Michigan Primary Care Nurse Practitioner Attitudes Towards Depression

Info: 12378 words (50 pages) Dissertation

Published: 10th Dec 2019

Michigan Primary Care Nurse Practitioner Attitudes Towards Depression

Table of Contents

Page

List of Tables…………………………………………viii

List of Appendices………………………………………ix

Chapter

One: Introduction………………………………………..1

Two: Literature Review……………………………………4

Three: Methodology………………………………………1

Four: Results………………………………………….1

Five: Conclusions……………………………………….4

Six: Implications………………………………………..1

Appendices…………………………………………..iv

References……………………………………………iv

List of Tables

1. Frequencies and percentages of responses for professional confidence subscale…..1

2. Frequencies and percentages of responses for the Therapeutic Optimism subscale…4

3. Frequencies and percentages of responses for the Generalist Perspective subscale…1

4. Mode, means, and standard deviations for professional confidence subscale…….4

5. Mode, means, and standard deviations for therapeutic optimism subscale………1

6. Mode, means, and standard deviations for generalist perspective subscale………4

Chapter One

Introduction

Depression is a chronic health condition that is prevalent, costly, and a cause of disability. According to the National Alliance of Mental Health [NAMI], (2016), approximately 25 million people are affected by major depression in the United States. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorder, fifth edition (DSM -5) lists the criteria that healthcare professionals use to diagnose major depression (NAMI, 2016). For a person to have a diagnosis of major depressive disorder under the DSM-5 criteria they have to have five or more of the nine symptoms. The nine symptoms include depressed mood, loss of interest, change in weight or appetite, insomnia or hypersomnia, psychomotor retardation or agitation, loss of energy or fatigue, worthlessness or guilt, impaired concentration or indecisiveness, and thoughts of death or suicidal ideation. One of the symptoms must be depressed mood or loss of interest in the same 2-week period (Institute of Clinical Systems Improvement, 2016). Depression can affect people of any age, present with different symptoms, and have negative effects if not treated. Symptoms of depression can be mild or moderate to severe and if left untreated can lead to suicide, substance abuse, decline in health condition, decreased quality of life, and functional decline (NAMI, 2016). Causes of depression include genetics, trauma, life circumstances, medications, drugs, and alcohol. Depression can also occur because of a medical condition such as stroke, heart attack, cancer, or diabetes (NAMI, 2016). Depressive symptoms describe the presence of symptoms that do not reach the DSM-5 criteria for any of the included depressive disorders.

Depression is one of the reasons why patients visit primary care in the United States (Haddad et al., 2012). According to the American Psychological Association (2016), one in every four patients who visit primary care suffers from depression. Moreover, most patients with depression do not use mental health services leaving a majority of them seeking treatment in primary care (Burman, McCabe, & Pepper, 2005; Richards, Ryan, McCabe, Groom, & Hickie, 2004). In the Unites States, the third most common reason for hospitalization for people ages 18 to 44 is major depression (NAMI, 2016). According to McTernan, Dollard, and LaMontagne, (2013), workers diagnosed with depression have missed workdays and decreased work productivity and this has a negative effect on an organization’s finances. A study by Beck et al. (2011) also found that people with more depressive symptoms had the lowest work productivity but also found that people with minor levels of depression were also associated with some loss of work productivity. One recommendation made from this study is that employers should provide treatment to employees diagnosed with depression to reduce the financial burden of depression regardless of the severity of depression. Nurse Practitioners (NPs) are increasing becoming the healthcare providers in primary care making them likely to be first point of contact for patients with major depression who seek treatment with their own doctor. This makes it important to investigate their attitudes towards managing depression.

Significance

Nurse Practitioners can provide high quality and cost effective treatment to patients with major depression in primary care (Bauer, 2010; Burman, McCabe, & Pepper, 2005; Groh & Hoes, 2003). NPs can perform medical and psychological assessments, diagnose and treat acute and chronic conditions, order tests and interpret results, prescribe medications, counsel, educate patients about disease prevention and management, and refer patients to specialists (AANP, 2016). In recent years, there has been an increase in the number of NPs working in primary care to help care for people with chronic illness such as depression. According to the American Association of Nurse Practitioners [AANP], (2016), 83.4% of NPs are certified in an area of primary care. Additionally in 2012, the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) conducted a National Sample Survey of Nurse Practitioners; of the 154,000 nurse practitioners, surveyed 60,407 were working in primary care practices or facilities. It is logical to assume that they will be the healthcare providers providing care to increasing numbers of the depressed patients in primary care.

Early identification of depression is vital to providing treatment and preventing negative effects of depression such as suicide. According to the American Association of Suicidology (2014), major depression is a psychiatric disorder that is commonly associated with suicide. In 2014, suicide was the tenth leading cause of death among Michigan residents per 100,000 people in the state (Michigan Department of Health and Human Services, 2014). The American Psychiatric Association (2016) provided guidelines that providers are recommended to use in the treatment of major depression. According to the National Institute of Mental Health (2016), there are several treatment options available for treatment of major depression. Treatment options include antidepressants, psychotherapy such as cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), interpersonal therapy (IPT), and problem-solving therapy, the combination of medications and psychotherapy, group therapy, and electroconvulsive therapy (ECT). Despite the availability of these treatment options depression continues to be misdiagnosed, untreated, and undermanaged due to lack of proper screening of patients seen in primary care and barriers health providers face when attempting to treat major depression (Groh & Hoes, 2013; Pepper, Nieuwsma, & Thompson, 2007; Weich, Morgan, King, & Nazareth, 2007).

In addition, studies done to assess attitudes towards depression using the Depression Attitudes Questionnaire indicated that primary care providers have negative attitudes towards depression (Botega & Silveira, 1996; Kerr, Blizard, & Mann, 1995; Norton et al., 2011). Haddad et al. (2012), stated that “the attitudes of clinicians are likely to be an important factor influencing the way that they assess and respond to patients’ psychosocial problems and their willingness to adopt new approaches to this part of their work” (p. 122). Therefore, an assessment of current attitudes of Michigan NPs working in primary care is an important start that identified the need for education to promote adequate management of depression and ensure positive patient outcomes. This study’s results provided evidence based data on attitudes of current NPs working in primary care that can be used to guide education on how to change attitudes of current and future NPs. Prevention of the effects of depression such as suicide, disability, and financial burden begins with effective assessment of depression, and appropriate treatment.

There is limited research regarding attitudes and beliefs of United States NPs towards depression. Surveying NPs working in primary care using the Revised Depression Attitude questionnaire (Haddad, Menchetti, McKeown, Tylee, & Mann, 2015) allowed the researcher to assess their attitudes towards depression. It is important to focus on depression in primary care because it is the place most patients seek help and early detection of depression is important for its proper management. Nurse Practitioners play a vital role in caring for patients with depression and no survey has been conducted to examine Michigan NPs’ attitudes towards depression, hence the interest of this study. This study contributes to nursing knowledge by building on current research related to attitudes towards depression.

Purpose of Study

With more patients seeking treatment for depression in primary care, it is important to have a clear picture of NPs attitudes towards depression. According to Fussman, DeGuire, McCloskey, Hodges, and Lyles (2011), 9.4% of Michigan adults have major depression. Proper depression management is important to ensure positive patient outcomes. The purpose of this study was to identify Michigan primary care NPs attitudes towards depression. Data obtained from the study helped to identify a need for NPs education on depression management. NPs should be able to recognize depression, provide intervention, and refer patients to a specialist if needed.

Research Question

What are the current attitudes of Michigan primary care NPs towards depression? This quantitative descriptive study assessed their current attitudes towards depression using the Revised Depression Attitudes Questionnaire. The scores from the questionnaire provided quantitative data that identified what their attitudes are.

Chapter Two

Literature Review

A search of databases was conducted that included CINAHL, PubMed, Google Scholar, and Psychinfo. The search terms used included depression, depression management, attitudes, nurse practitioners, primary care providers, general practitioners, and depression attitude questionnaire. Searches were limited to English and peer reviewed journals published in the years 1990 to 2016. Multiple searches were performed with different search terms in the above databases. There were limited articles solely focused on nurse practitioners (NPs). Therefore, most of the articles reviewed focus on the role of the primary care provider or the general practitioner and the use of the depression attitude questionnaire to assess attitudes towards depression but not on the role of the NP. Based on the literature reviewed, the articles suggested that depression is not well managed due to attitudes of healthcare providers, comfort level when caring for patients with depression, barriers to depression management, and lack of depression screening. These four themes are explored.

The relationship between attitudes and depression was the first theme identified. In a study by Norton et al. (2011), the Depression Attitude Questionnaire (DAQ) was sent to approximately 5000 French family practitioners to evaluate attitudes and beliefs towards depression, 468 NPs (9%) completed and returned the DAQ. The study results revealed that French family practitioners had a neutral position on professional ease when dealing with depressed patients, positive view on the origin of depression and belief that it is necessary to use antidepressants as a treatment for depression (Norton et al., 2011). In addition, the study showed that training family practitioners in mental health through continuing education and postgraduate training improved attitudes towards depression. In a similar study by Burman et al., (2005), the Depression Attitudes Questionnaire was administered to 108 advanced practice nurses (APN) in Wyoming to determine providers’ attitudes towards depression and mental illness. Fifty-two surveys were returned for a return rate of 55.3%. Findings from the study showed that APNs had a fairly moderate attitude towards pharmacological treatment of depression, and were neither uneasy nor overly confident or comfortable about caring for patients with depression.

Kerr et al., (1995) compared attitudes of general practitioners and psychiatrists in Wales, England. The DAQ responses were received from 74 practitioners (60%) and 65 psychiatrists (67%). Results of the study showed that general practitioners had a more negative attitude than that of psychiatrists when dealing with patients with depression and identification of depression. General practitioners were less confident when dealing with depressed patients and found the work harder and less rewarding when compared to psychiatrists. The authors of this study indicated that the DAQ is reliable and might be a useful tool to identify education needs to improve identification and management of depression in primary care.

Botega and Silveira (1996) conducted a study in Brazil that identified attitudes of 110 general practitioners. The study also used the DAQ and 78 practitioners completed it for a return rate of 70%. Seventy one percent of the participants reported difficulty identifying depression. The study results support the need for additional education to increase knowledge on identification and management of depression of general practitioners.

The second theme addressed the lack of comfort with depression management. The literature review revealed that NPs lack the appropriate education to diagnose and manage patients with depression thus the lack of comfort with managing depression. Groh and Hoes (2003) sampled 3000 NPs from the membership of the American Academy of Nurse Practitioners on assessment, diagnosis, and treatment options of depressive symptoms in women. One thousand six hundred and forty seven surveys competed, for a return rate of 55%. The study revealed that NPs used multiple assessment tools to assess for depression and considered different factors prior to determining the appropriate treatment of depression. In this study, 65% of the NPs felt that they were adequately prepared to assess and diagnose depression and 51% believed that they had adequate knowledge to treat depression.

In a study by Pepper, Nieuwsma, and Thompson (2007), 554 DAQ were mailed to primary care providers and 180 were returned, response rate of 32%. The study was conducted in a rural area in Wyoming. The purpose of the study was to examine whether rural primary care providers’ attitudes towards depression are associated with their reports of assessment and treatment of depression. The study identified that providers who reported unease with patients with depression were less likely to assess for symptoms of depression or provide counselling or referrals to see a psychiatrist. This shows that training of primary care providers including NPs should focus on their assessment of depression and adequate provision of treatment.

Barriers to depression management in primary care, was another theme in the literature reviewed. A study by Burman et al. (2005) investigated the treatment practices and barriers for depression and anxiety treatment of NPs in Wyoming. One hundred and eight questionnaires on barriers to depression treatment were mailed and 52 advanced practice nurses returned the questionnaire, return rate of 48%. The top barriers identified by over 25% of the participants included lack of insurance, inadequate insurance and inadequate mental health providers for referral.

Richards, Ryan, McCabe, Groom, and Hickie (2004) investigated the barriers to effective management of depression and attitudes towards depression in general practice in Australia. Four hundred and twenty general practitioners completed the survey on perceived barriers that limit their ability to care for patients with depression. There were several barriers identified in the study; over 50% of the participants identified lack of access to mental health, inadequate allocated consultation time, and poor reimbursement of time spend managing depression. Perceived barriers by 30% of the participants included patients’ reluctance to see a specialist, limited office time, management of presenting problems limits time on depression

Depression screening of patients in primary care is not performed given the multiple chronic comorbidities making caring for these patients’ complex and the workload prevents attention to depression (Richards et al., 2004). In a study by Pepper et al. (2007), questionnaires were sent to 554 primary care providers and 180 returned the questionnaires, only 32% of the respondents reported using a screening instrument to help detect depression. Another study by Groh and Hoes (2003), 33% of NPs used a standardized depression tool such as Beck Depression Inventory to screen for depression.

Conclusion

Studies have been conducted to identify attitudes of primary care providers towards depression (Botega & Silveira, 1996; Burman et al., 2005; Groh & Hoes, 2003; Norton et al., 2011; Pepper et al., 2007 and Richards, Ryan, McCabe, Groom, & Hickie, 2004). Despite availability of several treatment and interventions to manage depression, research shows that depression is under identified and under-managed. The research reviewed indicates the need for accurate diagnosis, increased screening, and treatment of depression to prevent its effects on patients, their families, society, and the economy. According to the U.S Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration (2010), almost half of the recently licensed NPs are joining primary care. This indicates that NPs are more likely to be providers to treat depression in primary care. This places importance on NPs attitudes towards depression. The most important point in the literature reviewed is that primary care providers have negative attitudes towards treating and managing depression. The purpose of this study is to identify Michigan primary care nurse practitioners attitudes towards depression.

