Nonhuman Passages in Latinx American Poetry and Performance

Info: 53800 words (215 pages) Dissertation

Published: 15th Nov 2021

Tagged: Literature

This dissertation engages with U.S. Latinx and Latin American texts through critical theories of the nonhuman as a way of reconsidering the boundaries of Man and of how this might reframe our literary pursuits. In my approach, I focus on the connections and disconnections between emergent poetic, Latinx, Latin@American voices, and Hispanic literary production. Specifically, I look at how often marginalized voices represent and rearticulate both the limits of the human form and their relationship to ideas of canon through nonhuman interlocutors.

I suggest that nonhuman figures which transcend the porous perimeters of the human function as figures of passage between ontologies of selves and literary icons. Nonhuman interlocutors and intensities help us to approach reading between the Americas and amongst figures of man in elliptical motions. In my first chapter, “Natalie Diaz, Duende, and Dreamtigers,” I center references to canonical interventions from Federico García Lorca and Jorge Luis Borges as read through nonhuman figures in Diaz’ When My Brother Was an Aztec. “Collaging Kingdoms,” my second chapter, focuses on Aracelis Girmay’s passages between ideas of blackness, hispaneity, and human-nonhuman collages of self-portraiture. Works from latinx Appalachian poets Maurice Kilwein Guevara and Ada Limón comprises the third chapter, which troubles how nonhuman landscapes can destabilize readings of periphery and performances of the nonhuman. Chapter Four, “How to Read in a River Without Water Damage” engages Basia Irland’s frozen performances which deforms the idea of texts through the environments of water, which shape and redirect their readings with poetic interventions from Milk and Filth by Carmen Giménez Smith. This final chapter troubles the limits of an approach to reading through nonhuman forms that are neither purely inside language, nor outside of it.

BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH

L. Rae Buckwalter Cunningham (Yinzer, 1988) obtained her Bachelors of Arts in Hispanic Studies, magna cum laude, University of Pittsburgh in 2011 and a Masters of Arts from Cornell University in 2014. Her research interests include Critical Theories of the Nonhuman, Poetry, and Performance, particularly in the area of Contemporary Latinx Studies. She currently splits her time between Durham, North Carolina and the Internet.

For all the sensitive poets

Beware of paper cuts

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Biographical Sketch………………………………………………………………………………… iii

List of Figures……….…………………………………………………………………ix

INTRODUCTION: MYTHS OF MAN: NONHUMAN FORMS & FIELDS…………………1

ONE: NATALIE DIAZ, DUENDE, & DREAM TIGERS…………………………..28

TWO: COLLAGING KINGDOMS………………………………………………………………60

THREE: APPALACHIAN AMERICAS…………………………………………………………..101

FOUR:HYDROLIBROS OR HOW TO READ IN A RIVER WITHOUT WATER DAMAGE…138

Concluding Remarks………………………………………………………………………177

Works Cited…………………………………………………………………………….194

LIST OF FIGURES

Figure 2.1………………………………………………………………………….….67

Figure 2.2, 2.3…………………………………………………………………………68

Figure 3.1……………………………………………………………………………110

Figure 4.1……………………………………………………………………………138

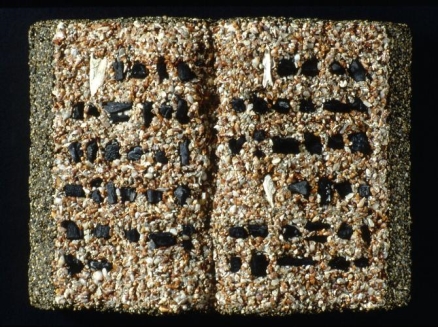

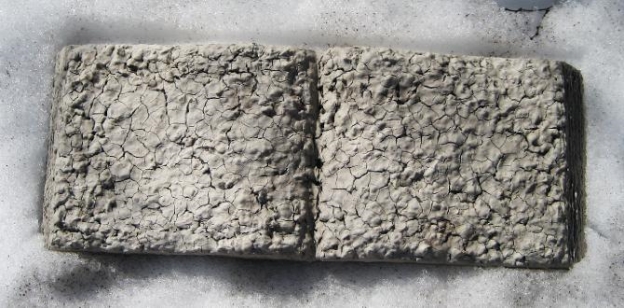

Figure 4.2……………………………………………………………………………141

Figure 4.3…………………………………………………………………………….145

Figure 4.4……………………………………………………………………………156

Figure 4.5…………………………………………………………………………….169

INTRODUCTION

Myths of Man: Nonhuman Forms & Fields

La negra is a beastgirl. From forehead to heel callused. Risen on an island made of shit bricks, an empire. The doctor pulled La Negra from her mother’s throat: a swallowed sword, a string of rosary beads. La Negra’s father is a dulled sugarcane machete. Crowned in her sundried umbilical cord. La Negra claws and wails, craves only mamajuana (Acevedo 12).

— Elizabeth Acevedo, “The True-Story of La Negra a Bio-Myth”

This “bio-myth” is taken from Acevedo’s collection Beastgirl & Other Origin Myths, a chapbook which addresses many of the concerns of this dissertation through its demonstration of overlapping myths, diasporas, and how Latinx poets, like Acevedo, position nonhumans as agents in the crafting of origin stories which span across Latin@American spaces. I open with Acevedo’s resounding lyrics to give shape to this project; it occurs to me as appropriate to cite Beastgirl & Other Origin Myths as an introduction also functions almost like an origin story. And so mine will depart with the breath of the Caribbean beast-girl, clawing though the page. Not only the beast-girl, but also her myth-making, too, resonates here.

One of the premises that this dissertation departs from are the myths of Man, a theory taken from Sylvia Wynter’s ruminations on the rigidity of an idealized, limited idea of Man. This “myth” is one that sustains a singular and exclusionary limit of the form of Man. Wynter argues this point in her essay “Unsettling the Coloniality of Being/Power/Truth/Freedom Towards the Human. After Man. Its Overrepresentation: An Argument.” She sustains that “The struggle of our new millennium will be one between the ongoing imperative of securing the well-being of our present ethnoclass (i.e., Western bourgeois) conception of the human.

Man, which overrepresents itself as if it were the human itself, and that of securing the well-being, and therefore, the full cognitive and behavioral autonomy of the human species itself/ourselves” (260). Many of the curiosities which first sparked this foray into the lives of human/nonhuman forces in poetry and performance in Latin@American and Latinx Studies, had to do precisely with this weight of representation and questions about how to counter Man’s hegemony through poetics.“This beastgirl,” that Elizabeth Acevedo claims as “la negra”, what blackness is and is not—hinges on the edge of the nonhuman and its inquiry, its myths, which have emerged as some of the most thought-provoking concepts in contemporary literary scholarship.

In my dissertation project, I engage with nonhuman figures and forces from both U.S. Latinx and Latin American texts through insights from critical theories from the Environmental Humanities and Global Black Studies.

My line of inquiry traces the fringes or fractal edges of human and nonhuman boundaries, which I see as opportunities to, one, question the nature of these limits and, secondly, to think about other avenues where connections and disconnections emerge in tandem. In my readings, I approach a range of Latinx writers who scrutinize ideas of text and canonical literary figures through a nonhuman poetic turn.

By analyzing works from Latinx poets like Aracelis Girmay, Maurice Kilwein Guevara, Ada Limon, Natalie Diaz, Carmen Jimenez Smith, and performance artist Basia Irland, this dissertation reflects on how iterations of nonhuman presences might work as ciphers that generate meaningful questions about forms of life and livelihoods between spaces and literary traditions. This framework was inspired by an autopoietic approach from Sylvia Wynter a theorist whose work asks how or what kind of counterpoetics might go towards the Human, After Man, the latter being an overrepresented Western bourgeoisie articulation of what it means to be human.

In this project, I strive not to go toward the human, precisely, but around the limits of it. This is where autopoiesis comes into play, autopoetic readings are always already asking questions about the nature of the self through a porous, semi-autonomous frame, which I use to trace how the poems in my dissertation are open to nonhuman interventions and environments. I pursue this openness, not only between species but between spaces as a kind of nonhuman poetic traffic.

I was particularly interested in parsing how Sylvia Wynter employs the term autopoiesis, as she adopted it from Chilean biologist Humberto Maturana’s usage. Wynter’s work has been most commonly read within the field of black studies, however, I see her corpus of texts as strongly informed by her background as a Hispanist. Maturana’s autopoietic haunting, is a prime example of this, and Wynter’s work crystalizes how questions of the human, Global Black Studies, and Latinx-American Studies might collide.

In my close readings of the nonhuman in Latinx poetry and performance, I wanted to test these encounters and edges as well—between human and non, but also between Latin American Studies, Latinx Studies, and Global Black Studies. I suggest that reading in this way offers alternative mappings or routes between texts, disciplines, and ontologies. As Wynter blurs these boundaries between disciplines and selves, so did, in turn, many of the poets and artists I discuss.

While mining Latinx texts, I found that many authors used nonhuman intensities as pathways through which to engage with Latin American authors like Lorca, Borges, Puig, Eunice Odio, Marti, the force of duende, etc. and I attempted to map this out in my discussion as a way of questioning how nonhuman creativities might inform how we think about reading Latinx texts and how they meet with or diverge from the Latin American canon.

Rather than to claim any one central figure of the nonhuman or human as the crux of my argument, I worked across a range of nonhuman figures and forces in order to speak about a potential strategy for reading alongside or through the nonhuman. I wanted to offer another lens from which to consider our Interamerican aesthetics, which fashioned more traffic, more possibilities, rather than a reducing these texts to a type. I am hopeful that as I continue to develop this layered project that it has the possibility to contribute to diverse bodies of scholarship.

It is important to acknowledge the ways in which contemporary Latinx and Latin@American writers reframe what it means to rely on prepackaged ideations of the fully-human. I use ‘Latinx’ here and ‘Latin@American’ purposefully to reflect what I think is an important distinction applicable to many young writers, which is a state of liminality often reflected in their work. Latinx refers to writers who may consider themselves (or are read as) U.S. based or centered in an American Studies canon (though perhaps also relegated to the fringes of “minority literature”), while Latin@American authors, though perhaps having spent decades in the United States, may orient their writing more toward the traditions of the Hispanist canon.

In my readings, I have found that these distinctions, Latinx or Latin@American, are not hard-lined, and, while analyzing the limits of human/nonhuman forms, I also ask questions about how these writers might be occupying positions at the edge of or even transcend these boundaries or thresholds of canon.

My approach to this vacillation and reconsideration of how Latinx and Latin@American literary productions are theorized owes much to José David Saldívar’s illuminating discussions found in Trans-Americanity Subaltern Modernities, Global Coloniality, and the Cultures of Greater Mexico (2011), Claudia Milian’s Latining America: Black-Brown Passages and the Coloring of Latino/a Studies (2013), and Michael Dowdy’s Broken Souths: Latina/o Poetic Responses to Neoliberalism and Globalization (2013). At stake in the works of all the poets and artists whom I will address in the following chapters, are the nuances of the ways in which humans and nonhumans coalesce across a range of geopolitical spaces and inform ideas of reading.

My concerns are primarily how to read the ways in which these writers work through nonhuman intensities as figures of passage to mediate interstitial discourses. I focus on these moments where “the human” has not been enough, which allow the critical reader to look, with the artist, to the edges, the insides and outsides of this form to the limits of life. This is intriguing, given the ways in which these discourses of human and Other have been complexly intermingled and shifted across spaces and disciplines.

I argue that this is crucial as, by in large, critical theories of the nonhuman have oriented themselves from a position that does not necessarily privilege the reverberations of Latin@American diasporas. Thus, a reconsideration of nonhuman figures as guides or ciphers for these spaces might offer up interesting possibilities for reading. Throughout this dissertation, I defer primarily to scholars from Global Black Studies, and Latinx as well as Latin@American Studies. I am, and these frameworks are, however, in conversation with a community of scholarship and metaphysical questions about the limits of life, death, humans, and other-than-human debates. Thus I will review here a brief glossary of some terms I touch on as a sort of field guide. This endeavor is not intended to be an exhaustive or comprehensive explanation of these terms; I am merely paraphrasing where my orientation stems from.

Animality: a problematizes the caesura between humans and nonhuman animals divide and ideas of rational and irrational beings. Discussed widely by philosophers like Kant and Nietzsche.

Anima: Taken from Aristotle’s De Anima, proposes variations on ensoulment and underscores the importance of potentiality, perception, and ideas of life across several planes, including the “nutritive life”, which is the condition for partaking in life.

Bare Life: GiorgioAgamben tests the limits of “mere life”, reimagining concepts like biopower, bios/zoe, sovereign violence, and modern subjectivities. For a different opinion, see The Beast and the Sovereign, by Derrida.

Death: Humans die; animals, or those who are poor-in-the-world, perish—Martin Heidegger.

Intensity: The encounter, the spark, a cruelty.

(New) Materialism: An emerging and interdisciplinary way of troubling divides like nature/culture, anthropocentrism, embodiment, and how nonhuman forces resonate across livelihoods and politics.

Potentiality: The presence of an absence; to not do or not be.

As evidenced above, many explorations of critical theories of the nonhuman have been more concentrated on European referents as primary sources of theoretical engagement than, say, other minority fields or perspectives from area studies. Nevertheless, within the field of Hispanic Studies, innovative, critical engagements with the nonhuman seem to be ever emerging, Gabriel Giorgi’s work in Formas comunes: Animalidad, cultura, biopolítica (2014) was particularly notable and interrogated an impressive range of important canonical questions and foundational texts from the region.

Other exceptions to a more Eurocentric focus include Stacy Alaimo’s work on Material FeminismsandBodily Natures, Michael E. Dowdy’s transnational, ecocritical engagements in Broken Souths, Eduardo Kohn’s anthropological approaches to the entangled worlds of humans and nonhumans in How Forests Think, Mel E. Chen’s text Animacies, which privileges the reading of race and nonhumans, and Alexander Weheliye’s studies of black feminist critical theories of the nonhuman in Habeas Viscus, which returns to the work of Hortense Spillers and Sylvia Wynter on critical theories of the nonhuman, flesh, and racializing assemblages.

These theoretical voices, in addition to texts from the environmental humanities and fields of critical animal studies, strongly informed the shaping of this dissertation project. Of this chorus, however, I have chosen to frame my work most closely with insights taken from Sylvia Wynter, Alexander Weheliye, genres, and the idea of autopoiesis they discuss as ways to orient my subsequent chapters.

Wynter is Here

Through writers like Sylvia Wynter, we can consider other points of orientation from which to question the nonhuman; specifically, from the intersections of Latin American Studies and the field of Black Feminist Theory. Sylvia Wynter’s unique work connects several fields, Caribbean, American and Latin American Studies, Critical Race Theory, to the boundaries of science and neurobiology. Her writing poses tremendous critical questions that range across and between disciplines. Sylvia Wynter’s contributions to scholarship are far reaching though they remain widely understudied.

In recent years, scholars have just begun to parse her 900-page unpublished manuscript, “Black Metamorphosis,” which serves as an outline and precursor to Wynter’s theories of the human. Wynter establishes in this text, which she elaborated over the course of a decade in the 1970’s, what she cites as the status of “non-norm and nonperson” blackness in the New World, and that this experience serves as the backbone of, or as a foundational concept through which contemporary narratives of the Western world order constitute themselves and their citizens.

Wynter argues that it is through the abjection of subjects who are inscribed with an other-than-human status that these orders are sustained. She names this as a counterpoint to the overrepresentation of Man while questioning the ontological bounds of the human. Throughout her many approaches to move beyond Man, Wynter writes about a variety of figures and global events. Some of her most foundational writing centers around the ideas of Man 1 and Man 2, taken from “Unsettling the Coloniality of Being/Power/Truth/Freedom: Towards the Human, after Man, Its Overrepresentation-An Argument.”

Man 1 was a renaissance figure of man whose exclusionary boundaries were delineated by both the paradigms of theocentric thinking and colonial encounters in the Americas. Man 1 was configured as fully human, in such that he was a rational subject by way of a colonial and supernatural social order. For Wynter, then, the ideology that produced Man 2, was formed in part by precedents from the logic of Man 1.

Man 2’s merits are based in a subsequently secularized, biological form that parsed out the “naturally” dysselected, those who were categorized as racially inferior from Westerners, from those “selected” or taxonomized as superior through Darwinian biocentric orders of knowledge. Wynter’s approach to the boundaries of the human, unlike that of a strictly biopolitical framework, is centered through a decolonial or anti-colonial lens. This perspective is foregrounded between the Americas as a space of encounter where the limits of the human are railed against and around by those who were placed outside of its bounds.

In this dissertation, I consider that the way Wynter approaches theories of the human and beyond Man and how this informs how we might read Latinx and Latin@American poetry and performance. Departing from some of Wynter’s questions and conceptual frameworks like Man 1 and Man 2, I ask, not only how to move beyond Man toward the human, but also how to read toward the edges of the human and how this reading might influence ideas of origin stories, myth, and trans-American retellings.

Wynter, who is also a novelist and whose critical writings are highly poetic in tone, problematizes some of these ideas in her work, which I will weave throughout my dissertation, paying particular attention to the ways in which these concepts pertain to literary production. There are three elements of Wynter’s work, beyond some of the conceptions of Man that I have already outlined, which have given particular shape and inspiration to this dissertation project.

Firstly, I was influenced by Wynter in regards to myth and origin stories; Wynter aims to expose how myths and origin stories are constructed in accordance with hegemonic constructions and exclusionary discourses of Man, as in Man 1 and Man 2. In “Unsettling the Coloniality of Being/Power/Truth/Freedom: Towards the Human, after Man, Its Overrepresentation-An Argument”, Wynter riffs on how to “enable the now globally expanding West to replace the earlier mortal/immortal, natural/supernatural, human/the ancestors, the gods/God distinction as the one on whose basis all human groups had millennially ‘grounded’ their descriptive statement/prescriptive statements of what it is to be human, and to reground its secularizing own on a newly projected human/subhuman distinction instead” (264). In her approach, Wynter is leaning into the limits of the bios/mythoi and offering possibility of approaching alternative origin stories that speak to other modalities of humanness through close readings and creative reinterpretations of canonical texts, like Fanon’s Black Skin, White Masks, for instance. These concepts and unique approaches strongly informed my first and second chapters, in which I approach selections from Natalie Diaz’ and Aracelis Girmay’s poetic texts. Therein, I chart the emergence of alternative origin stories between interspecies and intertextual encounters. Through highlighting techniques like collaging and self-portraiture by way of interspecies referents in their poetry, Girmay and Diaz, transcend exclusively human boundaries and diasporic spaces while probing ideas of canon and genre.

The second influential thread in Wynter’s work also stems from her approach to genres. Wynter writes about “genres” of humanness and how the West, through colonial violence, has forged over-represented, genre-specific, descriptive terms which are impressed into marginalized subjects. Wynter uses the term “genre” as a performative one and troubles its origin root which is conflated with gender. I approach this play on “genre” and its limits as related not only to shades of other-than/humanness but also of genre in the literary sense of how to read and categorize texts. While I read to the edges of the human as a practice of counterpoetics to the domination of Man, I am also testing the form of the text itself which is reshaped through these experimental readings.

The third thread which runs through Wynter’s writing and informs this dissertation is her shift to the “scientific”—from Aimé Césaire’s “science of the Word” (Discourse on Colonialism)—which focuses on “the Word”, mythoi, and nature, bios, together with her invocation of systems like autopoiesis. What Wynter proposes through these discourses is a re-ordering of our systems of knowledge, an argument which I extend to the field of literary studies and Latin American studies.

These themes, among others, can be seen reflected in the trajectories of Wynter’s influence on more contemporary scholarship. As I have noted, much of Wynter’s writing is concerned with the category of the human and Black diasporas, particularly from a Caribbean lens; this has been explored at length in both the collection of essays, Sylvia Wynter: On Being Human as Praxis edited by Katherine McKittrick and in Alexander Weheliye’s publication Habeas Viscus: Racializing Assemblages, Biopolitics, and Black Feminist Theories of the Human. Weheliye stipulates that Wynter’s approach “provides alternate genealogies for theorizing the ideological and physiological mechanics of the violently tiered categorization of the human species in western modernity, which stand counter to the universalizing but resolutely Europe-centered visions embodied by bare life and biopolitics” (27).

I am interested in tracing these geographies and connecting them with their possible re-readings in a Latinx and Latin@American literary context. Two of Wynter’s chief interlocutors—Walter Mignolo and Anibal Quijano—are overtly concerned with Latin American Studies, and it is through considerations of the “coloniality of power” (Quijano) and “colonial difference” (Mignolo) that Wynter also foregrounds a dismantling of a singular mode of humanness; toward modalities or genres of the human, a useful framework from which to re-examine ideas of genre and canon. Weheliye orients Wynter’s work by way of Global Black Studies, though I seek to trace her work in a different direction, through Latin@American and Latinx Studies. What Weheliye stipulates, however, that Wynter does for the field of Global Black Studies is crucial, and has resonances for other fields of minority literature and area studies:

Wynter’s model ushers us away from thinking race via the conduits of chromatism, which simply reaffirms the putatively biological basis of this category, or the radical particularity of black life and culture, which accepts too easily the unimpeachable reality of the “Man- as- human” episteme. By contrast, the insights reaped from the comparison of different black populations in recent formulations of black diaspora studies tend to reinforce exactly this particularity, thereby consenting to the current governing manifestation of the human as synonymous with western Man. Instead, Wynter constructs a model of black studies that has as its object of knowledge the role of racialization in shaping the modern human and that takes the resultant liminal vantage point as an occasion for the imagination of other forms of being and becoming human (25).

Weheliye discusses the promise of black studies through a reconsideration of the boundaries of the human, centering his discourse decidedly in Sylvia Wynter and the Black feminist theorist, Hortense Spillers, rather than, for example, solely in critical frameworks drawn from biopolitical or bare life models; from Foucault or Agamben’s texts in other words. At the same time, the contributions from these European theorists indeed, too, offer invaluable insights into the limits of the figure of the human and who has been classified as such or exiled from its limits. My considerations of Wynter seek to position this project from a perspective which considers several frameworks from the disciplines of critical theories of the nonhuman. Rather than consider how Wynter might shape the field of Latin American Studies at large, I probe where the connections and disconnections between literary figures and genres of the human might intersect. In doing so, I trace several waves of emergent poets, reflecting on their use of lyric, nonhuman interlocutors, text, and form.

My engagement with Wynter has to do with, then, looking to the limits of the human as a way to reconsider nonhuman encounters through poetry and performance. This is not a “pressed service” of the animal either as merely or exclusively a metaphorical entity. Rather, I see these forces as working in elliptical motions. I also want to stress that this is also not a “comparative” reading. I’m not comparing marginalized persons to nonhumans. Comparative work with nonhumans and minorities, particularly as it pertains to animals, permeates descriptive and mongrelized depictions in the U.S. Southwest of Mexicans and Mexican-Americans that have been used for segregation purposes (one could recall the signs “No Dogs or Mexicans Allowed” that Cynthia E. Orozco has written so eloquently about, for instance). These close-readings I conduct are not treatments of people as animals or suggesting that human is a category to be overcome.

However, it is important to acknowledge that historical and contemporary hegemonic systems have not treated these groups as fully-human and often look past this entirely when gazing beyond the human or in the abyss between human/nonhuman. Wynter’s work points to the edges of the human and enables the reader to reconsider forces outside of “traditionally” acknowledged humanity to pass between kinds of death where this fullness of certain qualities of life wanes or pales under what has been inscribed inside the human.

In my approach, I cite that there is a wake in the discourse of traditional taxonomies of the human, the lyricized nonhuman, which emerges and reflects gaping holes in the discourse of an anthropomorphic universality of being Man, the idea of the idealized, over represented figure Man, taken from a colonial and then biocentric frame. Wynter insightfully points out how others have and are always exceeding the limits of this tightly and rigidly constructed form of personhood.

Autopoietic Turns

One of the ways in which Wynter also approaches ideas of life in Latin America is through her coopting of the somewhat opaque term “autopoeisis” taken from Chilean scientist Humberto Maturana and Francisco Varela’s views on perception, the self, cognition, and neurobiology. For Wynter, seeing Man is an autopoietic act, an image replicated by a culture-specific lens, which is reproduced on a neurobiological level. Wynter’s prose, particularly with regards to an autopoietic turn, is dense, and, at times, disorienting, as her turns of phrase, at times, twist into a seemingly impenetrable labyrinth. I am less concerned with some of the more mystifying neurobiological points Wynter pursues.

Instead, I will reference here selected arguments about “autopoiesis” to orient my readings, specifically through the ways in which Wynter’s approach to genres of the human is informed on both an autopoietic and diasporic stage. My specific intervention in these concerns is this: I locate autopoiesis between Wynter’s revolutionary reframing of human and race and place it together with the possibility for reading autopoietically in the field of literary studies. To do this, I will give a brief overview of the term, “autopoiesis” in several of its many varied contexts.

Originally, the term emerges chiefly from the book Autopoiesis and Cognition: The Realization of the Living (1972) wherein Chilean scientists Humberto Maturana and Francisco Varela establish a way of viewing life that functions as a kind of feedback loop. It bears mention that what Maturana and Varela were initially postulating is not about autopoiesis as Wynter reads it for race, nor as sociologist Niklas Luhmann did for social systems, neither in a literary sense as it has recently been studied, but rather on the self-reproducing processes of life and cognition. For Maturana and Varela, this meant engaging a nonlinear, circularity of form, structure, and how their interdependent components function in an interconnected ways as part of a holistic structure. This feedback loop that maintains the living system can be influenced by events in the living system’s environment. As Varela notes in Principles of Biological Autonomy:

An autopoietic system is organized (defined as a unity) as a network of processes of production (transformation and destruction) of components that produces the components that: 1. through their interactions and transformations continuously regenerate and realize the network of processes (relations) that produced them; and 2. constitute it (the machine) as a concrete unity in the space in which they [the components] exist by specifying the topological domain of its realization as such a network (13).

This works through a biological framing of cognition, which parses how cognitive processes function through beings as living systems as well as the origins of humanness. I propose that in addition to their intriguing contributions regarding the roots of humanness, there is another interesting strand to be taken up from Maturana and Varela’s approach—which is their approach to a systematic description of organisms as self-producing units in physical spaces or “domains” as sets of relations, interactions, worlds, and identifications. Living systems can be translated into other environments, if they can survive it, however the nature of this internal loop endures.

When speaking about diaspora as a concept, I defer to these concepts as my guiding vision or orientation. While Maturana and Varela tie systems to more strictly machine-like processes, I meditate on the possibilities of an animistic view in my discussion. Maturana’s ideas, of cognition, space, and environment also rely on the presence of an observer and how he witnesses and defines livelihoods. This is something which Wynter put particular emphasis on in terms of how to forge humanness and how racial otherness are constructed together with the praxis of living.

Contemporary, interdisciplinary, critical tendencies in reading autopoiesis blur sciences and humanities, nature and culture, and have deployed the term autopoiesis in new directions. It bears mention, before moving on to more contemporary scholarship on the term, that Maturana’s autopoiesis also carries with it the shadow of Latin American livelihoods that are disrupted. Autopoiesis and Cognition: The Realization of the Living emerges just months before Chile’s military coup; later, Maturana stated the following posterior reflections, which are a rather complicated series of views on Pinochet’s interventions in the nation:

Permítanme una reflexión sobre lo sucedido en los últimos meses en la historia de Chile. Al mismo tiempo pido disculpas porque la hago como biólogo que no está en condiciones de hacer una evaluación histórico político económica. Yo pienso que lo que ha pasado en relación al plebiscito de 1988, muestra exactamente lo que he dicho sobre el lenguaje como un aperar en coordinaciones de coordinaciones de acciones. En 1973, cuando se produce el golpe militar, la Junta de Gobierno afirma que tiene la intención de generar una democracia. Los que escuchamos no creemos, porque nos parece que las palabras no se ven confirmadas en los actos. Pero el discurso de intención democrática se mantiene. En el proceso se nombra una comisión constitucional que eventualmente escribe un proyecto constitucional que, modificado de una u otra manera por Pinochet, se aprueba en un plebiscito. Se comienza a hablar de leyes electorales, de leyes de partidos políticos, de procedimientos electorales. Es decir, se genera una trama de conversaciones para la democracia que constituye una red de acciones. Lo que pasa el 5 de octubre de 1988, día del plebiscito presidencial, no refleja seguramente el deseo de Pinochet, pero ocurre. ¡Ocurre porque el gobierno no lo puede detener! Ocurre porque la red de conversaciones, la red de coordinaciones de acciones generada en el proceso de los discursos y debates sobre la democracia y la legalidad democrática, constituyen una trama de acciones que no se pueden evitar, porque no existe el espacio de conversaciones en el que surjan las acciones que lo hagan. ¡No, ésta no es una reflexión superficial a posteriori! Las conversaciones, como un entrelazamiento del emocionar y el “lenguajear” en que vivimos, constituyen y configuran el mundo en que vivimos como un mundo de acciones posibles en la concreción de nuestra transformación corporal al vivir en ellas. Los seres humanos somos lo que conversamos, es así como la cultura y la historia se encarnan en nuestro presente. Es el conversar las conversaciones que constituyen la democracia lo que constituye la democracia. De hecho, nuestra única posibilidad de vivir el mundo que queremos vivir es sumergirnos en las conversaciones que lo constituyen como una práctica social cotidiana en una continua conspiración ontológica que lo trae al presente (Emociones y lenguaje en educación y política 64-5).

It is important to recognize how Maturana views the idea of how language, potentiality, and continuous conversations that constitute our ontological condition, which he places after what might be called somewhat of a stylized Pinochet-apologia. Though he excuses himself as a simple biologist, Maturana’s ideas here, like autopoiesis, have far-reaching implications. In a separate interview compiled in the text Del ser al hacer: los orígenes de la biología del conocer with Bernhard Pörksen, Humberto Maturana describes a chilling luncheon with Pinochet which he attended with some 85 other professors and intellectuals during the dictatorship. Maturana notes that, “Cuando llegó mi turno de saludar a Pinochet, me acordé de mi hijo mayor que había dicho que jamás le daría la mano a Pinochet. Y ahí estaba yo apretándole la mano a ese hombre” (206). Maturana was a man of many paradoxes; during this encounter with Pinochet, he gives a slightly subversive toast in which he celebrates Chile, patria, and cultural autonomy. Maturana notes that this pleases the former dictator such that he claps four times enthusiastically and that the toast served as common ground for a return to dignity and civility between the two.

At the same time, as Maturana recounts this experience to Pörksen, he states that “por supuesto este hombre es criminal. No cabe duda” and that “sigue alegando su inocencia, y ese es su mayor crimen” but that a neutral dialogue was the only viable path forward nonetheless in such circumstances (209). It is important to recognize both the potential promises and possible problems of Maturana’s views and how geopolitical events and upheavals may have shaped these perceptions. Maturana’s work, nevertheless, reminds the reader of the importance of with mediating uncertainties and surviving, with all its shifting meanings, as ontological practices.

My reading of autopoiesis pursues the term as a part of useful framework that explores the complicated, semi-autonomous nature of forms. In this dissertation, I read autopoietically as a way to approach the porosity of human/nonhuman signs in Latinx and Latin@American poetry and performance. On the possibility of reading poetry through an autopoietic lens, poet and essayist Erena Johnson has also noted the importance of underscoring how this “semi-autonomous loop” functions. In “Making Meaning With and Against the Text: An Autopoietic Theory of Reading”, Johnson writes that:

Semi-autonomy does not just describe how the material book moves about in the world, but describes how the poem is open to its environment in every line. While formal qualities seem to delimit the text, give it boundaries – a certain number of pages, block of paragraphs, or certain numbers of lines, titles, codex form – these same qualities ensure the text is open to its outside: all the other editions or copies of that text, all the allusions, quotes, references to other texts, all other texts that have used 14 syllable lines, all texts that seem to deal with similar subject matters. Any animate force which operates in an autopoietic system should be understood as all edges, all interfaces (18).

Johnnson’s approach to poetry is shaped in part by Ira Livingston’s Between Science and Literature: An Introduction to Autopoetics, a pioneering work that riffs on autopoiesis mainly through literary and cultural theory, resonating with my own quest to pursue autopoiesis in poetry and critical theories of the nonhuman. I find the ways in which Livingston approaches autopoiesis and the idea of boundaries which are foundational to the term, particularly useful for how I conceive of reading nonhuman forms as places or intensities of passage:

Boundaries do more than produce closure by keeping certain things out and others in; they also allow traffic that they channel and manage. But they do more than allow traffic: they create traffic by producing differentials between sides of boundaries, thus also producing more openness (flow across boundaries where none had been before). Finally, one has to acknowledge that boundaries and the autopoetic systems built around them do more than create traffic: they are traffic (84).

From this, we can understand that boundaries, in an autopoietic lens, and the act of reading poetry is not comprised of discrete limits. In my close-readings of contemporary Latinx and Latin@American poets I test these boundaries, of text and of nonhumanities. After all, as Livingston notes:

We are fractal creatures, crazed through and through with cleavages. If you look closer at a feature that seems firmly in the interior, you are likely to find the hairline fracture, the edge, that joins it to the outside. To cultivate this way of looking— to learn to see performativity— you really just have to follow through on the mandate to look at nouns and structures until you see them as participles and processes: an edge is an ongoing negotiation rather than a structure; or to take it from the legalistic to the ludic, the party was going on before the guests showed up (83).

Like Livingston’s citation of fractal creaturehood, Erena Johnson too approaches environment and animate forces, in an Aristotelian sense; however, her approach to autopoiesis allows us to reconsider the potentialities in poetry—how to read in a semi-autonomous nature, both with and against the possibilities of the poem, noting the manifold passages of its signifiers. I draw their voices together with an example from Johnson’s idea of an autopoietic cloud gathering force:

Let us explain the semi-autonomy of a poem again, in a more dynamic model. Imagine an atmospheric cloud consisting of all sorts of different winds moving in different directions. They float around slowly, their different moisture contents and different temperatures mingling and transforming their speeds and directions. That these winds swirl around as undifferentiated potential make the atmospheric cloud a continuum. This cloud is the environment of a poem, the continuum out of which the poem emerges. It is made up of the forces of marketing departments who regulate texts by genre, the publishing houses and chains of distribution, the cultural legacy of the writer’s other works, the public events which may have an effect on the subject matter of the poem at its time of reading, the power of interpretations that issue from authoritative sources, the author’s presence within media outlets…the large forces in the world that seem to be any poem’s “background”. Suddenly, a gust of wind sweeps through the atmospheric cloud. A reader has picked up the poem, and beings to map it with her habitual interpretative strategies. At the very same moment, another gust is sweeping through from a different direction. The poem’s formal qualities are travelling at a contrary speed with a contrary temperature. The two winds collide and twist together to form a storm. Some of the slower winds that were drifting about in the atmospheric cloud get pulled into the mix (22-3).

Johnson is pursuing a reading of the poem as an event; however, some of the “winds” she twists into this cloud, which is the environment of the poem, are elements that I also analyze in this dissertation. I seek to trouble the inside / outside nature of nonhuman forms and signs as ways of navigating between Latinx and Latin@American poetry and performance, where these limits lie, and how these texts are packaged. How do they flow in, out, and around canonical boundaries and the borders of the human (as Johnson writes “who regulate texts by genre, the publishing houses and chains of distribution, the cultural legacy of the writer’s other work”)?

A final bridge between Johnson’s work, my concerns, and the field of global black studies comes from her reference to Jack Halberstam’s “The Wild Beyond: With and for the Undercommons” from The Undercommons: Fugitive Planning and Black Study edited by Stefano Harney and Fred Moten. Johnson highlights where Halberstam, who is discussing Moten’s approach to sound, writes about the autopoietic edge, and how, “When we listen to music, we must refuse the idea that music happens only when the musician enters and picks up an instrument; music is also the anticipation of the performance and the noises of appreciation it generates and the speaking that happens through and around it, making it and loving it, being in it while listening” (Halberstam 9). Johnson defers to Halberstam as a way to approach autopoietic processes; specifically, toward an autopoietic reading of poetry that “does not only arise and dissolve at the moment of engagement and disengagement – the picking up and putting down of a book”, but one that is rather informed by an amalgamating, semi-autonomous set of relations (Johnson). However, notably, Halberstam’s point of departure is black studies and “the wild” (he writes that “Moten and Harney want to gesture to another place, a wild place that is not simply the leftover space that limits real and regulated zones of polite society; rather, it is a wild place that continuously produces its own unregulated wildness” 7). This is perhaps where autopoiesis and critical nonhuman readings from Black and Latinx studies meet yet again. In this dissertation I read autopoietically between these disciplines, human and nonhuman intensities, and canons, through a variety of techniques.

Autopoiesis is the overarching framework that weaves implicitly throughout my chapters. It is self-referential in a nature, sensitive to its environmental reshapings, and the inside/outside of texts, which are evidenced through my approaches tononhuman signs that connect canons (chapter one), techniques of self-portraiture and collaging through poetry (chapter two), landscape and environment (chapter three), and how to read both through a text which undoes itself in form and legibility and to disrupt apparent stasis in poetic texts (chapter four).

Poetic Pursuits and Navigations

Just as there are a range of theoretical voices which fade in and out this semi-permeable, semi-autonomous project, so too, a panorama of artists, poets, and writers have been woven into this dissertation. Though it is impossible to privilege or center all of them, they are present. It was very difficult to select just a few poets for this project from the myriad voices and talented writers who are currently forming a contemporary Latinx and Latin@American renaissance of letters. Many writers and poets shaped this dissertation; inspiration came from prose from Justin Torres, Guadalupe Nettel, Salvador Plascencia, Eduardo C. Corral, Helena Viramontes, to name a few. Though they may not figure in its individual chapters; they shaped its vision. Several poets prominently formed my approach, which I will detail here below.

To write this dissertation, I followed María Meléndez into the landscape poetics of How Long She’ll Last in This World?; through “Backcountry, Emigrant Gap”, “Good News for Humans”, “Controlled Burn,” and especially the poems, the “Life Study Site: Bodega Natural Reserve”, inspired by the life of Margaret Murie, and “Aullido”, the codeswitching Sierra Madre story of an invincible wolf.

Firstly, “Life Study Site: Bodega Natural Reserve” reads as a vision, a quest through landscape:

I have a particular co-pathy

With this particular coastal prairie herd,

Because we’ve been under the same saffron spell

Of a hill of bush lupine in bloom,

And they’ve watched me step through

the drifting drapes of fog they’ve stepped through (68).

And:

The eye seldom sees

what the mind does not anticipate—

shock is a tool to slice revelation

into the mind, into the grass, onto the once-

were dunes: my husband’s accidental death

unveiled a world of unknowables

still, as I continue following the trail

of questions that we built together here.

I often forget (hill-blind,

were-dunes-blind,

vision striated by grasses)

the nearness of the pulsing sea. (69).

María Meléndez’ speaker, like Wynter, presses the reader’s senses, the eye, to work through visions on the edge of the human-nonhuman boundaries. Her poem, “Aullido,” asks us to conjure “El alma de un lobo” that “nunca desaparecía de este mundo”, which is forged in the memories of mountains that transcend borders and speak to myth, “living wolf, spirit in flesh, / breathe here, / walk here / recall the places / you never left / Glance again in time’s long mirror / and recognize yourself” (22). Meléndez’ evocation of flesh, myth, and nonhuman boundaries as conduits for self-reflection resonate with my first two chapters, while shifting landscape visions and spaces resound with chapters three and four.

The second collection of poems, which I found particularly influential and would be remiss to exclude from this introduction is Daniel Borzutzky’s The Performance of Becoming Human. The freshly minted National Book Award Winner (2016) The Performance of Becoming Human approaches hazy boundaries not only of nations, going from Chicago, to Lake Michigan, Valparaiso, Chile and back, but of humanity and how we forge or perform it. To orchestrate this performance of becoming human, Borzutzky unflinchingly collages imageries of dictatorship and the disappeared with the swipe of a CVS card, neglected voicemails, the Frito Bandito, “overdevelopment” and its wake of destitution. Borzutzky’s hymn to the limits of the human also underscores, and I suggest, might serve as a bridge between what Wynter, Maturana, and Acevedo have framed too. I see Borzutzky’s work as drawing together the autopoietic insides and outsides of the porous human form, between spaces, with this looming burden of how contemporary Latinx and Latin@American poets speak and respond to these limits.

Alongside this “performance,” The Performance of Becoming Human also playfully riffs on genre, which is another way, perhaps, of considering the writing process and genre as in genres of humanity—of how and why we write, scratch out, the human/nonhuman and Other. The Performance of Becoming Human returns to the core of literature’s capacity to reshape perceptions of life with Borzutzky’s steady hand pressing into the poet and how he packages humanity’s limits for literary consumption. Borzutzky accomplishes this through a technique, which, though, at times reads as playful is ever dauntless in its rigor, that addresses how literary voices approach these limits of human life for artistic production. Consider the titular poem, “The Performance of Becoming Human,” which reads:

On the side of the highway a thousand refugees step off a school bus and into a sun that can only be described as “blazing.”

The rabbi points to the line the refugees step over and says: “That’s where the country begins.”

This reminds me of Uncle Antonio. He would have died had his tortured body not been traded to another country for minerals.

Made that up.

This is a story about diplomatic protections (14).

The flippant tone, the delineation of bodies, minerals, and migrants as boundaries coupled with the resounding, deadpan, “Made that up” establish Borzutzky’s speaker as one who is always penetrating and undermining the boundaries of the poem itself through self-referentiality, an autopoietic value, and one I will later pursue through ideas of collage and self-portraiture. Borzutzky’s dissonant “imagination challenges”, which he poetically interjects further this idea:

Imagination challenge #1:

Imagine there is a matzah-ball bandito in your house. You buy lots of matzah balls and mix them with jalapenos and Fritos and light them on fire and then you survive the apocalypse because Fritos can stay lit forever and you don’t need to find kindling or any of that other stuff so you finally have time to study Karlito Marx while watching Manchester United’s Mexican hero Chicharito Hernandez score a poacher’s golazo in the waning seconds of the Carling Cup while eating hallucinogenic mushrooms while watching Eric Estrada on Chips on another screen and listening to a podcast of the Book of Leviticus on your iPod Touch while Skyping with your mom while sexting with your boyfriend who works for the secret police.

Write a sonnet or a villanelle about this experience and do not use any adjectives (22).

Imagination Challenge #2:

It’s nighttime. You’re decomposing in a cage or a cell. Your father is reading the testimonies of the tortured villagers to you. He is in the middle of a particularly poignant passage about how the military tied up the narrator and made him watch as his children were lit on fire. He has to listen to the screams of his blazing children but he cannot listen to their screams so he himself starts screaming and then the soldiers shove a gag in his mouth so that he will stop screaming, but he doesn’t stop screaming even with the gag in his mouth.

But these are not screams, actually. They are unclassifiable noises that can only be understood as a collaboration between his dying body, the obliterated earth, and the bodies of those already dead.

Write a free-verse poem about the experience. Write it in the second person.

Publish it some place good (23).

Borzutzky drives toward and against the limits of life itself, “the collaboration between his dying body, the obliterated earth, and the bodies of those already dead,” together with the young writer’s mandate to, “Publish it some place good.” Through his imagination challenges, Borzutzky subverts these calls to the writer to nail bare life to the page, to the break of the line, for artistic consumption. These are concerns which have shaped my dissertation; how do the intensities between human and nonhumans in poetry and performance shape ideas of text between the Americas considering the valences of life across many forms. How do we read these signs, and how does this tendency contribute to questions of literary production at large related to ideas of canon and beyond?

These Chapters, Twice A Lunar Day

This dissertation as a collection functions in a constant ebb and flow between literary interventions and theoretical tendencies. Each chapter reflects a different point in this tide. Chapter One—“Natalie Diaz, Duende, and Dreamtigers,” underscores nonhuman energies and centers poetic texts’ approaches to canonical figures, mainly through Federico García Lorca and Jorge Luis Borges and other-than-human interlocutors in Natalie Diaz’ poetic collection: When My Brother Was an Aztec. To situate this chapter in this elliptical tide, it is important to note that it is, relative to its neighboring chapters, nearly devoid of outside theoretical interventions, which functions as an act of centering the text.

“Collaging Kingdoms,” Chapter Two, in comparison, relies heavily on the theories which overtly frame this dissertation. I read poet Aracelis Girmay’s engagement with ideas of blackness, hispaneity, and the apparent bareness or not of life through concepts of collaging and assemblage. This chapter draws heavily from the neighboring field of Global Black Studies and includes readings from Wynter and Weheliye, while also cycling back into close readings from Diaz’ text When My Brother Was an Aztec to scrutinize collaging, myth, and self-portraiture alongside the nonhuman.

Chapter Three addresses how poets Maurice Kilwein Guevara and Ada Limón write through shifting landscapes and frame from the American backlands, Appalachia. These pursuits are underpinned by Latinx and Latin@American literary hunts and nonhuman referents.

Chapter Four, “How to Read in a River Without Water Damage” engages with performance artist Basia Irland and how she positions what she calls Hydrolibros and Icebooks. These Icebooks are frozen forms of texts which are dissembled through the force of the bodies of water, which surround them. In this chapter, the reader can visualize how texts are assembled and undone by nonhuman intensities. As a counter-reading and point of conclusion and extension, I offer the poetic text Milk and Filth by Carmen Giménez Smith. Milk and Filth addresses the ephemeral body-earth performance art of Ana Mendieta, turning performance to text: another edge from which to recut the initial concerns of how Basia Irland’s texts feeds into performance and the culmination of our autopoietic considerations.

CHAPTER 1

NATALIE DIAZ, DUENDE, & DREAM TIGERS

I lied about the whales. Fantastical blue water-dwellers, big, slow moaners of the coastal.

I never saw them. Not once that whole frozen year.

Sure, I saw the raw white gannets hit the waves so hard it could have been a showy blow hole.

But I knew it wasn’t. Sometimes, you just want something so hard you have to lie about it, so you can hold it in your mouth for a minute how real hunger has a taste. Someone once told me gannets, those voracious sea birds of North Atlantic chill, go blind from the height and speed of their dives. But that, too, is a lie.

Gannets never go blind and they certainly never die (92).

– “Lies About Sea Creatures,” Ada Limón in Bright Dead Things.

Canonical Crossings, Interspecies Inquiries: An Introduction.

In the opening discussion of Migrant Imaginaries: Latino Cultural Politics in the U.S.-Mexico Borderlands, Alicia Schmidt Camacho writes that “this is a book shaped by struggle, by the efforts of migrant people to assert their full humanity in border crossings that confer on them the status of the alien, the illegal, the refuse of nations” (1). Schmidt Camacho foregrounds her accomplished study of transnational movements in the very stakes I wish to explore in my examination of nonhuman forces in Latin@American poetry and performance. However, in a critical swerve away from Schmidt Camacho, this dissertation critiques Latin@American and Latinx Studies theoretical engagements with how human and nonhuman encounters are deployed in poetry and performance as signs and spaces of regenerative possibilities. Through nonhuman interlocutors, I interrogate ideas of diaspora, canon, text, and performance in a drive away from the juridical idea of “full humanity” by looking toward how humans and nonhuman discourses possess border transcending qualities.

What is particularly interesting to me, are the instances when Latinx and Latin@American poets and writers, instead of opting to diametrically oppose the presence of nonhuman interventions and rhetoric—submerge themselves in strategies of nonhuman discourse to reach beyond the merely comparative, wielding nonhuman figures to question ideas of life itself and also to articulate their positions within hemispheric exchange and certain dominant discourses. These moments where “the human” has not been enough allow the critical reader to acknowledge that, then, if this is so, we must look, with the artist, to the edges, the insides and outsides of this form. These ideas necessitate that readers of contemporary Latin@American literature and performance examine, the edges and porous perimeters, to paraphrase Caribbean theorist Sylvia Wynter, of humanity and away from Man.

I consider these larger social justice foregroundings with regard to diasporic Latin@Americanity while approaching this chapter, “Natalie Diaz: Duende and Dream Tigers”, given, firstly, the nature of the way Diaz positions her work as having a particular preoccupation with US-Mexican Southwest as a place of exchange coupled with her explicit commitments to activism and indigeneity. This chapter, “Natalie Diaz: Duende and Dream Tigers” suggests that reading nonhuman figures in When My Brother Was an Aztec offers the critical reader a glimpse into places of passage not only between humans and nonhumans but between the Hispanist canon and its margins. These ontological places of traffic trouble ideas of crossing, not only in their connections and disconnections between continents and canons, but also to and from the edges of the lives of Others.

This chapter focuses on a close reading of nonhuman forces in the poetry of Natalie Diaz, together with considerations for cultural and political formations other than Man. This reading is viewed through the exchange between certain canonical Hispanic figures and Diaz’ border poetry, which I read through the nonhuman signifiers. These nonhuman, border forces, which I will be scrutinizing in my close reading of Diaz’ When My Brother Was an Aztec are, chiefly: the author’s engagement with the concept of “duende”—taken from her larger conversations with Federico García Lorca, a pillar of the Spanish and Western lyrical tradition—and Diaz’ connections and disconnections with Jorge Luis Borges and his bestiary forms.

Myths of Man and Other-than-human Origin Stories

Other-than-human forces abound in poet Natalie Diaz’ striking 2012 collection, When My Brother Was an Aztec. Diaz crafts lyrically complex mythscapes whose backdrops are the landscapes of borderlands’ indigenous reservations. Inhabitants of these landscapes include world-making, figures ranging from Eve to Huitzilopochtli, Antigone, a tortilla creation origin-story, to the very last Mojave Barbie. In name alone, within, When My Brother Was an Aztec we find the invocation of pre-Columbian deities in a contemporary setting. In the book’s title poem, the speaker describes her brother (whose drug addiction serves as a principle thread in this book) as an Aztec-god “half-man, half-hummingbird” with a “swordlike mouth” (Huitzilopochtli) and his tenuous position between life and death. He “lived in our basement and sacrificed my parents / every morning. It was awful” (1). These nonhuman presences and the tension between life and death (or a lack of the fullness of life) are established from the very inception of the collection and drive its meditations. Consider the nonhuman titled poems, “The Elephants,” “When My Beloved Asks ‘What Would you Do if you woke up and I was a Shark?’”, “Self-Portrait as a Chimera,” “Mariposa Nocturna,” “Formication (sensation of insects or snakes running over the skin)”, “Zoology,” “The Clouds are Buffalo Limping Toward Jesus,” “Reservation Grass,” “The Gospel of Guy No-Horse,” “Abecedarian Requiring Further Examination of Anglikan Seraphym Subjugation of a Wild Indian Rezervation,” and, of course, “A Wild Life Zoo” (the final poem which bookends this collection). Nonhuman referents monopolize the majority of titles and poetic content of this substantial text, comprised of just over 100 pages filled with long and dense lines, which are compressed, lyrical gems.

The title poem, “When My Brother Was an Aztec,” harkens to the reconfiguration of voices of indigeneity; a concept that is built into the foundations of US-Mexico border literature, advocacy, and ideas of crossing. One might pause to consider foundational texts from the Chican@ movement—the work of poets Gloria Anzaldúa and Cherrie Moraga come to mind—both of whom employ nonhuman imagery together with indigenous mythscapes. The weight of the Chican@ and Latinx canon in the U.S. informs my approach to reading these terms and Diaz’ work. For instance, Iread Natalie Diaz’ use of “Aztec” and the past tense “was”, while considering the precedent set by another canonical Latinx text, My Father was a Toltec: and Selected Poems (1988; 1995) by Ana Castillo. In the preface to her collection of poems, Castillo writes, “Hark! the Toltecs live! Not the distinguished Mexican people who were already myth at the time of the Conquest. But the Toltecs of Chicago” (xvii). Castillo’s father was a Toltec, a member of a gang made up of predominantly Mexican and Mexican American transplants living in Chicago; the poems work between ideas of family, struggle, language and endurance—framed with the complicated shadow of an explicitly displaced, unconsolidated, and redirected indigeneity, much like Natalie Diaz’ When My Brother Was an Aztec.

Alongside ideas of indigeneity and traffic, mythical, otherworldly figures emerge. From a Hispanist stance, one which also informs my approach to reading Latinx and Latin@American texts, the importance of the idea of myth, as Roberto González-Echevarría has observed at length in his notable publication Myth & Archive (1998), has been fundamental to the emergence of and approach to Latin American narratives.[1] In this chapter I’d like to speak about the presence of myth and the nonhuman not in the most literal manner (though there are countless references to Greek gods and goddesses and nonhumans, which are unavoidable in Diaz’ volume), but rather, what I am driving towards, is to demonstrate how nonhuman forces might shape or redirect our readings of texts that are in flux between Latinx and Latin@ America. The nonhuman forces that shape the poetry in this collection work to reshape places of exchange where cultural histories, schisms, literary masters, and forces of life are negotiated. Diaz grapples with myriad ideas of life-forms, and in this way establishes a rearticulation of life, text, hemispheric readings, and Man.[2]

In this chapter, I’m scrutinizing Diaz’ work as part of a larger line of inquiry, which ponders how certain minority writers, whose work has fallen outside the realm of idealized forms of Man, reconfigure nonhuman forces and vibrancies to reflect other livelihoods or points of exchange. How does nonhuman figures travel, specifically between a minority border narrative and canonical Hispanic works and what new considerations might this offer for rethinking exchange between these regions? What does it mean to critically approach nonhuman presences when these forces are wielded and redirected by those, like many indigenous groups with whom Diaz claims solidarity, have figured outside the realm of idealized forms of humanity or myths of man, remaining relatively marginalized?

The particular “Myth of Man” that I’m gesturing to is of “man” as a homogenous ente, which, as I have established in my introduction, is one of the most compelling formulations I seek to challenge through the discourses of Caribbean theorist Sylvia Wynter. This myth of Man is one of a tabula rasa consciousness of what it is to be human; the misstep that asserts that access to the fullness of humanity and its rights (citizenship, livelihood) fall outside of race, racial discourse, or colonial hierarchies. Discounting this oversight is one of the most pernicious slips that inhabits contemporary discussions of the critical non- or post- human.[3] I’m not suggesting a comparative reading of Man and the nonhuman, or to suggest that the category of human is to be somehow overcome by drawing attention to this. Rather, I’m looking here at the ways in which Diaz channels nonhuman forces as ways to rearticulate narratives that cross through canons and which are based from the realm of marginalized spaces. How might these strategies function as moves away from Man and toward other ideas of life from the margins? As Alexander Weheliye comments in Habeas Viscus: Racializing Assemblages, Biopolitics, and Black Feminist Theories of the Human, “…What different modalities of the human come to light if we do not take the liberal humanist figure of Man as the master-subject but focus on how humanity has been imagined and lived by those subjects excluded from this domain?” (8). Poet Natalie Diaz destabilizes a reliance on Man as the central or default figure for depicting life on the reservation; opting in many instances to rely instead on nonhuman presences to portray the struggle between life, death, addiction, family, tradition, poverty, creative consciousness, and erotic love. Diaz combines mythical elements from a variety of disciplines, but lends particular and marked attention to Latin@American cultural referents, and canonical authors who appear as recurring touchstones, and are connected, specifically, through a series of turns and throughout the collection’s three, lengthy, sections. Diaz troubles Mojave and Mexican legacies of indigeneity and contemporary lived experiences in relation to the Hispanist canon through nonhuman frames and figures, disquieting the telling of history, lineage, family, and the idea of livelihood. The presence of nonhuman figures offers the reader another crossing over; an alternative route or form to destabilize normative ways of reading multicultural Hispaniety and displacing the “myth” of a homogenous border experience or hemispheric set of relations.

In an interview with the National Book Critics’ Circle, Diaz reflected on her cultural identities and the role of myth and truth. Diaz comments on this tension and on her roots, alluding to several elements which comprise the lyrical thrust of her work—family, myth, history, tribe, and identity.

I was raised to hold many truths in my hand, all at the same time, and to never have to drop one in order to have faith the other. This is the beauty of growing up in a multicultural family. Our capacity for identity is large. I am many. Even though most people use the word ‘myth’ to speak of our tribal stories, we see them as truth. So, for me, myth has always been the truest truth. The word ‘history’ on the other hand, we question (González).

Diaz continues, clarifying the use of Spanish and Latin@American referents in her work, as it is derived from a variety of lived experiences, family inheritances, and the importance of language:

My grandparents are from the north of Spain, Asturias and Oviedo. We grew up hearing them speak Spanish, and I ended up playing basketball and living in Spain, where I learned to appreciate the language more. Though my grandparents are Spanish, we have many Mexican relatives. My mother is native, from two tribes, but our language was a dying language, and so not spoken at home. It wasn’t until I began to work with my Elders that I began to learn Mojave […] On a side note, my father says that because he is Spanish and my mother is native, all of his kids are Mexicans. He is joking, of course, but in this area, and especially in the area of language revitalization, we have a very strong tie to the word indigenous, which includes many of the peoples indigenous to the Americas. We often work together, on both sides of the border, to help protect and save our heritage languages (González).

Diaz possesses what I read here as a less than linear relationship to border latinidad, having triangulated several borders and seemingly crossed none. She is both of the Southwest, identifying as a Native American writer and also Spanish with extended Mexican heritage and a commitment to border politics, language, and culture. Diaz, in this interview and throughout her body of poetic work, troubles an all-consuming or singular formulation of rootedness. In addition, Diaz’ work, rather than emphasizing fixed origins of belonging, works more in a relational, rhizomatic sense, which recalls the following line from Édouard Glissant’s Poetics of Relation, in which “each and every identity is extended through a relationship with the Other” (11). When My Brother Was an Aztec as a text has been autopoietically shaped by these interstitial environments and referents. Chican@ theorist and poet, Gloria Anzaldúa has defined this type of borderland edging as a kind of contact zone, which is a larger, multisensory phenomenon. She writes, “The physiological borderlands, the sexual borderlands, the spiritual borderlands are not particular to the Southwest. In fact, the Borderlands (with a capital B) are physically present wherever two or more cultures edges each other […] where the space between two individuals shrinks with intimacy” (19). It is important to clarify these distinctions when discussing, as I will in the continuation of this chapter, Diaz’ readings of Mexican iconography, Spanish lyrical & dramatic forces, and Argentine narrative figures. As Walter Mignolo has noted, “The ‘bicultural mind’ is the ‘mind’ inscribed in and produced by colonial conditions, although diverse colonial legacies engender dissimilar ‘bicultural minds’” (Local Histories/Global Designs: Coloniality, Subaltern Knowledges, and Border Thinking 267). In my reading, Diaz offers an indirect route between sites of exchange amid letters, histories (mythological, colonial, and lettered), which is shaped by nonhuman presences that pass between continents, shifting and exceeding human forms through their exchange and as the chief line of inter-continental and interspecies inquiry.

The Light in Lorca, the Beast in Borges

Natalie Diaz through her inclusion of larger-than-life legendary figures highlights not only sublime symbols from Greek and Aztec traditions, she also weaves in exceptional literary figures from the Latin American and Spanish canon in her negotiations of life on the reservation. Her chief examples from the Hispanic canon, to whom she returns repeatedly, are, Federico Garcia Lorca and Jorge Luis Borges—through the ideas of duende and the bestiary respectively.

Through Lorca, the edges of the human are exceeded through the idea of duende—an intensity that Diaz both names explicitly in her poems and one that implicitly permeates the collection. Lorca’s theories around the term, which he developed in: Teoria y juego del duende (1933) centered around a kind of altered state of creative consciousness which is in flux between life and death. It is a black, mysterious, stirring force that literally roots itself, which possess and fills the artist, shifting his consciousness:

Y Manuel Torre, el hombre de mayor cultura en la sangre que he conocido, dijo, escuchando al propio Falla su Nocturno del Generalife, esta espléndida frase: “Todo lo que tiene sonidos negros tiene duende.” Y no hay verdad más grande. Estos sonidos negros son el misterio, las raíces que se clavan en el limo que todos conocemos, que todos ignoramos, pero de donde nos llega lo que es sustancial en el arte. Sonidos negros dijo el hombre popular de España y coincidió con Goethe, que hace la definición del duende al hablar de Paganini, diciendo: “Poder misterioso que todos sienten y que ningún filósofo explica.” Así, pues, el duende es un poder y no un obrar, es un luchar y no un pensar (45).

Duende is a creative act that comes up through the artist’s physical body, whose arrival always means a radical change in forms as these human limits are lapsed. These radical changes in form are driven by the conception of duende as an alternative kind of power, an affective and animating force; a vigor, which seizes the artist and his public. The term itself “duende” in translation has multiple interpretations; it can conjure images of the figure of a gnome or goblin-like being, a thorny place that presents obstacles to passage or where it is obstructed, a spirit of disorder. Notably though, from this quote is the fact that Lorca also associated the idea of duende with blackness and the idea of Souths. He writes (restating what the guitarist Manuel Torre claims) that everything that has black sounds in it has duende. Lorca linked duende to Gitana culture and blackness in his native Southern Spain, and notably meditated upon this again during his time in Harlem, New York when encountering blackness in America, although, markedly to an occasionally to a fetishizing degree. Duende, then, is a complex term. It is not only a creative impulse that defies normative ideas of the fullness of creative life by its necessity to approach death, but that, also, just as weighty is duende’s configuration as a racialized, placed, and transplanted, semi-autonomous term. Duende approaches the fullness of creative life and nearness to death brimming with black sounds and with passage. Duende and blackness’ coupling as an embodiment of creativity and its detachment from life, is an important consideration for our larger discussion of marginalized discourses in the Americas, for which blackness (a question central to Weheliye’s and Wynter’s work, whom I’ve previously cited) is often excluded. The blurred boundaries between life and death, human and beyond, parceled with critical considerations of race can become passages between worlds and continents, lives and non-lives, creative genius and its bewitched mythos inspirations.

Reading terms like duende, which tie together these ideas, creates conduits and alternative ways of reading exchanges between the cultural histories. Blackness’ presence vis-à-vis duende alongside Spanish, indigenous, and border poetry is a kind of diasporic trifecta which encapsulates three of the central driving forces of Hispanic colonial past and present. Duende is a nonhuman force that travels across the Americas (Lorca in Spain, Argentina, and Nueva York) and through Diaz’ narration of a Southwest epic tragedy.

These references to duende (beyond normative life between death and eros) gain prominence in the second and third sections of Diaz’ collection, and alongside it, emerge references to the other literary giant I mentioned earlier: Jorge Luis Borges, and his bestiary. At continuation, I will discuss, first, the ways in which Diaz encounters Borges, using this understanding of duende and form, together with an acknowledgment of Diaz’ penchant for mythmaking, as prefaces with which to approach a selection of poems. I will move between Lorca, Diaz, and Borges through nonhuman interlocutors as a way of critically engaging When My Brother Was an Aztec’s many zones of encounters and environments.

The Beast and The Stone - Blue Tigers and Form

The second section of Diaz’s book centers around the disarming of a family home by way of the speaker’s brother’s drug addiction and his impending death (real and/or imagined)—the driving theme of this collection. The homestead, Diaz writes, is like a wild zoo, where the beasts are not beasts. They are “our children painted like hyenas,” (“Zoology” 88). In this poem, the speaker is driving further towards a beastlike existence, while at the same time approaching a kind of death and darkness, pulsed with the rhythms of duende—a force that I will explore further and that will gain strength as the text builds. First, let’s turn to the idea of beasts and bestiary.

In the masterful poem, “How to go to Dinner with a Brother on Drugs,” the brother is itching under the weight of his Day of the Dead skeleton suit. These manifested “formications” (which is also the title of a subsequent poem), the need to scratch as if insects were in or under the skin, is a repeated image associated with drug abuse and a trancelike state. After several costume changes, the speaker consoles herself, writing, “Be some kind of happy he didn’t appear dressed/as a greed god—headdress of green quetzal feathers, / jaguar loincloth littered with bite-shaped rosettes / because you’re not in the mood” (46). The poem alternates between evocations of myth and nonhuman imageries, then moves to reiterate, again, visions of the speaker’s family home, as “zoo,” a “misery museum”, and an “Al-Qaeda yard sale” (47). These images of family dysfunction and addiction are interspersed, again, with references to larger than life figures (chupacabras, a Minotaur, Merlin) but ultimately, they are pinned down by the idea of nonhuman shape-shifting.

This brother fades from “a Cheshire cat” to “a gang of grins”; his skin transforms into a desert, “a migration of tarantulas moves like a shadow / over his sunken cheeks” (49-50). The instance of this I’d like to focus most closely on is the following passage that moves between this nonhuman shifting and a harkening to Jorge Luis Borges.

He spent his nights in your bathroom

With a turquoise BenzOmatic handheld propane torch,

A Merlin mixing magic then shape-shifting into lions,

And tigers, and bears, Oh fuck, pacing your balcony

Like Borges’ blue tiger, fighting the cavalry in the moon, (48).

On the following page a reference to Borges’ approach to creaturehood is reiterated and mirrored back. Diaz continues, “Look at your brother—he is Borges’ bestiary. / he is a zoo of imaginary beings.” (49). I will first examine the case of the blue tiger in an example from Borges’ work, before moving to this second instance from Diaz, in both of which nonhuman and human forms are transcended and travel between hemispheric referents.