Relationship between Organisational Climate and Organisational Citizenship Behaviour

Info: 8310 words (33 pages) Dissertation

Published: 9th Dec 2019

Tagged: BusinessManagement

The relationship between Organisational Climate and Organisational Citizenship Behaviour in Bank Simpanan Nasional, Malaysia

Abstract

In a new era, the organisational climate has built as the norms, values, beliefs, traditions, and ceremonies where people work together to solve problems and face challenges. Indeed, organizational climate and organizational citizenship behaviour should accomplish in all organisations that influence employees’ action and behaviour to display employees’ extra miles of the job roles. This study was to determine whether there is a relationship between organisational climate and organisational citizenship behaviour on a non-supervisory staff of Bank Simpanan National in Malaysia. Nevertheless, the framework of this study was discussed based on the suitable underpinning theory of organisational climate and how the OCL theory relates to OCB. In this research paper, researchers examined the relationship between each of the three dimensions of organisational climate (supervisory support, autonomy, and goal direction) and OCB-I and OCB-O (OCB). The population of employees in Bank Simpanan National was 7,000. Samples taken amounted to 100 (Male = ….; Female =…..) respondents of the total population of 7,000, through sampling techniques, namely purposive sampling. Respondents’ were selected among non-supervisory employees in this study. This study was examined using the quantitative method while the data was collected using data analysis methods (correlation analysis, multivariate analysis, and descriptive analysis). In this study data analysis is done by IBM Statistical Product and Service Solution (SPSS) program for Windows version 22. Data collection techniques used the form of a 7-Likert scale of organizational climate and organizational citizenship behaviour. It was examined using correlation analysis. This study revealed a significant relationship between organizational climate and organizational citizenship behaviour on non-supervisory employees of Bank Simpanan Nasional in Malaysia. The hypotheses further showed a significant positive relationship between 1st order dimensions of organisational climate and OCB (OCBI and OCBO). This research recommended that all banks’ need to demonstrate a positive organisational climate among employees to increase OCB.

Keywords: Organizational Climate, Organizational Citizenship Behaviour, Filed theory of climate, Social Exchange Theory, Malaysian Banking Sector

Introduction

The concept of the ‘organisation’ has changed exceptionally over recent times, predominantly due to the advancement of technology, increased competition, changes to working practices, structures and nature of the organisations- traditional forms to virtual forms to networked forms and challenges faccing employees such as understanding new business processes, flexibility and working environment (Rees & Smith, 2017; Musah, et al., 2016; Pozveh & Fariba , 2017).

Early researchers have found that thirty percent of the business results are because of the organisational climate that the employee percieves around them or reported differently that thirty percent of the business results produced by the organisation is because of how their employees feel about the working enviroment within an organisation, which is a great leverage, if one thinks about it (Lafta, et al., 2016).

Although, organisational climate has been defined in the literature in many different ways, dating back to the 1960s; however, there is no consensus on this concept ( (Subramani, Jan, Gaur, & Vinodh, 2015; Eustace & Martins, 2014). For instance, Bowen and Ostroff (2004) provide a comprehensive definition of organisational climate. They define organisational climate as: “a shared perception of what the organization is like in terms of practices, policies, procedures, routines, and rewards- what is important and what behaviours are expected and rewarded- and is based on shared perceptions among employees within formal organizational units”. On the other hand, Eustace and Martins (2014) defined as: “a set of characteristics that describe an organisation, distinguishes one organisation from another, is relatively stable over time and can influence the behaviour of the organisation’s members”. It implies that members of the organisation are directly affected by the organisational climate and their attitudes and behaviours are enhanced by climate conditions.

In addition, organisational climate has divided into two forms, a positive or a negative climate (Castro & Martins, 2010). These positive and negative climates can affect staff attitudes, behaviours and their performance outcomes (Ashkanasy & Hartel, 2014). A positive organisational climate makes employees feel good about coming to work, volunteering helping others, law-abiding and provides the motivation to remain productive throughout the day. These types of behaviour are expressed as organisational citizenship behaviour (Oge & Erdogan, 2015). This notion is further supported by the organisational climate theory presented by Lewin and his colleagues- Field theory, they reiterate that behaviour is an outcome of the interaction between a person and organisational climate and all depend on each other (Shintri & Bharamanaikar, 2017). Hence, positive and strong organisational climate results in healthy climate in which workforce are loyal to their organisations (Pozveh & Fariba , 2017) and show high extra role behaviour with each other and with their managers (Oge & Erdogan, 2015). This view has demonstrated in a study by Cohen & Keren (2010), who investigated the relationship between organisational climate (OC) and organisational citizenship behaviour (OCB). They collected the data from 287 teachers from 12 schools in northern Israel. The data showed that OC made an important contribution to the understanding OCB. Similarly, a study conducted by Randhawa & Kaur (2015) to investigate the relationship between OC and OCB in the food processing industry in India.