Theoretical Framework

Albert Bandura’s Self Efficacy theory provides a conceptual framework for analyzing nurse practitioner attitudes in management of depression in clinical practice. Self-efficacy theory was developed from Bandura’s social learning theory; it is the belief that people can exercise influence over their behavior to produce a desired outcome (Bandura, 1977). People with high self-efficacy believe they can perform well given a task and are likely to view a difficult task as something to be mastered not avoided, while people with low efficacy avoid challenges and view them as beyond their capabilities (Bandura, 1977). The belief that people with high self-efficacy hold influence on what they feel and think about others, thus motivating them to action. Bandura identified the major sources of self-efficacy as performance mastery, vicarious experience, social persuasion, and emotional arousal (Bandura, 1977).

Nurse practitioners in primary care can evaluate their practice of depression management through the application of self-efficacy. NPs who have high efficacy are capable of performing a given behavior are often found to be socially engaged in rendering supportive services to depressed patients more frequently than those ones who feel unskilled. Self-efficacy in diagnosing and treating depression has been found to predict whether primary care clinicians view depression as important and frequent problem in their practice (Pepper et al., 2007). NPs with high self-efficacy on depression management are more likely to screen patients for depression and provide treatment to depression patients compared to those with low self-efficacy (Pepper et al., 2007). Richards et al. (2004) surveyed primary care practitioners to rate their level of self-efficacy in relation to assessment and treatment of depression. Findings of the study showed that 90% of the 420 practitioners that participated were confident in treating depression with medication. Seventy percent of practitioners were confident recognizing suicide, assessing degree of suicide risk, and working with other mental health professionals. Only 30% of practitioners were confident conducting non – pharmacological interventions for drug and alcohol problems and treating depression with evidence based psychological treatments.

With increasing number of patients presenting to primary practice with depression, NPs should master depression assessment and have the adequate knowledge, and positive attitude to care for these patients and ensure they get the treatment they need to reduce all the debilitating effects of depression. The management of depression can be complex, NPs should have confidence to screen patients for depression and provide treatment.

Chapter Three

Methodology

The purpose of this study was to identify Michigan primary care nurse practitioners (NPs) attitudes towards depression. This chapter discusses the design, sample, data collection, instrument, protection of human rights, data analysis, and study limitations.

Design

A descriptive cross-sectional research design was used to assess the attitudes of Michigan NPs working in primary care towards depression. Polit and Beck (2012) stated, “The purpose of descriptive studies is to observe, describe, and document aspects of a situation as it naturally occurs” (p. 226). This design was appropriate for this study because data could be reliably collected using a self-report questionnaire and analyzed for attitudes towards depression. Self-report questionnaires are cost-effective and efficient. The study is cross-sectional in nature as data was collected at one point in time per participant (Polit & Beck, 2012).

Sample

The target population for this study was a convenience sample of 1134 NPs obtained from the Michigan Council of Nurse Practitioners (MICNP). Inclusion criteria for participation included participant above 18 years of age, a member of MICNP, currently working in primary care, and have internet access. There are 6726 licensed Nurse Practitioners according to Michigan department of licensing and regulatory affairs (2016) and 1134 NPs are members of MICNP. Of these, just less than half (n=511) work in primary care thus the sample size of this study. The sample represented NPs working in different primary cares across Michigan. An estimated response rate of 10% reduced the sample to 51 completed Revised Depression Attitude Questionnaires (R-DAQ). In a similar study about barriers to depression and anxiety treatment and attitudes towards depression by Burman, McCabe, and Pepper (2005) a sample of 94 advance practice nurses in Wyoming was used.

Data Collection

Data collection began when the director of MICNP sent out the recruitment email to all 1134 Nurse Practitioners. The recruitment email (Appendix A) explained the purpose of the study, why participants were chosen to complete the study, and my contact and advisor information. If the NP chose to participate in the survey, he/she clicked on the hyperlink to Survey Monkey provided. The link routed the participant to the demographic form (Appendix B) that included age, years of experience as a nurse practitioner, and if they are currently working in primary care. Once the demographic form was completed those that clicked that they worked in primary care had a link to complete the R-DAQ (Appendix C). Only completed surveys in their entirety were used in final data analysis.

Instrument

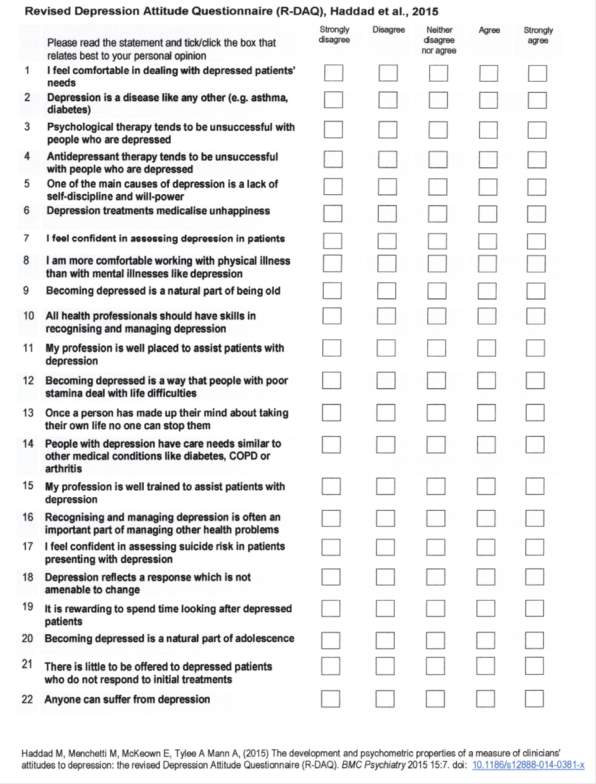

To assess the attitudes of NPs towards depression the R-DAQ was administered with permission of Dr. Mark Haddad [personal communication, March 18, 2016], (Appendix D). The R-DAQ included 22 questions for which participants were asked to indicate level of agreement using a 5-point Likert scale and response options were 1 = Strongly disagree, 2 = Disagree, 3 = Neither disagree nor agree, 4 = Agree, and 5 = Strongly Agree. Scores can range from 22 to 110, with a low score indicating a negative attitude towards depression. Overall reliability of this questionnaire has been identified through an internal consistency of Cronbach’s alpha 0.80 (Haddad, Menchetti, McKeown, Tylee, & Mann, 2015) when used with a sample size of 167 general practitioners and adult nurses. Psychometric results of the R-DAQ ranged from 57 to 110, the mean value was 87.74, median 88, and standard deviation 9.84 (Haddad et al., 2015). Concerns about the psychometric adequacy of the DAQ and its construction to be used with a specific group of health professionals in a specific setting in the UK led to the revisions of the Depression Attitude Questionnaire (DAQ). The R-DAQ was revised from the original DAQ using previous studies that had used DAQ to make it more useful to use with different healthcare professionals outside the United Kingdom (Haddad et al., 2015). The panel of experts considered attitude dimensions, content, and item wording and after an agreement of greater that 70% the tool was tested (Haddad et al., 2015).

According to Haddad et al. (2015), the R-DAQ has three subscales: professional confidence, therapeutic optimism, and generalist perspective about depression. The first subscale, professional confidence, comprised of seven items (questions 1, 7, 8 11, 15, 17, and 19) assessed confidence and feeling comfortable as a practitioner to provide depression care. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for the subscale was 0.81. The second subscale is therapeutic optimism about depression consists of 10 items (questions 3, 4, 5, 6, 9, 12, 13, 18, 20, and 21) that were reversed scored and identified negative statements about depression and its treatment, with a Cronbach alpha coefficient of 0.76. The last subscale consisted five items (questions 2, 10, 14, 16, and 22) and identified generalist perspective about depression occurrence, recognition, and management with a Cronbach alpha coefficient of 0.62 (Haddad et al., 2015).

To establish content and face validity, three nurse practitioners were asked to read the questionnaire to ensure that the questions were consistent with attitudes towards depression. The three NPs had an average experience of five years working with depressed patients in primary care. Feedback was received from the three NPs that questions in the R-DAQ were related and consistent with the topic of depression. According to Haddad et al. (2015), the R-DAQ has a Flesch reading Ease Score of 46.7 and a Flesch Kincaid Grade level of 9.4. These scores indicate that the questionnaire is easily understandable. The average time taken by the three nurse practitioners to complete the questionnaire was less than five minutes, therefore five minutes was chosen as the appropriate time it will take participants to complete the survey.

Protection of Human Subjects

To ensure protection of the participants’ minimal risk, Institutional Review Board exempt approval was granted by Saginaw Valley State University to conduct the study (Appendix E). The purpose of the study and my contact information were emailed to the participants. Completion of the survey constituted informed consent. The participants were informed that participation was voluntary, they can opt out of the survey at any time without penalty, and no compensation would be received for completing the survey. All surveys were made anonymous, as the surveys were completed via Survey Monkey with an IP address block enabled using SSL encryption and took approximately 5 minutes to complete. Participants were informed of the potential risk for breach of confidentiality. Confidentiality was protected to the extent allowed by law and results of the study were published with no identifying information. There is also a psychological risk of discomfort related to the NPs answering questions about their practice of treating depression patients. Only the researcher had access to the data. Lastly, all data collected will be kept confidential and secured for 3 years and then destroyed appropriately (paper documents shredded and computer data files erased).

Data Analysis

The Statistical Package for Social Sciences Program (SPSS) at Saginaw Valley State University was used for data analysis. Data was analyzed using descriptive statistics: means, frequencies, standard deviation, and correlations. Correlations were done to see if there were any relationships between ages, years of experience as a NP, and attitudes towards depression. The three subscales of the questionnaire professional confidence, therapeutic optimism, and generalist perspective about depression were correlated with each other. Results from the statistical analysis were used to describe attitudes of NPs towards depression and answer the following possible hypotheses: NPs who reported professional confidence were more likely to report higher therapeutic optimism and NPs who reported professional confidence reported high generalist perspective about depression occurrence, recognition, and management. Demographic data was used to describe the sample and reported as a frequency and percentage. The R-DAQ was scored using the Likert scale 1 = Strongly disagree, 2 = Disagree, 3 = Neither disagree nor agree, 4 = Agree, and 5 = Strongly Agree. All questions were scored as above except 10 questions that concern therapeutic optimism about depression (questions 3, 4, 5, 6, 9, 12, 13, 18, 20, and 21) that were reverse scored (Haddad et al., 2015). Reverse scoring of the Likert scale was scored in the opposite direction: Strongly disagree = 5, Disagree = 4, Neither disagree nor agree = 3, Agree = 2 and Strongly agree = 1.

Chapter Four

Results

This chapter discusses findings of the research question “What are Michigan primary care nurse practitioner attitudes towards depression?” This field study used a quantitative cross sectional descriptive design and data were obtained from a sample of nurse practitioners (NPs) who are current members of Michigan Council of Nurse Practitioners (MICNP) and completed an online survey that was conducted via Survey Monkey. The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 24 was used to perform statistical analyses. Descriptive statistics and Spearman’s correlation were used to analyze the data.

Sample

All 1134 NPs who are current members of MICNP were invited to participate in the study. Of the 1134 members, only 511 members work in primary care. During the four-week period that the survey was opened, 74 primary care NPs who met inclusion criteria completed the survey for a return rate of 14.5%. The first part of the survey inquired about participant’s age and years of experience as a nurse practitioner. The majority of respondents were in the 51-60 age category (n = 19, 25.7%), followed by ages > 60 (n = 15, 20.3%), ages 31-40 and 41-50 categories which both had the same number of participants (n = 14, 18.9%). Least number of participants were ages 41-50 category (n = 12, 16.2%). Data showed 21 (28.4%) with 1-5 years of experience as an NP; 16 (21.6%) with 6-10 years; 37 (50 %) with more than 10 years as an NP.

Overall Scoring

The instrument used in this study was the Revised Depression Attitude Questionnaire (R-DAQ) which contained 22 questions (Haddad et al., 2015). All 22 questions were scored using a Likert scale 1 = Strongly disagree, 2 = Disagree, 3 = Neither disagree nor agree, 4 = Agree, and 5 = Strongly Agree. All questions were scored as above except 10 questions ( 3, 4, 5, 6, 9, 12, 13, 18, 20, and 21) scored using reverse scoring; Strongly disagree = 5, Disagree = 4, Neither disagree nor agree = 3, Agree = 2 and Strongly agree = 1. Data analysis included calculating frequencies and percentages of responses for each question and calculating modes to determine number of participants for each of the 22 questions, means to determine participants’ attitude towards each question, and standard deviations for each question to determine the uniformity of participants’ responses to the questions. Tables 1, 2, 3 show the summary of the frequencies and percentages of the responses by subscales and Tables 4, 5, 6 show the summary of the mode, means, and standard deviations by subscales.

TABLE 1: Frequencies and percentages of responses for professional confidence subscale.

| # | Label | Strongly Disagree | Disagree | Neither disagree nor agree | Agree | Strongly Agree |

| 1.

7. 8. 11. 15. 17. 19. |

I feel comfortable in dealing with depressed patients’ needs.

I feel confident in assessing depression in patients. I am more comfortable working with physical illness than with mental illness like depression. My profession is well placed to assist patients with depression. My profession is well trained to assist patients with depression. I feel confident in assessing suicide risk in patients presenting with depression. It is rewarding to spend time looking after depressed patients. |

3

(4.1%) 2 (2.7%) 8 (10.8%) 0 (0%) 1 (1.4%) 0 (0%) 1 (1.4%) |

3

(4.1%) 3 (4.1%) 28 (37.8%) 3 (4.1%) 12 (16.2%) 2 (2.7%) 2 (2.7%) |

1

(1.4%) 2 (2.7%) 18 (24.3%) 4 (5.4%) 9 (12.2%) 8 (10.8%) 21 (28.4%) |

40

(54.1%) 50 (67.6%) 18 (24.3%) 38 (51.4%) 40 (54.1%) 48 (64.9%) 44 (59.5%) |

27 (36.5%)

17 (23%) 2 (2.7%) 29 (39.2%) 12 (16.2%) 16 (21.6%) 6 (8.1%) |

TABLE 2: Frequencies and percentages of responses for the Therapeutic Optimism subscale.

| # | Label | Strongly Disagree | Disagree | Neither disagree nor agree | Agree | Strongly Agree |

| 3.

4. 5. 6. 9. 12. 13. 18. 20. 21. |

Psychological therapy tends to be unsuccessful with people who are depressed.

Antidepressant therapy tends to be unsuccessful with people who are depressed. One of the main causes of depression is a lack of self-discipline and will power Depression treatment medicalize unhappiness Becoming depressed is a natural part of being old. Becoming depressed is a way that people with poor stamina deal with life difficulties. Once a person has made up their mind about taking their own life no one can stop them. Depression reflects a response which is not amenable to change. Becoming depressed is a natural part of adolescence. There is little to be offered to depressed patients who do not respond to initial treatments |

22

(29.7%) 26 (35.1%) 36 (48.6%) 23 (31.1%) 29 (39.2%) 22 (29.7%) 26 (35.1%) 22 (29.7%) 31 (41.9%) 35 (47.3%) |

49

(66.2%) 39 (52.7%) 33 (44.6%) 38 (51.4%) 44 (59.5%) 47 (63.5%) 46 (62.2%) 44 (59.5%) 39 (52.7%) 37 (50%) |

3

(4.1%) 8 (10.8%) 3 (4.1%) 11 (14.9%) 1 (1.4%) 4 (5.4%) 1 (1.4%) 3 (4.1%) 3 (4.1%) 0 (0%) |

0

(0%) 1 (1.4%) 1 (1.4%) 2 (2.7%) 0 (0%) 1 (1.4%) 1 (1.4%) 4 (5.4%) 0 (0%) 2 (2.7%) |

0

(0%) 0 (0%) 1 (1.4%) 0 (0%) 0 (0%) 0 (0%) 0 (0%) 1 (1.4%) 1 (1.4%) 0 (0%) |

Note: Results displayed in reverse coding

TABLE 3: Frequencies and percentages of responses for the Generalist Perspective subscale.

| # | Label | Strongly Disagree | Disagree | Neither disagree nor agree | Agree | Strongly Agree |

| 2.

10. 14. 16. 22. |

Depression is a disease like any other

(e.g. asthma, diabetes). All health professionals should have skills in recognizing and managing depression People with depression have care needs similar to other medical conditions like diabetes, COPD or arthritis Recognizing and managing depression is often an important part of managing other health problems Anyone can suffer from depression |

4

(5.4%) 1 (1.4%) 0 (0%) 0 (0%) 0 (0%) |

10

(13.5%) 3 (4.1%) 2 (2.7%) 0 (0%) 1 (1.4%) |

4

(5.4%) 0 (0%) 1 (1.4%) 0 (0%) 0 (0%) |

28

(37.8%) 31 (41.9%) 42 (56.8%) 34 (45.9%) 31 (41.9%) |

28 (37.8%)

39 (52.7%) 29 (39.2%) 40 (54.1%) 42 (56.8%) |

Table 4: Summary of the mode, means, and standard deviations for professional confidence subscale.

| # | Label | Mode | Mean | Standard Deviation |

| 1.

7. 8. 11. 15. 17. 19. |

I feel comfortable in dealing with depressed patients’ needs.

I feel confident in assessing depression in patients. I am more comfortable working with physical illness than with mental illness like depression. My profession is well placed to assist patients with depression. My profession is well trained to assist patients with depression. I feel confident in assessing suicide risk in patients presenting with depression. It is rewarding to spend time looking after depressed patients. |

4

4 2 4 4 4 4 |

4.15

4.04 2.7 4.26 3.68 4.05 3.70 |

0.946

0.818 1.043 0.741 0.981 0.660 0.716 |

Note: 1 = Strongly Disagree, 2 = Disagree, 3 = Neither Disagree nor agree, 4 = Agree,

5= Strongly Agree

Table 5: Summary of the mode, means, and standard deviations for therapeutic optimism subscale.

| # | Label | Mode | Mean | Standard Deviation |

| 3.

4. 5. 6. 9. 12. 13. 18. 20. 21. |

Psychological therapy tends to be unsuccessful with people who are depressed.

Antidepressant therapy tends to be unsuccessful with people who are depressed. One of the main causes of depression is a lack of self-discipline and will power Depression treatment medicalize unhappiness Becoming depressed is a natural part of being old. Becoming depressed is a way that people with poor stamina deal with life difficulties. Once a person has made up their mind about taking their own life no one can stop them. Depression reflects a response which is not amenable to change. Becoming depressed is a natural part of adolescence. There is little to be offered to depressed patients who do not respond to initial treatments. |

4

4 5 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 |

4.26

4.2 4.38 4.11 4.38 4.22 4.31 4.11 4.34 4.42 |

0.525

0.74 0.753 0.751 0.516 0.603 0.572 0.82 0.688 0.641 |

Note: 5 = Strongly Disagree, 4 = Disagree, 3 = Neither disagree nor agree, 2 = Agree,

1 = Strongly Agree. Results displayed with reverse coding

Table 6: Summary of the mode, means, and standard deviations for generalist perspective subscale.

| # | Label | Mode | Mean | Standard Deviation |

| 2.

10. 14. 16. 22. |

Depression is a disease like any other( e.g. asthma, diabetes).

All health professionals should have skills in recognizing and managing depression People with depression have care needs similar to other medical conditions like diabetes, COPD or arthritis Recognizing and managing depression is often an important part of managing other health problems Anyone can suffer from depression. |

4

5 4 5 5 |

3.89

4.41 4.32 4.54 4.54 |

1.211

0.81 0.643 0.502 0.578 |

Note: 1 = Strongly Disagree, 2 = Disagree, 3 = Neither Disagree nor agree, 4 = Agree,

5= Strongly Agree

The total score (attitudes score) for the participants ranged from 75 to 106. The mean attitude score was 91 with a standard deviation of 6.538. Median score of the sample was 89 and a mode of 86. The survey was divided into three subscales professional confidence, therapeutic optimism, and generalist perspective about depression according to Haddad et al. (2015). Table one shows the frequency distribution of responses for the professional confidence subscale (questions 1, 7, 8 11, 15, 17, and 19) which assessed confidence and feeling comfortable as a NP to provide depression care. Majority of the NPs showed professional confidence with greater than 70% selecting agree or strongly agree on questions 1,7, 11, 15, and 17. Question eight

(I am more comfortable working with physical illness than with mental illness like depression) indicated mixed attitudes with 28 (37.8%) of the participants selecting disagree, 18 (24.3%) selecting neither disagree nor agree, and 18 (24.3%) selecting agree. Question 19 (it is rewarding to spend time looking after depressed patients) also showed mixed attitudes with majority of the participants selecting 44 (59.5 %) and 21 (28.45%) selecting neither disagree nor agree. The total scores of the professional confidence subscale ranged from 19 to 32, with an overall mean score of 26.58 (standard deviation of 2.601). Median score was 27; Mode scores were 25 (n=13, 17.6%) and 26 (n=13, 17.6%).

Second subscale was therapeutic optimism (questions 3, 4, 5, 6, 9, 12, 13, 18, 20, and 21) that were reversed scored and identified negative statements about depression and its treatment, frequency distribution of responses shown in table two. Greater than 90% of NPs responded strongly disagree or disagree to all questions on the subscale except question 6 (depression treatment medicalize unhappiness) with 82% selecting strongly disagree or disagree while 14.9 % selected neither disagree nor agree. The total scores for therapeutic subscale ranged from 35-50. Mean score was 42.72 with a standard deviation of 3.47. The median score was 42 and the mode was 40 (n=13, 17.6%).

The last subscale consisted five items (questions 2, 10, 14, 16, and 22) and identified generalist perspective about depression occurrence, recognition, and management. Majority of the participants (>75%) responded agree or strongly agree to all five questions of the subscale. The scores of the subscale ranged from 18 to 25 with the mean score being 21.7, standard deviation 2.31. The median score was 22 and mode score 25 (N=13, 17.6%).

Spearman’s rho correlation analysis was computed to explore the relationships between age, years of experience, total score, and the three subscales (professional confidence, therapeutic optimism, and generalist perspective about depression occurrence, recognition, and management) for all 74 participants who completed the survey. Results showed strong correlation between age with years of experience (r = 0.68; Cohen, 1988), no statistical correlation of age with total score which is reflective of the attitude (r= 0.21) and years of experience with total score (r =0.17)

Table 7: Summary of correlations

| 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |||

|

.683** | .114 | .060 | .359** | .214 | ||

|

x | .177 | .002 | .297* | .168 | ||

|

x | x | .297* | .401** | .696** | ||

optimism |

x | x | x | .494** | .805** | ||

perspective |

x | x | x | x | .771** | ||

|

x | x | x | x | x | ||

** Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed).

* Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed).

Results were also used to answer the two hypotheses of the study. Hypothesis one: NPs who report professional confidence will be more likely to report higher therapeutic optimism. Results revealed that there is a positive moderate correlation between professional confidence and therapeutic optimism (r = 0.3, p = 0.05; Cohen, 1988). Hypothesis 2: NPs who report professional confidence will report high generalist perspective about depression occurrence, recognition, and management. Results show positive moderate correlation (r = 0.4, p = 0.01; Cohen, 1988).

Other findings of interest noted positive moderate correlation between therapeutic optimism subscale and generalist perspective subscale (r = 0.49, p = 0.01) and relationship between age and the three subscales (professional confidence, therapeutic optimism, and generalist perspective). Age and generalist perspective subscale showed positive moderate correlation (r = 0.36, p = 0.01), there was no statistical significant correlation between age and the other two subscales. In addition, when comparing the years of experience and the subscales, there was a positive moderate correlation between years of experience and generalist perspective (r = 0.3, p = 0.05; Cohen, 1988) and no statistical significance correlation with professional confidence and therapeutic optimism. Total score results were not used in correlations as the subscales scores are part of the total score.

Chapter Five

Conclusions

Prevalence of depression, its debilitating effects, and increase in patients seeking care in primary care where Nurse Practitioners (NPs) are becoming the care providers puts emphasis on identifying their attitudes. Various studies have sought to identify attitudes of NPs towards depression (Burman et al., 2005; Groh & Hoes, 2003; Norton et al. 2011). The purpose of this quantitative study was to identify the attitudes of Michigan primary care NPs towards depression using the Revised Depression Attitude Questionnaire (R-DAQ). The researcher also sought to determine if age and years of experience affected their attitude.

From this study, it is clear that Michigan primary care NPs are caring for patients with depression. Overall, the study NPs had an optimistic attitude towards depression the mean average score was 91, the max score on the scale was 110. Developers of the scale Haddad et al. (2015) did not give a preset satisfactory score. In the study by Haddad et al. (2015), the mean score of the R-DAQ was 87.74 and median score was 88. Based on this score 62.2% participants in this study achieved a score greater than 87. A positive finding of attitude towards depression are consistent with other studies (Burman et al., 2005; Groh & Hoes, 2003). In contrast, other studies (Botega & Silveira, 1996; Kerr, Blizard, & Mann, 1995; Norton et al., 2011) showed that primary care providers have negative attitudes towards depression. This study is the first to identify Michigan primary care NPs attitudes towards depression using the R-DAQ.

The study showed that there is a positive strong correlation between age and years of experience, thus older NPs had more years of experience. Most participants in the study were aged greater than 60 and had greater than 10 years of experience as a NP. Age and years of experience correlations were not statistically significant to total score therefore not predictors of attitude towards depression. In similar studies (Botega & Silveira, 1996; Groh & Hoes, 2003; Norton et al., 2011), reported age and years of experience as demographic characteristics of the NP sample but not correlated with the attitude score. Age and years of experience positively correlated with generalist perspective subscale but not to the other subscales: professional confidence and therapeutic optimism. These findings may indicate that knowledge about depression, its occurrence, experience recognizing depression and treating it are factors that positively influenced the generalist perspective sub-scale score.

It was identified that NPs with professional confidence had a positive therapeutic optimism towards depression (hypothesis one). Feeling comfortable, confident, and well trained in depression care might have reduced pessimistic attitudes towards depression and its treatment. NPs who reported professional confidence reported high generalist perspective on depression and its care (hypothesis two). Increased confidence in depression management helped reflect a positive generalist perspective on depression occurrence, recognition, and management

No studies identified thus far investigated the correlations of age and years of experience to the three subscales of the R-DAQ or correlated each of the subscales. Groh and Hoes (2003) reported that NPs (n= 1071, 65%) of the respondents were comfortable assessing and diagnosing patients with depression. In addition, a study by Pepper et al. (2007) showed that primary care providers who expressed discomfort with depressed patients are less likely to assess for depression. Only 32% (n=180) of the PCPs reported using a screening tool to detect depression in patients.

Limitations

Although the study identified positive attitudes of Michigan primary care NPs towards depression, there are several limitations. The limitations of any study are based on threats to internal and external validity. Three treats to internal were identified in this study: sample size, participant selection bias, and bias of accuracy on self-assessment on questionnaire. The first limitation was the sample selection bias because participants were a nonrandom convenience sample of Michigan NPs who are members of Michigan Council of Nurse Practitioners (MICNP) and who volunteered to take the R-DAQ via Survey Monkey rather than a random group of Michigan NPs who are involved in depression care in primary care setting. As such, the study participants may not be representative of all primary care settings in Michigan. Second limitation is sample size; only 74 NPs completed the online survey among 511 primary care NPs who are members of MICNP, response rate 14.5% thus not generalizable to Michigan or NPs in general. A comprehensive study involving more NPs in Michigan could yield more data that could be used to draw conclusions. Third limitation is the use of the R-DAQ a self-administered questionnaire could yield bias and participant’s accuracy in assessing their skills. The positive finding may be a result of only NPs interested in depression completing the online R-DAQ.

Threats to external validity; the sample of NPs was limited to NPs who had computer access to take the internet survey. NPs who had no internet access were not eligible to participate in the study, which reduced the representative nature of the sample. The sample was limited to NPs who are members of MICNP and those who work in primary care, therefore, limiting the ability to make generalized findings to all NPs or even NPs in primary care outside of Michigan.

Chapter Six

Implications

Depression is a serious disease that has several implications to the patient, healthcare system, and the society. Primary care is increasingly becoming the first contact that depressed patient have with the healthcare system and nurse practitioners (NPs) may be the providers providing care therefore will be important to understand what their attitudes towards depression are. The findings of this study are significant to depression care in primary care by contributing to existing knowledge that primary care NPs have a positive attitude towards depression, high professional confidence dealing with depressed patients, therapeutic optimism about depression and its treatment, and strong generalist perspective about depression occurrence, recognition, and management.

The literature supports that attitude towards depression is a predictor of provider care towards a patient with depression. Identifying attitudes of primary care NPs towards depression may help predict their acceptability and care towards depressed patients. It is important to find out what the NPs attitudes towards depression are so that appropriate educational plan can be implemented to improve their attitude. Only 70% of study NPs agreed that their profession is well trained to assist patients with depression. Data can therefore be used to identify need for NP education on depression management and be used to guide education of current and future NPs. NPs play an important role in primary healthcare of depressed patients as they screen, assess, treat, counsel, and refer patients to specialists.

Results of this study also support the use of the R-DAQ to screen attitudes of primary care providers towards depression. The R-DAQ only takes five minutes to complete and provides a total score that can be used to determine need for more education to help improve attitude score.

Recommendations for Future Research

The study is the first to explore attitudes of Michigan primary care NPs towards depression. However, there were several limitations to this study. Sample size of the study was small making results not generalizable. Future research with larger population of Michigan NPs not limited to members of MICNP would yield a sample more representative of Michigan NPs and results that are more accurate. Future studies should also include years of experience as a Registered Nurse, highest level of education, and number of depressed patients seen at current practice. This data may provide a more clear explanation of different attitudes towards depression. Future studies on Michigan NPs should also determine barriers to screening for depression in primary care due to increasing number of patients seeking treatment of depression in primary care setting.

Appendix A

Email invitation letter

Forwarded on behalf of Judith Yego, MSN/FNP Student at Saginaw Valley State University

Study Title: Michigan Nurse Practitioner Attitudes towards Depression

Dear MICNP member,

You are being invited to participate in a research study on Michigan primary care nurse practitioner attitudes towards depression. Results of the study will provide evidence based data on attitudes of current nurse practitioners towards depression. This knowledge may be used to guide education on how to change attitudes of current and future nurse practitioners and help improve patient outcomes. You are being asked to participate in this survey since you are a Nurse Practitioner in Michigan and a member of Michigan Council of Nurse Practitioners.

As a participant in this study, you will be asked to spend five minutes of your time to complete an internet survey by clicking the Survey Monkey hyperlink. The hyperlink will direct you to a short demographic form. If you answer yes to working in primary care, survey monkey will route you to the Revised Depression Attitude Questionnaire. The questions in the survey will ask about your professional confidence in depression care, therapeutic optimism about depression, and perspective about depression occurrence, recognition, and management. A potential risk in this study is breach of confidentiality. The risk is low because Survey Monkey has measures in place to minimize any breach of confidentiality that include SSL encryption, and disabled respondents IP address collection. Another potential low risk is psychological discomfort answering questions about your management of depression patients. If you experience any psychological discomfort, the researcher will provide you with a list of resources.

There is no penalty for not choosing to participate. Your participation in this study is voluntary and you will not receive any compensation for completing the survey. However, your participation in this survey may help increase understanding of nurse practitioner attitudes towards depression. The survey is anonymous and no identifying information will be collected, as the surveys will have IP address block enabled. If you wish to participate, please complete the survey through the link provided. Completing the survey will constitute informed consent.

If you have questions or concerns about the study, you can contact Judith Yego at jyego@svsu.edu or my research advisor Dr. Suzanne Savoy at smsavoy@svsu.edu. The participant may also contact the Chair, Human Subjects Institutional Review Board (989-964-7488; irbchair@svsu.edu) if questions or problems arise during the course of the study. https://www.surveymonkey.com/r/demographicsandRDAQ

Appendix B

Demographic Form

1. What is your age?

- 18 to 30

- 31 to 40

- 41 to 50

- 51 to 60

- >60

2. Years of experience as a NP?

- 0-5 years

- 6- 10 years

- 10 years

3. Are you currently working in primary care?

- Yes

- No

Appendix C

Appendix D

Permission to use Revised Depression Questionnaire

From: “Mark Haddad” <Mark.Haddad.1@city.ac.uk>

To: “Judith Yego” <jyego@svsu.edu>

Sent: Friday, March 18, 2016 5:21:08 AM

Subject: Re: Request and Permission Letter for Use of Questionnaire

Dear Judith,

Good to hear from you, and thank you for your enquiry.

Yes – certainly you are very welcome to use the Revised Depression Attitude

Questionnaire http://bmcpsychiatry.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12888-

0140381-x- the word version is attached

I am in contact with researchers in Pakistan, the USA, Malaysia, Taiwan, Hong Kong and

Finland in relation to the use of this measure, and am currently completing a paper

detailing it use among medical practitioners in Pakistan.

Good luck with your studies.. and who knows there may be potential to publish compare

your findings with those from other studies.

Best wishes, Mark

Dr Mark Haddad

Senior Lecturer in Mental Health & Senior Tutor for Research

Centre for Mental Health Research

School of Health Sciences

City University London

Northampton Square

London EC1V 0HB

Tel: +44(0)20 7040 5455 Fax: +44(0)20 7040 5811

From: Judith Yego <jyego@svsu.edu>

Sent: Friday, March 18, 2016 1:18 AM

To: Haddad, Mark

Subject: Request and Permission Letter for Use of Questionnaire

March 17, 2016

Request and Permission Letter for Use of Questionnaire

Judith Yego

Saginaw Valley State University

8755 Carter Rd unit 51

Saginaw, Michigan 48623

jyego@svsu.edu

Dear Dr. Mark Haddad

I am a Master of Nursing Student from Saginaw Valley State University writing my

tentative thesis titled Attitudes of Michigan Family Nurse Practitioners towards

depression. This study will identify the correlation between age, years to experience, and

attitudes towards depression. I would like your permission to use the Revised Depression Attitude Questionnaire (R-DAQ) instrument in my research study. I would like to use and print your questionnaire under the following conditions: I will use the questionnaire only for my research study and will not sell or use it with any compensated development activities and I will include the copyright statement on all copies of the instrument.

I would appreciate your consent to my request. I am looking forward to hearing from

you at your convenience

Sincerely, Judith

Appendix E

IRB approval Email

Message from Melissa Woodward:

Re: [989426-1] Michigan Nurse Practitioner Attitudes Towards Depression

The IRB Chair has reviewed your project. The above project is exempt from continuing

IRB review according to federal regulations. Please notify the IRB prior to making any

changes to your study so that it can determine whether such changes affect the status of

the project with respect to federal regulations.

Regards,

Melissa Woodward

References

American Association of Nurse Practitioners (2016). NP fact sheet. Retrieved from

https://www.aanp.org/all-about-nps/np-fact-sheet

American Association of Nurse Practitioners (2016). What is an NP?. Retrieved from

https://www.aanp.org/all-about-nps/what-is-an-np

American Association of Suicidology (2014). Depression and suicide risk. Retrieved from

http://www.suicidology.org/resources/facts-statistics

American Psychological Association (2016). Data on behavioral health in the United States.

Retrieved from http://www.apa.org/topics/depression/index.aspx

Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Towards a unifying theory of behavior change. Psychological

Review, 84, 191-215.

Bauer, J. C. (2010). Nurse practitioners as an underutilized resource of health reform:

Evidence based demonstration of cost-effectiveness. Journal of the American

Academy of Nurse Practitioners, 22, 228-231. doi:10.1111/j.1745-

7599.2010.00498.x

Beck, A., Crain, A. L., Solberg, L. L., Unützer, J., Glasgow, R. E., Maciosek, M. V., &

Whitebird, R. (2011). Severity of depression and magnitude of productivity loss.

Annals of Family Medicine, 9, 305-311. doi:10.1370/afm.1260

Botega, N., & Silveira, G. (1996). General practitioners’ attitudes towards depression: A study in primary care setting in Brazil. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 42, 230-237.

Burman, M., McCabe, S., & Pepper, C. (2005). Treatment practices and barriers for depression and anxiety by primary care advanced practice nurses in Wyoming. Journal of The American Academy of Nurse Practitioners, 17, 370-380.

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Academic

Fussman, C., DeGuire, P., McCloskey, K., Hodges, A.M., & Lyles, J. (2011). Major depression

among Michigan adults with arthritis. Michigan BRFSS Surveillance Brief, 5. Retrieved from http://www.michigan.gov/documents/mdch

Groh, C., & Hoes, L. (2003). Practice methods among nurse practitioners treating depressed women. Journal of the American Academy of Nurse Practitioners, 15, 130-136.

Haddad, M., Menchetti, M., McKeown, E., Tylee, A., & Mann, A. (2015). The development and psychometric properties of a measure of clinicians’ attitudes to depression: The revised Depression Attitude Questionnaire (R-DAQ). BMC Psychiatry, 15, 1-15. doi: doi:10.1186/s12888-014-0381-x

Haddad, M., Menchetti, M., Walters, P., Norton, J., Tylee, A., & Mann, A. (2012). Clinicians’ attitudes to depression in Europe: A pooled analysis of depression attitude questionnaire findings. Family Practice, 29, 121-130. doi.org/10.1093/fampra/cmr070

Health Resources and Services Administration (2012). Highlights From the 2012 National Sample Survey of Nurse Practitioners. Retrieved from http://bhpr.hrsa.gov/healthworkforce/supplydemand/nursing/nursepractitionersurvey/

Institute of Clinical Systems Improvement (2016). Diagnose and characterize major depression/persistent depressive disorder with clinical interview. Retrieved from https://www.icsi.org/

Kerr, M., Blizard, R., & Mann, A. (1995). General practitioners and psychiatrists: Comparison of attitudes to depression using the depression attitude questionnaire. British Journal of General Practice, 45, 89-92.

McTernan, W. P., Dollars, M. F., & LaMontagne, A.D. (2013).

Depression in the workplace: An economic cost analysis of depression-related productivity loss attributable to job strain and bullying, Work & Stress. An International Journal of Work, Health & Organizations, 27, 321-338, doi: 10.1080/02678373.2013.846948

Michigan Department of Health and Human Services (2014). Michigan leading causes of death. Retrieved from http://www.mdch.state.mi.us/pha/osr/deaths/causrankcnty.asp

Michigan Depart of Licensing and Regulatory Affairs (2016). License 2000 License Count. Retrieved from http://www.michigan.gov/documents/lara/License_Counts_090115_498869_7.pdf

National Alliance of Mental Health (2016). Depression. Retrieved from http://www.nami.org/Learn-More/Mental-Health-Conditions/Depression

National Institute of Mental Health (2016). Depression treatment and therapies. Retrieved from https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/depression/index.shtml

Norton, J., Pommie, C., Cogneau, J., Haddad, M., Ritchie, K., & Mann, A. (2011). Beliefs and attitudes of French family practitioners toward depression: The impact of training in mental health. International Journal of Psychiatric Medicine, 41, 107-122.

Pepper, C. M., Nieuwsma, J. A., & Thompson, V. M. (2007). Rural primary care providers’ attitudes about depression. Journal of Rural Mental Health, 31, 6-18.

Polik, D.F., & Beck, C.T (2012). Nursing research: Generating and assessing evidence for

nursing practice (9th ed.). Philadephia, PA: Wolters Kluwer/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

Richards, J., Ryan, P., McCabe, M., Groom, G., & Hickie, I. (2004). Barriers to the effective management of depression in general practice. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 38, 795-803.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration

(2010). HRSA Study finds uptick of nurse practitioners working in primary care. Retrieved from http://www.hrsa.gov/about/news/pressreleases/140509nursepractitionersurvey.html

Weich, S., Morgan, L., King, M., & Nazareth, I. (2007). Attitudes to depression and its treatment in primary care. Psychological Medicine, 37, 1239-1248. doi.org/10.1017/S0033291707000931

Cite This Work

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing stye below:

Related Services

View allRelated Content

All TagsContent relating to: "Mental Health"

Mental Health relates to the emotional and psychological state that an individual is in. Mental Health can have a positive or negative impact on our behaviour, decision-making, and actions, as well as our general health and well-being.

Related Articles

DMCA / Removal Request

If you are the original writer of this dissertation and no longer wish to have your work published on the UKDiss.com website then please: