, 2017). A significant difference between the attitudes towards the health benefits of the KD and occupation was therefore determined (p=0.002).

Despite the insignificant relationship between familiarity of the KD and attitudes towards it, it is clear that knowledge and attitudes correlate; as Vitaflo employees have a significantly greater knowledge (p=0.004) and positive attitudes towards the KD (p=0.011); in comparison to dietitians, who have a lesser amount of knowledge and primarily negative attitude towards the diet. There are various reasons to explain this outcome. The author believes that due to the comparable differences in job roles; it can be presumed that, despite both professions having studied the diet (Table 3); the KD may have been portrayed in very different manners. The education of those working at Vitaflo would tend to be based upon an undergraduate nutrition degree, and perhaps a postgraduate course. Dietitians on the other hand, having to undertake a postgraduate course in dietetics would undergo an alternative educational path. It is possible that these differences in education may results in the way of which the KD is depicted and taught (REF). The study conducted by Schoeler et al. (2014) shows that many parents have a positive perception of the KD; and that parental beliefs regarding ketogenic dietary therapies correlated with their child’s response to the diet. Despite this positive attitude from parents, dietitians still do not administer the diet as they adhere to NICE guidelines. Dietitians, particularly those working in the public sector for the NHS, gain their information from various NICE (The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence) guidelines and recommendations from which they use in their practices; it would unethical for them to question these guidelines. A study conducted by Hemingway et al. (2001) determined that 85% of physicians received training in the use of the KD; in comparison however, dietitians do not receive this training. The role of a dietitians requires a lot less research compared to that of the Vitaflo employees; being the only nutrition professionals to be regulated by law and governed by an ethical code (BDA, 2014); they are required to provide the best nutritional advice (BDA, 2014); and therefore, it is unlikely that dietitians would administer or advise adherence to the KD given that it has not been thoroughly researched and approved for use by NICE. Findings indicate that most dietitians have a negative attitude towards the KD, stating that compliance issues are the main constraint of the diet. Poor dietary compliance has been identified as reducing adherence to the KD due to restrictiveness of the diet or unacceptability of the foods (Dressler et al., 2015; Lambrechts et al., 2015; Magrath et al., 2000); however, a study conducted by Yancy et al. (2004) determined that over a 24-week period, a low-carbohydrate diet had better participant retention in comparison to those on a low-fat diet. The participants on the low-fat diet were asked to restrict calories whilst participants on the low-carbohydrate diet were not. Findings indicated that the low-carbohydrate, KD diet, was associated with decreased energy intake due to supressed appetite (Gibson et al., 2014; Sumithran et al., 2013; Boden et al., 2005); therefore, this indicates that dietitians’ knowledge is based solely on inaccurate information.

5.3 Limitations and Recommendations

There are many limitations to this study. Firstly, the small sample size used may have impacted the validity and reliability of results. Data were analysed using a chi-square test and independent t-tests using SPSS; however, according to Pallant (2016) in at least 80% of cells, the lowest expected frequency should be 5 or more. However, some of the results gained from the chi-square analysis had an expected cell frequency of less than 5, this in turn may have impacted upon the significant results that were gained. Thus, these results should be interpreted with caution. Furthermore, despite the popularity of convenience sampling, it is possible that its use may lead to biased results (O’Leary, 2010; Lavrakas, 2008); therefore, the results gained in this study are not representative of all Vitaflo employees and dietitians in the population; merely just of those within this study. For this reason, a larger sample size should be considered for future studies in order to determine a more representative result that can be applied to this population as a whole. A larger sample size may also allow for the accuracy and reliability of statistical analysis to be enhanced.

Although the KD has received considerable attention and recognition over the past few years, particularly with regards to its beneficial use in the treatment and management of medical conditions such as childhood epilepsy, this is the first study of its sort to investigate the knowledge and attitudes towards the KD amongst dietitians and Vitaflo employees. However, more research on this topic needs to be undertaken before the association between knowledge and opinions towards the KD and occupation can be more clearly understood. So far, majority of the research undertaken surrounding the KD has been limited to epilepsy, diabetes, cardiovascular risk parameters, weight reduction, training and cancer; of which, despite sufficiently strong evidence behind its use (Paoli et al., 2014); more research needs to be conducted within each of these areas in order to conclusively determine its beneficial effects. If more research was conducted in these areas, and with funding from NICE, the KD could be used not only within private ‘profit orientated’ organisations such as Vitaflo; but also within dietetic practice, potentially benefitting more individuals with these conditions within the UK.

6. Conclusion

The present study, which set out to investigate the knowledge and attitudes towards ketogenic diets in the field of Nutrition and Dietetics, is the first study of its sort. While no statistical relationship between knowledge and attitudes was observed, the research reflects that Vitaflo employees have a significantly greater knowledge (p=0.004) and positive attitudes towards the KD (p=0.011) than dietitians; who have less knowledge and more negative views of the diet. There are several reasons to explain these findings.

- This may be due to several reasons – Whilst the difference in attitudes amongst different professions could be due to the level of knowledge or training undertaken, controversial results may just be due to that fact that many of the studies available on KDs are controversial, not many conclusive findings have been sought. Also difference in job roles requires different research

- It was hypothesised that vitaflo employees would have a greater level of knowledge and understanding given their job role, the main finding was comparing this to dietitians to see their level of knowledge and opinions of the KD.

- The main limitation of this study was the small sample size used, therefore further research needs to be done at a larger scale in order to gain more reliable results. This research has brought about many other questions in need of further investigation. Firstly, a study looking at the prior education of Vitaflo employees and dietitians may be beneficial and compare this to their knowledge of the KD to determine if it is the perception they have of it through education or within the job. It would also be interesting to conduct a comparative study between dietitians, and dietitians of whom are specialised in KDs to determine any differences in their knowledge and attitudes and why there are differences. Anything about NICE guidelines?

- Due to the lack of literature further research needs to be conducted surrounding the myriad of areas in which the KD is currently being used.

- Despite the small sample size used in this study, the current study has the potential to add to the limited body of research on the subject in a positive manner. By highlighting the inter- and intraindividual variability in responses to the intervention it has provided the scope for planning future pilot studies and trials.

Cite This Work

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing stye below:

Related Services

View allRelated Content

All TagsContent relating to: "Food and Nutrition"

Food and Nutrition studies deal with the food necessary for health and growth, the different components of food, and interpreting how nutrients and other food substances affect health and wellbeing.

Related Articles

DMCA / Removal Request

If you are the original writer of this dissertation and no longer wish to have your work published on the UKDiss.com website then please: