Portrayals of Female Empowerment in Shōjo

Info: 8920 words (36 pages) Dissertation

Published: 10th Dec 2019

Tagged: ArtsLiterature

How is Female Empowerment Portrayed through Motifs of Gender-bending and Anti-Heteronormative Characters in Shōjo

Table of Contents

- Introduction 3

- Context A 3

- Context B 5

- Chapter 1 : Sapphire in Princess Knight 8

- Graphic Conventions in Shojo Manga 8

- Visual Representation of Sapphire 10

- Sapphire’s Gender Identity 10

- Chapter 2 : Oscar in Rose of Versailles 13

- Visual Representation of Oscar 13

- Body Politics in Rose of Versailles 14

- Relationship with Andre 15

- Chapter 3 : Utena in Revolutionary Girl Utena 16

- Visual Representation of Utena 16

- A Romantic Connection with Anthy 17

- The Anti-Damsel-in-Distress in Utena 17

- Chapter 4 : Analysis. 19

- Conclusion 22

- References 24

- Images 24

- List of Figures 35

- Bibliography 36

Introduction

Shojomanga has been my introductory material to romance, sexuality and female identity in my pubescent years as well as a vital part of my transition to adolescence. Like many of my other female friends, we are educated in the ideologies regarding the female perspective of romances and gender discrimination in which the implications in the development of the female shojo characters are discussed. Aside from films and novels, shojo manga are one of the major factors in shaping my identity as a female heterosexual today.

Despite the preconceived reputation of heavy sexism and portrayal of female subjectivity in shojo manga and subculture, there are also many that rebel from the norm of utilizing distressed female protagonists and regular heterosexual relationships in romances by implementing gender-bending and anti-heteronormative elements in their stories. In a heavy patriarchal society existing in Japan and rest of east Asia, this is a major breakthrough for many mangakas[1] to promote gender-equality awareness, anti-sexism, and female empowerment for many young adult women in the age of exploring their own female sexual identity. In this essay I will discuss and analyze themes and signs of gender-bending roles in characters and narrative structures that challenge heteronormativity through a collection of iconic shojo manga –– Princess Knight, Revolutionary Girl Utena, and Rose of Versailles–– that has challenged conventional gender roles and in the process promoted post-feminism to young adult female readers.

Context A : Japanese Woman Pay Gap

Japan is the third country in the world with the widest pay gap between men and women. According to Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, on average women in Japan are earning two thirds of the income received by the male counterparts ( OECD, 2015) and there is lack of female supervisory roles and underrepresented in many leading roles. Japan has long working hours therefore it makes it difficult for both female and male counterparts of the family to maintain equal care commitments to the household. In reference to Yurika Nishiyima’s essay, women in Japan are usually given clerical and secretarial positions that reflect on traditional housewife chores in the Asian household such as running errands and serving tea to male co-workers (Nishiyima, 2016) . A few years ago, women in the office were not usually given promotions to managerial positions as common as the male counterpart. Although this reflects on serious gender-inequality issues and female subversive roles in the society in Japan, many changes have been made drastically over the years to minimize these issues however it is still not equal.

Context B : Shoujo Manga and Social Change

The word “Shojo” directly refers to “young girl”. This is the direct opposite definition of shonen which directly translates to “boys”. “Shojo” further portrays a character that “personifies desirable feminine virtues”, embodying elements of kawaii[2], naiveté, and sexual immaturity” ( Sasaki, 2013). Despite shojo manga has a large diversity of styles, they embody certain aesthetics dominated by images of puffy dresses, flowers, school uniforms and girls with large and sparkly eyes inked in innocence and naiveté.

The culture of shojo began to grow through articles and stories written by men under a male-dominated government in the pre-war era. During the Meiji Restoration after the year 1868, Japan declared westernization as the goal of their country and pursued to segregate gender and sex in the society by regulating people’s dress and appearance, in which Japanese men followed western clothing and women remained in traditional Japanese attire. This was part of the Meiji Civil Code, which emphasized women to pursue roles of being a “good wife, wise mother”, restricting their freedom in terms of career options in society. Despite the upheld heterosexual norm in that period, same-sex romances between girls in an all-girl’s school were “an accepted means of delaying heterosexual experience until girls were old enough for marriage.” ( Sasaki, 2013) This is a particular element of romance that may seem as unconventional and anti- heteronormative in current shojo stories today.

Major social changes in Japan began to occur near the 1970s; there were transformations in the industry, a major shift in the employment structure, and a declining birth rate. Women were given a major opportunity to progressively challenge gender roles and the previously model identity of “ good wife, wise mother”. There were liberation movements such as the Iman Ribu which was lead by Mitsu Tanaka in the 1960s ( Abbot, 2015 ). Tanaka ‘s famous anti- patriarchal manifesto called “Liberation from the Toilet” strongly condemns a male-centered family system and societal obstacles for women in the Japanese society. She particularly empathizes “toilet” as a symbolism of women being the receptacle of male sexual desire. ( Abbot, 2015). Her manifesto aims to push the independence of Japanese women and claims that Japanese economic and political structure at the time made survival without a man’s financial support impossible for women. The time of progression allowed female authors to dominate the manga scene and develop elements of shojo manga into a genre that we know of today. The progression enabled the repressed gender to explore female subjectivity and discuss controversial topics regarding gender politics and sexuality. Such topic regarding gender non-conformity and female sexuality explored during the time gave birth to the BL culture , or Boy’s love manga, which is an subgenre of shojo manga embodying sexually graphic stories of romances between young androgynous-looking beautiful boys. Many mangakas[3] also began depicting female characters in fantastical spaces embodying and displaying controversial characteristics such as cross-dressing, acting as the opposite sex or participating in non-heterosexual romances.