The results of multiple regression analysis indicated that a strong (67.6 per cent) variance in OCB had explained by the dimensions of organizational climate.

The literature demonstrates that aspects of organisational climate are related to organisational citizenship Behaviour in education (Pozveh & Fariba , 2017; Farooqui, 2012; Cohen & Keren, 2010), manufacturing (Akanni & Ndubueze, 2017; Subramani, Jan, Gaur, & Vinodh, 2015; Randhawa & Kaur, 2015), health sector (Oge & Erdogan, 2015), retail sector, (Nandedkar & Brown, 2017), and banking sector (Maamari & Messarra , 2012), yet there are a few studies addressing the relationship between organisational climate and OCB constructs, particularly in the Malaysian-based Banking sector. Hence, the aim of the study is to explore the relationship between organisational climate and organisational citizenship behaviour on a non-supervisory staff of Bank Simpanan National in Malaysia.

Literature Review

Organizational Climate

Organizational Climate is a very widespread area for research in the field of industrial and organizational psychology. Generally speaking, the climate is described as the consistent course or condition of the environment at a place over a time as exhibited by the surrounding elements such as temperature, rainfall and wind (Gerceker, 2012). The organisational climate is to some extent like the personality of a person that makes him distinct from others. Similarly, each organisation has it’s on unique organisational climate that differentiates it from other organisations. Essentially, the organisational climate depicts a person’s perception of the work climate to which they belong to (Subramani, Jan, Gaur, & Vinodh, 2015). The concept of organizational climate was developed in the late 1940s by the social scientist, Lewin, Lippitt & white. They used organisational climate term to describe personal feelings or atmosphere they experienced in their studies of organisations. They found that different groups had distinctively different perceptions about their surroundings (Iqbal, 2011). In fact, it is one of the important constructs to understand human behaviour and their interaction with their work environment (Suguna, 2014).

A number of definitions of organisational climate have been presented in the literature by different researchers. For instance, Litwin and Stringer (1968, as cited in (Akanni & Ndubueze, 2017)) defined organizational climate as: “the set of measurable properties of the work environment that is either directly or indirectly perceived by the employees who work within the organizational environment that influences and motivates their behaviour”. Pritchard & Karasick (1973) defined as a: “relatively enduring quality of an organization’s internal environment, distinguishing it from other organizations, which a) results from the behaviour and policies of members of the organization, especially in top management, b) is perceived by members of the organization, c) serves as a basis for interpreting the situation and d) acts as a source of pressure for directing activity”.

Similarly, Schneider (1975) examines the climate and its relationship with specific organizational conditions, events and experiences. He defined the organisational climate as: “psychologically meaningful molar [environmental] descriptions that people can agree characterize a system’s practices and procedures”. In line with Schneider (1975), Moran & Volkwein (1992) explained the organisational climate as: “members’ perception about the extent to which the organisation is currently fulfilling their expectations”. Similarly, Gerber (2003) defined it as: “the shared perceptions, feelings and attitudes organisational members have about the fundamental elements of the organisation which reflect the established norms, values and attitudes of the organisation’s culture and influence individuals’ behaviour either positively or negatively”.

Above definitions of organizational climate highlight the fact that it is clearly a perception that reflects organizational members’ individual impressions of their environment. From the above definitions, the following common themes can be highlighted:

- It is perceived and shared by the members who work within the environment

- It can influence and motivates an individual behavior

- Organisational climate relatively enduring over time and influence the behavior of people within

- Climate is considered a molar phenomenon that can change over time

- Organisational climate is a dynamic process that establishes a link between the member and their environment.

In conclusion, organisational factors such as policies, procedures, culture and structure affect the behaviour (Tinti, Venelli-Costa, Vieira , & Cappallozza, 2017) by assisting the individual in creating a perception of the organisation. Through perception Individuals try to attempt to understand of their environment and the objects, people, and events in it varies from person to person because each person gives his/her meaning to stimuli (Elnaga, 2012). Hence, a positive perception about the organisational climate is helpful to improve satisfaction (Ghavifekr & Pillai, 2016), better human relations (Cummings & Worley , 2015), enhance organisational commitment (Iqbal, 2011), higher productivity and decrease turnover (Berberoglu, 2018). Therefore, the organisational climate is best defined as:

Relatively permanent nature of the organisation’s internal environment, which is a) perceived by organisation members b) influencing their behaviours, and c) can be defined with nominal values consist of a certain set of properties of the organization. (Tagiuri & Litwin, 1968)

Organisational Climate and its Dimensions

The above discussion highlights the definitions and view of organizational climate (OC) from different perspectives. Similarly, in literature, it appears that there is no consensus on dimensions of OC because researchers explore diverse types of dimensions to review organizational climate. The summary of the OC dimension is shown in the following table (Table 1):

Table 1: Summary of Major Contributors to The Dimensions of Organisational Climate

| (Kahn, Wolfe, Quinn, Snoek , & Rosentbal, 1964) | (Tagiuri & Litwin, 1968) | (Litwin & Stringer, 1968) | (Schneider & Batlett, 1968) | (Pritchard & Karasick, 1973) | (Koys & Decotis, 1991) | (Martins & Martins, 2001) | |

| Rule orientation | The sense of goal direction | Structure | Management Support | Autonomy | Support/Sincerity | Autonomy | |

| Nature of Subordinates | Autonomy/ Empowerment | Responsibility | Management Structure | Conflict/Cooperation | Pressure | Cohesion | |

| Closeness of supervision | Working with Supervisor | Warmth | The concern of new employees | Social relationships | Cohesion | Trust | |

| Promotion of achievement orientation | Co-operative and pleasant people | Support | Intra agency conflict | Structure | Intrinsic recognition | Pressure | |

| Profit minded, and sales oriented | Tolerability | Agent independent | Rewards | Impartiality | Support | ||

| Risk | General satisfaction | Performance based rewards | Trust | Recognition | |||

| Standard | Status polarization | Openness | Fairness | ||||

| Rewards | Flexibility | Innovation | |||||

| Conflict | Decision centralization | ||||||

| Achievement orientation of organisation | |||||||

| Supportiveness | |||||||

Source: Authors’ construct

In this study, the following dimension have been adopted from Tagiuri & Litwin (1968);

- Supervisory Support: The perceived supervisory support (PSS) refers to employee views concerning the extent to which supervisor value employees’ contributions, and care about their wellbeing (Tuzun & Kalemci, 2012). It affects employee’s perception towards the organisation and leads for employees to high commitment through job satisfaction and motivation

- Autonomy: The perception of self-determination with respect to work procedures, goals and priorities (Martins & Martins, 2001). Employees at the workplace are given autonomy to define their own work, take initiative to acquire and share information and decision about their own work.

- Goal direction: Practices related to providing a sense of direction or purpose of their jobs, setting of objectives, planning and feedback (Tagiuri & Litwin, 1968).

Organisational Citizenship Behaviour

The organisational citizenship behaviour (OCB) is a behaviour that is above and beyond one’s job requirement. This is a person’s voluntary commitment and not required from organisational members but essential for organisational effectiveness (George & Jones, 2008). According to George & Jones (2008) some of the examples of OCB include: “helping co-workers; protecting the organisation from fire, theft, vandalism and other misfortunes; making constructive suggestions; developing one’s skills and capabilities; and spreading goodwill in the larger community” (p. 95). It implies that individuals exhibiting these behaviours care about others and they try to go the extra mile to do something for others without complaining to displeasure. Similarly, Beauregard (2012) observed that superiors engaged in high OCB are very cooperative, supportive and compassionate in solving the subordinate’s problems and understanding their working relationships.

To understand why OCB occurs at the workplace? Greenberg & Baron (2008) identified a few factors involved in engaging in OCB, they are presented below:

- People’s perception that they are being treated fairly by their organizations is a critical

factor.

- When people hold good relationships with their supervisors.

- Personality characteristics also are linked to OCB. Specifically, individuals who are highly conscientious and empathetic, are inclined to engage in OCB.

The concept of OCB was introduced the first time in the paper of Barnard and Katz (Oge & Erdogan, 2015) and expanded by Dennis W. Organ (Subramani, Jan, Gaur, & Vinodh, 2015). According to Organ (1988), OCB is defined as: “individual behaviour that is discretionary, not directly or explicitly recognized by the formal reward system and that in the aggregate promotes the effective functioning of the organization”. Similarly, MacKenzie, Podsakoff, & Ahearne (1998) defined OCB as: “descretionary behaviours on the part of an employee that directly promotes the effective functioning of the organization, independent of the employee’s objective productivity”. Pickford & Joy (2016) describe OCB as a: “wide range of individual actions that go beyond assigned tasks, often for the benefit of the organisation – and that may be motivated by personal aspirations”. Based on the above definition of OCB by (Organ, 1988), the three critical aspects that are central to OCB are as follows:

- First, OCBs are thought of as discretionary behaviors, which are not part of the job description, and are performed by the employee as a result of personal choice.

- Second, OCBs go above and beyond that which is an enforceable requirement of the job description.

- Finally, OCBs contribute positively to overall organizational effectiveness.

In conclusion, organizational citizenship behaviour is stated as behaviours that employees display without expecting any rewards in return and not held for punishment if it does not comply, not incorporated in the job descriptions and task definitions. An in terms of its results, it contributes to the employees and the organisation positively (Huang & You, 2011).

Organisational Citizenship Behaviour and its Dimensions

There are certain factors that can contribute to the determination of organisational citizenship behavior (OCB). However, the dimensions suggested and explored by Denis W Organ are widely accepted, which include Altruism, Conscientiousness, Civic virtue, Courtesy and Sportsmanship (Organ, 1988) but the factors that have been researched to have a significant relationship with OCB, are the first three that is Altruism, Conscientiousness, and Civic Virtue (Borman, Hanson, Motowidlo, Stark, & Drasgow, 2001). The dimensions used by Organ (1988) are discussed in Table 2 along with a description.

Table 2: Dimensions of Organisational Citizenship Behaviour

| Dimension

|

Description | Examples |

| Altruism | Voluntary actions that help a fellow employee in work related problems |

|

| Civic Virtue | Voluntary participation in, and support of organizational functions of both a professional and social nature |

|

| Conscientiousness | A pattern of going well beyond minimally required role and task requirements |

|

| Courtesy | The discretionary enactment of thoughtful and considerate behaviours that prevent work-related problems for others. |

|

| Sportsmanship | Willingness to tolerate the inevitable inconveniences and impositions that result in an organization without complaining and doing so with a positive attitude. |

|

Source: Adapted from Greenberg & Baron (2008)

Organ (1988) five-dimension taxonomy, Williams & Anderson (1991) proposed a two-dimensional conceptualisation of OCB: OCB-I (behaviour directed towards individuals; comprising altruism and courtesy) and OCB-O (behaviour directed towards the organisation, comprising the remaining three dimensions i.e. conscientiousness, sportsmanship and civic virtue. In this study we are following OCB-I and OCB-O as dependent variables. According to William & Anderson (1991) the explanation of OCB sub-scales is as follows:

- OCB-I – Behaviour that immediately brings profit to specific individuals, and indirectly to an organization. These behaviors fit in the category of Helping behaviors.

- OCB-O – Behavior that generally brings profit to an organization. These behaviours fit into the category of organizational obedience/ subordination.

The following section discusses the theoretical framework along with the empirical research on the purposed constructs.

Theoretical Framework and Empirical Studies

Two theories incorporated to present the research framework for this stud. These are ‘field theory of behaviour’ for OC and ‘Social Exchange Theory (SET)’ for OCB. The field theory of behaviour is a conceptual model developed by Lewin et. al (1939 as cited in Musah, et al., 2016), which examines the pattern of interactions between the environment and the human behaviour. In other words, the field theory of behaviour suggests that how the employees feel about the organisational atmosphere in which they work (Musah, et al., 2016). The theory is expressed in the form of an equation:

B= f (P, E)

Where B= Behaviour, P= person and E= environment

Lewin’s field theory of behaviour reiterates that behaviour is an outcome of the interaction between a person and environment and they all depend on each other (Shintri & Bharamanaikar, 2017). The relationship among the three variables have also been examined by many studies across diverse fields such as education, behavioural science, and management and their findings are consistent with Lewin’s observation. Studies have also indicated that one’s beliefs about others can become a key situational factor influencing their behaviour (Weisbord, 2004).

In conclusion, the field theory suggests that individual behaviour is influenced by how one perceives and reacts to the environment provided by the organisation (Munidi & K’Obonyo, 2015). Hence, organisational climate, according to Iqbal (2011) is a: “perceived environment in which an individual’s and organization’s expectations are met”.

The second theory reviewed for this study was the social exchange theory for OCB. This theory has one of the best frames to explain the OCB of employee (Organ 1990). The theory assumes that humans are instrumentally motivated in their relationships with others. When individuals provide assistance or support to others, another party in the relationship has something to contribute in returns (Talebloo, Basri, Hassan, & Asimiran, 2015). Similarly, individuals with a good perception of their organisation and feel that organisation treat them fair, behave in ways to benefit the organization and co-workers and show their commitment to their organisation (Mahooti, Parvaneh , & Asadi, 2018). In conclusion, Organ (1988 as cited in Agyemang, 2013) proposed a social exchange between the employees and the organisations as:

“ whereby employees perform citizenship behaviors to reciprocate the fair treatment offered by the organization”.

The relationship between organisational climate and organizational citizenship behaviour

There is a nmber of studies have been conducted to investigate the relationship between organisational climate (OC) and organisational citizenship behaviour (OCB). As Lewin’s field theory of organisational climate posits that organisational climate can influence the perceptions that employees have about their roles and expectations. Hence, a positive work climate influences employees’ attitudes and behaviours, which in turns nurture organisational citizenship behaviour among its employees. This relationship is further explained by the Social Exchange theory (SET) (Podsakoff, Mackenzie, Maynes, Spoelma, & Podsakoff, 2014). Most research findings maintained the notion that a supportive and positive organisational climate predicts OCB in organisations. For instance, a study conducted by Akanni & Ndubueze (2017) in the industrial sector, they investigated the relationship between organisational cliamte and organisational citizenship behaviour among employees of selected private companies in southern-eastern Nigeria. The study revealed that OC significantly (r=0.34, p<0.01) predicted OCB. In another study, Subramani, Jan, Gaur, & Vinodh (2015) conducted a study on the Indian auto industry. They found that the organisational climate is having a positive impact on organisatonal citizenship behaviour and its components (altruism, courtesy, sportsmanship, conscientiousness and civic virtue) through structural equation modelling approach. Similarly, Gheisari, Sheikhy, & Salajghe (2014) conducted a study to explore the relationship between dimensions of organisational climates and other variables such as organisational commitment, job involvement and OCB. By applying structural equations and Pearson correlation coefficients, they found statistically significant relationships between OCand OCB and vice versa.

The relatioship between organisational climate and organisational citizenship in the education sector have also been documented. In Iran, Pozveh & Fariba (2017) examined the relationship between OC and OCB of the staff members in the department of education in Isfahan city. The results of the study reveal that there is a direct and significant relationship (r= 0.44, p<.0.01) between organisational climate, its dimensions and OCB. In an exploratory study performed in the education sector in Pakistan regarding the link between OC and OCB, Farooqui (2012) established that all the dimensions of the OC are found to be significantly related to OCB and gender has also an explanatory power towards OCB. Similarly, Cohen & Keren (2010) investigated the relationship between organisational climate and organisational citizenship behaviour of teachers in the Israel context. The analysis showed that the data supported the link between OC and OCB. Their study also revealed that OC, particularly perceptions about the principals’ leadership style, made a unique and significant contribution to the understanding of OCB. In another study, Cilla (2011) conducted a study to examine the relationship between OCB and organizational climate for creativity among students of Metropolitan University in North of California. He found that perception of employees of creative organisational climate was associated at moderately with OCB scales. The employees with creative organizational climate have high social relations and internal motivation to do the duties.

The link between OC and OCB has been evaluated in the healthcare sector. In Turkey context, Oge & Erdogan (2015) carried out a study to examine the relationship between organisational climate and organisational citizenship behaviour in relevant institutions and organisations operating in the health sector in Turkey. The findings of this study show that there is a statistically significant relationship between dimensions of the OC and subscales of OCB. In another study by Obiora and Okpu (2015 as cited in Akanni & Ndubueze (2017)) conducted a study among employees in the hospitality industry in Nigeria. They found that the creative climate was highly related to OCB dimensions (altruism, conscientiousness, civic virtue, courtesy and sportsmanship),

Nandedkar & Brown (2017) investigated the relationship between organisational climate, organisational citizenship behaviour and turnover intentions in the US retail sector. They found that that OC is the moderator of the relationship between OCBs and turnover interntions.

A significant number of studies have been conducted to examine the relationship between organisational climate and organisational citizenship behaviour in the Banking sector. Agyemang (2013) conducted a study to examine workers’ perception of their work environment and the extent to which they go forward to perform unassigned and not required roles in the organisation. Analysis of the results reveals that employees’ perception of organisational climate positively influenced (r= 0.27, p<0.01) OCB in the Ghanian context. It means that the OCB enhances when employees perceive their organisational climate is supportive and favourable and vice versa. In another study conducted on the commercial banking sector in the Lebanonese context, Maamari & Messarra (2012) found that organisational climates had a significant and positive effect on organizational citizenship behaviour dimensions.

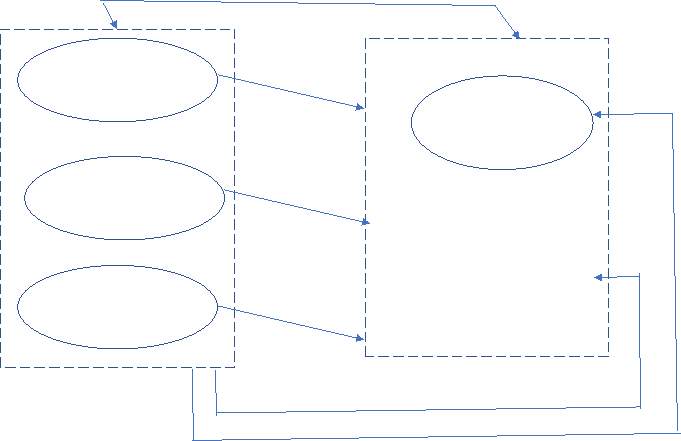

Based on the literature reviewed and the empirical studies stated above, the researchers proposed that:

H1: There will be a significant positive relationship between organizational climate dimension autonomy and OCB.

H2: There will be a significant positive relationship between organisational climate dimension supervisory support and OCB

H3: There will be a significant positive relationship between organisational climate dimension goal direction and OCB

H4: There will be a significant positive relationship between organisational climate and OCB

H5: There will be a significant positive relationship between organisational citizenship behaviour and organisational climate

H6: There will be a significant positive relationship between organisational climate and OCB- I

H7: There will be a significant positive relationship between organisational climate and OCB-O

Based on the study hypotheses, the conceptual model of study is shown in Fig. 1. In this study, the dimensions and components of each variable are shown in the conceptual model.

H4

H4

H5

Autonomy H1

OCB- I

Supervisory Support H2

OCB-O Goal Direction H3

Organisational climate Organisational Citizenship Behaviour

H7

H6

Fig 1: Conceptual Framework

Conclusion and Implications

The objective of this study was to investigate the relationship between organisational climate (OC) and organisational citizenship behaviour (OCB) on a non-supervisory staff of Bank Simpanan National in Malaysia. It examined the relationship between OC dimensions (Autonomy, Supervisory support and Goal direction) and OCB dimensions (OCB-I and OCB-O). The outcome of this study indicated that OC has a direct and significant effect on OCB.

In this study, organisational climate dimensions (Autonomy, Supervisory support and Goal direction) and OCB dimensions (OCB-I and OCB-O) were also examined. Among three climate dimensions (Autonomy, Goal direction, Supervisory support) only one of them was (supervisory support) related to OCB.

The study concluded that organisations with a positive climate enjoy more extra-role behaviours from employees. This finding is consistent with previous studies (MacKenzie, Podsakoff, & Ahearne, 1998; Akanni & Ndubueze, 2017), who found that employees with higher levels of supervisory support from top management are more likely display more OCB.

The findings of this study have some managerial implications with regard to the existing literature on OC. In light of the above-mentioned results, top authorities of the Bank Simpanan Nasional need to recognise the importance of their organizational climate. Top authorities of the Simpanan Nasional Bank need to encourage positive climate that provides autonomy and goal direction to their employees. A study published by Ozer (2011) on understanding the theoretical mechanisms that explain the relationship between organizational citizenship behaviours (OCBs) and job performance. The study found that: “highly autonomous workers were better citizens, had better team relationships, and were better at translating those team relationships into improved performance”. In addition, the conceptual model, with some additional variables such as demographic and tenure, could be applied to predict the degree of satisfaction with the OC in which they work in.

Limitations and future research

There are some limitations with this study.

Firstly, this study has relied on a purposive sample or judgemental sampling given difficulties in accessing a random sample in the Bank Simpanan Nasional, Malaysia. Although judgemental sampling is a common approach followed by many researchers in the social sciences (Malhotra, 2007), yet it does not allow direct generalisations to a specific population. However, this study has controlled for a comprehensive set of organisational variables to improve the reliability of the results. Nevertheless, the authors recommend replicate this study using a random sampling approach when possible.

Furthermore, the study gained a a reasonable sample size (n = 100) for analysis, future studies are advised to increase the sample size to increase the reliability of the results attained. Thirdly, the study relied only on the selected dimension of OC and examined their relationship with OCB. Therefore, future studies should include all the dimensions of the OC to capture the big picture of the relationships.

Lastly, as with most studies in the literature, we followed a cross-sectional study design which may not always provide definite information about the direction of the relationship between the study variables despite the evidence presented here. Future researchers are advised to follow a longitudinal study design along with deployment of triangulation method to strengthen the results.

References

Agyemang, C. B. (2013). Perceived organizational climate and irganizational tenure on organizational citizenship behaviour: Empirical study among Ghanaian banks. European Journal of Business and Management, 5(26), 132-143.

Akanni, A. A., & Ndubueze, K. I. (2017). Organisational climate and organisational citizenship behaviour of employees in selected private companies in South-East Nigeria. Australasian Journal of Organisational Psychology, 10(5), 1-6.

Ashkanasy, N. M., & Hartel, C. (2014). Positive and negative affective climate and culture: the good, the bad, and the ugly. In N. Ashkanasy, C. Hartel, B. Schneider, & K. Barbera (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Organizational Climate and Culture (pp. 136-152). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Beauregard, T. A. (2012). Perfectionism, self-efficacy and OCB: The moderating role of gender. Personnel Review, 41(5), 590-608.

Berberoglu, A. (2018). Impact of organizational climate on organizational commitement and perceived organizational performance: Empirical evidence from public hospitals. BMC Health Services Research, 18(1), 399.

Borman, W. C., Hanson, M. A., Motowidlo, S. J., Stark, S., & Drasgow, F. (2001). An examination of the comparative reliability, validity and accuracy of performance rating made using computerised adaptive rating scjales. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86, 965-973.

Bowen, D. E., & Ostroff, C. (2004). Understanding HRM-firm performance linkages: the role of the ‘strength’ of the HRM system. Academy of Management Review, 29(2), 203-221.

Castro, M., & Martins, N. (2010). The relationship bwteen organisational climate and employee satisfaction in South African Information and Technology Organisation. SA Jourbal of Industrial Psychology, 36(1), 9.

Cilla, M. J. (2011). Exploring the Relationship between Organizational Citizenship Behavior and Organizational Climates for Creativity. San Jose University.

Cohen, A., & Keren, D. (2010). Does climate matter? An examination of the relationship between organisational climate and OCB among Israeli teachers. The Service Industries Journal, 2, 247-263.

Cohen, A., & Keren, D. (2010). Does climate matter? An examination of the relationship between organisational climate and OCB among Israeli teachers. The Service Industries Journal, 30(2), 247-263.

Cummings, T., & Worley, C. (2015). Organisational Development and Change. Stamford: Cengage Learning.

Elnaga, A. A. (2012). The impact of perception on work behaviour. Arabian Journal of Business and Management Review, 2(2), 56.

Eustace, A., & Martins, N. (2014). The role of leadership in shaping organisational climate: An example from the FMCG industry. SA Journal of Industrial Psychology, 40(1), 1-13.

Farooqui, M. R. (2012). Measuring organizational citizenship behavior (OCB) as a consequence of organizational climate (OC). Asian Journal of Business Management, 4(3), 294-302.

George, J. M., & Jones, G. (2008). Understanding and managing organizational Behavior. New Jersey: Pearson Education.

Gerber, F. (2003). The influence of organisational climate on work motivation. University of South Africa, Pretoria.

Gerceker, B. (2012). The relationship between organizational climate and information security in Healthcare Organizations. Dokuz Eylul University Institute of Health sciences.

Ghavifekr, S., & Pillai, N. S. (2016). The relationship between the school’s organizational climate and teacher’s job satisfaction: the Malaysian experience. Asia Pacific Education Review, 17(1), 87-106.

Gheisari, F., Sheikhy, A., & Salajghe, S. (2014). Explaining the relationship between organizational climate, organizational commitment, Job involvement and organizational citizenship behaviour among employees of Khuzestan Gas Company. International Journal of Applied Operational Research, 4(4), 27-40.

Greenberg, J., & Baron, R. (2008). Behavior in Organizations. New Jersey: Person Education.

Huang, C.-C., & You, C.-S. (2011). The three components of organizational commitment on in-role behaviors and organizational citizenship behaviours. African Journal of Business and Management, 11335-11344.

Iqbal, A. (2011). The influence of personal factors on the perceived organizational climate: Evidence from the Pakistani industrial organizations. Interdisciplinary Journal of Contemporary Research in Business, 2(9), 511-527.

Kahn, R., Wolfe, D., Quinn, R., Snoek, J., & Rosentbal, R. (1964). Organizational stress: Studies in role conflict and ambiguity. New York: Wiley.

Koys, D. J., & Decotis, T. A. (1991). Inductive measures of psychological climate. Human Relations, 33-46.

Lafta, A. H., Man, N. B., Salih, J. M., Samah, B. A., Nawi, N. B., & Yusof, R. N. (2016). A need for investigating organizational climate and its impact on the performance. European Journal of Business and Management, 8(3), 136-142.

Litwin, G. H., & Stringer, R. A. (1968). Motivation and Organizational Climate. Cambridge: Harvard Business School, Division of Research.

Maamari, B., & Messarra, L. (2012). An empirical study of the relationship between organizational climate and organizational citizenship behavior. European Journal of Management, 12(3), 165-174.

MacKenzie, S. B., Podsakoff, P. M., & Ahearne, M. (1998). Some possible antecedents and consequences of in-role and extra-role performance. Journal of Marketing, 62(3), 69-86.

Mahooti, M., Parvaneh, V., & Asadi, E. (2018). Effect of organizational citizenship behaviour on family-centered care: Mediating role of multiple commitment. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0204747

Martins, E. C., & Martins, N. (2001). Organisational Surveys as a tool for change. Part Two: A case Study. HR future, 1(4), 46-49.

Moran, T. E., & Volkwein, F. J. (1992). The cultural approach to the formation of organizational climate. Human Relations, 45(1), 19-38.

Munidi, F., & K’Obonyo, P. (2015). Quality of work life, personality, job satisfaction, competence and job performance: A critical review of literature. European Scientific Journal, 11(26), 223-240.

Musah, M. B., Ali, H. M., Al-Hudawi, S. H., Tahir, L. M., Daud, K. B., Said, H. B., & Kamil, N. M. (2016). Organisational climate as a preditor of workforce performance in the Malaysian higher education institutions. Quality Assurance in Education, 24(3), 416-438.

Nandedkar, A., & Brown, R. S. (2017). Should I leave or not? The role of LMX and organizational climate in organisational citizenship behavior and turnover relationship. Journal of Organisational Psychology, 17(4), 51-66.

Oge, S., & Erdogan, P. (2015). Investigation of relationship between organizational climate and organizational citizenship behavior: A research on Health Sector. International Journal of Economics and Management Engineering, 9(10), 3628-3635.

Organ, D. (1990). The motivational basis of organizational citizenship behaviour. Research in Organizational Behavior, 42, 43-72.

Organ, D. W. (1988). Organizational Citizenship Behaviour: The Good Soldier Syndrome. Lexinton-Massachusetts: Lexinton Books.

Pickford, H. C., & Joy, G. (2016). Organisational Citizenship Behaviours: Definitions and Dimensions. Oxford, United Kingdom.

Pourgaz, A. W., Abdul, G. N., & Jenaabadi, H. (2015). Examining the relationship of organisational citizenship behaviour with organizational commitment and equity perception of secondary. Psychology, 800-807.

Pozveh, A. Z., & Fariba, K. (2017). The relationship between organizational climate and organizational citizenship behaviours of the staff members in the department of Education in Isfahan city. International Journal of Educational & Psychological Researches, 3(1), 53-60.

Pritchard, R. D., & Karasick, B. W. (1973). The effect of organisational climate on managerial job performance and job satisfaction. Organisational Behaviour and Human Performance, 9(1), 126-146.

Rees, G., & Smith, P. E. (2017). Strategic Human Resource Management- An International Perspective. Singapore: Sage Publications Asia-Pacific Pte Ltd.

Schneider, B. (1975). Organizational climates: An Essays. Personal Psychology, 28(1), 447-479.

Schneider, B., & Batlett, J. (1968). Individual differences and organizational climate I: The research plan and questionnaire development. Personnel Psychology, 21(2), 323-333.

Shintri, S., & Bharamanaikar, S. (2017). The theoretical study on evolution of organisational climate, theories and dimensions. International Journal of Science Technology and Management, 6(3), 652-658.

Subramani, A. K., Jan, N. A., Gaur, M., & Vinodh, N. (2015). Impact of organizational climate on organizational citizenship behaviour with respect to automotive industries at Ambattur Industrial estate, Chennai. International Journal of Applied Business and Economic Research, 13(8).

Suguna, K. (2014). Organizational climate- Differing concepts and measurements. Global Journal of Research in Management, 4(1), 67-85.

Tagiuri, R., & Litwin, G. H. (1968). Organizational climate, Explanations of a concept, Division of Research. Boston: Harvard University.

Talebloo, B., Basri, R. B., Hassan, A., & Asimiran, S. (2015). A survey on the dimensionality of organizational citizenship behaviour in primary schools: Teachers’s perception. International Journal of Education, 7(3), 12-30.

Tinti, J. A., Venelli-Costa, L., Vieira, A. M., & Cappallozza, A. (2017). The impact of human resource of policies and practices on organisational citizenship behaviors. Brazilian Business Review, 14(6). doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.15728/bbr.2017.14.6.6

Tuzun, I. K., & Kalemci, R. A. (2012). Organizational and supervisory support in relation to employee turnover intentions. Journal of Managerial Psychology(27), 518-534.

Weisbord, M. R. (2004). Productive workplaces revisited: Dignity, meaning and community in the 21st century. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Williams, L., & Anderson, S. (1991). Job satisfaction and organizational commitment as predictors of organizational citizenship and in-role behaviors. Journal of Management, 17(1), 601-617.

Cite This Work

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing stye below:

Related Services

View allRelated Content

All TagsContent relating to: "Management"

Management involves being responsible for directing others and making decisions on behalf of a company or organisation. Managers will have a number of resources at their disposal, of which they can use where they feel necessary to help people or a company to achieve their goals.

Related Articles

DMCA / Removal Request

If you are the original writer of this dissertation and no longer wish to have your work published on the UKDiss.com website then please: