Knowledge Management (KM) in Academic Libraries

Info: 19828 words (79 pages) Dissertation

Published: 16th Dec 2019

Tagged: Knowledge Management

Abstract – usually 2 paragraphs

What is the subject?

Why is it an important topic to research?

How did you carry out the research?

What did you find out?

Briefly summarise the main findings

jBriefly comment on the significance of the research

Acknowledgments

1 Introduction

1.1 Brief description of the project

This masters’ research project aims to investigate Knowledge Sharing (KS) within academic libraries, specifically focussing on the University of Huddersfield’s library. This research project aims to explore what the KS practices are at the University of Huddersfield’s Library and determine how effective these practices are, identifying areas of strength and weakness, it aims to then inform on future recommendations in order to improve practice.

1.2 Identifying the research topic

According to Uriarte (2008) a crucial element of KM is KS. Sharing knowledge is the vital part of KM systems and processes therefore the types of knowledge that would be shared could be explicit knowledge, this is the written down knowledge on paper or on technological devices or it may be encoded. Then there is tacit knowledge which originates from the individual mind. Through the use of Information and communication technology, KS has been able to reach different locations and levels. For library managers KS is paramount to their job and for strategic planning (Kumaresan, 2010). The topic identified for investigation for this research was ‘Knowledge sharing practices within academic libraries with specific reference to the University of Huddersfield’s library’ because it is has been informally observed that there are limitations in KS practices at the University of Huddersfield’s library.

1.3 Problem statement

Many academic libraries within the United Kingdom are aware of the ever-changing environments and challenges with regards to acquiring and the diffusing and circulating of information. This is due to the changing environments regarding the way that information is currently presented in contemporary society through various means such as online, electronic based information sources and other technologies. Users have impacted on library practice, they are more knowledgeable and expect more from the service. Also, library users have become more independent learners and usually, use electronic technology to connect to the library while simultaneously requiring that academic libraries provide quick responses and assurances.

The University of Huddersfield’s Library, in addition to the challenges that are mentioned above, have to plan for addressing any problems and complexities that may occur with dealing with students and staff, they have to be proactive. The University of Huddersfield’s student enrolment is currently between 20,000 to 25,000. The role of the university to provide a high-level quality service for all students as well as staff. Furthermore, the University of Huddersfield’s Library should ensure they meet all requirements and demands for all users of their services, for example, the Library Staff need to enasure that Summon (the University of Huddersfield online catalogue) is widely available off campus and is accessible to all.

It is assumed that the University of Huddersfield’s librarians should have a clear response to, and appreciation of the changing environment regarding information and knowledge sharing but also be familiar with KS tools and use these to their advantage within both departments to facilitate the knowledge exchange. Therefore, tools for KS would enable tacit knowledge from the librarians to be shared with the service users as well as sharing explicit knowledge which is captured and stored in repositories, databases, on social networking platforms and by other means of online resources, which are all easily shareable and furthers the knowledge sharing and thus prevents any knowledge being lost when the librarians leave.

1.3.1 Aims

The aim of this MSc research project is to investigate KS practices at the University of Huddersfield’s library, identifying if the current practices are efficient and what, if any, the limitations are. It further aims to raise awareness of, and suggest recommendations, for the use of knowledge sharing tools at the University of Huddersfield’s library to further information services to all clients e.g. staff, librarians and students. The research project aims to help raise awareness of the importance of knowledge sharing practices and identify if there is a need for an improved KM strategy at the University of Huddersfield’s library.

1.3.2 Objectives

The main objectives of the project are as follows:

- To investigate what the current knowledge sharing tools and practices are at the University of Huddersfield’s library

- To identify to what extent the staff at the University of Huddersfield’s library utilises knowledge sharing tools.

- To establish from library staff, senior staff / director(s) of the University of Huddersfield’s Library if they acknowledge that the librarians possess the required competencies to allow them to integrate knowledge sharing practices within their work practices.

- To identify the strengths and limitations in knowledge sharing practices

- To suggest future recommendations for knowledge sharing practice improvement at the University of Huddersfield library.

1.4 Research questions

There are certain research questions that will be answered and these are determined by the stated research aim and objectives and the problem statement. The research questions are:

- Are the University of Huddersfield’s librarians’ familiar with the presence and advantages of knowledge sharing practices?

- Do the University of Huddersfield’s librarians have a knowledge sharing culture?

- Do the University of Huddersfield’s library technologies provide a permissive atmosphere for knowledge sharing?

- Does the University of library collect and store information based on their staff including librarians?

- Do senior staff and director(s) of the University of Huddersfield’s library believe that their librarians have the required competence to apply knowledge management tools into their work practices?

1.5 Overview of research methodology

To achieve the set aims of this research project and investigate the set research questions a knowledge an investigation was conducted into the knowledge sharing practices at the University of Huddersfield’s library. The study will utilise a multimethodological approach for acquiring of data this will be in the form of online questionnaires and informal observations, this will be completed by the librarians at the University of Huddersfield library and the administration staff e.g. help desk staff and an online survey that will be completed by the more senior staff and director(s).

1.6 Significance of the project – (rationale)

The significance of the research project is that it intends to contribute towards the wide scope of KM and KS practices within academic libraries but focus more on the areas of knowledge sharing within libraries which according to Liu, Chang, and Hu (2010) has not been extensively researched. Similarly, according to Sarrafzadeh, Martin, and Hazeri (2010)

“Although there are some indicators of involvement of libraries in KM in published case studies (through activities such as development of intranets and institutional repositories of content management and embedding information literacy instruction in the curriculum and employing web 2.0 technologies for knowledge sharing), libraries are still in the early stage of understanding the potential implications of KM” (p. 198).

There has been little research on knowledge sharing practices in academic libraries but more focus on KM tools to ensure that knowledge, both explicit and tacit, are widely shared amongst staff and librarians.

1.7 Scope, limitations and delimitations of the project

The research will focus on the University of Huddersfield’s library in order to increase the awareness of the value of applying knowledge sharing practices at the library. It can be argued that by enhancing awareness and developing the sorts of practices relating to knowledge sharing could improve the library service and performance overtime. The data collected will be from staff members at the University of Huddersfield’s Library

1.8 Structure of the project

The research report is sectioned into five main chapters, these are:

- Introduction – This chapter introduces the research project. It identifies the problem to be investigated, clearly stating the problem statement, aims and objectives and research questions and the significance of the project. It outlines the methodology, the scope, limitations and delimitations of this project.

- Literature Review – This provides a review of the literature on knowledge management and sharing and the practices of knowledge sharing within organisations and specifically within academic libraries, and the benefits and barriers to successful knowledge sharing. It reviews knowledge sharing models.

- Research methodology– This chapter explains the research methodology and methods applied in this project which includes the justification for the methodological approach, the population sample and how participants were recruited, the research method applied, the data collection procedure and the ethical considerations.

- Data analysis and findings – This chapter outlines the findings from the analysis of the data that was collected. The data will be analysed both qualitatively and quantitatively, this data is obtained from both questionnaires and surveys completed by librarians, senior staff (managers) at the University of Huddersfield’s library.

- Conclusions, reflection and recommendations – this chapter will outline the summary of key findings, identify the limitations of the projects and suggest future recommendations for practice. Furthermore, an evaluation of the project will be provided.

1.9 Risks and Constraints

1.9.1 Risks

To see the risk table, refer to Appendix A: Chapter 8 Risks.

1.9.2 Constraints

Refer to appendix A: chapter 9 Constraints.

2 Literature Review

A literature review is paramount to any study and it has several purposes. Kumar (1992) believes that literature reviews allows for acquiring of knowledge through the problems area therefore it is possible to gather the necessary knowledge to progress with the research. Creswell (2009) it shares an insight with the reader on historic studies that are closely tied to a study that is currently undertaken and relates to larger study using dialogue within literature with filling gaps and extending previous studies. The primary literature within the problem area have been considered together to avoid research duplication. Reviewing relevant literature has help to planned objectives and mould the research questioner for this research project. Through reviewing has also indicated some data gathering methods, techniques and instruments.

2.1 What is data, information and knowledge?

2.1.1 Concept of data

The word data is a known noun plural from the word datum, despite the singular formation being rarely used (REF). There is a common consensus on the definition of the word data (REF). More often than not the view of data is that it relates to raw facts which have no meaning or context (Abram, 1997). The most common example of data is statistical data lists for example names, numbers, items. addresses etc. (Gandhi, 2004). Data is classified as numbers, according to Bergeron (2003) who says that data is numerical quantities and attributes which can be derived through investigations, experiments and calculations. Similarly, Uriarte (2008) takes the view that data is numbers but he also suggests that it relates to words or letters that have no context. An example of this is the numbers like five or hundred, without any context these number do not have any meaning at all. In addition, without referring to them in space or time then numbers or data are pointless and have no meaning to them. This is the common case of “out of context” (Uriate, 2008, p.1) and according to Uriarte, (2008) this means that they do not have any meaningful relationship with anything else.

Suurla, Markkula, and Mustajärvi (2002) argue that data is codes, signs and signals which do not have any connotations. Data is the raw facts that do not have any meaning or context except on their own. An example is with organisations who compile and evaluate the raw data looking for trends and patterns. Normally the data that is collected is through the functional process within the organisation (Suurla, Markkula and Mustajärvi, 2002).

2.1.2 Concept of information

The concept of information has a distinctive connotation which depends on the type of context that it is reviewed in. Maponya (2004) argues that data develops into information when the data is deemed to be either: organised, grouped, patterned or categorised which escalates the intensity of understanding to the acceptor.

According to Wiig (cited in Liebowitz, 1999) the term information relates to facts and data that is organised. Davenport and Prusak (1998) argues that when information is in the form of a hierarchical view, the information is classified as data which is processed though value-adding during the contextualisation process. While this may be the case several authors argue that information can also be a kind of knowledge in its own right, they call this kind of knowledge empirical knowledge (Zins, 2007). However, it can be argued that ‘mere’ data is not classified as information. This means that there is no relationship between individual data therefore it cannot be classified as information and making of good quality collection of data is through understanding the relationships with the data or the collection of data, in simple words the context is important when making and collecting data and observing the relations of data (Uriarte, 2008). Furthermore, Drucker (1995) describes information as data “organized for a task, directed toward specific performance, applied to a decision” (p. 109). Nonaka and Takeuchi (1995) describe information as data in context and O’Dell & Grayson (1998) describes is as “patterns in the data” (p.5), whereas Smith (2001) advances the latter two definitions and states that “information is data that have relevance, purpose, and context” (p. 312).

2.1.3 Concept of knowledge

From a hierarchical viewpoint knowledge is the next stage from the process of information. During the process of information being analysed, processed and aligned into context, this forms into knowledge (Alavi & Leidner, 2001). Knowledge is what is stored in the mind of the individual (Alavi & Leidner, 2001). Davenport and Prusak (1998) describe knowledge as a fluid mix that consists of framed experiences, values expert insights and contextual information, this can be developed into a framework for evaluating and assigning new information and experiences, this would be normal and originates from the mind of the knower. Within organisations it is often seen in documentation or even repositories, as well as the organisation’s routines and practices. According to Awad & Ghaziri (2004) knowledge is defined as “a higher level of abstraction that resides in people’s minds and includes perceptions, skills, training, common sense, and experience” (p. 37). Wiig (cited in Liebowitz, 1999) who is known to be a lead writer in the area of KM within business, cites that knowledge is a set of: truths and beliefs, judgements and expectations, perspectives and concepts and methodologies and know-how.

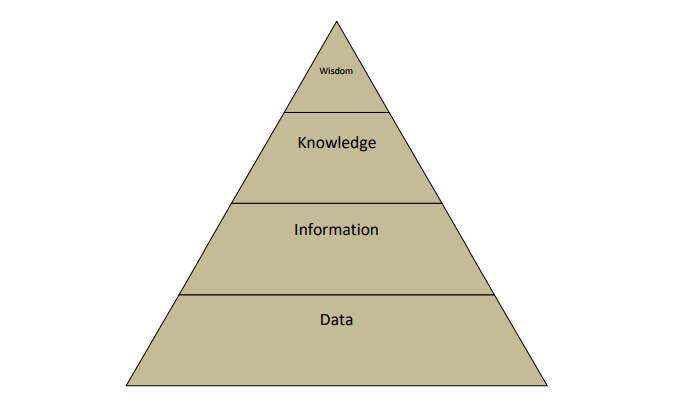

2.1.4 DIKW hierarchical pyramid

The basic building blocks of library and information science is that of data, information and knowledge concepts. In 1989, Russell Lincoln Ackoff was the first to combine all the terms mentioned into a singular formula. Ackoff showed this within a hierarchy which starts at the top, which is the ‘wisdom’, then beneath is ‘knowledge’ then ‘information’ and finally ‘data’ (figure 1). Furthermore, Ackoff (1989) stated that “each of these includes the categories that fall below it,” (p.3) and states that “on average about forty percent of the human mind consists of data, thirty percent information, twenty percent knowledge, ten percent understanding, and virtually no wisdom” (p. 3).

With the stages of the DIKW, data is in the form of observations and has meaning attached until it forms into information which contains questions and answers. Knowledge, on the other hand, deals with refining the information layer and according (Ackoff, 1989) who states that “possible the transformation of information into instructions. It makes control of a system possible” (p. 4).

Figure 1. Pyramid version of the DIKW hierarchy. (Frické, 2009; Rowley, 2007).

According to Rowley (2007) the expression of Ackoff’s model can be viewed as pyramid and has been ever since its creation.

2.1.5 Classification of knowledge

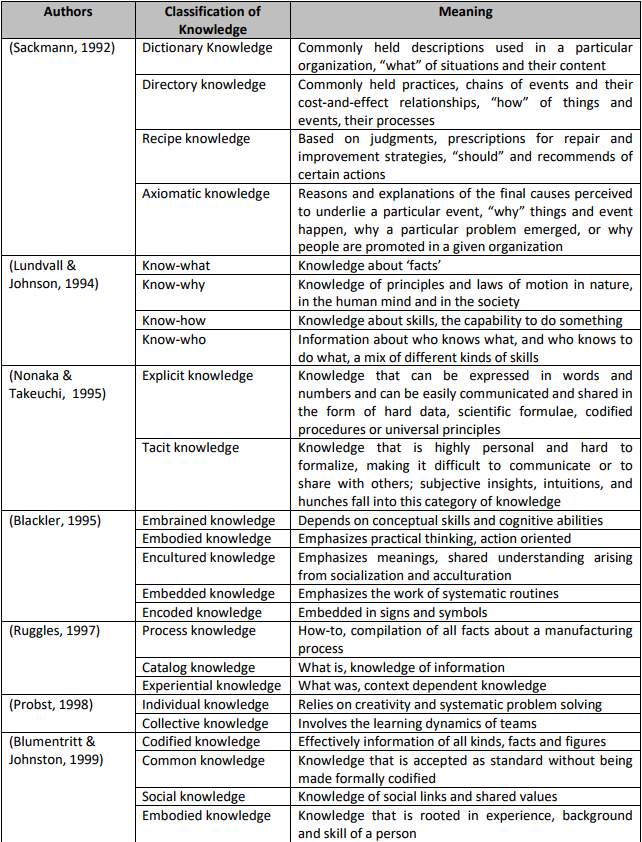

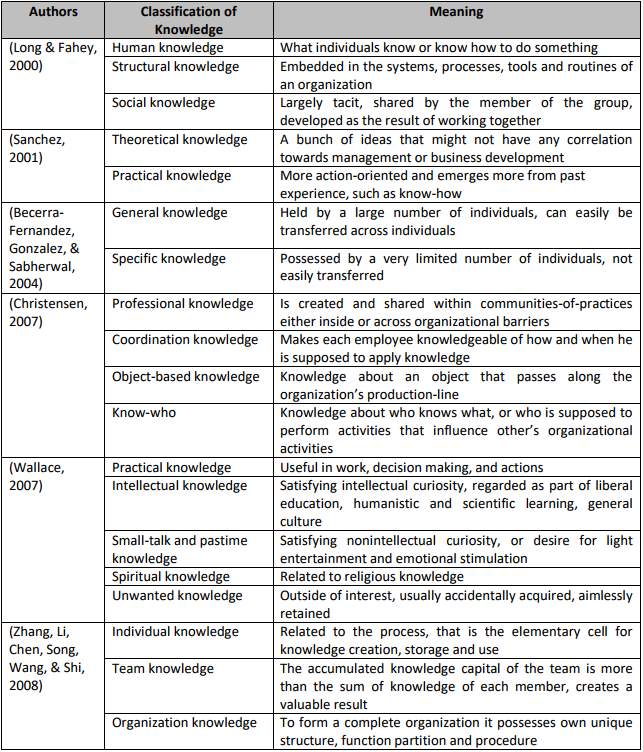

Nonaka and Takeuchi (1995) defined epistemology (knowledge) as “justified true belief” (p. 58) which is shaped on the original ideas of knowledge by Aristotle and Plato. The acknowledgment of different varieties of knowledge is necessary for an organisation’s performance (Pemberton & Stonehouse, 2000). The different types of knowledge can be found in table 1 and table 2 below.

Table 1. Different authors definitions of knowledge before 2000 (Khan, 2014)

Table 2. Different authors definitions of Knowledge after 2000 (Khan, 2014)

2.2 Knowledge Management (KM)

Knowledge Management (KM) is a norm concept dating back to the late 1980’s. This advance archetype has brought awareness that for organisations to flourish, as well as having a good structure of balance, knowledge processes are deemed indispensable. Drucker (cited in Drucker, 1998, p. 2) makes a claim in 1988, implying that all organisations in future generations will be knowledge based. Furthermore, it is necessary to gather and apply the information and knowledge from all the workers within the organisation, such as managers and employees and in addition from clients and customers which are of the utmost priority.

Nonaka and Takeuchi (1995) suggests that knowledge can be categorised into two groups, the first is tacit knowledge, this is when an individual knows the information but is hard to illustrate it and it is not documented and the second type of knowledge is explicit knowledge, which is easy to demonstrate and is documented through databases, on paper or in any other technological means. Wagner-Dobler (cited in Hobohm, 2004, p. 39) suggests that originations of knowledge can be assured as being progressive and allowing for a competitive advantage, if they wisely use the knowledge that they currently have either if its tacit or explicit knowledge. Equally, Kuhlen cited in Hobohm, 2004) suggests that Knowledge Management is the channel of “having better control over the production and usage of explicit and implicit knowledge in organisations of any kind” (p.21).

Fundamentally organisations have concluded that knowledge is an intangible asset, most organisations have the knowledge but they are unable to manage this in an applicable way (Brian Hackett, 2000; Sveiby, 2001). Within the phenomenon of Knowledge Management (KM) there is a rising interest in many fields and disciplines, as well as markets for profit and non-profit sectors and is highly noticeable in all levels of organisations, with the fundamental goal of achieving competence and cohesion for the organisations (Hazeri & Martin, 2006). However, the root of Knowledge Management (KM) is established in business with aim focused on practice and has advanced towards the field of non-profit as well. Knowledge Management (KM) products offer a broad range of opportunities for organisations, such as developing better communication amongst staff and senior management and this bolsters a culture of cooperation (Hazeri & Martin, 2006).

Mårtensson opinion in 2000 is that organisations understood the value of Knowledge Management (KM) at the time but did not implement the concept. Mostly, notability senior managers would be the first group to be aware of Knowledge Management (KM) and its importance that would benefit the organisations but these were often confused or even misguided on the protocols of using Knowledge Management (KM). Hauschild, Licht, and Stein, (2001), refer to a survey of forty organisations within Europe, Japan and The United States of America (USA) and their respective senior management believed that Knowledge Management (KM) starts and finishes with the development of convoluted Information Technology (IT) systems.

Skyrme (2001) viewed that Knowledge Management (KM) was widely implemented although stated that a minority of organisations use the concept of Knowledge Management (KM) throughout their business processes and management decisions. Skyrme (2001) further illustrates that a majority of organisations have accepted the University of Cape Town’s vision of using Knowledge Management (KM) of using the process of knowledge to benefit them for continuous improvements of their internal processes that have culminated in providing exceptional quality of services and products.

2.2.1 Definition of KM

The term Knowledge Management (KM) can be described as an incomprehensible term in relation to its definition. At this present time, there is no accepted term definition that can capture the phenomena of Knowledge Management (KM). Grossman (2007) points out that there is a poor sense of awareness regarding the definition and no awareness to its precepts. Similarly, Sutton (2007) also share this view by suggesting that Knowledge Management can be a test and characteristics this in a numerous of reasons. He analyses as follows:

“KM does not appear to possess the qualities of a discipline. If anything, KM qualifies as an emerging field of study. Those involved in the emerging field of KM are still vexed today by the lack of a single, comprehensive definition, an authoritative body of knowledge, proven theories, and generalized conceptual framework. Academics and practitioners have not been able to stabilize the phenomenon of KM enough to make sense of what it is and what it comprises”. (Sutton, 2007)

On the contrary many scientist argues that Knowledge Management (KM) is more technical rather than the term relating to organisational culture. Furthermore, Knowledge Management (KM) from the concept was giving the impression that it was designed for management in relation of information and documenting. Alternatively, McInerney (2002), portrays that “Knowledge management (KM) is an effort to increase useful knowledge within the organization. Ways to do this include encouraging communication, offering opportunities to learn, and promoting the sharing of appropriate knowledge artefacts.” (p. 1014).

Conversely to and Definition of Knowledge Management (KM) regarding business is made aware by (Birkenkrahe, 2002) who illustrates that:

“Knowledge Management is not just IT, it’s not just change management, or people management, and certainly it’s not only infrastructure. It should affect business strategy, and it is supposed to be the cornerstone of competitive advantage in the knowledge economy. It might make you rich, or if you do it badly, cost you dearly. Some promise that it will feed your cat and take your kids to school, too. Some call it a fad, a guru invention and a money spinner for consultants‟ (p. 2).

Instead (Baskerville and Dulipovici, 2006) described Knowledge Management as “building on theoretical foundations of information economics, strategic management, organizational culture, organizational behaviour, organizational structure, artificial intelligence, quality management, and organizational performance measurement”

As a result, we can conclude that Knowledge Management (KM) is a collection of tools, behaviours and processes within a formulation and conduct of the recipient of the organisation and its gains, supernumerary and circulation of the knowledge that echo the organisation’s processes. The concept of Knowledge Management (KM) intends to provide information and allow this to be freely shared to all the employees of the organisation. It also allows for recipients from outside the organisation this based around maximal usage of accessible information within the organisation and individual involvement from the minds of future employees. For this reason, the essential aspect of the application of the theory is to gain the ideal investment of intellectual capital as this allows to be evolve into advantageous force that devotes towards the development of the respective performance and allows for competence of the organisation to be upgraded.

2.3 Knowledge Retention (RT)

Knowledge retention is paramount to any organisation as they are at severe risk of losing knowledge that is stored by individuals or groups that interact with the organisation or when they are due to leave the organisation. For example, when people from the baby boomers’ generation leave an organisation there will be a need to replace them within the workforce but there could be a shortage of workers ready and trained to replace them. The majority of these employees who are retiring have great amounts of knowledge, skills and wisdom that they have collected over the years which may not have been collected in the organisation’s memory structure or they may not have transferred the knowledge to fellow employees or the organisation (Calo, 2008). Parise, Cross and Davenport (2006) similarly argue that “Departing employees leave with more than what they know; they also take with them critical knowledge about who they know. That information needs to be a part of any knowledge-retention strategy.” (p. 31). However, Parise, Cross and Davenport, (2006) also suggest that it remains to be seen if an employee who has worked for an organisation for fifteen years or more can be replaced with someone else who has the same skills set without disrupting the workforce relations, either informally and formally.

Stein and Zwass (1995) and Spender (1996) argued that it is crucial that organisation always improve the quality of their stance on storing knowledge within their organisational memory as this can allow for greater corporation with collection receiving knowledge. In addition, Stein and Zwass, 1995) argue that advancement in newer technologies may benefit for the storing of knowledge.

Delong (2004) outlined that senior management within the organisation cannot afford to lose knowledge if their forecasts on their performance levels is to be downgraded and also their performance levels though innovation and growth. Therefore, senior management and business analysts of the organisation should address the problems of knowledge retention that is likely to target their own existence within the knowledge economy. As a result Johnston (2005) suggested that “The challenges of knowledge retention are being changes are going to affect industries, organizations, and driven by two forces that are shaping today’s workplace: professions differently, resulting in a kind of “patchwork” (1) an aging population and (2) the increasing complexity of knowledge needed in technologically advanced societies” (p. 2).

Özdemir (2010) acknowledges that organisations have to maintain a store of knowledge so that they can learn from what they have done previously and ensure they acquire and retain and capture knowledge and understand this from current and previous activities to advance their performance and therefore, it is assumed that organisational memory is fundamentally important as so is the means to do so with the use of technology tools such as: e-mail, reports and work processes, that are saved for organisational memory purposes (Inmon, O’Neil & Fryman, 2010).

2.4 Stickiness of Knowledge Transfer (KT)

One of the leading barriers within organisational knowledge transfer is that of knowledge stickiness which is also known as knowledge ambiguity. Brown and Duguid (1998) suggest that knowledge is like an object that is either ‘sticky’ or ‘leaky’ and Szulanski (2002) proposes that a primary reason as to why knowledge flow can become lost in transmission within an organisation is that individuals are more likely to ‘stick’ to their own developed knowledge and tacit knowledge can become very insurmountable to either capture, transfer and preserve.

Sticky arguments focus on challenges within an organisation relating to the flow of manoeuvring the transferring of knowledge. This is promoted by Szulanski (1995, 1996) and von Hippel (1994). For instance, Von Hippel considered the importance of intransigence between the organisation’s research labs and engineering. Although at the same time, Szulanski investigated how stickiness can be involved with the movement of knowledge inherent in ‘best practices’ in separate organisations. To cut a long story short, such arguments show that analysing the movement of knowledge within the internal part of an organisation is essential for performance. The leakiness focal point shows how the flow of information outside of the organisation can occur. The loss of information from the organisation towards their competitors can be detrimental to their vying goals (Szulanski (1995;1996). In addition Liebeskind (1996) suggested that for a organisation’s competitive advantage they fundamentally must combat the leaking of knowledge from their own boundaries to their competitors.

The complication of ‘stickiness’ relates to how tacit the knowledge is. The problems with transferring tacit knowledge are notable with the element of the stickiness of knowledge. However, it is disputed by Teece (1998) who discusses that transferring sticky knowledge can be arduous and the ramification are more strategic based and therefore could have implications for an organisation’s future competitiveness which can be the formation of new enterprises and new services and products. However, according to Argote (1999) and Huber (1991) the majority of authors have indicated a growing enthusiasm in organisational learning which is the way organisation develop new ways of retaining and transfer knowledge. Szulanski (2000) argues how knowledge and learning can be a fundamental and inspiring asset which can be priceless in the organisation and those that do not take in knowledge contribution still have to part to play in benefit from knowledge transfer.

Szulanski (2000) argues that people who transfer knowledge for an organisation often become drained, as the job is hugely time-consuming and is usually demanding and in more serious cases may causes lasting effects and may escalate. In addition, Tamer Cavusgil, Calantone and Zhao (2003) argue that knowledge transfer fundamentally assists in the creation of new innovation therefore it is important for organisations to transfer the knowledge that is available to them internally and adequately in order for them to innovate quickly.

2.5 Knowledge Sharing (KS)

Since the time of Greek philosophers Aristotle and Pinto, there have been philosophical debates on the definition of knowledge and its methods of sharing, and how it is acquired. The ways of dealing with efficient and effective knowledge sharing (KS) has been developed with a level of intensity. The terms of efficient and effective KS can be found in different research streams carried out (Paulin & Suneson, 2012).

The first stream can be found within transfer of product innovation and technology (Allen, 1977; Clark & Fujimoto, 1991). Researchers suggest that it has units of connections between relationships and communication. The second stream is based on tacit and explicit knowledge (Polanyi, ) Furthermore, Nonaka (1991) touches on defining KS and he says that “Explicit knowledge is formal and systematic. For this reason, it can be easily communicated and shared” (p. 98). Also, Nonaka, 1991) explains that KS “helps create a common cognitive ground”…. “among employees and thus facilitates the transfer of tacit knowledge” (p. 102).

The two streams mentioned have to an extent merged since the original article from 1991 by Nokaka. Nonaka and Takeuchi (cited in Khan, 2014) describe that “knowledge sharing is a critical stage in knowledge transfer and [this has] had a strong impact on the research community”. From this statement, it can be argued as the first stepping block for the re-emergence of Knowledge Transfer (KT) and KS is what occurs currently in organisations today. The definition of KS has evolved and Hansen, (1999) and L Jr., (1991) argued that the terms KS and KT have been used interchangeably however some argue that they are different.

2.5.1 Development of KS

2.5.2 KS concept

2.5.3 Analysing KS

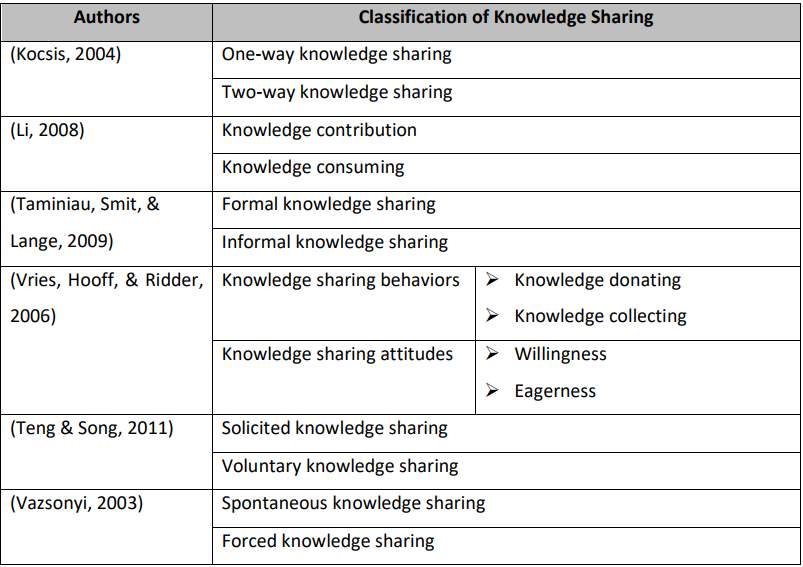

Taminiau, Smit and de Lange (2009) in their study on the KS concept in terms of both formal and informal KS, they suggested that it is a continuous circulation with high magnitude. Formal KS involves KS forms that are regulated by management. Certain examples of these would be: activities, resources and services that are delivered by the organisation and are designed to help the flow of KS and to learn knowledge from each other. Furthermore, other examples include brainstorms and meetings. Table 3 below this summarises the definitions of KS.

Table 3. Different KS definitions (Khan, 2014).

2.5.4 Tools for KS

2.6 The organisation

2.6.1 KS in organisations

An important part of building knowledge for competitive advantage is through the use of KS (Argote & Ingram, 2000; Cohen & Levinthal, 1990; Kogut & Zander, 1992). Hendriks’ (1999) perspective of KS is that of processing and acquiring knowledge, for example one individual wants to process knowledge and the other individual wants to acquire knowledge. The individual who wants to possess the knowledge should be able to communicate the knowledge voluntarily and consciously or refuse to share at all. The individual who wants to acquire the knowledge should be able to understand the knowledge and its expressions (Hendriks, 1999). According to Jackson, Chuang, Harden and Jiang (2006) they argue that KS can be studied or managed at either individual, group or organisational level. However, Shannon and Weaver (cited in Cummings, 2003) describe theories of KS and these were linked somehow through the use of communication and it is assumed that it is a form of information exchange with individuals within organisations. Furthermore, Hooff and Ridder (2004) made the claim that KS involves exchanges that have mutual consent between individuals which results in the passing and receiving of knowledge. It is also a form of sender-receiver relationship that is known to be a relational act that involves communicating experience and knowledge from one person to another, as well as receiving the other person’s knowledge.

In contrast, Kogut and Zander (1992) and Szulanski (1996) express that knowledge is personal and therefore is not freely expressible which can result in poor communication and the use of descriptive language when sharing with others. Bhatt (2002) argues that the KS process should involve professionals and not necessarily management. Bhatt (2002) furthers his argument to state that the sharing of knowledge is a choice chosen and selected by different professionals. Bosua and Scheepers (2007) points out that KS can be effective when knowledge is shared in an efficient manner relating to time, cost and effort. Smith (2005) argues that KS activities are deemed to be either a success or a failure based on two factors which are, firstly how individuals or groups feel about the process and secondly how individuals or groups feel about working with people who they are sharing knowledge with through socialising. Eriksson and Dickson (2000) emphasise the importance of process and argues that different work performances can be determined by the different KS process.

Robertson (2004) argues that KS is a primary goal for organisations to achieve but in reality it is difficult to achieve in practice. Robertson (2004) explains also that employees are averse to sharing knowledge but are more likely willing to take part in work activities that are part of their job role. Robertson (2004) further points out that KS in an organisation relates to “updating client details, discussing project schedules, and completing given assignments”. (p. ). Kim and Lee (2006) similarly point out that KS allows for the diffusion of employees related work experiences and for these to be communicated with fellow colleagues and within sub systems in the organisation.

Azudin, Ismail and Taherali (2009) point out that by KS this cause the organisation’s monopoly and credibility to be lost. Bratianu and Orzea (2010) argue that if all employees of the organisation share the knowledge that they receive then it would allow for the organisation to evolve. Furthermore, Gaál, Szabó, Obermayer-Kovács, Kovács and Csepregi (2011) suggest that KS can become more practical within an organisation but only if employees can understand that sharing knowledge can help them to achieve more in their work performance, help them with job security and will help them to enhance their own knowledge and will improve their own personal development.

2.6.2 Organisational Culture

2.7 KS in academic libraries

Academic libraries in universities should continuously revise and explore new ways of providing their services and this involves them developing processes in order to capture and share tacit and explicit knowledge within their library (Maponya, 2004). Jain (2012) illustrates that academic libraries should share their own knowledge with students, teaching staff and other stake holders of the academic library. The academic librarian role is ever evolving therefore knowledge managers must realise and act, and acquire new practical skills and ways to maintain a level of competence and relevance. According to Gurteen (1999) and Hansen, Mors and Løvås (2005) academic libraries need to consider revamping their service functions and further expand their roles and responsibilities to effectively accommodate the needs of the diverse university community.

Pan and Scarbrough (1999) emphasise that KS activities can be the most difficult activity to implement. Furthermore, Pan and Scarbrough (1999) go on to say how librarians are well trained to share information in their own respective area of community and are also mindful towards circulating information with regards to reprocessing materials and in relation to the overflow of information.

For academic libraries it can be argued that large amount of KS can be heavy-handed and usually information or knowledge that is shared is notability informal and is based on conversation (Webb, 1998). Knowledge is present with employees in any organisation, such as libraries, and at times this can notably be shared in an ‘ad hoc’ way and it is argued that in the past this was not managed effectively and therefore KS was not considered a key indicator to organisational success (Webb, 1998). Academic libraries need to be effective in using their know-how, it is essential they develop into a knowledge based organisation. Academic libraries need to plan to adopt using and sharing knowledge (Maponya, 2004). In a study by Anna and Puspitasari (2013), which was based on KS within Indonesian university libraries, they discovered that KS was not primarily adapted but the implementation of KS can be found in strategy but this only focused on KS implementation using word of mouth (face-to-face) and sharing seminar and training results and not by acting on KS as part of Knowledge Creation (KC) (Anna & Puspitasari, 2013).

According to Shanhong (2000) libraries can control the flow of creating and sharing knowledge amongst the staff. Shanhong (2000) suggests that libraries should develop their own ‘‘document information resources’’. Furthermore, Shanhong (2000) highlights that when libraries share knowledge they must also make use of a comprehensive usage of specialist systems. According to Parirokh, Daneshgar and Fattahi (2009) many researchers from within the library profession have studied the requirements needs for libraries in order to promote KS amongst librarians, customer(s) and suppliers within their day-to-day activities. Whilst this may the case, there is an evolving interest in newer profession(s) and suggestions which deal with these issues. It has been found that global and information era libraries must revolutionise themselves to adopt KS to develop, create and share more knowledge. The library is the same as any day-to-day organisation in terms of KS practices. Therefore, it can advance the rate of knowledge creation and reuse knowledge at rapid rate, this is to keep service quality and products up to the latest standard (Anna & Puspitasari, 2013).

If knowledge is not shared then knowledge is lost at a rapid rate therefore it is paramount that KM practice is essential to deal with the deterioration of knowledge. It is essential that someone who has the knowledge must disseminate the knowledge at the ideal time. Librarians have the task to redesign the current library environment and promote KS practices in relation to library culture through: communities of practice, best management practices, change management, organisational learning and use of KS technologies such as PC’s (Roknuzzanan & Umemoto, 2009). Nevertheless, the KS culture can be more favourable towards KC and this can improve performance and reduce the size pool of effort in relation to duplication. KS culture primarily includes both the organisation and library staff. The organisation should include necessary incentives and training schemes to promote motivation of KS practice amongst library staff and change the assumptions of KS and promote the benefit of use with KS.

2.8 Review of KS models

2.8.1 Externalisation and Internalisation design on simplified KS model

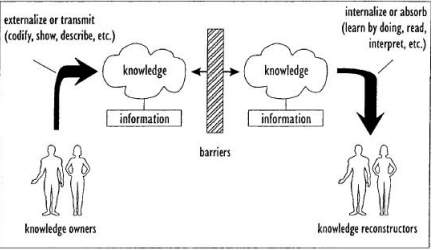

According to Hendriks (1999) KS counts on an association with a minimum of two parties, one that possesses the knowledge and the other that acquires knowledge. The first party deals with communication of knowledge in that it may be consciously and willingly shared or not at all. The forms of communication that would normally take place would be: by acting, speaking or in writing format. The other part directs attention to perceiving the expressiveness of knowledge and tries to make sense of what the knowledge is saying through the use of lists, reading or imitating the acts. This process is notably known in it simplistic form as KS. The notable processes are externalisation and internalisation which make up the process for KS (Hendriks, 1999).

Figure 10. Externalisation and Internalisation within a KS model (Hendriks, 1999)

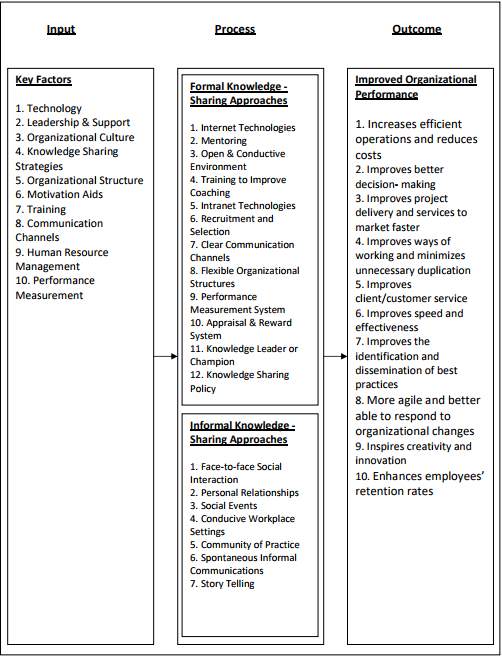

2.8.1 KS model designed on KS approaches

Zin (2013) created a model for KS (Figure 5) which contains both enablers and input (which are important aspects towards fortunate utilisation of KS), the process (which relates to KS approaches) and the conclusions (which relate to organisational performance). The model itself is efficient for studying KS approaches. The model shows the relationship with thirty-nine variables. To accept the factors and grasp he complexity to improve KS approaches within an organisation is vitally paramount to strive for organisational performance (Zin, 2013).

Figure 5. KS model designed with KS approaches (Zin, 2013).

2.8.2 Knowledge capabilities within an organisation

Yang and Chen (2007) developed a framework (figure 2) that supports the process of organisational knowledge capabilities, which has an effect on sharing knowledge within an organisation. The organisation’s knowledge capabilities that Yang and Chen’s framework includes are: cultural, structural, and human and technical knowledge capabilities, and they highlight that each deployment and mobilisation of knowledge resources can be more beneficial and effective. Furthermore, each organisational knowledge capabilities are supported with resources of knowledge. The findings from Yang and Chen (2007) study demonstrates that knowledge capabilities are proven to be beneficial and positive in relation to sharing behaviours of knowledge within the organisation itself.

Figure 2. Framework for linking knowledge capabilities with KS (Yang & Chen, 2007).

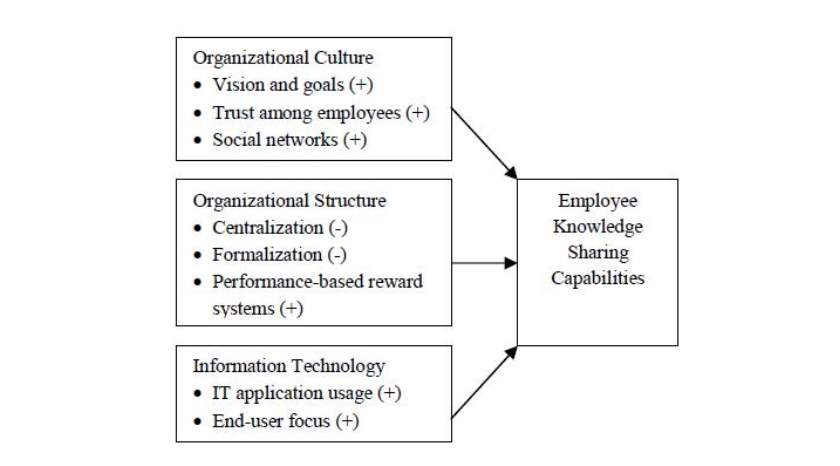

2.8.3 Aspects affecting employees’ KS capabilities

Kim and Lee’s (2006) research on The Impact of Organizational Context and Information Technology on Employee Knowledge Sharing Capabilities was focussed on knowledge sharing capabilities within five public and private sector organisations in South Korea. They determined what circumstances are important for knowledge sharing capabilities in employees (Figure 3). It was acknowledged as being a pioneer study relating to knowledge sharing capability. The ground-breaking study was based on organisational factors that are: organisational culture and structure and Information and Communication Technology (ICT), however the research was known to lack factors that were aimed at the individual (Kim & Lee, 2006).

.

Figure 3. Circumstances determining KS capabilities for employees (Kim & Lee, 2006).

2.8.4 KS and organisational learning – the relationship

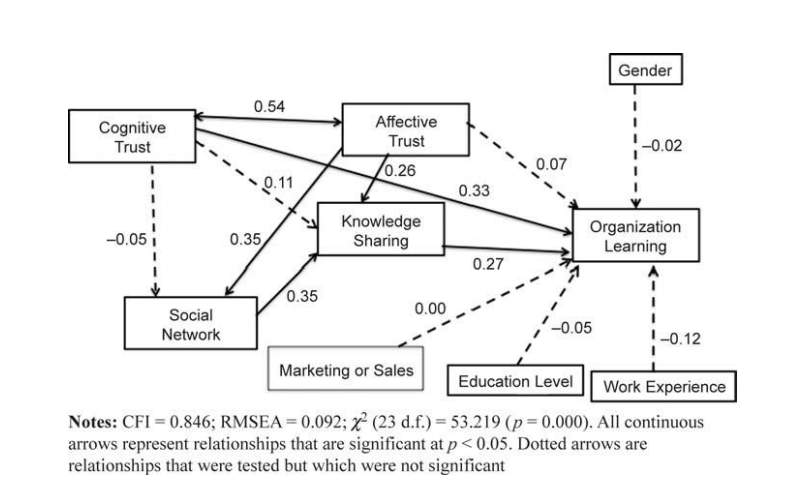

Swift and Hwang (2013) studied the communication involved in knowledge sharing and organisational learning, and considered such factors as: cognitive trust, educational level, work experience, gender, marketing and sales, social networking in order to assess the relationship and correlation between knowledge sharing and organisational learning. The outcome of the research was that KS is undoubtedly interacted with organisational learning (Swift & Hwang, 2013). Figure 4 shows this interaction.

Figure 4. KS and organisational learning relationship (Swift & Hwang, 2013).

2.8.5 Library reference knowledge-sharing model (LRKM)

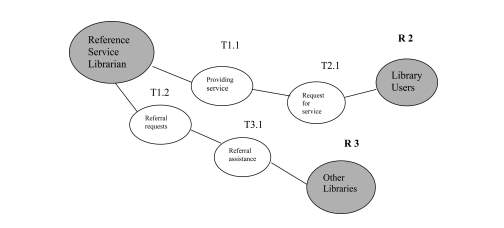

In today’s academic libraries the emphasis is more upon the importance of KS. Parirokh, Daneshgar, and Fattahi (2007) introduced an adjusted model version of a current concept model based on KS known as the Library Reference Knowledge-sharing Model (LRKM) (figure 6) which was primarily constructed for distinctive business processes according to Daneshgar (2004) and it was later modified for distinctive libraries processes. The primary objective of the LRKM was to analyse the KS requirements of librarians when working in conjunction with reference and information services (RIS) processes within academic libraries.

Figure 6. LRKM model (Parirokh, Daneshgar & Fattahi, 2007).

The LRKM model was designed as a connected knowledge map showing the collaboration on how academic libraries are connected in the western world. The model includes semantic collaborative concepts that are: roles, knowledge artefacts and task this is the basics. The grey ovals represent the roles and white ovals represent the tasks. The lines that connect to the roles are called ‘role artefact’ and the lines are there connect to more than one task are called task ‘artefacts’. Role artefacts are knowledge artefacts that are utilised to deliver on a task that is being carried out and it also corresponds to the component of the knowledge artefact that the roles execute privately for the task. A task artefact is another knowledge artefact which normally is involved in the sharing, updating and creating of knowledge, this is so that a correlation can occur between related paired tasks.

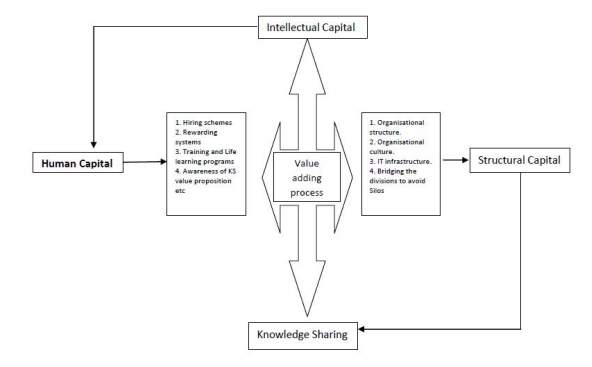

2.8.6 KS model design on public academic libraries with intellectual capital

Figure 7. KS model of university libraries design with intellectual capital (Mushi, 2009).

The connection with intellectual capital and KS is binary (Mushi, 2009). Intellectual capital can advance KS and as a result could advance the formation of intellectual capital, as shown in figure 7. Using KS staff will be able to learn new knowledge that previously was unknown to them and may also improve their own intellectual levels as well as their performance. Whilst this may be the case, the focal point of Mushi’s (2009) research was to examine if human and structural capital could influence and improve KS. The research explored topics such as: motivation, incentives adjoined to KS, creativity, values within the library, competences and social skills adjoined to human capital which could improve KS. Furthermore, the research also explored the structure of libraries and the technology infrastructure and polices as part of the structural capital and it was found that if they were to managed better could lead to better KS (Mushi, 2009).

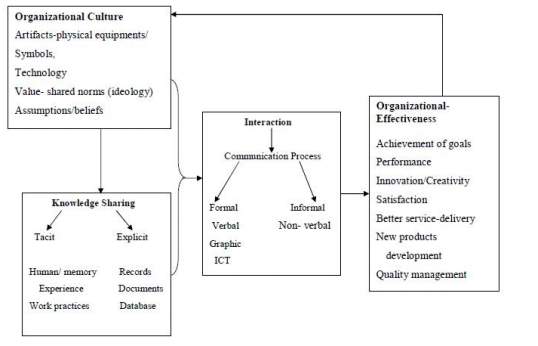

2.8.7 Conceptual model of relationship of KS organisational culture and the effectiveness in academic libraries

This conceptual model by Onifade (n.d.) (figure 8) considers the organisational culture of an academic library, this included: artefacts symbol, technology, values and assumptions and these factors can influence the librarians’ ability to share their own personal knowledge or not at all. The model includes the two types of knowledge, tacit knowledge which focuses on personal knowledge from the individual and explicit knowledge which focuses on documented knowledge. If staff members of the academic library share the same values they can advance their knowledge sharing practices, also technology can play a major role in sharing knowledge within the academic library. If knowledge can be shared it can benefit and increase efficiency from everyone connected within the academic library which could result in improved organisational effectiveness (Onifade, n.d.).

Figure 8. KS relationships with organisational effectiveness relating to university libraries. (Onifade, n.d.)

2.8.8 KS and KT within the KM system building life-cycle

Awad and Ghaziri model (cited in Uriarte, 2008) (figure 9) shows how KS and KT evolve within the building life cycle of KM. The model seems to suggest that when knowledge is captured it is then codified for testing and deployment. The next stage for KS is through collaborative tools, networked and intranets this allows for the deployment in the innovation of knowledge. To conclude this model is aimed at KT for KS.

Figure 9. Awad and Ghaziri model of KS and KT within KM life-cycle model (cited in Uriarte, 2008).

3 Methodology

3.1 Introduction

This chapter outlines the research methodology that was applied. It provides a justification for the methodological approaches chosen, gives an overview of participant recruitment and sampling methods adopted, the data collection procedures, issues of validity and reliability, ethical considerations and the data analysis procedure.

3.2 Justification of methodological approach

3.2.1 Multimethodology approach

3.2.2 Questionnaires

Babbie (2004) acknowledges that responses that are collected from questionnaires and surveys can then be represented into a numerical format. Furthermore, Babbie (2004) highlights that the main characteristic of quantitative research is the art of converting data collected into a quantifiable format. Roberts (2010) views that quantitative research to be ‘logical positivism’. The process of collecting quantitative research starts off with making a plan, this incudes questions to ask or hypotheses formulated. Msweli (2011) describes that quantitative data can be collected through different research instruments, such as questionnaires and surveys. Msweli (2011) further states that quantitative research approaches can be deductive due the questions that are set being required explanations of incidences. Certain examples of quantitative questions will feature: ‘what’, ‘where’ and ‘how many’ (Msweli, 2011; Roberts, 2010). According to Neuman (2014) quantitative research is the art of asking large pools of individuals the same questions and recording their responses. The factors that are mentioned contribute to the decision-making process for choosing it as the primary research method and therefore it was deemed that this approach was suitable as it would allow for collecting data from senior staff and librarians.

Busha and Harter (1980) argues that questionnaires are often used in surveys as primary data instruments for collecting data. Raj (1984) argues that the language used in questionnaires should have clear and consist format and that the unit of questions should state or defined to cover orientation within the questionnaire and that long questions should be avoided at all cost. Raj (1984) extends this to say that the questions within the questionnaires should flow in sequence so that the respondent does not become lost and bored and that the responded is motived to answers all the questions avaibile. For complex questions, they should allow the responded to proceed through steps of reasoning before they answer the questions these are undesirable and they should not be included. In addition, Reddy (1987) deems a questionnaire is a form that includes questions and space for respondents to express their replies. Furthermore, Gupta and Gupta (2008) argue that questionnaire success largely relies on the questionnaires design and the methods of collecting information probably.

The quantitative component of this research study was an online questionnaire that was used to collect data from librarians and help desk staff and an online survey from senior staff and director(s).

Strengths and weaknesses of using an online questionnaire – a paragraph and whay this methid was chosen

3.2.3 Comparative approaches

In the terms of research approach there is unlimited view on the type of question that we can ask and what we tend to do with the research. There are three suggestions as given below:

- Description

- Comparison

- Evaluation

The three suggestions can be identified into research approaches these are:

- Descriptive

- Comparative

- Evaluative

These three approaches are briefly described as followed:

- Descriptive (Research): According to (Williams, 2007) descriptive research is “a basic research method that examines the situation, as it exists in its current state”.

- Comparative (Research): According to (Kumar, 1992) Comparative research is the obtaining information of more than one set of conditions or groups of objects which is compared to multiple sets of data through criteria known as laid-down. Comparative judgement is used to acquire judgments on differences relating to size.

- Evaluate (Research): Kumar (1992), argues that evaluative research is based upon either criterion or method of laid down which includes evaluating judgement which can be good, bad, successful, unsuccessful, effective or non-effective.

The study intended to explore KS practices within the University of Huddersfield’s library and to determined how effective they are therefore the comparative approach was chosen.

3.2.4 Exploratory research

Neville (2007) describes that exploratory research is carried out when there is little or no studies at all about a subject. The aims of exploratory research are to look for patterns, ideas or hypotheses which can be tested and can form the basis for further research topic.

The research that is carried out in this project was exploratory as it aimed to investigate knowledge sharing practices at a specifically chosen University library. KS practices at the University of Huddersfield’s library have not been investigated before.

3.2.5 Autoethnography approach

A type of qualitative method of research is known as autoethnography, this makes use of data about the experiences of the researcher themselves and the context in order to acquire a level of understanding of relatedness with itself and others in the same context (REF). Autoethnography can be divided into three sections these are: qualitative, self-focused and context-conscious (Ref). Firstly, autoethnography is acknowledged as a method of qualitative research (Chang, 2007; Denzin, 2006; Ellis, 2004; Ellis & Bochner, 2000). Autoethnography is a systematic approach to data collection and analysis, as well as making interpretations about the individual and social experiences that involve the individual.

Secondly, autoethnography is self-focused. Therefore, the researcher is the facial point of an investigation and is known as the ‘subject’ (researcher carrying out the investigation) and the object is the participant who is being investigated (REF). Autoethnography data can be paramount to a researcher who can then develop a method of understanding interactions of the external world. However, a distinction between the blurred vision of the researcher and participants can become negative and source of criticism within areas of specifics of the autoethnography methodology (Anderson, 2006; Holt, 2003; Salzman, 2002; Sparkes, 2002). Ellis, (2009) argues that sensitive issues and thoughts are investigation then this become a powerful research tool for understanding social and individuals’ views.

Autoethnography was applied in the form of informal observations of KS practices within the library.

Justify why this was chosen –

3.3 Data types used in this research project

3.4 Data collection

3.4.1 Designing the data collection questionnaires

The online questionnaires consisted of pre-determined questions which were designed to be easily quantified. The questionnaires comprised of a mixture of closed-ended and open-ended questions. The open-ended questions allowed the respondents to provide their own views on KS practices and the issues encountered at the University of Huddersfield’s library. The closed- ended questions mainly forced on using a five point Likert scale for respondents to choose an answer to a question.

The questionnaires also included open-ended questions to gain qualitative responses from librarians, senior staff and director(s) of the University of Huddersfield’s library. This was to establish their own views on KS practices and their own experiences with KS too.

The questionnaires for this research project was created to collect primary data from the target population of the staff members of the University of Huddersfield’s library. The questionnaires were designed based on the review of literature to address the research objectives and to find the necessary answers to the questions that were set. Also, both questionnaires were created in such way that respondents understood the questions to answer them. Questionnaire 1 consisted of 26 questions (Appendix ) and the questionnaire 2 (Appendix ?) consisted of 23 questions which were split into 5 sections for questionnaire 1 and 4 sections for questionnaire 2. The sections were as follows:

Questionnaire 1

- Section one: Basic information

- Section two: Leadership and knowledge sharing

- Section three: Knowledge sharing culture

- Section four: Technology and knowledge sharing

- Section five: Knowledge sharing resources and processes

Questionnaire 2

- Section one: Basic information

- Section two: Leadership and knowledge sharing

- Section three: Technology, tools and resources which enable knowledge sharing

- Section four: General

A briefing statement was also attached to the questionnaires (Appendix ? & ?). Google Forms was used to create the questionnaire. This was used because it is free and easy to use for creating questionnaires for gathering and analysing data.

3.4.2 Recruitment and sampling

Population according to Bless and Higson-Smith (1995) is “the entire set of objects and events, or groups of people, which is the object of research and about which the researcher wants to determine some characteristics” (p. 85). As previously discussed the target population for this research project was professional staff (librarians) and senior professionals (senior staff, director(s)) from the University of Huddersfield’s library. The decision was made to collect data from only the professional staff who was currently working at the University of Huddersfield’s library at the time of this research project.

Purposive sampling was chosen. Denscombe (2007) discusses that purposive sampling is the process of the participant selection in order to gain data to justify the needs of investigation or study.

Within this research project the researcher selectively chose the participants who were professional staff at the University of Huddersfield’s library. The reason for this was

• Staff were easily contactable via email

• The nature of the research project had to include responses from the professional staff at the library.

3.4.3 Method

An academic librarian was approached by email and she was asked fi she would forward the links for the questionnaires to the appropriate library staff. A reminder was also sent after two weeks. Five completed questionnaire 1s were returned. There was no responses to questionnaire 2. Also, the researcher spent time observing the practices of staff informally within the library.

3.5 Validity and reliability

The term validity, described by Howard (1985), is affected by the accuracy which is interconnected with content validity. Content validity according to Howard (1985) are distinguished by a sample that is serves the entire community which it is chosen from. Furthermore, Baumen (1992) argues that context of data can only be known if the data directly comes from the study. Similarly, Bernard (2011) argues with Baumen (1992) comments by arguing that validity indicates a level of accuracy and constancy in relation to being instruments being used for the purpose of research (data and findings). Furthermore, the research instruments using for data gather must be viable and appropriate which should be able to answer the research questions and measure the specific concept. Questions that are asked should refer to the objectives of this research study.

3.6 Data analysis

General themes that included respondents’ opinions in relation to KS, incentives that could encourage them to use KS from the benefits it processes and also barriers of KS amongst staff. The researcher used Google forms and Google sheets which calculated the percentages and the averages from the raw data collected via the questionnaires and surveys in relation to themes from respondents. The results were displayed in graphical context via pie charts that were from Google forms.

3.6.1 Synthesis

The analysis of data from the online questionnaires has been integrated with the data that was collected via the online questionnaire which the questions were similar that was asked. In some cases, questions that are not cover within both the online questionnaires and surveys the reporting will be covered separately

3.7 Ethical considerations

4 Findings and analysis

4.1 Introduction

The purpose of this chapter is to narrate and analyse the results. Contextualisation and discussion of key findings will be covered in chapter five. This chapter focusses on outlining and analysing the key findings. Certain key topics were identified, these were:

- Predominance and the impact on using KS

- Library leadership that includes organisation culture

- Organisational culture dwelling on trust with management and staff that includes librarians

- Technology used in relation with KS

- KM processes used and KR

They were only five responses to the questionnaires, these were all from the librarians and there none obtained from the senior library management.

4.2 Leadership and KS

4.2.1 KS policies

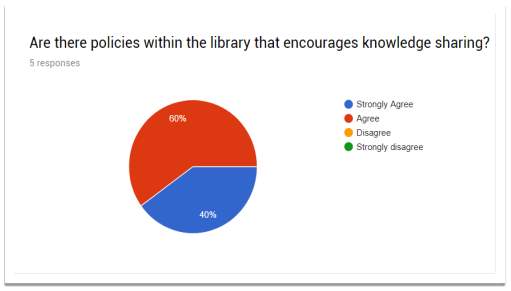

Respondents were asked if they know of any KS policies within the library (see appendix ). The results are shown in Figure 10 below. 60% (3) of respondents from the online questionnaire strongly agreed that there was KS policies and 40% (2) agreed.

Figure 10 – Pie chart to show responses to question 1 – Knowledge of KS policies (author’s own).

4.2.2 KS and organisational structure

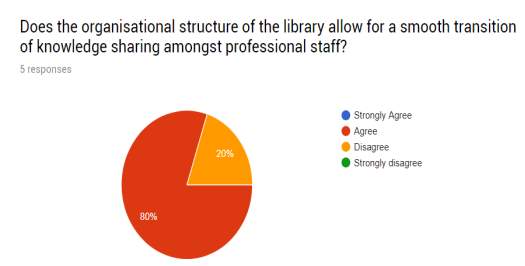

When the participants were asked if the organisational structure of library allows for a smooth transition of KS with professional staff (appendix) 80% (4) of respondents agreed whilst 20% (1) disagreed. See figure 11 below.

Figure 11. Pie chart to show the responses to question two – Organisational structure (author’s own).

4.2.3 Retention of knowledge

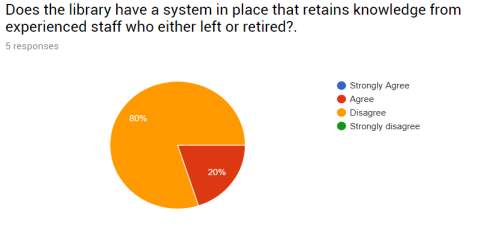

Question 3 asked if there were systems in the library that captured tacit knowledge from experienced staff members who has resigned of left to be made available for the current staff members who still work in the library (see appendix). Figure 12 shows a difference of opinion with 80% (4) disagreeing that the library does not have systems in place to capture tacit knowledge from past experience employees and 20% (1) agreeing that the library does have systems in place to capture the knowledge.

Figure 12. Pie chart to show the responses to question three – Knowledge Retention (KR) (author’s own).

4.3 KS and Organisational culture

4.3.1 KS amongst librarians

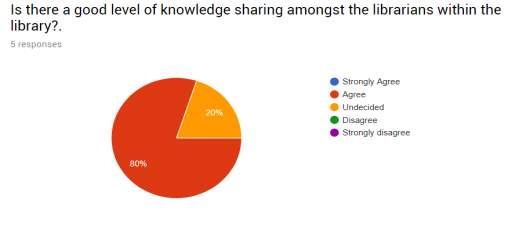

Question 4 asked if there was good level of KS amongst librarians within the library (see appendix ) the results showed that 80% (4) agreed that there is good level of KS amongst librarians within the library and 20% (1) disagreed with question. See figure 13 below.

Figure 13. Pie chart to show the responses to question four – KS amongst librarians (author’s own).

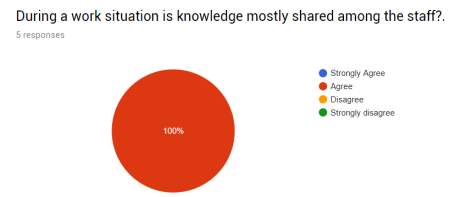

However, when it came to the question asking if KS during a work situation is mostly shared amongst staff members (see appendix ) 100% (5) agreed that KS is mostly shared during a work situation amongst colleagues. See figure 14 below.

Figure 14. Pie chart to show the responses to question five – KS during a work situation amongst staff (athor’s own).

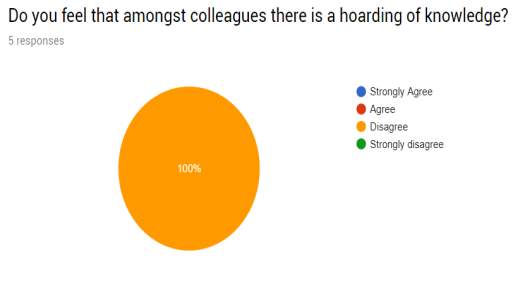

4.3.2 Hoarding of knowledge

It can be noted from the pie chart shown in figure 15 in relation to question 6 that there no hoarding of knowledge amongst colleagues (library staff) (see appendix ). There was a unanimous result, in that 100% (5) disagreed that they was no hoarding of knowledge amongst colleagues.

Figure 15. Pie chart to show the responses to Question six – hoarding of knowledge amongst colleagues (athor’s own).

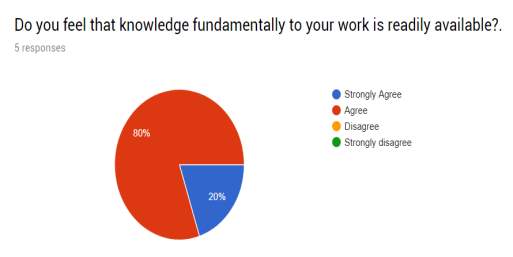

4.3.3 Available knowledge

The reason that this question being asked to find out if knowledge is ready available fundamentally librarian during work (see appendix ) Figure 16 shows the results of respondents via the online questionnaire.

Figure 16. Question seven – hoarding of knowledge amongst colleagues (athor’s own).

As it clearly shows that 80% (4) agreed that knowledge is fundamentally to their own is readily avaibile. Whilst 20% (1) strongly agreed with the question.

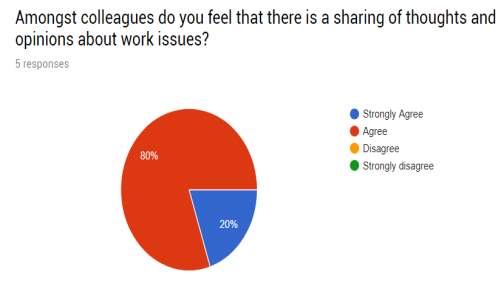

4.3.4 Sharing thoughts and opinions

Figure 17 below shows that majority of opinion that 80% (4) agrees that there is sharing of thoughts and opinions about work related issues whilst 20% (1) strongly agreed with the question (see appendix ).

Figure 17. Question eight – thoughts and opinion on work related issues (athor’s own).

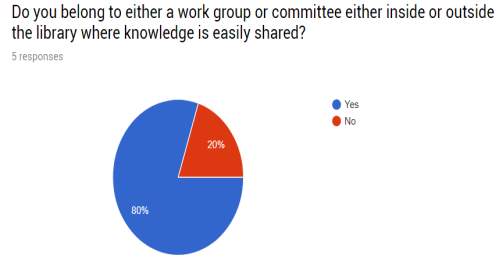

4.3.5 Affiliation to knowledge committees and workgroups

When respondents were asked if they belong to any committees or workgroups inside or outside the library that shares knowledge. Figure 18 shows that there was majority of respondents 80% (4) who said yes that they belong to a committee or workgroup and 20% (1) said no.

Figure 18. Question nine – librarians belonging to either a committee or workgroup (athor’s own).

Of those respondents who said yes, the sorts of workgroups and committees that were mention included:

- Various discussions lists

- Communications and marketing group – (within the library)

- CILIP (UK professional body for librarians)

- SLA (Special Libraries Association)

- ALT-PLSIG (Association for Learning Technology-Playful Learning. Sharing knowledge on using play and games in education)

4.4 Technology and KS

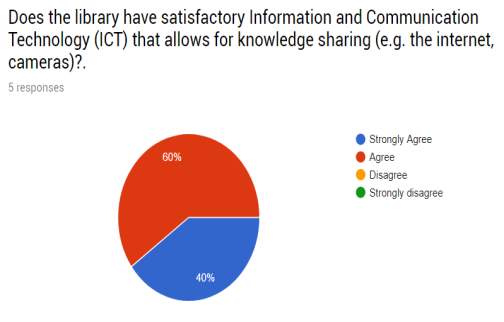

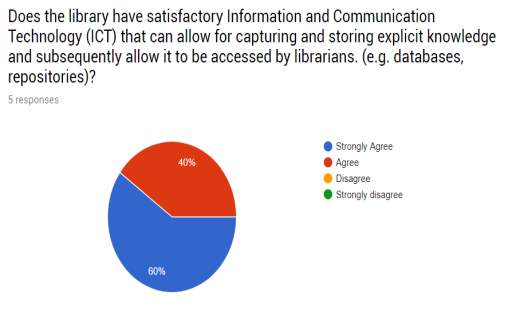

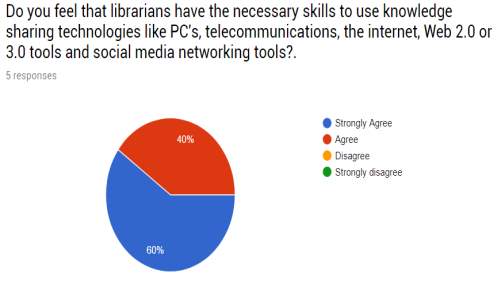

4.4.1 Technologies avaibilty and are librarians’ skilled when using the technologies

Figure 19 shows how respondents agree that the library has satisfactory information and communication technology that enabled KS (internet use and cameras). For instance, 60 % (4) agreed this was to be the case whilst 20% (1) strongly agreed with the statement. Figure 20 shows 60 % (4) of reposidents strongly agreeing that the library has satisfactory ICT that can be used for capture and storing explicit knowledge to be accessible by librarians whilst 40% (1) agree with this statement. Figure 21 shows that 60% of respondents question strongly agree that librarians have the necessary skills with using knowledge sharing tools like Pc’s and social media tools and 40% (1) agreed. (Refer to Appendix for list of questions mention)

Figure 19. Question ten – ICT and KS (athor’s own).

Figure 20. Question eleven – ICT and capturing and storing explicit knowledge (athor’s own).

Figure 21. Question eleven – librarian skills with using KS tools (athor’s own).

4.5 KS resources and processes

4.5.1 Resources that help the sharing of knowledge

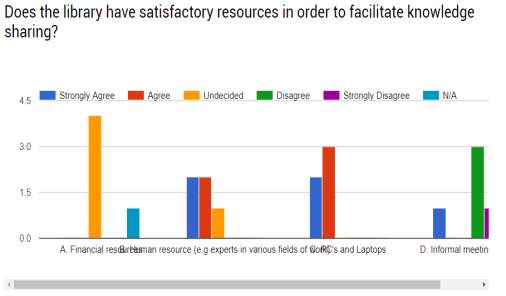

The decision on asking this question was to investigate if respondents believed that the library had the necessary resources that was deemed to be adequate to sharing knowledge (see appendix ) Figure 22 shows most were undecided on finical resources 80% (4) to one who felt that it was not applicable 20% (1). But on the choice of Human resource there spilt decision for strongly agreeing that library has human resources 40% (2) to those who agreed 40% (2) and one who was undecided 20% (1). For PC’s and laptops there was majority of respondents who strongly agreed 75% (3) to those who said agreed 25% (1). For informal meetings rooms, there was strong opinion from respondents that 60% (3) disagreed that library has inadequate space for informal meetings rooms for sharing knowledge for example chart rooms whilst strongly agreed and strongly disagree both had 20% (1) each.

Figure 22. Question twelve – Facilitate KS within the library (athor’s own).

4.5.2 Activities and processes that enable KS

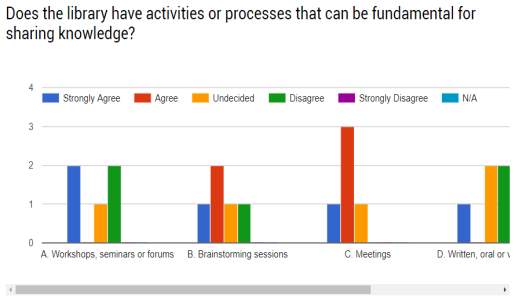

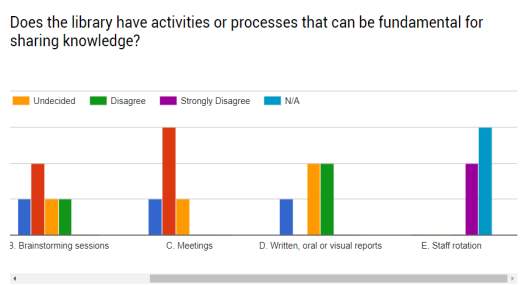

As seen from figure 23 and figure 24 respondents were asked to rate on a variety of activities and process that could help the sharing of knowledge at the University of Huddersfield’s library (See appendix ) Results of this question from respondents showed that some of the options mentions were used extensively whilst other where never used at all. For instance, a split number of respondents were strongly agreeing 40% (2) and disagreeing 40% (2) that workshops, seminars or forums and one respondent was undecided 20% (1).

Here is a breakdown list of the respondents results from this question as follows:

- Workshops, seminars or forums: (40% strongly agreed (2), 40% disagreed (2) and 20% undecided (1))

- Brainstorming sessions: (40% agreed (2), 20% strongly agreed (1), 20% undecided (1) and 20% disagreed (1))

- Meetings: (60% agreed (3), 20% Strongly agreed (1) and 20% undecided (1))

- Written, oral or visual reports: (40% undecided (2), 40 % disagreeing (2) and 20% strongly agreeing (1))

Staff rotation: (60% strongly disagreeing (3) and 40% not applicable (2))

Staff rotation: (60% strongly disagreeing (3) and 40% not applicable (2))

Figure 23. Question twelve – Activities and process that could help the sharing of knowledge part one (athor’s own).

Figure 24. Question twelve – Activities and process that could help the sharing of knowledge part two (athor’s own).

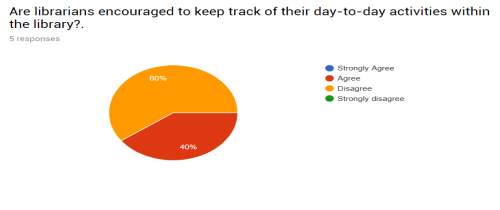

Skyme (2001) assumes that those organisations who recognised the importance of KS will have made better use of knowledge that is there to improve their internal processes which fundamentally results in improve service quality provided. Furthermore Lee (2003) slimily agrees by arguing that “Knowledge can also be embedded in the organisational practices, routines, and processes” (p. 45). From this the researcher created the question as to wither librarians are encouraged to keep track of their day-to-day activities within the library and if minutes of meetings or feedback from workshops are stored and used to improve quality of the library services (See appendix ) The results of responses to these questions are represented in Figure 25 and Figure 26 below.

As clarified in figure 25 below only 60% (3) disagreed that librarians should keep track of their day-to-day activities whilst 40% (1) agreed.

As clarified in figure 25 below only 60% (3) disagreed that librarians should keep track of their day-to-day activities whilst 40% (1) agreed.

Figure 25. Question twelve – librarian day-to-day activities (athor’s own).

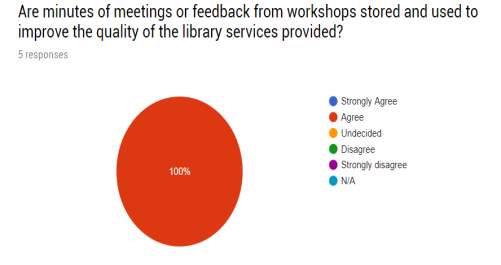

Figure 26 shows how the respondents voted more agreeably when asked if minutes or feedback from workshops are stored and sued to improve the quality of library services. 100% (5) agreed with this question.

Figure 26 shows how the respondents voted more agreeably when asked if minutes or feedback from workshops are stored and sued to improve the quality of library services. 100% (5) agreed with this question.

Figure 26. Question twelve – meeting or feedback stored and used to improve library services (athor’s own).

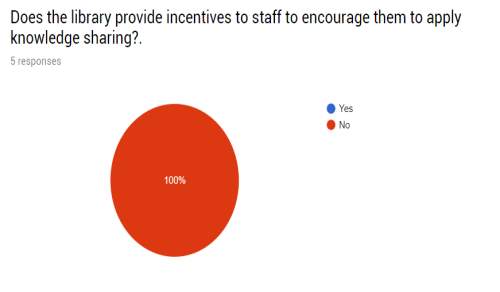

Furthermore on if the library provides incentives to staff to encourage them to apply KS (See appendix ) 100% (5) respondents said no (see figure 27 below).

Figure 27. Question twelve –library incentives to encourage the use of KS with staff (athor’s own).

4.6 Additional features of KS

4.6.1 Activates to encourage KS with librarians

Respondents were asked for their own thoughts and opinions on the types of actives that could be necessary to encourage KS amongst librarians within the University of Huddersfield’s library (See appendix ). A list of respondents’ opinions is shared below which are:

- Time: Scheduled feedback meetings

- Open discussion: regular meetings

4.6.2 Benefits of KS for the library

In relation of the benefits of KS would bring to the library (see appendix ). A list of respondents opinions are noted below:

- Better Return of Investment (ROI)

- Improved workflow

- Stronger team work

- Increased effectiveness

- Happier customers

4.6.3 Barriers of KS to attain a successful KS practice within the library

In relation of the barriers of KS that could affect a successful KS practice in the library (see appendix ). A list of respondents’ opinions is noted below:

- Demand on time and requirement for ever increasing skillset

- Physically being in different offices: promotes a them and us

- Lack of small meeting rooms for quick meetings

- Institutional structures: quite narrow / tall lines of communication, naturally creating silos

4.7 Differentiation of online questionnaire responses relating to job role within the library

4.8 Conclusion

5 Conclusion and recommendations

5.1 Introduction

This chapter will summarise conclusions and deductions that was conduction in the data analyse which was collected by respondents. Recommendation will also be covered to address issues and provide solutions. As previously stated the aim of the this resrech project was to investigate knowledge sharing practice at the University of Huddersfield’s library. This was done by finding out to what extent library staff use KS tools, even though unaware within their day-to-day scheduling. The primary forucs of this chapter is to discuss the issues and burdens that aroused from the data collected from the online questionnaires. The issues and burdens will be examined on the context of the critical KS themes that constituted the development of the online questionnaire

5.2 Examination on critical KS circumstances

During the collection of data and analysation procedures it was becoming clearer that some instances there was difference of opinion between the different librarians in their job role on hoe they acknowledge KS and cirstamnces that relate to KS. Furthermore, at times there was differences between the senior librarians to those who were junior members of staff who vied issues. The conclusions to the themes and chararistic in the responses that will be explained in the following sections and outline recommendations to these issues.

5.2.1 KS and leadership

In relation to leadership, it became noted that most of the respondents to questionnaire one wither was any polices within the library that encourage the use of KS indicated in agreement (refer 4.2.1). Therefore, the library had polices in place for knowledge sharing and to encourage the use of it this show that the library is engaging with their own staff members through good communication and have clearly defined polices.

Results that were show in in chapter 4.2.2 showed that questionnaire one respondents were of ambivalent opinion as to wither the organisational structure of library allows for smooth transitions of KS amongst staff. Therefore, it can be assumed from the results that the ambivalent option could be due to poorly structure strgaey for KS and could be dealt with senior management of library to deal with this issue as a recommendation. Furthermore, it became paramount from this research study that there was no system to capture and retain tacit knowledge from past experience employee (refer to 4.2.3). This view is support from the data collected from questionnaire one. The importance of retain tacit knowledge is vital to the library for junior members therefore a recommendation would be that the library should create an innovative stagery that would include KR stragacy and polices this would establish that knowledge that is stored in individual mind is not lost when the employee leaves the library

5.2.2 KS and organisational culture