The themes of females pursing ambitions in shoujo manga through gender-bending characteristics and rebelling against the heterosexual norm share similar experiences with the Takarazuka Revue Theatre. The rebellions at the theatre were a sign of gender defiance that provoked more women writers and mangakas to promote female dominance through gender-bending stories and debate on issues of female subjectivity and sexuality in magazines and manga. The Takarazuka Revue theatre was an all-female kabuki [4] company established in 1913 when the government allowed actresses back to stage after being banned in 1629. Although the ban was lifted, the founder of the company, Ichizou Kobayashi, believed that the displays of masculinity on female actors outside the context the kabuki productions were abnormal and obscene. Gender regulations relevant to the Meiji civil code “ good wife, wise mother” were enforced on the company, requiring the actresses to maintain long hair, be unmarried, heterosexually inexperienced and actresses play male characters were provided with male head wear. Many otokoyakus [5]rebelled against the patriarchal control by expressing their male persona offstage through the use of male-gendered terms of “I” ( “boku” in Japanese ) and you (“kimi”) in their words. ( Sasaki, 2013). Following the occurrences, a nationally publicized case of the suicide of two homosexual females, one of them was a famous Revue actress, brought debates of female sexuality and gender norms onto the surface for many writers. These elements of gender-bending and challenges to the norms of female sexuality can be traced in manga Rose of Versailles by Riyoko Ikeda and Princess Knight by Osamu Tezuka.

Chapter 3: Sapphire in Princess Knight

Whenever you ask about a gender-bending manga that made a prominent footprint in the history of Japanese comics, the manga Princess Knight ( A.k.a Ribbon no Kishi in Japanese) by Osamu Tezuka would be mentioned. This revolutionary manga was published in 1967 by shojo publishing company Kodansha, aimed for young readers around the age of nine to thirteen years. The lead character of the story is Sapphire, a girl with two souls : a boy and a girl. Born into a royal family, Sapphire is forced to lead an incognito life as a prince in order to inherit the throne of her kingdom and lived as a princess in secret. Throughout the story, Sapphire is met with obstacles which prevent her from achieving her dreams. A prince from another kingdom falls in love with her as a girl but dislikes Prince Sapphire without the knowledge of Sapphire’s existing two co-habiting souls. Antagonists Duke Duralumin and Sir Nylon try to reveal her identity and assassinate her throughout the story in order for his son, Plastic to yield the throne of her Kingdom. While the Angel Tink tries to retrieve her boy heart in order to return to heaven, the Devil Witch endeavors to steal Sapphire’s heart for her daughter to become more feminine, and marry Prince Franz, whom Sapphire loves, for wealth.

Graphic Conventions in Shoujo Manga:

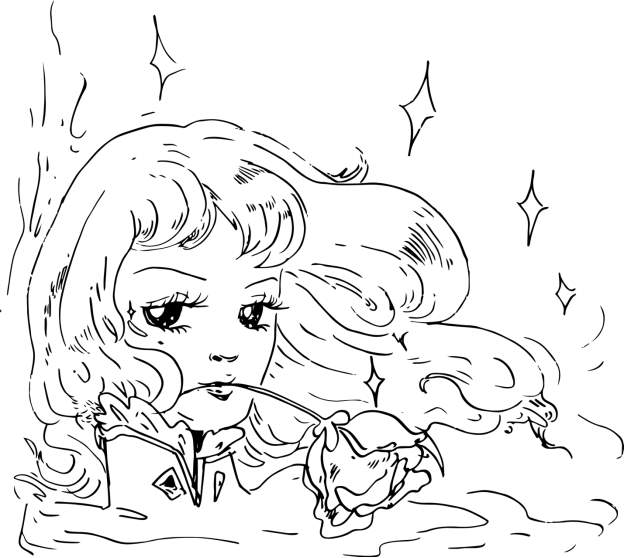

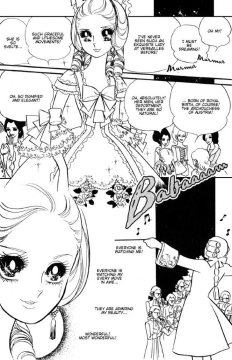

The graphic conventions generated throughout the shojo manga history make it possible for mangakas[6] to create unrealistic representations of their characters. This is deeply contrasted with the realistic backgrounds and props that are recreated or inspired by real-life scenes, predominantly from European culture and architecture. In contrast with the realism in the background and props, shojo characters are composed of unrealistic features that can be identified by their eyes, legs, body shape and hair. The most distinct features are the eyes of many shojo characters. The eyes are often portrayed doll-like with the features extremely exaggerated by the elongated curly eyelashes, excess of dewy and sparkly details on the surface of the eyes and the enlargement of them, most of them taking up a third of their faces, which is evident in Figure 7 (p.26). The second feature is the body shapes of many girls. The body shapes in shojo manga are created to suit acknowledged beauty ideals of the time that manga was published. A common “idealistic” body shape recreated in many shojo series embodies slim waists, extremely long slim legs, long arms, and medium-sized bosoms. The last feature would be the hair as the many characters are portrayed with flowy, shiny and voluminous hair, and dyed in light colors. These conventions help create the physical distinction of an androgynous character and the looks of the main female protagonists with gender-bending qualities among the society’s accepted appearances of men and woman.

Visual Representation of Sapphire:

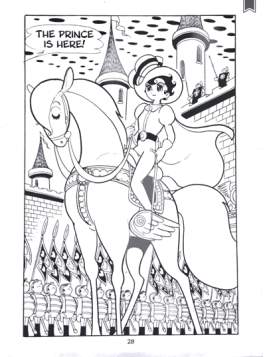

The female protagonist Sapphire displays gender-bending aspects by dressing up as a boy when she is a prince. Due to fact the doctor of her royal family had mistakenly announced the sex of Sapphire to the citizens as a boy, Sapphire had to dress as a prince in public instead of a princess. As seen in the Figure 1( p.24), Sapphire is dressed in male-medieval-like attire, which is evident by the tight leggings, belt pendant and puffy shoulder pads worn by men in the medieval times. Unlike the realism of the backgrounds in the manga, the main and background characters are not close-to-life which is a common graphical detail in many shojo series. Using this obscurity and unrealistic method, Tezuka is able to illustrate the distinction between the looks of each characters easily. The female characters in this series are depicted with voluminous blonde hair with a more petite body shape, while Sapphire is characterized with a tomboyish haircut, black and slightly curled. She has large sparkly eyes with long lashes which is similar to the portrayal of female background characters in the story. The portrayal of Sapphire’s character was more feminine compared to the illustration of male characters. Tezuka may want to convey the character’s stronger lenience towards the female sex than to male sex in the story.

Sapphire’s Gender Identity

At a young age, Osamu Tezuka was exposed to the concept of the performance as the opposite binary gender from attending Takarazuka Revue Theatres, which was the first all-female theatre group in Japan, with his mother who was an avid patron of the troupe (McNeil, 2013). Despite the controversies leaked from the company regarding the female oppression of behavior and expression, female empowerment conveyed through the male roles in their plays inspired Tezuka to create a narrative of a female trapped in the spectrum between a male and a female gender and the implications the character faces as a binary gender in a patriarchal society.

Since the beginning of the story, Sapphire was born into the world as a female with both souls of boy and a girl. The two souls could be interpreted as the equivalent of the masculine and the feminine gender. While the idea of non-binary genders exists in our society, the context of Princess Knight only serves in the concept of binary genders. Since Sapphire embodies both masculine and feminine qualities, she tries to survive in her Kingdom as a prince utilizing her masculinity while concealing her femininity. Tezuka’s Sapphire serves as a stage for his readers, which were a majority of young girls and women for this series, to experience channeling both qualities of the binary gender through his perspective.

Within the plot of Princess Knight, Sapphire struggles to decide whether to keep her boy soul and her girl soul, or as interpreted, feminine and masculine qualities in Tezuka’s developed microcosm based on his values of gender. These struggles could be perceived as Sapphire’s confusion over her own gender identity.

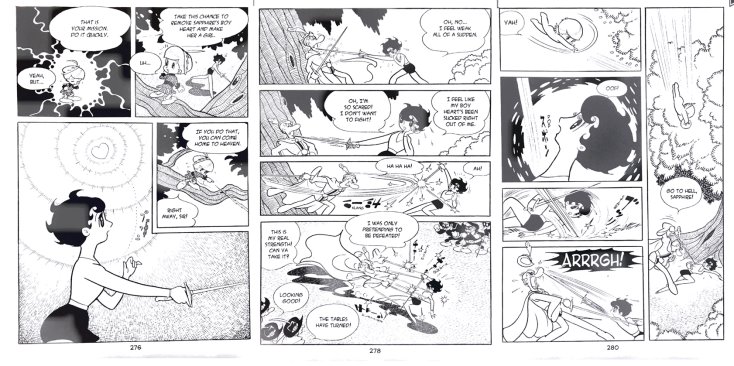

Firstly, I will discuss examples of Sapphire’s masculine quality of the dilemma. In Figure 2 (p.24), Sapphire reacts weakly to the loss of her boy heart and loses her strength to combat her enemy until she receives the heart again. This shows that the loss of her masculine qualities has made her inept in combat and less desirable to be a girl for her as hinted clearly in Figure (p.25). In Figure 3(p.25), Sapphire temporarily lost her girl heart and finds Prince Franc’s confrontation of her true identity as a woman to be an aggressive “insult” ( Tezuka, 1967). Interestingly, in those two scenes, one of the qualities of masculinity equates to confidence. Figure 2 (p.25) and Figure 3(p.25) is well-contrasted by the confidence of Sapphire. In Figure 2, Sapphire with her girl heart loses her confidence to fight back whereas as the Sapphire with the boy heart gains the confidence to contest with Prince Franz. According to Chris Mautner of The Comic Journal and Rebecca Silverman of Anime News Network, these details presented in Sapphire’s character were considered as “sex[ist]” and conformed to the “misogynist ideals of 1960s Japan” ( McNeil, 2013). On the other side, Sapphire faces the opposite side of the dilemma when it comes to her love for Prince Franz ( Figure 4, p.25) and her desire to dress in a woman’s attire as well ( Figure 5, 25). Despite the lack of confidence shown as a girl, Sapphire desires to be attracted and pursue her love for Prince Franz. This quality of female attraction and heteronormative relationship conforms to the society’s accepted means of being the feminine gender. In the last panel in Figure 6 (p.25), Sapphire confronts that she “truly wishes to be a girl at heart” but desires to dress “as a man” as well, indicating qualities of a tomboy ( Tezuka,1967).

Sapphire’s ambiguous gender identity well resonates with Simone de Beauvoir’s words: “One is not born a woman, but becomes one.” (Butler, 1990) In her quote, Beauvoir argues that the concept of gender is socially constructed rather than a fixed trait that may alternate over time for the individual. As the story progresses, Sapphire learns about her masculine and feminine qualities, which are manifested by the norms of being a woman in the 1960s, and fights against the limitations set as appropriate in her world. Sapphire may have been born with female sexual organs, but grows up with the choice to experience both masculine and feminine qualities. It has shaped Sapphire to not be the typical submissive character but a female who does not need to follow her society’s expectations of being a “princess” or a “prince”. The following characterization of Sapphire serves as an empowering model for many young girls and women to subvert society’s norms and roles. Especially in Japan, it has given young girls a chance to envision themselves out of the role of “a proper lady” and a “good wife, wise mother” in the 1970s.

Chapter 2: Oscar in Rose of Versailles

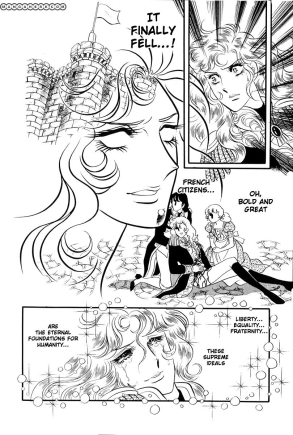

The Rose of Versailles was written by Riyoko Ikeda and was published in the 1970s, which is a few years after Tezuka’s Princess Knight. This manga series is also an important impact on the characterization of female protagonists in the shoujo manga industry. The manga weaves in a handful of historical elements that help develop the depth of the main female protagonists’ character and a rich background for the story. The lead character is Oscar, who is born and raised to become the next general of Marie Antoinette’s Royal Guards in order to inherit her father’s position. Despite Oscar is a woman, she still wears the male military uniform and with her androgynous beauty, she attracts more women than the men can in court. During her service to Antoinette, she realizes the social inequality between the commoners and the wealthy, and in result, resigns the Royal Guards to join the political revolution to overthrow aristocracy. This leads her to fighting with anti-royalists and is shot dead after the fall of the Bastille. The series concludes with the execution of Marie Antoinette and King Louis XVI for treason.

Visual Representation of Oscar :

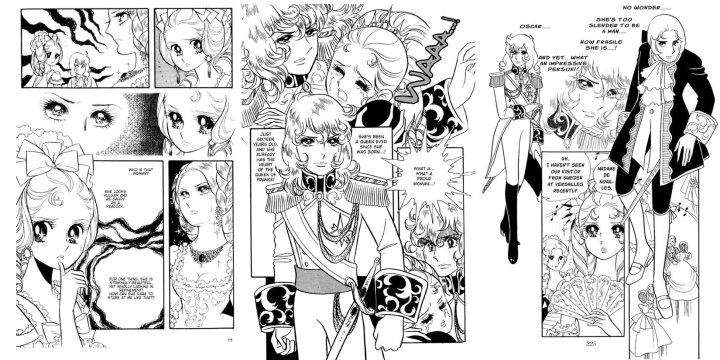

Given by the shojo graphic conventions, Saito has illustrated Oscar as an androgyny which became a visual inspiration to the development of many characters in shojo manga industry, predominantly in BL manga, and to mainstream media. Oscar’s appearances contain both masculine and feminine attributes; therefore, considered as an androgynous female. Like many female characters in shojo manga in the 1970s, Oscar had doll-like eyes with thick curled eyelashes and dewy pupil surfaces ( Figure 8, p.26), along with wavy blonde hair. There are features that make Oscar an exception from the rest of characters in the story. Oscar has similar doll features (Figure 8, p. 26) on her face like other females in the series, however, her eyes are not as big as theirs, neither in the shape of an oval in the male characters ( Anan, 2014). She has eyebrows thicker than the female’s but not as thick than a male’s in Saito’s style of illustrating her characters. Oscar’s height (Figure 8, p. 26) towers above her female friends and levels on the same height as her male colleagues in the Royal Guards. As appointed to be one of the Royal Guards, Oscar cross-dresses in a male military uniform, containing epaulets and gold medals, to appear more masculine in her world. Like Tezuka, Saito has depicted Oscar more to look more similar to other females in order to articulate her natural sex. Despite Oscar’s natural sex, her choice to take on the masculine look and role exudes her freedom from society’s constraints on gender norm. ( Anan, 2014)

Rose of Versailles in 1970s Japan :

According the author Ikeda herself, this manga Rose of Versailles was deliberately made in response to the Japanese women’s liberation movement, where the participants persisted to free women’s bodies from political constraints and fight for more possibilities (Anan, 2014). In the story, Ikeda has placed the French Revolution as a part of the plot to represent the “inner revolution of the Japanese women” in the age where there were limited opportunities in careers available to them (Anan, 2014). The manga represents as a rebellious message against the status quo of female gender roles being in lower positions than men’s in career and confined into responsibilities of a housewife. The manga also takes inspirations from the famous Takarazuka Revue theatre and their pro-feminist protests occurring within the company. Overall, Rose of Versailles serves as an input for young readers to critically engage towards the gender conventions and limitations of their regime.

Body politics in Rose of Versailles

There are several examples where Ikeda nonspecifically discuss body politics into her plot, and conveys her dissatisfaction over the current gender conventions in the 1970s. The setting placed in the time period where sexism is appropriate, class system is highly valued and also heteronormativity is only accepted. For one instance, Oscar expressed anger when she was completely disrespected by soldiers in battle because she was a female. In another scene, Oscar rejects her father’s intentions of marrying her off to another male aristocrat for that “it was about time. At a party held for her potential spouses, Oscar expresses her defiance by showing up in military attire and flirtations with other females at court (Figure 9, p.27) . Lastly, Oscar’s fight ( Figure 10, p.27) against the royals and the aristocrats in the French revolution signifies her desire to be independent from the sexist values and genders norms. The situation correlates with Beauvoir’s claim on the body: “ the body is a situation” ( Butler, 1990, p.11), body should be the site of freedom–– figures body as a mere instrument or medium for which a set of cultural meanings.

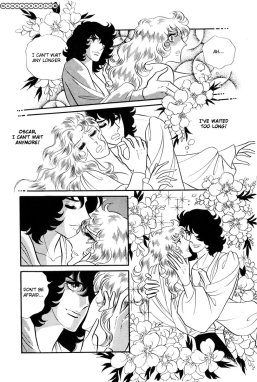

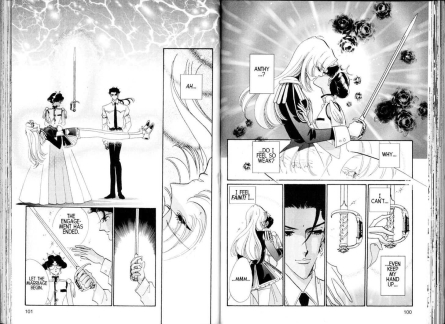

Relationship with Andre

Many shojo series feed young readers with a romantic relationship between the protagonist and a supporting character as an extension to the main plot of the story. In Rose of Versailles, Oscar develops a romantic bond with her male lover Andre, who also shares similar physical features with Oscar. Although the relationship between Oscar and Andres is technically heterosexual, the intimate scenes between them “exudes homoeroticism”(Anan, 2014). In the illustration of their sexual activity in Figure 11 (p. 28) , the nudity is minimal and the display of Oscar’s female genitals is avoided; the absence of Oscar’s bosom leads to the perception of their relationship to be homosexual rather than heterosexual. It also highly defines Oscar’s appearance as androgynous, especially in Figure 12 (p.28), both character share similar physical features that are of the graphical construction of an androgynous characters from the Boy loves sub-genre. Ikeda’s homoerotic illustration of Oscar’s romantic bond is a breakthrough from the socially accepted heteronormative relationship in the 1970s, encouraging young girls to explore their sexuality outside of the box, not necessarily on the idea of love, but questioning femininity, and its primal instinct to attract men for biological purposes.

Chapter 3: Utena in Revolutionary Girl Utena.

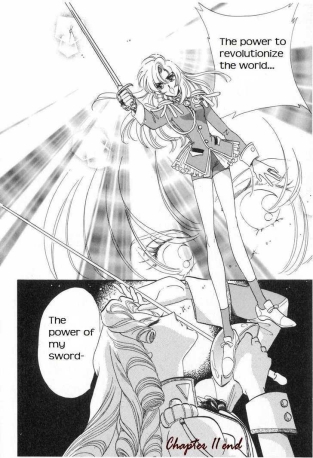

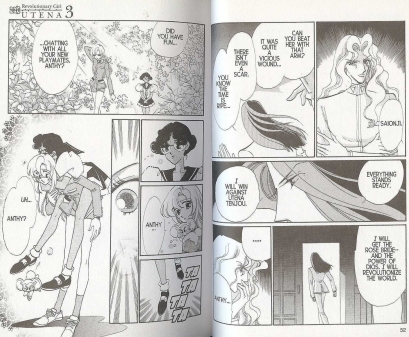

Revolutionary Girl Utena ( or known as Shoujo Kakumei Utena ) is one the most successful creations by Chiho Saito, who is part of female collective called Be-Papas, known for their famous Sailor Moon creator Naoko Takeuchi. Published in 1997, the manga drew a lot of attention for its dynamic plot and charismatic gender-bending main female protagonist Utena Tenjou and her subtle romantic relationship with her female partner Anthy Himenmiya. The story begins with Utena’s ambition to find her prince, who saved her from drowning a river when she was a child and as impressed by his bravery and strength strives to become a prince like him. She transfers to Ohtori Academy in efforts to seek of her Prince and during the search she wins a duel against a member of the student council with miraculous powers called “Dios:”. As a result, the Rose Bride––Anthy––of the duel and of the student council community becomes within Utena’s possession without prior knowledge to the battle. Utena seeks to find the truth and the link between World’s end and the power of “Dios”, which is most sought after. Utena challenged in a series of sword duels and the winner of all duels will receive the “power to revolutionize the world.”

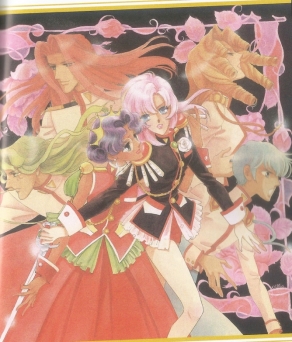

Visual Representation of Utena Tenjou:

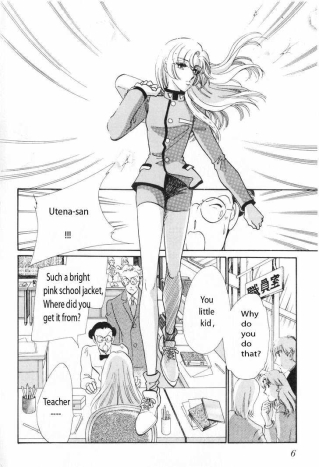

Unlike Oscar from the Rose of Versailles, Utena is not depicted as female with strong androgynous features. Saito has illustrated Utena with the body of the female girl with physical facial features similar to other girls in the story, considered to be feminine. For example, Utena shares similar feature of having large sparkly eyes, but is differentiated by Anthy’s slight slanted detail near the outer ends of the eyes. That slanted feature in Anthy’s eyes suggests a hint of submissiveness and vulnerability which are ubiquitously regarded in the stereotypical shojo character. She has characterized her as girl who wishes to be dressed in a mixed combination of a male uniform and a girl’s skirt as seen in Figure 13. (p. 29) Utena chooses to wear the school’s male uniform with ambitions to be a “prince” of her own. In Figure 14 (p.29), Utena is seen to be frequently dressed in a military uniform accessorized by epaulets, braiding, and brass buttons, possibly embodying the role of a knight, which is usually assumed as a role given to men. Utena could be recognized as a tomboy, which Judith Halberstam from Female Masculinity defines it as “an extended childhood period of masculinity” and… “teds to be associated with a ‘natural’ desire for the greater freedoms and motilities enjoyed by boys” (Hurford, 2009). Body-wise, Utena is serialized with long slender legs, medium sized bosom and oval faces, which pertains to the society’s ideals of body image as suggesting in fashion magazines and the majority of the body images given off from photos of celebrities. Utena appears to be taller than most females in the plot, including Wakaba and Anthy but shorter and smaller than the majority of males such as Touga. Despite Utena’s body image may reflect upon beauty conventions, the outfits Ikeda has designed for Utena differentiates her from typical shojo protagonist in dresses.

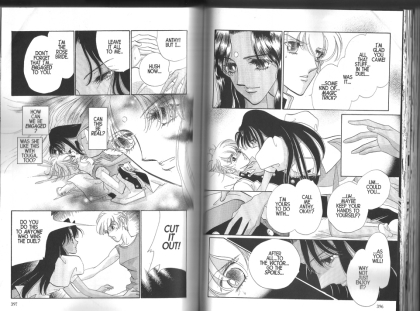

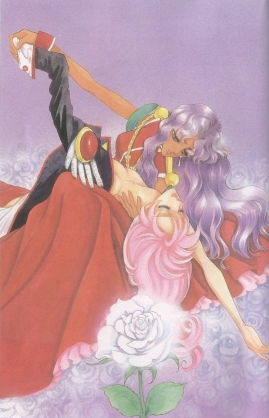

A Romantic Connection with Anthy

Saito allows her readers to experience a same-sex romance between the protagonist Utena and the supporting character, breaking away from heteronormative stereotypies in the shojo genre. In Revolutionary Girl Utena, Anthy and Utena share a close friendship bond that gradually leads to a subtle romantic relationship that is not shown in text but illustrated. This is evident in Figure 15 (p. 30) and Figure 16 (p.30) where Anthy and Utena share several kisses non-romantically, however Utena reacts to those kisses seriously on her account. In Figure 17 (p.31), Anthy openly shows affection towards Utena and occasionally flirts with her like in Figure 18 (p.31). Despite Anthy’s flirtatious advances, Utena tries to maintain a platonic relationship between them. Near the ending of the series, a slight hint of romantic connection is inevitably generated between them. Not only is this shown in the story, the homoeroticism is exemplified in many of the Saito’s poster art and illustrations, which is shown in Figure 19 (p.32), accompanying the series. The same-sex romantic connection between Anthy and Utena only serve as an example for young readers to reevaluate their sexuality and their gender identity.

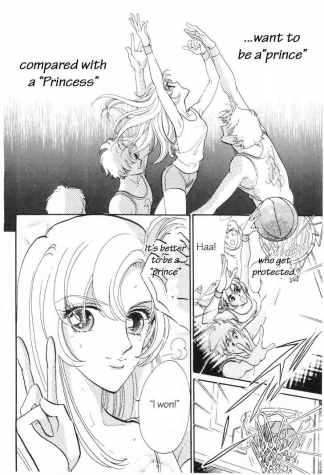

The Anti-Damsel-in-Distress in Utena:

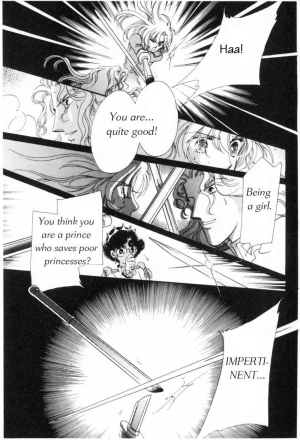

In many shojo manga series, the typical female protagonist becomes the damsel-in-distress like in many fairytale-oriented stories. In Saito’s vision, Utena is the opposite representation of this stereotype (expanding the boundaries of a woman’s capabilities with their bodies and independence.) Instead of being rescued, Utena determines to be the rescuer. Utena was rescued by a prince when she was a young child and from that experience, she was inspired to be her own prince to help others. In Figure 20 (p.33),Utena’s desire to be a prince serves as an inspiration for many other readers and writers to debate on the possibilities a woman can be aside from socially accepted roles. In Figure 21(p.33), During a duel with Saionji, Utena is offended by his comment stating that “[ She] is quite good, being a girl.” and doubts her ability as “prince to save poor princesses” . Despite its sexist intonation, the socially acknowledged views of a princess and a prince is stated here. Unlike the positive attributes of a prince, princesses are perceived as “poor”, weak, and dependent on the others. Princesses also usually falls into the role of a female and asserts itself to feminine qualities, which are assumed to idea of beauty and vanity. In Revolutionary Girl Utena, Utena’s position as a prince empowers readers to avoid falling into stereotypes that involve submissiveness and dependence, and encouraging them to explore careers that are considered socially unfit for their natural sex.

Chapter 4 : Analysis

The female protagonists I have chosen for this essay all consist of similarities that contribute to signs of gender-bending and anti-heteronormativity in advocating female empowerment. Firstly, all characters are cross-dressed in chivalrous roles like knights and reverses the traditional role of a damsel-in-distress. The motif of cross-dressing in these characters also lead to anti-heteronormative notions. Lastly, they share experiences that establish a connection to Judith Butler’s ground-breaking theory from Gender Trouble.

Cross-dressing is a major component that evidently channels female empowerment to readers through the character’s roles in all three manga series. Sapphire, Oscar and Utena cross-dress in male outfits suitable for combats and flexible movement in their addressed time periods. Their actions in the stories also lead to chivalrous acts and pursue to change the archival codes of moral behavior that are acceptable for different genders. These motifs imply the authors’ intention of subverting gender roles and norms embedded in the regime of our society. All the female protagonists’ social position as a prince or a knight encourages women from the 1960s to the 1990s to pursue careers and identities outside of the consolidation of fundamental morals and beliefs originating from the societal construction of “good wife, wise mother”.

All characters embody cross-dressing, gender-bending, and anti-heteronormativity motifs. These motifs seen in the characters are inspired from philosopher Judith butler’s theory of performance in gender:

“Gender is the repeated stylization of the body, a set of repeated acts within a highly rigid regulatory frame that congeal over time to produce the appearance of substance, of a natural sort of being.” (Butler, 1990, p.45)

In other words, Butler has also rephrase her theory that “ [ People] act and walk and speak and talk in ways that consolidate [ a society’s] impression of being a man or being a woman.” and the s and Although all the characters are portrayed as females, their outfits and their actions may not consolidate the impression of a woman. By societal norms, “the repeated stylization of the body” and the “set of repeated acts” regarded as feminine is reflected by history. Primitively, women were educated to be biologically successful. To achieve heteronormativity, women are conditioned to attract men utilizing the influences of socially accepted beauty standards and etiquette. Many shojo stories are influenced by the Meiji Civil code construction of “good wife, wise mother”, creating female protagonists and characters that are stereotypically submissive, dressed in accordance to fashion and followed etiquettes accepted as “feminine “ by society. As opposed to the Sapphire, Oscar and Utena, their actions and cross-dressing does not correlate with femininity. This serves as a critical reevaluation of between the relationship of the female sex and heteronormativity, indicating that women can break away from this norm and choose to be something that is not considered feminine. Moreover, femininity is not innately connected to the female sex because it is a social construction created by “the repeated acts”.

Despite the manga Princess Knight, Rose of Versailles, and Revolutionary Girl Utena are iconic examples of female empowerment that have influenced many shojo authors, there are still an abundance of protagonists in shojo manga that befit the submissive, petite and heteronormative stereotypes in the current industry. Many of these romantic series narrated in high school settings, making it relatable to for secondary female students in the same environment. Personally I have read these a couple of times myself and only primarily enjoyed the illustrations made in the volumes. One example is Strobe Edge by Lo Sakisaka. Strobe Edge follows a stereotypical shojo plot where the main female protagonist Ninako falls in love with her high school crush Ren, and pursues to remain a friendship with him despite her love for him. In the plot, Ninako is visualized as a slim, petite girl with sparkly big eyes resembling a doll ( Figure 22, p.34). Ren is illustrated as a tall, dark haired boy with a nonchalant expression on his face ( Figure 23, p.34) . Like many other shojo stories, Ninako pursues for a heteronormative romantic connection. As this is intended for a young female audience, it is evident that achieving a heterosexual romantic relationship with their male crush is the epitome of their fantasies. The loss of gender-bending and anti-heteronormative notions in these shojo manga has failed to encourage young female readers to realize female empowerment and the politics surfaced on the female body.

Conclusion

Shojo manga plays a major role in defining the identities of many young girls in east Asia, and some in western continents. According to Yukari Fujimoto from her book Where is my place in the world? in 1998, she considers shojo manga to be a medium for woman, a form of text that displays the values of women, especially in the ideology of romance (Monden, 2015). There are many shojo manga that feed into the stereotype of illustrating romances in the perception of insecure and submissive female protagonists in school-life narratives. These narratives guide young female readers to how to dictate their love life either if it is mutual or unrequited. In Princess Knight, Rose of Versailles and Revolutionary Girl Utena, the romance in their stories are not as emphasized but placed secondary to the plot. Unlike many stereotypical shojo manga series, these manga have identified their characters as cross-dressing girls with ambitions of breaking heteronormative ideals in fantastical settings. The characters are more multidimensional; they are not submissive, petite, or passive but embody attributes considered masculine. Throughout the stories of these manga, the female protagonists are faced with struggles of personal identification in the society, indicating the importance of romance as secondary to all.

Many shojo author often revoke feminine qualities by means of challenging conventional gender norms. The attributes of gender-bending and anti-heteronormativity evident in Sapphire, Oscar and Utena inspires the young audience to reevaluate their identity as a female in a patriarchal society. Cross-dressing is a vital component in defining these attributes. It implies the subversion of gender roles and allows the readers to experience the life of a female character embodying a masculine role or identity. The Anti-damsel in distress quality in these characters is another component for this equation. Instead of being rescued, the female protagonists are the “princes” who rescue their supporting characters. There is also a hint of homosexuality illustrated in the connection between Utena and Anthy, implicating heterosexuality as an old-fashioned norm.

Butler’s claim that gender is a social construction, a performance of “repeated stylization” and “acts” serves as an influence to the gender-subversive qualities manifested in these characters. It questions the existence of gender and of the distinction between masculine and feminine qualities. Especially in a male-dominated environment in Japan, despite numerous gender equality reformations, many women are still confined to domestic chores and career positions lower than their masculine counterparts. Although these characters are serialized in series published before the millennium, more and more young women are becoming aware of their society limitations that have been built from phallocentric values. Along with Butler’s theory, it suggests that heteronormativity and the existence of feminine qualities were to benefit the males in society; thus, “the body should be a site of freedom” as claimed by Beauvoir (Butler,1990), and it should be free of norms, such as femininity and heteronormativity that was set by cultural meanings.

References

Images

Figure 1 : Osamu Tezuka, 1967, Princess Knight, Kodansha

Figure 2 : Osamu Tezuka, 1967, Princess Knight, Kodansha

Figure 3 : Osamu Tezuka, 1967, Princess Knight, Kodansha

Figure 4: Osamu Tezuka, 1967, Princess Knight, Kodansha

Figure 6 :Osamu Tezuka, 1967, Princess Knight, Kodansha

Figure 5 : Osamu Tezuka, 1967, Princess Knight, Kodansha

Figure 7 : Riyoko Ikeda, Rose of Versailles, 1979, Kodansha

Figure 8 : Riyoko Ikeda, Rose of Versailles, 1979, Kodansha

Figure 9 : Riyoko Ikeda, 1979, Rose of Versailles, Kodansha

Figure 10 : Riyoko Ikeda, 1979, Rose of Versailles, Kodansha

Figure 11 : Riyoko Ikeda, 1979, Rose of Versailles, Kodansha

Figure 12 : Riyoko Ikeda, 1979, Rose Of Versailles, Kodansha

Figure 14 :Chiho Saito, 1997,Revolutionary Girl Utena, Viz Media

Figure 13 : Chiho Saito, 1997,Revolutionary Girl Utena, Viz Media

Figure 15 Chiho Saito, 1997,Revolutionary Girl Utena, Viz Media

Figure 16: Chiho Saito, 1997,Revolutionary Girl Utena, Viz Media

Figure 17 : Chiho Saito, 1997,Revolutionary Girl Utena, Viz Media

Figure 18 :Chiho Saito, 1997,Revolutionary Girl Utena, Viz Media

Figure 19 Chiho Saito, 1997, Revolutionary Girl Utena, Viz Media

Figure 21 : Chiho Saito, 1997,Revolutionary Girl Utena, Viz Media

Figure 20: Chiho Saito, 1997,Revolutionary Girl Utena, Viz Media

Figure 22 : Lo Sakisaka, 2007, Strobe Edge, Viz Media

Figure 23 : Lo Sakisaka, 2007, Strobe Edge, Viz Media

List of Figures

Figure 1. Tezuka, O 1967, Princess Knight, Kodansha, Tokyo.

Figure 2. Ibid.

Figure 3. Ibid.

Figure 4. Ibid.

Figure 5. Ibid.

Figure 6. Ibid.

Figure 7. Ikeda, R 1979, Rose Of Versailles, Kodansha, Tokyo.

Figure 8. Ibid.

Figure 9. Ibid.

Figure 10. Ibid.

Figure 11. Ibid.

Figure 12. Ibid.

Figure 13. Saito, C 1997, Revolutionary Girl Utena, Viz Media, San Francisco.

Figure 14. Ibid.

Figure 15. Ibid.

Figure 16. Ibid.

Figure 17. Ibid.

Figure 19. Ibid.

Figure 20. Ibid.

Figure 21. Ibid.

Figure 22. Sakisaka, Lo 2007, Ninako, digital illustration, viewed December 2017, < https://i.pinimg.com/736x/23/4e/bc/234ebcaeb127800a6edfd77a2f46181f–strobe-edge-anime-manga.jpg>.

Figure 23. Sakisaka, Lo 2007, Strobe Edge, Viz Media, viewed December 2017, < https://lmfcdn.secure.footprint.net/store/manga/2700/01-001.0/compressed/f1.23.jpg?token=9d736db8bb0b3c80f210111e3ceeeec9de9ed582&ttl=1512460800, https://lmfcdn.secure.footprint.net/store/manga/2700/01-001.0/compressed/f1.23.jpg?token=9d736db8bb0b3c80f210111e3ceeeec9de9ed582&ttl=1512460800>.

Bibliography

Abbott, J. (2015). Shojo: The power of Girlhood in 20th Century Japan. MA. Washington

State University.

Allen, M. and Sakamoto, R. (2007). Popular Culture, Globalization and Japan. Hoboken:

Taylor and Francis.

Anan, N. ( 2014). “The Rose of Versailles: Women and Revolution in Girls’ Manga and the

Socialist Movement in Japan.”. The Journal of Popular Culture [Online] Available at :http://eprints.bbk.ac.uk/12324/7/12324.pdf [ Accessed at 15 October. 2017]

. Big Think. (2011). Judith Butler: Your Behavior Creates Your Gender. [Online Video]. 6 June 2011. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Bo7o2LYATDc. [Accessed: 3 December 2017].

Brown. J. L. (2008). Female Protagonists in Shojo Manga- From The Rescuers to the Rescued. MA. University of Massachusetts Amherst.

Francis, J. (2012). “What’s So Queer About Boys Bonking?” A Queer Analysis of Gender Normativity and Homophobia in Japanese Boy’s Love Manga. MA. School of Oriental and African Studies.

Kinsella, S. (1998). Japanese Subculture in the 1990s : Otaki and the Amateur Manga Movement. Journal of Japanese Studies, [online] Vol.24(2), pp.289-316. Available at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/133236?origin=JSTOR-pdf&seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents [Accessed 29 Jul. 2017].

Hurford, M. (2009). Gender And Sexuality In Shojo Manga: Undoing Heteronormative Expectations in Utena, Pet shop of Horrors, And Angel Sanctuary. Master of Arts. Graduate College of Bowling Green State University.

McLelland, M. (2000). Male Homosexuality and Popular Culture in Modern Japan. Intersections : Gender, History and Culture in the Asian Context, [online] (3). Available at: http://intersections.anu.edu.au/issue3/mclelland2.html#n16 [Accessed 4 Sep. 2017].

McLelland, M. (2000). No Climax, No Point, No Meaning? Japanese Women’s Boy-Love Sites on the Internet. Journal of Communication Inquiry, [online] 24(3), pp.274-291. Available at: http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0196859900024003003 [Accessed 29 Jul. 2017].

McNeil, S (2013). Gender-Bending in Princess Knight. Sequential Tart. [online] Available at : http://www.sequentialtart.com/article.php?id=2374[ Accessed 27 Nov. 2017]

Monden, M. (2015). Shojo Manga Research: The Legacy of Women Critics and Their Gender-Based Approached. Comics Forum. Retrieved From: https://comicsforum.org/2015/03/10/shojo-manga-research-the-legacy-of-women-critics-and-their-gender-based-approach-by-masafumi-monden/ [Accessed 2 Oct. 2017].

Nicolov, A. (2016). How manga is guiding Japan’s youth on LGBT issues. [online] Dazed. Available at: http://www.dazeddigital.com/artsandculture/article/32647/1/how-manga-is-guiding-japan-s-youth-on-lgbt-issues [Accessed 29 Jul. 2017].

Nishiyama, Y (2016). “But I’m still a girl after all” A Discourse Analysis Of Femininities in Popular Japanese Manga Comics. MS. Victoria University of Wellington.

Sasaki, M. (2013). Gender Ambiguity and Liberation of Female Sexual Desire in Fantasy Spaces of Shojo manga and the Shojo subculture. Critical Theory and Social Justice Journal of Undergraduate Research Occidental College, [online] 3(1), pp.1-26. Available at: http://scholar.oxy.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1044&context=ctsj, http://scholar.oxy.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1044&context=ctsj [Accessed 2 Oct. 2017].

Books

Butler, J. (1990). Gender Trouble. New York: Routledge.

Ikeda, R. (1979) Rose of Versailles. Tokyo: Kodansha

Tezuka, O. (1967). Princess Knight. Tokyo: Kodansha.

Saito, C. (1997) Revolutionary Girl Utena. San Francisco : Viz Media

[1] Japanese word for “manga authors/ artist.”

[2] Japanese word for “cute”.

[3] Japanese word for Japanese authors

[4] or “onna-kabuki” in Japanese

[5] Japanese word for “female kabuki actress”

[6] Japanese word for manga artists or authors

Cite This Work

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing stye below:

Related Services

View allRelated Content

All TagsContent relating to: "Literature"

Literature is a term used to describe a body, or collection, of written work traditionally applied to distinguished, well written works of poetry, drama, and novels. The word literature comes from the Latin word Littera, literally meaning “letters”.

Related Articles

DMCA / Removal Request

If you are the original writer of this dissertation and no longer wish to have your work published on the UKDiss.com website then please: